Chapter 15. “Colony” Case Study: Isomorphic Apps Without Node

Colony is a global film-streaming platform connecting content owners with passionate fans through exclusive extra content. In a landscape of significant competition, our go-to-market strategy relies heavily on a world-class product and user experience, with ambitions to redefine the way film is consumed online.

The Problem

An important differentiation between Colony’s video-on-demand model and that of competitors like Netflix is our transactional business model: content on our platform is open to the public to browse and purchase on a pay-as-you-go basis, and isn’t hidden behind a subscription paywall. We benefit from letting Google crawl and index our entire catalogue as a result. On top of this, the nature of our product requires a dynamic user interface that must frequently update to reflect changes to a complex application state. For example, elements must update to reflect whether the user is signed in or not, and whether the content bundle (or parts of it) is owned or at a certain point in its rental period. While our initial prototype was built using out-of-the-box ASP.NET MVC, we soon realized that turning our frontend into a single-page app would vastly improve our ability to deal with these challenges, while also enabling our backend and frontend teams to work independently of one another by “decoupling” the stack.

We were therefore faced with the dilemma of how to combine a traditional server-rendered and indexable website with a single-page app. At the time in 2014, isomorphic frameworks like Meteor provided this sort of functionality out of the box but required a Node.js backend. SPA frameworks like Angular and Ember also were already ubiquitous, but they came hand-in-hand with SEO drawbacks that we wanted to avoid.

Our backend had already been built in ASP.NET MVC, and two-thirds of our development team was made up of C# developers. We wondered if there was a way we could achieve something similar to an isomorphic application, but without a Node.js backend and without having to rebuild our entire application from scratch. How could C# and JavaScript—technologies that are typically viewed as separate and incompatible—be brought together? In other words, could we build an isomorphic application without Node.js?

Solving this problem would also provide us with numerous performance benefits and the ability to instantly render the application in very specific states—for example, linking to a film page with its trailer open, or rendering the checkout journey at a specific point. As most of this UI takes place within “modals” in our design, these are things that would traditionally be rendered by JavaScript and could be managed only in the frontend.

We wanted the ability to server render any page or view in any particular state based on its URL, and then have a client-side JavaScript application start up in the background to take over the rendering and routing from that point on. For this to happen we would firstly need a common templating language and shared templates. Secondly, we would need a common data structure for expressing the application state.

Up until this point, view models had been the responsibility of the backend team, but with an ideal decoupled stack, all view design and templating would be the responsibility of the frontend team, including the structure and naming of the data delivered to the templates.

From the perspective of removing any potential duplication of effort or code, we pondered the following questions:

-

Was there a templating language with implementations in both C# and JavaScript? For this to be conceivable, it would need to be “logicless,” and therefore not allow any application code in the templates in the way that C# Razor or PHP does.

-

If a component was needed by both the frontend and the backend, could it be expressed in a language-agnostic data format such as JSON?

-

Could we write something (for instance, a view model) in one language and automatically transpile it to another?

Templating

We began by looking at templating. We were big fans of Handlebars, due to its strict logicless nature and its intentionally limited scope. Given a template, and a data object of any structure, Handlebars will output a rendered string. As it is not a full-blown view engine, it can be used to render small snippets, or integrated into larger frameworks to render an entire application. Its logicless philosophy restricts template logic to #if, #unless, and #each, the idea being that if anything more complex is needed, the template is not the place for it.

Although originally written for JavaScript, Handlebars can be used with any language for which an implementation exists, and as a result, implementations now exist for almost every popular server-side programming language. Thankfully for us, a well-maintained open source implementation for C# existed in the form of the excellent Handlebars.Net.

Our frontend had been built with a modular or “atomic” design philosophy, meaning that rather than using monolithic page templates, any particular view was made up from a sequence of reusable “modules” that could in theory function in any order or context. With our previous server-side view rendering solution in Razor, this concept didn’t translate well from the frontend to the backend, as our backend team would need to take the static modules, stitch them together into larger constructs, and insert the necessary logic and template tags as desired. With a shared templating language and data structure, however, there was no reason why we couldn’t now share these individual modules between both sides of the stack and render them in the desired order using either C# or JavaScript, with identical results. The process of designing a module, templating it, and making it dynamic could then be done entirely by the frontend team.

