Chapter 2

Introducing the Engineering Process

What Do Engineers Do?

I grew up using tools. You did too. I still recall going through my grandfather’s basement workshop looking at his lifelong collection of tools and wondering if I’d ever have as many as he did. He was an electrician and master of his craft. He had tiny jeweler-quality screwdrivers and iron pipe benders as tall as I was, plus electric drills, power saws, and sledgehammers. He was always encouraging, but I can see now that he only taught me about tools I asked about when he thought I was ready to handle them with respect. These were amazing things for me to learn when I was young. They activated my thirst for discovering, learning careful use. My attitude wasn’t always sensible and respectful, I admit. I burned, shocked, cut, and scared my self plenty, but I always learned—often what not to do as much as how to properly do things. Some of my grandfather’s tools are in my personal collection, and when I reach for them, his patient lessons inform my decisions.

My grandfather had all kinds of tools, but most of them were dedicated to a single purpose. Each was built to solve a particular problem well, but only that one. Computers fascinate me because they’re the ultimate tool. Software adapts them to solve interesting problems for all types of people with all sorts of jobs. By writing a new program, I can make the computer solve new problems for different audiences: word processing, artistic painting, music composition, accounting spreadsheets, magazine layout, adrenaline-junkie driving. While solving problems for people, computers often democratized those people’s jobs. Suddenly we didn’t need a person to do a thing for us; we could load software that helps us do that job. Creative freedom to do a task is a wonderful thing, but it does make me appreciate that inborn talent and years of skill are worth paying experts for.

Growing up as a kid, I was lucky because my stepdad worked for IBM. He bought one of their first personal computers off the assembly line through employee purchase. I cannot imagine he knew what a home computer would do to me, but it captured my imagination totally and completely. Learning programming languages and making software utterly defined my career. In fact, it entirely defined my lifelong interests and unlocked my potential.

What do Engineers Know?

What’s the point of this chapter? Software engineers and programmers know stuff that’s important to them, and that’s fine, but what does that matter to artists, designers, and developers? A lot, as a matter of fact. The job of artists and designers is getting more technical every year. Any of them building websites by writing HTML, CSS, and even JavaScript are in fact programming. Using jQuery and pulling down plugins is integrating libraries just as engineers would. Stylesheet languages, like LESS and Sass are compiled just like the languages that programmers classically use. Because these powerful tools are easily available for free from publically accessed websites, they’re democratizing the job of software engineers.

Let’s continue embracing that skillful movement and mix in more, not to a point of complexity but to connect more dots drawing a line toward new, disciplined goals. I say that professional discipline is what separates hackers and rookies from veteran masters of their craft. We ought to mindfully explore what tools we can bring into our creative workflow, turbo-boosting it to the next level. What are the nuts-and-bolts technologies and techniques that better enable us to deliver quality work, help our teammates, and lend assistance to our community?

It’s my opinion as a software engineer that my community has access to a deep set of tools and techniques that help us better perform our web development work.

Traditionally, that toolset stays within our culture simply for the lack of trying to share it in a simple way with other fields. I don’t want that to continue happening. Tools are an important part of our job, but so too is the understanding of how we choose them, how we apply them, and how we decide to improve or replace them.

Technology is constantly on the move around us. Principles forming our professional foundation stay the same. As programming languages and platforms are replaced, our desire to master craft and point of view on what we want from our tools persists. You’ll see the meaning and value behind those attitudes conveyed in this chapter.

Powerful Tools for a Strong Craft

Tooling is absolutely crucial to developing software. Always has been and always will be. Make no mistake that websites are software. They capture lists of rules telling computers how to behave. In this case, the behavior drives a web browser, telling it how to reach for assets and display those for a user, and waits for that viewer to interact with it. If someone tries to discount your accomplishments by saying it’s only HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and images, I’ll tell them it’s without a doubt a computer program.

In my opinion, building software at scale is the second most complicated thing human beings do. Computers execute rules flawlessly, without hesitation, time and again. Therefore the software logic governing their actions must be flawless. Are human authors capable of flawless work? In other words, can they obtain perfection? Absolutely not, but we think we can. Tools can help.

Tools reduce the complexity of creating perfect websites. One of the ways they do this is by validating our syntax—the words and symbols we type to make our program. In other words, they double-check how we use the grammar of the computer world.

