Chapter 9

Cryptography

9.1 INTRODUCTION

Cryptography is the study of mathematical techniques related to aspects of information security such as confidentiality, data integrity, entity authentication, and data origin authentication. It is derived from the two Greek words kryptos’, which means ‘secret’, and ‘graph’, which means ‘writing’. Cryptography is not the only means of providing information security, but rather one set of techniques. Cryptography helps to store sensitive information or transmit it across insecure networks (like the Internet) so that it cannot be read by anyone except the intended recipient.

While cryptography is the science of securing data, cryptanalysis is the science of analyzing and breaking secure communication. Classical cryptanalysis involves an interesting combination of analytical reasoning, application of mathematical tools, pattern finding, patience, determination, and luck. Persons or systems performing cryptanalysis in order to break a cryptosystem are also called attackers. Attackers are also known as interlopers, hackers, or eavesdroppers. The process of attacking a crypto-system is called hacking or cracking.

In the early days, cryptography was performed manually. Though a lot of improvements have taken place in the implementation part, but basic framework of performing cryptography has remained almost same. Some cryptographic algorithms are very trivial to understand, replicate, and thus can be easily cracked. Alternatively there are some cryptographic algorithms which are really highly complicated and hence very difficult to crack. There is somewhat a false notion that cryptography is only intended for diplomatic and military communications. In fact, cryptography has different commercial uses and applications. Say, for example, when credit card information is used on the Internet (which we do very often), to secure that data from hackers, it needs to be encrypted. Basically, cryptography is all about increasing the level of privacy of individuals and groups.

Cryptology is the combined study of cryptography and cryptanalysis. The origin of the word cryptology is also from the two Greek words ‘kryptos’, meaning ‘secret’, and ‘logos’, meaning ‘science’.

9.2 PLAIN TEXT, CIPHER TEXT, AND KEY

When we normally communicate, for example, with our family members, friends, or colleagues, we do not bother about its security aspects. We thus communicate in the normal language which is understandable by both the sender and the recipient. Such a message is called plain text message. Plain text is also called clear text.

Definition 9.1: Plain text or clear text refers to any message that is not encrypted.

However, there are situations when we are concerned with the secrecy of the message and we do not want any eavesdropper to get an idea of the message. In such situations we will not communicate in plain text. Hence, we will encrypt the data such that it is not understandable until it has been converted into plain text. The codified message is called cipher text.

Definition 9.2: Cipher text refers to any plain text message which is codified using any suitable scheme.

Another very important aspect of cryptography is the key. We define the key as follows.

Definition 9.3: A key is a value that causes a cryptographic algorithm to run in a specific manner and work on the plain text to produce a specific cipher text as an output. The security of the algorithm increases with the increase in key size.

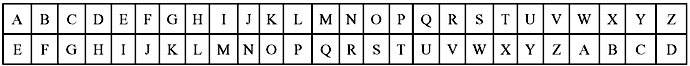

Example 9.1: Our scheme is to replace each alphabet in the message with the alphabet that is actually four alphabets down the order. Hence, each A will be replaced by E, B will be replaced by F, and so on. The replacements are shown in Figure 9.1

Figure 9.1 Replacements of Each Alphabet with an Alphabet Four Places Down the Line

Now a plain text is taken as:

Using the above-mentioned scheme, the cipher text becomes

9.3 SUBSTITUTION AND TRANSPOSITION

There are two primary ways in which a plain text message can be coded to obtain the corresponding cipher text—substitution and transposition. When the two approaches are used together, the technique is called product cipher. An algorithm for transforming a plain text message into one that is cipher text by transposition and/or substitution methods is known as cipher.

Substitution—To produce cipher text, this operation replaces bits in the plain text with other bits decided upon by the algorithm. The substitution then has to be just reversed to get back the original plain text from the cipher text. Several substitution techniques are commonly used. To name a few are Caesar cipher, modified Caesar cipher, mono-alphabetic cipher, homophonic substitution cipher, poly-alphabetic substitution cipher, polygram substitution cipher, etc.

Caesar Cipher—The Caesar cipher is named after Julius Caesar, who, according to Suetonius, used it with a shift of three alphabets down the line to protect messages of military significance. While Caesar was recorded to be the first to use this scheme, other substitution ciphers are known to have been used earlier. Thus messages were sent, by replacing every A in the original message with a D, every B with an E, and so on, through the alphabet.

Example 9.2:

Plain text: Meet me after the party

Cipher text: Phhw ph diwhu wkh sduwb

Only someone who knew the ‘shift by 3’ rule could decipher the messages. The Caesar cipher is a very weak scheme of hiding plain text messages.

Modified Caesar Cipher—The scheme of Caesar cipher can be generalized and made more complicated by modifying it. The cipher text alphabets corresponding to the original plain text alphabets may not necessarily be three places down the order, but instead be any places down the order. Thus, the replacement scheme is not fixed; it has to be decided first. But once the scheme is decided, it would be constant and will be used for all other alphabets in the message. Thus A may be replaced by any other alphabet in the English alphabet set, i.e., B through Z. Hence, in the modified Caesar cipher, for each alphabet we have 25 possibilities of replacement.

Mono-alphabetic Cipher—Though modified Caesar cipher is better than Caesar cipher, yet a cryptanalyst has to try out maximum of 25 possible attacks to decipher the message. So, rather than using a uniform scheme for all alphabets in a plain text message, a dramatic increase in the key space can be achieved by allowing a scheme of arbitrary substitution. This means that in a plain text message each A can be replaced by any other random alphabet (B through Z), each B can also be replaced by any other alphabet (A or C through Z), and so on. The crucial point is that there is no relation between the replacements of A and that of B. In this way we can now have any permutation and combination of the 26 alphabets, which gives 26! or greater than 4 × 1026 possibilities.

Homophonic Substitution Cipher—The homophonic substitution cipher involves replacing each letter with a variety of substitutes, the number of potential substitutes being proportional to the frequency the letter. For example, the letter A accounts offor roughly 8% of all letters in English, so we assign eight symbols to represent it. Each time an A appears in the plain text it is replaced by one of the eight symbols chosen at random, and so by the end of the encipherment each symbol constitutes roughly 1% of the cipher text. The letter B accounts for 2% of all letters, so we assign two symbols to represent it. Each time B appears in the plain text either of the two symbols can be chosen, so each symbol will also constitute roughly 1% of the cipher text. This process continues throughout the alphabet, until we get to Z, which is so rare that is has only one substitute.

Poly-alphabetic Cipher—Poly-alphabetic substitution ciphers were first described in 1467 by Leone Battista Alberti in the form of discs. Johannes Trithemius, in his book Steganographia (Ancient Greek for ‘hidden writing’), introduced the now more standard form of tabula recta, a square with 26 alphabets in it. Each alphabet was shifted one letter to the left from the one above it, and started again with A after reaching Z. A more sophisticated version using mixed alphabets was described in 1563 by Giovanni Battista della Porta. The Vigenére cipher is the best known and one of the simplest examples of poly-alphabetic substitution ciphers. The cipher uses multiple one-character keys. Each of the keys encrypts one plain text character. The first key encrypts the first plain text character; the second key does the same for the second plain text character; and so on. After all the keys are used they are recycled. Thus if we have 35 one-letter keys, every 35th character in the plain text would be replaced with the same key. This number (in this case 35) is called the period of the cipher.

