Chapter 9. Creating Common Abstractions

In this chapter we will create two abstractions that are frequently needed by isomorphic JavaScript applications:

-

Getting and setting cookies

-

Redirecting requests

These abstractions provide a consistent API across the client and server by encapsulating environment-specific implementation details. Throughout Part II there have been numerous warnings about the dangers of abstraction, (including Coplien’s abstraction is evil). Given these warnings, and the fact that this entire chapter is about creating abstractions, let’s take a moment to discuss when and why to abstract.

When and Why to Use Abstraction

Abstraction is not really evil, but rather frequently misused, prematurely obfuscating important details that provide context to code. These misguided abstractions are usually rooted in a valiant effort to make people’s lives better. For example, a module that sets up project scaffolding is useful, but not if it hides details in submodules that cannot be easily inspected, extended, configured, or modified. It is this misuse that is often perceived as evil, and all abstraction is then labeled evil by association. However, if properly applied, abstraction is an invaluable design tool for helping to create an intuitive interface.

In my experience, I have used abstraction to normalize APIs across environments in cases where the environmental differences would have burdened the users with implementation details beyond what they should be concerned with for the layer in which they are working. Or, as Captain Kirk would say, I abstract when “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” (or “the one”). That guiding principle may work well for running a starship, but that alone doesn’t make the decision to abstract correct. It is very difficult to know when to abstract. Typically I ask myself a few questions, such as:

-

Do I have enough domain knowledge and experience with the code to even make the decision?

-

Am I making too many assumptions?

-

Is there a more suitable tool than abstraction?

-

Will the benefits provided by abstraction outweigh the obfuscation costs?

-

Am I providing the right level of abstraction at the correct layer?

-

Would abstraction hide the intrinsic nature of the underlying object or function?

If your answers to these questions and similar ones indicate that abstraction is a good solution, then you are probably safe to proceed. However, I would still encourage you to discuss your ideas with a colleague. I cannot count the number of times where I have overlooked a crucial piece of information or alternative that makes abstraction not the best solution for a problem.

Now that we have cleared up the when and why of abstraction as much as possible, let’s proceed with creating some abstractions.

