Chapter 14. Brisket

Brisket is an isomorphic JavaScript framework built on top of Backbone.js. Brisket was developed by my team, the Consumer Web team at Bloomberg LP. It was published in Bloomberg’s organization on GitHub on October 2, 2014 under the Apache 2 open source license.

My team engineered Brisket with three guiding principles:

- Code freedom

- Consistent API across environments

- Stay out of the way of progress

Before diving deeper into Brisket, why did we build it?

The Problem

Like most frameworks, Brisket was born out of a product need. In late 2013, my team was tasked with relaunching Bloomberg.com’s opinion section as a new digital media product, BloombergView.com. The product team and designers had ambitious goals for the new site:

- Infinite scroll

- Pop-over lightboxed articles

- Responsive design (mobile first)

- Feels fast

- Great for SEO

We had 4 engineers and 3 months (12 weeks).

At the time, my team had only built traditional sites—server-side rendered pages with a mashup of client-side (in the browser) code to handle interactivity. A good example of a traditional website is IGN.com. We used Ruby on Rails for our server-side rendering, and a combination of jQuery, some Backbone.js, and vanilla JavaScript for our client-side code. We built only traditional sites because they are great for quickly rendering pages on the server and provide strong SEO.

Fast page rendering is critical to a digital media product’s success because media content is a fairly elastic product—if I can read the same thing somewhere else, but faster, that’s where I’ll go. Great SEO (a page that can be crawled and indexed by search engines) is also critical because search engines remain one of the highest drivers of traffic for digital media products.

Where traditional sites tend to come up short is when a site has a lot of client-side functionality. We anticipated the following problems with using the traditional site approach for the new site:

- Unable to share templates or business logic

-

The new site would require client-side rendering for features like infinite scroll and lightboxed articles. Since our server-side templates were written in Ruby, we could not reuse them on the client side. We would have to re-create them in JavaScript. Using two languages would also force us to maintain two sets of data models (a set for Ruby and a set for JavaScript) that did essentially the same thing.

- Bad encapsulation for features

-

With a traditional site, the server renders the markup for the feature, then the client-side code adds more functionality. It is more difficult to reason about the full lifecycle of a feature whose code is distributed across languages and (likely) folders in the filesystem.

- Perceived slow navigation between pages

-

Clicking to a new page in a traditional site often feels slow (even if it’s actually not). Between the browser making a round-trip to the server for a new page, rerendering everything on the page, and rerunning any client-side code, the transition from page to page seems slower than it may actually be.

A single-page application, where the server renders minimal markup and a client-side application renders content and handles interactions, seemed a better fit for the new site. A good example of an SPA in the wild is Pandora. SPAs are great at keeping all of the application code together, providing faster perceived page transitions, and building rich user interfaces. However, an SPA was not a panacea. Drawbacks included:

- Slow initial page load

Although SPAs feel fast while navigating within them, they usually have a slow initial page load. The slowness comes from downloading all of the application’s assets and then starting the application. Until the application has started, the user cannot read any content.

- No SEO

Since an SPA does not typically render markup on the server, it also does not produce any content for a search engine to crawl. In late 2013, search engines had begun attempting to crawl SPAs; however, that technology was too new (risky) for us to rely on.

Traditional sites and SPAs have complementary strengths; i.e., each one’s strengths address the other’s weaknesses. So the team asked, “How do we get all the goodness from both approaches?”

Best of Both Worlds

“Isomorphic JavaScript,” a term popularized by Spike Brehm’s article on Airbnb’s work on Rendr, describes JavaScript that can be shared between the client and the server. Rendr pioneered using the same code base to render pages through a Node.js server and handle client-side functionality with an SPA in the browser. Sharing a codebase this way is exactly what we wanted, but it came at the risk of potentially sacrificing our existing tools (i.e., Ruby, Rails, jQuery, etc.). Essentially, my team would be rebuilding all of our infrastructure. Before taking such a large risk, we explored a few options.

The first approach we considered was writing an SPA and using a headless browser to render pages on the server. But we ultimately decided that building two applications—an SPA and a headless browser server—was too complex and error-prone.

Next, the team explored the isomorphic frameworks that were available in late 2013. However, we didn’t find a lot of stable offerings; most of the isomorphic frameworks were still very young. Of the frameworks that we considered, Rendr was one of the few that were running in production. Because it seemed the least risky, we decided to try Rendr.

