Chapter 16. Final Thoughts

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

Isaac Newton

In October 2009, I had never written JavaScript professionally. In fact, I had barely spent more than a few hours playing with the language. At the time I was writing frontend trading systems and other bank software in WPF (Windows Presentation Foundation), a technology I had been involved with at Microsoft. If you had told me that “isomorphic JavaScript” would become this widespread a concept before my original writing on the topic, I surely would have laughed. I want to highlight these facts to remind you that you really don’t know what is possible until you try.

Families of Design Patterns, Flux, and Isomorphic JavaScript

Isomorphic JavaScript was not the main topic of my original blog post on the subject, “Scaling Isomorphic Javascript Code.” The term was just a footnote to contextualize and justify what I thought was a much more impactful software design pattern at the time. The way that developers have adopted the term and abstract concept far more than any concrete software design pattern is fascinating.

Software design patterns evolve in a somewhat similar way to religions: there are multiple interpretations of the core ideas for each pattern, which can lead to vastly different characteristics in each sect. Of course, in the case of software design patterns a sect is really just another concrete implementation of the pattern. I will refer to this principle as the “family of design patterns” principle. Consider arguably the most popular design pattern of all time: MVC (Model–View–Controller). The original implementations of the MVC pattern in SmallTalk at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) bear little resemblance to the Model2-like MVC implementations in Ruby on Rails today. These differences mainly arose because Ruby on Rails is a server-based framework and the original MVC implementations focused on frontend desktop GUIs.

In the face of increasingly isomorphic JavaScript, the design patterns and software architectures needed to evolve. Practically speaking, this shift toward isomorphic JavaScript and one-way immutable data flow has validated the “family of design patterns” principle through the emergence of the Flux family of patterns. Flux has given rise to a plethora of implementations, most of which are isomorphic. The popularity of implementations has correlated with their capacity to support both client-side and server-side rendering. The rise of React, Flux, and popular implementations like Redux has validated the importance of isomorphic JavaScript. Indeed, the author of Redux has his own thoughts on the subject.

Always Bet on JavaScript

Since October 2011, when I first mentioned isomorphic JavaScript, there is simply more JavaScript everywhere. If we use the total number of npm modules as a proxy for growth, then there was a over a 50x increase in JavaScript between late 2011 and mid-2016. That is simply a staggering number when looking back on it, and what’s even more staggering is that the growth of JavaScript shows no signs of slowing down.

The iconic phrase “always bet on JavaScript” used by JavaScript’s creator, Brendan Eich, could never be more true than it is now. JavaScript is nearly everywhere today, powering dozens of different platforms, devices, and end uses. It runs on phones, drones, and automobiles and it tracks space suits at NASA while powering the text editor I’m using to write this.

Even more drastic than the growth in JavaScript adoption is the degree to which development of JavaScript has changed. In 2011 the first JS-to-JS compiler (or transpiler), Traceur, was released by Alex Russell at JSConf as “a tool that’s got an expiration date on it.” Traceur and other JavaScript tooling like npm, browserify, and webpack have made transpilation widely available and much more accessible than ever before. This coincided with the finalization of the ES6/ES2015 specification.

These factors combined to make way for the cornerstone of modern JavaScript development: that is, the idea of always and easily running a transpiler like babel against your JavaScript before execution in the browser and adopting ES201{5,6,7...} features in a rapid, piecemeal way.

Certainly “always” couldn’t exist without “

easily,” and getting to easily was an evolution. The adoption of npm as a workflow tool made managing JavaScript language tooling easier. Easier-to-use language tooling made the idea of always using a transpiler less abhorrent when it became absolutely necessary in frameworks with custom-syntax react and JSX.

This created an incredibly friendly environment for isomorphic JavaScript. Consider a scenario where a library doesn’t perfectly fit into the environment or semantics you are working with for your application. Before this ubiquitous toolchain that would have prohibited you from using the library in question, but now your transpilation and bundling toolchain usually makes using that library possible.

There are exciting things on the horizon as well. WebAssembly (or wasm) is a new portable, size- and load-time-efficient format suitable for compilation to the Web. It creates a viable compilation target for many languages, and more importantly, well established-projects in those languages. The promise of WebAssembly goes beyond isomorphic JavaScript to seemingly endless possibilities for isomorphic code in general.