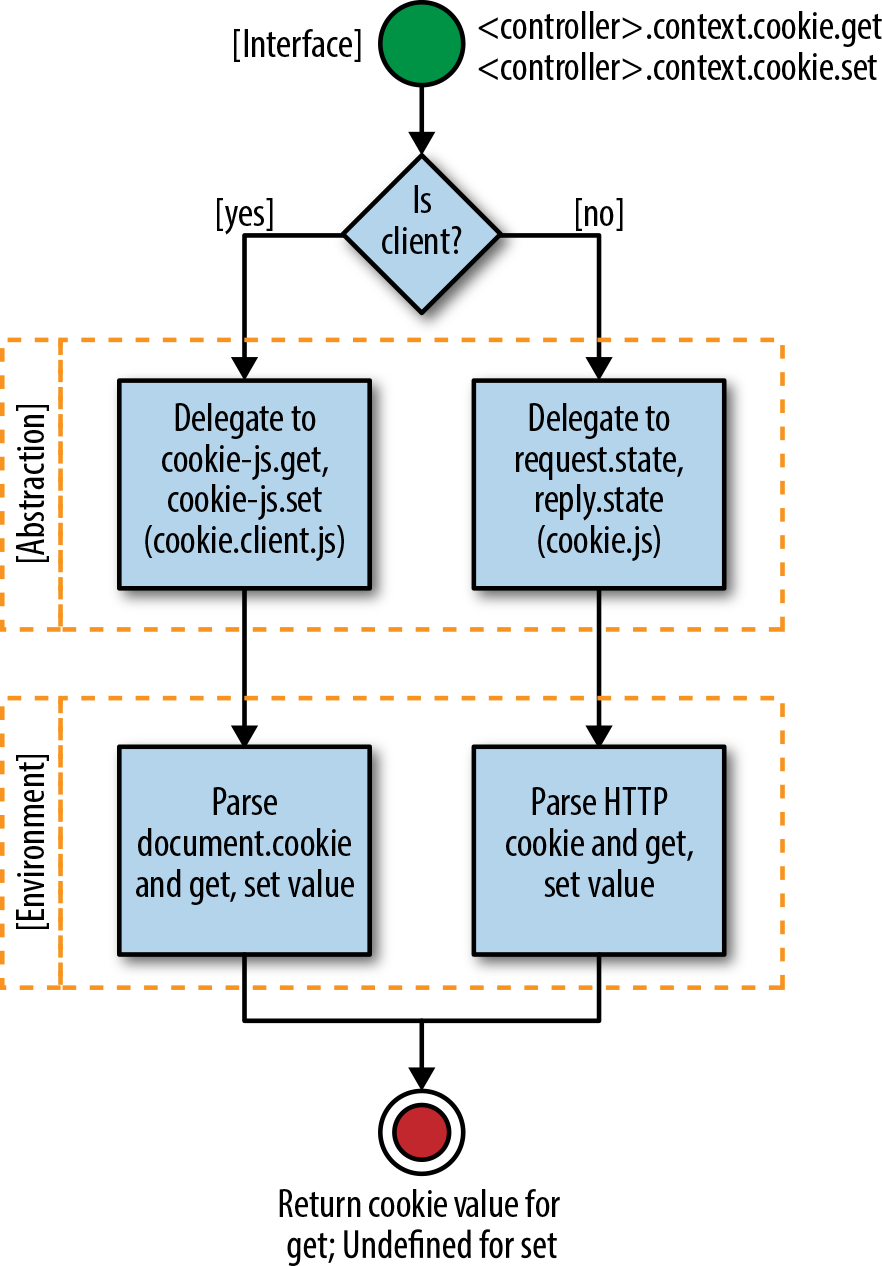

Getting and Setting Cookies

Cookies are plain-text values that were originally created to determine if two server requests had come from the same browser. Since then, they have served many purposes, including as a client-side data store. Cookies are sent as header values by the browser and the server. Both the browser and the server have the ability to get and set cookie values. As such, the ability to read and write cookies uniformly in an isomorphic JavaScript application is a common necessity, and this is a prime candidate for abstraction. The case for abstraction when reading and writing cookies is that the interface can differ greatly between the client and the server. Additionally, at the application level, intimate knowledge of the environment implementation details does not provide any value as one is either simply reading or writing a cookie. Creating a façade that abstracts these details does not obfuscate useful information from the application developer any more than the URL abstracts useful information—the inner workings of the Web—from a user.

Defining the API

A cookie is comprised of key/value pairs separated by equals signs, with optional attributes that are delimited by semicolons:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK Content-type: text/html Set-Cookie: bnwq=You can't consume much if you sit still and read books; Expires=Mon, 20 Apr 2015 16:20:00 GMT

The HTTP cookie in this example is sent as part of the request header to the server or received in the response header by the browser. This uniform exchange format allows the client and server to implement interfaces for getting and setting these values. Unfortunately, the interfaces are not consistent across environments. This is because on servers, unlike in browsers, there is not a standard interface. This is by design because server responsibilities are varied and they differ greatly from browsers, which are intended to be platforms for running (W3C) standards-based user interfaces. These differences are precisely why we are creating an abstraction. However, before we can create a common interface for getting and setting cookies across the client and the server we need to know the different environment interfaces—i.e., we need to gain the domain knowledge required to create a proper abstraction.