Polygram Substitution Cipher—In a polygram substitution cipher, plain text letters are substituted in larger groups, instead of substituting letters individually. For example, sequences of two plain text characters (digrams) may be replaced by other digrams. The same may be done with sequences of three plain text characters (trigrams), or more generally using n-grams. In full digram substitution over an alphabet of 26 characters, the key may be any of the 262 digrams, arranged in a table with row and column indices corresponding to the first and second characters in the digram, and the table entries being the cipher text digrams substituted for the plain text pairs. There are then (262)! keys.

Transposition—All the techniques discussed so far involve the substitution of a plain text alphabet with a cipher text alphabet. A very different kind of mapping is achieved by performing some sort of permutation on the plain text alphabets. This technique is referred to as a transposition cipher. We discuss here some of the transposition techniques.

Rail Fence Technique—The simplest transposition technique is the rail fence technique, in which the plain text is written down as a sequence of diagonals and then read off as a sequence of rows. Rail fence technique is not very sophisticated and is quite simple for a cryptanalyst to break into. Let us take an example to illustrate the rail fence technique.

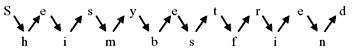

Example 9.3: Suppose a plain text message is ‘She is my best friend’. Now first we arrange the plain text message as a sequence of diagonals, as shown in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2 Rail Fence Technique

This creates a zigzag sequence as shown. Now read the text rowwise, and write it sequentially. Thus, we have the cipher text as follows:

Columnar Transposition Technique—A more complex scheme is to write the message in a rectangle of pre-defined size, row by row, and read the message off, column by column, but permute the order of the columns. The order of the columns then becomes the key to the algorithm. The message thus obtained is the cipher text message.

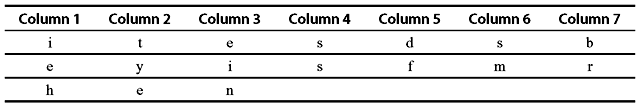

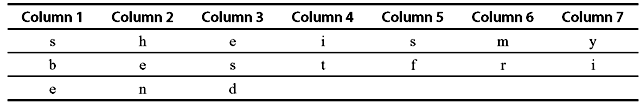

Example 9.4: Let us illustrate the technique with the same plain text message ‘She is my best friend’. Let us consider a rectangle with seven columns. When we write the message in the rectangle rowwise (suppressing spaces), it appears as shown in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3 Columnar Transposition Technique

Now, let us decide the order of columns arbitrarily as, say 4 3 1 7 5 6 2. Then read the text in the order of these columns. Thus the cipher text becomes:

A simple transposition cipher, as discussed above, is easily recognized because it has the same letter frequencies as the original plain text. For the type of columnar transposition discussed, cryptanalysis is fairly straightforward and involves laying out the cipher text in a matrix and trying out with various column positions. The transposition cipher can be made significantly more secure by performing more than one stage of transposition. The result is a more complex permutation that is not easily reconstructed.

Example 9.5: Thus, if the foregoing message is re-encrypted using the same algorithm with the order of columns as 4 3 1 7 5 6 2, we have the text as shown in Figure 9.4.

Figure 9.4 Columnar Transposition Technique with Multiple Rounds

Now the cipher text becomes:

This technique may be repeated as many times as desired. More the number of iterations more are the complexity of the produced cipher text.

One-Time-Pad—As an introduction to stream ciphers, and to demonstrate that a perfect cipher does exist, we describe the Vernam cipher, also known as the one-time-pad. Gilbert Vernam invented and patented his cipher in 1917 while working at AT&T. Joseph Mauborgne proposed an improvement to the Vernam cipher that yields the ultimate in security. He suggested using a random key which is as long as the message, so that the key need not be repeated. Additionally, the key is to be used to encrypt and decrypt a single message, and then is discarded (hence the name one-time). Each new message requires a new key of the same length as the new message. Such a scheme is unbreakable. It produces random output that bears no statistical relationship to the plain text. Because the cipher text contains no information whatsoever about the plain text, there is simply no way to break the code. An example should illustrate our point.

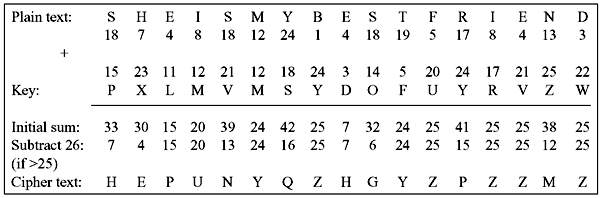

Example 9.6: The scheme is discussed first. Consider each plain text alphabet as a number in an increasing sequence as A = 0, B = 1, C = 2, ... , Z = 25. Do the same for each character of the input key. Then add each number corresponding to the plain text alphabet to the corresponding input key alphabet number. If the sum produced is greater than 26, subtract 26 from the result. Translate each number of the sum back to the corresponding alphabet. This produces the cipher text as shown in Figure 9.5.

Figure 9.5 Vernam Cipher

9.4 ENCRYPTION AND DECRYPTION

In the previous two sections we have already discussed the concepts of plain text and cipher text and also how to transform from one form to the other.

Definition 9.4: Encryption is the process of transforming information (referred to as plain text) using an algorithm (called cipher) to make it unreadable to anyone except those possessing special knowledge, usually referred to as a key.

The result of the process is an encrypted information (referred to as cipher text). Encryption has long been used by militaries and governments to facilitate secret communication. Encryption is now commonly used in protecting information within many kinds of civilian systems. Encryption can be used to protect data ‘at rest’, such as files on computers and storage devices. In recent years, there have been numerous reports of confidential data such as customers’ personal records being exposed through loss or theft of laptops or backup drives. Encrypting such files at rest helps protect them when even physical security measures fail. Encryption is also used to protect data in transit, e.g., data being transferred via networks (e.g., the Internet), mobile telephones, wireless microphones, Bluetooth devices, bank automatic teller machines, etc. There have been numerous reports of data in transit being intercepted in recent years. Encrypting data in transit also helps to secure it as it is often difficult to physically secure all access to networks.

Decryption is exactly opposite of encryption. Encryption transforms a plain text message into cipher text, whereas decryption transforms the cipher text message back to plain text.

Definition 9.5: The reverse process of transforming cipher text messages back to plain text messages is known as decryption.

To encrypt a plain text message an encryption algorithm is applied. Similarly, to decrypt a received encrypted message, a decryption algorithm has to be applied. At the same time, it is to be noted that the decryption algorithm must be the same as the encryption algorithm. Otherwise, decryption would not be able to retrieve the original message. For example, if the encryption has been done using columnar transposition technique whereas the decryption uses rail fence technique, then decryption would yield a totally incorrect plain text. Hence, the sender and receiver must agree on a common algorithm for meaningful communication to take place.

We have already discussed what a key does with plain text and cipher text messages. A key is somewhat similar to the one-time-pad used in Vernam cipher. Anybody may use Vernam cipher to encrypt a plain text message and send it to the recipient who also posses the knowledge of the key being used. However, no one to whom the key is unknown can decrypt the message. In fact, cryptographic mechanisms may be broadly classified into two categories depending on the type of key used for encryption and decryption. The mechanisms are:

Symmetric-key Cryptography—This is the mechanism where the same key is being used for both encryption and decryption.

Asymmetric- or Public-key Cryptography—In this mechanism two different keys are used—one for encryption and the other for decryption. One key is held privately and the other is made public.

9.5 SYMMETRIC-KEY CRYPTOGRAPHY

Symmetric-key cryptography is known by various other terms, such as Secret-Key Cryptography, or Private-Key Cryptography. As already mentioned, symmetric-key algorithms have only one key that is used both to encrypt and to decrypt the message. Hence, on receiving the message, it is impossible to decrypt it unless the key is known to the recipient.

