Chapter 2. Do Not Skip This Chapter

Even if you are familiar with binary numbers, DO NOT SKIP THIS CHAPTER. We are going to begin digging into information theory as well, which is required for understanding the rest of this book.

Understanding Binary

It might seem a bit odd to start a book about data compression with a primer on binary numbers. Bear with us here. Everything in data compression is about reducing the number of bits used to represent a given data set. To expand on this concept, and the ramifications of its mathematics, let’s just take a second and make sure everyone is on the same page.

Base 10 System

Modern human mathematics is built around the decimal—base 10—number system.1

This system makes it possible for us to use the digits [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] strung together to represent number values. Back in elementary school, you might have been exposed to the concept of numeric columns, where, for example, the value 193 is split into three columns of hundreds, tens, and ones.

| Hundreds | Tens | Ones |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

9 |

3 |

Effectively, 193 is equivalent to 1 * 100 + 9 * 10 + 3. And as soon as you grasped that pattern, maybe you realized that you could count to any number.

Later, when you learned about exponents, you were able to replace the “hundreds” and “tens” with their “base ten to the power” equivalents, and a new pattern emerged.

|

102 |

101 |

100 |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

9 |

3 |

So:

193 = 1 * 100 + 9 * 10 + 3 = (1 * 102) + (9 * 101) + (3 * 100)

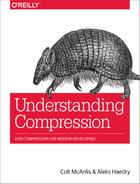

Because each column can contain only a single-digit number, what happens when we add another 1 to 9? Counting up from 9 gives us 10 (two digits). So, we keep the zero in our current 100 column and shift the 1 to the next column to the left, which is 101 and happens to represent “tens.”

As we count up further, we hit 19 + 1 = two tens (2 * 101), and by the time we get to 99, yep, we shift left for 1 * 102.

Binary Number System

The binary number system works under the exact same principles as the decimal system, except that it operates in base 2 rather than base 10. So, instead of columns in the table being powers to the base of ten:

102 | 101| 100

they are powers to a base of two:

