Chapter 13. Full Stack Angular

In December 2012 I joined GetHuman. My first assignment was an interesting one. I needed to figure out a way to build a rich, real-time version of our popular flagship website, GetHuman.com. The challenge was essentially figuring out a way to combine two things that (at that time) did not often go together:

- A client-side JavaScript web app

- An SEO-friendly, performance-driven website

I had a wealth of experience with each of these separately, but never together. The most common solutions at that time for meeting these requirements usually boiled down to a Rails-like approach or a headless browser–based approach—both of which had significant downsides.

The Rails approach involved building a server-side website with small bits of JavaScript sprinkled on various pages. While this approach did a really good job for SEO and performance, it did not allow me to take advantage of advanced client-side features. Moreover, this solution felt like a traditional website, which is not what we wanted. We wanted a fast, responsive, and fluid user experience, which you typically could only achieve at that time with a client-driven, single-page application (SPA).

On the other end of the spectrum were the apps built completely on the client side using Backbone, Angular, Ember, or just plain vanilla JS. In order to make sure your client-side app was visible in search engines you would use a headless browser like PhantomJS to cache snapshots of your client-side application views. This sort of worked, but there were two big issues with headless browsers:

- They are too slow to use at runtime.

- They are too resource-intensive to use for sites that contain hundreds of thousands of pages, like GetHuman.

Clearly neither of these solutions was going to work for us. So, what could we do?

Isomorphic JavaScript: The Future of Web Apps

After trying out various client/server setups in an attempt to meet our needs, I ran across an article from Spike Brehm where he described a new approach to web development that he had implemented at Airbnb: isomorphic JavaScript. As Spike put it:

At the end of the day, we really want a hybrid of the new and old approaches: we want to serve fully-formed HTML from the server for performance and SEO, but we want the speed and flexibility of client-side application logic.

To this end, we’ve been experimenting at Airbnb with “Isomorphic JavaScript” apps, which are JavaScript applications that can run both on the client-side and the server-side.

This was exactly what we were looking for! Spike had perfectly described the thing that I couldn’t quite put into words; the thing that I had been searching for during the better part of 2013.

There was just one problem.

Conceptually I was completely in sync with Spike, but his specific Backbone-based solution was not exactly what I was looking for. I knew Backbone very well, but I preferred a relatively new framework, Angular.js. So why didn’t I just make Angular isomorphic, just like how Spike made Backbone isomorphic?

If you know anything about Angular.js, you know that this is easier said than done.

Isomorphic Angular 1

In order to implement server-side rendering in Backbone, Spike created a completely separate library called Rendr. He didn’t modify the existing Backbone library at all. I took a similar approach with Angular. Just like Backbone, Angular is tightly coupled to the DOM. So, the only ways to render on the server would be to either shim all of the client-side DOM objects like the window and browser, or create a higher-level API that your application can code against. We went with the former solution, which required us to build a layer of abstraction above Angular very similar to how Rendr works with Backbone.

After over a year of experimenting, testing, and iterating, we finally arrived at an elegant solution.

Similar to Rendr, we created a library called Jangular that allowed us to render our Angular web application on the server. The new GetHuman.com rendered the server view almost instantly, even under heavy load. After a of couple seconds the Angular client takes over the page and it comes to life with several real-time features. We thought we had solved the server-side rendering puzzle!

Unfortunately, there were a few issues with our Angular 1 server rendering solution:

- Jangular only supported a subset of Angular. Jangular could easily have been expanded, but we decided to initially only support the pieces of Angular we needed for GetHuman.com.

- Jangular enforced fairly rigid conventions, like a specific folder hierarchy, file-naming standards, and code structure.

In other words, we created a solution that worked great for us, but was difficult for anyone else to use.

ng-conf 2015

A couple of months after creating Jangular, I was invited to speak at ng-conf about our server rendering solution in Angular 1. Igor Minar, the technical lead for the Angular team at Google, reviewed my “Isomorphic Angular” slides before the conference and mentioned that what I was trying to do would be a lot easier in Angular 2. I didn’t quite understand at the time, but he told me that they had created an abstraction layer that should make it easy to render an Angular 2 app on the client or the server or anywhere else. So, I added a brief mention at the end of my ng-conf talk about the potential for server rendering being baked into the Angular 2 core. I said:

I think it is only a matter of time (whether I do it or I know a lot of other people that are going to be interested in this as well) [to leverage] all this new stuff in Angular 2 and [use] on some of the other stuff I’ve worked on [to build] a really awesome Isomorphic solution that everybody can use.

Right after my presentation, I met someone named Patrick Stapleton (also known as PatrickJS) who was just as interested as I was in isomorphic JavaScript. Patrick brought up the idea of us working together to make server rendering in Angular 2 a reality.