Data

One issue with our previous solution was the ad hoc nature of the view models in our prototype, which evolved organically per template as features were added. There was never a big picture of the overall application data structure, with data often being exposed to some templates and not others, requiring effort and care from both teams when creating new templates.

To avoid this problem early on, we designed a “global” data structure for the whole application that could represent the site, a resource, and the application state in a single object. On the backend, this structured data would be mapped from the database and delivered to Handlebars to render a view. On the frontend, the data would first be received over a REST API and then delivered to Handlebars. In each case, however, the final data provided to Handlebars would be identical.

The data structure we decided on was as follows. This object can be thought of as a state container for the entire application at any point in time:

{Site:{...},Entry:{...},User:{...},ViewState:{...},Module:{...}}

The Site object holds data pertaining to the entire website or application, irrespective of the resource that’s being viewed. Things like static text, Google Analytics ID, and any feature and environment toggles are contained here.

The Entry object holds data pertaining to the current resource being viewed (e.g., a page or a particular film). As a user navigates around the site, the requested resource’s data is pulled in from a specific endpoint, and the entry property is updated as needed:

<head>...<title>|</title></head>

The User object holds nonsensitive data pertaining to the signed-in user, such as name, avatar, and email address:

<asideclass="user-sidebar"><h3>Hello !</h4><h4>Your Recent Purchases</h4>...</aside>

The ViewState object is used to reflect the current rendered state of a view, which is crucial to our ability to render complex states on the backend via a URL. For example, a single view can be rendered with a particular tab selected, a modal open, or an accordion expanded, as long as that state has its own URL:

<navclass="bundle-nav"><ahref="/extras/"class="tab tab__active">Extras</a><ahref="/about/"class="tab tab__active">About</a></nav>

The Module object is not global, but is used when data must be delivered to a specific module without exposing it to other modules. For example, we may need to iterate through a list of items within an entry (say, a gallery of images), rendering an image module for each one, but with different data. Rather than that module having to pull its data out of the entry using its index as a key, the necessary data can be delivered directly to it via the Module object:

<figureclass="image"><imgsrc=""alt=""/><figcaption><p></p></figcaption></figure>

Transpiled View Models

With our top-level data structure defined, the internal structure of each of these objects now needed to be defined. With C# being the strictly typed language that it is, arbitrarily passing dynamic object literals around in the typically loose JavaScript style would not cut it. Each view model would need strictly defined properties with their respective types. As we wanted to keep view model design the responsibility of the frontend, we decided that these should be written in JavaScript. This would also allow frontend team members to easily test the rendering of templates (for example, using a simple Express development app) without needing to integrate them with the .NET backend.

JavaScript constructor functions could be used to define the structure of a class-like object, with default values used to infer type.

Here’s an example of a typical JavaScript view model in our application describing a Bundle and inheriting from another model called Product:

varBundle=function(){Product.apply(this);this.Title='';this.Director='';this.Synopsis='';this.Artwork=newImage();this.Trailer=newVideo();this.Film=newVideo();this.Extras=[newExtra()];this.IsNew=false;};

Templates often require the checking of multiple pieces of data before showing or hiding a particular element. To keep templates clean, however, #if statements in Handlebars may only evaluate a single property, and comparisons are not allowed without custom helper functions, which in our case would have to be duplicated. While more complex logic can be achieved by nesting logical statements, this creates unreadable and unmaintainable templates, and is against the philosophy of logicless templating. We needed to decide where the additional logic needed in these situations would live.

Thanks to the addition of “getters” in ES5 JavaScript, we were able to easily add dynamically evaluated properties to our constructors that could be used in our templates, which proved to be the perfect place to perform more complex evaluations and comparisons.

