Chapter 4

Apache Web Server

What Server Does Everyone Use?

When we talk about “production servers,” what does that mean? What do they do, where are they, and why are they important? How do our customers interact with a production server, and how does it help them? Would it be helpful if we had access to one? Better yet, can we get a server on our own computer so we can see how our work looks in the same way the public does?

Yes.

Without a doubt, we need to have a web server running on the same computer we work on daily. All design work turned into HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and images ought to be seen in a testing environment that’s as similar as possible to the production one. Why? Because nothing matters until we confirm our work on customer-facing browsers and the devices they have. Saying “it works on my machine” is super satisfying after a long day of cranking out code, but in the end, it simply doesn’t count. Setting up a web server feels difficult, but is it?

No.

A web server is just another tool to grasp with a strong grip and wield with confidence. Anyone feeling it’s a challenge should rest assured that the following step-by-step processes will successfully guide you through setup. Pushing past a comfort zone is an opportunity to grow. This experience will raise your professional skills to the next level.

Brief Introduction to Apache

The Apache HTTP Server (or simply “Apache”) is the most-installed web server software on the Internet today. Why? In its twenty years, it has earned acceptance in the open-source community. Its free cost, frequent updates, patches, optimizations, and security improvements make it an easy choice for system owners, engineers, and designers.

Where do Servers Live?

When we spin up an Apache web server and copy up our site’s files, where does it live? What does it mean to be “in production”? Production is the fully Internet-connected live environment where our customers view the website. Production servers can be in a few places. Each option has trade-offs and benefits, allowing for true choice.

Servers on Hardware

Hardware means actual physical computers sitting somewhere. More than likely, they are servers you purchased and mounted in racks that are now sitting in a data center. A data center looks like a warehouse filled with bookshelves (racks) filled with pizza boxes (servers). The cool-looking-blinking-light factor is high in data centers.

Racks are bolted to the floors of a professional data center run by a trained technical staff. What the staff does makes a difference both in action and in price.

- “Managed servers” means they take an active role in monitoring your hardware and software. When any issues are detected, they follow steps scripted in a troubleshooting guide. Steps could include minor maintenance, logging status info, or contacting a teammate who is on call for report and hand-off.

- “Unmanaged servers” means the data center staff basically stays well away from your servers. Their basic guarantee is that your servers pull power and push data across the Internet.

Either way, these servers are devices that you could conceivably drive up to and touch.

Servers on Cloud Computing

Servers in the cloud are backed by hardware, but not hardware that you need buy. You rent them. Machines are assigned to you on demand from the fleet of servers owned and managed by the cloud service provider. Each server, in fact, is more likely a slice of a commodity server allocated in a matter of minutes of your request. Generally, servers are based on a handful of “off the shelf” sizes along the lines of small, medium, large, and extra large.

The server is selected from a catalog of standard configurations based on operating system and some supporting utilities. From there, you can upload your website files and any additional tools. If you choose this path, find out if your cloud service provider allows for creating a “snapshot” from one of your fully configured servers. From there, it can be added as a configuration choice listed in your private catalog. Choose the snapshot when you ask for a new server. When it spins up, you’re ready to rock.

Installing Apache Web Server on OS X

The following steps are for installing Apache on Apple’s OS X versions 10.8 (Mountain Lion), 10.9 (Mavericks), and 10.10 (Yosemite).

No Need to Get the Installer

Most installation directions begin with “go download an installer package.” No need in this case. One of the distinct advantages of OS X is that Apache comes preinstalled. It’s one of the many web tools typically used by programmers that it ships with, such as PHP, Python, and Ruby.

How easy is that? No installation needed, but there is a little setup necessary to activate it.

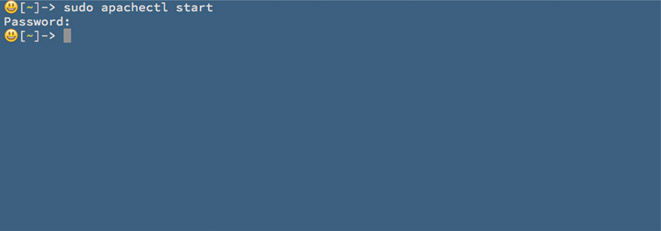

-

Open a Terminal window

-

Type sudo apachectl start and enter

- Enter your password to confirm administrator privilege

sudo is a program for UNIX-like operating systems (like OS X via Terminal) that feels like a programmer tool but simply means “substitute user do.” That’s a rather formal idea, but it’s generally associated with the most privileged user (e.g., root or administrator). This allows us to tweak files placed in or install files in areas normally restricted by the operating system.

Are we Done? Is Apache Working?

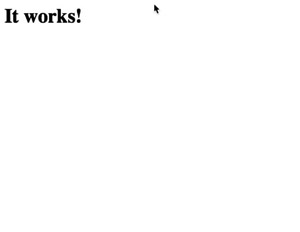

Believe it or not, Apache web server is now running on your work computer. Confirm it’s ready by opening your favorite web browser, for example Safari, and entering http://localhost in the search bar.

You’ll immediately see a simple, confident message: “It works!”

You did it! You’ve begun using a tool that’s going to make your professional life easier from this day forward. Enjoy a coffee and celebrate this small victory!

The Internet Protocol address 127.0.0.1 is important because 127 is the last address in the A class of networks and 0.0.1 is the first entry on that network. All requests to 127.0.0.1 are specially interpreted as “loop back to this device,” and Apache can catch them. Your localhost is mapped to this address.

Beginning Way to Use the Apache Server

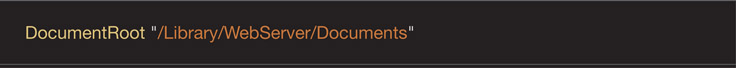

Starting off, Apache has a default folder where all the files making up its website are stored. We can see that via a Finder window.

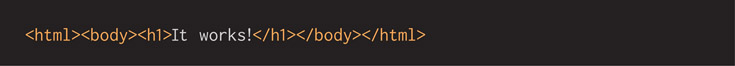

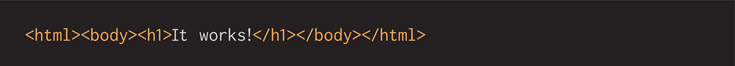

Open up a Finder and navigate over to the folder that we know Apache installed named /Library/WebServer/Documents. Look for the only file it holds called index.html. Edit the file, seeing it’s a single-line document looking like this:

Can we use this same folder to store all of our website work? Will Apache serve our own files to our web browser? Yes! This is the easiest way to get some work done quickly while playing around with your latest development tool.

