THE VILLISCA AX MURDERS, 1912

THE SHROUDED HOUSE

The residents of Villisca, Iowa thought of their little town as a friendly, neighborly place. This illusion was shattered by a single, terrible event. Life in Villisca would never be the same again.

June 10, 1912, was a quiet Monday morning in the farming town of Villisca, Iowa. Too quiet, in fact. A woman named Mary Peckham was bustling about doing her chores when she noticed an “odd stillness” at about 7:00 a.m. Normally by this time, Mary’s neighbors would be bustling, too. Instead, aside from the impatient mooing of cows waiting to be milked in the field, their house was silent.

The house next door belonged to the Moore family—parents Josiah B. (a businessman known as either J.B. or Joe) and Sarah, and their four children: 11-year-old Herman, 9-year-old Katherine, 7-year-old Boyd, and 5-year-old Paul. With that many kids, the home was rarely quiet. Worried, Mary called J.B.’s brother Ross, who used his key to get inside. He saw blood and asked her to fetch the town marshal.

BLOODBATH

Marshal Henry “Hank” Horton was similarly shaken after walking through the silent house. “Somebody murdered in every bed,” he muttered1 as he went to fetch Dr. J. Clark Cooper, the first physician to examine the scene. Inside the house, the entire Moore family had been brutally slain, as had two young friends of the family, Lena and Ina Stillinger. The killer had wielded an ax, using the blade to kill his victims and then the handle to bludgeon their faces beyond recognition, before covering the heads with bedclothes. The mutilation was so severe that one Iowa newspaper misidentified the Stillinger girls as another pair altogether.

