Chapter 5

Cryptocounters

A common trigger used in viruses to decide when to attack is a counter value. Such viruses typically do not trigger until it has propagated itself a certain minimum number of times. The Den Zuk virus contains such a trigger [289]. When counters are used only to measure the number of viruses in the wild, a good approach is to utilize two different generation counters. One counter would store the generation number of the virus that is incremented by one in each child a given virus has. This would provide the height h of the family tree. The other counter would be used to measure the average number of children that each virus has (see Chapter 1). This mechanism could be used as a tool for measuring replication performance of viruses in real-world infections.

However, antiviral analysts would likely benefit more than virus writers from the incorporation of counters in virus code since they would receive better population samplings. To solve this malware problem, a method is needed to implement such counters in a way that the viruses can increment the counters but that only the virus writer can read the actual counter values. A cryptocounter is a cryptographic primitive that solves this problem.

In this chapter a simple cryptocounter scheme is presented based on the ElGamal public key cryptosystem. Drawbacks to this approach are then given, followed by an improved approach based on the Paillier public key cryptosystem. The chapter concludes with discussion of even more ways to implement a cryptocounter.

5.1 Overview of Cryptocounters

Informally, a cryptocounter is a probabilistic public key encryption that encrypts a counter value that anyone can increment or decrement but that can only be decrypted using the appropriate private key. Put another way, it is a malleable ciphertext that allows the plaintext to have 1 added to it or 1 subtracted from it. The increment and decrement operations can be performed by anyone without even knowing the plaintext value and without first decrypting the encryption of the counter value.

The typical threat model for the operation of a cryptocounter is the honest-but-curious model. In this model, it is assumed that the machine that increments the cryptocounter does so properly, and does not change the counter in unexpected ways. For instance, if the algorithm normally increments the cryptocounter once every hour, the machine does not maliciously increment it twice every hour, and so on. It is assumed that the machine that operates on the cryptocounter ciphertext is passive and merely observes any and all computations regarding the counter. The machine may do its best to try to learn the counter value based on these observations, hence the term curious. In this sense the machine is a form of passive adversary. But, the machine does not interfere with the normal operation of the counter, which is a capability that active adversaries have.

By placing a cryptocounter within the virus, there is an added level of protection over the use of a plaintext counter. The counter value that the cryptocounter encrypts will never be revealed. This holds even if snapshots of the cryptocounter are taken on a regular basis. Such snapshots can occur as the result of coredumps and so forth. It is necessary to monitor the operations on the cryptocounter each step of the way in order to keep track of the current counter value.

Consider a virus that stores two cryptocounters to help keep track of the number of viruses in the wild. It is relatively safe to assume that before the virus is discovered, the host machine will not corrupt the counter value and will not interfere with the virus when it increments the counter. Also, it is prudent to assume that once the virus is found several system administrators may examine their logs to try to determine the counter values. Assuming that the snapshots are spaced out reasonably far enough, the snapshots are not likely to reveal the counter values that the viruses contain.

5.2 Implementing Cryptocounters

In this section two methods for implementing cryptocounters are given. This first is based on the ElGamal public key encryption algorithm. Although conceptually very simple, this approach has a significant drawback when counter values are large. The second approach is almost as simple as the first. It is a counter based on the Paillier public key cryptosystem. The Paillier cryptosystem is described and it is shown how to use Paillier to implement a simple cryptographic counter.

5.2.1 A Simple Counter Based on ElGamal

It is straightforward to utilize the ElGamal public key cryptosystem to implement a rudimentary cryptocounter. In the semantically secure version of ElGamal (see Appendix C.2.2) the message space consists of all messages m such that mq = 1 mod p. Here q is a large prime that divides p − 1 evenly. Since the cryptosystem is malleable under multiplication modulo p, the plaintext can be multiplied by values modulo p without ruining the decipherability of the ciphertext. So, a simple counter can be implemented using the public key (y, g, p) as follows.

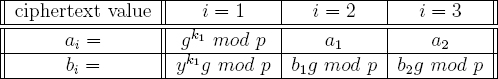

The plaintext is initially set to g1 = g. By choosing k1 randomly, the first counter value is computed to be the pair (a1, b1) that is equal to (gk1 mod p, yk1 g mod p). To increment the counter by 1, the ciphertext (a2, b2) can be computed by setting (a2, b2) = (a1, b1 g mod p). Similarly, (a3, b3) = (a2, b2 g mod p). When this ciphertext is decrypted, the plaintext is found to be g3 mod p. This is illustrated in Table 5.1.

However, there is a problem with this approach since it paves the way for correlation attacks against the virus. For example, consider a generation counter that is incremented by one in each child. Suppose that a virus on machine A has a child on machine B and that this virus has a child on machine C. The ciphertexts on A, B, C would be (a1, b1), (a2, b2), (a3, b3), respectively. Observe that the equalities a1 = a2 = a3 hold. The problem is that b3/g = b2 mod p and b2/g = b1 mod p. So, the path of the virus can be ascertained based on the relationships between b1, b2, and b3.