Congratulations! You own a web server. Shiny! It’s worth having some fun playing around with it. When you’re ready to raise your game to the next level, come back to the next section. It’s worth taking the time to see how you can fine-tune and improve your Apache server to better work for you.

Intermediate Way to Use the Apache Server

Wielding this tool properly means telling Apache where our working folder possessing all of our various website projects is.

- Launch your favorite text editor for OS X (could be TextWrangler or another one listed in a section that follows)

-

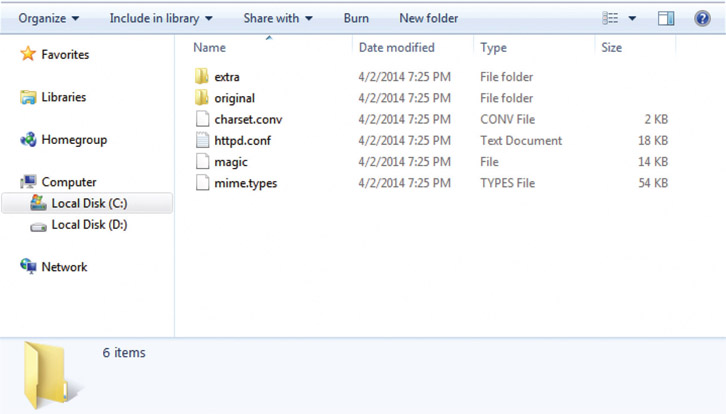

Choose File-> Open and navigate to the folder Apache is installed in by default /etc/apache2

Some of these system files may be hidden from view by default. Pressing the keyboard shortcut combination Command-Shift-Period (.) in any open dialog box pop-up shows hidden files.

- Open the folder inside it called conf

- Open the file called httpd.conf

-

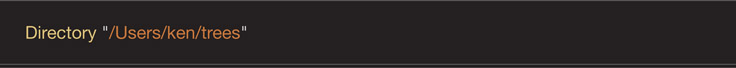

Page down and look for the first line we change. It looks like this one, which was line #236 for me:

-

Replace the text inside the quotes with a full folder path to your work folder as I have here for mine:

- When you begin typing, a dialog box might pop up, asking you, “Are you sure you want to unlock ‘httpd.conf’?” because it’s a special file. Press the Unlock button as confirmation that you know what’s happening.

-

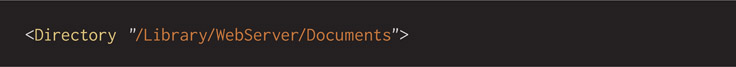

Page down and look for the second line we must change, which looks like this one, which was line #237 for me:

-

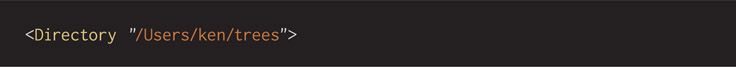

Replace the text inside the quotes with a full folder path to your work folder as I have here for mine:

-

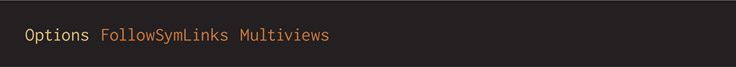

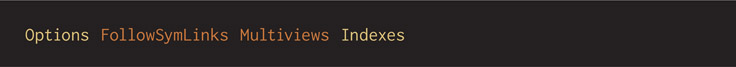

A few lines down is a third one that you must edit from the original install. Find one that looks like this, which was line #250 for me:

-

Add the Indexes option at the end of the line allowing you to browse directories making it easier to find your work.

- Save the file and quit your text editor, because you’re done with the changes. A dialog box might pop up asking you, “… wants to make changes. Type your password to allow this.” Do so, and click the Allow button to give permission.

- That was simple, right? There are lots of hardcore-looking settings in that configuration file that quickly get technical. No need to touch them for now—or ever, unless you want to specifically learn more about them one day.

-

Restart the Apache web server by opening a Terminal window. Type sudo apachectl restart, which restarts the Apache server. Give it a minute to turn itself off and back on again. Let it forget about the old settings and read in the new ones you’ve just changed in httpd.conf.

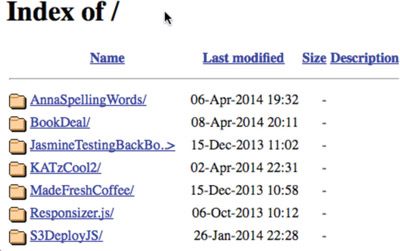

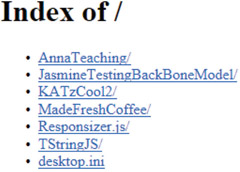

- Open your web browser and navigate to http://localhost once again. What ought to be different is you’re seeing a list of folders in your working folder. For example, I have a folder in my personal account called trees that holds each of my projects. Clicking on any folder showing in your web browser will launch the index.html found inside it. If not found, Apache shows a list of files and folders it discovers. Explore until you find your project’s starting point.

With this change, you have a web server that I’m confident will meet your needs for a long time to come. You’ve already brought a tool into your workflow that will boost your productivity by catching errors before they get out to your customers. Furthermore, this tool will be a platform that you can enhance over time.

One more change you might like to make is covered in the next section for advanced use. Changing more configuration files lets you get even closer to the production world and set up an expert work environment. It’s not important for now, however.

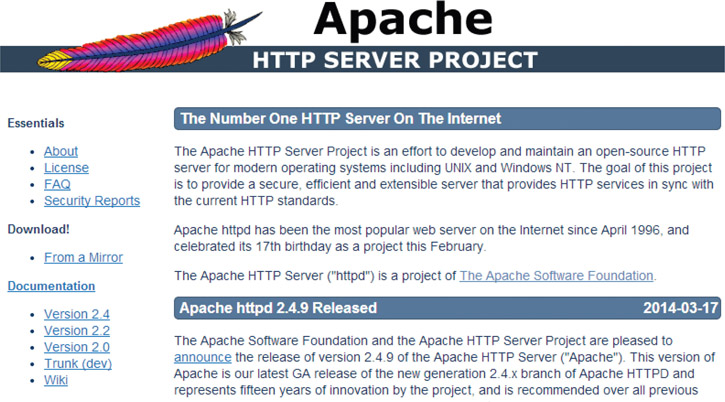

Installing Apache on Windows

Installing Apache on Windows begins with simply downloading a single setup file from the project’s website. Some people expect it’s more complicated than that given how important web servers are, but in fact, it’s only a program like any other. Plenty of smart people went through the challenge of building it to make our lives easier. We’re going to take advantage of that starting now.