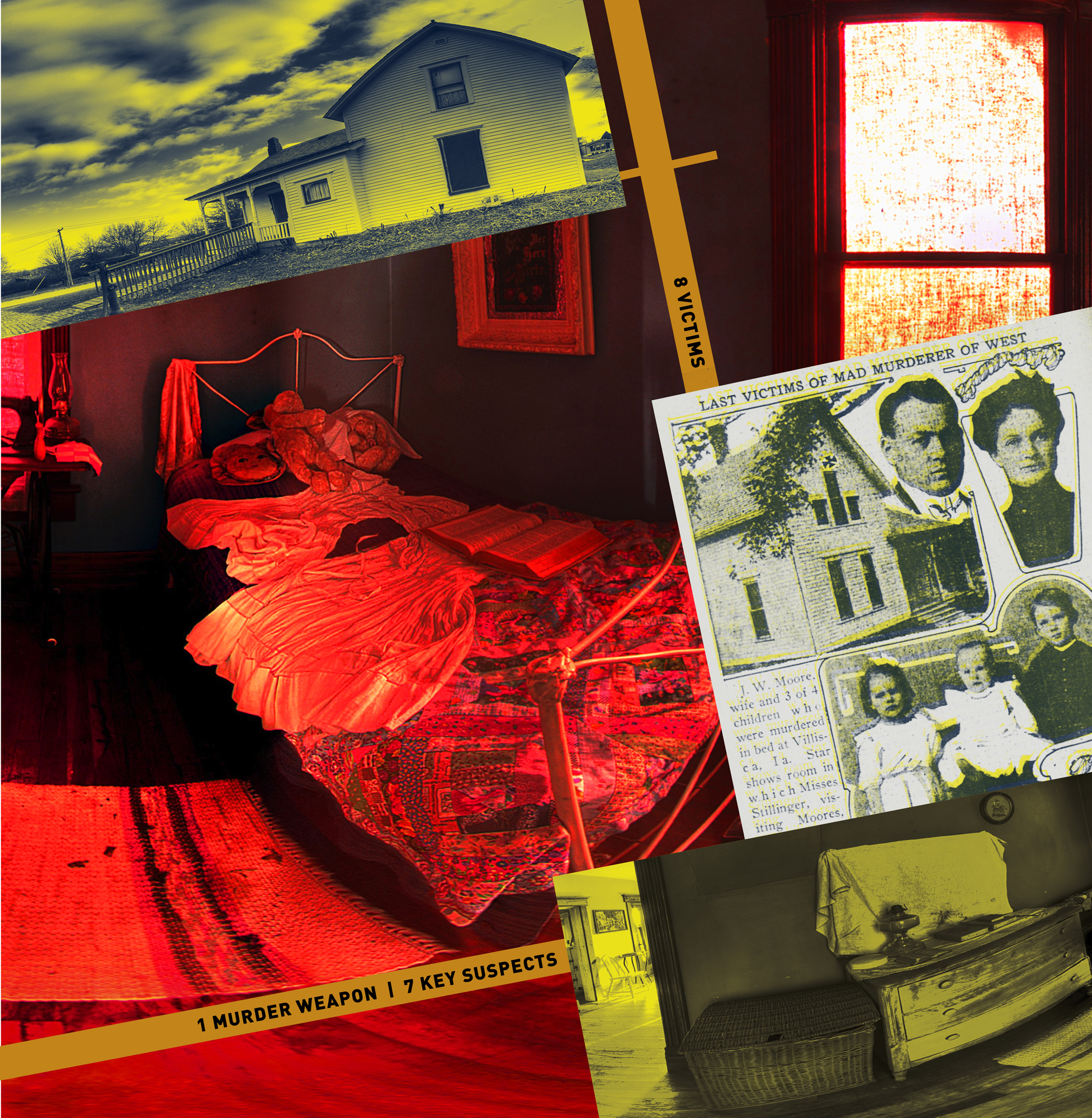

Main image: The parlor bedroom in the Moores’ house.

Clockwise from top: Exterior of the Moore family house; a Villisca Review newspaper article on the murders; a sheet-covered mirror in the parlor bedroom.

The night before the deaths, J.B. and Sarah were at the local Presbyterian church watching their children perform Children’s Day exercises. Lena and Ina also took part, and the two girls—aged 11 and 8, respectively—were invited to stay the night at the Moore home. The young guests were in a downstairs bedroom, while the rest of the family was upstairs. Investigators determined Lena and Ina were the first victims—and that one of them had awakened, judging by a defensive wound that suggested she’d thrown up an arm to ward off a blow. It’s possible that Sarah had also awoken during the attack. One neighbor told police she thought she heard Sarah’s voice in the night yelling: “Oh! Dear! Oh! Dear! Don’t! Don’t! Don’t!”

“ALL THE BODIES WERE FOUND IN A NATURAL SLEEPING POSTURE WITH HEADS BEATEN ALMOST TO A PULP.”

It appeared the killer had taken pains to conceal himself. The blinds had been tightly drawn closed on the windows. Glass doors had been covered with articles of clothing. Even the mirrors inside the house had been shrouded. The attack was not a robbery, as no valuables were taken or even disturbed. It seemed that the killer wasn’t in a rush: he had taken time to partially clean the murder weapon before leaving it propped against the wall of the downstairs bedroom.

The crime scene had some odd elements that still perplex researchers today. One four-pound slab of bacon was left leaning against the wall next to the ax, while another piece of bacon was found on the piano in the parlor. On the kitchen table was a plate of uneaten food and a bowl of bloody water. It’s perhaps noteworthy, too, that Lena’s nightgown had been pushed up, leaving her exposed—though doctors determined she had not been sexually assaulted.

MURDER HOUSE CALLERS

The police made a crucial error in failing to immediately secure the crime scene, allowing dozens of people to trample through the murder house. One suspect actually had a portion of skull in his possession that he bragged to several witnesses belonged to J.B. However, this man was able to plausibly explain he had simply picked up the piece of bone off the floor as he gawked.

The investigators’ best guess was that the killer must have been a relative of the family, and early reports tossed out some names: Samuel Moyer, a brother-in-law of J.B., and John Van Gilder, a former brother-in-law of Sarah. Townspeople racked their brains for clues and alerted police to every stranger they’d seen or bizarre scenario they’d witnessed. Many of the resulting “tips” ultimately proved useless.

