Most of this book describes how to reverse engineer programs in order to get an insight into their internal workings. This chapter discusses a slightly different aspect of this craft: the general process of deciphering program data. This data can be an undocumented file format, a network protocol, and so on. The process of deciphering such data to the point where it is possible to actually use it for the creation of programs that can accept and produce compatible data is another branch of reverse engineering that is often referred to as data reverse engineering. This chapter demonstrates data reverse-engineering techniques and shows what can be done with them.

The most common reason for performing any kind of data reverse engineering is to achieve interoperability with a third party's software product. There are countless commercial products out there that use proprietary, undocumented data formats. These can be undocumented file formats or networking protocols that cannot be accessed by any program other than those written by the original owner of the format—no one else knows the details of the proprietary format. This is a major inconvenience to end users because they cannot easily share their files with people that use a competing program—only the products developed by the owner of the file format can access the proprietary file format.

This is where data reverse engineering comes into play. Using data reverse engineering techniques it is possible to obtain that missing information regarding a proprietary data format, and write code that reads or even generates data in the proprietary format. There are numerous real-world examples where this type of reverse engineering has been performed in order to achieve interoperability between the data formats of popular commercial products. Consider Microsoft Word for example. This program has an undocumented file format (the famous .doc format), so in order for third-party programs to be able to open or create .doc files (and there are actually quite a few programs that do that) someone had to reverse engineer the Microsoft Word file format. This is exactly the type of reverse engineering demonstrated in this chapter.

Cryptex is a little program I've written as a data reverse-engineering exercise. It is basically a command-line data encryption tool that can encrypt files using a password. In this chapter, you will be analyzing the Cryptex file format up to the point where you could theoretically write a program that reads or writes into such files. I will also take this opportunity to demonstrate how you can use reversing techniques to evaluate the level of security offered by these types of programs.

Cryptex manages archive files (with the extension .crx) that can contain multiple encrypted files, just like other file archiving formats such as Zip, and so on. Cryptex supports adding an unlimited number of files into a single archive. The size of each individual file and of the archive itself is unlimited.

Cryptex encrypts files using the 3DES encryption algorithm. 3DES is an enhanced version of the original (and extremely popular) DES algorithm, designed by IBM in 1976. The basic DES (Data Encryption Standard) algorithm uses a 56-bit key to encrypt data. Because modern computers can relatively easily find a 56-bit key using brute-force methods, the keys must be made longer. The 3DES algorithm simply uses three different 56-bit keys and encrypts the plaintext three times using the original DES algorithm, each time with a different key.

3DES (or triple-DES) effectively uses a 168-bit key (56 times 3). In Cryptex, this key is produced from a textual password supplied while running the program. The actual level of security obtained by using the program depends heavily on the passwords used. On one hand, if you encrypt files using a trivial password such as "12345" or your own name, you will gain very little security because it would be trivial to implement a dictionary-based brute-force attack and easily recover the decryption key. If, on the other hand, you use long and unpredictable passwords such as "j8&1`#:#mAkQ)d*" and keep those passwords safe, Cryptex would actually provide a fairly high level of security.

Before actually starting to reverse Cryptex, let's play with it a little bit so you can learn how it works. In general, it is important to develop a good understanding of a program and its user interface before attempting to reverse it. In a commercial product, you would be reading the user manual at this point.

Cryptex is a console-mode application, which means that it doesn't have any GUI—it is operated using command-line options, and it provides feedback through a console window. In order to properly launch Cryptex, you'll need to open a Command Prompt window and run Cryptex.exe within it. The best way to start is by simply running Cryptex.exe without any command-line options. Cryptex displays a welcome screen that also includes its "user's manual"—a quick reference for the supported commands and how they can be used. Listing 6.1 shows the Cryptex welcome and help screen.

Example 6.1. Cryptex.exe's welcome screen.

Cryptex 1.0 - Written by Eldad Eilam

Usage: Cryptex <Command> <Archive-Name> <Password> [FileName]

Supported Commands:

'a', 'e': Encrypts a file. Archive will be created if it doesn't

already exist.

'x', 'o': Decrypts a file. File will be decrypted into the current

directory.

'l' : Lists all files in the specified archive.

'd', 'r': Deletes the specified file from the archive.

Password is an unlimited-length string that can contain any

combination of letters, numbers, and symbols. For maximum

security it is recommended that the password be made as long

as possible and that it be made up of a random sequence of

many different characters, digits, and symbols. Passwords are

case-sensitive. An archive's password is established while it

is created. It cannot be changed afterwards and must be specified

whenever that particular archive is accessed.

Examples:

Encrypting a file: "Cryptex a MyArchive s8Uj~ c:\ mydox\ myfile.doc"

Encrypting multiple files: "Cryptex a MyArchive s8Uj~ c:\ mydox\ *.doc"

Decrypting a file: "Cryptex x MyArchive s8Uj~ file.doc"

Listing the contents of an archive: "Cryptex l MyArchive s8Uj~"

Deleting a file from an archive: "Cryptex d MyArchive s8Uj~ myfile.doc"Cryptex is quite straightforward to use, with only four supported commands. Files are encrypted using a user-supplied password, and the program supports deleting files from the archive and extracting files from it. It is also possible to add multiple files with one command using wildcards such as *.doc.

There are several reasons that could justify deciphering the file format of a program such as Cryptex. First of all, it is the only way to evaluate the level of security offered by the product. Let's say that an organization wants to use such a product for archiving and transmitting critical information. Should they rely on the author's guarantees regarding the product's security level? Perhaps the author has installed some kind of a back door that would allow him or her to easily decrypt any file created by the program? Perhaps the program is poorly written and employs some kind of a home-made, trivial encryption algorithm. Perhaps (and this is more common than you would think) the program incorrectly uses a strong, industry-standard encryption algorithm in a way that compromises the security of the encrypted files.

File formats are also frequently reversed for compatibility and interoperability purposes. For instance, consider the (very likely) possibility that Cryptex became popular to the point where other software vendors would be interested in adding Cryptex-compatibility to their programs. Unless the .crx Cryptex file format was published, the only way to accomplish this would be by reversing the file format. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that the data reverse-engineering journey we're about to embark on is not specifically tied to file formats; the process could be easily applied to networking protocols.

How does one begin to reverse a file format? In most cases, the answer is to create simple, tiny files that contain known, easy-to-spot values. In the case of Cryptex, this boils down to creating one or more small archives that contain a single file with easily recognizable contents.

This approach is very helpful, but it is not always going to be feasible. For example, with some file formats you might only have access to code that reads from the file, but not to the code that generates files using that format. This would greatly increase the complexity of the reversing process, because it would limit our options. In such cases, you would usually need to spend significant amounts of time studying the code that reads your file format. In most cases, a thorough analysis of such code would provide most of the answers.

Luckily, in this particular case Cryptex lets you create as many archives as you please, so you can freely experiment. The best idea at this point would be to take a simple text file containing something like a long sequence of a single character such as "*****************************" and to encode it into an archive file. Additionally, I would recommend trying out some long and repetitive password, to try and see if, God forbid, the password is somehow stored in the file. It also makes sense to quickly scan the file for the original name of the encrypted file, to see if Cryptex encrypts the actual file table, or just the actual file contents. Let's start out by creating a tiny file called asterisks.txt, and fill it with a long sequence of asterisks (I created a file about 1K long). Then proceed to creating a Cryptex archive that contains the asterisks.txt file. Let's use the string 6666666666 as the password.

Cryptex a Test1 6666666666 asterisks.txt

Cryptex provides the following feedback.

Cryptex 1.0 - Written by Eldad Eilam Archive "Test1.crx" does not exist. Creating a new archive. Adding file "asterisks.txt" to archive "Test1". Encrypting "asterisks.txt" - 100.00 percent completed.

Interestingly, if you check the file size for Test1.crx, it is far larger than expected, at 8,248 bytes! It looks as if Cryptex archives have quite a bit of overhead—you'll soon see why that is. Before actually starting to look inside the file, let's ask Cryptex to show its contents, just to see how Cryptex views it. You can do this using the L command in Cryptex, which lists the files contained in the given archive. Note that Cryptex requires the archive's password on every command, including the list command.

Cryptex l Test1 6666666666

Cryptex produces the following output.

Cryptex 1.0 - Written by Eldad Eilam

Listing all files in archive "Test1".

File Size File Name

3K asterisks.txt

Total files listed: 1 Total size: 3KThere aren't a whole lot of surprises in this output, but there's one somewhat interesting point: the asterisks.txt file was originally 1K and is shown here as being 3K long. Why has the file expanded by 2K? Let's worry about that later. For now, let's try one more thing: it is going to be interesting to see how Cryptex responds when an incorrect password is supplied and whether it always requires a password, even for a mere file listing. Run Cryptex with the following command line:

Cryptex l Test1 6666666665

Unsurprisingly, Cryptex provides the following response:

Cryptex 1.0 - Written by Eldad Eilam Listing all files in archive "Test1". ERROR: Invalid password. Unable to process file.

So, Cryptex actually confirms the password before providing the list of files. This might seem like a futile exercise, considering that the documentation explicitly said that the password is always required. However, the exact text of the invalid-password message is useful because you can later look for the code that displays it in the program and try to determine how it establishes whether or not the password is correct.

For now, let's start looking inside the Cryptex archive files. For this purpose any hex dump tool would do just fine—there are quite a few free products online, but if you're willing to invest a little money in it, Hex Workshop is one of the more powerful data-reversing tools. Here are the first 64 bytes of the Test1.crx file just produced.

