A software program is only as weak as its weakest link. This is true both from a security standpoint and, to a lesser extent, from a reliability and robustness standpoint. You could expend considerable energy on development practices that focus on secure code and yet end up with a vulnerable program just because of some third-party component your program uses. The same holds true for robustness and reliability. Many industry professionals fail to realize that a poorly written third-party software library can invalidate an entire development team's efforts to produce a high-quality product.

In this chapter, I will demonstrate how reversing can be used for the auditing of a program when source code is unavailable. The general idea is to reverse several code fragments from a program and try to evaluate the code for security vulnerabilities and generally safe programming practices.

The first part of this chapter deals with all kinds of security bugs and demonstrates what they look like in assembly language—from the reversing standpoint. In the second part, I demonstrate a real-world security bug from a live product and attempt to determine the exact error that caused it.

Before I attempt to define what constitutes secure code, I must try and define what the word "security" means in the context of this book. I think security can be defined as having control of the flow of information on a system. This control means that your files stay inside your computer and out of the hands of nosy intruders, while malicious code stays outside of your computer. Needless to say, there are many other aspects to computer security such as the encryption of information that does flow in and out of the computer and the different levels of access rights granted to different users, but these are not as relevant to our current discussion.

So how does reversing relate to maintaining control of the flow of information on a system? The idea is that whenever you install any kind of software product, you are essentially entrusting your computer and all of the data on it to that program. There are two levels in which this is true. First of all, by installing a software product you are trusting that it is benign and that it doesn't contain any malicious components that would intentionally steal or corrupt your data. Believe it or not, that's the simpler part of this story.

The place where things truly get fuzzy is when we start talking about how programs put your system in jeopardy without ever intending to. A simple bug in any kind of software product could theoretically expose your system to malicious code that could steal or corrupt your data. Take an image file such as a JPEG as an example. There are certain types of bugs that could, in some cases, allow a person to take over your system using a specially crafted image file. All it would take is a tiny, otherwise harmless bug in your image viewing program, and that program might inadvertently allow code embedded into the image file to run. What could that code do? Well, just about anything. It would most likely download some sort of backdoor program onto your system, and pave the way for a full-blown hostile takeover (backdoors and other types of malicious programs are discussed in Chapter 8).

The purpose of this chapter is to try and define what makes secure code, and to then demonstrate how we can scan binary executables for these types of security bugs. Unfortunately, attempting to define what makes secure code can sometimes be a futile attempt. This fact should be painfully clear to software developers who constantly release patches that address vulnerabilities found in their program. It can be a never-ending journey—a game of cat and mouse between hackers looking for vulnerabilities and programmers trying to fix them. Few programs start out as being "totally secure," and in fact, few programs ever reach that state.

In this chapter, I will make an attempt to cover the most typical bugs that turn an otherwise-harmless program into a security risk, and will describe how such bugs can be located while a program is being reversed. This is by no means intended to be a complete guide to every possible security hole you could find in software (and I doubt such guide could ever be written), but simply to give an idea of the types of problems typically encountered.

A vulnerability is essentially a bug or flaw in a program that compromises the security of the program and usually of the entire computer on which it is running. Basically, a vulnerability is a flaw in the program that might allow malicious intruders to take advantage of it. In most cases, vulnerabilities start with code that takes information from the outside world. This can be any type of user input such as the command-line parameters that programs receive, a file loaded into the program, or a packet of data sent over the network.

The basic idea is simple—feed the program unexpected input (meaning input that the programmer didn't think it was ever going to be fed) and get it to stray from its normal execution path. A crude way to exploit a vulnerability is to simply get the program to crash. This is typically the easiest objective because in many cases simply feeding the program exceptionally large random blocks of data does the trick.

But crashing a program is just the beginning. The art of finding and exploiting vulnerabilities gets truly interesting when attackers aim to take control of the program and get it to run their own code. This requires an entirely different level of sophistication, because in order to take control of a program attackers must feed it very specific data.

In many cases, vulnerabilities put entire networks at risk because penetrating the outer shell of a network frequently means that you've crossed the last line of defense.

The following sections describe the most common vulnerabilities found in the average program and demonstrate how such vulnerabilities can be utilized by attackers. You'll also find examples of how these vulnerabilities can be found when analyzing assembly language code.

Stack overflows (also known as stack-smashing attacks after the well-known Phrack paper, [Aleph1]) have been around for years and are by far the most popular type of program vulnerability. Basically, stack overflow exploits take advantage of the fact that programs (and particularly those written in C-based languages) frequently neglect to perform bounds checking on incoming data.

A simple stack overflow vulnerability can be created when a program receives data from the outside world, either as user input directly or through a network connection, and naively copies that data onto the stack without checking its length. The problem is that stack variables always have a fixed size, because the offsets generated by the compiler for accessing those variables are predetermined and hard-coded into the machine code. This means that a program can't dynamically allocate stack space based on the amount of information it is passed—it must preallocate enough room in the stack for the largest chunk of data it expects to receive. Of course, properly written code verifies that the received data fits into the stack buffer before copying it, but you'd be surprised how frequently programmers neglect to perform this verification.

What happens when a buffer of an unknown size is copied over into a limited-sized stack buffer? If the buffer is too long to fit into the memory space allocated for it, the copy operation will cause anything residing after the buffer in the stack to be overwritten with whatever is sent as input. This will frequently overwrite variables that reside after the buffer in the stack, but more importantly, if the copied buffer is long enough, it might overwrite the current function's return address.

For example, consider a function that defines the following local variables:

int counter; char string[8]; float number;

What if the function would like to fill string with user-supplied data? It would copy the user supplied data onto string, but if the function doesn't confirm that the user data is eight characters or less and simply copies as many characters as it finds, it would certainly overwrite number, and possibly whatever resides after it in memory.

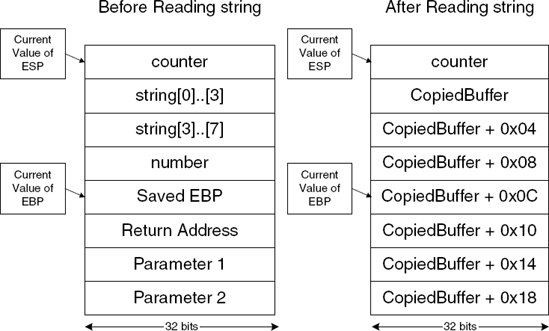

Figure 7.1 shows the function's stack area before and after a stack overwrite. The string variable can only contain eight characters, but far more have been written to it. Note that this figure ignores the (very likely) possibility that the compiler would store some of these variables in registers and not in a stack. The most likely candidate is counter, but this would not affect the stack overflow condition.

The important thing to notice about this is the value of CopiedBuffer + 0x10, because CopiedBuffer + 0x10 now replaces the function's return address. This means that when the function tries to return to the caller (typically by invoking the RET instruction), the CPU will try to jump to whatever address was stored in CopiedBuffer + 0x10. It is easy to see how this could allow an attacker to take control over a system. All that would need to be done is for the attacker to carefully prepare a buffer that contains a pointer to the attacker's code at the correct offset, so that this address would overwrite the function's return address.