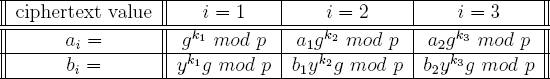

This problem can be solved by rerandomizing the ciphertexts each time the counter is incremented. This makes correlation impossible due to the semantic security of the underlying cryptosystem. This approach will now be described. The plaintext is initially set to g1 = g. By choosing k1 randomly, the first counter value is computed to be (a1, b1) = (gk1 mod p, yk1 g mod p). To increment the counter by 1, the ciphertext (a2, b2) is computed by choosing k2 < q randomly and setting (a2, b2) = (a1 gk2 mod p, b1yk2 g mod p). When this ciphertext is decrypted, the plaintext is found to be g2 mod p. To see that this works, note that  = g2 mod p. To increment the counter again, the ciphertext (a3, b3) = (a2gk3 mod p, b2yk3g mod p) is computed using a randomly chosen value k3 < q, and so on. This is illustrated in Table 5.2. This method stores the actual counter value in the exponent of g. The counter value i therefore corresponds to the ElGamal plaintext gi mod p.

= g2 mod p. To increment the counter again, the ciphertext (a3, b3) = (a2gk3 mod p, b2yk3g mod p) is computed using a randomly chosen value k3 < q, and so on. This is illustrated in Table 5.2. This method stores the actual counter value in the exponent of g. The counter value i therefore corresponds to the ElGamal plaintext gi mod p.

Table 5.1 Flawed ElGamal Cryptocounter

Suppose that the cryptocounter ciphertext (ai, bi) is obtained from a virus. By performing ElGamal decryption the plaintext m = bi/axi mod p is found. Since m = gi mod p, computing i is equivalent to computing the base g discrete logarithm of m. Provided that i is not exponentially large, this can be done by testing whether or not gi = m mod p for i = 1, 2, 3,... until the equality holds.

5.2.2 Drawback to the ElGamal Solution

The drawback to this counter is that there is no trapdoor for the counter value. The value for i must be found by brute-force after gi mod p is computed via decryption. Consider an application in which the counter value is not always incremented by one. If at some point the counter is incremented by an exponentially large value, it will take exponential time to determine the exact counter value during decryption. When used for implementing virus generation counters this drawback may not be very significant, but in other applications it may well be. Cryptographic counters like this one can be used in a variety of ways. They are ideal mechanisms for securely gathering statistics on untrustworthy host machines and are general tools for securing mobile agents.

Table 5.2 ElGamal Cryptocounter

5.2.3 Cryptocounter Based on Squaring

The ElGamal cryptocounter is trivial to decrement by anyone. To decrement (ai, bi) one need only compute (ai, big−1 mod p) and then rerandomize the new pair. This drawback can be heuristically avoided using the following variation of the counter. It is very similar to the ElGamal cryptocounter in terms of choosing exponents randomly, rerandomizing, decrypting the counter, etc. However, instead of using the prime p, the modulus n is used where n is the product of two secret primes. The value g

is chosen such that it has order

is chosen such that it has order  (n)/2. Hence, g is a quadratic residue modulo n.

(n)/2. Hence, g is a quadratic residue modulo n.

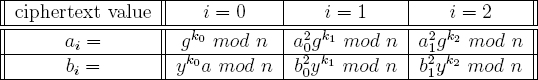

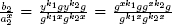

The counter value 0 is represented by a randomly chosen quadratic residue a modulo n that is kept secret. To increment the counter by 1, both ai and bi are squared modulo n. Thus a2 corresponds to a counter value of 1, a4 mod n corresponds to a counter value of 2, and so on (see Table 5.3).

Just as in the ElGamal cryptocounter there is no trapdoor here. To determine the counter value the pair (ai, bi) is decrypted using x and the resulting plaintext is a2i mod n. The counter value is i and this can be found by brute force. A brute force approach is to start with a, square it repeatedly and stop when a value is found that matches the plaintext of (ai, bi).

Consider the problem of decrementing the counter without a and without knowing the factorization of n. This can be trivially accomplished by reverting to a previously stored cryptocounter pair if one is available. If no previous snapshots of the cryptocounter are available, then the counter value can be modified by setting bi = biw mod n where w is a quadratic residue modulo n. However, this modification is not likely to be meaningful since a is kept secret.1 Decrementing a cryptocounter pair directly without any previous copies amounts to computing a square root of ai and a square root of bi modulo n, which is intractable.

