THE CLEVELAND TORSO MURDERS, 1934–1938

PANIC IN THE CITY

Who was the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run? This serial killer led one of the US’s premier detectives in a gruesome dance, and terrified the citizens of Cleveland for four bloody years.

“Floating down the river, chunk by chunk by chunk;

Arms and legs and torsos, hunk by hunk by hunk!”1

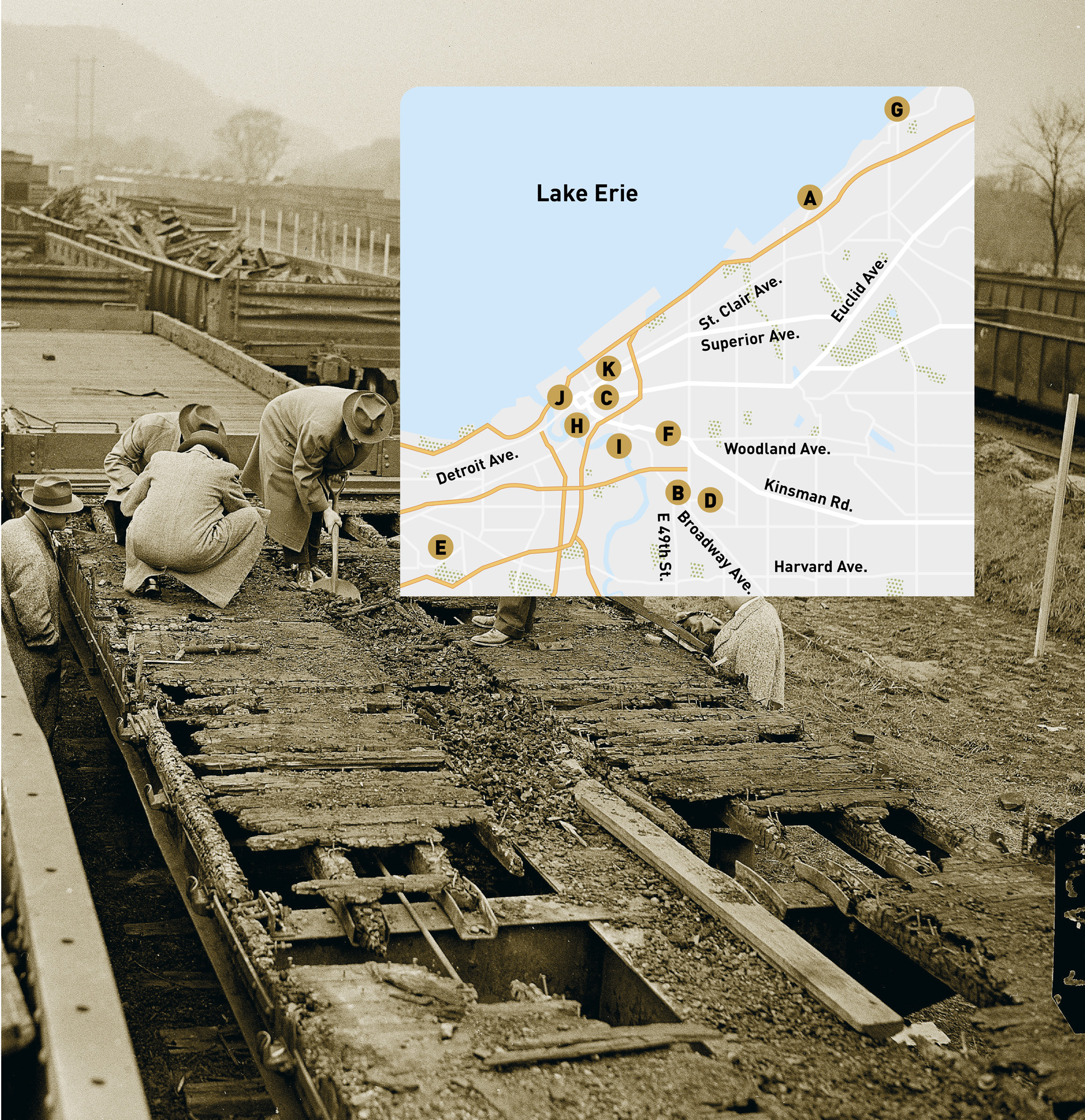

If you’re from Cleveland then there’s a good chance that you have heard this 1930s ditty. The eerie lyrics refer to the Cleveland Torso Murderer. This shadowy individual was exceptionally brutal—decapitating, dismembering, and sexually mutilating his victims, many of whom were still alive when he inflicted these gruesome acts upon them. The Butcher would then litter Kingsbury Run—a shantytown in a creek bed running from East 90th Street and Kinsman Road to the Cuyahoga River—with their discarded limbs, ready to be found by unsuspecting passersby.

