Chapter 11

SETUP Attack on Factoring Based Key Generation

The notion of black-box hardware and software and the hazards associated with them are familiar to everyone. For example, when a user installs a new commercial program there is no easy way to find out if the program is sending personal information across the Internet back to the manufacturer. Such information could include personal e-mail addresses, the name of the user's Internet service provider, what type of machine the user is using, and so on. The fear is that there might be an invasion of privacy that could among other things lead to aggressive marketing. Hardware implementations of algorithms are even more black-box in nature since the silicon housing hides the underlying circuitry.

When cryptosystems are implemented in a black-box fashion this fear is magnified tenfold. In a worst-case scenario the cryptosystem could be sending the user's secret keys back to the manufacturer. This could allow the manufacturer to do such things as decrypt the user's communications, sign documents on behalf of the user, or even gain unlawful access to the user's machine. This chapter addresses this threat by exploring ways of designing cryptotrojans that to do exactly this, in spades.

In the pages that follow, a set of attacks are presented that are specifically designed to attack black-box key generation algorithms that generate factoring based keys. Such key generation algorithms are used to generate private keys for RSA, Rabin, Goldwasser-Micali, and other public key cryptosystems [117, 237, 245]. The first set of attacks are simplistic in nature and have varying degrees of security. Drawbacks to these solutions are presented that relate to the threat of reverse engineering and that affect the security of the attacks. The chapter concludes with an improved cryptotrojan attack that does not suffer from these drawbacks. It is a kleptographic attack that applies cryptography within the cryptographic key generation algorithm to securely undermine the integrity of the device. The cryptotrojan leaks private keys to the attacker securely and subliminally through the seemingly honest output of the black-box device. The attack is secure from the attacker's perspective based on the assumed intractability of factoring. The proof of security is in the random oracle model (see Appendix B.4).

The threat of advanced kleptographic attacks is an extremely important consideration when insider attacks are possible. A cryptotrojan can be inserted into a fraction of all the black-box devices that are produced. This implies that spot reverse engineering checks, that is, choosing devices randomly and checking for the presence of cryptotrojans, will not always work since some of the devices are honest. This issue is even worse when the devices are tamper-resistant. Such chips are the epitome of black-boxes since they are designed to hide the internals from well-funded and dedicated adversaries.

Designing cryptographic devices to be tamper-resistant is an involved science and the security afforded by such devices is an active area of research [8, 10]. Tamper-resistant cryptographic microchips have been endorsed by the U.S. government, namely, in the Clipper chip and Capstone technology. The Clipper and Capstone technologies have been offered as next generation hardware-protected key escrow devices. Even software implementations can be perceived as black-boxes when users refuse to analyze the code at the assembly language level. Simply verifying a digital signature on code in no way proves that the code is free of backdoors.

This chapter is likely to be of interest to companies that manufacture smart cards and organizations that rely on smart cards for sensitive applications. It demonstrates clearly how an insider who has control of cryptographic designs or implementations can benefit from carrying out insider attacks with minimal loss of overall security. Also, this chapter is important to users who wish to use mix networks securely. When a cryptotrojan is used to generate the keys for a mix network, the author of the Trojan is often in a position to trace the flow of messages throughout the network.

Since black-box cryptosystems are central to the security of the attacks in this chapter, the definition of a black-box cryptosystem needs to be spelled out. The definition of a black-box cryptosystem incorporates the notion of efficiently computable functions and thus addresses the issue of computational complexity. Also, it captures ideas from electrical engineering since it makes the worst-case assumption that the black-box has non-volatile memory.

Definition 3 A black-box cryptosystem is an efficient probabilistic algorithm1 that has readable and writable non-volatile memory. In other words, it has access to a fair coin and can store variables across multiple invocations. Furthermore, the algorithm and memory are not externally accessible. Only the input and output of the cryptosystem is accessible.

Note that whereas a manufacturer may claim that a given microchip does not contain non-volatile memory cells, it may nevertheless contain non-volatile memory. Manufacturers could easily lie in this regard. The availability of non-volatile memory has a significant impact on the types of cryptotrojan attacks that can be carried out within the device, since it allows a Trojan to store values across multiple invocations of the device.

11.1 Honest Composite Key Generation

The key generation algorithm GenPrivatePrimes1 described below may be used to generate the primes p and q for RSA private keys, Rabin private keys, Goldwasser-Micali private keys, and so on. However, it does not check that gcd(e, (p − 1)(q − 1)) = 1 as in the case of RSA key generation. This check can be easily added. Most composite key generation algorithms output composite integers of even bit length. Typical lengths are 768, 1024, and 2048 bits. For simplicity GenPrivatePrimes1 will only generate W/2-bit primes such that W is evenly divisible by 2. W should be 768 or greater to provide a suitable setting for the factoring problem. It is a simple matter to multiply these two primes to derive the public key n = pq. The Appendices cover the notation and underlying algorithms that are used.

RandomBitString1():

input: none

output: random W/2-bit string

1. generate a random W/2-bit string str

2. output str and halt

input: none

output: W/2-bit primes p and q such that p ≠ q and |pq| = W

1. for j = 0 to ∞ do:

2. p = RandomBitString1() /* at this point p is a random string */

3. if p ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 and p is prime then break

4. for j = 0 to ∞ do:

5. q = RandomBitString1()

6. if q ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 and q is prime then break

7. if |pq| < W or p = q then goto step 1

8. if p > q then interchange the values p and q

9. set S = (p, q)

10. output S, zeroize all values in memory, and halt

Also, note that there are some elements of the ANSI C programming language in this program [154]. Text that appears between /* and */ are programmer's comments and break causes control to exit the innermost loop. The keyword continue sends control to the beginning of the next iteration of the innermost loop. Testing for primality can be performed in deterministic polynomial-time [5]. A feel for how long this algorithm will take to run can be determined using Chernoff bounds and the Prime Number Theorem (see Appendix B.2).

Observe that a K-bit string can have leading zeros. A K-bit positive integer must have a most significant bit equal to 1. The product of two K-bit positive binary integers with K > 1 is either a 2K bit integer or a 2K − 1 bit integer. To see this, note that 2K−1 is the smallest K-bit integer. 2K−1 squared is 22K−2, which is 2K − 1 bits long. Also, note that 2K − 1 is the largest K-bit positive integer. 2K − 1 squared is 22K − 2K+1 + 1, which is a 2K bit integer. So, in this algorithm it is entirely possible that W/2 bit primes p and q will be chosen such that |pq| < W bits.

11.2 Weak Backdoor Attacks on Composite Key Generation

There exist several Trojan horse attacks on composite key generation. Those presented in this section are all rather simplistic in nature and have varying degrees of security. They are classic attacks in some sense since they are intuitively obvious to any cryptographer. However, none of them is as secure from the attacker's perspective as a secretly embedded trapdoor attack. They are useful to study since they exemplify important properties that a secure cryptotrojan attack against a cryptosystem should exhibit.

11.2.1 Using a Fixed Prime

An attacker can change the design so that the prime p is fixed and known to the attacker, or an attacker can append a Trojan horse to the program that deletes p after GenPrivatePrimes1 is called and that substitutes the fixed prime p. In this case the function GenPrivatePrimes1 may have to be invoked anew if |pq| < W, and so on. Either way, since p is known to the attacker, the attacker can factor every public key that is generated. The modified algorithm is given below.

GenPrivatePrimes2():

input: none

output: W/2-bit primes p and q such that p ≠ q and |pq| = W

1. for j = 0 to ∞ do:

2. q = RandomBitString1()

3. if q ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 and q is prime then break

4. if |pq| < W or p = q then goto step 1

5. if p > q then interchange the values p and q

6. set S = (p, q)

7. output S, zeroize all values in memory, and halt

The rationale behind this attack is that since q is chosen randomly, the modulus will look random to the casual observer. This is important since the modulus n = pq will be made public, for example, by being placed in a digital certificate. An important consideration is that a user is often in a position to learn each of the primes p and q corresponding to his or her own public key. This holds true in the case of software key pairs that are stored in personal information exchange2 files, for instance. However, this is not always the case for private keys that are generated and used in smart cards. If the user has access to (n, e, d) where ed = 1 mod (p − 1)(q − 1) then a well-known3 probabilistic algorithm can be used to efficiently factor n. From the attacker's perspective it is always safest to assume the worst, and that is that p and q will be known to the key owner. This has the following properties:

- The attack is detectable: One need only hypothesize that the attack is being carried out, obtain two moduli n that are output by the device, and compute their greatest common divisor. This value will be p and it will divide both moduli evenly. Note that this detection method will work even if the key owner does not have access to his or her own private key.