However, there are a few problems with symmetric-key algorithms. The first problem is that of key distribution. That is how to get the key from the sender. Either the recipient has to personally meet the sender to get the key; otherwise the key has to be transmitted to the recipient and hence is accessible by unauthorized persons. This is the main problem of symmetric key cryptography and is called the problem of key distribution or key exchange and it is inherently linked with symmetric-key cryptography.

The second problem is also very serious. Suppose X wants to communicate with Y and also with Z. There should be one key for all communications between X and Y and also a separate key for all communications between X and Z. The same key as used between X and Y cannot be used for communications between X and Z, since in such a situation there is a chance that Z may interpret messages going between X and Y. In a large volume of data exchange this becomes impractical because every sender and receiver pair would require a distinct key.

In symmetric-key cryptography, same algorithm is used by the sender and the recipient. However, the key is changed from time to time. Same plain texts encrypted with different keys result in different cipher texts. Since the encryption algorithm is available to the public, it should be strong enough so that an attacker should not be able to decrypt the cipher text.

9.5.1 Stream Ciphers and Block Ciphers

Cipher texts may be generated from plain texts using two basic symmetric algorithms—stream ciphers and block ciphers.

Stream Cipher—A stream cipher is one that encrypts a digital data stream one bit or one byte at a time. The decryption also happens one bit at a time. Examples of classical stream ciphers are the auto-keyed Vigenère cipher and the Vernam cipher.

Block Cipher—A block cipher is one in which a block of plain text is treated as a whole and used to produce a cipher text block of equal length. Typically, a block size of 64 or 128 bits is used. Decryption also takes one block of encrypted data at a time. Problem occurs with block ciphers when there are repeating text patterns. Since same cipher is generated for the same plain texts, it gives a clue to the cryptanalyst regarding the original plain text. The cryptanalyst can look for repeating strings and try to break them and thus there lies a chance that a large portion of the original message may be broken. To avoid this problem, block ciphers are used in chaining mode. In this mode, the previous block cipher is mixed with the current block, so as to obscure the cipher text. This avoids repeated patterns of blocks with the same plain texts.

We will discuss two of the most popular symmetric-key algorithms in this chapter. They are the Data Encryption Standard (DES) and the International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA). Both of them are block ciphers.

9.6 DATA ENCRYPTION STANDARD

The most popular encryption scheme widely used for over two decades is known as the Data Encryption Standard (DES). This had been adopted by the National Bureau of Standards, now known as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), in 1977. The algorithm itself is referred to as the Data Encryption Algorithm (DEA) by ANSI. Nowadays DES is found to be vulnerable against powerful attacks. However, DES still remains as a landmark in cryptographic algorithms.

In the late 1960s, IBM set up a research project in computer cryptography. The project concluded in 1971 with the development of an algorithm with the designation LUCIFER. LUCIFER is a block cipher that operates on blocks of 64 bits, using a key size of 128 bits. IBM then developed a marketable commercial encryption product which was a refined version of LUCIFER that was more resistant to cryptanalysis but that had a reduced key size of 56 bits. In 1973, the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) issued a request for proposals for a national cipher standard. IBM submitted the results of the refined version of LUCIFER. After intense criticism this was adopted as the Data Encryption Standard in 1977. Actually the users could not be sure that the internal structure of DES was free of any hidden weak points. However, subsequent events, particularly the recent work on differential cryptanalysis, show that DES has a very strong internal structure.

9.6.1 Basic Principle

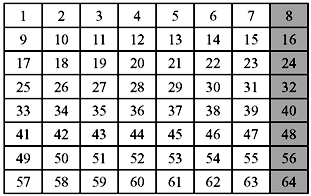

DES encrypts data in blocks of size 64 bits each. It means that DES works on 64 bits of plain text to produce 64 bits of cipher text. The same steps, with the same key, with minor differences are used for decryption. For DES, data are encrypted in 64-bit blocks using a 56-bit key. Actually, the function expects a 64-bit key as input. However, only 56 of these bits are ever used; the other 8 bits can be used as parity bits or simply set arbitrarily. Every eighth bit of the key is ignored to produce a 56-bit key from the actual 64-bit key. This is illustrated in Figure 9.6. The ignored bits are shown shaded in the figure.

Figure 9.6 Key Schedule Calculation

The processing of the plain text proceeds in following phases:

- First, the 64-bit plain text passes through an initial permutation (IP) that rearranges the bits to produce the permuted input.

- Next, the IP produces two halves of the permuted block—Left Plain Text (LPT) and Right Plain Text (RPT).

- This is followed by a phase consisting of 16 rounds of the encryption process, each with its own key, which involves both permutation and substitution functions.

- The output of the last (sixteenth) round consists of 64 bits that are a function of the input plain text and the key.

- At the end the left and right halves of the output are swapped to produce the pre output. Then, the pre output is passed through a final permutation (FP) that is the inverse of the IP function, to produce the 64-bit cipher text.

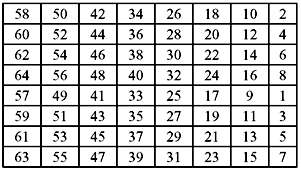

9.6.2 Initial Permutation

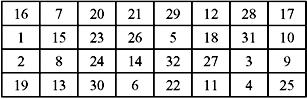

Before the first round takes place the Initial Permutation or IP happens. The IP is defined in Table 9.1. The table may be interpreted as follows. The input to a table consists of 64 bits which are numbered from 1 to 64. These 64 entries in the permutation table contain a permutation of the numbers from 1 to 64. Each entry in the permutation table indicates the position of a numbered input bit in the output, which also consists of 64 bits. The table is to be read from left to right, top to bottom. For example, during IP, the 58th bit of the original plain text will replace the 1st bit. Similarly, the 7th bit of the original plain text is found to replace the 64th bit position. The same rule applies for all other bit positions as shown in Table 9.1.

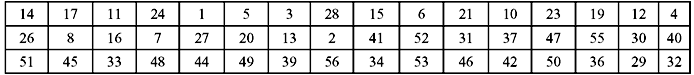

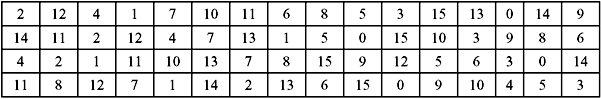

Table 9.1 Initial Permutation Table

As already mentioned, after IP is done, the permuted 64-bit text block is divided into two halves of 32-bit block each. Then the 16 rounds of the encryption process are performed on these two blocks.

9.6.3 Details of Single Round

Each of the 16 rounds can be broadly divided into a step-by-step process. All the steps are discussed as follows:

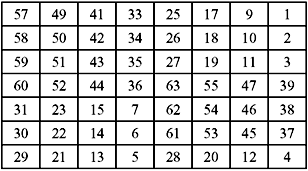

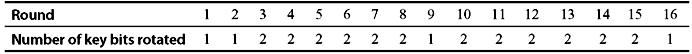

Key Generation—We have already discussed that a 64-bit key is used as input to the algorithm. Every eighth bit of that key is ignored, as indicated by the shading in Fig. 9.6. The key is first subjected to a permutation as shown in Table 9.2. The resulting 56-bit key is then divided into two halves each of 28 bits. At each round, these halves are separately subjected to a circular left shift, or rotation, of 1 or 2 bits, as shown in Table 9.3. After the shift is over, 48 out of these 56 bits are selected. For this selection, Table 9.4 is used. From the table we find that bit numbers 9, 18, 22, 25, 35, 38, 43, and 54 are discarded. In this key transformation process, permutation as well as selection of a 48-bit sub-set of the original 56-bit key is done. Hence, it is also known as compression permutation. Due to this compression permutation technique, a separate subset of key bits is used in each round. This is the reason that DES is quite hard to crack.

