Cracking is the "dark art" of defeating, bypassing, or eliminating any kind of copy protection scheme. In its original form, cracking is aimed at software copy protection schemes such as serial-number-based registrations, hardware keys (dongles), and so on. More recently, cracking has also been applied to digital rights management (DRM) technologies, which attempt to protect the flow of copyrighted materials such as movies, music recordings, and books. Unsurprisingly, cracking is closely related to reversing, because in order to defeat any kind of software-based protection mechanism crackers must first determine exactly how that protection mechanism works.

This chapter provides some live cracking examples. I'll be going over several programs and we'll attempt to crack them. I'll be demonstrating a wide variety of interesting cracking techniques, and the level of difficulty will increase as we go along.

Why should you learn and understand cracking? Well, certainly not for stealing software! I think the whole concept of copy protections and cracking is quite interesting, and I personally love the mind-game element of it. Also, if you're interested in protecting your own program from cracking, you must be able to crack programs yourself. This is an important point: Copy protection technologies developed by people who have never attempted cracking are never effective!

Actual cracking of real copy protection technologies is considered an illegal activity in most countries. Yes, this chapter essentially demonstrates cracking, but you won't be cracking real copy protections. That would not only be illegal, but also immoral. Instead, I will be demonstrating cracking techniques on special programs called crackmes. A crackme is a program whose sole purpose is to provide an intellectual challenge to crackers, and to teach cracking basics to "newbies". There are many hundreds of crackmes available online on several different reversing Web sites.

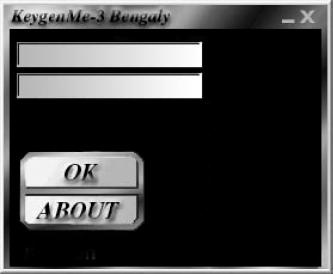

Let's take the first steps in practical cracking. I'll start with a very simple crackme called KeygenMe-3 by Bengaly.When you first run KeygenMe-3 you get a nice (albeit somewhat intimidating) screen asking for two values, with absolutely no information on what these two values are. Figure 11.1 shows the KeygenMe-3 dialog.

Typing random values into the two text boxes and clicking the "OK" button produces the message box in Figure 11.2. It takes a trained eye to notice that the message box is probably a "stock" Windows message box, probably generated by one of the standard Windows message box APIs. This is important because if this is indeed a conventional Windows message box, you could use a debugger to set a breakpoint on the message box APIs. From there, you could try to reach the code in the program that's telling you that you have a bad serial number. This is a fundamental cracking technique—find the part in the program that's telling you you're unauthorized to run it. Once you're there it becomes much easier to find the actual logic that determines whether you're authorized or not.

Note

Unfortunately for crackers, sophisticated protection schemes typically avoid such easy-to-find messages. For instance, it is possible for a developer to create a visually identical message box that doesn't use the built-in Windows message box facilities and that would therefore be far more difficult to track. In such case, you could let the program run until the message box was displayed and then attach a debugger to the process and examine the call stack for clues on where the program made the decision to display this particular message box.

Let's now find out how KeygenMe-3 displays its message box. As usual, you'll try to use OllyDbg as your reversing tool. Considering that this is supposed to be a relatively simple program to crack, Olly should be more than enough.

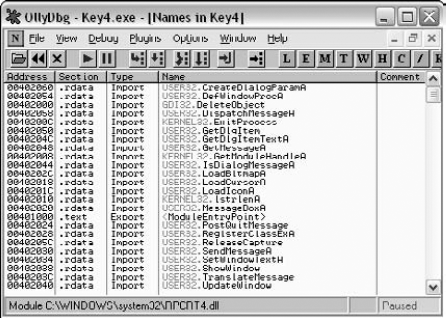

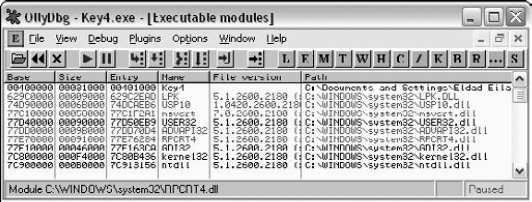

As soon as you open the program in OllyDbg, you go to the Executable Modules view to see which modules (DLLs) are statically linked to it. Figure 11.3 shows the Executable Modules view for KeygenMe-3.

Figure 11.3. OllyDbg's Executable Modules window showing the modules loaded in the key4.exe program.

This view immediately tells you the Key4.exe is a "lone gunner," apparently with no extra DLLs other than the system DLLs. You know this because other than the Key4.exe module, the rest of the modules are all operating system components. This is easy to tell because they are all in the C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32 directory, and also because at some point you just learn to recognize the names of the popular operating system components. Of course, if you're not sure it's always possible to just look up a binary executable's properties in Windows and obtain some details on it such as who created it and the like. For example, if you're not sure what LPK.DLL is, just go to C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32 and look up its properties. In the Version tab you can see its version resource information, which gives you some basic details on the executable (assuming such details were put in place by the module's author). Figure 11.4 shows the Version tab for lpk. from Windows XP Service Pack 2, and it is quite clearly an operating system component.

You can proceed to examine which APIs are directly called by Key4.exe by clicking View Names on Key4.exe in the Executable Modules window. This brings you to the list of functions imported and exported from Key4.exe. This screen is shown in Figure 11.5.

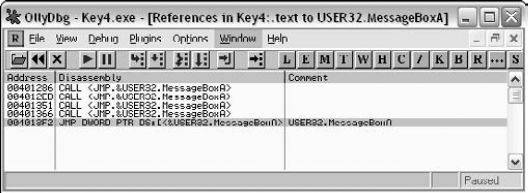

At the moment, you're interested in the Import entry titled USER32.MessageBoxA, because that could well be the call that generates the message box from Figure 11.2. OllyDbg lets you do several things with such an import entry, but my favorite feature, especially for a small program such as a crackme, is to just have Olly show all code references to the imported function. This provides an excellent way to find the call to the failure message box, and hopefully also to the success message box. You can select the MessageBoxA entry, click the right mouse button, and select Find References to get into the References to MessageBoxA dialog box. This dialog box is shown in Figure 11.6.

Here, you have all code references in Key4.exe to the MessageBoxA API. Notice that the last entry references the API with a JMP instruction instead of a CALL instruction. This is just the import entry for the API, and essentially all the other calls also go through this one. It is not relevant in the current discussion. You end up with four other calls that use the CALL instruction. Selecting any of the entries and pressing Enter shows you a disassembly of the code that calls the API. Here, you can also see which parameters were passed into the API, so you can quickly tell if you've found the right spot.

The first entry brings you to the About message box (from looking at the message text in OllyDbg). The second brings you to a parameter validation message box that says "Please Fill In 1 Char to Continue!!" The third entry brings you to what seems to be what you're looking for. Here's the code OllyDbg shows for the third MessageBoxA reference.

0040133F CMP EAX,ESI

00401341 JNZ SHORT Key4.00401358

00401343 PUSH 0

00401345 PUSH Key4.0040348C ; ASCII "KeygenMe #3"

0040134A PUSH Key4.004034DD ; Text = " Great, You are ranked as Level-3 at

Keygening now"

0040134F PUSH 0 ; hOwner = NULL

00401351 CALL <JMP.&USER32.MessageBoxA> ; MessageBoxA

00401356 JMP SHORT Key4.0040136B

00401358 PUSH 0 ; Style =

MB_OK|MB_APPLMODAL

0040135A PUSH Key4.0040348C ; Title = "KeygenMe #3"

0040135F PUSH Key4.004034AA ; Text = " You Have

Entered A Wrong Serial,

Please Try Again"

00401364 PUSH 0 ; hOwner = NULL

00401366 CALL <JMP.&USER32.MessageBoxA> ; MessageBoxA

0040136B JMP SHORT Key4.00401382Well, it appears that you've landed in the right place! This is a classic if-else sequence that displays one of two message boxes. If EAX == ESI the program shows the "Great, You are ranked as Level-3 at Keygening now" message, and if not it displays the "You Have Entered A Wrong Serial, Please Try Again" message. One thing we immediately attempt is to just patch the program so that it always acts as though EAX == ESI, and see if that gets us our success message.

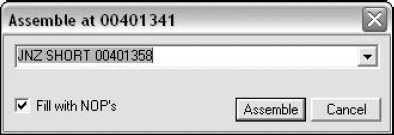

We do this by double clicking the JNZ instruction, which brings us to the Assemble dialog, which is shown in Figure 11.7.

The Assemble dialog allows you to modify code in the program by just typing the desired assembly language instructions. The Fill with NOPs option will add NOPs if the new instruction is shorter that the old one. This is an important point – working with machine code is not like a using word processor where you can insert and delete words and just shift all the materials that follow. Moving machine code, even by 1 byte, is a fairly complicated task because many references in assembly language are relative and moving code would invalidate such relative references. Olly doesn't even attempt that. If your instruction is shorter than the one it replaces Olly will add NOPs. If it's longer, the instruction that follows in the original code will be overwritten. In this case, you're not interested in ever getting to the error message at Key4.00401358, so you completely eliminate the jump from the program. You do this by typing NOP into the Assemble dialog box, with the Fill with NOPs option checked. This will make sure that Olly overwrites the entire instruction with NOPs.

Having patched the program, you can run it and see what happens. It's important to keep in mind that the patch is only applied to the debugged program and that it's not written back into the original executable (yet). This means that the only way to try out the patched program at the moment is by running it inside the debugger. You do that by pressing F9. As usual, you get the usual KeygenMe-3 dialog box, and you can just type random values into the two text boxes and click "OK". Success! The program now shows the success dialog box, as shown in Figure 11.8.

