This book has so far focused on just one reverse-engineering platform: native code written for IA-32 and compatible processors. Even though there are many programs that fall under this category, it still makes sense to discuss other, emerging development platforms that might become more popular in the future. There are endless numbers of such platforms. I could discuss other operating systems that run under IA-32 such as Linux, or discuss other platforms that use entirely different operating systems and different processor architectures, such as Apple Macintosh. Beyond operating systems and processor architectures, there are also high-level platforms that use a special assembly language of their own, and can run under any platform. These are virtual-machine-based platforms such as Java and .NET.

Even though Java has grown to be an extremely powerful and popular programming language, this chapter focuses exclusively on Microsoft's .NET platform. There are several reasons why I chose .NET over Java. First of all, Java has been around longer than .NET, and the subject of Java reverse engineering has been covered quite extensively in various articles and online resources. Additionally, I think it would be fair to say that Microsoft technologies have a general tendency of attracting large numbers of hackers and reversers. The reason why that is so is the subject of some debate, and I won't get into it here.

In this chapter, I will be covering the basic techniques for reverse engineering .NET programs. This requires that you become familiar with some of the ground rules of the .NET platform, as well as with the native language of the .NET platform: MSIL. I'll go over some simple MSIL code samples and analyze them just as I did with IA-32 code in earlier chapters. Finally, I'll introduce some tools that are specific to .NET (and to other bytecode-based platforms) such as obfuscators and decompilers.

Let's get one thing straight: reverse engineering of .NET applications is an entirely different ballgame compared to what I've discussed so far. Fundamentally, reversing a .NET program is an incredibly trivial task. .NET programs are compiled into an intermediate language (or bytecode) called MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language). MSIL is highly detailed; it contains far more high-level information regarding the original program than an IA-32 compiled program does. These details include the full definition of every data structure used in the program, along with the names of almost every symbol used in the program. That's right: The names of every object, data member, and member function are included in every .NET binary—that's how the .NET runtime (the CLR) can find these objects at runtime!

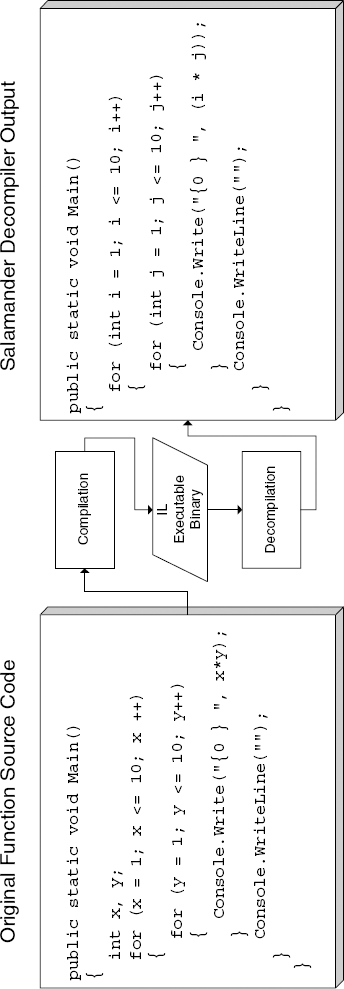

This not only greatly simplifies the process of reversing a program by reading its MSIL code, but it also opens the door to an entirely different level of reverse-engineering approaches. There are .NET decompilers that can accurately recover a source-code-level representation of most .NET programs. The resulting code is highly readable, both because of the original symbol names that are preserved throughout the program, but also because of the highly detailed information that resides in the binary. This information can be used by decompilers to reconstruct both the flow and logic of the program and detailed information regarding its objects and data types. Figure 12.1 demonstrates a simple C# function and what it looks like after decompilation with the Salamander decompiler. Notice how pretty much every important detail regarding the source code is preserved in the decompiled version (local variable names are gone, but Salamander cleverly names them i and j).

Because of the high level of transparency offered by .NET programs, the concept of obfuscation of .NET binaries is very common and is far more popular than it is with native IA-32 binaries. In fact, Microsoft even ships an obfuscator with its .NET development platform, Visual Studio .NET. As Figure 12.1 demonstrates, if you ship your .NET product without any form of obfuscation, you might as well ship your source code along with your executable binaries.

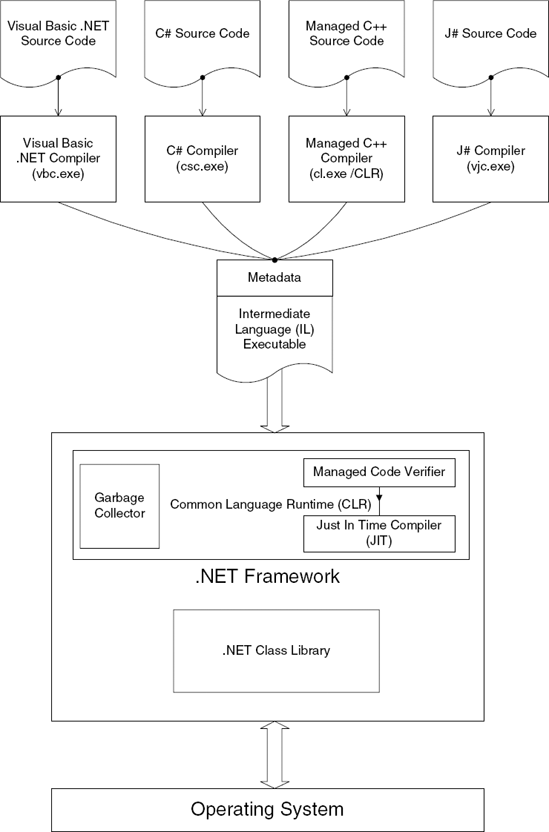

Unlike native machine code programs, .NET programs require a special environment in which they can be executed. This environment, which is called the .NET Framework, acts as a sort of intermediary between .NET programs and the rest of the world. The .NET Framework is basically the software execution environment in which all .NET programs run, and it consists of two primary components: the common language runtime (CLR) and the .NET class library. The CLR is the environment that loads and verifies .NET assemblies and is essentially a virtual machine inside which .NET programs are safely executed. The class library is what .NET programs use in order to communicate with the outside world. It is a class hierarchy that offers all kinds of services such as user-interface services, networking, file I/O, string management, and so on. Figure 12.2 illustrates the connection between the various components that together make up the .NET platform.

A .NET binary module is referred to as an assembly. Assemblies contain a combination of IL code and associated metadata. Metadata is a special data block that stores data type information describing the various objects used in the assembly, as well as the accurate definition of any object in the program (including local variables, method parameters, and so on). Assemblies are executed by the common language runtime, which loads the metadata into memory and compiles the IL code into native code using a just-in-time compiler.

