Appendix B

Notation and Other Background Information

This appendix describes most of the material that is needed to follow the ideas presented in this book without covering ideas from cryptography. First, standard notations are described that are used throughout the text as well as well-known definitions from number theory. Some basic facts and algorithms from number theory are also given. The appendix then focuses on a set of computational problems in the field of computational number theory. Most of these computational problems are believed to be intractable and many have only been identified recently. The appendix concludes with a description of the random oracle model.

B.1 Notation Used Throughout the Book

In this section notation as well as some basic definitions are given that are used throughout the book. String notation is given followed by logic operations and logic statements. Standard notation from number theory is then given along with basic definitions. This is followed by set theory notation and notation from probability theory. The section concludes with asymptotic notation.

When a is a bit string, |a| denotes the length of a in bits. For example, |01001| = 5. The operator || denotes string concatenation. So, if a and b are bit strings then a||b denotes the bit string that results from concatenating a with b. For example, 010||11 = 01011. When x is a positive integer it is understood that |x| denotes the length of x in bits when x is represented in base 2. The set of strings that are each m-bits in length is denoted by {0, 1}m. The set of all bit strings that are each countably infinite in length is denoted by {0, 1}∞.

The operator ⊕ denotes the bitwise exclusive-or operation, also denoted by XOR. So, a ⊕ b denotes the bitwise XOR of bit string a with bit string b. The bit strings a and b in a ⊕ b must be the same length in bits. For example, 0011 ⊕ 0101 = 0110. The notation  denotes “if and only if.” This is used for logic statements in which A is true if and only if B is true, written as A

denotes “if and only if.” This is used for logic statements in which A is true if and only if B is true, written as A  B. The notation

B. The notation  is typically used in descriptions of digital signature algorithms and other cryptographic algorithms that require equality testing. It is a Boolean operator that takes two integers a and b as input. The value a

is typically used in descriptions of digital signature algorithms and other cryptographic algorithms that require equality testing. It is a Boolean operator that takes two integers a and b as input. The value a  b returns true if a equals b and false otherwise.

b returns true if a equals b and false otherwise.

The function gcd denotes the greatest common divisor function. Thus, gcd(a, b) returns the greatest common divisor of integers a and b. For example, gcd(10, 15) = 5.

If a and b are integers, then a is said to be congruent to b modulo n if n divides a – b evenly. This is written as,

We say that “a is congruent to b modulo n.” The integer n is referred to as the modulus of the congruence. For example, 5 ≡ 19 mod 7, 0 ≡ 8 mod 4, and −1 ≡ 9 mod 5.

denotes the set of integers modulo n. So,

denotes the set of integers modulo n. So,  = {0, 1, 2, 3,..., n −1}. The multiplicative group of

= {0, 1, 2, 3,..., n −1}. The multiplicative group of  is denoted by

is denoted by  . It is common practice to be sloppy and let

. It is common practice to be sloppy and let  also refer to the set that the group is defined over. So,

also refer to the set that the group is defined over. So,  consists of all elements a

consists of all elements a

such that gcd(a, n) = 1. If n is prime then the set

such that gcd(a, n) = 1. If n is prime then the set  consists of all integers a such that 1 ≤ a < n. When A and B are sets then A − B denotes set subtraction. For example, S = A − B may be found by setting S = A and then removing from S each element e that is in both A and B. For example, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} − {2, 4} = {1, 3, 5}. The notation

consists of all integers a such that 1 ≤ a < n. When A and B are sets then A − B denotes set subtraction. For example, S = A − B may be found by setting S = A and then removing from S each element e that is in both A and B. For example, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} − {2, 4} = {1, 3, 5}. The notation  is used to denote “contained in.” When S is a set of elements and an element a is contained in S we write a

is used to denote “contained in.” When S is a set of elements and an element a is contained in S we write a  S. For example, 2

S. For example, 2

5. But, it is incorrect to say 5

5. But, it is incorrect to say 5

5.

5.

