Chapter 6

Virtual Hosts

What Can Make Apache Web Server Better?

By now you’ve installed Apache on your personal development machine and conducted your first experiments in serving up your website to connected devices. As you’ve had a chance to see your work in progress on real-world handhelds, you’ve found breaking points in your responsive web design working. Images will scale up and down as needed to match changing screen widths. You’ve found that your stylesheets and JavaScript resources come across the air and land on your handhelds quickly enough to satisfy your impatient and busy customers.

You’ve taken up this powerful tool, internalized its value, and brought it into your design development workflow. I absolutely expect that by using it, you have made quality polish changes faster than ever before—changes based on more frequent critiques from your team-mates and demos to your clients because your work is more easily viewed in real-world conditions. Each of your milestones ought to deliver better-quality HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code, as bugs are more easily and more quickly found and fixed without dragging them on to subsequent milestones. You may find each milestone is functional, reliable, simple, and production ready.

I hope you have completely learned how to display your website through localhost for viewing on connected devices, played with the process, and gained confidence. With enough practice comes self-assurance of how the tools work. From there, I hope you’ve used your learning as an opportunity to serve your teammates by showing your experience with them. If you foster a team culture of sharing and learning, the result will be a good team getting better.

The next level of sharing is with the larger community. What community? It could be meeting up with your local professional group to compare notes. It could be speaking at a regional or national conference. It might be sending out an enlightening tweet, putting up a library into open source, or submitting a pull-request that fixes an existing source code repo. The form this next level of sharing takes is up to you, but it’s worth it because it makes all of us better.

As you’ve gotten the hang of using Apache localhost well enough to teach your peers and share with the larger community, you must be wondering, “Is there something better?” Some people might think that’s ridiculous. They think you ought to be satisfied and happy with the new tools you have now. It’s only human nature to be discontented just as we reach a sufficient level of comfort and plenty. I think asking questions such as “Is there something better?” is how we’re going to get to the next professional level of our craft.

In fact, this tool has a next level of “better.” Granted, it’s not crucial for getting your work done, but in fact, it’s a next-level technique worth learning and experiencing firsthand. It’s using Apache’s notion of “virtual hosts.”

Brief Introduction to Virtual Hosts

As you’ve been following along, you currently have one website hosted locally. It’s proving a big help, but you probably have many projects going on at once. You have a new website in preproduction, continued support of a client site in production, a hobby project, and your company’s own home site. I know this happens all the time because designers and developers tell me so when I’m out speaking at conferences.

I’m presenting virtual hosts to you as a way of keeping all those sites active on your development machine but separate enough to make sense of the projects individually. Virtual hosting is the feature of Apache web server that enables you to run many websites at the same time on the same machine.

How does a virtual server work? Practically speaking, it consists of individual bits you already know. When the parts are packaged up, they form into a powerful tool for your toolbox. Virtual servers simply incorporate:

- Your website’s files organized in a folder

- A configuration file with specific details (another .conf file)

- Behind a site URL (www.YourWebSite.local)

Your website’s folder is simply a collection of resources typically used to build up any site that you’ve ever made. It contains a bunch of .html,.css,.js, and .jpg files.

The configuration file is similar to the .conf file that you read and edited in Chapter 4 when setting up your server for “intermediate experience level” mode. We’ll find out it’s a different one that we’ll introduce in the next section. You’ll use it to tell Apache all your various website project folders.

An exciting part is naming the site with its own URL. It will connect to a folder on your local-host machine, but it looks and behaves more like the final product. There’s surely a cool factor having a custom URL naming your virtual server. If that’s not impressive enough, think of how convenient it is typing in a brief, descriptive, memorable URL as opposed to one constructed from localhost and various nested folders.

Creative leaders will appreciate this feature. Virtual hosts on your team’s development environment are an effective way of retaining past sites. You can quickly verify that past sites are working and are ready to roll. Copies of current sites representing polished, functional milestones are always available for client demos that you show either when visiting their offices or on site in your own. Typing in a URL that’s reminiscent of the final production site makes a compelling demo. We all know from reading storybooks as children that names have great power. This is a power we can wield in our working lives. Virtual host names bring an extra level of reality into your creative presentations and raise new opportunities for critiques and evaluation.

