Chapter 12

SETUP Attacks on Discrete-Log Cryptosystems

Existing cryptosystems based on the discrete logarithm problem are in no way immune to the threat of kleptographic attacks. This chapter expands upon the previous chapter by showing how to mount SETUP attacks on such cryptosystems. The notion of a discrete-log kleptogram is introduced that allows the attacker to obtain secret information covertly from fielded cryptosystems. What is novel about this approach is that it implements SETUP attacks without using explicit subliminal channels. Rather than employing information leaking channels, the implementation uses internal cryptographic tools to generate opportunities to leak information. As before, the approach avoids trivial attacks on the pseudorandomness of the device and similar simple attacks that would enable a successful reverse engineer to learn future states of the device.

The approach employs the discrete logarithm as a one-way function thereby assuring forward secrecy. The discrete-log kleptogram primitive is then used to attack the Diffie-Hellman key exchange [92]. The attack gives the attacker access to the shared secret key that is generated in the exchange. The primitive is then applied to discrete-log based public key encryption algorithms. It is shown how this gives the attacker access to plaintext. Finally, it is shown how to apply the primitive to discrete-log based signature algorithms to enable the attacker to gain access to signing private keys.

Some of the attacks presented in this chapter on discrete-log based signature algorithms are new and build on previous work [336, 339]. The proof of security for the Diffie-Hellman key exchange SETUP attack is sketched out and the approach is based on [341]. The attack is secure in the random oracle model. Attacks are given for other discrete-log based cryptosystems as well, but no formal proof of security is given for them.

12.1 The Discrete-Log SETUP Primitive

A kleptogram is a publicly displayed value such as a ciphertext, signature, public key, and so on, that also serves as a backdoor. In the SETUP attack on the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, the device computes a kleptogram, displays it in one key exchange, and then uses the concealed value to securely compromise the next key exchange. This concealed value is used to derive the randomness in the subsequent key exchange.

Let p denote a large prime and let g be an element in  with order w. Let G denote the subgroup of

with order w. Let G denote the subgroup of  generated by g. It is assumed that solving Diffie-Hellman in G is difficult. So, w must contain a large prime in its factorization to defend against the use of the Pohlig-Hellman algorithm [224].

generated by g. It is assumed that solving Diffie-Hellman in G is difficult. So, w must contain a large prime in its factorization to defend against the use of the Pohlig-Hellman algorithm [224].

In the kleptographic attack, the honest device outputs exponents for g that are chosen honestly. The dishonest device contains an analogous subroutine that outputs exponents for g that are securely compromised by the attacker.1 These may be used as private exponents in a cryptosystem defined over G to provide the attacker with a backdoor. The following is the exponent generation algorithm used by the honest device.

GenPrivateExponent1(K):

input: a value K that is the empty string or a value contained in

output: an element k contained in

1. choose k to be random element in

2. output k and halt

Observe that GenPrivateExponent1 patently ignores the input K. Let |w| denote the number of bits used in representing w in binary. Assuming that GenPrivateExponent1 has access to a true random bit generator, it can be implemented as follows. Exactly |w| bits are generated randomly. If the value is not contained in  then these bits are thrown out and a new set of |w| bits are generated. If this value is not contained in

then these bits are thrown out and a new set of |w| bits are generated. If this value is not contained in  , then it is thrown out and |w| more bits are generated, and so on. This process guarantees that k is chosen from the correct probability distribution. It is possible to set x = k, use x as a private key, and set y = gx mod p. The public key is then (y, g, p).

, then it is thrown out and |w| more bits are generated, and so on. This process guarantees that k is chosen from the correct probability distribution. It is possible to set x = k, use x as a private key, and set y = gx mod p. The public key is then (y, g, p).

Let X be a value contained in  and let Y = gX mod p. The value X is the private key of the attacker. The public key of the attacker is (Y, g, p). The algorithm GenPrivateExponent2 is used by a dishonest device that contains a |p|-bit identifier ID. The IDs for the devices are chosen randomly, subject to the constraint that they all be unique. It is anticipated that a device may eventually get reverse engineered, in which case Y will become known to the reverse engineer in addition to the randomly chosen ID in it. The device may or may not be destroyed during reverse engineering.

and let Y = gX mod p. The value X is the private key of the attacker. The public key of the attacker is (Y, g, p). The algorithm GenPrivateExponent2 is used by a dishonest device that contains a |p|-bit identifier ID. The IDs for the devices are chosen randomly, subject to the constraint that they all be unique. It is anticipated that a device may eventually get reverse engineered, in which case Y will become known to the reverse engineer in addition to the randomly chosen ID in it. The device may or may not be destroyed during reverse engineering.

It is assumed that each device has a readable and writable memory capability. This non-volatile memory is used by the attacker to maintain a count i of how many times the attack has been carried out. The value for i is initially set to 0. Let F1 be a random function with range  (see Appendix B.4). The function F1 can be implemented in practice using a suitable cryptographic hash function.

(see Appendix B.4). The function F1 can be implemented in practice using a suitable cryptographic hash function.

GenPrivateExponent2(K):

input: a value K that is the empty string or a value contained in

output: an element k contained in

1. if i > Θ then output GenPrivateExponent1(K) and halt

2. update i in non-volatile memory to be i = i + 1

3. compute t = YK mod p

4. let T0 be the |p|-bit representation of t

5. compute k = F1(T0||ID||i)

6. output k, zeroize everything in memory except i, and halt

The constant Θ is polynomial in |p| and is used to eventually cease the attack. The reason this is done is to simplify the proof of security. The primitive is applied as follows. The device is supplied with a value T = gK mod p. As will become clear in the specific attacks that are presented, T will correspond to a Diffie-Hellman key exchange value, a public key, a portion of a digital signature, and so on. When the device is invoked the value k = GenPrivateExponent2(K) is computed. In the attacks that are presented, k will correspond to a Diffie-Hellman exponent, a nonce in a digital signature algorithm, and so on. The device outputs gk mod p in one form or another and possibly other information as well. The goal of the reverse engineer is to obtain k from a given device based on what was learned from previous reverse engineering efforts and all other available information.

When the primitive is deployed, that attacker has a unique advantage. If the attacker obtains T, the attacker can compute t = TX = YK mod p and then pad t to obtain T0. Since the attacker was the one that selected all of the IDs, the attacker is in a position to compute k = F1(T0||ID||i) since i ≤ Θ can be readily guessed. It is this unique advantage that forms the basis for the optimal-bandwidth attacks. In essence, a key exchange is being performed between the attacker and the device each time that the device is invoked. The shared secret is used to secretly convey a random nonce k to the attacker. The use of the oracle and ID guarantees that the user cannot distinguish the view of the honest device from the view of the attacked device, even if Y, ID, i, and so on are obtained through reverse engineering.

