There are many cases where it is beneficial to create software that is immune to reversing. This chapter presents the most powerful and common reversing approaches from the perspectives of both a software developer interested in developing a software program and from the perspective of an attacker attempting to overcome the antireversing measures and reverse the program.

Before I begin an in-depth discussion on the various antireversing techniques and try to measure their performance, let's get one thing out of the way: It is never possible to entirely prevent reversing. What is possible is to hinder and obstruct reversers by wearing them out and making the process so slow and painful that they just give up. Whether some reversers will eventually succeed depends on several factors such as how capable they are and how motivated they are. Finally, the effectiveness of antireversing techniques will also depend on what price are you willing to pay for them. Every antireversing approach has some cost associated with it. Sometimes it's CPU usage, sometimes it's in code size, and sometimes it's reliability and robustness that's affected.

If you ignore the costs just described, antireversing almost always makes sense. Regardless of which application is being developed, as long as the end users are outside of the developing organization and the software is not open source, you should probably consider introducing some form of antireversing measures into the program. Granted, not every program is worth the effort of reversing it. Some programs contain relatively simple code that would be much easier to rewrite than to reverse from the program's binary.

Some applications have a special need for antireversing measures. An excellent example is copy protection technologies and digital rights management technologies. Preventing or obstructing reversers from looking inside copy protection technologies is often a crucial step of creating an effective means of protection.

Additionally, some software development platforms really necessitate some form of antireversing measures, because otherwise the program can be very easily converted back to a near-source-code representation. This is true for most bytecode-based platforms such as Java and .NET, and is the reason why so many code obfuscators have been created for such platforms (though it is also possible to obfuscate programs that were compiled to a native processor machine language). An obfuscator is an automated tool that reduces the readability of a program by modifying it or eliminating certain information from it. Code obfuscation is discussed in detail later in this chapter.

There are several antireversing approaches, each with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Applications that are intent on fighting off attackers will typically use a combination of more than one of the approaches discussed.

Eliminating Symbolic Information The first and most obvious step in hindering reversers is to eliminate any obvious textual information from the program. In a regular non-bytecode-based compiled program, this simply means to strip all symbolic information from the program executable. In bytecode-based programs, the executables often contain large amounts of internal symbolic information such as class names, class member names, and the names of instantiated global objects. This is true for languages such as Java and for platforms such as .NET. This information can be extremely helpful to reversers, which is why it absolutely must be eliminated from programs where reversing is a concern. The most fundamental feature of pretty much every bytecode obfuscator is to rename all symbols into meaningless sequences of characters.

Obfuscating the Program Obfuscation is a generic name for a number of techniques that are aimed at reducing the program's vulnerability to any kind of static analysis such as the manual reversing process described in this book. This is accomplished by modifying the program's layout, logic, data, and organization in a way that keeps it functionally identical yet far less readable. There are many different approaches to obfuscation, and this chapter discusses and demonstrates the most interesting and effective ones.

Embedding Antidebugger Code Another common antireversing approach is aimed specifically at hindering live analysis, in which a reverser steps through the program to determine details regarding how it's internally implemented. The idea is to have the program intentionally perform operations that would somehow damage or disable a debugger, if one is attached. Some of these approaches involve simply detecting that a debugger is present and terminating the program if it is, while others involve more sophisticated means of interfering with debuggers in case one is present. There are numerous antidebugger approaches, and many of them are platform-specific or even debugger-specific. In this chapter, I will be discussing the most interesting and effective ones, and will try to focus on the more generic techniques.

There's not really a whole lot to the process of information elimination. It is generally a nonissue in conventional compiler-based languages such as C and C++ because symbolic information is not usually included in release builds anyway—no special attention is required. If you're a developer and you're concerned about reversers, I'd recommend that you test your program for the presence of any useful symbolic information before it goes out the door.

One area where even compiler-based programs can contain a little bit of symbolic information is the import and export tables. If a program has numerous DLLs, and those DLLs export a large number of functions, the names of all of those exported functions could be somewhat helpful to reversers. Again, if you are a developer and are seriously concerned about people reversing your program, it might be worthwhile to export all functions by ordinals rather than by names. You'd be surprised how helpful these names can be in reversing a program, especially with C++ names that usually contain a full-blown class name and member name.

The issue of symbolic information is different with most bytecode-based languages. That's because these languages often use names for internal cross-referencing instead of addresses, so all internal names are preserved when a program is compiled. This creates a situation in which many bytecode programs can be decompiled back into an extremely readable source-code-like form. These strings cannot just be eliminated—they must be replaced with other strings, so that internal cross-references are not severed. The typical strategy is to have a program go over the executable after it is created and just rename all internal names to meaningless strings.

Encryption of program code is a common method for preventing static analysis. It is accomplished by encrypting the program at some point after it is compiled (before it is shipped to the customer) and embedding some sort of decryption code inside the executable. Unfortunately, this approach usually creates nothing but inconvenience for the skillful reverser because in most cases everything required for the decryption of the program must reside inside the executable. This includes the decryption logic, and, more importantly, the decryption key.

Additionally, the program must decrypt the code in runtime before it is executed, which means that a decrypted copy of the program or parts of it must reside in memory during runtime (otherwise the program just wouldn't be able to run).

Still, code encryption is a commonly used technique for hindering static analysis of programs because it significantly complicates the process of analyzing the program and can sometimes force reversers to perform a runtime analysis of the program. Unfortunately, in most cases, encrypted programs can be programmatically decrypted using special unpacker programs that are familiar with the specific encryption algorithm implemented in the program and can automatically find the key and decrypt the program. Unpackers typically create a new executable that contains the original program minus the encryption.

The only way to fight the automatic unpacking of executables (other than to use separate hardware that stores the decryption key or actually performs the decryption) is to try and hide the key within the program. One effective tactic is to use a key that is calculated in runtime, inside the program. Such a key-generation algorithm could easily be designed that would require a remarkably sophisticated unpacker. This could be accomplished by maintining multiple global variables that are continuously accessed and modified by various parts of the program. These variables can be used as a part of a complex mathematical formula at each point where a decryption key is required. Using live analysis, a reverser could very easily obtain each of those keys, but the idea is to use so many of them that it would take a while to obtain all of them and entirely decrypt the program. Because of the complex key generation algorithm, automatic decryption is (almost) out of the question. It would take a remarkable global data-flow analysis tool to actually determine what the keys are going to be.

