THE HINTERKAIFECK MURDERS, 1922

THE BODIES IN THE BARN

Few unsolved murders encompass so many dark secrets and raise so many disturbing questions as this lurid, spooky tale of incest, jealousy, and mystery.

Hinterkaifeck was the name of a small, isolated farmstead situated in the beautiful rolling hills and forests between the towns of Ingolstadt and Schrobenhausen in Bavaria, Germany. It was the home of Andreas Gruber, 63; his wife, Cäzilia, 72; their widowed daughter, Viktoria Gabriel, 35, and her children, Cäzilia, 7, and Josef, 2; and also the new maid, Maria Baumgartner, 44. In the dead of night, on March 31, 1922, someone systematically slaughtered each member of the family one by one and piled their bodies in a barn.

THE GRUBER FAMILY

Andreas Gruber was not a popular man in the local commuinity. He was thought to be aggressive and greedy, and people in the nearby village generally avoided him. Viktoria was the only child of Andreas and Cäzilia to have survived into adulthood; locals speculated that their other children had perished because they were not looked after properly and were treated cruelly. “The small children had to stay in the cellar for days and when you passed by, you could hear the children crying,” a neighbor recalled.

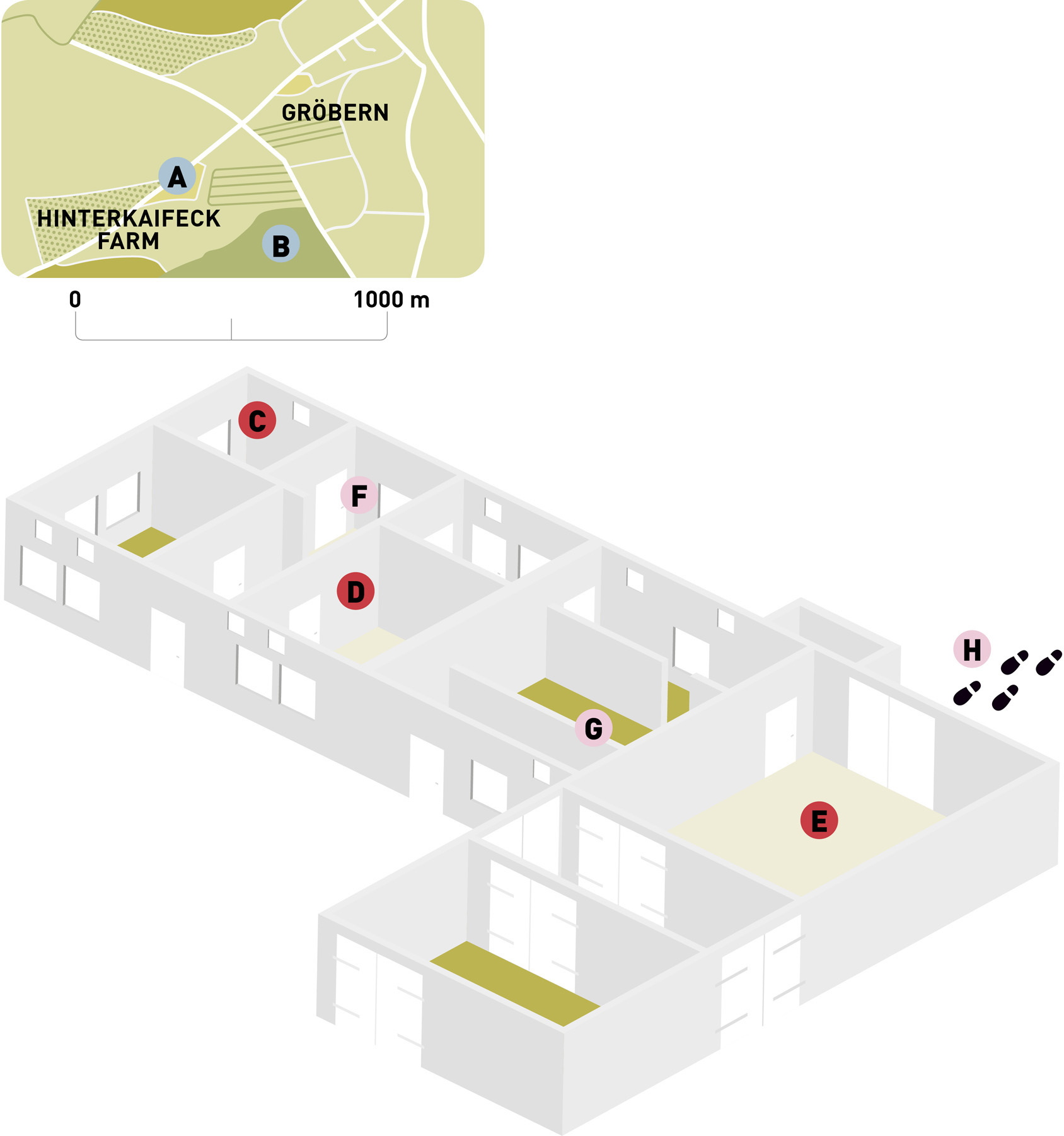

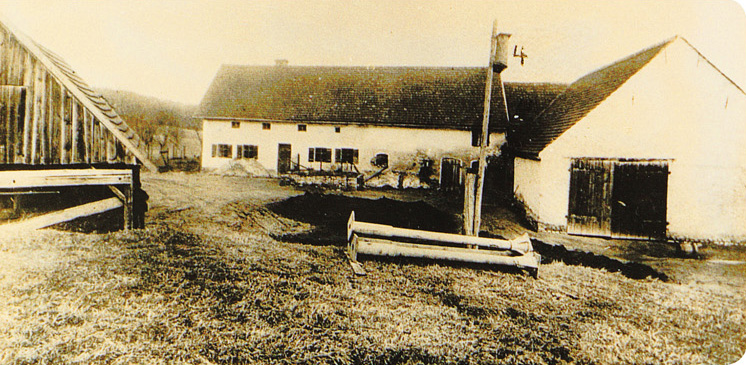

Main image: A contemporary reconstruction of the crime scene.

Top to bottom: Hinterkaifeck Farm, a few days after the crime. The barn, where the murders took place, is on the right; Maria Baumgartner’s body in her bedroom; the bedroom where Viktoria slept with her two children; the crime scene, as first encountered by the police.