We need help staying more deeply in the creative workflow. Tools watching our work and calling out problems help do that. Bugs and defects in our flawed logic are found more quickly, certainly before problems escape our work computers and get out into the public, where they are more costly—and possibly more embarrassing—to fix.

In real life, the tools you’ve grown up using on projects around the house are easily recognized as time-saving power-ups. You come to quickly understand the use of a hammer, rope, and screwdriver and quickly reach for one when the need arises. You can conveniently buy these at your corner hardware store. Software tools amplify your strengths and abilities in the same way, but finding the right ones is a more difficult problem. Sometimes a front-end development tool goes out of style soon after you hear of it. Often you don’t even know what the choices are.

Choosing your tools at the start of a project is a uniquely personal and important task. Don’t do it quickly just to check a box for your company’s chief technology officer (CTO) or art director. Because you’re a knowledge worker, your software tools are an extension of your creative workflow, imagination, and even identity. Tools influence the way you work and affect who will join you in your work. Remember that you have a choice and that your choice matters, and please make good choices.

Optimize for Change

Reflecting on my career, I’ve decided there’s only one constant, and that’s change. Engineers writing computer program eventually get to the point of talking about optimizing their work. It’s where they invest their greatest effort, concentrated brain sweat, to purposefully write their code, sometimes rewriting the code multiple times until the desired results is achieved. I’ve observed a few common patterns for how software engineers optimize their programs:

- Attaining the fastest running performance

- Consuming the least amount of memory possible

- Using every feature available in the language

- Expressing their own personal style

- Attaining the quickest build time

One or more of these may be important for your project, but in my opinion we ought to focus on optimizing for change. Your time is always limited. In my 25-year career, I’ve used eight major operating systems and written in 13 programming languages while building websites, games, apps, and tools. Given all of the changes I’ve seen, I have no doubt I’m going to see even more, and I expect you will, too.

Consider how your projects change over time. It happens constantly, and we might as well accept that and work within that constraint. Giving up the illusion that we know what the market, users, owners, and clients will want is liberating. After admitting we won’t, don’t, and can’t know enough to properly plan, we can finally build code in the most flexible way possible. We can incorporate as many tools as we can possibly find to help us build an ever-evolving website, experience, and code base. Creative work such as ours means lots of experimentation. We’re never quite sure if what we think in our heads will be good enough when our customers get their hands on it through their devices. Creative leaders should set up a culture in which work can start before all the requirements are discovered, because they never will be. Being comfortable and productive in uncertainty is a highly desirable skill in modern teammates.

Allow for flexibility from the start when defining your testing strategy and development workflow. Design your websites and apps in ways that make it easy to change appearance, function, and deployment. Provide for changes based on advice given by customer feedback. Remind your teammates of this goal and work together on keeping your agility as high as possible.

Source Code

Source code sounds very serious and like it’s something only engineers create. Of course that’s a ridiculous assumption. Every website is based on source code. If you’re building a website and write HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, then you’re producing source code. Source code is one of the most valuable assets a company possesses. (Perhaps the most important one is a fully engaged team living in a vibrant, creative, collaborative culture.)

Because source code is crucial to what we do as professionals, we must guard it well. It’s an asset to our clients and company, and once we’re done making a website, the code behind it is precious. In fact, it’s precious while we’re making it and ought to be treated as a rare treasure. Programmers use a tool called source control that helps maintain source code in a protected way. Source control is a program that keeps source code on a server, offering precise ways of reading and writing to it. That makes it easier for a team to share parts of a program with one another in an organized way. Changes are made in order, kept separately, and recorded in order by date and time. This is called revision history. Programmers like history because it organizes changes submitted by different people on the same files. Everyone must line up in an orderly fashion as the source control system orchestrates updates. If a change unexpectedly turns out badly, the team can refer to the revision history and pull out broken changes, exchanging them for working ones. It’s a massive help.

Source control systems are a specific topic worthy of your time, but this book will not take the time to dive deeply into them. You’ll see some reference to them in Chapter 7 as it reviews how to use projects from one of the more popular and public systems called GitHub. When you want to learn more about source control tools, please look up information on these types of systems: SVN, Git, CVS, and Mercurial.