22 | 21 | 20

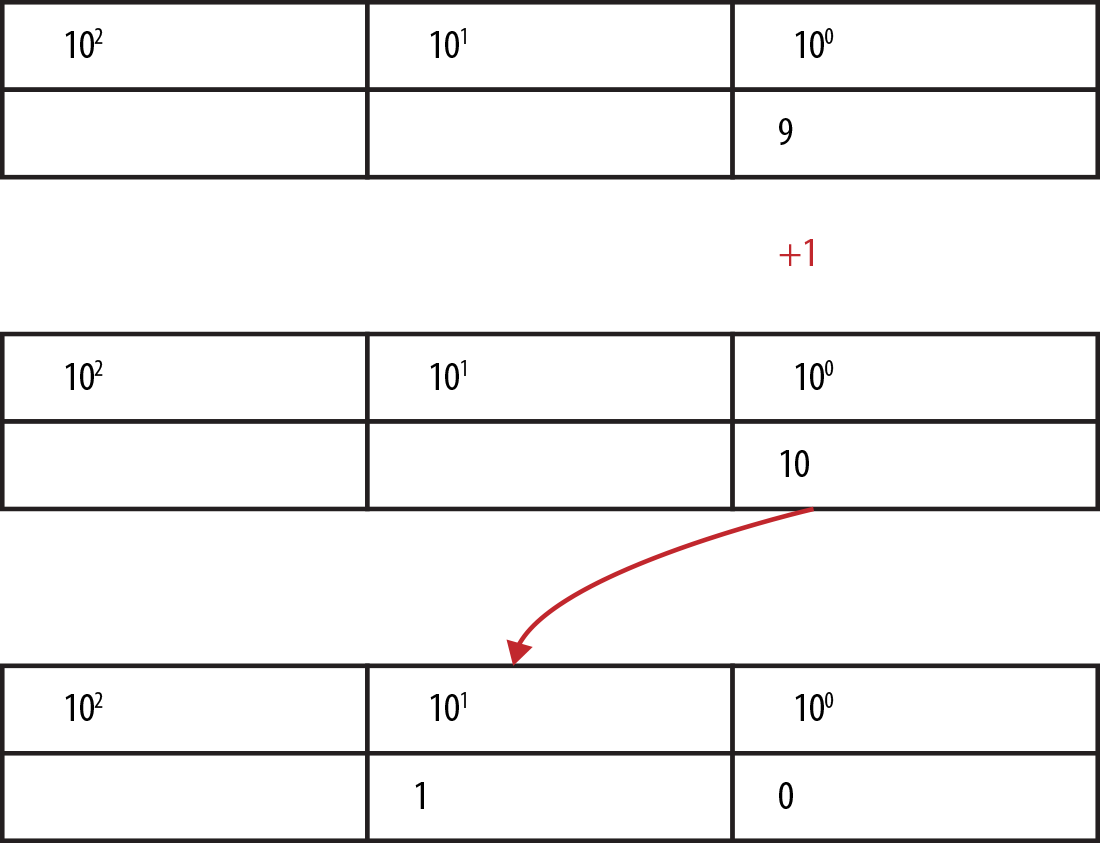

Instead of having available the digits 0–9 before we have to shift, we can only use 0–1.

Counting in binary becomes “zero,” “one,” and because 21 is the next column already, “two” is 1-0, “three” becomes 1-1, and “four,” being 22, shifts us over again to 1-0-0.

Converting from binary to decimal

As you were reading the previous section, we’ll bet that your brain already converted the small binary numbers into their decimal equivalents, because unless you work with binary numbers all the time, you understand the value of a binary number by its decimal equivalent.

Let’s be explicit and say we have the binary number 1010 and fill it into our powers columns.

|

23 |

22 |

21 |

20 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

To get the equivalent decimal number, we add up the values of the columns that have a 1 in them. The preceding table yields the following:

23 + 21 = 8 + 2 = 10

Thus, binary 1010 equals decimal 10.

Conversion from binary to decimal is straightforward. Converting from decimal to binary is a little more complicated.

Converting from decimal to binary

An easy method for converting a decimal number to its binary equivalent is to repeatedly divide it by two and string together the remainders, which are either “1” or a “0.”

This is easiest understood by doing. So, let’s convert the decimal number 294 into its binary-number equivalent using that method.

-

We begin by dividing 294 by 2, which gives us 147 with a remainder of 0.

-

We divide the result 147 by 2, which is 73 plus a reminder of 1.

-

Dividing 73 by 2, we continue to build up the table that follows.

Note that if the decimal number being divided is even, the result will be whole and the remainder will be equal to 0. If the decimal number is odd, the result will not divide completely, and the remainder will be a 1.

| Number as it’s divided by 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 294 | Column equivalent | ||

|

147 |

remainder |

0 (LSB) |

20 |

|

73 |

remainder |

1 |

21 |

|

36 |

remainder |

1 |

22 |

|

18 |

remainder |

0 |

23 |

|

9 |

remainder |

0 |

24 |

|

4 |

remainder |

1 |

25 |

|

2 |

remainder |

0 |

26 |

|

1 |

remainder |

0 |

27 |

|

0 |

remainder |

1 (MSB) |

28 |

Now arrange all the remainders from right to left, with the least significant bit (LSB) on the right, and the most significant bit (MSB) on the left:

100100110

There you have it: 100100110 is the binary equivalent of decimal 294, obtained using the divide-by-2 decimal-to-binary conversion technique.

Information Theory

Now that we’re all on the same page with the binary system, let’s talk about what this means in the context of information theory.

- in·for·ma·tion the·o·ry

-

(noun)

the mathematical study of the coding of information in the form of sequences of symbols, impulses, etc., and of how rapidly such information can be transmitted, e.g., through computer circuits or telecommunications channels.

According to information theory, the information content of a number is equal to the number of binary (yes/no) decisions that you need to make before you can uniquely identify that number in a set.