Even more damaging to Andreas’ reputation was the public knowledge that he was having an incestuous relationship with Viktoria, whose husband, Karl Gabriel, had died in France in 1914 during World War I. The year after his death, Andreas and Viktoria were convicted of incest between the years 1907 and 1910. Viktoria was sentenced to one month and Andreas to one year in prison. It was also rumored that Andreas was the real father of little Josef and not the village mayor, Lorenz Schlittenbauer, with whom Viktoria had also been having an intimate relationship at the time she became pregnant. Lorenz had reportedly wanted to marry Viktoria, but he had been stopped by Andreas, who had angrily chased him away from the farm with a scythe. Kreszenz Rieger, the Gruber’s maid before Maria Baumgartnerr, later told police that she had overheard Andreas telling Viktoria that “she does not need to marry, because as long as he lives, he is there for ‘this.’” The maid claimed that, by “this,” Andreas was alluding to the fact that he was there to sexually satisfy his daughter, so she didn’t need a husband.1

STRANGE GOINGS-ON

In the days leading up to the murders, Andreas told neighbors about some odd occurrences that had been unfolding at the farm. A Munich newspaper was discovered on the kitchen windowsill, which the family found peculiar because it was not a local newspaper. When Andreas questioned the postman, Joseph Mayer, about it, he denied that he had delivered the newspaper to anybody in the area. When Andreas looked out at the snow-covered farmland, he noticed footprints leading from the edge of the nearby dark forest to the farm, but none leading back. Was there a trespasser? Was someone watching the family? Kreszenz Rieger certainly thought so. While working at the farm, she was so convinced that somebody—or something—was lurking in the shadows of the forest that, just months before the murders, she packed her bags and fled, never to return. At around the same time, the house keys disappeared from Andreas’ desk and somebody attempted to break into the engine yard.