Table 9.2 Permuted Key Table

Table 9.3 Schedule of Left Shift of Keys per Pound

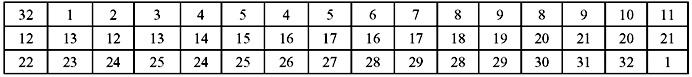

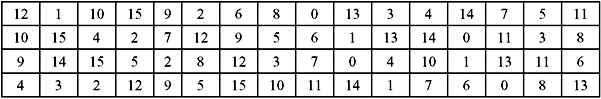

Table 9.4 Compression Permutation

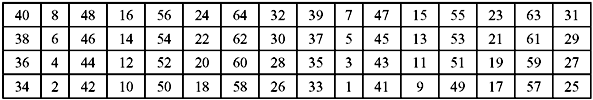

Expansion Permutation—As already mentioned, the initially permuted 64-bit text block is divided into two halves of 32-bit block each known as Left Plain Text (LPT) and Right Plain Text (RPT). This RPT input is now expanded to 48 bits from 32 bits by using Table 9.5, which defines a permutation plus an expansion that involves duplication of 16 of the RPT bits. Hence, this process is known as expansion permutation.

Table 9.5 Expansion Permutation of RPT

The steps for the process are as follows:

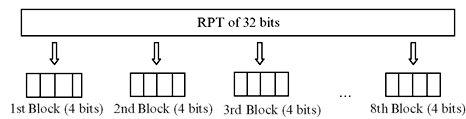

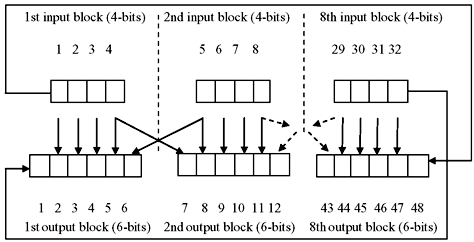

- First the 32-bit RPT is divided into eight blocks of 4 bits each as illustrated in Figure 9.7.

- Now each of these 4-bit blocks is expanded to a corresponding 6-bit block. This is done by adding two more bits in each of these 4-bit blocks. These 2 bits are actually the repetition of the first and the fourth bits of the 4-bit block. The second and the third bits remain unchanged. This is illustrated in Figure 9.8. From the figure, we may see that the 1st input bit goes to the 2nd and 48th position. The 2nd output bit goes to the 3rd position and so on. As a result, we observe that actually the expansion permutation process utilized Table 9.5.

Figure 9.7 Division of 32-Bit RPT into Eight Blocks of 4 Bits Each

Figure 9.8 Expansion Permutation of RPT

We have already seen that by the Key generation process the 56-bit key is compressed to 48-bit key. On the other hand, by the expansion permutation process the 32-bit RPT is expanded into 48 bits. Now the 48-bit RPT is XORed with the 48-bit key. The resulting output is provided to the next step, which is known as S-box substitution.

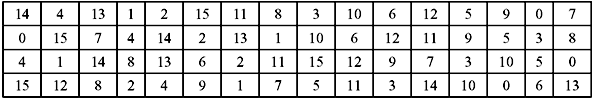

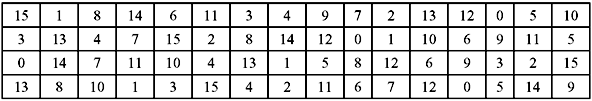

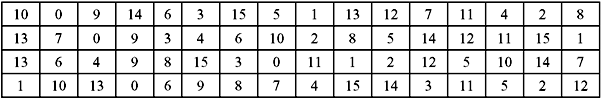

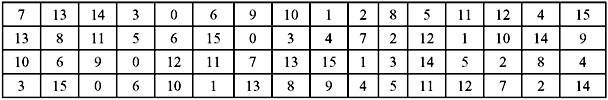

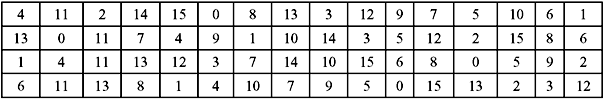

S-Box Substitution—This is a process that accepts 48 bits from the XORed operation as mentioned earlier, and produces a 32-bit output using the substitution technique. The substitution consists of a set of eight substitution boxes also known as S-boxes. Each of the eight S-boxes accepts 6 bits as input and produces 4 bits as output. The 48-bit input block is divided into eight 6-bit sub-blocks. Each sub-block is given to an S-box. Each S-box may be considered to be a table having 4 rows (numbered 0 to 3) and 16 columns (numbered 0 to 15). At the intersection of every row and column, a 4-bit number is present. This is illustrated in Table 9.6a–h.

The interpretation of the table is as follows: The first and last bits of the input to every S-box form a 2-bit binary number. This is to select one of four rows in the table. The remaining four middle bits select one of the sixteen columns. The decimal value in the cell selected by the row and column is then converted to its 4-bit representation to produce the output. Then the outputs of all the S-boxes are combined to form a 32-bit block. This is then supplied to the next stage known as the P-box permutation.

Table 9.6 S-Box Substitution

(a) S-Box 1

(b) S-Box 2

(c) S-Box 3

(d) S-Box 4

(f) S-Box 6

(g) S-Box 7

(h) S-Box8

Let us now consider an example. Suppose in S-box 3 for input 110101, the row is 11 in binary (i.e., 3 in decimal) and the column is 1010 in binary (i.e. 10 in decimal). Thus the value at the intersection of row 3 and column 10 is selected which is 14. Hence, the output is 1110. Note that rows and columns are counted from 0 and not from 1.

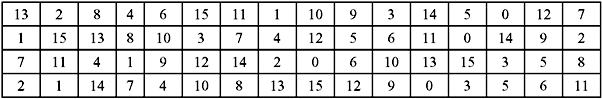

P-Box Permutation—The 48-bit result from the output of S-boxes passes through a substitution function that produces a 32-bit output, which is permuted as defined in Table 9.7. In this permutation, there is no expansion or compression. This is known as P-box permutation.

Table 9.7 P-box Permutation

XOR and Swap—All the operations performed so far was on the 32-bit RPT of the original 64-bit plain text, whereas till now 32-bit LPT is untouched. Now an XOR operation is performed between the output of the P-box permutation and the LPT of the initial 64-bit plain text. Now a final swapping is done by which the result of the XOR operation becomes the new RPT and the old RPT becomes the new LPT.

9.6.4 Inverse Initial Permutation

Finally, at the end of all 16 rounds, the inverse initial permutation is performed. This is a simple transposition technique performed only once, based on Table 9.8. The output of the inverse IP is the 64-bit cipher text.

Table 9.8 Inverse Initial Permutation

9.6.5 DES Decryption

Decryption of DES uses the same algorithm as encryption, and hence the algorithm is reversible. Only difference between the encryption and the decryption process is that the application of the sub-keys is reversed. Say the original key K was divided into K1, K2, ..., K16 for the 16 rounds of encryption. Then, for decryption the key should be used as K16, K15, ..., K1.