Table 5.3 Squaring Cryptocounter

5.2.4 The Paillier Encryption Algorithm

Perhaps one of the simplest and most elegant solutions to the problem of implementing a cryptocounter is to use Paillier's public key cryptosystem [216]. The Paillier cryptosystem constitutes a one-way trapdoor under the computational composite residuosity assumption (see Appendix B.3.3). The Paillier cryptosystem is semantically secure against plaintext attacks under the decision composite residuosity (DCR) problem (see Appendix B.3.4).

The value n in Paillier is the product of two large primes p and q, the same as in RSA. The Paillier cryptosystem is based on the following two properties of Carmichael's  function.

function.

- For any w contained in

, the congruence w

, the congruence w (n) ≡ 1 mod n holds.

(n) ≡ 1 mod n holds. - For any w contained in

, the congruence wn

, the congruence wn (n) ≡ 1 mod n2 holds.

(n) ≡ 1 mod n2 holds.

In RSA the public exponent e in the public key (e, n) is relatively prime to (p − 1)(q − 1). Typically, the value e is shared by all the users. Paillier's cryptosystem is quite a bit different since it does not employ e. Instead, the cryptosystem utilizes an integer g that has order v modulo n2 with v satisfying the following congruence.2

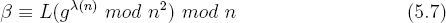

The value g is shared by all the users. The public key is (n, g) and the private key is  (n).

(n).

The following is how to encrypt a message m, which is an integer satisfying m < n. A value u is chosen uniformly at random from  and the ciphertext c is computed as follows,

and the ciphertext c is computed as follows,

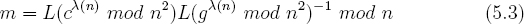

The function L(x) =  is used for decryption. The following equation shows how to decrypt c to recover m.

is used for decryption. The following equation shows how to decrypt c to recover m.

It remains to show that decryption succeeds for all messages m. By Euclid's division rule, given positive integers g (n) and n2 with n2 ≠ 0, there exist unique integers q and r, with 0 ≤ r < n2 such that g

(n) and n2 with n2 ≠ 0, there exist unique integers q and r, with 0 ≤ r < n2 such that g (n) = qn2 + r. In this equation q is the quotient and r is the remainder upon dividing g

(n) = qn2 + r. In this equation q is the quotient and r is the remainder upon dividing g (n) by n2. The value r equals g

(n) by n2. The value r equals g (n) mod n2. By reducing both sides modulo n this implies that,

(n) mod n2. By reducing both sides modulo n this implies that,

By property (1),

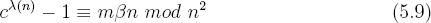

By transitivity, equations 5.4 and 5.5 imply that r ≡ 1 mod n. Hence, g (n) mod n2 is congruent to 1 modulo n. So, there exists an integer β < n such that g

(n) mod n2 is congruent to 1 modulo n. So, there exists an integer β < n such that g (n) mod n2 = 1 + βn. Hence,

(n) mod n2 = 1 + βn. Hence,

By subtracting 1 from both sides it follows that g (n) − 1 ≡ βn mod n2. This implies that g

(n) − 1 ≡ βn mod n2. This implies that g (n) − 1 mod n2 = βn mod n2. Define t1 to be g

(n) − 1 mod n2 = βn mod n2. Define t1 to be g (n) − 1 mod n2. So, t1 = βn mod n2. By applying the division rule again, it follows that there exists a k1 such that βn = k1n2+t1. So, t1/n = β − k1n. By reducing both sides modulo n, it follows that t1/n ≡ β mod n. Since t1/n = L(g

(n) − 1 mod n2. So, t1 = βn mod n2. By applying the division rule again, it follows that there exists a k1 such that βn = k1n2+t1. So, t1/n = β − k1n. By reducing both sides modulo n, it follows that t1/n ≡ β mod n. Since t1/n = L(g (n) mod n2) this implies that

(n) mod n2) this implies that

By raising both sides of equation 5.2 by  (n) and reducing modulo n2 it follows that c

(n) and reducing modulo n2 it follows that c (n) ≡ (gm un)

(n) ≡ (gm un) (n) mod n2. From property (2), the value un

(n) mod n2. From property (2), the value un (n) = 1 mod n2. Hence,

(n) = 1 mod n2. Hence,

Now, by substituting equation 5.6 for g (n) in equation 5.8 it follows that c

(n) in equation 5.8 it follows that c (n) ≡ (1 + βn)m mod n2. The Binomial Theorem describes the expansion of the binomial (1 + βn) on the right side of this equation. But, since this equation is reduced modulo n2, every term will be zero except for the first two terms of the expansion. As a result, c

(n) ≡ (1 + βn)m mod n2. The Binomial Theorem describes the expansion of the binomial (1 + βn) on the right side of this equation. But, since this equation is reduced modulo n2, every term will be zero except for the first two terms of the expansion. As a result, c (n) = 1 + mβn mod n2. So,