Because a large part of the reversing process often takes place inside a debugger, it is sometimes beneficial to incorporate special code in the program that prevents or complicates the process of stepping through the program and placing breakpoints in it. Antidebugger techniques are particularly effective when combined with code encryption because encrypting the program forces reversers to run it inside a debugger in order to allow the program to decrypt itself. As discussed earlier, it is sometimes possible to unpack programs automatically using unpackers without running them, but it is possible to create a code encryption scheme that make it impossible to automatically unpack the encrypted executable.

Throughout the years there have been dozens of antidebugger tricks, but it's important to realize that they are almost always platform-specific and depend heavily on the specific operating system on which the software is running. Antidebugger tricks are also risky, because they can sometimes generate false positives and cause the program to malfunction even though no debugger is present. The same is not true for code obfuscation, in which the program typically grows in footprint or decreases in runtime performance, but the costs can be calculated in advance, and there are no unpredictable side effects.

The rest of this section explains some debugger basics which are necessary for understanding these antidebugger tricks, and proceeds to discuss specific antidebugging tricks that are reasonably effective and are compatible with NT-based operating systems.

To understand some of the antidebugger tricks that follow a basic understanding of how debuggers work is required. Without going into the details of how user-mode and kernel-mode debuggers attach into their targets, let's discuss how debuggers pause and control their debugees. When a user sets a breakpoint on an instruction, the debugger usually replaces that instruction with an int 3 instruction. The int 3 instruction is a special breakpoint interrupt that notifies the debugger that a breakpoint has been reached. Once the debugger is notified that the int 3 has been reached, it replaces the int 3 with the original instruction from the program and freezes the program so that the operator (typically a software developer) can inspect its state.

An alternative method of placing breakpoints in the program is to use hardware breakpoints. A hardware breakpoint is a breakpoint that the processor itself manages. Hardware breakpoints don't modify anything in the target program—the processor simply knows to break when a specific memory address is accessed. Such a memory address could either be a data address accessed by the program (such as the address of a certain variable) or it could simply be a code address within the executable (in which case the hardware breakpoint provides equivalent functionality to a software breakpoint).

Once a breakpoint is hit, users typically step through the code in order to analyze it. Stepping through code means that each instruction is executed individually and that control is returned to the debugger after each program instruction is executed. Single-stepping is implemented on IA-32 processors using the processor's trap flag (TF) in the EFLAGS register. When the trap flag is enabled, the processor generates an interrupt after every instruction that is executed. In this case the interrupt is interrupt number 1, which is the single-step interrupt.

IsDebuggerPresent is a Windows API that can be used as a trivial tool for detecting user-mode debuggers such as OllyDbg or WinDbg (when used as a user-mode debugger). The function accesses the current process's Process Environment Block (PEB) to determine whether a user-mode debugger is attached. A program can call this API and terminate if it returns TRUE, but such a method is not very effective against reversers because it is very easy to detect and bypass. The name of this API leaves very little room for doubt; when it is called, a reverser will undoubtedly find the call very quickly and eliminate or skip it.

One approach that makes this API somewhat more effective as an antidebugging measure is to implement it intrinsically, within the program code. This way the call will not stand out as being a part of antidebugger logic. Of course you can't just implement an API intrinsically—you must actually copy its code into your program. Luckily, in the case of IsDebuggerPresent this isn't really a problem, because the implementation is trivial; it consists of four lines of assembly code.

Instead of directly calling IsDebuggerPresent, a program could implement the following code.

mov eax,fs:[00000018] mov eax,[eax+0x30] cmp byte ptr [eax+0x2], 0 je RunProgram ; Inconspicuously terminate program here...

Assuming that the actual termination is done in a reasonably inconspicuous manner, this approach would be somewhat more effective in detecting user-mode debuggers, because it is more difficult to detect. One significant disadvantage of this approach is that it takes a specific implementation of the IsDebuggerPresent API and assumes that two internal offsets in NT data structure will not change in future releases of the operating system. First, the code retrieves offset +30 from the Thread Environment Block (TEB) data structure, which points to the current process's PEB. Then the sequence reads a byte at offset +2, which indicates whether a debugger is present or not. Embedding this sequence within a program is risky because it is difficult to predict what would happen if Microsoft changes one of these data structures in a future release of the operating system. Such a change could cause the program to crash or terminate even when no debugger is present.

The only tool you have for evaluating the likeliness of these two data structures to change is to look at past versions of the operating systems. The fact is that this particular API hasn't changed between Windows NT 4.0 (released in 1996) and Windows Server 2003. This is good because it means that this implementation would work on all relevant versions of the system. This is also a solid indicator that these are static data structures that are not likely to change. On the other hand, always remember what your investment banker keeps telling you: "past performance is not indicative of future results." Just because Microsoft hasn't changed these data structures in the past 7 years doesn't necessarily mean they won't change them in the next 7 years.

Finally, implementing this approach would require that you have the ability to somehow incorporate assembly language code into your program. This is not a problem with most C/C++ compilers (the Microsoft compiler supports the _asm keyword for adding inline assembly language code), but it might not be possible in every programming language or development platform.

The NtQuerySystemInformation native API can be used to determine if a kernel debugger is attached to the system. This function supports several different types of information requests. The SystemKernelDebuggerInformation request code can obtain information from the kernel on whether a kernel debugger is currently attached to the system.

ZwQuerySystemInformation(SystemKernelDebuggerInformation,

(PVOID) &DebuggerInfo, sizeof(DebuggerInfo), &ulReturnedLength);The following is a definition of the data structure returned by the SystemKernelDebuggerInformation request:

typedef struct _SYSTEM_KERNEL_DEBUGGER_INFORMATION {

BOOLEAN DebuggerEnabled;

BOOLEAN DebuggerNotPresent;

} SYSTEM_KERNEL_DEBUGGER_INFORMATION,

*PSYSTEM_KERNEL_DEBUGGER_INFORMATION;To determine whether a kernel debugger is attached to the system, the DebuggerEnabled should be checked. Note that SoftICE will not be detected using this scheme, only a serial-connection kernel debugger such as KD or WinDbg. For a straightforward detection of SoftICE, it is possible to simply check if the SoftICE kernel device is present. This can be done by opening a file called "\\.SIWVID" and assuming that SoftICE is installed on the machine if the file is opened successfully.

This approach of detecting the very presence of a kernel debugger is somewhat risky because legitimate users could have a kernel debugger installed, which would totally prevent them from using the program. I would generally avoid any debugger-specific approach because you usually need more than one of them (to cover the variety of debuggers that are available out there), and combining too many of these tricks reduces the quality of the protected software because it increases the risk of false positives.