9.6.6 Strength of DES

From the time of adoption of DES as a federal standard, there have been lingering concerns about the level of security provided by DES. These concerns, fall into two areas: key size and the cryptographic algorithm. However, as already discussed, the inner workings of the DES algorithm are known completely to the general public. Hence, the strength of DES mainly lies on its key.

The key length of DES is 56 bits. Thus, there are 256 (or approximately about 7.2 × 1016) possible keys. Hence, it may be said that a brute-force attack appears impractical. Assuming that, on average, half the key space has to be searched, a single computer performing one DES encryption per microsecond would take approximately 1,142 years to break the cipher. However, the assumption of one encryption per microsecond is too conservative. It has been postulated by Diffie and Hellman that a parallel machine with 1 million encryption devices, each of which could perform one encryption per microsecond, would bring the average search time down to about 10 h.

9.7 ADVANCE VERSIONS OF DES

Though DES proves to be quite secure, but due to tremendous advance in computing power it seems that DES is also susceptible to possible attacks. Hence, there has been considerable interest in finding an alternative. One of the approaches may be to write a new algorithm which is time-consuming as well as not easy. Moreover, that it has to be tested sufficiently before using it commercially. An alternative approach is to preserve the existing basic DES algorithm and make it stronger by using multiple encryptions and multiple keys. Consequently two advance versions of DES have emerged—double DES and triple DES.

9.7.1 Double DES

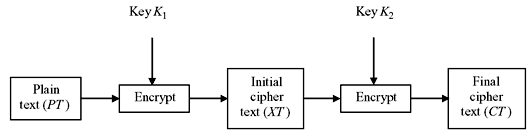

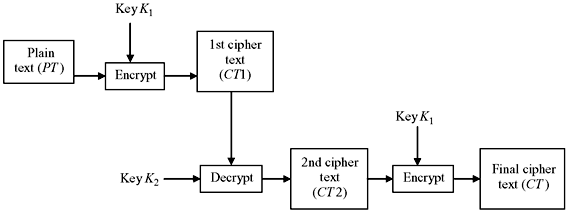

It is a very simple method where the encryption of the plain text is done twice before generating the final cipher text. In this method, two different keys, say K1 and K2, are used for the two stages of encryption. The concept is illustrated in Figure 9.9.

Figure 9.9 Double DES Encryption

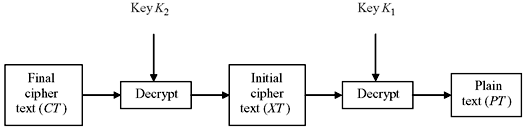

From the figure we find that initially an encryption of the original plain text (PT) is done using the key K1, and the resultant is denoted as XT. Mathematically this may be expressed as XT = E(K1, PT). Again another encryption is performed on the already encrypted plain text with the second key K2 resulting in the final cipher text (CT). This may be mathematically written as CT = E(K2, E(K1, PT)). For decryption, first the key K2 will be used to produce the singly encrypted cipher text (XT). Then this cipher text block will be decrypted using the key K1 to get back the original plain text (PT). Hence, the decryption may be mathematically denoted as PT = D(K1, D(K2, CT)). The process is shown in Figure 9.10.

Figure 9.10 Double DES Decryption

Since, the key length of DES is 56 bits, this double DES scheme apparently involves a key length of 56 × 2 = 112 bits. Thus, it may be concluded that since the cryptanalysis for the basic version of DES requires a search of 256 keys, double DES would require a key search of 2112 keys. However, that is not the case and there is a way to attack this scheme. In fact, the attacking scheme does not depend on any particular property of DES but will work against any block encryption cipher. The algorithm is known as meet-in-the-middle attack.

Let us assume that the attacker knows two basic pieces of information—the plain text block PT and the corresponding cipher text block CT. First, the attacker will encrypt PT for all 256 possible values of K1, which means that XT is calculated. These results are stored in a table and then the table is sorted by the values of XT. This means in this step the cryptanalyst computed XT = E(K1, PT).

Now the reverse operation will be performed, i.e., the known cipher text CT will be decrypted using all 256 possible values of K2. For each decryption, the result is compared with the table, which was computed earlier. In effect, in this step the cryptanalyst computes XT = D(K2, CT). If a match occurs, then the cryptanalyst now is able to find out the possible values of the two keys. Then the two resulting keys are tested against a new known plain text–cipher text pair. If the two keys produce the correct cipher text, then the keys are accepted as correct.

9.7.2 Triple DES

Though double DES is sufficient form of the standpoint of security for all practical purposes, still a better alternative may be triple DES. Depending on the number of keys used, triple DES is of two types—triple DES using three keys and triple DES using two keys.

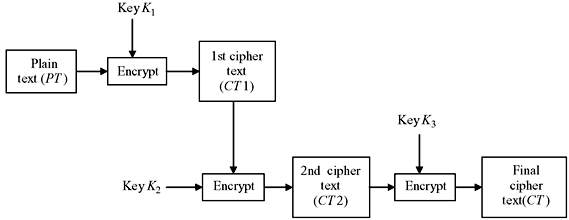

Triple DES Using Three Keys—The basic idea of the method is to use three different keys, namely K1, K2, and K3 for the encryption of the plain text. However, it suffers from the drawback that it requires a key length of 56 × 3 = 168 bits, which may be somewhat difficult for practical purpose. Mathematically it may be defined as CT = E(K3, E(K2, E(K1, PT))). This is illustrated in Figure 9.11. A number of Internet-based applications, including PGP and S/MIME, have adopted three-key triple DES. Decryption of the operation to be performed is given as PT = D(K3, D(K2, D(K1, CT))).

Figure 9.11 Triple DES Encryption with Three Keys

Triple DES Using Two Keys—To avoid the problem of a key of length 168 bits, Tuchman proposed a triple encryption method which uses only two keys. The algorithm follows an encrypt–decrypt–encrypt (EDE) sequence which means:

- First encrypt the original plain text with key K1.

- Then decrypt the output of step 1 with key K2.

- Finally, again encrypt the output of step 2 with key K1 (see Figure 9.12).

Figure 9.12 Triple DES Encryption with Two Keys

Mathematically, we may write CT = E(K1, D(K2, E(K1, PT))). This is illustrated in Figure 9.12. There is no special significance attached to the use of decryption for the second stage. Its only advantage is that it allowss users of triple DES to decrypt data encrypted by users of the older single DES. Triple DES with two keys is a relatively popular alternative to DES. It has been adopted for use in the key management standards ANS X9.17 and ISO 8732.

9.8 ASYMMETRIC-KEY CRYPTOGRAPHY

We have already seen that key distribution under symmetric encryption requires either that two communicants already share a key, which somehow has been distributed to them, or the use of a key distribution centre. Moreover, for each communicating party, a unique key is required. This makes the process more cumbersome.

However, Whitfield Diffie, a student at the Stanford University along with his Professor Martin Hellman, first introduced the concepts of asymmetric-key or public-key cryptography in 1976. Based on the theoretical work of Diffie and Hellman, the first major asymmetric key cryptosystem was developed at MIT and published in 1978 by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Len Adleman. The method is known as RSA algorithm after the first letters of the surnames of the three researchers. As in this method every communicating party possesses a key pair known as public key and private key, hence the problem of key exchange and distribution is solved.

Asymmetric key cryptography relies on one key for encryption and a different but related key for decryption. It is very important to note that even with knowledge of the cryptographic algorithm and the encryption key, it is computationally infeasible to determine the decryption key. The advantage of the system is that each communicating party needs just a key pair for communicating with any number of other communicating parties. In addition, some algorithms, such as RSA, also exhibit an important characteristic, i.e., either of the two related keys can be used for encryption, with the other used for decryption.

