Chapter 9

The Nature of Trojan Horses

Up until this point the book has focused largely on self-replicating programs. The exception to this is the deniable password-snatching attack described in Section 4.2 that is carried out by a Trojan horse program. The remainder of the book focuses exclusively on Trojan horse programs.

The term Trojan horse is a fitting one for describing malicious software and is based on a Greek myth. According to legend, the Greeks were unable to penetrate the city of Troy using siege machines and other weapons of war. So, they devised a plan. They built a huge wooden horse with a hollow belly and filled it with Greek warriors that were poised for attack. The Greeks pushed the horse to the outskirts of Troy and then sailed away. The Trojans assumed that it was a peace offering and brought the horse inside the city to celebrate the presumed departure of the Achaeans. The citizens rejoiced and drank heavily throughout the evening and much of the night. The Greek warriors took the city by surprise under cover of dark.

Computer Trojan horses are much the same. They are invisible to the naked eye. They appear within otherwise attractive or harmless programs. They require some form of user or operating system intervention to activate, and they do something that the user does not expect. The purpose of this chapter is to convey a basic principle that underlies the design of Trojan horse programs, the principle being that Trojans are designed to exploit resources and access permissions that are inherent in their hosts. By virtue of being one with the host program the Trojan inherits these resources and access permissions and exploits this to achieve its goal. In the case of password snatchers the goal is to securely and subliminally leak login/password pairs to the Trojan author. In the case of kleptographic attacks the goal is to securely and subliminally leak private keys to the attacker, and so on.

To further illustrate this principle, key questions that attackers ask themselves are addressed. Such questions are along the lines of, “If I could place a Trojan in program X, how could I program it to exploit the system?” It was this sort of thinking that led to the kleptographic attacks in the chapters that follow.

9.1 Text Editor Trojan Horse

Consider a multiuser operating system that has an installed text editor that is free for use. Users can run the text editor, create and modify text, and save their files to disk. However, suppose further that this program can be executed but not modified or deleted by the users, as in typical multiuser operating systems such as UNIX.

This program has certain unique privileges. It has read access to every text file that users create or open for editing. As such it is an ideal target for a Trojan horse program that is geared towards stealing the private data of others. When a Trojan is installed in this program it can store data from one user and make the data available to the Trojan horse author. It could have devastating effects if, for example, top secret data were leaked to someone that had only secret clearance or lower. This type of attack was described in the visionary Anderson report of 1972 [6].

9.2 Salami Slicing Attacks

In November of 1987 an article was published in the Globe and Mail that described a talk given by Sergeant Ted Green, an officer of the Ontario Provincial Police.1 The talk described several logic bomb attacks and other attacks against systems. One of them was a Trojan horse attack that was clearly intended to achieve financial gain. The attack was carried out by an employee of a bank who managed to accumulate $70,000 by funneling a few cents out of every account into his own [179, 205]. This type of attack is called a salami slicing attack [219] since small portions of money are purloined from numerous accounts. This is necessary to prevent employees from noticing that their paychecks are a bit less than they should be. Many assets or resources can be salami sliced. For instance, CPU use can also be salami sliced. This allows malware to steal CPU time in small increments to solve computational problems in an inconspicuous fashion.

The resource that the bank Trojan has access to is money and the Trojan steals the money. The resource that the text editor has access to is the documents of many users and the Trojan steals the documents. The cryptotrojans described in Chapters 11 and 12 are inserted into cryptosystems that have access to private keys which are also stolen. All of these Trojans exploit the access privileges of their hosts and steal the assets that they have access to. So, the methodology for designing a Trojan is simple: decide what sort of asset is desired, determine which programs have access to it, and then carefully design a Trojan to secure the asset. However, actually getting the Trojan into position is a different story. This can easily be done by an insider, whereas outsiders often have to exploit bugs in the system to gain entry.

9.3 Thompson's Password Snatcher

Stealing login/password pairs is the bread and butter of every hacker's existence. Once a system is infiltrated, password-snatching programs are often surreptitiously installed. Such programs are often referred to as rootkits [132]. They are installed to ensure that access to the machine continues to be possible, even if a few accounts are terminated due to suspicious activity. Such programs have been written as DOS terminate and stay resident (TSR) programs that record all keystrokes entered via the keyboard. These programs typically patch the operating system hardware interrupt for key presses and log the key presses to a hidden file. Technically speaking, such a stand-alone program is not a Trojan horse per se since it is not directly attached to a host.

The addition of a stand-alone TSR program to a file system may be a noticeable act of espionage. For example, if the TSR program is stored in a directory of programs that are always run at boot time then its presence may be revealed. A more desirable approach from the attacker's perspective is to integrate the password-snatching code into an existing operating system program in an unnoticeable fashion.

A suitable host for a password-snatching Trojan is any program that has access to the passwords of users. A perfect example of this is the UNIX passwd program. The passwd program is the UNIX program that is responsible for verifying the identity of UNIX users by obtaining and verifying login/password pairs. There are two obvious approaches to mounting a Trojan horse attack against such a program. The first is to manually attach one by copying the Trojan to the end of the passwd program and altering the entry point and exit points appropriately. Another option, assuming that root access is possible, is to modify the source code for the password program, recompile it, and install the compromised version. It may be argued that this form of attack is the epitome of a Trojan horse attack.

