This chapter provides an introduction to low-level software, which is a critical aspect of the field of reverse engineering. Low-level software is a general name for the infrastructural aspects of the software world. Because the low-level aspects of software are often the only ones visible to us as reverse engineers, we must develop a firm understanding of these layers that together make up the realm of low-level software.

This chapter opens with a very brief overview of the conventional, high-level perspective of software that every software developer has been exposed to. We then proceed to an introduction of low-level software and demonstrate how fundamental high-level software concepts map onto the low-level realm. This is followed by an introduction to assembly language, which is a key element in the reversing process and an important part of this book. Finally, we introduce several auxiliary low-level software topics that can assist in low-level software comprehension: compilers and software execution environments.

If you are an experienced software developer, parts of this chapter might seem trivial, particularly the high-level perspectives in the first part of this chapter. If that is the case, it is recommended that you start reading from the section titled "Low-Level Perspectives" later in this chapter, which provides a low-level perspective on familiar software development concepts.

Let's review some basic software development concepts as they are viewed from the perspective of conventional software engineers. Even though this view is quite different from the one we get while reversing, it still makes sense to revisit these topics just to make sure they are fresh in your mind before entering into the discussion of low-level software.

The following sections provide a quick overview of fundamental software engineering concepts such as program structure (procedures, objects, and the like), data management concepts (such as typical data structures, the role of variables, and so on), and basic control flow constructs. Finally, we briefly compare the most popular high-level programming languages and evaluate their "reversibility." If you are a professional software developer and feel that these topics are perfectly clear to you, feel free to skip ahead to the section titled "Low-Level Perspectives" later in this chapter. In any case, please note that this is an ultra-condensed overview of material that could fill quite a few books. This section was not written as an introduction to software development—such an introduction is beyond the scope of this book.

When I was a kid, my first programming attempts were usually long chunks of BASIC code that just ran sequentially and contained the occasional goto commands that would go back and forth between different sections of the program. That was before I had discovered the miracle of program structure. Program structure is the thing that makes software, an inherently large and complex thing, manageable by humans. We break the monster into small chunks where each chunk represents a "unit" in the program in order to conveniently create a mental image of the program in our minds. The same process takes place during reverse engineering. Reversers must try and reconstruct this map of the various components that together make up a program. Unfortunately, that is not always easy.

The problem is that machines don't really need program structure as much as we do. We humans can't deal with the concept of working on and understanding one big complicated thing—objects or concepts need to be broken up into manageable chunks. These chunks are good for dividing the work among various people and also for creating a mental division of the work within one's mind. This is really a generic concept about human thinking—when faced with large tasks we're naturally inclined to try to break them down into a bunch of smaller tasks that together make up the whole.

Machines on the other hand often have a conflicting need for eliminating some of these structural elements. For example, think of how the process of compiling and linking a program eliminates program structure: individual source files and libraries are all linked into a single executable, many function boundaries are eliminated through inlining and are simply pasted into the code that calls them. The machine is eliminating redundant structural details that are not needed for efficiently running the code. All of these transformations affect the reversing process and make it somewhat more challenging. I will be dealing with the process of reconstructing the structure of a program in the reversing projects throughout this book.

How do software developers break down software into manageable chunks? The general idea is to view the program as a set of separate black boxes that are responsible for very specific and (hopefully) accurately defined tasks. The idea is that someone designs and implements a black box, tests it and confirms that it works, and then integrates it with other components in the system. A program can therefore be seen as a large collection of black boxes that interact with one another. Different programming languages and development platforms approach these concepts differently, but the general idea is almost always the same.

Likewise, when an application is being designed it is usually broken down into mental black boxes that are each responsible for a chunk of the application. For instance, in a word processor you could view the text-editing component as one box and the spell checker component as another box. This process is called encapsulation because each component box encapsulates certain functionality and simply makes it available to whoever needs it, without exposing unnecessary details about the internal implementation of the component.

Component boxes are frequently developed by different people or even by different groups, but they still must be able to interact. Boxes vary in size: Some boxes implement entire application features (like the earlier spell checker example), while others represent far smaller and more primitive functionality such as sorting functions and other low-level data management functions. These smaller boxes are usually made to be generic, meaning that they can be used anywhere in the program where the specific functionality they provide is required.

Developing a robust and reliable product rests primarily on two factors: that each component box is well implemented and reliably performs its duties, and that each box has a well defined interface for communicating with the outside world.

In most reversing scenarios, the first step is to determine the component structure of the application and the exact responsibilities of each component. From there, one usually picks a component of interest and delves into the details of its implementation.

The following sections describe the various technical tools available to software developers for implementing this type of component-level encapsulation in the code. We start with large components, such as static and dynamic modules, and proceed to smaller units such as procedures and objects.

The largest building block for a program is the module. Modules are simply binary files that contain isolated areas of a program's executable (essentially the component boxes from our previous discussion). There are two basic types of modules that can be combined together to make a program: static libraries and dynamic libraries.

Static libraries: Static libraries make up a group of source-code files that are built together and represent a certain component of a program. Logically, static libraries usually represent a feature or an area of functionality in the program. Frequently, a static library is not an integral part of the product that's being developed but rather an external, third-party library that adds certain functionality to it. Static libraries are added to a program while it is being built, and they become an integral part of the program's binaries. They are difficult to make out and isolate when we look at the program from a low-level perspective while reversing.

Dynamic libraries: Dynamic libraries (called Dynamic Link Libraries, or DLLs in Windows) are similar to static libraries, except that they are not embedded into the program, and they remain in a separate file, even when the program is shipped to the end user. A dynamic library allows for upgrading individual components in a program without updating the entire program. As long as the interface it exports remains constant, a library can (at least in theory) be replaced seamlessly—without upgrading any other components in the program. An upgraded library would usually contain improved code, or even entirely different functionality through the same interface. Dynamic libraries are very easy to detect while reversing, and the interfaces between them often simplify the reversing process because they provide helpful hints regarding the program's architecture.

There are two basic code-level constructs that are considered the most fundamental building blocks for a program. These are procedures and objects.

In terms of code structure, the procedure is the most fundamental unit in software. A procedure is a piece of code, usually with a well-defined purpose, that can be invoked by other areas in the program. Procedures can optionally receive input data from the caller and return data to the caller. Procedures are the most commonly used form of encapsulation in any programming language.

The next logical leap that supersedes procedures is to divide a program into objects. Designing a program using objects is an entirely different process than the process of designing a regular procedure-based program. This process is called object-oriented design (OOD), and is considered by many to be the most popular and effective approach to software design currently available.

OOD methodology defines an object as a program component that has both data and code associated with it. The code can be a set of procedures that is related to the object and can manipulate its data. The data is part of the object and is usually private, meaning that it can only be accessed by object code, but not from the outside world. This simplifies the design processes, because developers are forced to treat objects as completely isolated entities that can only be accessed through their well-defined interfaces. Those interfaces usually consist of a set of procedures that are associated with the object. Those procedures can be defined as publicly accessible procedures, and are invoked primarily by clients of the object. Clients are other components in the program that require the services of the object but are not interested in any of its implementation details. In most programs, clients are themselves objects that simply require the other objects' services.