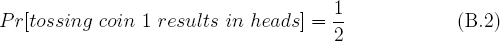

The notation Pr[A] is used to indicate the probability that event A occurs. For example,

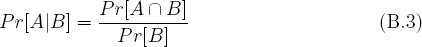

indicates that coin 1 is a fair coin since heads comes up with probability 50 percent. The notation Pr[A|B] denotes the conditional probability that event A will occur given that event B occurs. Recall that,

where A and B are events.

The notation f(·) is used to denote a function f that takes one argument as input. The dot is used as a placeholder for the argument. For example, f(x) = 2x3 + x − 1. Similarly, f(·, ·) denotes a function that takes two arguments as input. For example, f(x, y) = 3x2 − 2xy + 4y + 1.

Big-O notation is used in this book. Informally, f(n) = O(g(n)) means that f does not grow faster asymptotically than g(n) within a constant multiple. Formally speaking, this holds when there exists a constant c > 0 and an integer n0 > 0 such that 0 ≤ f(n) ≤ cg(n) for all n ≥ n0. A polynomial time algorithm is an algorithm that has a worst-case running time of O(nk) where k is a constant and n is the size of the input to the algorithm. Generally speaking, poly-time algorithms are algorithms that can be expected to yield answers within a reasonable length of time.

B.2 Basic Facts from Number Theory and Algorithmics

Number theory is a branch of mathematics that is central to modern cryptography and hence computer security. It is characterized by an enumerable number of problems whose elegance and simplicity are matched only by their difficulty in solving. There are a number of great introductory books on the subject [96, 128, 164, 247]. Many public key cryptosystems are rooted in unsolved problems in computational number theory and as such a basic understanding of this branch of mathematics is critical in understanding public key cryptography. This section is by no means a comprehensive introduction to the subject. The goal here is to convey some of the basic ideas so that the reader will know where to look for more information.

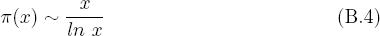

The Prime Number Theorem1 [164] can be used to estimate the probability that a randomly chosen number is prime.

The function π(x) is defined as the number of prime numbers less than or equal to x. Generally speaking, a randomly chosen k-bit number is prime with probability about 1/k.

The greatest common divisor of two integers can be computed using the Euclidean algorithm. Hence, this algorithm is used to compute d = gcd(a, b) for two integers a and b. This may well be one of the oldest non-trivial algorithms in the history of algorithmics. A more general computational problem is to compute the two integers x and y in ax + by = d where a and b are non-negative integers with a > b. The extended Euclidean algorithm solves this computational problem efficiently. It is often used to compute multiplicative inverses. For example, it is used to compute the RSA private key d given e, p, and q (see Appendix C.1.7).

To describe various public key cryptosystems it is necessary to cover Euler's totient function  (·). It takes a single integer as an argument and has various properties. If p is prime and k ≥ 1 then

(·). It takes a single integer as an argument and has various properties. If p is prime and k ≥ 1 then  (pk) = (p − 1)pk−1. The function is multiplicative. In other words, if gcd(a, b) = 1 then

(pk) = (p − 1)pk−1. The function is multiplicative. In other words, if gcd(a, b) = 1 then  (ab) =

(ab) =  (a) *

(a) *  (b). Finally, if

(b). Finally, if

where the pi's are distinct primes and ei ≥ 1 for 1 ≤ i ≤ m, then

The symbol  is used to denote Carmichael's lambda function. This function is defined as follows. The value

is used to denote Carmichael's lambda function. This function is defined as follows. The value  (2) = 1,

(2) = 1,  (4) = 2, and

(4) = 2, and  (2t) = 2t−2 if t ≥ 3. Also, if n is a positive integer with prime-power factorization

(2t) = 2t−2 if t ≥ 3. Also, if n is a positive integer with prime-power factorization  then

then  (n) is the least common multiple of

(n) is the least common multiple of  . The value

. The value  (n) is also commonly referred to as the minimal universal exponent [247].

(n) is also commonly referred to as the minimal universal exponent [247].