Managed code is any code that is verified by the CLR in runtime for security, type safety, and memory usage. Managed code consists of the two basic .NET elements: MSIL code and metadata. This combination of MSIL code and metadata is what allows the CLR to actually execute managed code. At any given moment, the CLR is aware of the data types that the program is dealing with. For example, in conventional compiled languages such as C and C++ data structures are accessed by loading a pointer into memory and calculating the specific offset that needs to be accessed. The processor has no idea what this data structure represents and whether the actual address being accessed is valid or not.

While running managed code the CLR is fully aware of almost every data type in the program. The metadata contains information about class definitions, methods and the parameters they receive, and the types of every local variable in each method. This information allows the CLR to validate operations performed by the IL code and verify that they are legal. For example, when an assembly that contains managed code accesses an array item, the CLR can easily check the size of the array and simply raise an exception if the index is out of bounds.

.NET is not tied to any specific language (other than IL), and compilers have been written to support numerous programming languages. The following are the most popular programming languages used in the .NET environment.

C# C Sharp is the .NET programming language in the sense that it was designed from the ground up as the "native" .NET language. It has a syntax that is similar to that of C++, but is functionally more similar to Java than to C++. Both C# and Java are object oriented, allowing only a single level of inheritance. Both languages are type safe, meaning that they do not allow any misuse of data types (such as unsafe typecasting, and so on). Additionally, both languages work with a garbage collector and don't support explicit deletion of objects (in fact, no .NET language supports explicit deletion of object—they are all based on garbage collection).

Managed C++ Managed C++ is an extension to Microsoft's C/C++ compiler (

cl.exe), which can produce a managed IL executable from C++ code.Visual Basic .NET Microsoft has created a Visual Basic compiler for .NET, which means that they've essentially eliminated the old Visual Basic virtual machine (VBVM) component, which was the runtime component in which all Visual Basic programs executed in previous versions of the platform. Visual Basic .NET programs now run using the CLR, which means that essentially at this point Visual Basic executables are identical to C# and Managed C++ executables: They all consist of managed IL code and metadata.

J# JSharp is simply an implementation of Java for .NET. Microsoft provides a Java-compatible compiler for .NET which produces IL executables instead of Java bytecode. The idea is obviously to allow developers to easily port their Java programs to .NET.

One remarkable thing about .NET and all of these programming languages is their ability to easily interoperate. Because of the presence of metadata that accurately describes an executable, programs can interoperate at the object level regardless of the programming language they are created in. It is possible for one program to seamlessly inherit a class from another program even if one was written in C# and the other in Visual Basic .NET, for instance.

The Common Type System (CTS) governs the organization of data types in .NET programs. There are two fundamental data types: values and references. Values are data types that represent actual data, while reference types represent a reference to the actual data, much like the conventional notion of pointers. Values are typically allocated on the stack or inside some other object, while with references the actual objects are typically allocated in a heap block, which is freed automatically by the garbage collector (granted, this explanation is somewhat simplistic, but it'll do for now).

The typical use for value data types is for built-in data types such as integers, but developers can also define their own user-defined value types, which are moved around by value. This is generally only recommended for smaller data types, because the data is duplicated when passed to other methods, and so on. Larger data types use reference types, because with reference types only the reference to the object is duplicated—not the actual data.

Finally, unlike values, reference types are self-describing, which means that a reference contains information on the exact object type being referenced. This is different from value types, which don't carry any identification information.

One interesting thing about the CTS is the concept of boxing and unboxing. Boxing is the process of converting a value type data structure into a reference type object. Internally, this is implemented by duplicating the object in question and producing a reference to that duplicated object. The idea is that this boxed object can be used with any method that expects a generic object reference as input. Remember that reference types carry type identification information with them, so by taking an object reference type as input, a method can actually check the object's type in runtime. This is not possible with a value type. Unboxing is simply the reverse process, which converts the object back to a value type. This is needed in case the object is modified while it is in object form—because boxing duplicates the object, any changes made to the boxed object would not reflect on the original value type unless it was explicitly unboxed.

As described earlier, .NET executables are rarely shipped as native executables.[2] Instead, .NET executables are distributed in an intermediate form called Common Intermediate Language (CIL) or Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL), but we'll just call it IL for short. .NET programs essentially have two compilation stages: First a program is compiled from its original source code to IL code, and during execution the IL code is recompiled into native code by the just-in-time compiler. The following sections describe some basic low-level .NET concepts such as the evaluation stack and the activation record, and introduce the IL and its most important instructions. Finally, I will present a few IL code samples and analyze them.

The evaluation stack is used for managing state information in .NET programs. It is used by IL code in a way that is similar to how IA-32 instructions use registers—for storing immediate information such as the input and output data for instructions. Probably the most important thing to realize about the evaluation stack is that it doesn't really exist! Because IL code is never interpreted in runtime and is always compiled into native code before being executed, the evaluation stack only exists during the JIT process. It has no meaning during runtime.

Unlike the IA-32 stacks you've gotten so used to, the evaluation stack isn't made up of 32-bit entries, or any other fixed-size entries. A single entry in the stack can contain any data type, including whole data structures. Many instructions in the IL instruction set are polymorphic, meaning that they can take different data types and properly deal with a variety of types. This means that arithmetic instructions, for instance, can operate correctly on either floating-point or integer operands. There is no need to explicitly tell instructions which data types to expect—the JIT will perform the necessary data-flow analysis and determine the data types of the operands passed to each instruction.

To properly grasp the philosophy of IL, you must get used to the idea that the CLR is a stack machine, meaning that IL instructions use the evaluation stack just like IA-32 assembly language instruction use registers. Practically every instruction either pops a value off of the stack or it pushes some kind of value back onto it—that's how IL instructions access their operands.

Activation records are data elements that represent the state of the currently running function, much like a stack frame in native programs. An activation record contains the parameters passed to the current function along with all the local variables in that function. For each function call a new activation record is allocated and initialized. In most cases, the CLR allocates activation records on the stack, which means that they are essentially the same thing as the stack frames you've worked with in native assembly language code. The IL instruction set includes special instructions that access the current activation record for both function parameters and local variables (see below). Activation records are automatically allocated by the IL instruction call.

Let's go over the most common and interesting IL instructions, just to get an idea of the language and what it looks like. Table 12.1 provides descriptions for some of the most popular instructions in the IL instruction set. Note that the instruction set contains over 200 instructions and that this is nowhere near a complete reference. If you're looking for detailed information on the individual instructions please refer to the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) specifications document, partition III [ECMA].

Table 12.1. A summary of the most common IL instructions.

Let's take a look at a few trivial IL code sequences, just to get a feel for the language. Keep in mind that there is rarely a need to examine raw, nonobfuscated IL code in this manner—a decompiler would provide a much more pleasing output. I'm doing this for educational purposes only. The only situation in which you'll need to read raw IL code is when a program is obfuscated and cannot be properly decompiled.