Configuring a Virtual Host on OS X

In Chapter 4, we set up Apache to serve pages from its default htdocs folder and modified its configuration to serve web pages from our own projects folder. These two steps are fine for many designers, artists, and developers. One more way Apache can better work for us is if we take advantage of its “virtual hosts” feature. This makes it look as though several websites are running from our single work computer.

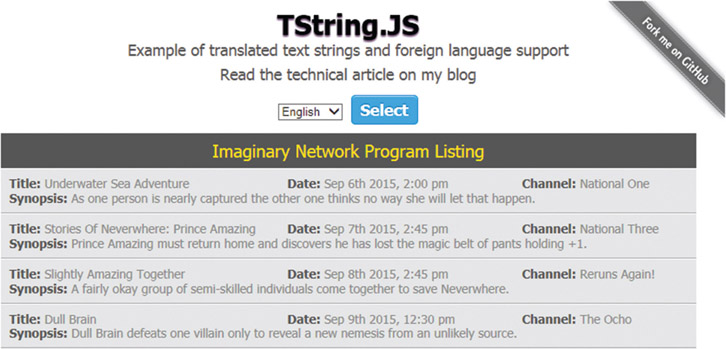

Each virtual web server has its own name, for example, http://www.tstringjs.local, that when typed into your web browser comes back to your work machine instead of going off to search for an Internet site. Apache knows to serve up files from a folder that we tell it about.

- Launch your favorite text editor for OS X (could be TextWrangler or another)

- Click “File-> Open” to navigate to the folder Apache is installed in by default /etc/apache2

- Open the file called httpd.conf with the text editor

-

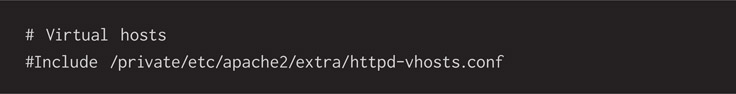

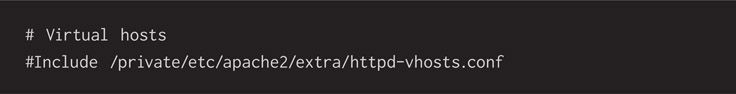

Page down and look for the first line we change that looks like this one, which was line #499 for me:

-

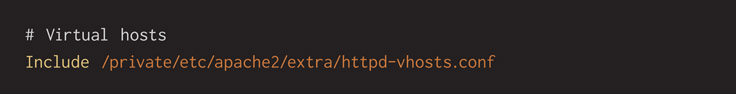

Remove the “#” character that starts the second line so that it looks like this:

- When you first type, a dialog box might pop up that asks you, “Are you sure you want to unlock ‘httpd.conf’?” because it’s a special file. Press the “Unlock” button as confirmation that you know what’s happening.

- Save the file. A dialog box might pop up that asks you, “…wants to make changes. Type your password to allow this.” Do so and click the “Allow” button.

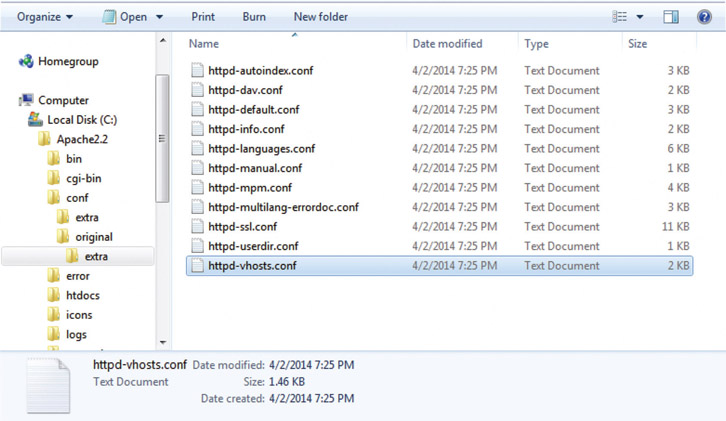

- Click “File-> Open” and navigate to the folder Apache is installed in by default /etc/apache2

- Click on the extra folder inside it

- Open the file called httpd-vhosts.conf

- Delete everything that you find in this file. For me, that was about 40 lines referring to an example “Virtual Host” that’s not important.