- The attack is breakable without reverse engineering: The Euclidean algorithm can be run on two different moduli n and as a result the prime p can be found. So, the device need not even be reverse engineered to break the attack.

- The attack doesn't exhibit forward secrecy vs. reverse engineers: In an ideal situation, the reverse engineer who recovers the algorithm and its current state should not be able to determine the previous prime numbers that the device computed. Since p is revealed to the reverse engineer, this is not the case.

There are numerous variations on this attack. For example, the public modulus n can be generated so that it can be factored more easily than normal. For example, n could be the product of a 512-bit prime and two 256-bit primes. Again, this gives the attacker no significant advantage over other users since anyone can factor such moduli.

11.2.2 Using a Pseudorandom Function

The problem of detectability in the attack described in Subsection 11.2.1 can be avoided by using pseudorandom values instead of random values and having the initial seed known only to the device and the attacker. In the jargon of Turing machines, this means that the algorithm will take its randomness from a pseudorandom Turing machine tape rather than from a truly random tape. Since the pseudorandom tape is polynomially indistinguishable from a truly random tape, the sampled primes will be indistinguishable as well. It makes sense for the attacker to use a pseudorandomness primitive that is predicated on the difficulty of factoring. This way, both of the composites that are generated and the rogue pseudorandom primitive used to compute the primes will rely on the same intractability assumption. Basing the primitive on the discrete logarithm problem would make the attack rely on two potentially different intractability assumptions.

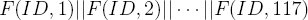

One of the goals of using pseudorandom values is to prevent the backdoor from being exploited by anyone other than the attacker. To those familiar with cryptographic primitives, it may be tempting to utilize a pseudorandom function to accomplish this goal. For example, consider the following approach. The pseudorandom function F is used in the device along with a secret string ID [113, 114]. The string ID should be sufficiently long. For simplicity assume that |ID| = 160. The IDs for the devices should be chosen randomly, subject to the constraint that they all be unique. The function F is publicly known. Recall that F(ID, x) is indistinguishable from a random value, where ID is secret and x is a public index. The pseudorandom bit stream is formed by invoking F with x = 1, 2, 3, .... The index x is stored in non-volatile memory within the device. Hence, the pseudorandom bit stream is F(ID, 1)||F(ID, 2)||F(ID, 3)|| · · ·.

So, why does the attacker have an advantage? Well, observe that at most a polynomial4 number of devices can be manufactured. So, there are a polynomial number of distinct values chosen from all possible 160-bit strings from the database of IDs that only the attacker knows. Without knowing this database, the complexity of guessing an ID correctly is exponential.

Though conceptually simple, this approach does not provide computational forward secrecy. For example, suppose that a reverse engineer opens the device and obtains F, ID, and i = 117. The reverse engineer can recover the previous pseudorandom bits by computing,

It is therefore imperative that the device forgets its past, which is not the case in this approach. So, this particular attack has the following properties.

- The attack is not detectable: Even if a user hypothesizes that this exact attack is being carried out, its presence cannot be detected without knowing ID.

- The attack is not breakable without reverse engineering: The pseudorandom bits that are used by the key generation algorithm are indistinguishable from random ones without knowledge of ID. It follows that provided that the device is not successfully reverse engineered the attack is secure.

- The attack doesn't exhibit forward secrecy vs. reverse engineers: In an ideal situation, the reverse engineer who recovers the algorithm and its current state should not be able to determine the previous prime numbers that the device computed. However, since ID is revealed to the reverse engineer and since x = 1, 2, 3, ..., this is not the case.

The third drawback above is addressed in Subsection 11.2.3. The point of this subsection is not to argue that pseudorandom functions cannot be used to attack key generation in a desirable way. The point that is being made is that a straightforward use of them is not very desirable. What is needed is a mode of operation that is effectively memoryless. A memoryless mode of operation is one that prevents the reverse engineer from being able to determine previous inputs to the function.

11.2.3 Using a Pseudorandom Generator

A solid approach to attacking the composite private key generation algorithm is to use a pseudorandom number generator G (see Subsection 3.5.2) and an initial seed. The attack will be illustrated using the Blum-Blum-Shub. Define G to be a (k, 2k)-PRBG (see Subsection 3.5.2). Define GH(s) to be the k most significant bits of G(s) and define GL(s) to be the k least significant bits of G(s). Let s0 be the randomly chosen 2k-bit initial seed that is stored within the device and that is known to the attacker.

In this attack, the input values si for G are defined by si+1 = GL(si) where i = 0, 1, 2, .... The pseudorandom bit stream that the device uses to compute private keys is defined by GH(s0)||GH(s1)||GH(s2)|| · · ·. When the algorithm outputs (p, q) on a given invocation, only one seed si is stored in non-volatile memory. Previous seeds are erased and lost. It can be shown that the attack has the following properties.

- The attack is not detectable: Even if a user hypothesizes that this exact attack is being carried out, its presence cannot be detected without knowing one of the seeds.

- The attack is not breakable without reverse engineering: The pseudorandom bits that are used by the key generation algorithm are indistinguishable from random ones without knowing one of the seeds. It follows that provided that the device is not successfully reverse engineered, the attack is secure.

- The attack exhibits forward secrecy vs. reverse engineers: Consider the case that a reverse engineer is able to recover the algorithm and its current state. The reverse engineer will not be able to determine the previous prime numbers that the device computed. Doing so implies the ability to invert the pseudorandom generator G.

In practice it would not be wise to provide multiple devices with the same initial seed s0. This would quite literally cause users to generate the same “random” private keys, and would not go unnoticed.

Another threat to the integrity of this attack exists that has not been addressed. Consider the possibility that a powerful engineer can effectively peer into the device, read its contents, and then repair it, replace it, or somehow guarantee that the device will appear to have been left untouched. FIPS-140 level 4 complaint smart cards are supposed to destroy the data they contain if the casing is breached. In theory, then, some form of non-intrusive reading method would be required for such smart cards. One cannot help but wonder if such a non-intrusive reading capability exists in the form of a sensitive instrument that measures a particular property of the physical device at runtime. If this were possible, then even this pseudorandom generator attack would not be secure. The powerful engineer would be able to learn the current seed and hence all future randomness that the device will employ. One can envision a covert operation in which the smart card belonging to an enemy is obtained, read, and then carried back to its place of origin. In this case all future randomness that the device will use would be known to the powerful engineer. This threat model begs the question as to whether a design exists that is secure against this threat. Such an attack is one that can be scrutinized by a reverse engineer and then be redeployed in a way that will remain secure against the reverse engineer.

Another weakness of the PRNG attack revolves around software implementations. Suppose that there exists an on-line server that generates key pairs and issues them to users. The code for the server may be digitally signed and the signature may be verified periodically. This implies that the reverse engineer cannot modify the code after successful reverse engineering without the modification being detected. In the case of the pseudorandom number generator attack, an archived core-dump would reveal an intermediate seed and hence compromise all subsequent private keys that are generated.

The remainder of this chapter describes a kleptographic attack that is robust against the exposure of intermediate seeding material. It is based on a result published in Crypto '96 [333]. The original approach focused on attacking software key generation implementations. The scheme was entitled PAP, meaning pretty-awful-privacy. This was a play on PGP, the well known pretty-good-privacy program that originally utilized RSA [343]. The goal in designing PAP was to come up with a cryptotrojan that could be deployed in a program like PGP that gave the Trojan horse writer an exclusive advantage: the ability to derive the private keys of all users. One of the tricky aspects of this approach is that the Trojan, which is in software, will be duplicated as is along with PGP. This prevents each instance of the Trojan from having unique identifiers. However, it seems that given this restriction it is difficult to arrive at cryptotrojan attacks with provably secure properties.