Beyond the mere division of a program into objects, most object-oriented programming languages provide an additional feature called inheritance. Inheritance allows designers to establish a generic object type and implement many specific implementations of that type that offer somewhat different functionality. The idea is that the interface stays the same, so the client using the object doesn't have to know anything about the specific object type it is dealing with—it only has to know the base type from which that object is derived.

This concept is implemented by declaring a base object, which includes a declaration of a generic interface to be used by every object that inherits from that base object. Base objects are usually empty declarations that offer little or no actual functionality. In order to add an actual implementation of the object type, another object is declared, which inherits from the base object and contains the actual implementations of the interface procedures, along with any support code or data structures. The beauty of this system is that for a single base object there can be multiple descendant objects that can implement entirely different functionalities, but export the same interface. Clients can use these objects without knowing the specific object type they are dealing with—they are only aware of the base object's type. This concept is called polymorphism.

A program deals with data. Any operation always requires input data, room for intermediate data, and a way to send back results. To view a program from below and understand what is happening, you must understand how data is managed in the program. This requires two perspectives: the high-level perspective as viewed by software developers and the low-level perspective that is viewed by reversers.

High-level languages tend to isolate software developers from the details surrounding data management at the system level. Developers are usually only made aware of the simplified data flow described by the high-level language.

Naturally, most reversers are interested in obtaining a view of the program that matches that simplified high-level view as closely as possible. That's because the high-level perspective is usually far more human-friendly than the machine's perspective. Unfortunately, most programming languages and software development platforms strip (or mangle) much of that human-readable information from binaries shipped to end users.

In order to be able to recover some or all of that high-level data flow information from a program binary, you must understand how programs view and treat data from both the programmer's high-level perspective and the low-level machine-generated code. The following sections take us through a brief overview of high-level data constructs such as variables and the most common types of data structures.

For a software developer, the key to managing and storing data is usually named variables. All high-level languages provide developers with the means to declare variables at various scopes and use them to store information.

Programming languages provide several abstractions for these variables. The level at which variables are defined determines which parts of the program will be able to access it, and also where it will be physically stored. The names of named variables are usually relevant only during compilation. Many compilers completely strip the names of variables from a program's binaries and identify them using their address in memory. Whether or not this is done depends on the target platform for which the program is being built.

User-defined data structures are simple constructs that represent a group of data fields, each with its own type. The idea is that these fields are all somehow related, which is why the program stores and handles them as a single unit. The data types of the specific fields inside a data structure can either be simple data types such as integers or pointers or they can be other data structures.

While reversing, you'll be encountering a variety of user-defined data structures. Properly identifying such data structures and deciphering their contents is critical for achieving program comprehension. The key to doing this successfully is to gradually record every tiny detail discovered about them until you have a sufficient understanding of the individual fields. This process will be demonstrated in the reversing chapters in the second part of this book.

Other than user-defined data structures, programs routinely use a variety of generic data structures for organizing their data. Most of these generic data structures represent lists of items (where each item can be of any type, from a simple integer to a complex user-defined data structure). A list is simply a group of data items that share the same data type and that the program views as belonging to the same group. In most cases, individual list entries contain unique information while sharing a common data layout. Examples include lists such as a list of contacts in an organizer program or list of e-mail messages in an e-mail program. Those are the user-visible lists, but most programs will also maintain a variety of user-invisible lists that manage such things as areas in memory currently active, files currently open for access, and the like.

The way in which lists are laid out in memory is a significant design decision for software engineers and usually depends on the contents of the items and what kinds of operations are performed on the list. The expected number of items is also a deciding factor in choosing the list's format. For example, lists that are expected to have thousands or millions of items might be laid out differently than lists that can only grow to a couple of dozens of items. Also, in some lists the order of the items is critical, and new items are constantly added and removed from specific locations in the middle of the list. Other lists aren't sensitive to the specific position of each item. Another criterion is the ability to efficiently search for items and quickly access them. The following is a brief discussion of the common lists found in the average program:

Arrays: Arrays are the most basic and intuitive list layout—items are placed sequentially in memory one after the other. Items are referenced by the code using their index number, which is just the number of items from the beginning of the list to the item in question. There are also multidimensional arrays, which can be visualized as multilevel arrays. For example, a two-dimensional array can be visualized as a simple table with rows and columns, where each reference to the table requires the use of two position indicators: row and column. The most significant downside of arrays is the difficulty of adding and removing items in the middle of the list. Doing that requires that the second half of the array (any items that come after the item we're adding or removing) be copied to make room for the new item or eliminate the empty slot previously occupied by an item. With very large lists, this can be an extremely inefficient operation.

Linked lists: In a linked list, each item is given its own memory space and can be placed anywhere in memory. Each item stores the memory address of the next item (a link), and sometimes also a link to the previous item. This arrangement has the added flexibility of supporting the quick addition or removal of an item because no memory needs to be copied. To add or remove items in a linked list, the links in the items that surround the item being added or removed must be changed to reflect the new order of items. Linked lists address the weakness of arrays with regard to inefficiencies when adding and removing items by not placing items sequentially in memory. Of course, linked lists also have their weaknesses. Because items are randomly scattered throughout memory, there can be no quick access to individual items based on their index. Also, linked lists are less efficient than arrays with regard to memory utilization, because each list item must have one or two link pointers, which use up precious memory.

Trees: A tree is similar to a linked list in that memory is allocated separately for each item in the list. The difference is in the logical arrangement of the items: In a tree structure, items are arranged hierarchically, which greatly simplifies the process of searching for an item. The root item represents a median point in the list, and contains links to the two halves of the tree (these are essentially branches): one branch links to lower-valued items, while the other branch links to higher-valued items. Like the root item, each item in the lower levels of the hierarchy also has two links to lower nodes (unless it is the lowest item in the hierarchy). This layout greatly simplifies the process of binary searching, where with each iteration one eliminates one-half of the list in which it is known that the item is not present. With a binary search, the number of iterations required is very low because with each iteration the list becomes about 50 percent shorter.

In order to truly understand a program while reversing, you'll almost always have to decipher control flow statements and try to reconstruct the logic behind those statements. Control flow statements are statements that affect the flow of the program based on certain values and conditions. In high-level languages, control flow statements come in the form of basic conditional blocks and loops, which are translated into low-level control flow statements by the compiler. Here is a brief overview of the basic high-level control flow constructs:

Conditional blocks: Conditional code blocks are implemented in most programming languages using the

ifstatement. They allow for specifying one or more condition that controls whether a block of code is executed or not.Switch blocks: Switch blocks (also known as n-way conditionals) usually take an input value and define multiple code blocks that can get executed for different input values. One or more values are assigned to each code block, and the program jumps to the correct code block in runtime based on the incoming input value. The compiler implements this feature by generating code that takes the input value and searches for the correct code block to execute, usually by consulting a lookup table that has pointers to all the different code blocks.

Loops: Loops allow programs to repeatedly execute the same code block any number of times. A loop typically manages a counter that determines the number of iterations already performed or the number of iterations that remain. All loops include some kind of conditional statement that determines when the loop is interrupted. Another way to look at a loop is as a conditional statement that is identical to a conditional block, with the difference that the conditional block is executed repeatedly. The process is interrupted when the condition is no longer satisfied.

High-level languages were made to allow programmers to create software without having to worry about the specific hardware platform on which their program would run and without having to worry about all kinds of annoying low-level details that just aren't relevant for most programmers. Assembly language has its advantages, but it is virtually impossible to create large and complex software on assembly language alone. High-level languages were made to isolate programmers from the machine and its tiny details as much as possible.