-

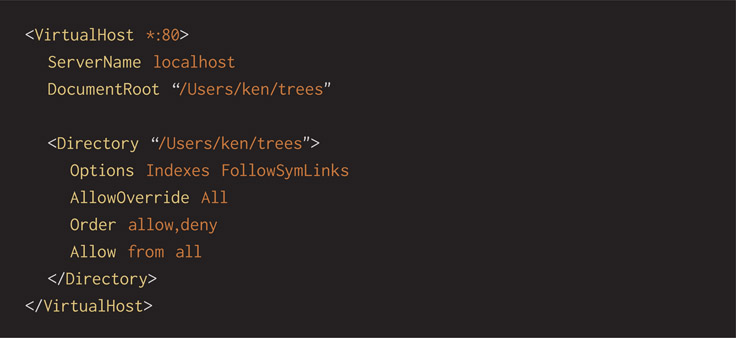

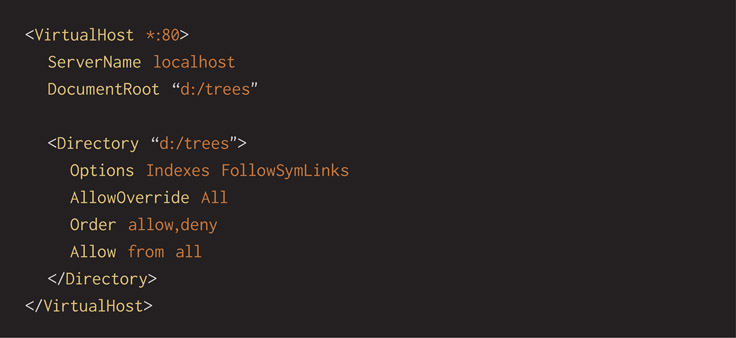

Type this block of text to setup your overall project site. Make it match the working projects folder you used in the previous section. It tells Apache where our general working folder is:

-

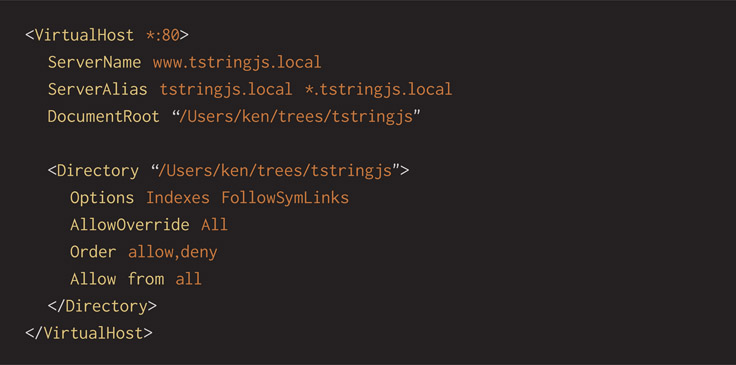

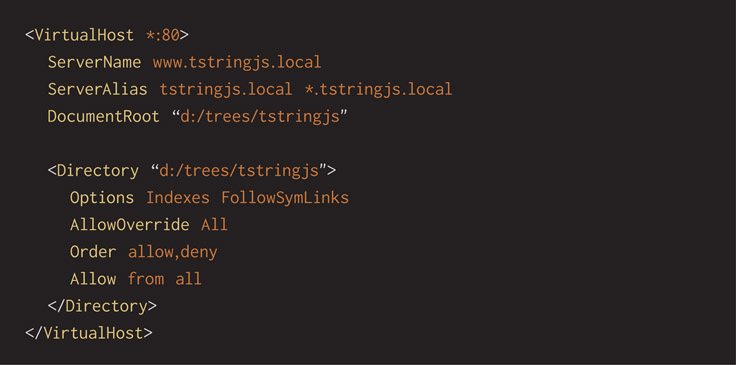

After that block, type this, telling Apache to establish a named virtual server, one that may be opened in a web browser with http://www.tstringjs.local. All files will come from a particular working folder that holds everything that makes up the website.

- Save the file and close it

- Click “File-> Open” and choose a special file called hosts from the special location /etc.