This is another debugger-specific trick that I really wouldn't recommend unless you're specifically concerned about reversers that use NuMega SoftICE. While it's true that the majority of crackers use (illegal copies of) NuMega SoftICE, it is typically so easy for reversers to detect and work around this scheme that it's hardly worth the trouble. The one advantage this approach has is that it might baffle reversers that have never run into this trick before, and it might actually take such attackers several hours to figure out what's going on.

The idea is simple. Because SoftICE uses int 1 for single-stepping through a program, it must set its own handler for int 1 in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT). The program installs an exception handler and invokes int 1. If the exception code is anything but the conventional access violation exception (STATUS_ACCESS_VIOLATION), you can assume that SoftICE is running.

The following is an implementation of this approach for the Microsoft C compiler:

__try

{

_asm int 1;

}

__except(TestSingleStepException(GetExceptionInformation()))

{

}

int TestSingleStepException(LPEXCEPTION_POINTERS pExceptionInfo)

{

DWORD ExceptionCode = pExceptionInfo->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionCode;

if (ExceptionCode != STATUS_ACCESS_VIOLATION)

printf ("SoftICE is present!");

return EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER;

}This approach is similar to the previous one, except that here you enable the trap flag in the current process and check whether an exception is raised or not. If an exception is not raised, you can assume that a debugger has "swallowed" the exception for us, and that the program is being traced. The beauty of this approach is that it detects every debugger, user mode or kernel mode, because they all use the trap flag for tracing a program. The following is a sample implementation of this technique. Again, the code is written in C for the Microsoft C/C++ compiler.

BOOL bExceptionHit = FALSE;

__try

{

_asm

{

pushfd

or dword ptr [esp], 0x100 // Set the Trap Flag

popfd

// Load value into EFLAGS register

nop

}

}

__except(EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER)

{

bExceptionHit = TRUE; // An exception has been raised -

// there is no debugger.

}

if (bExceptionHit == FALSE)

printf ("A debugger is present!\n");Just as with the previous approach, this trick is somewhat limited because the PUSHFD and POPFD instructions really stand out. Additionally, some debuggers will only be detected if the detection code is being stepped through, in such cases the mere presence of the debugger won't be detected as long the code is not being traced.

Computing checksums on code fragments or on entire executables in runtime can make for a fairly powerful antidebugging technique, because debuggers must modify the code in order to install breakpoints. The general idea is to precalculate a checksum for functions within the program (this trick could be reserved for particularly sensitive functions), and have the function randomly check that the function has not been modified. This method is not only effective against debuggers, but also against code patching (see Chapter 11), but has the downside that constantly recalculating checksums is a relatively expensive operation.

There are several workarounds for this problem; it all boils down to employing a clever design. Consider, for example, a program that has 10 highly sensitive functions that are called while the program is loading (this is a common case with protected applications). In such a case, it might make sense to have each function verify its own checksum prior to returning to the caller. If the checksum doesn't match, the function could take an inconspicuous (so that reversers don't easily spot it) detour that would eventually lead to the termination of the program or to some kind of unusual program behavior that would be very difficult for the attacker to diagnose. The benefit of this approach is that it doesn't add much execution time to the program because only the specific functions that are considered to be sensitive are affected.

Note that this technique doesn't detect or prevent hardware breakpoints, because such breakpoints don't modify the program code in any way.

Fooling disassemblers as a means of preventing or inhibiting reversers is not a particularly robust approach to antireversing, but it is popular none the less. The strategy is quite simple. In processor architectures that use variable-length instructions, such as IA-32 processors, it is possible to trick disassemblers into incorrectly treating invalid data as the beginning of an instruction. This causes the disassembler to lose synchronization and disassemble the rest of the code incorrectly until it resynchronizes.

Before discussing specific techniques, I would like to briefly remind you of the two common approaches to disassembly (discussed in Chapter 4). A linear sweep is the trivial approach that simply disassembles instruction sequentially in the entire module. Recursive traversal is the more intelligent approach whereby instructions are analyzed by traversing instructions while following the control flow instructions in the program, so that when the program branches to a certain address, disassembly also proceeds at that address. Recursive traversal disassemblers are more reliable and are far more tolerant of various antidisassembly tricks.

Let's take a quick look at the reversing tools discussed in this book and see which ones actually use recursive traversal disassemblers. This will help you predict the effect each technique is going to have on the most common tools. Table 10.1 describes the disassembly technique employed in the most common reversing tools.

Let's start experimenting with some simple sequences that confuse disassemblers. We'll initially focus exclusively on linear sweep disassemblers, which are easier to trick, and later proceed to more involved sequences that attempt to confuse both types of disassemblers.

Consider for example the following inline assembler sequence:

_asm

{

Some code...

jmp After

_emit 0x0f

After:

mov eax, [SomeVariable]

push eax

call AFunction

}When loaded in OllyDbg, the preceding code sequence is perfectly readable, because OllyDbg performs a recursive traversal on it. The 0F byte is not disassembled, and the instructions that follow it are correctly disassembled. The following is OllyDbg's output for the previous code sequence.

0040101D EB 01 JMP SHORT disasmtest.00401020 0040101F 0F DB 0F 00401020 8B45 FC MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-4] 00401023 50 PUSH EAX 00401024 E8 D7FFFFFF CALL disasmtest.401000

In contrast, One can't say "on the other hand" without first saying "one on hand." when fed into NuMega SoftICE, the code sequence confuses its disassembler somewhat, and outputs the following:

001B:0040101D JMP 00401020 001B:0040101F JNP E8910C6A 001B:00401025 XLAT 001B:00401026 INVALID 001B:00401028 JMP FAR [EAX-24] 001B:0040102B PUSHAD 001B:0040102C INC EAX

As you can see, SoftICE's linear sweep disassembler is completely baffled by our junk byte, even though it is skipped over by the unconditional jump. Stepping over the unconditional JMP at 0040101D sets EIP to 401020, which SoftICE uses as a hint for where to begin disassembly. This produces the following listing, which is of course far better:

001B:0040101D JMP 00401020 001B:0040101F JNP E8910C6A 001B:00401020 MOV EAX,[EBP-04] 001B:00401023 PUSH EAX 001B:00401024 CALL 00401000

This listing is generally correct, but SoftICE is still confused by our 0F byte and is showing a JNP instruction in 40101F, which is where our 0F byte is at. This is inconsistent because JNP is a long instruction (it should be 6 bytes), and yet SoftICE is showing the correct MOV instruction right after it, at 401020, as though the JNP is 1 byte long! This almost looks like a disassembler bug, but it hardly matters considering that the real instructions starting at 401020 are all deciphered correctly.

