WILLIAM DESMOND TAYLOR, 1922

A HOLLYWOOD WHODUNIT

It was a thriller plot fit for the movies: A famous film director mysteriously murdered in his home. For extra glamor, some of the suspects were genuine stars of the silver screen. For extra spice, William Desmond Taylor had a secret past…

The name William Desmond Taylor is no longer familiar to modern moviegoers, but in the 1910s and 20s, he was a prolific director whose name routinely appeared in gossip columns alongside that of one beautiful actress or another. He worked with legends of the silent film era—Mary Pickford, Myrtle Stedman, and Wallace Reid—and lived in a stylish bungalow in a sought-after Los Angeles “movie colony” neighborhood. To his Hollywood friends, William Desmond Taylor seemed to have it made.

Such was the case until the morning hours of February 2, 1922, when Taylor’s valet and cook, Henry Peavey, found his lifeless body lying face-up on the floor of his study. Peavey ran screaming from the bungalow into the apartment building’s courtyard. At first, it appeared that the 49-year-old director must have succumbed to natural causes. His suit was unmarked, said a neighbor, the actor Douglas MacLean, who rushed to William’s home as soon as he heard Peavey’s cries. “He was lying flat on his back, his feet separated a little, his hands at his side, perfectly flat on his back,” MacLean commented. “I said to Mrs. MacLean, later on, ‘He looked just like a dummy in a department store, so perfect, so immaculate.’”1

Clockwise from left: William Desmond Taylor; movie star Mabel Normand; Margaret Gibson, a.k.a. Patricia Palmer; Taylor’s valet, Henry Peavey; Taylor’s former valet, Edward F. Sands; Mary Miles Minter as Cleopatra; Charlotte Shelby (left) and daughter Mary Miles Minter, some 15 years after the murder.

Movie mogul Adolph Zukor, president of Famous Players-Lasky, Hollywood’s preeminent studio, was desperate to hush up the potential scandal of Taylor’s death. Before the police arrived, he sent employees around to Taylor’s house to remove any bootleg liquor or compromising material. They also told Peavey to clean up the crime scene.

As soon as the police turned the dead man over, it was obvious that Taylor had not died a natural death. He was lying in a pool of blood, with a bullet wound in his back. From the angle of the wound, the gun had probably been fired by someone standing just over 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall, possibly while embracing Taylor.

William Desmond Taylor’s murder would become one of Hollywood’s darkest legends, with every twist and turn of the investigation lapped up by the press. Gossip peddlers could not have wished for better material.

THE FIRST SUSPECT

Unfortunately for actress Mabel Normand, the police’s inevitable first step was to suspect whoever last saw the victim. Considered one of the top comediennes of the era, Mabel had huge, expressive eyes, and dark hair, cropped flapper-style. By 1922, she was working for Goldwyn Studios for about $1,000 a week—the equivalent of nearly $15,000 today. She also had a drug and drinking problem; coincidentally, perhaps, Taylor was famously on a crusade to rid Hollywood of drugs.

February 1, 1922 / Mabel Normand is the last known person to visit William Desmond Taylor at his home.

Normand denied knowing anything about the murder, claiming that her visit was completely innocent. Taylor had bought her a book and called her to pick it up. She arrived between 7:00 and 7:15 p.m.; they talked about literature and theater; and then, after about half an hour together, he walked her to her car and they waved goodbye. “Please tell the public that I know nothing about this terrible happening and that Mr. Taylor and I did not quarrel,” she said in a press statement.2

After being repeatedly questioned, Mabel Normand was dismissed as an official suspect, though a cloud of suspicion remained over her. As recently as 1990, author Robert Giroux put forth a theory that William’s determination to help Mabel beat a cocaine addiction angered her drug dealers, and so they killed him in revenge.

A TEENAGE CRUSH

Search newspaper mentions of William Desmond Taylor in the months leading up to his death, and nearly every story includes the name of 19-year-old up-and-coming actress Mary Miles Minter. Born Juliet Reilly in 1902 in Shreveport, Louisiana, Mary was a doe-eyed beauty in the mold of Mary Pickford—though 10 years younger.