-

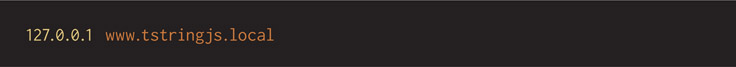

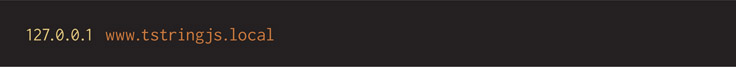

Add this line at the bottom of the file matching the same “server alias” that you added in the httpd-vhosts.conf file a few steps back:

- Save the file and quit your text editor because we’re done with the changes. A dialog box might pop up that asks you, “…wants to make changes. Type your password to allow this.” Do so and click the “Allow” button.

- Restart Apache by opening a Terminal window and entering sudo apachectl restart

- Open your web browser and enter http://www.tstringjs.local into the search bar. Your website’s working files are displayed and rendered as if it were its own server.

Now you have a locally running web server that mimics multiple web servers, with each one delivering a folder of source code matched with a site name. That’s right, multiple servers from a single machine. Quickly confirming what you’ve already guessed, you may easily add multiple “VirtualHost” definitions in httpd-vhosts.conf.

Operating systems reserve a “hosts file” for you and me to use to tell it extra information. Specifically, we use it to declare a network-connected server (a host) that’s not found under normal circumstances (DNS lookups). We can add a line in the hosts file that pairs a human-readable server name with an IP address. Because this file is uniquely important to the O/S, it’s given special read/write permission that usually takes administrative privilege.

Don’t forget how we added matching entries in the hosts file. You’ll do that for each virtual host you tell Apache to serve.

Configuring a Virtual Host on Windows

In Chapter 4, we set up Apache, served pages from its default htdocs folder and modified its configuration to serve web pages from our own projects folder. These two steps are fine for many designers, artists, and developers. One more way Apache can better work for us is if we take advantage of its “virtual hosts” feature. This makes it look as though several websites are running from our single work computer.

Each virtual web server has its own name, for example, www.tstringjs.local, that when typed into your web browser comes back to your development environment instead of searching out on the Internet. Apache knows to serve up the files from a folder that we tell it to use.

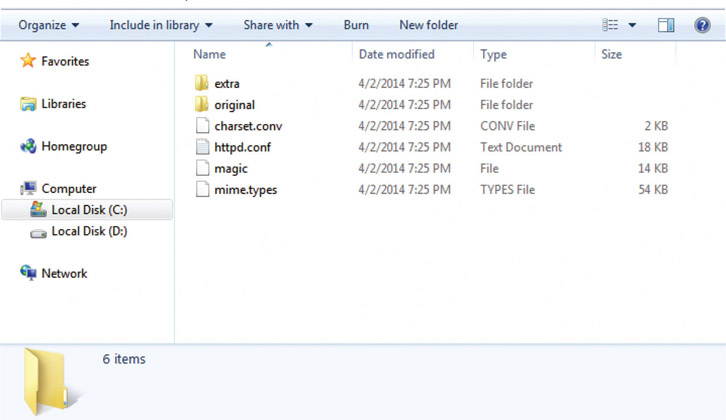

- Open on File Explorer and click on the folder you installed Apache in, for example, C:\Apache2.2 if you entered that following the installing section

- Double-click into the conf folder

-

Open the file called httpd.conf with a text editor of your choice (could be Notepad or another one)

-

Page down and look for the first line we change that looks like this one, which was line #478 for me:

-

Remove the “#” character that starts the second line so that it looks like this:

The pound “#” character has special meaning that tells Apache to skip that line as if it’s simply a comment for the human reader. For example, it could be a reminder telling why a choice was made. In this case turning off a feature until it’s needed.

- Save the file and close it

- Return to the Explorer folder

- Double-click into the conf\extra folder

-

Open the file called httpd-vhosts.conf with a text editor of your choice (could be Notepad or another one listed later)

- Delete everything that you find in this file. For me, that was about 40 lines referring to an example “Virtual Host” that we don’t need.

-

Type this block of text to setup your overall project site. Make it match the working project folder you used in the previous section. It tells Apache where our general working folder is:

-

After that block, type this, telling Apache to establish a named virtual server, one that may be opened in a web browser with www.tstringjs.local. All files will come from a particular working folder that holds everything that makes up the website.

- Save the file and exit your editor. It needs to be restarted in the next step.