A generator g of  is an element that is capable of generating all elements in the set

is an element that is capable of generating all elements in the set  by exponentiating g modulo n. More formally, if g is a generator of

by exponentiating g modulo n. More formally, if g is a generator of  then

then  consists of the elements gl mod n for 0 ≤ i ≤

consists of the elements gl mod n for 0 ≤ i ≤  (n) − 1. So, using modular exponentiation g is capable of generating this set. If

(n) − 1. So, using modular exponentiation g is capable of generating this set. If  has a generator then

has a generator then  is said to be cyclic.

is said to be cyclic.

The value g is a generator of  if and only if,

if and only if,

for every prime divisor p of  (n). This immediately suggests a way to find a generator for a given value n. Provided that the factorization of

(n). This immediately suggests a way to find a generator for a given value n. Provided that the factorization of  (n) is known, the inequality B.7 is verified for each prime divisor of

(n) is known, the inequality B.7 is verified for each prime divisor of  (n). If there exists a prime divisor p for which it does not hold, then g is not a generator. If

(n). If there exists a prime divisor p for which it does not hold, then g is not a generator. If  is cyclic then the number of generators is

is cyclic then the number of generators is  (

( (n)). So, it is often possible to find a generator by choosing g uniformly at random from

(n)). So, it is often possible to find a generator by choosing g uniformly at random from  and performing this test.

and performing this test.

An algorithm is needed to compute y = gx mod p when g, x and p are large (for example, 1024-bit quantities). To see this, note that a 1024-bit number g raised to a 1024-bit number is a quantity so large that it will never fit within the memory of a computer system. The value y can be computed using the square-and-multiply algorithm. This algorithm works by repeatedly squaring the value g and reducing modulo p after each squaring. The end result is 1024 values each of which are about 1024 bits in length. The quantities are g, g2 mod p, g4 mod p, g8 mod p, and so on. Depending on where binary ones appear in the exponent x, these values can be multiplied to compute y, all the while reducing modulo p.

There are even faster approaches. For example, vector addition chains may be used in concert with Karatsuba multiplication and Montgomery reduction. Also, when the base g is fixed, it is possible to speed things up by precomputing the powers of g as previously mentioned.

The value a

is a quadratic residue modulo n if there exists an x

is a quadratic residue modulo n if there exists an x

such that a ≡ x2 mod n. If no such x exists then a is a quadratic non-residue modulo n. Euler's criterion is a method that may be used to test if a given integer a is a quadratic residue modulo a prime p or not. The value a is a quadratic residue modulo p if and only if

such that a ≡ x2 mod n. If no such x exists then a is a quadratic non-residue modulo n. Euler's criterion is a method that may be used to test if a given integer a is a quadratic residue modulo a prime p or not. The value a is a quadratic residue modulo p if and only if  mod p = 1.

mod p = 1.

Quadratic residuosity is so pervasive in number theory that it has its own symbolic representation. The Legendre symbol is a tool for noting whether or not a is a quadratic residue modulo the prime p. The Legendre of a with respect to p is written as L(a/p) and is only defined for odd primes p and integers a. Note that this does not indicate that a is divided by p. It is notation for a symbol that has one of three values: 0, 1, or −1. The value L(a/p) is 0 if p divides a evenly. It is 1 if a is a quadratic residue modulo p, and it is —1 if a is a quadratic non-residue modulo p. Euler's criterion may be used to evaluate the Legendre of a with respect to p.

The Jacobi symbol J(a/n) is a generalization of the Legendre symbol. The Legendre symbol only applies to odd primes p whereas the Jacobi symbol applies to all odd numbers n ≥ 3. Let n be as defined in equation B.5. The Jacobi of a with respect to n is defined as follows,

Note that if n is prime then the Jacobi symbol equals the Legendre symbol.2

The notation  (+1) is used to represent the set of values a

(+1) is used to represent the set of values a

such that J(a/n) = 1. A pseudosquare modulo n = pq where p and q are prime is a quadratic non-residue y such that J(y/n) = 1.

such that J(a/n) = 1. A pseudosquare modulo n = pq where p and q are prime is a quadratic non-residue y such that J(y/n) = 1.