Taylor had directed Mary in the 1919 silent film, Anne of Green Gables, in which she played the title role, and he was known to be invested in her career. After his death, investigators found love letters from Mary among Taylor’s effects. The notes were written in a silly code “known to thousands of youngsters,” while one read “I’d put on something soft and flowing… I’d wake to find two strong arms and two dear lips pressed on mine in a long, sweet kiss.”3 This implied a far more intimate relationship than even Taylor’s closest friends had realized. While Mary’s mother tried to downplay her daughter’s declarations, saying that Mary loved William “as a child would her father,”4 Mary herself said otherwise, referring to him as the love of her life.

“I LOVED HIM DEEPLY… WITH ALL THE ADMIRATION AND RESPECT A YOUNG GIRL GIVES TO A MAN WITH HIS POISE AND UNFAILING CULTURE.”

Reporters latched onto Mary’s romantic revelations, painting her as both virginal and a temptress—a young woman who mistook William’s kindness as something more. No evidence surfaced that he ever returned Mary’s affection. After his death, rumor was that he was actually gay or bisexual. One typically lurid story in the New York Daily News reported that William engaged in “unmanly rituals” as part of an opium cult.

Taylor and Minter’s secret relationship was enough to warrant interrogation. The fact that she had no alibi, and that police believed three long blonde hairs found on Taylor’s jacket were hers, helped to ensure her name would be forever linked to the case. In 1937, 15 years after the murder, police made it clear that Mary was still a prime suspect when they subpoenaed her, her mother, and her sister, claiming they had uncovered “new evidence.” Mary publicly demanded that the authorities should either clear her name or try her for murder. Neither ever happened.

FATAL ATTRACTION

Nevertheless, Mary has remained a suspect. The writer Charles Higham suggested in his book, Murder in Hollywood: Solving a Silent Screen Mystery, that Mary was jealous of his affairs with other women and men5. Higham posits that, the night of the killing, Mary turned up at William’s home with a gun and threatened to kill herself if he would not return her love. He calmed her down, but she was still holding the gun as they embraced and accidentally shot him.

As quickly as Mary Miles Minter’s name hit the headlines as a possible suspect, so, too, did her mother’s. Charlotte Shelby had been a Shakespearean actress who had appeared on Broadway in at least one production, but her stardom fell as she raised her two daughters—Mary and Margaret Fillmore. By some accounts, there was no love lost between Charlotte and William Desmond Taylor. Charlotte’s former secretary told a district attorney attached to the case that she heard Charlotte tell Taylor, “If I ever see you hanging around my Mary again, I’ll blow your goddamn brains out.”

THE MATRIARCH

On the surface, it would seem ludicrous to think Charlotte would want Taylor dead. He was, after all, shepherding her daughter’s career—and thus helping the whole family financially. Some commentators posited that Charlotte was merely a protective mother trying to shield her young daughter from a man nearly three times her age. Mary herself rebuffed that notion: “Mother’s actions over Mr. Taylor’s attentions to me were not inspired by a desire to protect me from him. She was really trying to shove me into the background so that she could monopolize his attentions and, if possible, his love.”6

Even more damning were comments—and court testimony—provided by Charlotte’s older daughter, Margaret. According to her, neither Mary nor Charlotte was home between 7:00 and 9:00 p.m. on the night of the murder. Mary eventually arrived in a “hysterical condition,” while Charlotte did not come home at all. “I knew she was out all day and night hunting for certain men to learn Mary’s whereabouts … [She] later came in and told us that Taylor had died.” Margaret told police that her mother had tossed “the gun” into a river in Kansas City. Soon after, Charlotte had Margaret committed to a psychiatric ward.

Beyond the daughters’ incriminating statements about Charlotte’s possible role in Taylor’s death, police uncovered convincing circumstantial evidence against the matriarch. She allegedly owned both the type of gun, and the rare, soft-nosed ammunition used in the killing.7 While this was not enough to convince a grand jury, it was plenty to convince Ed King, one of the lead investigators on the case, who went to his grave believing Charlotte Shelby got away with murder.