An Excursion into Binary Search

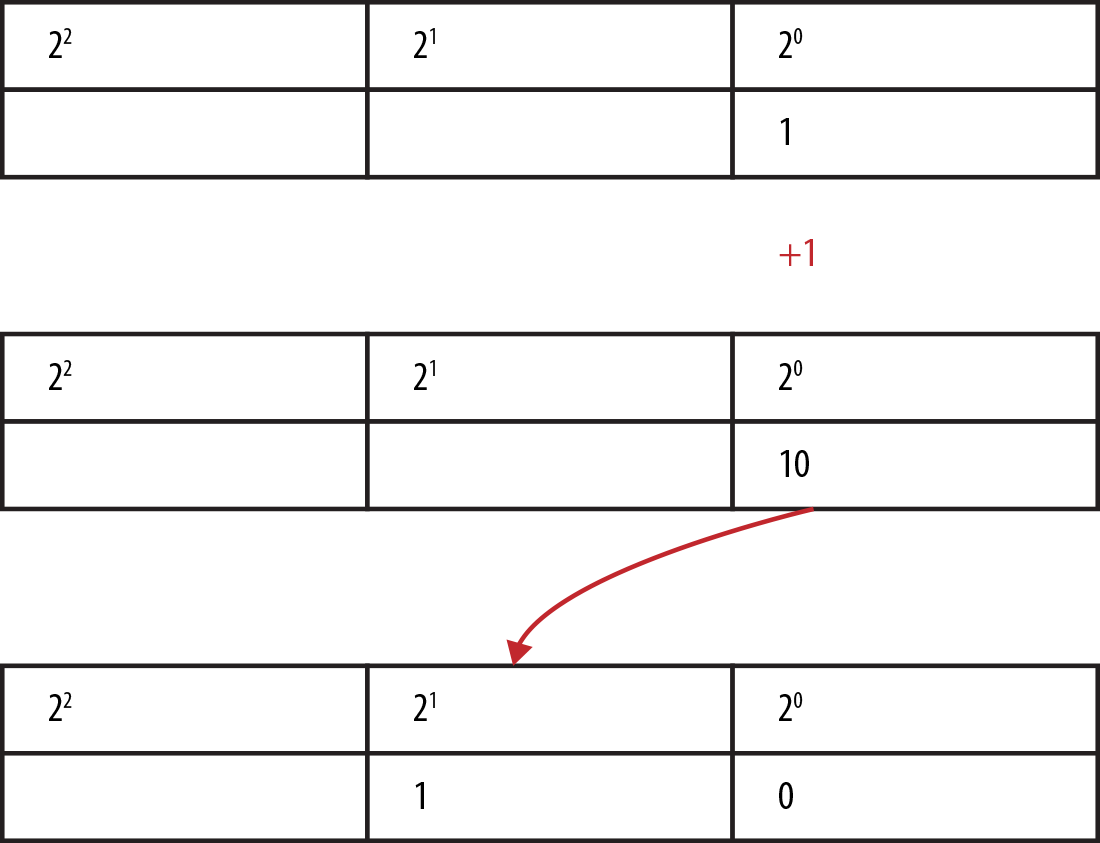

Suppose that we’re given a sorted range of numbers in an array, say 0–15, and we’d like to find where the number 10 exists in the array.

The binary search algorithm works by dividing the data set in the array in half, and determining if 10 is greater or smaller than the pivot value at the center.2 Depending on the result of this decision, we split the array and keep the part of the data set that contains 10. We then compare to the new pivot value and split again. We keep splitting until all we have left is the number 10. (If this sounds a little bit like playing 20 Questions, that’s because it is!)

Now, while searching for the number, each time we decide on greater or smaller, let’s output a single bit to a stream, to represent which decision we’ve made (0 for smaller, 1 for greater).

This is much easier to understand when you do it, so let’s play this out in a fancy diagram, which you can see in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. Binary search on a restricted number space. When we keep a log of the decisions (high/low) at each level, we end up with the binary version of the number.