The following is an example of a dynamic ES5 getter property on a view model, evaluating two other properties from the same model:

varBundle=function(){...this.Trailer=newVideo();this.IsNew=false;...Object.defineProperty(this,'HasWatchTrailerBadge',{get:function(){returnthis.IsNew&&this.Trailer!==null;}});};

We now had all of our view models defined with typed properties and getters, but the problem remained that they existed only in JavaScript. Our first approach was to manually rewrite each of them in C#, but we soon realized that this was a duplication of effort and was not scalable. We felt like we could automate this process if only we had the right tools. Could we somehow “transpile” our JavaScript constructors into C# classes?

We decided to try our hand at creating a simple Node.js app to do just this. Using enumeration, type checking, and prototypal inheritance we were able to create descriptive “manifests” for each of our constructors. These manifests contained information such as the name of the class and what classes, if any, it inherited from. At the property level, they contained the names and types of all properties, whether or not they were getters, and if so, what the getter should evaluate and what type it should return.

With each view model parsed into a manifest, the data could now be fed into (ironically) a Handlebars template of a C# class, resulting in a collection of production-ready .cs files for the backend, each describing a specific view model.

Here’s the same Bundle view model, transpiled into C#:

namespaceColony.Website.Models{publicclassBundle:Product{publicstringTitle{get;set;}publicstringDirector{get;set;}publicstringSynopsis{get;set;}publicImageArtwork{get;set}publicVideoTrailer{get;set;}publicVideoFilm{get;set;}publicList<Extra>Extras{get;set;}publicBooleanIsNew{get;set;}publicboolHasWatchTrailerBadge{get{returnthis.IsNew&&this.Trailer!=null;}}}}

It’s worth noting that our transpiler is limited in its functionality—it simply converts a JavaScript constructor into a C# class. It cannot for example, take any piece of arbitrary JavaScript and convert it to the equivalent C#, which would be an infinitely more complex task.

Layouts

We now needed a way of defining which modules should be rendered for a particular view, and in what order.

If this became the responsibility of our view controllers, this list of modules and any accompanying logic would need to be duplicated in both C# and JavaScript. To avoid this duplication, we wondered if we could express each view as a JSON file (like the following simple example describing a possible layout of a home page) that again could be shared between the frontend and backend:

["Head","Header","Welcome","FilmCollection","SignUpCta","Footer","Foot"]

While listing the names of modules in a particular order was simple, we wanted the ability to conditionally render modules only when specific conditions were met. For example, a user sidebar should only be rendered if a user is signed in.

Taking inspiration from Handlebars’s limited set of available logic (#if, #unless, #each), we realized we could express everything we needed to in JSON by referring to properties within the aforementioned global data structure:

[...{"Name":"UserSidebar","If":["User.IsSignedIn"]},{"Name":"Modal","If":["ViewState.IsTrailerOpen"],"Import":"Entry.Trailer"}]

Having restructured the format of the layout, we now had the ability to express simple logic and import arbitrary data into modules. Note that If statements take the form of arrays to allow the evaluation of multiple properties.

Taking things further, we began to use this format to describe more complex view structures where modules could be nested within other modules:

[...{"Name":"TabsNav","Unless":["Entry.UserAccess.IsLocked"]},{"Name":"TabContainer","Unless":["Entry.UserAccess.IsLocked"]"Modules":[{"Name":"ExploreTab","If":["ViewState.IsExploreTabActive"],"Modules":[{"Name":"Extra","ForEach":"Entry.Extras"}]},{"Name":"AboutTab","If":["ViewState.IsAboutTabActive"]}]}...]

The ability to express the nesting of modules allowed for complete freedom in the structuring of markup.

We had now arrived at a powerful format for describing the layout and structure of our views, with a considerable amount of logic available. Had this logic been written in either JavaScript or C#, it would have required tedious and error-prone manual duplication.

Page Maker

To arrive at our final rendered HTML on either side of the stack, we now needed to take our templates, layouts, and data and combine them all together to produce a view.

This was a piece of functionality that we all agreed would need to be duplicated, and would need to exist in both a C# and a JavaScript form. We designed a specification for a class that we called the “Page Maker,” which would need to iterate through a given layout file, render out each module with its respective data as per the conditions in the layout file, and finally return a rendered HTML string.