A typical buffer overflow includes a short code sequence as the payload (the shellcode [Koziol]) and a pointer to the beginning of that code as the return address. This brings us to one the most difficult parts of effectively overflowing the stack—how do you determine the current stack address in the target program in order to point the return address to the right place? The details of how this is done are really beyond the scope of this book, but the generally strategy is to perform some educated guesses.

For instance, you know that each time you run a program the stack is allocated in the same place, so you can try and guess how much stack space the program has used so far and try and jump to the right place. Alternatively, you could pad our shellcode with NOPs and jump to the memory area where you think the buffer has been copied. The NOPs give you significant latitude because you don't have to jump to an exact location—you can jump to any address that contains your NOPs and execution will just flow into your code.

The most trivial overflow bugs happen when an application stores a temporary buffer in the stack and receives variable-length input from the outside world into that buffer. The classic case is a function that receives a null-terminated string as input and copies that string into a local variable. Here is an example that was disassembled using WinDbg.

Chapter7!launch:

00401060 mov eax,[esp+0x4]

00401064 sub esp,0x64

00401067 push eax

00401068 lea ecx,[esp+0x4]

0040106c push ecx

0040106d call Chapter7!strcpy (00401180)

00401072 lea edx,[esp+0x8]

00401076 push 0x408128

0040107b push edx0040107c call Chapter7!strcat (00401190) 00401081 lea eax,[esp+0x10] 00401085 push eax 00401086 call Chapter7!system (004010e7) 0040108b add esp,0x78 0040108e ret

Before dealing with the specifics of the overflow bug in this code, let's try to figure out the basics of this function. The function was defined with the cdecl calling convention, so the parameters are unwound by the caller. This means that the RET instruction can't be used for determining how many parameters the function takes. Let's try to figure out the stack layout in this function. Start by reading a parameter from [esp+0x4], and then subtract ESP by 100 bytes, to make room for local variables. If you go to the end of the function, you'll see the code that moves ESP back to where it was when I first entered the function. This is the add esp, 0x78, but why is it adding 120 bytes instead of 100? If you look at the function, you'll see three function calls to strcpy, strcat, and system. If you look inside those functions, you'll see that they are all cdecl functions (as are all C runtime library functions), and, as already mentioned, in cdecl functions the caller is responsible for unwinding the parameters from the stack. In this function, instead of adding an add esp, NumberOfBytes after each call, the compiler has chosen to optimize the unwinding process by simply unwinding the parameters from all three function calls at once.

This approach makes for a slightly less "reverser-friendly" function because every time the stack is accessed through ESP, you have to try to figure out where ESP is pointing to for each instruction. Of course, this problem only exists when you're studying a static disassembly—in a live debugger, you can always just look at the value of ESP at any given moment.

Note

From the program's perspective, the unwinding of the stack at the end of the function has another disadvantage: The function ends up using a bit more stack space. This is because the parameters from each of the function calls made during the function's lifetime stay in the stack for the remainder of the function. On the other hand, stack space is generally not a problem in user-mode threads in Windows (as opposed to kernel-mode threads, which have a very limited stack space).

So, what do each of the ESP references in this function access? If you look closely, you'll see that other than the first access at [esp+0x4], the last three stack accesses are all going to the same place. The first is accessing [esp+0x4] and then pushes it into the stack (where it stays until launch returns). The next time the same address is accessed, the offset from ESP has to be higher because ESP is now 4 bytes less than what it was before.

Now that you understand the dynamics of the stack in this function, it becomes easy to see that only two unique stack addresses are being referenced in this function. The parameter is accessed in the first line (and it looks like the function only takes one parameter), and the beginning of the local variable area in the other three accesses.

The function starts by copying a string whose pointer was passed as the first parameter to a local variable (whose size we know is 100 bytes). This is exactly where the potential stack overflow lies. strcpy has no idea how big a buffer has been reserved for the copied string and will keep on copying until it encounters the null terminator in the source string or until the program crashes. If a string longer than 100 bytes is fed to this function, strcpy will essentially overwrite whatever follows the local string variable in the stack. In this particular function, this would be the function's return address. Overwriting the return address is a sure way of gaining control of the system.

The classic exploit for this kind of overflow bug is to feed this function with a string that essentially contains code and to carefully place the pointer to that code in the position where strcpy is going to be overwriting the return address. One thing that makes this process slightly more complicated than it initially seems is that the entire buffer being fed to the function can't contain any zero bytes (except for one at the end), because that would cause strcpy to stop copying.

There are several simple patterns to look for when searching for a stack overflow vulnerability in a program. The first thing is probably to look at a function's stack size. Functions that take large buffers such as strings or other data and put it on the stack are easily identified because they tend to have huge local variable regions in their stack frames. This can be identified by looking for a SUB ESP instruction at the very beginning of the function. Functions that store large buffers on the stack will usually subtract ESP by a fairly large number.

Of course, in itself a large stack size doesn't represent a problem. Once you've located a function that has a conspicuously large stack space, the next step is to look for places where a pointer to the beginning of that space is used. This would typically be a LEA instruction that uses an operand such as [EBP – 0x200], or [ESP – 0x200], with that constant being near or equal to the specific size of the stack space allocated. The trick at this point is to make sure the code that's accessing this block is properly aware of its size. It's not easy, but it's not impossible either.

The C runtime library string-manipulation routines have historically been the reason for quite a few vulnerabilities. Most programmers nowadays know better than to leave such doors wide open, but it's still worthwhile to learn to identify calls to these functions while reversing. The problem is that some compilers treat these functions as intrinsic, meaning that the compiler automatically inserts their implementation into the calling function (like an inline function) instead of calling the runtime library implementation. Here is the same vulnerable launch function from before, except that both string-manipulation calls have been compiled into the function.

Chapter7!launch:

00401060 mov eax,[esp+0x4]

00401064 lea edx,[esp-0x64]

00401068 sub esp,0x64

0040106b sub edx,eax

0040106d lea ecx,[ecx]

00401070 mov cl,[eax]

00401072 mov [edx+eax],cl

00401075 inc eax

00401076 test cl,cl

00401078 jnz Chapter7!launch+0x10 (00401070)

0040107a push edi

0040107b lea edi,[esp+0x4]

0040107f dec edi

00401080 mov al,[edi+0x1]

00401083 inc edi

00401084 test al,al

00401086 jnz Chapter7!launch+0x20 (00401080)

00401088 mov eax,[Chapter7!`string' (00408128)]

0040108d mov cl,[Chapter7!`string'+0x4 (0040812c)]

00401093 lea edx,[esp+0x4]

00401097 mov [edi],eax

00401099 push edx

0040109a mov [edi+0x4],cl

0040109d call Chapter7!system (00401102)

004010a2 add esp,0x4

004010a5 pop edi

004010a6 add esp,0x64004010a9 retIt is safe to say that regardless of intrinsic string-manipulation functions, any case where a function loops on the address of a stack-variable such as the one obtained by the lea edx,[esp-0x64] in the preceding function is worthy of further investigation.