Single Code Base

Maintaining source code can seem like a full-time job for a creative leader as a team and project gain in size. One reason I admire responsive development is that it tries keeping all views of a website within the same project. There’s no need for two projects representing a desktop site and a mobile site. Over the past years, a dedicated mobile site was a way of solving the complexity of building for handhelds while also supporting laptop and desktop users. This has become a problem because it means two completely separate projects, each with its own source code and probably its own dedicated team. Organizational problems are rife in this environment, and now that solution feels like an example of what not to do. It’s become an antipattern and a cautionary tale.

Responsive development allows a creative team leader to combine previously separated desktop and mobile teams to work together on the same base of source code. They can pair up, solving problems together. Delivering a shared effort lets people get smarter about the project. Now the designers and developers have richer context for the entire project. They can cover each other through illness and vacations and generally empathize with one another, strengthening team bonds while shipping working websites together. Tools become more important to test this shared work because it must be more flexible, considering the world of device sizes we must embrace.

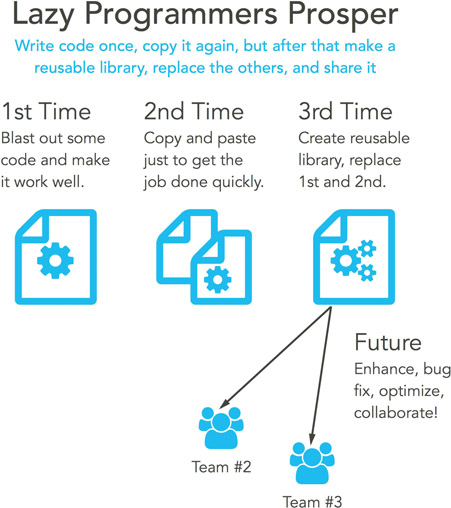

Lazy Programmers are Happier

Business drives us to be more productive, innovative, and engaged. Does it make sense to admit we’re lazy workers or that we aspire to laziness? I’ll shout yes every time I have the chance. When I say “lazy,” does that mean I don’t want to work as hard as someone else? That I’m a cynical burnout whose best years are behind him? Not in the least! I’m driven to perfect and master my craft more than ever.

What I don’t want to do is pull a task, open my text editor, and start blasting code. It’s wrong to assume I know the solution to a problem from the very start. I’d rather invest some time early on discovering what a task is and why it exists. Can I break down a story feature into smaller tasks? Then discover what pieces someone else has already figured out and published as libraries, plugins, or recipes that I can pull into my project? If I can spend 1 hour avoiding 6 hours of work, then I’m winning.

Where does this code come from? The open sources community is distributed in different ways:

- Packaged libraries downloadable from official websites

- Source code repositories hosted on collaborative coding sites such as GitHub and SourceForge

- Snippets written in live coding sites like CodePen and PasteBin

- Solutions on discussion sites like StackOverflow

- Embedded in detailed popular technical blogs

External sites like those are relatively easily found with enough questions typed into your favorite web search engine. More fun for me is discovering ones that are inside my company. They are more difficult to find, perhaps, because it usually means being at your company long enough and knowing people there who have seen such libraries built over time. Some are already inside your project’s source code, but others are hosted in potentially weird spots that only old-timers know.

Building libraries for yourself, your team, and your company is crucial. Answers discovered and solutions made are investments in your future. Creative leaders, please encourage your team to think in these terms. Sometimes a problem is so difficult that your team is relieved when it’s over and moves along. Take time to celebrate the solution, teach others about it, and build a plugin or library or write a page on your wiki. Demand your team makes new bugs. Mistakes are opportunities to learn, and we only fail when we don’t learn the lessons and make them again.

Code reuse is an ideal state. Libraries, modules, and plugins are little nuggets of hard-earned knowledge that make life easier. Try building each of those in a way that it solves one particular problem in an excellent way. Resist the temptation of improving them to a point where people are confused why the library exists. Please consider building solutions to future problems from current learning.

When you come to the point of building something like this, consider ways to share. Certainly share with your own team, but think of the company if it’s a modest-sized agency or a large enterprise. If there’s a chance, find out if you can add your reusable component to the open-source community. It’s a great way to share and attract goodwill, new teammates, and additional help with your work. Open-source projects benefit from crowd-sourced solutions. Imagine people volunteering to improve your work with new features, optimizations, bug fixes, and unit tests.

Every programming language has a community that you can be a part of, whether it’s server-side technologies like NodeJS and Ruby or client-side languages like HTML and CSS.