This story unfolded on the calm shores of Euclid Beach in Bratenahl, Ohio, on September 5, 1934. Frank Legassle was gathering wood when he made a grisly discovery that he initially mistook for a log. Bobbing along with the flow of the murky water was the decomposed torso of a woman; her head, arms and legs below the knee were missing. The body had been treated with some kind of chemical preservative in an attempt to delay decomposition. Although never officially confirmed, she is generally accepted as the first victim of the Cleveland Torso Murderer. It would not be until the following year that Cleveland police realized that this macabre find was no isolated incident. There was a serial killer in their midst.

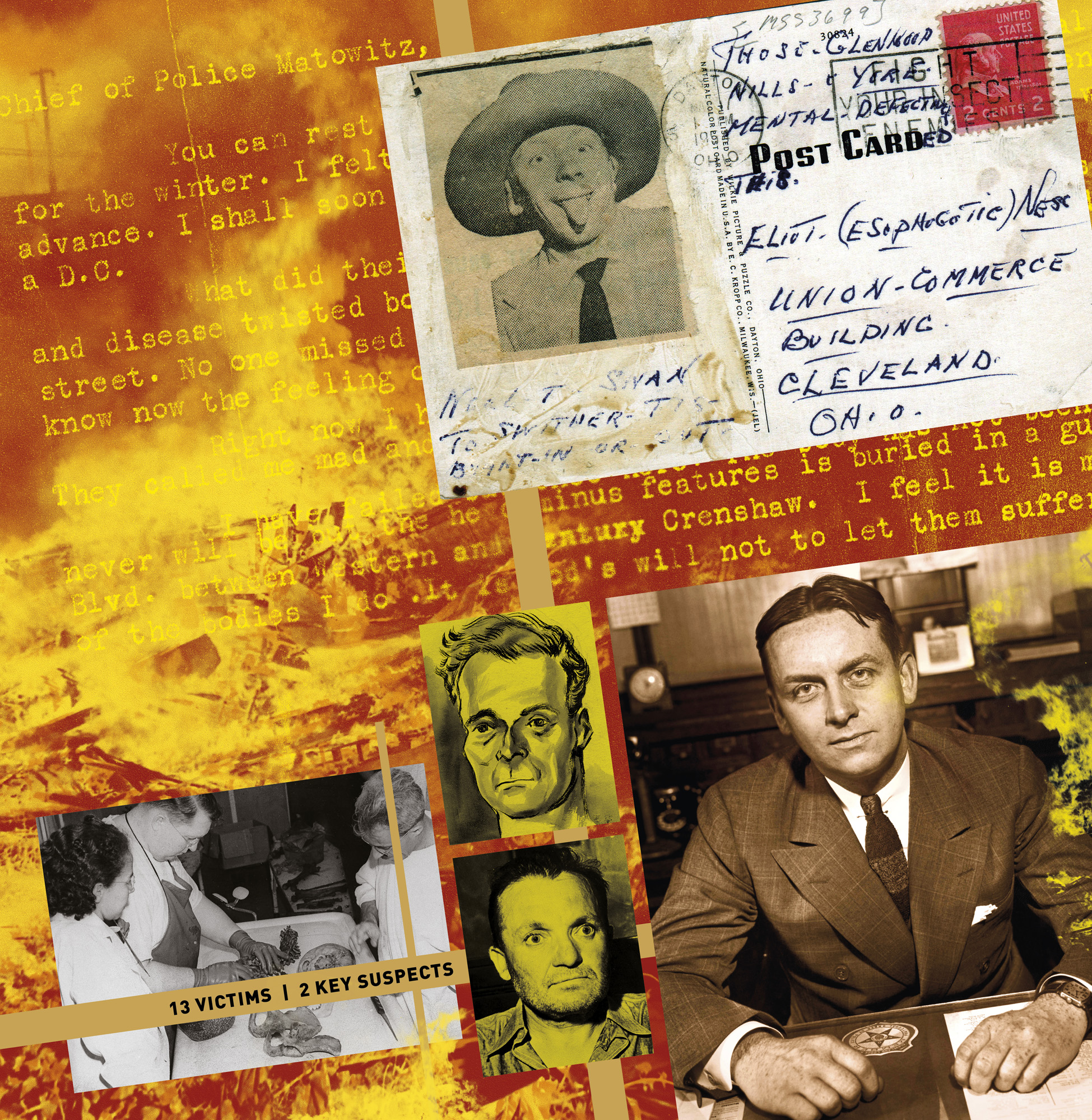

Main image: The burning of Kingsbury Run; letter supposedly from the killer.