The preceding technique can be somewhat effective in annoying and confusing reversers, but it is not entirely effective because it doesn't fool more clever disassemblers such as IDA pro or even smart debuggers such as OllyDbg.

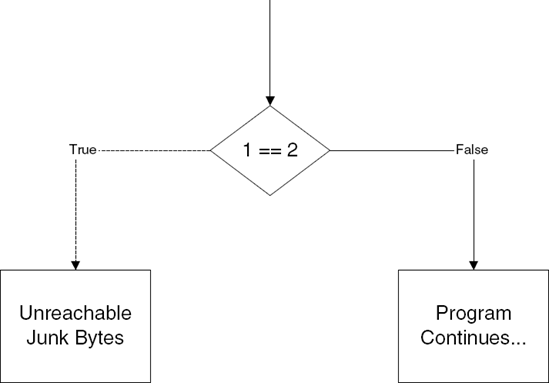

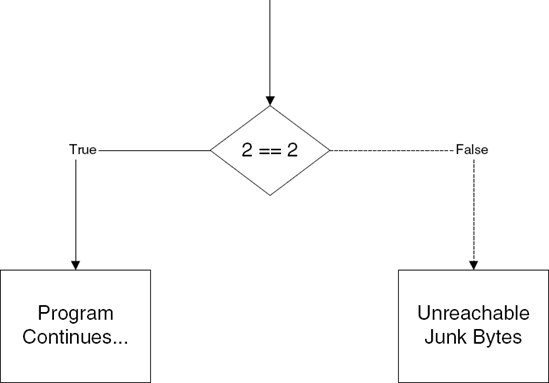

Let's proceed to examine techniques that would also fool recursive traversal disassemblers. When you consider a recursive traversal disassembler, you can see that in order to confuse it into incorrectly disassembling data you'll need to feed it an opaque predicate. Opaque predicates are essentially false branches, where the branch appears to be conditional, but is essentially unconditional. As with any branch, the code is split into two paths. One code path leads to real code, and the other to junk. Figure 10.1 illustrates this concept where the condition is never true. Figure 10.1 illustrates this concept where the condition is never true. Figure 10.2 illustrates the reverse condition, in which the condition is always true.

Unfortunately, different disassemblers produce different output for these sequences. Consider the following sequence for example:

_asm

{

mov eax, 2

cmp eax, 2

je After

_emit 0xf

After:

mov eax, [SomeVariable]

push eax

call AFunction

}This is similar to the method used earlier for linear sweep disassemblers, except that you're now using a simple opaque predicate instead of an unconditional jump. The opaque predicate simply compares 2 with 2 and performs a jump if they're equal. The following listing was produced by IDA Pro:

.text:00401031 mov eax, 2 .text:00401036 cmp eax, 2 .text:00401039 jz short near ptr loc_40103B+1 .text:0040103B .text:0040103B loc_40103B: ; CODE XREF: .text:00401039 _j .text:0040103B jnp near ptr 0E8910886h .text:00401041 mov ebx, 68FFFFFFh .text:00401046 fsub qword ptr [eax+40h] .text:00401049 add al, ch .text:0040104B add eax, [eax]

As you can see, IDA bought into it and produced incorrect code. Does this mean that IDA Pro, which has a reputation for being one of the most powerful disassemblers around, is flawed in some way? Absolutely not. When you think about it, properly disassembling these kinds of code sequences is not a problem that can be solved in a generic method—the disassembler must contain specific heuristics that deal with these kinds of situations. Instead disassemblers such as IDA (and also OllyDbg) contain specific commands that inform the disassembler whether a certain byte is code or data. To properly disassemble such code in these products, one would have to inform the disassembler that our junk byte is really data and not code. This would solve the problem and the disassembler would produce a correct disassembly.

Let's go back to our sample from earlier and see how OllyDbg reacts to it.

00401031 . B8 02000000 MOV EAX,2 00401036 . 83F8 02 CMP EAX,2 00401039 . 74 01 JE SHORT compiler.0040103C 0040103B 0F DB 0F 0040103C > 8B45 F8 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-8]

0040103F . 50 PUSH EAX 00401040 E8 BBFFFFFF CALL compiler.main

Olly is clearly ignoring the junk byte and using the conditional jump as a marker to the real code starting position, which is why it is providing an accurate listing. It is possible that Olly contains specific code for dealing with these kinds of tricks. Regardless, at this point it becomes clear that you can take advantage of Olly's use of the jump's target address to confuse it; if OllyDbg uses conditional jumps to mark the beginning of valid code sequences, you can just create a conditional jump that points to the beginning of the invalid sequence. The following code snippet demonstrates this idea:

_asm

{

mov eax, 2

cmp eax, 3

je Junk

jne After

Junk:

_emit 0xf

After:

mov eax, [SomeVariable]

push eax

call AFunction

}This sequence is an improved implementation of the same approach. It is more likely to confuse recursive traversal disassemblers because they will have to randomly choose which of the two jumps to use as indicators of valid code. The reason why this is not trivial is that both codes are "valid" from the disassembler's perspective. This is a theoretical problem: the disassembler has no idea what constitutes valid code. The only measurement it has is whether it finds invalid opcodes, in which case a clever disassembler should probably consider the current starting address as invalid and look for an alternative one.

Let's look at the listing Olly produces from the above code.

00401031 . B8 02000000 MOV EAX,2 00401036 . 83F8 03 CMP EAX,3 00401039 . 74 02 JE SHORT compiler.0040103D 0040103B . 75 01 JNZ SHORT compiler.0040103E 0040103D > 0F8B 45F850E8 JPO E8910888 00401043 ? B9 FFFFFF68 MOV ECX,68FFFFFF 00401048 ? DC60 40 FSUB QWORD PTR DS:[EAX+40] 0040104B ? 00E8 ADD AL,CH 0040104D ? 0300 ADD EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX] 0040104F ? 0000 ADD BYTE PTR DS:[EAX],AL

This time OllyDbg swallows the bait and uses the invalid 0040103D as the starting address from which to disassemble, which produces a meaningless assembly language listing. What's more, IDA Pro produces an equally unreadable output—both major recursive traversers fall for this trick. Needless to say, linear sweepers such as SoftICE react in the exact same manner.