It didn’t take us long. One week after ng-conf, Patrick had some success (see Figure 13-1).

Figure 13-1. Isomorphic Angular 2!

After a flurry of discussions with developers from the Angular community and core team members, Brad Green, head of the Angular team, hooked us up with Tobias Bosch, the mastermind behind the Angular 2 rendering architecture. The three of us got to work.

Angular 2 Server Rendering

Three months later we had a working prototype and a much better understanding of the Angular 2 rendering architecture. In June 2015, we gave a presentation at AngularU on our Angular 2 server rendering solution.

You can watch this presentation online via YouTube.

The following is a summary of that talk.

Use Cases for Server Rendering

Each of these use cases provides a possible answer to the question: why is server rendering important for your client-side web app?

- Perceived load time

-

The initial load of a client-side web application is typically very slow. The Filament Group released a study recently that says the average initial page load time for simple Angular 1.x apps on mobile devices is 3–4 seconds. It can be even worse for more complex apps. This is most often an issue for consumer-facing apps, especially those that are typically accessed on a mobile device, but can be a problem for any app. The goal of rendering on the server for this use case is to lower the users’ perception of the initial page load time so that they see real content in under one second, regardless of device or connection speed. This goal is much easier to achieve consistently with server rendering than with client-side rendering.

- SEO

-

The Google search crawler continues to get better at indexing client-side rendered content, and there likely will be a future where server rendering is not needed for SEO, but today consumer-facing apps that really care about their search ranking need server rendering. Why?

-

First, the crawler isn’t perfect (yet). There are a number of situations where the crawler may not index exactly what is rendered. This is often due to either JavaScript incapabilities or timing issues with async loading.

-

With server rendering, the crawler can determine exactly how long it takes before the user sees content (i.e., the document complete event). This is not as easy on the client side (and, as mentioned in the previous use case, when it is measured, it is often much slower than server rendering).

-

There is no success story out there for a client-side-only web app that beats server-rendered websites for competitive keyword searches (for example, think about any major purchase item like “flat screen tv” or “best sedan 2015”).

-

- Browser support

-

The downside of using more advanced web technologies like Web Components is that it is hard to keep support for older browsers. This is why Angular 2 doesn’t officially support anything less than IE9. However, depending on the app being built, it may be possible to replace certain rich-client behaviors with server-side behaviors to support older browsers while letting app developers take advantage of the latest web platform. A couple of examples:

-

The app is mostly informational and it is OK for users on older browsers to just see the information without any of the client side functionality. In this case, it may be all right to give legacy browser users a completely server-rendered website while evergreen browser users get the full client-side app.

-

The app must support IE8. Most of the client-side web app functionality works, but there is one component that uses functionality not supported by IE8. For that one component, the app could potentially fetch the fully rendered partial HTML from the server.

-

- Link preview

-

Programs that show website previews for provided links rely on server rendering. Due to the complexity involved with capturing client-side rendered web pages, these programs will likely continue to rely on server rendering for the foreseeable future. The most well known examples involve social media platforms like Facebook, G+, or LinkedIn. Similar to the SEO use case, this is only relevant for consumer-facing apps.

The Web App Gap

The “Web App Gap” is a term I made up that represents the time between when a user makes a URL request and when the user has a functional visible web page in his browser. For most client-side web apps this means waiting for the server response, then downloading assets, initializing the client app framework, fetching data, and then finally painting to the screen. For many web applications, this gap ends up being 3–7 seconds or more. That is 3–7 seconds where the user is just sitting there looking at a blank screen, or maybe a spinner. And according to the Filament Group, “57% [of users] said they will abandon a page if its load time is 3 seconds or more.”

Many people today are spoiled by the mobile native user experience. They don’t care if it is a web or mobile app; they want the app instantly rendered and instantly functional. How can we do that with web apps? In other words, how can we eliminate the Web App Gap?

Well, there are four potential solutions:

- Shorten the gap

-

There are certainly many different types of performance optimizations, like minifying your client-side JavaScript or leveraging caching. The problem is that there are some things that are completely outside your control, such as network bandwidth, the power of the client device, etc.

- Lazy loading

-

In most cases, an initial client request results in a huge payload returned from the server. This initial payload includes many things that are not necessarily used in the initial view. If you could reduce the initial payload to only what is needed for the initial view, it would likely be very small and would load extremely fast. While this approach works, it is hard to set up. I have not seen anyone out there that has a library or framework to enable you to do this right out of the box effectively.

- Service workers

-

Addy Osmani recently presented the idea of using an application shell architecture where a service worker running inside the browser downloads and caches all resources so that subsequent visits to a particular URL will result in an application that is instantly rendered from the cache. The initial render, however, may still be slow as resources, download and not all browsers support service workers (see “Can I use...?”).