This concludes your first patching lesson. The fact is that simple programs that use a single if statement to control the availability of program functionality are quite common, and this technique can be applied to many of them. The only thing that can get somewhat complicated is the process of finding these if statements. KeygenMe-3 is a really tiny program. Larger programs might not use the stock MessageBox API or might have hundreds of calls to it, which can complicate things a great deal.

One point to keep in mind is that so far you've only patched the program inside the debugger. This means that to enjoy your crack you must run the program in OllyDbg. At this point, you must permanently patch the program's binary executable in order for the crack to be permanent. You do this by right-clicking the code area in the CPU window and selecting Copy to Executable, and then All Modifications in the submenu. This should create a new window that contains a new executable with the patches that you've done. Now all you must do is right-click that window, select Save File, and give OllyDbg a name for the new patched executable. That's it! OllyDbg is really a nice tool for simple cracking and patching tasks. One common cracking scenario where patching becomes somewhat more complicated is when the program performs checksum verification on itself in order to make sure that it hasn't been modified. In such cases, more work is required in order to properly patch a program, but fear not: It's always possible.

You may or may have not noticed it, but KeygenMe-3's success message was "Great, You are ranked as Level-3 at Keygening now," it wasn't "Great, you are ranked as level 3 at patching now." Crackmes have rules too, and typically creators of crackmes define how they should be dealt with. Some are meant to be patched, and others are meant to be keygenned. Keygennning is the process of creating programs that mimic the key-generation algorithm within a protection technology and essentially provide an unlimited number of valid keys, for everyone to use.

You might wonder why such a program is necessary in the first place. Shouldn't pirates be able to just share a single program key among all of them? The answer is typically no. The thing is that in order to create better protections developers of protection technologies typically avoid using algorithms that depend purely on user input—instead they generate keys based on a combination of user input and computer-specific information. The typical approach is to request the user's full name and to combine that with the primary hard drive partition's volume serial number.[1] The volume serial number is a 32-bit random number assigned to a partition while it is being formatted. Using the partition serial number means that a product key will only be valid on the computer on which it was installed—users can't share product keys.

To overcome this problem software pirates use keygen programs that typically contain exact replicas of the serial number generation algorithms in the protected programs. The keygen takes some kind of an input such as the volume serial number and a username, and produces a product key that the user must type into the protected program in order to activate it. Another variation uses a challenge, where the protected program takes the volume serial number and the username and generates a challenge, which is just a long number. The user is then given that number and is supposed to call the software vendor and ask for a valid product key that will be generated based on the supplied number. In such cases, a keygen would simply convert the challenge to the product key.

As its name implies, KeygenMe-3 was meant to be keygenned, so by patching it you were essentially cheating. Let's rectify the situation by creating a keygen for KeygenMe-3.

Ripping algorithms from copy protection products is often an easy and effective method for creating keygen programs. The idea is quite simple: Locate the function or functions within the protected program that calculate a valid serial number, and port them into your keygen. The beauty of this approach is that you just don't need to really understand the algorithm; you simply need to locate it and find a way to call it from your own program.

The initial task you must perform is to locate the key-generation algorithm within the crackme. There are many ways to do this, but one the rarely fails is to look for the code that reads the contents of the two edit boxes into which you're typing the username and serial number. Assuming that KeygenMe-3's main screen is a dialog box (and this can easily be verified by looking for one of the dialog box creation APIs in the program's initialization code), it is likely that the program would use GetDlgItemText or that it would send the edit box a WM_GETTEXT message. Working under the assumption that it's GetDlgItemText you're after, you can go back to the Names window in OllyDbg and look for references to GetDlgItemTextA or GetDlgItemTextW. As expected, you will find that the program is calling GetDlgItemTextA, and in opening the Find References to Import window, you find two calls into the API (not counting the direct JMP, which is the import address table entry).

Example 11.1. Conversion algorithm for first input field in KeygenMe-3.

004012B1 PUSH 40 ; Count = 40 (64.) 004012B3 PUSH Key4.0040303F ; Buffer = Key4.0040303F 004012B8 PUSH 6A ; ControlID = 6A (106.) 004012BA PUSH DWORD PTR [EBP+8] ; hWnd 004012BD CALL <JMP.&USER32.GetDlgItemTextA> ; GetDlgItemTextA 004012C2 CMP EAX,0 004012C5 JE SHORT Key4.004012DF 004012C7 PUSH 40 ; Count = 40 (64.) 004012C9 PUSH Key4.0040313F ; Buffer = Key4.0040313F 004012CE PUSH 6B ; ControlID = 6B (107.) 004012D0 PUSH DWORD PTR [EBP+8] ; hWnd

004012D3 CALL <JMP.&USER32.GetDlgItemTextA> ; GetDlgItemTextA

004012D8 CMP EAX,0

004012DB JE SHORT Key4.004012DF

004012DD JMP SHORT Key4.004012F6

004012DF PUSH 0 ; Style =

MB_OK|MB_APPLMODAL004012E1

PUSH Key4.0040348C ; Title = "KeygenMe #3"

004012E6 PUSH Key4.00403000 ; Text = " Please

Fill In 1 Char to

Continue!!"

004012EB PUSH 0 ; hOwner = NULL

004012ED CALL <JMP.&USER32.MessageBoxA> ; MessageBoxA

004012F2 LEAVE

004012F3 RET 10

004012F6 PUSH Key4.0040303F ; String = "Eldad Eilam"

004012FB CALL <JMP.&KERNEL32.lstrlenA> ; lstrlenA

00401300 XOR ESI,ESI

00401302 XOR EBX,EBX

00401304 MOV ECX,EAX

00401306 MOV EAX,1

0040130B MOV EBX,DWORD PTR [40303F]

00401311 MOVSX EDX,BYTE PTR [EAX+40351F]

00401318 SUB EBX,EDX

0040131A IMUL EBX,EDX

0040131D MOV ESI,EBX

0040131F SUB EBX,EAX

00401321 ADD EBX,4353543

00401327 ADD ESI,EBX

00401329 XOR ESI,EDX

0040132B MOV EAX,4

00401330 DEC ECX

00401331 JNZ SHORT Key4.0040130B

00401333 PUSH ESI

00401334 PUSH Key4.0040313F ; ASCII "12345"

00401339 CALL Key4.00401388

0040133E POP ESI

0040133F CMP EAX,ESIBefore attempting to rip the conversion algorithm from the preceding code, let's also take a look at the function at Key4.00401388, which is apparently a part of the algorithm.

Example 11.2. Conversion algorithm for second input field in KeygenMe-3.

00401388 PUSH EBP 00401389 MOV EBP,ESP 0040138B PUSH DWORD PTR [EBP+8] ; String

0040138E CALL <JMP.&KERNEL32.lstrlenA> ; lstrlenA 00401393 PUSH EBX 00401394 XOR EBX,EBX 00401396 MOV ECX,EAX 00401398 MOV ESI,DWORD PTR [EBP+8] 0040139B PUSH ECX 0040139C XOR EAX,EAX 0040139E LODS BYTE PTR [ESI] 0040139F SUB EAX,30 004013A2 DEC ECX 004013A3 JE SHORT Key4.004013AA 004013A5 IMUL EAX,EAX,0A 004013A8 LOOPD SHORT Key4.004013A5 004013AA ADD EBX,EAX 004013AC POP ECX 004013AD LOOPD SHORT Key4.0040139B 004013AF MOV EAX,EBX 004013B1 POP EBX 004013B2 LEAVE 004013B3 RET 4

From looking at the code, it is evident that there are two code areas that appear to contain the key-generation algorithm. The first is the Key4.0040130B section in Listing 11.1, and the second is the entire function from Listing 11.2. The part from Listing 11.2. The part from Listing 11.1 generates the value in ESI, and the function from Listing 11.1 generates the value in ESI, and the function from Listing 11.2 returns a value into EAX. The two values are compared and must be equal for the program to report success (this is the comparison that we patched earlier).

Let's start by determining the input data required by the snippet at Key4.0040130B. This code starts out with ECX containing the length of the first input string (the one from the top text box), with the address to that string (40303F), and with the unknown, hard-coded address 40351F. The first thing to notice is that the sequence doesn't actually go over each character in the string. Instead, it takes the first four characters and treats them as a single double-word. In order to move this code into your own keygen, you have to figure out what is stored in 40351F. First of all, you can see that the address is always added to EAX before it is referenced. In the initial iteration EAX equals 1, so the actual address that is accessed is 403520. In the following iterations EAX is set to 4, so you're now looking at 403524. From dumping 403520 in OllyDbg, you can see that this address contains the following data:

00403520 25 40 24 65 72 77 72 23 %@$erwr#

Notice that the line that accesses this address is only using a single byte, and not whole DWORDs, so in reality the program is only accessing the first (which is 0x25) and the fourth byte (which is 0x65).

In looking at the first algorithm from Listing 11.1, it is quite obvious that this is some kind of key-generation algorithm that converts a username into a 32-bit number (that ends up in ESI). What about the second algorithm from Listing 11.1, it is quite obvious that this is some kind of key-generation algorithm that converts a username into a 32-bit number (that ends up in ESI). What about the second algorithm from Listing 11.2? A quick observation shows that the code doesn't have any complex processing. All it does is go over each digit in the serial number, subtract it from 0x30 (which happens to be the digit '0' in ASCII), and repeatedly multiply the result by 10 until ECX gets to zero. This multiplication happens in an inner loop for each digit in the source string. The number of multiplications is determined by the digit's position in the source string.

Stepping through this code in the debugger will show what experienced reversers can detect by just looking at this function. It converts the string that was passed in the parameter to a binary DWORD. This is equivalent to the atoi function from the C runtime library, but it appears to be a private implementation (atoi is somewhat more complicated, and while OllyDbg is capable of identifying library functions if it is given a library to work with, it didn't seem to find anything in KeygenMe-3).