One recursive traversal disassembler that is not falling for this trick is PEBrowse Professional. Here is the listing produced by PEBrowse:

0x401031: B802000000 mov eax,0x2 0x401036: 83F803 cmp eax,0x3 0x401039: 7402 jz 0x40103d ; (*+0x4) 0x40103B: 7501 jnz 0x40103e ; (*+0x3) 0x40103D: 0F8B45F850E8 jpo 0xe8910888 ; <==0x00401039(*-0x4) ;*********************************************************************** 0x40103E: 8B45F8 mov eax,dword ptr [ebp-0x8] ; VAR:0x8 0x401041: 50 push eax 0x401042: E8B9FFFFFF call 0x401000 ;***********************************************************************

Apparently (and it's difficult to tell whether this is caused by the presence of special heuristics designed to withstand such code sequences or just by a fluke) PEBrowse Professional is trying to disassemble the code from both 40103D and from 40103E, and is showing both options. It looks like you'll need to improve on your technique a little bit—there must not be a direct jump to the valid code address if you're to fool every disassembler. The solution is to simply perform an indirect jump using a value loaded in a register. The following code confuses every disassembler I've tested, including both linear-sweep-based tools and recursive-traversal-based tools.

_asm

{

mov eax, 2

cmp eax, 3

je Junk

mov eax, After

jmp eax

Junk:

_emit 0xf

After:

mov eax, [SomeVariable]

push eax

call AFunction

}The reason this trick works is quite trivial—because the disassembler has no idea that the sequence mov eax, After, jmp eax is equivalent to jmp After, the disassembler is not even trying to begin disassembling from the After address.

The disadvantage of all of these tricks is that they count on the disassembler being relatively dumb. Luckily, most Windows disassemblers are dumb enough that you can fool them. What would happen if you ran into a clever disassembler that actually analyzes each line of code and traces the flow of data? Such a disassembler would not fall for any of these tricks, because it would detect your opaque predicate; how difficult is it to figure out that a conditional jump that is taken when 2 equals 3 is never actually going to be taken? Moreover, a simple data-flow analysis would expose the fact that the final JMP sequence is essentially equivalent to a JMP After, which would probably be enough to correct the disassembly anyhow.

Still even a cleverer disassembler could be easily fooled by exporting the real jump addresses into a central, runtime generated data structure. It would be borderline impossible to perform a global data-flow analysis so comprehensive that it would be able to find the real addresses without actually running the program.

Let's see how one would use the previous techniques in a real program. I've created a simple macro called OBFUSCATE, which adds a little assembly language sequence to a C program. This sequence would temporarily confuse most disassemblers until they resynchronized. The number of instructions it will take to resynchronize depends not only on the specific disassembler used, but also on the specific code that comes after the macro.

Example 10.1. A simple code obfuscation macro that aims at confusing disassemblers.

#define paste(a, b) a##b

#define pastesymbols(a, b) paste(a, b)

#define OBFUSCATE() \

_asm { mov eax, __LINE__ * 0x635186f1 };\

_asm { cmp eax, __LINE__ * 0x9cb16d48 };\

_asm { je pastesymbols(Junk,__LINE__) };\

_asm { mov eax, pastesymbols(After, __LINE__) };\

_asm { jmp eax };\

_asm { pastesymbols(Junk, __LINE__): };\

_asm { _emit (0xd8 + __LINE__ % 8) };\

_asm { pastesymbols(After, __LINE__): };This macro was tested on the Microsoft C/C++ compiler (version 13), and contains pseudorandom values to make it slightly more difficult to search and replace (the MOV and CMP instructions and the junk byte itself are all random, calculated using the current code line number). Notice that the junk byte ranges from D8 to DF—these are good opcodes to use because they are all multibyte opcodes. I'm using the __LINE__ macro in order to create unique symbol names in case the macro is used repeatedly in the same function. Each occurrence of the macro will define symbols with different names. The paste and pastesymbols macros are required because otherwise the compiler just won't properly resolve the __LINE__ constant and will use the string __LINE__ instead.

If distributed throughout the code, this macro (and you could very easily create dozens of similar variations) would make the reversing process slightly more tedious. The problem is that too many copies of this code would make the program run significantly slower (especially if the macro is placed inside key loops in the program that run many times). Overusing this technique would also make the program significantly larger in terms of both memory consumption and disk space usage.

It's important to realize that all of these techniques are limited in their effectiveness. They most certainly won't deter an experienced and determined reverser from reversing or cracking your application, but they might complicate the process somewhat. The manual approach for dealing with this kind of obfuscated code is to tell the disassembler where the code really starts. Advanced disassemblers such as IDA Pro or even OllyDbg's built-in disassembler allow users to add disassembly hints, which enable the program to properly interpret the code.

The biggest problem with these macros is that they are repetitive, which makes them exceedingly vulnerable to automated tools that just search and destroy them. A dedicated attacker can usually write a program or script that would eliminate them in 20 minutes. Additionally, specific disassemblers have been created that overcome most of these obfuscation techniques (see "Static Disassembly of Obfuscated Binaries" by Christopher Kruegel, et al. [Kruegel]). Is it worth it? In some cases it might be, but if you are looking for powerful antireversing techniques, you should probably stick to the control flow and data-flow obfuscating transformations discussed next.

You probably noticed that the antireversing techniques described so far are all platform-specific "tricks" that in my opinion do nothing more than increase the attacker's "annoyance factor". Real code obfuscation involves transforming the code in such a way that makes it significantly less human-readable, while still retaining its functionality. These are typically non-platform-specific transformations that modify the code to hide its original purpose and drown the reverser in a sea of irrelevant information. The level of complexity added by an obfuscating transformation is typically called potency, and can be measured using conventional software complexity metrics such as how many predicates the program contains and the depth of nesting in a particular code sequence.

Beyond the mere additional complexity introduced by adding additional logic and arithmetic to a program, an obfuscating transformation must be resilient (meaning that it cannot be easily undone). Because many of these transformations add irrelevant instructions that don't really produce valuable data, it is possible to create deobfuscators. A deobfuscator is a program that implements various data-flow analysis algorithms on an obfuscated program which sometimes enable it to separate the wheat from the chaff and automatically remove all irrelevant instructions and restore the code's original structure. Creating resilient obfuscation transformations that are resistant to deobfuscation is a major challenge and is the primary goal of many obfuscators.

Finally, an obfuscating transformation will typically have an associated cost. This can be in the form of larger code, slower execution times, or increased memory runtime consumption. It is important to realize that some transformations do not incur any kind of runtime costs, because they involve a simple reorganization of the program that is transparent to the machine, but makes the program less human-readable.

In the following sections, I will be going over the common obfuscating transformations. Most of these transformations were meant to be applied programmatically by running an obfuscator on an existing program, either at the source code or the binary level. Still, many of these transformations can be applied manually, while the program is being written or afterward, before it is shipped to end users. Automatic obfuscation is obviously far more effective because it can obfuscate the entire program and not just small parts of it. Additionally, automatic obfuscation is typically performed after the program is compiled, which means that the original source code is not made any less readable (as is the case when obfuscation is performed manually).