The problem with high-level languages is that there are different demands from different people and different fields in the industry. The primary tradeoff is between simplicity and flexibility. Simplicity means that you can write a relatively short program that does exactly what you need it to, without having to deal with a variety of unrelated machine-level details. Flexibility means that there isn't anything that you can't do with the language. High-level languages are usually aimed at finding the right balance that suits most of their users. On one hand, there are certain things that happen at the machine-level that programmers just don't need to know about. On the other, hiding certain aspects of the system means that you lose the ability to do certain things.

When you reverse a program, you usually have no choice but to get your hands dirty and become aware of many details that happen at the machine level. In most cases, you will be exposed to such obscure aspects of the inner workings of a program that even the programmers that wrote them were unaware of. The challenge is to sift through this information with enough understanding of the high-level language used and to try to reach a close approximation of what was in the original source code. How this is done depends heavily on the specific programming language used for developing the program.

From a reversing standpoint, the most important thing about a high-level programming language is how strongly it hides or abstracts the underlying machine. Some languages such as C provide a fairly low-level perspective on the machine and produce code that directly runs on the target processor. Other languages such as Java provide a substantial level of separation between the programmer and the underlying processor.

The following sections briefly discuss today's most popular programming languages:

The C programming language is a relatively low-level language as high-level languages go. C provides direct support for memory pointers and lets you manipulate them as you please. Arrays can be defined in C, but there is no bounds checking whatsoever, so you can access any address in memory that you please. On the other hand, C provides support for the common high-level features found in other, higher-level languages. This includes support for arrays and data structures, the ability to easily implement control flow code such as conditional code and loops, and others.

C is a compiled language, meaning that to run the program you must run the source code through a compiler that generates platform-specific program binaries. These binaries contain machine code in the target processor's own native language. C also provides limited cross-platform support. To run a program on more than one platform you must recompile it with a compiler that supports the specific target platform.

Many factors have contributed to C's success, but perhaps most important is the fact that the language was specifically developed for the purpose of writing the Unix operating system. Modern versions of Unix such as the Linux operating system are still written in C. Also, significant portions of the Microsoft Windows operating system were also written in C (with the rest of the components written in C++).

Another feature of C that greatly affected its commercial success has been its high performance. Because C brings you so close to the machine, the code written by programmers is almost directly translated into machine code by compilers, with very little added overhead. This means that programs written in C tend to have very high runtime performance.

C code is relatively easy to reverse because it is fairly similar to the machine code. When reversing one tries to read the machine code and reconstruct the original source code as closely as possible (though sometimes simply understanding the machine code might be enough). Because the C compiler alters so little about the program, relatively speaking, it is fairly easy to reconstruct a good approximation of the C source code from a program's binaries. Except where noted, the high-level language code samples in this book were all written in C.

The C++ programming language is an extension of C, and shares C's basic syntax. C++ takes C to the next level in terms of flexibility and sophistication by introducing support for object-oriented programming. The important thing is that C++ doesn't impose any new limits on programmers. With a few minor exceptions, any program that can be compiled under a C compiler will compile under a C++ compiler.

The core feature introduced in C++ is the class. A class is essentially a data structure that can have code members, just like the object constructs described earlier in the section on code constructs. These code members usually manage the data stored within the class. This allows for a greater degree of encapsulation, whereby data structures are unified with the code that manages them. C++ also supports inheritance, which is the ability to define a hierarchy of classes that enhance each other's functionality. Inheritance allows for the creation of base classes that unify a group of functionally related classes. It is then possible to define multiple derived classes that extend the base class's functionality.

The real beauty of C++ (and other object-oriented languages) is polymorphism (briefly discussed earlier, in the "Common Code Constructs" section). Polymorphism allows for derived classes to override members declared in the base class. This means that the program can use an object without knowing its exact data type—it must only be familiar with the base class. This way, when a member function is invoked, the specific derived object's implementation is called, even though the caller is only aware of the base class.

Reversing code written in C++ is very similar to working with C code, except that emphasis must be placed on deciphering the program's class hierarchy and on properly identifying class method calls, constructor calls, etc. Specific techniques for identifying C++ constructs in assembly language code are presented in Appendix C.

Note

In case you're not familiar with the syntax of C, C++ draws its name from the C syntax, where specifying a variable name followed by ++ incdicates that the variable is to be incremented by 1. C++ is the equivalent of C = C + 1.

Java is an object-oriented, high-level language that is different from other languages such as C and C++ because it is not compiled into any native processor's assembly language, but into the Java bytecode. Briefly, the Java instruction set and bytecode are like a Java assembly language of sorts, with the difference that this language is not usually interpreted directly by the hardware, but is instead interpreted by software (the Java Virtual Machine).

Java's primary strength is the ability to allow a program's binary to run on any platform for which the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is available.

Because Java programs run on a virtual machine (VM), the process of reversing a Java program is completely different from reversing programs written in compiler-based languages such as C and C++. Java executables don't use the operating system's standard executable format (because they are not executed directly on the system's CPU). Instead they use .class files, which are loaded directly by the virtual machine.

The Java bytecode is far more detailed compared to a native processor machine code such as IA-32, which makes decompilation a far more viable option. Java classes can often be decompiled with a very high level of accuracy, so that the process of reversing Java classes is usually much simpler than with native code because it boils down to reading a source-code-level representation of the program. Sure, it is still challenging to comprehend a program's undocumented source code, but it is far easier compared to starting with a low-level assembly language representation.

C# was developed by Microsoft as a Java-like object-oriented language that aims to overcome many of the problems inherent in C++. C# was introduced as part of Microsoft's .NET development platform, and (like Java and quite a few other languages) is based on the concept of using a virtual machine for executing programs.

C# programs are compiled into an intermediate bytecode format (similar to the Java bytecode) called the Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL). MSIL programs run on top of the common language runtime (CLR), which is essentially the .NET virtual machine. The CLR can be ported into any platform, which means that .NET programs are not bound to Windows—they could be executed on other platforms.

C# has quite a few advanced features such as garbage collection and type safety that are implemented by the CLR. C# also has a special unmanaged mode that enables direct pointer manipulation.

As with Java, reversing C# programs sometimes requires that you learn the native language of the CLR—MSIL. On the other hand, in many cases manually reading MSIL code will be unnecessary because MSIL code contains highly detailed information regarding the program and the data types it deals with, which makes it possible to produce a reasonably accurate high-level language representation of the program through decompilation. Because of this level of transparency, developers often obfuscate their code to make it more difficult to comprehend. The process of reversing .NET programs and the effects of the various obfuscation tools are discussed in Chapter 12.

The complexity in reversing arises when we try to create an intuitive link between the high-level concepts described earlier and the low-level perspective we get when we look at a program's binary. It is critical that you develop a sort of "mental image" of how high-level constructs such as procedures, modules, and variables are implemented behind the curtains. The following sections describe how basic program constructs such as data structures and control flow constructs are represented in the lower-levels.

One of the most important differences between high-level programming languages and any kind of low-level representation of a program is in data management. The fact is that high-level programming languages hide quite a few details regarding data management. Different languages hide different levels of details, but even plain ANSI C (which is considered to be a relatively low-level language among the high-level language crowd) hides significant data management details from developers.