So, it seems that the first algorithm (from Listing 11.1) converts the username into a 32-bit DWORD using a special algorithm, and that the second algorithm simply converts digits from the lower text box. The lower text box should contain the number produced by the first algorithm. In light of this, it would seem that all you need to do is just rip the first algorithm into the keygen program and have it generate a serial number for us. Let's try that out.

Listing 11.3 shows the ported routine I created for the keygen program. It is essentially a C function (compiled using the Microsoft C/C++ compiler), with an inline assembler sequence that was copied from the OllyDbg disassembler. The instructions written in lowercase were all manually added, as was the name LoopStart.

Example 11.3. Ported conversion algorithm for first input field from KeygenMe-3.

ULONG ComputeSerial(LPSTR pszString)

{ DWORD dwLen = lstrlen(pszString);

_asm

{ mov ecx, [dwLen]

mov edx, 0x25

mov eax, 1

LoopStart:

MOV EBX, DWORD PTR [pszString]

mov ebx, dword ptr [ebx]

//MOVSX EDX, BYTE PTR DS:[EAX+40351F]SUB EBX, EDX

IMUL EBX, EDX

MOV ESI, EBX

SUB EBX, EAX

ADD EBX, 0x4353543

ADD ESI, EBX

XOR ESI, EDX

MOV EAX, 4

mov edx, 0x65

DEC ECX

JNZ LoopStart

mov eax, ESI

}

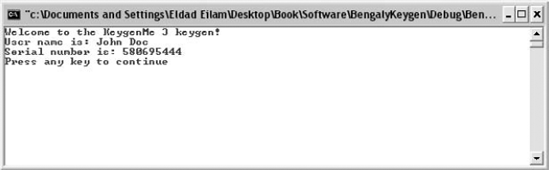

}I inserted this function into a tiny console mode application I created that takes the username as an input and shows ComputeSerial's return value in decimal. All it does is call ComputeSerial and display its return value in decimal. Here's the entry point for my keygen program.

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

printf ("Welcome to the KeygenMe-3 keygen!\n");

printf ("User name is: %s\n", argv[1]);

printf ("Serial number is: %u\n", ComputeSerial(argv[1]));

return 0;

}It would appear that typing any name into the top text box (this should be the same name passed to ComputeSerial) and then typing ComputeSerial's return value into the second text box in KeygenMe-3 should satisfy the program. Let's try that out. You can pass "John Doe" as a parameter for our keygen, and record the generated serial number. Figure 11.9 shows the output screen from our keygen.

The resulting serial number appears to be 580695444. You can run KeygenMe-3 (the original, unpatched version), and type "John Doe" in the first edit box and "580695444" in the second box. Success again! KeygenMe-3 accepts the values as valid values. Congratulations, this concludes your second cracking lesson.

Having a decent grasp of basic protection concepts, it's time to get your hands dirty and attempt to crack your way through a more powerful protection. For this purpose, I have created a special crackme that you'll use here. This crackme is called Defender and was specifically created to demonstrate several powerful protection techniques that are similar to what you would find in real-world, commercial protection technologies. Be forewarned: If you've never confronted a serious protection technology before Defender, it might seem impossible to crack. It is not; all it takes is a lot of knowledge and a lot of patience.

Note

Defender is tightly integrated with the underlying operating system and was specifically designed to run on NT-based Windows systems. It runs on all currently available NT-based systems, including Windows XP, Windows Server 2003, Windows 2000, and Windows NT 4.0, but it will not run on non-NT-based systems such as Windows 98 or Windows Me.

Let's begin by just running Defender.EXE and checking to see what happens. Note that Defender is a console-mode application, so it should generally be run from a Command Prompt window. I created Defender as a console-mode application because it greatly simplified the program. It would have been possible to create an equally powerful protection in a regular GUI application, but that would have taken longer to write. One thing that's important to note is that a console mode application is not a DOS program! NT-based systems can run DOS programs using the NTVDM virtual machine, but that's not the case here. Console-mode applications such as Defender are regular 32-bit Windows programs that simply avoid the Windows GUI APIs (but have full access to the Win32 API), and communicate with the user using a simple text window.

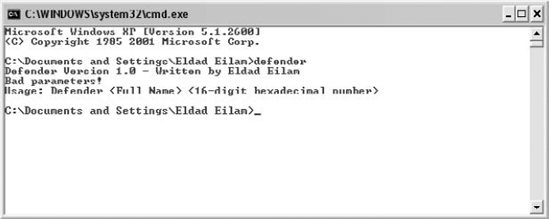

You can run Defender.EXE from the Command Prompt window and receive the generic usage message. Figure 11.10 shows Defender's default usage message.

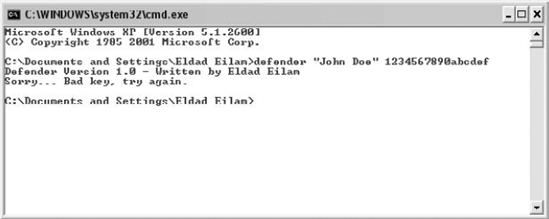

Defender takes a username and a 16-digit hexadecimal serial number. Just to see what happens, let's try feeding it some bogus values. Figure 11.11 shows how Defender respond to John Doe as a username and 1234567890ABCDEF as the serial number.

Well, no real drama here—Defender simply reports that we have a bad serial number. One good reason to always go through this step when cracking is so that you at least know what the failure message looks like. You should be able to find this message somewhere in the executable.

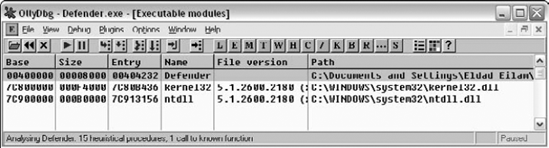

Let's load Defender.EXE into OllyDbg and take a first look at it. The first thing you should do is look at the Executable Modules window to see which DLLs are statically linked to Defender. Figure 11.12 shows the Executable Modules window for Defender.

Figure 11.11. Defender.EXE launched with John Doe as the username and 1234567890ABCDEF as the serial number.

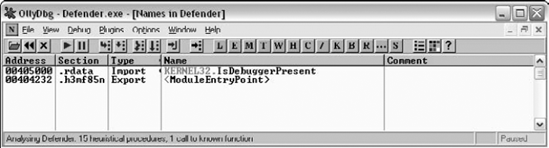

Very short list indeed—only NTDLL.DLL and KERNEL32.DLL. Remember that our GUI crackme, KeygenMe-3 had a much longer list, but then again Defender is a console-mode application. Let's proceed to the Names window to determine which APIs are called by Defender. Figure 11.13 shows the Names window for Defender.EXE.

Very strange indeed. It would seem that the only API called by Defender.EXE is IsDebuggerPresent from KERNEL32.DLL. It doesn't take much reasoning to figure out that this is unlikely to be true. The program must be able to somehow communicate with the operating system, beyond just calling IsDebuggerPresent. For example, how would the program print out messages to the console window without calling into the operating system? That's just not possible. Let's run the program through DUMPBIN and see what it has to say about Defender's imports. Listing 11.4 shows DUMPBIN's output when it is launched with the /IMPORTS option.

Example 11.4. Output from DUMPBIN when run on Defender.EXE with the /IMPORTS option.

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 7.10.3077 Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. Dump of file defender.exe

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

Section contains the following imports:

KERNEL32.dll

405000 Import Address Table

405030 Import Name Table

0 time date stamp

0 Index of first forwarder reference

22F IsDebuggerPresent

Summary

1000 .data

4000 .h3mf85n

1000 .h477w81

1000 .rdataNot much news here. DUMPBIN is also claiming the Defender.EXE is only calling IsDebuggerPresent. One slightly interesting thing however is the Summary section, where DUMPBIN lists the module's sections. It would appear that Defender doesn't have a .text section (which is usually where the code is placed in PE executables). Instead it has two strange sections: .h3mf85n and .h477w81. This doesn't mean that the program doesn't have any code, it simply means that the code is most likely tucked in one of those oddly named sections.

At this point it would be wise to run DUMPBIN with the /HEADERS option to get a better idea of how Defender is built (see Listing 11.5).

Example 11.5. Output from DUMPBIN when run on Defender.EXE with the /HEADERS option.