Clockwise from top: Postcard sent to Eliot Ness by Dr. Francis Sweeney; Safety Director Eliot Ness; a drawing of a suspect; Frank Dolezal after confessing to the murders; Coroner Samuel Gerber examines bones said to be of the 11th and 12th victims.

TERRIBLE DISCOVERIES

The date was September 23, 1935, and Cleveland was swarming with worshippers gathering for the National Eucharistic Congress. While playing softball in a ravine in Kingsbury Run, just at the foot of Jackass Hill, two boys stumbled across the bodies of two men who had been decapitated and emasculated. One was identified via fingerprints as Edward Andrassy, 28, a petty criminal from Cleveland’s West Side. He had rope burns around his wrists, presumably from being bound by his killer. The other man, who was stocky and middle-aged, was never identified but appeared to have been killed several weeks before Andrassy. Disturbingly, the professional-looking decapitations were not carried out postmortem, but were the cause of death for both men.

1934 / Safety Director Eliot Ness is transferred to Cleveland.

The famed Prohibition agent Eliot Ness was currently Cleveland’s Safety Director, with a remit to clean up the city’s notorious organized crime networks. However, a very different kind of criminal was now in Cleveland and Ness was determined to catch him.

Four months later, a barking dog drew attention to two half-bushel baskets covered with burlap bags discarded behind Hart Manufacturing, just off East 20th Street. Stuffed inside the baskets were the lower half of a female torso, two thighs, a right arm, and a hand. The rest of her remains—apart from her head—were discovered the following week in a vacant lot a couple of blocks away on Orange Avenue. The cause of death was decapitation; her head had been severed between the third and fourth cervical vertebrae with one swift stroke. Fingerprints enabled investigators to identify the body as Florence Polillo, a 42-year-old barmaid and prostitute from the Kingsbury Run area. This was the last of the Butcher’s 13 victims that investigators would successfully identify.

Victim number five was discovered in June 1936. This time, two boys were skipping school when they happened upon a pair of pants rolled into a ball lying near train tracks in Kingsbury Run. Hoping to find money in the pockets, they prodded the object with a fishing rod.2

“WE TOOK A FISHING POLE AND POKED THE BUNDLE AND OUT POPS A HEAD.”

Investigators found a nude male body around 300 yards (274 meters) away, in front of the Nickel Plate Road police building. Much like his male predecessors, the victim had been emasculated and decapitated. Investigators anticipated that this victim would be easy to identify owing to the fact that he had a number of tattoos, including a dove on his arm with the names “Helen-Paul” inscribed above it. However, despite these distinctive markings and a death mask being placed on display at the subsequent Great Lakes Exposition, his identity was never discovered.

THE KILLINGS CONTINUE

A pattern was beginning to emerge: decapitation, dismemberment, and sexual mutilation, all skillfully performed. As investigators sought the brutal killer, the bodies continued to pile up. In mid-July, another victim was found in a valley similar to Kingsbury Run on the west side of the city. He had been decapitated and emasculated; the head was found 10 feet (3 meters) away alongside a bundle of bloody clothing. The substantial amount of blood on the ground indicated that, unlike previous victims, this man had been killed on the spot. In September, remains of a seventh victim were discovered in a stagnant creek in Kingsbury Run. Near his body was a bloodstained shirt wrapped in a newspaper. The creek was dragged by divers until the lower halves of his legs were found. He, too, had been emasculated; his head was never recovered.

GRUESOME DISCOVERIES

The year 1937 brought a spate of new bodies. On February 23, the upper part of a young woman’s torso was found on Lake Erie’s rocky eastern shore. Unlike those before her, she had been decapitated postmortem. The lower half of her torso washed ashore three months later. Bones and a skull were all that remained of victim number nine, who was found on June 6. They were unearthed beneath the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge, less than a mile from Kingsbury Run. Analysis of the bones revealed that they were those of an African-American woman who had been dead about a year. As the news spread throughout the city, a man claimed that the remains were those of his mother, Rose Wallace, who had disappeared 10 months earlier. However, this was never officially confirmed.