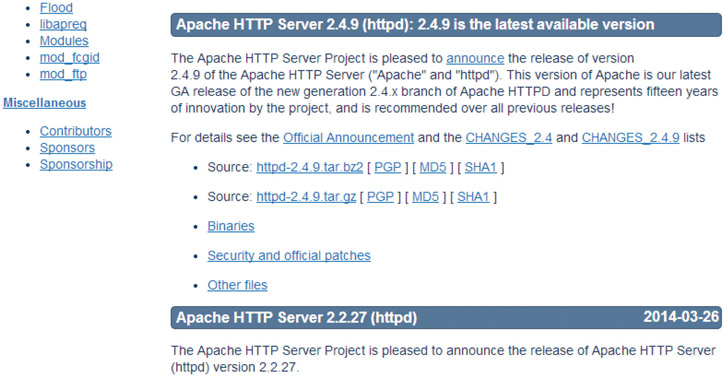

Let’s Go Get the Setup File

-

Open up your favorite web browser and navigate over to httpd.apache.org

-

Click on “Download! From a Mirror”

-

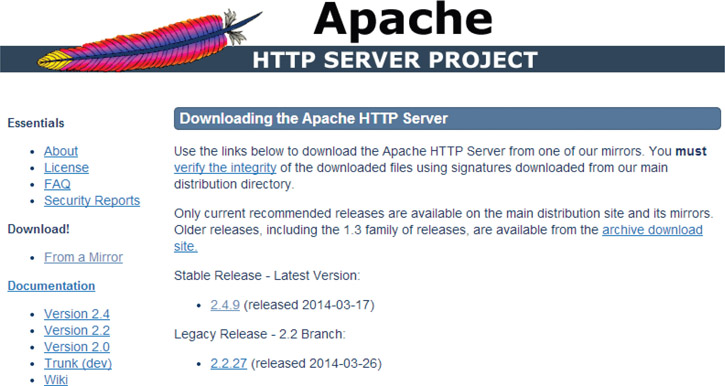

Look for the section “Stable Release” and click on the version (“2.4.9” as of the time of this writing)

-

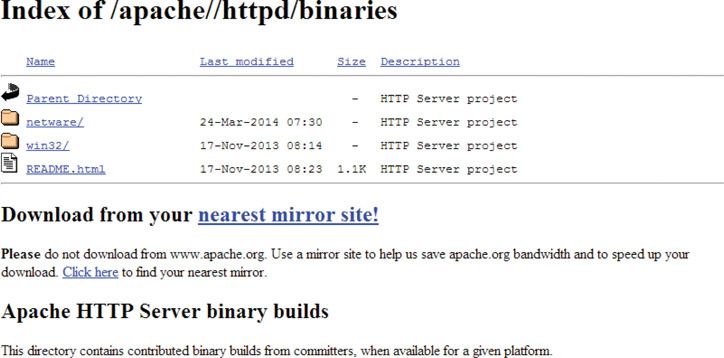

Click on the “binaries” entry to see what’s available for download

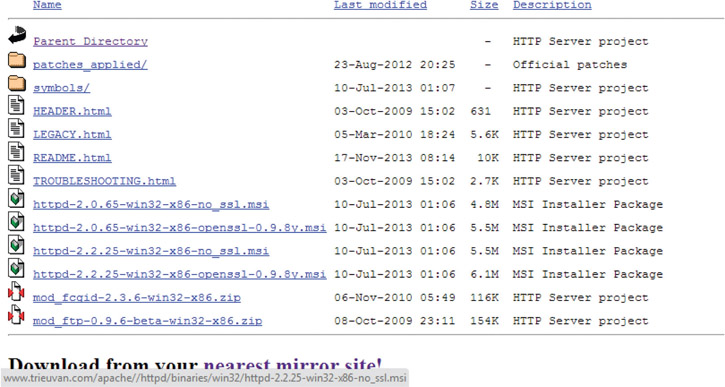

- Click on “win32/” folder

-

Scroll down to the file list and look for the filename with the latest version number and ending with the.msi extension. I found this one: httpd-2.2.25-win32-x86-no_ssl.msi.

- Save that file.

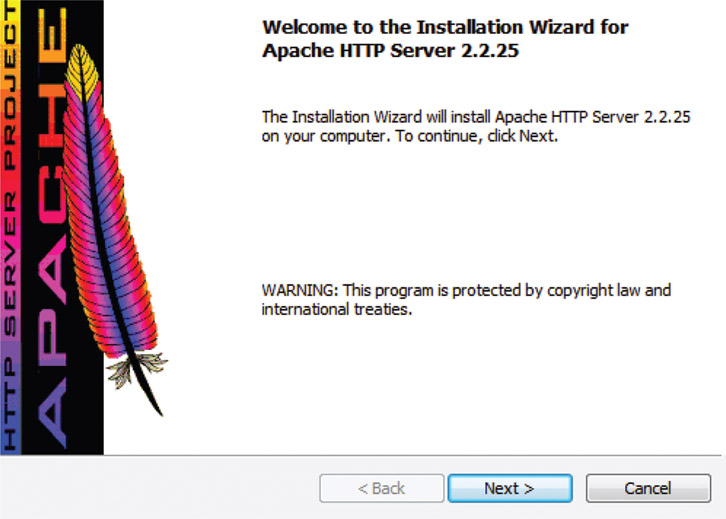

Installing the Server

- Double-click the Apache installer app icon

- Press the “Run” button if Windows asks if the .msi installer is okay for use. It’s simply a safety check that we know is fine.