- Server rendering

-

The initial server response contains a fully rendered page that can be displayed to the user immediately. Then, as the user starts looking over the page and deciding what to do, the client app loads in the background. Once the client finishes initializing and getting any data that it needs, it takes over and controls everything from there.

This last solution is built into Angular 2, and you can get it for free.

Angular 2 Rendering Architecture

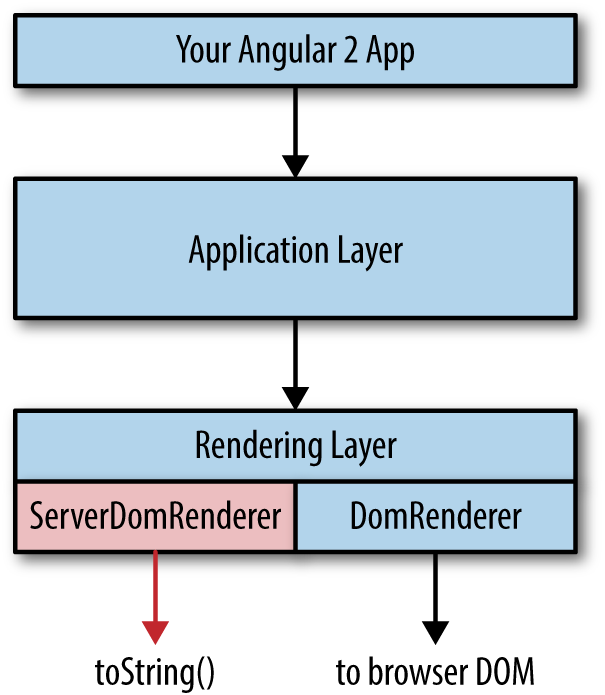

The Angular 2 server rendering architecture is laid out in Figure 13-2.

Figure 13-2. Angular 2 server rendering

Let’s break this down:

- Your Angular 2 app

-

At the top of the diagram is your custom code that you write on top of Angular 2. Your custom code interfaces with the Angular 2 application-layer API.

- Application layer

-

The application layer has no dependencies on any specific environment. This means there is no direct reference to the

windowobject or thebrowserobject or the Node.jsprocessobject. Everything in the application layer can be run in the browser or on the server or on a mobile device. This layer will run your components, make HTTP calls, and “compile” your app. The output of the compilation process is a component tree where each component contains two primary data objects: the bindings and something called a ProtoView, which is essentially an internal representation of a component template. The component tree is passed from the application layer to the rendering layer. - Rendering layer

-

There are two parts to the rendering layer. The first part is a common interface that is referenced by the application layer. That interface then defers to a specific

Renderer. The default is theDomRenderer, which outputs to the browser DOM, but this can be easily overwritten through the Angular 2 Dependency Injector. For server rendering, we wrote theServerDomRenderer, which outputs HTML to a string. The server-side bootstrap process sets theServerDomRendererinstead of theDomRenderer.

The only caveat when you want your Angular 2 app to render on the server is that you can’t directly reference any DOM objects in your code. For example, instead of using the global window object, you would use the Window class that is part of the Angular 2 API. This makes it easy for Angular 2 to limit the surface area of global client-side objects and provide some level of guarantee that equivalent functionality will exist on the server.

Preboot

Near the end of the presentation I threw in one more thing that we had just recently figured out. The approach we took improved perceived performance, but there was an issue. What happens to user events on the page between the time the user can see the server-rendered view and the time when the client takes over and has control? As we have talked about, that can sometimes be 2–6 seconds or more. During this time, the user can see something but may become frustrated as she attempts to interact with the page and nothing happens (or, worse, something unexpected happens). This is especially a problem with forms. For example, what happens when a user clicks a submit button on a server-rendered view before the client has control? And what happens if the user is in the process of typing in a text box during the switch from server to client view?

The most common solutions for this type of situation usually include:

- Don’t use server rendering for client-side forms.

- Disable form elements until the client bootstrap is complete.

We didn’t like either of these solutions, so we created a new library called Preboot that was designed to handle events in a server view before the client takes control. So, the user can type in a text box, click a button, or perform any other activity on a page and the client will seamlessly handle those events once the client-side bootstrap is complete. The user experience in most cases is that the page is instantly functional, which is exactly what we were trying to achieve.

And the best part is that this library is not Angular 2 specific. You can use this with Angular 1, and you can use it with React or Ember or any other framework. Pretty awesome stuff.

Angular Universal

The response to our AngularU talk was loud and emphatic. Developers loved the idea and wanted to use the feature as soon as possible. Brad and Tobias decided to turn our efforts into an official project under the Angular banner and call it Angular Universal.