It has since become clear that the best way to approach the problem is to gear the attack towards hardware implementations such as smart cards. In this situation, secret seeding material can be used in the black-box environment to provide strong security guarantees. It is when the black-box is opened that the fail-safe aspects of the key generation attack take effect. It makes sense to study the problem this way, since it is then straightforward to weaken the black-box assumption to obtain a gray-box assumption. For lack of a better term, a gray-box may be regarded as a box that is difficult to look into but not impossible. A compiled program may be considered to be a gray box with respect to the average user. In so doing, the security against the successful reverse engineer in the black-box setting may be regarded as the security that is provided in the gray-box scenario. In software cryptotrojan attacks, the Trojan can search for a unique identifier in its host at run-time. For example, a fixed IP address or a guessable CPU ID can be used as an identifier. By doing this, a security analysis is formulated that accounts for both hardware and software security settings.

11.3 Probabilistic Bias Removal Method

One of the tools that will be needed for the kleptographic attack on composite key generation is what we call, for lack of a better term, the probabilistic bias removal method (PBRM). The method is reminiscent of the technique used to sample a set uniformly at random given a fair coin. The problem is as follows. Suppose that we have a value x that is drawn uniformly at random from {0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1}. Being kleptographers, we cannot display x as such within the output of a cryptosystem since it is drawn from the wrong set. Suppose that the correct set to draw from uniformly at random is {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}, where S > R >  . Since the correct set is a superset of the wrong set the value x has in effect been drawn from the correct set, but using the wrong probability distribution. That is, x will be one of R, R + 1, ..., S − 1 with probability zero. This bias towards the lower elements must be removed.

. Since the correct set is a superset of the wrong set the value x has in effect been drawn from the correct set, but using the wrong probability distribution. That is, x will be one of R, R + 1, ..., S − 1 with probability zero. This bias towards the lower elements must be removed.

If we could somehow display x in the form of a value x′ that is uniformly distributed in {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}, then the modified version of x will no longer look suspicious. It is required that the value x be easily derivable from x′.

PBRM(R, S, x):

input: R and S with S > R >  and x contained in {0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1}

and x contained in {0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1}

output: e contained in {−1, 1} and x′ contained in {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}

1. set e = 1 and set x′ = 0

2. choose a bit b randomly

3. if x < S − R and b = 1 then set x′ = x

4. if x < S − R and b = 0 then set x′ = S − 1 − x

5. if x ≥ S − R and b = 1 then set x′ = x

6. if x ≥ S − R and b = 0 then set e = − 1

7. output e and x′ and halt

The value −1 indicates failure. It is clear that x is readily obtainable from x′. To see this note that x = x′ unless x′ ≥ R, in which case x = S − 1 − x′. Note that this is a Monte Carlo algorithm. If it fails, a new value for x will have to be chosen.

Lemma 1 Let S > R >  , let x be a value chosen uniformly at random from {0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1}, and let (e, x′) = PBRM(R, S, x). If e = 1 then x′ is uniformly distributed in {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}.

, let x be a value chosen uniformly at random from {0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1}, and let (e, x′) = PBRM(R, S, x). If e = 1 then x′ is uniformly distributed in {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}.

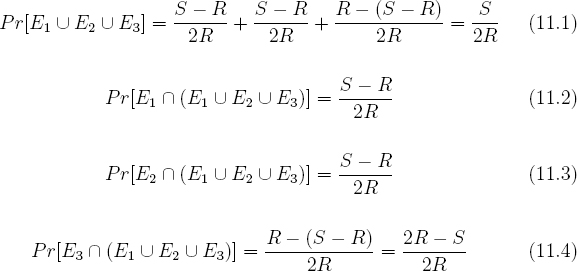

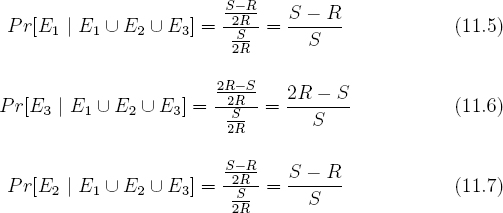

Proof Define E1 to be the event that x < S − R and b = 1. Define E2 to be the event that x < S − R and b = 0. Define E3 to be the event that x ≥ S − R and b = 1. Observe that the probability that a particular x  {0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1} is chosen is

{0, 1, 2, ..., R − 1} is chosen is  .

.

Equations 11.1 through 11.4 give rise to the following three conditional probabilities.

Clearly all values for x′ in the interval [0, S − R) are equally likely. Since there are S − R possible values for x′ in this interval, it follows from equation 11.5 that when event E1 occurs, each value x′ in this interval is chosen with probability  . A similar argument holds for the intervals [S − R, R) and [R, S). It follows that if e = 1 then x′ is uniformly distributed in {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}.

. A similar argument holds for the intervals [S − R, R) and [R, S). It follows that if e = 1 then x′ is uniformly distributed in {0, 1, 2, ..., S − 1}.

This bias removal method is a useful tool to leak secrets out of a cryptosystem in an inconspicuous fashion.

11.4 Secretly Embedded Trapdoors

Recall that the fundamental weakness in the pseudorandom number generator backdoor attack is that once an intermediate seed is exposed, the future operation of the device is compromised (see Subsection 11.2.3). This weakness alone may be enough to prevent smart card companies and designers from ever mounting such an attack. Inserting a deliberate backdoor is a criminal offense that warrants jail time. However, inserting a deliberate backdoor that is exploitable by people other than the malicious designer could lead to serious breaches in national security. The study of robust backdoors is thus of great importance to intelligence agencies and hackers alike.

This problem can be solved by thinking kleptographically. The idea is to use cryptography to construct carefully designed cryptotrojans. These cryptotrojans may be designed into the cryptosystem by a malicious manufacturer, or they may be added to the code by hackers after deployment. Consider the key generation process. A key generation algorithm outputs a private key and a public key to the user. Only the public key gets sent across public networks. So, it is safe to assume that the Trojan horse designer will be able to obtain the public keys that the Trojan generates. This is a communications channel between the device and the attacker. Gus Simmons demonstrated the subversive power of such channels by formally investigating the notion of subliminal channels. If a prime that divides n can be displayed in the binary representation of n then the attacker could factor n. This is the heart of the attack on composite key generation and it is based on the subliminal channel that exists in composite key generation (see Subsection 10.4.5). However, simply placing the prime p in the upper order bits of n would allow anyone to factor n. This implies that p should be asymmetrically encrypted using the public key of the attacker. Hence, cryptography should be employed within cryptography to gain exclusive access to everyone's private keys. This attack was first published in Crypto '96 [333]. It was later refined in Eurocrypt '97 [335]. This attack may be regarded as a cryptotrojan attack since it exploits the fact that key generation algorithms have access to private keys, and since the Trojan uses the public key of the attacker.

It is critical that cryptotrojans not interfere with the normal operation of a device. By definition a subliminal channel has a fixed bandwidth that can be utilized without hindering the device's normal operation. Cryptotrojans that exploit subliminal channels to leak ciphertexts will therefore not hinder the expected behavior of the device. Care must of course be taken to ensure that the subliminal channel is utilized in a covert fashion. The infected black-box cryptosystem must appear normal in every way.

To discover attacks on other cryptosystems one should ask the following questions:

- What are the outputs of the device?

- Does the device exhibit a subliminal channel?

- If so, what is the bandwidth of the channel?

- What can we hide or encode within the outputs of the device without hindering its normal operation and without giving the attack away?

The key generator outputs public keys and so it is in public keys that private keys must be displayed. As a result of the attack, a database of public keys is in fact a database of public keys and ciphertexts that encrypt the corresponding private keys. Only the attacker is able to decrypt these ciphertexts. A cardinal lesson in kleptography is that subliminal channels, wherever present, can be used by cryptotrojans to leak public key encryptions that are computed using the public key of the attacker.

The two basic threats from the attacker's point of view give rise to the following two types of adversaries.

- Distinguishing Adversary: The goal of the distinguishing adversary is to distinguish an honest implementation from a dishonest implementation, assuming that neither of these particular devices has ever been reverse engineered. It is assumed that the distinguishing adversary has successfully reverse engineered one or more devices and obtained their code and obtained the contents of their non-volatile memory. It is assumed that the adversary has access to all public information including public algorithms, public keys, ciphertexts, signatures, and so on.