(n) = 1 + mβn mod n2. So,

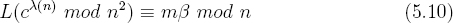

But this implies that c (n) − 1 mod n2 = mβn mod n2. Define t2 to be c

(n) − 1 mod n2 = mβn mod n2. Define t2 to be c (n) − 1 mod n2. By the division rule, there exists a k2 such that mβn = k2n2 + t2. Hence, t2/n = mβ − k2n. By reducing both sides modulo n it follows that t2/n = mβ mod n. Since t2/n = L(c

(n) − 1 mod n2. By the division rule, there exists a k2 such that mβn = k2n2 + t2. Hence, t2/n = mβ − k2n. By reducing both sides modulo n it follows that t2/n = mβ mod n. Since t2/n = L(c (n) mod n2) this implies that,

(n) mod n2) this implies that,

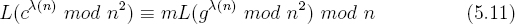

By substituting equation 5.7 for β in equation 5.10 it follows that,

Multiplying both sides by L(g (n) mod n2)−1 mod n results in the plaintext m.

(n) mod n2)−1 mod n results in the plaintext m.

Since the quantity L(g (n) mod n2)−1 mod n is always the same each time that a ciphertext c is decrypted, this value can be computed once and for all. So, let ψ = L(g

(n) mod n2)−1 mod n is always the same each time that a ciphertext c is decrypted, this value can be computed once and for all. So, let ψ = L(g (n) mod n2)−1 mod n. The user can then store (

(n) mod n2)−1 mod n. The user can then store ( (n),ψ) as his or her private key. Equation 5.12 shows how to decrypt c using ψ.

(n),ψ) as his or her private key. Equation 5.12 shows how to decrypt c using ψ.

As in RSA, the Chinese Remainder Theorem can be used to speed up decryption. A variant of Paillier's scheme has been proposed that makes some efficiency improvements regarding the size of Paillier ciphertexts [79].

5.2.5 A Simple Counter Based on Paillier

The way to utilize this cryptosystem as a cryptocounter is straightforward. The counter is initially set to m =1. To encrypt this counter value, u1 is chosen randomly and the ciphertext is computed to be c1 = g1un1 mod n2. To increment the counter by one, u2 is chosen randomly and the value c2 = c1gun2 mod n2 is computed. In general, ci = ci−1guni mod n2. This rerandomization guarantees that each counter value is encrypted in a semantically secure fashion.

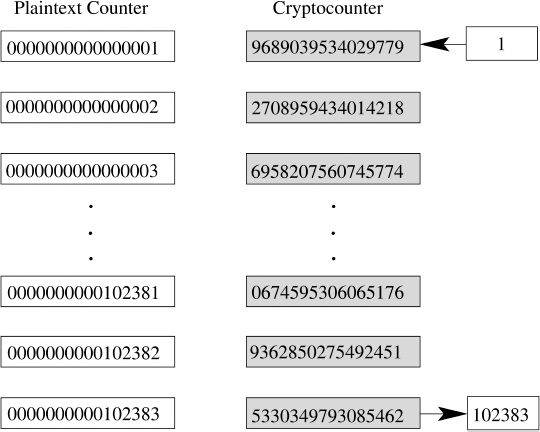

The benefit of this approach as opposed to the ElGamal solution is that no comparisons are necessary when ci is decrypted. The value i is found immediately. A depiction of what a cryptocounter looks like when viewed on an untrusted machine is given on the right side of Figure 5.1.

5.3 Other Approaches to Cryptocounters

The Paillier cryptocounter is efficient in the sense that the counter value can be computed in poly-time even if the counter value is exponentially large. The Paillier cryptosystem constitutes an additive homomorphism under multiplication modulo n2 since the product of two ciphertexts yields a ciphertext containing a plaintext that is the sum of the two original plaintexts. A cryptocounter was proposed by Katz et al that does not rely on this property [152]. Their construction shows how to implement a cryptocounter given any encryption scheme that is homomorphic over the additive group  2. As a result, cryptocounters can be constructed based on the quadratic residuosity assumption.

2. As a result, cryptocounters can be constructed based on the quadratic residuosity assumption.

Figure 5.1 Plaintext counter vs. cryptocounter

In summary, cryptocounters can be implemented based on the Decision Diffie-Hellman problem, the problem of distinguishing nth residues modulo n2, and the composite quadratic residuosity problem. So, if the Decision Diffie-Hellman problem is found to be tractable, for example, then one of the other settings might still provide a secure foundation for this primitive. It is also quite possible that cryptocounters can be synthesized based on other intractability assumptions as well.

1In fact, by using two different counter constructs such as this one and the ElGamal one at the same time, by making the counter values equivalent, and by incrementing them in lock-step, a redundancy check is implemented. The check is verified by decrypting the cryptocounters and making sure they both store the same count. This makes it harder for an active adversary to falsify a previous counter value.

2The value g is said to have order v modulo n2 if and only if v is the smallest positive integer satisfying gv = 1 mod n2.