-

Click on the “Next” button when the “Welcome to the Installation Wizard for Apache” dialog box shows

- Read through the “License Agreement” as you like, pressing the “Next” button

- Read through the “Read This First” text as you like, pressing the “Next” button

-

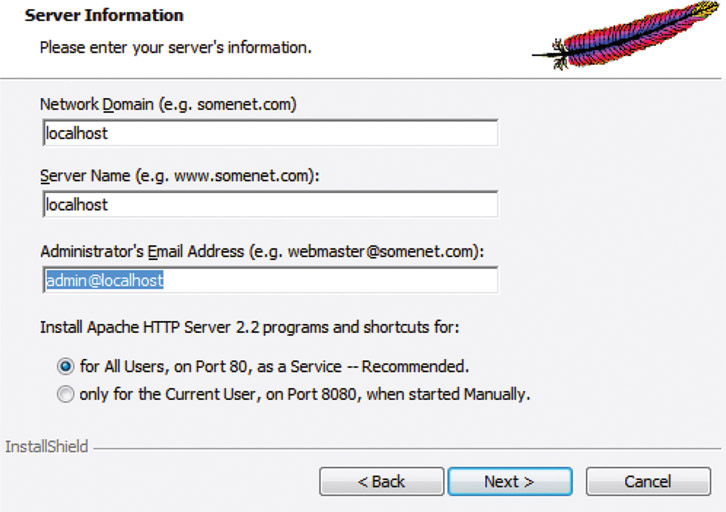

Look for the Server Information dialog box, pressing the “Next” button after typing these values for each entry:

- Network Domain: localhost

- Server Name: localhost

- Administrator’s Email Address: admin@localhost

-

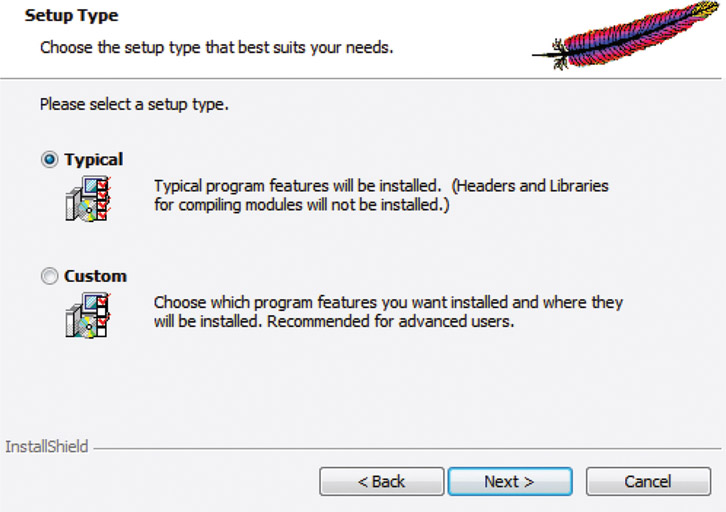

Click “Typical” on the “Setup Type” dialog box and press the “Next” button

-

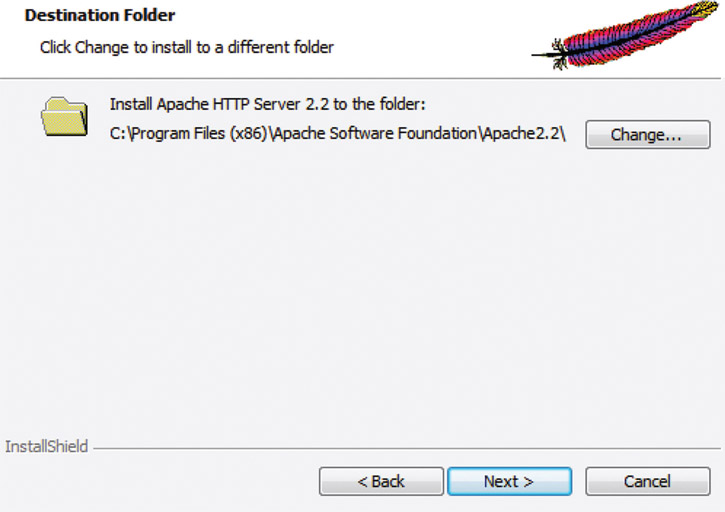

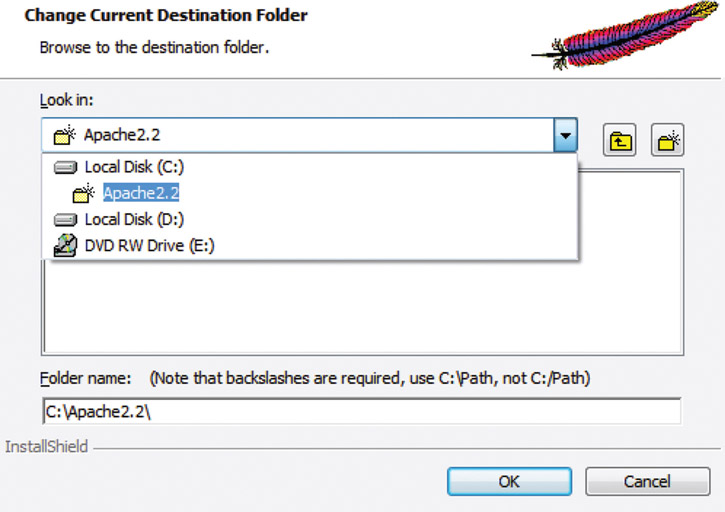

When the “Destination Folder” dialog box shows, press the “Change” button and select somewhere else

-

Change the destination folder to something visible and easily found later—for example, C:\Apache2.2