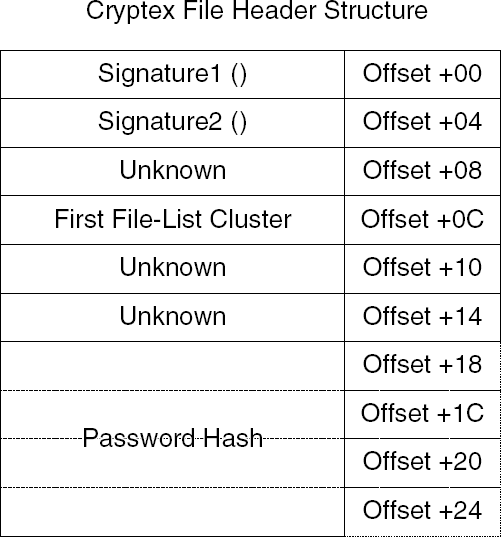

00000000 4372 5970 5465 5839 0100 0000 0100 0000 CrYpTeX9........ 00000010 0000 0000 0200 0000 5F60 43BC 26F0 F7CA ........_'C.&... 00000020 6816 0D2B 99E7 FA61 BEB1 DA78 C0F6 4D89 h..+...a...x..M. 00000030 7CC7 82E8 01F5 3CB9 549D 2EC9 868F 1FFD |.....<.T.......

Like most file formats, .crx files start out with a signature, CrYpTeX9 in this case, followed by what looks like several data fields, and continuing into an apparently random byte sequence starting at address 0x18. If you look at the rest of the file, it all contains similarly unreadable junk. This indicates that the entire contents of the file have been encrypted, including the file table. As expected, none of the key strings such as the password, the asterisks.txt file name, or the actual asterisks can be found within this file. As further evidence that the file has been encrypted, we can use the Character Distribution feature in Hex Workshop to get an overview of the data within the file. Interestingly, we discover that the file contains seemingly random data, with an almost equal character distribution of about 0.4 percent for each of the 256 characters. It looks like the encryption algorithm applied by Cryptex has completely eliminated any obvious resemblance between the encrypted data and the password, file name, or file contents.

At this point, it becomes clear that you're going to have to dig into the program in order to truly decipher the .crx file format. This is exactly where conventional code reversing and data reversing come together: you must look inside the program in order to see how it manages its data. Granted, this program is an extreme example because the data is encrypted, but even with programs that don't intentionally hide the contents of their file formats, it is often very difficult to decipher a file format by merely observing the data.

The first step you must take in order to get an overview of Cryptex and how it works is to obtain a list of its imported functions. This can be done using any executable dumping tool such as those discussed in Chapter 4; I often choose Microsoft's DUMPBIN, which is a command-line tool. The import list is important because it will provide us with an overview of how Cryptex does some of the things that it does. For example, how does it read and write to the archive files? Does it use a section object, does it call into some kind of runtime library file I/O functions, or does it directly call into the Win32 file I/O APIs?

Establishing which system (and other) services the program utilizes is critical because in order to track Cryptex's I/O accesses (which is what you're going to have to do in order to find the logic that generates and deciphers .crx files) you're going to have to place breakpoints on these function calls. Listing 6.2 provides (abridged) DUMPBIN output that lists imports from Cryptex.exe.

Example 6.2. A list of all functions called from Cryptex.EXE, produced using DUMPBIN.

KERNEL32.dll

138 GetCurrentDirectoryA

D3 FindNextFileA

1B1 GetStdHandle

15C GetFileSizeEx

12F GetConsoleScreenBufferInfo

2E5 SetConsoleCursorPosition

2E CloseHandle

4D CreateFileA

303 SetEndOfFile

394 WriteFile

2A9 ReadFile

169 GetLastError

C9 FindFirstFileA

30E SetFilePointer

13B GetCurrentProcessId

13E GetCurrentThreadId

1C0 GetSystemTimeAsFileTime

1D5 GetTickCount

297 QueryPerformanceCounter

177 GetModuleHandleA

AF ExitProcess

ADVAPI32.dll

8C CryptDestroyKey

A0 CryptReleaseContext

8A CryptDeriveKey

88 CryptCreateHash

9D CryptHashData99 CryptGetHashParam

8B CryptDestroyHash

8F CryptEncrypt

89 CryptDecrypt

85 CryptAcquireContextA

MSVCR71.dll

CA _c_exit

FA _exit

4B _XcptFilter

CD _cexit

7C __p___initenv

C2 _amsg_exit

6E __getmainargs

13F _initterm

9F __setusermatherr

BB _adjust_fdiv

82 __p__commode

87 __p__fmode

9C __set_app_type

6B __dllonexit

1B8 _onexit

DB _controlfp

F1 _except_handler3

9B __security_error_handler

300 sprintf

305 strchr

2EC printf

297 exit

30F strncpy

1FE _stricmpLet's go through each of the modules in Listing 6.2 and examine what it's revealing about how Cryptex works. Keep in mind that not all of these entries are directly called by Cryptex. Most programs statically link with other libraries (such as runtime libraries), which make their own calls into the operating system or into other DLLs.

The entries in KERNEL32.dll are highly informative because they're telling us that Cryptex apparently uses direct calls into Win32 File I/O APIs such as CreateFile, ReadFile, WriteFile, and so on. The following section in Listing 6.2 is also informative and lists functions called from the ADVAPI32.dll module. A quick glance at the function names reveals a very important detail about Cryptex: It uses the Windows Crypto API (this is easy to spot with function names such as CryptEncrypt and CryptDecrypt).

The Windows Crypto API is a generic cryptographic library that provides support for installable cryptographic service providers (CSPs) and can be used for encrypting and decrypting data using a variety of cryptographic algorithms. Microsoft provides several CSPs that aren't built into Windows and support a wide range of symmetric and asymmetric cryptographic algorithms such as DES, RSA, and AES. The fact that Cryptex uses the Crypto API can be seen as good news, because it means that it is going to be quite trivial to determine which encryption algorithms the program employs and how it produces the encryption keys. This would have been more difficult if Cryptex were to use a built-in implementation of the encryption algorithm because you would have to reverse it to determine exactly which algorithm it is and whether it is properly implemented.

The next entry in Listing 6.2 is MSVCR71.DLL, which is the Visual C++ runtime library DLL. In this list, you can see the list of runtime library functions called by Cryptex. This doesn't really tell you much, except for the presence of the printf function, which is used for printing messages to the console window. The printf function is what you'd look at if you wanted to catch moments where Cryptex is printing certain messages to the console window.

One basic step that is relatively simple and is likely to reveal much about how Cryptex goes about its business is to find out how it knows whether or not the user has typed the correct password. This will also be a good indicator of whether or not Cryptex is secure (depending on whether the password or some version of it is actually stored in the archive).

The easiest way to go about checking Cryptex's password verification process is to create an archive (Test1.crx from earlier in this chapter would do just fine), and to start Cryptex in a debugger, feeding it with an incorrect password. You would then try to catch the place in the code where Cryptex notifies the user that a bad password has been supplied. This is easy to accomplish because you know from Listing 6.2 that Cryptex uses the printf runtime library function. It is very likely that you'll be able to catch a printf call that contains the "bad password" message, and trace back from that call to see how Cryptex made the decision to print that message.

Start by loading the program in any debugger, preferably a user-mode one such as WinDbg or OllyDbg (I personally picked OllyDbg), and placing a breakpoint on the printf function from MSVCR71.DLL. Notice that unlike the previous reversing session where you relied exclusively on dead listing, this time you have a real program to work with, so you can easily perform this reversing session from within a debugger.

Before actually launching the program you must also set the launch parameters so that Cryptex knows which archive you're trying to open. Keep in mind that you must type an incorrect password, so that Cryptex generates its incorrect password message. As for which command to have Cryptex perform, it would probably be best to just have Cryptex list the files in the archive, so that nothing is actually written into the archive (though Cryptex is unlikely to change anything when supplied with a bad password anyway). I personally used Cryptex l test1 6666666665, and placed a breakpoint on printf from the MSVCR71.DLL (using the Executable Modules window in OllyDbg and then listing its exports in the Names window).

Upon starting the program, three calls to printf were caught. The first contained the Cryptex 1.0 . . . message, the second contained the Listing all file . . . message, and the third contained what you were looking for: the ERROR: Invalid password . . . string. From here, all you must do is jump back to the caller and hopefully locate the logic that decides whether to accept or reject the password that was passed in. Once you hit that third printf, you can use Ctrl+F9 in Olly to go to the RET instruction that will take you directly into the function that made the call to printf. This function is given in Listing 6.3.

Example 6.3. Cryptex's header-verification function that reads the Cryptex archive header and checks the supplied password.

004011C0 PUSH ECX 004011C1 PUSH ESI 004011C2 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+C] 004011C6 PUSH 0 ; Origin = FILE_BEGIN 004011C8 PUSH 0 ; pOffsetHi = NULL 004011CA PUSH 0 ; OffsetLo = 0 004011CC PUSH ESI ; hFile 004011CD CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.SetFilePointer>] 004011D3 PUSH 0 ; pOverlapped = NULL 004011D5 LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+8] 004011D9 PUSH EAX ; pBytesRead 004011DA PUSH 28 ; BytesToRead = 28 (40.) 004011DC PUSH cryptex.00406058 ; Buffer = cryptex.00406058 004011E1 PUSH ESI ; hFile 004011E2 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.ReadFile>] ; ReadFile 004011E8 TEST EAX,EAX 004011EA JNZ SHORT cryptex.004011EF 004011EC POP ESI 004011ED POP ECX 004011EE RETN 004011EF CMP DWORD PTR DS:[406058],70597243 004011F9 JNZ SHORT cryptex.0040123C 004011FB CMP DWORD PTR DS:[40605C],39586554

00401205 JNZ SHORT cryptex.0040123C

00401207 PUSH EDI

00401208 MOV ECX,4

0040120D MOV EDI,cryptex.00405038

00401212 MOV ESI,cryptex.00406070

00401217 XOR EDX,EDX

00401219 REPE CMPS DWORD PTR ES:[EDI],DWORD PTR DS:[ESI]

0040121B POP EDI

0040121C JE SHORT cryptex.00401234

0040121E PUSH cryptex.00403170 ; format = "ERROR: Invalid

password. Unable to process

file."