The resulting output stream is the binary value 1010, which interestingly enough, is exactly the binary representation for the number 10. We were able to represent the number by logging how many yes/no decisions we needed to uniquely describe it, in the given set of data with length 2n – 1.

Tip

If you want to be left alone at a party, start talking to people about this topic. It’s a sure-fire way to become the awkward person standing near the chips and dip.

Entropy: The Minimum Bits Needed to Represent a Number

So, given a random integer value, we can convert that value to binary form. Sadly, though, if given a number, it’s not instantly obvious how many bits it will require without going through the process of binary conversion. This is a boring process, but thankfully, mathematics has produced a formula that makes it easier for us:3

log2(x) = -(log(x) / log(2)) = number of binary digits needed to represent a number

Mathematically speaking, log2 will return a floating-point number.

For example, log2(10) = 3.321 bits.

Technically speaking, you can’t represent 3.321 bits on modern computer hardware (because we can’t represent fractions of bits), so we are forced to round up to the next whole integer, using the ceil (or ceiling) function, updating our formula like so (this is a spiffed-up version, so we are going to use spiffed-up capital letters to make the distinction):

LOG2(x) = ceil(log(x) / log(2))

Of course, now there is another problem: technically, we’re off by one bit for powers of two.

Take the number 2 (or any power of 2 for that matter):

LOG2(2) = ceil(log(2) / log(2)) = 1

LOG2(4) = ceil(log(4) / log(2)) = 2

The result is true from a mathematics perspective, but fails in the fact that we need two and three bits to represent the numbers 2 (bin = 10) and 4 (bin = 100) on our system. As such, we add a slight skewing to our method to ensure that our log results are accurate for powers of two.

LOG2(x) = ceil(log(x+1) / log(2))

Just to help you understand this concept a bit more, here’s a table that displays some interesting data about LOG2 and the number of bits required to represent numbers:

|

Value |

LOG2(value) |

Binary value |

|---|---|---|

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

3 |

2 |

11 |

|

4 |

3 |

100 |

|

7 |

3 |

111 |

|

15 |

4 |

1111 |

|

255 |

8 |

11111111 |

|

65535 |

16 |

1111111111111111 |

|

9.332622e+157 |

525 |

……. |

So, given any decimal integer number, we can easily determine the minimum number of bits needed to represent it in binary by calculating its LOG2. Shannon defined this LOG2 of a variable as its entropy, or rather, the least number of bits required to represent that value.

Standard Number Lengths

The LOG2 form of numbers is efficient but not practical for the way we build computer components.

The issue lies between representing the number in the least bits possible, confusion on how to decode a binary string of numbers (without knowing their LOG2 lengths), and performance in hardware execution.

Modern computers compromise by using fixed-length buckets of bits for numbers of different sizes. The fundamental bucket is one byte, which is made up of eight bits. And the integer buckets typically available in modern programming languages are a short with 16 bits, an integer with 32 bits, and a long with 64 bits. As such, our decimal number 10, converted to binary as 1010, would be a short and represented as 0000000000001010. This is a lot of wasted bits.

The point here is that the majority of algorithms we use in the development of modern applications all tend to use defined bit ranges rather than the LOG2 size. Which is basically the difference between information theory and implementation practicality. Any bit stream we have will always be rounded up to the next byte-aligned size in computer memory. This can get confusing: for example, when we’ve just saved 7 bits of data, our machine reports that our data still remains the same number of bytes long.

The goal in practical data compression is to get as close as possible to the theoretical limit of compressibility. That’s why, to learn and understand compression algorithms, moving forward with the rest of this book, we will only think in terms of LOG2.

1 For now. We are sure quantum computing or Babylonian counting will change this one day.

2 If the array has an even number of elements, there is not really a center. We just choose whether to go with the left-of-center or right-of-center element. It doesn’t matter which.

3 Sorry about the math, but this one is foundational for all that follows.