12.2 Diffie-Hellman SETUP Attack

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange (see Appendix C.1.2) exhibits a discrete log kleptogram that can be exploited to give an insider (e.g., the manufacturer) an advantage. Consider the event that Alice and Bob perform two separate key exchanges. In the first round Alice sends Bob A1 = ga1 mod p and Bob sends Alice B1 = gb1 mod p. In the second round Alice sends Bob A2 = ga2 mod p and Bob sends Alice B2 = gb2 mod p. The two shared secrets are ga1b1 mod p and ga2b2 mod p, respectively.

In this attack, Alice's device is dishonest and mounts the SETUP attack.2 So it is the one using GenPrivateExponent2. Bob's device C is honest and uses GenPrivateExponent1. The attacker can utilize the backdoor provided that one or both of the devices mount the SETUP attack. To be conservative, it is assumed that Alice's device outputs (ai, gai mod p) to Alice. This allows her to verify its computations by checking that g raised to the first value equals the second. Of course, she must keep all of the values for ai secret. In the ith key exchange, the device will store ai and await Bi. When the device is given Bi it outputs Biai mod p. The goal of the attacker is to learn the Diffie-Hellman value ga2b2 mod p.

Alice's device chooses a1 randomly from  and outputs the pair of values (a1, ga1 mod p) to Alice. It stores a1 in non-volatile memory. Alice supplies the device with B1. The device then computes B1a1 mod p and outputs this value to Alice. At this point an honest device would erase a1, but Alice's device does not. Instead, it stores a1 in non-volatile memory until the subsequent key exchange. When the next exchange is initiated, Alice's device does not choose a2 randomly using a random bit generator. Instead, it computes a2 = GenPrivateExponent2(a1). The device outputs (a2, ga2 mod p) to Alice. The value B2 is then supplied to the device by Alice, at which point it outputs B2a2 mod p to Alice. Observe that Alice is essentially letting the device choose all the randomness for her. If she were suspicious, she could take the outputs of the device and compute the Diffie-Hellman secrets herself.3

and outputs the pair of values (a1, ga1 mod p) to Alice. It stores a1 in non-volatile memory. Alice supplies the device with B1. The device then computes B1a1 mod p and outputs this value to Alice. At this point an honest device would erase a1, but Alice's device does not. Instead, it stores a1 in non-volatile memory until the subsequent key exchange. When the next exchange is initiated, Alice's device does not choose a2 randomly using a random bit generator. Instead, it computes a2 = GenPrivateExponent2(a1). The device outputs (a2, ga2 mod p) to Alice. The value B2 is then supplied to the device by Alice, at which point it outputs B2a2 mod p to Alice. Observe that Alice is essentially letting the device choose all the randomness for her. If she were suspicious, she could take the outputs of the device and compute the Diffie-Hellman secrets herself.3

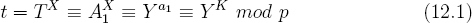

Alice is in big trouble. She is in trouble because the attacker who is carrying out the attack on Alice, namely, the insider who created her device (or altered it), is passively eavesdropping on the network. The attacker obtains (A1,B1,A2,B2) from the network. Let T = A1. The attacker then uses the private key X to compute,

By padding t with leading zeros the value T0 is constructed. The attacker knows all of the IDs, and can guess i. So, the attacker can compute k = a2 = F1(T0||ID||i). Since the attacker also obtains A2 = gk = ga2 mod p from the net the attacker is in a position to compute B2a2 mod p. To see this, note that the attacker can guess ID and i and compute a guess for a2. To verify, the attacker raises g to this guess and compares the result to A2. If they match, then a2 has been found without a shadow of a doubt. The attacker can therefore compute the second Diffie-Hellman secret ga2b2 mod p and listen in on Alice and Bob's second conversation.

The attack can be extended to encompass several key exchanges. This can be accomplished by having the dishonest device compute the values a3 = GenPrivateExponent2(a2), a4 = GenPrivateExponent2(a3), and so forth. Every so often a new ai should be chosen randomly to commence a new attack. This is necessary to guarantee forward secrecy, that is, to guard against the device being reverse engineered, studied, repaired, redeployed, and then subsequently compromised.

12.3 Security of the Diffie-Hellman SETUP Attack

The entire proof that this attack constitutes a secretly embedded trapdoor with universal protection will not be given. However, the two non-trivial aspects of this proof will be sketched out. It is stressed that these are proofs in the random oracle model and that when the attack is implemented it is subject to the weaknesses of the primitive used to instantiate the oracle. The proof that the attack satisfies Property 2 will be outlined. It is shown that in the random oracle model, the exponents that are output by the cryptotrojan are computationally indistinguishable from the exponents that are output by the honest exponent generation algorithm. The proof that the outputs are confidential, even against a successful reverse engineer is then outlined. This is Property 4 of a SETUP attack and it holds using a reduction argument.

12.3.1 Indistinguishability of Outputs

It is assumed that the distinguishing adversary knows the cryptotrojan algorithm. This could be from prior reverse engineering endeavors. Hence, the attacker's public key (Y, g, p) is known to the adversary. Since the adversary has not reverse engineered the particular device in question the adversary does not know the value ID right off the bat.

There is nothing to distinguish when i > Θ, so we will consider the case that i < Θ. The first observation is that indistinguishability does not hold against an adversary that has unbounded computational resources. Such an adversary can solve Diffie-Hellman and hence knows T0. This means that the adversary is capable of predicting the subsequent private exponents perfectly. The attacker can guess a value for ID and then invoke the exponent generation device, say four times. The adversary then collects the four exponents that the device outputs. This data set is used to help test if the guess for ID was correct or not. The adversary knows that the values for i will be i, i + 1, i + 2, and i + 3. Since i ≤ Θ can be guessed, the adversary will be able to verify correctly with overwhelming probability whether or not the guess for ID was correct. The adversary can probe the integrity of the device's output values by performing the same computations that the device would do if it were dishonest and comparing the results with the data set. If the values do not match the data set, ID may be guessed again. In time, the computationally unbounded adversary will be able to try all IDs and hence distinguish an honest device from a dishonest one. The attack is, however, indistinguishable to all adversaries that are polynomially bounded in computational power.4

Let C denote the honest device that uses GenPrivateExponent1() and let C′ denote the dishonest device that uses GenPrivateExponent2(). A key observation is that the exponents that are output by the dishonest device are chosen from the same set and same probability distribution as the exponents that are output by the honest device. The honest device will always choose its outputs uniformly at random from  . Note that every device contains a unique string ID, and every device increments i between calls to the oracle. When considering all devices it follows that the portion of the input string corresponding to (ID||i) will never be supplied to the oracle more than once. Since the output of a random oracle is a randomly chosen string that is independent of every other query it follows that the exponents that are output by the dishonest device are drawn from the same set and probability distribution as the outputs of the honest device.

. Note that every device contains a unique string ID, and every device increments i between calls to the oracle. When considering all devices it follows that the portion of the input string corresponding to (ID||i) will never be supplied to the oracle more than once. Since the output of a random oracle is a randomly chosen string that is independent of every other query it follows that the exponents that are output by the dishonest device are drawn from the same set and probability distribution as the outputs of the honest device.

