Chapter 9

Surviving CSS by Thriving With Sass

How CSS Is Used for Responsive Design

Three core programming languages drive the client-facing experience for all the websites found on the Internet: HTML, JavaScript, and CSS. You might not realize that every time you fire up an editor and write a few lines in any of those, you’re programming. It’s true. Modern, hands-on designers and artists are programming more than ever, and forward-thinking programmers are considering design and composition. CSS is a core technology of the modern web experience that we literally can’t live without. Sometimes I think I can’t possibly live another day with it.

CSS is truly incredible because it was created with the intention of serving two audiences—artists and engineers—and apparently it aggravates everyone. Artists and designers using CSS think it looks too much like code. Coders reading CSS think it looks like a twisted pile of spaghetti. CSS is so important that many smart people are interested in thinking about changing it. Projects have sprung up on the Internet and communities have formed up around them, actively using replacement tech and supporting its growth. How can such a thing happen if CSS is crucial? Why replace it?

“Replacing” might be a strong way to put it. Perhaps enabling CSS’s improvement, encouraging it to be the best it can be, and accepting its flaws with helpful advice are what the community is doing. In fact, it shows just how easy it is to make website development easier with new tools. When the open-source community pulls together and deliberates on new conventions, it’s a win in my mind.

Three of the most noteworthy CSS preprocessors are LESS, Stylus, and Sass. I’m going to talk about Sass.

Sass is a daily-use item in my development toolbox. It improves the CSS language by embracing and extending it with opinions on how to make consistent structural choices across your pages by:

- Creating drop-in modules instead of one-offs

- Declaring colors and sizes once instead of hard-coding them everywhere

- Organizing your work so that it reads clearly as it scales up over time

Why do people think improving CSS is important? Why isn’t it good enough for us now? Years ago, HTML and CSS were invented for marking up documents for research scientists sharing their results. At the time, it was revolutionary, but that legacy leaves us with limited ability. Why? It’s limiting because we’re creative dreamers and relentless builders. Modern websites are mini programs with animations, workflows, dynamic response, and customer choice. It’s an interactive experience instead of static presentation. Interactions rarely happen on traditional desktops but instead on unpredictably sized laptops, tablets, and phones.

Building complex modern websites like these demands power tools to get them up and running by creating conventions that are maintained over time. Maintenance is important because websites built with focused planning become valuable investments for companies. Updating them with new content, additional pages, and even wholesale refreshing are important options for companies. Consider that a website can live for years touched by the hands and brains of different workers possessing varied levels of skill. The CSS programming language needs help, and the teams writing it deserve support.

As website makers, we talk about CSS all the time. What does “cascading style sheet” really mean? “Style” seems plain enough and “sheets” aren’t that confusing, but what’s the deal with “cascading”? When multiple styles are applied to an element, the browser figures out how they flow together and finally applies the correct attributes based on their sequence. It’s like orchestrating a mass of people to form an orderly line so that they don’t fight as they try to pile onto the same place all at once. General styles are overridden by more specific styles. Multiple styles can apply different values to the same attribute of an element, and the browser must apply them in order.

How Sass Can be Used for Responsive Development

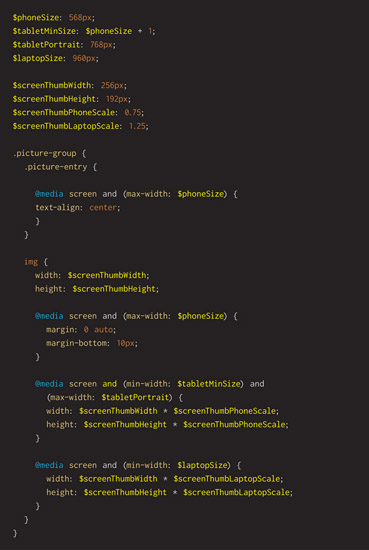

Let’s jump right in and have a look at some typical Sass code. Observe how it looks like CSS combined with some of the variables and math that you might recognize from a programming language such as JavaScript. Web browsers can’t read this file, but instead, the Sass tool reads this and writes out plain old CSS. Software engineers call this type of tool a preprocessor. A tool reads in Sass files and outputs CSS. We might refer to Sass as a metalanguage because it embraces CSS while extending it into far-reaching paths.

Sass starts building on what you know about CSS, slightly shifting your expectations in a dozen different ways. Putting together their amazing combinations empowers you to craft websites better than ever before. Diving into Sass can start simply for you because it’s compatible with CSS. Looking into Sass, you can pull that one thing that makes you curious and solves a distinct problem you encounter daily. Use that thing often, and as your skill increases, your confidence will increase as well. Then reach for the next feature and bring it into your creative workflow as a turbo boost. This chapter is dedicated to introducing artists and designers to some of the most practical parts of Sass.

Creative leaders may want to tag a curious individual on your team to go off and experiment with Sass for a few days or for a few hours a day for a week. Let them explore how many aspects of it will help your team and come back with a brief show-and-tell over lunch. Let it be informal, but purposefully dedicate time to it with all your people present and receptive toward learning from the sharing. See if the lesson helps your team move forward with increased capacity. Use this chapter to guide your forward-thinking adventurer while learning about this intriguing technology.