- Press the “Next” button

-

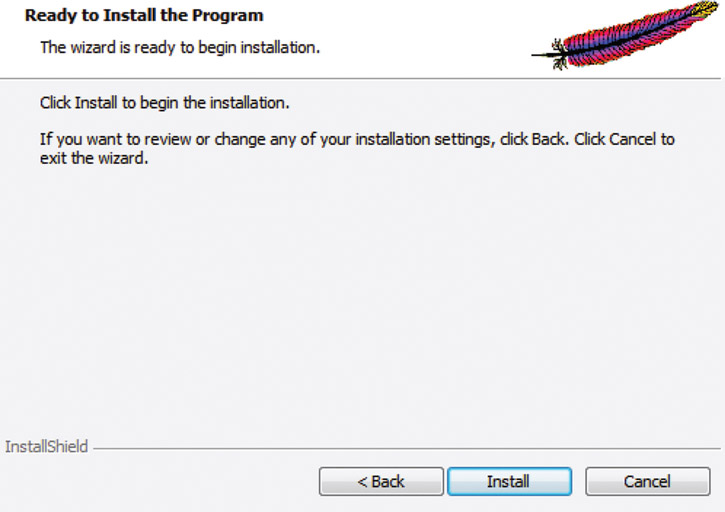

Click the “Install” button at the “Ready to Install the Program” dialog box

-

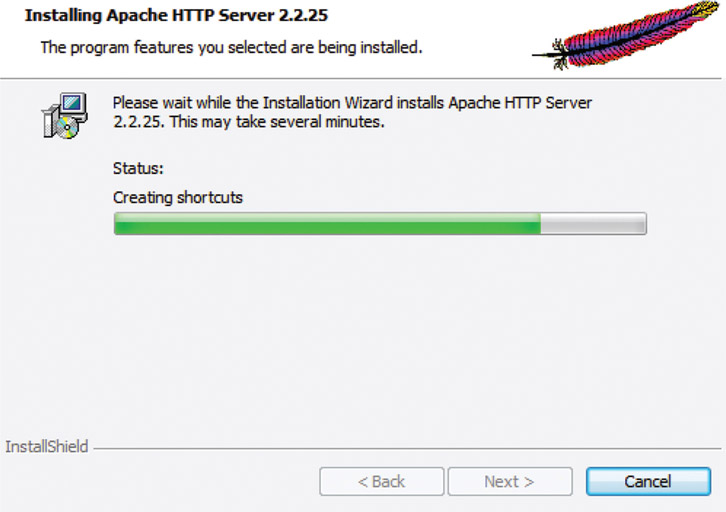

Allow the setup process to copy all the files into place

-

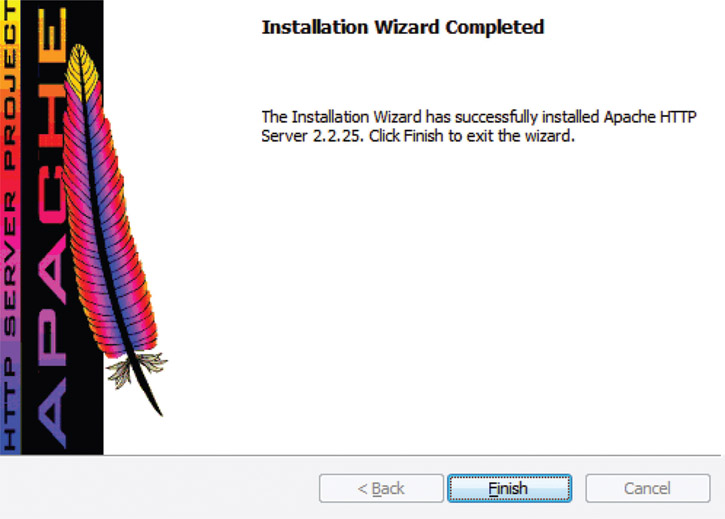

Look for the “Installation Wizard Completed” dialog box and press “Finish”

Are we Done? Is Apache Working?

Fantastic! Now the Apache web server is fully prepared. In fact, it’s already running as you’re reading these words. As part of setup installation, it’s placed on your computer and running in the background. When you reboot your machine, you’ll find Apache running and ready once again, serving up your website as you build it.

How do we know for a fact that Apache web server is running on our work machine? Two important ways come to mind:

-

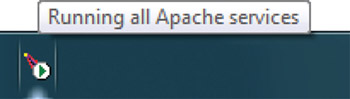

Apache shows a notification icon down in the taskbar area running along the bottom edge of the desktop. The icon looks like a red feather stuck into a white disc holding a green arrow. A label entitled “Running all Apache services” pops up when a mouse hovers above it.

-

Browse your new server! Open a web browser (for example, Internet Explorer) and in the address bar type 127.0.0.1 and then press enter. You ought to see the default Apache web page cheerfully report, “It works!”

The Internet Protocol address 127.0.0.1 is important because 127 is the last address in the A class of networks and 0.0.1 is the first entry on that network. All requests to 127.0.0.1 are specially interpreted as “loop back to this device,” and Apache can catch them.

Beginning Way to Use the Apache Server

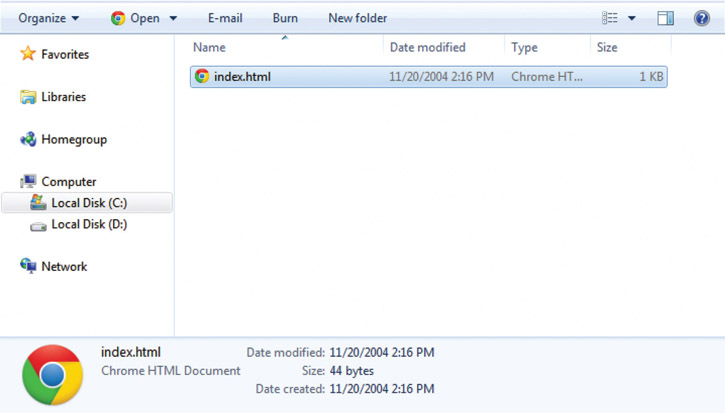

In the previous section, we navigated to our localhost server with a web browser and saw the reassuring “It works!” placeholder page. This default page is an index.html file stored in one of the folders Apache installed. Let’s have a look at where that is and what that file looks like.

Open up a File Explorer and navigate over to the folder where you told Apache to install. For example, type C:\Apache2.2 if you used that while following along in the previous installing section.

Open a folder called htdocs and look for the only file held there called index.html. Edit the file, seeing it’s a single-line document looking like this:

Can we use this same folder to store all of our website work? Will Apache serve up our own files to our web browser? Yes! Surely this is the easiest way to get some work done quickly while playing around with your latest development tool.

Congratulations! You now own a web server. Shiny! It’s worth having some fun playing around with it. When you’re ready, come back to the next section when you want to raise your game a level. It’s worth taking the time to see how you can fine-tune and improve your Apache server to better work for you.

htdocs is an abbreviation for “hypertext documents,” which refers to the original idea of authors relating supportive materials to one another by quickly followed connections. Now it’s so commonplace to “click on a link” that we rarely think of it, but back in the day, it was a significant invention.

Intermediate Way to Use the Apache Server

You’ve already seen in the previous section that you have an Apache web server running. Your localhost is working, and it’s a fantastic tool that will serve you well. If you’re using it, your website pages will come up looking more like how they will in a live production environment. Empathy is a strong tool, and this lets you see your work nearly the same way your customers eventually will.

Because the Apache server is running and serving up your files, you may find the next section isn’t absolutely necessary for getting work done. True, but I believe it’s helpful for adjusting the tool to better fit your work life.

