Chapter 10. Serializing, Deserializing, and Attaching

In Chapter 8 we added the ability to execute the request/reply lifecycle on the client. In Chapter 9 we created isomorphic abstractions for getting and setting cookies and redirecting user requests. These additions took our application framework from a server-only solution to a client-and-server solution. These were great strides toward a more complete solution, but we are still missing a key component of an isomorphic JavaScript application: the ability to seamlessly pick up on the client where things left off on the server.

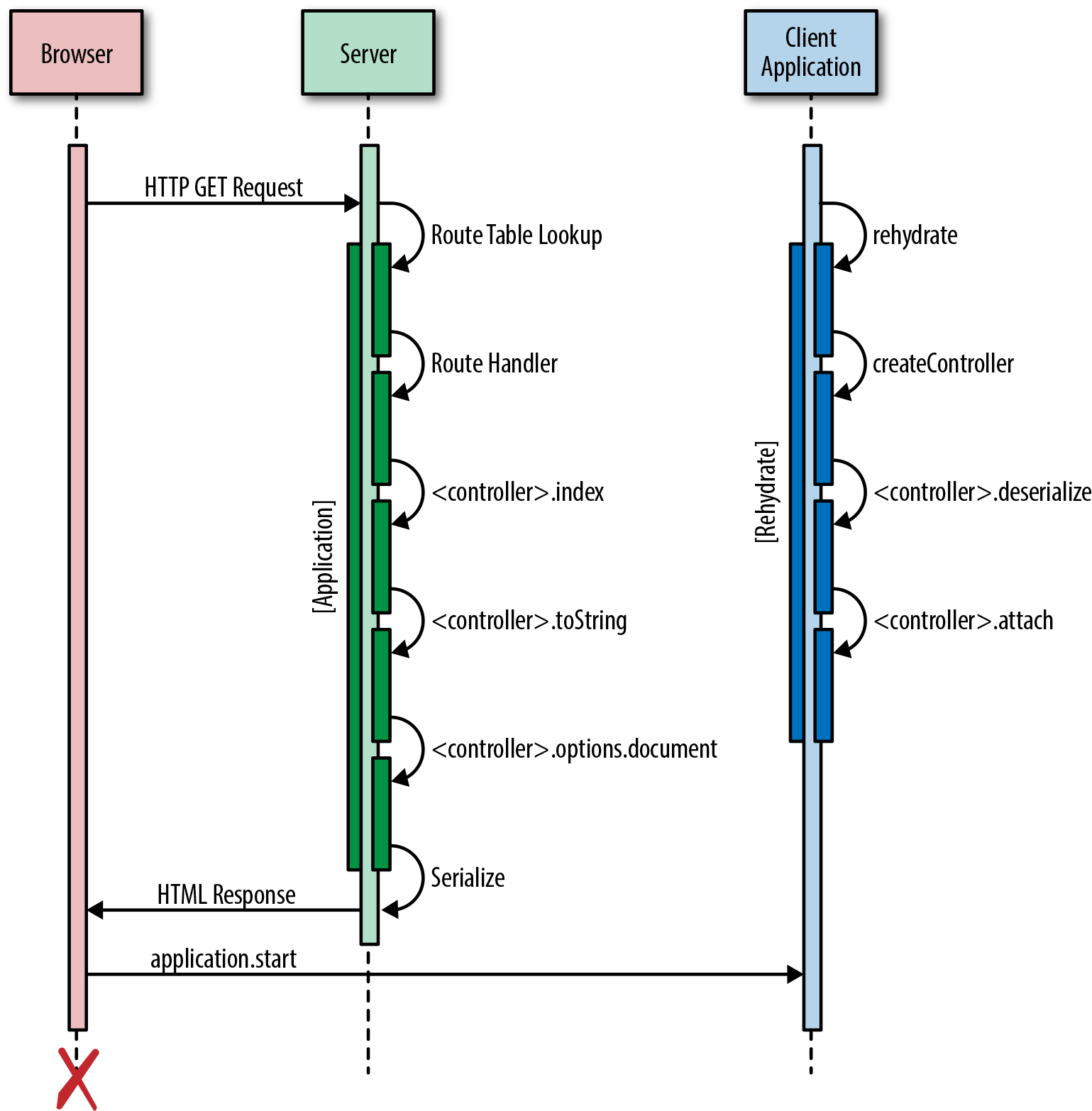

Essentially, the application should take the server-rendered markup and bind itself to the markup just as if it had been rendered on the client like an SPA. This means that any data used to render the controller response on the server should be available on the client, so that when a user starts interacting with an application she is able manipulate the data, e.g., via a form. Any DOM event handlers will need to be bound as well, to facilitate user interaction. In order to “rehydrate” on the client, four steps must be completed:

-

Serialize the data on the server.

-

Create an instance of the route handler controller on the client.

-

Deserialize the data on the client.

-

Attach any DOM event handlers on the client.

Defining Rehydration

You will see the term “rehydration” used throughout the rest of this chapter and in other isomorphic JavaScript references. Rehydration in the context of isomorphic JavaScript applications is the act of regenerating the state that was used to render the page response on the server. This could include instantiating controller and view objects, and creating an object or objects (e.g., models or POJOs) from the JSON that represents the data used to render the page. It could also include instantiating other objects, depending on your application architecture.

