Chapter 3. Different Categories of Isomorphic JavaScript

Charlie Robbins is commonly credited for coining the term “isomorphic JavaScript” in a 2011 blog post entitled “Scaling Isomorphic Javascript Code”. The term was later popularized by Spike Brehm in a 2013 blog post entitled “Isomorphic JavaScript: The Future of Web Apps” along with subsequent articles and conference talks. However, there has been some contention over the word “isomorphic” in the JavaScript community. Michael Jackson, a React.js trainer and coauthor of the react-router project, has suggested the term “universal” JavaScript. Jackson argues that the term “universal” highlights JavaScript code that can run “not only on servers and browsers, but on native devices and embedded architectures as well.”

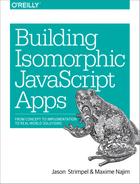

“Isomorphism,” on the other hand, is a mathematical term, which captures the notion of two mathematical objects that have corresponding or similar forms when we simply ignore their individual distinctions. When applying this mathematical concept to graph theory, it becomes easy to visualize. Take for example the two graphs in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Isomorphic graphs

These graphs are isomorphic, even though they look very different. The two graphs have the same number of nodes, with each node having the same number of edges. But what makes them isomorphic is that there exists a mapping for each node from the first graph to a corresponding node in the second graph while maintaining certain properties. For example, the node A can be mapped to node 1 while maintaining its adjacency in the second graph. In fact, all nodes in the first graph have an exact one-to-one correspondence to nodes in the second graph while maintaining adjacency.

This is what is nice about the “isomorphic” analogy. In order for JavaScript code to run in both the client and server environments, these environments have to be isomorphic; that is, there should exist a mapping of the client environment’s functionality to the server environment, and vice versa. Just as the two isomorphic graphs shown in Figure 3-1 have a mapping, so do isomorphic JavaScript environments.

JavaScript code that does not depend on environment-specific features—for example, code that avoids using the window or request objects—can easily run on both sides of the wire. But for JavaScript code that accesses environment-specific properties—e.g., req.path or window.location.pathname—a mapping (sometimes referred to as a “shim”) needs to be provided to abstract or “fill in” a given environment-specific property. This leads us to two general categories of isomorphic JavaScript: 1) environment agnostic and 2) shimmed for each environment.

Environment Agnostic

Environment-agnostic node modules use only pure JavaScript functionality, and no environment-specific APIs or properties like window (for the client) and process (for the server). Examples are Lodash.js, Async.js, Moment.js, Numeral.js, Math.js, and Handlebars.js, to name a few. Many modules fall into this category, and they simply work out of the box in an isomorphic application.

The only thing we need to address with these kinds of Node modules is that they use Node’s require(module_id) module loader. Browsers don’t support the node require(..) method. To deal with this, we need to use a build tool that will compile the Node modules for the browser. There are two main build tools that do just that: namely, Browserify and Webpack.

In Example 3-1, we use Moment.js to define a date formatter that will run on both the server and the client.

Example 3-1. Defining an isomorphic date formatter

'use strict';varmoment=require('moment');//Node-specific require statementvarformatDate=function(date){returnmoment(date).format('MMMM Do YYYY, h:mm:ss a');};module.exports=formatDate

We also have a simple main.js that will call the formatDate(..) function to format the current time:

varformatDate=require('./dateFormatter.js');console.log(formatDate(Date.now()));

When we run main.js on the server (using Node.js), we get the output like the following:

$nodemain.jsJuly25th2015,11:27:27pm

Browserify is a tool for compiling CommonJS modules by bundling up all the required Node modules for the browser. Using Browserify, we can output a bundled JavaScript file that is browser-friendly:

$browserifymain.js>bundle.js

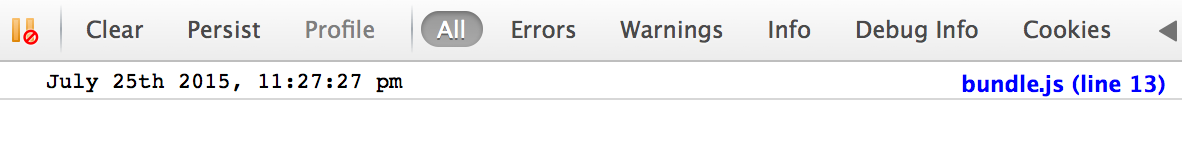

When we open the bundle.js file in a browser, we can see the same date message in the browser’s console (Figure 3-2).

<scriptsrc="bundle.js"></script>

Figure 3-2. Browser console output when running bundle.js

Pause for a second and think about what just happened. This is a simple example, but you can see the astonishing ramifications. With a simple build tool, we can easily share logic between the server and the client with very little effort. This opens many possibilities that we’ll dive deeper into in Part II of this book.

Shimmed for Each Environment

There are many differences between client- and server-side JavaScript. On the client there are global objects like window and different APIs like localStorage, the History API, and WebGL. On the server we are working in the context of a request/response lifecycle and the server has its own global objects.

Running the following code in the browser returns the current URL location of the browser. Changing the value of this property will redirect the page:

console.log(window.location.href);window.location.href='http://www.oreilly.com'

Running that same code on the server returns an error:

>console.log(window.location.href);ReferenceError:windowisnotdefined

This makes sense since window is not a global object on the server. In order to do the same redirect on the server we must write a header to the response object with a status code to indicate a URL redirection (e.g., 302) and the location that the client will navigate to:

varhttp=require('http');http.createServer(function(req,res){console.log(req.path);res.writeHead(302,{'Location':'http://www.oreilly.com'});res.end();}).listen(1337,'127.0.0.1');

As we can see, the server code looks much different from the client code. So, then, how do we run the same code on both sides of the wire?

We have two options. The first option is to extract the redirect logic into a separate module that is aware of which environment it is running in. The rest of the application code simply calls this module, being completely agnostic to the environment-specific implementation:

varredirect=require('shared-redirect');// Do some interesting application logic that decides if a redirect is requiredif(isRedirectRequired){redirect('http://www.oreilly.com');}// Continue with interesting application logic

With this approach the application logic becomes environment agnostic and can run on both the client and the server. The redirect(..) function implementation needs to account for the environment-specific implementations, but this is self-contained and does not bleed into the rest of the application logic. Here is a possible implementation of the redirect(..) function:

if(window){window.location.href='http://www.oreilly.com'}else{this._res.writeHead(302,{'Location':'http://www.oreilly.com'});}

Notice that this function must be aware of the window implementation and must use it accordingly.

The alternative approach is to simply use the server’s response interface on the client, but shimmed to use the window property instead. This way, the application code always calls res.writeHead(..), but in the browser this will be shimmed to call the window.location.href property. We will look into this approach in more detail in Part II of this book.

Summary

In this chapter, we looked at two different categories of isomorphic JavaScript code. We saw how easy it is to simply port environment-agnostic Node modules to the browser using a tool like Browserify. We also saw how environment-specific implementations can be shimmed for each environment to allow code to be reused on the client and the server. It’s now time to take it to the next level. In the next chapter we’ll go beyond server-side rendering and look at how isomorphic JavaScript can be used for different solutions. We’ll explore innovative, forward-looking application architectures that use isomorphic JavaScript to accomplish novel things.