Even this approach suffers from an obvious drawback. What if the source code for the passwd program is updated and the system administrator compiles a new version of it? If the system administrator installed the new version, the old one would be deleted and the attack would be foiled due to the system update. The use of a UNIX compiler therefore threatens the perpetuation of the Trojan horse attack. It would make sense, then, to install a Trojan horse program into the compiler so that whenever it is given the source to the passwd program it secretly inserts the password-snatching code. This will clearly increase the survivability of the attack.

But what if the compiler is recompiled? It is common practice to both add functionality and fix non-fatal flaws in a compiler by having it compile the revised version of itself. If such a compromised compiler is recompiled the code that secretly inserts the Trojan into the passwd program would be lost.

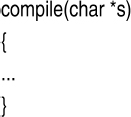

Ken Thompson described a somewhat involved Trojan horse attack that solves this program elegantly [300]. The idea is as follows. A normal compiler parses a source file, checks its syntax, and produces object code. This standard compiler behavior is indicated by the ellipsis in Figure 9.1.

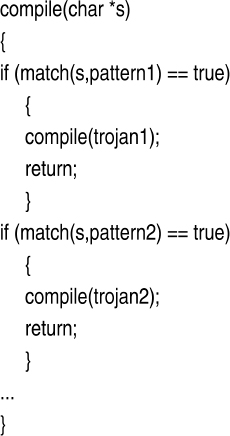

The parameter s is a pointer to a string that contains the source code. The idea is to insert a source level Trojan horse into the source code of the compiler that checks for two patterns in the string s. The first pattern is source code corresponding to the password verification program (e.g., passwd). When this pattern is found the password-snatching source code is secretly added to the program just before it is compiled. The Trojan is, of course, not saved to the source file of the password program. The second pattern is source code corresponding to the compiler. When this pattern is found the entire compiler Trojan is secretly included in the compiler source code just before it is compiled. This code, of course, contains all of the source code for the password-snatching Trojan. This is indicated by the two “if” statements in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.1 Normal compiler (ANSI C notation)

This Trojan is somewhat virus-like since it copies itself in its entirety into the source file for the compiler whenever the compiler is compiled. It could be added to the source for the compiler, the compiler could be recompiled, and the old compiler could be replaced with the new. This would remove all traces of the source code for the Trojan horse attack. The Trojan would remain in binary form, seamlessly integrated with the rest of the compiled instructions.

The moral of the story is that one cannot ascertain the honesty of the code that is being created even if the source code is analyzed before compilation. To be certain that no slight of hand is being performed it is necessary to analyze the binary code of the compiler. Even this is not enough, for the microprocessor itself can execute a covert series of instructions at any time, based on a previously executed sequence of opcodes or otherwise. Thompson's Trojan horse attack exploits the unique capabilities of its host:

- It exploits the fact that compilers are used to make programs, including the passwd program and the compiler itself.

- It exploits the fact that the passwd program has unadulterated access to login/password pairs. By transitivity the compiler has access to login/password pairs as well (in some sense).

It is only natural to ask what other Trojan horses can be concocted based on host programs with unique capabilities and responsibilities. It was this very question that drove the research behind kleptography: A key generation program has access to private keys, a public key decryption program has access to private decryption keys, a digital signature program has access to private signing keys. What types of Trojan horses can be attached to these programs that exploit the fact that they have access to private keys? This very question is addressed in the chapters that follow.

Figure 9.2 Compiler with Trojan (ANSI C notation)

9.4 The Subtle Nature of Trojan Horses

It is difficult at best to come up with a formal definition of a Trojan horse program. Whether or not a given program is a Trojan horse can depend completely on the perspective of the user that encounters it. Take the reboot monitoring Trojan described in Chapter 1, for instance. This Trojan could not be simpler in design. It is installed in a highly concealed manner. The host of the Trojan is a program that is found on virtually everyone's machine2 and that gains control when the system boots. It increments a counter by 1 each time the machine is rebooted and stores the counter in variable in RAM and on the disk.

The Trojan is a very simple form of spyware that solves a problem facing any hacker. For example, suppose that a hacker has a gigabyte of data that can be used as evidence against the hacker. The data should obviously remain encrypted almost all the time. When the hacker leaves his or her machine for a period of time, the hacker wants to make sure that a law enforcement agent does not install a monitor on the machine.3 Such a monitor could be used to log all of the hacker's personal passwords, and so on. So, the Trojan is used by the hacker to booby trap the machine. The hacker simply notes the counter value, turns off the machine, and then leaves. Upon returning, the hacker turns on the machine (it had better still be off!) and takes note of the counter value. If the machine had been turned on in the interim, the hacker would likely know. The hacker's program needs to be hidden since if the law enforcement agent finds it, the counter value could be adjusted to make it look as if the machine hadn't been used by anyone.