May Van Gilder, the 16-year-old niece of J.B. and Sarah, said the Saturday before the murder, a stranger asked her where the Moores lived. When the girl later told Sarah of the query, Sarah reportedly replied that someone matching the description had been hanging around the home. That exchange prompted police to arrest a man in bloodstained shoes named Joe Ricks in Monmouth, Illinois. When May traveled to identify him, she said they had the wrong man.

Another dead end came when a supposed expert named C.M. Brown reached out to detectives and offered to obtain an image of the killer from the retina of Lena. The theory was that because Lena had awoken, the last sight she saw was the killer—and that image would be imprinted on her retina much like a photograph. Detectives agreed, and Brown said he recovered an image that “indicates a man of stout build, very broad shoulders, and extraordinary length between the shoulders and hips.”2 Unsurprisingly, nothing came of it.

June 9, 1912 / Strangers spotted near the Moores’ house.

However, some tips were more promising. Cora McCoy, who lived two blocks from the Moore house, said she saw two strangers walk by at about 3:00 p.m. on Sunday afternoon, the day before the murders. The men walked close together, as if talking confidentially. McCoy said she saw them again at dusk. One of them looked like a man named William “Blackie” Mansfield, a supposed Army deserter and “cocaine fiend” who, two years after the Villisca murders, was suspected in the similar ax slaying of his wife, daughter, father-in-law, and mother-in-law.

Another neighbor of the Moore family, Mary Landers, also saw two strange men walking toward their house. She said they paused to look at Moore’s ax, which was in a chopping block in the yard.

CONSPIRACY THEORY

Several witnesses said that they spotted Iowa Senator Frank F. Jones and his son Albert in town at the time of the murders. On the surface, this might seem harmless, but J.B. had worked for the elder Jones’ farming equipment company before leaving to start a competing business. Jones was reportedly upset by his departure—and by his nabbing of a lucrative John Deere contract. There were also rumors that J.B. was having an affair with Jones’ daughter-in-law, Dona. It all made for bad blood—but was it enough to kill?

Local men Fred Fryer, Frank Milhiller, and Verne Robinson all reported seeing J.B. talking with Sen. Jones’ son a few hours before the murders. Another man, Jim Bridewell, said he saw Albert Jones with Villisca pool hall owner W.B. “Bert” McCaull. Garage owner E.M. Nelson said he spotted McCaull behaving suspiciously and in a rush about 9:00 p.m. the night of the slayings, while several witnesses said McCaull had shown them a piece of bone that he said came from J.B.’s skull.

These witness statements led to theories that Sen. Jones, Albert Jones, Blackie Mansfield, and Bert McCaull worked together. A detective named James Wilkerson, who worked for the renowned Burns Detective Agency, was hired to investigate the killings after police came up empty-handed. In 1916 he announced he had solved it, stating that Sen. Jones had hired Mansfield to murder J.B. for hurting his business. The theory was bolstered by testimony from Alice Willard, a Villisca busybody recruited by Wilkerson to help investigate the case. Willard said that the night of the murder, she and two other women had driven home from Lincoln, Nebraska, when their car broke down near the Moore house. As she reached the back corner of the Moore lot, she saw five men talking in hushed voices. While she couldn’t hear much of their conversation, she said she picked out some key words and phrases: “money,” “Sunday,” “after church,” and “get Joe first, the rest will be easy.” She recognized one of the men as Sen. Jones.3

Wilkerson’s claims were heralded with huge headlines: GREAT CRIME AT VILLISCA IS NOW SOLVED read one from Marshalltown, Iowa. The story claimed that Mansfield not only had been hired to kill J.B. Moore, but he also was responsible for the double ax murders four days prior in Paola, Kansas. The allegations against Mansfield were brought before a grand jury, but Mansfield’s employer provided records saying he had been in Illinois at the time of the murders. Mansfield was never charged. That didn’t stop Ross Moore (J.B.’s brother) or Joe Stillinger (Lena and Ina’s father) from believing Wilkerson’s theory.4

SERIAL AX KILLER?