This implies that the only way to distinguish is to guess the oracle input ID correctly. Since ID is not guessable5 and since it is kept secret from all adversaries in the black-box cryptosystem C′, it follows that the outputs of C and C′ are indistinguishable to all computationally bounded adversaries.

12.3.2 Confidentiality of Outputs

Recall that Property 4 of a SETUP attack (see Section 11.4) is confidentiality against a reverse engineering adversary. In this section a reduction argument is given to prove that Property 4 holds. The claim is that there exists an algorithm that can break the confidentiality of the cryptotrojan attack if and only if there exists an algorithm that can compute Diffie-Hellman secrets efficiently. Clearly if Diffie-Hellman can be broken then there exists an efficient algorithm to break the confidentiality of the cryptotrojan. It remains to show the converse, namely, that if there exists an efficient algorithm that can break the cryptotrojan then solving Diffie-Hellman is easy.

In a nutshell this is proven by showing that if an efficient algorithm exists that violates the confidentiality property then Diffie-Hellman can be solved efficiently. This reduction is a randomized reduction and is therefore very strong.6

With regard to confidentiality, it is assumed that the computationally bounded adversary has reverse engineered the device in question and hence knows the value for ID that it contains. It is assumed that the device has been reconstituted and redeployed. It is also assumed that the adversary knows the current value for i that exists in the non-volatile memory store of the device. These are very generous assumptions about what the adversary knows.

To prove confidentiality of the dishonest device it is necessary to show that the adversary cannot compute ga2a2 mod p when the adversary has the following view,

The values A1 and A2 in this view are the outputs of C′. The adversary also knows the cryptotrojan algorithm. What the adversary does not have access to is the coin flips that the cryptotrojan will generate once it has been redeployed.

The proof of confidentiality is by contradiction. Suppose for the sake of contradiction that a computationally bounded algorithm A exists. For a randomly chosen input, algorithm A solves Diffie-Hellman on (A2, B2) with non-negligible probability. The adversary could thus use algorithm A to break the confidentiality of the system. Algorithm A solves Diffie-Hellman on (A2, B2) when it “feels” so inclined, but must do so a non-negligible portion of the time.

It is important to first set the stage for the proof. The adversary is trying to break the key exchange (A2, B2) that was computed in part by the cryptotrojan. Hence, this Diffie-Hellman secret was created using a call to the random oracle R. It is conceivable that an algorithm A that breaks the confidentiality will make oracle calls as well to break (A2, B2). Perhaps A will even make some of the same oracle calls as the cryptotrojan. However, in the proof we cannot assume this. All that can be assumed is that A makes at most a polynomial7 number of calls to the oracle and we are free to trap each one of these calls and take the arguments.

Consider the following algorithm SolveDiffieHellman that uses A as an oracle to solve the Diffie-Hellman problem.

SolveDiffieHellman (g, p, U, V):

input: prime p, generator g of G, U = gu mod p, and V = gv mod p

output: an element ψ contained in G

1. choose rl,r2,r3,r4,r5, and r6 randomly from

2. choose ID to be a random |p|-bit string

3. choose i randomly from {1,2, ..., Θ}

4. simulate k = A(ID,i,Ur2r1, gr2,p,Vr2r3,gr2r4,Ur2r5,Vr2r6), watch calls to R, and store the |p| most significant bits of each call in list

5. compute k0 = k(r2r5r6)−1 mod p

6. remove all elements from  that are not contained in G

that are not contained in G

7. let L be the number of elements in

8. if L = 0 then

9. set β to be a random element in G

10. else

11. choose α randomly from {0, 1, 2, ..., L − 1}

12. let β be the αth element in

13. compute k1 = β(r2r1r3)−1 mod p

14. generate bit b randomly

15. output ψ = kb and halt

Note that with non-negligible probability A will not balk due to the choice of ID and i. Denote by Tuv the |p| bit binary string that corresponds to the value gr2ur1vr3 mod p when padded appropriately. Denote by E the event that in a given invocation of A, algorithm A calls the random oracle R on (Tuv||ID||i) at least once. Clearly only one of the two following possibilities hold:

- Event E occurs with negligible probability.

- Event E occurs with non-negligible probability.

Consider case (1). Algorithm A can detect that Ur2r5 mod p was not generated by the cryptotrojan by appropriately supplying (Tuv||ID||i) to the random oracle. Once verified, A can balk and not output the base gr2 mod p Diffie-Hellman secret corresponding to (Ur2r5,Vr2r6). But in case (1) this can only occur at most a negligible fraction of the time since changing even a single bit in the value supplied to the oracle elicits an independently random response. By assumption, A returns the base gr2 mod p Diffie-Hellman secret corresponding to (Ur2r5, Vr2r6) a non-negligible fraction of the time. Since the difference between a non-negligible number and negligible number is a non-negligible number it follows that A solves the base gr2 mod p Diffie-Hellman problem on (Ur2r5,Vr2r6) without relying on the random oracle. So, in case (1) it follows that with non-negligible probability b will be 0 and SolveDiffieHellman will output ψ = k0 = guv mod p.

Now consider case (2). After making an oracle call with Tuv algorithm A will be able to detect that the value Ur2rr mod p was generated incorrectly. Being adversarial in nature, algorithm A may not wish to lend a helping hand and may in fact immediately balk. But, it is too late. Since A makes at most a polynomial number of calls8 to R the value for L cannot be too large. Since A invokes the oracle with the string (Tuv||ID||i) with non-negligible probability and since L cannot be too large it follows that Tuv will be equal to Tc with non-negligible probability. So, with non-negligible probability SolveDiffieHellman captures the needed Diffie-Hellman secret that was passed to the oracle and raises it to the (r2r1r3)−1 power. Recall that Ur2r1 mod p was submitted to A in place of Y and Vr2r3 mod p was submited to A in place of A1. So, despite any subsequent misbehavior by A, SolveDiffieHellman computes k1 = guv mod p with non-negligible probability. It follows that with non-negligible probability b will be 1 and SolveDiffieHellman will output ψ = k1 = guv mod p.

It has been shown that in either case, the existence of A contradicts the Diffie-Hellman assumption. So, the original assumption that adversary A exists is wrong. This proves that the cryptotrojan satisfies Property 4 of a SETUP attack.

This attack is the very essence of kleptography. It uses cryptography directly to attack cryptography itself. The Diffie-Hellman key exchange is used to securely and subliminally compromise a key exchange between two unwary users, namely, Alice and Bob. The notion of a reduction argument is used to prove the confidentiality of the attack in the random oracle model. Assuming the existence of a random oracle, the attack on Diffie-Hellman is as secure as Diffie-Hellman itself. The notion of computational indistinguishability of probability distributions is used to prove that the attack cannot be detected in black-box environments. It is a demonstration that modern cryptographic paradigms and tools can be used to subvert computer systems in a forward-engineering fashion.

