THE TYLENOL MURDERS, 1982

DEATH AT THE DRUGSTORE

Tylenol is one of the US’s leading over-the-counter remedies for pain and fever. However, in September 1982, after taking the harmless drug, people in Chicago started dropping down dead.

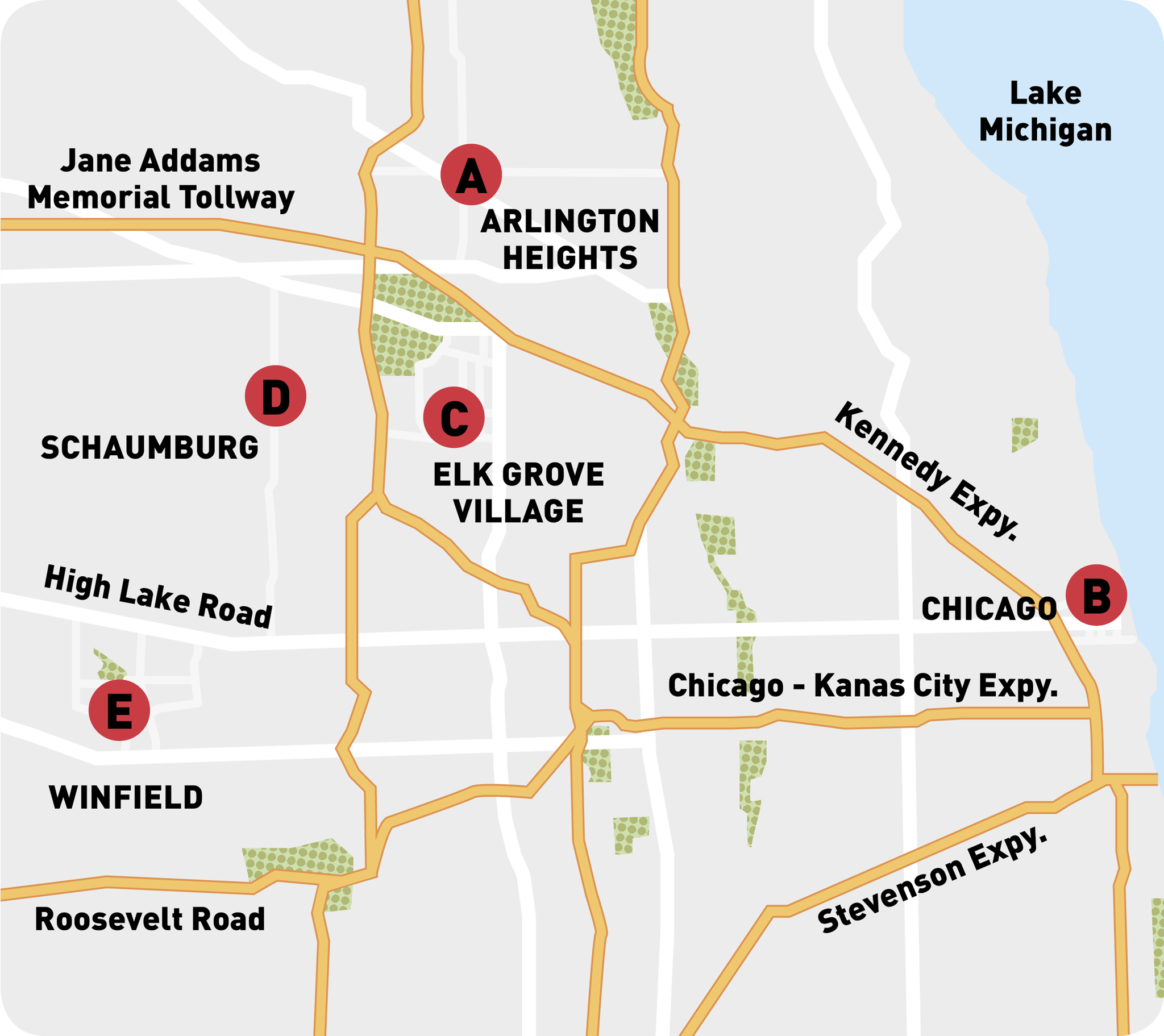

Mary Kellerman woke up one Wednesday morning in 1982 feeling a bit under the weather. Her parents did what many do when hearing sore-throat complaints: They gave her Extra-Strength Tylenol to ease the pain before it was time for her to head off to school in the Chicago suburb of Elk Grove Village, Illinois. Mary padded into the bathroom and closed the door. Her father heard a sudden, loud thump. Paramedics tried to save Mary, but nothing helped. The twelve-year-old girl was pronounced dead by 10 a.m.

Across town, a 27-year-old postal worker named Adam Janus woke up sick enough to call off work. He picked up his kids from morning preschool and stopped by a pharmacy in another Chicago suburb to get some medicine. He fixed his children lunch, then prescribed himself two Tylenol and a nap. Minutes later, he collapsed in his kitchen. Medics suspected a heart attack, despite his young age and seemingly good health. No one could have known that Mary and Adam’s deaths were tragically linked, despite the two having never met. They would be the first of seven victims killed by Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules poisoned with potassium cyanide.