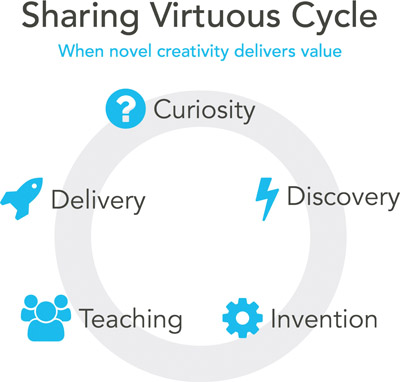

Share

How can a soft skill like sharing possibly matter to a creative leader aiming to arrange a high-performing team? It seems too easy an answer. Let me assure you that emphasizing a culture of sharing is one of the single most powerful things that you can do. “Share,” in the true sense of the word, encompasses a complex and subtle combination of values.

Learn something to share. You’ll always work hard on the job, but realize that genuine learning happens off the clock. Read blogs, follow your favorite creators, trace through open-source code, build side projects on your own time. Why? Because personal hobby projects are where the real learning happens, as you’re creative only for creativity’s sake. It’s the artist’s territory where chasing down fantastic paths of true invention is the only thing that matters. There’s no customer past yourself, no deadline past your own hours, and no goal but solving interesting problems.

As your passion projects spring from daydreaming and into reality, take a chance to demo your experiments to your team. Invest in them, offering a tour of all the work you’ve done. How will they respond? Perhaps they’ll take it and build on your ideas in surprising ways. Bringing something useful and valuable to your team will make everyone around you better.

Listen when someone is sharing. Does your team respect one another enough to stop what they’re doing, turn full attention to the speaker, and invest their time in hearing what they say? One of the meetings I run at my job is a purposeful forum for sharing code and pro tips. My only rule to the gathered audience is giving the speaker complete attention. It’s proper at a professional level and validating at a basic human level. Deep learning comes from hearing, and that comes from deliberately listening.

Cross-train when someone is sharing. Meeting to discuss the most recently solved problems gives the team a chance to celebrate the little successes as they grind out tasks and hit deadlines. Recognizing a job well done is fuel for creative minds to power past the difficulties projects inevitably present. Hard-earned knowledge ought to be spread out among the team. Any answer to a bug fix or CSS workaround is an investment, and passing it around a team lets you grow earnings from the time spent. Spreading answers among people helps break down silos for common understanding and covers the day when the original inventor isn’t around. That happens all the time. Could be that they quit the company, transferred to another group, or were on vacation.

Team build when someone is sharing. Cultural memes are like a viral infection spreading among the brains in your team. Let them demonstrate to one another what’s expected while sharing. New hires will quickly realize that you have a team of outstanding players who seek out others possessing curious minds. Sharing is a sure way to foster candid revelations that leads to solid collaboration. When someone encounters a problem similar to what their team-mate encountered, they know what tool or technique to reach for. Remind one another to make each other better by sharing what’s discovered.

Creative leaders know their purpose is enabling their teams. Enabling them to do what? Someone might say to do better work more often. I think it’s to help a group of individuals realize how to perform well together.

Rothman and Derby paint a vivid description of how my favorite teams have worked well together.

If you’ve ever worked on a jelled team, you know how good it feels. A jelled team has energy. People accomplish great feats. They celebrate and laugh together. They disagree and argue but not disagreeably. Jelled teams don’t happen by accident; teams jell when someone pays attention to building trust and commitment. The jelled teams we’ve seen create and work towards shared goals. Over time they build trust by exchanging and honoring commitments to each other.

Johanna Rothman and Esther Derby, Behind Closed Doors: Secrets of Great Management (USA: The Pragmatic Programmers, 2008, p. 49)

Gaining Confidence

You may know engineers as an argumentative bunch. We hold many opinions on a wide variety of topics and are happy to voice our positions. Although it seems we’re extremely confident in our firmly held beliefs, I can’t help but think we’re always searching for confidence. We know that computers will flawlessly follow our instructions without hesitation or deviation. As we write instructions in the form of programs, we know that we human authors are teeming with flaws and uncertainty. It’s the nature of our limited ability to predict the future. In fact, while computers are flawless at running programs, we know they’re flawed, and we know the people using them are just as flawed. Users can’t follow directions and make mistakes while they believe they’re following them correctly. If we can’t write programs well and expect our customers to make mistakes while using them, what hope is there for success?