The routine below was produced by ILdasm, which is the IL Disassembler included in the .NET Framework SDK. The original routine was written in C#, though it hardly matters. Other .NET programming languages would usually produce identical or very similar code. Let's start with Listing 12.1.

Example 12.1. A sample IL program generated from a .NET executable by the ILdasm disassembler program.

.method public hidebysig static void Main() cil managed

{

.entrypoint

.maxstack 2

.locals init (int32 V_0)

IL_0000: ldc.i4.1IL_0001: stloc.0 IL_0002: br.s IL_000e IL_0004: ldloc.0 IL_0005: call void [mscorlib]System.Console::WriteLine(int32) IL_000a: ldloc.0 IL_000b: ldc.i4.1 IL_000c: add IL_000d: stloc.0 IL_000e: ldloc.0 IL_000f: ldc.i4.s 10 IL_0011: ble.s IL_0004 IL_0013: ret } // end of method App::Main

Listing 12.1 starts with a few basic definitions regarding the method listed. The method is specified as .entrypoint, which means that it is the first code executed when the program is launched. The .maxstack statement specifies the maximum number of items that this routine loads into the evaluation stack. Note that the specific item size is not important here—don't assume 32 bits or anything of the sort; it is the number of individual items, regardless of their size. The following line defines the method's local variables. This function only has a single int32 local variable, named V_0. Variable names are one thing that is usually eliminated by the compiler (depending on the specific compiler).

The routine starts with the ldc instruction, which loads the constant 1 onto the evaluation stack. The next instruction, stloc.0, pops the value from the top of the stack into local variable number 0 (called V_0), which is the first (and only) local variable in the program. So, we've effectively just loaded the value 1 into our local variable V_0. Notice how this sequence is even longer than it would have been in native IA-32 code; we need two instructions to load a constant into local variable. The CLR is a stack machine—everything goes through the evaluation stack.

The procedure proceeds to jump unconditionally to address IL_000e. The target instruction is specified using a relative address from the end of the current one. The specific branch instruction used here is br.s, which is the short version, meaning that the relative address is specified using a single byte. If the distance between the current instruction and the target instruction was larger than 255 bytes, the compiler would have used the regular br instruction, which uses an int32 to specify the relative jump address. This short form is employed to make the code as compact as possible.

The code at IL_000e starts out by loading two values onto the evaluation stack: the value of local variable 0, which was just initialized earlier to 1, and the constant 10. Then these two values are compared using the ble.s instruction. This is a "branch if lower or equal" instruction that does both the comparing and the actual jumping, unlike IA-32 code, which requires two instructions, one for comparison and another for the actual branching. The CLR compares the second value on the stack with the one currently at the top, so that "lower or equal" means that the branch will be taken if the value at local variable '0' is lower than or equal to 10. Since you happen to know that the local variable has just been loaded with the value 1, you know for certain that this branch is going to be taken—at least on the first time this code is executed. Finally, it is important to remember that in order for ble.s to evaluate the arguments passed to it, they must be popped out of the stack. This is true for pretty much every instruction in IL that takes arguments through the evaluation stack—those arguments are no longer going to be in the stack when the instruction completes.

Assuming that the branch is taken, execution proceeds at IL_0004, where the routine calls WriteLine, which is a part of the .NET class library. WriteLine displays a line of text in the console window of console-mode applications. The function is receiving a single parameter, which is the value of our local variable. As you would expect, the parameter is passed using the evaluation stack. One thing that's worth mentioning is that the code is passing an integer to this function, which prints text. If you look at the line from where this call is made, you will see the following: void [mscorlib]System.Console::WriteLine(int32). This is the prototype of the specific function being called. Notice that the parameter it takes is an int32, not a string as you would expect. Like many other functions in the class library, WriteLine is overloaded and has quite a few different versions that can take strings, integers, floats, and so on. In this particular case, the version being called is the int32 version—just as in C++, the automated selection of the correct overloaded version was done by the compiler.

After calling WriteLine, the routine again loads two values onto the stack: the local variable and the constant 1. This is followed by an invocation of the add instruction, which adds two values from the evaluation stack and writes the result back into it. So, the code is adding 1 to the local variable and saving the result back into it (in line IL_000d). This brings you back to IL_000e, which is where you left off before when you started looking at this loop.

Clearly, this is a very simple routine. All it does is loop between IL_0004 and IL_0011 and print the current value of the counter. It will stop once the counter value is greater than 10 (remember the conditional branch from lines IL_000e through IL_0011). Not very challenging, but it certainly demonstrates a little bit about how IL works.

Before proceeding to examine obfuscated IL code, let us proceed to another, slightly more complicated sample. This one (like pretty much every .NET program you'll ever meet) actually uses a few objects, so it's a more relevant example of what a real program might look like. Let's start by disassembling this program's Main entry point, printed in Listing 12.2.

Example 12.2. A simple program that instantiates and fills a linked list object.

.method public hidebysig static void Main() cil managed

{

.entrypoint

.maxstack 2

.locals init (class LinkedList V_0,

int32 V_1,

class StringItem V_2)

IL_0000: newobj instance void LinkedList::.ctor()

IL_0005: stloc.0

IL_0006: ldc.i4.1

IL_0007: stloc.1

IL_0008: br.s IL_002b

IL_000a: ldstr "item"

IL_000f: ldloc.1

IL_0010: box [mscorlib]System.Int32

IL_0015: call string [mscorlib]System.String::Concat(

object, object)

IL_001a: newobj instance void StringItem::.ctor(string)

IL_001f: stloc.2

IL_0020: ldloc.0

IL_0021: ldloc.2

IL_0022: callvirt instance void LinkedList::AddItem(class ListItem)

IL_0027: ldloc.1

IL_0028: ldc.i4.1

IL_0029: add

IL_002a: stloc.1

IL_002b: ldloc.1

IL_002c: ldc.i4.s 10

IL_002e: ble.s IL_000a

IL_0030: ldloc.0

IL_0031: callvirt instance void LinkedList::Dump()

IL_0036: ret

} // end of method App::MainAs expected, this routine also starts with a definition of local variables. Here there are three local variables, one integer, and two object types, LinkedList and StringItem. The first thing this method does is it instantiates an object of type LinkedList, and calls its constructor through the newobj instruction (notice that the method name .ctor is a reserved name for constructors). It then loads the reference to this newly created object into the first local variable, V_0, which is of course defined as a LinkedList object. This is an excellent example of managed code functionality. Because the local variable's data type is explicitly defined, and because the runtime is aware of the data type of every element on the stack, the runtime can verify that the variable is being assigned a compatible data type. If there is an incompatibility the runtime will throw an exception.

