Appendix A

Some Related Mathematics

A.1 FERMAT’S LITTLE THEOREM

Fermat’s Little Theorem is often used in number theory in the testing of large primes and simply states as follows.

Theorem A.1: Let p be a prime which does not divide the integer a, then ap− 1 = 1 (mod p).

In more simple language, it may be stated that if p is a prime that is not a factor of a, then when a is multiplied (p − 1) times and the result is divided by p, we get a remainder of 1. For example, if we use a = 5 and p = 3, the rule says that 52 divided by 3 will have a remainder of 1. In fact, 25/3 does have a remainder of 1.

Proof: Start by listing the first (p − 1) positive multiples of a:

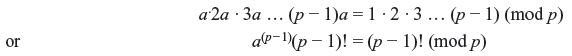

Suppose that ra and sa are the same modulo p, then we have r = s (mod p), so the (p − 1) multiples of a above are distinct and nonzero; that is, they must be congruent to 1, 2, 3, ..., p − 1 in some order. Multiplying all these congruences together we find

Dividing both side by (p − 1)! we get

Thus the theorem is proved.

Sometimes Fermat’s Little Theorem is presented in the following form.

Corollary A.1: Let p be a prime and a any integer, then ap = a (mod p).

Proof: The result is trival (both sides are zero) if p divides a. If p does not divide a, then we can only multiply the congruence in Fermat’s Little Theorem by a to complete the proof.

The theorem is ‘necessary, but not sufficient’. It means that although it is true for all primes, it is not true just for primes, and will sometimes be true for other numbers as well. For example 390 = 1 (mod 91), but 91 is not prime.

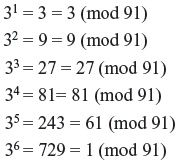

We can test 390 using Fermat’s Little Theorem without even finding out what the actual value of 390 is, by using the patterns of remainders for powers of 3 divided by 91.

Since 36 = 1 (mod 91), then any power of 36 will also be = 1 (mod 91), and 390 = (36)15.

Numbers which meet the conditions of Fermat’s Little Theorem but are not prime are called pseudoprimes. Although 91 is a pseudoprime base 3, it does not work for other bases. There are, however, some numbers that are pseudoprimes to every base to which they are relatively prime. These pseudoprimes are called Carmichael numbers.

A.2 CHINESE REMAINDER THEOREM

The Chinese Remainder Theorem is one of the oldest theorems in number theory. This theorem originated in the book ‘Sun Zi Suan Jing’, or Sun Tzu’s Arithmetic Classic, by the Chinese mathematician Sun Zi, or Sun Tzu, who also wrote ‘Sun Zi Bing Fa’, or Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. The theorem is said to have been used to count the size of the ancient Chinese armies (i.e., the soldiers would split into groups of 3, then 5, 7, etc., and the ‘leftover’ soldiers from each grouping would be counted).

In fact, the theorem is used to speed up the modulo computations. If working modulo is a product of numbers, say mod M = m1m 2 ... mk, Chinese Remainder Theorem lets us work in each moduli mt separately. Since computational cost is proportional to size, this is faster than working in the full modulus M.

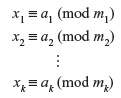

Theorem A.2: Let m1, m2, ..., mkbe pair-wise relatively prime integers. That is, gcd(mi..., mj) = 1, for 1 ≤ i < j ≤ k. Let ai ∊ Zmi, for 1 ≤ i ≤ k and let M = m1m2 ... mk. Consider the system of congruences:

Then there exists a unique x ∊ Zm satisfying this system.

x can be computed as follows:

where

Ci = Mi × (Mi–1 mod M) and Mi = M/mi for 1 ≤ i ≤ k. (A.3)

Proof: We seek to solve the set of equations

where m’s are relatively prime.

Let M = Product of the m’s = m1m2 ... mk.

Let Mi = M/mi, for i = 1, 2, .., n, that is it is the product of all the m’s except mi.

Let  , be such that Mi ·

, be such that Mi ·  (mod mi) (A.4)

(mod mi) (A.4)

So,  = 1/Mi. = Multiplicative inverse (mod mi).

= 1/Mi. = Multiplicative inverse (mod mi).

Eq. (A.4) is always solvable, when gcd(Mi,mi) = 1, which is always true when the m’s are relatively prime, because gcd(M/mi,mi) = 1, because M has no factor m, and m is pair-wise relatively prime with all other m’s.

The formulae (A.2) and (A.3) are known as Chinese remainder theorem. Now we wish to show that x is a solution to equation (A.1), and that is unique.

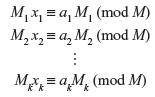

We can convert the equations (A.1) to a common modulus, when we can simply add them, by multiplying each equation by Mi. For example; multiplying the first equation of (A.1) by Mi . gives:

which gives

because

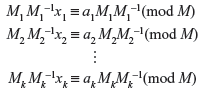

The new equation list becomes

Now multiply each equation by the respective multiplicative inverse of Mi, for i = 1, 2, ..., n.