Does it feel as though moving your files in the Apache folder is inflexible and leads to extra effort? I agree. What I do instead of moving my work is teach Apache where my working folder is. Then it can look for and serve files from there.

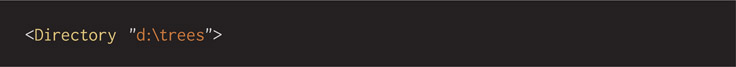

For example, as part of my workflow, I keep a folder called d:\trees, where all my various project folders live. If I tell Apache to consider that its document folder, then I easily access all my past and current projects. It’s perfect!

Teaching Apache where our work folder is means updating one of the files it created during installation. It’s a text file full of its various settings called a “configuration file.” We’ll change the file in two places and restart the server, letting it switch over. Then we’ll have a coffee and admire our work.

- Open a File Explorer and click on the folder you installed Apache into—for example, C:\Apache2.2 if you used that while following the installing section

-

Double-click into the conf folder

- Open the file called httpd.conf with a text editor of your choice (could be Notepad or another one listed in a section that follows)

-

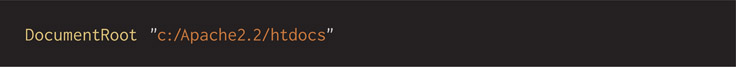

Page down and look for the first line we change. It looks like this one, which was line #236 for me

-

Replace the text inside the quotes with a full folder path to your work folder, as I have here for mine:

-

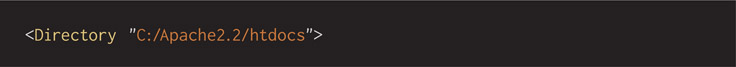

Page down and look for the second line we must change. It looks like this one, which was line #237 for me:

-

Replace the text inside the quotes with a full folder path to your work folder, as I have here for mine:

- Save the file and quit your text editor, because you’re done with the changes.

- That was simple, right? There are lots of hardcore-looking settings in that configuration file that quickly get technical. No need to touch them for now—or ever, unless you want to specifically learn more about them one day.

-

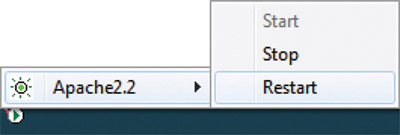

Restart the Apache server. Remember that red arrow notification icon in the taskbar area that we saw earlier? Right click on it and select the “Restart” option. Give it a few minutes to turn itself off and back on again. Let it forget about the old settings and read in the new ones you’ve just changed in httpd.conf.

-

Open your web browser and navigate to 127.0.0.1 once again. What ought to be different is you’re seeing a list of folders in your working folder. For example, I have a folder in d:\trees for each of my projects. Clicking on a folder will launch the index.html found inside it. If not found, Apache shows a list of files and folders it discovers. Explore until you find your project’s starting point.

With this change, you have a web server that I’m confident will meet your needs for a long time to come. You’ve already brought a tool into your workflow that will boost your productivity by catching errors before they get out to customers. Furthermore, this tool will be a platform that you can enhance over time.

One more change you might like to make is covered in the next section for “advanced” use. Changing more configuration files lets you get even closer to the production world and set up an expert work environment. It’s not important for now, however.

The networking industry uses localhost to refer to this computer hosting programs and information. It’s your “home.”

Advanced Way to Use Localhost Apache Web Server

Considering this chapter outlined beginning and intermediate ways to use Apache web server, you must be wondering what’s next. What’s the “advanced” way to use this new power tool that we’re bringing into our workflow? We’ll save details on the next level of Apache for later just to keep life a bit simper as you concentrate on living with this tool for a while longer. Take time to practice with it as you know it now. It will serve you well. Gain confidence configuring it, starting and stopping it, and generally becoming your local authority on the tool.

When you’re ready, flip forward to Chapter 6, where “Virtual Hosts” are covered. It contains what I consider to be the advanced-level knowledge for this book’s audience. That chapter shows you how to have your local web server run in a way that mimics multiple web servers. Each virtual web server is set to deliver one of your folders full of the source code that makes a particular website. When you get to that point, you’ll find it’s useful to have multiple virtual servers running on your single computer.

Each virtual server can have its own hostname just like any website on the Internet does. Using virtual servers in this way makes them feel more real and, in turn, helps you deliver more convincing demos to your clients to enable them to give more detailed feedback. It also helps you discover missing details that you need to complete before launching the site to a public-facing server.

Hinting at Future Configurations

Of course, web servers don’t stop at serving up website files such as .HTML, .CSS, .JPG, and .JS. You could extend your localhost server with various additions, making it even more capable of comparing to live environments. Especially interesting are programming languages or setting upgrades. These optional modules can include:

- PHP, Python, and Perl scripting languages

- SSL security

- Resource cache control

- Support of new MIME file types

- MySQL database

None of these is the least bit important to you at this moment. You’re at the early steps of incorporating this powerful tool into your daily workflow and ought to be completely satisfied at that progress. Spending time using Apache to serve up your website project is entirely the best use of your time.

Investing more time in looking into the details of the httpd.conf file isn’t worth it yet. Is it worth doing in the future? Possibly. It surely would open up another level of power to you, but more than likely, this will happen when pairing up with a back-end software engineer. When a designer pushes to the next level, integrating his or her front-end pages with an engineer’s back-end server layer, that’s a whole new level of spectacular. Think of that now, explore potential in the future, and take it on once you have confidence and have mastered your current potential.

Brief Tour of Text Editors

Why are text editors specifically called out as special? It’s because certain programs, like we’ve already seen with Apache in this chapter, offer special ways of changing their behavior through “configuration files.” The only way they work is when the configuration file is purely text. No special formatting is needed or allowed. No need to mark text in italics or with colors or with special composition as a word processor might.

Reading and writing files made up purely of text is when programmers reach for text editors. In fact, they’re used by programmers so often that this category of tools is referred to as “programmer editors.” By now you’ve chosen one for your own.

What types of files do we recognize as pure text? Plenty. Of course, you know several very well by now: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It’s no coincidence that they are text considering they consist of program code. Pictures that you’ve made in .JPG, .PNG, and .GIF format are not text files. They are referred to as “binary files.” The information stored within them consists of numbers specifically interpreted by viewing programs as pictures. Opening a binary picture file in a text editor will partially reveal its insides. Generally they’ll look like messy junk. Don’t be surprised if they beep at you a bit.