The next code sequence at line IL_0006 loads 1 into V_1 (which is an integer) through the evaluation stack and proceeds to jump to IL_002b. At this point the method loads two values onto the stack, 10 and the value of V_1, and jumps back to IL_000a. This sequence is very similar to the one in Listing 12.1, and is simply a posttested loop. Apparently V_1 is the counter, and it can go up to 10. Once it is above 10 the loop terminates.

The sequence at IL_000a is the beginning of the loop's body. Here the method loads the string "item" into the stack, and then the value of V_1. The value of V_1 is then boxed, which means that the runtime constructs an object that contains a copy of V_1 and pushes a reference to that object into the stack. An object has the advantage of having accurate type identification information associated with it, so that the method that receives it can easily determine precisely which type it is. This identification can be performed using the IL instruction isinst.

After boxing V_1, you wind up with two values on the stack: the string item and a reference to the boxed copy of V_1. These two values are then passed to class library method string [mscorlib]System.String::Concat(object, object), which takes two items and constructs a single string out of them. If both objects are strings, the method will simply concatenate the two. Otherwise the function will convert both objects to strings (assuming that they're both nonstrings) and then perform the concatenation. In this particular case, there is one string and one Int32, so the function will convert the Int32 to a string and then proceed to concatenate the two strings. The resulting string (which is placed at the top of the stack when Concat returns) should look something like "itemX", where X is the value of V_1.

After constructing the string, the method allocates an instance of the object StringItem, and calls its constructor (this is all done by the newobj instruction). If you look at the prototype for the StringItem constructor (which is displayed right in that same line), you can see that it takes a single parameter of type string. Because the return value from Concat was placed at the top of the evaluation stack, there is no need for any effort here—the string is already on the stack, and it is going to be passed on to the constructor. Once the constructor returns newobj places a reference to the newly constructed object at the top of the stack, and the next line pops that reference from the stack into V_2, which was originally defined as a StringItem.

The next sequence loads the values of V_0 and V_2 into the stack and calls LinkedList::AddItem(class ListItem). The use of the callvirt instruction indicates that this is a virtual method, which means that the specific method will be determined in runtime, depending on the specific type of the object on which the method is invoked. The first parameter being passed to this function is V_2, which is the StringItem variable. This is the object instance for the method that's about to be called. The second parameter, V_0, is the ListItem parameter the method takes as input. Passing an object instance as the first parameter when calling a class member is a standard practice in object-oriented languages. If you're wondering about the implementation of the AddItem member, I'll discuss that later, but first, let's finish investigating the current method.

The sequence at IL_0027 is one that you've seen before: It essentially increments V_1 by one and stores the result back into V_1. After that you reach the end of the loop, which you've already analyzed. Once the conditional jump is not taken (once V_1 is greater than 10), the code calls LinkedList::Dump() on our LinkedList object from V_0.

Let's summarize what you've seen so far in the program's entry point, before I start analyzing the individual objects and methods. You have a program that instantiates a LinkedList object, and loops 10 times through a sequence that constructs the string "ItemX, where X is the current value of our iterator. This string then is passed to the constructor of a StringItem object. That StringItem object is passed to the LinkedList object using the AddItem member. This is clearly the process of constructing a linked list item that contains your string and then adding that item to the main linked list object. Once the loop is completed the Dump method in the LinkedList object is called, which, you can only assume, dumps the entire linked list in some way.

At this point you can take a quick look at the other objects that are defined in this program and examine their implementations. Let's start with the ListItem class, whose entire definition is given in Listing 12.3.

Example 12.3. Declaration of the ListItem class.

.class private auto ansi beforefieldinit ListItem

extends [mscorlib]System.Object

{ .field public class ListItem Prev

.field public class ListItem Next

.method public hidebysig newslot virtual

instance void Dump() cil managed

{ .maxstack 0

IL_0000: ret

} // end of method ListItem::Dump

.method public hidebysig specialname rtspecialname

instance void .ctor() cil managed

{ .maxstack 1

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: call instance void [mscorlib]System.Object::.ctor()

IL_0006: ret

} // end of method ListItem::.ctor

} // end of class ListItemThere's not a whole lot to the ListItem class. It has two fields, Prev and Next, which are both defined as ListItem references. This is obviously a classic linked-list structure. Other than the two data fields, the class doesn't really have much code. You have the Dump virtual method, which contains an empty implementation, and you have the standard constructor, .ctor, which is automatically created by the compiler.

We now proceed to the declaration of LinkedList in Listing 12.4, which is apparently the root object from where the linked list is managed.

Example 12.4. Declaration of LinkedList object.

.class private auto ansi beforefieldinit LinkedList

extends [mscorlib]System.Object

{ .field private class ListItem ListHead

.method public hidebysig instance void

AddItem(class ListItem NewItem) cil managed

{

.maxstack 2

IL_0000: ldarg.1IL_0001: ldarg.0

IL_0002: ldfld class ListItem LinkedList::ListHead

IL_0007: stfld class ListItem ListItem::Next

IL_000c: ldarg.0

IL_000d: ldfld class ListItem LinkedList::ListHead

IL_0012: brfalse.s IL_0020

IL_0014: ldarg.0

IL_0015: ldfld class ListItem LinkedList::ListHead

IL_001a: ldarg.1

IL_001b: stfld class ListItem ListItem::Prev

IL_0020: ldarg.0

IL_0021: ldarg.1

IL_0022: stfld class ListItem LinkedList::ListHead

IL_0027: ret

} // end of method LinkedList::AddItem

.method public hidebysig instance void

Dump() cil managed

{

.maxstack 1

.locals init (class ListItem V_0)

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld class ListItem LinkedList::ListHead

IL_0006: stloc.0

IL_0007: br.s IL_0016

IL_0009: ldloc.0

IL_000a: callvirt instance void ListItem::Dump()

IL_000f: ldloc.0

IL_0010: ldfld class ListItem ListItem::Next

IL_0015: stloc.0

IL_0016: ldloc.0

IL_0017: brtrue.s IL_0009

IL_0019: ret

} // end of method LinkedList::Dump

.method public hidebysig specialname rtspecialname

instance void .ctor() cil managed

{

.maxstack 1

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: call instance void [mscorlib]System.Object::.ctor()

IL_0006: ret

} // end of method LinkedList::.ctor

} // end of class LinkedListThe LinkedList object contains a ListHead member of type ListItem (from Listing 12.3), and two methods (not counting the constructor): AddItem and Dump. Let's begin with AddItem. This method starts with an interesting sequence where the NewItem parameter is pushed into the stack, followed by the first parameter, which is the this reference for the LinkedList object. The next line uses the ldfld instruction to read from a field in the LinkedList data structure (the specific instance being read is the one whose reference is currently at the top of the stack—the this object). The field being accessed is ListHead; its contents are placed at the top of the stack (as usual, the LinkedList object reference is popped out once the instruction is done with it).