00401223 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>] ; printf

00401229 ADD ESP,4

0040122C PUSH 1 ; status = 1

0040122E CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.exit>] ; exit

00401234 MOV EAX,1

00401239 POP ESI

0040123A POP ECX

0040123B RETN

0040123C PUSH cryptex.0040313C ; format = "ERROR: Invalid

Cryptex9 signature in file

header!"

00401241 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>] ; printf

00401247 ADD ESP,4

0040124A PUSH 1 ; status = 1

0040124C CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.exit>] ; exitIt looks as if the function in Listing 6.3 performs some kind of header verification on the archive. It starts out by moving the file pointer to zero (using the SetFilePointer API), and proceeds to read the first 0x28 bytes from the archive file using the ReadFile API. The header data is read into a data structure that is stored at 00406058. It is quite easy to see that this address is essentially a global variable of some sort (as opposed to a heap or stack address), because it is very close to the code address itself. A quick look at the Executable Modules window shows us that the program's executable, Cryptex.exe was loaded into 00400000. This indicates that 00406058 is somewhere within the Cryptex.exe module, probably in the data section (you could verify this by checking the module's data section RVA using an executable dumping tool, but it is quite obvious).

The function proceeds to compare the first two DWORDs in the header with the hard-coded values 70597243 and 39586554. If the first two DWORDs don't match these constants, the function jumps to 0040123C and displays the message ERROR: Invalid Cryptex9 signature in file header!. A quick check shows that 70597243 is the hexadecimal value for the characters CrYp, and 39586554 for the characters TeX9. Cryptex is simply verifying the header and printing an error message if there is a mismatch.

The following code sequence is the one you're after (because it decides whether the function returns 1 or prints out the bad password message). This sequence compares two 16-byte sequences in memory and prints the error message if there is a mismatch. The first sequence starts at 00405038 and is another global variable whose contents are unknown at this point. The second data sequence starts at 00406070, which is a part of the header global variable you looked at before, that starts at 00406058. This is apparent because earlier ReadFile was reading 0x28 bytes into this address—00406070 is only 0x18 bytes past the beginning, so there are still 0x10 (or 16 in decimal) bytes left in this buffer.

The actual comparison is performed using the REPE CMPS instruction, which repeatedly compares a pair of DWORDs, one pointed at by EDI and the other by ESI, and increments both index registers after each iteration. The number of iterations depends on the value of ECX, and in this case is set to 4, which means that the instruction will compare four DWORDs (16 bytes) and will jump to 00401234 if the buffers are identical. If the buffers are not identical execution will flow into 0040121E, which is where we wound up.

The obvious question at this point is what are those buffers that Cryptex is comparing? Is it the actual passwords? A quick look in OllyDbg reveals the contents of both buffers. The following is the contents of the global variable at 00405038 with whom we are comparing the archive's header buffer:

00405038 1F 79 A0 18 0B 91 0D AC A2 0B 09 7B 8D B4 CF 0E

The buffer that originated in the archive's header contains the following:

00406070 5F 60 43 BC 26 F0 F7 CA 68 16 0D 2B 99 E7 FA 61

The two are obviously different, and are also clearly not the plaintext passwords. It looks like Cryptex is storing some kind of altered version of the password inside the file and is comparing that with what must be an altered version of the currently typed password (which must have been altered with the exact same algorithm in order for this to work). The interesting questions are how are passwords transformed, and is that transformation secure—would it be somehow possible to reconstruct the password using only that altered version? If so, you could extract the password from the archive header.

The easiest way to locate the algorithm that transforms the plaintext password into this 16-byte sequence is to place a memory breakpoint on the global variable that stores the currently typed password. This is the variable at 00405038 against which the header data was compared in Listing 6.3. In OllyDbg, a memory breakpoint can be set by opening the address (00405038) in the Dump window, right-clicking the address, and selecting Breakpoint

Restart the program, place a hardware breakpoint on 00405038, and let the program run (with the same set of command-line parameters). The debugger breaks somewhere inside RSAENH.DLL, the Microsoft Enhanced Cryptographic Provider. Why is the Microsoft Enhanced Cryptographic Provider writing into a global variable from Cryptex.exe? Probably because Cryptex.EXE had supplied the address of that global variable. Let's look at the stack and try to trace back and find the call made from Cryptex to the encryption engine. In tracing back through the stack in the Stack Window, you can see that we are currently running inside the CryptGetHashParam API, which was called from a function inside Cryptex. Listing 6.4 shows the code for this function.

Example 6.4. Function in Cryptex that calls into the cryptographic service provider—the 16-byte password-identifier value is written from within this function.

00402280 MOV ECX,DS:[405048] 00402286 SUB ESP,8 00402289 LEA EAX,SS:[ESP] 0040228C PUSH EAX 0040228D PUSH 0 0040228F PUSH 0 00402291 PUSH 8003 00402296 PUSH ECX 00402297 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptCreateHash>] 0040229D TEST EAX,EAX 0040229F JE SHORT cryptex.004022C2 004022A1 MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+C] 004022A5 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP] 004022A8 PUSH 0 004022AA PUSH 14 004022AC PUSH EDX 004022AD PUSH EAX 004022AE CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptHashData>] 004022B4 TEST EAX,EAX 004022B6 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP] 004022B9 JNZ SHORT cryptex.004022C8 004022BB PUSH ECX 004022BC CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDestroyHash>] 004022C2 XOR EAX,EAX 004022C4 ADD ESP,8 004022C7 RETN

004022C8 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+10] 004022CC PUSH ESI 004022CD PUSH 0 004022CF LEA EDX,SS:[ESP+C] 004022D3 PUSH EDX 004022D4 PUSH EAX 004022D5 PUSH 2 004022D7 PUSH ECX 004022D8 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+1C],10 004022E0 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptGetHashParam>] 004022E6 MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+4] 004022EA PUSH EDX 004022EB MOV ESI,EAX 004022ED CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDestroyHash>] 004022F3 MOV EAX,ESI 004022F5 POP ESI 004022F6 ADD ESP,8 004022F9 RETN

Deciphering the code in Listing 6.4 is not going to be easy unless you do some reading and figure out what all of these hash APIs are about. For this purpose, you can easily go to http://msdn.microsoft.com and lookup the functions CryptCreateHash, CryptHashData, and so on. A hash is defined in MSDN as "A fixed-sized result obtained by applying a mathe-matical function (the hashing algorithm) to an arbitrary amount of data." The CryptCreateHash function "initiates the hashing of a stream of data," the CryptHashData function "adds data to a specified hash object," while the CryptGetHashParam "retrieves data that governs the operations of a hash object." With this (very basic) understanding, let's analyze the function in Listing 6.4 and try to determine what it does.

The code starts out by creating a hash object in the CryptCreateHash call. Notice the second parameter in this call; This is how the hashing algorithm is selected. In this case, the algorithm parameter is hard-coded to 0x8003. Finding out what 0x8003 stands for is probably easiest if you look for a popular hashing algorithm identifier such as CALG_MD2 and find it in the Crypto header file, WinCrypt.H. It turns out that these identifiers are made out of several identifiers, one specifying the algorithm class (ALG_CLASS_HASH), another specifying the algorithm type (ALG_TYPE_ANY), and finally one that specifies the exact algorithm type (ALG_SID_MD2). If you calculate what 0x8003 stands for, you can see that the actual algorithm is ALG_SID_MD5.

MD5 (MD stands for message-digest) is a highly popular cryptographic hashing algorithm that produces a long (128-bit) hash or checksum from a variable-length message. This hash can later be used to uniquely identify the specific message. Two basic properties of MD5 and other cryptographic hashes are that it is extremely unlikely that there would ever be two different messages that produce the same hash and that it is virtually impossible to create a message that will generate a predetermined hash value.

With this information, let's proceed to determine the nature of the data that Cryptex is hashing. This can be easily gathered by inspecting the call to CryptHashData. According to the MSDN, the second parameter passed to CryptHashData is the data being hashed. In Listing 6.4, Cryptex is passing EDX, which was earlier loaded from [ESP+C]. The third parameter is the buffer length, which is set to 0x14 (20 bytes). A quick look at the buffer pointer to by [ESP+C] shows the following.

0012F5E8 77 03 BE 9F EC CA 20 05 D0 D6 DF FB A2 CF 55 4B 0012F5F8 81 41 C0 FE

Nothing obvious here—this isn't text or anything, just more unrecognized data. The next thing Cryptex does is call CryptGetHashParam on the hash object, with the value 2 in the second parameter. A quick search through WinCrypt.H shows that the value 2 stands for HP_HASHVAL. This means that Cryptex is asking for the actual hash value (that's the MD5 result for those 20 bytes from 0012F5E8). The third parameter passed to CryptGetHashParam tells the function where to write the hash value. Guess what? It's being written into 00405038, the global variable that was used earlier for checking whether the password matches.