CSS is Difficult to Write and Maintain

CSS is a programming language. Writing it is super simple—you do it all day long. Writing good CSS is crazy hard. If you’ve ever tried to make big sweeping changes across an existing CSS codebase, you know how tricky and unmanageable bad CSS can be. Our goal is to write clean-looking CSS that’s easy to read and update. This is a challenge. Not impossible, but surely complicated, because as a programming language, CSS offers no formal opinions on organization—at least not to the extent I expect to see given my career as a software engineer.

Because I’ve been programming for a little more than 30 years now, more than some of my teammates have been alive, I have expectations from the languages I choose to use for solving interesting problems. Exactly what qualities have I come to expect from a programming language? Here are some of the high-level qualities missing from CSS that I’ve come to expect:

- Hierarchy— things relate to other things, and it’s good to declare that with left-aligned whitespace, for example, showing dependent “children” inside owning “parents”

- Encapsulation— don’t let code logic and data settings escape from a thing by leaking out into the global space occupied by other things that are completely unrelated and don’t care

- Composition— make up new things by building them up from working parts and reliable pieces pulled from other successfully constructed things

I’ve found that when programming languages have these ideals built into their syntax and way of thinking, it makes my job easier and raises my chance of success. Can a team of A players do a perfectly fine job crafting a portion of their project using plain CSS even though it lacks those features? I must answer yes because I’m a tireless optimist and have seen the power of creative and skilled people overcome barriers in the face of constraint. I’ve seen it happen on many occasions in my career, and joining up with teams of these high-quality individuals is my great joy.

What if that team of highly skilled, engaged, and dedicated individuals is tired and stressed out from trying to meet aggressive deadlines? What if that teams in fact has a number of rookie members learning how to build and deliver? In that case, CSS’s lack of core features for building software in a professional manner hurts. It’s all right, because there’s good news: Sass exists to help us overcome CSS’s weaknesses.

My Favorite Things About Sass

Let me lead you on a tour around my favorite parts of Sass. You’ll find your own over time. Allow me to highlight several things for you to learn about in this chapter. These are some of the crystal-clear moments that I expect will help your education with Sass.

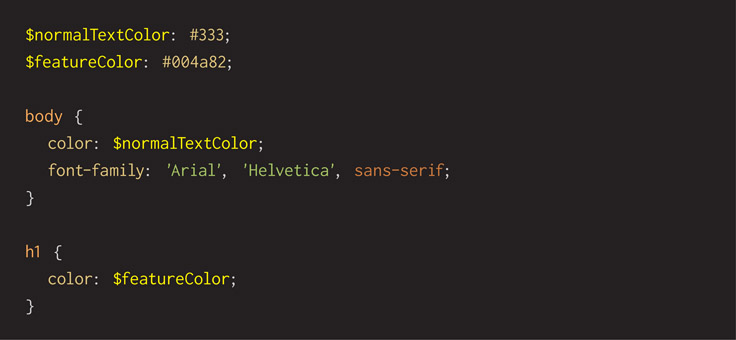

Variables

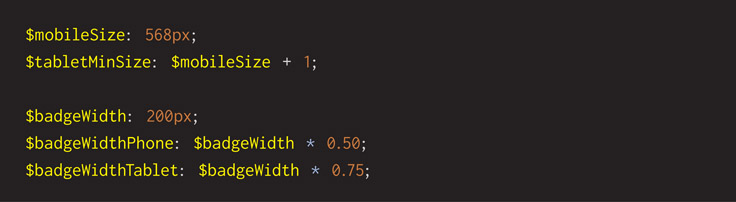

Engineers use variables to hold a value like a number, color, word, or sentence. Naming things is often difficult, but assigning a number or string of letters to descriptive variables tells the reader what the number or color or string does or why it exists. CSS forces us to type font sizes and colors over and over again in our style definitions. Variables start with the $ character followed by letters or numbers that make up the name.

What if you use a particular color a dozen times and it changes due to a branding update? It’s a chore seeking and finding all of the places the old value is used to update it. Tedious work certainly brings with it the potential for creating bugs due to human error in completing the mundane task. Putting colors, sizes, and strings in variables helps isolate the values to a single, well-known place. Updates, maintenance, and routine polish ought to be easier in the future or as initial launch development races along. Here’s an example of this concept.

Importing/Partials

Breaking big problems into smaller ones often leads to success more quickly. Think of how you probably have many .html and .js files in your website. Sass lets you break down a single .CSS into many .SCSS files. Engineers strive to organize their source code in this way, referring to a concept known as single responsibility principle. That concept suggests one file (module or library) does one thing very well. Sass calls a .SCSS file that handles a particular part of your overall style rules a partial. Start a .SCSS filename with an underscore, and Sass will treat it only as a file another one depends upon and imports. Sass files that don’t start with an underscore could be compiled into their own .CSS, and that might be wrong for your needs.

Sass extends the CSS @import command, allowing you to bring in any number of files, or partials, into a main .SCSS file. Ideally you’ll plan these well, allowing you to build them once and use them throughout your company on many websites. The concept of reuse is a powerful one, as your hard work on one project turbo boosts others. Here’s an example of how a main file might look:

While reading this code snippet, please realize that the Sass tool will look for and find files named like this: _reset.scss and _grid.scss that match what is written above. When your Sass is processed, consisting of a collection of one or more .SCSS files, it creates a .CSS file containing all the style rules made ready for a web browser to read and render. The Sass tool has an output style parameter that tells it how to format the CSS. Using the compressed style saves as much space as possible, making it nearly impossible for a human to read but making it as efficient as possible for quickly transmitting from your web server to your customer. Efficient file transfer is important because most people have a data plan with their cell services, and conserving their data budget whenever feasible is the best choice. Not to mention quick load time means more satisfied customers.