Note that when n is the product of two distinct primes p and q, the pair (L(a/p),L(a/q)) can have any of four possible values. These four possible values are (1, 1), (−1, −1), (−1, 1), and (1, −1). The value a is a quadratic residue only in the case of (1, 1). The value a is a pseudosquare only in the case of (−1, −1). Furthermore, the number of quadratic residues in  (+1) equals the number of pseudosquares in

(+1) equals the number of pseudosquares in  (+1).

(+1).

The following definition is relevant to the Paillier cryptosystem. Consider the integers modulo n2. A number a is said to be an nth residue modulo n2 if there exists a number y

such that a = yn mod n2. Furthermore, the set of nth residues is a multiplicative subgroup of

such that a = yn mod n2. Furthermore, the set of nth residues is a multiplicative subgroup of  of order

of order  (n). Every nth residue a has exactly n roots, each of degree n.

(n). Every nth residue a has exactly n roots, each of degree n.

B.3 Intractability: Malware's Biggest Ally

Modern cryptography is made possible by the failures in modern algorithmics. Cryptosystems such as RSA and the Diffie-Hellman key exchange are regarded as secure since they are based on computational problems that are presumed to be intractable. It is well known that if you can factor, then you can break RSA, and so it is these very problems that keep unwanted intruders at bay.

Yet this entire book is dedicated to showing how these same cryptographic primitives can be used to mount novel attacks on host cryptosystems. The simplest such attack is a denial-of-service attack in which a virus public key encrypts critical host data. When backups aren't available, only the virus author can restore the information since only the virus author has the needed private decryption key. Intractability is therefore a powerful ally in the hands of malicious software programs.

In this section several computational problems in number theory are described. They form the basis of security for several public key cryptosystems. Some of these problems related to others in known ways. Most of the problems described in this section are assumed to be intractable in the proofs of security for various cryptosystems. However, the Phi-Sampling assumption is a necessary assumption for a given scheme to work properly.3 Many of the known relationships between these problems are described.

B.3.1 The Factoring Problem

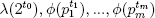

The Rabin cryptosystem is based on the assumed intractability of solving the factoring problem (see Appendix C.1.5). This is often referred to as the factoring assumption. In the case of Rabin and other cryptosystems we are interested in whether or not the factoring problem is solvable for the product of two distinct primes p and q. The more general integer factorization problem is the following. Given an integer n find its factorization. That is, find p1, p2,...,pm, and e1, e2,..., em as in equation B.5.

The integer factorization problem is contained in the complexity class known as FNP. FNP is a class of function problems that have the following form: given an input x and a polynomial time predicate F(x,y), if there exists a y satisfying F(x,y) then output any such y, otherwise output “no.” This is not to be confused with NP, the set of decision problems that are solvable by polynomial time Turing machines that answer “yes” if at least one computation path accepts and “no” otherwise.

There exist a number of algorithms for solving the factoring problem. Examples include the quadratic sieve method [82, 228] and the number field sieve [44, 171]. Yet there is no known algorithm to date that can efficiently factor RSA moduli n that are 768 bits or larger.

B.3.2 The eth Roots Problem

The RSA cryptosystem is based on the assumed intractability of solving the eth roots problem (see Appendix C.1.7) where e ≥ 3. This is often referred to as the eth roots assumption or the RSA assumption. The eth roots problem is as follows. Given a composite number n, an integer e ≥ 3 such that gcd(e,  (n)) = 1, and an integer c

(n)) = 1, and an integer c

, find an integer m such that me ≡ c mod n. The RSA problem is to solve the eth roots problem when n is the product of two distinct primes p and q.

, find an integer m such that me ≡ c mod n. The RSA problem is to solve the eth roots problem when n is the product of two distinct primes p and q.

