Chapter 8. JSON and Hypermedia

Imagine building an application in HTML for use in a web browser. You can add forms, links, and buttons by using standard HTML, and the browser renders your new controls without requiring a new release of the browser. In the “olden days,” it didn’t work this way. If we released a new version of our server-side application with new functionality, we often had to release a new version of the client code to pair with it. Browsers changed this expectation.

We now live in a world where “rich clients” are coming back in the form of apps on people’s devices. We could just have phones access web pages, but for various reasons, people (and companies) want native apps as icons that they can touch on their devices. So how can we get rich native apps back, while still benefitting from the configurability of the browser? Hypermedia. We send not only the data, but also the actions the user can take on the data, along with a representation of how to trigger that action.

So far, the RESTful API calls and JSON responses in this book have been isolated (without reference to other calls). Each JSON response from the Speakers API has just contained data about the speaker, but without providing any information about other related resources and actions.

Hypermedia enables a REST API to guide its Consumers on the following:

-

Links to other related resources (e.g., other APIs). For example, a Conference API could provide links to the Reservation, Speaker, or Venue APIs so that Consumers could learn more about the conference and the speakers, and purchase a ticket.

-

Semantics on the data returned by an API. This metadata documents the data in the JSON response, and defines the meaning of the data elements.

-

Additional actions that they can take on the current resource exposed by the API. For example, a Speakers API could provide more than just CRUD operations. How about a set of links that lead and guide a speaker through the speaker proposal process (in order to speak at a conference)?

Hypermedia groups resources together and guides a Consumer through a series of calls to achieve a business result. Think of Hypermedia as the API equivalent of a web-based shopping cart that leads the Consumer through the buying process and (hopefully) to an eventual purchase. A Hypermedia format provides a standard way for Consumers to interpret and process the link-related data elements from an API response.

In this chapter, we’ll show how to compare these well-known JSON-based Hypermedia formats:

-

Siren

-

JSON-LD

-

Collection+JSON

-

json:api -

HAL

Comparing Hypermedia Formats

We’ll use the Speaker data from previous chapters to drive the discussion of Hypermedia formats.

The following invocation to the fictitious myconference Speakers API might return:

GEThttp://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456{"id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true}

To see a list of a speaker’s presentations, make another API call:

GEThttp://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations[{"id":"1123","speakerId":"123456","title":"Enterprise Node","abstract":"Many developers just see Node as a way to build web APIs ...","audience":["Architects","Developers"]},{"id":"2123","speakerId":"123456","title":"How to Design and Build Great APIs","abstract":"Companies now leverage APIs as part of their online ...","audience":["Managers","Architects","Developers"]}]

Let’s see how to represent the Speaker and Presentation APIs using several Hypermedia formats.

My Opinion on Hypermedia

All architects and developers have opinions that shape the way they evaluate a particular technology. Before we review and compare each Hypermedia format, I’ll let you know my opinion on Hypermedia. Hypermedia is powerful and provides rich meta-data to the data returned by an API, but it is controversial. Many people love it, and other people hate it, and I’m somewhere between these two groups.

Many people in the REST and Hypermedia communities believe that adding meta-data on operations and semantic data definitions to a JSON payload is helpful. I respect everyone’s opinion, but I believe in the use of links to other resources only for these reasons:

-

Additional information on operations and data definitions is unnecessary if you document your API properly in the first place. Why should the JSON data returned from each API call return information on actions and data types? This seems like clutter when you have the following situations:

-

OpenApi (formerly Swagger), RAML, and API Blueprint can all provide this information in an API’s documentation.

-

JSON Schema describes the data types for the JSON data representation.

-

-

Hypermedia adds complexity to the JSON payload returned by an API. With richer/more functional Hypermedia formats, the following are true:

-

The original data representation is altered and difficult to interpret. Most of the formats shown in this chapter alter or embed the original data representation of the resource, which makes it harder for Consumers to understand and process.

-

You have to spend more time and effort to explain how to use your API, and Consumers will move on to something simpler.

-

The payload is larger and takes up more network bandwidth.

-

-

Simple links to other related resources are great because they guide an API Consumer through the use of your API(s) without altering the original JSON data representation.

Siren

Structured Interface for Representing Entities (Siren) was developed in 2012.

It was designed to represent data from Web APIs, and works with both JSON and XML.

You can find Siren on GitHub.

Siren’s Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA)

media type is application/vnd.siren+json.