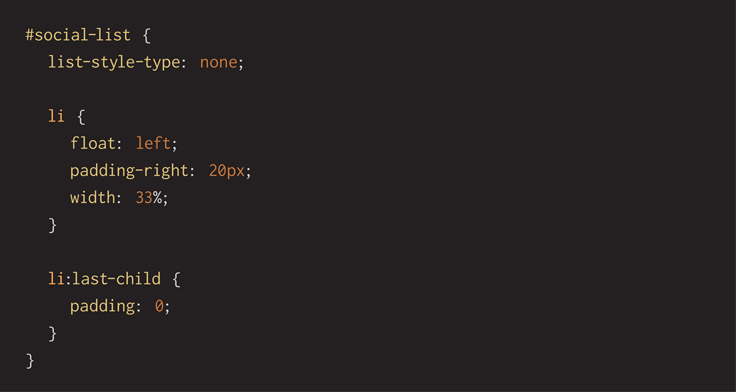

Nesting/Hierarchy

Engineers like hierarchy. Entire ideas such as object-oriented programming are based around the concept of hierarchy. In design, composition is how visual relationships are shown. Sass offers nesting as a way of writing code with hierarchy and showing relation. Tucking away styles inside other ones with indenting lets us more easily communicate those tricky relationships to other human beings. Others could be teammates or our future selves who have long forgotten code we wrote.

One of the aspirations is ensuring this code looks as rational as possible. Our goal should be writing source code that provides the entire context and meaning a skilled reader needs to understand what the author intended.

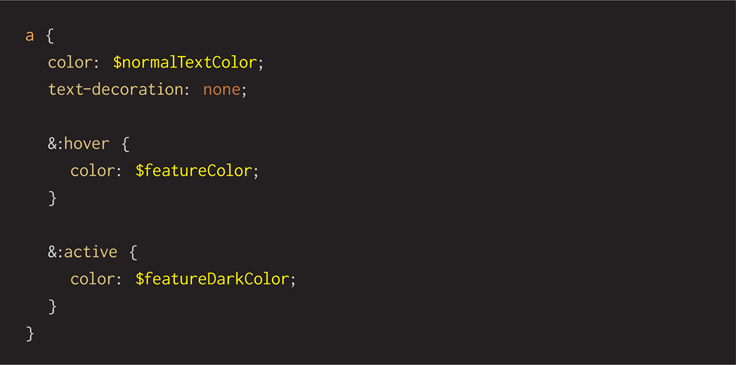

Here’s another example with special notation. Notice the ampersand (&) symbol starting the :hover and :active rules. The ampersand is simply a reference to the parent selector. Using it keeps the Sass code clean and concise looking.

Math

As an author of CSS, you know lots of numbers are floating around your code. Sizes could be in pixels, offsets in percentages, and colors in hex. Numbers are made for math, and Sass helps you perform math in your CSS. Add, subtract, divide, and multiply are available.

Why would you want to do math in the middle of styles? Think about design being about composition and visual relationships between elements. One rule could have a property 25% bigger than another, or starting height with extra pixels added.

Another simple case is bumping over a group of elements by a few pixels. During a polish pass, you could quickly adjust the right or left attributes by typing +6, then +23, and then +38, working elements around the page while refreshing your browser and watching the results. Once satisfied with your fine-tuning, add up the numbers and keep the final ones.

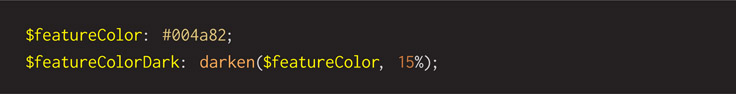

Functions

Sass offers a collection of functions for processing numbers. Functions are more complex than the common math operations because they cover a range of needs but ought to be relatable because they’re practical. Ultimately, they solve design problems and that makes them concrete and real. For example, use a Sass-provided function called darken to tweak a base color for a bottom-edge shadow:

Look through the Sass documentation for more on using this function. Review all the others they have. Many more exist for tweaking colors, changing text, processing numbers, and operating on sets of data.

Again, start with a few things that make sense to you because they solve a problem you have. Use a few until you gain complete confidence. Then reach for a few more and incorporate them into your workflow. Keep the things that work and replace those that don’t.