12.4 Intuition Behind the Attack

Having seen the application of this attack to Diffie-Hellman, it is now possible to shed more light on the intuition behind the attack. On the surface the attack is nothing more than a random number generator that takes an auxiliary input and outputs a value drawn uniformly at random from  . However, just below the surface something utterly insidious is occurring. When the auxiliary input is an exponent of g, the device performs a key exchange with the attacker's public key and submits the resulting shared secret to a random oracle. Provided that a modular exponentiation that uses the auxiliary value is made available to the attacker, the whole cryptosystem that uses the random number generator can be securely and subliminally compromised. As will become clear in the following sections, this modular exponentiation is a discrete-log kleptogram.

. However, just below the surface something utterly insidious is occurring. When the auxiliary input is an exponent of g, the device performs a key exchange with the attacker's public key and submits the resulting shared secret to a random oracle. Provided that a modular exponentiation that uses the auxiliary value is made available to the attacker, the whole cryptosystem that uses the random number generator can be securely and subliminally compromised. As will become clear in the following sections, this modular exponentiation is a discrete-log kleptogram.

How and why is this attack possible? It is based on two very powerful notions: the ability to conduct key exchanges over untrusted networks and the notion of a cryptographic one-way function with certain randomness properties. The notion of a random oracle is more of a tool than a practical reality. It is a point in fact that no such efficient oracle can even be synthesized. Yet it nonetheless constitutes a very useful tool for proving the security of cryptographic algorithms. Random oracle proofs essentially show that if any weakness exists in a fielded cryptosystem that is based on a correct random oracle proof, then the weakness must reside in the choice of the primitive that was used to instantiate the oracle.

It might not be immediately clear what the advantages of this attack are over using a pseudorandom number generator with a fixed secret seed. First, note that if the device containing C′ is reverse engineered and subsequently repaired or replaced with an identical-looking device, the reverse engineer will still not be able to exploit the presence of C′. The attacker will continue to gain access to private keys and so forth, but the reverse engineer will not. Also, when the pseudorandom number generator approach is used, the device could be reverse engineered, the seed learned, the device reinstated, and the reverse engineer, along with the attacker, would know all of the future secrets. The attacker would be none the wiser. In covert applications, gathering data may not be acceptable if the act of doing so runs the risk of having it fall into enemy hands.

With some simple modifications, the attack is also favorable for deployment in software. The ID string could be replaced by the IP address of the current machine, or perhaps something else that is public and unique. This would ensure that the device chooses random values in each invocation. This way, the software containing GenPrivateExponent2 could be duplicated as is. The public key Y would act as a secret (until it is perhaps discovered and disclosed). Although far from tamper-resistant, this approach retains many of the properties of the approach that is taken here that assumes tamper-resistance.

12.5 Kleptogram Attack Methodology

The discrete-log SETUP primitive can be applied across a great many discrete-log based cryptosystems. There is an underlying methodology on how to synthesize a SETUP attack against a discrete-log based cryptosystem. This methodology is given below.

- Identification of a kleptogram: To apply the discrete-log SETUP attack, it is necessary to find a modular exponentiation that the device outputs.

- Availability of the kleptogram to the attacker: This modular exponentiation must eventually become available to the attacker (for example, the manufacturer). It can be encoded into a public key, a digital signature, a ciphertext, and so on. Sometimes a modular exponentiation can be reconstructed based on the outputs of a cryptosystem (for example, gk mod p can be reconstructed from a DSA signature).

- Availability of the exponent to the SETUP mechanism: The exponent of this modular exponentiation must be available within the device at the time that the modular exponentiation is computed. This is necessary for the SETUP attack to function. Such a modular exponentiation constitutes a discrete-log kleptogram.

- Exploitation of the kleptogram: The exponent of the kleptogram is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. As a result, this primitive will output a securely compromised random number.

- Using the compromised nonce: The random number that is output by GenPrivateExponent2 must be used as a secret nonce in the underlying cryptosystem. Provided that the exposure of this nonce to the attacker will compromise the cryptosystem that uses GenPrivateExponent2, the attack (should) constitute a SETUP attack.

It is stressed that the above steps are a heuristic approach to identifying kleptographic attacks in discrete-log based cryptosystems. There is no guarantee that this approach will always work. Yet it is nonetheless a good way to think kleptographically.

12.6 PKCS SETUP Attacks

The two most basic types of asymmetric algorithms are encryption algorithms and digital signature algorithms. SETUP attacks exist against discrete-log based algorithms that fall into both of these categories. In this section SETUP attacks are presented against discrete-log based asymmetric encryption algorithms.

The SETUP mechanism is nefariously placed in encryption algorithms, not decryption algorithms, since it is anticipated that ciphertexts may become readily available to the attacker over a public network. These attacks may all be construed as cryptotrojan attacks against programs that perform public key encryption. The payload of the cryptotrojan securely and subliminally leaks plaintexts to the insider.

12.6.1 ElGamal PKCS SETUP Attack

Consider the ElGamal encryption algorithm (see Appendix C.2.1). Consider two different ElGamal encryptions (a1,b1) and (a2,b2). Let a1 = gk1 mod p and let a2 = gk2 mod p. Also, let b1 = yk1m1 mod p and let b2 = yk2 m2 mod p.

The first objective is to identify a kleptogram. Observe that a1 is a modular exponentiation and hence it satisfies step (1). Since the ciphertext (a1,b1) may be sent across a public network, the value a1 may eventually be obtained by the attacker. So the value a1 satisfies step (2). The exponent k1 is generated by the ElGamal encryption algorithm and so is readily available to the encryption algorithm.9 So, a1 satisfies property (3) as well. Suppose that k1 is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. This will satisfy step (4). Finally, by setting k2 = GenPrivateExponent2(k1) instead of generating k2 randomly, the output will constitute a random nonce in the second encryption. So, this approach satisfies step (5).

The question remains as to whether or not this is a SETUP attack. The attacker can obtain a1 = gk1 mod p from the public network. By computing t = aX1 mod p and padding with zeros as necessary, the value T0 can be obtained by the attacker. As a result, the attacker is in a position to compute k2 = F1(T0||ID||i) by guessing ID and i. As in the attack on Diffie-Hellman, all guesses can be verified for correctness. Since the attacker can compute k2, the attacker can compute b2y−k2 mod p. This value is m2.

Observe that this attack utilizes fresh randomness in the form of k1. This assures confidentiality of future outputs against a cryptanalyzing adversary10 that learns ID and gX mod p. The attack can be chained in the same way as the attack on the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. The proof that this is a secure SETUP is very much the same as the proof for the attack on Diffie-Hellman. This should come as no surprise due to the relationship between Diffie-Hellman and the ElGamal encryption scheme (see the reduction in Appendix C.2.2).

Typically, when public key cryptography is needed to encrypt bulk data, hybrid cryptosystems are used. Thus, in this mode of usage, the SETUP can leak keys. It can leak the randomly generated symmetric keys used to encrypt the data. An optimal bandwidth attack can be implemented in an ElGamal based hybrid system as follows. In a nutshell, the value F1(T0||ID||i) can be used directly or indirectly to derive the bits in the symmetric key for the hybrid encryption. The legitimate message recipient decrypts (a, b) to obtain the needed symmetric key. So does the attacker, in effect.