Gaining confidence through testing is one way programmers know when they can reliably ship code. Testing techniques and tools are found throughout this book. The goal is finding ways to test on our working computers as often as possible. Staying deeply entranced in the creative zone is key to improving productivity while making the most of our always-limited time. While we want to pinpoint bugs, glitches, and edge-cases on our own work computers, it’s important to realize the true fact: Unless we test our code on real mobile hardware, it doesn’t matter in the least how much work we’ve done. Strategies for testing on hardware are addressed in this book.

Testing by hand is referred to as manual testing. Another tactic is automated testing using various software that emulates human interactions with your software. That won’t be covered in this book, but plenty of material exists on this subject.

Fear of failure is something that we all have. It’s instinctive, and no matter how experienced we are, it’s worth keeping humble while building software. Nothing yet has moved me from my opinion that building software at scale is the second-hardest thing human beings do. Testing lets us move quickly with confidence. It’s important to continue polishing, improving, and evolving our website’s abilities and user experience. Testing helps keep that process moving forward.

Build. Measure. Learn.

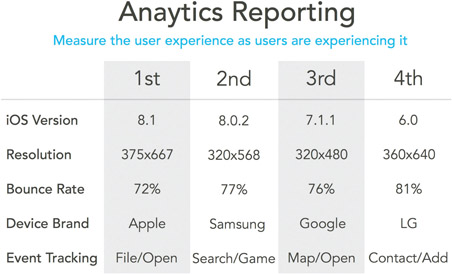

When we build something, how do we know it’s used? Do we wait for user reviews? Do we wait for confused support emails? How can we decide our investment in building a feature was worth the return? Sometimes it’s easier than others. For example, some features will obviously deliver immediate business value in terms of revenue. We might have secondary benefits that don’t provide money but offer other value, such as engagement or acquisition. For these types of features, you ought to implement analytics.

By default, most analytics record when a user hits a web page, which is useful, for example, when you’re building a blog formed from a collection of articles. What about measuring customer interaction on a page with settings, buttons, and sliders? What about a complex web page that’s more like an application than a document? Properly engineering analytics can measure when users tap and slide on a page. Unique interactions can be tracked as interaction events. Sometimes it’s enough to say how often a UI element is used on a page. Sometimes you want to establish a funnel where all the people in the universe can start, some drop off, but others continue along the workflow, step by step, until a smaller group finishes. Analytics provide the factual measure of those steps.

Facts allow us to cut through opinions, gut instinct, and tradition and decide with evidence of our customers’ use of our website and web apps. Watch arguments fall away as your team reviews the analytics reporting dashboard and sees exactly how often specific pages are viewed and particular UI widgets are used. Numbers don’t lie, and analytics disclose candid insights. Find out if an investment has paid off by implementing some form of analytics in your development process and business practice. If it becomes a part of your culture, you’ll find it a material advantage over the competition.

Don’t fire and forget, either. Once you build something, follow up each day, week, month, or quarter and report its use. Craft a dashboard that specifically reports performance on mobile devices (desktop, too, when it’s relevant). Some feature that’s not accomplishing what you expect needs an investment. Schedule time to improve it, or remove it. There are no failures as long as we learn from past performance and choose a different future path.

When you build something, measure it and learn from its results. Bring analytics into your creative tool chain as soon as possible. Let facts guide your decisions. Any large-scale organization might be adding a new job called business intelligence. Don’t let the khaki-and-blue-shirt–wearing pointy-hairs in biz-dev become gatekeepers of the analytics reports. Go get the data, dig deeply into it, and own the results. I encourage you to have heart when you see all the numbers behind analytics. Default dashboards can appear as big-data overload and disable an entire segment of your team. Tell them how important it is to get behind these numbers and not the math that computes them. Craft custom reporting dashboards, and the graphed data will look like art. The numbers will measure your users’ experiences while they actively use the experience.