- Cryptanalyzing Adversary: The goal of the cryptanalyzing adversary is to break the security of a given device that has never been reverse engineered. This may involve factoring a public key, decrypting a public key encryption, forging a signature, and so on. It is assumed that the cryptanalyzing adversary has successfully reverse engineered one or more devices (other than the one in question) and obtained their code and obtained the contents of their non-volatile memory. It is assumed that the adversary has access to all public information including public algorithms, public keys, ciphertexts, signatures, and so on.

For example, a reverse engineer may have reverse engineered one chip and will try to use that information to factor the composite that is output by another chip. When the composites are generated using a kleptographic attack, the reverse engineer should not be able to factor such a composite. This should hold even if the reverse engineer can specify the inputs to the device, for example, the size of the keys that are generated. Even with the ability to adaptively select the inputs and receive the outputs, the reverse engineer should not be able to factor other peoples' composites.

Informally, a SETUP (secretly embedded trapdoor with universal protection) attack is an algorithm that can be embedded within a cryptosystem to leak encrypted secrets within the output of the cryptosystem, often through a subliminal channel that exists in that cryptosystem. This encryption is typically performed using the public key of the attacker that is contained within the cryptosystem. Since the public key is used in a trapdoor one-way function, and since it is secretly embedded within the cryptosystem, the resulting code is referred to as having a secretly embedded trapdoor. The information that is leaked through the cryptosystem is universally protected because even if the cryptanalyzing adversary is given access to the leaked ciphertext, the reverse engineered device (that is, the code for the attack and the attacker's public key), and the contents of the device's non-volatile memory, the ciphertext can only be decrypted by the attacker. This enables the attacker to maintain his or her relative advantage over other users and even successful reverse engineers. SETUP attacks are designed to gracefully handle the possibility of reverse engineering and are designed to be robust against users who try to distinguish honest devices from dishonest ones.

The following is an informal definition of a SETUP.

Definition 4 Let C be an honest black-box cryptosystem that conforms to a public specification. Let C′ be a dishonest version of C that contains a publicly known cryptotrojan algorithm,5 that was implemented by an attacker A, and that may contain secret seeding information that is not publicly known. Cryptosystem C′ constitutes a SETUP version of C if the following properties hold:

- Halting Correctness: C and C′ are efficient algorithms. That is, they must halt in time polynomial in the length of their inputs, and

- Output Indistinguishability: The outputs of C and C′ are indistinguishable to all efficient probabilistic algorithms except for the attacker A who can always distinguish, and

- Confidentiality of outputs of C: The outputs of C are confidential to all efficient probabilistic algorithms and do not compromise the cryptosystem that C implements, and

- Confidentiality of outputs of C′: The outputs of C′ are confidential to all efficient probabilistic algorithms except for the attacker A, and do not compromise the cryptosystem that C′ implements, and

- Ability to compromise C′: With overwhelming probability the attacker A can decrypt, forge, or otherwise cryptanalyze at least one private output of C′ given a sufficient number of public outputs of C′.

Property 2 utilizes the notion of polynomial indistinguishability of probability distributions, a concept that is central to proving the security of various cryptosystems. Properties 2, 3, and 4 can be made more comprehensive by requiring that they hold in an adaptive scenario in which the adversary adaptively chooses the inputs for the device and receives the public outputs. This is analogous to providing security against adaptive chosen ciphertext attacks. It follows that the above definition of a secure backdoor draws from well-studied concepts in modern cryptography.

11.5 Key Generation SETUP Attack

The notion of a SETUP attack was presented at Crypto '96 [333] and was later improved slightly [335]. To illustrate the notion of a SETUP attack, a particular attack on RSA key generation was presented. The SETUP attack on RSA keys from Crypto '96 generates the primes p and q from a skewed distribution. This skewed distribution was later corrected while allowing e to remain fixed6 [341]. A backdoor attack on RSA was also presented by Crépeau and Slakmon [77]. They showed that if the device is free to choose the RSA exponent e (which is often not the case in practice), the primes p and q of a given size can be generated uniformly at random in the attack. Crépeau and Slakmon also give an attack similar to PAP in which e is fixed. Crépeau and Slakmon [77] noted the skewed distribution in the original SETUP attack as well. The specific attack that is given in this section is based on the first author's doctoral dissertation.

When the honest algorithm GenPrivatePrimes1 is implemented in the device, the device may be regarded as an honest cryptosystem C. The advanced attack on composite key generation is specified by the algorithm GenPrivatePrimes3 below. This algorithm is the infected version of GenPrivatePrimes1 and when implemented in a device it effectively serves as the device C′ in a SETUP attack.

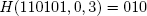

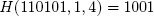

Recall that a random oracle R(·) takes as input a bit string that is finite in length and returns an infinitely long bit string. Let H(s, i, v) denote a function that invokes the oracle and returns the v bits of R(s) that start at the ith bit position, where i ≥ 0. For example, if R(110101) = 01001011110101... then,

and

and so on.

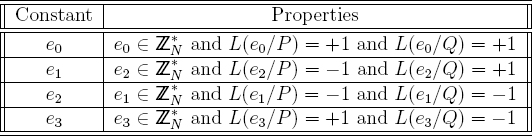

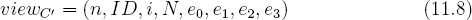

The algorithm GenPrivatePrimes3 contains the attacker's public key N where |N| = W/2 bits, and N = PQ with P and Q being distinct primes. The primes P and Q are kept private by the attacker. The attacker's public key is half the size of p times q, where p and q are the primes that are computed by the algorithm. Each device contains a unique W/2-bit identifier ID. The IDs for the devices are chosen randomly, subject to the constraint that they all be unique. The variable i is stored in non-volatile memory and is a counter for the number of compromised keys that the device created. It starts at i = 0. The variable j is not stored in non-volatile memory. The attack makes use of the four constants (e0, e1, e2, e3) that must be computed by the attacker and placed within the device. These quantities can be chosen randomly, for instance. They must adhere to the requirements listed in Table 11.1.

It may appear at first glance that the backdoor attack below is needlessly complicated. However, the reason for the added complexity becomes clear when the indistinguishability and confidentiality properties are proven. This algorithm effectively leaks a Rabin ciphertext in the upper order bits of pq and uses the Rabin plaintext to derive the prime p using a random oracle.

Note that due to the use of the probabilistic bias removal method, this algorithm is not going to have the same expected running time as the honest algorithm GenPrivatePrimes1(). A standard approach to designing randomized algorithms is to design them to be Monte Carlo as opposed to Las Vegas. That is, the running time is bounded by a fixed polynomial and the failure probability is bounded from above. This guarantees a poly-time algorithm. However, in the case of composite key generation, such an algorithm either outputs (p, q) or failure. If the failure probability is not carefully designed in the attack, it might be possible to distinguish the honest key generator from the dishonest one based on the frequency of the failure output. The ultimate goal in the attack is to make it produce outputs that are indistinguishable from the outputs of an honest implementation. It is easiest to utilize the Las Vegas key generation algorithm in which the only possible type of output is (p, q).

The value Θ is a constant that is used in the attack to place a limit on the number of keys that are attacked. It is a restriction that simplifies the algorithm that the attacker uses to recover the private keys of other users.

Table 11.1 Constants used in key generation attack

input: none

output: W/2-bit primes p and q such that p ≠ q and |pq| = W

1. if i > Θ then output GenPrivatePrimes1() and halt

2. update i in non-volatile memory to be i = i + 1

3. let I be the |Θ|-bit representation of i

4. for j = 0 to ∞ do:

5. choose x randomly from {0, 1, 2, ..., N − 1}

6. set c0 = x

7. if gcd(x, N) = 1 then

8. choose bit b randomly and choose u randomly from

9. if J(x/N) = +1 then set c0 =  mod N

mod N

10. if J(x/N) = −1 then set c0 =  mod N

mod N

11. compute (e, c1) = PBRM(N, 2W/2, c0)

12. if e = −1 then continue

13. if u > −u mod N then set u = −u mod N /* for faster decr. */

14. let T0 be the W/2-bit representation of u

15. for k = 0 to ∞ do:

16. compute p = H(T0||ID||I||j,  )

)

17. if p ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 and p is prime then break

18. if p < 2W/2−1 + 1 or if p is not prime then continue

19. c2 = RandomBitString1()

20. compute n′ = (c1||c2)

21. solve for the quotient q and the remainder r in n′ = pq + r

22. if q is not a W/2-bit integer or if q < 2W/2−1 + 1 then continue

23. if q is not prime then continue

24. if |pq| < W or if p = q then continue

25. if p > q then interchange the values p and q

26. set S = (p, q) and break

27. output S, zeroize everything in memory except i, and halt

It is assumed that the user, or the device that contains this algorithm, will multiply p by q to obtain the public key n = pq. Making n publicly available is perilous since with overwhelming probability p can easily be recovered by the attacker. Note that c1 will be displayed verbatim in the upper order bits of n = n′ − r = pq unless the subtraction of r from n′ causes a borrow bit to be taken from the W/2 most significant bits of n′. The attacker can always add this bit back in to recover c1.