Another attack exists against cryptographic providers such as smart cards that are given access to private decryption keys and that are used to both encrypt and decrypt messages. Let Alice be the user of the provider that contains the cryptotrojan and let Bob be a user with public key (yb,g,p). Alice's public key is (ya,g,p). In this attack, the cryptotrojan in Alice's provider only mounts the attack when it obtains Alice's private key xa in ya = gxa mod p. The provider must obtain access to it when she decrypts the first message that she receives.

Once the value xa is obtained by the provider, the attack commences. In the attack, the nonce ki that is used to encrypt a message to Bob is not chosen randomly. Instead, it is chosen based on the shared Diffie-Hellman secret gxaX mod p. More specifically, when the ciphertext to Bob is the ith encryption that the provider computes after that attack commences, Alice's provider computes the nonce to be ki = F1(T0||ID||i) where T0 is Alice and the attacker's shared Diffie-Hellman secret, padded accordingly. Once again this demonstrates the use of cryptography to attack cryptography itself. The cryptotrojan uses the shared Diffie-Hellman secret of Alice and the attacker to compute ki. The nonce ki is used to compute ybki mod p, a shared Diffie-Hellman secret between Alice's cryptographic provider and Bob. Recall that in ElGamal, this quantity is computed during data encryption.

The indistinguishability of this attack hinges on the secrecy of the value ID. To see this, note that Alice may be inquisitive and may try to determine if her device carries out this attack. She may have reverse engineered a similar device11 and hence obtained gX mod p. She thus knows the shared secret T0 since she knows her own private key. However, since a random oracle is used and since ID is unknown to Alice, indistinguishability still holds. This is a bandwidth-optimal attack on ElGamal encryption since the attacker need only obtain Alice's public key (ya,g,p) and the ElGamal encryption to perform decryption.

Now consider confidentiality against a cryptanalyzing adversary. Such an adversary may be assumed to have access to the value ID in Alice's device, and also gX mod p via reverse engineering. It must, however, be the case that xa is not known to such an adversary. This happens when, for instance, the device is given only temporary access to xa. Confidentiality holds based on the fact that neither xa nor X is known to the adversary. Hence, the Diffie-Hellman secret T0 that the attacker shares with Alice's device is not known to the cryptanalyzing adversary.

12.6.2 Cramer-Shoup PKCS SETUP Attack

The Cramer-Shoup cryptosystem is described in Appendix C.2.3. The public key in Cramer-Shoup is (g1, g2,c,d,h) and the ciphertext is the tuple (u1,u2,e,v).

For simplicity it will be assumed that G is a cyclic subgroup of  where p is prime. Consider two separate encryptions in Cramer-Shoup. Let (u1,u2,e,v) be an encryption of m that uses r as the nonce and let (u′1,u′2,e′,v′) be an encryption of m′ that uses r′ as the nonce.

where p is prime. Consider two separate encryptions in Cramer-Shoup. Let (u1,u2,e,v) be an encryption of m that uses r as the nonce and let (u′1,u′2,e′,v′) be an encryption of m′ that uses r′ as the nonce.

The first objective is to identify a kleptogram. Observe that u1 is a modular exponentiation and hence it satisfies step (1). Since the ciphertext may be sent across a public network, the value u1 may eventually be obtained by the attacker. So the value u1 satisfies step (2). The exponent r is generated by the Cramer-Shoup encryption algorithm and so is readily available to the encryption algorithm. So, u1 satisfies property (3) as well. Suppose that r is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. This will satisfy step (4). Finally, by computing r′ = GenPrivateExponent2(r) instead of choosing r′ randomly, the output will constitute a random nonce in the second encryption. So, this approach satisfies step (5).

The question remains as to whether or not this is a SETUP attack. The attacker can obtain u1 = gr mod p from the public network. By computing t = uX1 mod p and padding with zeros as necessary, the value T0 can be obtained by the attacker. As a result, the attacker is in a position to compute r′ = F1(T0||ID||i) by guessing ID and i. As in the attack on Diffie-Hellman, all guesses can be verified for correctness. Since the attacker can compute r′, the attacker can compute the message m′ = e′h−r′ mod p. The attack can be chained in the same way as the attack on the Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

12.7 SETUP Attacks on Digital Signature Algorithms

SETUP attacks against discrete-log based signature schemes constitute a direct extension of the work of Gus Simmons on the Prisoner's Problem. In this section SETUP attacks against discrete-log based signature schemes are given. The SETUP mechanism is placed in the algorithm that computes digital signatures, not the signature verification algorithm, since it is anticipated that digital signatures may eventually become available to the attacker. These attacks may be construed as cryptotrojan attacks against programs that compute and output digital signatures. The payload of the cryptotrojan securely and subliminally leaks signing private keys to the insider.

These attacks assume that the devices are implemented with a priori knowledge of the values for g, p, q, and so on that the users will use. The primes p and q can still be chosen using a one-way hash function so as to dismiss any suspicions that they are trapdoor primes. This will not hinder the effectiveness of the attacks. These parameters are often fixed for all users. In these SETUP attacks, trapdoor primes are not needed;12 any primes will do.

A related, but different, attack on signature algorithms that uses weak pseudorandomness has been shown [17]. The main difference between this attack and SETUP attacks is that SETUP attacks use randomness as well as carefully computed pseudorandomness in concert with the attacker's public key that is included in the black-box device.

12.7.1 SETUP in the ElGamal Signature Algorithm

A SETUP attack on the ElGamal signature algorithm was proposed that is based on the notion of a subliminal channel [333]. However, the attack is a rather weak form of SETUP. The attack was later strengthened [336]. Both of these attacks required that the attacker obtain two digital signatures in order to recover the signing private key.

In this subsection the attack is improved substantially by making a simple observation. The observation is as follows. The attacker can include the public key Y in the device to mount the attack. The unwary user has a public key y and a corresponding signing private key x that is supplied to the signature algorithm. This immediately implies that the user and the attacker have a shared Diffie-Hellman secret. The secret is Yx = yX = gXx mod p. This fact can be utilized to securely and subliminally leak the signing private key x at a higher bandwidth than previous approaches.

The ElGamal digital signature algorithm is described in Appendix C.2.4. The user's public key is (y,g,p) and the signature on m is (r, s). The value r equals gk mod p where k is the randomly chosen nonce for the signature.

The first objective is to identify a kleptogram. Observe that y is a modular exponentiation and hence it satisfies step (1). Since the public key (y,g,p) may be obtained by the attacker, the value y satisfies step (2). The exponent x is given to the ElGamal signing algorithm by the user and so is readily available within the signing algorithm. So, y satisfies property (3) as well. Suppose that x is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. This will satisfy step (4). Finally, by computing k = GenPrivateExponent2(x) instead of choosing k randomly, the output will constitute a random nonce in the signature (r, s). So, this approach satisfies step (5).

