Chapter 5. JSON Schema

We’ve covered the basics of JSON using our core platforms (JavaScript, Ruby on Rails, and Java), and now it’s time to wade in deeper. In this chapter, we’ll show how to leverage JSON Schema to define the structure and format of JSON documents exchanged between applications:

-

JSON Schema overview

-

Core JSON Schema—basics and tooling

-

How to design and test an API with JSON Schema

In our examples, we’ll design an API with JSON Schema after we progressively walk through the concepts of JSON Schema. As noted in the preface, from now on we will write all our examples in Node.js to keep the size of the chapters to a minimum. But know that the other platforms work well with JSON Schema. If you haven’t installed Node.js already, now would be a great time. Follow the instructions in Appendix A.

JSON Schema Overview

Many architects and developers are unfamiliar with JSON Schemas. Before going into details, it’s important to know what a JSON Schema is, how it helps, and why/when to use it. Along the way, we’ll look at the JSON Schema Specification and show a simple example.

Syntactic Versus Semantic Validation

The difference is in the type of validation. When you validate a JSON document without a Schema, you’re validating only the syntax of the document. This type of validation guarantees only that the document is well-formed (i.e., matching braces, double quotes for keys, and so forth). This type of validation is known as syntactic validation, and we’ve done this before with tools such as JSONLint, and the JSON parsers for each platform.

How does a JSON Schema help?

Syntactic validation is a good start, but at times you need to validate at a deeper level by using semantic validation. What if you have the following situations:

-

You (as an API Consumer) need to ensure that a JSON response from an API contains a valid

Speaker, or a list ofOrders? -

You (as an API Producer) need to check incoming JSON to make sure that the Consumer can send you only the fields you’re expecting?

-

You need to check the format of a phone number, a date/time, a postal code, an email address, or a credit card number?

This is where JSON Schema shines, and this type of validation is known as semantic validation. In this case, you’re validating the meaning of the data, not just the syntax. JSON Schema is also great for API Design because it helps define the interface, and we’ll cover that later in this chapter.

A Simple Example

Before talking too much more about JSON Schema, let’s look at Example 5-1 to get a feel for the syntax.

Example 5-1. ex-1-basic-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"}}}

This Schema specifies that a document can have three fields (email, firstName, and lastName), where

each one is a string. We’ll gloss over Schema syntax for now, but don’t worry—we’ll cover it soon.

Example 5-2 shows a sample JSON instance document that corresponds to the preceding Schema.

Example 5-2. ex-1-basic.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

JSON Schema on the Web

The json-schema.org site, shown in Figure 5-1, is the starting place to go for all things related to JSON Schema, including copious documentation and examples.

Figure 5-1. json-schema.org site

From here, you can find example Schemas, great validation libraries for most major platforms, along with the JSON Schema Standard GitHub repository (where the standard is maintained). The GitHub repository is shown in Figure 5-2.

Figure 5-2. json-schema GitHub repository

Here you can track updates, issues, and progress with the JSON Schema standard (more on that later in “The Current State of the JSON Schema Standard”).

Why JSON Schema?

JSON Schema provides the ability to validate the content and semantics of a document, and here are some real-world use cases:

- Security

-

The Open Web Application Project (OWASP) Web Service Security Cheat Sheet recommends that Web Services should validate their payloads by using a Schema. Granted, they still talk about XML Schema, but their concern is still applicable to JSON. OWASP calls for validation of field lengths (min/max) and fixed format fields (e.g., phone number or postal code) to help secure a service.

- Message Design

-

JSON isn’t just for APIs anymore. Many enterprises use JSON as the preferred format to send payloads over messaging systems such as Apache Kafka (we’ll cover this in more detail in Chapter 10). The message Producer and Consumer are completely decoupled in this style of architecture, and JSON Schema can help ensure that the reader receives messages in a format that it’s expecting.

- API Design

-

JSON is a first-class citizen in API Design. JSON Schema helps define an API’s contract by specifying the format, content, and structure of a document.

- Prototyping

-

With the structure and rigor of JSON Schema, this may seem counterintuitive. We’ll show a streamlined prototyping workflow with JSON Schema and related tooling when we design an API later in this chapter.

My Journey with JSON Schema

As mentioned in the Preface, as of 2009 I wasn’t sure that JSON was ready for the enterprise. I loved its speed and simplicity, but I didn’t see a way to guarantee the structure and content of JSON documents between applications. But when I learned about JSON Schema in 2010, I changed my position and came to accept JSON as a viable enterprise-class data format.

The Current State of the JSON Schema Standard

The JSON Schema Specification is at implementation draft 4 (v0.4), and the next implementation draft 6 (v0.6) is on the way. Draft 5 (v0.5) was published late last year as a working draft to capture work in progress and was not an implementation draft. But don’t let the 0.x version number concern you. As you’ll see in our examples, JSON Schema is robust, provides solid validation capabilities today, and there is a wide variety of working JSON Schema libraries for every major programming platform. You can find more details in the JSON Schema draft 4 spec.

JSON Schema and XML Schema

JSON Schema fills the same role with JSON as XML Schema did with XML documents, but with the following differences:

-

A JSON document does not reference a JSON Schema. It’s up to an application to validate a JSON document against a Schema.

-

JSON Schemas have no namespace.

-

JSON Schema files have a .json extension.

Core JSON Schema—Basics and Tooling

Now that you have an overview of JSON Schema, it’s time to go deeper. JSON Schema is powerful, but it can be tedious, and we’ll show some tools to make it easier. We’ll then cover basic data types and core keywords that provide a foundation for working with JSON Schema on real-world projects.

JSON Schema Workflow and Tooling

JSON Schema syntax can be a bit daunting, but developers don’t have to code everything by hand. Several excellent tools can make life much easier.

JSON Editor Online

We’ve already covered JSON Editor Online in Chapter 1, but it’s worth another brief mention. Start modeling a JSON document with this tool to get a feel for the data. Use this tool to generate the JSON document and avoid all the typing. When you’re finished, save the JSON document to the clipboard.

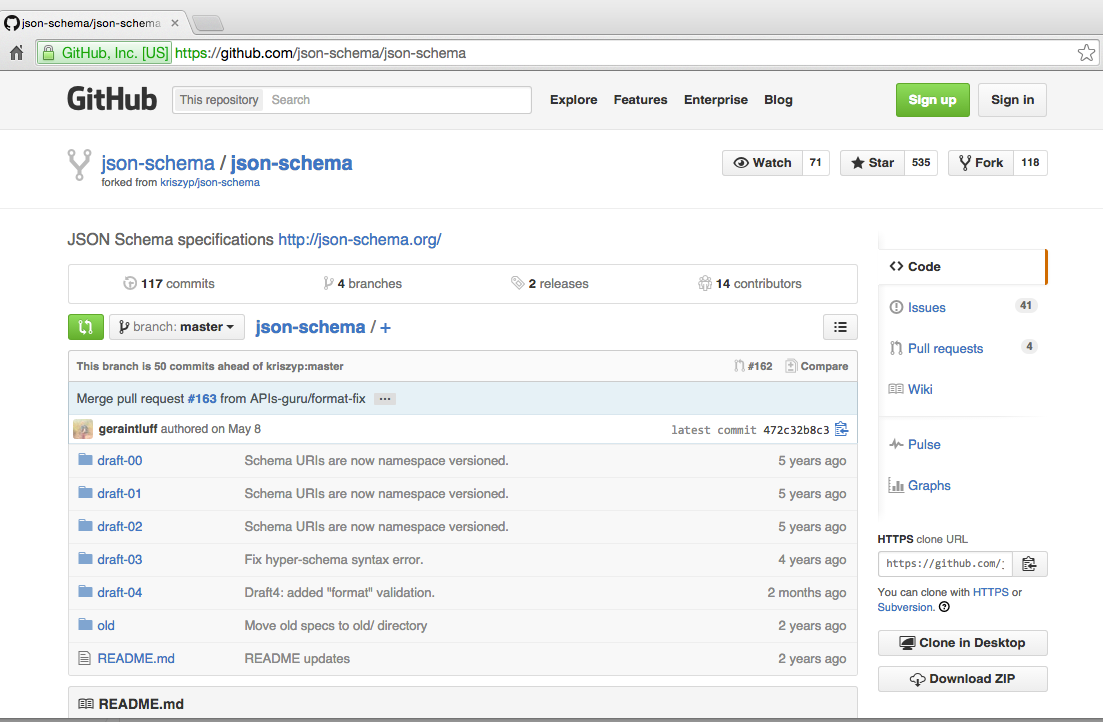

JSONSchema.net

Once you have your core concept, the JSONSchema.net application generates a JSON Schema based on the JSON document that was created earlier with JSON Editor Online (see Figure 5-3). The JSONSchema.net application alone will save you 80 percent of the typing required to create a Schema. I always start my Schema work with this application and then make incremental upgrades.

Here are the steps to generate the initial Schema with JSONSchema.net:

-

Paste in a JSON document on the left side.

-

Start with the default settings, and make the following changes:

-

Turn off “Use absolute IDs.”

-

Turn off “Allow additional properties.”

-

Turn off “Allow additional items.”

-

-

Click the Generate Schema button.

-

Copy the generated Schema to your clipboard.

Figure 5-3. Speakers Schema on JSONSchema.net

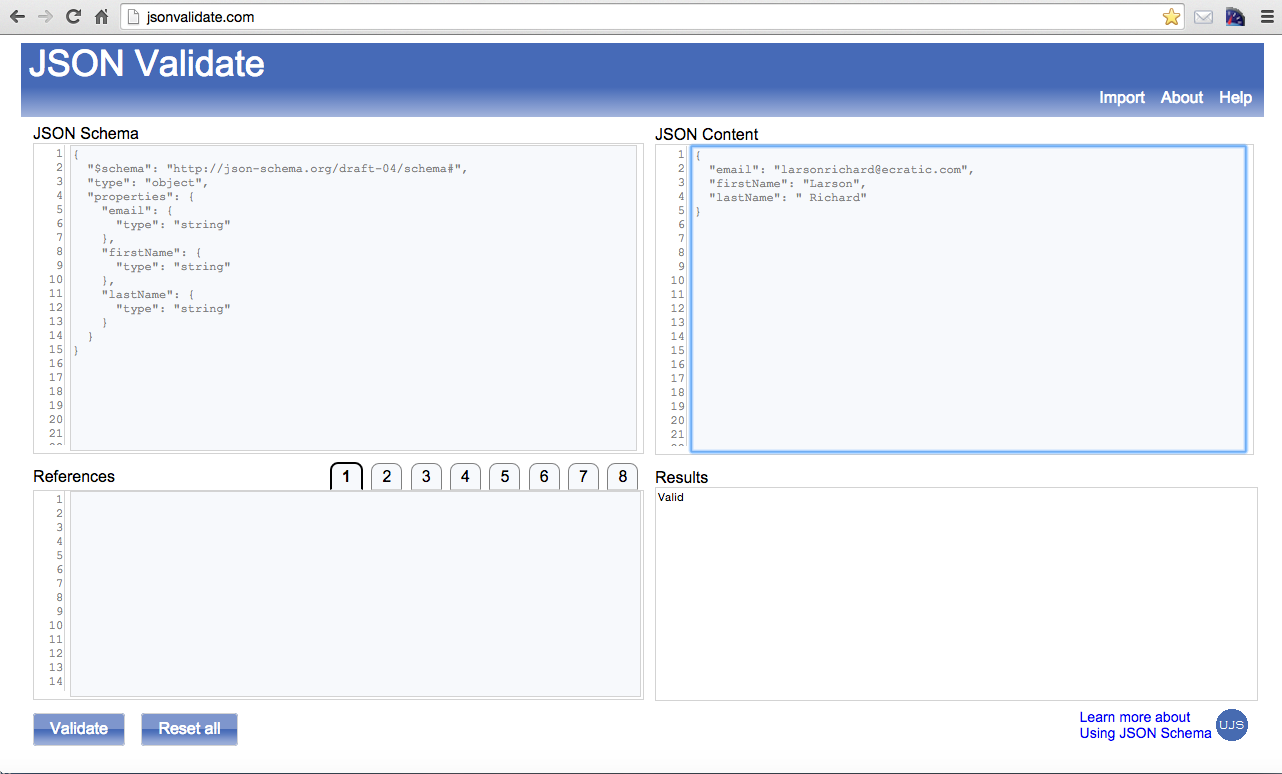

JSON Validate

After you’ve created a JSON Schema, the JSON Validate application validates a JSON document against that Schema, as shown in Figure 5-4.

Figure 5-4. Valid Speakers Schema on jsonvalidate.com

To validate the JSON document against the Schema, do the following:

-

Paste the JSON document and Schema into the JSON Validate application.

-

Remove all

idfields from the Schema because they’re not needed. -

Click the Validate button to validate the document.

NPM modules on the CLI: validate and jsonlint

But sometimes you don’t have good internet connectivity, so it’s great to have tools that run

locally. Plus, if you have sensitive data, it’s safer to run examples on your machine from the command-line interface (CLI). The validate module is the Node.js equivalent of the jsonvalidate.com site. To install and

run it, follow the instructions in Appendix A (see “Install npm Modules”).

Both jsonvalidate.com and validate are part of the Using JSON Schema site (a great Schema resource),

which can be found on GitHub.

You’ve already seen the JSONLint site in Chapter 1, but you can also use JSONLint from the command line by

using the jsonlint Node.js module. To install and run it, follow the instructions in Appendix A (see “Install npm Modules”).

I’ve used jsonlint only for syntactic validation, but if you run jsonlint --help from the command line,

you’ll notice that it can also do semantic validation with a Schema. For more information, see

the jsonlint documentation on GitHub.

We’ll leverage validate from the command line to work through the examples.

Core Keywords

Here are the core keywords in any JSON Schema:

$schema-

Specifies the JSON Schema (spec) version. For example,

“$schema": "http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#"specifies that the schema conforms to version 0.4, whilehttp://json-schema.org/schema#tells a JSON Validator to use the current/latest version of the specification (which is 0.4 as of this writing). Using the latter of these two options is risky because some JSON Validators default to a previous version, so an earlier version (and not the current/latest) version will be used. To play it safe, always specify the version so that you (and the JSON Validator) are sure about the version you’re using. type-

Specifies the data type for a field. For example:

"type": "string". properties-

Specifies the fields for an object. It contains

typeinformation.

Basic Types

The document in Example 5-3 contains the basic JSON types (for example, string, number, boolean) that you’ve

seen before.

Example 5-3. ex-2-basic-types.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","age":39,"postedSlides":true,"rating":4.1}

JSON Schema uses the same basic data types as the Core JSON data types from Chapter 1 (string,

number, array, object, boolean, null), but adds an integer type that specifies whole numbers.

The number type still allows both whole and floating-point numbers.

The JSON Schema in Example 5-4 describes the structure of the preceding document.

Example 5-4. ex-2-basic-types-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"age":{"type":"integer"},"postedSlides":{"type":"boolean"},"rating":{"type":"number"}}}

In this example, note the following:

-

The

$schemafield indicates that JSON Schema v0.4 rules will be used for validating the document. -

The first

typefield mentioned indicates that there is anObjectat the root level of the JSON document that contains all the fields in the document. -

email,firstName,lastNameare of typestring -

ageis aninteger. Although JSON itself has only anumbertype, JSON Schema provides the finer-grainedintegertype.postedSlidesis aboolean.ratingis anumber, which allows for floating-point values.

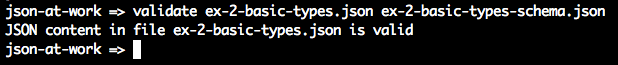

Run the preceding example using validate, and you’ll see that the document is valid for this Schema.

Although the preceding Schema is a decent start, it doesn’t go far enough. Let’s try the following changes to the JSON document that we want to validate:

-

Add an extra field (e.g.,

company). -

Remove one of the expected fields (e.g.,

postedSlides).

Example 5-5 shows our modified JSON document.

Example 5-5. ex-2-basic-types-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","age":39,"rating":4.1,"company":"None"}

Right now there’s nothing to prevent you from invalidating the document, as you’ll see in the following run:

Basic types validation

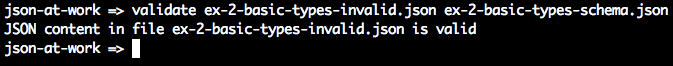

At this point, you might be thinking that JSON Schema isn’t useful because it’s not validating as expected. But we can make the validation process function as expected by adding simple constraints. First, to prevent extra fields, use the code in Example 5-6.

Example 5-6. ex-3-basic-types-no-addl-props-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"postedSlides":{"type":"boolean"},"rating":{"type":"number"}},"additionalProperties":false}

In this example, setting additionalProperties to false disallows any extra fields in the document root Object. Copy the previous JSON document (ex-2-basic-types-invalid.json) to a new version

(ex-3-basic-types-no-addl-props-invalid.json) and try validating against the preceding Schema. You should now

see the following:

This is getting better, but it still isn’t what we want because there’s no guarantee that all the expected fields will be in the document. To reach a core level of semantic validation, we need to ensure that all required fields are present, as shown in Example 5-7.

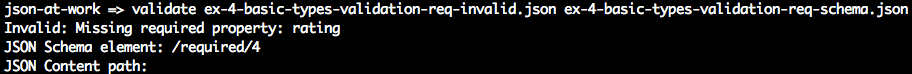

Example 5-7. ex-4-basic-types-validation-req-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"postedSlides":{"type":"boolean"},"rating":{"type":"number"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName","postedSlides","rating"]}

In this example, the required Array specifies the fields that are required, so these fields must

be present for a document to be considered valid. Note that a field is considered optional if not

mentioned in the required Array.

Example 5-8 shows the modified JSON document (without the required rating field, plus an unexpected age field) to validate.

Example 5-8. ex-4-basic-types-validation-req-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","postedSlides":true,"age":39}

When running this example from the command line, the document is now considered invalid:

We finally have what we want:

-

No extra fields are allowed.

-

All fields are required.

Now that we have basic semantic validation in place, let’s move on to validating number fields in JSON documents.

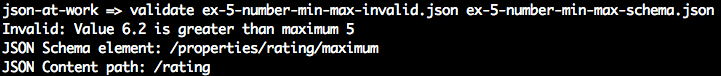

Numbers

As you’ll recall, a JSON Schema number type can be a floating-point or whole number. The Schema in Example 5-9

validates the average rating for a speaker’s conference presentation, where the range varies from 1.0

(poor) to 5.0 (excellent).

Example 5-9. ex-5-number-min-max-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"rating":{"type":"number","minimum":1.0,"maximum":5.0}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["rating"]}

Example 5-10 is a valid JSON document because the rating is within the 1.0–5.0 range.

Example 5-10. ex-5-number-min-max.json

{"rating":4.99}

Example 5-11 is an invalid document, where the rating is greater than 5.0.

Example 5-11. ex-5-number-min-max-invalid.json

{"rating":6.2}

Run this from the command line, and you’ll see that the preceding document is invalid:

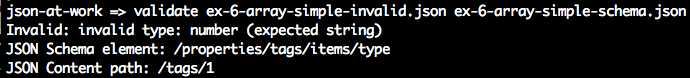

Arrays

JSON Schema provides the ability to validate Arrays. Arrays can hold any of the JSON Schema basic types

(string, number, array, object, boolean, null). The Schema in Example 5-12 validates the

tags field, which is an Array of type string.

Example 5-12. ex-6-array-simple-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"tags":{"type":"array","items":{"type":"string"}}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["tags"]}

Example 5-13 is a valid JSON document for the preceding Schema.

Example 5-13. ex-6-array-simple.json

{"tags":["fred"]}

The document in Example 5-14 is not valid because we’ve added an integer to the tags Array.

Example 5-14. ex-6-array-simple-invalid.json

{"tags":["fred",1]}

Run the preceding example to verify that the document is invalid:

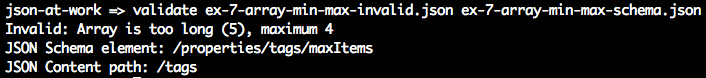

JSON Schema provides the ability to specify the minimum (minItems) and maximum (maxItems) number of items

in an Array. The Schema in Example 5-15 allows for two to four items in the tags Array.

Example 5-15. ex-7-array-min-max-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"tags":{"type":"array","minItems":2,"maxItems":4,"items":{"type":"string"}}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["tags"]}

The JSON document conforms in Example 5-16 to the preceding Schema.

Example 5-16. ex-7-array-min-max.json

{"tags":["fred","a"]}

The document in Example 5-17 is invalid because the tags Array has five items.

Example 5-17. ex-7-array-min-max-invalid.json

{"tags":["fred","a","x","betty","alpha"]}

Run the preceding example to verify:

Enumerated Values

The enum keyword constrains a field’s value to a fixed set of unique values, specified in an Array.

The Schema in Example 5-18 limits the set of allowable values in the tags Array to one of "Open Source",

"Java", "JavaScript", "JSON", or "REST".

Example 5-18. ex-8-array-enum-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"tags":{"type":"array","minItems":2,"maxItems":4,"items":{"enum":["Open Source","Java","JavaScript","JSON","REST"]}}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["tags"]}

The document in Example 5-19 is valid based on the preceding Schema.

Example 5-19. ex-8-array-enum.json

{"tags":["Java","REST"]}

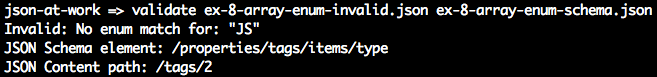

This document in Example 5-20 is not valid because the value "JS" is not one of the values in the Schema’s enum.

Example 5-20. ex-8-array-enum-invalid.json

{"tags":["Java","REST","JS"]}

Run this example to show that the document is invalid:

Objects

JSON Schema enables you to specify an object. This is the heart of semantic validation because it

enables you to validate Objects exchanged between applications. With this capability, both an API’s

Consumer and Producer can agree on the structure and content of important business concepts such as a

person or order. The Schema in Example 5-21 specifies the content of a speaker Object.

Example 5-21. ex-9-named-object-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"speaker":{"type":"object","properties":{"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"email":{"type":"string"},"postedSlides":{"type":"boolean"},"rating":{"type":"number"},"tags":{"type":"array","items":{"type":"string"}}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["firstName","lastName","email","postedSlides","rating","tags"]}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["speaker"]}

This Schema is similar to previous examples, with the addition of a top-level speaker object nested

inside the root object.

The JSON document in Example 5-22 is valid against the preceding Schema.

Example 5-22. ex-9-named-object.json

{"speaker":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","postedSlides":true,"rating":4.1,"tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"]}}

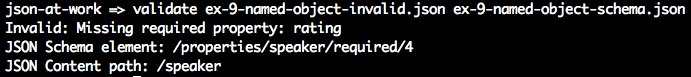

The document in Example 5-23 is invalid because the speaker Object is missing the required rating field.

Example 5-23. ex-9-named-object-invalid.json

{"speaker":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","postedSlides":true,"tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"]}}

Run the example on the command line to ensure that the preceding document is invalid:

We’ve now covered the most important basic types, and we’ll move on to more-complex schemas.

Pattern Properties

JSON Schema provides the ability to specify repeating fields (with similar names) through pattern

properties (with the patternProperties keyword) based on Regular Expressions. Example 5-24

defines the fields in an address.

Example 5-24. ex-10-pattern-properties-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"city":{"type":"string"},"state":{"type":"string"},"zip":{"type":"string"},"country":{"type":"string"}},"patternProperties":{"^line[1-3]$":{"type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["city","state","zip","country","line1"]}

In this example, the ^line[1-3]$ Regular Expression allows for the following address fields in a

corresponding JSON document: line1, line2, and line3. Here’s how to interpret this Regular

Expression:

-

^represents the beginning of the string. -

linetranslates to the literal string"line". -

[1-3]allows for a single integer between 1 and 3. -

$indicates the end of the string.

Note that only line1 is required, and the others are optional.

The document in Example 5-25 will validate against the preceding Schema.

Example 5-25. ex-10-pattern-properties.json

{"line1":"555 Main Street","line2":"#2","city":"Denver","state":"CO","zip":"80231","country":"USA"}

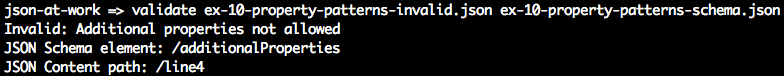

Example 5-26 is invalid because it has a line4 field, which is out of range.

Example 5-26. ex-10-pattern-properties-invalid.json

{"line1":"555 Main Street","line4":"#2","city":"Denver","state":"CO","zip":"80231","country":"USA"}

Run this example to see that the preceding document is invalid:

Regular Expressions

JSON Schema also uses Regular Expressions to constrain field values.

The Schema in Example 5-27 limits the value of the email field to a standard email address format as specified in IETF RFC 2822.

Example 5-27. ex-11-regex-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName"]}

In this example, the Regular Expression specifies a valid email address. Here’s how to interpret this Regular Expression:

-

^represents the beginning of the string. -

[\\w|-|.]+ matches one-to-many instances of the following pattern:-

[\\w|-|.]matches a word character (a-zA-Z0-9_), a dash (-), or a dot(.).

-

-

@indicates the literal “@”. -

[\\w]+ matches one-to-many instances of the following pattern:-

[\\w]matches a word character (a-zA-Z0-9_).

-

-

\\.indicates the literal “.” -

[A-Za-z]{2,4}matches two to four occurrences of the following pattern:-

[A-Za-z]matches an alphabetic character.

-

-

$indicates the end of the string.

The double backslash (\\) is used by JSON Schema to denote special characters within regular expressions

because the single backslash (\) normally used in standard Regular Expressions won’t work in this

context. This is due to that fact the a single backslash is already used in core JSON document syntax to

escape special characters (e.g., \b for a backspace).

The following document in Example 5-28 is valid because the email address follows the pattern specified in the Schema.

Example 5-28. ex-11-regex.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

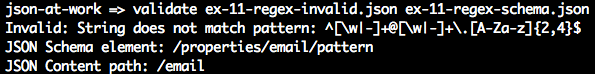

The document in Example 5-29 is invalid because the email address field is missing the trailing .com.

Example 5-29. ex-11-regex-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

Run the preceding example to prove that it’s invalid:

Going deeper with Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions can be daunting and complex at times. Although a full tutorial on Regular Expressions is far beyond the scope of this book, here are some resources to help you master Regular Expressions:

- Introducing Regular Expressions by Michael Fitzgerald (O’Reilly).

- Regular Expressions Cookbook, Second Edition by Jan Goyvaerts and Steven Levithan (O’Reilly).

- Mastering Regular Expressions, Third Edition by Jeffrey E. F. Friedl (O’Reilly).

- Regular Expressions 101—this is my favorite Regex site.

- RegExr

- Regular-Expressions.info

Dependent Properties

Dependent Properties introduce dependencies between fields in a Schema: one field depends on the

presence of the other. The dependencies keyword is an object that specifies the dependent relationship(s),

where field x maps to an array of fields that must be present if y is populated. In Example 5-30

tags must be present if favoriteTopics is provided in the corresponding JSON document (that is,

favoriteTopic depends on tags).

Example 5-30. ex-12-dependent-properties-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"tags":{"type":"array","items":{"type":"string"}},"favoriteTopic":{"type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName"],"dependencies":{"favoriteTopic":["tags"]}}

The JSON document in Example 5-31 is valid because the favoriteTopic is present, and the tags Array is

populated.

Example 5-31. ex-12-dependent-properties.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","tags":["JavaScript","AngularJS","Yeoman"],"favoriteTopic":"JavaScript"}

The JSON document in Example 5-32 is invalid because the favoriteTopic is present, but the tags Array is

missing.

Example 5-32. ex-12-dependent-properties-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","favoriteTopic":"JavaScript"}

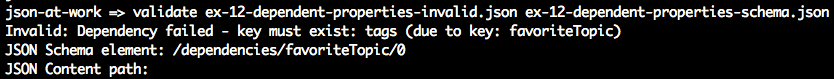

Run the preceding example, and you’ll see that the document is invalid:

Internal References

References provide the ability to reuse definitions/validation rules. Think of references as DRY (Do Not Repeat Yourself) for Schema. References can be either Internal (inside the same Schema) or External (in a separate/external Schema). We’ll start with Internal References.

In Example 5-33, you’ll notice that the Regular Expression for the email field has been replaced by a

$ref, a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) to the actual definition/validation rule for the email field:

-

#indicates that the definition exists locally within the Schema. -

/definitions/is the path to thedefinitionsobject in this Schema. Note that thedefinitionskeyword indicates the use of a reference. -

emailPatternis the path to theemailPatternspecification within thedefinitionsobject. -

JSON Schema leverages JSON Pointer (covered in Chapter 7) to specify URIs (e.g.,

#/definitions/emailPattern).

Example 5-33. ex-13-internal-ref-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"$ref":"#/definitions/emailPattern"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName"],"definitions":{"emailPattern":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"}}}

Other than the new definitions object, there’s nothing really that new here. We’ve just moved the

definition for email addresses to a common location that can be used throughout the Schema by multiple

fields.

Example 5-34 shows a JSON document that conforms to the preceding Schema.

Example 5-34. ex-13-internal-ref.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

Example 5-35 is invalid because email is missing the trailing .com.

Example 5-35. ex-13-internal-ref-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

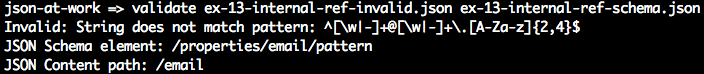

Validate this document from the command line, and you’ll see that it’s invalid:

External References

External References provide a way to specify validation rules in an external Schema file. In this case, Schema A references Schema B for a particular set of validation rules. External References enable a development team (or several teams) to reuse common Schemas and definitions across the enterprise.

Example 5-36 shows our speaker Schema that now references an external (second) Schema.

Example 5-36. ex-14-exernal-ref-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"$ref":"http://localhost:8081/ex-14-my-common-schema.json#/definitions/emailPattern"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName"]}

Notice the two key differences:

-

The

definitionsObject has been factored out of this schema. Don’t worry; it comes back really soon. -

The

emailfield’s$refnow points to an external Schema (ex-14-my-common-schema.json) to find the definition/validation rule for this field. We’ll cover the HTTP address to the external Schema later in this chapter.

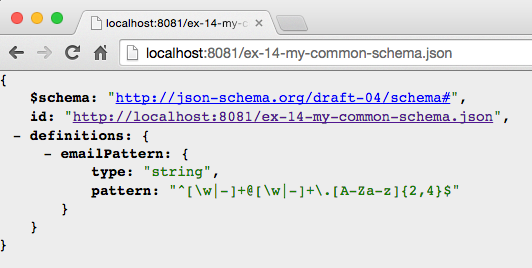

Example 5-37 shows the External Schema.

Example 5-37. ex-14-my-common-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","id":"http://localhost:8081/ex-14-my-common-schema.json","definitions":{"emailPattern":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"}}}

The definitions object that contains the emailPattern validation rule now resides in the external Schema. But at this point, you may be asking the follow questions:

-

How does the reference actually work?

-

How does a JSON Schema Validator locate the external Schema?

-

In ex-14-exernal-ref-schema.json, the URI prefix (

http://localhost:8081/ex-14-my-common-schema.json) before the#in the$reftells the JSON Schema processor to look for theemailPatterndefinition in an external Schema. -

In ex-14-my-common-schema.json (the external Schema), the

idfield (a JSON Schema keyword) at the root of the Schema makes the content of the Schema available to external access. -

The URI in

$refandidshould be an exact match to make the reference work properly. -

The

definitionsobject works the same as it did for internal references.

Example 5-38 shows a JSON document that conforms to the Schema. Notice that this document has neither changed nor is it aware of the external Schema.

Example 5-38. ex-14-external-ref.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

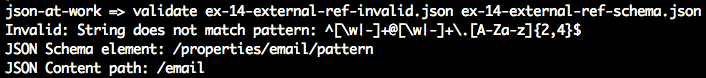

Example 5-39 shows a document that won’t validate against the Schema because the email is missing the trailing .com.

Example 5-39. ex-14-external-ref-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard"}

There are two ways to validate the preceding document against the Schema:

-

The filesystem

-

The web

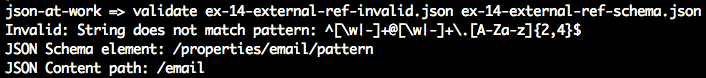

Let’s start by validating on the filesystem by using the validate tool that we’ve been using all along:

The JSON document (ex-14-external-ref-invalid.json) is invalid as in previous runs, but notice the inclusion of both the main (ex-14-external-ref-schema.json) and external (ex-14-my-common-schema.json) Schemas on the command line.

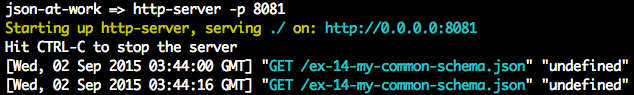

Now let’s use the web to validate against the external Schema. In this case, we’ll deploy this file as

static content on a web server so that the URI in the $ref and id (http://localhost:8081/ex-14-my-common-schema.json#/definitions/emailPattern)

will work properly. If you haven’t done so before, now would be a great time to install the http-server Node.js module.

To install and run it, follow the instructions in Appendix A (see “Install npm Modules”).

Run http-server (on port 8081) in the same directory where the external Schema resides, and your command

line should look like this:

When you visit http://localhost:8081/ex-14-my-common-schema.json in your browser, you should see the screen in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5. Web-addressable external Schema

Now that the external Schema is web addressable, we can do the validation, and you’ll see that the document is invalid:

Choosing Validation Rules

In addition to the requires and dependencies keywords, JSON Schema provides finer-grained mechanisms to

tell the Schema processor which validation rules to use. These additional keywords are as follows:

oneOf-

One, and only one, rule must match successfully.

anyOf-

One or more rules must match successfully.

allOf-

All rules must match successfully.

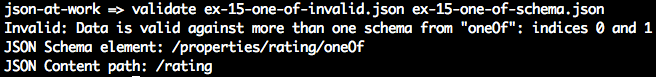

oneOf

The oneOf keyword enforces an exclusive choice between validation rules. In the Schema in Example 5-40, the

value of the rating field can either be less than 2.0 or less than 5.0, but not both.

Example 5-40. ex-15-one-of-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"type":"string"},"postedSlides":{"type":"boolean"},"rating":{"type":"number","oneOf":[{"maximum":2.0},{"maximum":5.0}]}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName","postedSlides","rating"]}

Example 5-41 is valid because the value of the rating field is 4.1, which matches only one of

the validation rules (< 5.0), but not both.

Example 5-41. ex-15-one-of.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","postedSlides":true,"rating":4.1}

The JSON document in Example 5-42 is invalid because the value of the rating field is 1.9, which matches both validation rules (< 2.0 and < 5.0).

Example 5-42. ex-15-one-of-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","postedSlides":true,"rating":1.9}

Validate the preceding document from the command line, and you’ll see that it’s invalid:

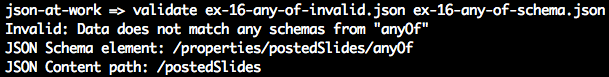

anyOf

The anyOf keyword allows for a match against any (one or more) of the validation rules. In Example 5-43, we’ve expanded the potential values of postedSlides to allow for [Y|y]es and

[N|n]o in addition to a boolean.

Example 5-43. ex-16-any-of-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"postedSlides":{"anyOf":[{"type":"boolean"},{"type":"string","enum":["yes","Yes","no","No"]}]},"rating":{"type":"number"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName","postedSlides","rating"]}

Example 5-44 is valid because the value of postedSlides is "yes".

Example 5-44. ex-16-any-of.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","postedSlides":"yes","rating":4.1}

Example 5-45 is invalid because the value of the postedSlides field is "maybe", which is not

in the set of allowed values.

Example 5-45. ex-16-any-of-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","postedSlides":"maybe","rating":4.1}

Validate this document from the command line, and you’ll see that it’s invalid:

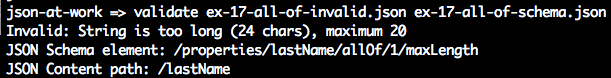

allOf

With the allOf keyword, the data must match all of the validation rules. In the Schema in Example 5-46, the

lastName must be a string with a length < 20.

Example 5-46. ex-17-all-of-schema.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"email":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"allOf":[{"type":"string"},{"maxLength":20}]},"postedSlides":{"type":"boolean"},"rating":{"type":"number","maximum":5.0}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["email","firstName","lastName","postedSlides","rating"]}

Example 5-47 is valid because the length of the lastName is ≤ 20.

Example 5-47. ex-17-all-of.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","postedSlides":true,"rating":4.1}

Example 5-48 is invalid because the length of the lastName exceeds 20 characters.

Example 5-48. ex-17-all-of-invalid.json

{"email":"larsonrichard@ecratic.com","firstName":"Larson","lastName":"ThisLastNameIsWayTooLong","postedSlides":true,"rating":4.1}

Validate the preceding document, and you’ll see that it’s invalid:

We’ve covered the basics of JSON Schema and syntax, and now it’s time to design an API with JSON Schema.

How to Design and Test an API with JSON Schema

JSON Schema is all about the semantics (the meaning) and structure of the data exchanged by applications and APIs. In the context of API Design, think of a JSON Schema as part of the contract (interface). In this last portion of the chapter, we’ll go from concept to a running Stub API that other applications and APIs can start testing and using.

Our Scenario

We’ll use the same speaker model that we’ve been using all along, and iteratively add constraints and

capabilities. Here are the steps we need in order to go from a concept to a running Stub API:

-

Model a JSON document.

-

Generate a JSON Schema.

-

Generate sample data.

-

Deploy a Stub API with

json-server.

Model a JSON Document

Before creating a Schema, we need to know the data that we’re exchanging. Besides the fields and their formats, it’s important to get a good look-and-feel for the data itself. To do this, we need to overcome one of the major issues with JSON itself: creating documents by hand is tedious and error-prone. Use a modeling tool rather than doing a lot of typing. There are several good tools to support this, and my favorite is JSON Editor Online. Refer to “Model JSON Data with JSON Editor Online” in Chapter 1 for further details on the features of JSON Editor Online.

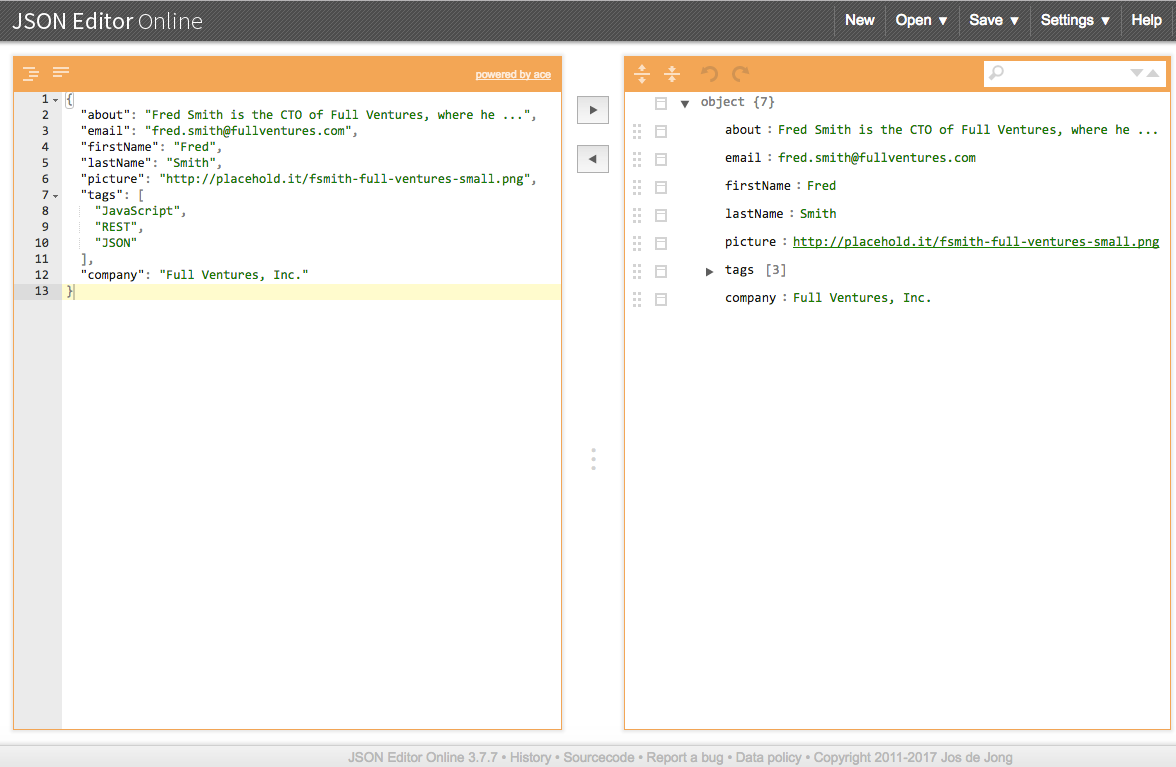

Figure 5-6 shows our speaker model.

Figure 5-6. Speaker model on jsoneditoronline.com

Rather than typing the JSON document, use JSON Editor Online to model the data, and generate a JSON document. In the JSON model on the righthand portion of the screen, click the icon next to an element (i.e., Object, key/value pair, Array) and you’ll see a menu. Select Append or Insert to add elements:

-

Objects

-

Name/value pairs

-

Arrays

After entering a few fields, press the left-arrow button (in the middle of the page) to create the JSON document. You can then iteratively add, test, and review the content of your document until it looks good. Then, save the JSON document, shown in Example 5-49, into a file (with the Save to Disk option under the Save menu).

Example 5-49. ex-18-speaker.json

{"about":"Fred Smith is the CTO of Full Ventures, where he ...","email":"fred.smith@fullventures.com","firstName":"Fred","lastName":"Smith","picture":"http://placehold.it/fsmith-full-ventures-small.png","tags":["JavaScript","REST","JSON"],"company":"Full Ventures, Inc."}

Before going any further, it would be a good idea to validate the JSON document by using JSONLint (either with the CLI or web app). This should validate because JSON Editor Online produces valid JSON, but it’s always good to double-check.

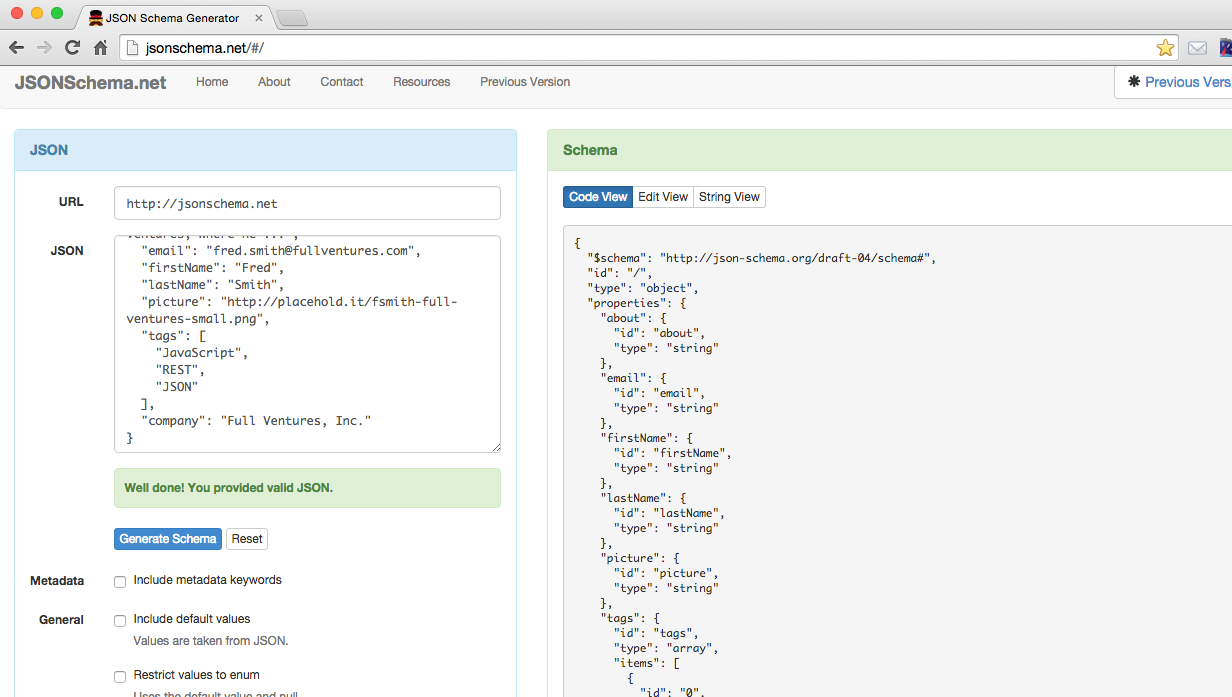

Generate a JSON Schema

With a valid JSON document in hand, we can now use JSONSchema.net to generate a corresponding JSON Schema based on the document structure and content. Again, save yourself a lot of typing by letting a tool do most of the work for you.

Visit http://jsonschema.net and paste in the JSON document on the left side, as shown in Figure 5-7.

Figure 5-7. Generate Speakers Schema on JSONSchema.net

To generate a Schema, start with the default settings, and make the following changes:

-

Turn off “Use absolute IDs.”

-

Turn off “Allow additional properties.”

-

Click the Generate Schema button.

-

Copy the generated Schema (on the righthand side) to your clipboard.

After saving your clipboard to a file, we now have the Schema in Example 5-50.

Example 5-50. ex-18-speaker-schema-generated.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","id":"/","type":"object","properties":{"about":{"id":"about","type":"string"},"email":{"id":"email","type":"string"},"firstName":{"id":"firstName","type":"string"},"lastName":{"id":"lastName","type":"string"},"picture":{"id":"picture","type":"string"},"tags":{"id":"tags","type":"array","items":[{"id":"0","type":"string"},{"id":"1","type":"string"},{"id":"2","type":"string"}]},"company":{"id":"company","type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["about","email","firstName","lastName","picture","tags","company"]}

JSONSchema.net is great at generating a base Schema, but it adds fields that we don’t use, plus it doesn’t

do enum, pattern, and so forth. The main takeaway is that JSONSchema.net does about 80 percent of the work for you,

and then you need to fill in a few pieces yourself. We don’t need the id fields at this time, but we do

need to add a Regular Expression to validate the email field (just use the Regex from previous examples).

After making these changes, the Schema should look like Example 5-51.

Example 5-51. ex-18-speaker-schema-generated-modified.json

{"$schema":"http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#","type":"object","properties":{"about":{"type":"string"},"email":{"type":"string","pattern":"^[\\w|-|.]+@[\\w]+\\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}$"},"firstName":{"type":"string"},"lastName":{"type":"string"},"picture":{"type":"string"},"tags":{"type":"array","items":[{"type":"string"}]},"company":{"type":"string"}},"additionalProperties":false,"required":["about","email","firstName","lastName","picture","tags","company"]}

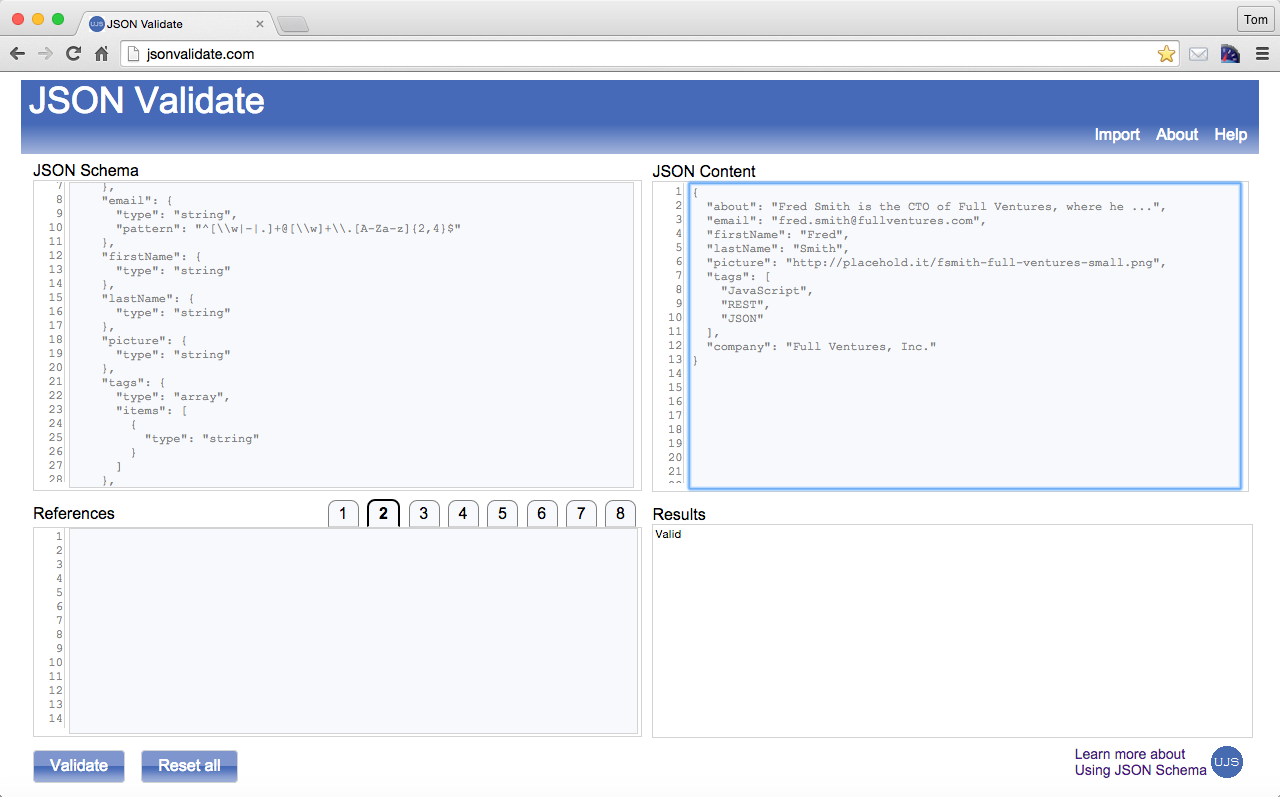

Validate the JSON Document

Now that we have a JSON Schema, let’s validate the document against the Schema by using the JSON Validate web app. Visit http://jsonvalidate.com/ and paste in the JSON document and Schema, as shown in Figure 5-8.

Figure 5-8. Validate Speakers JSON document against Speakers JSON Schema on jsonvalidate.com

Click the Validate button, and the document should validate against the Schema. You could have used

the validate CLI tool we’ve been using throughout this chapter, but the web app is a great visual.

Generate Sample Data

At this point, we have a JSON document with its corresponding Schema, but we need more data to create an API for testing. We could use JSON Editor Online to generate test data, but there are a couple of issues with this approach because a human would have to randomize and generate massive amounts of data. Even with a GUI, it’s a big manual effort.

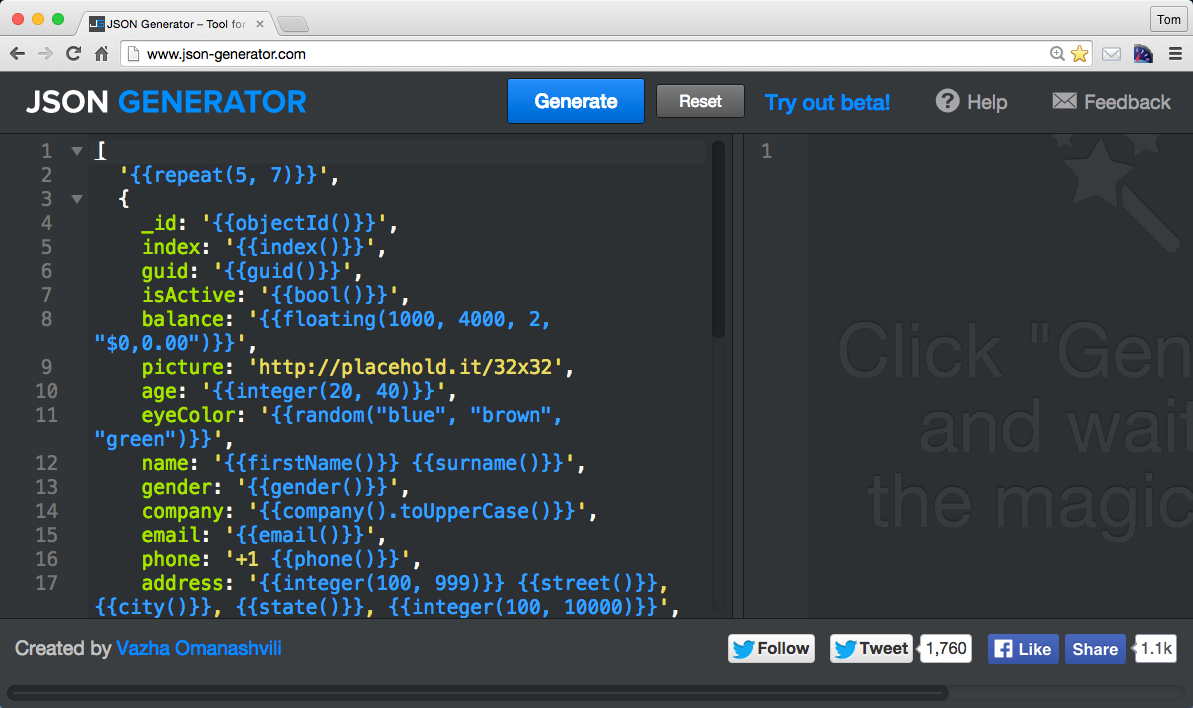

JSON Editor Online is great for creating a small JSON document to get the design process going, but we need another approach to generate randomized bulk JSON data for API testing. We’ll use JSON Generator to create our data; visit http://www.json-generator.com/ and you should see the screen in Figure 5-9.

Figure 5-9. json-generator site

The code on the left side is a template (in the form of a JavaScript Object Literal) that JSON

Generator uses to generate sample JSON data. Notice that this tool has the ability to generate sample/random

data for paragraphs, numbers, names, globally unique identifiers (GUIDs), names, gender, email addresses, etc.

Plus, it has the ability to do this in bulk with the {{repeat}} tag at the top of the template. Click

the Help button for detailed documentation on the tags.

But these default settings are way more than we need. Let’s pare this template down to the fields we need to

generate three speaker objects with random data (see Example 5-52).

Example 5-52. ex-18-speaker-template.js

// Template for http://www.json-generator.com/['{{repeat(3)}}',{id:'{{integer()}}',picture:'http://placehold.it/32x32',name:'{{firstName()}}',lastName:'{{surname()}}',company:'{{company()}}',:'{{email()}}',about:'{{lorem(1, "paragraphs")}}'}]

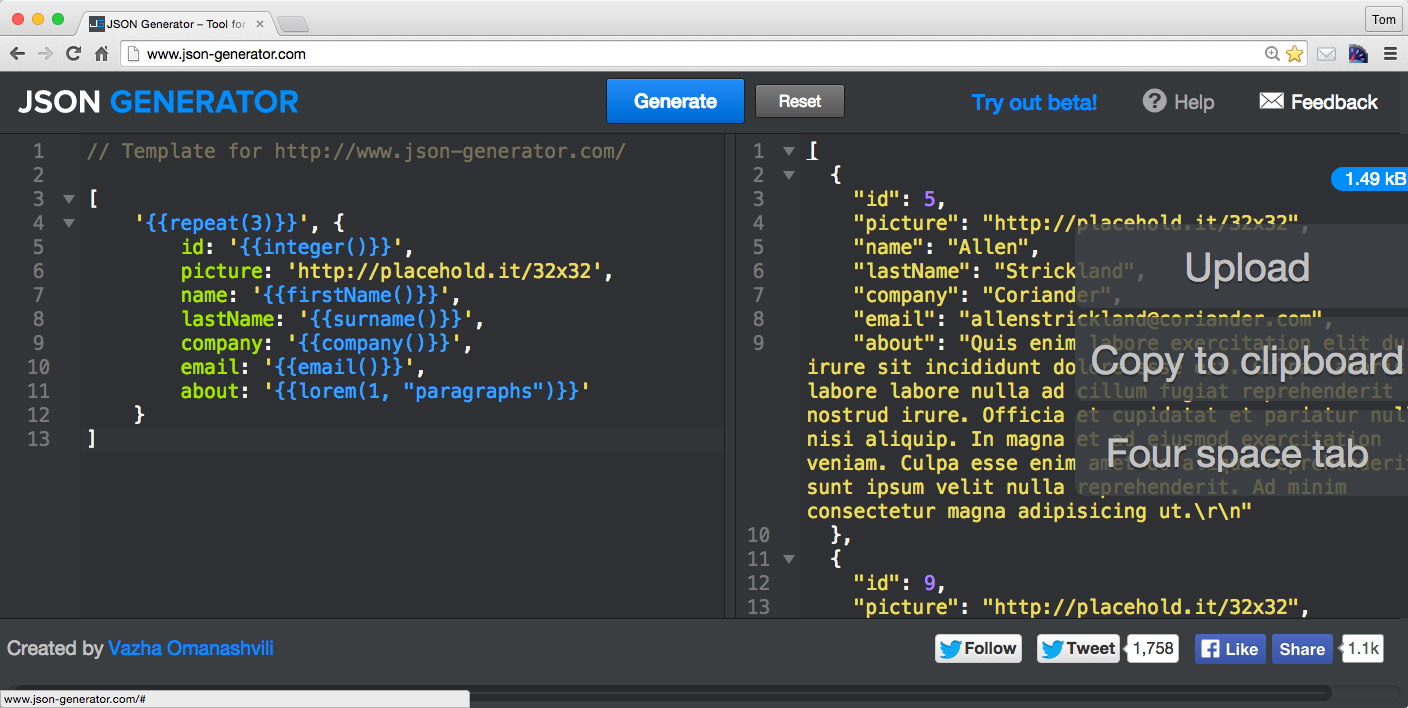

After clicking the Generate button, you should see the following JSON document in the web app shown in Figure 5-10 (if you want

more than the three speaker objects, just change the 3 in the repeat tag to a higher number).

Figure 5-10. Create a Speaker JSON document with json-generator

Now, click the Copy to Clipboard button on the righthand side, and paste into a file, as shown in Example 5-53.

Example 5-53. ex-18-speakers-generated.json

[{"id":5,"picture":"http://placehold.it/32x32","name":"Allen","lastName":"Strickland","company":"Coriander","email":"allenstrickland@coriander.com","about":"Quis enim labore ..."},{"id":9,"picture":"http://placehold.it/32x32","name":"Merle","lastName":"Prince","company":"Xylar","email":"merleprince@xylar.com","about":"Id voluptate duis ..."},{"id":8,"picture":"http://placehold.it/32x32","name":"Salazar","lastName":"Ewing","company":"Zentime","email":"salazarewing@zentime.com","about":"Officia qui id ..."}]

We’re almost there, but we need to tweak the data just a bit so that we can deploy the file as an API:

-

We already have an Array. Let’s name it

speakers, and then wrap it with the{and}. We now have a JSON document with thespeakersArray as the root element. -

Let’s redo the

idfields so that they start at 0.

Our file now looks like Example 5-54.

Example 5-54. ex-18-speakers-generated-modified.json

{"speakers":[{"id":0,"picture":"http://placehold.it/32x32","name":"Allen","lastName":"Strickland","company":"Coriander","email":"allenstrickland@coriander.com","about":"Quis enim labore ..."},{"id":1,"picture":"http://placehold.it/32x32","name":"Merle","lastName":"Prince","company":"Xylar","email":"merleprince@xylar.com","about":"Id voluptate duis ..."},{"id":2,"picture":"http://placehold.it/32x32","name":"Salazar","lastName":"Ewing","company":"Zentime","email":"salazarewing@zentime.com","about":"Officia qui id ..."}]}

At this point, you’re probably wondering why we needed to make those modifications. The changes were needed

so that json-server has the proper URIs (routes) for the Speaker data:

-

We get the http://localhost:5000/speakers route by encapsulating with the

speakersarray, with all the data addressable from there. -

We can access the first element with this route: http://localhost:5000/speakers/0.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s get json-server up and running, and then start browsing the

API.

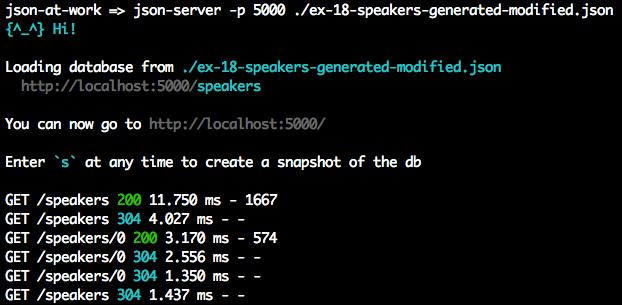

Deploy a Stub API with json-server

Now that we have a Schema and some test data, it’s time to deploy the sample data as an API so

consumers can start testing it and provide feedback. If you haven’t done so before, now would be a great

time to install the json-server Node.js module. To install and run it, follow the instructions in

Appendix A (see “Install npm Modules”).

Run json-server (on port 5000) in the same directory where the ex-18-speakers-generated-modified.json

file resides, and your command line should look like this:

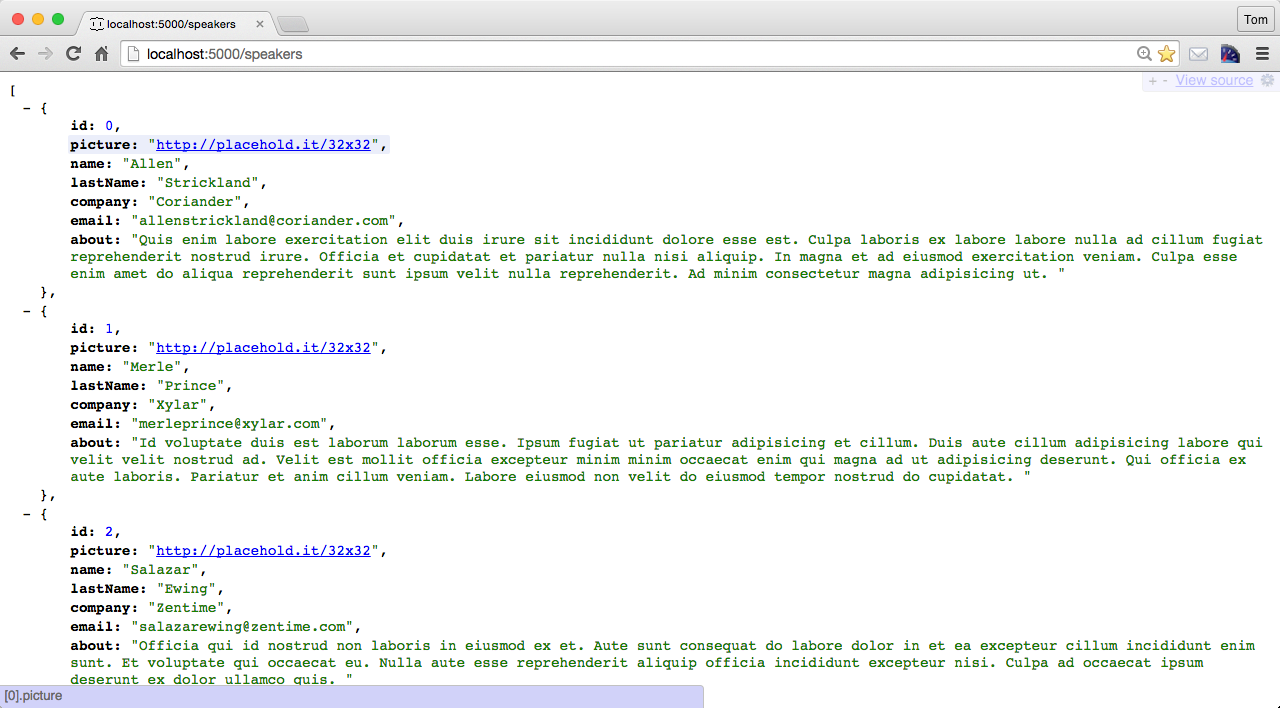

When you visit http://localhost:5000/speakers in your browser, you should see the screen in Figure 5-11.

Figure 5-11. Speakers Stub API on json-server

You now have a testable API without writing a single line of code; we just deployed a static JSON file. The beauty of this approach is that this looks, acts, and feels like an API. From here, you can interact with it just as you would with other APIs. You could use your browser, cURL, or make HTTP calls from your favorite language to begin interacting with it.

Now there are limits. With json-server, you can do an HTTP GET only on the data—it’s read only.

Final Thoughts on API Design and Testing with JSON Schema

After going through this exercise, you should have an appreciation for the powerful JSON-based open source tools that can shorten your API development life cycle. Here’s the bottom line:

-

Use JSON modeling tools before committing to the final data structure. Iterate with stakeholders early and often.

-

Writing a JSON document or Schema by hand is tedious and error-prone. Let the tools do most of the work for you and avoid as much typing as possible.

-

Validate early and often.

-

Generate bulk randomized JSON data rather than creating it yourself.

-

Spinning up a Stub API is simple. Don’t write your own testing infrastructure, because someone else has already done it for you. Just use what’s out there. You have better things to do with your time.

Validation Using a JSON Schema Library

We’ve shown how to use the validate command-line tool and the JSON Validate web app to validate a JSON

document against a Schema, but the ultimate goal is to validate from an application.

But JSON Schema isn’t only just for JavaScript and Node.js. Most major platforms have excellent support for JSON Schema v4:

- Ruby on Rails

- Java

- PHP

- Python

- Clojure

-

Just use the Java-based

json-schema-validator. - Node.js

-

Node.js has several good JSON Schema processors. I’ve had success with the following:

-

ajvis my favorite library to use from a Node.js-based application because it’s clean and simple.ajvis compatible with popular Node.js-based testing suites (e.g., Mocha/Chai, Jasmine, and Karma). You can find more information onajvon the npm site and on GitHub. We’ll show how to useajvin Chapter 10. -

ujs-jsonvalidateis a processor we’ve been using all through this chapter to validate against a Schema from the command line. You can find further usage information on GitHub. You can find theujs-jsonvalidatenpm module at http://bit.ly/2tj4ODI.

-

Where to Go Deeper with JSON Schema

We’ve covered the basics of JSON Schema, but a definitive guide is far beyond the scope of this chapter. In addition to the json-schema.org site mentioned previously, here are a few more resources:

-

Using JSON Schema by Joe McIntyre provides a wealth of JSON Schema-related reference information and tools, including these:

What’s Next?

Now that we’ve shown how to structure and validate JSON instance documents with JSON Schema, we’ll show to how search JSON documents in Chapter 6.