Neither Villisca nor the Paola killings were the only ax murders of the era. There was a string of similar killings throughout the Midwest, many of which were ascribed to Henry Lee Moore (no relation to the Moores of Villisca). Moore was found guilty of the murder of his mother and grandmother in December 1912, and US Department of Justice agent M.W. McClaughry theorized that he could be responsible for as many as 23 more—including the Villisca deaths.

McClaughry pointed to similarities beyond the murder weapon. Each victim was slain in their homes with exceptional brutality. In each case, the bloody ax was found nearby. He also noted that the ax murders started in late April 1911 and stopped in mid-December 1912—a window of time during which Henry Moore was out of prison.

In their book, The Man From the Train5, Bill James and Rachel McCarthy James claimed that Paul Mueller, a German immigrant farmhand, was a serial killer who traveled by train and killed families with their own axes. The Villisca slaying is one of many killings they pinned on this elusive character. Some townspeople said that they had spotted Mueller shortly before midnight on the night of the murders, and he seemed to be in a rush. After the bodies were discovered, a nationwide manhunt ensued, with Mueller reportedly holing up in Wisconsin, New York, Pennsylvania and beyond. He was never found.

PEEPING TOM

One suspect was actually tried for the Villisca deaths. The morning the bodies were found, a reverend by the name of Lyn George Kelly left Villisca by train at about 5:20 a.m. On the train—long before the bodies had been discovered—he allegedly told fellow travelers that there were eight dead souls back in town who had been butchered in their beds. Word of this prompted investigators to take a close look at Kelly, who had arrived in town the morning of the murders and even attended the Children’s Day in which the youngsters had performed.

Two weeks after the murders, Kelly returned to Villisca and posed as a detective, joining a tour of the murder house. He inserted himself further into the case by claiming that, at about 1 a.m., he had actually heard the thud of the ax that killed the eight victims.

Kelly had a history of mental illness and related odd behavior. “He was schizophrenic, there was no doubt about that,” said Ed Epperly, a PhD at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, who studied the case for nearly 40 years. “I think (the motive) was sexual.” Epperly points to the uplifted nightgown on one of the victims and draws a parallel between that and Kelly’s habit of “window peeking.” Kelly had also been charged twice with sending obscene materials in the mail, asking young girls to pose nude for him.

A TOWN DIVIDED

In 1917, a grand jury heard evidence against Kelly and indicted him for the Villisca murders. As he awaited trial, Kelly even signed a confession to the murders, saying God had told him, “Suffer the little children to come unto me” and “slay, slay utterly.”6 However, Kelly recanted the confession at trial, and the jury deadlocked 11 to 1 for acquittal. A second jury acquitted Kelly in November 1917. The townsfolk in Villisca were split in their beliefs. Some residents thought Sen. Jones was the culprit, while others were convinced Kelly was the killer. “It really tore the community apart,” said filmmaker Kelly Rundle, who made a movie about the murders called Villisca: Living with a Mystery.

The case has also acquired a supernatural aura. The Villisca house has been investigated by numerous “ghost hunters,” who claim to have encountered paranormal phenomena, helping to make the building a tourist attraction. Visitors can even stay there overnight.