You proceed to IL_0007, where stfld is invoked to write into a field in the ListItem instance whose reference is currently the second item in the stack (the NewItem pushed at IL_0000). The field being accessed is the Next field, and the value being written is the one currently at the top of the stack, the value that was just read from ListHead. You proceed to IL_000c, where the ListHead member is again loaded into the stack, and is tested for a valid value. This is done using the brfalse instruction, which branches to the specified address if the value currently at the top of the stack is null or false.

Assuming the branch is not taken, execution flows into IL_0014, where stfld is invoked again, this time to initialize the Prev member of the ListHead item to the value of the NewItem parameter. Clearly the idea here is to push the item that's currently at the head of the list and to make NewItem the new head of the list. This is why the current list head's Prev field is set to point to the item currently being added. These are all classic linked list sequences. The final operation performed by this method is to initialize the ListHead field with the value of the NewItem parameter. This is done at IL_0020, which is the position to which the brfalse from earlier jumps to when ListHead is null. Again, a classic linked list item-adding sequence. The new items are simply placed at the head of the list, and the Prev and Next fields of the current head of the list and the item being added are updated to reflect the new order of the items.

The next method you will look at is Dump, which is listed right below the AddItem method in Listing 12.4. The method starts out by loading the current value of ListHead into the V_0 local variable, which is, of course, defined as a ListItem. There is then an unconditional branch to IL_0016 (you've seen these more than once before; they almost always indicate the head of a posttested loop construct). The code at IL_0016 uses the brtrue instruction to check that V_0 is non-null, and jumps to the beginning of the loop as long as that's the case.

The loop's body is quite simple. It calls the Dump virtual method for each ListItem (this method is discussed later), and then loads the Next field from the current V_0 back into V_0. You can only assume that this sequence originated in something like CurrentItem = CurrentItem.Next in the original source code. Basically, what you're doing here is going over the entire list and "dumping" each item in it. You don't really know what dumping actually means in this context yet. Because the Dump method in ListItem is declared as a virtual method, the actual method that is executed here is unknown—it depends on the specific object type.

Let's conclude this example by taking a quick look at Listing 12.5, at the declaration of the StringItem class, which inherits from the ListItem class.

Example 12.5. Declaration of the StringItem class.

.class private auto ansi beforefieldinit StringItem

extends ListItem

{

.field private string ItemData

.method public hidebysig specialname rtspecialname

instance void .ctor(string InitializeString) cil managed

{

.maxstack 2

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: call instance void ListItem::.ctor()

IL_0006: ldarg.0

IL_0007: ldarg.1

IL_0008: stfld string StringItem::ItemData

IL_000d: ret

} // end of method StringItem::.ctor

.method public hidebysig virtual instance void

Dump() cil managed

{ .maxstack 1

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld string StringItem::ItemData

IL_0006: call void [mscorlib]System.Console::Write(string)

IL_000b: ret

} // end of method StringItem::Dump

} // end of class StringItemThe StringItem class is an extension of the ListItem class and contains a single field: ItemData, which is a string data type. The constructor for this class takes a single string parameter and stores it in the ItemData field. The Dump method simply displays the contents of ItemData by calling System.Console::Write. You could theoretically have multiple classes that inherit from ListItem, each with its own Dump method that is specifically designed to dump the data for that particular type of item.

As you've just witnessed, reversing IL code is far easier than reversing native assembly language such as IA-32. There are far less redundant details such as flags and registers, and far more relevant details such as class definitions, local variable declarations, and accurate data type information. This means that it can be exceedingly easy to decompile IL code back into a high-level language code. In fact, there is rarely a reason to actually sit down and read IL code as we did in the previous section, unless that code is so badly obfuscated that decompilers can't produce a reasonably readable high-level language representation of it.

Let's try and decompile an IL method and see what kind of output we end up with. Remember the AddItem method from Listing 12.4? Let's decompile this method using Spices.Net (9Rays.Net, www.9rays.net) and see what it looks like.

public virtual void AddItem(ListItem NewItem)

{

NewItem.Next = ListHead;

if (ListHead != null)

{

ListHead.Prev = NewItem;

}

ListHead = NewItem;

}This listing is distinctly more readable than the IL code from Listing 12.4. Objects and their fields are properly resolved, and the conditional statement is properly represented. Additionally, references in the IL code to the this object have been eliminated—they're just not required for properly deciphering this routine. The remarkable thing about .NET decompilation is that you don't even have to reconstruct the program back to the original language in which it was written. In some cases, you don't really know which language was used for writing the program. Most decompilers such as Spices.Net let you decompile code into any language you choose—it has nothing to do with the original language in which the program was written.

The high quality of decompilation available for nonobfuscated programs means that reverse engineering of such .NET programs basically boils down to reading the high-level language code and trying to figure out what the program does. This process is typically referred to as program comprehension, and ranges from being trivial to being incredibly complex, depending on the size of the program and the amount of information being extracted from it.

Because of the inherent vulnerability of .NET executables, the concept of obfuscating .NET executables to prevent quick decompilation of the program is very common. This is very different from native executables where processor architectures such as IA-32 inherently provide a decent amount of protection because it is difficult to read the assembly language code. IL code is highly detailed and can be easily decompiled into a very readable high-level language representation. Before discussing the specific obfuscators, let's take a brief look at the common strategies for obfuscating .NET executables.

Because .NET executables contain full-blown, human-readable symbol names for method parameters, class names, field names, and method names, these strings must be eliminated from the executable if you're going to try to prevent people from reverse engineering it. Actual elimination of these strings is not possible, because they are needed for identifying elements within the program. Instead, these symbols are renamed and are given cryptic, meaningless names instead of their original names. Something like ListItem can become something like d, or even xc1f1238cfa10db08. This can never prevent anyone from reverse engineering a program, but it'll certainly make life more difficult for those who try.

I have already discussed control flow obfuscation in Chapter 10; it is the concept of modifying a program's control flow structure in order to make it less readable. In .NET executables control flow obfuscation is aimed primarily at breaking decompilers and preventing them from producing usable output for the obfuscated program. This can be quite easy because decompilers expect programs to contain sensible control flow graphs that can be easily translated back into high-level language control flow constructs such as loops and conditional statements.

One feature that many popular obfuscators support, including Dotfuscator, XenoCode, and the Spices.Net obfuscator is to try and completely prevent disassembly of the obfuscated executable. Depending on the specific program that's used for opening such an executable, it might crash or display a special error message, such as the one in Figure 12.3, displayed by ILDasm 1.1.