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 7.10.3077

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Dump of file defender.exe

PE signature found

File Type: EXECUTABLE IMAGE

FILE HEADER VALUES

14C machine (x86)4 number of sections

4129382F time date stamp Mon Aug 23 03:19:59 2004

0 file pointer to symbol table

0 number of symbols

E0 size of optional header

10F characteristics

Relocations stripped

Executable

Line numbers stripped

Symbols stripped

32 bit word machine

OPTIONAL HEADER VALUES

10B magic # (PE32)

7.10 linker version

3400 size of code

600 size of initialized data

0 size of uninitialized data

4232 entry point (00404232)

1000 base of code

5000 base of data

400000 image base (00400000 to 00407FFF)

1000 section alignment

200 file alignment

4.00 operating system version

0.00 image version

4.00 subsystem version

0 Win32 version

8000 size of image

400 size of headers

0 checksum

3 subsystem (Windows CUI)

400 DLL characteristics

No safe exception handler

100000 size of stack reserve

1000 size of stack commit

100000 size of heap reserve

1000 size of heap commit

0 loader flags

10 number of directories

5060 [ 35] RVA [size] of Export Directory

5008 [ 28] RVA [size] of Import Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Resource Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Exception Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Certificates Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Base Relocation Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Debug Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Architecture Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Global Pointer Directory0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Thread Storage Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Load Configuration Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Bound Import Directory

5000 [ 8] RVA [size] of Import Address Table Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Delay Import Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of COM Descriptor Directory

0 [ 0] RVA [size] of Reserved Directory

SECTION HEADER #1

.h3mf85n name

3300 virtual size

1000 virtual address (00401000 to 004042FF)

3400 size of raw data

400 file pointer to raw data (00000400 to 000037FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

E0000020 flags

Code

Execute Read Write

SECTION HEADER #2

.rdata name

95 virtual size

5000 virtual address (00405000 to 00405094)

200 size of raw data

3800 file pointer to raw data (00003800 to 000039FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers40000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Only

SECTION HEADER #3

.data name

24 virtual size

6000 virtual address (00406000 to 00406023)

0 size of raw data

0 file pointer to raw data

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbersC0000040 flags

Initialized DataRead Write

SECTION HEADER #4.

h477w81 name

8C virtual size

7000 virtual address (00407000 to 0040708B)

200 size of raw data

3A00 file pointer to raw data (00003A00 to 00003BFF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

C0000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Write

Summary

1000 .data

4000 .h3mf85n

1000 .h477w81

1000 .rdataThe /HEADERS options provides you with a lot more details on the program. For example, it is easy to see that section #1, .h3mf85n, is the code section. It is specified as Code, and the program's entry point resides in it (the entry point is at 404232 and .h3mf85n starts at 401000 and ends at 4042FF, so the entry point is clearly inside this section). The other oddly named section, .h477w81 appears to be a small data section, probably containing some variables. It's also worth mentioning that the subsystem flag equal 3. This identifies a Windows CUI (console user interface) program, and Windows will automatically create a console window for this program as soon as it is started.

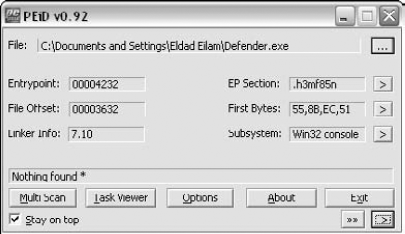

All of those oddly named sections indicate that the program is possible packed in some way. Packers have a way of creating special sections that contain the packed code or the unpacking code. It is a good idea to run the program in PEiD to see if it is packed with a known packer. PEiD is a program that can identify popular executable signatures and show whether an executable has been packed by one of the popular executable packers or copy protection products. PEiD can be downloaded from http://peid.has.it/Defender.EXE.

Unfortunately, PEiD reports "Nothing found," so you can safely assume that Defender is either not packed or that it is packed with an unknown packer. Let's proceed to start disassembling the program and figuring out where that "Sorry . . . Bad key, try again." message is coming from.

Because the program doesn't appear to directly call any APIs, there doesn't seem to be a specific API on which you could place a breakpoint to catch the place in the code where the program is printing this message. Thus you don't really have a choice but to try your luck by examining the program's entry point and trying to find some interesting code that might shed some light on this program. Let's load the program in IDA and run a full analysis on it. You can now take a quick look at the program's entry point.

Example 11.6. A disassembly of Defender's entry point function, generated by IDA.

.h3mf85n:00404232 start proc near

.h3mf85n:00404232

.h3mf85n:00404232 var_8 = dword ptr −8

.h3mf85n:00404232 var_4 = dword ptr −4

.h3mf85n:00404232

.h3mf85n:00404232 push ebp.

h3mf85n:00404233 mov ebp, esp.

h3mf85n:00404235 push ecx

.h3mf85n:00404236 push ecx

.h3mf85n:00404237 push esi

.h3mf85n:00404238 push edi

.h3mf85n:00404239 call sub_402EA8

.h3mf85n:0040423E push eax

.h3mf85n:0040423F call loc_4033D1

.h3mf85n:00404244 mov eax, dword_406000

.h3mf85n:00404249 pop ecx

.h3mf85n:0040424A mov ecx, eax

.h3mf85n:0040424C mov eax, [eax]

.h3mf85n:0040424E mov edi, 6DEF20h

.h3mf85n:00404253 xor esi, esi

.h3mf85n:00404255 jmp short loc_404260

.h3mf85n:00404257 ; -----------------------------------------.h3mf85n:00404257 .h3mf85n:00404257 loc_404257: ; CODE XREF: start+30↓j .h3mf85n:00404257 cmp eax, edi .h3mf85n:00404259 jz short loc_404283 .h3mf85n:0040425B add ecx, 8 .h3mf85n:0040425E mov eax, [ecx] .h3mf85n:00404260 .h3mf85n:00404260 loc_404260: ; CODE XREF: start+23_j .h3mf85n:00404260 cmp eax, esi .h3mf85n:00404262 jnz short loc_404257 .h3mf85n:00404264 xor eax, eax .h3mf85n:00404266 .h3mf85n:00404266 loc_404266: ; CODE XREF: start+5A_j .h3mf85n:00404266 lea ecx, [ebp+var_8] .h3mf85n:00404269 push ecx .h3mf85n:0040426A push esi .h3mf85n:0040426B mov [ebp+var_8], esi .h3mf85n:0040426E mov [ebp+var_4], esi .h3mf85n:00404271 call eax .h3mf85n:00404273 call loc_404202 .h3mf85n:00404278 mov eax, dword_406000 .h3mf85n:0040427D mov ecx, eax .h3mf85n:0040427F mov eax, [eax] .h3mf85n:00404281 jmp short loc_404297 .h3mf85n:00404283 ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:00404283. h3mf85n:00404283 loc_404283: ; CODE XREF: start+27_j .h3mf85n:00404283 mov eax, [ecx+4] .h3mf85n:00404286 add eax, dword_40601C .h3mf85n:0040428C jmp short loc_404266 .h3mf85n:0040428E ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:0040428E.h3mf85n:0040428E loc_40428E: ; CODE XREF: start+67_j .h3mf85n:0040428E cmp eax, edi .h3mf85n:00404290 jz short loc_4042BA .h3mf85n:00404292 add ecx, 8 .h3mf85n:00404295 mov eax, [ecx] .h3mf85n:00404297 .h3mf85n:00404297 loc_404297: ; CODE XREF: start+4F_j .h3mf85n:00404297 cmp eax, esi .h3mf85n:00404299 jnz short loc_40428E .h3mf85n:0040429B xor eax, eax .h3mf85n:0040429D .h3mf85n:0040429D loc_40429D: ; CODE XREF: start+91_j .h3mf85n:0040429D lea ecx, [ebp+var_8] .h3mf85n:004042A0 push ecx .h3mf85n:004042A1 push esi .h3mf85n:004042A2 mov [ebp+var_8], esi

.h3mf85n:004042A5 mov [ebp+var_4], esi .h3mf85n:004042A8 call eax .h3mf85n:004042AA call loc_401746 .h3mf85n:004042AF mov eax, dword_406000 .h3mf85n:004042B4 mov ecx, eax .h3mf85n:004042B6 mov eax, [eax] .h3mf85n:004042B8 jmp short loc_4042CE .h3mf85n:004042BA ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:004042BA .h3mf85n:004042BA loc_4042BA: ; CODE XREF: start+5E_j .h3mf85n:004042BA mov eax, [ecx+4] .h3mf85n:004042BD add eax, dword_40601C .h3mf85n:004042C3 jmp short loc_40429D .h3mf85n:004042C5 ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:004042C5 .h3mf85n:004042C5 loc_4042C5: ; CODE XREF: start+9E_j .h3mf85n:004042C5 cmp eax, edi .h3mf85n:004042C7 jz short loc_4042F5 .h3mf85n:004042C9 add ecx, 8 .h3mf85n:004042CC mov eax, [ecx] .h3mf85n:004042CE .h3mf85n:004042CE loc_4042CE: ; CODE XREF: start+86_j .h3mf85n:004042CE cmp eax, esi .h3mf85n:004042D0 jnz short loc_4042C5 .h3mf85n:004042D2 xor ecx, ecx .h3mf85n:004042D4 .h3mf85n:004042D4 loc_4042D4: ; CODE XREF: start+CC_j .h3mf85n:004042D4 lea eax, [ebp+var_8] .h3mf85n:004042D7 push eax .h3mf85n:004042D8 push esi .h3mf85n:004042D9 mov [ebp+var_8], esi .h3mf85n:004042DC mov [ebp+var_4], esi .h3mf85n:004042DF call ecx .h3mf85n:004042E1 call loc_402082 .h3mf85n:004042E6 call ds:IsDebuggerPresent .h3mf85n:004042EC xor eax, eax .h3mf85n:004042EE pop edi .h3mf85n:004042EF inc eax .h3mf85n:004042F0 pop esi .h3mf85n:004042F1 leave .h3mf85n:004042F2 retn 8 .h3mf85n:004042F5 ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:004042F5 .h3mf85n:004042F5 loc_4042F5: ; CODE XREF: start+95_j .h3mf85n:004042F5 mov ecx, [ecx+4] .h3mf85n:004042F8 add ecx, dword_40601C .h3mf85n:004042FE jmp short loc_4042D4 .h3mf85n:004042FE start endp

Listing 11.6 shows Defender's entry point function. A quick scan of the fuction reveals one important property—the entry point is not a common runtime library initialization routine. Even if you've never seen a runtime library initialization routine before, you can be pretty sure that it doesn't end with a call to IsDebuggerPresent. While we're on that call, look at how EAX is being XORed against itself as soon as it returns—its return value is being ignored! A quick look in http://msdn.microsoft.com shows us that IsDebuggerPresent should return a Boolean specifying whether a debugger is present or not. XORing EAX right after this API returns means that the call is meaningless.

