Chapter 23

Image Processing

23.1 Structure for Image . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 381

23.2 Processing Images . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 387

23.2.1 Image Pixels and Colors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 387

23.2.2 Processing Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 388

23.2.3 Applying a Color Filter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 389

23.2.4 Inverting the Image Colors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 389

23.2.5 Edge Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 390

23.2.6 Color Equalization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 391

The rapid growth of digital photography is one of the most important technological changes

in the past fifteen years. Cameras are now standard on mobile phones, tablets, and laptops.

There is also a proliferation of webcams and surveillance cameras. All of these digital images

call for clever applications to improve our lives. For example, social media websites use facial

recognition in order to make it easier to see photos of your friends. Future applications may

be able to determine what people are doing in images, or sequences of images.

This chapter introduces some basics of image processing. The main goal of this chapter

is to explain how to read and write images, as well as how to modify the colors in the

image pixels. For simplicity, this chapter considers only one image format: bitmap (BMP).

BMP files are not normally compressed and the pixels are independently stored. A more

commonly used format is called Joint Photographic Experts Group, also known as JPEG.

JPEG files are compressed using the discrete cosine transform (DCT). This compression

algorithm is beyond the scope of this book.

23.1 Structure for Image

An image includes many pixels. Each pixel is a dot in the image and it has one single

color. The colors of the pixels are called the “data” of the image. In addition to the colors,

an image has additional information about the image. For example, if it is a photograph,

the file may have the date when the photo was taken, the brand of the camera, etc. The

additional information is separate from the pixel colors, but describes something that may

be interesting about the pixels. This additional information is called “metadata”. When

taking a photograph with a digital camera, the camera records a wide range of metadata.

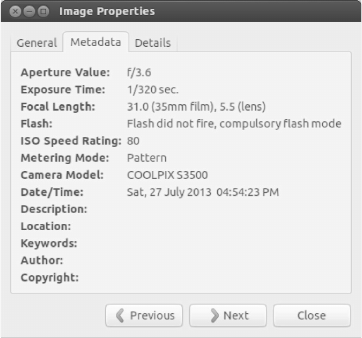

Fig. 23.1 shows the metadata of a photograph taken by a Nikon Coolpix S3500 camera. A

different camera model or a different brand may produce different types of metadata.

A bitmap image file has two parts. The first part is the metadata (also called header).

The second part is the data. The header has 54 bytes in length and the size of the data

depends on the number of pixels.

The header is defined as:

381

382 Intermediate C Programming

FIGURE 23.1: Example of metadata: the exposure time, the focal length, the time and

the date, etc.

// bmph eader . h1

#i f n d e f _BMPHE ADER_H_2

#d ef in e _BM P HEADER _H_3

#in clude < stdint .h >4

// tell compiler not to add space between the attribute s5

#pragma pack (1)6

// A BMP file has a header (54 bytes ) and data7

8

typedef s t ru ct9

{10

uint16_t type ; // Magic ide n tifier11

uint32_t size ; // File size in bytes12

uint16_t reserved1 ; // Not used13

uint16_t reserved2 ; // Not used14

uint32_t offset ; //15

uint32_t header_ size ; // Header size in bytes16

uint32_t width ; // Width of the image17

uint32_t height ; // Height of image18

uint16_t planes ; // Number of color planes19

uint16_t bits ; // Bits per pixel20

uint32_t compres sion ; // Compr e ssion type21

uint32_t imagesize ; // Image size in bytes22

uint32_t xresolu tion ; // Pixels per meter23

uint32_t yresolu tion ; // Pixels per meter24

uint32_t ncolours ; // Number of colors25

uint32_t impo rtantc olour s ; // Impor t ant colors26

27

} BMP _ Header ;28

#e ndif29

This header file introduces several new concepts. The sixth line tells the compiler not to add

any padding between the attributes of a structure. This ensures that the size of a header

Image Processing 383

object is precisely 54 bytes. Without this line, the compiler may align the attributes for

better performance.

Another new concept is including the file <stdint.h>. This file contains definitions of

integer types that are guaranteed to have the same sizes on different machines. The int

type on one machine may have a different size from the int type on another machine. When

reading a 54 byte head from disk, we need to use the same size for the header regardless

of the machine. These types defined in <stdint.h> all have int in them, followed by the

number of bits, and t. Thus, a 32-bit integer is int32 t. If the type is unsigned, then it is

prefixed with a u. An unsigned 16-bit integer is uint16 t.

In the bitmap header structure, some attributes are 16 bits and the others are 32 bits.

They are all unsigned, because none of the attributes can take on negative values. The

order of the attributes is important because the order must meet the bitmap specification.

Reordering the attributes will cause errors. The size of the header is calculated as follows:

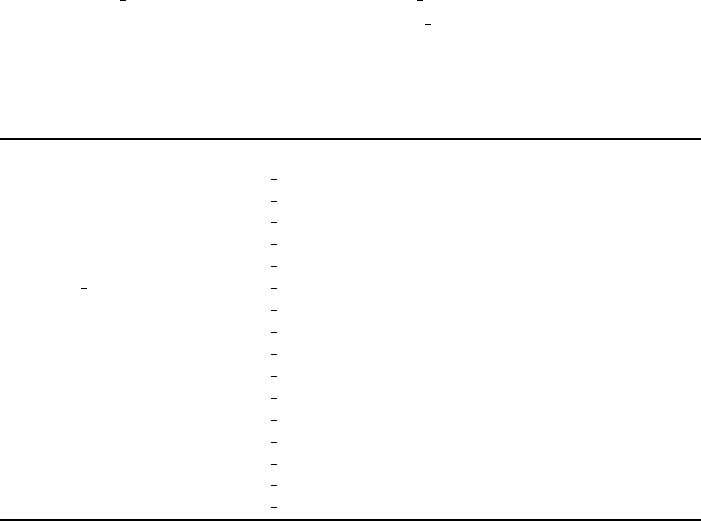

Attribute Type Size (Bytes) Cumulative Size (Bytes)