Clockwise from top: Jack Eliason and his wife Nancy hold up a picture, taken in 1974, of Jack’s sister Mary McFarland (on right), poisoned by the Tylenol killer; James W. Lewis and Roger Arnold, two of the suspects; as alarm spreads, a drugstore clerk in New York City removes Tylenol from the shelves.

Devastated family members gathered in mourning at Adam Janus’ home. The dead man’s younger brother, 25-year-old Stanley, felt chronic back pain flaring up, and Stanley’s 19-year-old wife Theresa had a headache, brought on by the stress of the heartbreaking day. The couple both swallowed some Tylenol from Adam’s cabinet. Stanley collapsed first, then Theresa.

Thomas Kim, medical director of the Northwest Community Hospital’s intensive care unit, had been the one to sign Adam’s paperwork indicating that he had suffered a heart attack. He was about to leave for home when he heard that more members of the Janus family were being rushed to his unit. Kim later told reporters of his shock at these sudden developments. He had met Stanley just hours earlier. “I had been talking to this six-foot, healthy guy,” he said.1 When he learned Stanley’s wife was also dangerously ill, he knew he was dealing with something far more sinister than a heart attack.

The same day that Mary Kellerman and Adam Janus died—September 29, 1982—a woman named Mary “Lynn” Reiner suffered the same fate. At 3:45 p.m., the broad-smiled 27-year-old, who had given birth just days earlier, popped some Tylenol for her pain. She collapsed and died soon after.

As investigators searched the Janus house, another woman—31-year-old Mary McFarland—told her coworkers at an Illinois Bell store in Lombard that she had a headache and went into a back room to take some Tylenol. She collapsed within minutes, and died.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

In hindsight, it is easy to see Tylenol as a common thread. However, for investigators at the time, the use of this over-the-counter medication was so mundane that it did not jump out as the cause of death. What Dr. Kim did soon figure out was that the victims all showed symptoms of potassium cyanide poisoning—abdominal pain, dizziness, and heart failure. Blood tests confirmed his diagnosis and, as he later told reporters, he paced his office, trying to work out how these disparate people had all been exposed to the same toxin.

By the end of Wednesday, barely 12 hours after little Mary Kellerman was pronounced dead, two suburban firefighters who had been monitoring chatter on the fire radios they kept in their homes started comparing notes on the phone. The firefighters shared their theory with Kim, who knew the Januses had taken Tylenol but hadn’t known about the other victims. Authorities retrieved the red-and-white bottles from all of the victims’ homes and realized they came from the same lot and shared expiration dates.2

“I SAID, ‘THIS IS A WILD STAB, BUT MAYBE IT’S TYLENOL.’”

Nicholas Pishos, an investigator for the Cook County medical examiner’s office, had studied cyanide in a college biology class. He and chief medical examiner Edmund Donoghue were discussing the murders over the phone when Donoghue remembered that cyanide has a distinctive smell. Pishos opened the bottles. “I said, ‘Whoops. I smell something. It smells like almonds,’” he later told a reporter.3

Lab tests confirmed that whoever was behind the tampering had made it a gunless game of Russian roulette. In each bottle, a handful of the capsules had been emptied and replaced with a lethal dose of cyanide. Between 5 and 7 micrograms of cyanide is fatal, and the contaminated capsules contained as much as 65 milligrams of the poison—several thousand times more than a fatal dose. The people who consumed these capsules typically collapsed within minutes.

PANIC IN CHICAGO

By Thursday, just one day after the first deaths, the media were warning all of Chicago—and soon the country—about the Tylenol connection. Chicago police, worried residents might miss the news, went through the streets broadcasting the message over loudspeakers. Investigators with the US Food and Drug Administration warned consumers to avoid buying Tylenol and not to take any already in their homes. Pharmacy owners pulled the drug from their shelves, and Johnson & Johnson—the parent firm for Tylenol maker McNeil Consumer Products Co.—offered refunds to panicked customers.

POISONED PILLS

McNeil officials ruled out tampering during production. The company routinely kept a random sample of pills from every lot produced. They tested the lot in question—MC2880, expiration date April 1987—after the deaths. “They were clean,” said McNeil spokeswoman Elsie Bemer. This finding led authorities to believe that someone in Chicago had bought the Tylenol bottles legitimately, taken them home, tampered with the capsules, and then put them back on shelves throughout the city. Unwitting customers bought them, never knowing when they paid for their simple bottle of headache medicine that they were sealing their—or their loved ones’—fate.

Meanwhile, the body count grew. On Friday, October 1, 35-year-old Paula Prince was found in her Chicago apartment. She had last been seen at a Walgreens on North Wells Street on Wednesday, just after the flight attendant had landed in O’Hare from Las Vegas. Surveillance photos showed Prince buying a bottle of Tylenol at about 9:30 p.m. that night. She had no way of knowing that across town, doctors were on the cusp of tying tainted Tylenol capsules to a spate of sudden deaths.

September 30, 1982 / The final victim, Paula Prince, dies after taking Tylenol.