DOUBLE IDENTITIES

The list of suspects does not end with Charlotte Shelby. Suspicion also surrounds the dead man’s chauffeur and his own brother. The roots of this theory lie in Taylor’s early life—one he abandoned 14 years before his death. He was born in 1872, not as William Desmond Taylor, but William Cunningham Deane-Tanner. The eldest son of a wealthy landowner and the grandson of a British member of parliament, William was raised in Mallow, Ireland, with a younger brother named Denis Gage Deane-Tanner. William longed to become an actor, and disappointed his family by refusing to join the British army, joining a theater group in Manchester, England, instead. He bounced around the UK and then Canada, before landing in New York City, where Denis joined him. The two opened an antique store on Fifth Avenue.

In 1901, at the age of 29, William married Ethel Harrison, the niece of a real-estate tycoon, and the two had a daughter named Ethel Daisy. In 1908, William is said to have emptied his bank account and vanished, leaving no forwarding address for his wife and child. Ethel would eventually learn that her husband had moved to Hollywood when she and her daughter saw him on the silver screen using a new name.

Four years after William disappeared, so did his brother, Denis, in similar fashion. His wife said he left the house with his hat and walking stick, as though going to work, never to return. Neither his wife nor his two small children ever heard from him again.

Some time in 1920, Taylor hired a man named Edward Sands to be his chauffeur. A year before his murder, he and Sands had a falling-out. Taylor accused the chauffeur of stealing from him and threatened to have him arrested. Sands disappeared shortly before the shooting and was sought by police as a potential suspect.

This all serves as a backdrop to one of the more convoluted theories surrounding Taylor’s death: That Denis had assumed the identity of Edward Sands and—after falling out with his more successful brother—had shot him. This theory even made the newspapers, as evidenced by a 1936 Associated Press story that asked: “Was the ‘Edward Sands’ who presumably acted as his valet, really his brother, Dennis (sic)?” Denis’ abandoned ex-wife, Ada, tried to clear his name, insisting that the brothers were “very much devoted to each other” and providing police with photos, documents, and handwriting samples. Neither Denis—nor Sands—ever resurfaced, however, so the conjecture continues.

THE GIBSON GIRL

In 1964, 42 years after the elusive killer struck, a woman named Pat Lewis declared on her deathbed that she had killed William. On its own, this confession would not mean much—police claimed that the case had garnered some 300 confessions within the first six weeks of the investigation—but a family friend did some digging and found there was perhaps something to Pat Lewis’ claims.

Lewis had once been known as Patricia Palmer and, before that, had achieved some movie-star fame as Margaret “Gibby” Gibson. By 1964, she was a recluse living in a small house in the Hollywood Hills. When she suffered a heart attack, she demanded a priest and began confessing her sins—namely that while she was a silent-screen actress, she had shot and killed William Desmond Taylor. “And she continued by saying that they nearly caught her and that she had to flee the country,” wrote Raphael F. Long in a piece published by Taylorology, a newsletter dedicated to the murder.

Bruce Long, author of William Desmond Taylor: A Dossier, hypothesized in the same newsletter that Gibson had, like Mary, fallen in love with William—ultimately killing him in a “if I can’t have him, no one can” frenzy.8 William J. Mann, author of Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood, suggests that the actress was trying to blackmail Taylor over the family he had abandoned and had recruited help from local crime boss, Blackie Madsen, and known blackmailer, Don Osborn. Mann posits that one of those men, rather than Gibson herself, pulled the trigger.

In movies, this compelling mystery would surely have a clear ending. However, it became clear long ago that the murder of William Desmond Taylor will never have a satisfying third act.