Anyway, let's go back to the top of Listing 11.6 and learn something about Defender, starting with a call to 402EA8. Let's take a look at what it does.

mf85n:00402EA8 sub_402EA8 proc near

.h3mf85n:00402EA8

.h3mf85n:00402EA8 var_4 = dword ptr −4

.h3mf85n:00402EA8

.h3mf85n:00402EA8 push ecx

.h3mf85n:00402EA9 mov eax, large fs:30h

.h3mf85n:00402EAF mov [esp+4+var_4], eax

.h3mf85n:00402EB2 mov eax, [esp+4+var_4]

.h3mf85n:00402EB5 mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

.h3mf85n:00402EB8 mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

.h3mf85n:00402EBB mov eax, [eax]

.h3mf85n:00402EBD mov eax, [eax+18h]

.h3mf85n:00402EC0 pop ecx

.h3mf85n:00402EC1 retn

.h3mf85n:00402EC1 sub_402EA8 endpThe preceding routine starts out with an interesting sequence that loads a value from fs:30h. Generally in NT-based operating systems the fs register is used for accessing thread local information. For any given thread, fs:0 points to the local TEB (Thread Environment Block) data structure, which contains a plethora of thread-private information required by the system during runtime. In this case, the function is accessing offset +30. Luckily, you have detailed symbolic information in Windows from which you can obtain information on what offset +30 is in the TEB. You can do that by loading symbols for NTDLL in WinDbg and using the DT command (for more information on WinDbg and the DT command go to the Microsoft Debugging Tools Web page at www.microsoft.com/whdc/devtools/debugging/default.mspx).

The structure listing for the TEB is quite long, so I'll just list the first part of it, up to offset +30, which is the one being accessed by the program.

+0x000 NtTib : _NT_TIB +0x01c EnvironmentPointer : Ptr32 Void +0x020 ClientId : _CLIENT_ID +0x028 ActiveRpcHandle : Ptr32 Void

+0x02c ThreadLocalStoragePointer : Ptr32 Void +0x030 ProcessEnvironmentBlock : Ptr32 _PEB . .

It's obvious that the first line is accessing the Process Environment Block through the TEB. The PEB is the process-information data structure in Windows, just like the TEB is the thread information data structure. In address 00402EB5 the program is accessing offset +c in the PEB. Let's look at what's in there. Again, the full definition is quite long, so I'll just print the beginning of the definition.

+0x000 InheritedAddressSpace : UChar +0x001 ReadImageFileExecOptions : UChar +0x002 BeingDebugged : UChar +0x003 SpareBool : UChar +0x004 Mutant : Ptr32 Void +0x008 ImageBaseAddress : Ptr32 Void +0x00c Ldr : Ptr32 _PEB_LDR_DATA..

In this case, offset +c goes to the _PEB_LDR_DATA, which is the loader information. Let's take a look at this data structure and see what's inside.

+0x000 Length : Uint4B +0x004 Initialized : UChar +0x008 SsHandle : Ptr32 Void +0x00c InLoadOrderModuleList : _LIST_ENTRY +0x014 InMemoryOrderModuleList : _LIST_ENTRY +0x01c InInitializationOrderModuleList : _LIST_ENTRY +0x024 EntryInProgress : Ptr32 Void

This data structure appears to be used for managing the loaded executables within the current process. There are several module lists, each containing the currently loaded executable modules in a different order. The function is taking offset +c, which means that it's going after the InLoadOrderModuleList item. Let's take a look at the module data structure, LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY, and try to understand what this function is looking for.

Note

The following definition for LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY was produced using the DT command in WinDbg. Some Windows symbol files actually contain data structure definitions that can be dumped using that command. All you need to do is type DT ModuleName!* to get a list of all available names, and then type DT ModuleName!StructureName to get a nice listing of its members!

+0x000 InLoadOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY +0x008 InMemoryOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY +0x010 InInitializationOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY +0x018 DllBase : Ptr32 Void +0x01c EntryPoint : Ptr32 Void +0x020 SizeOfImage : Uint4B +0x024 FullDllName : _UNICODE_STRING +0x02c BaseDllName : _UNICODE_STRING +0x034 Flags : Uint4B +0x038 LoadCount : Uint2B +0x03a TlsIndex : Uint2B +0x03c HashLinks : _LIST_ENTRY +0x03c SectionPointer : Ptr32 Void +0x040 CheckSum : Uint4B +0x044 TimeDateStamp : Uint4B +0x044 LoadedImports : Ptr32 Void +0x048 EntryPointActivationContext : Ptr32 _ACTIVATION_CONTEXT +0x04c PatchInformation : Ptr32 Void

After getting a pointer to InLoadOrderModuleList the function appears to go after offset +0 in the first module. From looking at this structure, it would seem that offset +0 is part of the LIST_ENTRY data structure. Let's dump LIST_ENTRY and see what offset +0 means.

+0x000 Flink : Ptr32 _LIST_ENTRY +0x004 Blink : Ptr32 _LIST_ENTRY

Offset +0 is Flink, which probably stands for "forward link". This means that the function is hard-coded to skip the first entry, regardless of what it is. This is quite unusual because with a linked list you would expect to see a loop—no loop, the function is just hard-coded to skip the first entry. After doing that, the function simply returns the value from offset +18 at the second entry. Offset +18 in _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY is DllBase. So, it would seem that all this function is doing is looking for the base of some DLL. At this point it would be wise to load Defender.EXE in WinDbg, just to take a look at the loader information and see what the second module is. For this, you use the !dlls command, which dumps a (relatively) user-friendly view of the loader data structures. The –l option makes the command dump modules in their load order, which is essentially the list you traversed by taking InLoadOrderModuleList from PEB_LDR_DATA.

0:000> !dlls -l

0x00241ee0: C:\Documents and Settings\Eldad Eilam\Defender.exe

Base 0x00400000 EntryPoint 0x00404232 Size 0x00008000

Flags 0x00005000 LoadCount 0x0000ffff TlsIndex 0x00000000

LDRP_LOAD_IN_PROGRESS

LDRP_ENTRY_PROCESSED0x00241f48: C:\WINDOWS\system32\ntdll.dll

Base 0x7c900000 EntryPoint 0x7c913156 Size 0x000b0000

Flags 0x00085004 LoadCount 0x0000ffff TlsIndex 0x00000000

LDRP_IMAGE_DLL

LDRP_LOAD_IN_PROGRESS

LDRP_ENTRY_PROCESSED

LDRP_PROCESS_ATTACH_CALLED

0x00242010: C:\WINDOWS\system32\kernel32.dll

Base 0x7c800000 EntryPoint 0x7c80b436 Size 0x000f4000

Flags 0x00085004 LoadCount 0x0000ffff TlsIndex 0x00000000

LDRP_IMAGE_DLL

LDRP_LOAD_IN_PROGRESS

LDRP_ENTRY_PROCESSED

LDRP_PROCESS_ATTACH_CALLEDSo, it would seem that the second module is NTDLL.DLL. The function at 00402EA8 simply obtains the address of NTDLL.DLL in memory. This makes a lot of sense because as I've said before, it would be utterly impossible for the program to communicate with the user without any kind of interface to the operating system. Obtaining the address of NTDLL.DLL is apparently the first step in creating such an interface.

If you go back to Listing 11.6, you see that the return value from 00402EA8 is passed right into 004033D1, which is the next function being called. Let's take a look at it.

Example 11.7. A disassembly of function 4033D1 from Defender, generated by IDA Pro.

loc_4033D1:

.h3mf85n:004033D1 push ebp

.h3mf85n:004033D2 mov ebp, esp

.h3mf85n:004033D4 sub esp, 22Ch

.h3mf85n:004033DA push ebx

.h3mf85n:004033DB push esi

.h3mf85n:004033DC push edi

.h3mf85n:004033DD push offset dword_4034DD

.h3mf85n:004033E2 pop eax

.h3mf85n:004033E3 mov [ebp-20h], eax

.h3mf85n:004033E6 push offset loc_4041FD

.h3mf85n:004033EB pop eax

.h3mf85n:004033EC mov [ebp-18h], eax

.h3mf85n:004033EF mov eax, offset dword_4034E5

.h3mf85n:004033F4 mov ds:dword_4034D6, eax

.h3mf85n:004033FA mov dword ptr [ebp-8], 1

.h3mf85n:00403401 cmp dword ptr [ebp-8], 0

.h3mf85n:00403405 jz short loc_40346D

.h3mf85n:00403407 mov eax, [ebp-18h]

.h3mf85n:0040340A sub eax, [ebp-20h]