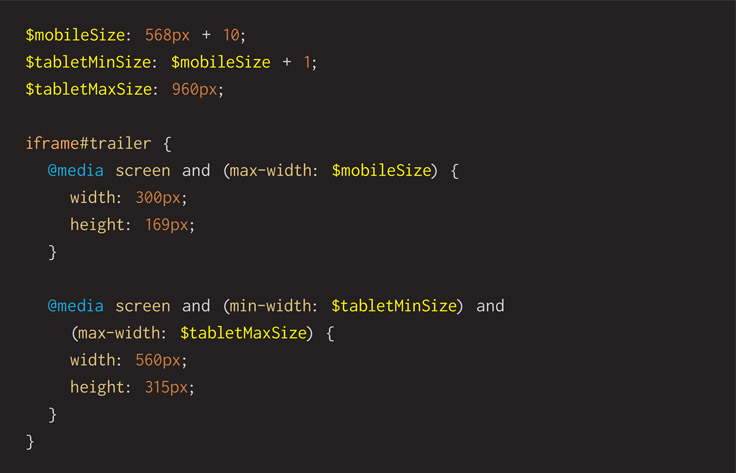

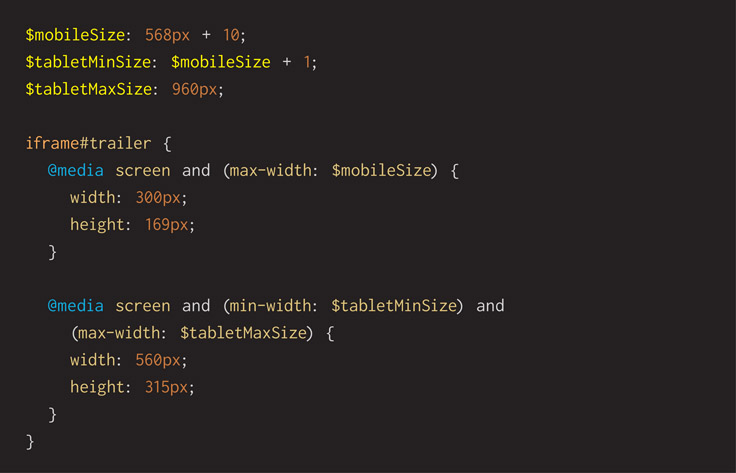

Media Queries

Responsive web development demands use of media queries for influencing how HTML tags are rendered by their applied styles. Sass helps organize media queries by tucking them underneath their tags and classes. This makes code look more beautiful because it’s organized and rational looking. The left-hand spacing that pushes rules to the right lets you clearly see relationships. Mindful organization from the start of a project always makes jobs go better and sets everyone up for success into future maintenance. You’ll notice this is another example of nesting that the Sass tool provides.

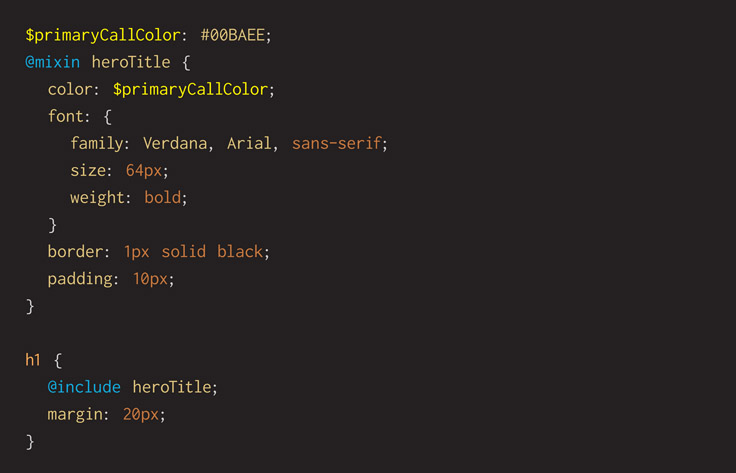

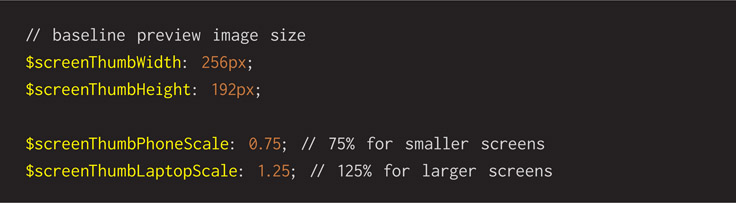

Here’s an example of a style rule written in Sass that shows two media query rules for a tag with a specific identity. The first shows it at a smaller size for a phone. The second gives it a larger size for tablets. Notice how the code is self-documenting, with the use of variables instead of hard-coded numbers. As opposed to using a pixel number in the media query, it assigns the number to a well-named variable. The clear variable name describes what it is and shows why it’s used.

Mixins

Inventing software tools is fantastic because they’re infinitely available. No need to reinvent the wheel, as the cliché goes. CSS offers very little support for building tools, and it seems as though cut and paste is the single way to work faster. Engineers have learned the problems with cut and paste. The worst is when changes are needed. How does a teammate update a block of code when it appears six times? By searching for it and changing each one, and if one is missed, it produces a bug. This tactic is error prone because humans get bored with this type of chore. What if you’re not entirely sure how many times a block of code was duplicated and across how many files? That’s an error-prone situation as well. What if a copied block was changed a little bit, making it look different enough to make a teammate doubt whether they ought to make a change?

Sass has the perfect way to reuse a snippet of CSS source code. Once you’ve crafted your code, wrap it up into a mixin. Use it over and over again throughout your .SCSS files. Mixins are referenced wherever you want the associated CSS to expand into place. Some good examples for writing a mixin include:

- Vendor prefixes for an emerging CSS standard such as CSS3 rounded borders or upcoming animation support

- Visual design from a style guide

- Often-used hacks such as a clearfix routine

Defining and using a mixin looks like this:

Although the mixin uses a few hard-coded numbers rather than well-named variables for the padding and font size, the fact that they’re contained within the mixin helps hide them away from spilling out into the file. Anytime that mixin is changed, simply running the Sass tool on your .SCSS files guarantees updates are distributed throughout your project wherever the mixin is included. No need to guess where they are. That might not seem important as a project begins because it’s fresh in your mind and you can flip to references quickly. As time goes on, however, a team’s collective memory becomes fuzzy, and letting Sass help is an advantage. No need to search and replace throughout a collection of code files, since a quick run of the tool rebuilds your .CSS file.