The remainder of this chapter will focus on implementing these processes in our application.

Serializing Data

So far in the examples in this book, we have used cookies, path and query parameters, and hardcoded defaults. In the real world, applications also rely on data from remote sources such as REST or GraphQL services. In JavaScript apps, this data is ultimately stored in a POJO, or plain old JavaScript object. The data is used in conjunction with HTML and DOM event handlers to create user interfaces. On the server only the HTML portion of the interface is created because the DOM bindings cannot be done until the server response has been received and processed by the client. The processing, rehydration, and DOM binding on the client often relies on this state data from the server. Additionally, user interactions that trigger events after the rehydration and binding typically need access to this data to modify it or make decisions. Therefore, it’s important that the data be accessible by the client during rehydration and afterward. Unfortunately, the POJO cannot be sent across the network as part of an HTTP request. The POJO needs to be serialized to a string that can be passed to the template, parsed by the client, and assigned to a global variable.

The serialization is accomplished using JSON.stringify, which creates a string representation of the POJO. This is the standard method for serializing a POJO, but we still need to add a method to our Controller class from Example 7-3 that can be executed on the server and that returns this stringified POJO:

serialize(){returnJSON.stringify(this.context.data||{});}

For our application the default implementation is serializing the this.context.data property from ./src/lib/controller.js. However, this default behavior could be easily overridden to handle different use cases. Sometimes there are APIs for setting and getting data in a POJO, such as Backbone models or Redux stores (store.getState). For these and other client data stores the serialize function can be easily overridden to implement custom behavior for serializing these objects.

Note

The data that is being serialized by the Controller class’s serialize method will typically be sourced from a remote location, as noted earlier. This data is usually resolved using HTTP as the transport mechanism. This is done on the client using Ajax and on the server using Node’s http module. This data fetching requires client-specific implementations. Fortunately, we are not the first developers to need an isomorphic HTTP client. There are many, but a few popular ones are isomorphic-fetch and superagent.

Next we need to update the document function from Example 8-15 (./src/options.js) to call the new serialize function, as seen in Example 10-1.

Example 10-1. Server options call to Controller class serialize method

exportdefault{nunjucks:'./dist',server:server,document:function(application,controller,request,reply,body,callback){nunjucks.render('./index.html',{body:body,application:APP_FILE_PATH,state:controller.serialize(),},(err,html)=>{if(err){returncallback(err,null);}callback(null,html);});}};

Finally, we create a global variable in our template (./src/index.html) that can be accessed during rehydration on the client:

<scripttype="text/javascript">window.__STATE__='{{state}}';</script>

Warning

Make sure to add this <script> tag before the <script> tag that includes the application source.

Creating a Controller Instance

The next step in the rehydration process is to create a controller instance on the client for the current route. This instance will be assigned the serialized data and bound to the DOM, which will enable the user to interact with the HTML interface returned by the server. Fortunately, we have already written the code to look up a Controller class using the router and create a controller instance. We just need to reorganize the code a bit so that we can reuse it.

In the navigate function we created in Example 8-4 we used the URL to look up the Controller class in the application route table. If one was found, we then created a controller instance. This code can be moved to a new function in the Application class (./src/lib/index.client.js) that can be called by the navigate function, defined in Example 10-2.

Example 10-2. Client Application class createController method

createController(url){// split the path and search stringleturlParts=url.split('?');// destructure URL parts arraylet[path,search]=urlParts;// see if URL path matches route in routerletmatch=this.router.route('get',path);// destructure the route path and paramslet{route,params}=match;// look up Controller class in routes tableletController=this.routes[route];returnController?newController({// parse search string into objectquery:query.parse(search),params:params,cookie:cookie}):undefined;}

Now we can use the createController function in the navigate function and a function that we are about to create, rehydrate (Example 10-3).

The rehydrate function can then be called by the start function (Example 10-4).

Example 10-4. Client Application class start method

start(){// PREVIOUS CODE OMITTED FOR BREVITY// the rehydrate call has been added to the bottom// of the function bodythis.rehydrate();}

Idempotence and Rehydration

In our application examples controller construction is simple. However, in some cases the construction or initialization logic could be more complex. In those cases it is important that the component initialization logic be idempotent. This is a fancy way of saying that no matter how many times a function is executed, the result should be the same. If you are relying on closures, counters, and so on in your initialization and the initialization logic is not idempotent, then the rehydration process could produce errors. For example, if there is an application singleton that has state, any component initialization logic that relies on that state will differ on the client if the state is not transferred to the client and added to the singleton on the client before rehydration begins.

Deserializing Data

In the previous section we created an instance of the controller during the application rehydrate process on the client. Now we need to transfer the state that was created on the server and serialized as part of the server page response to the controller instance on the client. This is necessary because routes can have different states, and the application will depend upon these states. For instance, if the route rendered on the server has any sort of interface for interacting with or manipulating data, such as an “add to cart” button, a form, a graph with a range selector, etc., then the user will likely need that data to interact with the page, rerender the page, or persist a change.