.h3mf85n:0040340D mov [ebp-30h], eax.h3mf85n:00403410 mov eax, [ebp-20h] .h3mf85n:00403413 mov [ebp-34h], eax .h3mf85n:00403416 and dword ptr [ebp-24h], 0 .h3mf85n:0040341A and dword ptr [ebp-28h], 0 .h3mf85n:0040341E loc_40341E: ; CODE XREF: .h3mf85n:00403469_j .h3mf85n:0040341E cmp dword ptr [ebp-30h], 3 .h3mf85n:00403422 jbe short loc_40346B .h3mf85n:00403424 mov eax, [ebp-34h] .h3mf85n:00403427 mov eax, [eax] .h3mf85n:00403429 mov [ebp-2Ch], eax .h3mf85n:0040342C mov eax, [ebp-34h] .h3mf85n:0040342F mov eax, [eax] .h3mf85n:00403431 xor eax, 2BCA6179h .h3mf85n:00403436 mov ecx, [ebp-34h] .h3mf85n:00403439 mov [ecx], eax .h3mf85n:0040343B mov eax, [ebp-34h] .h3mf85n:0040343E mov eax, [eax] .h3mf85n:00403440 xor eax, [ebp-28h] .h3mf85n:00403443 mov ecx, [ebp-34h] .h3mf85n:00403446 mov [ecx], eax .h3mf85n:00403448 mov eax, [ebp-2Ch] .h3mf85n:0040344B mov [ebp-28h], eax .h3mf85n:0040344E mov eax, [ebp-24h] .h3mf85n:00403451 xor eax, [ebp-2Ch] .h3mf85n:00403454 mov [ebp-24h], eax .h3mf85n:00403457 mov eax, [ebp-34h] .h3mf85n:0040345A add eax, 4 .h3mf85n:0040345D mov [ebp-34h], eax .h3mf85n:00403460 mov eax, [ebp-30h] .h3mf85n:00403463 sub eax, 4 .h3mf85n:00403466 mov [ebp-30h], eax .h3mf85n:00403469 jmp short loc_40341E .h3mf85n:0040346B ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:0040346B .h3mf85n:0040346B loc_40346B: ; CODE XREF: .h3mf85n:00403422_j .h3mf85n:0040346B jmp short near ptr unk_4034D5 .h3mf85n:0040346D ; ---------------------------------------------------- .h3mf85n:0040346D .h3mf85n:0040346D loc_40346D: ; CODE XREF: .h3mf85n:00403405_j .h3mf85n:0040346D mov eax, [ebp-18h] .h3mf85n:00403470 sub eax, [ebp-20h] .h3mf85n:00403473 mov [ebp-40h], eax .h3mf85n:00403476 mov eax, [ebp-20h] .h3mf85n:00403479 mov [ebp-44h], eax .h3mf85n:0040347C and dword ptr [ebp-38h], 0 .h3mf85n:00403480 and dword ptr [ebp-3Ch], 0 .h3mf85n:00403484 .h3mf85n:00403484 loc_403484: ; CODE XREF: .h3mf85n:004034CB_j .h3mf85n:00403484 cmp dword ptr [ebp-40h], 3

.h3mf85n:00403488 jbe short loc_4034CD

.h3mf85n:0040348A mov eax, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:0040348D mov eax, [eax]

.h3mf85n:0040348F xor eax, [ebp-3Ch]

.h3mf85n:00403492 mov ecx, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:00403495 mov [ecx], eax

.h3mf85n:00403497 mov eax, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:0040349A mov eax, [eax]

.h3mf85n:0040349C xor eax, 2BCA6179h

.h3mf85n:004034A1 mov ecx, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:004034A4 mov [ecx], eax

.h3mf85n:004034A6 mov eax, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:004034A9 mov eax, [eax]

.h3mf85n:004034AB mov [ebp-3Ch], eax

.h3mf85n:004034AE mov eax, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:004034B1 mov ecx, [ebp-38h]

.h3mf85n:004034B4 xor ecx, [eax]

.h3mf85n:004034B6 mov [ebp-38h], ecx

.h3mf85n:004034B9 mov eax, [ebp-44h]

.h3mf85n:004034BC add eax, 4

.h3mf85n:004034BF mov [ebp-44h], eax

.h3mf85n:004034C2 mov eax, [ebp-40h]

.h3mf85n:004034C5 sub eax, 4

.h3mf85n:004034C8 mov [ebp-40h], eax

.h3mf85n:004034CB jmp short loc_403484

.h3mf85n:004034CD ; ----------------------------------------------------

.h3mf85n:004034CD

.h3mf85n:004034CD loc_4034CD: ; CODE XREF: .h3mf85n:00403488_j

.h3mf85n:004034CD mov eax, [ebp-38h]

.h3mf85n:004034D0 mov dword_406008, eax

.h3mf85n:004034D0 ; ----------------------------------------------------

.h3mf85n:004034D5 db 68h ; CODE XREF: .h3mf85n:loc_40346B_j

.h3mf85n:004034D6 dd 4034E5h ; DATA XREF: .h3mf85n:004033F4_w

.h3mf85n:004034DA ; ----------------------------------------------------

.h3mf85n:004034DA pop ebx

.h3mf85n:004034DB jmp ebx

.h3mf85n:004034DB ; ----------------------------------------------------

.h3mf85n:004034DD dword_4034DD dd 0DDF8286Bh, 2A7B348Ch

.h3mf85n:004034E5 dword_4034E5 dd 88B9107Eh, 0E6F8C142h, 7D7F2B8Bh,

0DF8902F1h, 0B1C8CBC5h

.

.

.

.h3mf85n:00403CE5 dd 157CB335h

.h3mf85n:004041FD ; ----------------------------------------------------

.h3mf85n:004041FD

.h3mf85n:004041FD loc_4041FD: ; DATA XREF: .h3mf85n:004033E6_o

.h3mf85n:004041FD pop edi

.h3mf85n:004041FE pop esi.h3mf85n:004041FF pop ebx .h3mf85n:00404200 leave .h3mf85n:00404201 retn

This function starts out in what appears to be a familiar sequence, but at some point something very strange happens. Observe the code at address 004034DD, after the JMP EBX. It appears that IDA has determined that it is data, and not code. This data goes on and on until address 4041FD (I've eliminated most of the data from the listing just to preserve space). Why is there data in the middle of the function? This is a fairly common picture in copy protection code—routines are stored encrypted in the binaries and are decrypted in runtime. It is likely that this unrecognized data is just encrypted code that gets decrypted during runtime.

Let's perform a quick analysis of the initial, unencrypted code in the beginning of this function. One thing that's quickly evident is that the "readable" code area is roughly divided into two large sections, probably by an if statement. The conditional jump at 00403405 is where the program decides where to go, but notice that the CMP instruction at 00403401 is comparing [ebp-8] against 0 even though it is set to 1 one line before. You would usually see this kind of a sequence in a loop, where the variable is modified and then the code is executed again, in some kind of a loop. According to IDA, there are no such jumps in this function.

Since you have no reason to believe that the code at 40346D is ever executed (because the variable at [ebp-8] is hard-coded to 1), you can just focus on the first case for now. Briefly, you're looking at a loop that iterates through a chunk of data and XORs it with a constant (2BCA6179h). Going back to where the pointer is first initialized, you get to 004033E3, where [ebp-20h] is initialized to 4034DD through the stack. [ebp-20h] is later used as the initial address from where to start the XORing. If you look at the listing, you can see that 4034DD is an address in the middle of the function—right where the code stops and the data starts.

So, it appears that this code implements some kind of a decryption algorithm. The encrypted data is sitting right there in the middle of the function, at 4034DD. At this point, it is usually worthwhile to switch to a live view of the code in a debugger to see what comes out of that decryption process. For that you can run the program in OllyDbg and place a breakpoint right at the end of the decryption process, at 0040346B. When OllyDbg reaches this address, at first it looks as if the data at 4034DD is still unrecognized data, because Olly outputs something like this:

004034DD 12 DB 12 004034DE 49 DB 49 004034DF 32 DB 32 004034E0 F6 DB F6 004034E1 9E DB 9E 004034E2 7D DB 7D

However, you simply must tell Olly to reanalyze this memory to look for anything meaningful. You do this by pressing Ctrl+A. It is immediately obvious that something has changed. Instead of meaningless bytes you now have assembly language code. Scrolling down a few pages reveals that this is quite a bit of code—dozens of pages of code actually. This is really the body of the function you're investigating: 4033D1. The code in Listing 11.7 was just the decryption prologue. The full decrypted version of 4033D1 is quite long and would fill many pages, so instead I'll just go over the general structure of the function and what it does as a whole. I'll include key code sections that are worth investigating. It would be a good idea to have OllyDbg open and to let the function decrypt itself so that you can look at the code while reading this—there is quite a bit of interesting code in this function. One important thing to realize is that it wouldn't be practical or even useful to try to understand every line in this huge function. Instead, you must try to recognize key areas in the code and to understand their purpose.

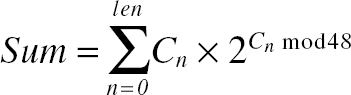

The function starts out with some pointer manipulation on the NTDLL base address you acquired earlier. The function digs through NTDLL's PE header until it gets to its export directory (OllyDbg tells you this because when the function has the pointer to the export directory Olly will comment it as ntdll.$$VProc_ImageExportDirectory). The function then goes through each export and performs an interesting (and highly unusual) bit of arithmetic on each function name string. Let's look at the code that does this.

004035A4 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-68] 004035A7 MOV ECX,DWORD PTR [EBP-68] 004035AA DEC ECX 004035AB MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-68],ECX 004035AE TEST EAX,EAX 004035B0 JE SHORT Defender.004035D 0004035B2 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-64] 004035B5 ADD EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-68] 004035B8 MOVSX ESI,BYTE PTR [EAX] 004035BB MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-68] 004035BE CDQ 004035BF PUSH 18 004035C1 POP ECX

004035C2 IDIV ECX 004035C4 MOV ECX,EDX 004035C6 SHL ESI,CL 004035C8 ADD ESI,DWORD PTR [EBP-6C] 004035CB MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-6C],ESI 004035CE JMP SHORT Defender.004035A4

It is easy to see in the debugger that [EBP-68] contains the current string's length (calculated earlier) and that [EBP-64] contains the address to the current string. It then enters a loop that takes each character in the string and shifts it left by the current index [EBP-68] modulo 24, and then adds the result into an accumulator at [EBP-6C]. This produces a 32-bit number that is like a checksum of the string. It is not clear at this point why this checksum is required. After all the characters are processed, the following code is executed:

004035D0 CMP DWORD PTR [EBP-6C],39DBA17A 004035D7 JNZ SHORT Defender.004035F1

If [EBP-6C] doesn't equal 39DBA17A the function proceeds to compute the same checksum on the next NTDLL export entry. If it is 39DBA17A the loop stops. This means that one of the entries is going to produce a checksum of 39DBA17A. You can put a breakpoint on the line that follows the JNZ in the code (at address 004035D9) and let the program run. This will show you which function the program is looking for. When you do that Olly breaks, and you can now go to [EBP-64] to see which name is currently loaded. It is NtAllocateVirtualMemory. So, it seems that the function is somehow interested in NtAllocateVirtualMemory, the Native API equivalent of VirtualAlloc, the documented Win32 API for allocating memory pages.