Compression

As an engineer, I talk and debate about compression at least once a week. I believe everything can be made smaller. Smaller is nearly always better when it comes to modern electronics and nearly always better when applied to resources sent from your web server to your customer’s device. Images can be compressed, JavaScript can be compressed, and so too can .CSS files. Sass has you covered in this category because the .SCSS files can be written out to a final combined file written as small as possible. It does that by throwing away as much white space as possible. Humans benefit from spaces and line breaks when reading, but web browsers simply don’t care and read it without hesitation.

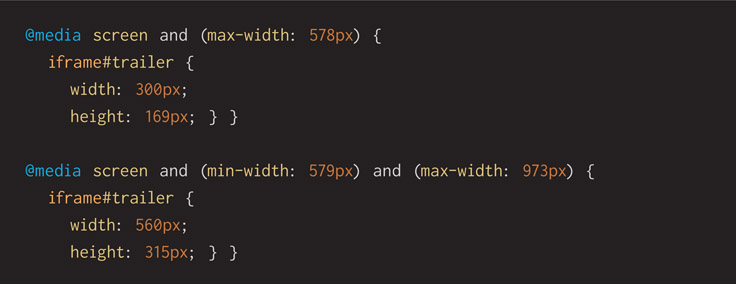

Sass writes out your combined .CSS file in what it calls the output style. Without telling it anything special, it writes a file with whitespace and line breaks making it human readable, and the largest possible. For example, given this typical media query snippet, which is easily read by any human teammate and is uncompressed, weighing in at 320 bytes in size:

Compiling it to a default .CSS file, you’ll see written out code that’s 226 bytes long and looks like this:

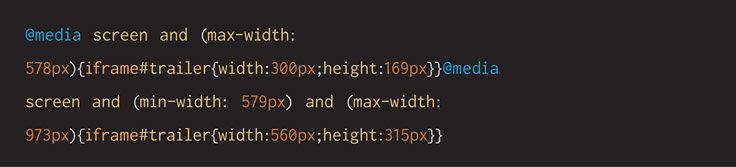

The same code written out with compressed style produces a .CSS file only 185 bytes long that looks like this:

The difference in file compression is almost a 20% saving, and believe me, it adds up over time. Your project’s SCSS source code and final CSS are going to be much larger than this elementary example. The more readers that visit your site, the more bandwidth cost you save on sending files to them. It’s a win all around, and Sass builds this in from the start.

Modern Comments

I believe that commenting code can be a weakness. Many people say it is a strength because an author is conveying meaning to future readers. But comments are just another way human beings create bugs. An author tells why they’re doing something because the code tells what is being done. Later maintainers end up inserting code, shifting lines up and down, and retrofitting new features. If they didn’t maintain the comments as well, then they’re all out of date and obsolete. Worse, they’re outright incorrect or possibly even near the wrong lines of code.

The next time you write code and feel the need to add comments to explain what is going on, take a moment and consider if the code can be rewritten in a way that doesn’t require a comment. Usually the second pass will be better designed.

Modern code writers understand it’s best to write code that’s self-documenting. That said, Sass offers modern comments that look like // rather than /* */. The double-slash syntax for comments is easier to type, less error prone, and looks far less noisy when reading through source code. Here’s an example of modern comments.

Introductory Way of Using Sass

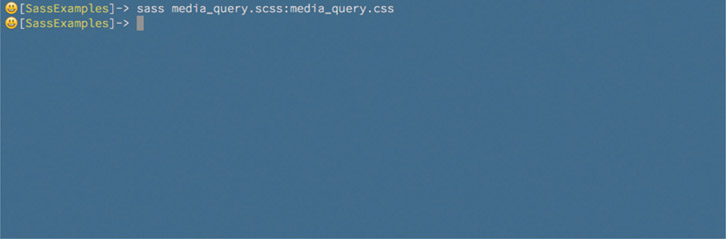

Assuming you have Sass installed on your work computer (more on that in an upcoming section), you’ll have the tool available on the command line. In both OS X and Windows, the tool is called the same and has matching parameters. Here’s the basic way of using it:

That produces a final .CSS that combines all the individual .SCSS files given a human-readable file with whitespace and line breaks. It’s fine for learning, debugging, and previewing on your work computer as you build up your website and web apps.

Intermediate Way of Using Sass

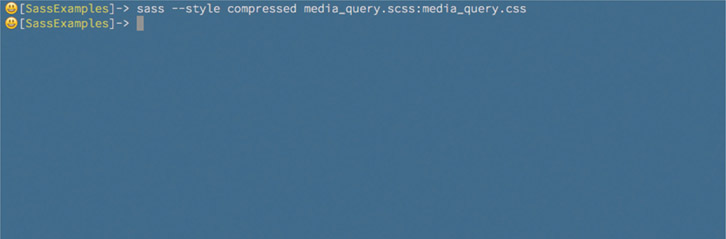

Compressing your final .CSS file by telling Sass to write it with an efficient output style is next. Building upon how we compiled our style sheet in the previous example, see this next example, which uses a command-line parameter:

That produces a final .CSS that combines all the individual .SCSS files given a machine-readable file with all unnecessary whitespace and line breaks removed. It’s the most space-efficient version that you can have ready for final deployment to your customer-facing web server.