There are two general strategies for preventing disassembly and decompilation in .NET assemblies. When aiming specifically at disrupting ILDasm, there are some undocumented metadata entries that are checked by ILDasm when an assembly is loaded. These entries are modified by obfuscators in a way that makes ILDasm display the copyright message from Figure 12.3.

Another approach is to simply "corrupt" the assembly's metadata in some way that would not prevent the CLR from running it, but would break programs that load the assembly into memory and scan its metadata. Corrupting the metadata can be done by inserting bogus references to nonexistent strings, fields, or methods. Some programs don't properly deal with such broken links and simply crash when loading the assembly. This is not a pretty approach for obfuscation, and I would generally recommend against it, especially considering how easy it is for developers of decompilers or disassemblers to work around these kinds of tricks.

The following sections demonstrate some of the effects caused by the popular .NET obfuscators, and attempt to evaluate their effectiveness against reverse engineering. For those looking for an accurate measurement of the impact of obfuscators on the complexity of the reverse-engineering process, there is currently no such measurement. Traditional software metrics approaches such as the McCabe software complexity metric [McCabe] don't tell the whole story because they only deal with the structural complexity of the program, while completely ignoring the representation of the program. In fact, most of the .NET obfuscators I have tested would probably have no effect on something like the McCabe metric, because they primarily alter the representation of the program, not its structure. Sure, control-flow obfuscation techniques can increase the complexity of a program's control-flow graph somewhat, but that's really just one part of the picture.

Let's examine the impact of some of the popular .NET obfuscators on the linked-list example and try to determine how effective these programs are against decompilation and against manual analysis of the IL code.

As a first test case, I have taken the linked-list sample you examined earlier and ran it through the XenoCode 2005 (XenoCode Corporation, www.xenocode.com) obfuscator, with the string renaming and control flow obfuscation features enabled. The "Suppress Microsoft IL Disassembler" feature was enabled, which prevented ILDasm from disassembling the code, but it was still possible to disassemble the code using other tools such as Decompiler.NET (Jungle Creatures Inc., www.junglecreature.com) or Spices.Net. Note that both of these products support both IL disassembly and full-blown decompilation into high-level languages. Listing 12.6 shows the Spices.Net IL disassembly for the AddItem function from Listing 12.4.

Example 12.6. IL disassembly of an obfuscated version of the AddItem function from Listing 12.4.

instance void x5921718e79c67372(class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

xc1f1238cfa10db08) cil managed

{

// Code size: 46 bytes

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ldarg.1

IL_0001: ldarg.0

IL_0002: ldfld class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

x5fc7cea805f4af85::xb19b6eb1af8dda00

IL_0007: br.s IL_0017

IL_0009: ldarg.0

IL_000a: ldfld class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

x5fc7cea805f4af85::xb19b6eb1af8dda00

IL_000f: ldarg.1

IL_0010: stfld class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

xcc70d25cd5aa3d56::xd3669c4cce512327

IL_0015: br.s IL_0026

IL_0017: stfld class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

xcc70d25cd5aa3d56::xbc13914359462815

IL_001c: ldarg.0

IL_001d: ldfld class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

x5fc7cea805f4af85::xb19b6eb1af8dda00

IL_0022: brfalse.s IL_0026

IL_0024: br.s IL_0009

IL_0026: ldarg.0

IL_0027: ldarg.1

IL_0028: stfld class xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

x5fc7cea805f4af85::xb19b6eb1af8dda00

IL_002d: ret

}//end of method x5fc7cea805f4af85::x5921718e79c67372The first thing to notice about Listing 12.6 is that all the symbols have been renamed. Instead of a bunch of nice-looking names for classes, methods, and fields you now have longish, random-looking combinations of digits and letters. This is highly annoying, and it might make sense for an attacker to rename these symbols into short names such as a, b, and so on. They still won't have any meaning, but it'd be much easier to make the connection between the individual symbols.

Other than the cryptic symbol names, the control flow statements in the method have also been obfuscated. Essentially what this means is that code segments have been moved around using unconditional branches. For example, the unconditional branch at IL_0007 is simply the original if statement, except that it has been relocated to a later point in the function. The code that follows that instruction (which is reached from the unconditional branch at IL_0024) is the actual body of the if statement. The problem with these kinds of transformations is that they hardly even create a mere inconvenience to an experienced reverser that's working at the IL level. They are actually more effective against decompilers, which might get confused and convert them to goto statements. This happens when the decompiler fails to create a correct control flow graph for the method. For more information on the process of decompilation and on control flow graphs, please refer to Chapter 13.

Let's see what happens when I feed the obfuscated code from Listing 12.6 into the Spices.Net decompiler plug-in. The method below is a decompiled version of that obfuscated IL method in C#.

public virtual void x5921718e79c67372(xcc70d25cd5aa3d56

xc1f1238cfa10db08)

{

xc1f1238cfa10db08.xbc13914359462815 = xb19b6eb1af8dda00;

if (xb19b6eb1af8dda00 != null)

{

xb19b6eb1af8dda00.xd3669c4cce512327 = xc1f1238cfa10db08;

}

xb19b6eb1af8dda00 = xc1f1238cfa10db08;

}Interestingly, Spices is largely unimpressed by the obfuscator and properly resolves the function's control flow obfuscation. Sure, the renamed symbols make this function far less pleasant to analyze, but it is certainly possible. One thing that's important is the long and random-looking symbol names employed by XenoCode. I find this approach to be particularly effective, because it takes an effort to find cross-references. It's not easy to go over these long strings and look for differences.

DotFuscator (PreEmptive Solutions, www.preemptive.com) is another obfuscator that offers similar functionality to XenoCode. It supports symbol renaming, control flow obfuscation and can block certain tools from dumping and disassembling obfuscated executables. DotFuscator supports aggressive symbol renaming features that eliminate namespaces and use overloaded methods to add further confusion (this is their Overload-Induction feature). Consider for example a class that has three separate methods: one that takes no parameters, one that takes an integer, and another that takes a Boolean. The beauty of Overload-Induction is that all three methods are likely to receive the same name, and the specific method will be selected by the number and type of parameters passed to it. This is highly confusing to reversers because it becomes difficult to differentiate between the individual methods. Listing 12.7 shows an IL listing for our LinkedList::Dump method from Listing 12.7 shows an IL listing for our LinkedList::Dump method from Listing 12.4.