Control flow transformations are transformations that alter the order and flow of a program in a way that reduces its human readability. In "Manufacturing Cheap, Resilient, and Stealthy Opaque Constructs" by Christian Collberg, Clark Thomborson, and Douglas Low [Collberg1], control flow transformations are categorized as computation transformations, aggregation transformations, and ordering transformations.

Computation transformations are aimed at reducing the readability of the code by modifying the program's original control flow structure in ways that make for a functionally equivalent program that is far more difficult to translate back into a high-level language. This is can be done either by removing control flow information from the program or by adding new control flow statements that complicate the program and cannot be easily translated into a high-level language.

Aggregation transformations destroy the high-level structure of the program by breaking the high-level abstractions created by the programmer while the program was being written. The basic idea is to break such abstractions so that the high-level organization of the code becomes senseless.

Ordering transformations are somewhat less powerful transformations that randomize (as much as possible) the order of operations in a program so that its readability is reduced.

Opaque predicates are a fundamental building block for control flow transformations. I've already introduced some trivial opaque predicates in the previous section on antidisassembling techniques. The idea is to create a logical statement whose outcome is constant and is known in advance. Consider, for example the statement if (x + 1 == x). This statement will obviously never be satisfied and can be used to confuse reversers and automated decompilation tools into thinking that the statement is actually a valid part of the program.

With such a simple statement, it is going to be quite easy for both humans and machines to figure out that this is a false statement. The objective is to create opaque predicates that would be difficult to distinguish from the actual program code and whose behavior would be difficult to predict without actually stepping into the code. The interesting thing about opaque predicates (and about several other aspects of code obfuscation as well) is that confusing an automated deobfuscator is often an entirely different problem from confusing a human reverser.

Consider for example the concurrency-based opaque predicates suggested in [Collberg1]. The idea is to create one or more threads that are responsible for constantly generating new random values and storing them in a globally accessible data structure. The values stored in those data structures consistently adhere to simple rules (such as being lower or higher than a certain constant). The threads that contain the actual program code can access this global data structure and check that those values are within the expected range. It would make quite a challenge for an automated deobfuscator to figure this structure out and pinpoint such fake control flow statements. The concurrent access to the data would hugely complicate the matter for an automated deobfuscator (though an obfuscator would probably only be aware of such concurrency in a bytecode language such as Java). In contrast, a person would probably immediately suspect a thread that constantly generates random numbers and stores them in a global data structure. It would probably seem very fishy to a human reverser.

Now consider a far simple arrangement where several bogus data members are added into an existing program data structure. These members are constantly accessed and modified by code that's embedded right into the program. Those members adhere to some simple numeric rules, and the opaque predicates in the program rely on these rules. Such implementation might be relatively easy to detect for a powerful deobfuscator (depending on the specific platform), but could be quite a challenge for a human reverser.

Generally speaking, opaque predicates are more effective when implemented in lower-level machine-code programs than in higher-level bytecode program, because they are far more difficult to detect in low-level machine code. The process of automatically identifying individual data structures in a native machine-code program is quite difficult, which means that in most cases opaque predicates cannot be automatically detected or removed. That's because performing global data-flow analysis on low-level machine code is not always simple or even possible. For reversers, the only way to deal with opaque predicates implemented on low-level native machine-code programs is to try and manually locate them by looking at the code. This is possible, but not very easy.

In contrast, higher-level bytecode executables typically contain far more details regarding the specific data structures used in the program. That makes it much easier to implement data-flow analysis and write automated code that detects opaque predicates.

The bottom line is that you should probably focus most of your antireversing efforts on confusing the human reversers when developing in lower-level languages and on automated decompilers/deobfuscators when working with bytecode languages such as Java.

For a detailed study of opaque constructs and various implementation ideas see [Collberg1] and General Method of Program Code Obfuscation by Gregory Wroblewski [Wroblewski].

Because bytecode-based languages are highly detailed, there are numerous decompilers that are highly effective for decompiling bytecode executables. One of the primary design goals of most bytecode obfuscators is to confuse decompilers, so that the code cannot be easily restored to a highly detailed source code. One trick that does wonders is to modify the program binary so that the bytecode contains statements that cannot be translated back into the original high-level language. The example given in A Taxonomy of Obfuscating Transformations by Christian Collberg, Clark Thomborson, and Douglas Low [Collberg2] is the Java programming language, where the high-level language does not have the goto statement, but the Java bytecode does. This means that its possible to add goto statements into the bytecode in order to completely break the program's flow graph, so that a decompiler cannot later reconstruct it (because it contains instructions that cannot be translated back to Java).

In native processor languages such as IA-32 machine code, decompilation is such a complex and fragile process that any kind of obfuscation transformation could easily get them to fail or produce meaningless code. Consider, for example, what would happen if a decompiler ran into the OBFUSCATE macro from the previous section.

Converting a program or a function into a table interpretation layout is a highly powerful obfuscation approach, that if done right can repel both deobfuscators and human reversers. The idea is to break a code sequence into multiple short chunks and have the code loop through a conditional code sequence that decides to which of the code sequences to jump at any given moment. This dramatically reduces the readability of the code because it completely hides any kind of structure within it. Any code structures, such as logical statements or loops, are buried inside this unintuitive structure.

As an example, consider the simple data processing function in Listing 10.2.

Example 10.2. A simple data processing function that XORs a data block with a parameter passed to it and writes the result back into the data block.

00401000 push esi 00401001 push edi 00401002 mov edi,dword ptr [esp+10h] 00401006 xor eax,eax 00401008 xor esi,esi 0040100A cmp edi,3 0040100D jbe 0040103A 0040100F mov edx,dword ptr [esp+0Ch] 00401013 add edi,0FFFFFFFCh 00401016 push ebx

00401017 mov ebx,dword ptr [esp+18h] 0040101B shr edi,2 0040101E push ebp 0040101F add edi,1 00401022 mov ecx,dword ptr [edx] 00401024 mov ebp,ecx 00401026 xor ebp,esi 00401028 xor ebp,ebx 0040102A mov dword ptr [edx],ebp 0040102C xor eax,ecx 0040102E add edx,4 00401031 sub edi,1 00401034 mov esi,ecx 00401036 jne 00401022 00401038 pop ebp 00401039 pop ebx 0040103A pop edi 0040103B pop esi 0040103C ret

Let us now take this function and transform it using a table interpretation transformation.