Suppose that the attacker, who is either the malicious manufacturer or the hacker that installed the Trojan horse, obtains the public key n = pq. The attacker is in a position to recover p using the factors (P, Q) of the Rabin public key N. Rabin decryption is described in Appendix C.1.5. The factoring algorithm attempts to compute the two smallest ambivalent roots of a perfect square modulo N. Let t be a quadratic residue modulo N. Recall that a0 and a1 are ambivalent square roots of t modulo N if a20 ≡ a21 ≡ t mod N, a0 ≠ a1, and a0 ≠ −a1 mod N. The values a0 and a1 are the two smallest ambivalent roots if they are ambivalent, a0 < −a0 mod N, and a1 < −a1 mod N. The Rabin decryption algorithm can be used to compute the two smallest ambivalent roots of a perfect square t, that is, the two smallest ambivalent roots of a Rabin ciphertext.

For each possible combination of ID, i, j, and k the attacker computes the algorithm FactorTheComposite given below. Since the key generation device can only be invoked a reasonable number of times, and since there is a reasonable number of compromised devices in existence, this recovery process is tractable.

FactorTheComposite(n, P, Q, ID, i, j, k):

input: positive integers i, j, k with 1 ≤ i ≤ Θ

distinct primes P and Q

n which is the product of distinct primes p and q

Also, |n| must be even and |p| = |q| = |PQ| = |ID| = |n|/2

output: failure or a non-trivial factor of n

1. compute N = PQ

2. let I be the Θ-bit representation of i

3. W = |n|

4. set U0 equal to the W/2 most significant bits of n

5. compute U1 = U0 + 1

6. if U0 ≥ N then set U0 = 2W/2 − 1 − U0 /* undo the PBRM */

7. if U1 ≥ N then set U1 = 2W/2 − 1 − U1 /* undo the PBRM */

8. for z = 0 to 1 do:

9. if Uz is contained in  then

then

10. for ℓ = 0 to 3 do: /* try to find a square root */

11. compute Wℓ = Uzeℓ−1 mod N

12. if L(Wℓ/P) = +1 and L(Wℓ/Q) = +1 then

13. let a0, a1 be the two smallest ambivalent roots of Wℓ

14. let A0 be the W/2-bit representation of a0

15. let A1 be the W/2-bit representation of a1

16. for b = 0 to 1 do:

17. compute pb = H(Ab||ID||I||j,  )

)

18. if p0 is a non-trivial divisor of n then

20. if p1 is a non-trivial divisor of n then

21. output p1 and halt

22. output failure and halt

The quantity U0 + 1 is computed since a borrow bit may have been taken from the lowest order bit of c1 when the public key n = n′ − r is computed.

11.6 Security of the SETUP Attack

The entire proof that this attack constitutes a secretly embedded trapdoor with universal protection will not be given. However, the two non-trivial aspects of this proof will be sketched out. It is stressed that this is a proof in the random oracle model and that when the attack is implemented, it is subject to the weaknesses of the primitive used to instantiate the oracle. The proof that the attack satisfies Property 2 of a SETUP attack will be outlined. It is shown that the primes that are output by the cryptotrojan are computationally indistinguishable from the primes that are output by the honest key generation algorithm. The proof that the outputs are confidential, even against a successful reverse engineer, is then outlined. This is Property 4 of a SETUP attack and it holds using a reduction argument.

11.6.1 Indistinguishability of Outputs

It is assumed that the distinguishing adversary knows the cryptotrojan algorithm. This could be from prior reverse engineering endeavors. Hence, the attacker's Rabin public key N is known to the adversary. Since the adversary has not reverse engineered the particular device in question the adversary does not know the value ID right off the bat.

There is nothing to distinguish when i > Θ, so we will consider the case that i ≤ Θ. The first observation is that indistinguishability does not hold against an adversary that has unbounded computational resources. Such an adversary can factor N and hence knows P and Q. This means that the adversary is capable of decrypting Rabin ciphertexts when they are embedded in the upper order bits of pq. The attacker can guess a value for ID and then invoke the key generation device, say four times. The adversary collects the four pairs of primes that the device outputs. This data set is used to help test if the guess for ID was correct or not. The adversary knows that j will be zero at the beginning of each invocation. The adversary also knows that the values for i will be i, i + 1, i + 2, and i + 3. Since i ≤ Θ can be guessed, the adversary will be able to verify correctly with overwhelming probability whether or not the guess for ID was correct. The adversary can probe the integrity of the device's output values by performing the same computations that the device would do if it were dishonest and comparing the results with the data set. If the values do not match the data set, ID may be guessed again. In time, the computationally unbounded adversary will be able to try all IDs and hence distinguish an honest device from a dishonest one.

The attack is, however, indistinguishable to all adversaries that are polynomially bounded in computational power.7 Let C denote an honest device that uses GenPrivatePrimes1() and let C′ denote a dishonest device that uses GenPrivatePrimes3(). A key observation is that the primes p and q that are output by the dishonest device are chosen from the same set and same probability distribution as the primes p and q that are output by the honest device. So, it will be shown that p and q in the dishonest device C′ are chosen from the same set and from the same probability distribution as p and q in the honest device C.8

First consider the value p. In C, clearly p is chosen randomly from the set of W/2-bit prime numbers due to the first loop. Now consider the device C′. Note that the substring (ID||I||j) is completely unique to the jth iteration in the inner loop of the ith invocation in the unique device that contains ID. Since (T0||ID||I||j) is the argument to the random oracle, this means that this oracle input is different from every other oracle input, even when considering all outermost iterations and all devices. Since the output of R(T0||ID||I||j) is sampled W/2 bits at a time, it follows that p is chosen uniformly at random from all W/2-bit prime numbers in C′. Therefore, C′ generates p from the same set and probability distribution as p in C.

It remains to consider the set and distribution that is used to choose q. In C, clearly q is chosen randomly from the set of W/2-bit prime numbers. Now consider the device C′. If x is not relatively prime to N then c0 is assigned the value x. If x is relatively prime to N, then c0 is set to be a randomly chosen element from  using the four constants e0, e1 e2, and e3. It follows that c0 is a random element of {0, 1, 2, ..., N − 1}. It follows from Lemma 1 that c1 is a random element of {0, 1, 2, 3, ..., 2W/2 − 1}. Hence, c1 is a randomly chosen W/2-bit string. Clearly c2 is a randomly chosen W/2-bit string as well. Due to the concatenation of c1 and c2 it follows that n′ is a random W-bit string.

using the four constants e0, e1 e2, and e3. It follows that c0 is a random element of {0, 1, 2, ..., N − 1}. It follows from Lemma 1 that c1 is a random element of {0, 1, 2, 3, ..., 2W/2 − 1}. Hence, c1 is a randomly chosen W/2-bit string. Clearly c2 is a randomly chosen W/2-bit string as well. Due to the concatenation of c1 and c2 it follows that n′ is a random W-bit string.

Using Euclid's division equation with quotient q and r as the remainder, n′ = pq + r = (2W/2−1 + 1)2 + 0 is the smallest possible value for n′ such that p, q ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1. But this equals 2W−2 + 2W/2 + 1 and is thus a (W − 1)-bit quantity. The greatest possible W/2-bit integer is p = q = 2W/2 −1. So, n′ = pq+r = pq+(p − 1) = (2W/2 − 1)2 + (2W/2 −1) − 1 is the greatest possible value for n′ such that p and q are W/2-bit integers. But this equals 2W − 2W/2 − 1 and is hence a W-bit quantity. This shows that the smallest and largest possible values for n′ = pq + r where |p| = |q| = W/2 and p, q ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 are contained in {0, 1}W. Hence, all values for n′ = pq + r where |p| = |q| = W/2 and p, q ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 are contained in {0, 1}W. It follows that for every pair (p, q) such that |p| = |q| = W/2 and p, q ≥ 2W/2− 1 + 1, there are p values in {0, 1}W that when divided by p yield q as the quotient. Since all n′  {0, 1}W are equally likely, q is chosen uniformly at random from the W/2 bit integers greater than or equal to 2W/2−1 + 1 in C′. Those values for q that are composite will be rejected. Hence, q is chosen uniformly at random from all W/2-bit primes.