type uint16 t 2 2

size uint32 t 4 6

reserved1 uint16 t 2 8

reserved2 uint16 t 2 10

offset uint32 t 4 14

header size uint32 t 4 18

width uint32 t 4 22

height uint32 t 4 26

planes uint16 t 2 28

bits uint16 t 2 30

compression uint32 t 4 34

imagesize uint32 t 4 38

xresolution uint32 t 4 42

yresolution uint32 t 4 46

ncolours uint32 t 4 50

importantcolours uint32 t 4 54

To read the image header from file, call fread as follows:

FILE * fptr = fopen ( filename , "r ");1

i f ( fptr == NULL )2

{3

return NULL ;4

}5

BMP_Hea d er header ;6

i f ( fread (& header , s i z e o f ( BM P_Header ) , 1, fptr ) != 1)7

{8

// error9

}10

The header has a “magic number” whose value must be 0X4D42. This is an easy way to

check whether or not the file is a valid BMP file. If the value is not 0X4D42, then it cannot

be a BMP file. Using the magic number is a quick, but imperfect, solution for determining

whether it is a BMP file. The size attribute in the header is the size of the entire file,

including the header. Each pixel has three color values: red, green, and blue. Each color

uses one byte. Thus, the value of bits is 24 bits per pixel. The images considered in this

chapter have only one image plane and compression is not used. The correct value for planes

should be 1; the correct value for compression should be 0.

384 Intermediate C Programming

We cannot store the image pixels in the header struct, because the header has a fixed

size. The header merely tells us how to read the rest of the file. To store the pixels in

memory, we need to use another type of structure. We will call this structure BMP Image,

as shown below.

// bmpimag e . h1

#i f n d e f _BMPIMAG E_H2

#d ef in e _BMP I MAGE_H3

#in clude " bmphea d er .h "4

typedef s t ru ct5

{6

BMP_Hea d er header ;7

unsigned int data_size ;8

unsigned int width ;9

unsigned int height ;10

unsigned int bytes _per_p ixel ;11

unsigned char * data ;12

} BMP_ I mage ;13

#e ndif14

A BMP Image includes the header, data size, width and height (duplicated from the

header), the number of bytes per pixel, and a pointer to the pixel data. The data size is

the size of the file after subtracting the size of the header, i.e., sizeof(BMP Header). Even

though sizeof(BMP Header) is 54, it is bad to write 54 directly. The size can be derived from

sizeof(BMP Header). Few people reading the code will know what 54 means, but every C

programmer will instantly understand sizeof(BMP Header). Therefore, you should not use

“54”. The number of bytes per pixel is the number of bits per pixel divided by 8. because

one byte is 8 bits. The following listing shows the header file and an implementation of

reading and saving image files.

// bmpfile .h1

#i f n d e f _BMPFILE _H_2

#d ef in e _BMP F ILE_H_3

#in clude " bmpimage .h "4

// open a BMP image given a filena m e5

// return a pointer to a BMP image if success6

// returns NULL if failure .7

BMP_Image * BMP_ o pen ( const char * fi l ename );8

// save a BMP image to the given a filename9

// return 0 if failure10

// return 1 if success11

int BMP_save ( const BMP_Image * image , const char * filen a me ) ;12

// release the memory of a BMP image st r ucture13

void BMP_des troy ( BMP_Im age * image );14

#e ndif15

// bmpfile .c1

#in clude < stdio .h >2

#in clude < stdlib .h >3

#in clude " bmpfile . h"4

// correct values for the header5

#d ef in e MAGI C _VALUE 0 X4D426

#d ef in e BIT S_PER_ PIXEL 247

Image Processing 385

#d ef in e NUM_PLAN E 18

#d ef in e COMP R ESSION 09

#d ef in e BIT S _PER_B YTE 810

11

// return 0 if the header is invalid12

// return 1 if the header is valid13

s t a t i c i n t chec kHeader ( B MP_Header * hdr )14

{15

i f (( hdr -> type ) != M AGIC_VAL UE )16

{17

return 0;18

}19

i f (( hdr -> bits ) != BITS_ P ER_PI X EL )20

{21

return 0;22

}23

i f (( hdr -> planes ) != NUM _ PLANE )24

{25

return 0;26

}27

i f (( hdr -> co mpression ) != C O MPRESSIO N )28

{29

return 0;30

}31

return 1;32

}33

// close opened file and release memory34

BMP_Image * cleanUp ( FILE * fptr , BM P _Image * img )35

{36

i f ( fptr != NULL )37

{38

fclose ( fptr ) ;39

}40

i f ( img != NULL )41

{42

i f ( img -> data != NULL )43

{44

free ( img -> data ) ;45

}46

free ( img );47

}48

return NULL ;49

}50

BMP_Image * BMP_ o pen ( const char * fi l ename )51

{52

FILE * fptr = NULL ;53

BMP_Image * img = NULL ;54

fptr = fopen ( filename , " r") ; // " rb " u nnecessa r y in Linux55

i f ( fptr == NULL )56

{57

return cleanUp ( fptr , img ) ;58