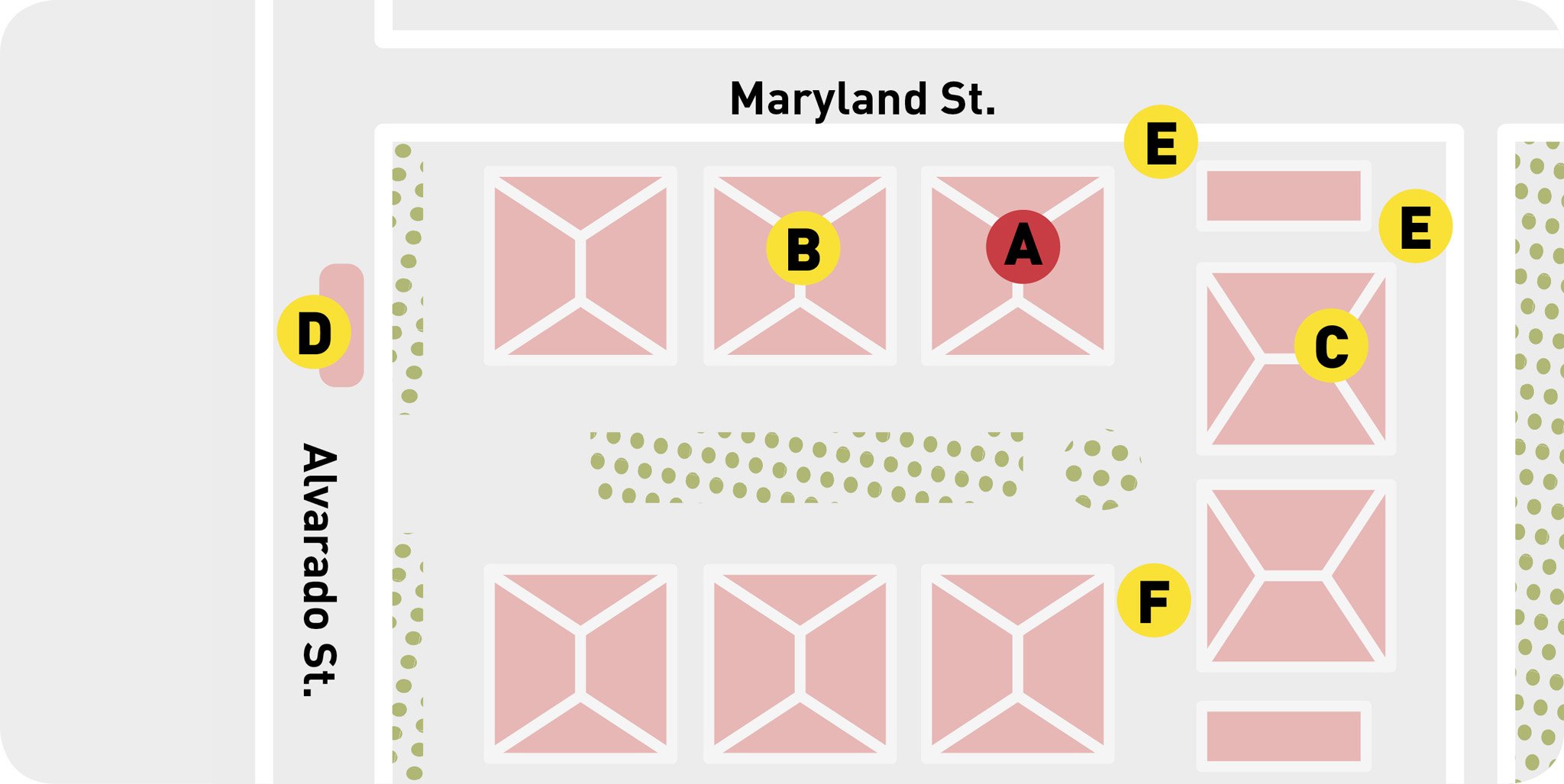

ALVARADO COURT APARTMENTS

404B, W.D. Taylor

404B, W.D. Taylor

402A, Edna Purviance

402A, Edna Purviance

406B, Douglas and Faith Mclean

406B, Douglas and Faith Mclean

Mabel Normand’s car

Mabel Normand’s car

Possible exits for murderer

Possible exits for murderer

Faith Mclean sees man at 8:00 pm

Faith Mclean sees man at 8:00 pm