To summarize, Cryptex is apparently hashing unknown, nontextual data using the MD5 hashing algorithm, and is writing the result into a global variable. The contents of this global variable are later compared against a value stored in the Cryptex archive file. If it isn't identical, Cryptex reports an incorrect password. It is obvious that the data that is being hashed in the function from Listing 6.4 is clearly somehow related to the password that was typed. We just don't understand the connection. The unknown data that was hashed in this function was passed as a parameter from the calling function.

At this point you're probably a bit at a loss regarding the origin of the buffer, you just hashed in Listing 6.4. In such cases, it is usually best to simply trace back in the program until you find the origin of that buffer. In this case, the hashed buffer came from the calling function, at 00402300. This function is shown in Listing 6.5.

Example 6.5. The Cryptex key-generation function.

00402300 SUB ESP,24 00402303 MOV EAX,DS:[405020] 00402308 PUSH EDI 00402309 MOV EDI,SS:[ESP+2C] 0040230D MOV SS:[ESP+24],EAX 00402311 LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+4] 00402315 PUSH EAX 00402316 PUSH 0 00402318 PUSH 0 0040231A PUSH 8004 0040231F PUSH EDI 00402320 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptCreateHash>] 00402326 TEST EAX,EAX 00402328 JE cryptex.004023CA 0040232E MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+30] 00402332 MOV EAX,EDX 00402334 PUSH ESI 00402335 LEA ESI,DS:[EAX+1] 00402338 MOV CL,DS:[EAX] 0040233A ADD EAX,1 0040233D TEST CL,CL 0040233F JNZ SHORT cryptex.00402338 00402341 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+8] 00402345 PUSH 0 00402347 SUB EAX,ESI 00402349 PUSH EAX 0040234A PUSH EDX 0040234B PUSH ECX 0040234C CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptHashData>] 00402352 TEST EAX,EAX 00402354 POP ESI 00402355 JE SHORT cryptex.004023BF 00402357 XOR EAX,EAX 00402359 MOV SS:[ESP+11],EAX 0040235D MOV SS:[ESP+15],EAX 00402361 MOV SS:[ESP+19],EAX 00402365 MOV SS:[ESP+1D],EAX 00402369 MOV SS:[ESP+21],AX 0040236E LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+C] 00402372 LEA EDX,SS:[ESP+10] 00402376 MOV SS:[ESP+23],AL 0040237A MOV BYTE PTR SS:[ESP+10],0 0040237F MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+C],14 00402387 PUSH EAX 00402388 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+8] 0040238C PUSH ECX 0040238D PUSH EDX 0040238E PUSH 2

00402390 PUSH EAX

00402391 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptGetHashParam>]

00402397 TEST EAX,EAX

00402399 JNZ SHORT cryptex.004023A9

0040239B PUSH cryptex.00403504 ; format = "Unable to obtain MD5

hash value for file."

004023A0 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>]

004023A6 ADD ESP,4

004023A9 LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+10]

004023AD PUSH cryptex.00405038

004023B2 PUSH ECX

004023B3 CALL cryptex.00402280

004023B8 ADD ESP,8

004023BB TEST EAX,EAX

004023BD JNZ SHORT cryptex.004023DA

004023BF MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+4]

004023C3 PUSH EDX

004023C4 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDestroyHash>]

004023CA XOR EAX,EAX

004023CC POP EDI

004023CD MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+20]

004023D1 CALL cryptex.004027C9

004023D6 ADD ESP,24

004023D9 RETN

004023DA MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+4]

004023DE LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+8]

004023E2 PUSH EAX

004023E3 PUSH 0

004023E5 PUSH ECX

004023E6 PUSH 6603

004023EB PUSH EDI

004023EC MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+1C],0

004023F4 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDeriveKey>]

004023FA MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+4]

004023FE PUSH EDX

004023FF CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDestroyHash>]

00402405 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+24]

00402409 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+8]

0040240D POP EDI

0040240E CALL cryptex.004027C9

00402413 ADD ESP,24

00402416 RETNThe function in Listing 6.5 is quite similar to the one in Listing 6.4. It starts out by creating a hash object and hashing some data. One difference is the initialization parameters for the hash object. The function in Listing 6.4 used the value 0x8003 as its algorithm ID, while this function uses 0x8004, which identifies the CALG_SHA algorithm. SHA is another hashing algorithm that has similar properties to MD5, with the difference that an SHA hash is 160 bits long, as opposed to MD5 hashes which are 128 bits long. You might notice that 160 bits are exactly 20 bytes, which is the length of data being hashed in Listing 6.4. Coincidence? You'll soon find out. . . .

The next sequence calls CryptHashData again, but not before some processing is performed on some data block. If you place a breakpoint on this function and restart the program, you can easily see which data it is that is being processed: It is the password text, which in this case equals 6666666665. Let's take a look at this processing sequence.

00402335 LEA ESI,DS:[EAX+1] 00402338 MOV CL,DS:[EAX] 0040233A ADD EAX,1 0040233D TEST CL,CL 0040233F JNZ SHORT cryptex.00402338

This loop is really quite simple. It reads each character from the string and checks whether its zero. If it's not it loops on to the next character. When the loop is completed, EAX points to the string's terminating NULL character, and ESI points to the second character in the string. The following instruction produces the final result.

00402347 SUB EAX,ESI

Here the pointer to the second character is subtracted from the pointer to the NULL terminator. The result is effectively the length of the string, not including the NULL terminator (because ESI was holding the address to the second character, not the first). This sequence is essentially equivalent to the strlen C runtime library function. You might wonder why the program would implement its own strlen function instead of just calling the runtime library. The answer is that it probably is calling the runtime library, but the compiler is replacing the call with an intrinsic implementation. Some compilers support intrinsic implementations of popular functions, which basically means that the compiler replaces the function call with an actual implementation of the function that is placed inside the calling function. This improves performance because it avoids the overhead of performing a function call.

After measuring the length of the string, the function proceeds to hash the password string using CryptHashData and to extract the resulting hash using CryptGetHashParam. The resulting hash value is then passed on to 00402280, which is the function we investigated in Listing 6.4. This is curious because as we know the function in Listing 6.4 is going to hash that data again, this time using the MD5 algorithm. What is the point of rehashing the output of one hashing algorithm with another hashing algorithm? That is not clear at the moment.

After the MD5 function returns (and assuming it returns a nonzero value), the function proceeds to call an interesting API called CryptDeriveKey. According to Microsoft's documentation, CryptDeriveKey "generates cryptographic session keys derived from a base data value." The base data value is taken for a hash object, which, in this case, is a 160-bit SHA hash calculated from the plaintext password. As a part of the generation of the key object, the caller must also specify which encryption algorithm will be used (this is specified in the second parameter passed to CryptDeriveKey). As you can see in Listing 6.5, Cryptex is passing 0x6603. We return to WinCrypt.H and discover that 0x6603 stands for CALG_3DES. This makes sense and proves that Cryptex works as advertised: It encrypts data using the 3DES algorithm.

When we think about it a little bit, it becomes clear why Cryptex calculated that extra MD5 hash. Essentially, Cryptex is using the generated SHA hash as a key for encrypting and decrypting the data (3DES is a symmetric algorithm, which means that encryption and decryption are both performed using the same key). Additionally, Cryptex needs some kind of an easy way to detect whether the supplied password was correct or incorrect. For this, Cryptex calculates an additional hash (using the MD5 algorithm) from the SHA hash and stores the result in the file header. When an archive is opened, the supplied password is hashed twice (once using SHA and once using MD5), and the MD5 result is compared against the one stored in the archive header. If they match, the password is correct.

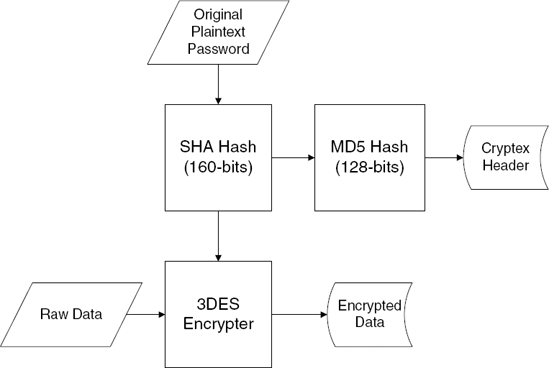

You may wonder why Cryptex isn't just storing the SHA result directly into the file header. Why go through the extra effort of calculating an additional hash value? The reason is that the SHA hash is directly used as the encryption key; storing it in the file header would make it incredibly easy to decrypt Cryptex archives. This might be a bit confusing considering that it is impossible to extract the original plaintext password from the SHA hash value, but it is just not needed. The hash value is all that would be needed in order to decrypt the data. Instead, Cryptex calculates an additional hash from the SHA value and stores that as the unique password identification. Figure 6.1 demonstrates this sequence.

Finally, if you're wondering why Cryptex isn't calculating the MD5 password-verification hash directly from the plaintext password but from the SHA hash value, it's probably because of the (admittedly remote) possibility that someone would be able to convert the MD5 hash value to an equivalent SHA hash value and effectively obtain the decryption key. This is virtually guaranteed to be mathematically impossible, but why risk it? It is certainly going to be impossible to obtain the original data (which is the SHA-generated decryption key) from the MD5 hash value stored in the header. Being overly paranoid is the advisable frame of mind when developing security-related technologies.