The key concepts in Siren are as follows:

- Entities

-

An Entity is a resource that is accessible with a URI. It has properties and Actions.

- Actions

- Links

Example 8-1 shows the Speaker data in Siren format based on the following HTTP Request:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.siren+json

Example 8-1. data/speaker-siren.json

{"class":["speaker"],"properties":{"id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true},"actions":[{"name":"add-presentation","title":"Add Presentation","method":"POST","href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations","type":"application/x-www-form-urlencoded","fields":[{"name":"title","type":"text"},{"name":"abstract","type":"text"},{"name":"audience","type":"text"}]}],"links":[{"rel":["self"],"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456"},{"rel":["presentations"],"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations"}]}

In this example, the speaker Entity is defined as follows:

-

classindicates the class of the resource (in this case,speaker). -

propertiesis an Object that holds the representation of the resource. It’s the real data payload from an API response. -

actionsdescribes the Actions that can be taken on aspeaker. In this case, theactionsindicate that you can add apresentationto aspeaker. -

linksprovides links toself(the current resource) andpresentations, a URI that returns the list of thespeaker’s presentations.

Siren provides excellent metadata for describing the available actions on an Entity (resource). Siren has classes (types) to describe the data, but does not provide data definitions (semantics) like JSON-LD.

JSON-LD

JavaScript Object Notation for Linking Data (JSON-LD) became a W3C standard in 2014.

It was designed as a data-linking format to be used with REST APIs, and it works with NoSQL databases such

as MongoDB and CouchDB. You can find more information at the main JSON-LD site, and you can find

it on GitHub. The JSON-LD

media type is application/ld+json, and .jsonld is the file extension. JSON-LD has an active community

and large working group because of its status with the W3C.

Example 8-2 shows the Speaker data in JSON-LD format based on the following HTTP Request:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.ld+json

Example 8-2. data/speaker.jsonld

{"@context":{"@vocab":"http://schema.org/Person","firstName":"givenName","lastName":"familyName","email":"email","tags":"http://myconference.schema.com/Speaker/tags","age":"age","registered":"http://myconference.schema.com/Speaker/registered"},"@id":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456","id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true,"presentations":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations"}

In this example, the @context Object provides the overall context for the Speaker

data representation. In this case, @context does more than merely list the fields.

Rather, @context (in conjunction with @vocab) seeks to provide unambiguous semantic

meaning for each data element that comprises the speaker Object. Here are the specifics:

-

The Schema.org site provides unambiguous definitions for commonly used data elements such as age and Person.

-

@vocabsets the base type to Person and allows you to extend it with other fields (e.g.,tagsorregistered) for thespeaker. -

@idis essentially the URI, the unique ID for accessing a particularspeaker.

Notice that the core JSON representation of the speaker remains unchanged, which is a major

selling point if you have an existing API. This additive approach makes it easier to adopt

JSON-LD gradually, without breaking your API Consumers. The existing JSON representation is undisturbed,

which enables you to iteratively add the semantics of data linking to your API’s data representation.

Note that http://myconference.schema.com does not exist. Rather, it’s shown for the sake of the example. If you need a definition that doesn’t exist on Schema.org, you’re free to create one on your own domain. Just be sure that you provide good documentation.

Example 8-3 shows a speaker’s list of presentations in JSON-LD format based on the following HTTP Request:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations Accept: application/vnd.ld+json

Example 8-3. data/presentations.jsonld

{"@context":{"@vocab":"http://myconference.schema.com/","presentations":{"@type":"@id","id":"id","speakerId":"speakerId","title":"title","abstract":"abstract","audience":"audience"}},"presentations":[{"@id":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations/1123","id":"1123","speakerId":"123456","title":"Enterprise Node","abstract":"Many developers just see Node as a way to build web APIs or ...","audience":["Architects","Developers"]},{"@id":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations/2123","id":"2123","speakerId":"123456","title":"How to Design and Build Great APIs","abstract":"Companies now leverage APIs as part of their online strategy ...","audience":["Managers","Architects","Developers"]}]}

In this example, @context indicates that all the data is related to the concept of

presentations. In this case, we need to define presentations inline because the

http://myconference.schema.com/presentations Object doesn’t exist. If the Object did exist, the

@context would look like this:

"@context":"http://myconference.schema.com/presentations"

You can try out the preceding example on the JSON-LD Playground. This is an excellent online tester that validates JSON-LD documents. Use this tool to validate your data format before writing the code for your API.