The question remains as to whether or not this is a SETUP attack. Suppose that the attacker can obtain y = gx mod p from a public network. By computing t = yX mod p and padding with zeros as necessary, the value T0 can be obtained by the attacker. As a result, the attacker is in a position to compute k = F1(T0||ID||i) by guessing ID and i. As in the attack on Diffie-Hellman, all guesses can be verified for correctness. In this attack the argument T0 that is passed to the oracle will always be the same. It is the binary string corresponding to the secret that the unwary user and the attacker share. However, since i is incremented in each device, random values for k will always be used.

Suppose that r has a multiplicative inverse modulo p − 1. If r is even, then it clearly does not have such an inverse. The inverse will exist whenever gcd(r, p − 1) = 1. If the inverse exists, then the attacker can compute x = r−1(H(m) − sk) mod p − 1 since the attacker can compute k. The possibility that r does not have an inverse is becoming less of an issue year after year, since cryptosystems are typically defined over prime order subgroups for security reasons. It is not hard to see that this attack against classical ElGamal nonetheless leaks x at a high bandwidth.

Consider the case that the user who knows x is curious and wants to know if his or her black-box device is carrying out the attack. If this user reverse engineers a similar device then it may be assumed that gX mod p is obtained. Therefore, the user knows T0. However, the particular value for ID in the user's device is secret. It follows that under the random oracle assumption k will be random. This assures indistinguishability. Confidentiality holds under a random oracle argument based on the Diffie-Hellman assumption.

12.7.2 SETUP in the Pointcheval-Stern Algorithm

The Pointcheval-Stern digital signature algorithm is described in Appendix C.2.5. The first objective is to identify a kleptogram. Observe that y is a modular exponentiation and hence it satisfies step (1). Since the public key (y,g,p) may be obtained by the attacker, the value y satisfies step (2). The exponent x is given to the Pointcheval-Stern signing algorithm by the user and so is readily available within the signing algorithm. So, y satisfies property (3) as well. Suppose that x is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. This will satisfy step (4). Finally, by computing k = GenPrivateExponent2(x) instead of choosing k randomly, the output will constitute a random nonce in the signature (r, s). So, this approach satisfies step (5).

The question remains as to whether or not this is a SETUP attack. Suppose the attacker can obtain y = gx mod p from a public network. By computing t = yX mod p and padding with zeros as necessary, the value T0 can be obtained by the attacker. As a result, the attacker is in a position to compute k = F1(T0||ID||i) by guessing ID and i. As in the attack on Diffie-Hellman, all guesses can be verified for correctness. In this attack the argument T0 that is passed to the random oracle will always be the same. However, since i is incremented in each device, random values for k will always be used.

Suppose that r has a multiplicative inverse modulo p − 1. In this case the attacker can compute x = r−1 (H(r||m) − sk) mod p − 1 since the attacker can compute k. Despite the potential non-existence of an inverse of r, this attack nonetheless leaks x at a high bandwidth over the signatures that are output.

12.7.3 SETUP in DSA

The Digital Signature Algorithm is described in Appendix C.2.7. The order of g in DSA is q so g generates a prime order subgroup of  in DSA. The user's public key is (y, g, p). The private key of the user is x < q. The signature on a message m is (r, s) where r = (gk mod p) mod q.

in DSA. The user's public key is (y, g, p). The private key of the user is x < q. The signature on a message m is (r, s) where r = (gk mod p) mod q.

The first objective is to identify a kleptogram. Observe that y is a modular exponentiation and hence it satisfies step (1). Since the public key (y,g,p) may be obtained by the attacker, the value y satisfies step (2). The exponent x is given to the DSA signing algorithm by the user and so is readily available within the signing algorithm. So, y satisfies property (3) as well. Suppose that x is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. This will satisfy step (4). Finally, by computing k = GenPrivateExponent2(x) instead of choosing k randomly, the output will constitute a random nonce in the signature (r, s). So, this approach satisfies step (5).

The question remains as to whether or not this is a SETUP attack. Suppose the attacker can obtain y = gx mod p from a public network. By computing t = yX mod p and padding with zeros as necessary, the value T0 can be obtained by the attacker. As a result, the attacker is in a position to compute k = F1(T0||ID||i) by guessing ID and i. As in the attack on Diffie-Hellman, all guesses can be verified for correctness. In this attack the argument T0 that is passed to the random oracle will always be the same. In essence, it is the Diffie-Hellman secret Yx = yX = gXx mod p that is shared between the unwary user and the attacker. Since i is incremented in each device, random values for k will always be used. Since r < q it follows that r will have a unique multiplicative inverse modulo q. So, the attacker can compute x = r−1(sk − H(m)) mod q since the attacker can compute k.

This attack can applied to the Prisoner's Problem of Gus Simmons. Using this attack, Alice can securely and subliminally leak her signing private key x to Bob under the observance of a warden in a single digital signature. As a result, it effectively increases the bandwidth of the Legendre channel from 14 bits to 160 bits, the size of the entire signing private key. Also, this attack has the novel feature that it can be accomplished without requiring that Alice give her private key to Bob before going to prison.

12.7.4 SETUP in the Schnorr Signature Algorithm

The Schnorr digital signature algorithm is described in Appendix C.2.6. The order of g in Schnorr is q so g generates a prime order subgroup of  in Schnorr. The user's public key is (y,g,p) where y = g−x mod p. The signature on a message m is (e, s) where e = H(m||r) and r = gk mod p.

in Schnorr. The user's public key is (y,g,p) where y = g−x mod p. The signature on a message m is (e, s) where e = H(m||r) and r = gk mod p.

The first objective is to identify a kleptogram. Observe that y is a modular exponentiation and hence it satisfies step (1). Since the public key (y, g, p) may be obtained by the attacker, the value y satisfies step (2). The exponent x is given to the Schnorr signing algorithm by the user and so is readily available within the signing algorithm. So, y satisfies property (3) as well. Suppose that x is fed as input to GenPrivateExponent2. This will satisfy step (4). Finally, by computing k = GenPrivateExponent2(x) instead of choosing k randomly, the output will constitute a random nonce in the signature (e,s). So, this approach satisfies step (5).

The question remains as to whether or not this is a SETUP attack. Suppose the attacker can obtain y = g−x mod p from a public network. By computing t = yX mod p and padding with zeros as necessary, the value T0 can be obtained by the attacker. As a result, the attacker is in a position to compute k = F1(T0||ID||i) by guessing ID and i. As in the attack on Diffie-Hellman, all guesses can be verified for correctness. Since e < q it follows that e will have a unique multiplicative inverse modulo q. So, the attacker can compute x = e−1(s − k) mod q since the attacker can compute k.

12.8 Rogue Use of DSA for Encryption

One of the criticisms of DSA was that it does not provide for secret key distribution, as RSA does. Smid and Branstad indicated that DSA is inherently different from RSA in this respect when they stated that “The DSA does not provide for secret key distribution because DSA is not intended for secret key distribution” [284]. This perceived feature of DSA over RSA is in fact non-existent. DSA can be exploited to securely communicate messages between two colluding users.