We’re All Makers Together

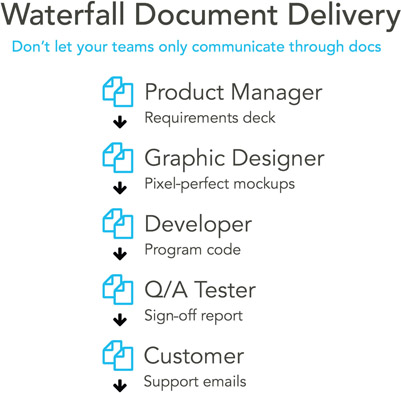

Building software can be a solo pursuit, but at its finest, there are teams of skilled individuals working together. Creative leaders are always trying to get their teams of people working better together. They want to organize their groups to work with purpose and toward a common objective. Ensuring everyone on the team has a shared understanding of what the work is marks the first step of that journey. Listening to stakeholder requirements and building user personas and story-based workflows are all useful tools in coming to a shared understanding. In my mind, past all that, it’s a people problem, and figuring out how to build the team’s capacity to deliver together becomes the crucial goal.

Much is published about finding individuals who are rock stars, front-end unicorns, or full-stack developers. This wrongly celebrates the ability of a single person rather than the capacity of a team. When the team is fully integrated, with personnel filling all needed skills, then you’re building capacity to deliver excellent work. Once the team fully gels to a point that they act almost with a single-minded attitude, then the company will deliver the best work possible in the shortest amount of time.

Building full-stack teams delivering together will involve finding front-end programmers, testers, designers, and product owners. Whenever possible, ensure they sit together. Let them overhear each other’s conversations so that someone with the answer might easily share it. Break down silos if they exist. It’s an antipattern to have all the company’s designers, programmers, testers, and product owners sitting separated by job title. Teams can do better when each individual understands a little about everyone else’s job, too. Your team should be full stack, having all the talent to deliver any feature. When employees of a particular skill or job are exclusively sitting together, then their daily exposure lacks diversity. They lose sight of what other teammates do in their jobs.

Silos might be a problem for your team if programmers “throw their code over the wall” to testers for them to find the bugs. If the answer to a question about a possible bug is “it works on my machine,” then your team is dysfunctional and producing below capacity. Encourage your programmers to give a quick demo to testers and even to product owners and designers before putting a task in the “ready for test” column. Even a 5-minute demo reveals small glitches needing more work. Use this as a chance for the team to expose assumptions, discuss edge-cases, and catch up with last-minute decisions together. Put a little more work into it before it goes to test, and certainly before it goes to your end customers.

Silos might be a problem for your team if product owners are delivering documents to designers before the testing and programming team hears about it. Encourage your product owners to deliver a brief pitch to the collected team. Reveal why the team ought to build or change something. What is the business case and why is it valuable? In meetings like this, you’ll find that testers are fantastic at thinking like real customers. Let them break down assumptions and discover gaps in workflows. It’s time to crowd source answers together. Programmers can offer observations about the feature requests given the context of the website they’ve already built. Let them make suggestions to maintain consistency across the site. Designers have an early opportunity to offer up best practices in user experience and new UI mechanics. It’s a chance to talk together, and that breaks down walls and builds up trust.

Silos might be a problem for your team if your designers get a feature request from a product owner and then go dark for days, building a series of pixel-perfect mockups that are dropped off to developers to build as shown. This waterfall approach to development misses the opportunity for a rich discussion among programmers, designers, testers, and product owners. With communication, there’s a chance to establish shared understanding early and maintain it throughout a feature and project. Pixel-perfect mockups are expensive to change, and change is natural. Do you really want your artists and designers to be in the job of delivering documents? Is it impossible to imagine a tester grabbing a marker and drawing boxes on a whiteboard while talking through a workflow? Does an artist need to always deliver a pixel-perfect mockup, or can they communicate shorthand through an established design language? Have a product owner try roughly drawing a screen on a whiteboard while a pro grammer writes HTML against established Sass/CSS design patterns. Collaboration encourages a team to gel, and an already experienced team in the right collective headspace will always deliver more quickly when working together.

Guide your team to be fully integrated and capable of delivering together. Encourage them do each other’s jobs occasionally. Let a tester be a product owner, discovering requirements, because they’ll fully explore the product like a customer will. Let programmers manually test, figuring out if their code really does work reliably. Let designers write HTML and CSS ready for programmers to hook up with JavaScript. If they all understand what their teammates do for a living, it helps build up empathy. The next time a task becomes difficult, they might be eager to lend a hand, or at the very least understand why it’s tricky and be more sympathetic and accommodating. In a team delivery mentality, no one gets to call something done until it’s been fully tested on real devices. When that happens, a feature genuinely is complete and ready to be deployed to web servers for use by customers. When that happens, take a moment to celebrate success together. Have a cheer, ring a bell, and high-five each other. Whatever ceremonies you decide on, embrace them, and have fun.