9.8.1 Public and Private Key

This is a pair of keys that have been selected so that if one is used for encryption, the other is used for decryption. The exact transformations performed by the algorithm depend on the public or private key that is provided as input. The private key remains secret which should not be disclosed, whereas the public key is for general public. It is to be disclosed to all parties with whom the communication is intended. In fact each party or node publishes its pubic key.

Asymmetric key cryptography works according to the following steps:

- Suppose X wants to send message to Y. Since the public key of Y is known to X, so X encrypts the message using Y’s public key.

- X sends the encrypted message to Y.

- Y will decrypt the message using its private key. It is to be noted that the message may only be decrypted by the private key of Y. And since the private key of Y is unknown to everybody other than Y, it is highly secure.

- Similarly, if Y intends to send a message to X, the same steps take place in a reverse manner. Y encrypts the message using the public key of X. Hence, only X can decrypt the message back using the private key.

9.9 RSA ALGORITHM

The RSA algorithm is the most popular asymmetric key cryptographic algorithm. The scheme is a block cipher. Here, the plain text and the cipher text are integers between 0 and N. A typical size for N is 1024 bits or 309 decimal digits. That is, N is less than 21024. We examine RSA in this section in some detail, beginning with an explanation of the algorithm.

Plain text is encrypted in blocks. For some plain text block M and cipher text block C, the total process may be summarized as follows:

- Select two large prime numbers P and Q, such that P ≠ Q.

- Calculate N = P × Q.

- Calculate φ(N) = (P – 1)(Q – 1).

- Select an integer E as the public key (i.e., the encryption key) such that it is not a factor of φ(N).

- Calculate D as the private key (i.e., the decryption key) such that:

(D × E) mod φ(N) = 1

- From plain text M the cipher text is calculated as:

C = ME mod N

- This cipher text is sent to the receiver for decryption.

- The cipher text is decrypted to the plain text as:

M = CD mod N

9.9.1 Example of RSA

We now discuss the RSA with an example:

1. Select two prime numbers, P = 17 and Q = 23.

2. Calculate N = P × Q = 17 × 23 = 391.

3. Calculate φ(N) = (P – 1)(Q – 1) = 16 × 22 = 352.

4. Select the public key E such that E is relatively prime to φ(N) = 352 and less than φ(N). The factors of 352 are 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, and 11 (since E = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 11). Now we have to choose E such that none of the factors of E is 2 and 11. Let us choose E as 17 (it could have been any other number that does not have any of the factors 2 and 11).

5. Determine the private key D such that: (D × E) mod (352) = 1.

We have (D × 17) mod (352) = 1. After making some calculations, we find the correct value is D = 145, because (145 × 17) mod (352) = 2465 mod (352) = 1.

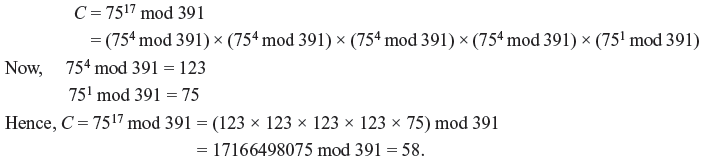

6. Now calculate the cipher text C from plain text M as C = ME mod N.

Let us assume that M = 75. Hence we have

8. Send C as the cipher text to the receiver.

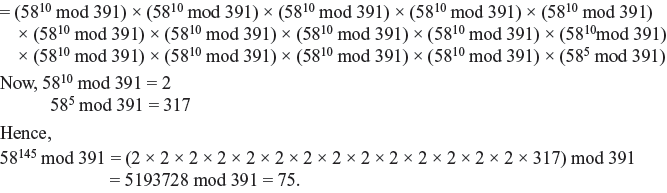

9. For decryption, calculate the plain text for the cipher text as M = CD mod N.

We have M = 58145 mod 391

9.9.2 Strength of RSA

There may be four possible approaches to attack the RSA algorithm. They are as follows.

Brute Force—This process involves trying out all possible private keys. The defense against the brute-force approach is basically to use a large key size. Hence, it is desirable that the number of bits in D should be large. However, we know that both in key generation and in encryption/decryption lot of calculations are involved. Thus, as the size of the key becomes larger the system becomes slower. Thus, we need to be careful in choosing a key size for RSA. However, development in algorithms and tremendous computing powers shows that for the near future a key size in the range of 1024 to 2048 bits seems reasonable.

Mathematical Attacks—This is equivalent in effort to factoring the product of two primes. This may be done in three possible ways:

- Factor N into its two prime factors.

- Determine φ(N) directly, without first determining P and Q.

- Determine D directly, without first determining φ(n).

Of the above-mentioned methods, the most popular way is the task of factoring N into its two prime factors. But with the presently known algorithms, determining D for given E and N appears to be much time-consuming. For a large N with large prime factors, factoring is a hard problem. Researchers suggest that it may take more than 70 years to determine P and Q if N is a 100-digit number.

Timing Attacks—These types of attacks depend on the running time of the decryption algorithm. In fact, timing attacks are applicable to any public-key cryptography systems. Basically, the attack is only on the cipher text. With an analogy, we may say that a timing attack is somewhat like a burglar guessing the combination of a safe by observing how long it takes for someone to turn the dial from number to number. Although the timing attack is a serious threat, some simple counter measures might be implemented as follows:

- It has to be ensured that all exponentiations take the same amount of time before returning a result.

- Adding a random delay to the decryption algorithm will confuse the timing attack.

- Before performing decryption, multiply the cipher text by a random number. This process prevents the attacker from knowing what cipher text bits are being processed inside the computer and hence prevents the bit-by-bit analysis essential to the timing attack.

Chosen Cipher Text Attacks—In this process, first a number of cipher texts are chosen. The attacker selects a plain text, encrypts it with the target’s public key and then gets the plain text back by having it decrypted with the private key. This type of attack basically exploits properties of the RSA algorithm.

To overcome this type of attack, prior to encryption practical RSA-based cryptosystems randomly pad the plain text. This randomizes the cipher text. However, more sophisticated attacks are possible. Then a simple padding with a random value is not sufficient to provide the desired security. In such cases, it is recommended to modify the plain text using a procedure known as optimal asymmetric encryption padding (OAEP). A full discussion of the threats and OAEP are beyond the scope of this current book.

9.10 SYMMETRIC VERSUS ASYMMETRIC-KEY CRYPTOGRAPHY

After discussing both symmetric- and asymmetric-key cryptographies in detail, we saw that the techniques differ in certain aspects and both have some advantages compared to the other. We now want to compare between the two in brief:

- In symmetric-key cryptography, the same key is being used both for encryption and for decryption, whereas in asymmetric-key cryptography we use separate keys for encryption and decryption.

- In symmetric-key cryptography, the resulting cipher text is usually of the same size as the plain text, whereas in the other case, the size of the cipher text is more than the original plain text.

- Symmetric-key cryptography is much faster than the asymmetric one.

- The key exchange or agreement problem of symmetric-key cryptography is totally solved in asymmetric-key cryptography.

- In symmetric-key cryptography number of keys required is equal to the square of the number of participants, whereas in asymmetric-key cryptography it is equal to the number of participants.