Is this rogue program a Trojan? Certainly not from the perspective of the hacker since the hacker knows what it is about. It is clearly a Trojan from the perspective of the law enforcement agent since the agent doesn't know that it is there. Given the fact that the program is designed to be hard to find and does something that someone doesn't expect, it seems natural that it should be classified as a Trojan. This makes it rather interesting, since it is a purely beneficial Trojan from the perspective of the hacker.

Also, there is a fine line between what constitutes a Trojan horse attack and what constitutes an honest programming mistake. In the subsections below two examples of Trojans are given that illustrate this fine line. They have the property that even when they are analyzed by skilled programmers it may not be clear whether or not they are Trojans at all. The first such example is a Trojan that is nothing more than a bug. However, this bug is bad enough that when planted properly it allows that Trojan author to break into the computer system. The second Trojan horse is a purely mathematic one. The Trojan affects the statistical distribution of the output of a random number generator in a way that makes the generator extremely sensitive to the input entropy. So, when the Trojan is given correct inputs it does nothing to harm the output of the random number generator. However, when the Trojan is given poor inputs, the Trojan adversely affects the outputs of the random number generator.

9.4.1 Bugs May In Fact Be Trojans

As early as 1978 Farber and Popek described an address wraparound vulnerability in the PDP-10 TENEX system [230]. Under the right conditions, a user could force the program counter to overflow while executing a supervisor call. This resulted in a privileged-mode bit in the word corresponding to the state of the process to be activated, thereby causing control to return to the user's program in supervisor mode.

If a user forced this condition by accident, then it would constitute a bug. However, if the user forced this condition on purpose so that it could later be exploited, then it would constitute a Trojan horse. This illustrates the fine line between bugs and Trojan horse programs.

9.4.2 RNG Biasing Trojan Horse

The following is a Trojan horse that attacks random number generators. The Trojan horse is effectively a digital filter that accepts as input “random” bits and outputs “random” bits. Such filters are often used to remove any existing biases in the distribution over the input bits, as in the case of John von Neumann's method for unbiasing a biased coin. However, this filter is somewhat the opposite in purpose. Rather than eliminating any existing bias, this filter exacerbates any existing bias. However, if there is no bias to begin with then there will not be any bias in the output values.

The algorithm is given below. It takes as input three bits b1, b2, b3. It outputs a single bit B. By supplying it with an endless stream of input bits it will produce an endless stream of output bits. It is assumed that each bit bi is produced with a fixed bias for all i.

BiasExacerbator(b1, b2, b3):

1. B = 0

2. if b1b2b3 = 111 or 110 or 101 or 011 then B = 1

3. output B and halt

For example, the stream of bits bi may be produced by a loaded coin that produces heads with probability 51 percent. Let the probability of heads be denoted by ph = 1/2 + δ. If δ = 0 then the coin is fair. If δ > 0 then heads is more likely than tails. If δ < 0 then tails is more likely than heads.

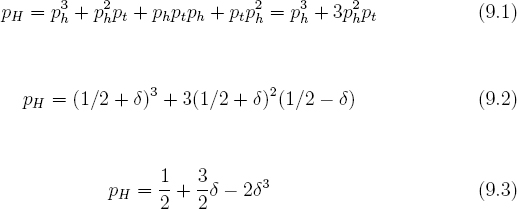

Let the probability of tails be denoted by pt. Hence, pt = 1 − ph. The probability that BiasExacerbator outputs B = 1, denoted by pH is given below.

From equation 9.3 it is clear that when δ = 0 the value pH = 1/2. Hence, if the input bits are not biased then the output bits will not be biased. As a sanity check note that if δ = 1/2 then the value pH = 1. This is what one would expect when this function is given bi = 1 for all i.

The interesting issue is to determine under what circumstances this digital filter messes with the input distribution. Suppose that δ > 0. It will amplify the input bias towards heads whenever the following inequality holds.

This simplifies to the following inequality,

To solve the above inequality for δ we may take the square root of both sides. The value δ2 has two square roots, namely δ and −δ and 1/4 has the two square roots 1/2 and −1/2. Since it was assumed that δ > 0 it follows that amplification towards heads will occur whenever 0 < δ < 1/2. No amplification occurs when δ = 0, 1/2. If δ < 0 it can be shown that the bias will increase towards tails whenever −1/2 < δ < 0.

The interesting aspect of this filter is that it amplifies the bias in the direction that the bias is already in. For example, if the initial bias is towards heads, then the output bias is even more towards heads. If the input bias is towards tails, then the output bias will be even more towards tails.

This filter may be aptly dubbed a Trojan horse if it is appended to a random number generator. Mathematically speaking, it is totally benign when the input bits are unbiased. But, when the input bits are biased this Trojan makes the bias even worse. A natural question to ask is how to design finite automata to detect such a Trojan and label it as malicious. Such a program would have to somehow “understand” that the mathematics behind the algorithm makes the underlying software “less stable.”

To summarize, the fact that an address wraparound vulnerability can constitute a Trojan horse is really a matter of semantics. As illustrated by the RNG biasing Trojan, whether or not a program constitutes a Trojan can also be a matter of pure mathematics.