Prince died soon after taking the pills, but her body was not discovered for two days. “Her sister was supposed to meet her for dinner, and [Paula] wasn’t answering her telephone,” friend and fellow flight attendant Joan Ahern later commented.3 According to Richard Brzeczek, superintendent of the Chicago Police Department, Paula Prince had gone to the bathroom to remove her makeup and popped the meds while in there. “The Tylenol bottle was still sitting open on the vanity,” Brzeczek commented. “She took it in the bathroom, and by the time she got to the threshold of the door, she was dead.”

DEAD ENDS

As panicked as Chicago was, the rest of the nation could take comfort in knowing that the attack appeared to be isolated—until it didn’t. A few days into the high-profile investigation, news spread that other victims were falling ill nationwide from various poisons, including rat poison and hydrochloric acid. Authorities investigated and found that these incidents were caused by opportunistic copycats. It seemed that anyone with a grudge was jumping aboard the pill-tainting bandwagon. Some even branched out to new methods, hiding sharp pins in Halloween candy, leading some communities to ban trick-or-treating altogether.

As soon as the method and means were pinpointed in the Tylenol poisonings case, the police expressed confidence that the perpetrator would be swiftly apprehended. But that didn’t happen. Five days after the deaths began—when the tally had reached seven—Illinois Attorney General Tyrone Fahner announced that the police were searching for a man who had been arrested in August for shoplifting Tylenol. It seemed a promising lead on the surface, but Fahner tempered public expectations: “We’re not quite sure what to think. Sometimes people steal anything. They may have just been stealing Tylenol to steal it.”4 The shoplifter story made big headlines but was quickly discounted. It turned out that he’d been behind bars since his August arrest. He was just one of several fruitless leads pursued.

Investigators also sought to interview disgruntled employees with both Johnson & Johnson and McNeil. They took notes on tips about suspicious-looking customers. One pharmacy employee was arrested after police got a tip he kept cyanide in his house. The man was eventually cleared after the supposed cyanide turned out to be a nontoxic cleaning agent.

Investigators weighed theories that there was more than one capsule-tamperer—a hypothesis posited because some of the capsules had clearly been modified, while the spiking of others was far better disguised. The nation’s top sleuths came up empty-handed.

INNOCENT VICTIM

One of the more promising early suspects was a man named Roger Arnold, who had worked alongside the father of one of the victims in a Jewel Food Stores warehouse. Arnold, then 48, was arrested in October 1982 after a tip-off that he had cyanide in his home. Police interrogated Arnold for three days, after which they dismissed any link between him and the Tylenol deaths. Arnold considered his life ruined, however, and wanted revenge against the secret informant. In January 1983, he targeted a Chicago man he believed had directed investigators his way. Arnold shot and killed John Stanisha—a 46-year-old computer consultant and father of three who police say was never an informant. Arnold lamented the death years later. “I killed a man, a perfectly innocent person,” he said from prison in 1996. “I had choices. I could have walked away.”5

The most likely break in the case came courtesy of a brazen extortionist. Within two weeks of the deadly outbreak, Tylenol’s makers, Johnson & Johnson, received a letter promising to stop the killings for $1 million. The letter, immediately given to the FBI, was traced to James W. Lewis of New York City.

Lewis’ letter was dismissed as heartless opportunism, but he still routinely appears as the frontrunner on lists of suspects—largely because no one else has emerged to unseat him. There are certain suspicious factors. At one point in his checkered past, Lewis and his wife LeAnn had imported pill-making machines from India; and when he and his wife had first moved to Chicago, they had lived under false names as Robert and Nancy Richardson. Additionally, Lewis had once been charged with bludgeoning and dismembering a Kansas City man. Those charges were dismissed after a judge ruled that Lewis’ arrest and the seizure of his property were illegal. As recently as 2009, federal authorities searched Lewis’ home hoping to discover new clues. Nothing was found.

Two years later, the FBI took a DNA sample from Ted Kaczynski, the man famously dubbed the Unabomber for mailing 16 homemade bombs that killed three people and injured more than 20 between 1978 and 1995. Imprisoned since 1996, Kaczynski was on the police’s radar because he had lived with his parents in suburban Chicago during the Tylenol murders. Every lead led to big headlines, but nothing more.

SAFETY FIRST

The only solid progress ever made in the case involved packaging. Within days of the deaths, legislators proposed new laws requiring manufacturers to seal drug containers. The little foil seals are commonplace now, but prior to young Mary Kellerman collapsing in her bathroom, all that stood between a malevolent would-be tamperer and a stranger’s medicine was a twist-off lid and a wad of cotton.

Pishos, one of the original investigators, recently lamented that the killer remains nameless after all these years. “It’s frustrating for everybody,” he said, “more so for the families who were victims not being able to put this person or persons behind bars.”6

DRUGSTORE LOCATIONS

Jewel Food Store

Jewel Food Store

Walgreens Drug Store

Walgreens Drug Store

Jewel Food Store

Jewel Food Store

Osco Drug Store

Osco Drug Store

Frank’s Finer Foods

Frank’s Finer Foods

Chicago in the 1980s.