For instance, consider the following simple C language code snippet.

int Multiply(int x, int y)

{

int z;z = x * y;

return z;

}This function, as simple as it may seem, could never be directly translated into a low-level representation. Regardless of the platform, CPUs rarely have instructions for declaring a variable or for multiplying two variables to yield a third. Hardware limitations and performance considerations dictate and limit the level of complexity that a single instruction can deal with. Even though Intel IA-32 CPUs support a very wide range of instructions, some of which remarkably powerful, most of these instructions are still very primitive compared to high-level language statements.

So, a low-level representation of our little Multiply function would usually have to take care of the following tasks:

Store machine state prior to executing function code

Allocate memory for

zLoad parameters

xandyfrom memory into internal processor memory (registers)Multiply

xbyyand store the result in a registerpreviously allocated for

zRestore machine state stored earlier

Return to caller and send back

zas the return value

You can easily see that much of the added complexity is the result of low-level data management considerations. The following sections introduce the most common low-level data management constructs such as registers, stacks, and heaps, and how they relate to higher-level concepts such as variables and parameters.

In order to avoid having to access the RAM for every single instruction, microprocessors use internal memory that can be accessed with little or no performance penalty. There are several different elements of internal memory inside the average microprocessor, but the one of interest at the moment is the register. Registers are small chunks of internal memory that reside within the processor and can be accessed very easily, typically with no performance penalty whatsoever.

The downside with registers is that there are usually very few of them. For instance, current implementations of IA-32 processors only have eight 32-bit registers that are truly generic. There are quite a few others, but they're mostly there for specific purposes and can't always be used. Assembly language code revolves around registers because they are the easiest way for the processor to manage and access immediate data. Of course, registers are rarely used for long-term storage, which is where external RAM enters into the picture. The bottom line of all of this is that CPUs don't manage these issues automatically—they are taken care of in assembly language code. Unfortunately, managing registers and loading and storing data from RAM to registers and back certainly adds a bit of complexity to assembly language code.

So, if we go back to our little code sample, most of the complexities revolve around data management. x and y can't be directly multiplied from memory, the code must first read one of them into a register, and then multiply that register by the other value that's still in RAM. Another approach would be to copy both values into registers and then multiply them from registers, but that might be unnecessary.

These are the types of complexities added by the use of registers, but registers are also used for more long-term storage of values. Because registers are so easily accessible, compilers use registers for caching frequently used values inside the scope of a function, and for storing local variables defined in the program's source code.

While reversing, it is important to try and detect the nature of the values loaded into each register. Detecting the case where a register is used simply to allow instructions access to specific values is very easy because the register is used only for transferring a value from memory to the instruction or the other way around. In other cases, you will see the same register being repeatedly used and updated throughout a single function. This is often a strong indication that the register is being used for storing a local variable that was defined in the source code. I will get back to the process of identifying the nature of values stored inside registers in Part II, where I will be demonstrating several real-world reversing sessions.

Let's go back to our earlier Multiply example and examine what happens in Step 2 when the program allocates storage space for variable "z". The specific actions taken at this stage will depend on some seriously complex logic that takes place inside the compiler. The general idea is that the value is placed either in a register or on the stack. Placing the value in a register simply means that in Step 4 the CPU would be instructed to place the result in the allocated register. Register usage is not managed by the processor, and in order to start using one you simply load a value into it. In many cases, there are no available registers or there is a specific reason why a variable must reside in RAM and not in a register. In such cases, the variable is placed on the stack.

A stack is an area in program memory that is used for short-term storage of information by the CPU and the program. It can be thought of as a secondary storage area for short-term information. Registers are used for storing the most immediate data, and the stack is used for storing slightly longer-term data. Physically, the stack is just an area in RAM that has been allocated for this purpose. Stacks reside in RAM just like any other data—the distinction is entirely logical. It should be noted that modern operating systems manage multiple stacks at any given moment—each stack represents a currently active program or thread. I will be discussing threads and how stacks are allocated and managed in Chapter 3.

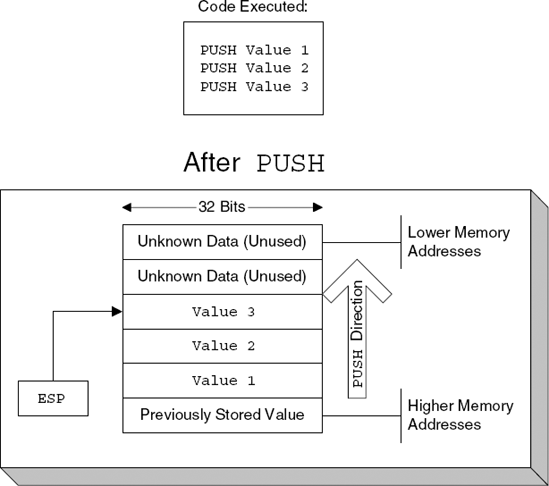

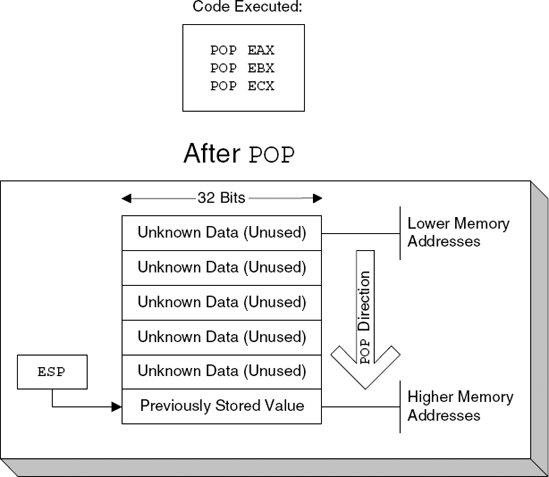

Internally, stacks are managed as simple LIFO (last in, first out) data structures, where items are "pushed" and "popped" onto them. Memory for stacks is typically allocated from the top down, meaning that the highest addresses are allocated and used first and that the stack grows "backward," toward the lower addresses. Figure 2.1. demonstrates what the stack looks like after pushing several values onto it, and Figure 2.2. shows what it looks like after they're popped back out.

A good example of stack usage can be seen in Steps 1 and 6. The machine state that is being stored is usually the values of the registers that will be used in the function. In these cases, register values always go to the stack and are later loaded back from the stack into the corresponding registers.

If you try to translate stack usage to a high-level perspective, you will see that the stack can be used for a number of different things:

Temporarily saved register values: The stack is frequently used for temporarily saving the value of a register and then restoring the saved value to that register. This can be used in a variety of situations—when a procedure has been called that needs to make use of certain registers. In such cases, the procedure might need to preserve the values of registers to ensure that it doesn't corrupt any registers used by its callers.

Local variables: It is a common practice to use the stack for storing local variables that don't fit into the processor's registers, or for variables that must be stored in RAM (there is a variety of reasons why that is needed, such as when we want to call a function and have it write a value into a local variable defined in the current function). It should be noted that when dealing with local variables data is not pushed and popped onto the stack, but instead the stack is accessed using offsets, like a data structure. Again, this will all be demonstrated once you enter the real reversing sessions, in the second part of this book.