Nyberg and Rueppel showed a way to abuse DSA. They showed how to securely integrate DSA with key distribution by computing the signature (r, s) with H(m) = 1 [209]. However, setting H(m) = 1 makes the abuse of DSA blatantly obvious.

Borrowing ideas from kleptography, it was shown how to abuse DSA without setting H(m) = 1 in the signature [336]. It is based on the observation that the value gk mod p can be recovered from (r, s). This can be done as follows,

So, Alice can send a DSA signed message to Bob that is effectively asymmetrically encrypted as follows. Alice chooses k randomly and raises Bob's DSA public key y to this k, thereby yielding a secret Diffie-Hellman key z = yk mod p. Alice then encrypts this message using z as the symmetric key in classical cipher. Alice signs the resulting ciphertext using her DSA private key, using k as the nonce in her DSA signature. Bob can recover gk mod p using the signature (r, s). He can then compute z by raising gk mod p to his private key. With z he can decrypt the signed message that was symmetrically encrypted. The only information that is sent is the encrypted file, which is the message that is signed, and (r, s).

12.9 Other Work in Kleptography

There are numerous other results in kleptography and related areas that are not presented in this book. In this section some of these results are mentioned. In particular the topic of embedding a backdoor into a symmetric cipher is addressed. Also, heuristics are given for designers of symmetric ciphers for showing the absence of backdoors in the ciphers they create. These are only heuristics and are by no means foolproof. This list of results may not be exhaustive, so we apologize in advance if any results are omitted.

It has been shown how to use public key encryption to turn the Newton channel, which is a broadcast channel, into a private subliminal channel [339]. This is a form of kleptographic attack that utilizes the Newton channel directly. The attack can be used to leak the ElGamal signing private key in each ElGamal signature that is output by the signing device. The attack requires 160 bits of smoothness in p − 1, where p is the modulus in the ElGamal public key.

A challenging problem is to implement a secure backdoor in a symmetric cipher. This is challenging since typical symmetric ciphers are deterministic and therefore make it difficult to exploit randomness in computations. Symmetric ciphers have been proposed in the past that have secret specifications. Despite this security by obscurity approach, the U.S. government proposed Skipjack [41, 200] as a secret cipher and planned on deploying it in the Clipper chip. Efforts have been made to research the possibility of building backdoors into secret ciphers, as well as building backdoors into public ciphers. Such results are merely plausibility results, geared towards casting doubt on questionable COMSEC practices that are based in part on secrecy.

The construction of symmetric ciphers with backdoors was addressed by Blaze, Feigenbaum, and Leighton [29]. They showed that a symmetric cipher with such a backdoor is equivalent to a public key cryptosystem. To see this, note that if Alice chooses a symmetric key randomly and then encrypts a message with it using a backdoor symmetric cipher, she and the insider can access the plaintext. No one else can. Alice can thus send asymmetrically encrypted data to Bob by encrypting it with a randomly chosen symmetric key and then sending the resulting ciphertext to him. Bob need not know the symmetric key she used per se, as long as the backdoor gives him access to the plaintext. In this scenario the public keys are in fact the specification of the backdoor symmetric cipher themselves.

Rijmen and Preneel proposed a trapdoor cipher that has a public specification and that still provides the designer with an exclusive advantage [240]. The recovery ability in their algorithm is based on a very specific trapdoor that allows the designer to break the encryption using linear cryptanalysis. This cipher was subsequently cryptanalyzed [323]. Patarin and Goubin also proposed a symmetric cipher with a backdoor in it [220]. This method was also cryptanalyzed [24, 93].

Monkey is an example of a backdoor attack that requires that its design be kept secret [338]. It is a black-box symmetric cryptosystem with a public I/O specification, an 80-bit key, and a 64-bit block size. In order for Monkey to leak symmetric key information it is required that the designer obtain a sufficient amount of ciphertexts under a given key k such that each contains a particular known-plaintext bit. This allows the designer to recover k. Monkey reveals one plaintext bit in each ciphertext to a successful reverse engineer.

A successor to Monkey, called Black-Rugose, was recently proposed [340]. This design eliminates the need for known plaintext entirely to leak symmetric key information to the insider. Monkey leaks a bound on the message entropy to the reverse engineer. It requires that the designer obtain a sufficient number of ciphertexts that encrypt messages with a requisite level of redundancy. The information leakage method that is used employs data compression as a basic tool to generate a subliminal channel.

The potential of inserting backdoors into symmetric ciphers suggests that all internal constants proposed in an algorithm have to be justified in order to argue that a design-level attack is not being carried out. There are two basic approaches to this. The first is to pass a seed through a one-way function and let the cipher constants be the output of the one-way function. The seed is used to help prove that the constants were not maliciously chosen. The MARS symmetric cipher utilized SHA-1 applied to seeding information to derive S-Box values [45]. MARS was chosen as a finalist in the AES selection process. Another approach is to utilize universal constants such as π and e. The Blowfish cipher utilizes the digits of π in hexadecimal as S-Box values [258]. In practice, candidate S-Box values must be tested against the threat of linear cryptanalysis [180], differential cryptanalysis [25, 72], and so on before they are used.

Weis and Lucks showed attacks on black-box ciphers that exploit the randomness used in the choice of initialization vectors and other avenues that might be readily available to a design-level attacker [316]. The attacks are geared exclusively towards deterministic devices that perform secret key encryption. It was shown how to kleptographically compromise stream ciphers.

Kleptographic attacks can be thought of as design-level abuses of cryptographic algorithms. The attacks that were shown affect key generation algorithms, public key encryption algorithms, and digital signing algorithms. Yet there are other primitives used in modern cryptography that may be undermined as well. Ways have been investigated on how to subjugate threshold cryptosystems based on the fact that no single user possesses the entire private key [324]. A source of potential abuses is the fact that third parties do not know whether or how a secret key is shared due to the transparent nature of secret sharing. This was dubbed the dark side of threshold cryptography.

12.10 Should You Trust Your Smart Card?

When implemented properly,13 SETUP attacks give the manufacturer your private keys in such a way that you cannot detect the transgression without reverse engineering the card. In the case of RSA, for example, by virtue of publishing your public key you are giving your corresponding private key to the manufacturer when the manufacturer implements the malicious key generation algorithm described in Section 11.5. Given the current state of industry standards there is little reason to trust any smart card whatsoever unless you trust the manufacturer entirely. As PKI takes root, the potential payoff for a company that carries out a SETUP attack will only increase.

Countering the threat of a SETUP attack is a subtle business. Consider the attack on the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. The device can behave in a completely unpredictable, Byzantine fashion. It could flip a 224 sided coin, and mount the attack if and only if the result of the toss is 1. The device would therefore be honest most of the time. This demonstrates the peril in trusting black-boxes. If Alice tests 210 outputs to check for a SETUP, the device can flip a 225 sided coin. If Alice tests 215 outputs, the device could flip a 235 sided coin, and so on.