We were able to build a working prototype of BloombergView using Rendr, but we wanted more flexibility in the following areas:

- Templating

Rendr shipped with Handlebars templates by default; however, we preferred to use Mustache templates. Swapping Mustache for Handlebars did not seem like a straightforward task.

- File organization

Like Rails, in some cases Rendr preferred convention over configuration. In other words, an application would only work correctly if its files followed a specific folder structure. For this project, we wanted to use a domain-driven folder structure (i.e., article, home page, search folders) rather than functionality-driven (i.e., views, controllers, models). The idea was to keep all things related to the article together so they would be easy to find.

- Code style

Our biggest concern was how Rendr dictated our coding style for describing a page. As you can see in code in Example 14-1, Rendr controllers describe the data to fetch, but there’s not much flexibility. It wasn’t clear how to build a route if the data was a simple object rather than a model/collection. Also, since the controller did not have direct access to the View, we knew the View would be forced to handle responsibilities that we wanted to manage in our controllers.

Example 14-1. Rendr controller from 2013

var_=require('underscore');module.export={index:function(params,callback){varspec={collection:{collection:'Users',params:params}};this.app.fetch(spec,function(err,result){callback(err,result);});},show:function(params,callback){varspec={model:{model:'User',params:param},repos:{collection:'Repos',params:{user:params.login}}};this.app.fetch(spec,function(err,result){callback(err,result);});}}

After exploring other solutions, we decided to try building the site from scratch.

Early Brisket

Having spent 2 of our 12 weeks exploring options, we wanted to save time by building on top of one of the major client-side JS frameworks—Backbone, Angular, or Ember. All three had their merits, but we chose Backbone as our base because it was the easiest to get working on the server side.

Over the next 10 weeks we finished building the site. However, with such a tight timetable, there was no telling where the framework began and the application ended.

Making It Real

After a few months, my team was tasked with building a new application, BloombergPolitics.com, and rebuilding Bloomberg.com. The projects were to be built in two and three months respectively, without any downtime in between. With these tight timetables approaching, we took the opportunity to extract the tools from BloombergView into a real framework—Brisket. Here are some of the key tools we were able to extract:

Brisket.createServerA function that returns an Express engine that you can use in your application to run a Brisket application

Brisket.RouterBreweryBrews routers that know how to route on the server and the client

Brisket.Model,Brisket.CollectionEnvironment-agnostic implementations of the standard Backbone model and collection

Brisket.ViewOur version of a

Backbone.Viewthat allows support for some of the core features—reattaching Views, child View management, memory management, etc.Brisket.Templating.TemplateAdapterInherit from this to tell Brisket how to render templates

Brisket request/response objectsNormalized request/response objects that provide tools like cookies, an application-level referrer, setting response status, etc.

All of these tools were extracted and refactored with Brisket’s core principles—code freedom a consistent API across environments, and staying out of the way of progress—in mind.

Code Freedom

What we learned from Rendr is that using a complete isomorphic framework that includes modeling, routing, data fetching, and rendering is pretty difficult unless you reduce the scope of what developers can write. We knew Brisket could not provide the level of freedom that a regular Backbone application could, but we endeavored to get as close as possible.

The only requirement in a Brisket application is that you must return a View or a promise of a View from your route handlers. Everything else should feel as if you’re writing an idiomatic Backbone application. Brisket takes on the responsibility of placing your View in the page rather than each route handler placing the View. Similar to a route handler in the Spring framework, your route handlers’ job is to construct an object. Some other system in the framework is responsible for rendering that object.

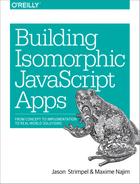

Think of a route handler as a black box (as represented in each of the following figures). On the initial request, when the user enters a URL in the browser, Express handles the request. Express forwards the request to your application (the Backbone rendering engine). The input to the black box is a request, and the output is a single View. The ServerRenderer, the receiver of the View, has several jobs:

- Serialize the View combined with the route’s layout.

- Send the result of all the data fetches (a.k.a. “bootstrapped data”) made during the current server-side request with the HTML payload.

- Render metatags.

- Render the page title.

- Set an HTML base tag that will make Brisket “application links” function correctly even without Brisket.

An application link is any anchor tag with a relative path. Application links are used to navigate to other routes in your application. All other types of links (e.g., absolute paths, fully qualified URLs, mailto links, etc.) function the same as in any other web page. By setting the base tag, you ensure that if JavaScript is disabled, or a user clicks an application link before the JavaScript has finished downloading, the browser will navigate to the expected path the old-fashioned way—a full page load of the new content. This way, the user can always access content. The initial page request process is illustrated in Figure 14-1.