Let Sass Help

Sass is a tool built to help you. By layering up a level of syntactic sweetness, it improves the restrictive yet verbose CSS we all started learning years ago. You might discover using the Sass tool is confusing every once in a while. Command-line tools generally receive a negative opinion because they seem to hide their functionality. There are no menus or buttons that obviously reveal their abilities, as a GUI app has. Convention among engineers is making their command-line tools accept the parameter ––help to offer up reminders. When you issue the command sass ––help, you’ll see a block of text reminding you what the Sass tool can do given parameters. Take advantage of this help while learning the tool to start and periodically as you reach for one of its extended capabilities.

Advanced Way of Using Sass

Making changes in your editor and then swapping over to the command-line window running the Sass tool is fine to start, but it becomes time consuming. It’s also error prone because getting in the zone will eventually mean editing and then swapping over to the web browser and wondering why the changes aren’t showing when you tap the refresh key. A computer is the best at mindlessly following your orders exactly as you tell it to. Let’s tell Sass to watch your SCSS files, and when it sees any of them have changed, it will write a fresh copy of the .CSS. It’s easy to use its watch parameter, as seen here:

Automatic tools are great time savers that reduces tedium and the human error that necessarily comes from boredom. Write your Sass code and let the tool figure out when to make a new style sheet.

Sass is a command-line tool. Why do programmers prefer text-based utilities? They seem intimidating and aren’t at all user friendly. True, but designing a graphical front end takes time, and the first pass on a tool is always about building a working feature. Many times, command-line tools are easier to snap into build tools like make, grunt, gulp, and Jenkins that add automatic conversions for convenience. Often tools become popular and gain GUIs from other teams that want to make them more accessible for a wider audience.

Organization—Think in Libraries

Thinking in libraries is always a surefire way of helping your teammates, the community, and future you. It’s true that working in a real-world local library is a quiet sanctuary that enables concentration and brainpower, but in this case, I don’t literally mean think in a library. Libraries are a way programmers package code into useful bundles that others use. Think of a bundle of code as something that you can reach for to benefit from immediately. Instead of making something one off, build it to be used as a drop-in. Software libraries never run out and are always ready to build up a stable foundation that raises up your project or to tap into a tight-fitting space and fill in a missing piece.

Patterns and recipes are other metaphors for quickly describing practical tools that help you build software, but I don’t like either of them in this case. A pattern is a cutout that a person must trace around to replicate a shape on a piece of material then cut out for fabrication. Closer is the idea of a recipe, which is an ordered list of directions that tells a person how to pull together ingredients that are combined for a final dish. Neither describes the power of casually bringing in a library that snaps into place and immediately gives you a complete item ready for operation.

If libraries are best known to engineers as bundles of working code, in JavaScript, C, Ruby, Python, whatever, how does that apply to Sass and CSS? The same idea is directly applicable, because CSS is code after all. Once you’ve built a complete set of styles or even a handful of them, start thinking about how you can save yourself from ever building the same thing again. Invest your time in building new stuff! Don’t spend your future tracing over your old lines. Create libraries of solutions to your problems now and forever.

There’s the evocative idea of the “lazy programmer” that inspires us to think of how spending a little time researching prior art before jumping into coding can save us from pouring unneeded time into working a problem. Avoiding work sounds like a horrible quality in a teammate, but in the spirit of reuse, I’ve found it to be one of the finest attributes of smart colleagues.

Who do we create libraries for?

- For our future selves who are overworked and annoyed they can’t remember that one time they already solved the same problem

- For our teammates who will proudly call us their favorite creative partners as we help them push forward past an all-too-short deadline

- For our company that can move forward with purpose as all its employees share with one another for greater speed

- For the open-source community to pay back or pay forward, keeping the virtuous circle spinning

Ideally, libraries are started by a single mind with a certain purpose and released to a group, with some working examples testing its features. Written documentation is a definite plus. From there, others are invited to use it and participate in its future. Libraries make an abstract idea real, and real things can be enhanced. Goals for enhancing a library include:

- Bug fixes for broken aspects

- Optimizations that make slower things faster

- Additional documentation and tests

- Feature enhancements

- Teams learn it and stay smart

Learning a library is a way teams can acquire skill and propel their abilities forward. It’s a tool, and like any tool, a Sass library will increase your power and ability.

Creative leaders, encourage your teams to build and maintain libraries. They contain hard-fought solutions to old problems that make future projects easier. Work becomes easier by relieving the stress of remembering past solutions under time constrains. Look to libraries as assets worth investing in. This benefits your entire company over time. They’re ways for you to increase delivery capacity as your skilled individual contributors make teams work with intelligence.

Given any particular problem, I could sit down and blast out the code—whatever comes to mind first—and get the job done. As soon as I get something working, I could move on to the next task. Source code written in this way is quickly forgotten because it’s impossible to reuse. If I took a little time to write reusable code, I’d be delivering value to my client, reducing the amount of new code my teammates must write, and even helping out future me.

Steve McConnell write, in his thoughtful book, Code Complete:

“What if I’m just writing code for myself? Why should I make it readable?” Because a week or two from now you’re going to be working on another program and think, “Hey! I already wrote this routine last week. I’ll just drop in my old tested, debugged, code and save some time.” If the code isn’t readable, good luck!

Steve McConnell, Code Complete: A Practical Handbook of Software Construction (Redmond: Microsoft Press, 1993, p. 779)

When writing new code, we should seek out readability over everything else. Code is best when it’s functional, reliable, sensibly organized, self-commenting, and easily understood by any professional reading it.