Getting and setting cookies on the client

document.cookie is the browser interface for getting and setting cookies. console.log(document.cookie) will log all cookies that are accessible by the current URL. The key/value pairs returned by document.cookie are delimited by semicolons:

Story=With Folded Hands;Novel=The Humanoids

This string of values isn’t of much use, but it can easily be transformed in an object with the cookie names as the keys, or we can implement a function to retrieve a cookie value by name as seen here:

functiongetCookieByName(name){letcookies=document.cookie.split(';')for(leti=0;i<cookies.length;i++){let[key,value]=cookies[i].split('=');if(key===name){returnvalue;}}}

The interface for setting a cookie is the same, except the righthand side of document.cookie is assigned a cookie value:

document.cookie="bnwq=A love of nature keeps no factories busy;path=/"

Getting and setting cookies on the server

As noted in “Defining the API”, server implementations for getting and setting cookies can differ. In Node cookies can be retrieved from the response header using the http module, as shown in Example 9-1.

Throughout the book we have been using hapi as our application server. Hapi has a more convenient interface, as illustrated in Example 9-2.

Setting a cookie in Node using the http module is fairly straightforward (Example 9-3).

Setting a cookie using hapi is equally easy (Example 9-4).

Creating an interface

Now that we have a better understanding of how cookies work on both the client and the server, we are ready to create a standard interface for getting and setting cookies. The interface (Example 9-5) will be the contract against which we code the environment-specific implementations.

The interface described in Example 9-5 needs to be accessible in route handler controller instances, so that application developers can make use of the API during the request/response lifecycle and after the controller is bound on the client. A good candidate that meets these requirements is the context object that is created when the controller is constructed:

constructor(context){this.context=context;}

Implementing the interface for the client

Now that we have defined the interface, we can code the client implementation. In “Getting and setting cookies on the client”, we saw some cookies were simple implementations to help illustrate the basics of working with the native browser API. In reality, getting and setting cookies requires a bit more work, such as encoding values properly.

Encoding Cookies

Technically cookies do not have to be encoded, other than semicolons, commas, and whitespace. But most implementations that you will see, especially on the client, URL-encode the values and names. The more important part is to encode and decode the values consistently across the client and the server, and to be careful not to double-encode values. These concerns are addressed in Example 9-6 and Example 9-7.

Fortunately, there are numerous libraries available that unobtrusively handle these details. In our application we will be using cookies-js, which we can install as follows:

$npminstallcookies-js--save

Now we can use cookies-js to code against the interface defined in Example 9-5. The client cookie implementation (./lib/cookie.client.js) is shown in Example 9-6.

Implementing the interface for the server

The server implementation (./lib/cookie.js), shown in Example 9-7, will simply wrap the hapi state interface.

Cookie example

Now we should be able to set and get cookies on both the client and the server, as shown in Example 9-10.

Figure 9-1 shows how our isomorphic cookie getter and setter works.