Once the serialized View reaches the browser, your application picks up where it left off on the server. A good way to think about it is that the View reanimates with the same state that it had on the server. To reanimate the View, Brisket reruns the route that fired on the server. This time, though, rendering is handled by the ClientRenderer. The ClientRenderer knows which Views are already in the page and does not completely render them. Instead, as Views are initialized in the browser, if they already exist in the page, the ClientRenderer attaches them to the stringified versions of themselves.

Figure 14-1. Initial page request

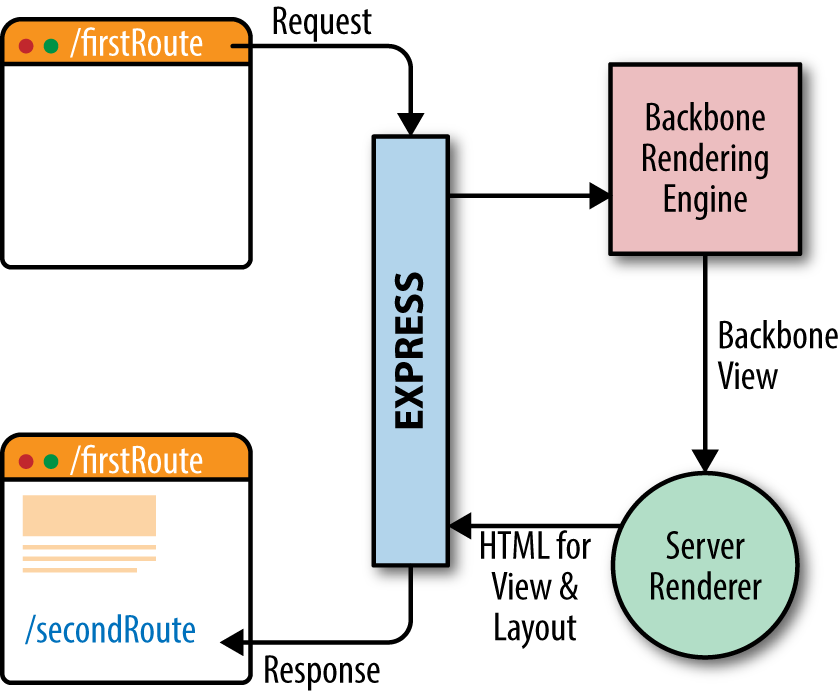

After the first route has completed, when the user clicks an application link, rather than heading all the way back to the server, the request is handled by the application in the browser. Your route handler works the same as it did on the server—it accepts a request, and returns a View. Your View is sent to the ClientRenderer, which updates the content in the layout. This is depicted in Figure 14-2.

Figure 14-2. Subsequent “page” requests

Since your route handler receives the same input and is expected to produce the same output, you can write it without thinking about what environment it will run in. You can manage your code however you like in a route handler. Example 14-2 shows an example of a Brisket route handler.

Example 14-2. Brisket route handler

constRouterBrewery=require('path/to/app/RouterBrewery');constExample=require('path/to/app/Example');constExampleView=require('path/to/app/ExampleView');constExampleRouter=RouterBrewery.create({routes:{'examples/:exampleId':'example'},example:function(exampleId,layout,request,response){if(!request.cookies.loggedIn){response.redirect('/loginpage');}request.onComplete(function(){layout.doSomething();});constexample=newExample({exampleId});example.fetch().then(()=>{constexampleView=newExampleView({example});exampleView.on('custom:event',console.log);returnexampleView;});}});

This handler primarily chooses the View to render but also uses event bubbling, makes decisions based on cookies, and does some work when the route is visible to the user (“complete”).

You may also notice that the objects required to construct the View must be entered in manually. Brisket opts for your configuration over our convention. You have the freedom to organize your application and create the conventions that make sense for you.

Use Any Templating Language

For our new applications, my team chose to use Hogan.js (a compiled flavor of Mustache). However, based on our work with Rendr, we wanted to keep the cost of switching templating engines as low as possible. By default, Brisket ships with a simple yet powerful (especially when used with ES6 template strings) StringTemplateAdapter, but, using inheritance, it can be overridden for either all your Views or a subset of them.