There are many possible ways of dealing with buffer overflow bugs. The first and most obvious way is of course to try to avoid them in the first place, but that doesn't always prove to be as simple as it seems. Sure, it would take a really careless developer to put something like our poor launch in a production system, but there are other, far more subtle mistakes that can create potential buffer overflow bugs.

One technique that aims to automatically prevent these problems from occurring is by the use of automatic, compiler-generated stack checking. The idea is quite simple: For any function that accesses local variables by reference, push an extra cookie or canary to the stack between the last local variable and the function's return address. This cookie should then be validated before the function returns to the caller. If the cookie has been modified, program execution immediately stops. This ensures that the return value hasn't been overwritten with some other address and prevents the execution of any kind of malicious code.

One thing that's immediately clear about this approach is that the cookie must be a random number. If it's not, an attacker could simply add the cookie's value as part of the overflowing payload and bypass the stack protection. The solution is to use a pseudorandom number as a cookie. If you're wondering just how random pseudorandom numbers can be, take a look at [Knuth2] Donald E. Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming - Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms (Second Edition). Addison Wesley, but suffice it to say that they're random enough for this purpose. With a pseudorandom number, the attacker has no way of knowing in advance what the cookie is going to be, and so it becomes impossible to fool the cookie verification code (though it's still possible to work around this whole mechanism in other ways, as explained later in this chapter).

The following code is the same launch function from before, except that stack checking has been added (using the /GS option in the Microsoft C/C++ compiler).

Chapter7!launch:

00401060 sub esp,0x68

00401063 mov eax,[Chapter7!__security_cookie (0040a428)]

00401068 mov [esp+0x64],eax

0040106c mov eax,[esp+0x6c]

00401070 lea edx,[esp]

00401073 sub edx,eax

00401075 mov cl,[eax]

00401077 mov [edx+eax],cl

0040107a inc eax

0040107b test cl,cl

0040107d jnz Chapter7!launch+0x15 (00401075)

0040107f push edi

00401080 lea edi,[esp+0x4]

00401084 dec edi

00401085 mov al,[edi+0x1]

00401088 inc edi

00401089 test al,al

0040108b jnz Chapter7!launch+0x25 (00401085)

0040108d mov eax,[Chapter7!`string' (00408128)]

00401092 mov cl,[Chapter7!`string'+0x4 (0040812c)]00401098 lea edx,[esp+0x4] 0040109c mov [edi],eax 0040109e push edx 0040109f mov [edi+0x4],cl 004010a2 call Chapter7!system (00401110) 004010a7 mov ecx,[esp+0x6c] 004010ab add esp,0x4 004010ae pop edi 004010af call Chapter7!__security_check_cookie (004011d7) 004010b4 add esp,0x68 004010b7 ret

The __security_check_cookie function is called before launch returns in order to verify that the cookie has not been corrupted. Here is what __security_check_cookie does.

__security_check_cookie:

004011d7 cmp ecx,[Chapter7!__security_cookie (0040a428)]

004011dd jnz Chapter7!__security_check_cookie+0x9 (004011e0)

004011df ret

004011e0 jmp Chapter7!report_failure (004011a6)This idea was originally presented in [Cowan], Crispin Cowan, Calton Pu, David Maier, Heather Hinton, Peat Bakke, Steve Beattie, Aaron Grier, Perry Wagle, and Qian Zhang. Automatic Detection and Prevention of Buffer-Overflow Attacks. The 7th USENIX Security Symposium. San Antonio, TX, January 1998 and has since been implemented in several compilers. The latest versions of the Microsoft C/C++ compilers support stack checking, and the Microsoft operating systems (starting with Windows Server 2003 and Windows XP Service Pack 2) take advantage of this feature.

In Windows, the cookie is stored in a global variable within the protected module (usually in __security_cookie). This variable is initialized by __security_init_cookie when the module is loaded, and is randomized based on the current process and thread IDs, along with the current time or the value of the hardware performance counter. In case you're wondering, here is the source code for __security_init_cookie. This code is embedded into any program built using the Microsoft compiler that has stack checking enabled.

Example 7.1. The __security_init_cookie function that initializes the stack-checking cookie in code generated by the Microsoft C/C++ compiler.

void __cdecl __security_init_cookie(void)

{

DWORD_PTR cookie;

FT systime;

LARGE_INTEGER perfctr;/*

* Do nothing if the global cookie has already been initialized.

*/

if (security_cookie && security_cookie != DEFAULT_SECURITY_COOKIE)

return;

/*

* Initialize the global cookie with an unpredictable value which is

* different for each module in a process. Combine a number of sources * of randomness.

*/

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime(&systime.ft_struct);

#if !defined (_WIN64)

cookie = systime.ft_struct.dwLowDateTime;

cookie ^= systime.ft_struct.dwHighDateTime;

#else /* !defined (_WIN64) */

cookie = systime.ft_scalar;

#endif /* !defined (_WIN64) */

cookie ^= GetCurrentProcessId();

cookie ^= GetCurrentThreadId();

cookie ^= GetTickCount();

QueryPerformanceCounter(&perfctr);

#if !defined (_WIN64)

cookie ^= perfctr.LowPart;

cookie ^= perfctr.HighPart;

#else /* !defined (_WIN64) */

cookie ^= perfctr.QuadPart;

#endif /* !defined (_WIN64) */

/*

* Make sure the global cookie is never initialized to zero, since in

* that case an overrun which sets the local cookie and return address

* to the same value would go undetected.

*/

__security_cookie = cookie ? cookie : DEFAULT_SECURITY_COOKIE;

}Unsurprisingly, stack checking is not impossible to defeat [Bulba, Koziol]. Exactly how that's done is beyond the scope of this book, but suffice it to say that in some functions the attacker still has a window of opportunity for writing into a local memory address (which almost guarantees that he or she will be able to take over the program in question) before the function reaches the cookie verification code. There are several different tricks that will work in different cases. One option is to try and overwrite the area in the stack where parameters were passed to the function. This trick works for functions that use stack parameters for returning values to their callers, and is typically implemented by having the caller pass a memory address as a parameter and by having the callee write back into that memory address.

The idea is that when a function has a buffer overflow bug, the memory address used for returning values to the caller (assuming that the function does that) can be overwritten using a specially crafted buffer, which would get the function to overwrite a memory address chosen by the attacker (because the function takes that address and writes to it). By being able to write data to an arbitrary address in memory attackers can sometimes gain control of the process before the stack-checking code finds out that a buffer overflow had occurred. In order to do that, attackers must locate a function that passes values back to the caller using parameters and that has an overflow bug. Then in order to exploit such a vulnerability, they must figure out an address to write to in memory that would allow them to run their own code before the process is terminated by the stack-checking code. This address is usually some kind of global address that controls which code is executed when stack checking fails.