JSON-LD by itself does not provide information on operations, nor does it provide semantics on the data representations. HYDRA is an add-on to JSON-LD that provides a vocabulary to specify client-server communication.

Here’s where to find more information on HYDRA:

Example 8-4 shows the list of presentations in JSON-LD format enhanced with HYDRA operations:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations Accept: application/vnd.ld+json

Example 8-4. data/presentations-operations.jsonld

{"@context":["http://www.w3.org/ns/hydra/core",{"@vocab":"http://myconference.schema.com/","presentations":{"@type":"@id","id":"id","speakerId":"speakerId","title":"title","abstract":"abstract","audience":"audience"}}],"presentations":[{"@id":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations/1123","id":"1123","speakerId":"123456","title":"Enterprise Node","abstract":"Many developers just see Node as a way to build web APIs or ...","audience":["Architects","Developers"]},{"@id":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations/2123","id":"2123","speakerId":"123456","title":"How to Design and Build Great APIs","abstract":"Companies now leverage APIs as part of their online strategy ...","audience":["Managers","Architects","Developers"]}],"operation":{"@type":"AddPresentation","method":"POST","expects":{"@id":"http://schema.org/id","supportedProperty":[{"property":"title","range":"Text"},{"property":"abstract","range":"Text"}]}}}

Note the following in this example:

-

operationindicates that you can add a presentation with aPOST. -

@contextpoints to the HYDRA domain to add theoperationkeyword. -

@vocabadds in the http://myconference.schema.com/ domain and thepresentationsdefinition.

JSON-LD by itself is great, because it provides links to other related resources without altering the original data representation. In other words, JSON-LD does not introduce breaking changes to your API Consumers. For the sake of simplicity, use JSON-LD without the overhead of HYDRA.

Collection+JSON

Collection+JSON was created in 2011, focuses on handling data items in a collection, and is similar to the

Atom Publication/Syndication formats. You can find more information at the main Collection+JSON site,

and on GitHub.

The Collection+JSON media type is application/vnd.collection+json.

To be valid, a Collection+JSON response must have a top-level collection Object that holds the following:

Example 8-5 shows the Speaker data in Collection+JSON format based on the following HTTP request:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.collection+json

Example 8-5. data/speaker-collection-json-links.json

{"collection":{"version":"1.0","href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers","items":[{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456","data":[{"name":"id","value":"123456"},{"name":"firstName","value":"Larson"},{"name":"lastName","value":"Richard"},{"name":"email","value":"larson.richard@myconference.com"},{"name":"age","value":"39"},{"name":"registered","value":"true"}],"links":[{"rel":"presentations","href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations","prompt":"presentations"}]}]}}

Note the following in this example:

-

The

collectionObject encapsulates the Speaker data. -

The

itemsArray contains all objects in the Speaker collection. Because we queried by ID, there’s only one Object in the collection. -

The

dataArray contains name/value pairs for each data element that comprises a Speaker. -

The

linksArray provides link relationships to resources related to the speaker. Each link is composed of:

Collection+JSON also provides the ability to read, write, and query items in a collection, but a full discussion of Collection+JSON is outside the scope of this book. Visit http://amundsen.com/media-types/collection/examples/ for examples, and http://amundsen.com/media-types/tutorials/collection/tutorial-01.html for a tutorial.

Collection+JSON does a nice job of providing link relations, but it completely changes the structure

of the Speaker data by converting it to key/value pairs inside the data Array.

json:api

json:api was developed in 2013 and provides conventions for standardizing the format of JSON

requests/responses to/from an API. Although json:api’s main focus is on API request/response data, it also

includes Hypermedia. You can find more information at the main json:api site and on GitHub. The

json:api media type is application/vnd.api+json.

A valid json:api document must have one of the following elements at the top level:

data-

The data representation for the resource. This contains resource Objects, each of which must have a

type(specifies the data type) andid(unique resource ID) field. errors-

An Array of error Objects that shows an error code and message for each error encountered by the API.

meta-

Contains nonstandard metadata (e.g., copyright and authors, etc.).

Optional top-level elements include the following:

links-

An Object that holds link relations (hyperlinks) to resources related to the primary resource.

included-

An Array of embedded resource Objects that are related to the primary resource.