For good times, casually ask a group of software engineers, “What’s your favorite programming editor?” Take a step back and watch where the debate goes. Lots of times it’s a good conversation as a highly opinionated group with a strong stance on the matter banters back and forth. Why is it such a big deal for a programmer? Because text editors are a daily-use tool. Furthermore, it’s a constant touchpoint, and there are enough choices with strong opinions by their makers that committed ideas exist on the matter. Feature-rich text editors make programmers more productive, and they ought to know them well.

Productivity springs from the features making text editors truly a unique tool over word processors. Both seem similar, but in fact, once you deeply learn how to wield a text editor, you’ll find its power. Text editors help far past editing an Apache server configuration file, because it’s a daily touchpoint for crafting source code for your websites. Prepare to have a text editor boost your ability to write JavaScript, HTML, and CSS. These are the ways you can better wield your text editor:

- Learn the hotkeys to accelerate your experience of moving text around and navigating through your files.

- Seek out and snap in plug-ins to extend your capabilities.

- Customize fonts, color themes, and layout for your personal preference.

If going on about this subject seems humorous to you, believe me that it can be when the proper mix of stubborn people start comparing notes. What’s even more fantastic is that you’ll form your own strongly held belief on the matter soon enough. All I can say is that professional makers need tools, and those become extensions of them and, in turn, shape their outlook and attitude. Pride in craft is never a bad thing. Stand up for what you believe in, have opinions, but be ready to learn while you’re sharing.

You may be happy with the text editor that comes with your computer, but I encourage you to go out and choose a few to sample. Work with them and see which fits your style and budget. Listed next are a few highlights for each system, but there are many more choices to discover. Learn by reading reviews of them through web searches, interviewing teammates, or asking at local meetups. Some text editors are free to use forever. Others offer free evaluation time before deciding to buy.

Text Editors on OS X

Here are a few well-known text editors that run on OS X computers.

- TextWrangler

- Sublime Text

- TextMate

- Atom

- Brackets

- BBEdit

If any of your software engineer buddies tell you to use a text editor called VIM, run away. It’s the sort of low-level tool that hardcore UNIX-heads love to use. It’s cryptic on purpose, running on the command line, revealing nothing about itself. Looking at it makes me think it’s the working definition of an anti-user interface. It does work well in this situation, and it’s built into OS X, making it an obvious choice to reach for. Instead, look for its equally useful but slightly more self-revealing “nano.” It runs in a Terminal, and you can edit an Apache configuration file like this:

- Open a Terminal window

- Type sudo nano /etc/apache2/httpd.conf and enter

- Enter your password to confirm administrator privilege

Text Editors on Windows

Here are a few well-known text editors that run on Windows computers.

- NotePad++

- Sublime Text

- Brackets

- Atom

- UltraEdit

Stopping Apache Web Server

You might be wondering, now that you finally have Apache web server running, why would we talk about stopping it? That’s a fine question, and I agree. This was a question that came up from an attendee after I gave a conference talk reviewing these tools. The attendee happily told me that he followed along with my presentation and executed the steps on his machine as I reviewed from my projected slides. He told me he is the type of technically minded designer that I hope to empower, and he literally never knew how easy it was to run Apache on his OS X laptop. He had it running inside the start and stop of my 45-minute session. Of course, I couldn’t have been more proud of him and satisfied that I served my community.

Still, he wondered how to stop Apache, and I hadn’t covered it, but I’ll list it here. From my perspective, there’s no need to stop Apache, but admittedly, it’s my point of view. When Apache is installed and started, it writes to a little configuration file in the operating system that “flips a switch” so that it can rise up and run on reboot. The goal here is the convenience that developers, designers, and engineers will have their system ready to rock starting each day of work.

Asking to turn off Apache might simply be a matter of habit that we’ve all learned since childhood. You’ll recognize one of these messages that comes to my mind: “Clean up after yourself,” “Waste not, want not,” and “Tear down after testing.” Considering those memes kicking around in my brain, I can’t blame the enthusiastic attendee for asking me how to turn off Apache.

Someone might be a bit security conscious and want to be sure their work in progress isn’t something others around them can see. That’s a real daily consideration for contractors and for developers in government-related offices. Realistically speaking, Apache running in the background doesn’t take up many resources from your operating system or hardware in comparison to image editors, programming editors, or streaming music players.

Whatever the point of view, we will review how to stop Apache. Practicing it surely enhances our knowledge of this tool all the more.

Stopping the Server on OS X

Once Apache server is running, it keeps running, even on reboot, until you command it to stop. Here’s how you do it.

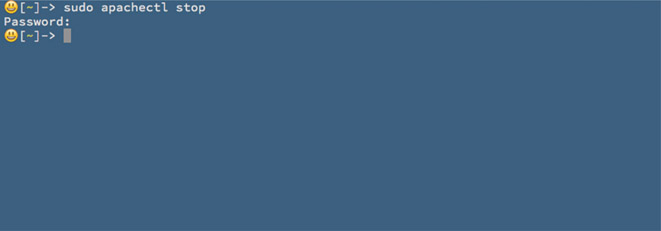

- Open a Terminal window

Enter sudo apachectl stop

- Enter your password to confirm administrator privilege

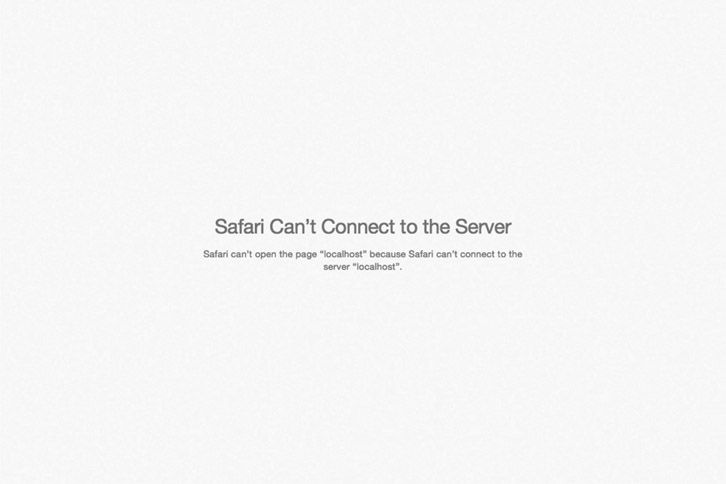

Now Apache web server is stopped. This is easily confirmed. Open up a web browser of your choice, for example Safari, and aim it at localhost and watch the response. It ought to report back a generic message of the idea “Cannot connect to the server.”