The RSA problem is trivially solvable if factoring is solvable. To see this, note that if the factors p and q can be computed from n, then d can be computed such that ed = 1 mod (p − 1)(q − 1) using the extended Euclidean algorithm. The value d is the private exponent corresponding to the RSA public key (e, n). So once d has been found the RSA problem can be solved using RSA decryption.

When e = 2 the problem is to compute square roots modulo n. This problem has been proven to be equivalent to the factoring problem [237]. The non-trivial implication is proven using a randomized reduction argument that shows how to factor n given an oracle that returns a square root.

B.3.3 The Composite Residuosity Problem

The Paillier public key cryptosystem constitutes a one-way trapdoor under the assumed intractability of solving the computational composite residuosity problem (see Subsection 5.2.4). Let n be the product of two large primes p and q. Let g be an element of  having an order that is a non-zero multiple of n. The computational composite residuosity problem is as follows. Given n, g, and w

having an order that is a non-zero multiple of n. The computational composite residuosity problem is as follows. Given n, g, and w

, compute the unique value x

, compute the unique value x

for which there exists a y

for which there exists a y

such that gxyn ≡ w mod n2. The computational composite residuosity assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. The problem of inverting the Paillier cryptosystem is by definition the problem of solving the computational composite residuosity problem. It has been shown that this problem is solvable if the RSA problem is solvable when the public RSA exponent e equals n [216].

such that gxyn ≡ w mod n2. The computational composite residuosity assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. The problem of inverting the Paillier cryptosystem is by definition the problem of solving the computational composite residuosity problem. It has been shown that this problem is solvable if the RSA problem is solvable when the public RSA exponent e equals n [216].

B.3.4 The Decision Composite Residuosity Problem

The Paillier public key cryptosystem is semantically secure against plaintext attacks based on the assumed intractability of solving the decision composite residuosity problem. Let n be the product of two large primes p and q. Let g be an element of  having an order that is a non-zero multiple of n. The decision composite residuosity problem is as follows. Given n, g, w

having an order that is a non-zero multiple of n. The decision composite residuosity problem is as follows. Given n, g, w

, and a value x

, and a value x

, decide whether or not there exists a y

, decide whether or not there exists a y

such that gxyn ≡ w mod n2. The decision composite residuosity assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. There exist other cryptosystems that are predicated on the difficulty of deciding higher order residuosity [23, 196]. It has been shown that the ability to solve the computational composite residuosity problem implies the ability to solve the decision composite residuosity problem [216].

such that gxyn ≡ w mod n2. The decision composite residuosity assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. There exist other cryptosystems that are predicated on the difficulty of deciding higher order residuosity [23, 196]. It has been shown that the ability to solve the computational composite residuosity problem implies the ability to solve the decision composite residuosity problem [216].

B.3.5 The Quadratic Residuosity Problem

The Goldwasser-Micali public key cryptosystem is based on the assumed intractability of solving the quadratic residuosity problem (see Appendix C.1.9). Let n be an odd composite integer. The quadratic residuosity problem is as follows. Given n and a randomly chosen element a from  (+1) decide whether or not a is a quadratic residue modulo n. The quadratic residuosity assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem.

(+1) decide whether or not a is a quadratic residue modulo n. The quadratic residuosity assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem.

The Goldwasser-Micali cryptosystem is concerned with the particular case that n is the product of two distinct large primes. This problem is easily solvable if factoring is solvable. If factoring is solvable then p and q can be computed efficiently given n. The value a is a quadratic residue modulo n if and only if L(a/p) = 1 and L(a/q) = 1. So, using Euler's criterion, these two Legendre symbols can be computed using p and q.

B.3.6 The Phi-Hiding Problem

The Phi-Hiding private information retrieval scheme is based on the assumed intractability of solving the Phi-Hiding problem (see Subsection 6.2.1). The formal definition of the Phi-Hiding assumption was given by Cachin et al in Eurocrypt '99 [48]. It is a relatively new intractability assumption and as such many readers may not be familiar with it. For this reason both an informal and formal definition of it is given.