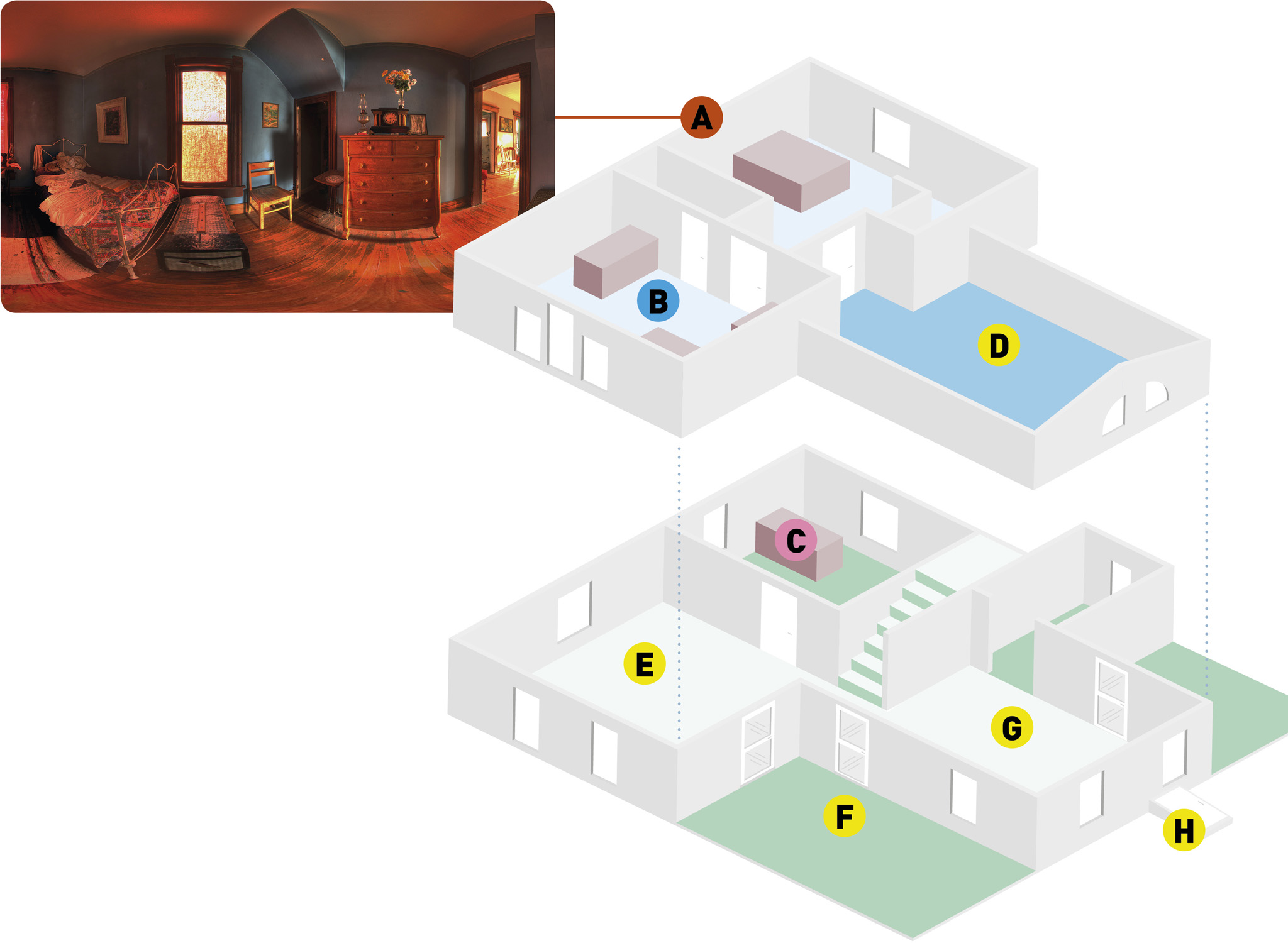

THE VILLISCA HOUSE

Bodies of J.B. and Sarah Moore

Bodies of J.B. and Sarah Moore

Bodies of Herman, Katherine, Boyd, and Paul

Bodies of Herman, Katherine, Boyd, and Paul

Bodies of Lena and Ina Stillinger

Bodies of Lena and Ina Stillinger

Attic

Attic

Parlor

Parlor

Front porch

Front porch

Kitchen

Kitchen

Stairs to cellar

Stairs to cellar