Serve your teammates. They aren’t there for your convenience, but instead, you’re there helping them do a better job. Sometimes that attitude drives people to worker harder and dig deeper for one another. I think of it when I’m writing code. I’ve worked with people who believed they wrote code at work for themselves. They would use their preferred code style and conventions, no matter how terse and cryptic. Now I realize that I write code for my team-mates to read, not the browser, and I optimize for human understanding.

I’ve read books on personal relationships, and I can’t help but reflect on their lessons and apply them to my work situation. Consider this one from Gary Chapman as he meditates on the nature of true love and what it takes to obtain and support it.

… love requires effort and discipline. It is the choice to expend energy in an effort to benefit the other person, knowing that if his or her life is enriched by your effort, you too will find a sense of satisfaction…

Gary Chapman, The 5 Love Languages: The Secret to Love That Lasts (Chicago: Northfield Publishing, 2010, p. 33)

To help with your code’s readability, take time to create coding standards for CSS, HTML, and JavaScript before writing any. Write code that looks as if it was written by the same hand. You shouldn’t be able to tell who wrote it. At least a file won’t look foreign when you crack it open to make a change or take over for a departing coworker. Having a common, well-documented code style is recommended, but what form it takes is up to you. If you want a jumping-off point, please question in your favorite web search engine. Many companies have developed their own styles and written blog articles on the matter. Some have even placed them for public consumption on open-source sites such as GitHub.

Optimistic Outlook

I think most people who work with software engineers think they’re pessimistic. They think of what can go wrong as they try writing bug-free code that intelligently handles every known edge-case. In fact, I think engineers are basically optimistic. Technology is so difficult at times that we don’t even know what the potential answers are as we start working on a problem, but we always think there is an answer. If it’s not found today, then tomorrow is another chance at discovering success. Engineers who don’t fundamentally believe that might simply stop coming to work the next day.

At the start of a project, we take time to plan out what needs to be done and spend time trying to ensure nothing goes wrong. That level of control is an illusion, because we’ll never fully know what to do until we get into a project. With that in mind, I say that we’re artists, designers, and developers, and we’re makers. At some point, we must get on with building things. Plan carefully to discover and establish a shared understanding among the team, but then design and code decisively. I find that code working on a device nearly always wins arguments and pushes away doubt.

Creative leaders, please don’t cultivate a culture of avoiding failure by heaping on too much process. Favor communication and trust a team that’s fully engaged and owns the results. Do whatever you can to guide them toward finding solutions. Encourage your team to meet and reflect on the past few weeks, determining what’s working and what’s not. Brainstorm potential solutions for what’s not working and try some. Will they succeed or fail? Not sure, but it’s worth trying and finding out if they become new habits.

Ultimately I judge all code I write by asking if it possesses three simple qualities: Is it functional, is it reliable, and is it simple? Over my career, I’ve used many languages, operating systems, tools, and hardware kits. What has not changed is my attitude toward mastering my craft, and those three simple qualities are how I evaluate my professional work.

My Personal Point of View

My personal outlook on all of this is that building software is fantastic fun. I love to wake up, learn something new, solve interesting problems, and share what I discover. Websites have always been software, and many are clearly heading in the direction of complex programs. Professional discipline and mastering craft are necessary goals for all of us. That’s why I’m eager to deliver a complete box of strong tools to you.

Everything I write comes from slice-of-life experience as an engineer developing websites and web apps alongside artists and designers. All guidance given is written within the context of some problems I’ve encountered and successfully solved. Furthermore, the chapters will review the challenges and pain points I’ve realized collaborating with artists and designers. Striving to make this technology real for you and your crew is absolutely important to me. I see hardworking teammates wanting to excel at their work, and it is my honor to serve their needs. When I started my career, I was head down and self-involved in getting my work completed on time. Now I realize that helping others by revealing what I know is a great joy for me.

Tools are always essential to any job. Mastering them is a necessity, because our job is always more difficult than we want it to be. It’s creative, it’s interactive, we’re proud of our effort, and there’s never enough time.