Investigators did not have to wait long for yet another body to appear. On July 6, the lower half of a man’s torso was found floating in the Cuyahoga River. A burlap sack containing his upper torso was retrieved later. This victim had been sliced open, gutted, and had his heart ripped out.

There was a respite until April of the following year, when a young laborer saw something floating near a sewer outlet flowing into the Cuyahoga River. At first glance, he thought it was a dead fish, but on closer inspection, he realized it was the lower half of a woman’s leg. In the coming weeks, a lung, a knot of intestines, and a thigh would be found in the river, along with two burlap sacks, one of which contained two halves of a torso. Frustratingly, the second sack—which may have contained the head—sank without a trace.

NESS TAKES ACTION

Despite Eliot Ness and the Cleveland police’s best efforts, they came no closer to catching the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run. They followed a profusion of leads, but every tip and search proved fruitless.

August 16, 1938 / The bodies of the final two victims—a man and a woman—are discovered.

The final two victims were found on a landfill at East 9th and Lakeside. A female torso was wrapped in a man’s blazer and then wrapped again in an old quilt. A nearby box containing the legs, arms, and head was wrapped in brown butcher paper. As investigators trudged among the garbage, they came across the remains of a male body in a more advanced state of decomposition than the woman found nearby. His head was found in a can. The landfill was in full view of Eliot Ness’ office window, almost as if the killer was taunting the director.

Two days later, Ness raided the shantytown of Kingsbury Run, demanding that it be set alight and burned to the ground. Many residents left homeless were rounded up and arrested, as Ness presumed that the killer lived a transient lifestyle like his victims—without any evidence to back up this theory. According to him, the arrests were for the peoples’ own protection, and also to collect fingerprints, making potential future victims easier to identify. At a time when unemployment and homelessness were rife, Ness was highly criticized for these extreme tactics. Nevertheless, following the destruction of Kingsbury Run, the killings finally stopped.

WHO IS THE BUTCHER?

The Cleveland Torso Murderer’s skill with a knife led to speculation that he must have extensive knowledge of human anatomy. Coroner Dr. Samuel Gerber posited that the killer could be “a doctor, medical student, male nurse, an orderly, a butcher, hunter, or veterinary surgeon.”3 An article in the Cleveland News in 1936 described the killer as someone who “kills for the thrill of killing. He kills to satisfy a bestial, sadistic lust for blood. He kills to prove himself strong. He kills to feed his sex-perverted brain, the sight of a beheaded human. He must kill for decapitation is his drug, to be taken in closer-spaced doses.” Investigators trawled through the city in search of the killer’s “workshop.”

“YES, HE WILL KILL AGAIN. HE IS OF COURSE INSANE.”

Despite the large number of people interviewed in connection with the case, the investigation came up with just one main suspect. In August 1939 the police arrested Frank Dolezal, a 52-year-old Slavic immigrant bricklayer who frequented the same downtown bar as the victims Polillo and Andrassy. A thorough search of his apartment turned up stains that investigators claimed were human blood, findings that seemed to clinch the case. Dolezal was questioned unrelentingly for two days, at the end of which he supposedly confessed to the murders.

However, other than circumstantial evidence, there was little to tie Dolezal to the slayings, and it did not take long for the case against him to start unraveling. There were also several discrepancies in Dolezal’s so-called confession; he offered to direct investigators to the missing body parts, but led them on a fruitless search; in addition, the supposedly incriminating bloodstains found in his bathroom turned out to be from an animal. Dolezal then recanted his confession, claiming that the police had beaten it out of him. Before being brought to trial, the unfortunate Dolezal was found hanging dead in his cell.

The ensuing autopsy revealed bruises and six broken ribs, all of which were inflicted while in the custody of Sheriff Martin O’Donnell. Today, it is generally believed that Frank Dolezal was innocent of the Cleveland Torso Murders.

THE SECRET SUSPECT

In 1938, Eliot Ness had another suspect who was never publicly identified. During Ness’ grueling interrogation, this suspect was locked in a hotel room for two weeks—a clear violation of civil liberties. In his book In the Wake of the Butcher, James Badal named this “secret suspect” as Dr. Francis Sweeney, a Cleveland physician and veteran of World War I. During his time in the army, Sweeney served as part of a medical unit that conducted work—including amputations—on the battlefield.