Example 10.3. The data-processing function from Listing 10.2 transformed using a table interpretation transformation.

00401040 push ecx 00401041 mov edx,dword ptr [esp+8] 00401045 push ebx 00401046 push ebp 00401047 mov ebp,dword ptr [esp+14h] 0040104B push esi 0040104C push edi 0040104D mov edi,dword ptr [esp+10h] 00401051 xor eax,eax 00401053 xor ebx,ebx 00401055 mov ecx,1 0040105A lea ebx,[ebx] 00401060 lea esi,[ecx-1] 00401063 cmp esi,8 00401066 ja 00401060 00401068 jmp dword ptr [esi*4+4010B8h] 0040106F xor dword ptr [edx],ebx 00401071 add ecx,1 00401074 jmp 00401060 00401076 mov edi,dword ptr [edx]

00401078 add ecx,1 0040107B jmp 00401060 0040107D cmp ebp,3 00401080 ja 00401071 00401082 mov ecx,9 00401087 jmp 00401060 00401089 mov ebx,edi 0040108B add ecx,1 0040108E jmp 00401060 00401090 sub ebp,4 00401093 jmp 00401055 00401095 mov esi,dword ptr [esp+20h] 00401099 xor dword ptr [edx],esi 0040109B add ecx,1 0040109E jmp 00401060 004010A0 xor eax,edi 004010A2 add ecx,1 004010A5 jmp 00401060 004010A7 add edx,4 004010AA add ecx,1 004010AD jmp 00401060 004010AF pop edi 004010B0 pop esi 004010B1 pop ebp 004010B2 pop ebx 004010B3 pop ecx 004010B4 ret The function's jump table: 0x004010B8 0040107d 00401076 00401095 0040106f 0x004010C8 00401089 004010a0 004010a7 00401090 0x004010D8 004010af

The function is Listing 10.3 is functionally equivalent to the one in 10.2, but it was obfuscated using a table interpretation transformation. The function was broken down into nine segments that represent the different stages in the original function. The implementation constantly loops through a junction that decides where to go next, depending on the value of ECX. Each code segment sets the value of ECX so that the correct code segment follows. The specific code address that is executed is determined using the jump table, which is included at the end of the listing. Internally, this is implemented using a simple switch statement, but when you think of it logically, this is similar to a little virtual machine that was built just for this particular function. Each "instruction" advances the "instruction pointer", which is stored in ECX. The actual "code" is the jump table, because that's where the sequence of operations is stored.

This transformation can be improved upon in several different ways, depending on how much performance and code size you're willing to give up. In a native code environment such as IA-32 assembly language, it might be beneficial to add some kind of disassembler-confusion macros such as the ones described earlier in this chapter. If made reasonably polymorphic, such macros would not be trivial to remove, and would really complicate the reversing process for this kind of a function. That's because these macros would prevent reversers from being able to generate a full listing of the obfuscated at any given moment. Reversing a table interpretation function such as the one in Listing 10.3 without having a full view of the entire function is undoubtedly an unpleasant reversing task.

Other than the confusion macros, another powerful enhancement for the obfuscation of the preceding function would be to add an additional lookup table, as is demonstrated in Listing 10.4.

Example 10.4. The data-processing function from Listing 10.2 transformed using an array-based version of the table interpretation obfuscation method.

00401040 sub esp,28h 00401043 mov edx,dword ptr [esp+2Ch] 00401047 push ebx 00401048 push ebp 00401049 mov ebp,dword ptr [esp+38h] 0040104D push esi 0040104E push edi 0040104F mov edi,dword ptr [esp+10h] 00401053 xor eax,eax 00401055 xor ebx,ebx 00401057 mov dword ptr [esp+14h],1 0040105F mov dword ptr [esp+18h],8 00401067 mov dword ptr [esp+1Ch],4 0040106F mov dword ptr [esp+20h],6 00401077 mov dword ptr [esp+24h],2 0040107F mov dword ptr [esp+28h],9 00401087 mov dword ptr [esp+2Ch],3 0040108F mov dword ptr [esp+30h],7 00401097 mov dword ptr [esp+34h],5 0040109F lea ecx,[esp+14h] 004010A3 mov esi,dword ptr [ecx] 004010A5 add esi,0FFFFFFFFh 004010A8 cmp esi,8 004010AB ja 004010A3 004010AD jmp dword ptr [esi*4+401100h] 004010B4 xor dword ptr [edx],ebx 004010B6 add ecx,18h 004010B9 jmp 004010A3 004010BB mov edi,dword ptr [edx] 004010BD add ecx,8 004010C0 jmp 004010A3

004010C2 cmp ebp,3 004010C5 ja 004010E8 004010C7 add ecx,14h 004010CA jmp 004010A3 004010CC mov ebx,edi 004010CE sub ecx,14h 004010D1 jmp 004010A3 004010D3 sub ebp,4 004010D6 sub ecx,4 004010D9 jmp 004010A3 004010DB mov esi,dword ptr [esp+44h] 004010DF xor dword ptr [edx],esi 004010E1 sub ecx,10h 004010E4 jmp 004010A3 004010E6 xor eax,edi 004010E8 add ecx,10h 004010EB jmp 004010A3 004010ED add edx,4 004010F0 sub ecx,18h 004010F3 jmp 004010A3 004010F5 pop edi 004010F6 pop esi 004010F7 pop ebp 004010F8 pop ebx 004010F9 add esp,28h 004010FC ret The function's jump table: 0x00401100 004010c2 004010bb 004010db 004010b4 0x00401110 004010cc 004010e6 004010ed 004010d3 0x00401120 004010f5

The function in Listing 10.4 is an enhanced version of the function from Listing 10.3. Instead of using direct indexes into the jump table, this implementation uses an additional table that is filled in runtime. This table contains the actual jump table indexes, and the index into that table is handled by the program in order to obtain the correct flow of the code. This enhancement makes this function significantly more unreadable to human reversers, and would also seriously complicate matters for a deobfuscator because it would require some serious data-flow analysis to determine the current value of the index to the array.

The original implementation in [Wang] is more focused on preventing static analysis of the code by deobfuscators. The approach chosen in that study is to use pointer aliases as a means of confusing automated deobfuscators. Pointer aliases are simply multiple pointers that point to the same memory location. Aliases significantly complicate any kind of data-flow analysis process because the analyzer must determine how memory modifications performed through one pointer would affect the data accessed using other pointers that point to the same memory location. In this case, the idea is to create several pointers that point to the array of indexes and have to write to several locations within at several stages. It would be borderline impossible for an automated deobfuscator to predict in advance the state of the array, and without knowing the exact contents of the array it would not be possible to properly analyze the code.