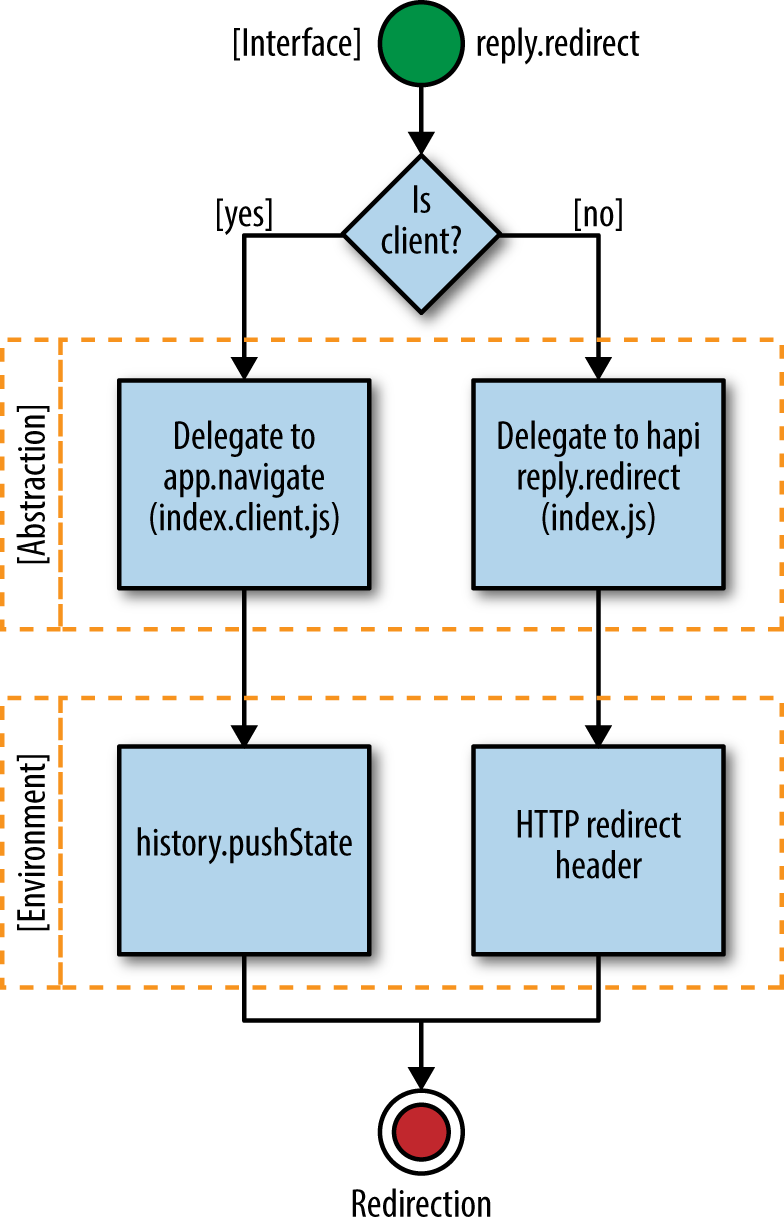

Redirecting a Request

Another common need across the client and the server is the ability to redirect user requests. Redirects allow a single resource to be accessible by different URLs. Some use cases for redirects are vanity URLs, application restructuring, authentication, managing user flows (e.g., checkout), etc. Historically only the server has handled redirects, by replying to the client with an HTTP redirect response:

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently Location: http://theoatmeal.com/ Content-Type: text/html Content-Length: 174

The client uses the location specified in the redirect response to make a new request, ensuring the user receives the actual resource he initially requested.

Another important piece of information in the redirect response is the HTTP status code. The status code is used by search engines, another type of client, to determine if a resource has been temporarily or permanently relocated. If it has been permanently relocated (status code 301), then all the ranking information associated with the previous page is transferred to the new location. Because of this, it is vital that redirects are handled correctly on the server.

Defining the API

In “Getting and Setting Cookies”, we learned that there is not a consistent way to set cookies on the server, but that there is a standard contract for sending the information over the Internet. The same is true of redirects on the server. The client does not have the concept of creating HTTP redirects, but it does have the ability to update the location (URL), which makes a new HTTP request. As with getting and setting cookies, the API is consistent across browsers. Again let’s follow best practices and better familiarize ourselves with the environments for which we will be creating an abstraction before we define an interface.

Redirecting on the client

window.location is the API for redirection on the client. There are a couple of different ways to update the location, as shown in Example 9-11.

Example 9-11. Redirecting on the client

window.location='http://theoatmeal.com/';// ORwindow.location.assign('http://theoatmeal.com/');

Redirecting on the server

In Node, the http module can be used to facilitate redirects (see Example 9-12).

Example 9-12. Redirecting on a Node server

importhttpfrom'http';http.createServer(function(request,response){response.writeHead(302,{'Location':'http://theoatmeal.com/','Content-Type':'text/plain'});response.end('Hello World\n');}).listen(8080);

In hapi redirects can be a bit less verbose (Example 9-13).

Example 9-13. Redirecting on the server using hapi

importHapifrom'hapi';constserver=newHapi.Server({debug:{request:['error']}server.route({method:'GET',path:{anything*},handler:(request,reply)=>{reply.redirect('http://theoatmeal.com/');}});});server.start();

Creating an interface

Redirection should be available during the request/response lifecycle, so that an application can redirect requests when necessary. In our case this is when the controller’s action method, index, is being executed. On the server we already have direct access to hapi’s redirect interface, reply.redirect. However, on the client we have a no-operation reply function, const reply = () ⇒ {};, so we need to add redirect functionality to this function. We have two options:

-

Create a façade for the hapi

replyobject for the server and do the same for the client. -

Add a redirect API with the same signature as hapi to the client

replystub.