After computing the exact address of NtAllocateVirtualMemory (which is stored at [EBP-10]) the function proceeds to call the API. The following is the call sequence:

0040365F RDTSC 00403661 AND EAX,7FFF0000 00403666 MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-C],EAX 00403669 PUSH 4 0040366B PUSH 3000 00403670 LEA EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-4] 00403673 PUSH EAX 00403674 PUSH 0 00403676 LEA EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-C] 00403679 PUSH EAX 0040367A PUSH −1 0040367C CALL DWORD PTR [EBP-10]

Notice the RDTSC instruction at the beginning. This is an unusual instruction that you haven't encountered before. Referring to the Intel Instruction Set reference manuals [Intel2, Intel3] we learn that RDTSC performs a Read Time-Stamp Counter operation. The time-stamp counter is a very high-speed 64-bit counter, which is incremented by one on each clock cycle. This means that on a 3.4-GHz system this counter is incremented roughly 3.4 billion times per second. RDTSC loads the counter into EDX:EAX, where EDX receives the high-order 32 bits, and EAX receives the lower 32 bits. Defender takes the lower 32 bits from EAX and does a bitwise AND with 7FFF0000. It then takes the result and passes that (it actually passes a pointer to that value) as the second parameter in the NtAllocateVirtualMemory call.

Why would defender pass a part of the time-stamp counter as a parameter to NtAllocateVirtualMemory? Let's take a look at the prototype for NtAllocateVirtualMemory to determine what the system expects in the second parameter. This prototype was taken from http://undocumented.ntinternals.net, which is a good resource for undocumented Windows APIs. Of course, the authoritative source of information regarding the Native API is Gary Nebbett's book Windows NT/2000 Native API Reference [Nebbett].

NTSYSAPI

NTSTATUS

NTAPI

NtAllocateVirtualMemory(

IN HANDLE ProcessHandle,

IN OUT PVOID *BaseAddress,

IN ULONG ZeroBits,

IN OUT PULONG RegionSize,

IN ULONG AllocationType,

IN ULONG Protect );It looks like the second parameter is a pointer to the base address. IN OUT specifies that the function reads the value stored in BaseAddr and then writes to it. The way this works is that the function attempts to allocate memory at the specified address and writes the actual address of the allocated block back into BaseAddress. So, Defender is passing the time-stamp counter as the proposed allocation address... This may seem strange, but it really isn't—all the program is doing is trying to allocate memory at a random address in memory. The time-stamp counter is a good way to achieve a certain level of randomness.

Another interesting aspect of this call is the fourth parameter, which is the requested block size. Defender is taking a value from [EBP-4] and using that as the block size. Going back in the code, you can find the following sequence, which appears to take part in producing the block size:

004035FE MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP+8] 00403601 MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-70],EAX

00403604 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-70] 00403607 MOV ECX,DWORD PTR [EBP-70] 0040360A ADD ECX,DWORD PTR [EAX+3C] 0040360D MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-74],ECX 00403610 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-74] 00403613 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EAX+1C] 00403616 MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-78],EAX

This sequence starts out with the NTDLL base address from [EBP+8] and proceeds to access the PE part of the header. It then stores the pointer to the PE header in [EBP-74] and accesses offset +1C from the PE header. Because the PE header is made up of several structures, it is slightly more difficult to figure out an individual offset within it. The DT command in WinDbg is a good solution to this problem.

0:000> dt _IMAGE_NT_HEADERS -b

+0x000 Signature : Uint4B

+0x004 FileHeader :

+0x000 Machine : Uint2B

+0x002 NumberOfSections : Uint2B

+0x004 TimeDateStamp : Uint4B

+0x008 PointerToSymbolTable : Uint4B

+0x00c NumberOfSymbols : Uint4B

+0x010 SizeOfOptionalHeader : Uint2B

+0x012 Characteristics : Uint2B

+0x018 OptionalHeader :

+0x000 Magic : Uint2B

+0x002 MajorLinkerVersion : UChar

+0x003 MinorLinkerVersion : UChar

+0x004 SizeOfCode : Uint4B

+0x008 SizeOfInitializedData : Uint4B

+0x00c SizeOfUninitializedData : Uint4B

+0x010 AddressOfEntryPoint : Uint4B

+0x014 BaseOfCode : Uint4B

+0x018 BaseOfData : Uint4B

.

.Offset +1c is clearly a part of the OptionalHeader structure, and because OptionalHeader starts at offset +18 it is obvious that offset +1c is effectively offset +4 in OptionalHeader; Offset +4 is SizeOfCode. There is one other short sequence that appears to be related to the size calculations:

0040363D MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-7C] 00403640 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EAX+18] 00403643 MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-88],EAX

In this case, Defender is taking the pointer at [EBP-7C] and reading offset +18 from it. If you look at the value that is read into EAX in 0040363D, you'll see that it points somewhere into NTDLL's header (the specific value is likely to change with each new update of the operating system). Taking a quick look at the NTDLL headers using DUMPBIN shows you that the address in EAX is the beginning of NTDLL's export directory. Going to the structure definition for IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY, you will find that offset +18 is the NumberOfFunctions member. Here's the final preparation of the block size:

00403649 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-88] 0040364F MOV ECX,DWORD PTR [EBP-78] 00403652 LEA EAX,DWORD PTR [ECX+EAX*8+8]

The total block size is calculated according to the following formula: BlockSize = NTDLLCodeSize + (TotalExports + 1) * 8. You're still not sure what Defender is doing here, but you know that it has something to do with NTDLL's code section and with its export directory.

The function proceeds into another iteration of the NTDLL export list, again computing that strange checksum for each function name. In this loop there are two interesting lines that write into the newly allocated memory block:

0040380F MOV DWORD PTR DS:[ECX+EAX*8],EDX 00403840 MOV DWORD PTR DS:[EDX+ECX*8+4],EAX

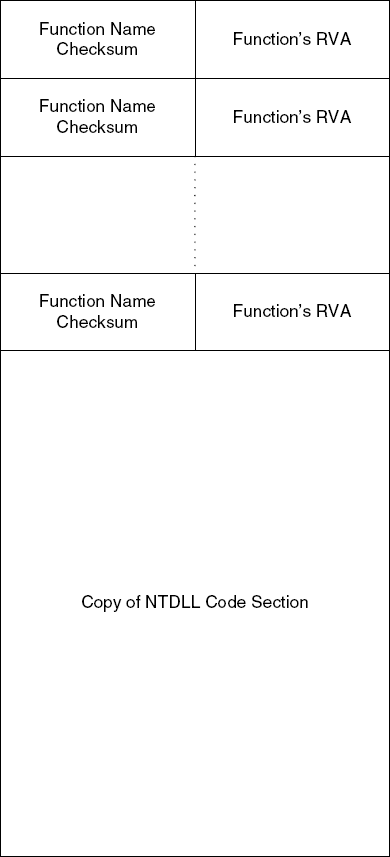

The preceding lines are executed for each exported function in NTDLL. They treat the allocated memory block as an array. The first writes the current function's checksum, and the second writes the exported function's RVA (Relative Virtual Address) into the same memory address plus 4. This indicates that the newly allocated memory block contains an array of data structures, each 8 bytes long. Offset +0 contains a function name's checksum, and offset +4 contains its RVA.

The following is the next code sequence that seems to be of interest:

004038FD MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-C8] 00403903 MOV ESI,DWORD PTR [EBP+8] 00403906 ADD ESI,DWORD PTR [EAX+2C] 00403909 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR [EBP-D8] 0040390F MOV EDX,DWORD PTR [EBP-C] 00403912 LEA EDI,DWORD PTR [EDX+EAX*8+8] 00403916 MOV EAX,ECX 00403918 SHR ECX,2 0040391B REP MOVS DWORD PTR ES:[EDI],DWORD PTR [ESI] 0040391D MOV ECX,EAX 0040391F AND ECX,3 00403922 REP MOVS BYTE PTR ES:[EDI],BYTE PTR [ESI]

This sequence performs a memory copy, and is a commonly seen "sentence" in assembly language. The REP MOVS instruction repeatedly copies DWORDs from the address at ESI to the address at EDI until ECX is zero. For each DWORD that is copied ECX is decremented once, and ESI and EDI are both incremented by four (the sequence is copying 32 bits at a time). The second REP MOVS performs a byte-by-byte copying of the last 3 bytes if needed. This is needed only for blocks whose size isn't 32-bit-aligned.

Let's see what is being copied in this sequence. ESI is loaded with [EBP+8] which is NTDLL's base address, and is incremented by the value at [EAX+2C]. Going back a bit you can see that EAX contains that same PE header address you were looking at earlier. If you go back to the PE headers you dumped earlier from WinDbg, you can see that Offset +2c is BaseOfCode. EDI is loaded with an address within your newly allocated memory block, at the point right after the table you've just filed. Essentially, this sequence is copying all the code in NTDLL into this memory buffer.

So here's what you have so far. You have a memory block that is allocated in runtime, with a specific effort being made to put it at a random address. This code contains a table of checksums of the names of all exported functions from NTDLL alongside their RVAs. Right after this table (in the same block) you have a copy of the entire NTDLL code section. Figure 11.15 provides a graphic visualization of this interesting and highly unusual data structure.