-

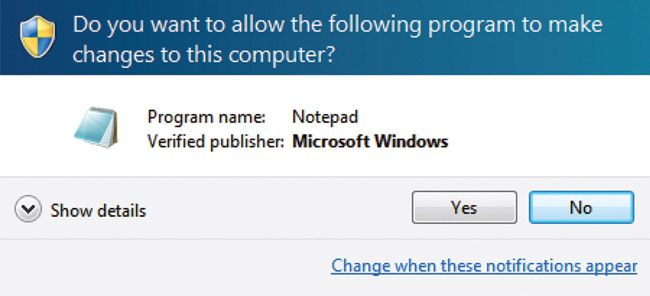

Run your text editor with special permission. We’ll edit a file unique to the operating system that requires administrator privilege. Click on the “Start” menu and right click on your editor’s icon and select “Run as administrator” from the pop-up menu

-

Press the “Yes” button if Windows shows a pop-up dialog box confirming the special action asking “Do you want to allow the following program to make changes to this computer?”

-

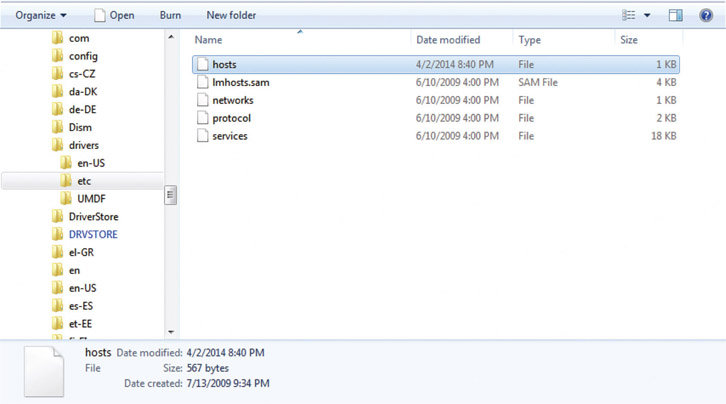

Open a file called hosts that exists in this special location:

c:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc

-

Add this line at the bottom of the file matching the same “server alias” that you added in the httpd-vhosts.conf file a few steps back:

- Save the file and quit your text editor because we’re done with the changes

- Restart Apache

-

Open your web browser and enter www.tstringjs.local into the search bar. Your website’s working files are displayed and rendered as if it were its own server.

Now you have a locally running web server that mimics multiple web servers, with each one delivering a folder of source code matched to a name. That’s right, multiple servers from a single machine. Quickly confirming what you’ve already guessed, you may easily add multiple “VirtualHost” definitions in httpd-vhosts.conf.

Operating systems reserve a “host” file for you and me to use to tell it extra information. Specifically, we use it to declare a network-connected server (a host) that’s not found under normal circumstances (DNS lookups). We can add a line in the hosts file that pairs a human-readable server name with an IP Address. Because this file is uniquely important to the O/S, it’s given special read/write permission that usually takes administrative privilege.

Don’t forget how we added matching entries in the hosts file. You’ll do that for each virtual host you tell Apache to serve.

Advanced Application of Apache

As you’ve followed along with this tutorial, you’ve graduated to the next level of Apache web server usage. Running a server locally makes you more productive. Polish comes more quickly, bugs are found sooner, and viewing your work in progress on real-world handheld devices is casually accomplished. Besides being cool, virtual host names let you demo your work in a way that looks nearly complete.

Virtual host configurations can keep consistency among all of the developers on your team. For example, every artist and developer knows they’re creating http://www.coolsite.local. Each and every person on the team could jump on a teammate’s machine, open a browser window, and bring up that site’s standard .local virtual hostname to see the latest and greatest. The files, however, can be located in any folder on any development machine. Everyone can have a bit of personality in where they work (DocumentRoot), but it’s given the same name by a standard decision (ServerName/ServerAlias). This is the subtle, advanced power of virtual hosts.

Hosting companies sometimes offer virtual hosts for running several customers’ web-sites on the same physical computer server. Some people might think that’s sketchy, because each customer would want their own dedicated hardware. True enough, and some will demand that and will also pay extra for the privilege. Dedicated resources are always an upsell and are certainly necessary for some applications. Others will figure out they have websites that are simply not used enough to generate the customer traffic to justify an extra expense.

Other levels of hosting support include virtualization at the server machine level rather than the web server. Establishing more privacy and protection is the customer offering in this case. Each physical server hardware runs software that emulates a self-contained operating system with Apache running inside it. This boxes off different customers’ work from one another while remaining shared on the same hardware. This is more common with cloud-based hosting services.