Before we moved to this official Angular repo, much of what we did was completely outside the core Angular 2 libraries. Over the course of the following three months, we started to move several pieces into the core. By the time Angular 2 is released, we expect the Angular Universal library to be extremely thin and to mostly consist of integration libraries for specific backend Node.js frameworks like Express or Hapi.js.

Full-Stack Angular 2

Up to this point I have only talked about server rendering, but that is just one part of a much bigger concept: full-stack JavaScript development. Server rendering often gets the most focus because it can be the hardest challenge to overcome, but the real goal is using the same JavaScript everywhere for everything. It turns out that Angular 2 is an amazing framework to use for this purpose. Before we get to that, however, let me take a step back and explain why you should care about full-stack JavaScript development.

One piece of advice many of us have heard before is “use the right tool for the job.” It sounds smart. And it is... to a degree. The problem is that the implementation of this idea doesn’t always work out the way you might hope. Here are some of the issues we face:

- Committees

-

At many large organizations you can’t just choose some new technology and start using it. You need to get it approved by three or four or five different committees (which is always fun). And when you do this, the decision may end up being more political than based on merit.

- Contention

-

In some work environments, choosing a technology can cause a lot of tension among team members who have different options.

- Context switching

-

Even if you don’t have one of the first two issues, when you work in a diverse technical environment you run into problems with context switching. Either developers end up working on many different technologies, in which case there is some mental loss when they switch from one thing to another, or you split your teams along technical boundaries, in which case there is still some loss in productivity from the additional communication that is needed.

- Code duplication

-

Finally, it is nearly impossible to avoid code duplication when you have a diverse technical environment. Typically there are things common throughout the organization, like security standards and data models, that need to be implemented within each language.

How many people do you think have run into one of these problems at work? There are many ways to solve or avoid these issues, but I have one simple solution: use a hammer and treat everything as a nail. Just pick one primary technology, and use that for nearly everything. If you can do that, all of these problems go away.

Of course, that sounds great in theory... but the reality is that for a long time there haven’t been any great tools that are capable of being this magical hammer that can do everything. JavaScript is the only thing that runs everywhere, so if you want to try to use one technology for everything, it has to be JavaScript.

That is sort of weird to think about, given the fact that JavaScript used to be terrible in the browser, let alone on the server or in mobile devices. But it has been getting better and better over the years. It is now to the point where we are on the precipice of something amazing.

So yes, it is hard to fulfill the promise of full-stack development with vanilla ES5 JavaScript—but when you combine some of the features of ES6 and ES7 with Angular 2, you have all you need to start building amazing full-stack applications. Here are some of the features that help make full-stack development easy:

- Universal dependency injection

-

Angular 1 DI was effective, but somewhat flawed. Angular 2 DI is absolutely amazing. Not only does it work on the client or the server, but it can be used outside Angular altogether. This makes it extremely easy to build a full-stack application because you can use DI to switch out any container-specific code (e.g., code tightly coupled to the browser that references the

windowobject). - Universal server rendering

-

We discussed this earlier.

- Universal event emitting

-

Angular 2 leverages RxJS observables for events. This works the same way on the client and the server. In Angular 1, event emitting was tied to the client-side

$scope, which doesn’t exist on the server. - Universal routing

-

Similar to event emitting, routing in Angular 2 works equally well on the client and the server.

- ES6 modules

-

One module format to rule them all! Now you can author your JavaScript in one format that can be used everywhere.

- ES7 decorators (TypeScript)

-

When doing large full-stack development, there are often cross-cutting concerns like security and caching that can be more easily implemented with custom decorators in TypeScript.

- Tooling (Webpack, JSPM, Browserify)

-

All the new module bundlers are able to take one entry point and walk the dependency tree in order to generate one packaged JavaScript file. This is extremely helpful for full-stack development because it means you don’t have to have separate /server and /client folders. Instead, all the client-side files are picked out through the dependency tree.

GetHuman.com

I mentioned earlier that I had created a server rendering solution in Angular 1 for GetHuman. At the time I am writing this chapter, this solution has been in production for over six months. So, was the promise of server rendering and full-stack development fulfilled?

I can say unequivocally and definitively, yes. Consider the following:

- Performance

In many cases, users see the initial view in just over one second.

- Scalability

We have been able to easily support 1,000+ simultaneous users with just three single-core web servers.

- Productivity

Up until recently, we only had two full-time developers working on a dozen different web apps.

We continue to iterate and improve our Angular 1 infrastructure while at the same time prototyping what we will do with Angular 2. To that end, I have created an open source ecommerce app at FullStackAngular2.com where we hope to come up with an idiomatic way of building full-stack apps with Angular 2.