As we needed to pay close attention to making sure that both implementations would return identical output, we wrote both the C# and JavaScript Page Makers as group programming exercises involving the whole development team, which also provided a great learning opportunity for frontend and backend team members to learn about each other’s technology.

Frontend Single-Page App

Our development team culture had always been to build as much as we could in-house, and own our technology as a result. When it came to our single-page app, we had the choice of using an off-the-shelf framework like Angular, Backbone, or Ember, or building our own. With our templating taken care of, and our global data structure over the API effectively forming our application state, we still needed a few more components to manage routing, data binding, and user interfaces. We strongly believed, and still do, in the concept of “unobtrusive” JavaScript, so the blurring of HTML and JavaScript in Angular (and now React’s JSX) was something we wanted to avoid. We also realized that trying to retrofit an opinionated framework onto our now quite unique architecture would result in significant hacking and a fair amount of redundancy in the framework. We therefore decided to build our own solution, with a few distinct principles in mind: firstly, UI behavior should not be tightly coupled to specific markup, and secondly, the combination of changes to the application state and the Handlebars logic already defined in our templates and layouts should be enough to enable dynamic rerendering of any element on the page at any time.

The solution we arrived at is not only extremely lightweight, but also extremely modular. At the lowest level we have our state and fully rendered views delivered from the server, where we can denote arbitrary pieces of markup to “subscribe” to changes in the state. These changes are signaled using DOM events, which we found to be much more performant than an Angular-like digest loop, or various experimental “Observable” implementations. When a change happens, that section of the DOM is rerendered and replaced. We were reassured to learn recently that the basic concept behind this is almost identical to that of the increasingly popular Redux library.

A level up, our user interface “behaviors” are entirely separate from this process, effectively progressively enhancing arbitrary pieces of markup. For example, we could apply the same “slider” UI behavior to a variety of different components, each with entirely different markup—in one case a list of films, in another case a list of press quotes.

At the highest level, a History API–enabled router was built to intercept all link clicks and determine which layout file was needed to render the resulting view. With the data forming our application state already delivered over a REST API from the server, we decided to expand this API to also deliver module templates and JSON layouts. This would ensure that these various shared resources could only ever exist in one place (the server), and thus reduce the risk of any divergence between the frontend and backend resources.