Andreas also voiced concerns that livestock was missing and that somebody was creeping around in his attic. Over the course of several nights, he heard strange noises coming from above, but when he went to investigate, he found nothing. His neighbor urged him to go to the police but Andreas refused, saying, “I know how to defend myself.”

While these incidents were cause for concern, nobody could have expected what happened next. From April 1, 1922, the entire Gruber family seemed to have vanished. Cäzilia did not appear at school that day—a Saturday—and the family didn’t attend church on Sunday.

April 4, 1922 / The bodies of the Gruber family are discovered.

Three neighbors decided to investigate. Discovering that all of the doors were locked, they broke into the barn adjoining the farmhouse. Daylight penetrating the murky barn illuminated a ghastly sight: the bludgeoned bodies of Andreas, his wife Cäzilia, Viktoria, and her daughter Cäzilia, piled up among the hay. From the barn, the neighbors were able to enter the farmhouse, where they found the lifeless bodies of the maid, Maria, and little Josef.

THE INVESTIGATION BEGINS

The police concluded that the first four victims had been lured one by one to the barn and murdered before they could even cry out. The killer stacked their bodies one on top of the other and partially covered them with hay and an old door that had been dumped in the barn. He then went into the farmhouse, where he killed Josef, who was asleep in his cot, and Maria. He covered their bodies with clothing and sheets.

Each victim had been bludgeoned with a mattock—a pickaxe-like farming tool—on the face and head. The elder Cäzilia also showed signs of strangulation. While the majority died a quick, albeit vicious, death, the younger Cäzilia took several hours to die. The pathologist discovered tufts of her hair tangled in her fingers and in her hands. She had apparently pulled some of it out as she lay dying.

The pathologist estimated that the murders took place at around 9:30 p.m. on March 31. Furthermore, the killer did not immediately flee the grisly scene—he remained at the farm for several days, feeding and milking livestock and helping himself to bread and ham from the pantry. Neighbors later claimed that they had seen smoke coming from the farmhouse chimney.

Schrobenhausen police were called in to assist in the investigation, but after realizing that they were in over their heads, the more experienced Munich force took over the case. Their initial theory was that the killer was a vagrant, motivated by the family’s considerable wealth. However, a search of the farm indicated that gold coins and jewelry had been untouched, and no belongings or livestock were missing.

When police questioned local residents, the name Josef Bartl came to their attention. Bartl was a serial robber who had once escaped a mental asylum. In 1919, he had robbed the Alder family in the small village of Ebenhausen, about 13 miles (21 km) from Hinterkaifeck. Many speculated that only a madman like Josef would have remained at the crime scene, living alongside the bloody bodies of his victims for so many days. However, other than the most tenuous circumstantial evidence, nothing tied him to the crime.

PAST LOVES

Mayor Lorenz Schlittenbauer, who had once wanted to marry Viktoria and had possibly fathered Josef, was a prime suspect throughout the investigation. He was one of the three neighbors who discovered the bodies and he lived the closest to Hinterkaifeck farm. He had clashed violently with Andreas over his relationship with Vicktoria, and had even reported them to the authorities for their incestuous relationship. According to the other neighbors on the scene, Schlittenbauer was also said to have been remarkably unfazed when the Grubers’ bodies were discovered, despite the gruesome nature of what they found. Admittedly, this outwardly calm behavior could be attributed to shock.

March 30, 1931 / Lorenz Schlittenbauer is interrogated about the murders once more.