As you can see, exploiting programs that have stack-checking mechanisms embedded into them is not as easy as exploiting simple buffer overflow bugs. This means that even though it doesn't completely eliminate the problem, stack checking does somewhat reduce the total number of possible exploits in a program.

This discussion wouldn't be complete without mentioning one other weapon that helps fight buffer overflows: nonexecutable memory. Certain processors provide support for defining memory pages as nonexecutable, which means that they can only be used for storing data, and that the processor will not run code stored in them. The operating system can then mark stack and data pages as nonexecutable, which prevents an attacker from running code on them using a buffer overflow.

At the time of writing, many new processors already support this functionality (including recent versions of Intel and AMD processors, and the IA-64 Intel processors), and so do many operating systems (including Windows XP Service Pack 2 and above, Solaris 2.6 and above, and several patches implemented for the Linux kernel).

Needless to say, nonexecutable memory doesn't exactly invalidate the whole concept of buffer overflow attacks. It is quite possible for attackers to overcome the hurdles imposed by nonexecutable memory systems, as long as a vulnerable piece of code is found [Designer, Wojtczuk]. The most popular strategy (often called return-to-libc) is to modify the function's return address to point to a well-known function (such as a runtime library function or a system API) that helps attackers gain control over the process. This completely avoids the problem of having a nonexecutable stack, but requires a slightly more involved exploit.

Another type of overflow that can be used for taking control of a program or of the entire system is the malloc exploit or heap overflow [anonymous], [Kaempf], [jp]. The general idea is the same as a stack overflow: programs receive data of an unexpected length and copy it into a buffer that's too small to contain it. This causes the program to overwrite whatever it is that follows the heap block in memory. Typically, heaps are arranged as linked lists, and the pointers to the next and previous heap blocks are placed either right before or right after the actual block data. This means that writing past the end of a heap block would corrupt that linked list in some way. Usually, this causes the program to crash as soon as the heap manager traverses the linked list (in order to free a block for example), but when done carefully a heap overflow can be used to take over a system.

The idea is that attackers can take advantage of the heap's linked-list structure in order to overwrite some memory address in the process's address space. Implementing such attacks can be quite complicated, but the basic idea is fairly straightforward. Because each block in the linked list has "next" and "prev" members, it is possible to overwrite these members in a way that would allow the attacker to write an arbitrary value into an arbitrary address in memory.

Think of what takes place when an element is removed from a doubly linked list. The system must correct the links in the two adjacent items on the list (both the previous item and the next item), so that they correctly link to one another, and not to the item you're currently deleting. This means that when the item is removed, the code will write the address of the next member into the previous item's header (it will take both addresses from the header of item currently being deleted), and the address of the prev item into the next item's header (again, the addresses will be taken from the item currently being deleted). It's not easy, but by carefully overwriting the values of these next and prev members in one item on the list, attackers can in some cases manage to overwrite strategic memory addresses in the process address space. Of course, the overwrite doesn't take place immediately—it only happens when the overwritten item is freed.

It should be noted that heap overflows are usually less common than stack overflows because the sizes of heap blocks are almost always dynamically calculated to be large enough to fit the incoming data. Unlike stack buffers, whose size must be predefined, heap buffers have a dynamic size (that's the whole point of a heap). Because of this, programmers rarely hard-code the size of a heap block when they have variably sized incoming data that they wish to fit into that block. Heap blocks typically become a problem when the programmer miscalculates the number of bytes needed to hold a particular user-supplied buffer in memory.

Traditionally, a significant portion of overflow attacks have been string-related. The most common example has been the use of the various runtime library string-manipulation routines for copying or processing strings in some way, while letting the routine determine how much data should be written. This is the common strcpy case demonstrated earlier, where an outsider is allowed to provide a string that is copied into a fixed-sized internal buffer through strcpy. Because strcpy only stops copying when it encounters a NULL terminator, the caller can supply a string that would be too long for the target buffer, thus causing an overflow.

What happens if the attacker's string is internally converted into Unicode (as most strings are in Win32) before it reaches the vulnerable function? In such cases the attacker must feed the vulnerable program a sequence of ASCII characters that would become a workable shellcode once converted into Unicode! This effectively means that between each attacker-provided opcode byte, the Unicode conversion process will add a zero byte. You may be surprised to learn that it's actually possible to write shellcodes that work after they're converted to Unicode. The process of developing working shellcodes in this hostile environment is discussed in [obscou]. What can I say, being an attacker isn't easy.

Integer overflows (see [blexim], [Koziol]) are a special type of overflow bug where incorrect treatment of integers can lead to a numerical overflow which eventually results in a buffer overflow. The common case in which this happens is when an application receives the length of some data block from the outside world. Except for really extreme cases of recklessness, programmers typically perform some sort of bounds checking on such an integer. Unfortunately, safely checking an integer value is not as trivial as it seems, and there are numerous pitfalls that could allow bad input values to pass as legal values. Here is the most trivial example:

push esi push 100 ; /size = 100 (256.) call Chapter7.malloc ; \malloc mov esi,eax add esp,4 test esi,esi je short Chapter7.0040104E mov eax,dword ptr [esp+C] cmp eax,100 jg short Chapter7.0040104E push eax ; /maxlen mov eax,dword ptr [esp+C] ; | push eax ; |src push esi ; |dest call Chapter7.strncpy ; \strncpy add esp,0C Chapter7.0040104E: mov eax,esipop esi retn

This function allocates a fixed size buffer (256 bytes long) and copies a user-supplied string into that buffer. The length of the source buffer is also user-supplied (through [esp + c]). This is not a typical overflow vulnerability and is slightly less obvious because the user-supplied length is checked to make sure that it doesn't exceed the allocated buffer size (that's the cmp eax, 100). The caveat in this particular sample is the data type of the buffer-length parameter.

There are two conditional code groups in IA-32 assembly language, signed and unsigned, each operating on different CPU flags. The conditional code used in a conditional jump usually exposes the exact data type used in the comparison in the original source code. In this particular case, the use of JG (jump if greater) indicates that the compiler was treating the buffer length parameter as a signed integer. If the parameter was defined as an unsigned integer or simply cast to an unsigned integer during the comparison, the compiler would have generated JA (jump if above) instead of JG for the comparison. You'll find more information on flags and conditional codes in Appendix A.

Signed buffer-length comparisons are dangerous because with the right input value it is possible to bypass the buffer length check. The idea is quite simple. Conceptually, buffer lengths are always unsigned values because there is no such thing as a negative buffer length—a buffer length variable can only be 0 or some positive integer. When buffer lengths are stored as signed integers comparisons can produce unexpected results because the condition SignedBufferLen <= MAXIMUM_LEN would not only be satisfied when 0 <= SignedBufferLen <= MAXIMUM_LEN, but also when SignedBufferLen < 0. Of course, functions that take buffer lengths as input can't possibly use negative values, so any negative value is treated as a very large number.