Internal operations teams may come to the same conclusion when hosting their company’s own sites on their own network. If a handful of low-use websites can be served up as virtual hosts from the same Apache web server, that’s a good use of a shared environment. It’s a cost-cutting measure that helps a budget last longer as new websites are being spun up and launched. Collect websites coming to end of life on a shared box as usage naturally winds down. Wisely choosing how to use limited resources is a key skill for all of us to learn and practice. Virtual hosts are an advanced tool that empowers that decision.

Life is Not a Happy Path

As a software engineer, I love the “happy path.” I search for it, I build along it, and I test using it as a reliable roadmap. If you’ve never heard the term, the “happy path” is an optimized workflow I use while moving through a website or app that shows the least resistance. Happy paths don’t have crashes, and they produce the most positive results for each step taken. As one small success follows another, it allows me to reach a successful conclusion as quickly as possible to see the features I’m building. Do you recognize that navigation pattern in your own work? You probably instinctively do the same at times purely because it’s quicker and makes development of a workflow faster and easier.

As my favorite QA expert, Cindy, jokingly reminds me, “Life is not a happy path, Ken.”

In fact, her hilarious cautionary tale informs our decisions during the development process. I can’t help but think that if we only build software and websites according to how we quickly blast through them, we’re missing all the sidetracked turns our real users take. Those turns can become infrequent but crucial dead ends that produce bugs, display necessary refinements, or conclude in unexplained conditions that assume too much unrevealed context.

Happy-path development strikes at the heart of how difficult designing, coding, and building a website is. Historically, the tools for viewing, testing, and debugging our sites have been obscure. I aim to empower you to put all these essential tools easily within your reach so you can practice and gain skill. Apache web server and its virtual hosts feature are next-level tools for you to bring into your workflow. They allow you to make mistakes, find them before others see them, and fix them as quickly as possible.

We ought not to stress out trying to decide all the best answers in preproduction. It’s impossible to expect that we can sit down and brain-sweat out all the details by thinking and planning on a whiteboard or paper prototype. That’s okay. Realize those activities are crucial, but then get on with the task of fabricating a project. Start building and forming up your site from the base ingredients of artwork and code. Then test it innocently, childlike, without preconceived notions, just as your new users will. Tools such as localhost and attaching mobile devices give us license to fail quickly, recover immediately, and stay in the creative flow more often. Creative leaders ought to empower their teams to take risks in order to discover much-needed answers.

President of Pixar Animation Ed Catmull writes in his book, Creativity, Inc.,

In a fear-based, failure-averse culture, people will consciously or unconsciously avoid risk. They will seek instead to repeat something safe that’s been good enough in the past. Their work will be derivative, not innovative. But if you can foster a positive understanding of failure, the opposite will happen.

Ed Catmull with Amy Wallace, Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (New York: Random House, 2014, p. 111)

Life is not a happy path, but it’s far from a miserable one, too. Map your roads in exhaustive detail and ensure all the dots are connected by lines forming both the expected and surprising paths your customers need to best use your technology.

Drifting DocumentRoot Up Into the Cloud

Chatting one day with my buddy, Young, a phenomenally talented, adventurous, and technically minded designer, I was struck by an incredibly useful technique that I want to share with you. It’s an advanced notion that you can mix into this already advanced topic of virtual servers. Really, this technique could just as easily help designers and developers at the intermediate level of web server use.

We’ve already reviewed that DocumentRoot in the Apache config files lets you refer to a website project by the team’s standard name (www.TheNewHotness.local) while storing your project files wherever you want to on your personal computer. This small creative freedom offers a fine choice to you for best organizing your universe however it most makes sense to you. What if there’s a better place to store your website files than your personal machine? “Better” might be subjective, but here’s an alternative you could find interesting.

If you use a cloud-based file-storage service such as Google Drive or Dropbox, you might have installed their sync application on your computer. Both of these services in particular offer extensions for Windows and OS X that make their server-based folders appear as if they actually exist locally. What happens if you point your Apache configuration file’s DocumentRoot to the folder established by the cloud service? That sounds intriguing, doesn’t it?