Now that you have a basic understanding of how Cryptex manages its passwords and encryption keys, you can move on to study the Cryptex directory layout. In a real-world program, this step would be somewhat less relevant for those interested in a security-level analysis for Cryptex, but it would be very important for anyone interested in reading or creating Cryptex-compatible archives. Since we're doing this as an exercise in data reverse engineering, the directory layout is exactly the kind of complex data structure you're looking to get your hands on.

In order to decipher the directory layout you'll need to find the location in the Cryptex code that reads the encrypted directory layout data, decrypts it, and proceeds to decipher it. This can be accomplished by simply placing a breakpoint on the ReadFile API and tracing forward in the program to see what it does with the data. Let's restart the program in OllyDbg (don't forget to correct the password in the command-line argument), place a breakpoint on ReadFile, and let the program run.

The first hit comes from an internal system call made by ADVAPI32.DLL. Releasing the debugger brings it back to ReadFile again, except that again, it was called internally from system code. You will very quickly realize that there are way too many calls to ReadFile for this approach to work; this API is used by the system heavily.

There are many alternative approaches you could take at this point, depending on the particular application. One option would be to try and restrict the ReadFile breakpoint to calls made on the archive file. You could do this by first placing a breakpoint on the API call that opens or creates the archive (this is probably going to be a call to the CreateFile API), obtain the archive handle from that call, and place a selective breakpoint on ReadFile that only breaks when the specific handle to the Cryptex archive is specified (such breakpoints are supported by most debuggers). This would really reduce the number of calls—you'd only see the relevant calls where Cryptex reads from the archive, and not hundreds of irrelevant system calls.

On the other hand, since Cryptex is really a fairly simple program, you could just let it run until it reached the key-generation function from Listing 6.5. At this point you could just step through the rest of the code until you reach interesting code areas that decipher the directory data structures. Keep in mind that in most real programs you'd have to come up with a better idea for where to place your breakpoint, because simply stepping through the program is going to be an unreasonably tedious task.

You can start by placing a breakpoint at the end of the key-generation function, on address 00402416. Once you reach that address, you can step back into the calling function and step through several irrelevant code sequences, including a call into a function that apparently performs the actual opening of the archive and ends up calling into 004011C0, which is the function analyzed in Listing 6.3. The next function call goes into 004019F0, and (based on a quick look at it) appears to be what we're looking for. Listing 6.6 lists the OllyDbg-generated disassembly for this function.

Example 6.6. Disassembly of function that lists all files within a Cryptex archive.

004019F0 SUB ESP,8 004019F3 PUSH EBX 004019F4 PUSH EBP 004019F5 PUSH ESI 004019F6 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+18] 004019FA XOR EBX,EBX 004019FC PUSH EBX ; Origin => FILE_BEGIN 004019FD PUSH EBX ; pOffsetHi => NULL 004019FE PUSH EBX ; OffsetLo => 0 004019FF PUSH ESI ; hFile 00401A00 CALL DS:[<&KEKNEL32.SetFilePointer>] 00401A06 PUSH EBX ; pOverlapped => NULL

00401A07 LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+14] ; 00401A0B PUSH EAX ; pBytesRead 00401A0C PUSH 28 ; BytesToRead = 28 (40.) 00401A0E PUSH cryptex.00406058 ; Buffer = cryptex.00406058 00401A13 PUSH ESI ; hFile 00401A14 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.ReadFile> 00401A1A MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+1C] 00401A1E MOV EDX,DS:[406064] 00401A24 PUSH ECX 00401A25 PUSH EDX 00401A26 PUSH ESI 00401A27 CALL cryptex.00401030 00401A2C MOV EBP,DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf> 00401A32 MOV ESI,DS:[406064] 00401A38 PUSH cryptex.00403234 ; format = " File Size File Name" 00401A3D MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+1C],cryptex.00405050 00401A45 CALL EBP ; printf 00401A47 ADD ESP,10 00401A4A TEST ESI,ESI 00401A4C JE SHORT cryptex.00401ACD 00401A4E PUSH EDI 00401A4F MOV EDI,SS:[ESP+24] 00401A53 JMP SHORT cryptex.00401A60 00401A55 LEA ESP,SS:[ESP] 00401A5C LEA ESP,SS:[ESP] 00401A60 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+10] 00401A64 ADD ESI,8 00401A67 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+14],1A 00401A6F NOP 00401A70 MOV EAX,DS:[ESI] 00401A72 TEST EAX,EAX 00401A74 JE SHORT cryptex.00401A9A 00401A76 MOV EDX,EAX 00401A78 SHL EDX,0A 00401A7B SUB EDX,EAX 00401A7D ADD EDX,EDX 00401A7F LEA ECX,DS:[ESI+14] 00401A82 ADD EDX,EDX 00401A84 PUSH ECX 00401A85 SHR EDX,0A 00401A88 PUSH EDX 00401A89 PUSH cryptex.00403250 ; ASCII " %10dK %s" 00401A8E CALL EBP 00401A90 MOV EAX,DS:[ESI] 00401A92 ADD DS:[EDI],EAX 00401A94 ADD ESP,0C 00401A97 ADD EBX,1

00401A9A ADD ESI,98 00401AA0 SUB DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+14],1 00401AA5 JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401A70 00401AA7 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+10] 00401AAB MOV ESI,DS:[ECX] 00401AAD TEST ESI,ESI 00401AAF JE SHORT cryptex.00401ACC 00401AB1 MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+20] 00401AB5 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+1C] 00401AB9 PUSH EDX 00401ABA PUSH ESI 00401ABB PUSH EAX 00401ABC CALL cryptex.00401030 00401AC1 ADD ESP,0C 00401AC4 TEST ESI,ESI 00401AC6 MOV SS:[ESP+10],EAX 00401ACA JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401A60 00401ACC POP EDI 00401ACD POP ESI 00401ACE POP EBP 00401ACF MOV EAX,EBX 00401AD1 POP EBX 00401AD2 ADD ESP,8 00401AD5 RETN

This function starts out with a familiar sequence that reads the Cryptex header into memory. This is obvious because it is reading 0x28 bytes from offset 0 in the file. It then proceeds to call into a function at 00401030, which, upon stepping into it, looks quite important. Listing 6.7 provides a disassembly of the function at 00401030.

Example 6.7. A disassembly of Cryptex's cluster decryption function.

00401030 PUSH ECX 00401031 PUSH ESI 00401032 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+C] 00401036 PUSH EDI 00401037 MOV EDI,SS:[ESP+14] 0040103B MOV ECX,1008 00401040 LEA EAX,DS:[EDI-1] 00401043 MUL ECX 00401045 ADD EAX,28 00401048 ADC EDX,0 0040104B PUSH 0 ; Origin = FILE_BEGIN 0040104D MOV SS:[ESP+18],EDX ;

00401051 LEA EDX,SS:[ESP+18] ; 00401055 PUSH EDX ; pOffsetHi 00401056 PUSH EAX ; OffsetLo 00401057 PUSH ESI ; hFile 00401058 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.SetFilePointer>] 0040105E PUSH 0 ; pOverlapped = NULL 00401060 LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+C] ; 00401064 PUSH EAX ; pBytesRead 00401065 PUSH 1008 ; BytesToRead = 1008 (4104.) 0040106A PUSH cryptex.00405050 ; Buffer = cryptex.00405050 0040106F PUSH ESI ; hFile 00401070 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.ReadFile> 00401076 TEST EAX,EAX 00401078 JE SHORT cryptex.004010CB 0040107A MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+18] 0040107E TEST EAX,EAX 00401080 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+14],1008 00401088 JE SHORT cryptex.004010C2 0040108A LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+14] 0040108E PUSH ECX 0040108F PUSH cryptex.00405050 00401094 PUSH 0 00401096 PUSH 1 00401098 PUSH 0 0040109A PUSH EAX 0040109B CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDecrypt>] 004010A1 TEST EAX,EAX 004010A3 JNZ SHORT cryptex.004010C2 004010A5 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.GetLastError>] 004010AB PUSH EDI ; <%d> 004010AC PUSH cryptex.004030E8 ; format = "ERROR: Unable to decrypt block from cluster &%d." 004010B1 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>] 004010B7 ADD ESP,8 004010BA PUSH 1 ; status = 1 004010BC CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.exit>] 004010C2 POP EDI 004010C3 MOV EAX,cryptex.00405050 004010C8 POP ESI 004010C9 POP ECX 004010CA RETN 004010CB POP EDI 004010CC XOR EAX,EAX 004010CE POP ESI 004010CF POP ECX 004010D0 RETN

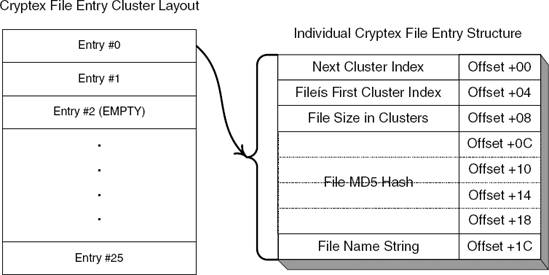

This function starts out by reading a fixed size (4,104-byte) chunk of data from the archive file. The interesting thing about this read operation is how the starting address is calculated. The function receives a parameter that is multiplied by 4,104, adds 0x28, and is then used as the file offset from where to start reading. This exposes an important detail about the internal organization of Cryptex files: they appear to be divided into data blocks that are 4,104 bytes long. Adding 0x28 to the file offset is simply a way to skip the file header. The second parameter that this function takes appears to be some kind of a block number that the function must read.