Integer overflows come in many flavors. Consider, for example, another case where the buffer length is received from the attacker and is then somehow modified. This is quite common, especially if the program needs to store the user-supplied buffer along with some header or other fixed-sized supplement. Suppose the program takes the user-supplied length and adds a certain constant to it—this will typically be a header length of some sort. This can create significant risks because an attacker could take advantage of integer overflows to create a buffer overflow. Here is an example of code that does this sort of thing:

allocate_object:

00401021 push esi

00401022 push edi

00401023 mov edi,[esp+0x10]

00401027 lea esi,[edi+0x18]

0040102a push esi

0040102b call Chapter7!malloc (004010d8)

00401030 pop ecx

00401031 xor ecx,ecx

00401033 cmp eax,ecx

00401035 jnz Chapter7!allocate_object+0x1a (0040103b)

00401037 xor eax,eax

00401039 jmp Chapter7!allocate_object+0x42 (00401063)

0040103b mov [eax+0x4],ecx

0040103e mov [eax+0x8],ecx

00401041 mov [eax+0xc],ecx

00401044 mov [eax+0x10],ecx

00401047 mov [eax+0x14],ecx

0040104a mov ecx,edi

0040104c mov edx,ecx

0040104e mov [eax],esi

00401050 mov esi,[esp+0xc]

00401054 shr ecx,0x2

00401057 lea edi,[eax+0x18]

0040105a rep movsd

0040105c mov ecx,edx

0040105e and ecx,0x3

00401061 rep movsb

00401063 pop edi

00401064 pop esi

00401065 retThe preceding contrived, yet somewhat realistic, function takes a buffer pointer and a buffer length as parameters and allocates a buffer of the length passed to it via [esp+0x10] plus 0x18 (24 bytes). It then initializes what appears to be some kind of a buffer in the beginning and copies the user supplied buffer from [esp+0xc] to offset +18 in the newly allocated block (that's the lea edi,[eax+0x18]). The return value is the pointer of the newly allocated block. Clearly, the idea is that an object is being allocated with a 24-bytes-long buffer. The buffer is being zero initialized, except for the first member at offset +0, which is set to the total size of the buffer allocated. The user-supplied buffer is then placed after the header in the newly allocated block.

At first glance, this code appears to be perfectly safe because the function only writes as many bytes to the allocated buffer as it managed to allocate. The problem is that, as usual, we're dealing with values coming in from the outside world; there's no way of knowing what we're going to get. In this particular case, the problem is caused by the arithmetic operation performed on the buffer length parameter.

The lea esi,[edi+0x18] at address 00401027 seems innocent, but what happens if EDI contains a very high value that's close to 0xffffffff? In such a case, the addition would overflow and the result would be a low positive number, possibly lower than the length of the buffer itself! Suppose, for example, that you feed the function with 0xfffffff8 as the buffer length. 0xfffffff8 + 0x18 = 0x100000010, but that number is larger than 32 bits. The processor is truncating the result, and you end up with 0x00000010.

Keeping in mind that the buffer length copied by the function is the original supplied length (before the header length was added to it), you can now see how this function would definitely crash. The malloc call will allocate a buffer of 0x10 bytes long, but the function will try to copy 0xfffffff8 bytes to the newly allocated buffer, thus crashing the program.

The solution to this problem is to take a limited-sized input and make sure that the target variable can contain the largest possible result. For example, assuming that 16 bits are enough to represent the user buffer length; simply changing the preceding program to use an unsigned short for the user buffer length would solve the problem. Here is what the corrected version of this function looks like:

allocate_object:

00401024 push esi

00401025 movzx esi,word ptr [esp+0xc]

0040102a push edi

0040102b lea edi,[esi+0x18]

0040102e push edi

0040102f call Chapter7!malloc (004010dc)

00401034 pop ecx

00401035 xor ecx,ecx

00401037 cmp eax,ecx

00401039 jnz Chapter7!allocate_object+0x1b (0040103f)

0040103b xor eax,eax

0040103d jmp Chapter7!allocate_object+0x43 (00401067)

0040103f mov [eax+0x4],ecx

00401042 mov [eax+0x8],ecx

00401045 mov [eax+0xc],ecx00401048 mov [eax+0x10],ecx 0040104b mov [eax+0x14],ecx 0040104e mov ecx,esi 00401050 mov esi,[esp+0xc] 00401054 mov edx,ecx 00401056 mov [eax],edi 00401058 shr ecx,0x2 0040105b lea edi,[eax+0x18] 0040105e rep movsd 00401060 mov ecx,edx 00401062 and ecx,0x3 00401065 rep movsb 00401067 pop edi 00401068 pop esi 00401069 ret

This function is effectively identical to the original version presented earlier, except for movzx esi,word ptr [esp+0xc] at 00401025. The idea is that instead of directly loading the buffer length from the stack and adding 0x18 to it, we now treat it as an unsigned short, which eliminates the possibly of causing an overflow because the arithmetic is performed using 32-bit registers. The use of the MOVZX instruction is crucial here and is discussed in the next section.

Sometimes software developers don't fully understand the semantics of the programming language they are using. These semantics can be critical because they define (among other things) how data is going to be handled at a low level. Type conversion errors take place when developers mishandle incoming data types and perform incorrect conversions on them. For example, consider the following variant on my famous allocate_object function:

allocate_object:

00401021 push esi

00401022 movsx esi,word ptr [esp+0xc]

00401027 push edi

00401028 lea edi,[esi+0x18]

0040102b push edi

0040102c call Chapter7!malloc (004010d9)

00401031 pop ecx

00401032 xor ecx,ecx

00401034 cmp eax,ecx

00401036 jnz Chapter7!allocate_object+0x1b (0040103c)

00401038 xor eax,eax

0040103a jmp Chapter7!allocate_object+0x43 (00401064)

0040103c mov [eax+0x4],ecx

0040103f mov [eax+0x8],ecx00401042 mov [eax+0xc],ecx 00401045 mov [eax+0x10],ecx 00401048 mov [eax+0x14],ecx 0040104b mov ecx,esi 0040104d mov esi,[esp+0xc] 00401051 mov edx,ecx 00401053 mov [eax],edi 00401055 shr ecx,0x2 00401058 lea edi,[eax+0x18] 0040105b rep movsd 0040105d mov ecx,edx 0040105f and ecx,0x3 00401062 rep movsb 00401064 pop edi 00401065 pop esi 00401066 ret

The important thing about this version of allocate_object is the supplied buffer length's data type. When reading assembly language code, you must always be aware of every little detail—that's exactly where all the valuable information is hidden. See if you can find the difference between this function and the earlier version.

It turns out that this function is treating the buffer length as a signed short. This creates a potential problem because in C and C++ the compiler doesn't really care what you're doing with an integer—as long as it's defined as signed and it's converted into a longer data type, it will be sign extended, no matter what the target data type is. In this particular example, malloc takes a size_t, which is of course unsigned. This means that the buffer length would be sign extended before it is passed into malloc and to the code that adds 0x18 to it. Here is what you should be looking for:

00401022 movsx esi,word ptr [esp+0xc]

This line copies the parameter from the stack into ESI, while treating it as a signed short and therefore sign extends it. Sign extending means that if the buffer length parameter has its most significant bit set, it would be converted into a negative 32-bit number. For example, a buffer length of 0x9400 (which is 37888 in decimal) would become 0xffff9400 (which is 4294939648 in decimal), instead of 0x00009400.