Function parameters and return addresses: The stack is used for implementing function calls. In a function call, the caller almost always passes parameters to the callee and is responsible for storing the current instruction pointer so that execution can proceed from its current position once the callee completes. The stack is used for storing both parameters and the instruction pointer for each procedure call.

A heap is a managed memory region that allows for the dynamic allocation of variable-sized blocks of memory in runtime. A program simply requests a block of a certain size and receives a pointer to the newly allocated block (assuming that enough memory is available). Heaps are managed either by software libraries that are shipped alongside programs or by the operating system.

Heaps are typically used for variable-sized objects that are used by the program or for objects that are too big to be placed on the stack. For reversers, locating heaps in memory and properly identifying heap allocation and freeing routines can be helpful, because it contributes to the overall understanding of the program's data layout. For instance, if you see a call to what you know is a heap allocation routine, you can follow the flow of the procedure's return value throughout the program and see what is done with the allocated block, and so on. Also, having accurate size information on heap-allocated objects (block size is always passed as a parameter to the heap allocation routine) is another small hint towards program comprehension.

Another area in program memory that is frequently used for storing application data is the executable data section. In high-level languages, this area typically contains either global variables or preinitialized data. Preinitialized data is any kind of constant, hard-coded information included with the program. Some preinitialized data is embedded right into the code (such as constant integer values, and so on), but when there is too much data, the compiler stores it inside a special area in the program executable and generates code that references it by address. An excellent example of preinitialized data is any kind of hard-coded string inside a program. The following is an example of this kind of string.

char szWelcome = "This string will be stored in the executable's preinitialized data section";

This definition, written in C, will cause the compiler to store the string in the executable's preinitialized data section, regardless of where in the code szWelcome is declared. Even if szWelcome is a local variable declared inside a function, the string will still be stored in the preinitialized data section. To access this string, the compiler will emit a hard-coded address that points to the string. This is easily identified while reversing a program, because hard-coded memory addresses are rarely used for anything other than pointing to the executable's data section.

The other common case in which data is stored inside an executable's data section is when the program defines a global variable. Global variables provide long-term storage (their value is retained throughout the life of the program) that is accessible from anywhere in the program, hence the term global. In most languages, a global variable is defined by simply declaring it outside of the scope of any function. As with preinitialized data, the compiler must use hard-coded memory addresses in order to access global variables, which is why they are easily recognized when reversing a program.

Control flow is one of those areas where the source-code representation really makes the code look user-friendly. Of course, most processors and low-level languages just don't know the meaning of the words if or while. Looking at the low-level implementation of a simple control flow statement is often confusing, because the control flow constructs used in the low-level realm are quite primitive. The challenge is in converting these primitive constructs back into user-friendly high-level concepts.

One of the problems is that most high-level conditional statements are just too lengthy for low-level languages such as assembly language, so they are broken down into sequences of operations. The key to understanding these sequences, the correlation between them, and the high-level statements from which they originated, is to understand the low-level control flow constructs and how they can be used for representing high-level control flow statements. The details of these low-level constructs are platform- and language-specific; we will be discussing control flow statements in IA-32 assembly language in the following section on assembly language.

In order to understand low-level software, one must understand assembly language. For most purposes, assembly language is the language of reversing, and mastering it is an essential step in becoming a real reverser, because with most programs assembly language is the only available link to the original source code. Unfortunately, there is quite a distance between the source code of most programs and the compiler-generated assembly language code we must work with while reverse engineering. But fear not, this book contains a variety of techniques for squeezing every possible bit of information from assembly language programs!

The following sections provide a quick introduction to the world of assembly language, while focusing on the IA-32 (Intel's 32-bit architecture), which is the basis for all of Intel's x86 CPUs from the historical 80386 to the modern-day implementations. I've chosen to focus on the Intel IA-32 assembly language because it is used in every PC in the world and is by far the most popular processor architecture out there. Intel-compatible CPUs, such as those made by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), Transmeta, and so on are mostly identical for reversing purposes because they are object-code-compatible with Intel's processors.

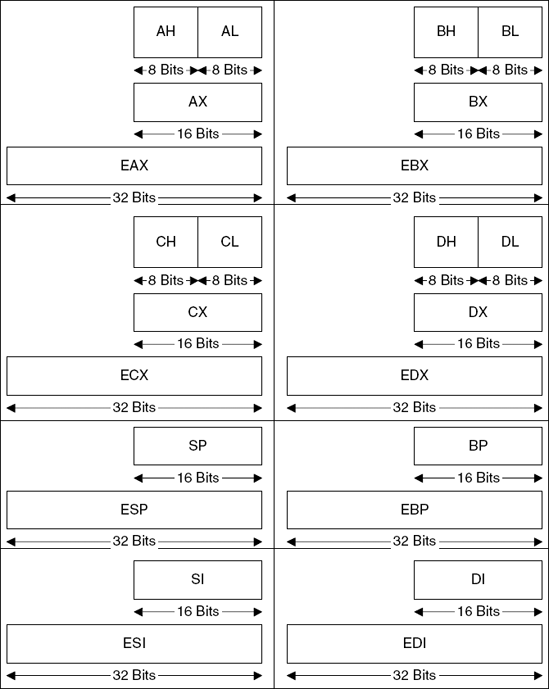

Before starting to look at even the most basic assembly language code, you must become familiar with IA-32 registers, because you'll be seeing them referenced in almost every assembly language instruction you'll ever encounter. For most purposes, the IA-32 has eight generic registers: EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX, ESI, EDI, EBP, and ESP. Beyond those, the architecture also supports a stack of floating-point registers, and a variety of other registers that serve specific system-level requirements, but those are rarely used by applications and won't be discussed here. Conventional program code only uses the eight generic registers.

Table 2.1 provides brief descriptions of these registers and their most common uses.

Notice that all of these names start with the letter E, which stands for extended. These register names have been carried over from the older 16-bit Intel architecture, where they had the exact same names, minus the Es (so that EAX was called AX, etc.). This is important because sometimes you'll run into 32-bit code that references registers in that way: MOV AX, 0x1000, and so on. Figure 2.3. shows all general purpose registers and their various names.

Table 2.1. Generic IA-32 Registers and Their Descriptions

IA-32 processors have a special register called EFLAGS that contains all kinds of status and system flags. The system flags are used for managing the various processor modes and states, and are irrelevant for this discussion. The status flags, on the other hand, are used by the processor for recording its current logical state, and are updated by many logical and integer instructions in order to record the outcome of their actions. Additionally, there are instructions that operate based on the values of these status flags, so that it becomes possible to create sequences of instructions that perform different operations based on different input values, and so on.

In IA-32 code, flags are a basic tool for creating conditional code. There are arithmetic instructions that test operands for certain conditions and set processor flags based on their values. Then there are instructions that read these flags and perform different operations depending on the values loaded into the flags. One popular group of instructions that act based on flag values is the Jcc (Conditional Jump) instructions, which test for certain flag values (depending on the specific instruction invoked) and jump to a specified code address if the flags are set according to the specific conditional code specified.