Example 12.7. DotFuscated version of the LinkedList::Dump method from Listing 12.4.

instance void a() cil managed

{

// Code size: 36 bytes

.maxstack 1

.locals init(class d V_0)

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld class d b::a

IL_0006: stloc.0

IL_0007: br.s IL_0009

IL_0009: ldloc.0

IL_000a: brtrue.s IL_0011

IL_000c: br IL_0023

IL_0011: ldloc.0

IL_0012: callvirt instance void d::a()

IL_0017: ldloc.0

IL_0018: ldfld class d d::b

IL_001d: stloc.0

IL_001e: br IL_0009

IL_0023: ret

}//end of method b::aThe first distinctive feature about DotFuscator is those short, single-letter names used for symbols. This can get extremely annoying, especially considering that every class has at least one method called a. If you try to follow the control flow instructions in Listing 12.7, you'll notice that they barely resemble the original flow of LinkedList::Dump—DotFuscator can perform some fairly aggressive control flow obfuscation, depending on user settings.

First of all, the loop's condition has been moved up to the beginning of the loop, and an unconditional jump back to the beginning of the loop has been added at the end (at IL_001e). This structure in itself is essentially nothing but a pretested loop, but there are additional elements here that are put in place to confuse decompilers. If you look at the loop condition itself, it has been rearranged in an unusual way: If the brtrue instruction is satisfied, it skips an unconditional jump instruction and jumps into the loop's body. If it's not, the next instruction down is an unconditional jump that skips the loop's body and goes to the end of the method.

Before the loop's condition there is an unusual sequence at IL_0007 that uses an unconditional branch instruction to simply skip to the next instruction at IL_0009. IL_0009 is the first instruction in the loop and the unconditional branch instruction at the end of the loop jumps back to this instruction. It looks like the idea with that unconditional branch at IL_0007 is to complicate the control flow graph and have two unconditional branches point to the same place, which is likely to throw off the control flow analysis algorithms in some decompilers.

Let's run this method through a decompiler and see whether these aggressive control flow obfuscation techniques impact the output from decompilers. The following code is the output I got from the Spices.Net decompiler for the routine from Listing 12.7:

public virtual void a()

{

d d = a;

d.a();

d = d.b;

while (d == null)

{

return;

}

}Spices.Net is completely confused by the unusual control flow constructs of this routine and generates incorrect code. It fails to properly identify the loop's body and actually places the return statement inside the loop, even though it is executed after the loop. The d.a(); and d = d.b; statements are placed before the loop even though they are essentially the loop's body. Finally, the loop's condition is reversed: The loop is supposed to keep running while d is not null, not the other way around.

Different decompilers employ different control flow analysis algorithms, and they generally react differently to these types of control flow obfuscations. Let's feed the same DotFuscated code from Listing 12.7 into another decompiler, Decompiler.Net and see how it reacts to the DotFuscator's control flow obfuscation.

public void a ()

{

for (d theD = this.a; (theD != null); theD = theD.b)

{

theD.a ();

}

}No problems here—Decompiler.Net does a good job and the obfuscated control flow structure of this routine seems to have no impact on its output. The fact is that control flow obfuscations have a certain cat-and-mouse nature to them where decompiler writers can always go back and add special heuristics that can properly deal with the various distorted control flow structures encountered in obfuscated methods. It is important to keep this in mind and to not overestimate the impact these techniques have on the overall readability of the program. It is almost always going to be possible to correctly decompile control flow obfuscated code—after all the code always has to retain its original meaning in order for the program to execute properly.

If you go back to the subject of symbol renaming, notice how confusing this simple alphabetical symbol naming scheme can be. Your a method belongs to class b, and there are two references to a: one this.a reference and another theD.a method call. One is a field in class b, and the other is a method in class d. This is an excellent example of where symbol renaming can have quite an annoying effect for reversers.

While I'm dealing with symbol renaming, DotFuscator has another option that can cause additional annoyance to attackers trying to reverse obfuscated assemblies. It can rename symbols using invalid characters that cannot be properly displayed. This means that (depending on the tool that's used for viewing the code) it might not even be possible to distinguish one symbol name from the other and that in some cases these characters might prevent certain tools from opening the assembly. The following code snippet is our AddItem method obfuscated using DotFuscator with the Unprintable Symbol Names feature enabled. The following code was produced using Decompiler.Net:

public void á(áf A_0) { A_0.á_ = this.á; if (this.á!= null) { this.á.á= A_0; } this.á= A_0; }

As presented here, this function is pretty much impossible to decipher—it's very difficult to differentiate between the different symbols. Still, it clearly shouldn't be very difficult for a decompiler to overcome this problem—it would simply have to identify such symbol names and arbitrarily rename them to make the code more readable. The following sample demonstrates this solution on the same DotFuscated assembly that contains the unprintable names; it was produced by the Spices.Net decompiler, which appears to do this automatically.

public virtual void \u1700(\u1703 A_0)

{

A_0.\u1701 = \u1700;

if (\u1700 != null)

{

\u1700.\u1700 = A_0;

}

\u1700 = A_0;

}With Spices.Net automatically renaming those unreadable symbols, this method becomes more readable. This is true for many of the other, less aggressive renaming schemes as well. A decompiler can always just rename every symbol during the decompilation stage to make the code as readable as possible. For example, the repeated use of a, b, and c, as discussed earlier, could be replaced with unique names. The conclusion is that many of the transformations performed by obfuscators can be partially undone with the right automated tools. This is the biggest vulnerability of these tools: As long as it is possible to partially or fully undo the effects of their transformations, they become worthless. The challenge for developers of obfuscators is to create irreversible transformations.

The Remotesoft Obfuscator (Remotesoft, www.remotesoft.com) product is based on concepts similar to the other obfuscators I've discussed, with the difference that it also includes a Linker component, which can add another layer of security to obfuscated assemblies. The linker can join several assemblies into a single file. This feature is useful in several different cases, but it is interesting from the reverse-engineering perspective because it can provide an additional layer of protection against reverse engineering.

As I have demonstrated more than once throughout this book, in situations where very little information is available about a code snippet being analyzed, system calls can provide much needed information. In my Defender sample from Chapter 11, I demonstrated a special obfuscated operating system interface for native programs that made it very difficult to identify system calls, because these make it much easier to reverse programs. The same problem holds true for .NET executables as well: no matter how well an assembly might be obfuscated, it is still going to have highly informative calls to the System namespace that can reveal a lot about the code being examined.

The solution is to obfuscate the .NET class library and distribute the obfuscated version along with the obfuscated program. This way, when a System object is referenced, the names are all mangled, and it becomes quite difficult to determine the actual name of the system call.

One approach that can sometimes reveal such system classes even after they are renamed uses a hierarchical call graph view that shows how the various methods interact. Because the System class contains a large amount of code that is essentially isolated from the main program (it never makes calls into the main program, for instance), it becomes fairly easy to identify system branches and at least know that a certain class is part of the System namespace. There are several tools that can produce call graphs for .NET assemblies, including IDA Pro (which includes full IL disassembly support, by the way).