9.11 DIFFIE-HELLMAN KEY EXCHANGE

Whitefield Diffie and Martin Hellman were the first to publish a public-key algorithm which solved the problem of key agreement or key exchange. The algorithm is generally referred to as Diffie–Hellman key exchange. The main purpose of the algorithm is to enable two users to securely exchange a key which may then be used for subsequent encryption of messages. But it is to be noted that the algorithm itself is limited only to the exchange of keys, and is not used for encryption or decryption of messages. We will discuss the algorithm in the following section.

9.11.1 The Algorithm

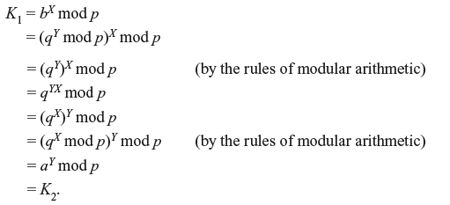

Let us assume that A and B want to make a key agreement for encryption and decryption of messages exchanged between them. For the scheme, A and B first choose two large prime numbers p and q. These two prime numbers can be made public. User A now selects another large random integer X<p and computes a = qX mod p. A sends the number a to B but keeps X value as private. In a similar manner, user B independently selects a random integer Y < p and computes b = qY mod p. B then sends this number b to A and keeps Y value private. User A now computes the secret key as K1 = bX mod p and user B computes the key as K2 = aY mod p. Both the calculations produce an identical result which is shown as follows:

This means that K1 = K2 = K is the symmetric key, which must be kept secret and be used for both encryption and decryption of messages. Now it may seem so that if A and B can calculate K independently, then an attacker also can do the same. The fact is that an attacker only has the following ingredients to work with p, q, a, and b. Thus, the attacker is forced to take a discrete logarithm to determine the key.

For example, to determine the private key of user B, the attacker has to compute Y = dlogq,p(b). Then the key K may be calculated in the same manner as user B calculates it. The security of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange lies in the fact that, it is very difficult to calculate discrete logarithms. For large primes, this task is considered infeasible.

However, Diffie-Hellman key exchange fails in case of a man-in-the-middle attack. In this case, a third person C intercepts A’s public-key value and sends his own public-key value to B. Again as B transmits his public-key value, C substitutes it with his own and sends it to A. A and C thus agree on one shared key and B and C agree on another shared key. Once this is done, C decrypts any messages sent out by A or B. This vulnerability of Diffie–Hellman key exchange may be avoided using asymmetric key operation.

9.12 STEGANOGRAPHY

A plain text message may be hidden in one of two ways—by cryptography or by steganography. Steganography is a technique for hiding a secret message within a larger message in such a way that the presence or contents of the hidden message is not understandable. The methods of steganography conceal the existence of the message, whereas the methods of cryptography render the message unintelligible to outsiders by various transformations of the text. Historically several techniques were used for steganography, namely character marking by overwriting in pencil, making small pin punctures on selected letters, writing in invisible ink etc., to name a few. However, different contemporary methods have been suggested for steganography. Of late, it is found that selected messages can be hidden within digital pictures. It has been shown that a 2.3-megabyte message may be hidden in a single digital snapshot. There are now a number of software packages available that take this type of approach to steganography.

Compared to encryption, there are a lot of drawbacks in steganography. It requires a lot of overhead to hide a relatively few bits of information. Also, once the system is discovered, it becomes virtually worthless. Alternatively, a message can be first encrypted and then hidden using steganography.

9.13 QUANTUM CRYPTOGRAPHY

Dr Charles Bennett and John Smolin were the first ever to witness the quantum cryptographic exchange using polarized light photons over a distance of 32 cm, at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Centre near New York in October 1989.

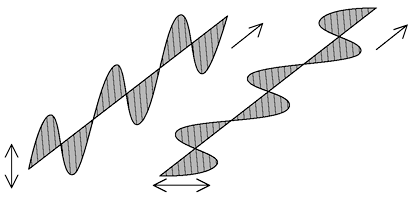

In the early 1980s, two computer scientists, Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard, realized that the application of quantum theory in the field of cryptography could have the potential to create a cipher giving absolute security. The cryptosystem developed by Bennett and Brassard uses polarized light photons to transfer data between two points. As a photon travels through space, it vibrates perpendicularly to its plane of movement and the direction of vibration is known as its polarization. For the sake of simplicity, the depicted directions of vibration are restricted to horizontal and vertical directions (Figure 9.13), although practically the photons will also move in all angles.

Figure 9.13 Vertically and Horizontally Polarized Light

An observer will have no idea which angle of polarizing filter should be used for a certain photon to pass successfully through. The binary ones and zeroes of digital communication may be represented by either of the two schemes—rectilinear polarization or diagonal polarization. Rectilinear polarization may be vertically (↕) and horizontally (↔) polarized photons, while diagonal polarization represents left-diagonally  and right-diagonally

and right-diagonally polarized photons. During transmission, the transmitter will randomly swap between the rectilinear (+) and diagonal (×) schemes, known in quantum cryptography as bases.

polarized photons. During transmission, the transmitter will randomly swap between the rectilinear (+) and diagonal (×) schemes, known in quantum cryptography as bases.

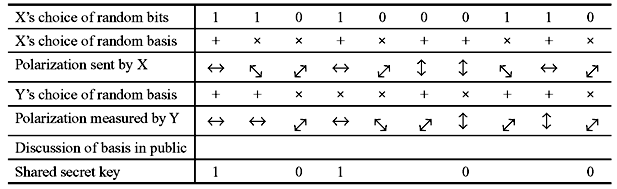

The key distribution is performed in several steps. The sender initially transmits a stream of random bits as polarized photons and continually swapping randomly between any of the four polarization states. The receiver at this point has no idea which schemes are being used for which bit, and hence will also swap randomly between either rectilinear or diagonal schemes. The receiver records the results of the measurements but keeps them secret. The transmitter will now contact the receiver insecurely and tell which scheme was used for each photon. The receiver can now say which ones were guessed correctly. All the incorrect guesses are discarded. These correct cases are now translated into bits (1’s and 0’s) and hence become the key. Both parties now share the secret key.

However, an eavesdropper attempting to intercept the photons will have no idea whether to use a rectilinear or diagonal filter. Around half of the time a totally inaccurate measurement will be made when a photon will change its polarization in order to pass through an incorrect filter. In fact, it will become immediately apparent to both if someone is monitoring the photons in transit, because their use of an incorrect filter is likely to change the polarity of photons before they reach the receiver. If, when comparing a small part of their shared secret key over a public channel, they do not match, it will be clear to both the transmitter and the receiver that the photons have been observed in transit.

The cryptosystem neatly takes advantage of one of the fundamental features of quantum theory, a manifestation of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, that the act of observing will change the system itself. In this way, it is impossible for an attacker to make an accurate measurement of the data without knowledge of which scheme is being used, essentially the cryptographic key.

Example 9.7: Using quantum cryptographic technique, X wants to exchange a key with Y over an insecure channel. The 0° and 90° polarizations are denoted by ↕ and ↔, respectively, while 45° and 135° polarizations are denoted by  and

and  respectively. Show the steps followed.

respectively. Show the steps followed.

Now, X and Y will disclose a subset of the key and compare whether all the bits are identical. Suppose they compare 3rd and 5th bits. In the current example, all the bits match. Hence X and Y can use the remaining three bits (the 1st, 2nd, and 4th) as secret key. If eavesdropper was present, some of the bits in the key obtained by Y will not match with those of X.