Let m be the product of two large primes p and q. Let p0 and p1 be b-bit primes such that only one of them divides  (m) evenly. Recall that

(m) evenly. Recall that  is the Greek letter phi. Informally, the Phi-Hiding problem is as follows. Given m, p0, and p1 decide with non-negligible probability whether p0 divides

is the Greek letter phi. Informally, the Phi-Hiding problem is as follows. Given m, p0, and p1 decide with non-negligible probability whether p0 divides  (m) evenly or whether p1 divides

(m) evenly or whether p1 divides  (m) evenly. Informally, the Phi-Hiding assumption is that no efficient algorithm exists that solves this problem. We say that a composite integer m

(m) evenly. Informally, the Phi-Hiding assumption is that no efficient algorithm exists that solves this problem. We say that a composite integer m  -hides a prime p1 if p1 divides

-hides a prime p1 if p1 divides  (m) evenly.

(m) evenly.

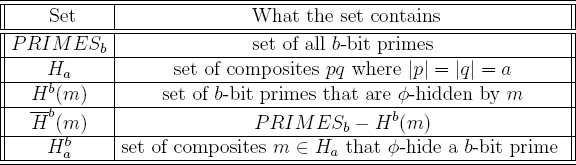

The formal definition of the Phi-Hiding assumption will now be given. Rather than utilizing the notion of a probabilistic Turing machine, the definition utilizes a different computational model. It is based on the notion of a circuit. A k-gate circuit is a finite function that is computable by acyclic circuitry that consists of k gates in which a gate implements the NOT logical operation or the AND logical operation. The definition also utilizes a number of number theoretic sets. These are given in Table B.1.

It follows from Table B.1 that  (m) is the set of b-bit primes that are not

(m) is the set of b-bit primes that are not  -hidden by m. Recall that a poly-time Turing machine M is a machine that on input x

-hidden by m. Recall that a poly-time Turing machine M is a machine that on input x  {0, 1}* halts in at most p(|x|) steps where p(t) is a polynomial in t.

{0, 1}* halts in at most p(|x|) steps where p(t) is a polynomial in t.

Phi-Hiding Assumption: There exist constants e, f, g, h > 0 such that for all k > h and for all 2ek-gate circuits C, after the ordered execution of the following steps:

- choose a composite m randomly from

,

, - choose p0 randomly from Hk(m),

- choose p1 randomly from

(m),

(m),

Table B.1 Sets relating to the Φ-hiding assumption

- choose a bit b randomly,

the probability that C(m, pb) = b is less than  .

.

The Phi-Hiding problem is to find a circuit C that violates this assumption.

Revealing a large prime p1 that divides  (m) evenly may expose the factorization of m. Coppersmith gave an efficient algorithm that factors m on input m and p1 if p1 > m¼ and p1 divides

(m) evenly may expose the factorization of m. Coppersmith gave an efficient algorithm that factors m on input m and p1 if p1 > m¼ and p1 divides  (m) evenly [73, 74]. Therefore, it is easy to decide if p1 divides n when p1 > m¼. Also, this assumption does not hold when p1 = 3 and m ≡ 2 mod 3 where m = pq. To see this, note that one of p or q is congruent to 1 mod 3 and the other is congruent to 2 mod 3. Suppose that p = 3k1 + 1 and q = 3k2 + 2 for some integers k1 and k2. Clearly, 3 divides (p − 1)(q − 1) in this case.

(m) evenly [73, 74]. Therefore, it is easy to decide if p1 divides n when p1 > m¼. Also, this assumption does not hold when p1 = 3 and m ≡ 2 mod 3 where m = pq. To see this, note that one of p or q is congruent to 1 mod 3 and the other is congruent to 2 mod 3. Suppose that p = 3k1 + 1 and q = 3k2 + 2 for some integers k1 and k2. Clearly, 3 divides (p − 1)(q − 1) in this case.