Let's look at an example to see how it is possible to create a conditional statement like the ones we're used to seeing in high-level languages using flags. Say you have a variable that was called bSuccess in the high-level language, and that you have code that tests whether it is false. The code might look like this:

if (bSuccess == FALSE) return 0;

What would this line look like in assembly language? It is not generally possible to test a variable's value and act on that value in a single instruction—most instructions are too primitive for that. Instead, we must test the value of bSuccess (which will probably be loaded into a register first), set some flags that record whether it is zero or not, and invoke a conditional branch instruction that will test the necessary flags and branch if they indicate that the operand handled in the most recent instruction was zero (this is indicated by the Zero Flag, ZF). Otherwise the processor will just proceed to execute the instruction that follows the branch instruction. Alternatively, the compiler might reverse the condition and branch if bSuccess is nonzero. There are many factors that determine whether compilers reverse conditions or not. This topic is discussed in depth in Appendix A.

Before we start discussing individual assembly language instructions, I'd like to introduce the basic layout of IA-32 instructions. Instructions usually consist of an opcode (operation code), and one or two operands. The opcode is an instruction name such as MOV, and the operands are the "parameters" that the instruction receives (some instructions have no operands). Naturally, each instruction requires different operands because they each perform a different task. Operands represent data that is handled by the specific instruction (just like parameters passed to a function), and in assembly language, data comes in three basic forms:

Register name: The name of a general-purpose register to be read from or written to. In IA-32, this would be something like

EAX,EBX, and so on.Immediate: A constant value embedded right in the code. This often indicates that there was some kind of hard-coded constant in the original program.

Memory address: When an operand resides in RAM, its memory address is enclosed in brackets to indicate that it is a memory address. The address can either be a hard-coded immediate that simply tells the processor the exact address to read from or write to or it can be a register whose value will be used as a memory address. It is also possible to combine a register with some arithmetic and a constant, so that the register represents the base address of some object, and the constant represents an offset into that object or an index into an array.

The general instruction format looks like this:

Instruction Name (opcode) Destination Operand, Source Operand

Some instructions only take one operand, whose purpose depends on the specific instruction. Other instructions take no operands and operate on predefined data. Table 2.2 provides a few typical examples of operands and explains their meanings.

Now that you're familiar with the IA-32 registers, we can move on to some basic instructions. These are popular instructions that appear everywhere in a program. Please note that this is nowhere near an exhaustive list of IA-32 instructions. It is merely an overview of the most common ones. For detailed information on each instruction refer to the IA-32 Intel Architecture Software Developer's Manual, Volume 2A and Volume 2B [Intel2, Intel3]. These are the (freely available) IA-32 instruction set reference manuals from Intel.

Table 2.2. Examples of Typical Instruction Operands and Their Meanings

Operand | Description |

|---|---|

| Simply references |

| An immediate number embedded in the code (like a constant) |

| An immediate hard-coded memory address—this can be a global variable access |

The MOV instruction is probably the most popular IA-32 instruction. MOV takes two operands: a destination operand and a source operand, and simply moves data from the source to the destination. The destination operand can be either a memory address (either through an immediate or using a register) or a register. The source operand can be an immediate, register, or memory address, but note that only one of the operands can contain a memory address, and never both. This is a generic rule in IA-32 instructions: with a few exceptions, most instructions can only take one memory operand. Here is the "prototype" of the MOV instruction:

MOV DestinationOperand, SourceOperand

Please see the "Examples" section later in this chapter to get a glimpse of how MOV and other instructions are used in real code.

For basic arithmetic operations, the IA-32 instruction set includes six basic integer arithmetic instructions: ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV, IMUL, and IDIV. The following table provides the common format for each instruction along with a brief description. Note that many of these instructions support other configurations, with different sets of operands. Table 2.3 shows the most common configuration for each instruction.

Table 2.3. Typical Configurations of Basic IA-32 Arithmetic Instructions

DESCRIPTION | |

|---|---|

| Adds two signed or unsigned integers. The result is typically stored in |

| Subtracts the value at |

| Multiplies the unsigned operand by |

| Divides the unsigned 64-bit value stored in |

| Multiplies the signed operand by |

| Divides the signed 64-bit value stored in |

Operands are compared using the CMP instruction, which takes two operands:

CMP Operand1, Operand2

CMP records the result of the comparison in the processor's flags. In essence, CMP simply subtracts Operand2 from Operand1 and discards the result, while setting all of the relevant flags to correctly reflect the outcome of the subtraction. For example, if the result of the subtraction is zero, the Zero Flag (ZF) is set, which indicates that the two operands are equal. The same flag can be used for determining if the operands are not equal, by testing whether ZF is not set. There are other flags that are set by CMP that can be used for determining which operand is greater, depending on whether the operands are signed or unsigned. For more information on these specific flags refer to Appendix A.

Conditional branches are implemented using the Jcc group of instructions. These are instructions that conditionally branch to a specified address, based on certain conditions. Jcc is just a generic name, and there are quite a few different variants. Each variant tests a different set of flag values to decide whether to perform the branch or not. The specific variants are discussed in Appendix A.

The basic format of a conditional branch instruction is as follows:

Jcc TargetCodeAddress

If the specified condition is satisfied, Jcc will just update the instruction pointer to point to TargetCodeAddress (without saving its current value). If the condition is not satisfied, Jcc will simply do nothing, and execution will proceed at the following instruction.

Function calls are implemented using two basic instructions in assembly language. The CALL instruction calls a function, and the RET instruction returns to the caller. The CALL instruction pushes the current instruction pointer onto the stack (so that it is later possible to return to the caller) and jumps to the specified address. The function's address can be specified just like any other operand, as an immediate, register, or memory address. The following is the general layout of the CALL instruction.

CALL FunctionAddress

When a function completes and needs to return to its caller, it usually invokes the RET instruction. RET pops the instruction pointer pushed to the stack by CALL and resumes execution from that address. Additionally, RET can be instructed to increment ESP by the specified number of bytes after popping the instruction pointer. This is needed for restoring ESP back to its original position as it was before the current function was called and before any parameters were pushed onto the stack. In some calling conventions the caller is responsible for adjusting ESP, which means that in such cases RET will be used without any operands, and that the caller will have to manually increment ESP by the number of bytes pushed as parameters. Detailed information on calling conventions is available in Appendix C.

Let's have a quick look at a few short snippets of assembly language, just to make sure that you understand the basic concepts. Here is the first example:

cmp ebx,0xf020 jnz 10026509

The first instruction is CMP, which compares the two operands specified. In this case CMP is comparing the current value of register EBX with a constant: 0xf020 (the "0x" prefix indicates a hexadecimal number), or 61,472 in decimal. As you already know, CMP is going to set certain flags to reflect the outcome of the comparison. The instruction that follows is JNZ. JNZ is a version of the Jcc (conditional branch) group of instructions described earlier. The specific version used here will branch if the zero flag (ZF) is not set, which is why the instruction is called JNZ (jump if not zero). Essentially what this means is that the instruction will jump to the specified code address if the operands compared earlier by CMP are not equal. That is why JNZ is also called JNE (jump if not equal). JNE and JNZ are two different mnemonics for the same instruction—they actually share the same opcode in the machine language.

Let's proceed to another example that demonstrates the moving of data and some arithmetic.

mov edi,[ecx+0x5b0] mov ebx,[ecx+0x5b4] imul edi,ebx

This sequence starts with an MOV instruction that reads an address from memory into register EDI. The brackets indicate that this is a memory access, and the specific address to be read is specified inside the brackets. In this case, MOV will take the value of ECX, add 0x5b0 (1456 in decimal), and use the result as a memory address. The instruction will read 4 bytes from that address and write them into EDI. You know that 4 bytes are going to be read because of the register specified as the destination operand. If the instruction were to reference DI instead of EDI, you would know that only 2 bytes were going to be read. EDI is a full 32-bit register (see Figure 2.3 for an illustration of IA-32 registers and their sizes).