After the data is read into memory, the function proceeds to decrypt it using the CryptDecrypt function. As expected, the data-length parameter (which is the sixth parameter passed to this function) is again hard-coded to 4104. It is interesting to look at the error message that is printed if this function fails. It reveals that this function is attempting to read and decrypt a cluster, which is probably just a fancy name for what I classified as those fixed-sized data blocks. If CryptDecrypt is successful, the function simply returns to the caller while returning the address of the newly decrypted block.

Since you're working under the assumption that the block that was just read is the archive's file directory or some other part of its header, your next step is to take the decrypted block and attempt to study it and establish how it's structured. The following memory dump shows the contents of the decrypted block I obtained while trying to list the files in the Testi.crx archive created earlier.

00405050 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 00405058 01 00 00 00 52 EB DD 0C ...Rë_. 00405060 D4 CB 55 D9 A4 CD El C6 ÔËUÙÍáÆ 00405068 96 6C 9C 3C 61 73 74 65 -l<aste 00405070 72 69 73 6B 73 2E 74 78 risks.tx 00405078 74 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 t.......

As you can see, you're in the right place; the memory block contains the file name asterisks.txt, which you encrypted into this archive earlier. The question now is: What is in those 28 bytes that precede the file name? One thing to do right away is to try and view the data in a different way. In the preceding dump I used an ASCII view because I wanted to be able to see the file name string, but it might be easier to make out other fields by using a 32-bit view on this entry. The following are the first 28 bytes viewed as a sequence of 32-bit hexadecimal numbers:

00405050 00000000 00000002 00000001 0CDDEB52 00405060 D955CBD4 C6E1CDA4 3C9C6C96

With this view, you can immediately see a somewhat improved picture. The first three DWORDs are obviously some kind of 32-bit fields. The last four DWORDs are not as obvious, and seem to be some kind of a random 16-byte sequence. This is easy to tell because they do not contain text (you would have seen that in the previous dump), and they are not pointers or offsets into the file (the numbers are far too large, and some of them are not 32-bit aligned). This is a classic case where stepping into the code that deciphers this data should really simplify the process of deciphering the file format.

The code that actually reads the file table and displays the file list is shown in Listing 6.6 and is actually quite simple to analyze because the fields that it reads are both printed into the screen, so it's very easy to tell what they stand for. Let's go back to that code sequence and see what it's doing with this file entry.

00401A60 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+10] 00401A64 ADD ESI,8 00401A67 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+14],1A 00401A6F NOP 00401A70 MOV EAX,DS:[ESI] 00401A72 TEST EAX,EAX 00401A74 JE SHORT cryptex.00401A9A 00401A76 MOV EDX,EAX 00401A78 SHL EDX,OA 00401A7B SUB EDX,EAX 00401A7D ADD EDX,EDX 00401A7F LEA ECX,DS:[ESI+14] 00401A82 ADD EDX,EDX 00401A84 PUSH ECX 00401A85 SHR EDX,OA

This sequence starts out by loading ESI with the newly decrypted block's starting address, adding 8 to that, and reading a 32-bit member at that address into EAX. If you go back to the previous memory dump, you'll see that the third DWORD contains 00000001. At this point, the code confirms that EAX is nonzero, and proceeds to perform an interesting series of arithmetic operations on it.

First, EDX is shifted left by OxA (10) bits, then the original value (from EAX) is subtracted from the result. At that point, the value of EDX is added to itself (which is the equivalent of multiplying it by two). This operation is performed again in 00401A82, and is followed by a right-shift of OxA (10) bits. Now let's go over these operations step by step and try to determine their purpose.

EDXis shifted left by 10, which is equivalent to edx = edx × 1,024.The original number at

EAXis subtracted fromEDX. This means that instead of 1,024, you have essentially performed edx = edx × 1,024 - edx, which is the equivalent of edx = edx × 1,023.edxis then added to itself, twice. This is equivalent of edx = edx × 4, which means that so far you've essentially calculated edx = edx × 4,092.Finally,

EDXis shifted back right by 10 bits, which is the equivalent of dividing by 1,024. The final formula is edx = edx × 4092 ÷ 1024.

You might be wondering why Cryptex didn't just use the MUL instruction to multiply EDX by 4,092 and then apply the DIV instruction to divide the result by 1,024. The answer is that such code would run far more slowly than the one we've just analyzed. MUL and DIV are both relatively slow instructions, whereas ADD, SUB, and the shifting instructions are much faster. It is important to note that this sequence reveals an interesting fact about Cryptex: It was most likely compiled using some kind of an optimize-for-fast-code switch, rather than with an optimize-for-small-code switch. That's because using the direct arithmetic instructions for division and multiplication would have produced smaller, yet slower, code. The compiler was clearly aiming at the generation of high-performance code, even at the cost of a somewhat larger executable.

The result of this little arithmetic sequence goes right into the printf call that prints the current file entry. This is quite illuminating because it tells you exactly what Cryptex was trying to calculate in the preceding arithmetic sequence: the file size. In fact, it is quite obvious that because the file size is printed in kilobytes, the final division by 1,024 simply converts the file size from bytes to kilobytes. The question now is, what was that original number and why was Cryptex multiplying it by 4,092? Well, it would seem that the file size is maintained by using some kind of fixed block size, which is probably somehow related to the cluster you saw earlier while decrypting the buffer. The problem is that the cluster you were dealing with earlier was 4,104 bytes long, and here you're dealing with clusters that are only 4,092 bytes long. The difference is not clear at this point.

The original number of clusters that you multiplied was taken from offset +8 in the current file entry structure, so you know that offset +8 contains the file size in clusters. This raises the question of where does Cryptex store the actual file size? It would not be possible to accurately recover encrypted files without creating them with the exact size they had originally. Therefore Cryptex must also maintain the accurate file size somewhere in the archive file.

Other than the file size, the printf call also takes the file name, which is easily obtained by taking the address of offset +14 from ESI. Keep in mind that ESI was incremented by 8 earlier, so this is actually offset +1C from the original data structure, which matches what you saw in our data dump, where the string started at offset +1C.

After printing the file name and size, the program loops back to print the next entry. To reach the next item, Cryptex increments ESI by 0x98 bytes (152 in decimal), which is clearly the length of each entry. This indicates that there is a fixed number of characters reserved for each file name. Since you know that the string starts at offset +14 in the structure, you can assume that there aren't any additional data entries after it in the structure, which would mean that the maximum length of a file name in Cryptex is 152 – 20, or 132 bytes.

Once this loop ends, an interesting thing takes place. The first member in the buffer you read and decrypted earlier is tested, and if it is nonzero, Cryptex calls the function at 00401030, the function from Listing 6.7 that reads and decrypts a data chunk that we analyzed earlier. The second parameter, which is used as a kind of cluster number (remember how the function multiplies that number by 4104?), is taken directly from that first member. Clearly the idea here is to read and decrypt another chunk of data and scan it for files. It looks likes the file list can span an arbitrary number clusters and is essentially implemented using a sort of cluster linked list. This brings up one question: Is the first cluster hard-coded to number one? Let's take a look at the code that made the initial call to read the first file-list cluster, from Listing 6.6.

00401A1E MOV EDX,DS:[406064] 00401A24 PUSH ECX 00401A25 PUSH EDX 00401A26 PUSH ESI 00401A27 CALL cryptex.00401030

The first-cluster index is taken from a global variable with a familiar address. It turns out that 00406064 is a part of the Cryptex header loaded into 00406058 just a few lines earlier. So, it looks like offset +0C in the Cryptex header contains the index of the first cluster in the file table.

Going back to Listing 6.7, after 00401030 returns, ESI is tested for a nonzero value again (even though it has already been tested and its value couldn't have been changed), and if it is nonzero Cryptex loops back into the code that reads the file table. You now know that the first member in these file table clusters is the next cluster element that tells Cryptex which cluster contains the following file table entries, if any. Because the size of each file entry is fixed, there must also be a fixed number of entries in each cluster. Since a local variable at [ESP+14] is used for counting the remaining number of items in the current cluster, you easily find the instruction at 00401A67, which initializes this variable to OxlA (26 in decimal), so you know that each cluster can contain up to 26 file entries.

Finally, it is important to pay attention to three lines in Listing 6.6 that we've so far ignored.

00401A70 MOV EAX,DS:[ESI] 00401A72 TEST EAX,EAX 00401A74 JE SHORT cryptex.00401A9A

It appears that a file entry must have a nonzero value in its offset +8 in order for Cryptex to actually pay attention to the entry. As we've recently established, offset +8 contains the file size in clusters, so Cryptex is essentially checking for a nonzero file size. The fact that Cryptex supports skipping file entries indicates that it allows for holesin its file list, so when a file is deleted Cryptex simply marks its entry as deleted and doesn't have to start copying any entries. When deleted entries are encountered they are simply ignored, as you can see here.

This is exactly the type of thing you probably wouldn't see in a robust commercial security product. By not erasing these data blocks, Cryptex creates a slight security risk. Sure, the "deleted" clusters are probably still encrypted (they couldn't be in plain text because Cryptex isn't ever supposed to insert plaintext data into the archives!), but they might contain sensitive information. Suppose that you used Cryptex to send files to someone who had the password to your archive. Because deleted files might still be in the archive, you might actually be sending that person additional files you thought you had deleted!

So, what would you have to do in order to actually dump the file list in a Cryptex archive? It's actually not that complicated. The following steps must be taken in order to correctly dump the list of files inside a Cryptex archive:

Initialize the Crypto API and open the archive file.

Verify the 8-byte header signature.

Calculate an SHA hash out of the typed password, and calculate an MD5 hash out of that.