Example 8-6 shows a list of Speakers in json:api format based on the following HTTP Request:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers Accept: application/vnd.api+json

Example 8-6. data/speakers-jsonapi-links.json

{"links":{"self":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers","next":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers?limit=25&offset=25"},"data":[{"type":"speakers","id":"123456","attributes":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true}},{"type":"speakers","id":"223456","attributes":{"firstName":"Ester","lastName":"Clements","email":"ester.clements@myconference.com","tags":["REST","Ruby on Rails","APIs"],"age":29,"registered":true}},...]}

This example works as follows:

-

The

linksArray provides link relationships to resources related to the speaker. In this case, each element contains the URI to the related resource. Note that there are no restrictions/qualifications on the link names, butselfis commonly understood as the current resource, andnextpaginate. -

The

dataArray contains a list of the resource objects, each of which has atype(e.g.,speakers) andidto meet the requirements of thejson:apiformat definition. Theattributesobject holds the key/value pairs that make up eachspeakerObject.

Example 8-7 shows how to embed all presentation Objects for a speaker with json:api:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.api+json

Example 8-7. data/speaker-jsonapi-embed-presentations.json

{"links":{"self":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456"},"data":[{"type":"speaker","id":"123456","attributes":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true}}],"included":[{"type":"presentations","id":"1123","speakerId":"123456","title":"Enterprise Node","abstract":"Many developers just see Node as a way to build web APIs or ...","audience":["Architects","Developers"]},{"type":"presentations","id":"2123","speakerId":"123456","title":"How to Design and Build Great APIs","abstract":"Companies now leverage APIs as part of their online ...","audience":["Managers","Architects","Developers"]}]}

In this example, the included Array (part of the json:api specification) specifies

the embedded presentations for the speaker. Although embedding resources reduces the number of API

calls, it introduces tight data coupling between resources because the speaker needs to know the format

and content of the presentation data.

Example 8-8 provides a better way to show relationships between resources with links:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.api+json

Example 8-8. data/speaker-jsonapi-link-presentations.json

{"links":{"self":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456","presentations":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations"},"data":[{"type":"speaker","id":"123456","attributes":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true}}]}

In this example, the links Array shows that the speaker has presentations and provides a URI,

but the speaker resource (and API) doesn’t know about the data in the presentation resource. Plus,

there’s less data for the Consumer to process. This loose coupling enables the presentation data to change

without impacting the Speakers API.

json:api has a rich feature set including standardized error messages, pagination, content

negotiation, and policies for Creating/Updating/Deleting resources. In the past, I’ve borrowed portions of

the json:api specification to create API style guides. Plus, there are excellent libraries for most platforms

that simplify working with json:api. The data Array and its resource Objects (which require a type

and id) alter the JSON data representation, but the rest of the Object remains the same. A full discussion

of json:api is outside the scope of this book; visit the JSON API page for examples, and the full specification.

HAL

Hypertext Application Language (HAL) became an IETF standard in 2012.

It was designed as a way to link resources using hyperlinks, and works with either JSON or XML.

You can find more information at the main HAL site and on

GitHub.

The HAL media types are application/hal+json and application/hal+xml.

HAL’s format is simple, readable, and doesn’t alter the original data representation. HAL is a popular media type, and is based on the following:

- Resource Objects

-

Resources contain links (contained in a

_linksObject), other resources, and embedded resources (e.g., an Order contains items) contained in an_embeddedObject. - Links

-

Links provide target URIs that lead to other external resources.

Both the _embedded and _links objects are optional, but one must be present

as the top-level object so that you have a valid HAL document.

Example 8-9 shows the Speaker data in HAL format based on the following HTTP Request:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.hal+json

Example 8-9. data/speaker-hal.json

{"_links":{"self":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456"},"presentations":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations"}},"id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true}

This example works as follows:

-

The

_linksobject contains link relations, each of which shows the semantic meaning of a link. -

The link relations are as follows:

-

selfis a link to the currentspeakerresource (self). -

presentationsare the presentations that thisspeakerwill deliver. In this case, thepresentationsObject describes the relationship between the current resource and thehttp://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentationshyperlink (through thehrefkey). -

Note that

nextandfindare not HAL keywords. HAL allows you to have custom names for link objects.

-

Let’s make the example more interesting by getting a list of speakers, as shown in Example 8-10.