The following instruction reads another memory address, this time from ECX plus 0x5b4 into register EBX. You can easily deduce that ECX points to some kind of data structure. 0x5b0 and 0x5b4 are offsets to some members within that data structure. If this were a real program, you would probably want to try and figure out more information regarding this data structure that is pointed to by ECX. You might do that by tracing back in the code to see where ECX is loaded with its current value. That would tell you where this structure's address is obtained, and might shed some light on the nature of this data structure. I will be demonstrating all kinds of techniques for investigating data structures in the reversing examples throughout this book.

The final instruction in this sequence is an IMUL (signed multiply) instruction. IMUL has several different forms, but when specified with two operands as it is here, it means that the first operand is multiplied by the second, and that the result is written into the first operand. This means that the value of EDI will be multiplied by the value of EBX and that the result will be written back into EDI.

If you look at these three instructions as a whole, you can get a good idea of their purpose. They basically take two different members of the same data structure (whose address is taken from ECX), and multiply them. Also, because IMUL is used, you know that these members are signed integers, apparently 32-bits long. Not too bad for three lines of assembly language code!

For the final example, let's have a look at what an average function call sequence looks like in IA-32 assembly language.

push eax push edi push ebx push esi push dword ptr [esp+0x24] call 0x10026eeb

This sequence pushes five values into the stack using the PUSH instruction. The first four values being pushed are all taken from registers. The fifth and final value is taken from a memory address at ESP plus 0x24. In most cases, this would be a stack address (ESP is the stack pointer), which would indicate that this address is either a parameter that was passed to the current function or a local variable. To accurately determine what this address represents, you would need to look at the entire function and examine how it uses the stack. I will be demonstrating techniques for doing this in Chapter 5.

It would be safe to say that 99 percent of all modern software is implemented using high-level languages and goes through some sort of compiler prior to being shipped to customers. Therefore, it is also safe to say that most, if not all, reversing situations you'll ever encounter will include the challenge of deciphering the back-end output of one compiler or another.

Because of this, it can be helpful to develop a general understanding of compilers and how they operate. You can consider this a sort of "know your enemy" strategy, which will help you understand and cope with the difficulties involved in deciphering compiler-generated code.

Compiler-generated code can be difficult to read. Sometimes it is just so different from the original code structure of the program that it becomes difficult to determine the software developer's original intentions. A similar problem happens with arithmetic sequences: they are often rearranged to make them more efficient, and one ends up with an odd looking sequence of arithmetic operations that might be very difficult to comprehend. The bottom line is that developing an understanding of the processes undertaken by compilers and the way they "perceive" the code will help in eventually deciphering their output.

The following sections provide a bit of background information on compilers and how they operate, and describe the different stages that take place inside the average compiler. While it is true that the following sections could be considered optional, I would still recommend that you go over them at some point if you are not familiar with basic compilation concepts. I firmly believe that reversers must truly know their systems, and no one can truly claim to understand the system without understanding how software is created and built.

It should be emphasized that compilers are extremely complex programs that combine a variety of fields in computer science research and can have millions of lines of code. The following sections are by no means comprehensive—they merely scratch the surface. If you'd like to deepen your knowledge of compilers and compiler optimizations, you should check out [Cooper] Keith D. Copper and Linda Torczon. Engineering a Compiler. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2004, for a highly readable tutorial on compilation techniques, or [Muchnick] Steven S. Muchnick. Advanced Compiler Design and Implementation. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 1997, for a more detailed discussion of advanced compilation materials such as optimizations, and so on.

At its most basic level, a compiler is a program that takes one representation of a program as its input and produces a different representation of the same program. In most cases, the input representation is a text file containing code that complies with the specifications of a certain high-level programming language. The output representation is usually a lower-level translation of the same program. Such lower-level representation is usually read by hardware or software, and rarely by people. The bottom line is usually that compilers transform programs from their high-level, human-readable form into a lower-level, machine-readable form.

During the translation process, compilers usually go through numerous improvement or optimization steps that take advantage of the compiler's "understanding" of the program and employ various algorithms to improve the code's efficiency. As I have already mentioned, these optimizations tend to have a strong "side effect": they seriously degrade the emitted code's readability. Compiler-generated code is simply not meant for human consumption.

The average compiler consists of three basic components. The front end is responsible for deciphering the original program text and for ensuring that its syntax is correct and in accordance with the language's specifications. The optimizer improves the program in one way or another, while preserving its original meaning. Finally, the back end is responsible for generating the platform-specific binary from the optimized code emitted by the optimizer. The following sections discuss each of these components in depth.

The compilation process begins at the compiler's front end and includes several steps that analyze the high-level language source code. Compilation usually starts with a process called lexical analysis or scanning, in which the compiler goes over the source file and scans the text for individual tokens within it. Tokens are the textual symbols that make up the code, so that in a line such as:

if (Remainder != 0)

The symbols if, (, Remainder, and != are all tokens. While scanning for tokens, the lexical analyzer confirms that the tokens produce legal "sentences" in accordance with the rules of the language. For example, the lexical analyzer might check that the token if is followed by a (, which is a requirement in some languages. Along with each word, the analyzer stores the word's meaning within the specific context. This can be thought of as a very simple version of how humans break sentences down in natural languages. A sentence is divided into several logical parts, and words can only take on actual meaning when placed into context. Similarly, lexical analysis involves confirming the legality of each token within the current context, and marking that context. If a token is found that isn't expected within the current context, the compiler reports an error.

A compiler's front end is probably the one component that is least relevant to reversers, because it is primarily a conversion step that rarely modifies the program's meaning in any way—it merely verifies that it is valid and converts it to the compiler's intermediate representation.

When you think about it, compilers are all about representations. A compiler's main role is to transform code from one representation to another. In the process, a compiler must generate its own representation for the code. This intermediate representation (or internal representation, as it's sometimes called), is useful for detecting any code errors, improving upon the code, and ultimately for generating the resulting machine code.

Properly choosing the intermediate representation of code in a compiler is one of the compiler designer's most important design decisions. The layout heavily depends on what kind of source (high-level language) the compiler takes as input, and what kind of object code the compiler spews out. Some intermediate representations can be very close to a high-level language and retain much of the program's original structure. Such information can be useful if advanced improvements and optimizations are to be performed on the code. Other compilers use intermediate representations that are closer to a low-level assembly language code. Such representations frequently strip much of the high-level structures embedded in the original code, and are suitable for compiler designs that are more focused on the low-level details of the code. Finally, it is not uncommon for compilers to have two or more intermediate representations, one for each stage in the compilation process.

Being able to perform optimizations is one of the primary reasons that reversers should understand compilers (the other reason being to understand code-level optimizations performed in the back end). Compiler optimizers employ a wide variety of techniques for improving the efficiency of the code. The two primary goals for optimizers are usually either generating the most high-performance code possible or generating the smallest possible program binaries. Most compilers can attempt to combine the two goals as much as possible.