{0, 1}W are equally likely, q is chosen uniformly at random from the W/2 bit integers greater than or equal to 2W/2−1 + 1 in C′. Those values for q that are composite will be rejected. Hence, q is chosen uniformly at random from all W/2-bit primes.

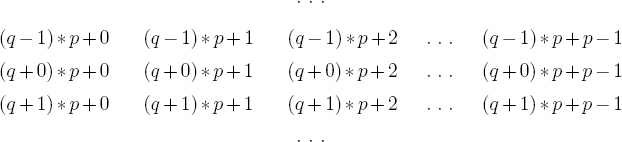

This can be conceptualized as follows. The W/2-bit prime p can be fixed and the space {0, 1}W can be “divided” into regions containing p numbers. A region consists of qp + 0, qp + 1, qp + 2, ..., qp + p − 1. Observe that when each of these values is divided by p the quotient is q. Note also that there are p such values. The regions are the rows below.

A dart can then be thrown at {0, 1}W. Which region if any the dart lands in determines the value of q. Due to acceptance/rejection no region is preferred and exactly one valid region must be selected.

The remaining tests (that make sure that p ≠ q, etc.) are identical in C and C′. Hence, the outputs of C and C′ are drawn from the same set and probability distribution. This implies that the only way to distinguish is to guess the oracle input ID correctly. Since ID is not guessable and since it is kept secret from all adversaries in the black-box cryptosystem C′, it follows that the outputs of C and C′ are indistinguishable to all computationally bounded adversaries.

11.6.2 Confidentiality of Outputs

An important observation is that the security parameter of the attacker's public key is half the value of the security parameter of the public key that is being generated. For instance, if the key being generated is a 1024-bit composite then the attacker's composite is 512 bits in length. This is clearly a risky scenario since if the device is reverse engineered, then the effective security parameter is 512. However, if the key that is generated is 2048 bits, then the attacker's key is 1024 bits. It is possible to modify this attack so that the attacker's public key has a higher security parameter in the SETUP attack. However, such variants will not be discussed here.9

Recall that Property 4 of a SETUP attack (see Section 11.4) is confidentiality against a reverse engineering adversary. In this section a reduction argument is given to prove that Property 4 holds. The claim is that there exists an algorithm that can break the confidentiality of the cryptotrojan attack if and only if there exists an algorithm that can factor efficiently. Clearly if factoring can be broken then there exists an efficient algorithm to break the confidentiality of the cryptotrojan. It remains to show the converse, namely, that if there exists an efficient algorithm that can break the cryptotrojan then factoring is easy.

In a nutshell this is proven by showing that if an efficient algorithm exists that violates the confidentiality property then either W/2-bit composites PQ can be factored or W-bit composites pq can be factored. This reduction is not a randomized reduction, yet it goes a long way to show the security of the cryptotrojan attack.

With regard to confidentiality it is assumed that the computationally bounded adversary has reverse engineered the device in question and hence knows the value for ID that it contains. It is assumed that the device has been reconstituted and redeployed. It is also assumed that the adversary knows the current value for i that exists in the non-volatile memory store of the device. These are very generous assumptions about what the adversary knows.

To prove confidentiality of the dishonest device it is necessary to show that the adversary cannot compute p in n = pq when the adversary has the following view,

The adversary also knows the cryptotrojan algorithm. What the adversary does not have access to is the coin flips that the cryptotrojan will generate once it has been redeployed.

The proof of confidentiality is by contradiction. Suppose for the sake of contradiction that a computationally bounded algorithm A exists that violates the confidentiality property. For a randomly chosen input, algorithm A will return a non-trivial factor of n with non-negligible probability. The adversary could thus use algorithm A to break the confidentiality of the system. Algorithm A factors n when it feels so inclined, but must do so a non-negligible portion of the time.

It is important to first set the stage for the proof. The adversary that we are dealing with is trying to break a public key pq where p and q were computed by the cryptotrojan. Hence, pq was created using a call to the random oracle R. It is conceivable that an algorithm A that breaks the confidentiality will make oracle calls as well to break pq. Perhaps A will even make some of the same oracle calls as the cryptotrojan. However, in the proof we cannot assume this. All we can assume is that A makes at most a polynomial10 number of calls to the oracle and we are free to “trap” each one of these calls and take the arguments.

Consider the following algorithm SolveFactoring(N, n) that uses A as an oracle to solve the factoring problem.

SolveFactoring(N, n):

input: N which is the product of distinct primes P and Q

n which is the product of distinct primes p and q

Also, |n| must be even and |p| = |q| = |N| = |n|/2

output: failure, or a non-trivial factor of N or n

1. compute W = 2|N|

2. for k = 0 to 3 do:

4. choose ek randomly from

5. while J(ek/N) ≠ (−1)k

6. choose ID to be a random W/2-bit string

7. choose i randomly from {1, 2, ..., Θ}

8. choose bit b0 randomly

9. if b0 = 0 then

10. compute p = A(n, ID, i, N, e0, e1, e2, e3)

11. if p < 2 or p ≥ n then output failure and halt

12. if n mod p = 0 then output p and halt /* factor found */

13. output failure and halt

14. output CaptureOracleArgument(ID, i, N, e0, e1, e2, e3) and halt

CaptureOracleArgument(ID, i, N, e0, ei, e2, e3):

1. compute W = 2|N|

2. let I be the Θ-bit representation of i

3. for j = 0 to ∞ do: /* try to find an input that A expects */

4. choose x randomly from {0, 1, 2, ..., N − 1}

5. set c0 = x

6. if gcd(x, N) = 1 then

7. choose bit b1 randomly and choose u1 randomly from

8. if J(x/N) = +1 then set c0 =  mod N

mod N

9. if J(x/N) = −1 then set c0 =  mod N

mod N

10. compute (e, c1) = PBRM(N, 2W/2, c0)

11. if e = −1 then continue

12. if u1 > −u1 mod N then set u1 = −u1 mod N

13. let T0 be the W/2-bit representation of u1

14. for k = 0 to ∞ do:

15. compute p = H(T0||ID||I||j,  )

)

16. if p ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 and p is prime then break

17. if p < 2W/2−1 + 1 or if p is not prime then continue

18. c2 = RandomBitString1()

19. compute n′ = (c1||c2)

20. solve for the quotient q and the remainder r in n′ = pq + r

21. if q is not a W/2-bit integer or if q < 2W/2−1 + 1 then continue

22. if q is not prime then continue

23. if |pq| < W or if p = q then continue

24. simulate A(pq, ID, i, N, e0, e1, e2, e3), watch calls to R, and store the W/2-most significant bits of each call in list

25. remove all elements from  that are not contained in

that are not contained in

26. let L be the number of elements in

27. if L = 0 then output failure and halt

28. choose α randomly from {0, 1, 2, ..., L − 1}

29. let β be the αth element in

30. if β ≡ ±u1 mod N then output failure and halt

31. if β2 mod N ≠ u21 mod N then output failure and halt

32. compute P = gcd(u1 + β, N)

33. if N mod P = 0 then output P and halt

34. compute P = gcd(u1 − β, N)

35. output P and halt

Note that with non-negligible probability A will not balk due to the choice of ID and i. Also, with non-negligible probability e0, e1, e2, and e3 will conform to the requirements in the cryptotrojan attack. So, when b0 = 0 these four arguments to A will conform to what A expects with non-negligible probability. Now consider the call to A when b0 = 1. Observe that the value pq is chosen from the same set and probability distribution as in the cryptotrojan attack. So, when b0 = 1 the arguments to A will conform to what A expects with non-negligible probability. It may be assumed that A balks whenever e0, e1, e2, and e3 are not appropriately chosen without ruining the efficiency of SolveFactoring. So, for the remainder of the proof we will assume that these four values are as defined in the cryptotrojan attack.