Installing Sass

You’ll want to install Sass once you’ve read through this chapter and decided that it’s a powerful tool to add to your professional toolbox. Look to the official website for how to install it:

The Sass site describes two ways of installing Sass: (1) using a GUI app and (2) using the command-line tools. The GUI apps are actually calling the Sass command-line tool behind the scenes. Some are free and others are paid, and all come from third parties building atop Sass. Please pursue one of them if that feels more comfortable to you.

The command-line tool is what is officially supported by the community that builds and improves Sass. Because they are building the command-line edition it will have the most up-to-date improvements first, and apps will try following up behind them. I recommend you install and use the command-line version. Many people think the command line is intimidating because it doesn’t casually reveal its capabilities. Look to the Sass documentation on their website, because it reveals all. This chapter has a section showing how to use Sass well enough to propel you through your work.

When you look at their installation website, you’ll see a list of apps you can choose. Some run on one or more of the major operating systems. The command-line edition asks for you to first install the programming language Ruby. If you’re using a Mac, congrats, you already have Ruby because it comes preinstalled in OS X.

If you’ve not heard of it, Ruby is a scripting language that powers many successful web servers. The startup community has found that a small team can provide extensive functionality quickly when Ruby is paired up with a library called Rails. Sass makers choose Ruby as the language they want to use for building their tool. Rails isn’t involved, but other open-source libraries are. Because they choose Ruby, and that language is on many computers, Sass can be run on them and widely adapted.

Please follow the Sass website instructions for installing their tool. I believe they’re clearly written and current. There’s no need for this book to duplicate their fine effort.

Programmers Have (Code) Style

Why does code style matter? Do you need to settle on a convention? Probably not if it’s just you writing Sass by yourself. As soon as you mix in other folks, it has a way of becoming more difficult than we want it to. Modern web development is already complicated enough that figuring out the ways of making it simpler ought to be a goal. A key way engineers have found is agreeing on conventions in code style.

If everyone on the team is writing code that looks the same, at least you have that going for you when everything else is getting tough. When all the Sass code looks the same, at least that feels welcoming and consistent when you drop into a file someone else wrote and intend to edit it. Any project of a significant size on any project running a significant time will have a lot of code. Odds are lots of it won’t have been originally crafted by your hand, but you will eventually touch it.

What goes into a code convention? Mindfully making choices like these:

- Indents as spaces or tabs

- How to name variables camelCase or snake_case or divided-by-dashes

- The order of attributes in a style definition

- Hierarchy of files and how you break down into files (includes)

- Any external libraries that you want to pull into your project

- How much you abbreviate variable names

Use code reviews to enforce and remind one another about convention details. Use this as a way to initiate new teammates. Teach them by having them look at the best code you’ve written and fix the worst of it. By the way, all the code ought to be good enough that you’re proud to show off it.

Code conventions are similar to design guides. Typical of most art departments, guides keep teams on track, build capacity, and retain consistency among employees. You’ll find this even more valuable if you ever need to work with external contractors to help build some of your site. They might have their own style or a complete lack of style, and you’ll want them to conform to yours. Some of it is for looks, but it’s defensive, too. Have high expectations in quality early and throughout your project.

Craft your own code style guide. Encourage everyone to add to it and improve it over time. Keep it alive, and change it in response to what you’ve learned. Start with a community-published guide if you don’t want to write one. Search on you favorite search site, and you’ll find several from which to choose. Pull in the one that strikes you and work from it for a while. Learn what you like and dislike about it and improve it as you work.

Whatever you do, please make a decision as early as possible. You have a choice, and it matters. CSS is one of those things that gets out of control quickly. Sass absorbs some of those troubles, but it can’t protect you from everything. In an organization big enough to have multiple teams, they might all want to have a choice in picking their convention, but caution against that. Creative leaders might want consistency across teams and their assigned projects, just as a team would among its members. This might make it easier for employees to cross boundaries and slide between teams. Then they can help when deadlines get crunchy and have an option when they crave a new creative outlet and desire to transfer inside the company.

Sass makes you choose from one of its styles. Look at their website, and you’ll see code examples are shown using two distinct syntaxes. One is SCSS, and it is the style I’ve chosen to write examples in. It borrows heavily from the basic CSS syntax and looks familiar to anyone writing CSS code. Because of the familiar feel, I suggest that you adopt it.

The second syntax choice is called Sass. It offers minimalism by removing most punctuation for clean-looking code. Indentation beginning each line is important because it describes hierarchy and context. It’s a more radical interpretation of CSS, and if your team selects it, there will be a learning curve.

Debugging Sass in Chrome Developer Tools

Finding glitches and fixing them is a recurring theme in this book. A key ability of debugging your code is seeing your source code executing in a browser. When you get to a problem, you can page through your code and see the state of affairs of your program. Browsers know about HTML, JavaScript, and CSS. CSS is naturally the final output of your Sass, but seeing what the CSS looks like in your browser as you step through code isn’t the best possible way to diagnose logic errors. When you get to a point where you’re writing Sass daily, you’ll want to debug within the context of it.

Google’s Chrome browser has a working solution for this. It connects the dots between the written CSS output and the original Sass you wrote. A technology called “source map” is what you’ll see written when you investigate this topic.

Because this is an advanced lesson, we won’t review details about it in this book. It’s more than I want to get into now, but please research this tool when you’re ready to learn about it. Check out this page for more:

Community Tools

Libraries are bundles of code that are easily used in present and future projects by you and your team. Lots can be made of them, but in the end, they represent solutions for problems you’ve already faced and ought to never have to repeat. Whenever possible, think of building up libraries, because the time invested in crafting them now will make working in the future quicker.