Optimizations that take place in the optimizer are not processor-specific and are generic improvements made to the original program's code without any relation to the specific platform to which the program is targeted. Regardless of the specific optimizations that take place, optimizers must always preserve the exact meaning of the original program and not change its behavior in any way.

The following sections briefly discuss different areas where optimizers can improve a program. It is important to keep in mind that some of the optimizations that strongly affect a program's readability might come from the processor-specific work that takes place in the back end, and not only from the optimizer.

Optimizers frequently modify the structure of the code in order to make it more efficient while preserving its meaning. For example, loops can often be partially or fully unrolled. Unrolling a loop means that instead of repeating the same chunk of code using a jump instruction, the code is simply duplicated so that the processor executes it more than once. This makes the resulting binary larger, but has the advantage of completely avoiding having to manage a counter and invoke conditional branches (which are fairly inefficient—see the section on CPU pipelines later in this chapter). It is also possible to partially unroll a loop so that the number of iterations is reduced by performing more than one iteration in each cycle of the loop.

When going over switch blocks, compilers can determine what would be the most efficient approach for searching for the correct case in runtime. This can be either a direct table where the individual blocks are accessed using the operand, or using different kinds of tree-based search approaches.

Another good example of a code structuring optimization is the way that loops are rearranged to make them more efficient. The most common high-level loop construct is the pretested loop, where the loop's condition is tested before the loop's body is executed. The problem with this construct is that it requires an extra unconditional jump at the end of the loop's body in order to jump back to the beginning of the loop (for comparison, posttested loops only have a single conditional branch instruction at the end of the loop, which makes them more efficient). Because of this, it is common for optimizers to convert pretested loops to posttested loops. In some cases, this requires the insertion of an if statement before the beginning of the loop, so as to make sure the loop is not entered when its condition isn't satisfied.

Code structure optimizations are discussed in more detail in Appendix A.

Redundancy elimination is a significant element in the field of code optimization that is of little interest to reversers. Programmers frequently produce code that includes redundancies such as repeating the same calculation more than once, assigning values to variables without ever using them, and so on. Optimizers have algorithms that search for such redundancies and eliminate them.

For example, programmers routinely leave static expressions inside loops, which is wasteful because there is no need to repeatedly compute them—they are unaffected by the loop's progress. A good optimizer identifies such statements and relocates them to an area outside of the loop in order to improve on the code's efficiency.

Optimizers can also streamline pointer arithmetic by efficiently calculating the address of an item within an array or data structure and making sure that the result is cached so that the calculation isn't repeated if that item needs to be accessed again later on in the code.

A compiler's back end, also sometimes called the code generator, is responsible for generating target-specific code from the intermediate code generated and processed in the earlier phases of the compilation process. This is where the intermediate representation "meets" the target-specific language, which is usually some kind of a low-level assembly language.

Because the code generator is responsible for the actual selection of specific assembly language instructions, it is usually the only component that has enough information to apply any significant platform-specific optimizations. This is important because many of the transformations that make compiler-generated assembly language code difficult to read take place at this stage.

The following are the three of the most important stages (at least from our perspective) that take place during the code generation process:

Instruction selection: This is where the code from the intermediate representation is translated into platform-specific instructions. The selection of each individual instruction is very important to overall program performance and requires that the compiler be aware of the various properties of each instruction.

Register allocation: In many intermediate representations there is an unlimited number of registers available, so that every local variable can be placed in a register. The fact that the target processor has a limited number of registers comes into play during code generation, when the compiler must decide which variable gets placed in which register, and which variable must be placed on the stack.

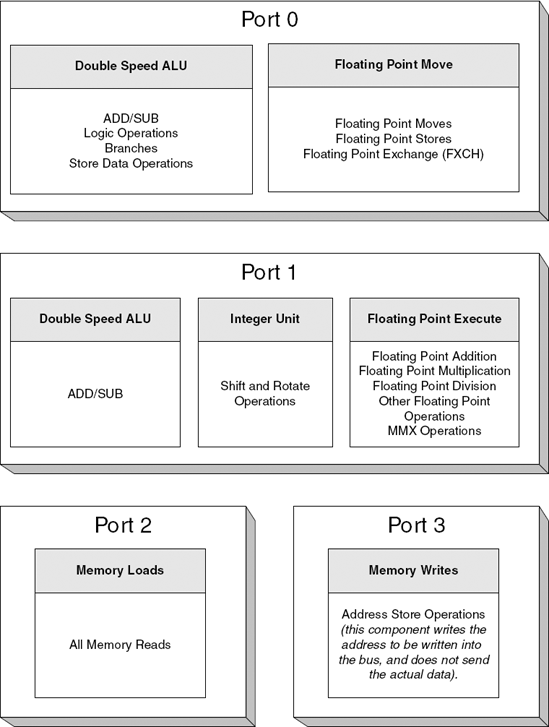

Instruction scheduling: Because most modern processors can handle multiple instructions at once, data dependencies between individual instructions become an issue. This means that if an instruction performs an operation and stores the result in a register, immediately reading from that register in the following instruction would cause a delay, because the result of the first operation might not be available yet. For this reason the code generator employs platform-specific instruction scheduling algorithms that reorder instructions to try to achieve the highest possible level of parallelism. The end result is interleaved code, where two instruction sequences dealing with two separate things are interleaved to create one sequence of instructions. We will be seeing such sequences in many of the reversing sessions in this book.

A listing file is a compiler-generated text file that contains the assembly language code produced by the compiler. It is true that this information can be obtained by disassembling the binaries produced by the compiler, but a listing file also conveniently shows how each assembly language line maps to the original source code. Listing files are not strictly a reversing tool but more of a research tool used when trying to study the behavior of a specific compiler by feeding it different code and observing the output through the listing file.

Most compilers support the generation of listing files during the compilation process. For some compilers, such as GCC, this is a standard part of the compilation process because the compiler doesn't directly generate an object file, but instead generates an assembly language file which is then processed by an assembler. In such compilers, requesting a listing file simply means that the compiler must not delete it after the assembler is done with it. In other compilers (such as the Microsoft or Intel compilers), a listing file is an optional feature that must be enabled through the command line.

Any compiled code sample discussed in this book has been generated with one of three compilers (this does not include third-party code reversed in the book):

GCC and G++ version 3.3.1: The GNU C Compiler (GCC) and GNU C++ Compiler (G++) are popular open-source compilers that generate code for a large number of different processors, including IA-32. The GNU compilers (also available for other high-level languages) are commonly used by developers working on Unix-based platforms such as Linux, and most Unix platforms are actually built using them. Note that it is also possible to write code for Microsoft Windows using the GNU compilers. The GNU compilers have a powerful optimization engine that usually produces results similar to those of the other two compilers in this list. However, the GNU compilers don't seem to have a particularly aggressive IA-32 code generator, probably because of their ability to generate code for so many different processors. On one hand, this frequently makes the IA-32 code generated by them slightly less efficient compared to some of the other popular IA-32 compilers. On the other hand, from a reversing standpoint this is actually an advantage because the code they produce is often slightly more readable, at least compared to code produced by the other compilers discussed here.

Microsoft C/C++ Optimizing Compiler version 13.10.3077: The Microsoft Optimizing Compiler is one of the most common compilers for the Windows platform. This compiler is shipped with the various versions of Microsoft Visual Studio, and the specific version used throughout this book is the one shipped with Microsoft Visual C++ .NET 2003.