The Remotesoft Protector product is another obfuscation product that takes a somewhat different approach to prevent reverse engineering of .NET assemblies. Protector has two modes of operation. There is a platform-dependent mode where the IL code is actually precompiled into native IA-32 code, which completely eliminates the IL code from the distributable assembly. This offers a significant security advantage because as we know, reversing native IA-32 code is far more difficult than reversing IL code. The downside of this approach is that the assembly becomes platform-dependent and can only run on IA-32 systems.

Protector also supports a platform-independent mode that encrypts the IL code inside the executable instead of entirely eliminating it. In this mode the Protector encrypts IL instructions and hides them inside the executable. This is very similar to several packers and DRM products available for native programs (see Part III). The end result of this transformation is that it is not possible to directly load assemblies protected with this product into any .NET disassembler or decompiler. That's because the assembly's IL code is not readily available and is encrypted inside the assembly.

In the following two sections, I will discuss these two different protection techniques employed by Protector and try and evaluate the level of security they provide.

If you're willing to sacrifice portability, precompiling your .NET assemblies is undoubtedly the best way to prevent people from reverse engineering them. Native code is significantly less readable than IL code, and there isn't a single working decompiler currently available for IA-32 code. Even if there were, it is unlikely that they would produce code that's nearly as readable as the code produced by the average IL decompiler.

Before you rush out of this discussion feeling that precompiling .NET assemblies offers impregnable security for your code, here is one other point to keep in mind. Precompiled assemblies still retain their metadata—it is required in order for the CLR to successfully run them. This means that it might be theoretically possible for a specially crafted native code decompiler to actually take advantage of this metadata to improve the readability of the code. If such a decompiler was implemented, it might be able to produce highly readable output.

Beyond this concept of an advanced decompiler, you must remember that native code is not that difficult to reverse engineer—it can be done manually, all it takes is a little determination. The bottom line here is that if you are trying to protect very large amounts of code, precompiling your assemblies is likely to do the trick. On the other hand, if you have just one tiny method that contains your precious algorithm, even precompilation wouldn't prevent determined reversers from getting to it.

For those not willing to sacrifice portability for security, Protector offers another option that retains the platform-independence offered by the .NET platform. This mode encrypts the IL code and stores the encrypted code inside the assembly. In order for Protected assemblies to run in platform-independent mode, the Protector also includes a native redistributable DLL which is responsible for actually decrypting the IL methods and instructing the JIT to compile the decrypted methods in runtime. This means that encrypted binaries are not 100 percent platform-independent—you still need native decryption DLLs for each supported platform.

This approach of encrypting the IL code is certainly effective against casual attacks where a standard decompiler is used for decompiling the assembly (because the decompiler won't have access to the plaintext IL code), but not much more than that. The key that is used for encrypting the IL code is created by hashing certain sections of the assembly using the MD5 hashing algorithm. The code is then encrypted using the RC4 stream cipher with the result of the MD5 used as the encryption key.

This goes back to the same problem I discussed over and over again in Part III of this book. Encryption algorithms, no matter how powerful, can't provide any real security when the key is handed out to both legal recipients and attackers. Because the decryption key must be present in the distributed assembly, all an attacker must do in order to decrypt the original IL code is to locate that key. This is security by obscurity, and it is never a good thing.

One of the major weaknesses of this approach is that it is highly vulnerable to a class break. It shouldn't be too difficult to develop a generic unpacker that would undo the effects of encryption-based products by simply decrypting the IL code and restoring it to its original position. After doing that it would again be possible to feed the entire assembly through a decompiler and receive reasonably readable code (depending on the level of obfuscation performed before encrypting the IL code). By making such an unpacker available online an attacker could virtually nullify the security value offered by such encryption-based solution.

While it is true that at a first glance an obfuscator might seem to provide a weaker level of protection compared to encryption-based solutions, that's not really the case. Many obfuscating transformations are irreversible operations, so even though obfuscated code is not impossible to decipher, it is never going to be possible for an attacker to deobfuscate an assembly and bring it back to its original representation.

To reverse engineer an assembly generated by Protector one would have to somehow decrypt the IL code stored in the executable and then decompile that code using one of the standard IL decompilers. Unfortunately, this decryption process is quite simple considering that the data that is used for producing the encryption/decryption key is embedded inside the assembly. This is the typical limitation of any code encryption technique: The decryption key must be handed to every end user in order for them to be able to run the program, and it can be used for decrypting the encrypted code.

In a little experiment, I conducted on a sample assembly that was obfuscated with the Remotesoft Obfuscator and encrypted with Remotesoft Protector (running in Version-Independent mode) I was able to fairly easily locate the decryption code in the Protector runtime DLL and locate the exact position of the decryption key inside the assembly. By stepping through the decryption code, I was also able to find the location and layout of the encrypted data. Once this information was obtained I was able to create an unpacker program that decrypted the encrypted IL code inside my Protected assembly and dumped those decrypted IL bytes. It would not be too difficult to actually feed these bytes into one of the many available .NET decompilers to obtain a reasonably readable source code for the assembly in question.

This is why you should always first obfuscate a program before passing it through an encryption-based packer like Remotesoft Protector. In case an attacker manages to decrypt and retrieve the original IL code, you want to make sure that code is properly obfuscated. Otherwise, it will be exceedingly easy to recover an accurate approximation of your program's source code simply by decrypting the assembly.

.NET code is vulnerable to reverse engineering, certainly more so than native IA-32 code or native code for most other processor architectures. The combination of metadata and highly detailed IL code makes it possible to decompile IL methods into remarkably readable high-level language code. Obfuscators aim at reducing this vulnerability by a number of techniques, but they have a limited effect that will only slow down determined reversers.

There are two potential strategies for creating more powerful obfuscators that will have a serious impact on the vulnerability of .NET executables. One is to enhance the encryption concept used by Remotesoft Protector and actually use separate keys for different areas in the program. The decryption should be done by programmatically generated IL code that is never the same in two obfuscated programs (to prevent automated unpacking), and should use keys that come from a variety of places (regions of metadata, constants within the code, parameters passed to methods, and so on).

Another approach is to invest in more advanced obfuscating transformations such as the ones discussed in Chapter 10. These are transformations that significantly alter the structure of the code so as to make comprehension considerably more difficult. Such transformations might not be enough to prevent decompilation, but the objective is to dramatically reduce the readability of the decompiled output, to the point where the decompiled output is no longer useful to reversers. Version 3.0 of PreEmptive Solution's DotFuscator product (not yet released at the time of writing) appears to take this approach, and I would expect other developers of obfuscation tools to follow suit.

[2] It is possible to ship a precompiled .NET binary that doesn't contain any IL code, and the primary reason for doing so is security—it is much harder to reverse or decompile such an executable. For more information please see the section later in this chapter on the Remotesoft Protector product.