To switch templating engines for a View, inherit from Brisket.Templating.TemplateAdapter and implement templateToHtml to build a custom TemplateAdapter. Example 14-3 shows the implementation and usage of a simple Mustache template adapter.

Example 14-3. Simple Mustache template adapter

const MustacheTemplateAdapter = TemplateAdapter.extend({

templateToHTML(template, data, partials) {

return Mustache.render(template, data);

}

});

const MustacheView = Brisket.View.extend({

templateAdapter: MustacheTemplateAdapter

});

Changing a View’s templating engine requires just a few lines of code. Any Views that inherit from this View will use its templating engine too.

Consistent API Across Environments

By providing a consistent API that is predictable in any environment, Brisket helps developers spend time focusing on their application’s logic rather than on “what environment is my code running in?”

Model/Collection

Brisket provides environment-agnostic implementations of Backbone models and collections. From the developer’s perspective, modeling with Brisket is the same as modeling with Backbone. On the client side, models fetch data using jQuery. On the server side, models also use jQuery. The server-side version of jQuery’s Ajax transport is backed by the Node.js http package. Example 14-4 shows a sample Brisket model.

Example 14-4. Brisket model

const Side = Brisket.Model.extend({

idAttribute: 'type',

urlRoot: '/api/side',

parse: function(data) {

return data.side;

}

});

Brisket used jQuery as the client-side transport because Backbone uses jQuery for fetching data by default. In order to maintain a consistent API between both environments, Brisket also uses jQuery on the server side to fetch data. For the server side, my team would have preferred to use Node.js-specific tools like http or request, but it was more important to maintain a consistent API between both environments.

Currently, we are working on dropping jQuery as the transport so that fetching data can be simpler and more powerful. On the client side, we are exploring using the new Fetch API. On the server side, we want to switch to http or request.

View Lifecycle

In order to keep its Views environment agnostic, Brisket hijacks their render method. When View.render is called, Brisket executes a rendering workflow:

- Call the View’s

beforeRendercallback. - Merge the View’s model and any View logic specified by the View’s

logicfunction into a single data object. - Using the View’s template adapter, template, and the data from step 1, render the template into the View’s internal element.

- Call the View’s

afterRendercallback.

Use the beforeRender callback to set up data, queue up child views, and/or pick a template to use before Brisket renders the View’s template. beforeRender is called on both the client AND the server.

Use the afterRender callback to modify your View after Brisket has rendered the View’s template into the el. This is useful if you have to do some work (e.g., add a special class) that can only be done once the template has been rendered. afterRender is called on both the client and the server.

Brisket Views also have a callback called onDOM. Once the View enters the page’s DOM, use the onDOM callback to make changes to the View on the client side. The onDOM callback is a place where you can safely expect a window object to be available. So if you need to use a jQuery plugin that only works in a browser, for example, this is the place to do it. onDOM is called on the client but not the server.

During a View’s rendering workflow, you can expect that beforeRender will always be called before afterRender. On the client, onDOM will be called only after afterRender and when the View enters the page’s DOM.

Aside from these Brisket-specific methods, you can manipulate a Brisket View as you would a Backbone view. To facilitate this level of flexibility, we use jsdom for server-side rendering. Most other isomorphic frameworks have shied away from using it for rendering because it is relatively slow and heavyweight for rendering server-side content. We saw the same thing, but chose to use it because the flexibility to code how we wanted outweighed the performance hit. We hope to replace jsdom with a server-side rendering implementation that only parses into the DOM as needed.

Child View Management

In a standard Backbone application, child view management can be tricky. While it is straightforward to render one view inside another, it is not as straightforward to manage the relationship between the views. Memory management is another pain point. A common problem with Backbone applications is causing memory leaks by forgetting to clean up views that are no longer visible to the user. In a browser, where a user sees only a few pages, a memory leak may not be catastrophic, but in an isomorphic environment your client-side memory leak is also a server-side memory leak. A big enough leak will take down your servers (as we learned the hard way).

Brisket provides a child View management system that helps you manage memory and display child Views. Brisket’s child View handles all the bookkeeping for associating parent and child Views. It also makes sure to clean up Views as you navigate between routes, and the child View system comes with helpful methods to place a child View within the parent View’s markup. The child View system works the same way in all environments.