Why should you consider this crazy way of DocumentRoot at all? Why does it matter whether we can store files online if we simply have our development machine with us all the time? Laptops are portable enough, and that seems to work for us so far. Of course, this scheme isn’t for everyone, but thinking it through, we can figure out several cool and valuable reasons for placing our website’s work files on a cloud storage service:

- You can edit your files on any computer that’s connected to the Internet. Maybe you’re off site visiting a customer and want to make a tweak before a presentation and only your teammate has their machine. Perhaps you have a desktop machine at work that doesn’t move but want to make adjustments on your computer when you get home.

- Many cloud-based file services offer automatic backups. Extra protection offers a reassuring guarantee that’s a tremendous benefit for smaller groups that might not have on-site duplication facilities.

- If website files are stored in a publically shared folder, you can preview your work to other people, including clients and teammates in other cities, states, or countries.

- Some companies lock down their corporate networks with virtual private networks (VPNs) to protect their resources. While I’d never tell you to break your company’s intellectual property rules, I can tell you that putting files on a cloud-based file server can let you work more flexibly if you need to. Use your best judgment under these conditions.

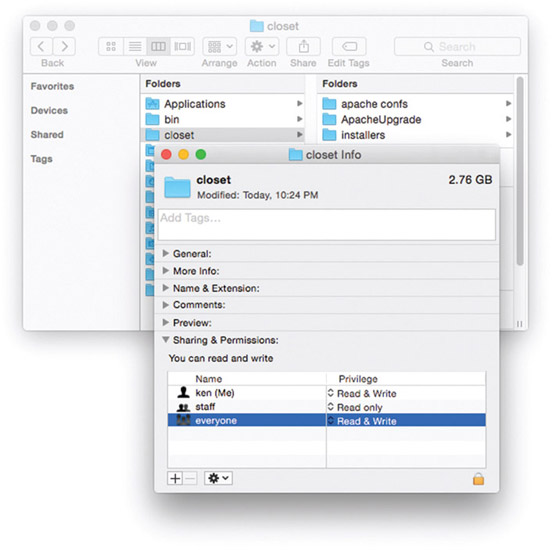

If you go off and try out this trick now, you’ll probably find that it fails. Most of the problem revolves around a permission issue. The cloud-service application extends the operating system and owns the right to read and write files to its folders. Permissions are kept private and “need to know,” so to speak. Apache doesn’t need to know and is kept from peeking into the folders. A work-around is easily within grasp: We can change the permission levels of the folder to ensure all applications across your machine can easily access it.

Changing Folder Permissions on OS X

- Open a Finder window and navigate to the folder created by your cloud file server that you want to set as a DocumentRoot

- Right click on the folder and select “Get Info” from the pop-up menu

- Look for the label called “Sharing & Permissions:” and click on it to open it if it’s closed

-

On the entry named “everyone,” select the Privilege Read & Write

Hardcore OS X users getting more confident with this seemingly “low-level” stuff might have fun skipping Finder and instead dropping into a Terminal window, changing to that folder path, and issuing sudo chmod–R 747 folder-name. Don’t be a sad panda if you’re not ready for this—it’s all a matter of practice before perfection.

A Real Web Server in Your Backpack

Do you feel as though you’ve learned everything you can possibly know about Apache web server? You ought to, because there’s relatively little remaining that we haven’t gone over together. There are many tools for you to discover in the remainder of this book, but Apache localhost is surely one of the strongest and most worthy ones for you to study. Adding this tool to your workflow has made your professional work more organized, brought a more final look to your progress, and helped you find issues across a range of viewing devices.

It’s not overstating to say that you now have a true material competitive advantage sitting on your work computer. As you learn more, getting smarter at your craft with additional tools in your creative workflow, how will you approach what you’ve learned? Will you hold on to your knowledge, keeping it as an edge? Will you share your learning, looking to raise the level all around you? Improving teammates means they have a better foundation to learn upon and share what they master, improving you in turn.

You’ve worked through Apache web server from beginning to end, and there’s little remaining that you might need to know. There are surely more things to learn about it, but pursue them when you have a concrete need. Whatever those details are, be confident that you have the foundation to jump from and leap across the knowledge gap to understanding.

Are you amazed that you have tucked under your arm the same sort of web server that can run a company’s public image? It’s absolutely true. Did you ever think you’d get to that point? Well, you have.