In general there is no need for a Diffie-Hellman key exchange device to output the exponent it generates randomly in each key exchange to the user. The device need only output the modular exponentiation and the shared secret to be of use. The reason that the device in the Diffie-Hellman SETUP attack outputs exponents was to show that the attack works even in this worst-case scenario. However, the following countermeasure can be used to help show that the key exchanges are honest (that is, that no SETUP attack is being performed). Rather than choosing the exponent randomly, the device chooses a seed s randomly and passes it through a public one-way hash function14 to obtain H(s). The value H(s) is then used as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange exponent. In addition to the normal Diffie-Hellman key exchange value, the device outputs the seed s to the user. So, Alice's device outputs (s, gH(s) mod p). If she is suspicious she can hash the seed and verify the output of the device.

This is a very general defense mechanism against the threat of discrete-log SETUP attacks. The oracle H(·) is in fact choosing the randomness that is used as the exponent. This countermeasure is by no means perfect. In fact, there is a weakness in it. The device can make numerous calls to the oracle H(·). For instance, the device can continually make calls until the 14 least significant bits of gH(s) mod p are as desired. This channel has a similar bandwidth as the Legendre channel of Gus Simmons. However, if Alice always verifies that her device is operating correctly, she will exert more computational effort than the device. This defeats the purpose of using the device altogether. She may as well do the exchanges herself since she is already computing just as many modular exponentiations as her device.

The approach of using H(·) and having the device output the tuple (s,gH(s) mod p) is nonetheless a very good one. On numerous consulting engagements15 Adam has been asked to “try to get the private key off the smart card.” This directive was administered with the wholehearted belief that it was possible to verify that no one would ever have access to the private key.16 It was a joke, really. Yet a mechanism that permits the verification of the devices' choice of randomness would help to say something meaningful about the integrity of the implementation.

A similar approach is to eliminate all randomness from the device. In this approach the requirement is made that the device be a deterministic algorithm. A separate device supplies the randomness and the device in question uses the randomness to perform public key operations. This approach is hazardous due to the coin-flipping problem. VLSI chips have a variety of ways of generating randomness themselves and it could still mount the SETUP attack once in a blue moon.

To summarize, the following two reasons form fundamental difficulties in dealing with insider threats in probabilistic cryptographic algorithms:

- The device can always “cheat” when you're not looking. Even when you believe it to be deterministic and supply it with randomness yourself for verification purposes, it can with a very small probability ignore your randomness on a given occasion and substitute its own on the sly.

- If you are always looking, then you are doing even more work than the device. This defeats the purpose of using the cryptographic device altogether.

Another option to mitigate the insider threat is to utilize multiple key pairs that are generated and stored on devices made by different manufacturers. In this approach an encryption is computed by encrypting the message multiple times using each different public key. This is often referred to as cascading encryptions. A given document is signed multiple times using each different private key. This way, if one smart card is compromised and another is not, the overall solution will inherit the security of the honest device. The ciphertext layer computed by the honest device will never be breached and the signatures from the honest device will never be forged. This is probably the best approach until industry standards start addressing this problem. (This may be overly optimistic.)

We recommend that users who must rely on smart cards exercise due diligence in investigating all of the manufacturers involved in the complete solution. The manufacturers should be at least as trustworthy as the certificate authority, if not more. We recommend that users be wary of snake oil. If a manufacturer claims they have a whiz-bang cryptographic algorithm or random number generator but will not disclose it in its entirety, then we recommend that their products not be used. Security by obscurity is an unacceptable practice, even when proprietary algorithms are concerned. Published (and preferably standardized) algorithms should always be used by vendors. If a manufacturer claims that there are no backdoors, we recommend that users get a third-party assessment of this and that users verify that the third party had unobstructed access to any and all source code, schematic diagrams, test data, requirements documents, and design documents. This includes any and all such documentation from the chip manufacturer(s). Anything short of this fails to suggest that a backdoor is not present in the design.

A naive response to this issue is the following. “My smart card is a NIST approved FIPS level 140-2 device and I have the certificate to prove it.” Well, this is all fine and good. It could be that the certification lab actually took the time to look for flaws, weaknesses, and backdoors in the code. Even so, where is the guarantee that the specification they analyzed is the one that actually got manufactured? Who's to say that one in every hundred devices doesn't have a SETUP mechanism in it? A commercial FIPS-140 certificate does not provide any assurance that the specification that was certified by NIST is the same one that was implemented in your particular smart card. The payoff for such illicit behavior on behalf of a vendor may not be high now. But as PKI takes root, the potential payoff for a small-fry smart card company to actually carry out a SETUP attack may become staggering. The NIST smart card certification process is both honorable and helpful, yet this does not change the fact that a FIPS-140 certificate is likely to give many people who do not fully understand cryptography and the FIPS certification process a false sense of security against insider threats.

Personally, we would never completely trust a third-party smart card, no matter who made it. It is simply too easy to leak information securely and subliminally in cryptographic parameters or otherwise. If multiple cryptosystems cannot be simultaneously employed from multiple manufacturers then our best advice is to simply assume that someone knows your private key.

However, the following is a fail-safe way to generate a public key and certify it without worrying about backdoors. You will need a coin, pencil, paper, flashlight, and hard hat. It is of course necessary that you be a spelunker and that you leave all electronic devices behind, save for the flashlight.

- Climb down into the deepest crevice in the earth's crust.

- Make sure no one followed you down there.

- Flip the coin and perform Neumann unbiasing on the results to generate unbiased coin tosses.17

- Use the pencil to write down the resulting private key.

- Compute the corresponding public key on the paper.

- Memorize the key pair.

- Burn the paper, pencil, and flashlight.

- Climb back to the surface and submit the public key to a certificate authority.

This may be justly called the Caveman key generation algorithm. Provided that no one invades your brain using extrasensory powers and provided that you use your private key securely, your private key will be known only by you.18

1The attacker can be a hacker, a malicious manufacturer, or an insider.

2For example, the manufacturer could be a malicious entity.

3But even then she'd be victimized.

4Polynomial in |W/2|.

5It is exponential in the security parameter |p|.

6Randomized reductions are very strong since when they hold for a fixed fraction of the inputs there typically exists a reduction that holds with overwhelming probability for all inputs.

7Polynomial in |p|.

8Polynomial in |p|.

9The exponent k1 can be thought of as a resource that can be exploited by a carefully designed cryptotrojan.

10For example, a hacker that obtains an old snapshot of the signing algorithm at run-time.

11For instance, the process of reverse engineering may destroy the device in question. So, she may be able to reverse engineer other devices but not her own without destroying it.

12Trapdoor primes were originally suspected in DSA.

13For example, taking into account timing attacks, differential power analysis, and so on.

14The outputs must look random.

15Fortune 500 companies included.

16Mentioning the existence of kleptographic attacks was ineffectual. The argument was summarily dismissed as being theory. To translate, the Fortune 500 company was basically saying, “We don't care. We are paying our security consultants a lot of money. We are exercising due diligence and hence will not lose our jobs.”

17If it is weighted unfairly, then it is possible that the mint manufactured the coin with a deliberate statistical backdoor.

18This is a joke, of course.