Let u2 be the square root of u12 mod n such that u2 ≠ u1 and u2 < −u2 mod n. Also, let T1 and T2 be u1 and u2 padded with leading zeros as necessary such that |T1| = |T2| = W/2 bits, respectively. Denote by E the event that in a given invocation algorithm A calls the random oracle R at least once with either T1 or T2 as the W/2 most significant bits. Clearly only one of the two following possibilities hold:

- Event E occurs with negligible probability.

- Event E occurs with non-negligible probability.

Consider case (1). Algorithm A can detect that n was not generated by the cryptotrojan by appropriately supplying T1 or T2 to the random oracle. Once verified, A can balk and not output a factor of n. But in case (1) this can only occur at most a negligible fraction of the time since changing even a single bit in the value supplied to the oracle elicits an independently random response. By assumption, A returns a non-trivial factor of n a non-negligible fraction of the time. Since the difference between a non-negligible number and negligible number is a non-negligible number it follows that A factors n without relying on the random oracle. So, in case (1) the call to A in which b0 = 0 will lead to a non-trivial factor of n with non-negligible probability.

Now consider case (2). Since E occurs with non-negligible probability it follows that A may in fact be computing non-trivial factors of composites n by making oracle calls and constructing the factors in a straightforward fashion. However, whether or not this is the case is immaterial. Since A makes at most a polynomial number of calls11 to R the value for L cannot be too large. Since with non-negligible probability A passes either T1 or T2 as the W/2 most significant bits to R and since L cannot be too large it follows that β and u1 will be ambivalent roots with non-negligible probability. Algorithm A has no way of knowing which of the two smallest ambivalent roots SolveFactoring chose in constructing the upper order bits of pq. Algorithm A, which may be quite uncooperative, can do no better than guess at which one it was, and it could in fact have been either. Hence, SolveFactoring returns a non-trivial factor of N with non-negligible probability in this case.

It has been shown that in either case, the existence of A contradicts the factoring assumption. So, the original assumption that adversary A exists is wrong. This proves that the cryptotrojan satisfies Property 4 of a SETUP attack.

Immediately following the test for p = q in C and in C′ it is possible to check that gcd(e, (p − 1)(q − 1)) = 1 and restart the entire algorithm if this does not hold. This handles the generation of RSA primes by taking into account the public RSA exponent e. This preserves the indistinguishability of the output of C′ with respect to C.

11.7 Detecting the Attack in Code Reviews

Since the attack is indistinguishable in black-box implementations, the only way to detect its presence is to analyze what is in the black box.12 This, of course, implies that the black box can be breached and the assumption broken. However, it is naive to think that the attack can be detected by analyzing the code for GenPrivatePrimes1() alone. The reason for this is that the attack can be carried out at a lower level, for example, in a random number generation routine.

For concreteness, consider a dishonest version of RandomBitString1 called RandomBitString2. Rather than choosing strings perfectly at random, it utilizes GenPrivatePrimes3 to arrive at output values. This may be accomplished as follows. GenPrivatePrimes3 is invoked to obtain the compromised values p and q. It then generates a series of perfectly random W/2-bit strings that it will utilize in the next set of outputs. The length of this series is determined as follows. The series terminates when exactly two values that satisfy the requirements for p and q in GenPrivatePrimes1 are found. Hence, the last value is the prime q. These two primes are then thrown away and replaced by the primes that were output by GenPrivatePrimes3 to obtain the actual series. Each time that RandomBitString1 is invoked it outputs the next value in the series. When the series is exhausted it mounts the attack again.

So why will this attack work? Observe that when GenPrivatePrimes1 invokes RandomBitString2 over and over, it will be going through the carefully chosen series of W/2-bit strings. As a result it will arrive at the compromised values for p and q since they are the first two satisfactory primes. The reason why the series was chosen as such was to prevent arousing any suspicion in GenPrivatePrimes1. Observe that the compromised primes p and q occur with the exact same frequency that one would expect from an honest random number generator RandomBitString1.

There is a terribly important message here for security practitioners that perform code reviews. A SETUP attack can be implemented at any level prior to the private key p and q being output by the key generation device. The attack could even occur within the casing that houses the source of physical randomness. Detecting a SETUP attack is an extremely involved process in practice and requires a generous amount of time as well as full and complete disclosure of all algorithms and schematic diagrams to truly rule out the possible existence of backdoors.13

This issue is of particular importance when company A hires company B to do a code review. Very often company A will have some form of flagship product or service that performs random number generation or key generation. They have a vested interest in their product or service being viewed in a positive light by the general public. It is not uncommon for such companies to (1) hire company B that is well known for performing high-quality software reliability and security reviews, (2) assign their own developers as points of contact for company B, and (3) expect to derive a press release that states how amazing their product or service is. This is a recipe for disaster. The points of contact are in a precarious position. Giving the code to real software experts often make them very nervous, and justifiably so. Any bug, error, or fault that is found will imply a mistake on their part. Simply put, they don't want company B to find anything and will often take measures to prevent them from finding anything. As a result they will often try to deliver as little code as possible for the review. A SETUP attack cannot be detected at all unless all code and schematic diagrams are provided to company B by company A.14

Corporations charged with deploying smart cards as well as foreign information ministries need to pay particular attention to these backdoor attacks. When a tiger team is handed a smart card and its PIN and is asked to detect whether or not a backdoor exists, they will not be able to do so. A properly implemented SETUP attack cannot be detected under any circumstances. Such a SETUP attack would have to take into account timing analysis, differential power analysis, and so on, and be implemented accordingly.

Totalitarian governments are in an ideal position to force their populace to utilize smart cards. The rationale behind outfitting the people as such is manyfold. For one, in some countries women are not permitted to leave the country without the permission of their husbands or fathers. One can envision a situation in which a married woman cannot leave the country without a digitally signed form from her husband. In the event that a monarchy contracts the implementation work to a foreign corporation, the corporation or the vendor they choose would be in an ideal position to mount SETUP attacks in the smart cards that are sent.

To make matters worse, the cryptotrojans could be placed in only half the delivered devices, thereby confounding the detectability even under reverse engineering. These backdoors could allow foreign agents to masquerade as any given citizen. It behooves foreign information ministries and ordinary citizens alike to learn exactly what cryptographic algorithms they are using in black-box devices, since the migration to cryptographic machinery can actually weaken authentication checks in certain circumstances.

11.8 Countering the SETUP Attack

To avoid this attack, the following heuristic can be used to generate composite keys. It is based on the SETUP attack itself with some obvious modifications.

GenPrivatePrimes4():

input: none

output: W/2-bit primes p and q such that p ≠ q and |pq| = W

1. for j = 0 to ∞ do:

2. generate s1, s2, c2 to be random W/2-bit strings

3. compute c1 = H(s1, 0, W/2)

4. for k = 0 to ∞ do:

5. p = H(s1||s2,  , W/2)

, W/2)

6. if p ≥ 2W/2−1 + 1 and p is prime then break

7. compute n′ = (c1||c2)

8. solve for the quotient q and the remainder r in n′ = pq + r

9. if q is not a W/2-bit integer or if q < 2W/2−1 + 1 then continue

10. if q is not prime then continue

11. if |pq| < W or if p = q then continue

12. set S = (p, q, s1, s2, k) and break

13. output S, zeroize all values in memory, and halt

The general public can verify that the SETUP attack has not been performed on a given modulus. This can be done by checking that either H(s1, 0, W/2) or H(s1, 0, W/2) + 1 equals the W/2 uppermost bits of n. Here the +1 accounts for a potential borrow bit having been taken from c1. The problem with publishing s1 is that it can constitute a subliminal channel by itself. So, ideally the private key owner and possibly a certification authority should perform this check. The private key owner should always keep (p, q, s2, k) secret.

The seed s2 is for the benefit of the owner of p and q. A heuristic way to check that p was generated using H is to verify that the prime p is equal to H(s1||s2,  , W/2) and that a smaller value for k does not make H(s1||s2,

, W/2) and that a smaller value for k does not make H(s1||s2,  , W/2) a prime that is greater than or equal to 2W/2−1 + 1. The goal is to force devices that implement this algorithm to first commit to s1 in the upper order bits of n and then commit to s2 in the prime p. This method is not perfect since about O(log (log(n))) bits can still be leaked in n using brute force key generation.