The Phi-Hiding assumption is a conservative assumption regarding the security of  (m) even though the prime p1 that divides

(m) even though the prime p1 that divides  (m) is available to the distinguisher D. To see this, note that the prime p1 is not assumed to be a constant fraction shorter than m, but polynomially shorter. This follows from the assumed existence of f to constitute the kf-bit composite m.

(m) is available to the distinguisher D. To see this, note that the prime p1 is not assumed to be a constant fraction shorter than m, but polynomially shorter. This follows from the assumed existence of f to constitute the kf-bit composite m.

B.3.7 The Phi-Sampling Problem

The completeness4 of the Phi-Hiding PIR scheme is based on the assumed tractability of performing  -sampling (see Subsection 6.2.1). Let p1 be a given prime number. Informally, the Phi-Sampling problem is to efficiently find a random composite5 m such that p1 divides

-sampling (see Subsection 6.2.1). Let p1 be a given prime number. Informally, the Phi-Sampling problem is to efficiently find a random composite5 m such that p1 divides  (m) evenly. The Phi-Sampling assumption is that the Phi-Sampling problem is tractable. The formal definition of the Phi-Sampling problem will now be given. The definition utilizes the set

(m) evenly. The Phi-Sampling assumption is that the Phi-Sampling problem is tractable. The formal definition of the Phi-Sampling problem will now be given. The definition utilizes the set  as defined in Table B.1.

as defined in Table B.1.

Phi-Sampling Assumption: There exists a constant h > 0 such that for all k > h, there exists a probabilistic poly-time Turing machine S such that for all k-bit primes p1, S(p1) outputs the factorization of a random kf-bit number m

where p1 divides

where p1 divides  (m) evenly.

(m) evenly.

B.3.8 The Discrete Logarithm Problem

The Pointcheval-Stern digital signature algorithm is based on the assumed intractability of the discrete logarithm problem (see Appendix C.2.5). Let p be a prime such that p − 1 has a large prime divisor. Let g be a generator of  . Informally, the discrete logarithm problem is to compute a given (g, p, ga mod p) for randomly chosen a < p − 1. The discrete logarithm assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. This problem is efficiently solvable using the Pohlig-Hellman algorithm when all prime divisors of p − 1 are small [224]. When this is the case p − 1 is said to be a smooth integer.

. Informally, the discrete logarithm problem is to compute a given (g, p, ga mod p) for randomly chosen a < p − 1. The discrete logarithm assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. This problem is efficiently solvable using the Pohlig-Hellman algorithm when all prime divisors of p − 1 are small [224]. When this is the case p − 1 is said to be a smooth integer.

B.3.9 The Computational Diffie-Hellman Problem

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange is based on the assumed intractability of solving the Diffie-Hellman problem (see Subsection C.1.2). Let p be a prime such that p − 1 has a large prime divisor. Let g be a generator of  . Informally, the computational Diffie-Hellman problem is to compute gab mod p given (g, p, ga mod p, gb mod p) for randomly chosen exponents a and b. The computational Diffie-Hellman assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. The set of values (ga mod p, gb mod p, gab mod p) is called a Diffie-Hellman triple.

. Informally, the computational Diffie-Hellman problem is to compute gab mod p given (g, p, ga mod p, gb mod p) for randomly chosen exponents a and b. The computational Diffie-Hellman assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time algorithm exists that solves this problem. The set of values (ga mod p, gb mod p, gab mod p) is called a Diffie-Hellman triple.

If the discrete logarithm problem can be efficiently solved then so can the Diffie-Hellman problem. This can be shown via a randomized reduction argument. It has yet to be shown whether or not the ability to solve Diffie-Hellman implies the ability to solve the discrete logarithm problem in the general case. These two problems have been shown to be equivalent in certain cases [84, 181, 182, 183]. There have been some results on the hardness of computing individual bits in a Diffie-Hellman shared secret [34].