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers Accept: application/vnd.hal+json

Example 8-10. data/speakers-hal-links.json

{"_links":{"self":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers"},"next":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers?limit=25&offset=25"},"find":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers{?id}","templated":true}},"speakers":[{"id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true},{"id":"223456","firstName":"Ester","lastName":"Clements","email":"ester.clements@myconference.com","tags":["REST","Ruby on Rails","APIs"],"age":29,"registered":true},...]}

This example works as follows:

-

In addition to

self, here are the following link relations:-

nextindicates the next set ofspeakerresources. In other words, this is a way to provide pagination for an API. In this case, thelimitparameter indicates that 25speakerObjects will be returned in each API call. Theoffsetparameter indicates that we’re at the 26th Object in the list. This convention is similar to Facebook’s pagination style. -

findprovides a hyperlink to find an individualspeakerwith a templated link, where{?id}indicates to the caller that they can find thespeakerbyidin the URI. Thetemplatedkey indicates that this is a templated link.

-

-

The JSON data representation remains unchanged.

Returning to our first example, let’s embed all presentation Objects for a speaker, as shown in Example 8-11:

GET http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456 Accept: application/vnd.hal+json

Example 8-11. /data/speaker-hal-embed-presentations.json

{"_links":{"self":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456"},"presentations":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations"}},"_embedded":{"presentations":[{"_links":{"self":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations/1123"}},"id":"1123","title":"Enterprise Node","abstract":"Many developers just see Node as a way to build web APIs ...","audience":["Architects","Developers"]},{"_links":{"self":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers/123456/presentations/2123"}},"id":"2123","title":"How to Design and Build Great APIs","abstract":"Companies now leverage APIs as part of their online ...","audience":["Managers","Architects","Developers"]}]},"id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true}

In this example, instead of the presentations link relation, we’re using the

_embedded Object to embed the presentation Objects for a speaker. Each presentation Object in turn has a _links Object for related resources.

At first glance, embedding related resources looks reasonable, but I prefer link relations instead for the following reasons:

-

Embedded resources increase the size of the payload.

-

The

_embeddedObject alters the data representation. -

It couples the Speakers and Presentation APIs. The Speakers API now has to know about the data structure of the presentations. With a simple

presentationslink relation, the Speakers API knows only that there is a related API.

HAL (minus the embedded resources) is lightweight and provides links to other resources without altering the data representation.

Conclusions on Hypermedia

Here’s the bottom line on Hypermedia: keep it simple. Maintain the original structure of the resource representation. Provide solid documentation for your API as part of the design process, and much of the need for Hypermedia (actions, documentation, data typing) is already taken care of. For me, the most useful parts of Hypermedia are the links to other resources. Proponents of full Hypermedia may vehemently disagree (and that’s OK), but here’s my rebuttal:

-

If your API is difficult to understand, people won’t want to use it.

-

The original JSON representation is the most important thing. Don’t alter the structure of the resource just for the sake of adhering to a Hypermedia format.

With these considerations in mind, I choose a minimal HAL structure (links only, without embedded resources) as my Hypermedia format. With these caveats, HAL is excellent because it

-

Is the simplest possible thing that can work

-

Is a standard

-

Enjoys wide community support

-

Has solid cross-platform libraries

-

Doesn’t alter my JSON data representation

-

Doesn’t impose requirements for data semantics and operations

-

Does just what I want, and not a bit more

json:api (with links rather than embedded resources) is my second choice for Hypermedia because it

standardizes JSON requests/responses in addition to providing Hypermedia capabilities, and still respects

the integrity and intent of the original JSON data representation. Of the Hypermedia formats that alter the

JSON data representation, json:api appears to have the least impact. Because of its wide

cross-platform support, you can reduce the formatting work by leveraging a json:api library for your

programming language (this shortens and simplifies development). json:api deserves strong consideration

if you need more than just Hypermedia, and you want to standardize JSON requests/responses across all the

APIs in your enterprise (but API design is outside the scope of this book).

JSON-LD (without HYDRA) is my third favorite Hypermedia format because it’s simple and doesn’t change the JSON data representation. Although the data semantics are not hard to add to an existing API, I don’t see a need for this, because good API documentation combined with JSON Schema does a better job of defining the meaning and structure of the data.

Recommendations for Working with Hypermedia

You may disagree with my opinion on Hypermedia, but imagine you’re the architect or team lead and you’re asking your team to use all aspects of Hypermedia to develop an API. Would your developers see Hypermedia as being useful or burdensome? Harkening back to the original days of eXtreme Programming (XP), do the simplest thing that could possibly work. Use the right tools and techniques for the job, and take the following approach:

-

Document your API properly with OpenApi/Swagger or RAML.

-

Define your data constructs by using JSON Schema.

-

Choose HAL,

json:api, or JSON-LD as your Hypermedia format, and start out with simple links to related resources. -

Evaluate how well the development process is going:

-

What’s the team velocity?