Generally, this would cause an overflow bug in the allocation size and the allocation would simply fail, but if you look carefully you'll notice that this problem also brings back the bug looked at earlier, where adding the header size to the user-supplied buffer length causedan overflow. That's because the MOVSX instruction can generate the same large negative values that were causing the overflow earlier. Consider a case where the function is fed 0xfff8 as the buffer length. The MOVSX instruction would convert that into 0xfffffff8, and you'd be back with the same overflow situation caused by the lea edi,[esi+0x18] instruction.

The solution to these problems is to simply define the buffer length as an unsigned short, which would cause the compiler to use MOVZX instead of MOVSX. MOVZX zero extends the integer during conversion (meaning simply that the most significant word in the target 32-bit integer is set to zero), so that its numeric value stays the same.

Let's take a look at what one of these bugs look like in a real commercial software product. This is different from what you've done up to this point because all of the samples you've looked at so far in this chapter were short samples created specifically to demonstrate one particular bug or another. With a commercial product, the challenging part is typically the magnitude of code we need to look at. Sure, eventually when you locate the bug it looks just like it did in the brief samples, but the challenge is to make out these bugs inside an endless sea of code.

In June 2001, a nasty vulnerability was discovered in versions 4 and 5 of the Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS). The main problem was that any Windows 2000 Server system was vulnerable in its default configuration out of the box. The vulnerability was caused by an unchecked buffer in an ISAPI (Internet Services Application Programming Interface) DLL. ISAPI is an interface that is used for creating IIS extension DLLs that provide server-side functionality in the Web server. The vulnerability was found in idq.dll—an ISAPI DLL that interfaces with the Indexing Service and is installed as a part of IIS.

The vulnerability (which was posted by Microsoft as security bulletin MS01-044) was actually exploited by the Code Red Worm, of which you've probably heard. Code Red had many different variants, but generally speaking it would operate on a monthly cycle (meaning that it would do different things on different days of the month). During much of the time, the worm would simply try to find other vulnerable hosts to which it could spread. At other times, the worm would intercept all incoming HTTP requests and make IIS send back the following message instead of any meaningful Web page:

HELLO! Welcome to http://www.worm.com! Hacked By Chinese!

The vulnerability in IIS was caused by a combination of several flaws, but most important was the fact that URLs sent to IIS that contained an .idq or .ida file name resulted in the URL parameters being passed into idq.dll (regardless of whether the file is actually found). Once inside idq.dll, the URL was decoded and converted to Unicode inside a limited-sized stack variable, with absolutely no bounds checking.

In order to illustrate what this problem actually looks like in the code, I have listed parts of the vulnerable code here. These listings are obviously incomplete—these functions are way too long to be included in their entirety.

The function that actually contains the overflow bug is CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock, which is implemented in idq.dll. Listing 7.2 contains a partial listing (I have eliminated some irrelevant portions of it) of that function.

Notice that we have the exact name of this function and of other internal, nonexported functions inside this module. idq.dll is considered part of the operating system and so symbols are available. The printed code was taken from a Windows Server 2000 system with no service packs, but there are quite a few versions of the operating system that contained the vulnerable code, including Service Packs 1, 2, and 3 for Windows 2000 Server.

Example 7.2. Disassembled listing of CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock from idq.dll.

idq!CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock: 6e90065c mov eax,0x6e906af8 6e900661 call idq!_EH_prolog (6e905c30) 6e900666 sub esp,0x1d0 6e90066c push ebx 6e90066d xor eax,eax 6e90066f push esi 6e900670 push edi 6e900671 mov [ebp-0x24],ecx 6e900674 mov [ebp-0x2c],eax 6e900677 mov [ebp-0x28],eax 6e90067a mov [ebp-0x4],eax 6e90067d mov eax,[ebp+0x8] . . . 6e9006b7 mov esi,[eax+0x64] 6e9006ba or ecx,0xffffffff 6e9006bd mov edi,esi . . . 6e9007b7 push 0x3d 6e9007b9 push edi 6e9007ba mov [ebp-0x18],edi 6e9007bd call dword ptr [idq!_imp__strchr (6e8f111c)]

6e9007c3 mov esi,eax 6e9007c5 pop ecx 6e9007c6 test esi,esi 6e9007c8 pop ecx 6e9007c9 je 6e9008d2 6e9007cf sub eax,edi 6e9007d1 push 0x26 6e9007d3 push edi 6e9007d4 mov [ebp-0x20],eax 6e9007d7 inc esi 6e9007d8 call dword ptr [idq!_imp__strchr (6e8f111c)] 6e9007de mov edi,eax 6e9007e0 pop ecx 6e9007e1 test edi,edi 6e9007e3 pop ecx 6e9007e4 jz 6e9007fa 6e9007e6 cmp edi,esi 6e9007e8 jnb 6e9007f0 6e9007ea inc edi 6e9007eb jmp 6e9008e4 6e9007f0 mov eax,edi 6e9007f2 sub eax,esi 6e9007f4 inc edi 6e9007f5 mov [ebp-0x14],eax 6e9007f8 jmp 6e900804 6e9007fa mov eax,[ebp-0x10] 6e9007fd sub eax,esi 6e9007ff add eax,ebx 6e900801 mov [ebp-0x14],eax 6e900804 cmp dword ptr [ebp-0x20],0x190 6e90080b jb 6e900828 6e90080d mov eax,0x80040e14 6e900812 xor ecx,ecx 6e900814 mov [ebp-0x3c],eax 6e900817 lea eax,[ebp-0x3c] 6e90081a push 0x6e9071b8 6e90081f push eax 6e900820 mov [ebp-0x38],ecx 6e900823 call idq!_CxxThrowException (6e905c36) 6e900828 mov eax,[ebp+0x8] 6e90082b push dword ptr [eax+0x8] 6e90082e lea eax,[ebp-0x1dc] 6e900834 push eax 6e900835 lea eax,[ebp-0x20] 6e900838 push eax 6e900839 push dword ptr [ebp-0x18] 6e90083c call idq!DecodeURLEscapes (6e9060be) 6e900841 xor ecx,ecx