In 1934, a vagrant named Emil Fronek told police that he had escaped from a doctor who he believed to be the Cleveland killer. He recounted that a man “who looked like a doctor” offered him a meal at his home. He agreed and followed the man to a house in Kingsbury Run. Once inside, the doctor brought out “the finest handout I was ever offered.” However, after scarfing down the meal, Fronek became nauseated and fearful. When the man went into the kitchen—allegedly to get a whiskey—Fronek staggered outside and hid. He relayed his story to another vagrant, who also said that he “almost got cut up in that house, too.” Unfortunately, Fronek was later unable to identify the house in Kingsbury Run where these events supposedly took place.

DRUNK AND ABUSIVE

Francis Sweeney had lived a turbulent life; he was in and out of the probate court system and was an alcoholic. In fact, it was said that when Sweeney was apprehended by Ness, it took him two days to sober up enough to be able to cooperate. In 1934, Sweeney’s wife divorced him on the grounds that he had become increasingly abusive and violent toward both her and their children. She said that he would disappear for days and hallucinate while under the influence of alcohol, causing her to fear for her safety and her husband’s sanity. Nine days after the final victim was discovered, Sweeney committed himself to the Soldiers and Sailors Home in Sandusky, Ohio, where he was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia. In the mid-1950s, Eliot Ness received several taunting postcards, supposedly from Sweeney. In 2003, there was an attempt to retrieve DNA from the postage stamps on the letters, which were in possession of the Western Reserve Historical Society. Unfortunately, it was decided that this would cause too much irreparable damage to the items, and the DNA test was never carried out.

In 1939, Cleveland police had also received a letter which was reportedly from the Cleveland Torso Murderer. It read:

Chief of Police Matowitz:

You can rest easy now, as I have come to sunny California for the winter. I felt bad operating on those people, but science must advance. I shall astound the medical profession, a man with only a D.C.

What did their lives mean in comparison to hundreds of sick and disease-twisted bodies? Just laboratory guinea pigs found on any public street. No one missed them when I failed. My last case was successful. I now know the feeling of Pasteur, Thoreau and other pioneers.

Right now I have a volunteer who will absolutely prove my theory. They call me mad and a butcher, but the truth will out.

I have failed but once here. The body has not been found and never will be, but the head, minus the features, is buried on Century Boulevard, between Western and Crenshaw. I feel it is my duty to dispose of the bodies as I do. It is God’s will not to let them suffer.

X

LEGEND OF A KILLER

The Cleveland Torso Murders caused widespread panic among the city’s rapidly growing population. Despite the frantic search for the killer, his identity remains a mystery—as does the identity of most of his unfortunate victims. The Torso Murders is still the most gruesome and notorious crime spree in the city’s history. Today, Haunted Cleveland Ghost Tours even offer a “Torso Murder Tour,” in which they tour the landmark sites of the murders and retrace the steps of the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.

LIST OF VICTIMS

September 5, 1934: Victim 1 (unknown woman, Lady of the Lake)

September 5, 1934: Victim 1 (unknown woman, Lady of the Lake)

September 23, 1935: Victim 2 (Edward Andrassy), victim 3 (unknown man)

September 23, 1935: Victim 2 (Edward Andrassy), victim 3 (unknown man)

January 26, 1936: Victim 4 (Florence Polillo)

January 26, 1936: Victim 4 (Florence Polillo)

June 5, 1936: Victim 5 (unknown man)

June 5, 1936: Victim 5 (unknown man)

July 22, 1936: Victim 6 (unknown man)

July 22, 1936: Victim 6 (unknown man)

September 10, 1936: Victim 7 (unknown man)

September 10, 1936: Victim 7 (unknown man)

February 23, 1937: Victim 8 (unknown woman)

February 23, 1937: Victim 8 (unknown woman)

June 6, 1937: Victim 9 (possibly Rose Wallace)

June 6, 1937: Victim 9 (possibly Rose Wallace)

July 6, 1937: Victim 10 (unknown man)

July 6, 1937: Victim 10 (unknown man)

April 8, 1938: Victim 11 (unknown woman)

April 8, 1938: Victim 11 (unknown woman)

August 16, 1938: Victim 12 (unknown woman), victim 13 (unknown man)

August 16, 1938: Victim 12 (unknown woman), victim 13 (unknown man)

Weapons used by the killer.