Now, if I saw this kind of code in an average application I would probably think that I was witnessing the work of a mad scientist. In a serious copy protection this makes a lot of sense. This is a mechanism that allocates a memory block at a random virtual address and creates what is essentially an obfuscated interface into the operating system module. You'll soon see just how effective this interface is at interfering with reversing efforts (which one can only assume is the only reason for its existence).

The huge function proceeds into calling another function, at 4030E5. This function starts out with two interesting loops, one of which is:

00403108 CMP ESI,190BC2 0040310E JE SHORT Defender.0040311E 00403110 ADD ECX,8 00403113 MOV ESI,DWORD PTR [ECX] 00403115 CMP ESI,EBX 00403117 JNZ SHORT Defender.00403108

This loop goes through the export table and compares each string checksum with 190BC2. It is fairly easy to see what is happening here. The code is looking for a specific API in NTDLL. Because it's not searching by strings but by this checksum you have no idea which API the code is looking for—the API's name is just not available. Here's what happens when the entry is found:

0040311E MOV ECX,DWORD PTR [ECX+4] 00403121 ADD ECX,EDI 00403123 MOV DWORD PTR [EBP-C],ECX

The function is taking the +4 offset of the found entry (remember that offset +4 contains the function's RVA) and adding to that the address where NTDLL's code section was copied. Later in the function a call is made into the function at that address. No doubt this is a call into a copied version of an NTDLL API. Here's what you see at that address:

7D03F0F2 MOV EAX,35 7D03F0F7 MOV EDX,7FFE0300 7D03F0FC CALL DWORD PTR [EDX] 7D03F0FE RET 20

The code at 7FFE0300 to which this function calls is essentially a call to the NTDLL API KiFastSystemCall, which is just a generic interface for calling into the kernel. Notice that you have this function's name because even though Defender copied the entire code section, the code explicitly referenced this function by address. Here is the code for KiFastSystemCall—it's just two lines.

7C90EB8B MOV EDX,ESP 7C90EB8D SYSENTER

Effectively, all KiFastSystemCall does is invoke the SYSENTER instruction. The SYSENTER instruction performs a kernel-mode switch, which means that the program executes a system call. It should be noted that this would all be slightly different under Windows 2000 or older systems, because Microsoft has changed its system calling mechanism after Windows 2000 (in Windows 2000 and older system calls using an INT 2E instruction). Windows XP, Windows Server 2003, and certainly newer operating systems such as the system currently code-named Longhorn all employ the new system call mechanism. If you're debugging under an older OS and you're seeing something slightly different at this point, that's to be expected.

You're now running into somewhat of a problem. You obviously can't step into SYSENTER because you're using a user-mode debugger. This means that it would be very difficult to determine which system call the program is trying to make! You have several options.

Switch to a kernel debugger, if one is available, and step into the system call to find out what Defender is doing.

Go back to the checksum/RVA table from before and pick up the RVA for the current system call—this would hopefully be the same RVA as in the

NTDLL.DLLexport directory. You can then do a DUMPBIN on NTDLL and determine which API it is you're looking at.Find which system call this is by its order in the exports list. The checksum/RVA table has apparently maintained the same order for the exports as in the original NTDLL export directory. Knowing the index of the call being made, you could look at the NTDLL export directory and try to determine which system call this is.

In this case, I think it would be best to go for the kernel debugger option, and I will be using NuMega SoftICE because it is the easiest to install and doesn't require two computers. If you don't have a copy of SoftICE and are unable to install WinDbg due to hardware constraints, I'd recommend that you go through one of the other options I've suggested. It would probably be easiest to use the function's RVA. In any case, I'd recommend that you get set up with a kernel debugger if you're serious about reversing—certain reversing scenarios are just undoable without a kernel debugger.

In this case, stepping into SYSENTER in SoftICE bring you into the KiFastCallEntry in NTOSKRNL. This flows right into KiSystemService, which is the generic system call dispatcher in Windows—all system calls go through it. Quickly tracing over most of the function, you get to the CALL EBX instruction near the end. This CALL EBX is where control is transferred to the specific system service that was called. Here, stepping into the function reveals that the program has called NtAllocateVirtualMemory again! You can hit F12 several times to jump back up to user mode and run into the next call from Defender. This is another API call that goes through the bizarre copied NTDLL interface. This time Defender is calling NtCreateThread. You can ignore this new thread for now and keep on stepping through the same function. It immediately returns after creating the new thread.

The sequence that comes right after the call to the thread-creating function again iterates through the checksum table, but this time it's looking for checksum 006DEF20. Immediately afterward another function is called from the copied NTDLL. You can step into this one as well and will find that it's a call to NtDelayExecution. In case you're not familiar with it, NtDelayExecution is the native API equivalent of the Win32 API SleepEx. SleepEx simply relinquishes the CPU for the time period requested. In this case, NtDelayExecution is being called immediately after a thread has been created. It would appear that Defender wants to let the newly created thread start running immediately.

Immediately after NtDelayExecution returns, Defender calls into another (internal) function at 403A41. This address is interesting because this function starts approximately 30 bytes after the place from which it's called. Also, SoftICE isn't recognizing any valid instructions after the CALL instruction until the beginning of the function itself. It almost looks like Defender is skipping a little chunk of data that's sitting right in the middle of the function! Indeed, dumping 4039FA, the address that immediately follows the CALL instruction reveals the following:

004039FA K.E.R.N.E.L.3.2...D.L.L.

So, it looks like the Unicode string KERNEL32.DLL is sitting right in the middle of this function. Apparently all the CALL instruction is doing is just skipping over this string to make sure the processor doesn't try to "execute" it. The code after the string again searches through our table, looking for two values: 6DEF20 and 1974C. You may recall that 6DEF20 is the name checksum for NtDelayExecution. We're not sure which API is represented by 1974C—we'll soon find out.

The first call being made in this sequence is again to NtDelayExecution, but here you run into a little problem. When we hit F10 to step over the call to NtDelayExecution SoftICE just disappears! When you look at the Command Prompt window, you see that Defender has just exited and that it hasn't printed any of its messages. It looks like SoftICE's presence has somehow altered Defender's behavior.

Seeing how the program was calling into NtDelayExecution when it unexpectedly disappeared, you can only make one assumption. The thread that was created earlier must be doing something, and by relinquishing the CPU Defender is probably trying to get the other thread to run. It looks like you must shift your reversing efforts to this thread to see what it's trying to do.

Let's go back to the thread creation code in the initialization routine to find out what code is being executed by this thread. Before attempting this, you must learn a bit on how NtCreateThread works. Unlike CreateThread, the equivalent Win32 API, NtCreateThread is a rather low-level function. Instead of just taking an lpStartAddress parameter as CreateThread does, NtCreateThread takes a CONTEXT data structure that accurately defines the thread's state when it first starts running.

A CONTEXT data structure contains full-blown thread state information. This includes the contents of all CPU registers, including the instruction pointer. To tell a newly created thread what to do, Defender will need to initialize the CONTEXT data structure and set the EIP member to the thread's entry point. Other than the instruction pointer, Defender must also manually allocate a stack space for the thread and set the ESP register in the CONTEXT structure to point to the beginning of the newly created thread's stack space (this explains the NtAllocateVirtualMemory call that immediately preceded the call to NtCreateThread). This long sequence just gives you an idea on how much effort is saved by calling the Win32 CreateThread API.

In the case of this thread creation, you need to find the place in the code where Defender is setting the Eip member in the CONTEXT data structure. Taking a look at the prototype definition for NtCreateThread, you can see that the CONTEXT data structure is passed as the sixth parameter. The function is passing the address [EBP-310] as the sixth parameter, so one can only assume that this is the address where CONTEXT starts. From looking at the definition of CONTEXT in WinDbg, you can see that the Eip member is at offset +b8. So, you know that the thread routine should be copied into [EBP-258] (310 – b8 = 258). The following line seems to be what you're looking for:

MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-258],Defender.00402EEF

Looking at the address 402EEF, you can see that it indeed contains code. This must be our thread routine. A quick glance shows that this function contains the exact same prologue as the previous function you studied in Listing 11.7, indicating that this function is also encrypted. Let's restart the program and place a breakpoint on this function (there is no need for a kernel-mode debugger for this part). The best position for your breakpoint is at 402FF4, right before the decrypter starts executing the decrypted code. Once you get there, you can take a look at the decrypted thread procedure code. It is quite interesting, so I've included it in its entirety (see Listing 11.8).

Example 11.8. Disassembly of the function at address 00402FFE in Defender.

00402FFE XOR EAX,EAX 00403000 INC EAX 00403001 JE Defender.004030C7 00403007 RDTSC 00403009 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-8],EAX 0040300C MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-4],EDX 0040300F MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[406000] 00403014 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-50],EAX 00403017 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-50] 0040301A CMP DWORD PTR DS:[EAX],0 0040301D JE SHORT Defender.00403046 0040301F MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-50] 00403022 CMP DWORD PTR DS:[EAX],6DEF20 00403028 JNZ SHORT Defender.0040303B 0040302A MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-50] 0040302D MOV ECX,DWORD PTR DS:[40601C] 00403033 ADD ECX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX+4] 00403036 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-44],ECX 00403039 JMP SHORT Defender.0040304A 0040303B MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-50] 0040303E ADD EAX,8 00403041 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-50],EAX 00403044 JMP SHORT Defender.00403017 00403046 AND DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-44],0 0040304A AND DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-4C],0 0040304E AND DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-48],0 00403052 LEA EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-4C] 00403055 PUSH EAX 00403056 PUSH 0 00403058 CALL DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-44] 0040305B RDTSC 0040305D MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-18],EAX 00403060 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-14],EDX 00403063 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-18] 00403066 SUB EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-8] 00403069 MOV ECX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-14] 0040306C SBB ECX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-4]