, W/2) a prime that is greater than or equal to 2W/2−1 + 1. The goal is to force devices that implement this algorithm to first commit to s1 in the upper order bits of n and then commit to s2 in the prime p. This method is not perfect since about O(log (log(n))) bits can still be leaked in n using brute force key generation.

It should be noted that this defense only protects against the particular SETUP attack described above. In general, it is not clear that the aforementioned attack that uses a pseudorandom tape tp for key generation can be avoided at all without resorting to an interactive form of key generation. It is well known that many subliminal channels can be foiled by relying on protocols in which a trusted party influences every random value that is derived. For RSA key generation in particular, a protocol has been given that allows for verifiable randomness [147]. In this protocol, the user and the CA (a trusted third party) generate a key pair for the user and the CA does not learn the private key. At the end of the protocol the CA is convinced that the key pair has the correct form, that it is randomly chosen, and that its randomness was influenced by the CA's coin tosses. It is mentioned that this protocol can be conducted using two independently designed implementations that communicate with each other to foil kleptographic attacks. For example, one peripheral device can act as the “user” and another peripheral can act as the trusted third party in the protocol. This is a promising direction for guarding against kleptographic attacks.

For non-interactive key generation, one can try to separate the source of randomness from the key generation algorithm, and users can verify the operation of the deterministic portion of the whole key generation process at most only polynomially many times. However, the deterministic key generation device may in fact have a secret on-board random number generator that it uses in a given invocation with inverse-polynomial probability. Hence, the resulting deterministic key generator may in fact be a probabilistic poly-time Turing machine that mounts randomized SETUP attacks infrequently. It then becomes a game for the manufacturer to see how many invocations he or she can compromise without being detected. It is a game because detecting the attack amounts to choosing a large enough polynomial to represent the number of output values that are analyzed. The manufacturer can always choose a larger polynomial for its inverse-polynomial attack probability.

A more general heuristic can be applied to any scenario involving a randomized algorithm. The device can choose a seed s1 randomly, and use the oracle output R(s1) as the random tape in the probabilistic Turing machine. The device outputs its normal computation along with s1. Given s1, a verifier can check the output against the advertised algorithm that the device is said to implement. This applies to cryptographic algorithms and in fact all randomized algorithms. For example, when Quicksort is implemented in hardware this approach can be used to help verify its operation. However, this approach still suffers from the possibility that the device will operate in a Byzantine fashion some of the time.

11.9 Thinking Outside the Box

Side channel analysis is another approach that can be used to attempt to steal private keys and other private information from smart card implementations. Side channels are outside the box attacks that seek to derive sensitive information from a cryptosystem based on the operating characteristics of the device. Devices are real machines and they use power, give off heat, and take a certain amount of time to run based on the particular parameters used in the cryptosystem.

Kocher presented timing attacks against public key cryptographic algorithms [159]. Kocher's result was in fact presented in the same session in Crypto '96 as the original SETUP attack on RSA. Timing attacks apply to both software as well as hardware cryptographic implementations. They exploit the fact that different private keys cause measurably different running times in many cryptographic algorithms whenever they are implemented in a straightforward fashion. It was shown that cryptographic operations need to be buffered to make them have indistinguishable running times irrespective of which particular private keys are used.

Power analysis is another form of side-channel analysis that seeks to derive secret key information from hardware based cryptosystems. It has been shown that for certain algorithms, by measuring the power consumption of devices during their operation it may be possible for the attacker to deduce private key information from the device [26, 160].

These side channels show that it is not sufficient in practice to rely entirely on abstract models of computation such as probabilistic Turing machines to develop secure cryptographic devices. To put it another way, formal proofs of security are necessary but not sufficient in achieving real-world security. Side channel attacks are very important to consider when developing real-world cryptographic machinery and are currently receiving a lot of attention by the research community.

11.10 The Isaac Newton Institute Lecture

The idea of a SETUP attack grew out of our research on cryptovirus attacks. The discovery resulted from the following question that we asked ourselves: what if the file that is asymmetrically encrypted by the virus resides inside a cryptosystem? The notion of hiding data in relation to a cryptosystem immediately suggested that subliminal channels should be considered. At the time, I was well aware of the notion of a subliminal channel. However, Adam had never heard of this notion and ended up rediscovering the concept by chancing upon the subliminal channel in RSA composites. I referred Adam to Simmons' work and Yvo Desmedt's work on abuses in cryptography [89] and he learned that both the notion of a subliminal channel as well as the particular channel in composites was far from new. However, leaking asymmetrically encrypted data through these channels was new, and together we articulated the result in Crypto '96, taking care to appropriately relate the discovery to previous work on information hiding.

Upon investigating the SETUP attack on RSA key generation it became clear that by combining public key cryptography with subliminal channels, very powerful backdoors could be implemented in cryptosystems. The idea is to take a cryptosystem that exhibits a subliminal channel, and plant a cryptotrojan inside it. The payload of the cryptotrojan leaks asymmetric ciphertexts through the subliminal channel in the cryptosystem. To prevent the subliminal attack from being found, two things became readily apparent. It is necessary that the cryptosystem be a black-box to hide the presence of the Trojan, and it is necessary that users not be able to detect when the subliminal channel is being used. This latter consideration suggested that it wasn't enough to rely on the fact that outputs look normal. The notion of polynomial indistinguishability was well known to us. So, the most obvious threat model to use was that of a probabilistic poly-time adversary that tries to distinguish honest cryptosystem outputs from those that result from the cryptotrojan.

The discovery showed that in addition to cryptovirus extortion attacks, public key cryptography proved to be an invaluable tool for stealing private keys secretly. It showed that even more cryptographic notions and techniques could be applied to subvert computer systems. In particular, the notion of polynomial indistinguishability became critical for formally proving the security of the backdoor. It was the combination of data theft and strong cryptographic techniques that led to the term kleptography, which I coined.

In 1996 the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences at the University of Cambridge held a year-long program on Computer Security, Cryptography, and Coding Theory. I was invited to attend and stayed there from January to February. Adam and I agreed that this was a good time to present our findings on SETUP attacks to the greater research community.

As it turns out, Gus Simmons was present at the Isaac Newton Institute when I arrived. I met with him and mentioned that I had some results that might be of interest to him since they were closely related to his work on subliminal channels. One afternoon I went to his office and conveyed the ideas to him, and he absorbed them in their entirety. I later gave a talk that covered the attack on RSA key generation, and found myself having to explain a number of times at the board the specifics behind how the private key is encoded within the bit representation of the corresponding public key itself.

I remember a few reactions that I hope I will not misrepresent, since this all happened some time ago. Whitfield Diffie was in the audience and was carefully listening to every word I said. He explained that for years he had been telling people that the only way that cryptosystems can be trusted is by implementing them in hardware that is thoroughly tested. One of the key rationales behind this is that when the code is in read-only memory, it cannot be tampered with. He remarked that in light of the SETUP attack, this wisdom is flawed. Diffie added that the attack shows that the trust of the user must be placed in the manufacturer instead of the device. If I remember correctly I nodded my head and found that he truly understood the implications of this threat.

In response to the lecture, Peter Landrock (who was then at the University of Aarhus but has since joined Cryptomatics) commented, “You guys have really vicious minds.”

Whereas in other scientific forums this sort of statement might have been insulting, I interpreted it as the highest form of compliment.

He then added, “You take the mathematical notion of public key crypto and apply it to do such nasty things.”

“Yes,” I responded, “that is exactly right.”

I later e-mailed Adam a short note of encouragement and mentioned that the overall gist of our work was both clearly understood and well received by several distinguished cryptographers. At no time during my stay did I mention the fact that the idea was derived from a cryptovirus extortion attack. It seemed prudent to let the research community digest these attacks one at a time so that the software industry would have a chance to build defenses, and so that I would not develop a reputation as a renegade cryptographer. Adam and I deferred explaining these attacks in a comprehensive fashion until now.

1That is, a probabilistic poly-time Turing machine that may or may not utilize the random tape.

2For example, stored according to RSA's PKCS #12 format.

3Figure 4.10 in Stinson details the factoring algorithm that works given the decryption exponent [293].

4In some reasonable parameter.

5For example, that may be obtained by successful reverse engineering, or using the algorithm from this chapter.