Verify that the calculated MD5 hash matches the stored MD5 hash from the Cryptex header (at offset +18).

Produce a 3DES key using the SHA hash object.

Read the first file list cluster (whose index is stored in offset +0C in the Cryptex header) in the same manner as it is read in Cryptex (reading 4,104 bytes and decrypting them using our 3DES key).

Loop through those 152-bytes long entries and dump each entry's name if its offset +8 (which is the file size in clusters) is nonzero.

Proceed to read and decrypt additional file-list clusters if they are present. List any entries within those clusters.

The actual code that implements the preceding sequence is relatively straightforward to implement. If you'd like to see what it looks like, it is available on this book's Web site at www.wiley.com/go/eeilam.

Cryptex would not be worth much without having the ability to decrypt and extract files from its encrypted archive files. This is done using the x command, which simply creates a file with the same name as the original that was encoded (minus the file's path) and decrypts the original data into it. Reversing the extraction process should provide you with a clearer view of the file list data layout and on how files are actually stored within archive files. The rather longish Listing 6.8 contains the Cryptex file extraction routine.

Example 6.8. A disassembly of Cryptex's file decryption and extraction routine.

00401BB0 SUB ESP,70 00401BB3 MOV EAX,DS:[405020] 00401BB8 PUSH EBX 00401BB9 PUSH EDI 00401BBA MOV EDI,SS:[ESP+84] 00401BC1 PUSH 0 00401BC3 MOV SS:[ESP+78],EAX 00401BC7 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+80] 00401BCE PUSH 0 00401BD0 PUSH EAX 00401BD1 PUSH EDI 00401BD2 CALL cryptex.00401670 00401BD7 MOV EDX,DS:[405048] 00401BDD ADD ESP,10 00401BE0 LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+14] 00401BE4 PUSH ECX 00401BE5 PUSH 0 00401BE7 PUSH 0 00401BE9 PUSH 8003 00401BEE PUSH EDX 00401BEF MOV EBX,EAX 00401BF1 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptCreateHash>] 00401BF7 TEST EAX,EAX 00401BF9 JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401C11 00401BFB PUSH cryptex.00403284 ; /format = "Unable to verify the file's hash value!" 00401C00 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>] 00401C06 ADD ESP,4 00401C09 PUSH 1 ; /status = 1 00401C0B CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.exit>] 00401C11 PUSH EBP 00401C12 PUSH ESI 00401C13 PUSH 0 ; /Origin = FILE_BEGIN 00401C15 PUSH 0 ; |pOffsetHi = NULL 00401C17 PUSH 0 ; |OffsetLo = 0 00401C19 PUSH EBX ; |hFile 00401C1A CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.SetFilePoimter>]

00401C20 PUSH 0 ; /pOverlapped = NULL

00401C22 LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+24] ; |

00401C26 PUSH EAX ; |pBytesRead

00401C27 PUSH 28 ; |BytesToRead = 28 (40.)

00401C29 PUSH cryptex.00406058 ; |Buffer = cryptex.00406058

00401C2E PUSH EBX ; |hFile

00401C2F CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.ReadFile>

00401C35 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+88]

00401C3C XOR ECX,ECX

00401C3E PUSH EDI

00401C3F MOV SS:[ESP+71],ECX

00401C43 LEA EDX,SS:[ESP+70]

00401C47 PUSH EDX

00401C48 MOV SS:[ESP+79],ECX

00401C4C LEA EAX,SS:[ESP+18]

00401C50 PUSH EAX

00401C51 MOV SS:[ESP+81],ECX

00401C58 MOV SS:[ESP+85],CX

00401C60 PUSH ESI

00401C61 PUSH EBX

00401C62 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+24],0

00401C6A MOV SS:[ESP+28],ESI

00401C6E MOV BYTE PTR SS:[ESP+80],0

00401C76 MOV SS:[ESP+8F],CL

00401C7D CALL cryptex.004017B0

00401C82 MOV EDI,SS:[ESP+24]

00401C86 PUSH 5C ; /c = 5C ('\')

00401C88 PUSH ESI ; |s

00401C89 MOV SS:[ESP+34],ESI ; |

00401C8D MOV ESI,DS:[<&MSVCR71.strchr>]

00401C93 MOV EBP,EAX ; |

00401C95 CALL ESI ; \strchr

00401C97 ADD ESP,1C

00401C9A TEST EAX,EAX

00401C9C JE SHORT cryptex.00401CB3

00401C9E MOV EDI,EDI

00401CA0 ADD EAX,1

00401CA3 PUSH 5C

00401CA5 PUSH EAX

00401CA6 MOV SS:[ESP+20],EAX

00401CAA CALL ESI

00401CAC ADD ESP,8

00401CAF TEST EAX,EAX

00401CB1 JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401CA0

00401CB3 TEST EBP,EBP

00401CB5 JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401CD2

00401CB7 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+18]

00401CBB PUSH ECX ; /<%s>00401CBC PUSH cryptex.004032B0

; |format = "File "%s" not found in archive."

00401CC1 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>]

00401CC7 ADD ESP,8

00401CCA PUSH 1 ; /status = 1

00401CCC CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.exit>]

00401CD2 MOV ESI,SS:[ESP+14]

00401CD6 PUSH 0 ; /hTemplateFile = NULL

00401CD8 PUSH 0 ; |Attributes = 0

00401CDA PUSH 2 ; |Mode = CREATE_ALWAYS

00401CDC PUSH 0 ; |pSecurity = NULL

00401CDE PUSH 0 ; |ShareMode = 0

00401CE0 PUSH COOOOOOO ; |Access = GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE

00401CE5 PUSH ESI ; |FileName

00401CE6 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.CreateFileA>]

00401CEC CMP EAX,-1

00401CEF MOV SS:[ESP+14],EAX

00401CF3 JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401D13

00401CF5 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.GetLastError>]

00401CFB PUSH EAX ; /<%d>

00401CFC PUSH ESI ; |<%s>

00401CFD PUSH cryptex.004032D4 ; |format = "ERROR: Unable to create file "%s" (Last Error=%d)."

00401D02 CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>]

00401D08 ADD ESP,OC

00401D0B PUSH 1 ; /status = 1

00401D0D CALL DS:[<&MSVCR71.exit>]

00401D13 MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+8C]

00401D1A PUSH EDX

00401D1B PUSH EBP

00401D1C PUSH EBX

00401D1D CALL cryptex.00401030

00401D22 TEST EDI,EDI

00401D24 MOV SS:[ESP+2C],EDI

00401D28 FILD DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+2C]

00401D2C JGE SHORT cryptex.00401D34

00401D2E FADD DWORD PTR DS:[403BA0]

00401D34 FDIVR QWORD PTR DS:[403B98]

00401D3A MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+24]

00401D3E XORPS XMM0,XMM0

00401D41 MOV EBP,DS:[<&MSVCR71.printf>

00401D47 PUSH EAX

00401D48 PUSH cryptex.00403308 ; ASCII "Extracting "%.35s" - "

00401D4D MOVSS SS:[ESP+24],XMM0

00401D53 FSTP DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+34]

00401D57 CALL EBP00401D59 ADD ESP,14 00401D5C TEST EDI,EDI 00401D5E JE cryptex.00401E39 00401D64 MOV ESI,DS:[<&KERNEL32.GetConsoleScreenBufferInfo>] 00401D6A LEA EBX,DS:[EBX] 00401D70 MOV EDX,DS:[40504C] 00401D76 LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+2C] 00401D7A PUSH ECX 00401D7B PUSH EDX 00401D7C CALL ESI 00401D7E FLD DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+10] 00401D82 SUB ESP,8 00401D85 FSTP QWORD PTR SS:[ESP] 00401D88 PUSH cryptex.00403320 ; ASCII "%2.2f percent completed." 00401D8D CALL EBP 00401D8F ADD ESP,0C 00401D92 CMP EDI,1 00401D95 MOV EAX,0FFC 00401D9A JA SHORT cryptex.00401DA1 00401D9C MOV EAX,DS:[405050] 00401DA1 PUSH 0 00401DA3 PUSH EAX 00401DA4 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+24] 00401DA8 PUSH cryptex.00405054 00401DAD PUSH EAX 00401DAE CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptHashData>] 00401DB4 TEST EAX,EAX 00401DB6 JE cryptex.00401EEE 00401DBC CMP EDI,1 00401DBF MOV EAX,0FFC 00401DC4 JA SHORT cryptex.00401DCB 00401DC6 MOV EAX,DS:[405050] 00401DCB MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+14] 00401DCF PUSH 0 ; /pOverlapped = NULL 00401DD1 LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+2C] ; | 00401DD5 PUSH ECX ; |pBytesWritten 00401DD6 PUSH EAX ; |nBytesToWrite 00401DD7 PUSH cryptex.00405054 ; |Buffer = cryptex.00405054 00401DDC PUSH EDX ; |hFile 00401DDD CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.WriteFile>] 00401DE3 SUB EDI,1 00401DE6 JE SHORT cryptex.00401E00 00401DE8 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+8C] 00401DEF MOV ECX,DS:[405050] 00401DF5 PUSH EAX 00401DF6 PUSH ECX 00401DF7 PUSH EBX