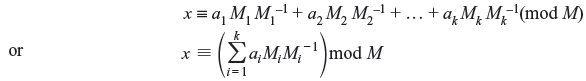

Now sum all the equations and equate the right-hand side to x:

Now we note that in all cases, for i = 1 to n, x = xi = ai(mod mi), i.e., we get the original equations, so x is a solution to the set of equations (A.1).

For instance, taking modulo m1, all the terms will disappear, because they have m1 as a factor, except M1, which is relatively prime to m1. And M1, multiplied by its inverse is 1, modulo m1, so what remains is x = a1 (mod m1). The corresponding result occurs for all the divisors, mi. Therefore, x is a solution to the set of equations (A.1).

Now we prove that the solution is unique.

Suppose y is another solution to the set of equations, which is unique modulo M, so that y and x are distinct. For each of the equations in (A.1)

Using a definition of modulus:

y and x can differ only by a multiple of the modulus, which is zero modulo mi; hence, y and x are equivalent modulo mi.

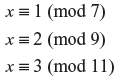

Example A.1: What would be the least total number which gives the remainder 1, 2, and 3, when divided by 7, 9, and 11?

Then, the question becomes, what numbers satisfy the following equations:

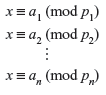

Solution: Given p1, p2, ..., pn, which are positive integers that are pair-wise relatively prime (i.e., say if i is not equal to j, gcd(pi,pj) = 1), then the system of congruences

has a solution that is unique modulo p = p1 *p2 * ... *pn.

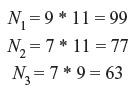

The proof of this actually finds the unique solution. First, we start by defining Nk to be n/nn for each k = 1, 2, ..., n. That is Nk is all of the ni multiplied together except nn. Hence, for our problem, these would be

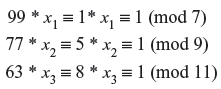

Next, we have to find the solutions xk for each of the equations Nk * xk = 1 (mod nk). For our problem, this is

As a result, we have that x1 = 1, x2 = 2, and x3 = 7. The simultaneous solution to our system then is the number

In our case, s = 1730 = 344 (mod 693). Note that the 693 is from 693 = 7 * 9 * 11.

Hence, x if of the form 693n + 344 or lowest x = 344.

A.3 PRIME NUMBER GENERATION

Those numbers which are bigger than 1 and cannot be divided evenly by any other number except 1 and itself are known as prime numbers. If a number can be divided evenly by any other number not counting itself and 1, then it is not prime and is referred to as a composite number.

However, till 19th century, prime numbers was only an interesting area for mathematicians. But after the need for secrecy, especially during times of war, research in this field gained mileage. Prime numbers can also be used in pseudo-random number generators, and in computer hash tables. In computational number theory, a variety of algorithms make it possible to generate prime numbers efficiently. We discuss here the mostly used and the oldest known algorithm for generating primes, i.e., the Sieve of Erastothenes.

A.3.1 Sieve of Eratosthenes

We discuss here the steps involved to find all the prime numbers less than or equal to a given integer n by Eratosthenes’ method:

- Create a list of consecutive integers from 2 to n (2, 3, 4, ..., n).

- Initially, let p equal 2, the first prime number.

- Starting from p, count up in increments of p and mark each of these numbers greater than p itself in the list. These numbers will be 2p, 3p, 4p, etc.; note that some of them may have already been marked.

- Find the first number greater than p in the list that is not marked. If there was no such number, stop. Otherwise, let p now equal this number (which is the next prime), and repeat from step 3.

When the algorithm terminates, all the numbers in the list that are not marked are prime.

As a refinement, it is sufficient to mark the numbers in step 3 starting from p2, as all the smaller multiples of p will have already been marked at that point. This means that the algorithm is allowed to terminate in step 4 when p2 is greater than n.

Another refinement is to initially list odd numbers only, (3, 5, ..., n), and count up using an increment of 2p in step 3, thus marking only odd multiples of p greater than p itself. This actually appears in the original algorithm. This can be generalized with wheel factorization, forming the initial list only from numbers coprime with the first few primes and not just from odds, i.e., numbers coprime with 2.

Example A.2: Find all the prime numbers less than or equal to 20, proceed as follows.

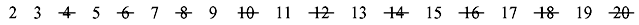

Solution: First generate a list of integers from 2 to 20:

First number in the list is 2; cross out every second number in the list after it (by counting up in increments of 2), i.e., all the multiples of 2:

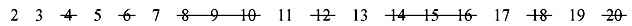

Next number in the list after 2 is 3; cross out every 3rd number in the list after it (by counting up in increments of 3), i.e., all the multiples of 3:

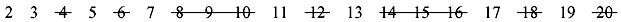

Next number not yet crossed out in the list after 3 is 5; cross out every fifth number in the list after it (by counting up in increments of 5), i.e., all the multiples of 5:

Next number not yet crossed out in the list after 5 is 7; the next step would be to cross out every seventh number in the list after it, but they are all already crossed out at this point, as this number 14 is also multiple of smaller primes because 7 * 7 is greater than 20. The numbers left not crossed out in the list at this point are all the prime numbers below 20: