Practical Data Integration for the Web

Copyright © 2017 Vertical Slice, Inc. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449358327 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. JSON at Work, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-449-35832-7

[LSI]

To everyone who produces or consumes JSON data with web/mobile applications, REST APIs, and messaging systems—I hope this makes your job easier.

To the unsung JSON community that produces JSON-based tools and libraries for the rest of us—thank you for all your hard work to make JSON useful and meaningful.

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) has become the de facto standard for RESTful interfaces, but an ecosystem of little-known standards, tools, and technologies is available that architects and developers can start using today to build well-designed applications. JSON is more than just a simple replacement for XML when you make an AJAX call. It is becoming the backbone of any serious data interchange over the internet. Solid standards and best practices can be used to harness the energy and enthusiasm around JSON to build truly elegant, useful, and efficient applications.

The only thing missing is a book to pull everything together. This book aims to help developers leverage JSON so that they can build enterprise-class applications and services. My goals are to promote the use of JSON tooling and the concept of message/document design as a first-class citizen in the fast-growing API community.

My journey into JSON began in 2007 when I was leading a large web portal project, and we had to populate a drop-down list with several thousand entries. At that time, I was reading Head First AJAX by Rebecca Riordan (O’Reilly), so I had a decent architectural approach. AJAX would solve overall latency and page load issues, but what about the data? I had been using XML successfully for several years, but it seemed like overkill for the task at hand—moving data from the backend of a web application to the View. Head First AJAX mentioned a new data format called JSON, and it looked like the way to go. My team began looking into APIs that would convert our Java objects into JSON, and chose the one that had the simplest and shortest JUnit tests—the goal was to do the simplest thing that could possibly work. We put the application under rigorous load testing, and the Java-to-JSON conversion was never a performance issue. The application scaled up in production, and the users saw their drop-down list in a timely manner.

Along my journey, I considered the use of JSON with web applications, RESTful APIs, and messaging. As of 2009, I was still working with XML because XML Schema provided the semantic validation needed for meaningful data interchange. So, my position at that time was to use JSON for web user interfaces, or UIs (for speed), and XML for Web Services and Messaging (for integration). But then I heard about JSON Schema in 2010, and found that I had no further need for XML. The JSON Schema specification is still under development, but it’s sufficiently mature enough now to use for enterprise-class integration.

At this point, I was hooked on or, more accurately, obsessed with JSON. I began looking around the internet to see what else JSON could do, and I found copious APIs, online tools, search capabilities, and more. In short, anything that has been done with XML can (and should) now be done with JSON.

I then began to look for JSON in books, and was disappointed when I could find only a chapter or two on the topic in a JavaScript or RESTful Web Services book. I saw a growing JSON community along with lots of tool support and articles and blogs, but there was no single place—other than Douglas Crockford’s JSON site—that pulled everything together.

This book is for architects and developers who design/implement web and mobile applications, RESTful APIs, and messaging applications. Code examples are in JavaScript, Node.js, Ruby on Rails, and Java. If you’re a Groovy, Go, Scala, Perl, Python, Clojure, or C# developer, you’ll need to follow along with the code examples provided. But rest assured that most major/modern languages provide excellent JSON support. For the architect, I’ve provided guidelines, best practices, and architecture and design diagrams where appropriate. But in addition to providing visionary leadership, real architects prove their ideas with working code. While I love working with JSON and writing code, it’s entirely meaningless without use cases, and a business and technical context. For developers, this book is packed with code examples, tooling, and Unit Tests, along with a GitHub repository (see “Code Examples”).

Chapters 5–10 only have code examples only in Node.js to keep things simple and focused. But it’s not hard to translate these examples into your platform of choice.

When I wrote JBoss at Work with Scott Davis back in the mid-2000s, our vision was to write a book that developers could use at work on their daily jobs. In the same manner, the purpose of JSON at Work is to provide practical examples to developers based on my real-world integration experience with JSON. To that end, I’ve baked Unit Testing (wherever feasible) into every chapter. It’s simple: if there’s no test for a piece of code, then that code doesn’t exist. Period.

Expect to roll up your sleeves and look at code. Whether you’re an architect or developer, you’ll find something here to help you on your job.

By reading and following this book’s examples, you’ll learn how to do the following:

JSON basics and how to model JSON data

Use JSON with Node.js, Ruby on Rails, and Java

Structure JSON documents with JSON Schema to design and test APIs

Search the contents of JSON documents with JSON Search tools

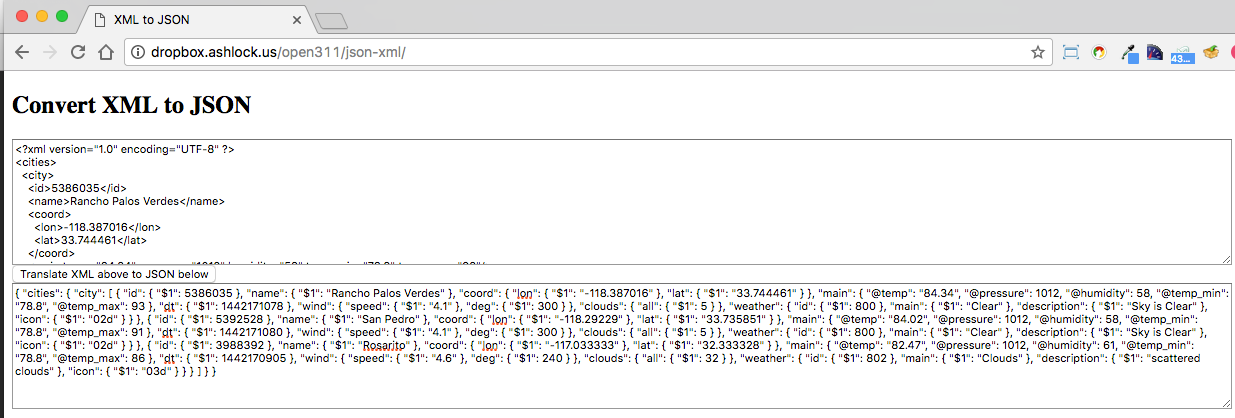

Convert JSON documents to other data formats with JSON Transform tools

Use JSON as part of an enterprise architecture

Compare JSON-based Hypermedia formats, including HAL and json:api

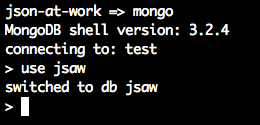

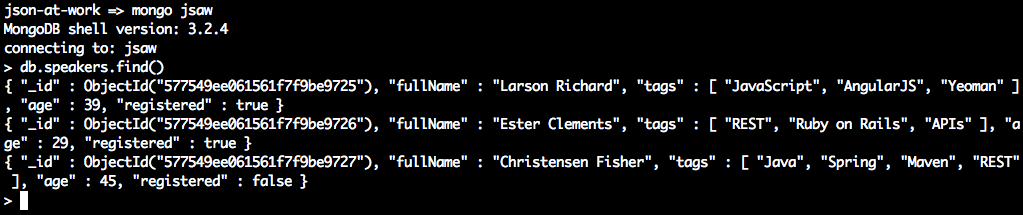

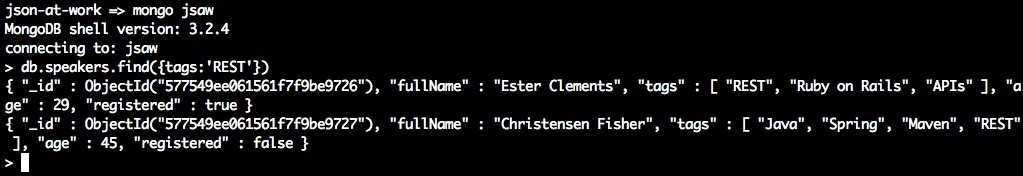

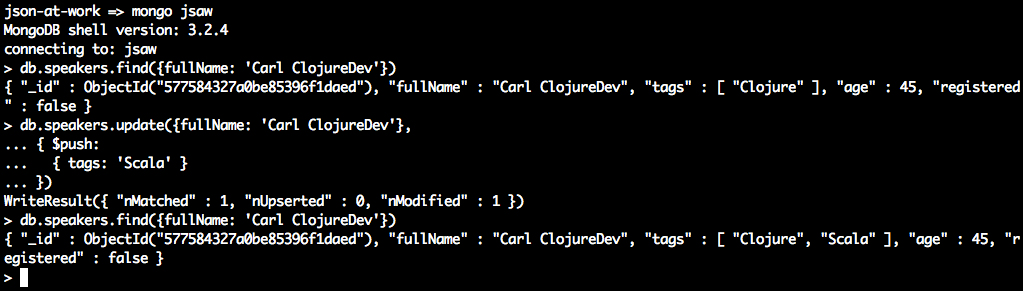

Leverage MongoDB to store and access JSON documents

Use Apache Kafka to exchange JSON-based messages between services

Use freely available JSON tools and utilities to simplify testing

Invoke APIs in your favorite programming language with simple utilities and libraries

Here’s a sample of the JSON tooling you’ll use in this book:

JSON editors/modelers

Unit-Testing tools (e.g., Mocha/Chai, Minitest, JUnit)

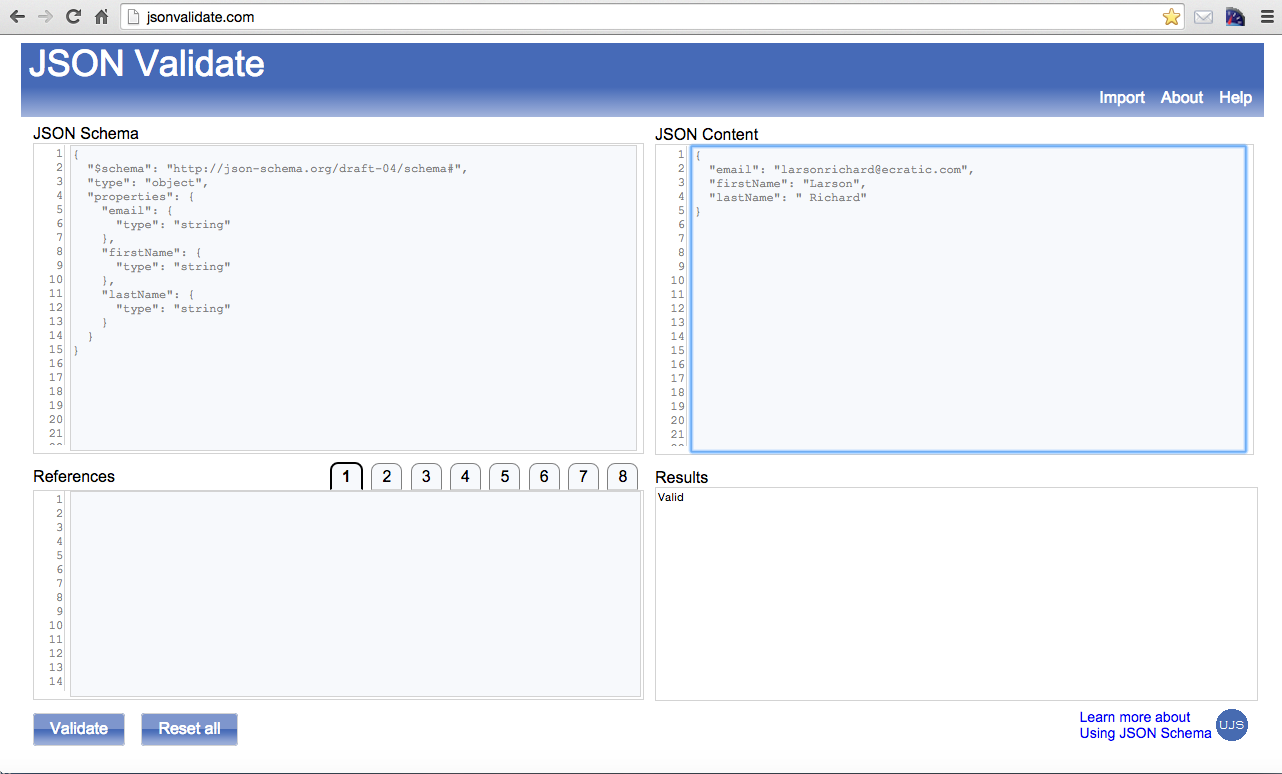

JSON Validators

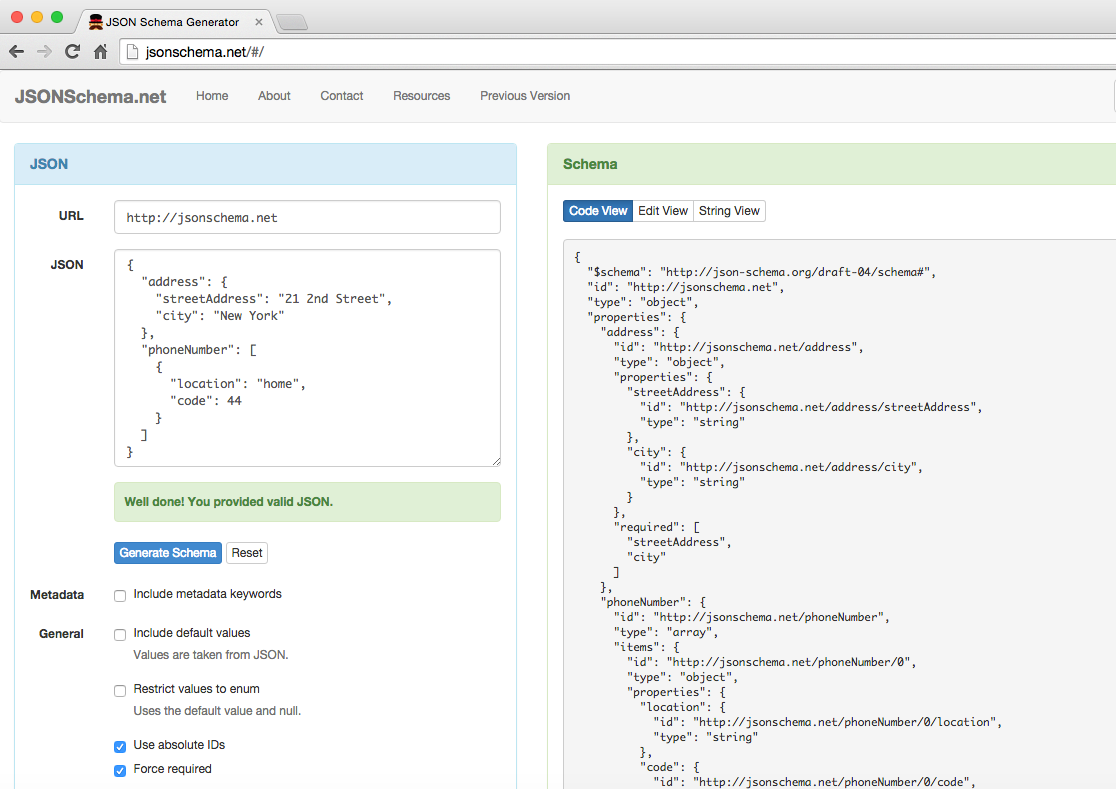

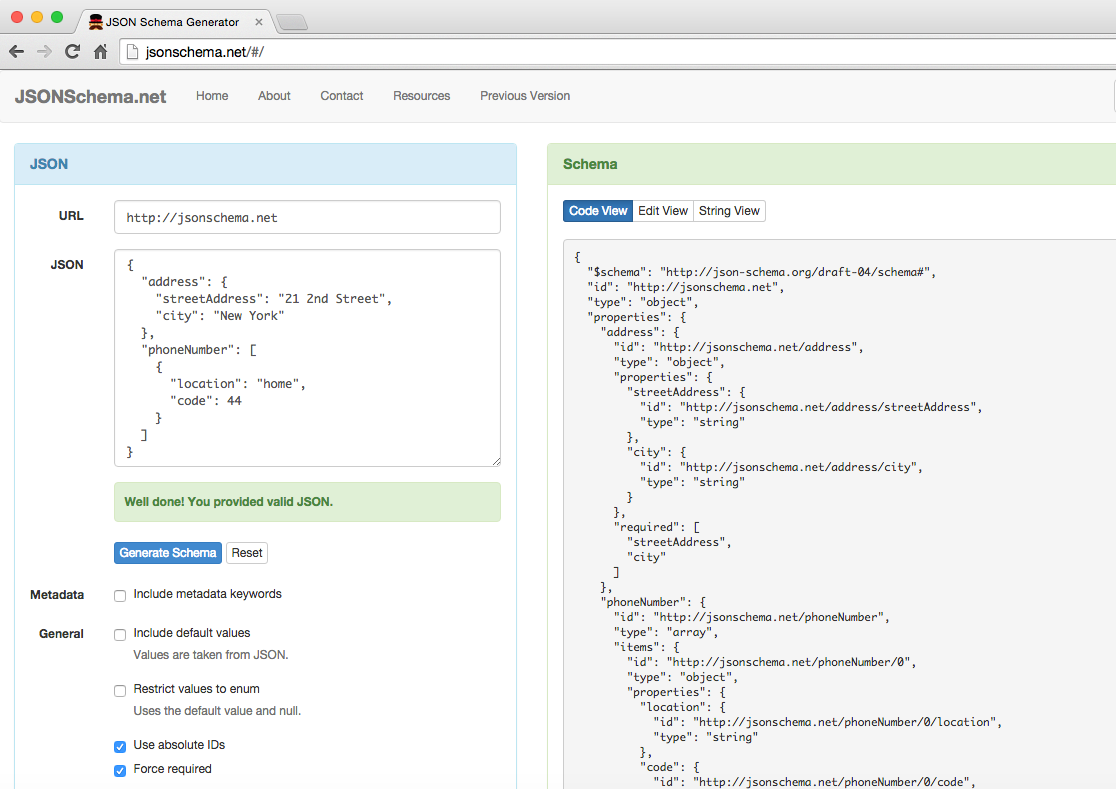

A JSON Schema Generator

JSON Search tools

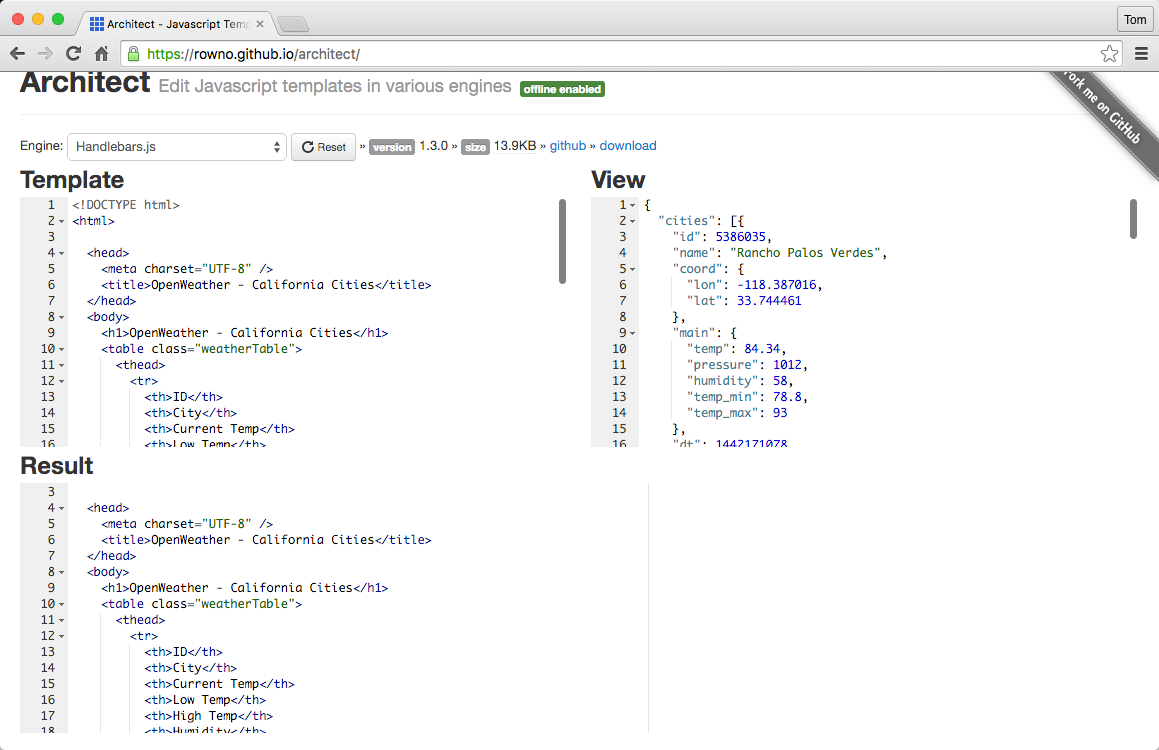

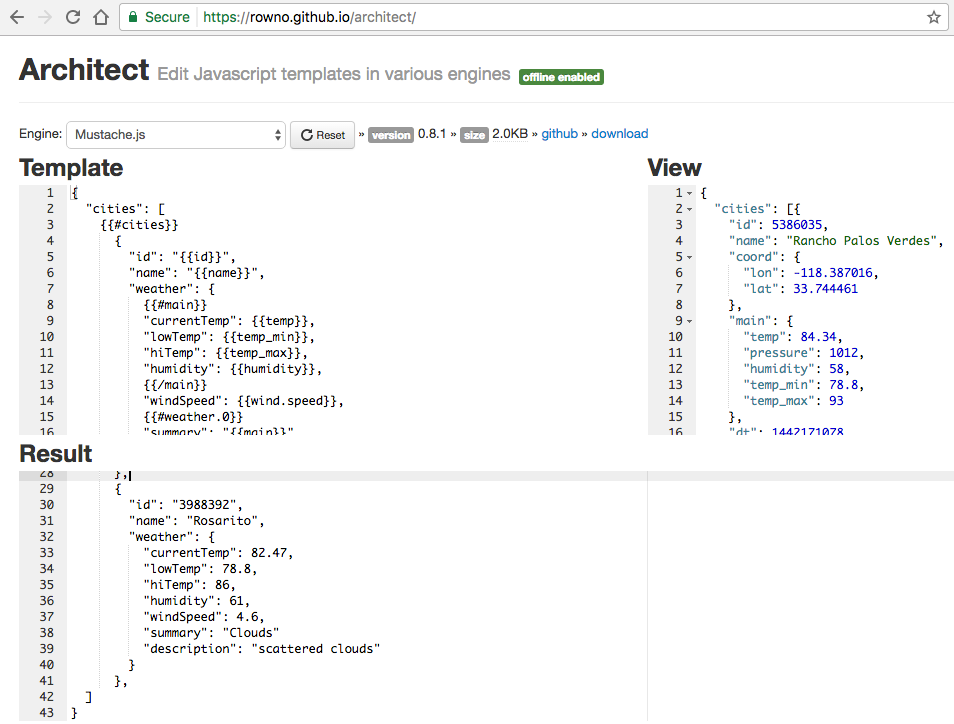

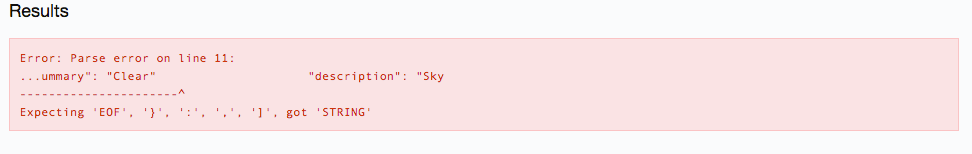

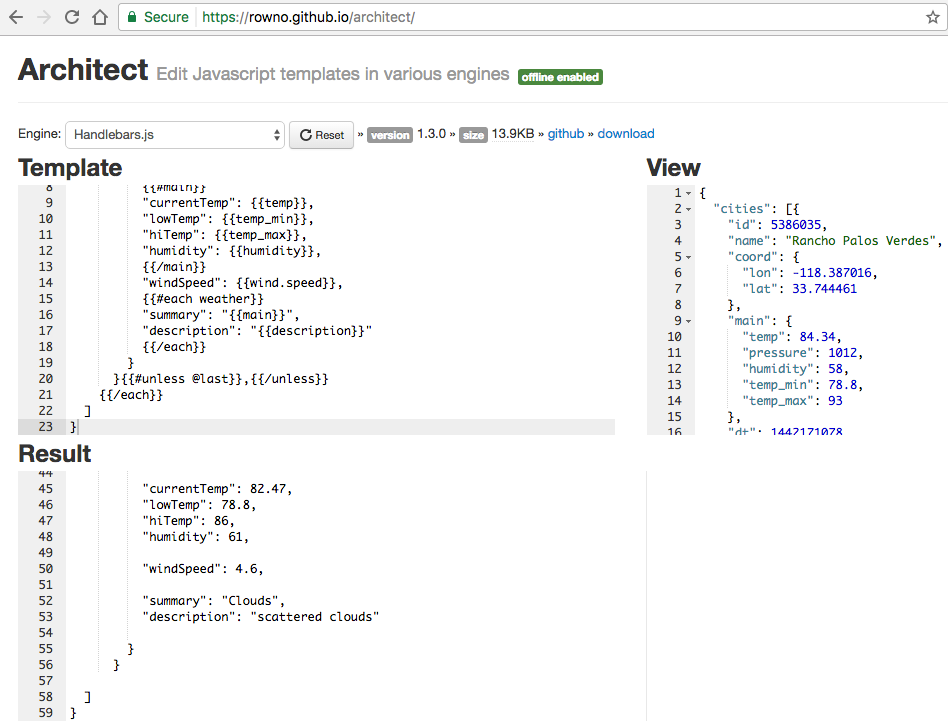

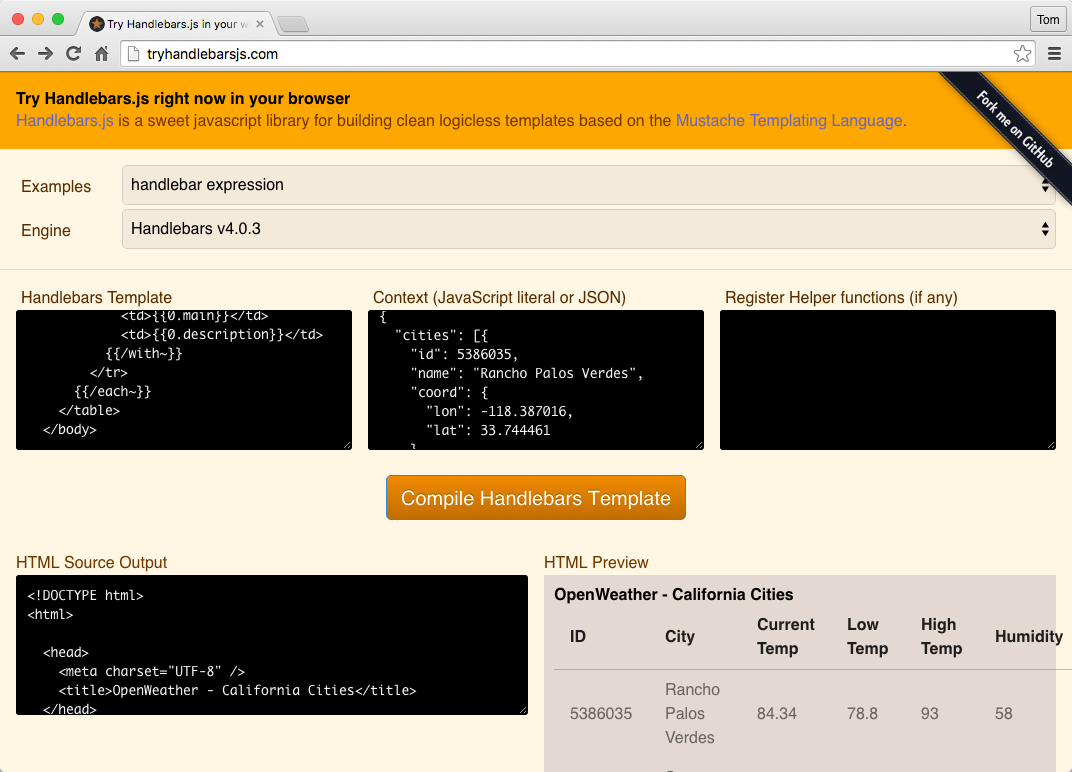

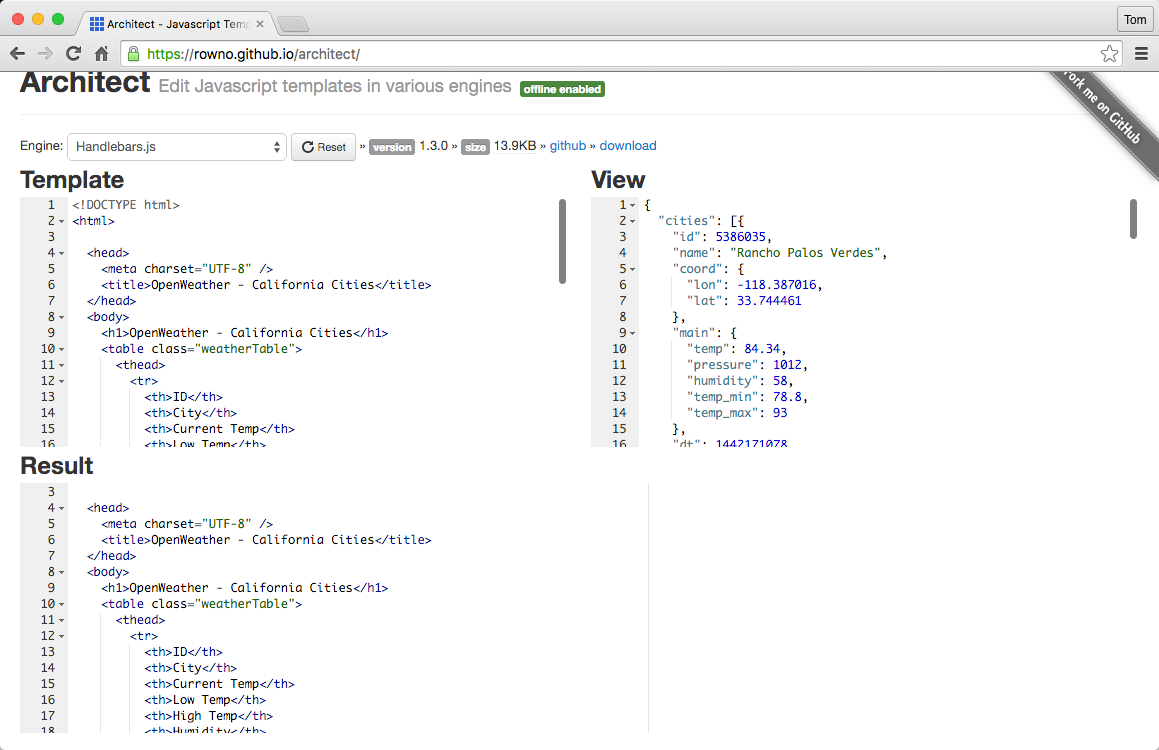

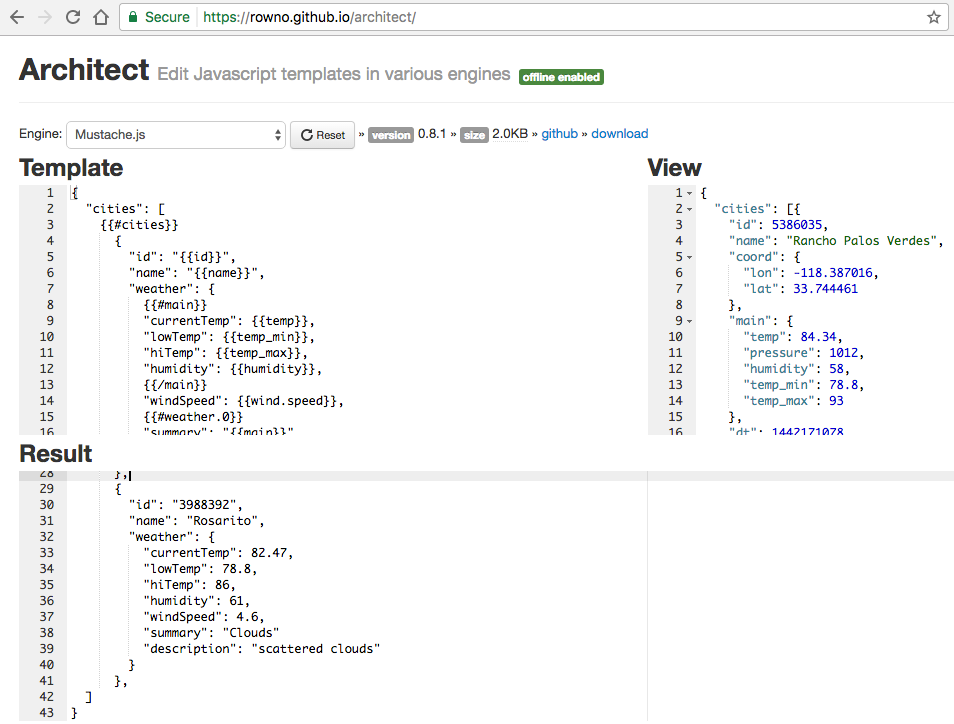

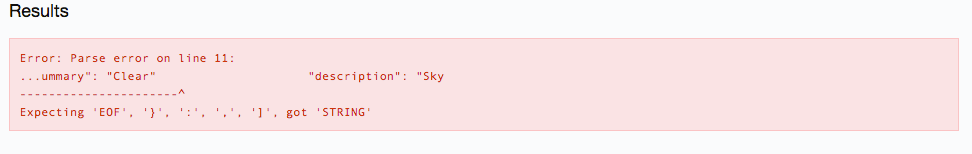

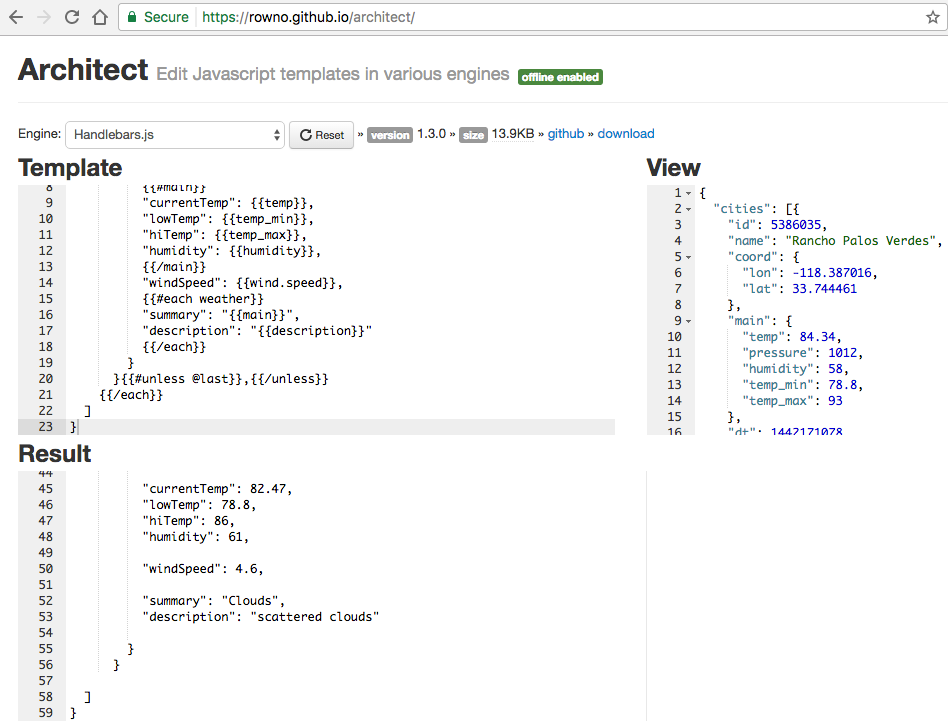

JSON Transform (templating) tools

This book is not for you if your only interest in JSON is to make AJAX calls from JavaScript. Although I cover this topic, it’s just the tip of the iceberg. Plenty of JavaScript books have the chapter you’re looking for.

Developers looking for a deep reference on REST, Ruby on Rails, Java, JavaScript, etc. won’t find it here. This book relies on these technologies, but focuses on how to use JSON with these languages and technologies.

This book consists of the following parts:

Appendices

Chapter 1, JSON Overview, starts with an overview of the JSON data format, describes best practices in JSON usage, and introduces the tools used throughout the book.

Chapter 2, JSON in JavaScript, shows how to use JSON with JavaScript, Node.js, and Mocha/Chai Unit Tests.

Chapter 3, JSON in Ruby on Rails, describes how to convert between Ruby objects and JSON, and integrate with Rails.

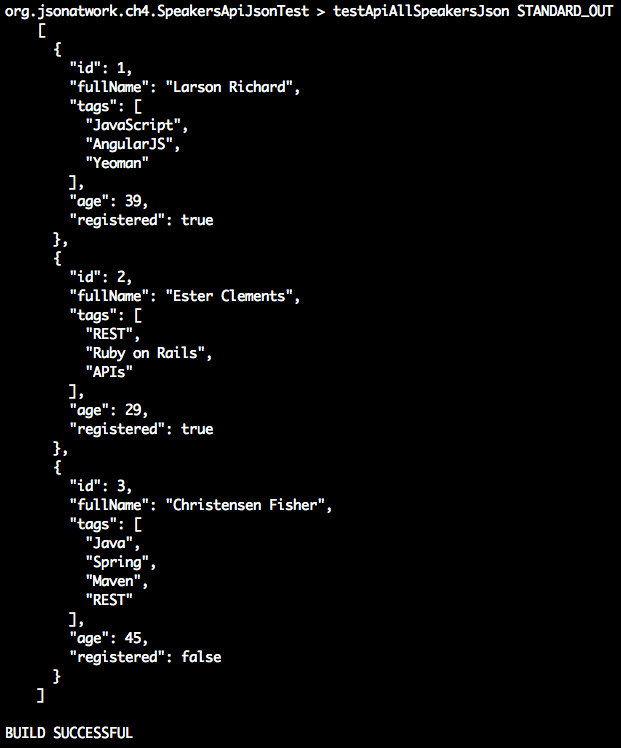

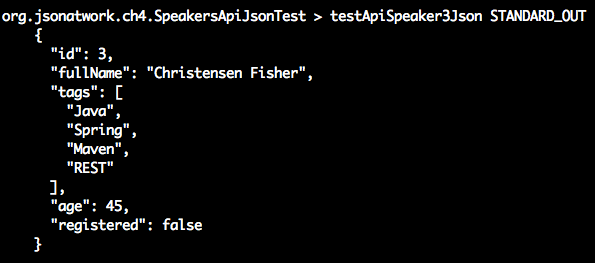

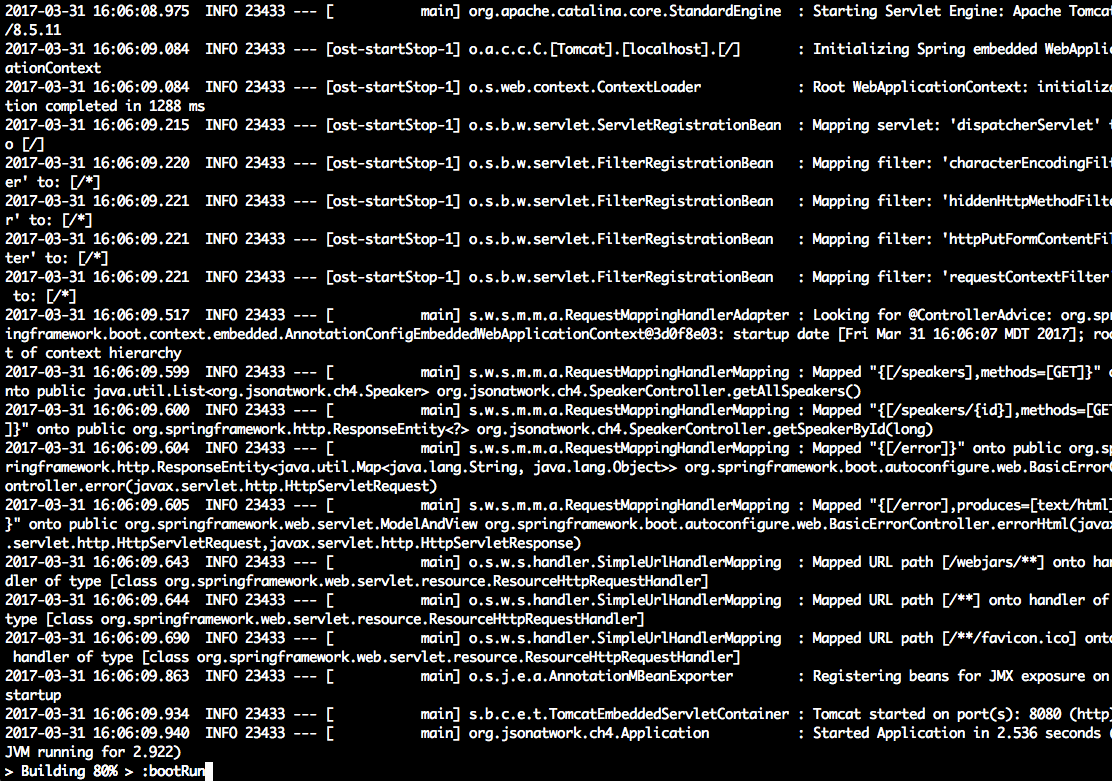

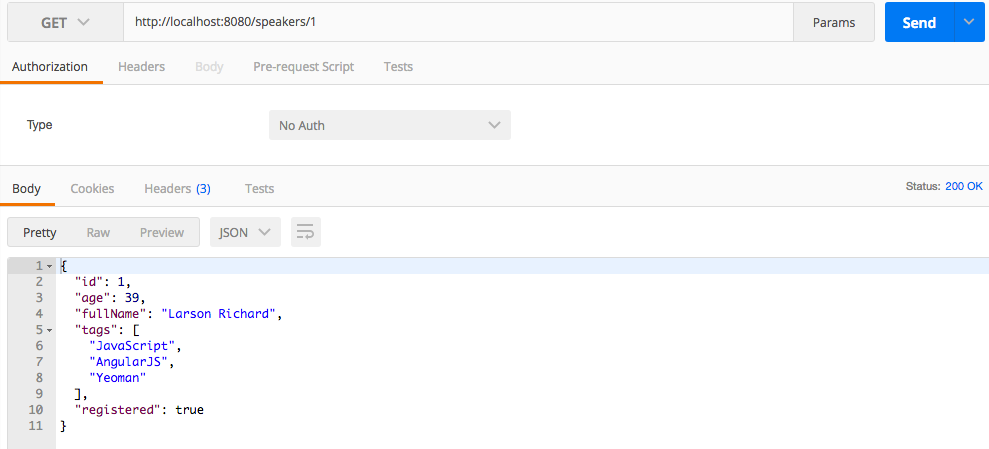

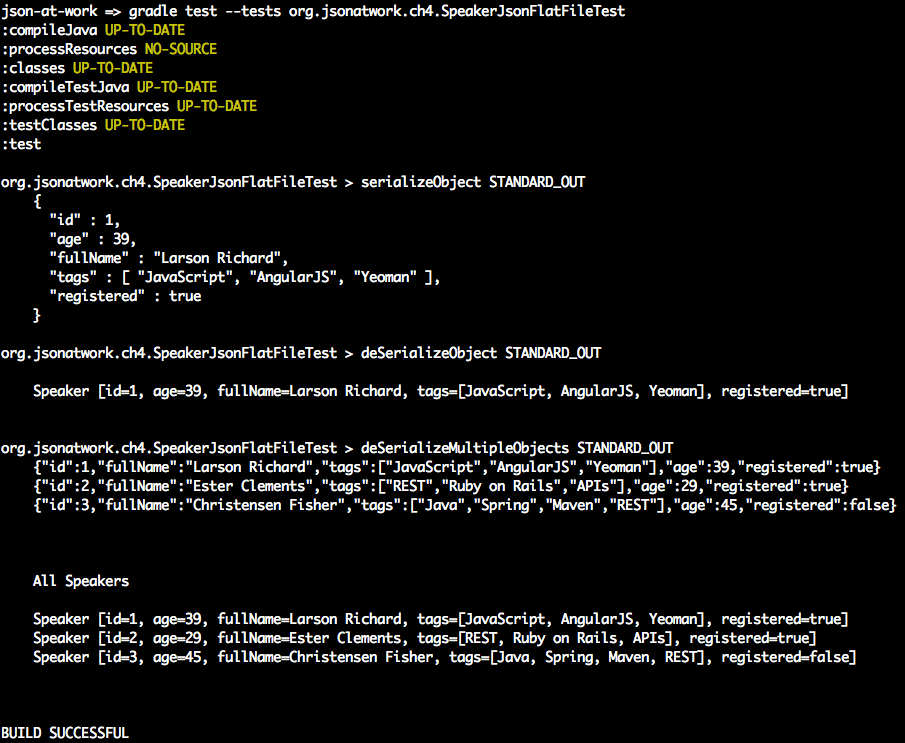

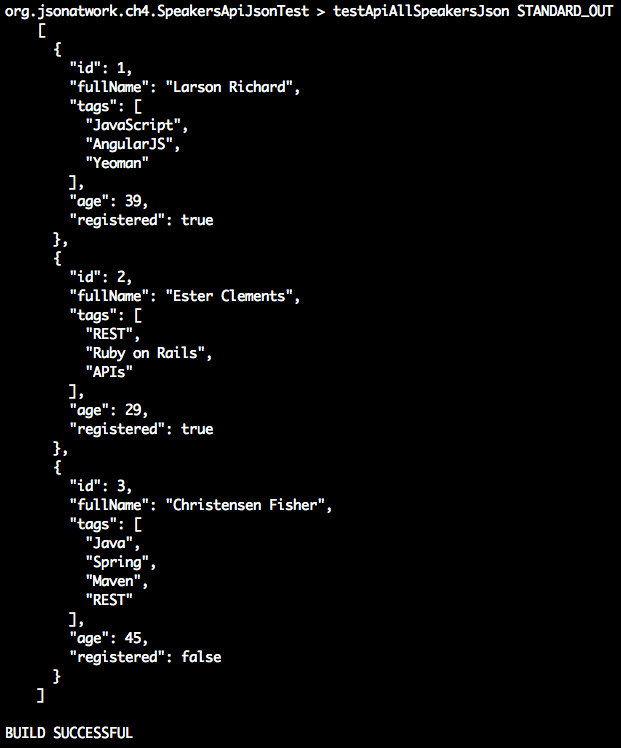

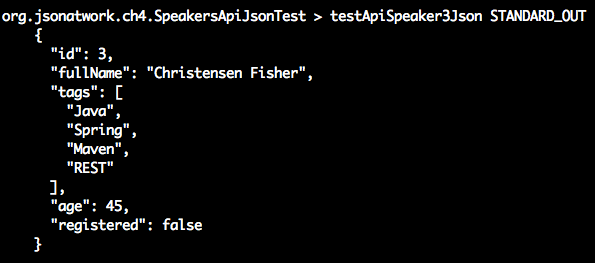

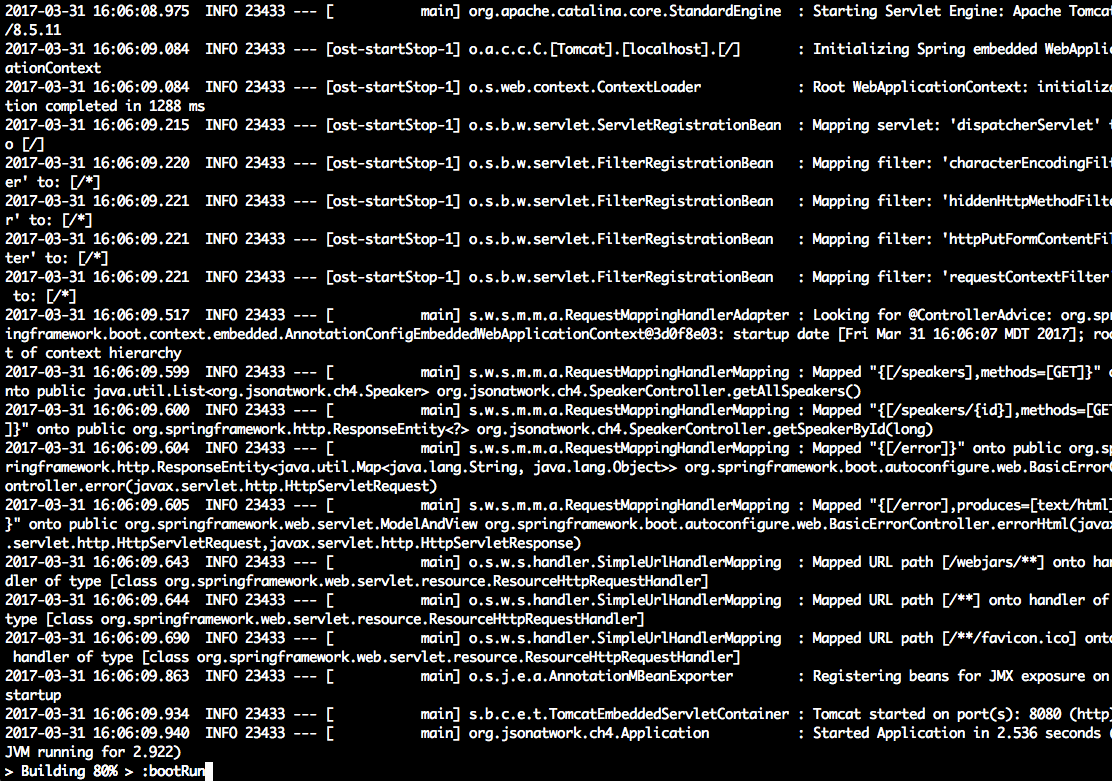

Chapter 4, JSON in Java, tells you how to use JSON with Java and Sprint Boot.

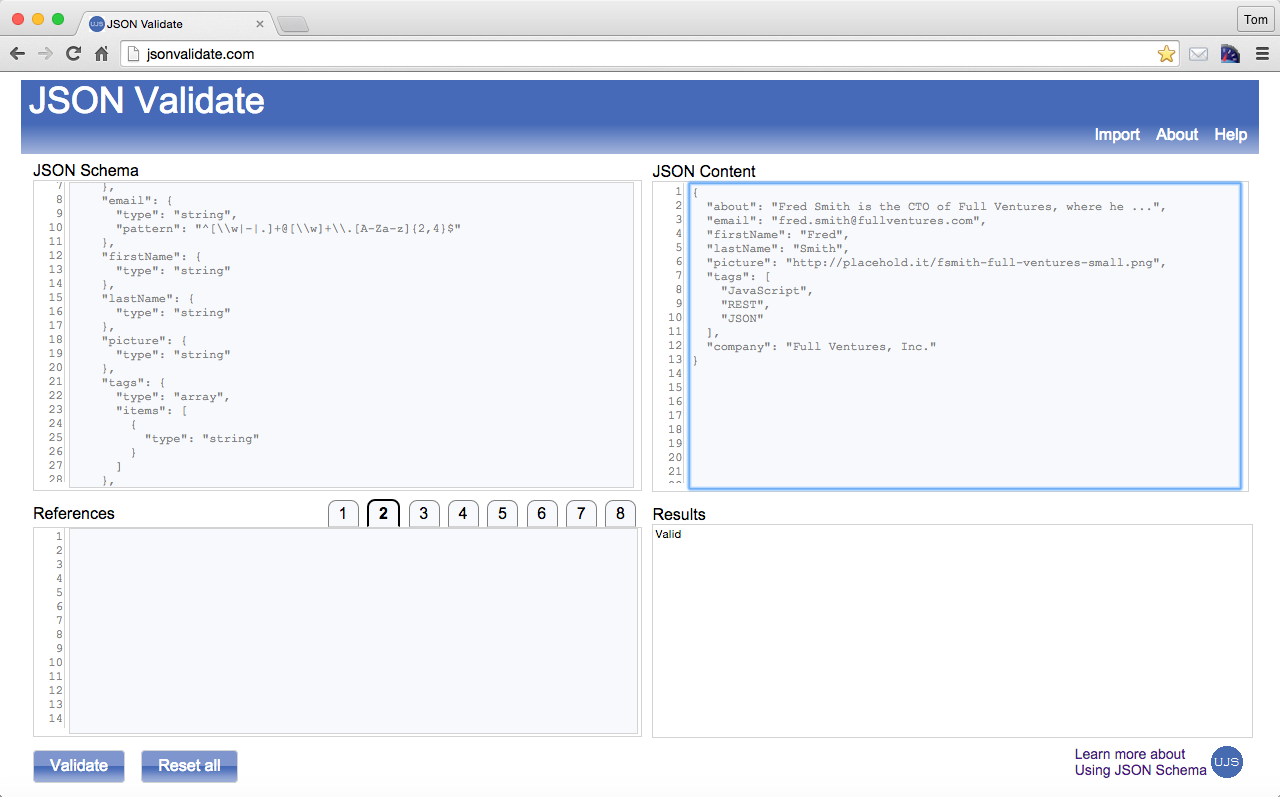

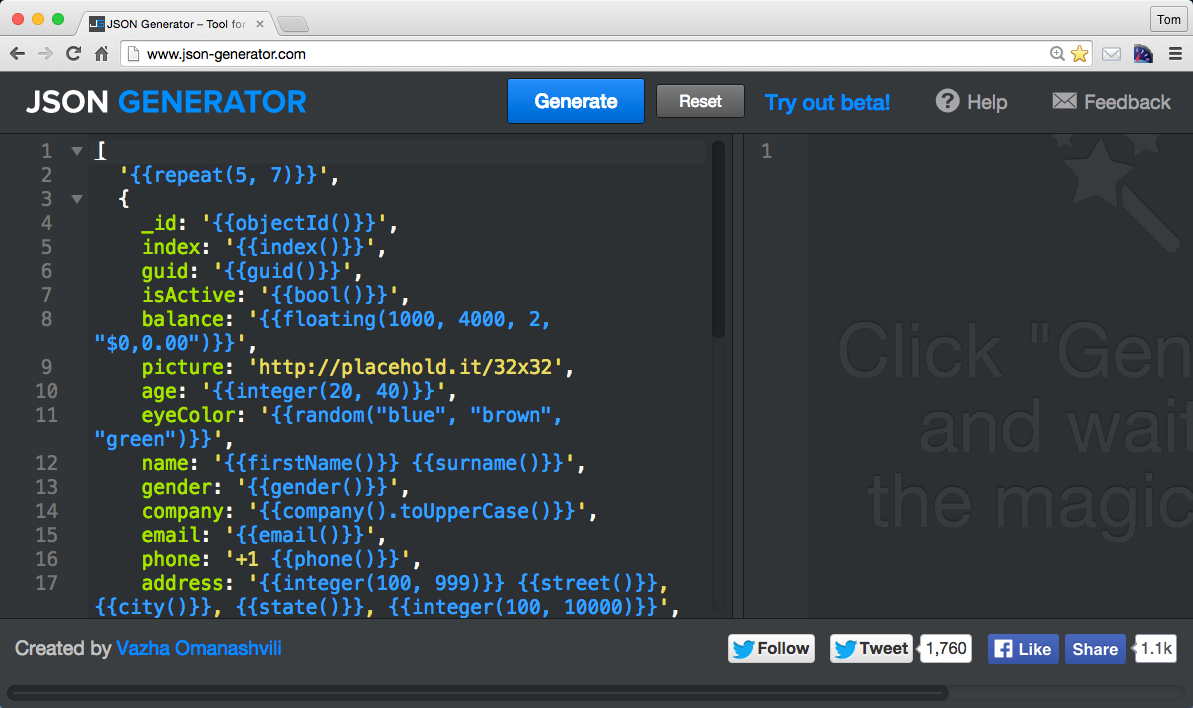

Chapter 5, JSON Schema, helps you structure JSON documents with JSON Schema. Along the way, you’ll generate a JSON Schema and design an API with it.

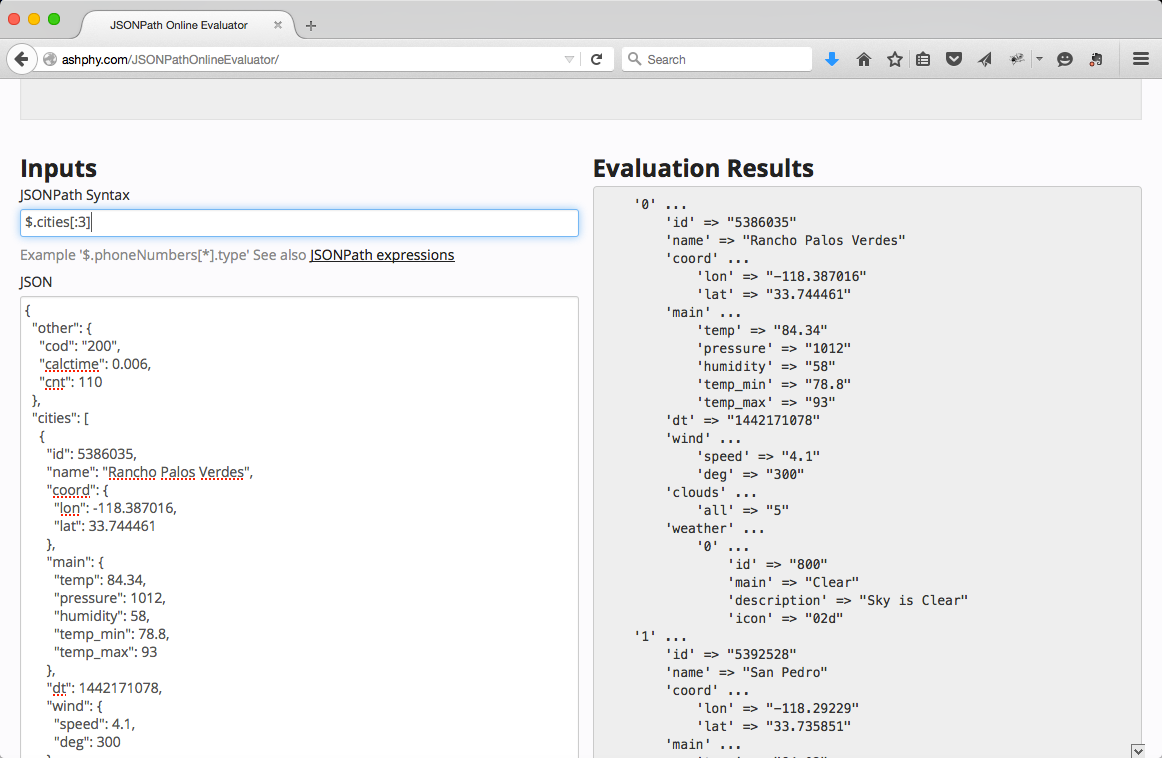

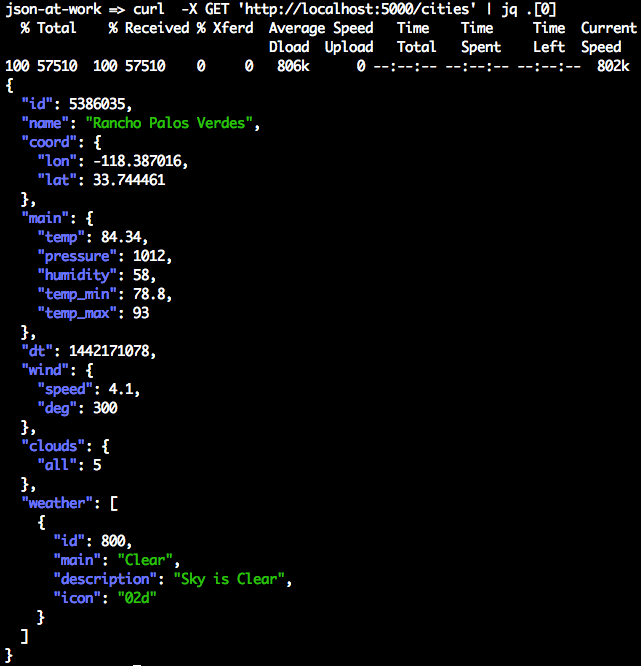

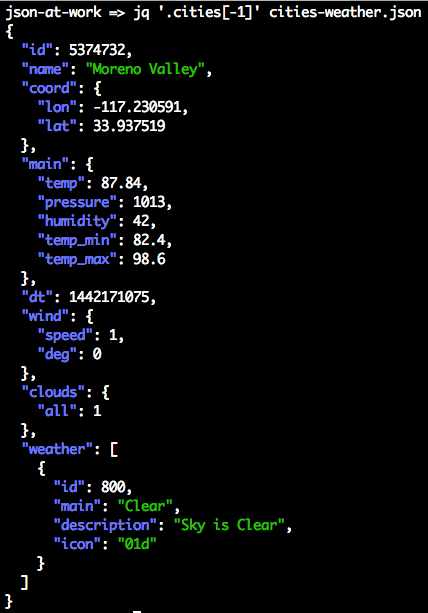

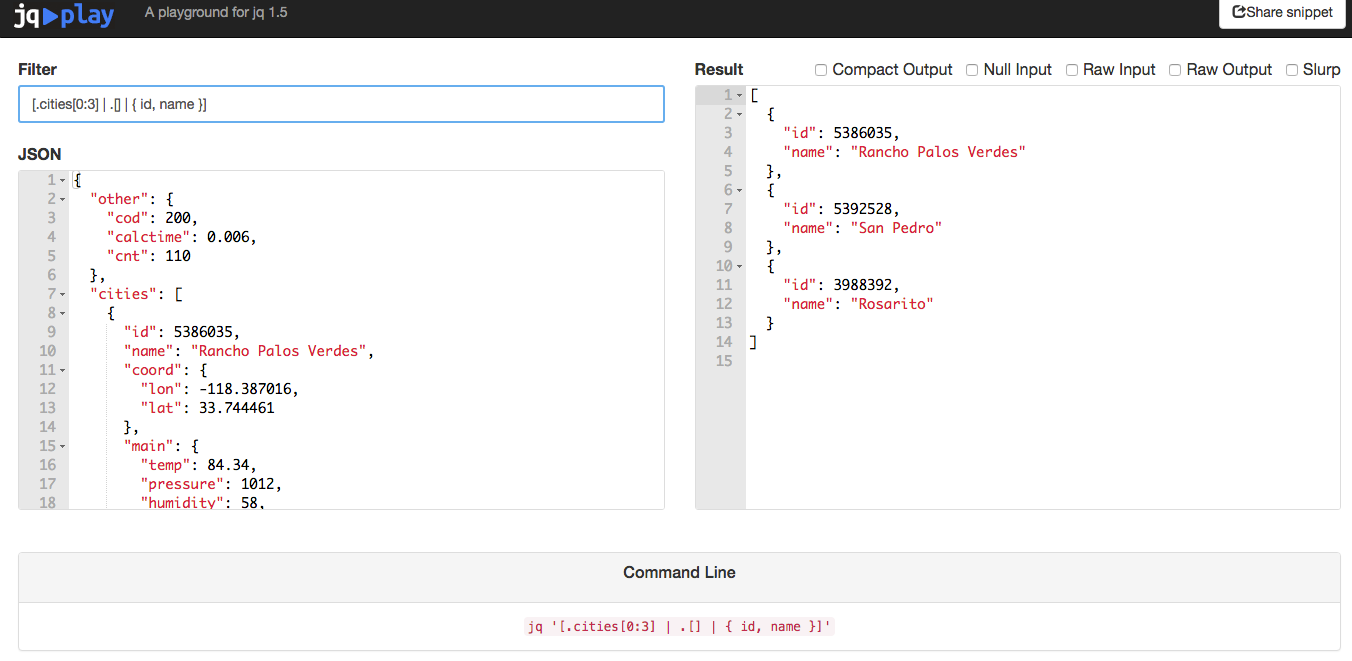

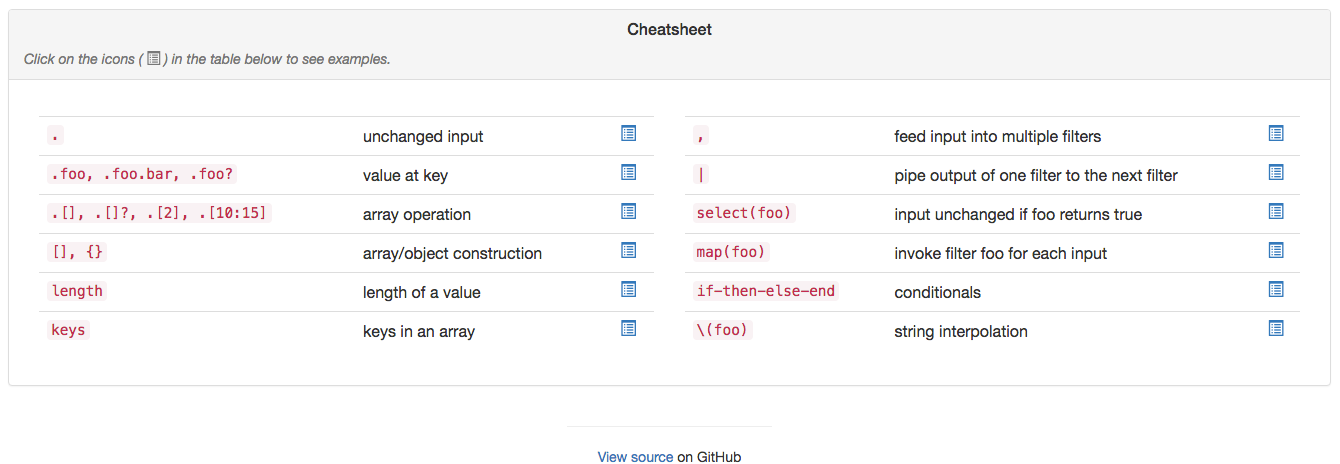

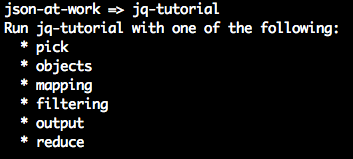

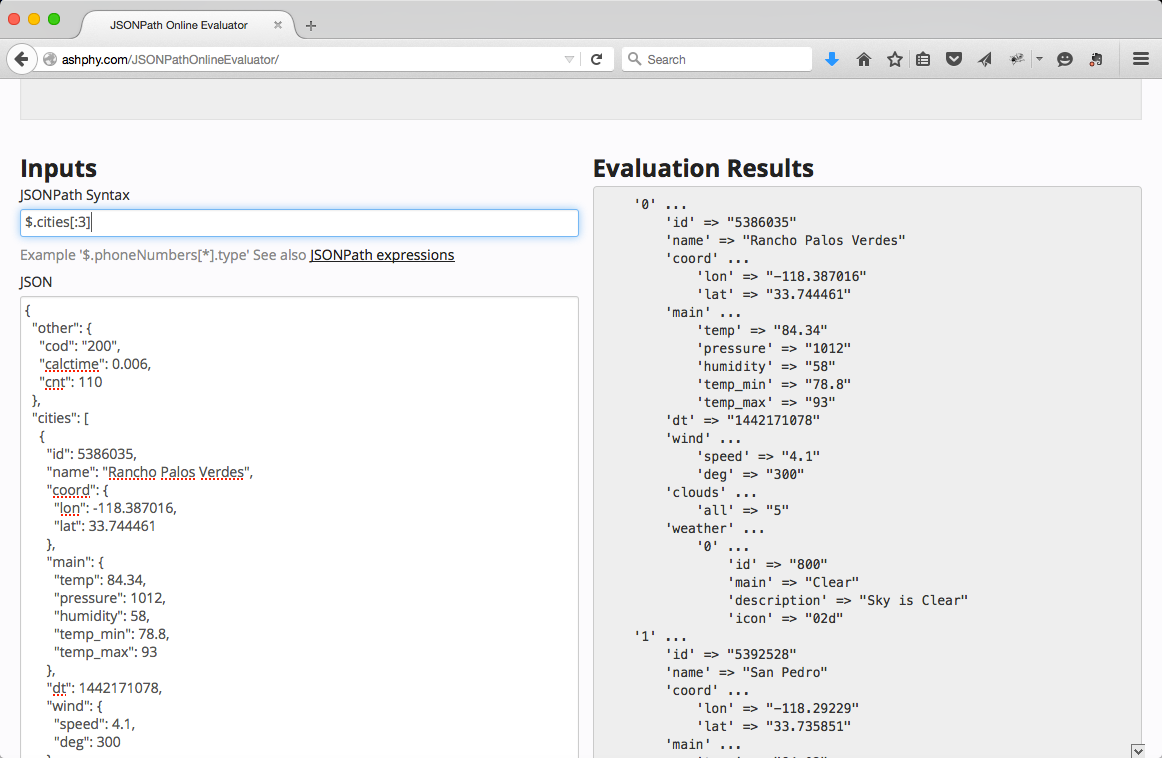

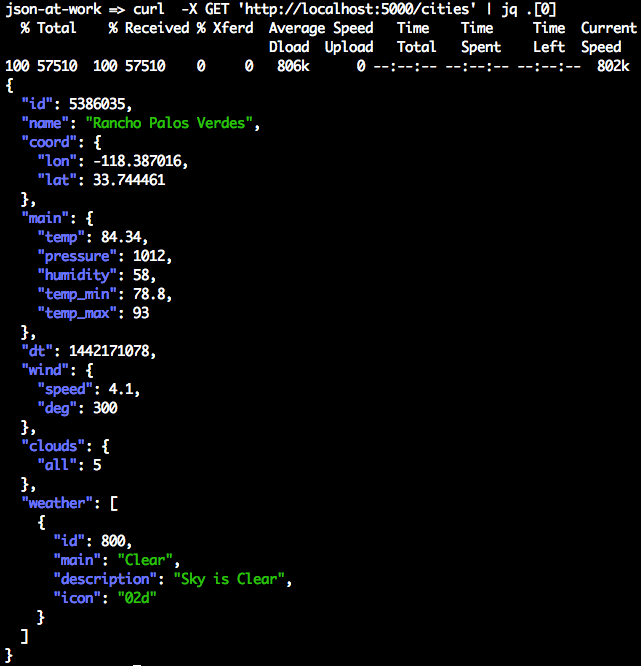

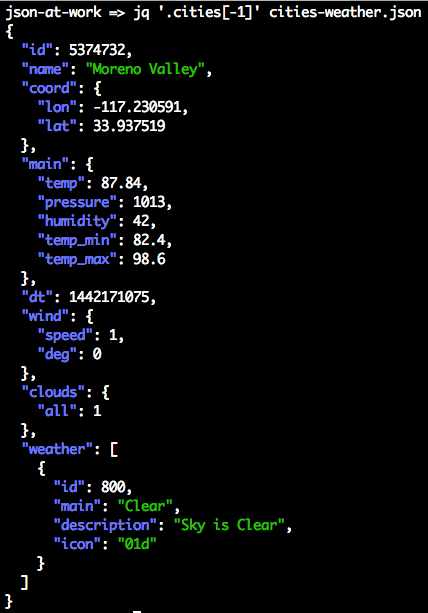

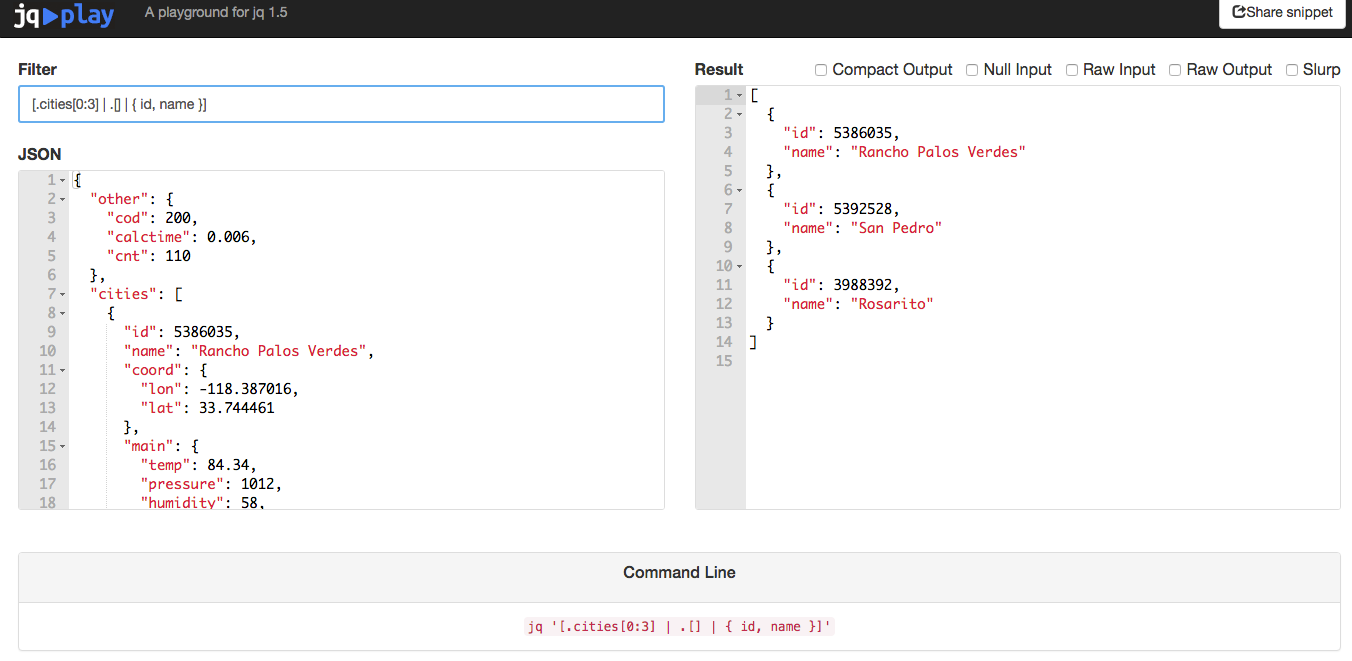

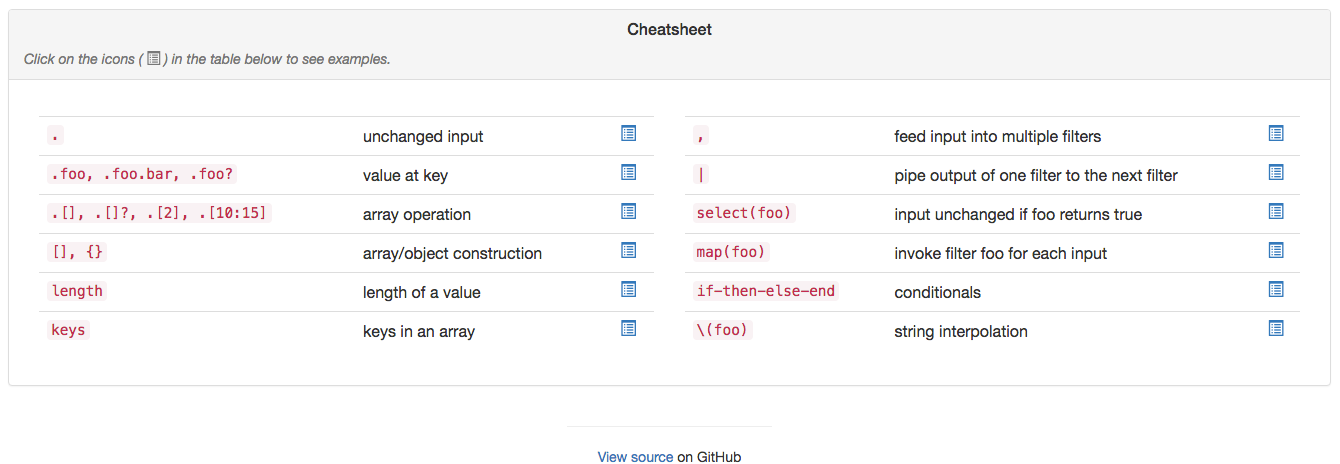

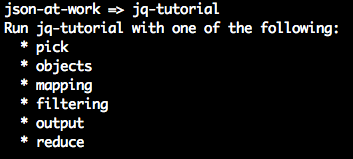

Chapter 6, JSON Search, shows how to search JSON documents with jq and JSONPath.

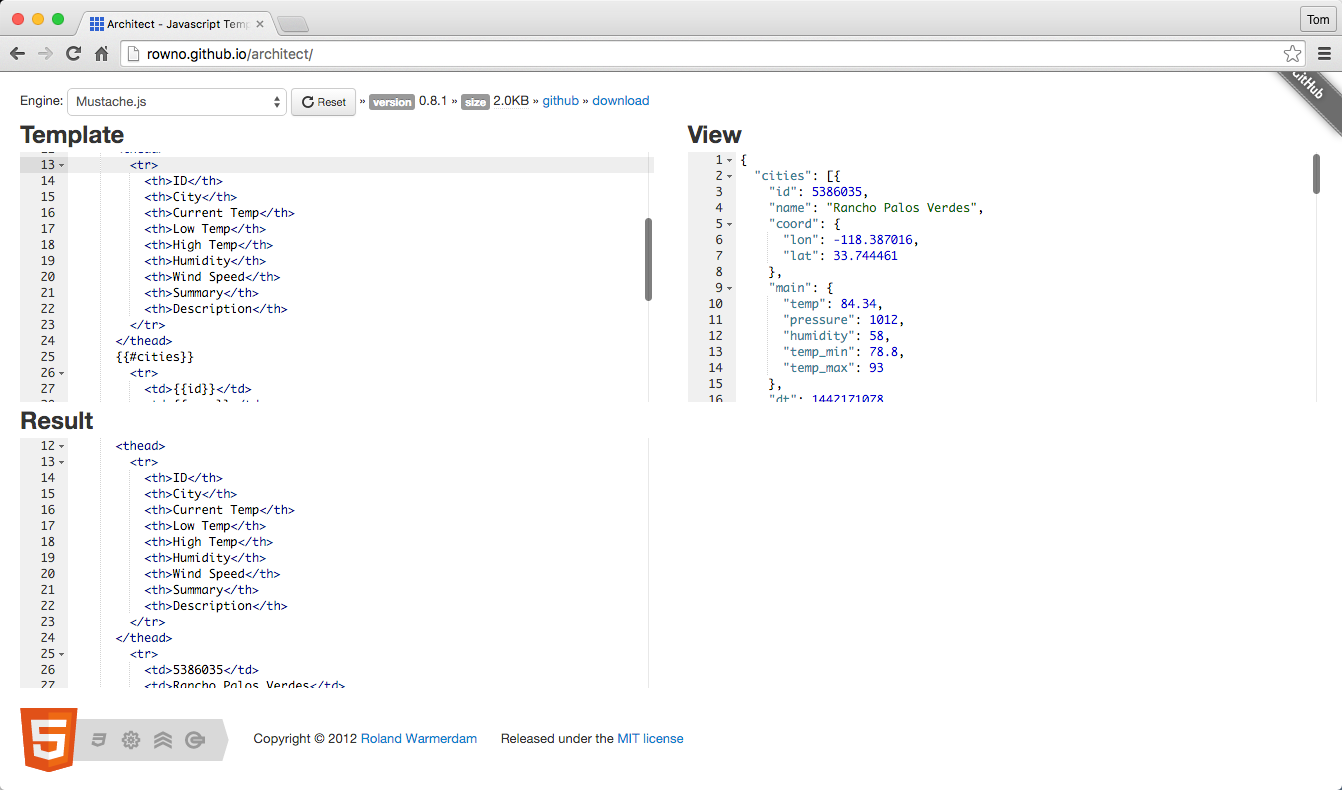

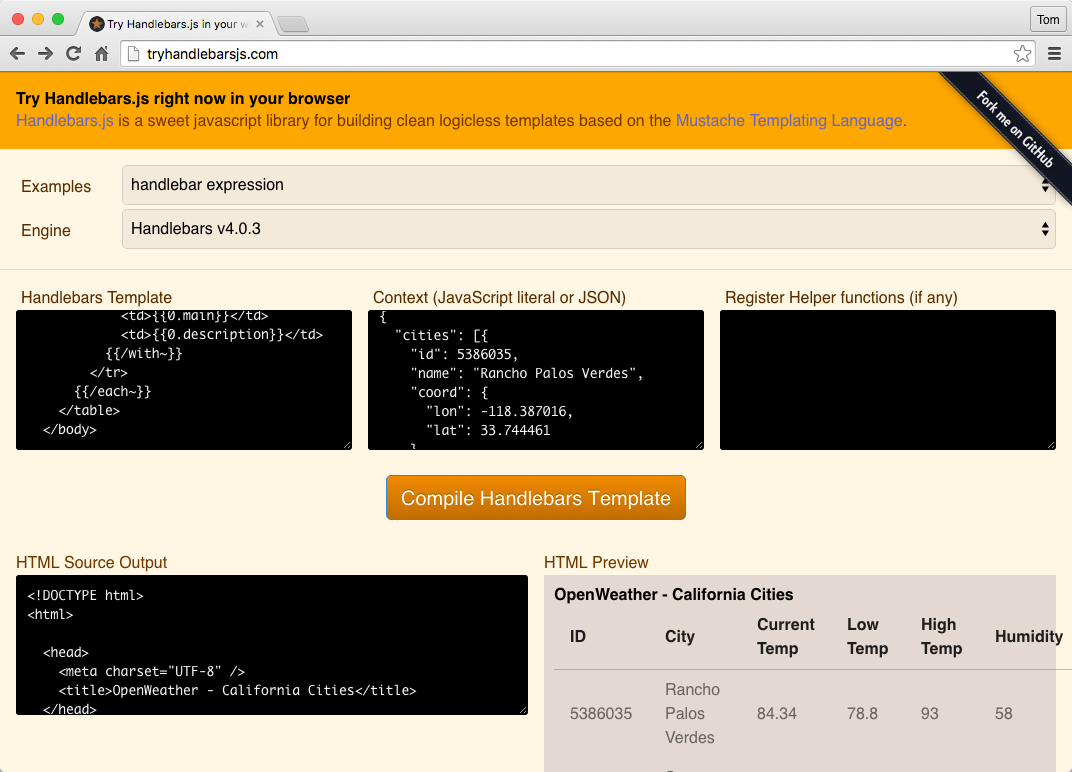

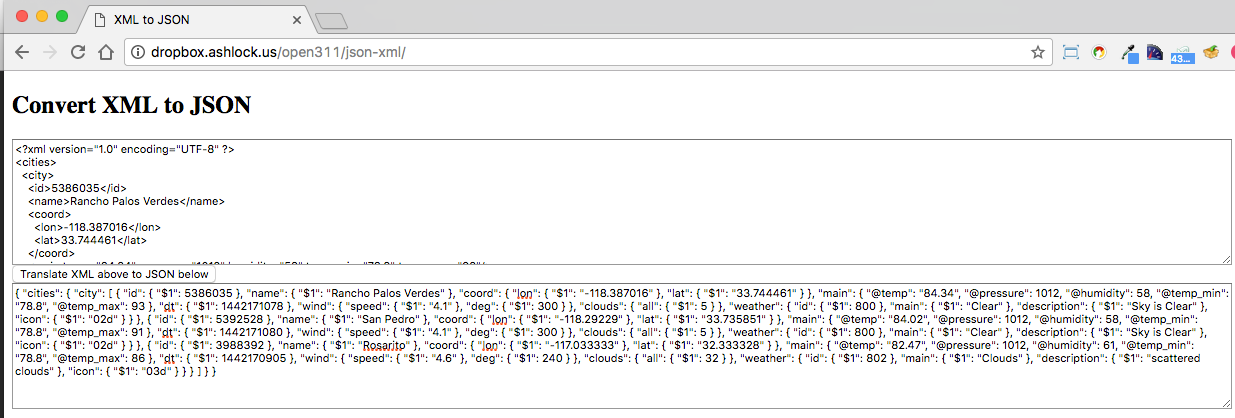

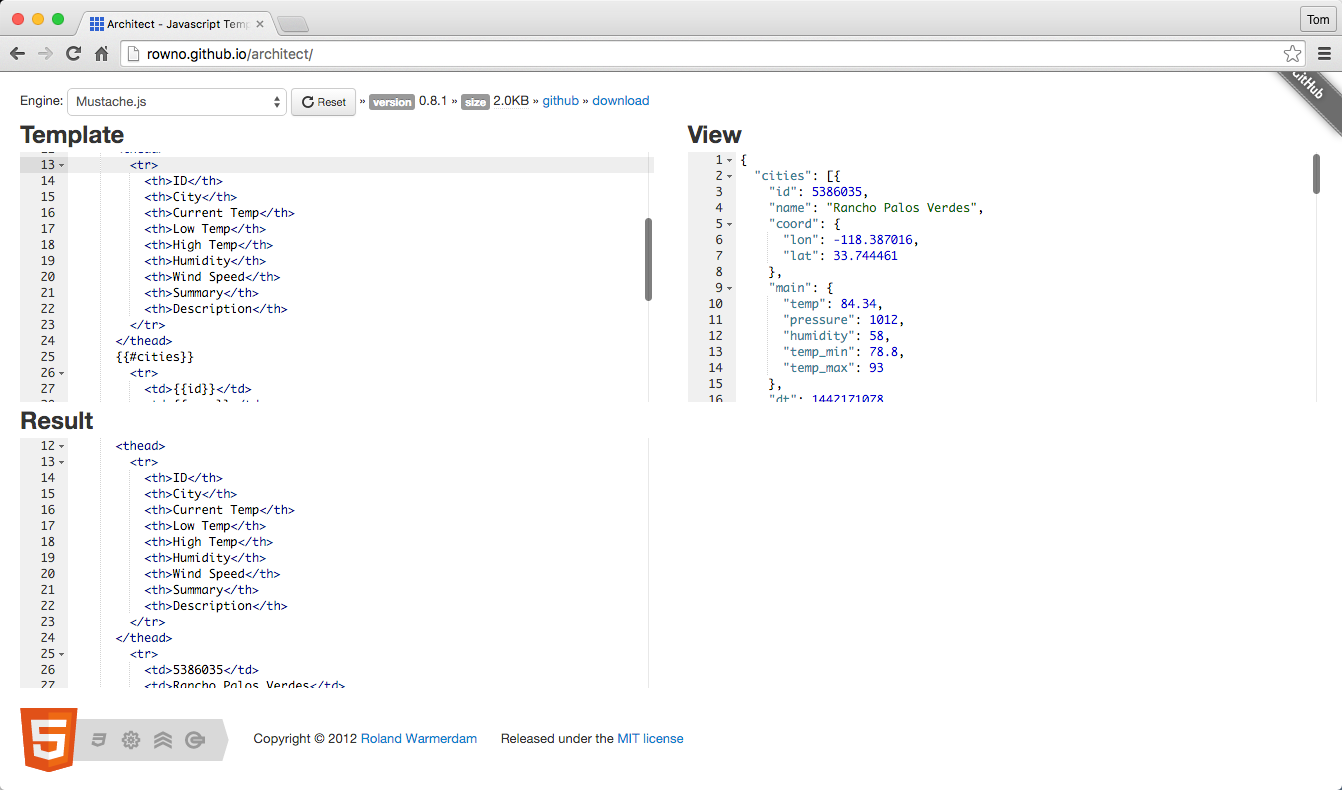

Chapter 7, JSON Transform, provides the tools you’ll need transform a poorly designed JSON document to a better designed/more useful JSON document. Plus, it shows how to convert between JSON and other formats such as XML and HTML.

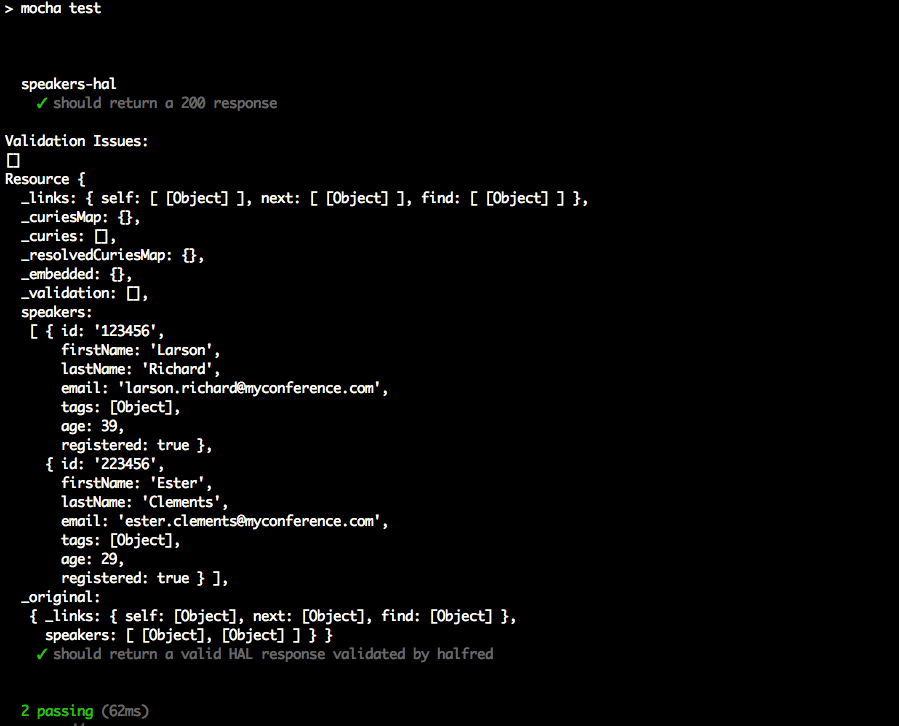

Chapter 8, JSON and Hypermedia, looks at how to use JSON with several well-known Hypermedia formats (e.g.,

HAL and jsonapi).

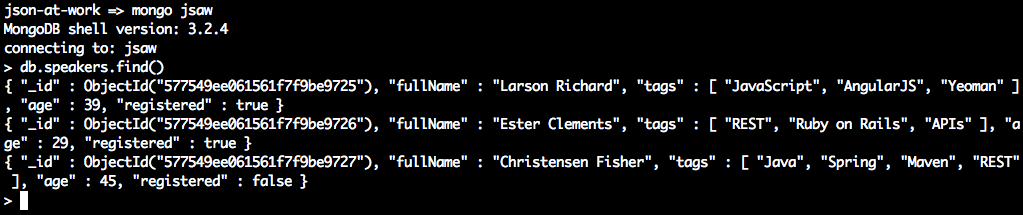

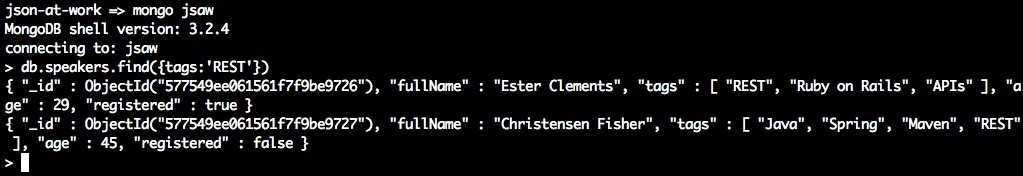

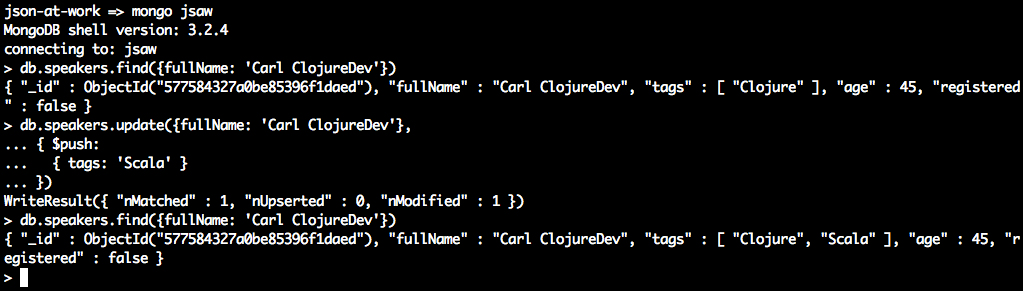

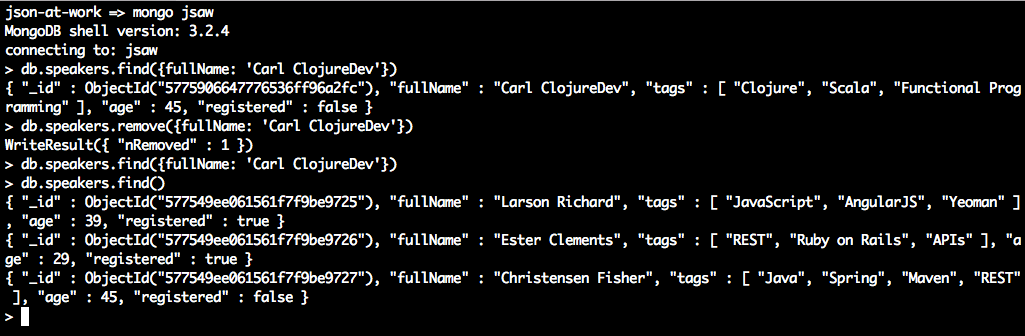

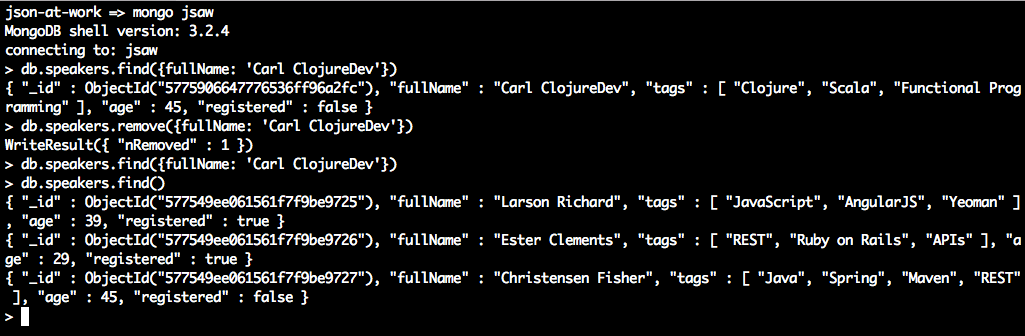

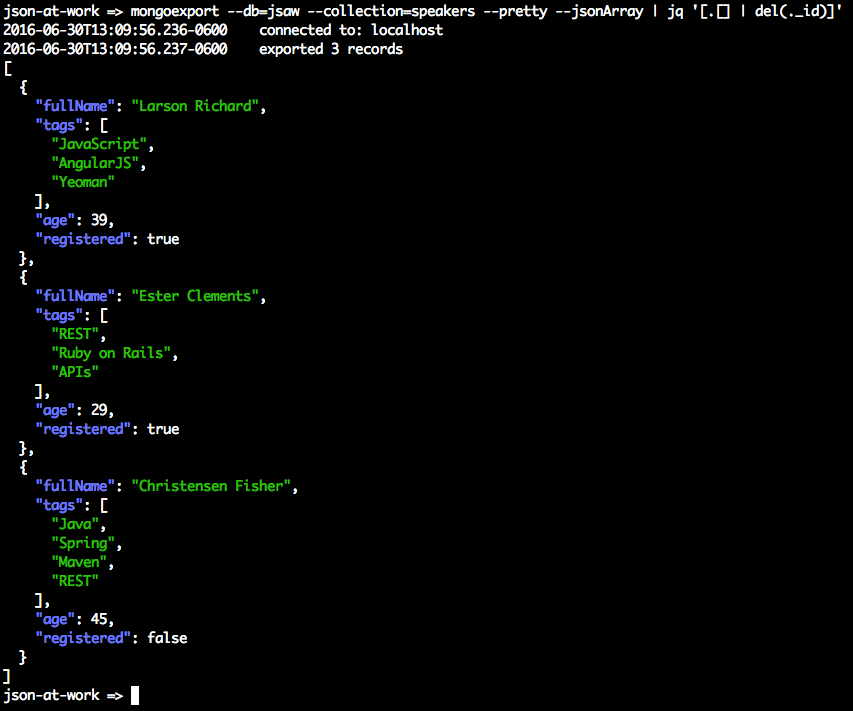

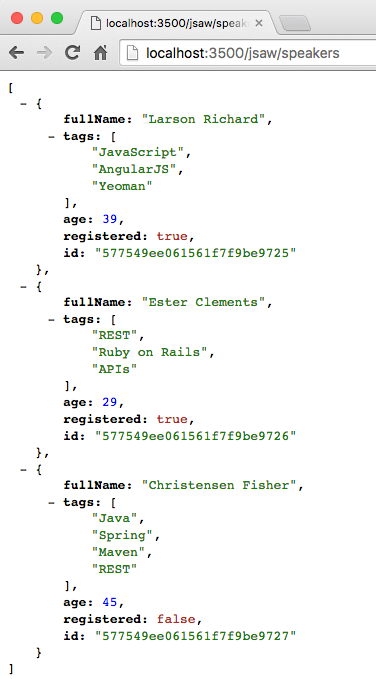

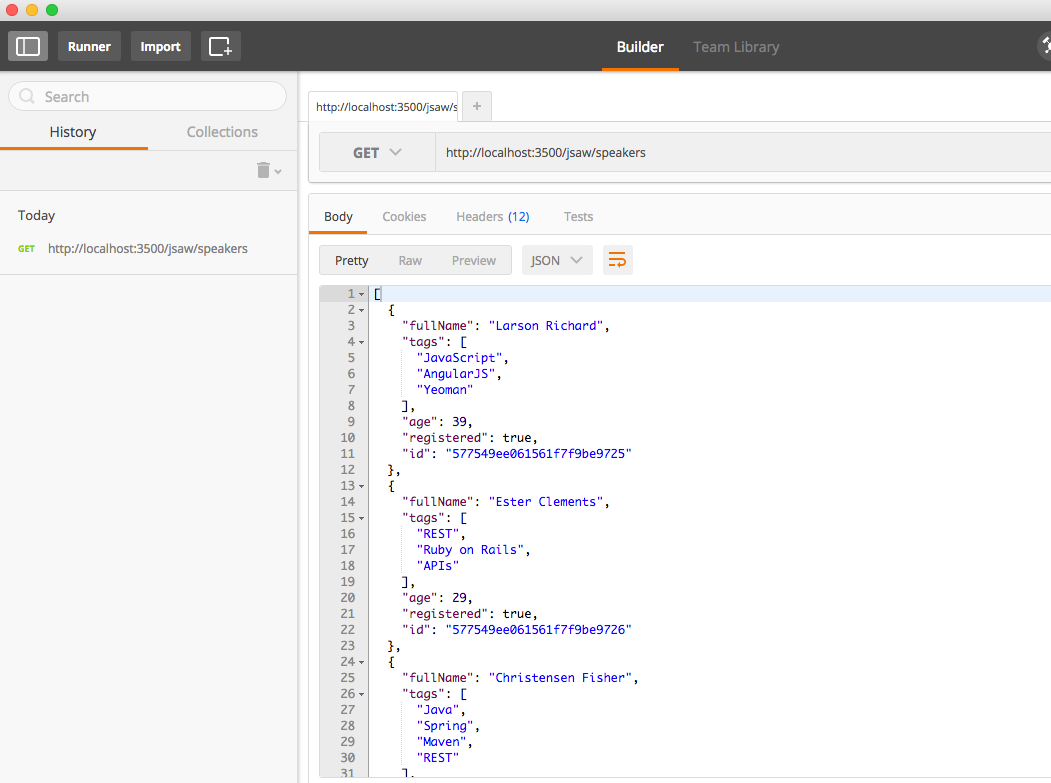

Chapter 9, JSON and MongoDB, shows how to leverage MongoDB to store and access JSON documents.

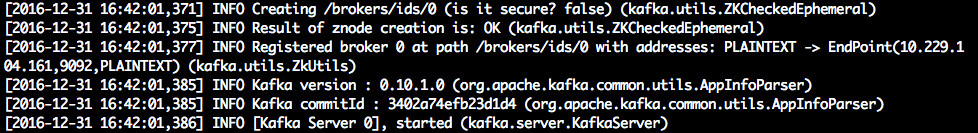

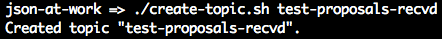

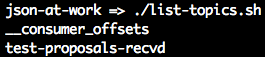

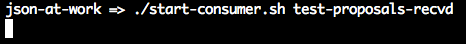

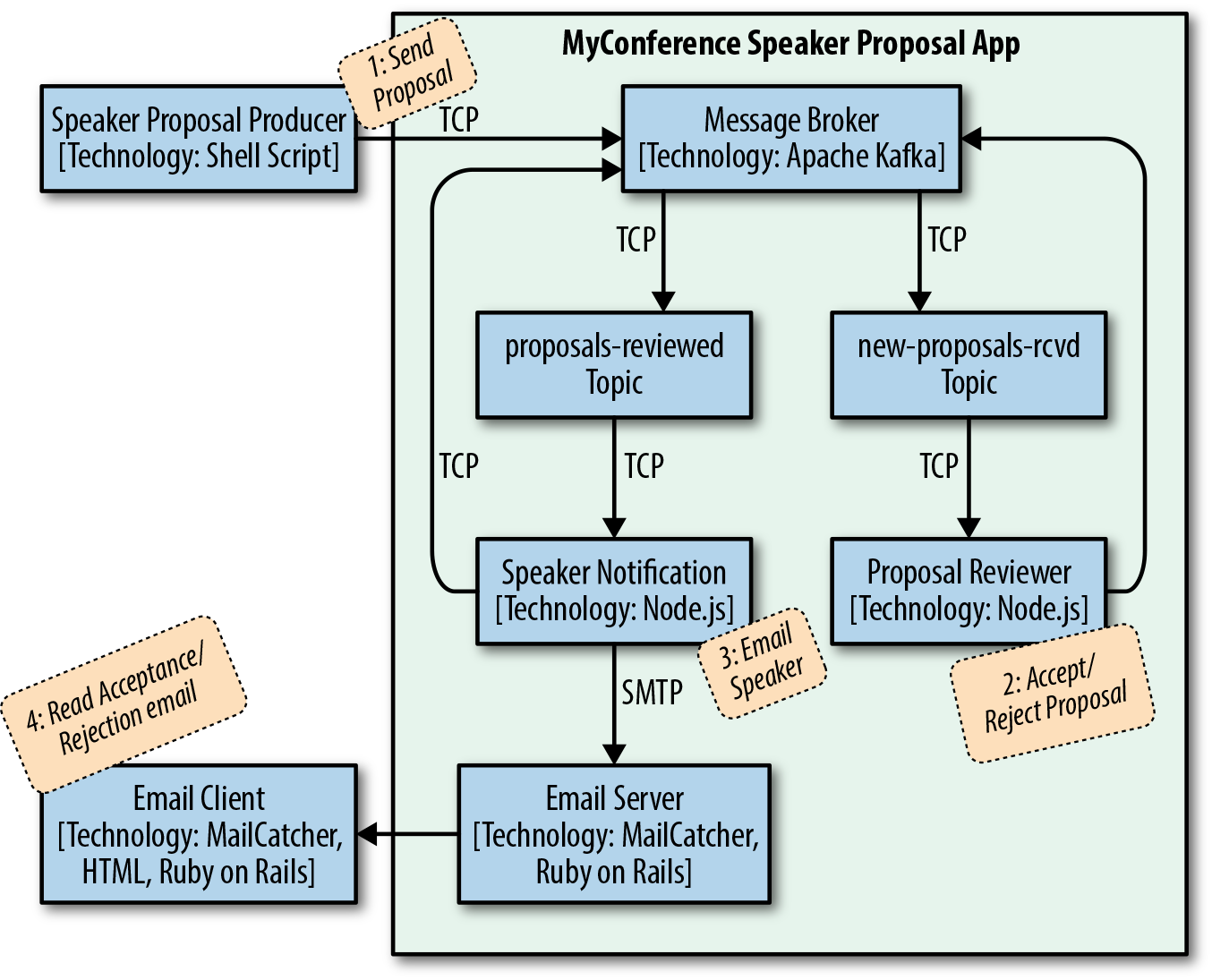

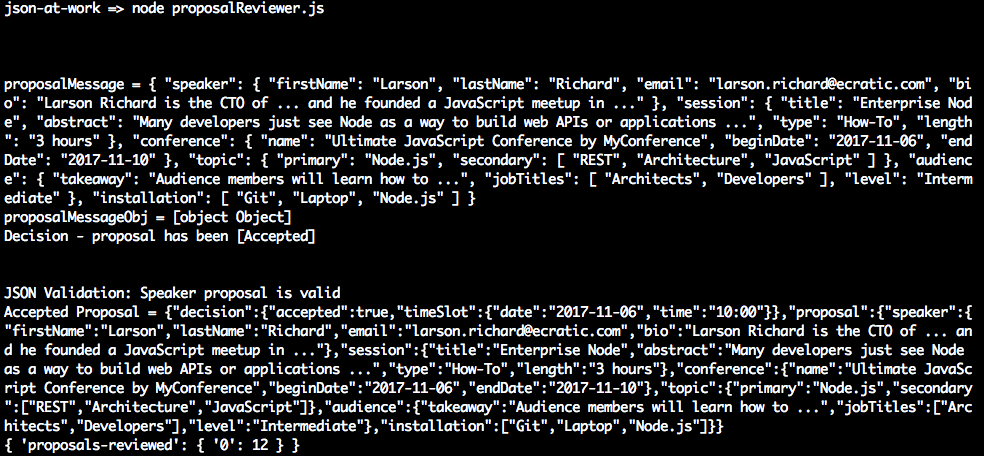

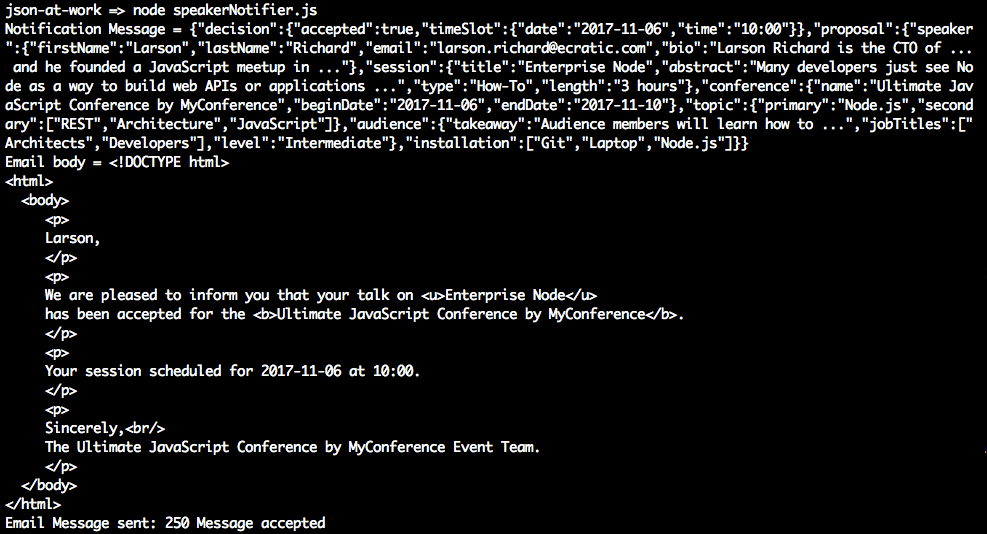

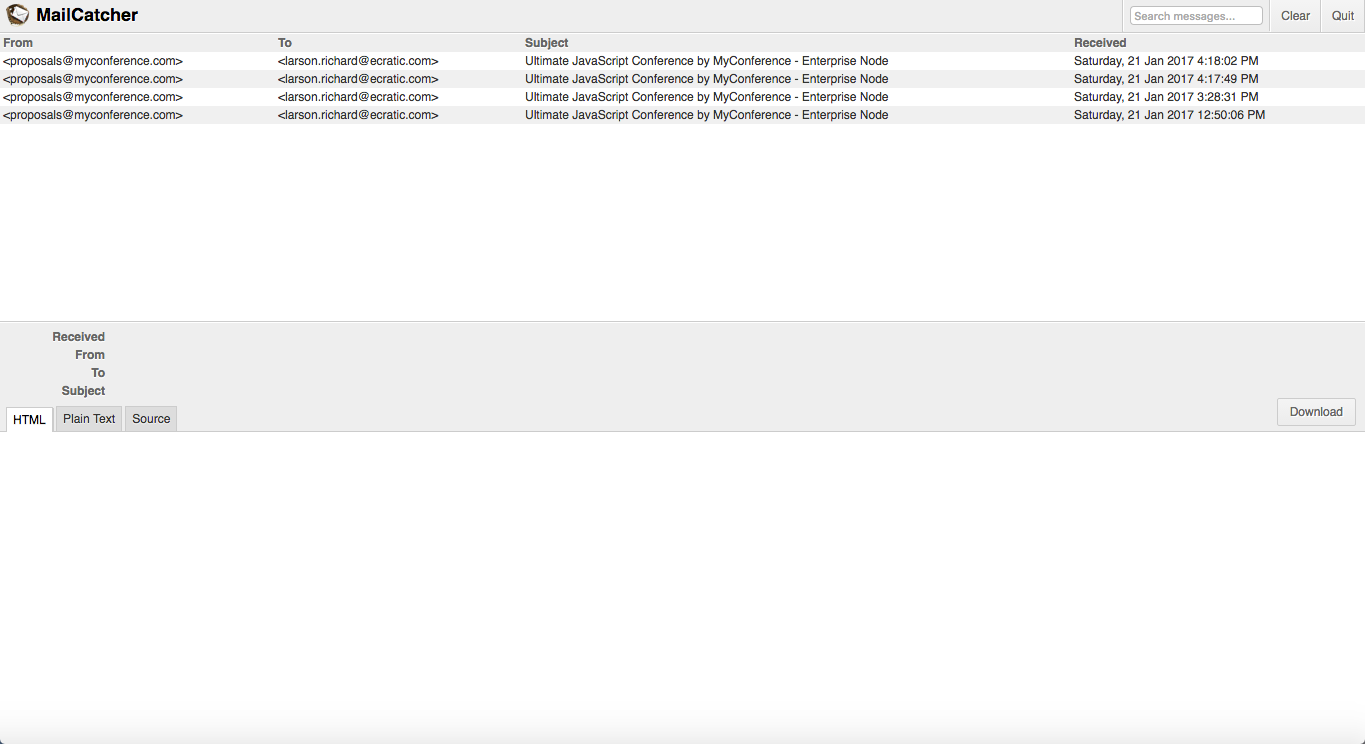

Chapter 10, JSON Messaging with Kafka, describes how to use Apache Kafka to exchange JSON-based messages between services.

Appendix A, Installation Guides, shows how to install the applications you’ll need to run the code examples in this book.

Appendix B, JSON Community, provides further information and links to connect you to the JSON community (e.g., standards and tutorials) and to help you go further with JSON.

All code examples for this book are freely available from the JSON at Work examples GitHub repository.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “JSON at Work by Tom Marrs (O’Reilly). Copyright 2017 Vertical Slice, Inc., 978-1-449-35832-7.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/json-at-work.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

First of all, I’d like to acknowledge Douglas Crockford for creating and standardizing the JSON data format. JSON is the data language of REST and Microservices, and the overall community is indebted to his vision and efforts.

I appreciate my O’Reilly editor, Megan Foley, and my former editor, Simon St. Laurent, for believing in this book and for their patience and guidance on the project. Thanks for sticking with me and helping me throughout the project. I would also like to thank my O’Reilly copy edit team, Nick Adams and Sharon Wilkey, whose diligent work improved the quality of this manuscript.

Thanks to Matthew McCullough and Rachel Roumeliotis from the O’Reilly Open Source Convention (OSCON), Jay Zimmerman from No Fluff Just Stuff (NFJS), and Dilip Thomas from the Great Indian Developer Summit (GIDS) for giving me the chance to speak about JSON and REST at your conferences. It’s always fun to speak at conferences, and I hope to continue doing this well into the future.

I’m grateful to my technical reviewers who provided valuable feedback on this book: Joe McIntyre, David Bock, Greg Ostravich, and Zettie Chinfong. I would also like to thank the following people who helped shape and mold my ideas on how to talk about JSON: Matthew McCullough, Scott Davis, Cristian Vyhmeister, Senthil Kumar, Sean Pettersen, John Gray, Doug Clark, Will Daniels, Dan Carda, and Peter Piper.

The Colorado Front Range technical community is world class, and I’ve had fun presenting at the following user groups to help refine my material:

HTML5 Denver

Denver Open Source User Group (DOSUG)

Colorado Springs Open Source User Group (CS OSUG)

Denver Java User Group (DJUG)

Boulder Java User Group (BJUG)

BoulderJS Meetup

Thanks to my friends in the Toastmasters community who encouraged me, believed in me, and pushed me to finish the book: Darryle Brown, Deborah Frauenfelder, Elinora Reynolds, Betty Funderburke, Tom Hobbs, Marcy Brock, and many, many others. You have inspired me to communicate clearly, to “Lift as You Climb,” and to “Travel Beyond.”

There is an amazing JSON community on the internet. Much of this book is based on the great work that you’ve done and continue to do. You’ve inspired me to tell your story and to connect the dots.

To my late parents, Al and Dorene Marrs, who loved me and always believed in me and supported me—I know you’re in a better place. You inspired me to be adaptable, to innovate, and to work hard. You always encouraged me to do my very best. Thank you for everything you did for me.

Finally, to my beautiful wife, Linda, and my daughter, Abby—I love you. Thanks for your patience with me while I spent my evenings and weekends on the manuscript and code.

The JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) data format enables applications to communicate over a network, typically through RESTful APIs. JSON is technology-agnostic, nonproprietary, and portable. All modern languages (e.g., Java, JavaScript, Ruby, C#, PHP, Python, and Groovy) and platforms provide excellent support for producing (serializing) and consuming (deserializing) JSON data. JSON is simple: it consists of developer-friendly constructs such as Objects, Arrays, and name/value pairs. JSON is not limited to Representational State Transfer (REST); it also works with the following:

Node.js (which stores project metadata in package.json)

NoSQL databases such as MongoDB (see Chapter 9)

Messaging platforms such as Kafka (see Chapter 10)

In the early days, REST’s detractors derided RESTful Web Services as being non-standard, but (just like HTTP) JSON is in fact a standard. Both the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and Ecma International (formerly the European Computer Manufacturers Association, or ECMA) have recognized JSON as a standard. Douglas Crockford originally created JSON in 2001, and initially standardized it in 2006 under RFC 4627 through the IETF; see the JSON specification. In the fall of 2013, Ecma International also standardized JSON under ECMA 404; see their JSON specification. With Ecma recognition (per Douglas Crockford; see his Google+ page), JSON is now considered a formal international data processing standard.

In March 2014, Tim Bray published an updated version of Douglas Crockford’s original standard as IETF RFC 7158 and RFC 7159 to correct errata with the original IETF 4627 standard (thus rendering it obsolete).

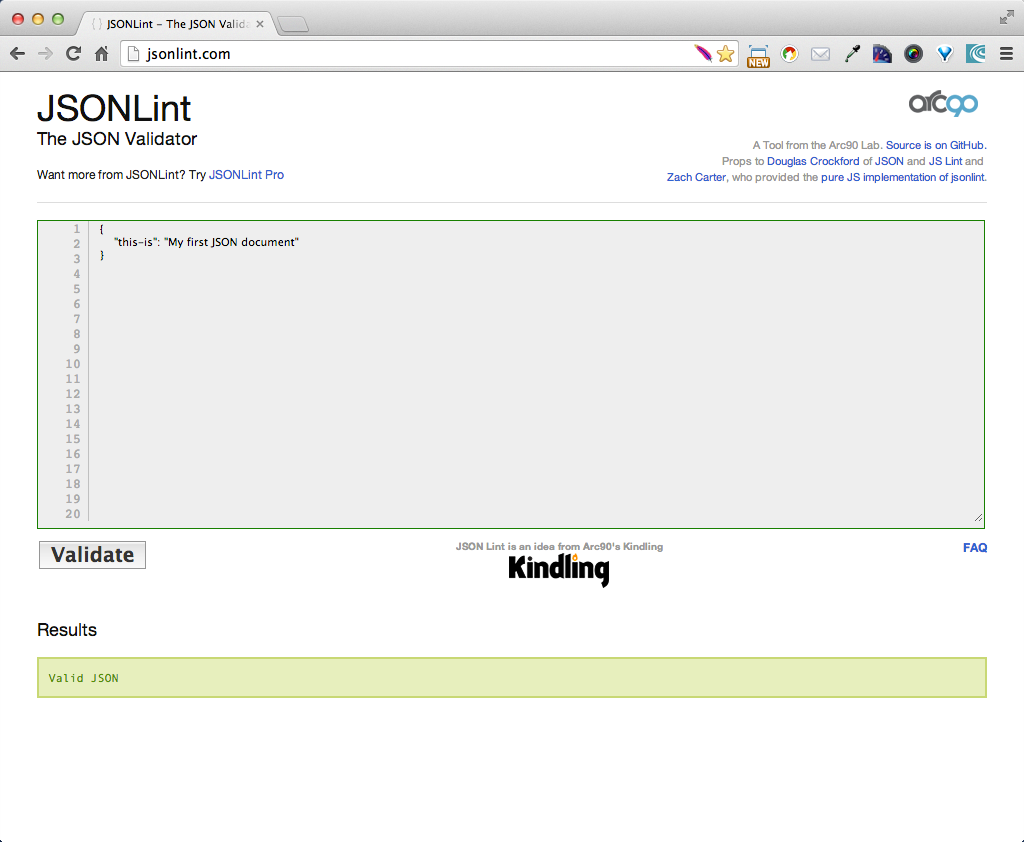

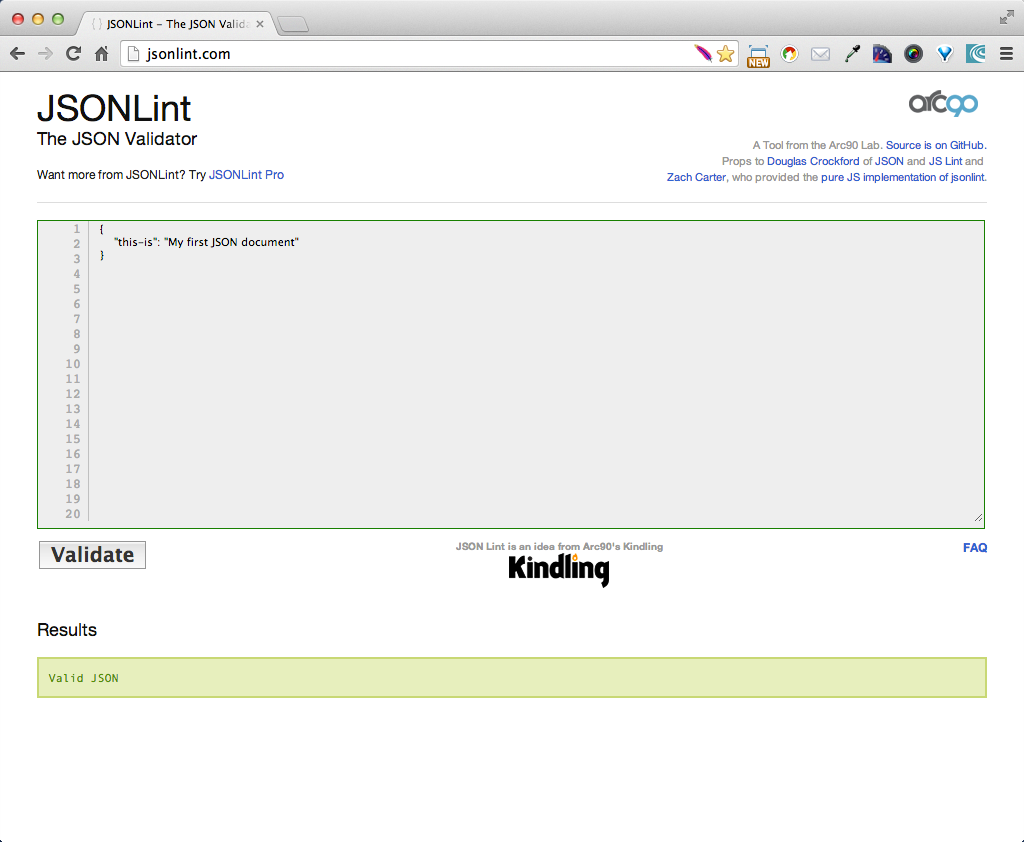

Before we go further, let’s look at a small JSON sample. Example 1-1 shows a simple JSON document.

{"thisIs":"My first JSON document"}

A valid JSON document can be either of the following:

An Object surrounded by curly braces, { and }

An Array enclosed by brackets, [ and ]

The preceding example shows an Object that contains a single key/value pair, where the key,

"thisIs", has a value of "My first JSON document".

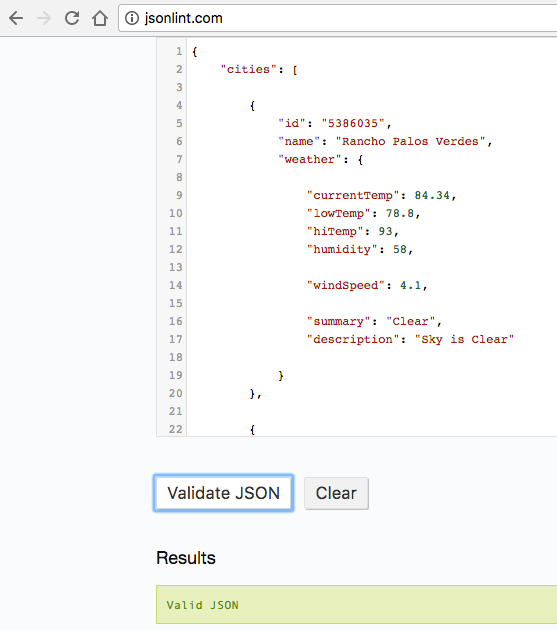

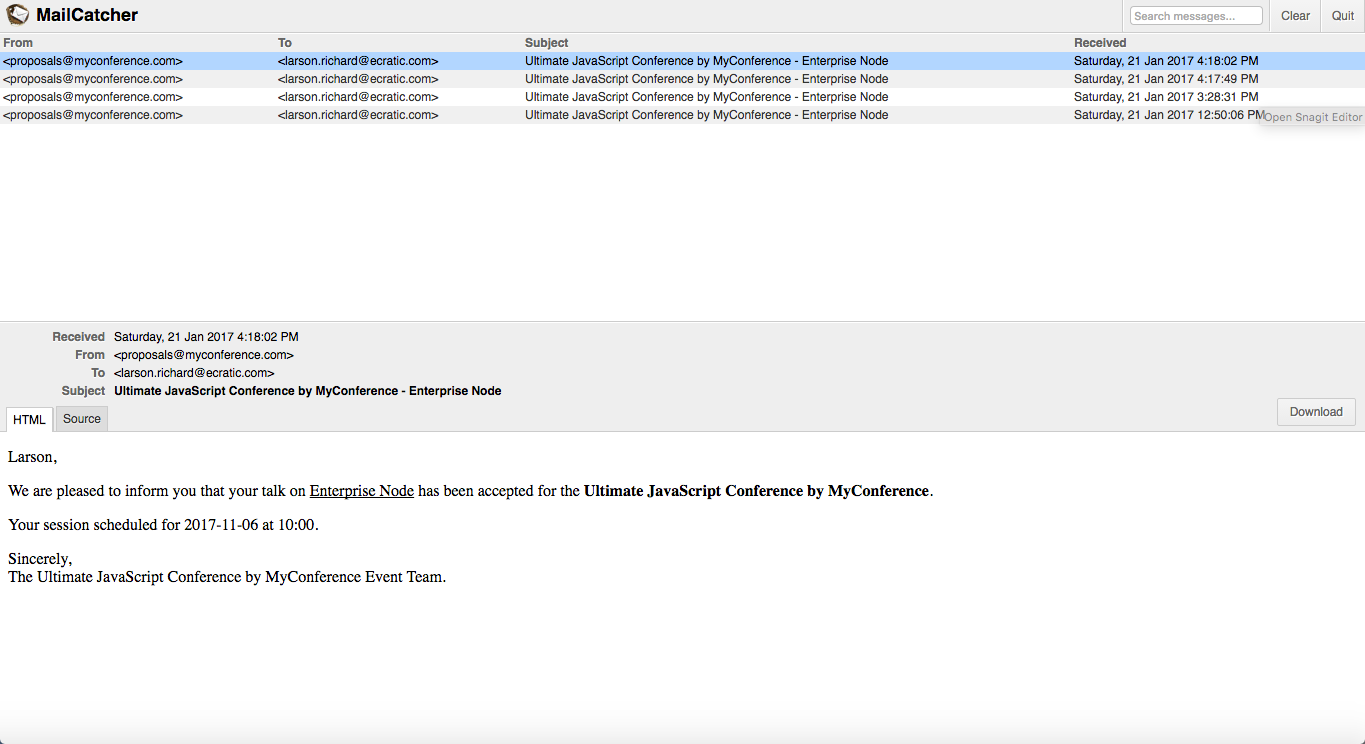

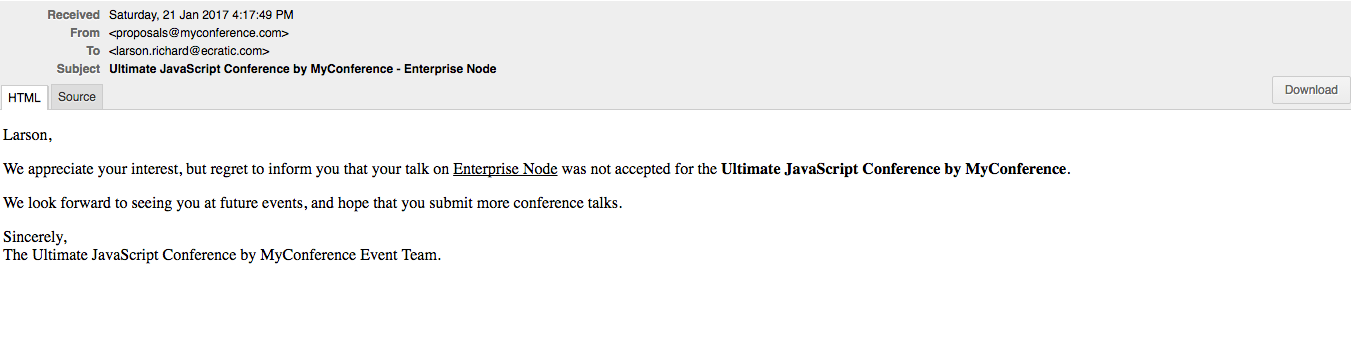

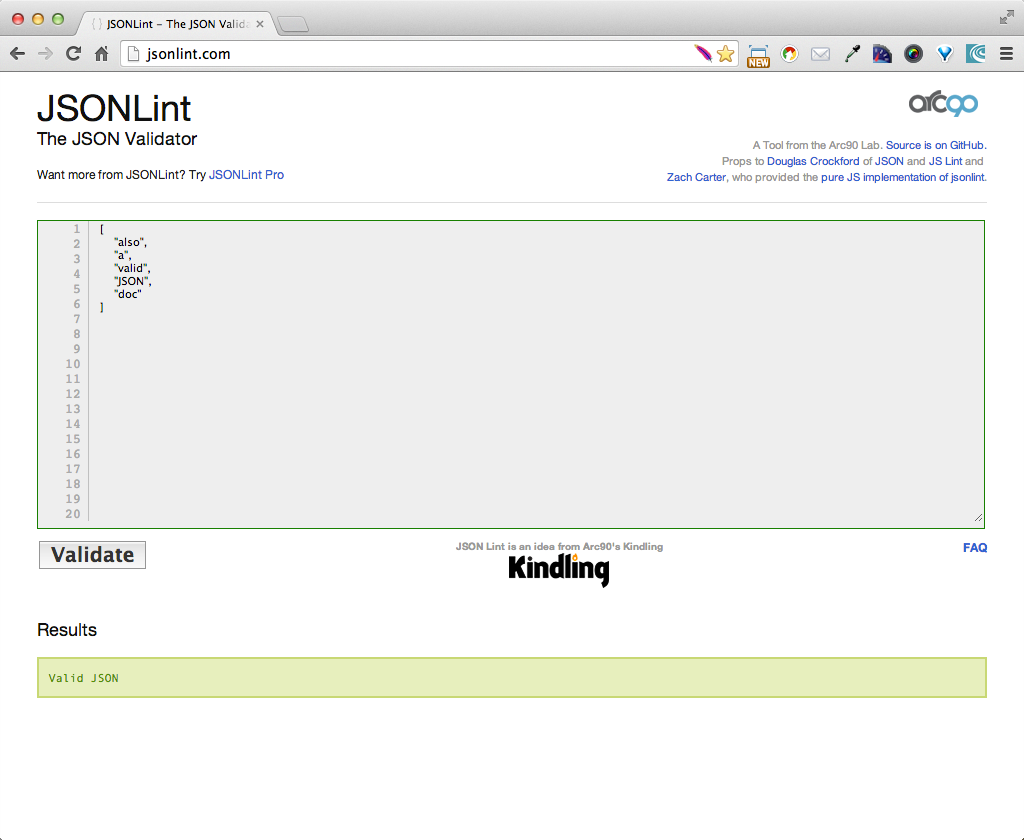

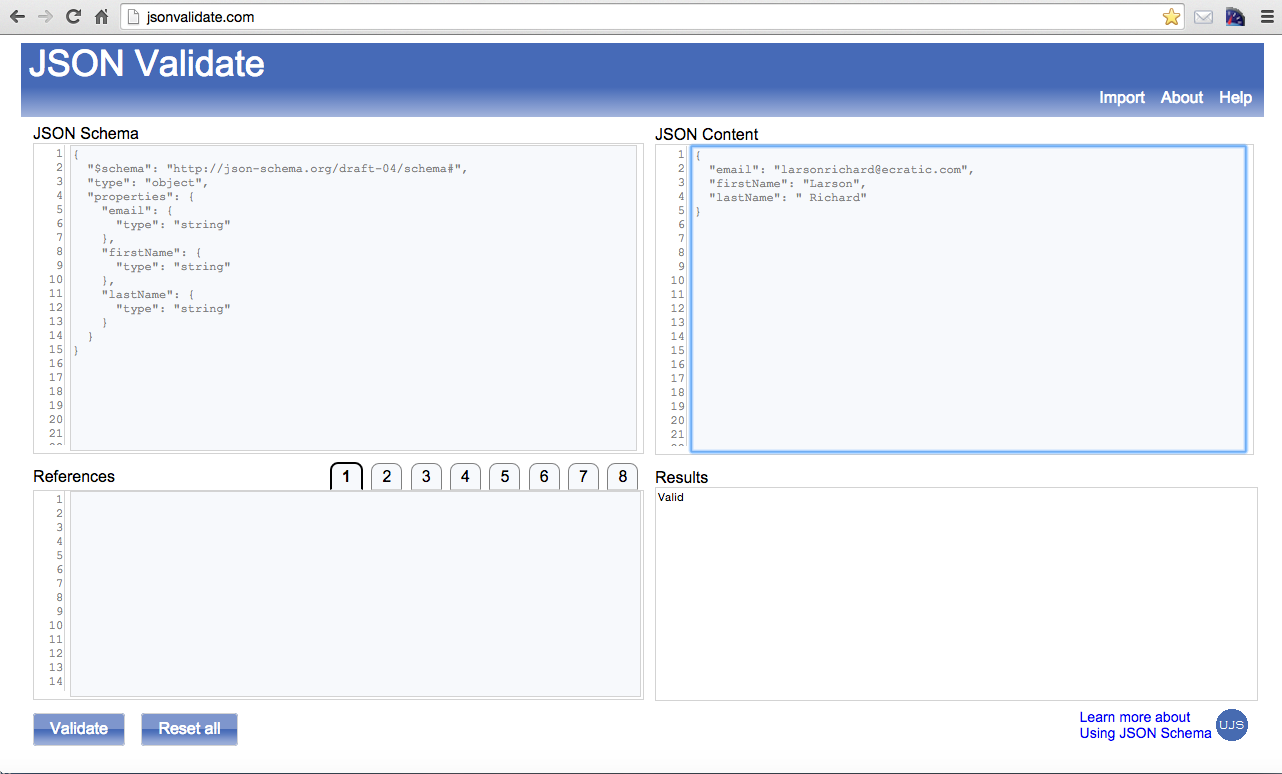

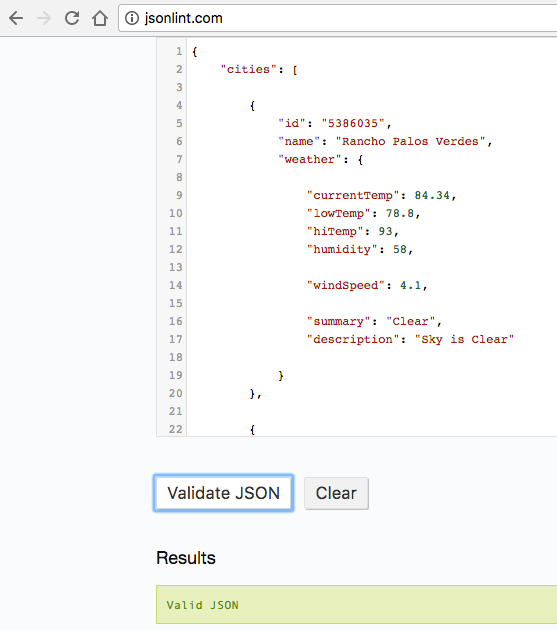

Just to keep us honest, let’s validate this document by using JSONLint. Just paste the text into the text area, click the Validate button, and you should see the page in Figure 1-1.

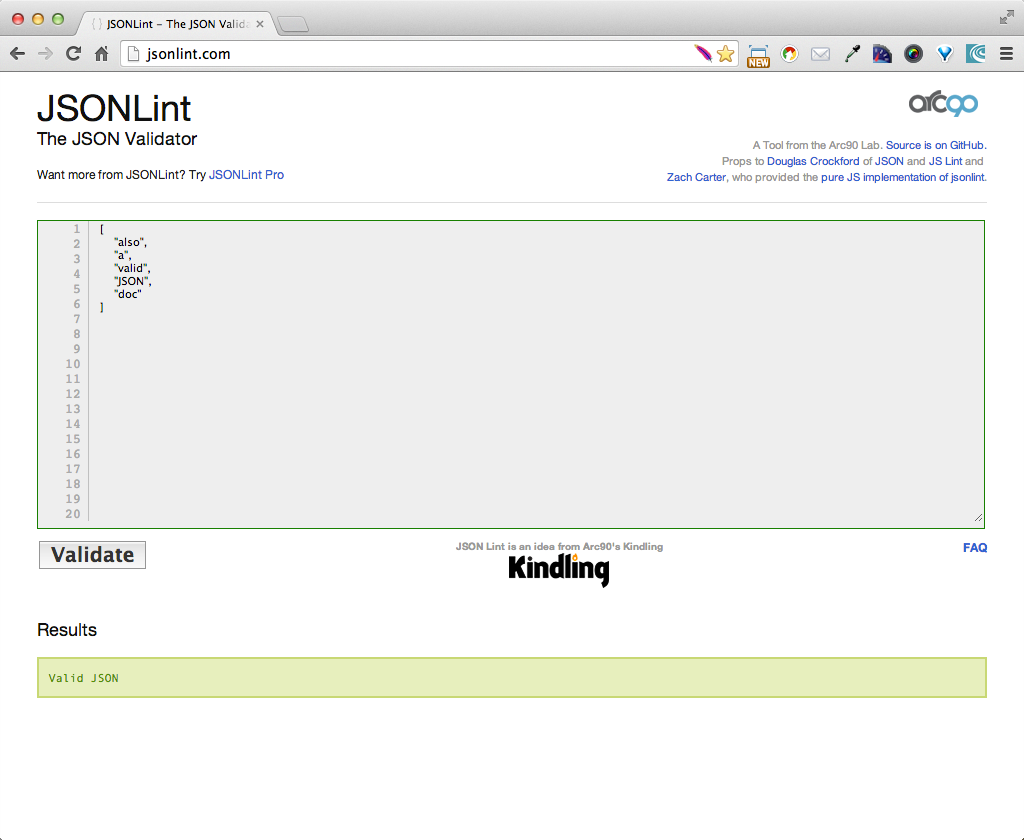

Example 1-2 presents a simple JSON Array.

["also","a","valid","JSON","doc"]

In JSONLint, paste the JSON Array into the text area, and click the Validate button, and you should get the result shown in Figure 1-2.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. We’ll cover JSON syntax more thoroughly in “Core JSON”.

Although standardization through Ecma International and the IETF has helped JSON gain industry acceptance, other factors have popularized JSON:

The explosive growth of RESTful APIs based on JSON

The simplicity of JSON’s basic data structures

The increasing popularity of JavaScript

JavaScript’s resurgence is boosting JSON’s popularity. Over the past several years, we have seen the rise of JavaScript as a first-class development language and environment. This ecosystem includes platforms such as Node.js, and Mode/View/Controller (MVC) frameworks such as AngularJS, React, Backbone, and Ember. There has also been a tremendous increase in the number of books and websites showing best practices in JavaScript Objects and Patterns. According to Douglas Crockford, JSON is a subset of JavaScript’s Object Literal notation, and fits seamlessly into JavaScript development.

Thousands of RESTful APIs leverage JSON. A sample list of popular JSON-based RESTful APIs includes the following:

Salesforce

GitHub

DropBox

Tumblr

Amazon Web Services (AWS)

To see the thousands of available JSON-based REST APIs available, visit ProgrammableWeb, and do a search on REST and JSON. Then, take several weeks to review the results.

JSON is simple and is gradually replacing XML as the primary data interchange format on the internet. JSON is easy to read, and its structures easily translate to concepts well understood by software developers—Arrays, Objects, and name/value pairs. We don’t have to scratch our heads or argue anymore about what should be an Element or an Attribute. Objects and their data members are a much better fit for Object-Oriented (OO) design and development. A document formatted in JSON is usually smaller than its XML equivalent, because JSON has less overhead and is more compact. This is due to the lack of begin and end tags surrounding each data element. So, at an enterprise level, JSON is more efficient to process than XML, because JSON documents can be transmitted over a network and processed faster than their XML counterparts.

Although Douglas Crockford initially intended JSON to be a data interchange format (typically with REST), JSON is now finding a home in configuration files for widely used products such as Node.js and Sublime Text. Node.js has a package.json file that it uses to define its standard npm package structure; we’ll cover this in Chapter 2. Sublime Text, a popular IDE in the web development community, uses JSON to configure its appearance along with its package managers.

The Core JSON data format includes JSON Data and Value Types. We’ll also cover versions, comments, and File/MIME Types.

JSON has the following core Data Types:

Consists of a key (a data attribute) and a value.

Now that we’ve covered basic definitions, let’s dig deeper into each Data Type.

Example 1-3 shows some sample name/value pairs.

{"conference":"OSCON","speechTitle":"JSON at Work","track":"Web APIs"}

Name/value pairs have the following characteristics:

Each name (e.g., "conference")

Is on the left side of the colon (:)

Is a String, and must be surrounded by double quotes

The value (e.g., "OSCON") is to the right of the colon. In the preceding example, the value type is a String, but there are several other Value Types.

We’ll cover Strings and other valid Value Types further in “JSON Value Types”.

Objects consist of name/value pairs. Example 1-4 shows a sample Object that represents an address.

{"address":{"line1":"555 Any Street","city":"Denver","stateOrProvince":"CO","zipOrPostalCode":"80202","country":"USA"}}

Example 1-5 shows an Object with a nested Array.

{"speaker":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","topics":["JSON","REST","SOA"]}}

Example 1-6 shows an Object that contains another Object.

{"speaker":{"firstName":"Larson","lastName":"Richard","topics":["JSON","REST","SOA"],"address":{"line1":"555 Any Street","city":"Denver","stateOrProvince":"CO","zipOrPostalCode":"80202","country":"USA"}}}

Objects have the following characteristics:

Are enclosed within a beginning left curly brace ({) and an ending right curly brace (})

Consist of comma-separated, unordered, name/value pairs

Can be empty, { }

Can be nested within other Objects or Arrays

Example 1-7 shows an Array (containing nested Objects and Arrays) that describes conference presentations, including title, length, and abstract.

{"presentations":[{"title":"JSON at Work: Overview and Ecosystem","length":"90 minutes","abstract":["JSON is more than just a simple replacement for XML when","you make an AJAX call."],"track":"Web APIs"},{"title":"RESTful Security at Work","length":"90 minutes","abstract":["You’ve been working with RESTful Web Services for a few years","now, and you’d like to know if your services are secure."],"track":"Web APIs"}]}

Arrays have the following characteristics:

Are enclosed within a beginning left brace ([) and an ending right brace (])

Consist of comma-separated, ordered values (see the next section)

Can be empty, [ ]

Can be nested within other Arrays or Objects

Have indexing that begins at 0 or 1

JSON Value Types represent the Data Types that occur on the righthand side of the colon (:) of

a Name/Value Pair. JSON Value Types include the following:

object

array

string

number

boolean

null

We’ve already covered Objects and Arrays; now let’s focus on the remaining Value Types:

string, number, boolean, and null.

Example 1-8 shows valid JSON Strings.

["fred","fred\t","\b","","\t","\u004A"]

Strings have the following properties:

Strings consist of zero or more Unicode characters enclosed in quotation marks (""). Please see the

following list for additional valid characters.

Strings wrapped in single quotes (') are not valid.

Additionally, JSON Strings can contain the following backslash-escaped characters:

\" Double quote

\\ Backslash

\/ Forward slash

\b Backspace

\f Form feed

\n Newline

\r Carriage return

\t Tab

\u Trailed by four hex digits

Example 1-9 shows valid numbers in JSON.

{"age":29,"cost":299.99,"temperature":-10.5,"unitCost":0.2,"speedOfLight":1.23e11,"speedOfLight2":1.23e+11,"avogadro":6.023E23,"avogadro2":6.023E+23,"oneHundredth":10e-3,"oneTenth":10E-2}

Numbers follow JavaScript’s double-precision floating-point format and have the following properties:

Numbers are always in base 10 (only digits 0–9 are allowed) with no leading zeros.

Numbers can have a fractional part that starts with a decimal pont (.).

Numbers can have an exponent of 10, which is represented with the e or E notation with a plus or

minus sign to indicate positive or negative exponentiation.

Octal and hexadecimal formats are not supported.

Unlike JavaScript, numbers can’t have a value of NaN (not a number for invalid numbers) or Infinity.

Example 1-10 shows a Boolean value in JSON.

{"isRegistered":true,"emailValidated":false}

Booleans have the following properties:

Booleans can have a value of only true or false.

The true or false value on the righthand side of the colon(:) is not surrounded by quotes.

Although technically not a Value Type, null is a special value in JSON. Example 1-11 shows a

null value for the line2 key/property.

{"address":{"line1":"555 Any Street","line2":null,"city":"Denver","stateOrProvince":"CO","zipOrPostalCode":"80202","country":"USA"}}

null values have the following characteristics:

Are not not surrounded by quotes

Indicate that a key/property has no value

Act as a placeholder

According to Douglas Crockford, there will never be another version of the core JSON standard. This isn’t because JSON is perfect; nothing is perfect. The purpose of a sole JSON version is to avoid the pitfalls of having to support backward compatibility with previous versions. Crockford believes that a new data format should replace JSON when the need arises within the development community.

But as you’ll see in subsequent chapters, this “no versions” philosophy applies only to the core JSON data format. For example, in Chapter 5, that specification is currently at version 0.5 as of this writing. Please note that these JSON-related specifications were created by others in the JSON community.

There are no comments in a JSON document. Period.

According to his postings on the Yahoo! JSON group and Google+, Crockford initially allowed comments, but removed them early on for the following reasons:

He believed that comments weren’t useful.

JSON parsers had difficulties supporting comments.

People were abusing comments. For example, he noticed that comments were being used for parsing directives, which would have destroyed interoperability.

Removing comments simplified and enabled cross-platform JSON support.

According to the core JSON specification, .json is the standard JSON file type when storing JSON

data on filesystems. JSON’s Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) media (or MIME) type is

application/json, which can be found at the IANA Media Types site. RESTful Web Service Producers and Consumers use a technique known as content negotiation (which leverages the JSON MIME type in HTTP Headers) to indicate that they are exchanging JSON data.

JSON is all about interoperability, and it’s important to provide JSON data feeds in a way that Consumers expect. Google has published a JSON Style Guide to support maintainability and best practices.

The Google JSON Style Guide is extensive, and here are the most important things for an API designer and developer:

Property Names

Date Property Values

Enum Values

Property Names (in Google parlance) are on the left side of the colon in a name/value pair (and Property Values are on the righthand side of the hyphen). Two main styles can be used to format a JSON Property Name:

lowerCamelCase

snake_case

With lowerCamelCase, a name is created by joining one or more words to look like a single word, and the

first letter in each word is capitalized (except for the first word). Both the Java and JavaScript

communities use lowerCamelCase in their coding guides. With snake_case, all letters are lowercase,

and words are separated with an underscore (_). But the Ruby on Rails community prefers snake_case.

Google, along with the majority of RESTful APIs, uses lowerCamelCase for its Property Names, as shown in Example 1-12.

{"firstName":"John Smith"}

You may think that Date formats aren’t that important, but they are. Imagine exchanging date information between a Producer and Consumer who come from different countries or continents. Even within a single enterprise, two development groups will likely use different date formatting conventions. It is important to consider the semantics of how to interpret timestamps so that we have consistent date/time processing and interoperability across all time zones. The Google JSON Style Guide prefers that dates follow the RFC 3339 format, as shown in Example 1-13.

{"dateRegistered":"2014-03-01T23:46:11-05:00"}

The preceding date provides a Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) offset (from UTC/GMT—Greenwich Mean Time) of

-5 hours, which is US Eastern Standard Time. Note that RFC 3339 is a profile of ISO 8601. The main

difference is notably that the International Standards Organization’s ISO 8601 allows

the replacement of the T (which separates the date and time) with a space, and RFC 3339 does not allow

this.

Geographical APIs (e.g., Google Maps) and APIs related to a geographical information system (GIS) use latitude/longitude data. To support consistency, the Google JSON Style Guide recommends that latitude/longitude data follows the ISO 6709 standard. According to Google Maps, the coordinates for the Empire State Building in New York City are 40.748747° N, 73.985547° W, and would be represented in JSON as shown in Example 1-14.

{"empireStateBuilding":"40.748747-73.985547"}

This example follows the ±DD.DDDD±DDD.DDDD format, with the following conventions:

Latitude comes first.

North (of the equator) latitude is positive.

East (of the prime meridian) longitude is positive.

The latitude/longitude is represented as a String. It can’t be a Number because of the minus sign.

Although the Google JSON Style Guide is silent on this topic, here are a few rules of thumb:

JSON is a serialization format, not a presentation format. So, indentation is meaningless to an API Producer or Consumer.

Many JSON Formatters let the user choose between two, three, or four spaces when beautifying a JSON document.

JSON originated from JavaScript (as part of the ECMA 262 standard), but unfortunately there is no single consensus throughout the JavaScript community. Many people and coding style guides prefer two spaces, so this is the convention used in this book for consistency. It’s OK if you prefer another style here, but be consistent.

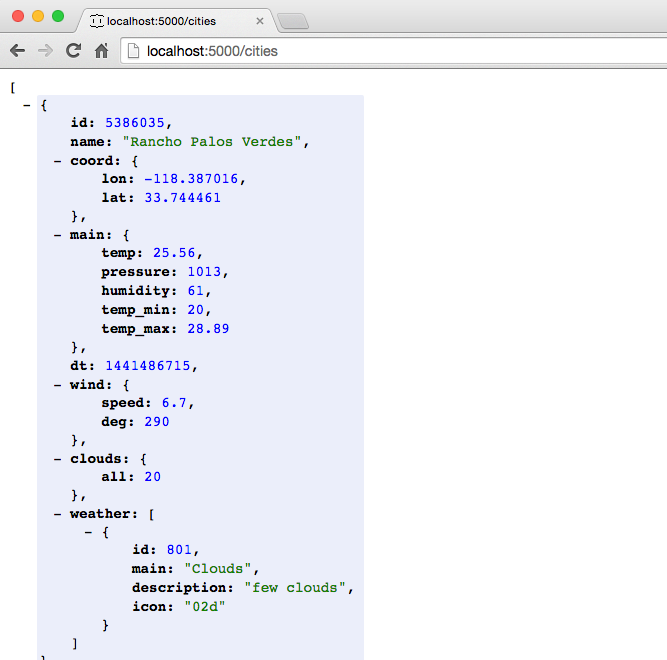

Our examples throughout this book cover conference-related data, including the following:

Speakers

Sessions

We’ll start by creating a simple JSON data store for speakers and publishing it to a Stub RESTful API by taking the following steps:

Model JSON data with JSON Editor Online

Generate sample JSON data with JSON Generator

Create and deploy a Stub API (for future testing)

Our architectural style is based on the concept of noBackend. With noBackend, the developer doesn’t have to worry about the nuts and bolts of application servers or databases at the early stages of application development.

The first seven chapters of this book use noBackEnd architecture to maintain focus on our application

from a business perspective (services and data first) so that we can support not only UI-based

(e.g., mobile, tablet, and web) clients, but APIs and non-web-based client applications as well. We’ll deploy

JSON data with simple tools such as json-server to emulate a RESTful API.

By using this approach, we take an interface-first approach to designing and building an API, which provides the following:

More Agile, rapid, iterative frontend development due to the decoupling from the backend.

Faster feedback on the API itself. Get the data and URI out there quickly for rapid review.

A cleaner interface between the API and its Consumers.

A separation of concerns between the Resource (e.g., speakers as JSON data) exposed by the API and its (eventual) internal implementation (e.g., application server, business logic, and data store). This makes it easier to change implementation in the future. If you create and deploy a real API with Node.js/Rails/Java (or other framework) too early, you’ve already made design decisions at a very early stage that will make it difficult to change after you start working with API Consumers.

A Stub API does the following:

Eliminates the initial need to work with servers and databases

Allows API Producers (those developers who write the API) to focus on API Design, how best to present the data to the Consumers, and initial testing

Enables API Consumers (e.g., UI developers) to work with the API at an early stage and provide feedback to the API development team

By using the lightweight tools in this book, you’ll see that you can go a long way before writing code and deploying it on a server. Of course, you’ll eventually need to implement an API, and we’ll show how to do that when we cover JavaScript, Ruby on Rails, and Java in Chapters 2–4.

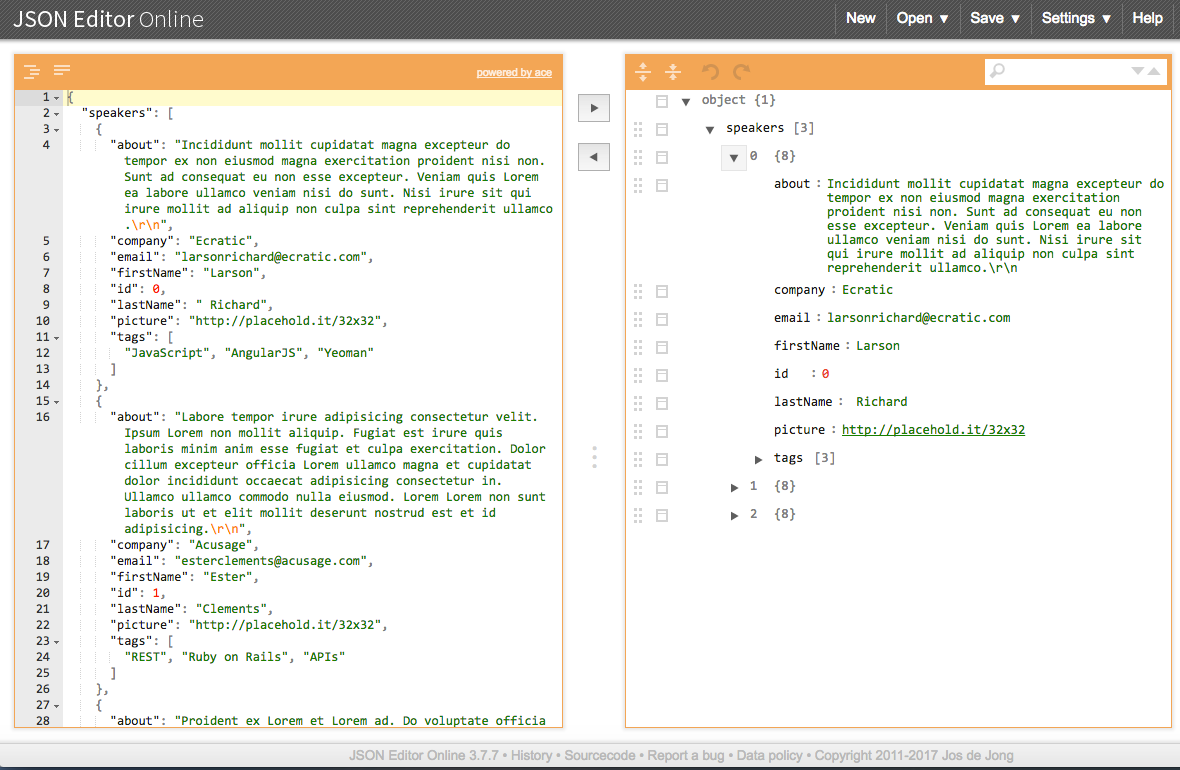

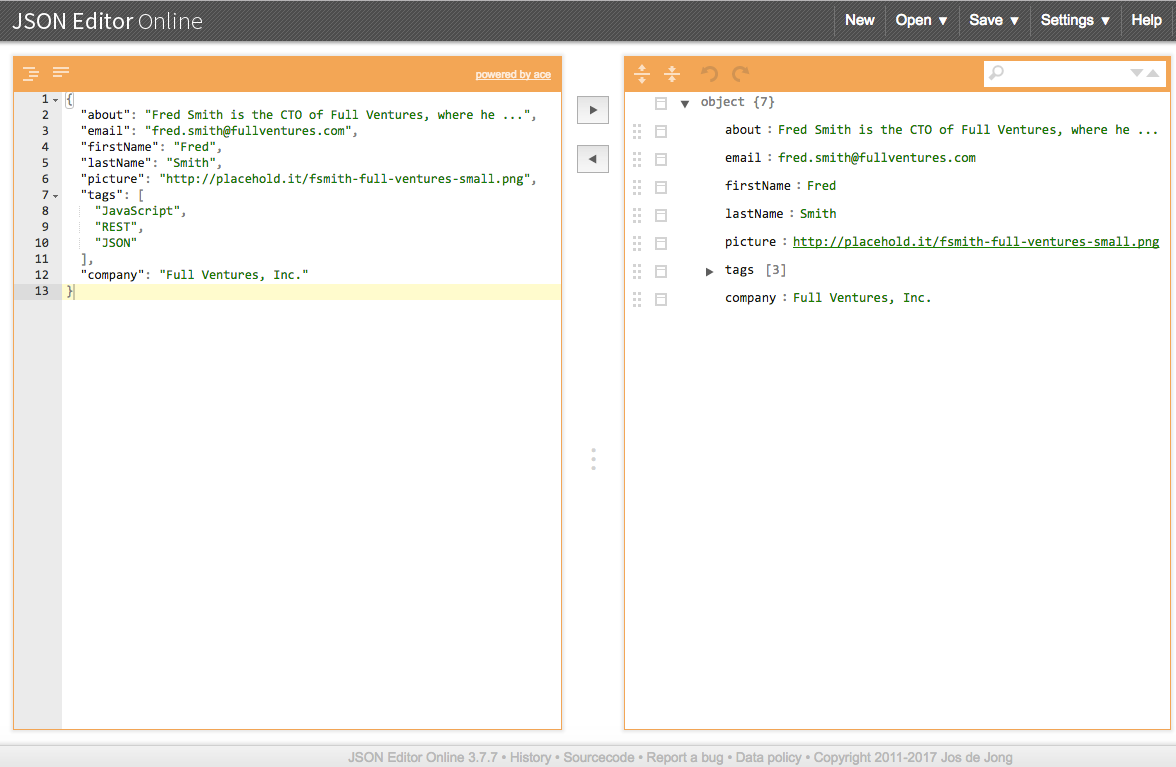

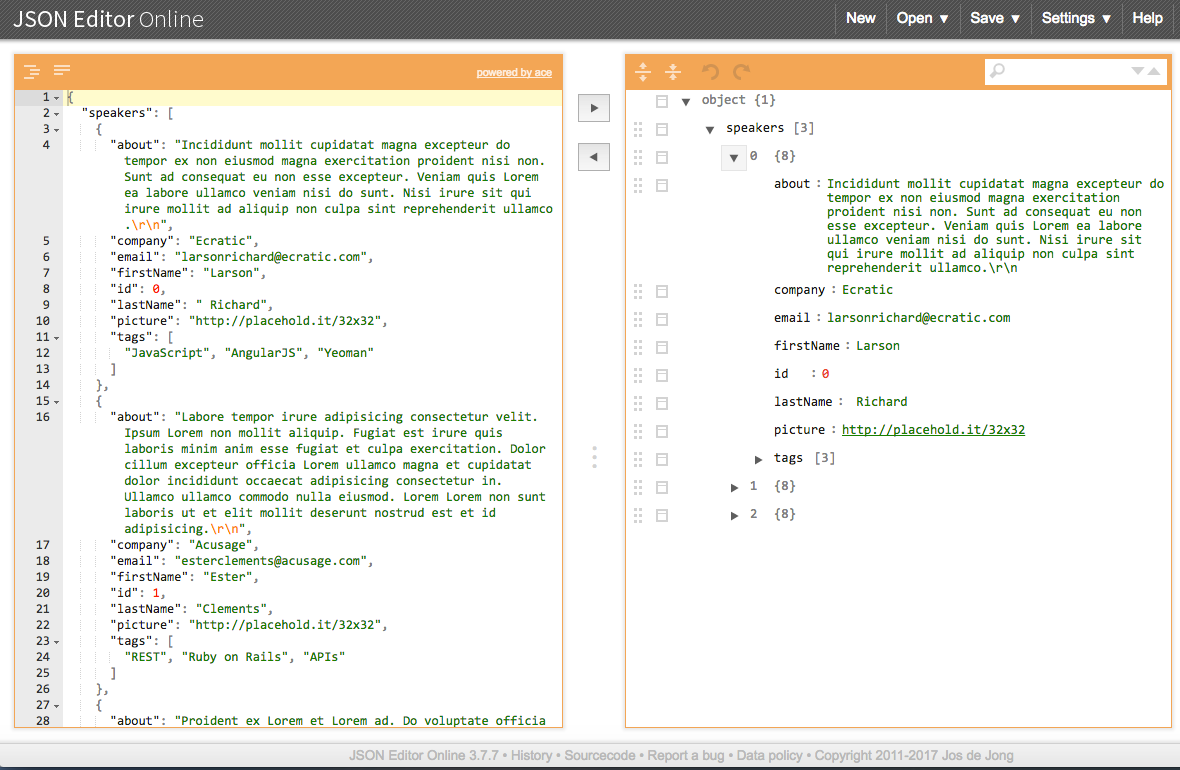

Creating a valid JSON document of any real size or complexity is tedious and error-prone. JSON Editor Online is a great web-based tool that does the following:

Enables you to model your JSON document as Objects, Arrays, and name/value pairs

Makes it easier to rapidly generate the text for a JSON document in an iterative manner

JSONmate is another solid editor on the web, but we don’t cover it further in this book.

In addition to JSON modeling and text generation, JSON Editor Online provides the following features:

Validation occurs as you type JSON data in the JSON text area on the left side of the page. If you forget a closing double quote for a value (e.g., "firstName": "Ester,), an X will show next to the following line of JSON text along with hover text that explains the validation error.

Click the Indent button at the upper-left corner of the JSON text area.

After creating some Objects and key/value pairs (with the Append (+) button) in the JSON model on the right side of the page, generate JSON text by clicking the left-arrow button (in the upper-middle portion of the page). You should see the changes reflected in the JSON text area on the left side of the page.

Modify some data in the JSON text area and click the right-arrow button, and you should see the changes in the JSON model on the righthand side of the page.

You can save a JSON document to your local machine by selecting the Save to Disk option under the Save menu.

You can import a JSON document from your computer by choosing the Open from Disk option from the Open menu.

Please remember that JSON Editor Online is publicly available, which means that any data you paste into this app is visible to others. So don’t use this tool with sensitive information (personal, proprietary, and so forth).

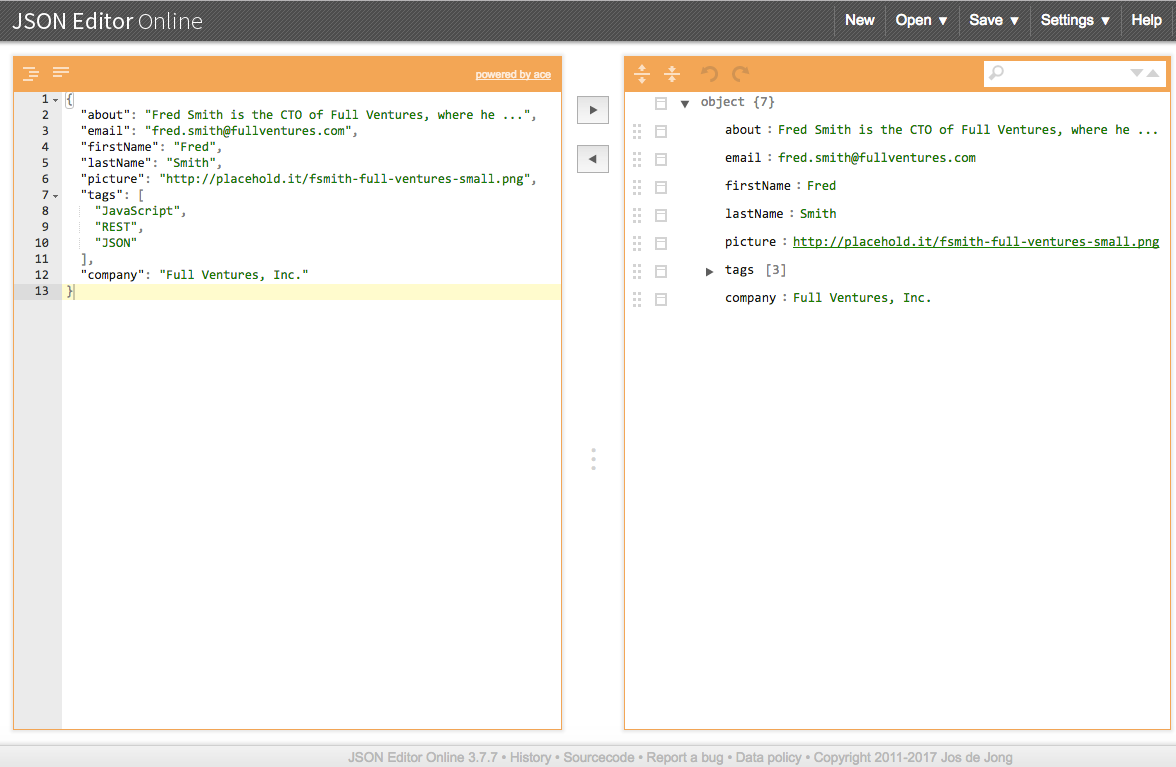

After you’re finished modeling Speaker data, click the right-arrow button to generate a pretty-printed (indented) JSON document that represents the model. Figure 1-3 shows JSON Editor Online with our initial Speakers model.

This is just a rough model, but this initial sketch is a decent starting point. Use the initial model to visualize JSON data, get early feedback, and iterate quickly on the design. This approach enables you to refine the JSON data structure throughout the development life cycle without investing heavily in implementation and infrastructure.

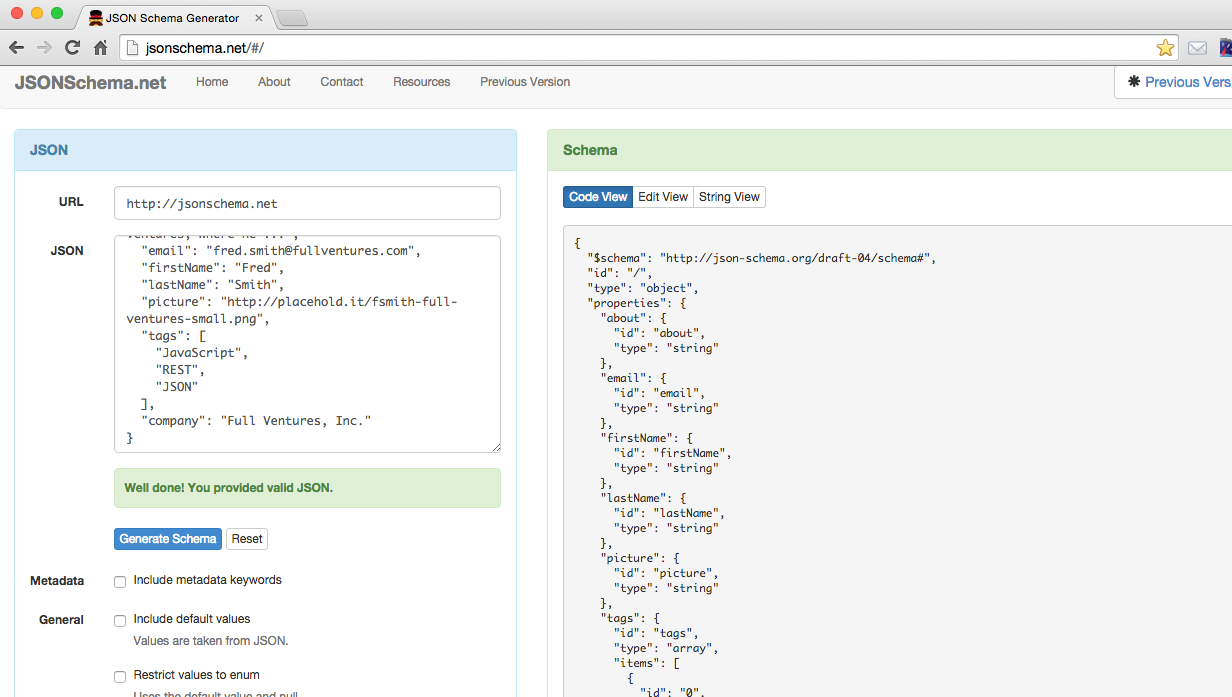

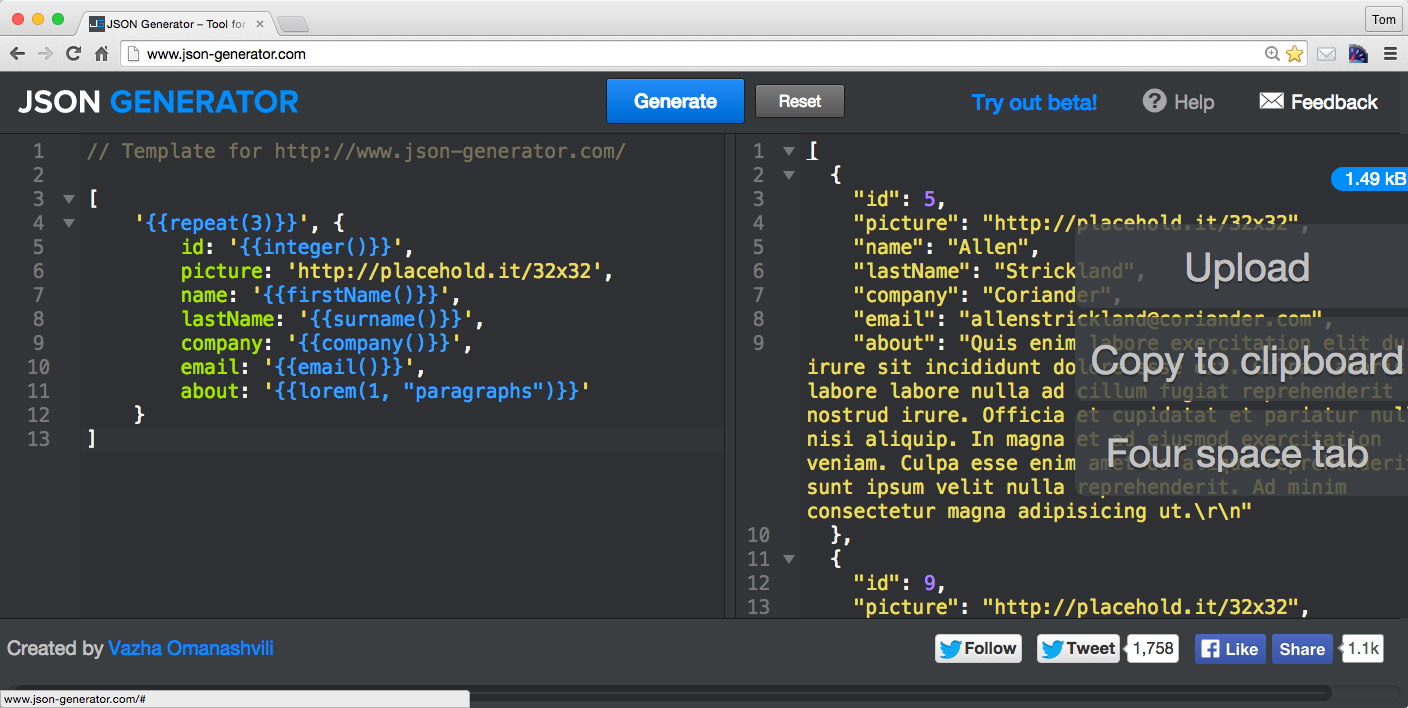

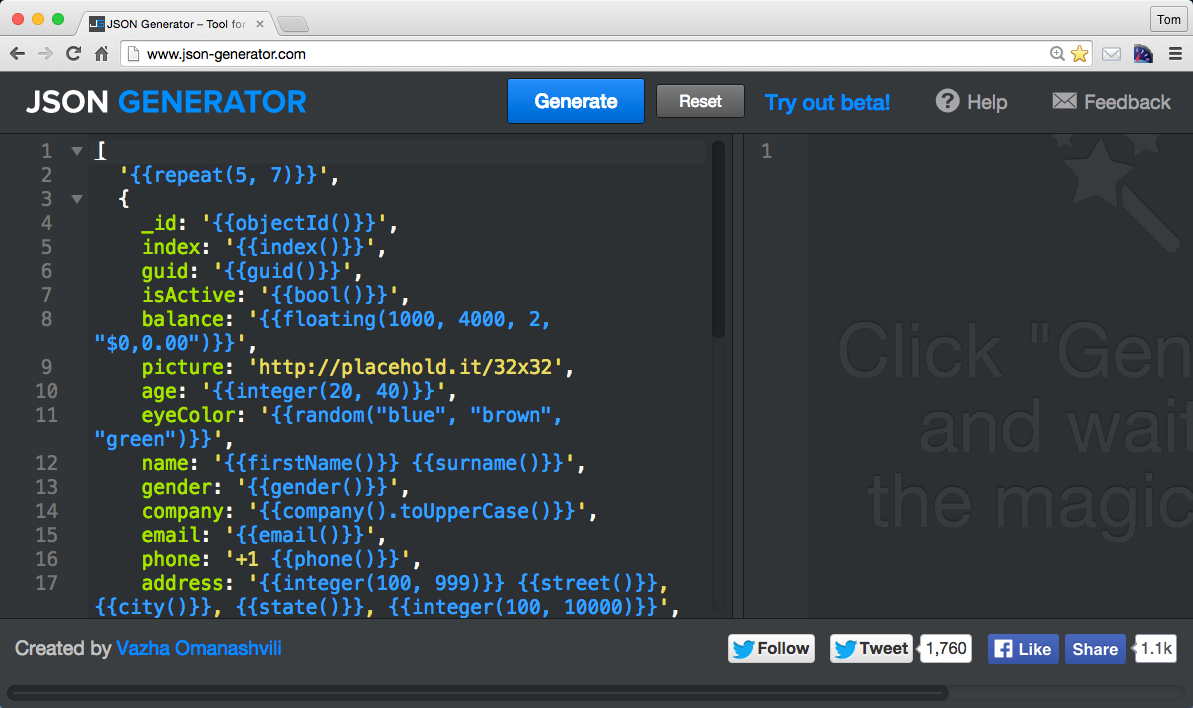

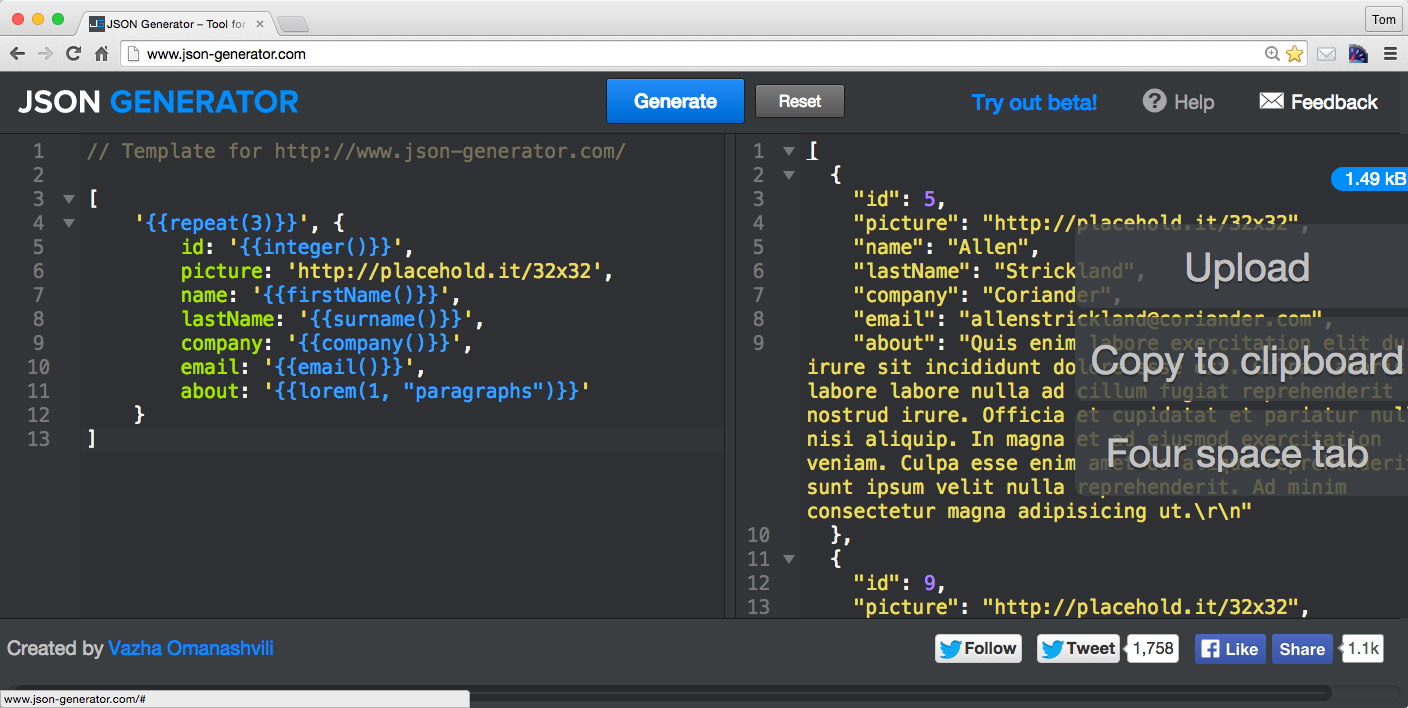

JSON Editor Online provides a decent start, but we want to generate lots of test data quickly. Test data can be problematic because of the sensitivity of the data, and the data volume needed to do any meaningful testing. Even with JSON Editor Online, it will take a great deal of effort to create the volume of test data we’re looking for. We need another tool to help create the data we need to create our first version of the API, and that’s where JSON Generator comes in. This excellent tool was used to create our speakers.json test data file. The template used to generate the speakers.json file is available on GitHub. Chapter 5 covers JSON Generator in more detail.

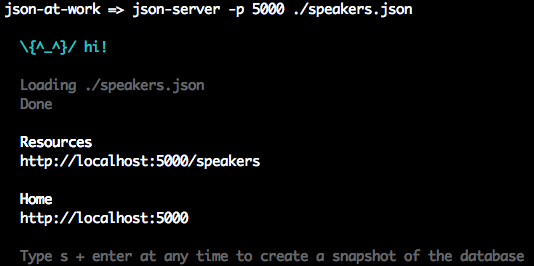

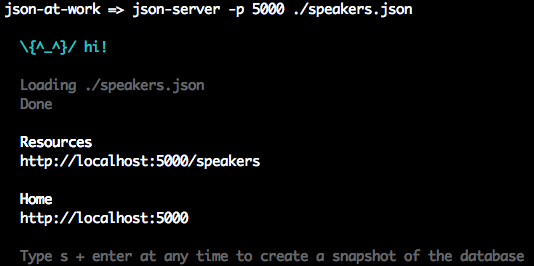

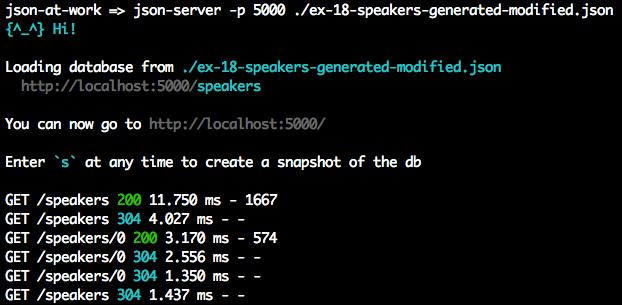

To create the Stub API, we’ll use the Speaker data we just created and deploy it as a RESTful API. We’ll

leverage the json-server Node.js module to serve up the speakers.json file as a Web API; this enables us

to prototype quickly. You can find more information on the json-server GitHub page.

Before going further, please set up your development environment. Refer to Appendix A to do the following:

Install Node.js. json-server is a Node.js module, so you need to install Node.js first. Refer to “Install Node.js”.

Install json-server. See “Install npm Modules”.

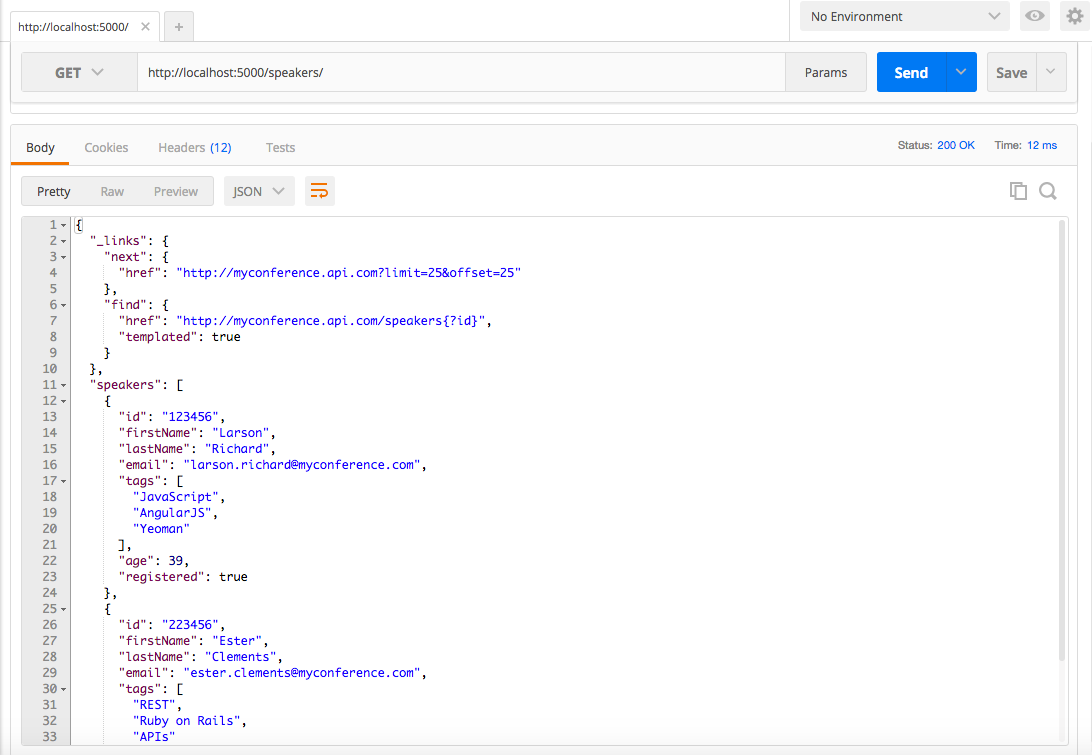

Install JSONView and Postman. See “Install JSON Tools in the Browser”. JSONView pretty-prints JSON in Chrome and Firefox. Postman can also run as a standalone GUI application on most major operating systems.

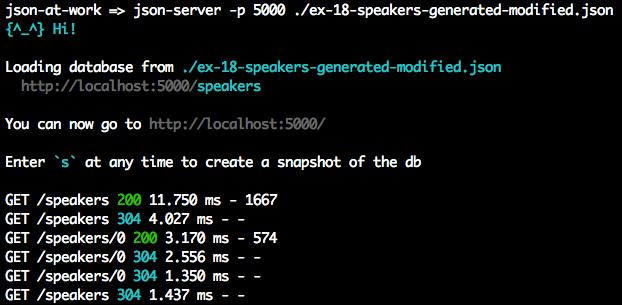

Open a terminal session and run json-server on port 5000 from your command line:

cd chapter-1 json-server -p 5000 ./speakers.json

You should see the following:

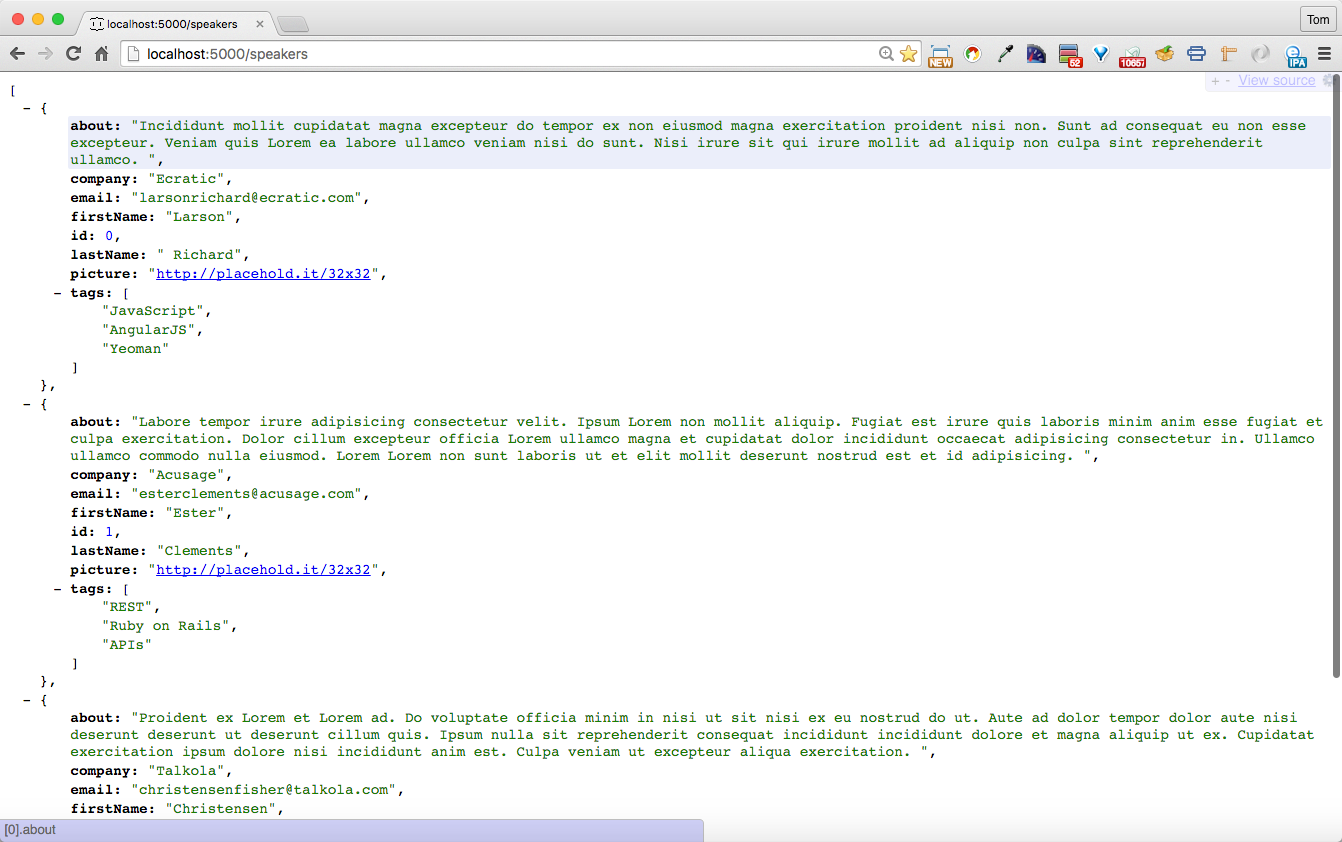

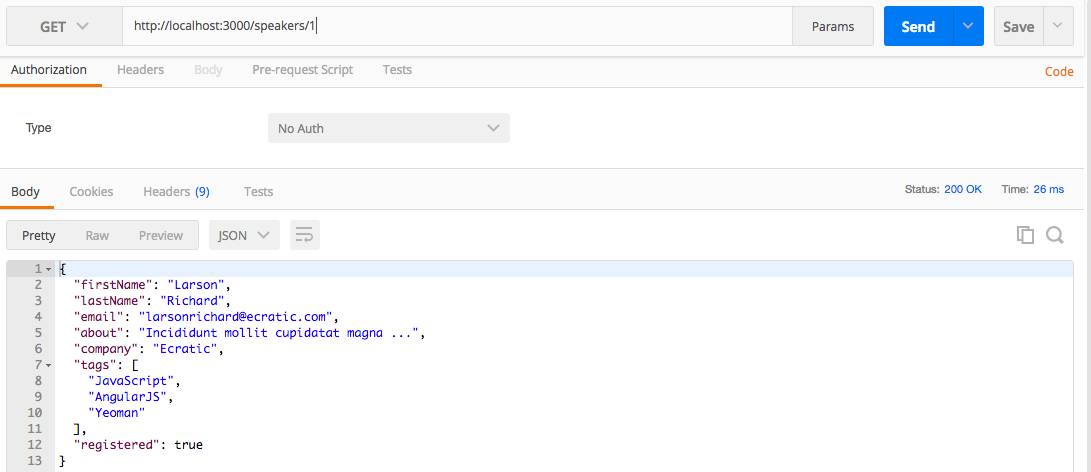

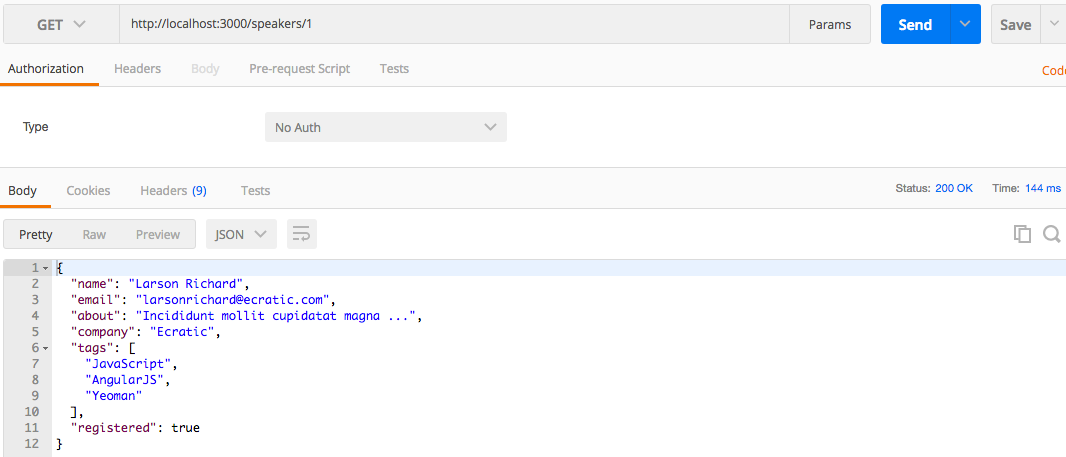

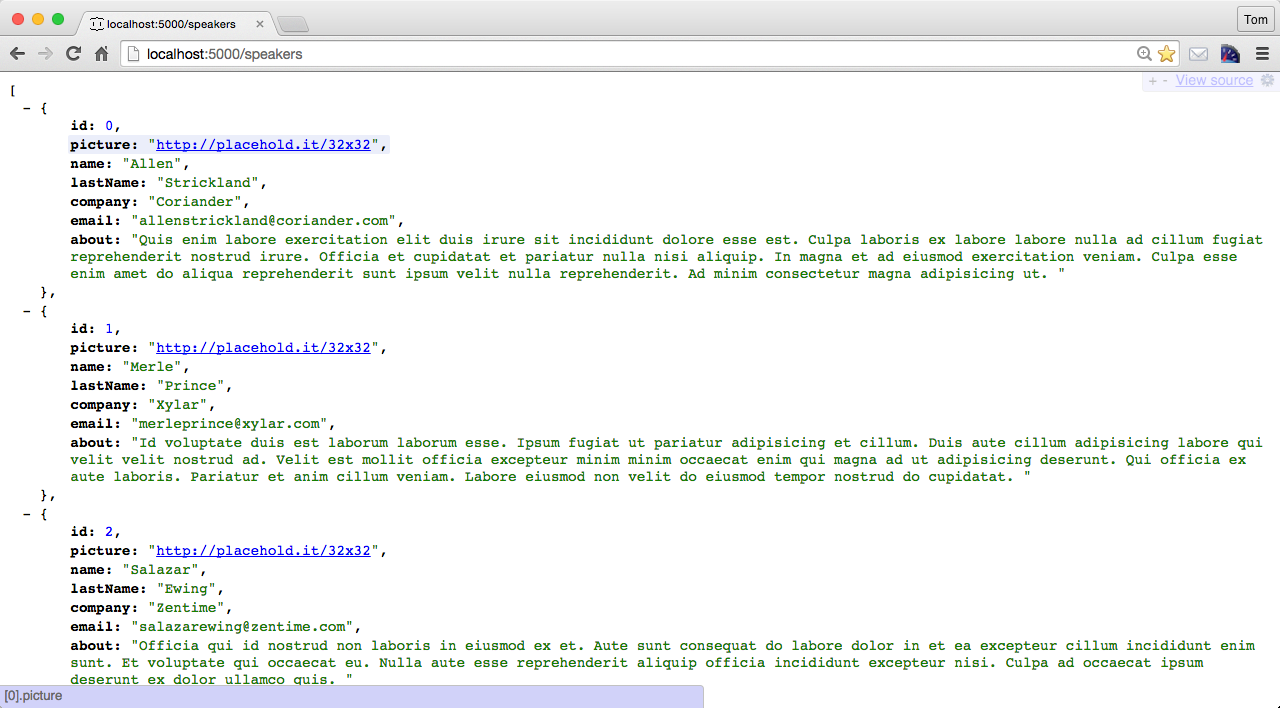

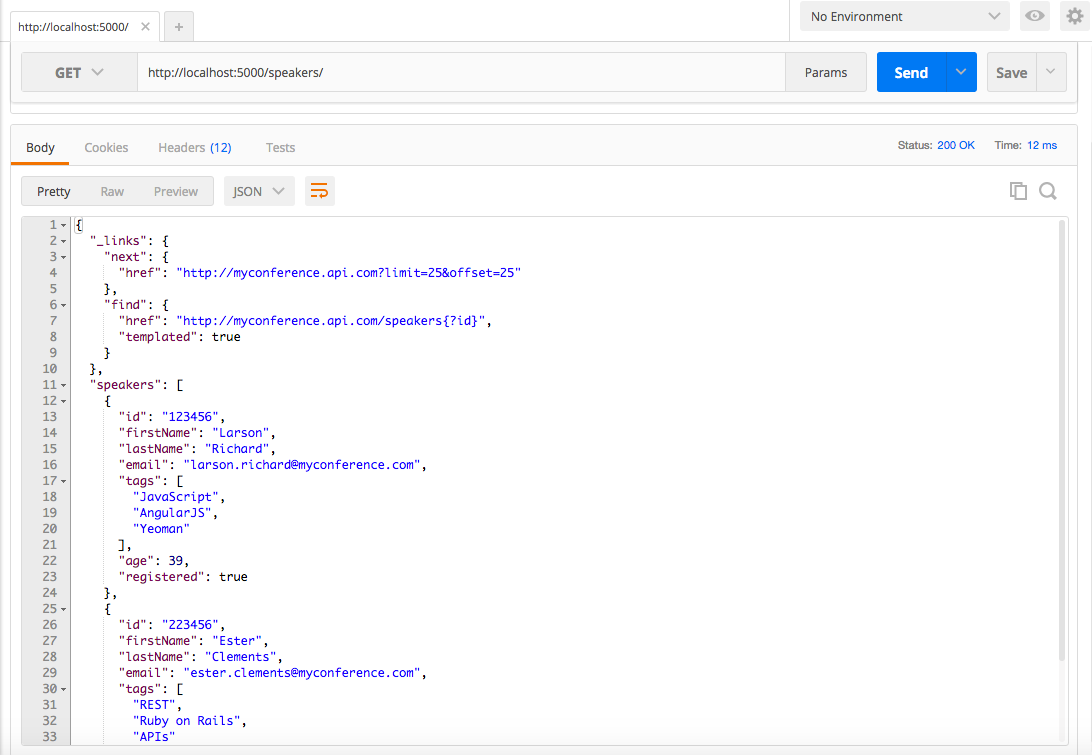

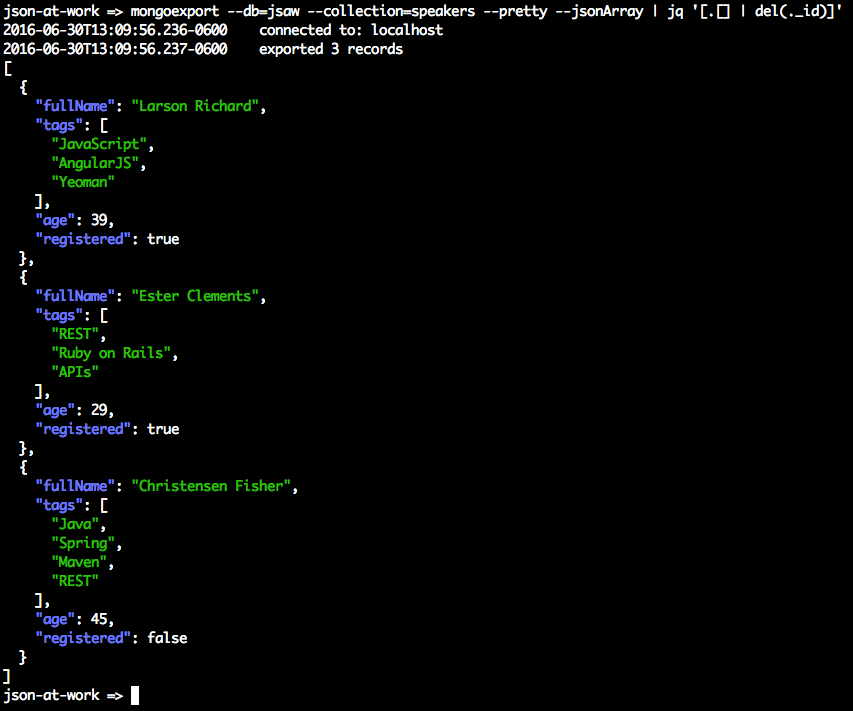

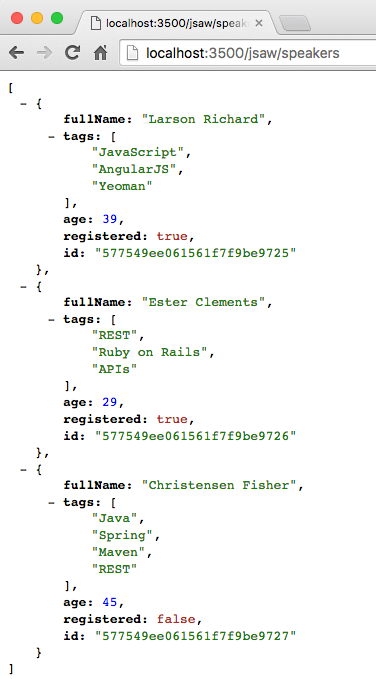

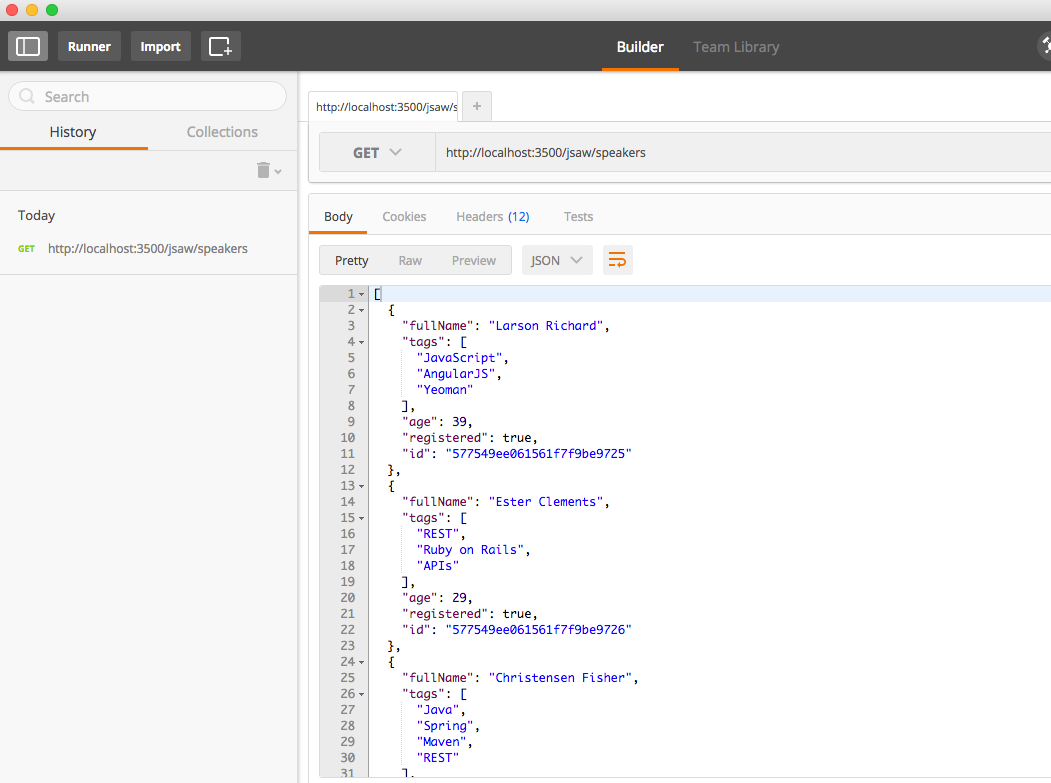

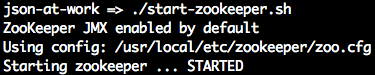

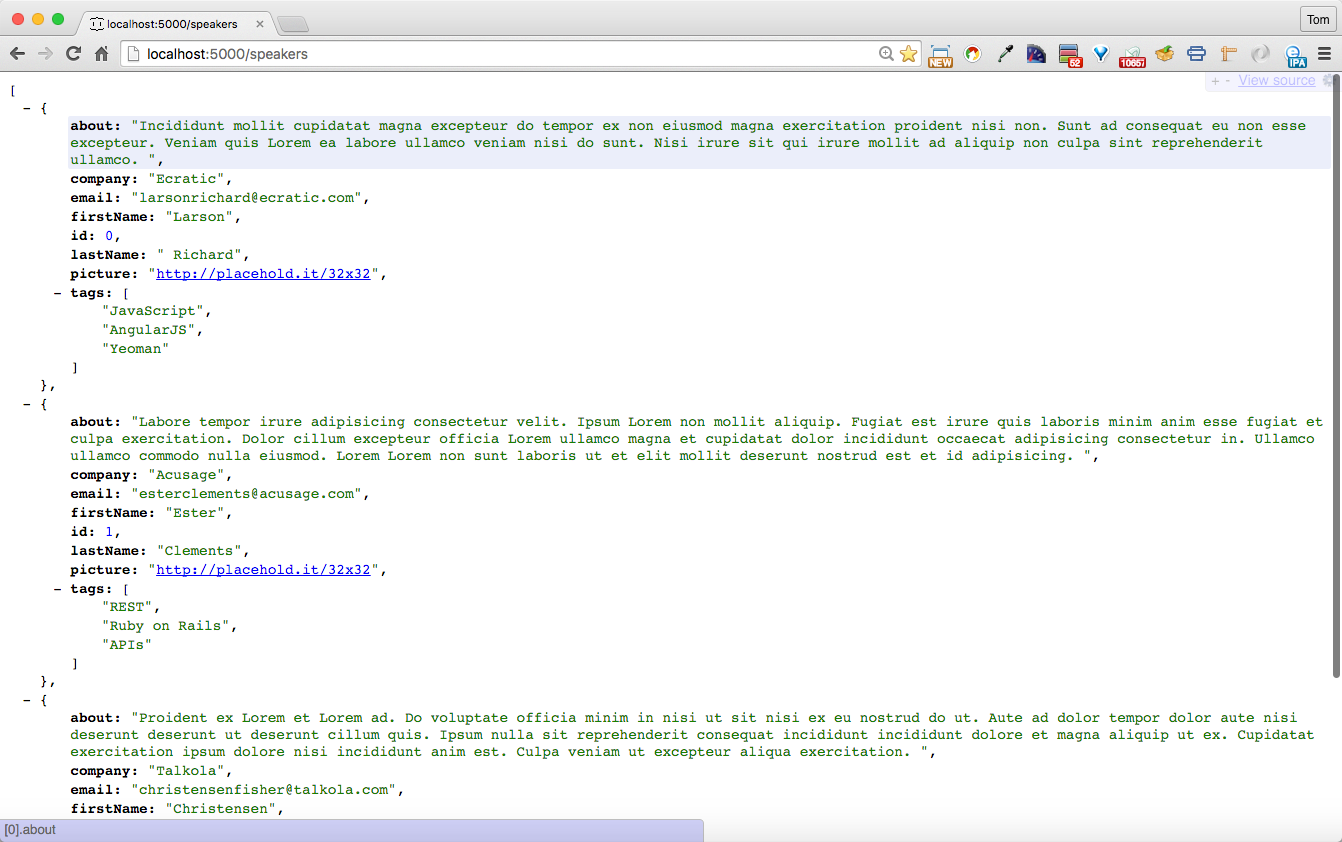

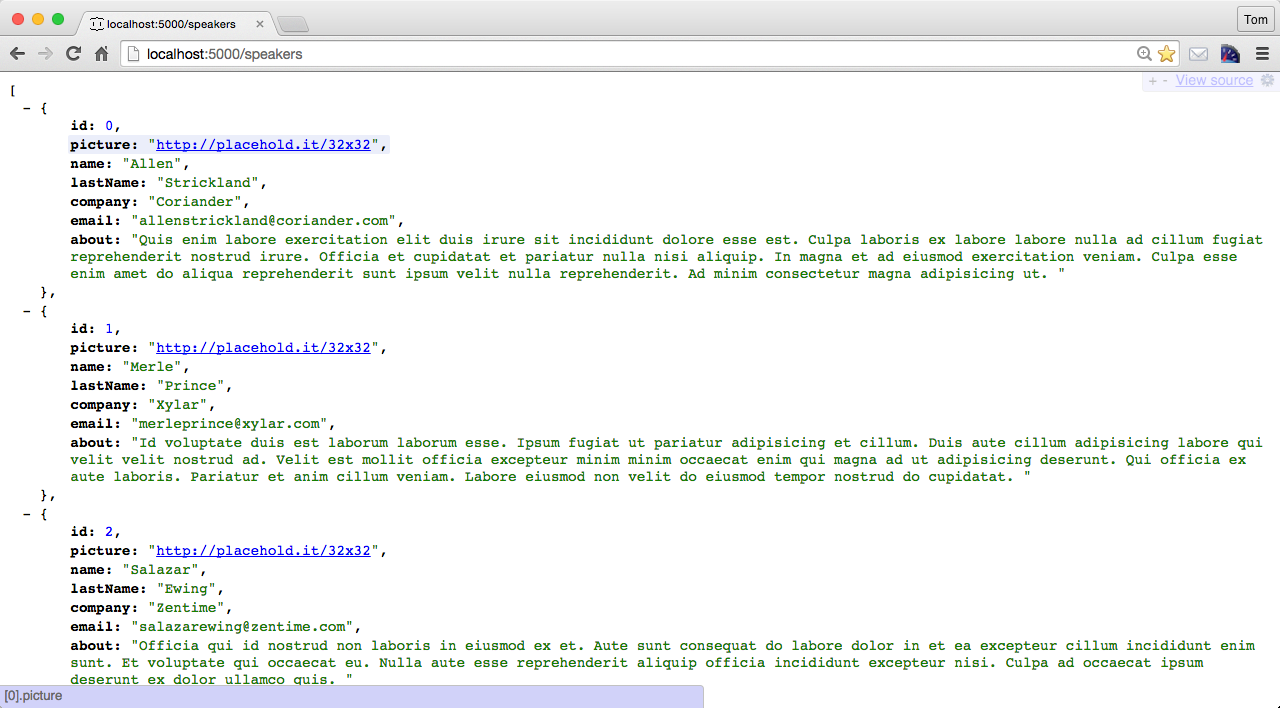

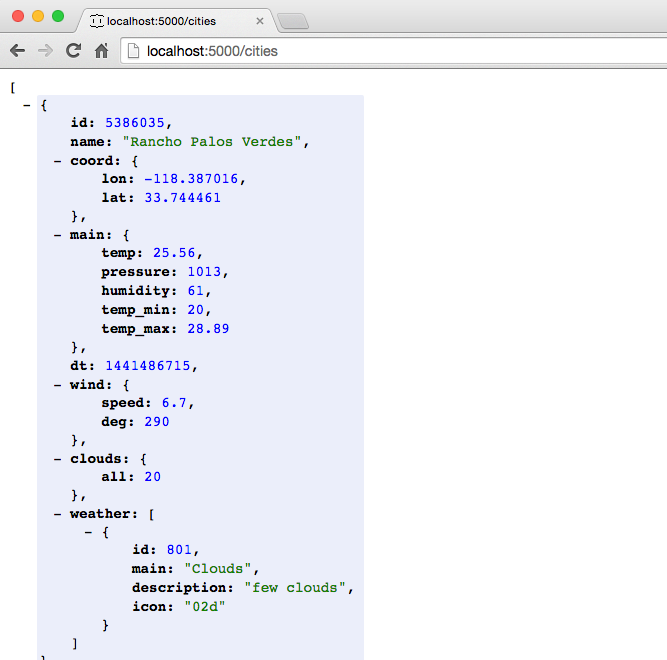

Visit http://localhost:5000/speakers in your browser, and (with JSON pretty-printing provided by JSONView) you should see all the speakers from our Stub API as shown in Figure 1-4.

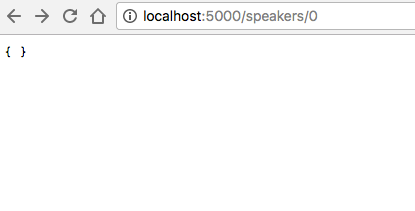

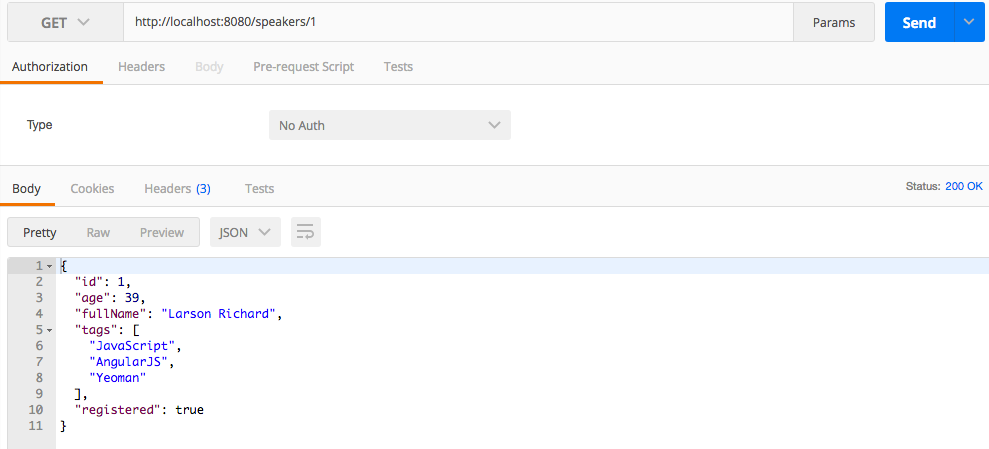

You can also get a single speaker by adding the id to the URI as follows:

http://localhost:5000/speakers/0.

This is a good start, but a web browser has limited testing functionality; it can only send HTTP GET

requests. Postman provides the ability to fully test a RESTful API. It can send HTTP GET, POST, PUT,

and DELETE requests and set HTTP Headers.

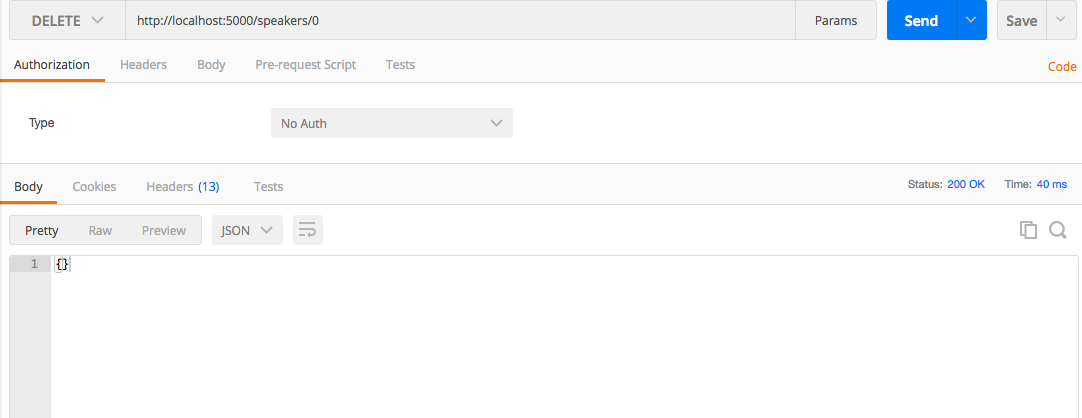

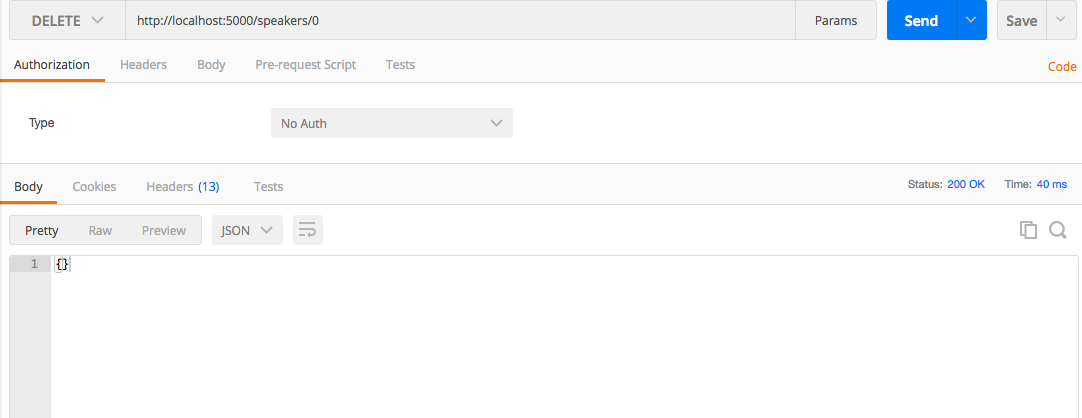

Let’s use Postman to delete the first speaker in the API as follows:

Enter the http://localhost:5000/speakers/0 URL.

Choose DELETE as the HTTP verb.

Click the Send button.

You should see that the DELETE ran properly in Postman with a 200 (OK) HTTP Status, as shown in Figure 1-5.

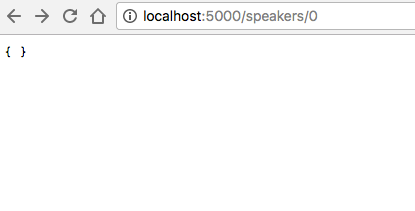

Now, ensure that the first speaker has truly been deleted by revisiting http://localhost:5000/speakers/0 in your browser. You should now see the empty response shown in Figure 1-6.

You can stop json-server by pressing Ctrl-C at the command line.

With the Stub API in place, we can now invoke it from any HTTP client (e.g., JavaScript, Ruby, or Java) to consume the data from an external application. Although most of our examples in subsequent chapters use an HTTP GET, rest assured that json-server can handle all the core HTTP verbs (GET,

POST, PUT, DELETE). Although not covered in this book, Mountebank

is an alternative server that provides more robust functionality for stubbing and mocking APIs and protocols.

The main point here is that an API Producer can use JSON-based tools to prototype a testable RESTful API without having to write any code. This technique is powerful because it enables the API Consumer to test without having to wait for the API to be 100 percent complete. At the same time, the API development team can iteratively upgrade the design and prototype.

We started by covering the basics of JSON. We modeled JSON data with JSON Editor Online, and deployed it with a Stub API.

The next three chapters show how to use JSON with the following core platforms:

JavaScript

Ruby on Rails

Java

In Chapter 2, you’ll learn how to use JSON in JavaScript with the Stub API we just created with json-server.

We’ve covered the basics of the JSON data interchange format, and in this chapter we’ll begin to develop applications with JSON. JSON began as a subset of the JavaScript definition for Objects and Arrays, but rest assured that JSON is now decoupled from JavaScript. JSON is language-agnostic and works across multiple platforms. Because JSON has its roots in JavaScript, this is where we begin our journey.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Using JavaScript serialization/deserialization with JSON.stringify() and JSON.parse()

Working with JavaScript Objects and JSON

Making RESTful API calls and testing the results with Mocha/Chai Unit Tests

Building a small JSON-based web application

In our examples, we’ll leverage Node.js, scaffold a web application with Yeoman, and make RESTful API calls

to pull in the data we created on json-server in the previous chapter. That’s a lot of moving pieces and

parts, so we’ll iteratively build on each concept. But before we develop our web app, we need to start

with the basics of JavaScript serialization/deserialization and Objects.

Before we go any further, let’s start building our development environment by installing Node.js. Please go to Appendix A, and follow the instructions in “Install Node.js”.

Applications need to serialize (or flatten) their information into JSON in order to produce data for other applications in a platform-neutral manner. An application must also be able to deserialize (or unflatten) JSON data consumed from external sources into data structures for use by that application.

The JSON stringifier/parser Object was originally developed by Douglas Crockford, has been part of the

JavaScript library as of ECMAScript 5 in 2009,

and provides the following methods:

JSON.stringify() serializes to JSON

JSON.parse() deserializes from JSON

Additionally, the JSON Object

Was originally developed by Crockford

Can’t be instantiated

Has no other functionality

We’ll start by serializing some basic JavaScript Data Types:

Number

String

Array

Boolean

Object (Literal)

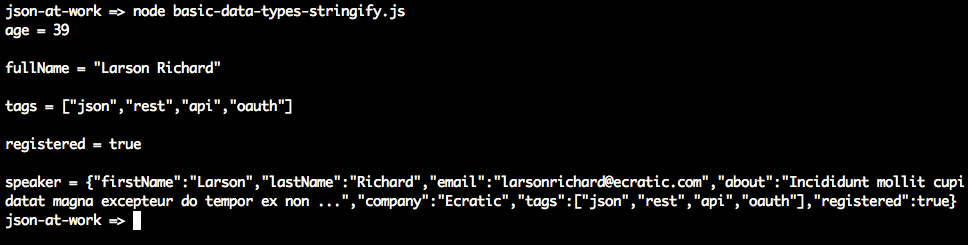

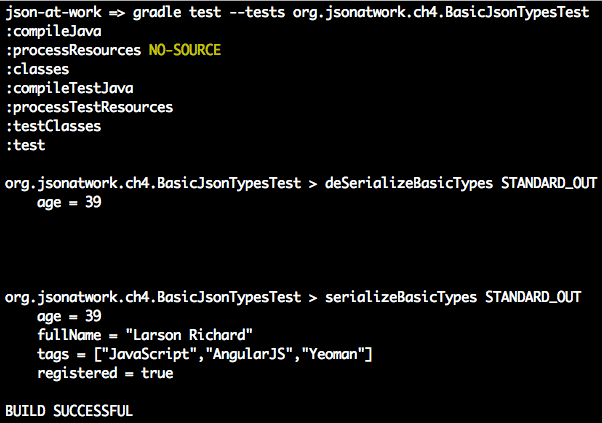

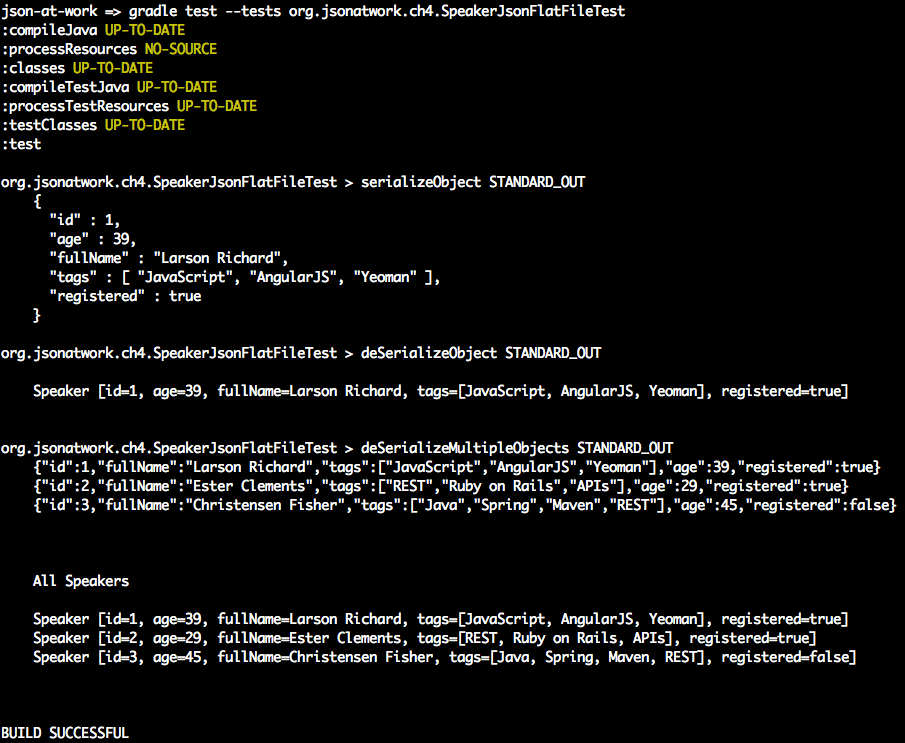

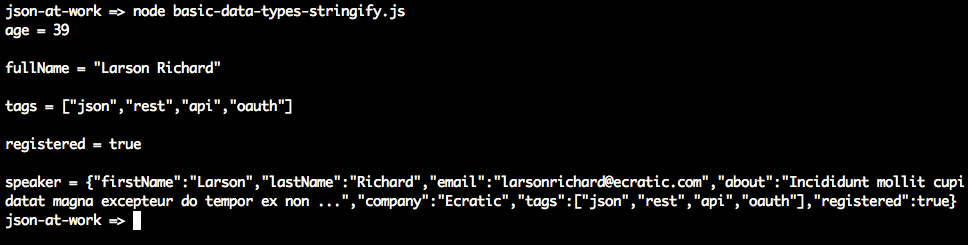

Example 2-1 shows how to use JSON.stringify() to serialize simple Data Types.

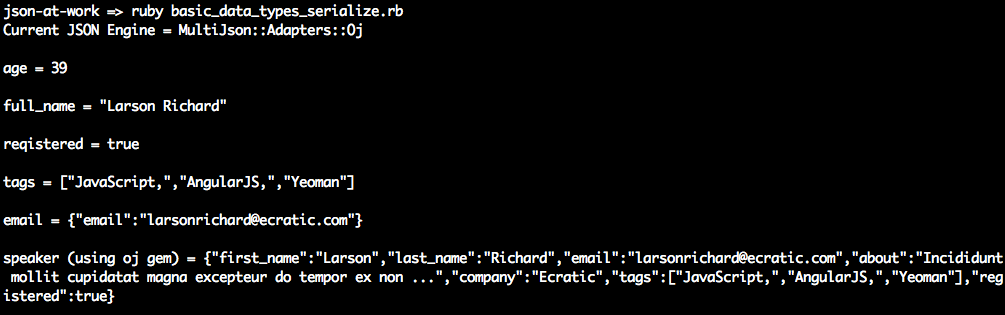

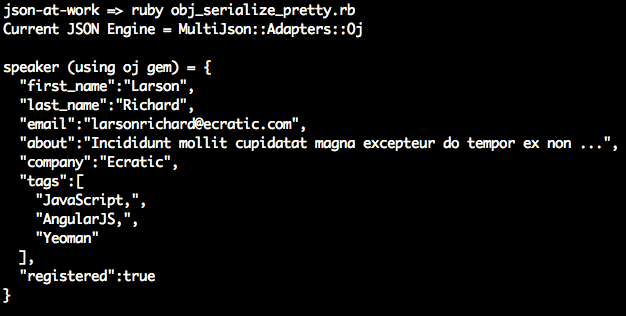

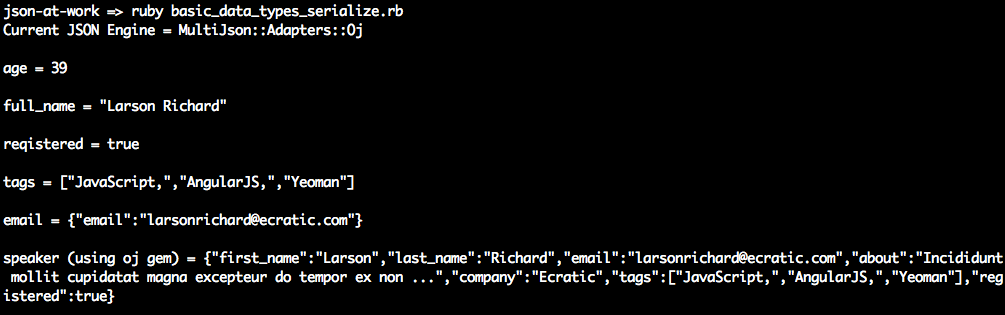

varage=39;// Integerconsole.log('age = '+JSON.stringify(age)+'\n');varfullName='Larson Richard';// Stringconsole.log('fullName = '+JSON.stringify(fullName)+'\n');vartags=['json','rest','api','oauth'];// Arrayconsole.log('tags = '+JSON.stringify(tags)+'\n');varreqistered=true;// Booleanconsole.log('registered = '+JSON.stringify(reqistered)+'\n');varspeaker={firstName:'Larson',lastName:'Richard',:'larsonrichard@ecratic.com',about:'Incididunt mollit cupidatat magna excepteur do tempor ex non ...',company:'Ecratic',tags:['json','rest','api','oauth'],registered:true};console.log('speaker = '+JSON.stringify(speaker));

When you run the preceding file with node from the command line, you should get the following:

JSON.stringify() doesn’t do anything too interesting with the scalar types (Number, String, Boolean).

Things begin to get interesting with the speaker Object Literal because here JSON.stringify() initially

generates a valid, yet unattractive, JSON String. JSON.stringify() has other parameters that enhance

serialization. According to the Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) JavaScript Guide,

here is the method signature:

JSON.stringify(value[,replacer[,space]])

The parameter list is as follows:

value (required) The JavaScript value to serialize.

replacer (optional) Either a function or an array. If a function is provided, the stringify() method

invokes the replacer function for each key/value pair in an Object.

space (optional) Indentation—either a Number or String. If a Number is used, this value specifies the number of spaces used for each indentation level.

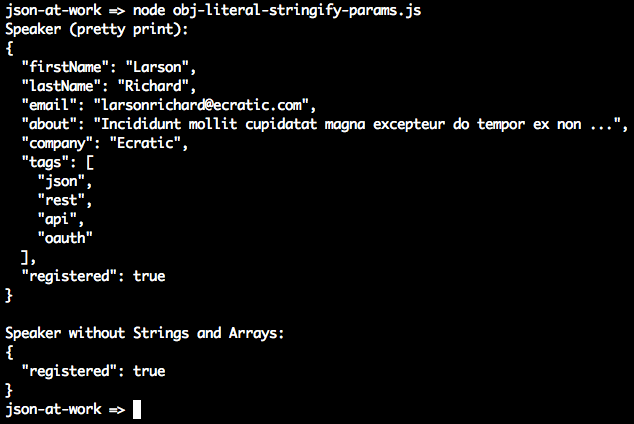

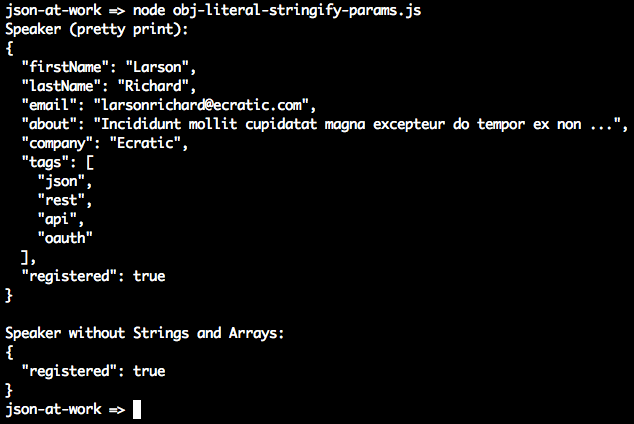

Let’s leverage the replacer and space parameters to pretty-print the speaker Object and filter out

some data elements, as shown in Example 2-2.

varspeaker={firstName:'Larson',lastName:'Richard',:'larsonrichard@ecratic.com',about:'Incididunt mollit cupidatat magna excepteur do tempor ex non ...',company:'Ecratic',tags:['json','rest','api','oauth'],registered:true};functionserializeSpeaker(key,value){return(typeofvalue==='string'||Array.isArray(value))?undefined:value;}// Pretty Print.console.log('Speaker (pretty print):\n'+JSON.stringify(speaker,null,2)+'\n');// Pretty print and filter out Strings and Arrays.console.log('Speaker without Strings and Arrays:\n'+JSON.stringify(speaker,serializeSpeaker,2));

Running the preceding file yields the following:

The first JSON.stringify() call pretty-prints the JSON output with an indentation level of 2. The second

call uses the serializeSpeaker() function as a replacer (JavaScript functions are treated as expressions

and can be passed as parameters). serializeSpeaker() checks the type of each value and returns undefined

for Strings and Arrays. Otherwise, this function returns the value “as is.”

JSON.stringify() does one of the following with an undefined value:

Omits the value if it’s part of an Object

Converts the value to null if that value belongs to an Array

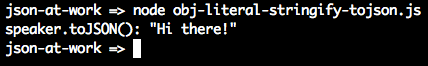

As you’ve seen, JSON serialization makes the most sense with Objects. Let’s customize

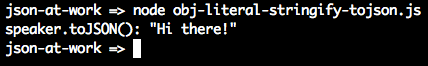

JSON.stringify()’s output by adding a toJSON() method to our speaker Object, as shown in Example 2-3.

varspeaker={firstName:'Larson',lastName:'Richard',:'larsonrichard@ecratic.com',about:'Incididunt mollit cupidatat magna excepteur do tempor ex non ...',company:'Ecratic',tags:['json','rest','api','oauth'],registered:true};speaker.toJSON=function(){return"Hi there!";}console.log('speaker.toJSON(): '+JSON.stringify(speaker,null,2));

Serialization works as follows:

If an Object has a toJSON() method, JSON.stringify() outputs the value returned by the Object’s

toJSON() method rather than stringifying the Object. Although the use of toJSON() is legal, it’s probably

a bad idea. toJSON() defeats the whole purpose of JSON.stringify(), because the developer is now

responsible for serializing the entire Object structure. This could work with simple Objects such as speaker

(as currently defined), but you’ll end up writing lots of code to serialize more complex Objects that

contain other Objects.

Originally, JavaScript developers used the eval() function to parse JSON.

eval() takes a String parameter that could be a JavaScript expression, a statement, or a sequence of

statements. Consider Example 2-4.

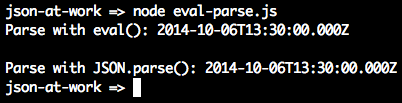

varx='{ "sessionDate": "2014-10-06T13:30:00.000Z" }';console.log('Parse with eval(): '+eval('('+x+')').sessionDate+'\n');console.log('Parse with JSON.parse(): '+JSON.parse(x).sessionDate);

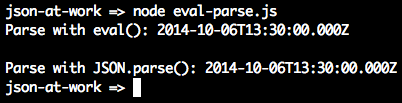

Running the preceding file yields the following:

In this case, both eval() and JSON.parse() work the same and parse the date properly. So what’s the

problem? Let’s look at another example with a JavaScript statement embedded in the String; see Example 2-5.

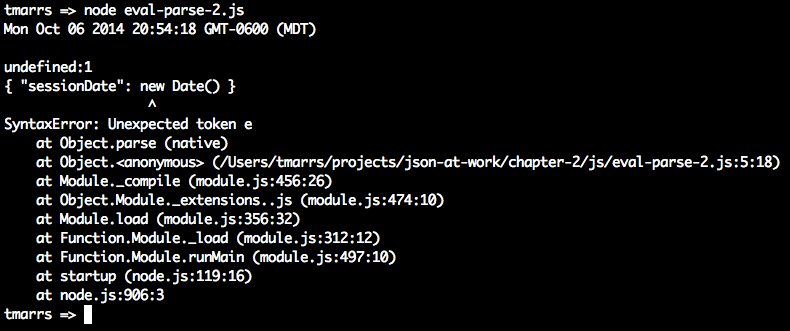

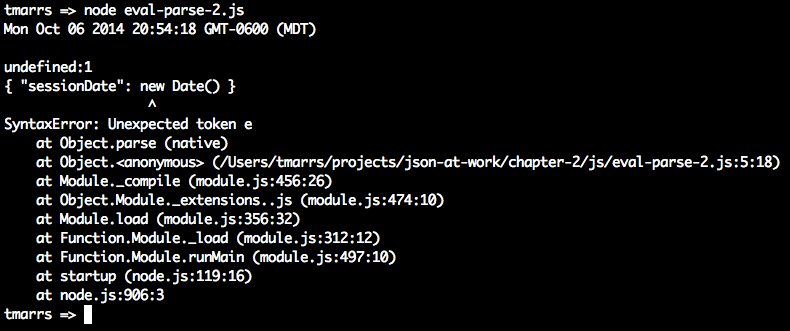

varx='{ "sessionDate": new Date() }';console.log('Parse with eval(): '+eval('('+x+')').sessionDate+'\n');console.log('Parse with JSON.parse(): '+JSON.parse(x).sessionDate);

When we run this, we now see the following:

We passed in text that contains a JavaScript statement, new Date(), and eval() executes that statement.

Meanwhile, JSON.parse() correctly rejects the text as invalid JSON. Although we passed in only a fairly

innocuous statement to create a Date, someone else could pass in malicious code and eval() would still

execute it. Even though eval() can be used to parse JSON, it is considered a bad/unsafe practice because

it opens the door to any valid JavaScript expression, leaving your application vulnerable to attacks. Because of this security issue, the eval() function has been deprecated (for parsing JSON) in favor of JSON.parse().

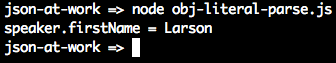

Let’s return to our Speaker example, and use JSON.parse() to deserialize a JSON String into a speaker

Object, as shown in Example 2-6.

varjson='{'+// Multi-line JSON string.'"firstName": "Larson",'+'"lastName": "Richard",'+'"email": "larsonrichard@ecratic.com",'+'"about": "Incididunt mollit cupidatat magna excepteur do tempor ex non ...",'+'"company": "Ecratic",'+'"tags": ['+'"json",'+'"rest",'+'"api",'+'"oauth"'+'],'+'"registered": true'+'}';// Deserialize JSON string into speaker object.varspeaker=JSON.parse(json);// Print 2nd speaker object.console.log('speaker.firstName = '+speaker.firstName);

When we run this file, we get the following:

JSON.parse() takes a JSON String as input and parses it into a fully functional JavaScript Object. We’re

now able to access the speaker Object’s data members.

So far, we’ve shown how core JavaScript Data Types and simple Object Literal–style JavaScript Objects interact with JSON. But we’ve glossed over some details, and now it’s time to go a bit deeper. There are several ways to create (or instantiate) JavaScript Objects, and we’ll focus on Object Literal form because this type of Object is the one that is the closest match to a JSON Object.

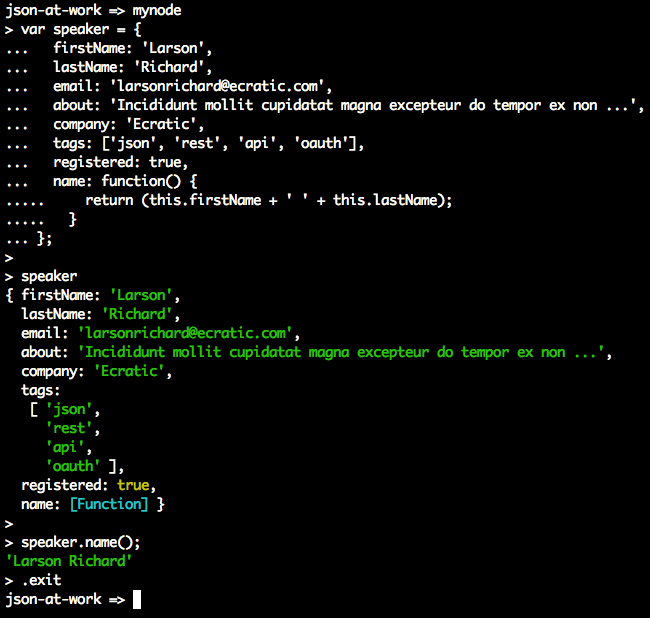

We’ve already shown the speaker Object in Object Literal form, but we’ll show it again

in Example 2-7 for reference.

varspeaker={firstName:'Larson',lastName:'Richard',:'larsonrichard@ecratic.com',about:'Incididunt mollit cupidatat magna excepteur do tempor ex non ...',company:'Ecratic',tags:['json','rest','api','oauth'],registered:true,name:function(){return(this.firstName+' '+this.lastName);}};

With Object Literal syntax, you define an Object’s properties (both data and functions) inside the curly

braces. In the preceding example, the speaker Object is instantiated and populated with data. If you never

need to create another instance of the speaker Object in your application, Object Literal is a good

approach because it provides a simple yet modular way to group an Object’s data and functionality. The real

drawback to the Object Literal approach is that you can create only one instance of speaker, and you can’t

reuse the name() method.

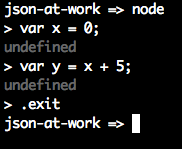

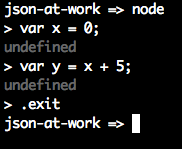

So far we’ve been using Node.js from the command line to execute JavaScript files. Let’s change things up a bit and start using Node.js’s interpreter, the Request-Eval-Print-Loop (REPL), instead. The REPL is really great because it provides instant feedback on your code, and enables you to iteratively debug and improve your application. You can find in-depth coverage of the REPL in the Node.js documentation. But nothing is perfect, and neither is the REPL. One of my pet annoyances is the following:

For each statement that doesn’t produce output, the interpreter outputs undefined. Many people find this distracting, and there’s a way to turn it off. See Appendix A (“Taming the REPL—mynode”) to configure a command alias I affectionately call mynode that I

find easier to work with than the standard Node.js REPL.

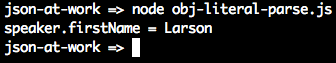

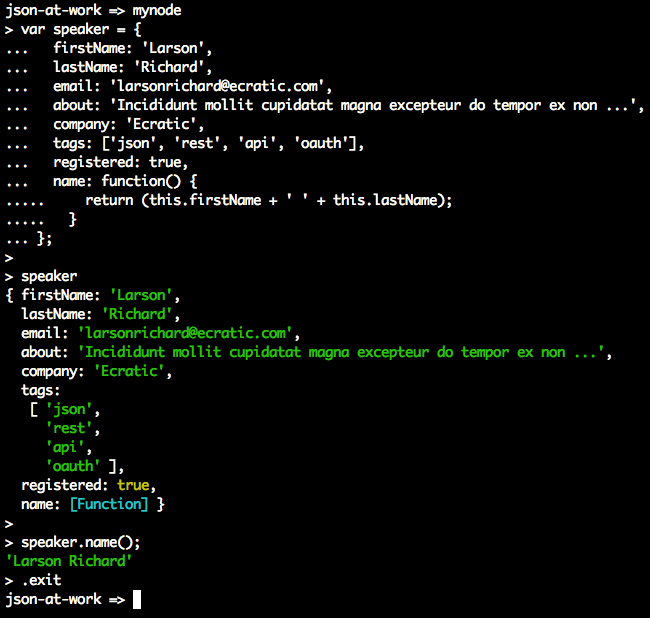

Without further ado, let’s work with our speaker Object by using the mynode REPL:

In this run, you’ll notice that we can interact with the speaker Object by calling its methods and

viewing the results in the interpreter.

Here are some of the commands you’ll need to use the REPL:

.clear Clear the context of the REPL session.

.breakGo back to the REPL prompt. Use this to break out of a multiline statement.

.exit Exit the REPL session.

.save Save the REPL session to a file.

We’ve glossed over many details of Object-Oriented JavaScript, and there are several other ways to interact with objects. We’ve shown just enough OO here so that we can work with JavaScript Objects and JSON in a meaningful way within an application. Complete, in-depth coverage of JavaScript Objects is far beyond the scope of this book. To gain a deeper understanding, here are a few excellent resources:

Now that you know how to serialize/deserialize JSON to/from a speaker Object, we’re ready to run a simple

server-side Unit Test against a Stub API provided by json-server. We’ll also use this Stub API when we later

create a small web application.

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is an approach that uses Unit Testing to drive development. Here’s a typical flow:

Write some tests.

Run the tests, which fail because there isn’t any code.

Write just enough code to make the tests pass.

Refactor the code to improve design and flexibility.

Rerun tests and fix code until all tests pass.

TDD-style Unit Tests tend to be procedural.

Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) is an approach that tests a User Story based on acceptance criteria and expected outcomes. BDD-style tests read like English sentences; for example: “Speakers should receive their payment from the Conference within 30 days.” For more information on BDD, please see Dan North’s excellent article, “Introducing BDD”. Some people see BDD as a refinement to TDD, and I tend to agree because a developer would follow the same workflow as TDD.

Both BDD and TDD are solid approaches, and can be combined to form a robust test suite for an application. The Unit Tests in this chapter use a BDD-style approach for assertions.

Here are the tools for our server-side Unit Test:

Mocha is a JavaScript Unit Test framework that runs in both Node.js and a browser. We’ll leverage Mocha from the command line within a Node.js project, and add a few features to support JSON-based API testing. You can find more details at the Mocha website.

Chai is an assertion library that complements JavaScript testing frameworks and adds a richer set

of assertions, in this case to Mocha. Chai enables developers to write TDD or BDD style tests. The tests in this chapter use the expect (BDD) assertion

style, but you’re free to experiment with the should (BDD) or assert (TDD) assertion styles. Use the

approach that makes you comfortable. For more details on Chai, visit the Chai Asssertion Library website.

Before going further, please be sure to set up your test environment. If you haven’t installed Node.js yet, see Appendix A, and install Node.js (see “Install Node.js” and

“Install npm Modules”). If you want to follow along with the Node.js project provided in the code

examples, cd to chapter-2/speakers-test and do the following to install all dependencies for the

project:

npm install

If you’d like to set up the Node.js project yourself, follow the instructions in the book’s GitHub repository.

Our Unit Test will invoke an API with HTTP, so we’ll include Unirest in our testing repertoire. Unirest is an open source cross-platform REST client provided by the Mashape team. There are implementations in JS, Node.js, Ruby on Rails (RoR) and Java. Unirest is simple and works well in any client code that makes HTTP calls to REST APIs, but it’s also great for Unit Testing. Unirest enables cleaner Unit Tests because you can do a one-time setup (e.g., URI, Headers) and then make multiple HTTP calls throughout the test suite. For detailed documentation, visit the Unirest website.

Unirest is great because it’s cross-platform, and the concepts and method signatures are similar regardless of the language implementation. There are other excellent Java-based HTTP libraries (e.g., Apache Commons HTTPComponents HttpClient, but as a polyglot (multilanguage) developer, I prefer Unirest. Please note that Unirest is not just for Unit Tests. It’s widely used as an HTTP client wrapper by APIs (which invoke other APIs), and by web and mobile client applications.

We’ll use the Speaker data from Chapter 1 as our test data and deploy it as a RESTful API. Again, we’ll

leverage the json-server Node.js module to serve up the data/speakers.json file as a Web API. If you need

to install json-server, please refer to “Install npm Modules” section of Appendix A.

Here’s how to run json-server on port 5000 from your local machine:

cd chapter-2/data json-server -p 5000 ./speakers.json

The Unit Test in Example 2-8 shows how to use Unirest to make an API call to the Speaker Stub API provided by

json-server.

'use strict';varexpect=require('chai').expect;varunirest=require('unirest');varSPEAKERS_ALL_URI='http://localhost:5000/speakers';describe('speakers',function(){varreq;beforeEach(function(){req=unirest.get(SPEAKERS_ALL_URI).header('Accept','application/json');});it('should return a 200 response',function(done){req.end(function(res){expect(res.statusCode).to.eql(200);expect(res.headers['content-type']).to.eql('application/json; charset=utf-8');done();});});it('should return all speakers',function(done){req.end(function(res){varspeakers=res.body;varspeaker3=speakers[2];expect(speakers.length).to.eql(3);expect(speaker3.company).to.eql('Talkola');expect(speaker3.firstName).to.eql('Christensen');expect(speaker3.lastName).to.eql('Fisher');expect(speaker3.tags).to.eql(['Java','Spring','Maven','REST']);done();});});});

In this Unit Test, the following occurs:

The test sets up the URI and Accept Header for unirest by using Mocha’s beforeEach() method,

so that setup occurs in only one place in the code. Mocha executes beforeEach() before running

each test (i.e., it) within the context of the describe.

The should return all speakers test is the most interesting, and it works as follows:

req.end() executes the Unirest GET request asynchronously, and the anonymous (unnamed)

function processes the HTTP response (res) from the API call.

We populate the speakers object with the HTTP Response Body (res.body). At this point, the JSON

from the API has already been parsed by Unirest and converted to a corresponding JavaScript Object (in

Object Literal form).

We use Chai’s BDD-style expect assertions to check for expected results:

We have three speakers.

The third speaker’s company, firstName, lastName, and tags match the values in the speakers.json

file.

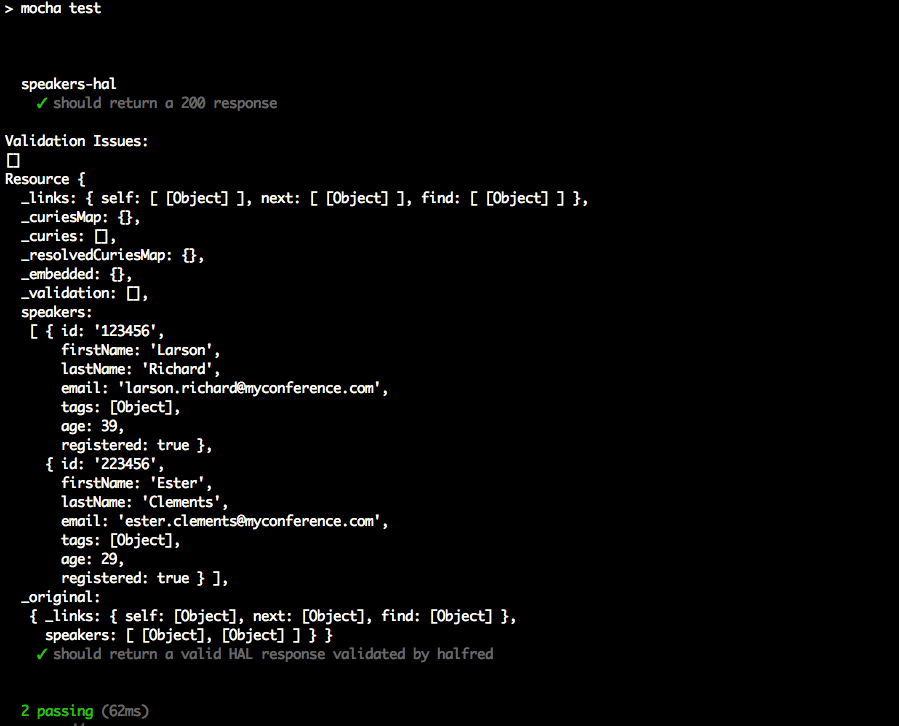

To run this test from the command line (in a second terminal session), do the following:

cd chapter-2/speakers-test npm test

You should see the following results:

json-at-work => npm test

...

> mocha test

...

speakers

✓ should return a 200 response

✓ should return all speakers

2 passing

Now that you know how to serialize/deserialize JSON to/from a speaker Object and how to do a Unit Test

with the Speaker Stub API (on json-server), we’re ready to build a simple web application that

leverages the API data and presents it to a user.

We’ll develop the web application in three iterations:

Iteration 1—generate a basic web application with Yeoman.

Iteration 2—make an HTTP call with jQuery.

Iteration 3—consume Speaker data from a Stub API (with json-server) and use a template.

Yeoman provides an easy way to create (i.e., scaffold) a web application and simplify developer workflow, and is similar to Gradle and Maven (from the Java community), and Ruby on Rails. We’ll use Yeoman to set up, develop, and run the example application. To install Yeoman (which depends on Node.js), refer to Appendix A, and follow the instructions in “Install Yeoman”.

Yeoman provides the following functionality:

Creates the development environment

Runs the application

Automatically reloads the browser when changes are saved

Manages package dependencies

Minifies the application’s code and packages it for deployment

Yeoman follows the philosophy of convention over configuration:

Automates setup

Just works

Uses standardized directory structures

Provides Dependency Management

Assumes reasonable defaults

Encourages best practices

Enables tool-based developer workflow (e.g., test, lint, run, and package)

Please review the following Yeoman tutorials for more information:

Yeoman consists of the following tools:

Yo generates the directory structure and Grunt/Gulp/Bower configuration files for an application.

You can use either Gulp or Grunt to build, run, test, and package an application.

Either Bower or npm can be used to manage and download package dependencies.

Although Grunt is a solid build tool, and npm is an excellent package manager, we’ll use Gulp and Bower for our examples because the Yeoman generator for the web application uses these tools.

Yeoman leverages generators to build and scaffold a project. Each generator creates a default preconfigured boilerplate application. There are over 1,000 generators, and Yeoman provides a complete official list.

Let’s start with a simple application that has no real functionality, and hardcode the Speaker data into

a table. We’ll add the speaker functionality in Iterations 2 and 3. With Yeoman installed, we’ll use the

generator-webapp generator to create our application that comes out-of-the-box with web pages, CSS

stylesheets, Bootstrap 4, jQuery, Mocha, and Chai.

If you’d like to set up the Yeoman project yourself, follow the instructions in the book’s GitHub

repository.

If you want to follow along with the Yeoman project provided in the code examples, cd to

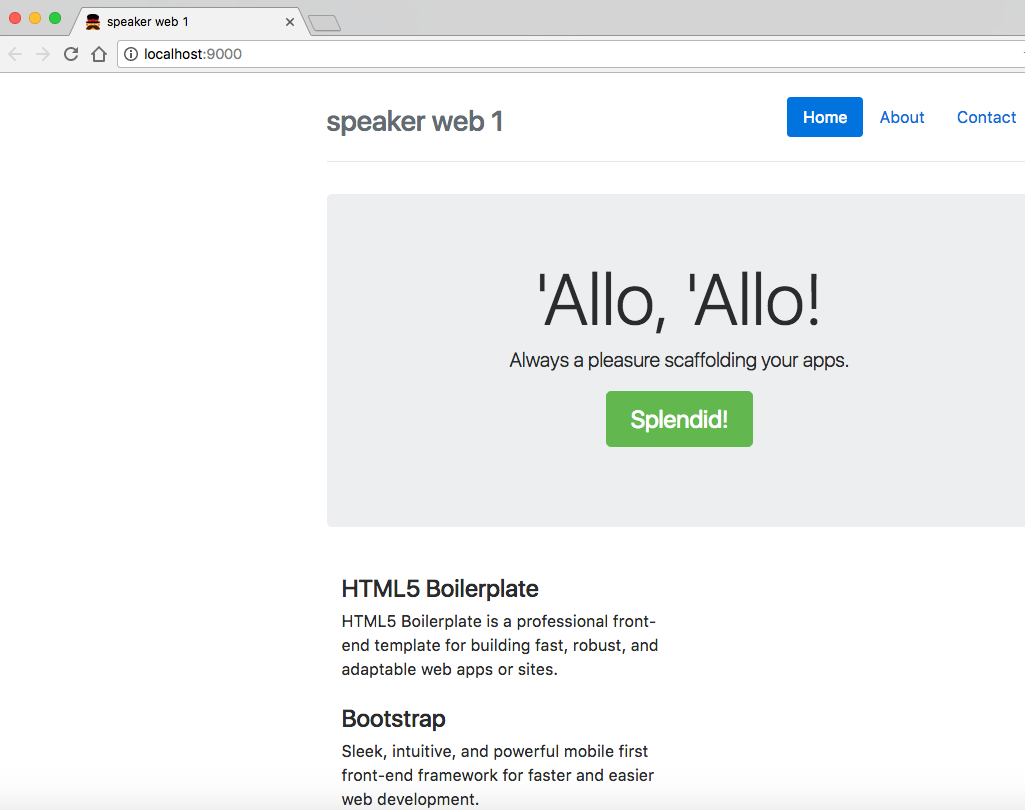

chapter-2/speakers-web-1. In either case, do the following to start the application from the command line:

gulp serve

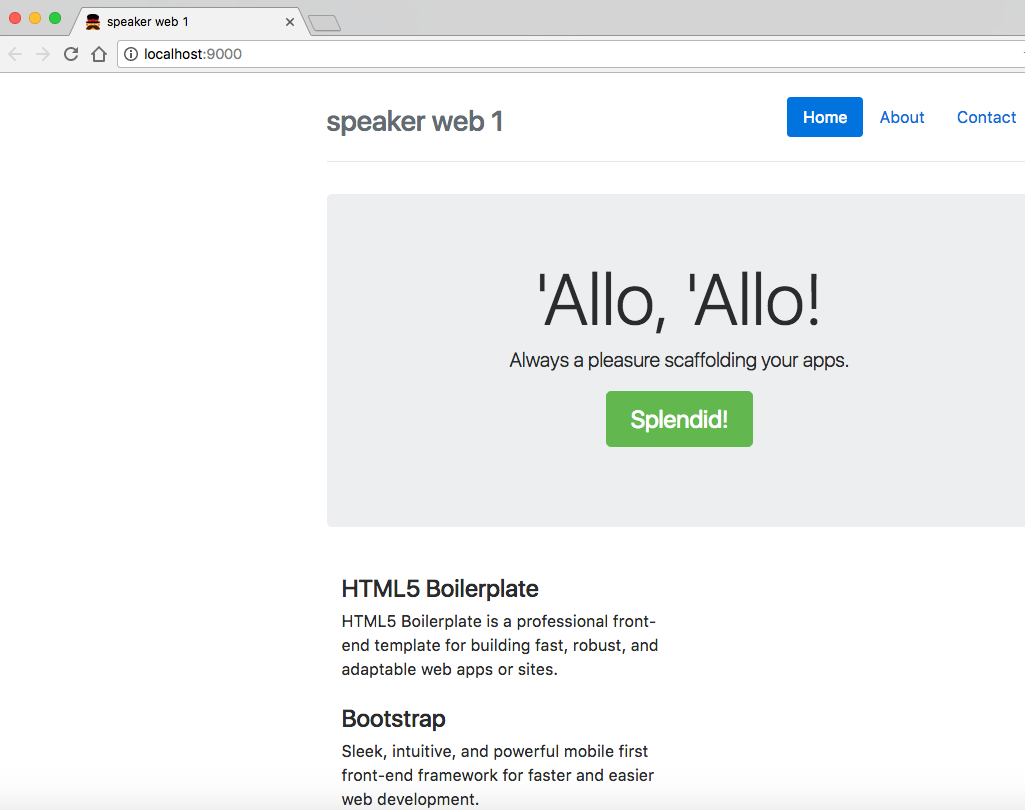

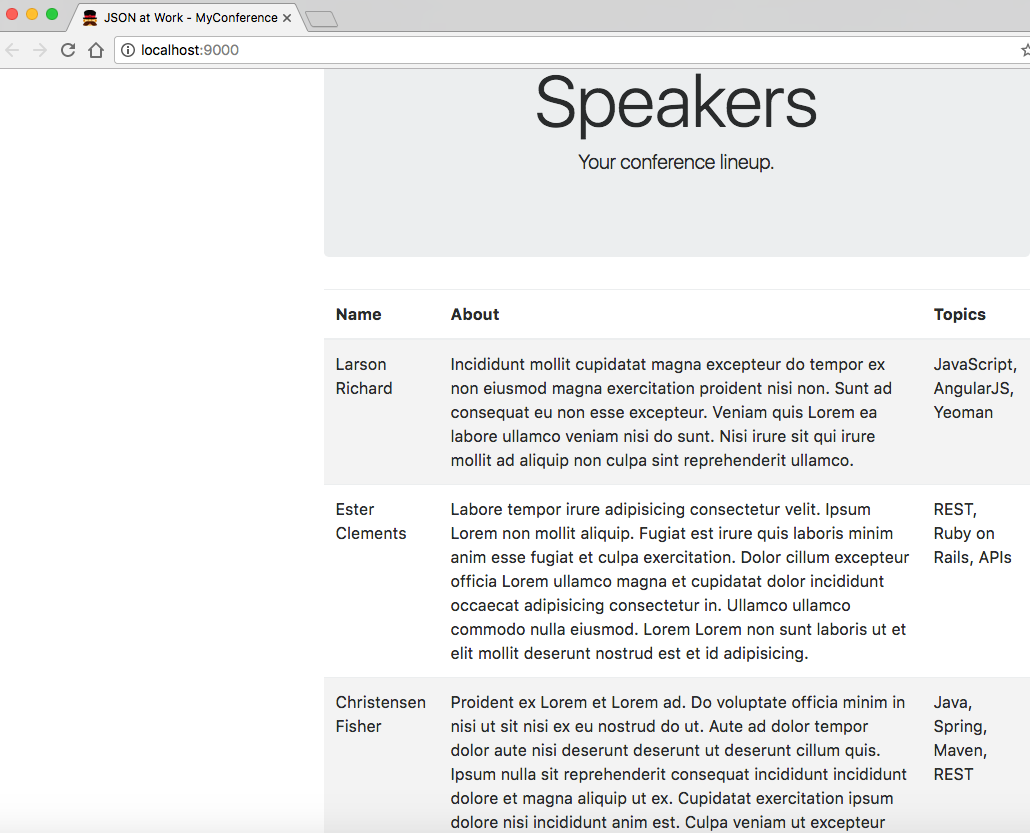

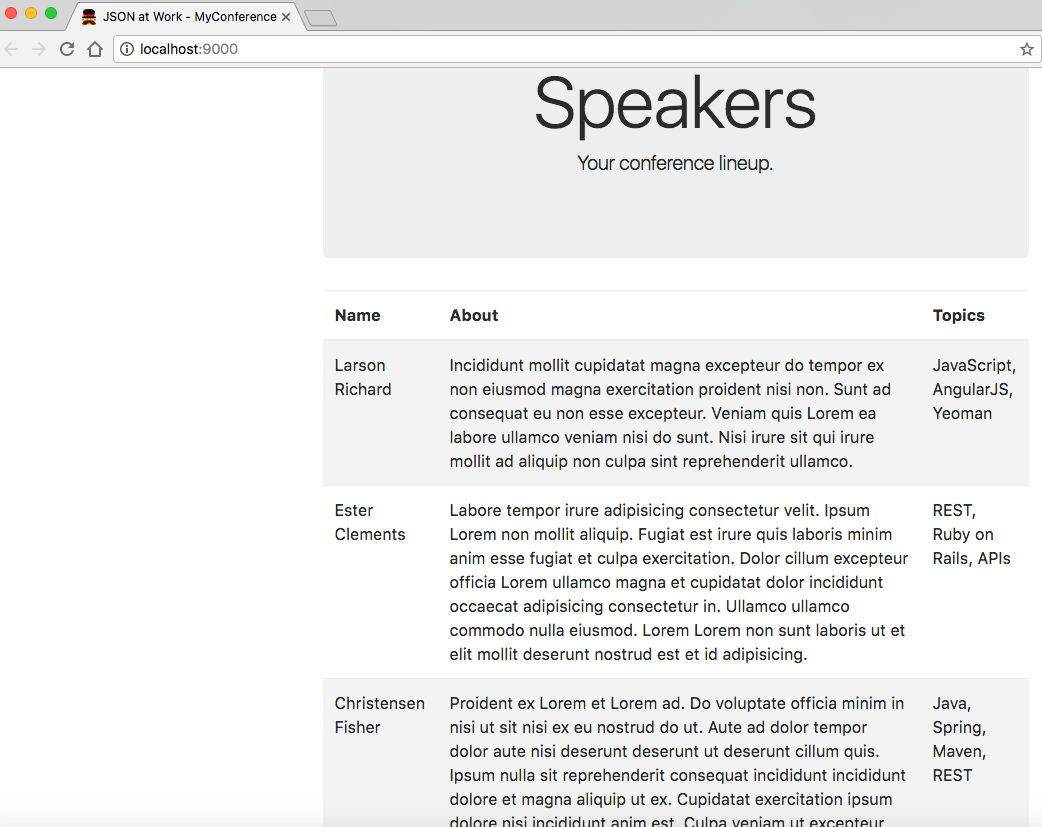

This command starts a local web server and shows the main page (index.html) in your default browser. You should see the page in Figure 2-1 at http://localhost:9000.

Note that if you keep the application running, you can see changes take effect as you save them because this application automatically refreshes with LiveReload.

The generator-webapp Yeoman generator creates a nice starter application, and it’s time to customize

it. First, let’s change the title, Header, and jumbotron (i.e., remove the Splendid! button) in

index.html as shown in Example 2-9.

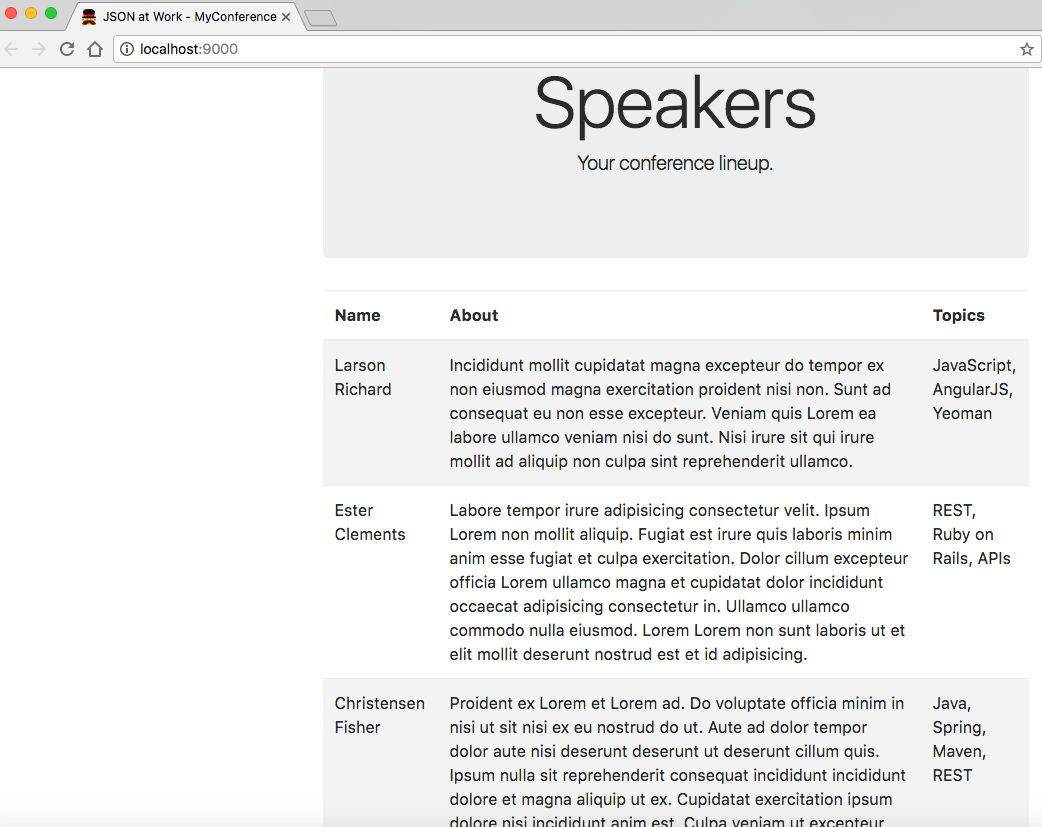

<!doctype html><htmllang=""><head>...<title>JSON at Work - MyConference</title>...</head><body>...<divclass="header">...<h3class="text-muted">JSON at Work - Speakers</h3></div>...<divclass="jumbotron"><h1class="display-3">Speakers</h1><pclass="lead">Your conference lineup.</p></div>...</body></html>

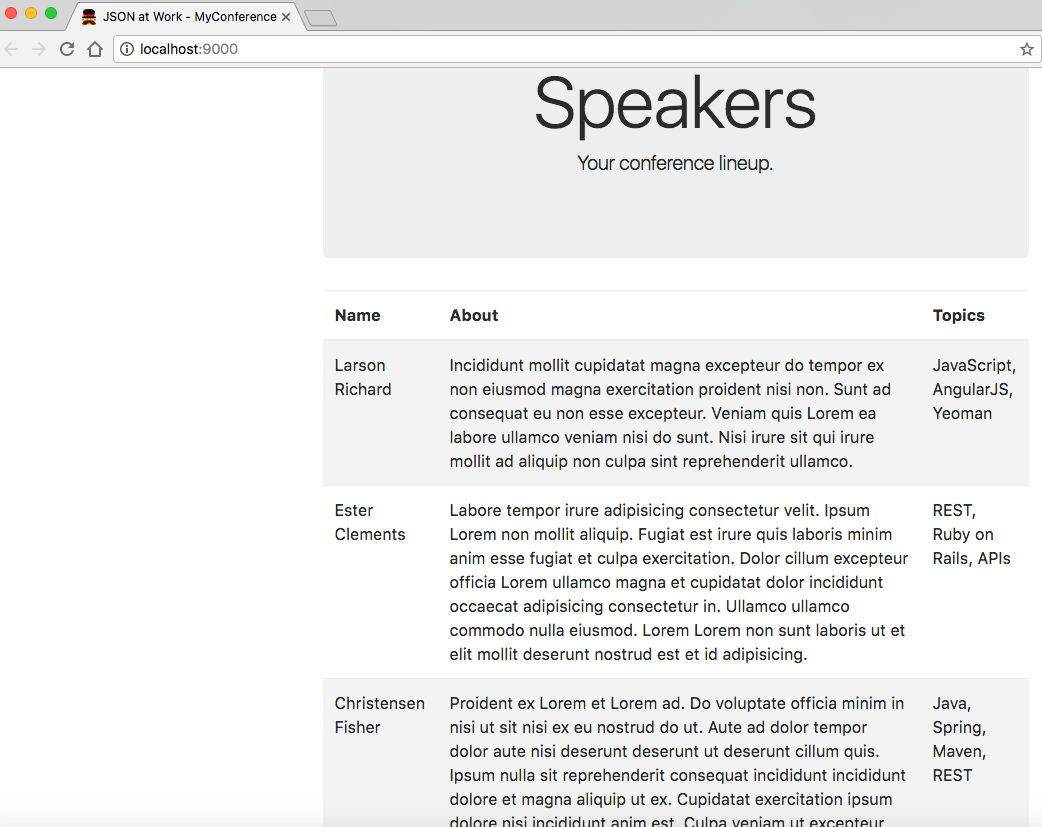

Let’s add a table with some hardcoded Speaker data in the index.html file, as shown in Example 2-10.

<!doctype html><htmllang="">...<body>...<tableclass="table table-striped"><thead><tr><th>Name</th><th>About</th><th>Topics</th></tr></thead><tbodyid="speakers-tbody"><tr><td>Larson Richard</td><td>Incididunt mollit cupidatat magna excepteur do tempor ...</td><td>JavaScript, AngularJS, Yeoman</td></tr><tr><td>Ester Clements</td><td>Labore tempor irure adipisicing consectetur velit. ...</td><td>REST, Ruby on Rails, APIs</td></tr><tr><td>Christensen Fisher</td><td>Proident ex Lorem et Lorem ad. Do voluptate officia ...</td><td>Java, Spring, Maven, REST</td></tr></tbody></table>...</body></html>

We now have a web application that displays the sample Speaker data, as shown in Figure 2-2.

Here are the key application files and directories generated by generator-webapp:

app/ contains the application’s code (for example, HTML, JavaScript, and CSS).

index.html is the application’s main page.

images/ holds the application’s images.

scripts/ is a directory that has the application’s JavaScript (and other scripting language) files.

main.js is the application’s main JavaScript file. We’ll work with this more in Iteration 2.

styles/ is the folder that holds CSS and related styling files.

bower_components/ contains the project dependencies installed by Bower: Bootstrap, jQuery, Mocha, and Chai.

node_modules/ contains the project dependencies required by Node.js, including Gulp.

test/ holds test specs used by the chosen testing framework(s). In this case, we’re using Mocha and Chai.

gulpfile.js is the Gulp build script used to build and run the application.

package.json is used by Node.js to manage dependencies that Gulp needs to execute the project scripts.

dist/ contains build-related artifacts created by gulp build.

To wrap up our discussion on generator-webapp, here are the other important commands you’ll need to know:

Stop the application (the web server).

gulp lint Use lint to validate the JavaScript files in the application.

gulp +serve:test Test the web application. In this case, it runs PhantomJS with Mocha and Chai.

gulp build Build and package the application for deployment.

gulp clean Clean the artifacts generated when testing and building the application.

You can get the full list of commands by typing gulp --tasks at the command line.

Please shut down the web application before moving to Iteration 2.

In Iteration 1, we developed a web application with Speaker data hardcoded in the main page, and now it’s time to add “live” content and functionality.

We’ll take the following steps:

Factor the hardcoded Speaker data out of the main page.

Add a separate JSON file to hold the Speaker data.

Use jQuery to populate the main page with Speaker data from the JSON file.

If you’d like to set up the Yeoman project for Iteration 2 by yourself, do the following:

Follow the instructions in the book’s GitHub repository.

Don’t forget to copy the app/index.html file from Iteration 1.

Or if you want to follow along with the Yeoman project provided in the code examples, cd to

chapter-2/speakers-web-2. In either case, do the following to start the application from the command line:

gulp serve

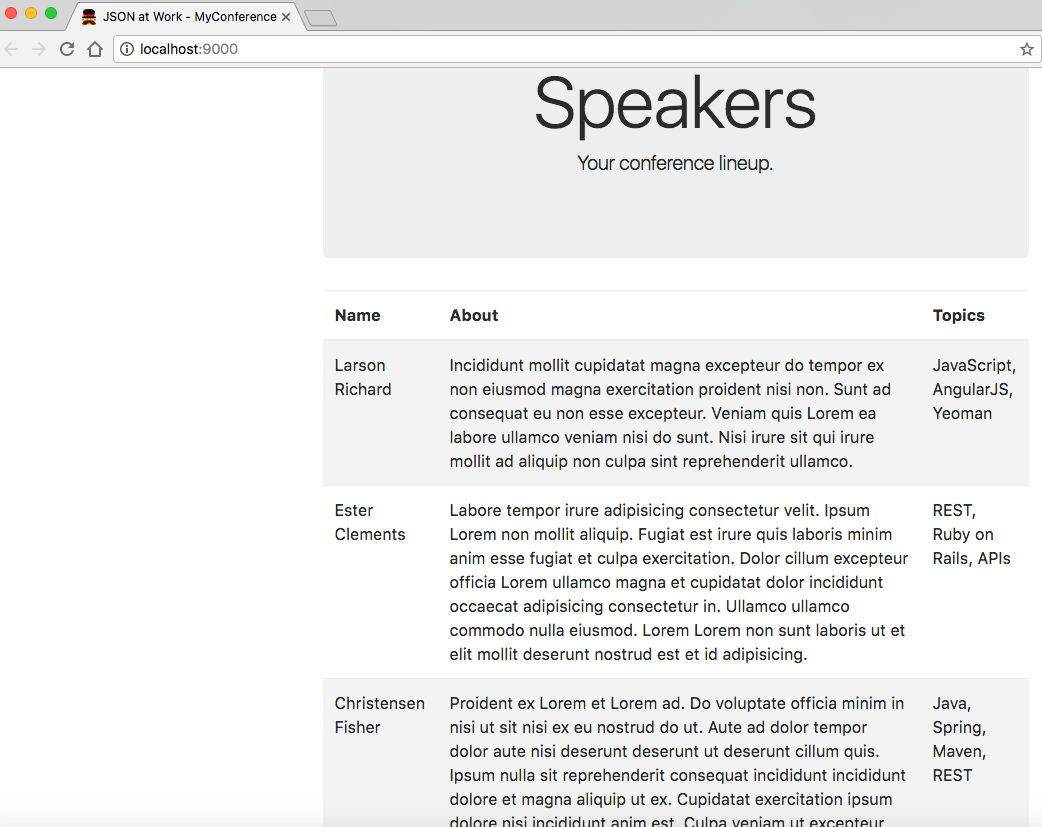

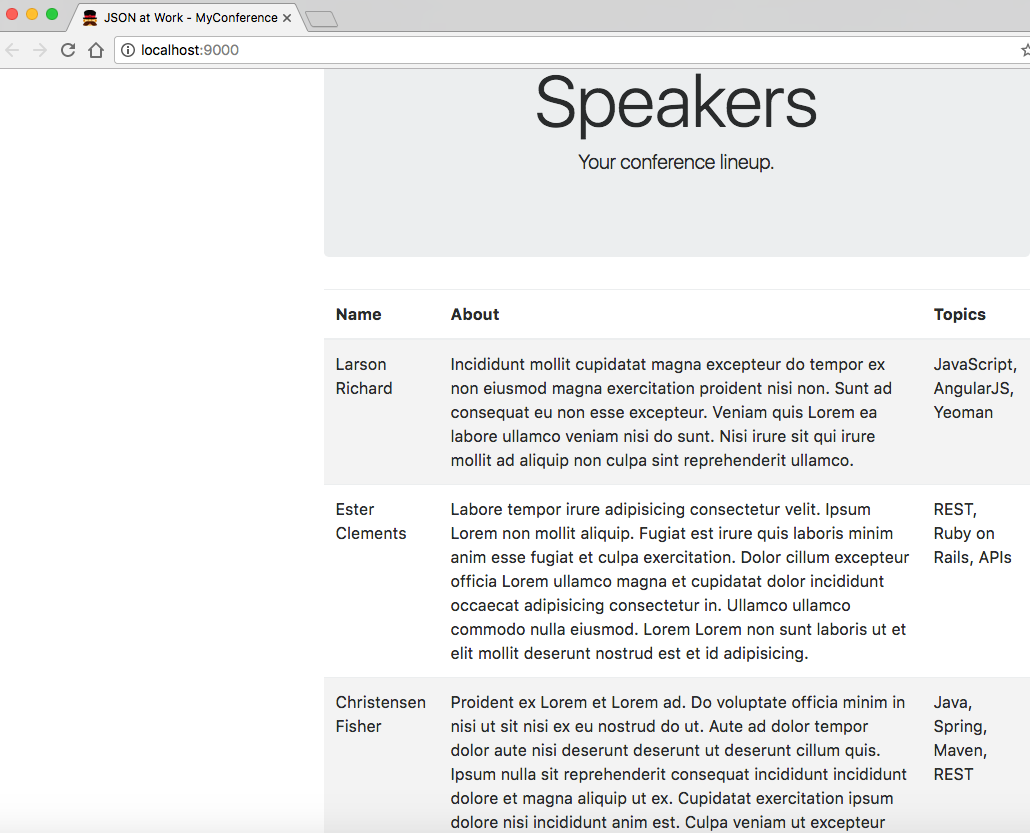

This command starts the local web server as shown in Iteration 1. You should see the page in Figure 2-3 at http://localhost:9000.

This has the hardcoded Speaker data table in the main page (in index.html) that you saw earlier. Please keep the web application running so you can see changes take effect as you save them.

Now, let’s remove the rows from the table body. The HTML for the speakers table now looks like Example 2-11.

<!doctype html><htmllang="">...<body>...<tableclass="table table-striped"><thead><tr><th>Name</th><th>About</th><th>Topics</th></tr></thead><tbodyid="speakers-tbody"></tbody></table>...</body></html>

In this example, we now have an empty table that has only a header row. We use Bootstrap’s

table-striped CSS class so that we’ll have zebra-striped rows. Notice the speakers-tbody ID on the

<tbody> element that holds the table’s content. Later, jQuery will use this ID to populate the table

rows.

We now need a separate JSON file to hold the Speaker data. Please see the new /speakers-web-2/app/data/speakers.json file that has the Speaker data for the application (this was copied from /chapter-2/data/speakers.json).

To complete Iteration 2, the upgraded app/scripts/main.js file now uses jQuery to populate the speakers table with the data from the app/data/speakers.json file, as shown in Example 2-12.

'use strict';console.log('Hello JSON at Work!');$(document).ready(function(){functionaddSpeakersjQuery(speakers){$.each(speakers,function(index,speaker){vartbody=$('#speakers-tbody');vartr=$('<tr></tr>');varnameCol=$('<td></td>');varaboutCol=$('<td></td>');vartopicsCol=$('<td></td>');nameCol.text(speaker.firstName+' '+speaker.lastName);aboutCol.text(speaker.about);topicsCol.text(speaker.tags.join(', '));tr.append(nameCol);tr.append(aboutCol);tr.append(topicsCol);tbody.append(tr);});}$.getJSON('data/speakers.json',function(data){addSpeakersjQuery(data.speakers);});});

In this example, we put the code inside jQuery’s $(document).ready() so that the entire page

(including the DOM) is “ready” (fully loaded). $.getJSON() is a jQuery method that makes an

HTTP GET request on a URL and converts the JSON response to a JavaScript object. In this case, the

app/data/speakers.json file is addressable as a URL through HTTP because it is deployed as a part of the

web application. The $.getJSON() callback method then delegates the job of populating the speakers table

to the addSpeakersjQuery() function.

The addSpeakersjQuery() method loops through the speakers array by using the jQuery .each() method. The

.each() function does the following:

Finds the <tbody> element in the speakers table by using the speakers-tbody ID we showed in the

index.html file

Creates a row and its columns by filling in the <tr> and <td> elements with the data from the

speaker object

Appends the new row to the <tbody> element

For more information on jQuery’s getJSON() function, see the jQuery Foundation website.

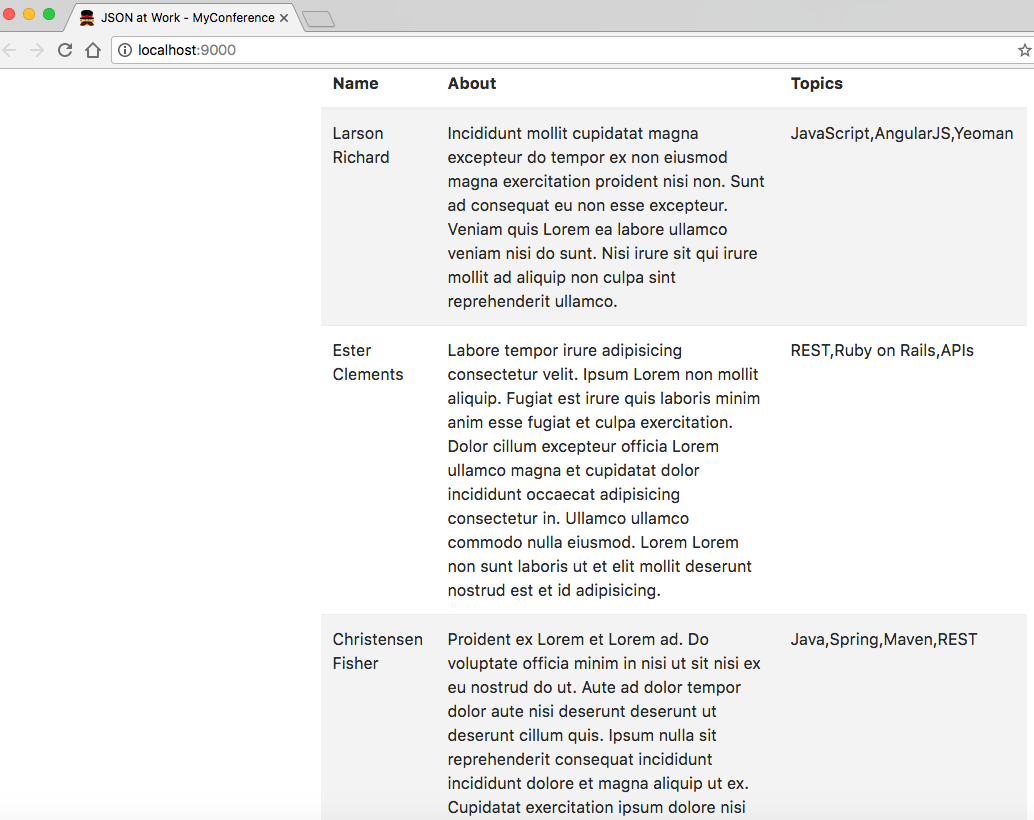

If you kept the web application running, you should now see the screen in Figure 2-4.

The main page looks the same, but we were expecting that. We’ve improved the application by factoring out the hardcoded Speaker data from the main page, and we’re now making an HTTP call. At this point, we have some of the elements of a real web application that populates its pages dynamically, but here are the drawbacks:

The JSON data comes from a file within the web application, and we want it to come from a RESTful API.

The JavaScript code knows about HTML elements on the main page. We would like to reduce the amount of HTML and DOM manipulation.

Please shut down the web application before moving to Iteration 3.

In Iteration 2, we made an HTTP call to populate the main page with Speaker data from a JSON file, and we’re

now going to get the data from the Stub API provided by json-server that was used in Chapter 1. We’re also going to factor the HTML and DOM manipulation out of the JavaScript into an external Mustache

template.

We’ll take the following steps:

Modify the HTTP call to point to the json-server URI.

Use a Mustache template to remove the HTML and DOM manipulation from JavaScript.

If you’d like to set up the Yeoman project for Iteration 2 by yourself, do the following:

Follow the instructions in the book’s GitHub Repository.

Don’t forget to copy the following files from Iteration 2:

app/index.html

app/scripts/main.js

Or if you want to follow along with the Yeoman project provided in the code examples, cd to

chapter-2/speakers-web-3.

Next, let’s modify the HTTP call in main.js to point to the Speaker Stub API (provided by

json-server), as shown in Example 2-13.

...$.getJSON('http://localhost:5000/speakers',function(data){addSpeakersjQuery(data);});...

The code now invokes the Speaker Stub API provided by json-server. Note that data is passed

to addSpeakersjQuery() because json-server doesn’t emit the named speakers Array.

First, open a new terminal session and run json-server on port 5000 from your command line:

cd chapter-2/data json-server -p 5000 ./speakers.json

Start the web application (in another terminal session) from the command line:

gulp serve

This command starts the local web server as shown in Iterations 1 and 2. You should see the same Speaker data when you visit http://localhost:9000 in your browser. But the web application is in better shape because it’s using data from an API rather than a file. Please keep the web application running so you can see changes take effect as you save them.

To complete Iteration 3, let’s factor out the HTML/DOM manipulation from our JavaScript code into a

Mustache template. Mustache bills itself as providing logic-less templates, which means that there are no

control statements (e.g., for or if) needed to generate HTML from JavaScript and other languages.

Mustache works with multiple languages.

Example 2-14 is our Mustache template that generates HTML content based on Speaker data.

<!--[speakers-mustache-template.html]This is the template for items in the speakers array when the app first loads--><scriptid="speakerTemplate"type="text/html">{{#.}}<tr><td>{{firstName}}{{lastName}}</td><td>{{about}}</td><td>{{tags}}</td></tr>{{/.}}</script>

Note the following about this example:

The template is an external file to keep the HTML out of our JavaScript code.

The template code resides within a <script> element.

The HTML is structured just as it would be in a regular web page.

Mustache fills in the data by using variables enclosed in double parentheses.

The context enables Mustache to loop through the Array of Speaker data. We have an anonymous (nameless) collection that we received from the HTTP call, so we enclose all our elements within a

beginning {{#.}} and closing {{/.}} to set the context. Note that if we had a named Array

(e.g., speakers), the context would begin with {{#speakers}} and end with {{/speakers}}.

Each variable represents a field name within the specified context. For example, the {{firstName}}

variable gets data from the firstName field for the current element in the Speaker data Array.

Please review Wern Ancheta’s excellent article, “Easy Templating with Mustache.js” for a deeper discussion on Mustache.

Besides Mustache, a couple of other solid templating libraries are frequently used by the JavaScript community:

This is a general utility library, but it includes some templating functionality.

In addition, most MVC frameworks (AngularJS, Ember, and Backbone) have some form of templating. We’ll cover Mustache and Handlebars more thoroughly in Chapter 7.

Example 2-15 shows our refactored app/scripts/main.js file that now uses Mustache.

'use strict';console.log('Hello JSON at Work!');$(document).ready(function(){functionaddSpeakersMustache(speakers){vartbody=$('#speakers-tbody');$.get('templates/speakers-mustache-template.html',function(templatePartial){vartemplate=$(templatePartial).filter('#speakerTemplate').html();tbody.append(Mustache.render(template,speakers));}).fail(function(){alert("Error loading Speakers mustache template");});}$.getJSON('http://localhost:5000/speakers',function(data){addSpeakersMustache(data);});});

In this example, the addSpeakerMustache() function converts the Speaker data (that we received from

json-server) into HTML by using our Mustache template. We use the jQuery’s $.get() method to pull in the external

Mustache template. When the $.get() call completes, we then find the main page’s <tbody> element (just

as before) and then use the append() method to append the HTML content that was created by

Mustache.render() (based on the template and Speaker data).

But we’re not quite done, because we need to add Mustache to the web application:

Use Bower to install Mustache into the web application. From the command line in the

speakers-web-3 directory, type bower install mustache.

Add Mustache to app/index.html (right after main.js) as shown in Example 2-16.

<!doctype html><htmllang="">...<body>...<scriptsrc="bower_components/mustache.js/mustache.js"></script>...</body></html>

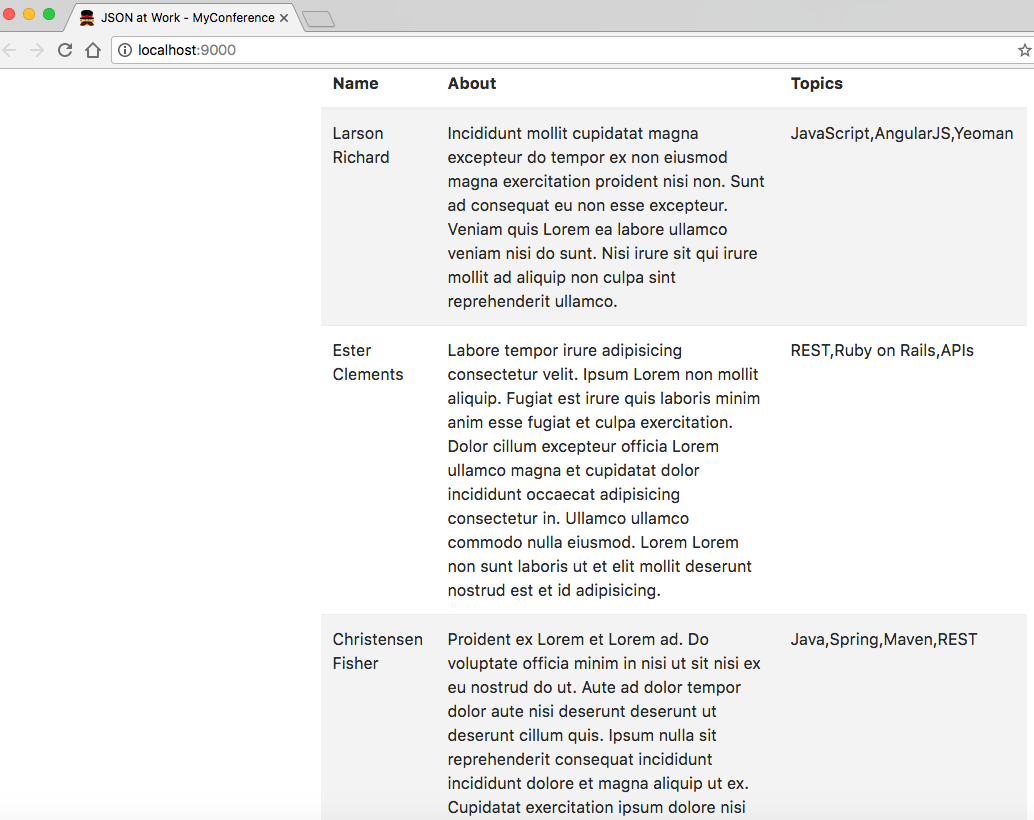

If you kept the web application running, you should now see the screen in Figure 2-5.

Notice that Mustache formats the Speaker data a little differently, but we improved the web application

by making an API call to the Stub API (provided by json-server) and by templating the HTML with Mustache.

Of course, you can go further by using AngularJS or React, but this is left as an exercise for you.

Please don’t forget to shut down both the web application and json-server with a Ctrl-C in each

terminal session.

A deeper, more thorough knowledge of JavaScript is needed to truly understand Node.js and other JavaScript frameworks (e.g., Angular, React, Ember, Backbone, etc.), and package/build management tools such as Yeoman. If JavaScript Objects are new to you, and all the curly braces, parentheses, and semicolons are a boiling sea of syntax, then take heart because you are not alone. Every JavaScript developer encounters these issues along their path.

Here are a few websites where you can go to deepen and broaden your skills:

JavaScriptIsSexy provides excellent, freely available tutorials to help you reach an intermediate or advanced level. The main tutorials include these three:

As you work through these (and similar) resources, Objects and Functional Expressions will become commonplace as you reach the intermediate-to-advanced level of JavaScript. At that point, you will have a much more enjoyable and productive experience when developing with current JavaScript tools and frameworks.

We started with simple conversion between JavaScript and JSON and went all the way to develop a working web

application and a Unit Test that makes a RESTful API call to json-server. For the sake of brevity and

clarity, we’ve covered “just enough” of several technologies for you to understand core concepts and build simple

applications. But we’ve just scratched the surface of JavaScript, Node.js, and Yeoman.

Now that we’ve developed a web application with JavaScript and JSON, we’ll move on to use JSON with Ruby on Rails in Chapter 3.

We’ve shown how to use JSON in JavaScript, and in this chapter we’ll show how to use JSON with our second platform—Ruby on Rails (RoR).

We’ll cover the following:

Performing Ruby/JSON serialization/deserialization with MultiJson

Working with Ruby Objects and JSON

Understanding the importance of JSON camel casing

Using JSON with Minitest

Making RESTful API calls and testing the results with Minitest and jq

Building a simple JSON-based API with Rails 5

In our examples, we’ll make RESTful API calls to work with the data we deployed on json-server in

Chapter 1. We’ll then create a more realistic JSON-based Web API. But before we develop a

RESTful API, let’s start with the fundamentals of converting between Ruby and JSON.

Before we go any further, let’s start building our development environment by installing RoR. Please go to Appendix A, and follow the instructions in “Install Ruby on Rails”.

Several good JSON gems provide Ruby/JSON serialization/deserialization functionality, including these:

JSON The default JSON gem provided in Ruby.

oj Optimized JSON, considered by many to be the fastest Ruby-based JSON processor available.

yajl Yet Another JSON Library.

There are many other JSON gems in addition to this list, and it’s hard to choose.

Rather than forcing a developer to know how to use each JSON gem,

MultiJson encapsulates this choice by providing a wrapper

that invokes the most common JSON gems on behalf of the caller by choosing the fastest JSON gem that has

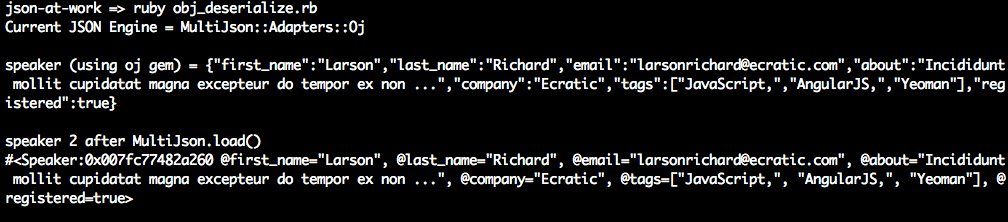

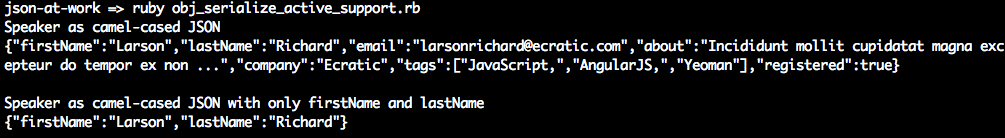

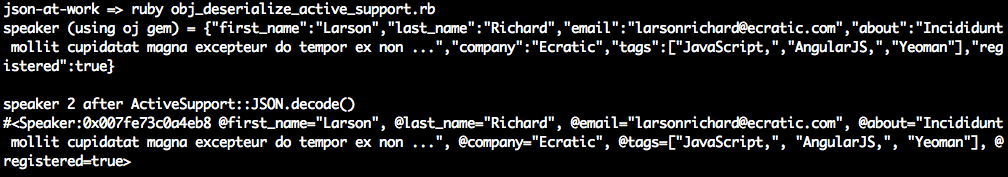

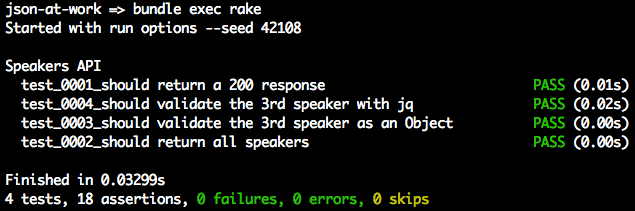

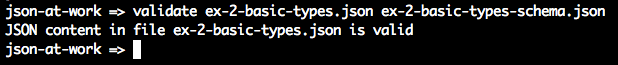

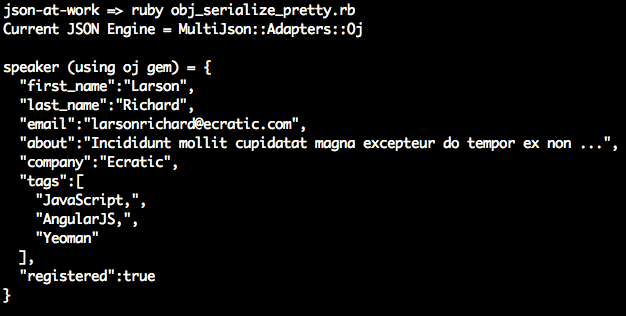

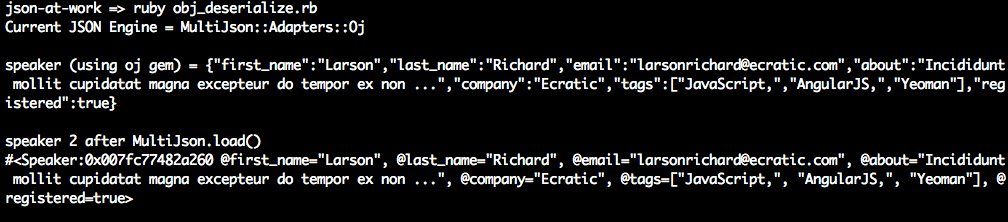

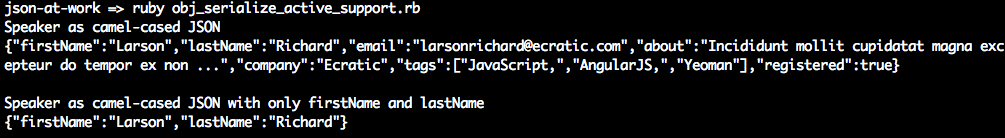

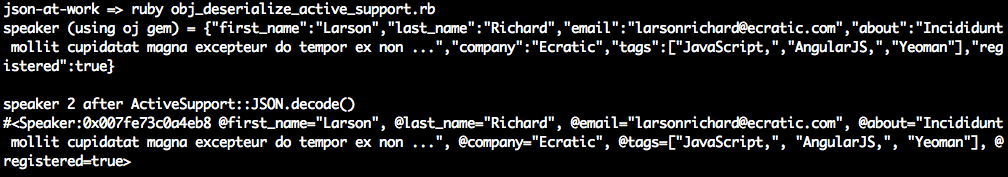

been loaded in an application’s environment. Encapsulating JSON gems like this decouples an application