If we go with option 1 we have the freedom to create an API of our choosing, but then we have to design the interface and create two implementations. Additionally, is it a good idea to wrap the entire hapi reply object just so we can define our own redirect interface? This isn’t a very good reason to create an abstraction of that magnitude. If we go with option 2 then we have to adhere to the hapi redirect interface, but we have less code to maintain and fewer abstractions. The less we abstract the better, especially early on, so let’s go with option 2.

Implementing the interface for the client

We will be using the hapi redirect interface as the guide for our client implementation. We will only be implementing the redirect function, as seen in Example 9-14. The other methods will be no-operations since they are used to set HTTP status codes, which are irrelevant on the client. However, we will still need to add these methods so that if one of the methods is called on the client it will not throw an error.

Example 9-14. Redirecting on the client implementation (./src/lib/reply.js)

exportdefaultfunction(application){constreply=function(){};reply.redirect=function(url){application.navigate(url);returnthis;};reply.temporary=function(){returnthis;},reply.rewritable=function(){returnthis;},reply.permanent=function(){returnthis;}returnreply;}

Including the client implementation

Now that we have defined the implementation, we need to include it in the request lifecycle. We can do this by adding the code in Example 9-15 to ./lib/index.client.js.

Example 9-15. Including the client redirect implementation in ./lib/index.client.js

// code omitted for brevityimportreplyFactoryfrom'./reply.client';// code omitted for brevityexportdefaultclassApplication{// code omitted for brevitynavigate(url,push=true){// code omitted for brevityconstrequest=()=>{};constreply=replyFactory(this);// code omitted for brevity}// code omitted for brevity}

Redirection example

In the examples thus far the entry point for the HelloController has been /hello/{name*}. This works great, but what if we want the users to see the greeting message when they access the application root, http://localhost:8000/? We could set up another route that points to this controller, but what if we only wanted to show this message the first time a user access the application? Our cookie and redirect APIs can handle this (see Example 9-16).

Example 9-16. HomeController class redirection example (./src/HomeController.js)

importControllerfrom'./lib/Controller';exportdefaultclassHomeControllerextendsController{index(application,request,reply,callback){if(!this.context.cookie.get('greeting')){this.context.cookie.set('greeting','1',{expires:1000*60*60*24*365});}returnreply.redirect('/hello');}toString(callback){callback(null,'I am the home page.');}}

Next we need to add our new controller to a route:

constapplication=newApplication({'/hello/{name*}':HelloController,'/':HomeController},options);

Finally, let’s add a new link to hello.html, so that we can navigate to/on the client:

<p>hello</p><ul><li><ahref="/hello/mortimer/smith"data-navigate>Mortimer Smith</a></li><li><ahref="/hello/bird/person"data-navigate>Bird Person</a></li><li><ahref="/hello/revolio/clockberg"data-navigate>Revolio Clockberg</a></li><li><ahref="/"data-navigate>Home Redirect</a></li></ul>

Now when we access http://localhost:8000/ on the client or the server it will redirect us to http://localhost:8000/hello. This approach provides us with the flexibility to implement different conditional redirects and to set the HTTP codes accordingly.

Figure 9-2 illustrates our isomorphic redirect abstraction.

Figure 9-2. Isomorphic redirect

Summary

In this chapter we created a couple of common abstractions—getting and setting cookies, and redirects—that are needed by most isomorphic JavaScript applications. We also learned when and why to use abstraction within the context of building isomorphic JavaScript apps. These examples and this knowledge will help us make more informed decisions in the future when we are deciding whether or not to use abstraction, and to use it properly if we have a case that calls for it.