9.14 SOLVED PROBLEMS

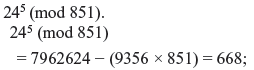

Problem 9.1: A message to encrypt and a message to decrypt are given. The modulus N is 851 and the encryption exponent r = 5 are given. Encrypt the message to encrypt 24; find the decryption exponent s, and decrypt the message to decrypt 111.

Solution: For the first part, we need to compute

Hence the encryption of 24 is 668.

To do the second part, we first need to find the encryption exponent.

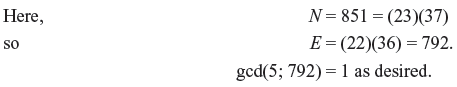

We need to find the multiplicative inverse of r = 5 mod 792; this will be our decryption exponent s.

The idea is to use the Euclidean algorithm to solve 5x + 792y = 1; the value of x that we find is the multiplicative inverse we are looking for.

there are 1 + 158(2) 5’s here and –2 792’s: 317(5) – 2(792) = 1.

So the reciprocal of 5 mod 792 is 317.

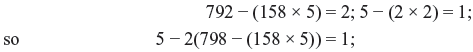

317, 158, 79, 39, 19, 9, 4, 2 are the sequence of powers we need to compute (dividing by 2 each time and throwing away the remainder).

Now we set out to compute 111371 (mod 851) (this will be the decryption we want).

The desired decryption is 148.

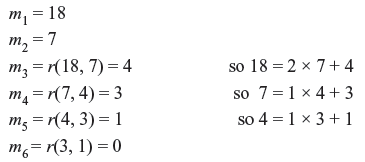

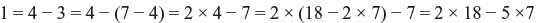

Problem 9.2: Write 1 as a linear combination of 7 and 18.

Solution: We first go through Euclid’s algorithm:

Now we can use these steps to express 1 as a linear combination of 7 and 18, as follows:

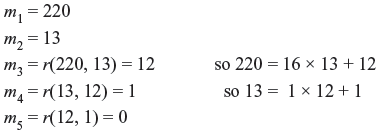

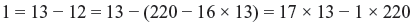

Problem 9.3: Find an integer d such that

Solution: We first express 1 as

Using the Euclidean algorithm:

So using back-substitution we get

so we can take x = 17, y = –1. As explained, we can now take d = 17.

Problem 9.4: Two prime numbers are given as P = 17 and Q = 29. Evaluate N, E and D in an RSA encryption process.

Solution: Here P = 17 and Q = 29.

Hence,

Now we calculate φ(N) = (P – 1) (Q – 1) = 16 × 28 = 448.

We now select the public key E such that E is relatively prime to φ(N) = 448 and less than φ(N). The factors of 448 are 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, and 7 (since E = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 7). Now we have to choose E such that none of the factors of E is 2 and 7. Let us choose E as 11 (it could have been any other number that does not have any of the factors 2 and 7).

Now we determine the private key D such that (D × E) mod (448) = 1.

We have: (D × 11) mod (448) = 1. After making some calculations, we find the correct value is D = 285, because (285 × 11) mod (448) = 3135 mod (448) = 1.

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS

- The length of the key used in DES is

- 128 bits

- 64 bits

- 32 bits

- 96 bits

Ans. (b)

- A message that is sent in cryptography is known as

- plain text

- cipher text

- cracking

- decryption

Ans. (b)

- _______ is the science and art of transforming messages to make them secure and immune to attacks.

- cryptography

- cryptoanalysis

- either (a) or (b)

- neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (a)

- The ________ is the original message before transformation.

- cipher text

- plain text

- secret text

- none of these

Ans. (b)

- The ________ is the message after transformation.

- cipher text

- plain text

- secret text

- none of these

Ans. (a)

- A(n) ________ algorithm transforms plain text to cipher text.

- encryption

- decryption

- either (a) or (b)

- neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (a)

- A combination of an encryption algorithm and a decryption algorithm is called a ________.

- cipher

- secret

- key

- none of these

Ans. (a)

- The ________ is a number or a set of numbers on which the cipher operates.

- cipher

- secret

- key

- none of these

Ans. (c)

- In a(n) ________ cipher, the same key is used by both the sender and receiver.

- symmetric key

- asymmetric key

- either (a) or (b)

- neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (a)

- In a(n) ________, the key is called the secret key.

- symmetric key

- asymmetric key

- either (a) or (b)

- neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (a)

- In a(n) _________ cipher, a pair of keys is used.

- Symmetric key

- Asymmetric key

- Either (a) or (b)

- Neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (b)

- In an asymmetric-key cipher, the sender uses the ________ key.

- private

- public

- either (a) or (b)

- neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (b)

- A ________ cipher replaces one character with another character.

- substitution

- transposition

- either (a) or (b)

- neither (a) nor (b)

Ans. (a)

- The Caesar cipher is a(n) ________ cipher that has a key of 3.

- transposition

- additive

- shift

- none of these

Ans. (c)

- A(n) ________ is a keyless substitution cipher with N inputs and M outputs that uses a formula to define the relationship between the input stream and the output stream.

- S-box

- P-box

- T-box

- none of these

Ans. (a)

- A(n) ________ is a keyless transposition cipher with N inputs and M outputs that uses a table to define the relationship between the input stream and the output stream.

- S-box

- P-box

- T-box

- none of these

Ans. (b)

- DES has an initial and final permutation block and _________ rounds.

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 18

Ans. (c)

- _________ DES was designed to increase the size of the DES key.

- double

- triple

- quadruple

- none of these

Ans. (b)

- The _________ method provides a one-time session key for two parties.

- Diffie–Hellman

- RSA

- DES

- AES

Ans. (a)

- The __________ attack can endanger the security of the Diffie–Hellman method if two parties are not authenticated to each other.

- man-in-the-middle

- cipher text attack

- plain text attack

- none of these

Ans. (a)

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Differentiate between block cipher and stream cipher.

- What do you mean by symmetric-key and asymmetric-key cryptography? What is ‘man-in-the-middle’ attack?

- What are the functions of P-box and S-box in case of DES algorithm?

- Explain the Diffy–Hellman key exchange algorithm.

- What do you mean by quantum cryptography?

- What is steganography?

- Define block cipher. What do you mean by cipher text?

- Describe RSA algorithm.

- What are the problems in symmetric-key cryptography?

- Explain the main concepts of DES algorithm. What are the shortcomings of DES?

- The following cipher text was obtained from an English plain text using a Caesar shift σd with offset d ∊ Z26:

TVSFP IQWLI IXRYQ FIVSR I

- Find the plain text and the offset d.

- Apply σd repeatedly to the cipher text. What happens?

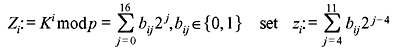

- Alice and Bob agreed on a secret key K by the Diffie–Hellman method using the (unrealistically small) prime p = 216 + 1 and primitive root g = 3 ∊ (Z/p)*. The data sent from Alice to Bob and vice-versa were a = gα = 13242 and b = gβ = 48586. The key K = gαβ was used to generate a byte sequence z1, z2, z3, ... as a one-time-pad in the following way: With

This one-time-pad was XORed with an ASCII–plain text. The resulting cipher text is

Calculate the values of α, β, K and decrypt the cipher text.

- Transform the message ‘Hello how are you’ using rail fence technique.

- Encrypt the following message using mono-alphabetic substitution cipher with key = 5.

Cryptography is interesting subject

- In RSA, the encryption key (E) = 5 and given N = 119. Find out the corresponding private key (D). Also calculate the cipher text C.

- Two prime numbers are given as P = 23 and Q = 31. Evaluate N, D, and E in an RSA encryption process.