6e900843 cmp [ebp-0x20],ecx 6e900846 jnz 6e900861 6e900848 mov eax,0x80040e14 6e90084d push 0x6e9071b8 6e900852 mov [ebp-0x44],eax 6e900855 lea eax,[ebp-0x44] 6e900858 push eax 6e900859 mov [ebp-0x40],ecx 6e90085c call idq!_CxxThrowException (6e905c36) 6e900861 lea eax,[ebp-0x1dc] 6e900867 push eax 6e900868 call idq!DecodeHtmlNumeric (6e9060b8) 6e90086d lea eax,[ebp-0x1dc] 6e900873 push eax 6e900874 call dword ptr [idq!_imp___wcsupr (6e8f1148)] 6e90087a mov eax,[ebp-0x14] 6e90087d pop ecx 6e90087e add eax,0x2 6e900881 mov [ebp-0x30],eax 6e900884 add eax,eax 6e900886 push eax 6e900887 call idq!ciNew (6e905f86) 6e90088c mov [ebp-0x34],eax 6e90088f mov ecx,[ebp+0x8] 6e900892 mov byte ptr [ebp-0x4],0x 26e900896 push dword ptr [ecx+0x8] 6e900899 push eax 6e90089a lea eax,[ebp-0x14] 6e90089d push eax 6e90089e push esi 6e90089f call idq!DecodeURLEscapes (6e9060be) 6e9008a4 cmp dword ptr [ebp-0x14],0x0 6e9008a8 jz 6e9008b2 6e9008aa push dword ptr [ebp-0x34] 6e9008ad call idq!DecodeHtmlNumeric (6e9060b8) 6e9008b2 mov ecx,[ebp-0x24] 6e9008b5 lea edx,[ebp-0x34] 6e9008b8 push edx 6e9008b9 lea edx,[ebp-0x1dc] 6e9008bf mov eax,[ecx] 6e9008c1 push edx 6e9008c2 call dword ptr [eax] 6e9008c4 push dword ptr [ebp-0x34] 6e9008c7 and byte ptr [ebp-0x4],0x 06e9008cb call idq!ciDelete (6e905f8c) 6e9008d0 jmp 6e9008e4 6e9008d2 test edi,edi 6e9008d4 jz 6e9008ec

6e9008d6 inc edi 6e9008d7 push 0x26 6e9008d9 push edi 6e9008da call dword ptr [idq!_imp__strchr (6e8f111c)] 6e9008e0 pop ecx 6e9008e1 mov edi,eax 6e9008e3 pop ecx 6e9008e4 test edi,edi 6e9008e6 jne 6e9007ae 6e9008ec push dword ptr [ebp-0x2c] 6e9008ef or dword ptr [ebp-0x4],0xffffffff 6e9008f3 call idq!ciDelete (6e905f8c) 6e9008f8 mov ecx,[ebp-0xc] 6e9008fb pop edi 6e9008fc pop esi 6e9008fd mov fs:[00000000],ecx 6e900904 pop ebx 6e900905 leave 6e900906 ret 0x4

CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock starts with the setting up of an exception handler entry and then subtracts ESP by 0x1d0 (464 bytes) to make room for local variables. One can immediately suspect that a significant chunk of data is about to be copied into this stack space—few functions use 464 bytes worth of local variables. In the first snippet the point of interest is the loading of EAX, which is loaded with the value of the first parameter (from [ebp+0x8]).

A quick investigation with WinDbg reveals that CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock is called from HttpExtensionProc, which is a documented callback that's used by IIS for communicating with ISAPI DLLs. A quick trip to the Platform SDK reveals that HttpExtensionProc receives a single parameter, which is a pointer to an EXTENSION_CONTROL_BLOCK structure. In the interest of preserving the earth's forests, I skip several pages of irrelevant code and get to the three lines at 6e9006b7, where offset +64 from EAX is loaded into ESI and then finally into EDI. Offset +64 in EXTENSION_CONTROL_BLOCK is the lpszQueryString member, which is exactly what we're after.

The instruction at 6e9007ba stores EDI into [ebp-0x18] (where it remains), and then the code goes to look for character 0x3d within the string using strchr. Character 0x3d is '=', so the function is clearly looking for the end of the string I'm currently dealing with (the '=' character is used as a separator in these request strings). If strchr finds the character the function proceeds to calculate the distance between the character found and the beginning of the string (this is done in 6e9007cf). This distance is stored in [ebp-0x20], and is essentially the length of the string I'm are currently dealing with.

An interesting comparison is done in 6e900804, where the function compares the string length with 0x190 (400 in decimal), and throws a C++ exception using _CxxThrowException if it's 400 or above. So, it seems that the function does have some kind of boundary checking on the URL. Where is the problem here? I'm just getting to it.

When the string length comparison succeeds, the function jumps to where it sets up a call to DecodeURLEscapes. DecodeURLEscapes takes four parameters: The pointer to the string from [ebp-0x18], a pointer to the string length from [ebp-0x20], a pointer to the beginning of the local variable area from [ebp-0x1dc], and offset +8 in EXTENSION_CONTROL_BLOCK. Clearly DecodeURLEscapes is about to copy, or decode, a potentially problematic string into the local variable area in the stack.

In order to better understand this bug, let's take a look at DecodeURLEscapes, even though it is not strictly where the bug is at. This function is presented in Listing 7.3. Again, this listing is incomplete and only includes the relevant areas of DecodeURLEscapes.

Example 7.3. Disassembly of DecodeURLEscapes function from query.dll.

query!DecodeURLEscapes: 68cc697e mov eax,0x68d667cc 68cc6983 call query!_EH_prolog (68d4b250) 68cc6988 sub esp,0x30 68cc698b push ebx 68cc698c push esi 68cc698d xor eax,eax 68cc698f push edi 68cc6990 mov edi,[ebp+0x10] 68cc6993 mov [ebp-0x3c],eax 68cc6996 mov [ebp-0x38],eax 68cc6999 mov ecx,[ebp+0xc] 68cc699c mov [ebp-0x4],eax 68cc699f mov [ebp-0x18],eax 68cc69a2 mov ecx,[ecx] 68cc69a4 cmp ecx,eax 68cc69a6 mov [ebp-0x10],ecx 68cc69a9 jz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x99 (68cc6a17) 68cc69ab mov esi,[ebp+0x8] 68cc69ae mov eax,ecx 68cc69b0 inc eax 68cc69b1 mov [ebp-0x14],eax 68cc69b4 movzx bx,byte ptr [esi]