-

How testable is the API?

-

-

Ask your API Consumers for feedback. Can they

-

Easily understand the data representation?

-

Read and consume the data?

-

-

Iterate and evaluate early and often.

Then, see whether you need to add in the operations and data definitions; you probably won’t.

Practical Issues with Hypermedia

Here are some things to think about when you consider adding Hypermedia to an API:

-

Hypermedia is not well understood in the community. When I speak on this topic, many developers haven’t heard of it, know little about it, or don’t know what it’s used for. Some education is required even with the simplest Hypermedia format.

-

Lack of standardization. We’ve covered five of the leading formats, but there are more. Only two (HAL and JSON-LD) in this chapter are backed by a standards body. So there’s no consensus in the community.

-

Hypermedia (regardless of the format) requires additional serialization/deserialization by both the API Producer and Consumer. So, be sure to choose a widely used Hypermedia format that provides cross-platform library support. This makes life easier for developers. We’ll cover this in the next section when we test with HAL.

Testing with HAL in the Speakers API

As in previous chapters, we’ll test against a Stub API (that provides a JSON response) that doesn’t require us to write any code.

Test Data

To create the stub, we’ll use the Speaker data from earlier chapters as our test data, which is available

on GitHub,

and deploy it as a RESTful API. Again, we’ll leverage the json-server Node.js module to serve up the

speakers.json file as a Web API. If you need to install json-server, refer to “Install npm Modules” in Appendix A.

Here’s how to run json-server on port 5000 from your local machine:

cd chapter-8/data json-server -p 5000 ./speakers-hal-server-next-rel.json

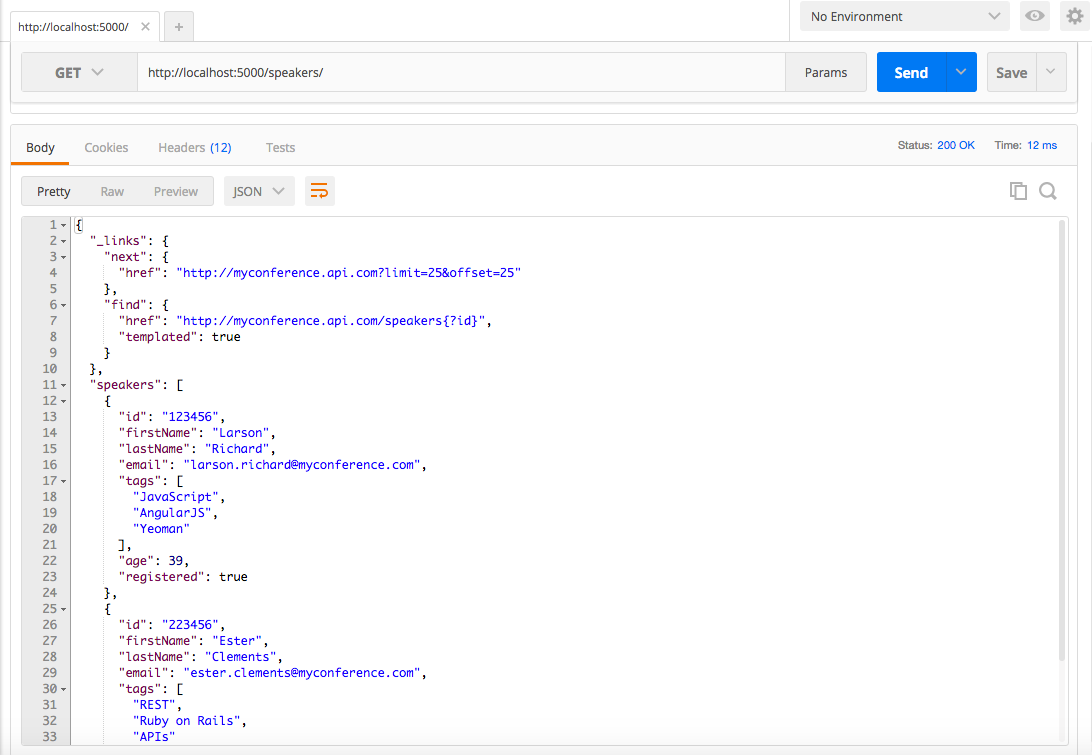

Visit http://localhost:5000/speakers in Postman (which we used in earlier

chapters), select GET as the HTTP verb, and click the Send button. You should see all the speakers from

our Stub API, as shown in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Speakers data in HAL format served by json-server and viewed with Postman

This URI is also viewable from your browser.