00401DF8 CALL cryptex.00401030 00401DFD ADD ESP,OC 00401E00 MOV EAX,DS:[40504C] 00401E05 LEA EDX,SS:[ESP+44] 00401E09 PUSH EDX 00401E0A PUSH EAX 00401E0B CALL ESI 00401E0D MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+30] 00401E11 MOV EDX,DS:[40504C] 00401E17 PUSH ECX ; /CursorPos 00401E18 PUSH EDX ; |hConsole => 00000007 00401E19 CALL DS:[<&KERNEL32.SetConsoleCursorPosition>] 00401E1F TEST EDI,EDI 00401E21 MOVSS XMM0,SS:[ESP+10] 00401E27 ADDSS XMM0,SS:[ESP+20] 00401E2D MOVSS SS:[ESP+10],XMM0 00401E33 JNZ cryptex.00401D70 00401E39 FLD QWORD PTR DS:[403B98] 00401E3F SUB ESP,8 00401E42 FSTP QWORD PTR SS:[ESP] 00401E45 PUSH cryptex.00403368 ; ASCII "%2.2f percent completed." 00401E4A CALL EBP 00401E4C PUSH cryptex.00403384 00401E51 CALL EBP 00401E53 XOR EAX,EAX 00401E55 MOV SS:[ESP+6D],EAX 00401E59 MOV SS:[ESP+71],EAX 00401E5D MOV SS:[ESP+75],EAX 00401E61 MOV SS:[ESP+79],AX 00401E66 ADD ESP,10 00401E69 LEA ECX,SS:[ESP+24] 00401E6D LEA EDX,SS:[ESP+5C] 00401E71 MOV SS:[ESP+6B],AL 00401E75 MOV BYTE PTR SS:[ESP+5C],0 00401E7A MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+24],10 00401E82 PUSH EAX 00401E83 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+20] 00401E87 PUSH ECX 00401E88 PUSH EDX 00401E89 PUSH 2 00401E8B PUSH EAX 00401E8C CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptGetHashParam>] 00401E92 TEST EAX,EAX 00401E94 JNZ SHORT cryptex.00401EA0 00401E96 PUSH cryptex.00403388 ; ASCII "Unable to obtain MD5 hash value for file."

00401E9B CALL EBP 00401E9D ADD ESP,4 00401EA0 MOV ECX,4 00401EA5 LEA EDI,SS:[ESP+6C] 00401EA9 LEA ESI,SS:[ESP+5C] 00401EAD XOR EDX,EDX 00401EAF REPE CMPS DWORD PTR ES:[EDI],DWORD PTR DS:[ESI] 00401EB1 JE SHORT cryptex.00401EC2 00401EB3 MOV EAX,SS:[ESP+18] 00401EB7 PUSH EAX 00401EB8 PUSH cryptex.004033B4 ; ASCII "ERROR: File "%s" is corrupted!" 00401EBD CALL EBP 00401EBF ADD ESP,8 00401EC2 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+1C] 00401EC6 PUSH ECX 00401EC7 CALL DS:[<&ADVAPI32.CryptDestroyHash>] 00401ECD MOV EDX,SS:[ESP+14] 00401ED1 MOV ESI,DS:[<&KERNEL32.CloseHandle>] 00401ED7 PUSH EDX ; /hObject 00401ED8 CALL ESI ; \CloseHandle 00401EDA PUSH EBX ; /hObject 00401EDB CALL ESI ; \CloseHandle 00401EDD MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+7C] 00401EE1 POP ESI 00401EE2 POP EBP 00401EE3 POP EDI 00401EE4 POP EBX 00401EE5 CALL cryptex.004027C9 00401EEA ADD ESP,70 00401EED RETN

Let's begin with a quick summary of the most important operations performed by the function in Listing 6.8. The function starts by opening the archive file. This is done by calling a function at 00401670, which opens the archive and proceeds to call into the header and password verification function at 004011C0, which you analyzed in Listing 6.3. After 00401670 returns the function proceeds to create a hash object of the same type you saw earlier that was used for calculating the password hash. This time the algorithm type is 0x8003, which is ALG_SID_MD5. The purpose of this hash object is still unclear.

The code then proceeds to read the Cryptex header into the same global variable at 00406058 that you encountered earlier, and to search the file list for the relevant file entry.

The scanning of the file list is performed by calling a function at 004017B0, which goes through a familiar route of scanning the file list and comparing each name with the name of the file being extracted. Once the correct item is found the function retrieves several fields from the file entry. The following is the code that is executed in the file searching routine once a file entry is found.

00401881 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+10] 00401885 LEA EAX,DS:[ESI+ESI*4] 00401888 ADD EAX,EAX 0040188A ADD EAX,EAX 0040188C SUB EAX,ESI 0040188E MOV EDX,DS:[ECX+EAX*8+8] 00401892 LEA EAX,DS:[ECX+EAX*8] 00401895 MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+24] 00401899 MOV DS:[ECX],EDX 0040189B MOV ECX,SS:[ESP+28] 0040189F TEST ECX,ECX 004018A1 JE SHORT cryptex.004018BC 004018A3 LEA EDX,DS:[EAX+C] 004018A6 MOV ESI,DS:[EDX] 004018A8 MOV DS:[ECX],ESI 004018AA MOV ESI,DS:[EDX+4] 004018AD MOV DS:[ECX+4],ESI 004018B0 MOV ESI,DS:[EDX+8] 004018B3 MOV DS:[ECX+8],ESI 004018B6 MOV EDX,DS:[EDX+C] 004018B9 MOV DS:[ECX+C],EDX 004018BC MOV EAX,DS:[EAX+4]

First of all, let's inspect what is obviously an optimized arithmetic sequence of some sort in the beginning of this sequence. It can be slightly confusing because of the use of the LEA instruction, but LEA doesn't have to deal with addresses. The LEA at 00401885 is essentially multiplying ESI by 5 and storing the result in EAX. If you go back to the beginning of this function, it is easy to see that ESI is essentially employed as a counter; it is initialized to zero and then incremented by one with each item that is traversed. However, once all file entries in the current cluster are scanned (remember there are OxlA entries), ESI is set to zero again. This implies that ESI is used as the index into the current file entry in the current cluster.

Let's return to the arithmetic sequence and try to figure out what it is doing. You've already established that the first LEA is multiplying ESI by 5. This is followed by two ADDs that effectively multiply ESI by itself. The bottom line is that ESI is being multiplied by 20 and is then subtracted by its original value. This is equivalent to multiplying ESI by 19. Lovely isn't it? The next line at 0040188E actually uses the outcome of this computation (which is now in EAX) as an index, but not before it multiplies it by 8. This line essentially takes ESI, which was an index to the current file entry, and multiplies it by 19 * 8 = 152. Sounds familiar doesn't it? You're right: 152 is the file entry length. By computing [ECX+EAX*8+8], Cryptex is obtaining the value of offset +8 at the current file entry.

We already know that offset +8 contains the file size in clusters, and this value is being sent back to the caller using a parameter that was passed in to receive this value. Cryptex needs the file size in order to extract the file. After loading the file size, Cryptex checks for what is apparently another output parameter that is supposed to receive additional output data from this function, this time at [ESP+28]. If it is nonzero, Cryptex copies the value from offset +C at the file entry into the pointer that was passed and proceeds to copy offset +10 into offset +4 in the pointer that was passed, and so on, until a total of four DWORDs, or 16 bytes are copied. As a reminder, those 16 bytes are the ones that looked like junk when you dumped the file list earlier. Before returning to the caller, the function loads offset +4 at the current file entry and sets that into EAX—it is returning it to the caller.

To summarize, this sequence scans the file list looking for a specific file name, and once that entry is found it returns three individual items to the caller. The file size in clusters, an unknown, seemingly random 16-byte sequence, and another unknown DWORD from offset +4 in the file entry. Let's proceed to see how this data is used by the file extraction routine.

After returning from 004017B0, Cryptex proceeds to scan the supplied file name for backslashes and loops until the last backslash is encountered. The actual scanning is performed using the C runtime library function strchr, which simply returns the address of the first instance of the character, if one is found. The address that points to the last backslash is stored in [ESP+20] ; this is essentially the "clean" version of the file name without any path information. One instruction that draws attention in this otherwise trivial sequence is the one at 00401C9E.

00401C9E MOV EDI,EDI

You might recall that we've already seen a similar instruction in the previous chapter. In that case, it was used as an infrastructure to allow people to trap system APIs in Windows. This case is not relevant here, so why would the compiler insert an instruction that does nothing into the middle of a function? The answer is simple. The address in which this instruction begins is unaligned, which means that it doesn't start on a 32-bit boundary. Executing unaligned instructions (or accessing unaligned memory addresses in general) takes longer for 32-bit processors. By placing this instruction before the loop starts the compiler ensured that the loop won't begin on an unaligned instruction. Also, notice that again the compiler could have used NOPs, but instead used this instruction which does nothing, yet accurately fills the 2-byte gap that was present.

After obtaining a backslash-free version of the file name, the function goes to create the new file that will contain the extracted data. After creating the file the function checks that 004017B0 actually found a file by testing EBP, which is where the function's return value was stored. If it is zero, Cryptex displays a file not found error message and quits. If EBP is nonzero, Cryptex calls the familiar 00401030, which reads and decrypts a sector, while using EBP (the return value from 004017B0) as the second parameter, which is treated as the cluster number to read and decrypt.

So, you now know that 004017B0 returns a cluster index, but you're not sure what this cluster index is. It doesn't take much guesswork to figure out that this is the cluster index of the file you're trying to extract, or at least the first cluster for the file you're trying to extract (most files are probably going to occupy more than one cluster). If you go back to our discussion of the file lookup function, you see that its return value came from offset +4 in the file entry (see instruction at 004018BC). The bottom line is that you now know that offset +4 in the file entry contains the index of the first data cluster.