In “Serializing Data” we included the state data in the page response, so now all we have to do is implement a deserialize method on the base controller (./src/lib/controller.js):

deserialize(){this.context.data=JSON.parse(window.__STATE__);}

Global Variables

Relying on a global variable is typically bad practice because of potential name collisions and maintenance issues. However, there isn’t a real alternative. You could pass the data into a function, but then you would expose a function as a global in some fashion.

This method can now be used as part of the rehydration process to assign the data to the controller instance. We can add data rehydration to the client Application class’s rehydrate method (in ./src/lib/index.client.js) as follows:

rehydrate(){this.controller=this.createController(this.getUrl());this.controller.deserialize();}

Attaching DOM Event Handlers

The last part of the rehydration process is attaching event handlers to the DOM. In its simplest form, event binding is done by calling the native method, addEventListener, as shown here:

document.querySelector('body').addEventListener('click',function(e){console.log(e);},false);

Some libraries set the context for the event listener functions to the view or controller object that created the listener. Some libraries, like Backbone, have an interface for defining event listeners. These event listeners are bound to the containing view element using event delegation to reduce overhead in the browser. In our case we are just going to add an empty method, attach, to the controller that is called during the rehydration process. It will be up to the application developer to implement the method details:

attach(el){// to be implemented by the application}

In addition to the rehydration process, the attach method should be called as part of the client-side route response lifecycle. This ensures that a route handler will be bound to the DOM regardless of whether it was executed on the client or the server. Example 10-5 shows how we add DOM binding to the client Application class’s rehydrate method.

Example 10-5. Adding DOM binding to the rehydrate method

rehydrate(){lettargetEl=document.querySelector(this.options.target);this.controller=this.createController(this.getUrl());this.controller.deserialize();this.controller.attach(targetEl);}

These two calls to the attach method ensure that a route handler is always bound to the DOM. However, there is a bit of an issue with this code—there is not a yin for our yang. If we continually attach handlers to the DOM without detaching a previous handler, we could end up with a memory leak. Adding a detach method to the base controller and calling it as part of the client-side route handler lifecycle, as shown in Example 10-6, can help prevent this problem. detach will be an empty method like attach, leaving the implementation details up to the application developer:

detach(el){// to be implemented by the application}

Verifying the Rehydration Process

Now that we have the core pieces in place that enable an application to recall state and attach itself to the DOM, we should be able to rehydrate our app. To test recalling state, first let’s generate a random number in the index method of the HelloController class (Example 7-7) and store it as a property in this.context.data:

index(application,request,reply,callback){this.context.cookie.set('random','_'+(Math.floor(Math.random()*1000)+1),{path:'/'});this.context.data={random:Math.floor(Math.random()*1000)+1};callback(null);}

Next, we need to add this.context.data to the rendering context for the toString method in HelloController:

toString(callback){// this can be handled more eloquently using Object.assign// but we are not including the polyfill dependency// for the sake of simplicityletcontext=getName(this.context);context.data=this.context.data;nunjucks.render('hello.html',context,(err,html)=>{if(err){returncallback(err,null);}callback(null,html);});}

We can now render this random number in the hello.html template:

<p>hello{{fname}}{{lname}}</p><p>Random Number in Context:{{data.random}}</p><ul><li><ahref="/hello/mortimer/smith"data-navigate>Mortimer Smith</a></li><li><ahref="/hello/bird/person"data-navigate>Bird Person</a></li><li><ahref="/hello/revolio/clockberg"data-navigate>Revolio Clockberg</a></li><li><ahref="/"data-navigate>Home Redirect</a></li></ul>

Next, we can log this.context.data in our attach method and compare the values:

attach(el){console.log(this.context.data.random);}

We can also add a click listener in our attach method to verify that the correct target is being passed to this method and that an event listener can be bound to it:

attach(el){console.log(this.context.data.random);el.addEventListener('click',function(e){console.log(e.currentTarget);},false);}

Next, we need to ensure that we clean up the event handler we added in our attach method. If we don’t do this, then we will have an event handler for each navigation to the /hello/{name*} route. First we need to move the event listener function from the attach method to a named function, so that we can pass a reference to the function when we remove it. At the top of the HelloController class, let’s create a function expression:

functiononClick(e){console.log(e.currentTarget);}

Now we can update our attach method and add a detach method:

attach(el){console.log(this.context.data.random);this.clickHandler=el.addEventListener('click',onClick,false);}detach(el){el.removeEventListener('click',onClick,false);}

If you reload the page and click anywhere, you should see the body element in the console. If you navigate, clear the console, and click again, you should only see one log statement because our detach method removed the event listener from the previous route.

Figure 10-1 shows a high-level overview of what we’re aiming for.

Figure 10-1. Client rehydration

Summary

We learned a lot in this chapter. Here’s a quick recap of what we walked through:

-

Serializing the route data in the server page response

-

Creating an instance of the route handler on the client

-

Deserializing the data

-

Attaching the route handler to the DOM

These rehydration steps ensure that an application functions the same for a user regardless of whether the route was rendered on the client or the server, with the added performance benefit of not refetching the data.