Lorenz Schlittenbauer was interrogated at the crime scene on April 5, 1922. At the time of the murders, he claimed he was a happily married man with no motive for killing the entire Gruber family. Nevertheless, even today, Schlittenbauer remains a favorite suspect among the townsfolk of Ingolstadt. Schlittenbauer’s family still lives in the town and still has to endure the whispers and speculation that he was the killer, even though, as his son Alois pointed out, “there has never been an indictment.”

One of the more outlandish suspects was Viktoria’s ex-husband, Karl Gabriel, who had supposedly died in the trenches in 1914. His body was never actually retrieved, leading the Schrobenhausen chief of police, Ludwig Meixl, to suggest that perhaps Gabriel had not died at all. If he had survived, he could have traveled to Hinterkaifeck and committed the murders, perhaps in revenge for his wife’s incestuous affair with her father. However, on December 12, 1923, Karl Gabriel’s death was officially confirmed by the Central Prosecution Office for War Losses and War Graves, and he was officially ruled out as a suspect in the case.

OTHER POSSIBILITIES

Another surprising suspect was the cruel and controlling head of the family, Andreas Gruber himself. Author Adolf Jakob Köppel argued in an article in the Munich newspaper Abendzeitung that the mattock used to kill the victims was handmade by Gruber himself and would have been difficult for an untrained person to wield with such deadly efficiency.2 However, this theory fails to explain how Andreas could have inflicted such fatal injuries on himself.

“THE DEVIL CAME TO HINTERKAIFECK—BUT HE WAS ALREADY THERE…”

Twenty years later, in 1941, an elderly neighbor, Kreszentia Mayer, made a deathbed confession to her priest, Anton Hauber. She stated that her brothers Adolf and Anton Gump were responsible for the Hinterkaifeck murders. She explained that her oldest brother, Adolf, had been in an intimate relationship with Viktoria and had been infuriated when he became aware of Viktoria and Andreas Gruber’s incestuous relationship.

According to Kreszentia Mayer, Adolf and Anton had killed Viktoria and Andreas Gruber, and then dispatched everyone else living at the farm to ensure that there would be no witnesses to reveal their crime. However, it was not until 1952 that police decided to investigate the brothers’ possible guilt. By this time, Adolf had been dead for eight years and Anton was an elderly pensioner who categorically denied any involvement in the murders. He was arrested but, after three weeks in custody, released without charge.

A DARK LEGACY

The combination of the unexplained footprints in the snow leading from the forest to the farm, and the mysterious sounds apparently coming from the attic, paint a frightening picture of a sadistic intruder hiding in the house and waiting for his moment to strike. This picture continues to fascinate professional and amateur sleuths many decades after the slayings. However, the sheer lack of evidence, incomplete case records, and the deaths of potential witnesses and suspects means that it is doubtful the mystery of the Hinterkaifeck murders will ever be solved. During the chaos of World War II, a significant number of the police files were destroyed. In addition, all six of the victims’ heads, which had been sent to the Pathology Institute of the University of Munich for analysis, also disappeared.

One year after the mass murders at Hinterkaifeck, a court order was given for the farmhouse and outbuildings to be demolished. A small marble monument near the original site, along with six graves for the family and their maid, is all that now remains to mark the horrors that unfolded all those years ago.

HINTERKAIFECK FARM

Farm location

Farm location

Forest

Forest

Maid’s bedroom—Maria’s body

Maid’s bedroom—Maria’s body

Children’s bedroom—Josef’s body

Children’s bedroom—Josef’s body

Bodies of Andreas, Cäzilia senior, Viktoria, and Cäzilia junior

Bodies of Andreas, Cäzilia senior, Viktoria, and Cäzilia junior

Kitchen

Kitchen

Barn

Barn

Footprints to the house

Footprints to the house

Hinterkaifeck farm, some 251 meters (275 yards) from the outskirts of Gröbern.