The open-source community has assembled many libraries that you can reach for. Like any tool, they amplify your abilities and empower you to better perform your job. I see the additional tools supplementing Sass in two distinct ways:

- Applications providing graphical user interfaces

- Frameworks of styles and functions

The Sass install page lists a number of applications that you might prefer over the command-line interface. Here are examples of some of the libraries that provide solutions to responsive design, grid layouts, browser-specific vendor prefixes, animations, and other helpers: Compass, Foundation, Bourbon, Neat, Susy, and Bootstrap.

By now you’ve looked for solutions to your project glitches and problems using your web search engine of choice. It’s good to remember this is an alternative when you and your team-mates are stuck trying to solve a problem. There’s a good chance someone else has had a similar glitch, fixed it, and documented the solution. Even better, these folks might have productized the fix by publishing a library and posting it on GitHub. Take advantage of prior art if you can, and participate in it by publishing some yourself.

Alternatives to Sass—A Quick Survey

Sass is the subject of this chapter. I’ve built a case for why you’ll want to use it to improve your CSS workflow. I propose that using plain CSS is not enabling and bluntly prevents you from becoming the awesome master of the web universe that you could become. What if you’re in the tricky situation where you know you don’t want to build a significant website using raw CSS but are unwilling to choose Sass? Are you wondering if there are similar competitive tools that enable you to build better style in your project? Yes, there are a few. Even if you do want to use Sass, you might want to examine these other systems as a competitive review. Determine if there’s an advantage to them and how you can apply their lessons to your own work.

Less is a major competitor to Sass. It’s also used as a command-line tool, and it’s written in JavaScript. Instead of requiring Ruby as Sass does, Less asks you to first install NodeJS so it can run. NodeJS is on all of the major operating systems, and therefore Less is widespread and available to you. Many of the features Sass is well known for appear in Less. Bootstrap is a famous tool, and it uses Less for features such as themes and responsive layout math. The undeniable popularity of Bootstrap may have had a hand in making Less famous in your world. You may also be curious to know that Bootstrap has recently been adapted to use Sass because of its popularity.

NodeJS is mentioned a few times here, and you might have read about it before. It’s a version of JavaScript that runs on the server. It powers websites just as PHP, Java, Ruby, and Python do. NodeJS also allows JavaScript to run on a command-line, letting it become a language for tools. It’s worth learning about because front-end makers can dabble in back-end work and invent time-saving automation tools.

Stylus is another competitor to Sass that’s also built in JavaScript and requires the command-line version of it, NodeJS. This CSS compiler is often paired up with websites built in the NodeJS language. Know that it can be used on its own to generate CSS. Stylus has many of the conveniences found in Sass but diverged in a way by making the language look different. As I read through Stylus code, I think its creators are trying to remove the special characters that make CSS look like a computer language. I believe that their objective in simplifying the language is to inspire more people to take a committed look at it and select it for daily use. Without parentheses, curly braces, colons, and semicolons, some people will say it reads more clearly.

Whatever you do, please consider choosing a tool that offers a time-saving advantage over writing raw CSS. It simply wasn’t created with today’s complicated websites and web apps in mind. You need assistance in first crafting styles and then maintaining them, and one of these tools will improve your workflow.

Surviving CSS by Thriving With Sass

Given all that’s written in this chapter, one might think I dislike CSS to the core of my being. I understand that suspicion, but it’s not entirely true. I respect what CSS is capable of, understand what it does well, and admit that it’s a core technology of the web browsing experience. I simply want a better tool for you, and as an engineer, I know we can definitely do better. In this case, better means embracing CSS but extending it in a rich direction that its authors couldn’t have guessed we’d need in our modern websites. Initially invented for formatting technical papers, CSS is constantly pushed beyond its capability, as websites have evolved from single pages to complex programs.

Dealing with complexity is a constant in software development. I assert that over my career, I’ve seen that previous problems have indeed become easier, but then we somehow make the job more complex by adding higher expectations. We’re adding deeper interactions, richer visual interfaces, and broader support of viewing hardware. Over time, engineers have created ways of thinking about approaches to reduce complication from additional wants. Formal thinking produces mental tools such as:

- Hierarchy for better organization and code that is more easily understood

- Encapsulation to self-contain work into single responsibilities and solutions

- Composition that produces variables, mixins, and libraries for reuse

Don’t assume these techniques are the exclusive domain of engineers. Anyone interested should reach for any one or more of these tools and pull them into their creative workflow. Each is empowering and helps solve a classic programming challenge. They can empower you, too. Given what you’ve learned about Sass, think of how it embodies these approaches and whether they are of concrete benefit to you. Especially reflect on what you’ve already experienced with years of writing in the CSS language. If plain CSS is good enough for you and your team, then please stay with it.

Now, if you’re imagining you need a better alternative, it’s time to mindfully consider a change. Evaluating a tool like Sass will become a material competitive advantage for you either as an individual, as a team, or as a company. Whatever you do, intentionally consider building your CSS with a higher-level language that sits on top and compiles down to it. Excellent alternatives to Sass are listed in this chapter, and you’ll do well choosing any of them. By picking one of them and incorporating it into your development tool chain, you will become more productive, your team can better share its solutions with itself and others, and you may discover more time to polish your web projects.