Note that we had to massage the Speaker data to work with json-server for this example. Example 8-12 shows the

updated structure that works with HAL.

Example 8-12. data/speakers-hal-server-next-rel.json

{"speakers":{"_links":{"self":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers"},"next":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com?limit=25&offset=25"},"find":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers{?id}","templated":true}},"speakers":[{"id":"123456","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larson.richard@myconference.com","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"age":39,"registered":true},{"id":"223456","firstName":"Ester","lastName":"Clements","email":"ester.clements@myconference.com","tags":["REST","Ruby on Rails","APIs"],"age":29,"registered":true}]}}

In this example, the outer speakers Object is needed so that json-server will serve up the file

with the proper URI: http://localhost:5000/speakers. The rest of the data (links Object and

speakers Array) remain the same.

HAL Unit Test

Now that we have the API in place, let’s create a Unit Test. We will continue to leverage Mocha/Chai (within

Node.js), just as we saw in previous chapters. Before going further, be sure to set up your test

environment. If you haven’t installed Node.js yet, then refer to Appendix A, and

install Node.js (see “Install Node.js” and “Install npm Modules”). If you want to follow along

with the Node.js project provided in the code examples, cd to chapter-8/myconference and do the

following to install all dependencies for the project:

npm install

If you’d like to set up the Node.js project yourself, follow the instructions in the book’s GitHub repository.

Here are the npm modules in our Unit Test:

- Unirest

-

We’ve used this in previous chapters to invoke RESTful APIs.

- halfred

-

A HAL parser available at https://www.npmjs.com/package/halfred. The corresponding GitHub repository can be found at https://github.com/basti1302/halfred.

The following Unit Test shows how to validate the HAL response from the (Stub) Speakers API.

Example 8-13. speakers-hal-test/test/hal-spec.js

'use strict';varexpect=require('chai').expect;varunirest=require('unirest');varhalfred=require('halfred');describe('speakers-hal',function(){varreq;beforeEach(function(){halfred.enableValidation();req=unirest.get('http://localhost:5000/speakers').header('Accept','application/json');});it('should return a 200 response',function(done){req.end(function(res){expect(res.statusCode).to.eql(200);expect(res.headers['content-type']).to.eql('application/json; charset=utf-8');done();});});it('should return a valid HAL response validated by halfred',function(done){req.end(function(res){varspeakersHALResponse=res.body;varresource=halfred.parse(speakersHALResponse);varspeakers=resource.speakers;varspeaker1=null;console.log('\nValidation Issues: ');console.log(resource.validationIssues());expect(resource.validationIssues()).to.be.empty;console.log(resource);expect(speakers).to.not.be.null;expect(speakers).to.not.be.empty;speaker1=speakers[0];expect(speaker1.firstName).to.not.be.null;expect(speaker1.firstName).to.eql('Larson');done();});});});

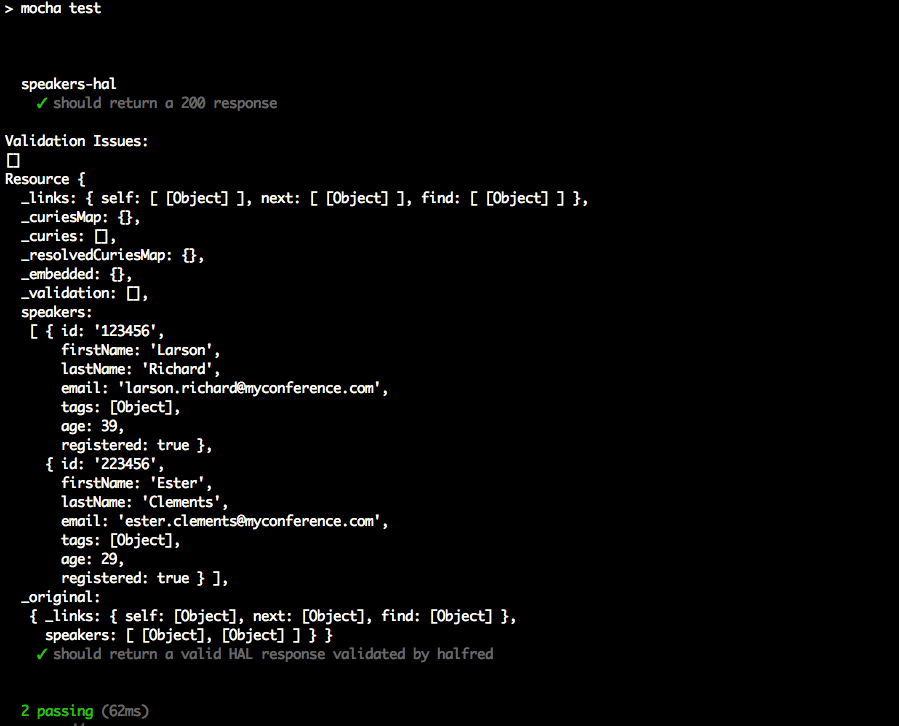

This Unit Test runs as follows:

-

beforeEach(function()runs before each test, and does the following: -

The

'should return a 200 response'test ensures that the Stub API has a successful HTTP response. -

The

'should return a valid HAL response validated by halfred'test is the main test, and does the following:-

Invokes

halfred.parse()to parse the HAL response from the Stub API. This call returns ahalfredResponseobject that contains the HAL links and the remaining JSON payload. Please see thehalfreddocumentation for more information -

Uses

chaito check for validation errors in the HAL response by testingresource.validationIssues(). We’ll see this call in action when we test with invalid data in our second run of the Unit Test that follows -

Uses

chaito ensure that theResponseobject still contains the originalspeakersArray in the payload

-

When you run the Unit Test with npm test, it will pass because the Stub API produces valid HAL data. You

should see the following:

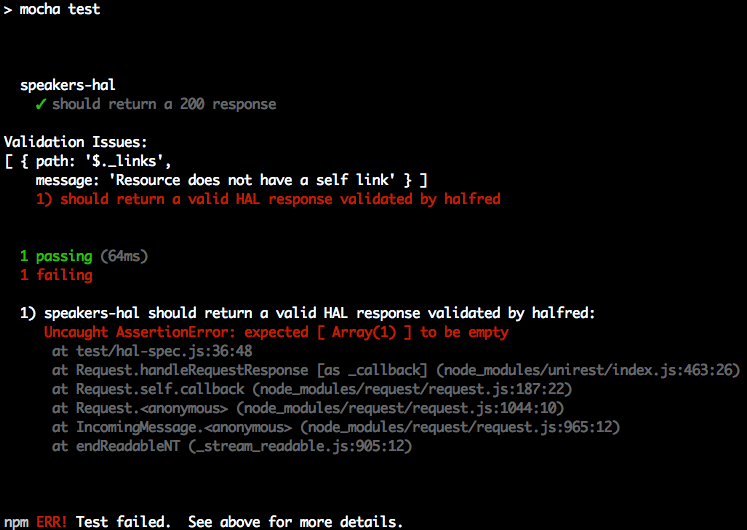

Now that we’ve shown how to validate HAL data, we’ll change the data served up by the Stub API so that it

responds with invalid HAL data. Let’s remove the link to self in the _links object as shown in Example 8-14.

Example 8-14. data/speakers-hal-server-next-rel-invalid.json

{"speakers":{"_links":{"next":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com?limit=25&offset=25"},"find":{"href":"http://myconference.api.com/speakers{?id}","templated":true}},...}}

Remember that the HAL specification requires the _links object to contain a reference to self.

Restart json-server with the invalid HAL data as follows:

cd chapter-8/data json-server -p 5000 ./speakers-hal-server-next-rel-invalid.json

Rerun the test, and you should see that halfred catches the HAL validation issue and that the test now

fails:

Server-Side HAL

We’ve shown how to use HAL from the client side with Unit Tests, but the server-side was deployed as a Stub

(using json-server and a JSON file that follows the HAL specification). We have limited server-side coverage

throughout this book to keep the focus on JSON. But here are some server-side libraries that will enable

your RESTful APIs to render HAL-based responses:

- Java

-

Spring HATEOS provides HAL support for Spring-based RESTful APIs in Java. You can find a good tutorial in the Spring documentation.

- Ruby on Rails

-

The

roargem provides HAL support for Ruby on Rails. - JavaScript/NodeJS

-

express-haladds HAL to Express-based NodeJS RESTful APIs.

Regardless of your development platform and which Hypermedia format you choose, be sure to do a spike implementation to test a library before committing to it as a solution. It’s important to ensure that the library is easy to use and that it doesn’t get in the way.

What’s Next?

Now that we’ve shown how JSON works with Hypermedia, we’ll move on to Chapter 9 to show how JSON works with MongoDB.