In a brief performance comparison I conducted, I measured a huge runtime difference between the original function and the function from Listing 10.4: The obfuscated function from Listing 10.4 was about 3.8 times slower than the original unobfuscated function in Listing 10.4 was about 3.8 times slower than the original unobfuscated function in Listing 10.2. Scattering 11 copies of the OBFUSCATE macro increased this number to about 12, which means that the heavily obfuscated version runs about 12 times slower than its unobfuscated counterpart! Whether this kind of extreme obfuscation is worth it depends on how concerned you are about your program being reversed, and how concerned you are with the runtime performance of the particular function being obfuscated. Remember that there's usually no reason to obfuscate the entire program, only the parts that are particularly sensitive or important. In this particular situation, I think I would stick to the array-based approach from Listing 10.4—the OBFUSCATE macros wouldn't be worth the huge performance penalty they incur.

Inlining is a well-known compiler optimization technique where functions are duplicated to any place in the program that calls them. Instead of having all callers call into a single copy of the function, the compiler replaces every call into the function with an actual in-place copy of it. This improves runtime performance because the overhead of calling a function is completely eliminated, at the cost of significantly bloating the size of the program (because functions are duplicated). In the context of obfuscating transformations, inlining is a powerful tool because it eliminates the internal abstractions created by the software developer. Reversers have no information on which parts of a certain function are actually just inlined functions that might be called from numerous places throughout the program.

One interesting enhancement suggested in [Collberg3] is to combine inlining with outlining in order to create a highly potent transformation. Outlining means that you take a certain code sequence that belongs in one function and create a new function that contains just that sequence. In other words it is the exact opposite of inlining. As an obfuscation tool, outlining becomes effective when you take a random piece of code and create a dedicated function for it. When done repetitively, such a process can really add to the confusion factor experienced by a human reverser.

Code interleaving is a reasonably effective obfuscation technique that is highly potent, yet can be quite costly in terms of execution speed and code size. The basic concept is quite simple: You take two or more functions and interleave their implementations so that they become exceedingly difficult to read.

Function1()

{

Function1_Segment1;

Function1_Segment2;

Function1_Segment3;

}

Function2()

{

Function2_Segment1;

Function2_Segment2;

Function2_Segment3;

}

Function3()

{

Function3_Segment1;

Function3_Segment2;

Function3_Segment3;

}Here is what these three functions would look like in memory after they are interleaved.

Function1_Segment3;End of Function1Function1_Segment1; (This is the Function1 entry-point)Opaque Predicate -> Always jumps to Function1_Segment2Function3_Segment2;Opaque Predicate -> Always jumps to Segment3Function3_Segment1; (This is the Function3 entry-point)Opaque Predicate -> Always jumps to Function3_Segment2Function2_Segment2;Opaque Predicate -> Always jumps to Function2_Segment3Function1_Segment2;Opaque Predicate -> Always jumps to Function1_Segment3Function2_Segment3;End of Function2Function3_Segment3;End of Function3Function2_Segment1; (This is the Function2 entry-point)Opaque Predicate -> Always jumps to Function2_Segment2

Notice how each function segment is followed by an opaque predicate that jumps to the next segment. You could theoretically use an unconditional jump in that position, but that would make automated deobfuscation quite trivial. As for fooling a human reverser, it all depends on how convincing your opaque predicates are. If a human reverser can quickly identify the opaque predicates from the real program logic, it won't take long before these functions are reversed. On the other hand, if the opaque predicates are very confusing and look as if they are an actual part of the program's logic, the preceding example might be quite difficult to reverse. Additional obfuscation can be achieved by having all three functions share the same entry point and adding a parameter that tells the new function which of the three code paths should be taken. The beauty of this is that it can be highly confusing if the three functions are functionally irrelevant.

Shuffling the order of operations in a program is a free yet decently effective method for confusing reversers. The idea is to simply randomize the order of operations in a function as much as possible. This is beneficial because as reversers we count on the locality of the code we're reversing—we assume that there's a logical order to the operations performed by the program.

It is obviously not always possible to change the order of operations performed in a program; many program operations are codependent. The idea is to find operations that are not codependent and completely randomize their order. Ordering transformations are more relevant for automated obfuscation tools, because it wouldn't be advisable to change the order of operations in the program source code. The confusion caused by the software developers would probably outweigh the minor influence this transformation has on reversers.

Data transformation are obfuscation transformations that focus on obfuscating the program's data rather than the program's structure. This makes sense because as you already know figuring out the layout of important data structures in a program is a key step in gaining an understanding of the program and how it works. Of course, data transformations also boil down to code modifications, but the focus is to make the program's data as difficult to understand as possible.

One interesting data-obfuscation idea is to modify the encoding of some or all program variables. This can greatly confuse reversers because the intuitive meaninings of variable values will not be immediately clear. Changing the encoding of a variable can mean all kinds of different things, but a good example would be to simply shift it by one bit to the left. In a counter, this would mean that on each iteration the counter would be incremented by 2 instead of 1, and the limiting value would have to be doubled, so that instead of:

for (int i=1; i < 100; i++)

you would have:

for (int i=2; i < 200; i += 2)

which is of course functionally equivalent. This example is trivial and would do very little to deter reversers, but you could create far more complex encodings that would cause significant confusion with regards to the variable's meaning and purpose. It should be noted that this type of transformation is better applied at the binary level, because it might actually be eliminated (or somewhat modified) by a compiler during the optimization process.

Restructuring arrays means that you modify the layout of some arrays in a way that preserves their original functionality but confuses reversers with regard to their purpose. There are many different forms to this transformation, such as merging more than one array into one large array (by either interleaving the elements from the arrays into one long array or by sequentially connecting the two arrays). It is also possible to break one array down into several smaller arrays or to change the number of dimensions in an array. These transformations are not incredibly potent, but could somewhat increase the confusion factor experienced by reversers. Keep in mind that it would usually be possible for an automated deobfuscator to reconstruct the original layout of the array.

There are quite a few options available to software developers interested in blocking (or rather slowing down) reversers from digging into their programs. In this chapter, I've demonstrated the two most commonly used approaches for dealing with this problem: antidebugger tricks and code obfuscation. The bottom line is that it is certainly possible to create code that is extremely difficult to reverse, but there is always a cost. The most significant penalty incurred by most antireversing techniques is in runtime performance; They just slow the program down. The magnitude of investment in antireversing measures will eventually boil down to simple economics: How performance-sensitive is the program versus how concerned are you about piracy and reverse engineering?