Stopping the Server on Windows

When you install and start running Apache web server, it will continue running even across reboots. Stopping it takes a few point and clicks.

- Remember that Apache shows a notification icon down in the taskbar area running along the bottom edge of the desktop. The icon looks like a red feather stuck into a white disc holding a green arrow. Click on it to see a pop-up of choices.

-

Select Apache2.2 and see its submenu list

- Select Stop

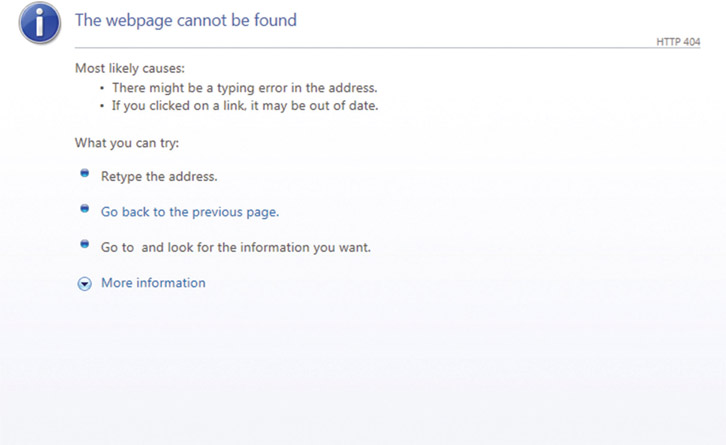

Now Apache web server is deactivated, and it’s “flipped off the switch,” telling Windows it’s not going to run again on reboot. If you want to confirm that Apache is no longer running, simply open up a web browser of your choice, for example Internet Explorer, and point it at 127.0.0.1. What you see in response ought to be a typical generic message along the lines of “The webpage cannot be found.”

OS X Upgrades Can Bring Apache Web Server Changes

Upgrading your OS X operating system generally brings along an upgraded version of Apache Web Server since it’s bundled into the package. Upgrades are good because they bring routine enhancements, optimizations, and bug fixes that you’ll want to use. Upgrades can be confusing for a few moments because your setup will apparently stop working. Configuration changes that you made while editing httpd.conf will be overwritten with the latest default values during the upgrade process.

When you upgrade OS X, and it seems as though Apache Web Server has changed back to its default file serving behavior, recognize it’s time to redo any changes you’ve made to httpd.conf.

You might get an early hint that something is going on based on writing and chatting from people you follow online. Another source of help will be found on this book’s companion web-site http://www.hammeringresponsivewebdesign.com. Use it as a guide to help you work through upgrade events to quickly return to working order.

Alternatives to Apache

You now know how to install and run the Apache HTTP web server. You’ll quickly find it to be a key technology in your toolbox for hammering responsive web design into shape. Chapters 5 and 6 introduce new ways for you to extend your use of the Apache web server.

Human nature always makes us wonder, “Is there another way?” In this case, is there another way to install Apache? Is there another type of web server?

Alternatives—Packaged Installers

At first, installing a web server seemed intimidating and out of reach, but now you have yours running well and are getting comfortable using it. Some of your colleagues might think installing it by hand feels too difficult and beyond their comfort level. How will you counsel them? They might ask if there’s a simpler way to install Apache.

There are alternative ways to install Apache. Certain “all in one” bundles seek to install Apache as well as extra features not yet important to us. What types of features? Examples are a server-side language for business logic and a database for storing user data. Rest assured that because you have installed Apache now, these additional elements could be installed in the future if needed.

Private companies and open communities maintain bundled installers. If someone wants to use one of these bundled packages and asks for your help, explore these keywords in your favorite search engine to learn more:

- “LAMP”—an acronym for Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP

- “WAMP”—an acronym for Windows, Apache, MySQL, and PHP

- “XAMPP”—an acronym representing “X” operating system, Apache, MySQL, PHP, and Perl

I want to deliver a word of warning to you as we review this subject. One of my designer colleagues showed me a packaged installer he used. It was recommended by one of his off-site developers. I’ll assume the advice was given with good intentions to get his design partner going, but in fact, it limited him. The packaged installer offered an easily used interface that specified what website folder is served up by localhost. The problem is that the seductively easy-to-use GUI only provided a single active folder and therefore only one website available at once. That’s terribly weak given what you’ve already seen in this chapter. We can do much better than a single directory and website at once.

When you’re looking at these, you might ask, “Are these really easier than what I did earlier?” That’s a fair reaction, and the answer is “yes” only if you need to solve the problem they’re built for—installing many things at once. Do you need that problem solved? Not so far.

Alternatives to Apache Web Server

Apache web server remains the most popular selection for hosting and serving web files. There are enough alternatives that we have a real choice. Why would we choose an alternative if Apache works fine? Sometimes it’s just a matter of taste. Each has its own profile of awesome that might compel one team to reach for it on their project.

More often than not, this is a choice made by teams spinning up the customer-facing servers. Live production environments may have certain unique needs that we creators do not. Apache will be the best fit for the overriding majority of us for a long time to come.

| Server | Key Benefits |

|

|

|

| Nginx | Quickly serves “static” web pages, lightweight and intentionally kept lean, portable running across many operation systems |

| lighttpd | High-capacity with an eye toward scaling, lightweight and intentionally kept lean, portable running across many operation systems |

| Internet Information Server (IIS) | Microsoft made and well integrated with their technology ecosystem, concentration on administration tools, enterprise friendly |

Although you can plainly see these choices exist, please understand this is an advanced topic that I won’t ask you to put too much thought into. Simply treat this as a “nice to know” item. By asking around and through reading articles, you will discover more servers exist.

Many are highly focused concentrating on solving particular problems such as a specific type of file, offering an operational behavior, or linked inside a specific type of technology. More than likely, you’ll never need to make that choice. Instead, a network operations team as part of a larger company will evaluate and adopt that server.

Apache + Laptop = Localhost #Joy

This is an exciting time! Successfully installing and configuring this software has elevated your skills above those around you. Feel free to keep your knowledge for your own advantage, or share it in the spirit of serving your team and community.

Software engineers have used Apache web servers for a long time, and now you’ve caught up with them. How will you soon surpass them?

Having a web server at your disposal, conveniently running on your working laptop, is rapidly becoming a commonplace necessity. It’s a pragmatic tool for confirming work, validating assumptions, and catching problems before delivering a design into customer-facing production servers.