Tools That Do What You Expect in All Environments

Along the way, while working on multiple consumer-facing projects using Brisket, we encountered several problems that would have been straightforward to handle in either a traditional application or an SPA but were tricky in an isomorphic application. Here are a few features in Brisket that were derived from solving these problems:

- Redirecting to another URL

Brisket’s

responseobject provides aredirectmethod with the same signature as theresponseobject of an Express engine. It does what you would expect—redirects to the new URL you provide with an optional status code. That’s fine on the server, but in an isomorphic application, it’s possible to navigate to a route that callsresponse.redirectin the browser. What should that do? Should it do a push-state navigation to another route in the application? Should it do nothing? Ultimately, we decided that callingresponse.redirectshould trigger a full page load of the new page, like a redirect on the server would. Also, we made sure the new URL replaces the originally requested URL in the browser’s history usingwindow.location.replace.- Request referrer

In a traditional website, the request’s referrer is available via

request.referrerin an Express middleware or, on the client, in the browser’sdocument.referrerproperty. In an SPA,document.referreris correct on the initial page load, but not after you navigate to a new “page” within the application. We needed to solve this problem so that we could make accurate tracking calls for analytics. A normalized referrer is available via Brisket’srequest.referrerproperty.

Stay Out of the Way of Progress

Making Brisket extremely flexible has been critical to its high interoperability with third-party tools. We continue to look to the community for great solutions to common problems and do not want our framework to get in the way of that. By minimizing the rules around building a Brisket application, we’ve made sure there are ample places to integrate any third-party code even if it is not completely isomorphic.

ClientApp and ServerApp

My team started BloombergView with a strong knowledge base about jQuery plugins. After trying to use jQuery plugins, we quickly learned that they are not generally isomorphic-friendly—they only function correctly on the client side. Being able to use jQuery plugins and other client side-only code was the impetus for creating the ClientApp and ServerApp classes.

Brisket provides a base ClientApp and ServerApp that you can inherit from. Your implementations act as environment-specific initializers. These classes are a great place to set up environment-specific logging, initialize jQuery plugins, or enable/disable functionality depending on the environment.

Layout Template

Brisket provides a Layout class that inherits from Brisket.View. The layout’s template is where you define the <html>, <head>, and <body> tags of your pages. Brisket allows you to use different layouts for each router. Currently, using multiple layouts only works on the server side because of the complexity of swapping layouts in the browser. Since the layout template is just standard markup like any other template, it’s a good place to put third-party embedded code for common requirements such as ads, tracking pixels, etc.

Other Lessons Learned

Brisket has been great for my team. We have been able to hit (or just narrowly miss) our extremely tight deadlines and produce great digital products with it. Although these sites have been successful, we’ve learned a lot of lessons along the way. Here are a few:

- Avoid monolithic client-side bundles

A general problem for SPAs has always been large CSS and JS bundles. As applications grow and code bundles grow, the initial page load gets slower. We are working on new features in Brisket to make it easier to split up the application bundle.

- Prevent memory leaks

When writing an SPA, sometimes you forget your code runs on a server. Using singletons or not cleaning up event bindings can lead to memory leaks. Closing resources is a general good practice that many frontend developers did not have to pay attention to before the advent of SPAs. In SPAs and especially isomorphic applications, good coding practices must be followed.

- Building your own framework can be frustrating

Although it was exciting to build our own framework, with our tight deadlines it was frustrating when it was impossible to execute on a feature because Brisket did not have the tools yet. On the positive side, each moment of frustration led to a great new addition to (or subtraction from) Brisket.

What’s Next for Brisket?

My team currently uses Brisket in production on multiple consumer-facing products, including our flagship Bloomberg.com. We continue to evolve Brisket so that our users have a better experience and so that developing with it continues to be enjoyable and productive. Despite powering several large-scale sites in production, Brisket is still a sub-1.0.0 project. As of this writing, we are actively working toward a 1.0.0 release. Some of the new features/improvements we have in mind are:

- Make it easier to split up a large Brisket application into smaller bundles.

- Rearchitect server-side rendering for speed.

- Continue to simplify and refine the API.

- Decouple from jQuery.

- Future-proof for the arrival of generators, async functions, and template strings.

While Brisket has served us well so far, we continue to experiment with new technologies and approaches for building our products. Our team is not locked into any technology, even Brisket. We always want to use the best technology to solve our product needs, regardless of the source.

Postscript

Building Brisket has been quite a journey, full of ups and downs. To learn more about Brisket and keep up to date with the project, check us out on npm. Also try out the Brisket generator.