On Nomenclature and Understanding

Lastly, I’d like to discuss a few questions that I often get asked by developers. The first question is: “Why make up a new term for something so seemingly obvious as running the same code on a client and a server?” The answer I give is simple: because there wasn’t a term for it yet. I also get asked, “Why base it on mathematics?” While I know my answer is contentious to some, it was obvious to me: because frontend build systems and, more recently, transpilers represent what I believe is an “isomorphism” in this sense of the word:

iso•mor•phic (adj.)

1)

a: being of identical or similar form, shape, or structure

b: having sporophytic and gametophytic generations alike in size and shape

2) related by an isomorphism

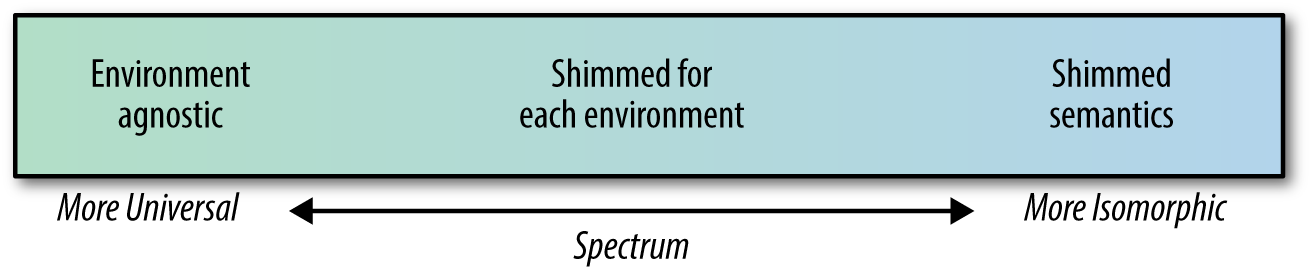

More recently, and much more frequently, I find myself asked about the debate between “isomorphic JavaScript” and “universal JavaScript.” Approaching this objectively, let’s again consider isomorphic JavaScript as a spectrum and the different categories of isomorphic JavaScript (Chapters 2 and 3). The spectrum illustrates the range in complexity when working with and building isomorphic JavaScript. The three categories of isomorphic JavaScript demonstrate the degree to which one must adapt JavaScript based on complexity and environment:

- JavaScript that is environment agnostic runs “universally” with no modifications.

- JavaScript that is shimmed for each environment only runs in different environments if the environment itself is modified.

- JavaScript that uses shimmed semantics may require modifications to the environment or behave slightly differently between environments.

If “universal JavaScript” is that which requires no modifications to the code or the environment to be isomorphic, then environment-agnostic JavaScript is clearly universal. Therefore, as more changes are needed to either the code itself or the environments in which it runs, the code ceases to be universal and is more isomorphic (Figure 16-1).

Figure 16-1. Universal and isomorphic JavaScript spectrum

When we consider the spectrum and categories together, the question “Is this isomorphic JavaScript or universal JavaScript?” becomes “Is this JavaScript more isomorphic or more universal?” This interpretation is vastly more technical and nuanced than my original definition for isomorphic JavaScript:

By isomorphic we mean that any given line of code (with notable exceptions) can execute both on the client and the server.

It also illustrates a key point: the debate about and interpretation of these terms is endless and largely unimportant. For example, to the horror of JavaScript developers everywhere, I could point out that an automorphism is “an isomorphism whose source and target coincide.” With this knowledge we could interpret “automorphic JavaScript” as another term for “universal JavaScript” since the code is identical in all environments. This new term would add no practical value to the shared understanding of the subject and only further cloud an otherwise simple (albeit nuanced) idea.

At this point you may be asking yourself, “Aren’t technical nuances important to us developers?” While there certainly is no shortage of technical nuance in software, a technical argument about a new or different term to use should not be your focus as a developer. Your focus should be on using whatever understanding you may have (right or wrong) to do something you find interesting or innovative. Our shared understanding of all things, including JavaScript, is constantly changing. All castles made of code will eventually be obsolete, and I for one am looking forward to watching them crash into the sea.