Working on the front end of a project feels like home to me. One way or another, it’s been the constant focus of my career. I enjoy it because all of my actions are informed by or in the service of a fantastic user experience. It’s how I support my customers—by enabling them to better use our software to solve problems. At the end of the day, producing useful work is a satisfying feeling.

Highly collaborative and multidisciplinary teams are a necessity for building today’s software, more so than ever because expectations are high and competitors’ quality is great. My background building video games showed me that combining programmers, artists, and designers raises everyone’s game to a level so high that we could create worlds. Let’s do the same things in our industry. Break down skill-based silos and ensure a team is well positioned to start and deliver work together.

Consider ways of having your team members teach one another. Hold instructional lunch-and-learns by area experts. Watch inspirational and informative conference videos. Page through exceptional code together. Bring your pet projects in from home to enlighten one another. Continue investing in each other, raising the potential of everyone. Try each of these things and others and see if they become a part of your culture. Initiate new hires by telling stories of how your team has persevered through challenges and evolved into the successful group it is.

Don’t hesitate to pull from the open-source community, but never forget to commit back to it. Support the dedicated volunteers who build the technology from which you benefit. Submit improvements to the source code through GitHub. Blog about how your team uses tech, offering pro tips and tutorials. Publish code snippets answering questions on website forums. Tweet out links to amazing things that you discover. Talk at conferences to educate audiences.

Whenever possible, sell your team on why something has business value, ensure they all understand it well, and then step back. Trust them to make it real and make it better. Listen to them, and remove any blockers when they ask for your help. Hold them accountable for delivering on time.

Overlapping Engineering and Artistry

Why bother learning all this? What’s the point of finding out what software engineers do? The fact of the matter is that you and a large percentage of technically minded designers are already doing lots of the things engineers have been doing for their collective history. Activities such as writing programs, maintaining existing source code, and evaluating libraries are traditional core competencies of software engineers. People might try casting your situation in a lesser light, calling it website development, but don’t let them make your job feel unimportant.

Historically, pundits might have thought designers and engineers operated at opposite sides of the creative spectrum. One side has people based in numbers and the other has them based in art. Many assume both possess completely incompatible worldviews, and even if they’re on the same team, they simply suffer through the day mixed up together. Let’s examine the supposed goals of each class of worker. Designers want a website to work well. They might think of the experience of touching a site as much as the delight of looking at it. Engineers want software to work well. They think of it in terms of it being functional, reliable, and simple. How can those two points of view be fundamentally competing? Don’t they add up to a more powerful view of the user experience customers want?

It sounds to me as though all the individual needs can be met while working together toward a common goal. If creative leaders are directing their teams toward a full-stack, team-delivery–based effort, why wouldn’t all members of the staff desire the same outcome? Strengthening working relationships builds empathy for one another as silos between skillsets start to fall. Negative attitudes of “I have my work done, and I hope you have yours covered” quickly die off. Breeding a candid and supportive culture in which learning, teaching, and openly helping one another makes everyone on the team better. Build capacity to ship more and make the environment more enjoyable.

My goal in writing this book is reviewing many of the most useful skills that I’ve come to possess. I want to demonstrate the most enabling tools that I’ve found. I want to empower your emerging mastery with nuts-and-bolts tactics that have helped me succeed throughout my career. This book is dedicated to you if want to elevate your craft and gain productivity by adopting some of the lessons that seem like the exclusive domain of programmers.

I’m an engineer, and I enjoy collaborating with designers. My goal is enlightening you to various programmer-centric tool and techniques. Curious artists wanting to discover more about the technical side of this industry will find they’re working more rapidly from learning the techniques and tools clearly explained in this book. You will be introduced to ways of making fact-based decisions and critically debugging your work using tools available from the open-source community and various public-dedicated companies. Following along with the techniques assembled in the book, you’ll realize you’re more quickly finding problems on your work computer rather than resorting to the inconvenient effort of using production web servers. You can delay purchase of expensive devices such as tablets and phones for finding routine glitches and bugs.

Each chapter feeds upon the last as you build up a complete toolbox of powerful tools. Because building modern websites can quickly become difficult, we reach for tools to reduce frustration and better stay in the iterative creative flow. Staying deeply in that open mode for longer periods of time lets you accomplish profoundly creative work with less effort.