68cc69b8 and dword ptr [ebp-0x34],0x0 68cc69bc cmp bx,0x2b 68cc69c0 jne query!DecodeURLEscapes+0xdf (68cc6a5d) 68cc69c6 push 0x2 068cc69c8 pop ebx 68cc69c9 inc esi 68cc69ca xor eax,eax 68cc69cc cmp [ebp-0x34],eax 68cc69cf jnz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x79 (68cc69f7) 68cc69d1 cmp bx,0x80 68cc69d6 jb query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x79 (68cc69f7) 68cc69d8 cmp [ebp-0x18],eax 68cc69db jnz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x79 (68cc69f7) 68cc69dd cmp [ebp-0x3c],eax 68cc69e0 jnz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x73 (68cc69f1) 68cc69e2 mov eax,[ebp-0x14] 68cc69e5 push eax 68cc69e6 mov [ebp-0x38],eax 68cc69e9 call query!ciNew (68d4a977) 68cc69ee mov [ebp-0x3c],eax 68cc69f1 mov eax,[ebp-0x3c] 68cc69f4 mov [ebp-0x18],eax 68cc69f7 mov eax,[ebp-0x18] 68cc69fa test eax,eax 68cc69fc jz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x88 (68cc6a06) 68cc69fe mov [eax],bl 68cc6a00 inc eax 68cc6a01 mov [ebp-0x18],eax 68cc6a04 jmp query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x8d (68cc6a0b) 68cc6a06 mov [edi],bx 68cc6a09 inc edi 68cc6a0a inc edi 68cc6a0b dec dword ptr [ebp-0x10] 68cc6a0e dec dword ptr [ebp-0x14] 68cc6a11 cmp dword ptr [ebp-0x10],0x0 68cc6a15 jnz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0x36 (68cc69b4) 68cc6a17 test eax,eax 68cc6a19 jz query!DecodeURLEscapes+0xb4 (68cc6a32) 68cc6a1b sub eax,[ebp-0x3c] 68cc6a1e push eax 68cc6a1f push edi 68cc6a20 push eax 68cc6a21 push dword ptr [ebp-0x3c] 68cc6a24 push 0x1 68cc6a26 push dword ptr [ebp+0x14] 68cc6a29 call dword ptr [query!_imp__MultiByteToWideChar (68c61264)] 68cc6a2f lea edi,[edi+eax*2] 68cc6a32 and word ptr [edi],0x0

68cc6a36 sub edi,[ebp+0x10] 68cc6a39 mov eax,[ebp+0xc] 68cc6a3c push dword ptr [ebp-0x3c] 68cc6a3f or dword ptr [ebp-0x4],0xffffffff 68cc6a43 sar edi,1 68cc6a45 mov [eax],edi 68cc6a47 call query!ciDelete (68d4a9ae) 68cc6a4c mov ecx,[ebp-0xc] 68cc6a4f pop edi 68cc6a50 pop esi 68cc6a51 mov fs:[00000000],ecx 68cc6a58 pop ebx 68cc6a59 leave 68cc6a5a ret 0x10 . . .

Before you start inspecting DecodeURLEscapes, you must remember that the first parameter it receives is a pointer to the source string, and the third is a pointer to the local variable area in the stack. That local variable is where one expects the function will be writing a decoded copy of the source string. The first parameter is loaded into ESI and the third into EDI. The second parameter is a pointer to the string length and is copied into [ebp-0x10]. So much for setups.

The function then gets into a copying loop that copies ASCII characters from ESI into BX (this is that MOVZX instruction at 68cc69b4). It then writes them into the address from EDI as zero-extended 16-bit values (this happens at 68cc6a06). This is simply a conversion into Unicode, where the Unicode string is being written into a local variable whose pointer was passed from CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock.

In the process, the function is looking for special characters in the string which indicate special values within the string that need to be decoded (most of the decoding sequences are not included in this listing). The important thing to notice is how the function is decrementing the value at [ebp-0x10] and checking that it's nonzero. You now have a full picture of what causes this bug.

CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock is allocating what seems to be a 400-bytes-long buffer that receives the decoded string from DecodeURLEscapes. The function is checking that the source string (which is in ASCII) is 400 characters long, but DecodeURLEscapes is writing the string in Unicode! Most likely the buffer in CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock was defined as a 200-character Unicode string (usually defined using the WCHAR type). The bug is that the length comparison is confusing bytes with Unicode characters. The buffer can only hold 200 Unicode characters, but the check is going to allow 400 characters.

As with many buffer overflow conditions, exploiting this bug isn't as easy as it seems. First of all, whatever you do you wouldn't be able to affect DecodeURLEscapes, only CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock. That's because the vulnerable local variable is part of CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock's stack area, and DecodeURLEscapes stores its local variables in a lower address in the stack. You can overwrite as many as 400 bytes of stack space beyond the end of the WCHAR local variable (that's the difference between the real buffer size and the maximum bytes the boundary check would let us write). This means that you can definitely get to CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock's return value, and probably to the return values of several calls back. It turns out that it's not so simple.

First of all, take a look at what CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock does after DecodeURLEscapes returns. Assuming that the function succeeds, it goes on to perform some additional processing on the converted string (it calls DecodeHtmlNumeric and wcsupr to convert the string to uppercase). In most cases, these operations will be unaffected by the fact that the stack has been overwritten, so the function will simply keep on running. The trouble starts afterward, at 6e90088f when the function is reading the pointer to EXTENSION_CONTROL_BLOCK from [ebp+0x8]—there is no way to modify the function's return value without affecting this parameter. That's because even if the last bit of data transmitted is a carefully selected return address for CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock, DecodeURLEscapes would still overwrite 2 bytes at [ebp+0x8] when it adds a Unicode NULL terminator.

This creates a problem because the function tries to access the EXTENSION_CONTROL_BLOCK before it returns. Corrupting the pointer at [ebp+0x8] means that the function will crash before it jumps to the new return value (this will probably happen at 6e900896, when the function tries to access offset +8 in that structure). The solution here is to use the exception handler pointer instead of the function's return value. If you go back to the beginning of CVariableSet::AddExtensionControlBlock, you'll see that it starts by setting EAX to 0x6e906af8 and then calls idq!_EH_prolog. This sequence sets up exception handling for the function. 0x6e906af8 is a pointer to code that the system will execute in case of an exception.

The call to idq!_EH_prolog is essentially pushing exception-handling information into the stack. The system is keeping a pointer to this stack address in a special memory location that is accessed through fs:[0]. When the buffer overflow occurs, it's also overwriting this exception-handling data structure, and you can replace the exception handler's address with whatever you wish. This way, you don't have to worry about corrupting the EXTENSION_CONTROL_BLOCK pointer. You just make sure to overwrite the exception handler pointer, and when the function crashes the system will call the function to handle the exception.

There is one other problem with exploiting this code. Remember that whatever is fed into DecodeURLEscapes will be translated into Unicode. This means that the function will add a byte with 0x0 between every byte you send it. How can you possibly construct a usable address for the exception handler in this way? It turns out that you don't have to. Among its many talents, DecodeURLEscapes also supports the decoding of hexadecimal digits into binary form, so you can include escape codes such as %u1234 in your URL, and DecodeURLEscapes will write the values right into the target string—no Unicode conversion problems!

Security holes can be elusive and hard to define. The fact is that even with source code it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish safe, harmless code from dangerous security vulnerabilities. Still, when you know what type of problems you're looking for and you have certain code areas that you know are high risk, it is definitely possible to estimate whether a given function is safe or not by reversing it. All it takes is an understanding of the system and what makes code safe or unsafe.

If you've never been exposed to the world of security and hacking, I hope that this chapter has served as a good introduction to the topic. Still, this barely scratches the surface. There are thousands of articles online and dozens of books on these subjects. One good place to start is Phrack, the online magazine at www.phrack.org. Phrack is a remarkable resource of attack and exploitation techniques, and offers a wealth of highly technical articles on a variety of hacking-related topics. In any case, I urge you to experiment with these concepts on your own, either by reversing live code from well-known vulnerabilities or by experimenting with your own code.