B.3.10 The Decision Diffie-Hellman Problem

The Cramer-Shoup cryptosystem is based on the assumed intractability of solving the Decision Diffie-Hellman (DDH) problem (see Appendix C.2.3). Let p be a prime. Let g be an element that generates a large subgroup of  . Also, let the order of g have no small prime divisors. Informally, the DDH problem is to distinguish with non-negligible probability the triple (ga mod p, gb mod p, gab mod p) from the triple (ga mod p,gb mod p,gc mod p) where a, b, and c are chosen randomly modulo the order of g. The Decision Diffie-Hellman assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time distinguisher exists that solves this problem.

. Also, let the order of g have no small prime divisors. Informally, the DDH problem is to distinguish with non-negligible probability the triple (ga mod p, gb mod p, gab mod p) from the triple (ga mod p,gb mod p,gc mod p) where a, b, and c are chosen randomly modulo the order of g. The Decision Diffie-Hellman assumption is that no probabilistic poly-time distinguisher exists that solves this problem.

If the order of g is divisible by a small prime r ≥ 2, then it is possible to distinguish randomly chosen Diffie-Hellman triples from randomly chosen triples. This follows from the fact that the rth residuosity of each of the values,

can be determined. For example, if the prime 2 divides the order of g evenly, then testing for quadratic residuosity can help indicate the presence of Diffie-Hellman triples. To see this, note that when ga mod p is a quadratic residue and gb mod p is a quadratic residue it will always be the case that gab mod p is a quadratic residue. Hence, a suitable setting for DDH is one in which breaking Diffie-Hellman is difficult and one in which the order of g is not divisible by any small primes. A survey on the Decision Diffie-Hellman problem was written by Dan Boneh [35].

B.4 Random Oracles and Functions

Random oracles are a theoretical tool used for proving the security of cryptosystems. It is a complete idealization of the functionality that some hash functions “seem” to provide on the surface. Informally, a random oracle R is a function that takes as input a single bit string s and that returns a countably infinite stream of randomly chosen bits. So, R(s) is an infinitely long bit string. For example, R(01001) = 010011010..., R(01000) = 101101110.... An important aspect of R is that all of its outputs are predetermined. That is, if R is given s as a query twice, R will respond with the same infinitely long bit string. Below is the formal definition of a random oracle.

Definition 8 A random oracle R is a function from {0, 1}* to {0, 1}∞ such that for a given query s to R, each and every output bit of R(s) is chosen uniformly at random and independent of every bit in s.

A random oracle cannot be implemented in practice. Yet, they are useful tools for arguing the security of a cryptosystem when the cryptosystem relies on a cryptographic hash function. The idea is to replace the hash function with a random oracle and then try to prove that the resulting algorithm is secure. It is then reasoned that any weaknesses that exist in the actual implementation must result from a weakness in the hash function that was used to instantiate the oracle, and not the cryptographic design [18].

In this book the term random function is used. A random function is the same as a random oracle except that the range is defined to be a finite set. It is possible to define a random function F from {0, 1}* to  using a random oracle R as follows. Suppose that N is k-bits long. A given element e

using a random oracle R as follows. Suppose that N is k-bits long. A given element e  {0, 1}* maps to an element in

{0, 1}* maps to an element in  as follows. Let m be the first k bits of the infinitely long string R(e). If m

as follows. Let m be the first k bits of the infinitely long string R(e). If m

then F(e) = m. Otherwise, consider the next k bits in R(e). If this quantity is contained in

then F(e) = m. Otherwise, consider the next k bits in R(e). If this quantity is contained in  then this quantity is F(e), and so on. It is easy to see that F(e) maps to an element drawn uniformly at random from

then this quantity is F(e), and so on. It is easy to see that F(e) maps to an element drawn uniformly at random from  .

.

1This theorem was proven independently by Hadamard and De La Valleé Poussin in 1898.

2This is the basis for the Solovay-Strassen probabilistic primality test [286].

3Formally, speaking it is a requirement for completeness of the underlying cryptographic protocol.

4That is, the ability for a user to construct queries and perform the private information retrieval.

5Generally speaking, a randomly chosen composite will be difficult to factor if it is large enough.