Final Architecture

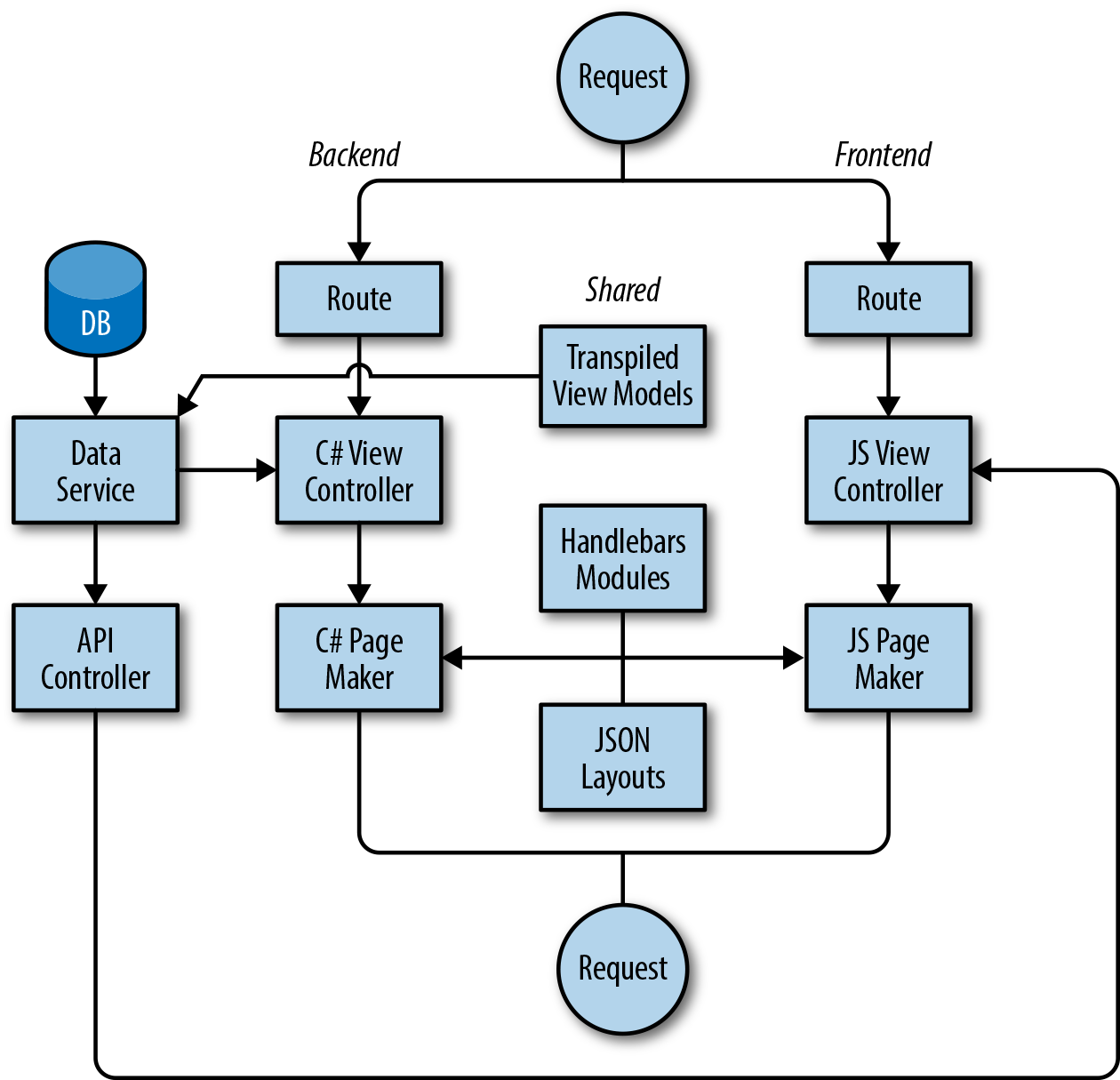

The schematic in Figure 15-1 illustrates the full lifecycle of both the initial server-side request and all subsequent client-side requests, with the components used for each.

Figure 15-1. Lifecycle of initial server-side request and subsequent client-side requests

Next Steps

While sharing these various components heavily reduced code duplication in our application, there are areas where duplication still exists, such as our controllers and routes. Building upon what we learned from our layout files, however, there’s no reason why our routes and parts of their respective controllers couldn’t also be expressed as shared JSON files, and then fed into lightweight parsers with implementations in C# and JavaScript.

While several solutions have now started to arise allowing the rendering of Angular applications and React components on non-JavaScript engines (such as ReactJS.NET and React-PHP-V8JS), our solution is still unique in the ASP.NET ecosystem due to its lack of dependency on a particular framework. While our backend team did have to write some additional code (such as the Page Maker) during the development of the solution, their data services, controllers, and application logic were left more or less untouched. The amount of frontend UI code they were able to remove from the backend as a result of decoupling has led to a leaner backend application with a clearer purpose. While our application is in one sense “isomorphic,” it is also cleanly divided, with a clear separation of concerns.

We imagine that there are many other development teams out there that, like us, desire the benefits of an isomorphic application but feel restrained by their choice of backend technology—whether that be C#, Java, Ruby, or PHP. In these cases, decisions made during the infancy of a company are now most likely deeply ingrained in the product architecture, and have influenced the structure of the development team. Our solution shows that isomorphic principles can be applied to any stack, without having to introduce a dependency on a frontend framework that may be obsolete in a year’s time, and without having to rebuild an application from scratch. We hope other teams take inspiration from the lessons we’ve learned, and we look forward to seeing isomorphic applications across a range of technologies in the future.