Chapter 2

Cryptovirology

The digital realm is a truly magical one indeed. Where else can an object be conjured out of thin air, be teleported across vast distances, be duplicated in its exact form, be rendered invisible at the blink of an eye, and be cast back into oblivion?

Professor Matt Blaze bounded from one end of the chalkboard to the other scrawling the words “multilevel security” as he went. When he finished he turned to face the class and waited patiently as the students distributed the handouts to each other. He rubbed his eyes under his glasses and then glanced at his cell phone, the same cell phone that Customs gave him such a hard time about when he went on a trip to the Caribbean. Apparently it was suspected as being a high-tech encryption device, an article considered to be munitions under ITAR regulations. The fact that customs was suspicious is not surprising given the nature of his research. If you were a cryptographer you'd recognize him on sight for his contributions to the field, and if you weren't you would be certain due to his outward appearance that he could dismantle and reassemble a computer system at a glance. He just had that intelligent, computer-savvy look about him.

When I received my copy I looked at it and couldn't wait to read it. In the center of the page was a mug shot of the infamous hacker Kevin Mitnick. It was a clip from the morning paper, and before diving into the theory of secure operating systems Matt took the time to discuss the truly historic events that were unfolding outside of the classroom. Tsutomu Shimomura was hot on the trail of Kevin Mitnick and Matt made a point of keeping us informed of the events as they occurred. Having already read The Cuckoo's Egg [294] and Cyberpunk: Outlaws and Hackers on the Computer Frontier [127], I appreciated both the significance and difficulty involved in tracking such a notorious hacker. The combination of news discussions and spellbinding lectures captivated the class and created a general feeling that we were all a part of something larger than ourselves in that Fall '95 course on computer security.

Matt's enthusiasm towards computer security was contagious, and the topics on his syllabus were fascinating: multilevel security, public key cryptography, zero-knowledge protocols, just to name a few. He brought in several guest lecturers to add to his presentations. Among them were Jack Lacy and Joan Feigenbaum. Matt, Jack, and Joan were from AT&T, a baby Bell that descended from Ma Bell. In 1984 the federal government forced Ma Bell, then a solitary goliath in the telecom industry, to break up. To many the mere mention of Ma Bell still conjures up visions of old men pacing the corridors and ramparts of Bell Labs with staves in hand, contemplating technologies that would take decades to reach maturity.

Jack Lacy discussed the cryptographic library called CryptoLib that he helped to develop [166]. His lecture covered the library and the algorithms that it used. Only later did I learn how advanced the library was in comparison to the GNU projects' multiprecision library, GNUmp. To implement modular exponentiation, Cryptolib utilizes Karatsuba multiplication, Montgomery reduction, and vector addition chains. Also, in the case that the multiplicands are identical, a well-known squaring speed-up is utilized. At that time GNUmp did not incorporate all of these algorithms. The lecture covered many aspects of algorithmic number theory, and showed just how involved the programming can get when implementing cryptographic primitives.

Lacy went on to describe the random number generator used in CryptoLib called truerand. The truerand algorithm exploits the fact that most motherboards come equipped with two crystal timing devices. One crystal is used to generate the real-time clock signal and the other is used to generate the CPU clock signal. The CPU crystal operates at a much higher frequency than the clock crystal. Truerand pits these two oscillators against each other and extracts randomness based on their discrepancies.

Truerand operates as follows. Initially, a global Boolean flag F is set to false and a local variable i is set to zero. Then, the address of a call-back function is passed as an argument to an operating system call that sets an alarm. The alarm is set to go off in one tick.1 The call-back function sets F to true and then terminates. After the operating system call is made, a while loop is entered in which i is incremented by one in each iteration. The loop terminates only when F is set to true, which occurs when the call-back function is invoked by the operating system. The key to the operation of truerand is that it will not always take exactly one tick for the timer to go off, and hence the number of increments of i is dictated by the number of CPU instructions executed within that time. In theory, the inconsistencies in the total number of CPU instructions executed until the alarm goes off will be reflected most in the least significant bits of i. In multitasking operating systems great care must be taken to verify that the counter gets incremented a sufficient number of times.

Joan Feigenbaum gave a lecture on zero-knowledge interactive proofs (ZKIP). A ZKIP is a protocol that allows a prover to convince a verifier of some fact without revealing why the fact is true to the verifier [118]. For example, there exists a ZKIP that allows a prover to prove that n = pq is the product of two primes without revealing either prime p or q to the verifier. A zero-knowledge proof of knowledge is similar to a ZKIP, however, it also proves that the prover knows some fact, for example, the prime p in n = pq. The fact that the prover knows this prime implies that the prover can write it down. There are numerous ways to utilize such protocols to make computer systems more secure. In the military, a fighter pilot needs to be able to identify an inbound warplane as being a friend-or-foe. This can be accomplished by assigning to each fighter pilot a unique composite n. Each pilot can be ordered to prove knowledge of the factorization of his or her own value n when approaching another aircraft. ZKIPs are ideal friend-or-foe protocols since they reveal nothing to the enemy over the airways that would allow the enemy to impersonate friendly craft in the future.

In computer authentication systems, ZKIPs operate in much the same way. The user wants to be able to prove his or her identity to the computer system without revealing any information that would allow a hacker to impersonate the user at a later time. The zero-knowledge aspect of the proof implies that a password-snatching Trojan will be unable to collect information that will enable the Trojan horse author to impersonate the user. This holds true even if the Trojan observes every single log on that takes place. Due to the slow but sure introduction of smart card technology, the days in which users authenticate to sensitive systems using passwords are undoubtedly numbered.

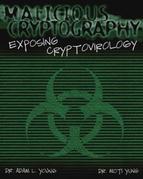

Perhaps one of Matt's most interesting lectures was the one covering the elegant symmetric cipher called TEA. Whereas most ciphers are designed to be both fast and secure, the Tiny Encryption Algorithm [317] was specifically designed to be tiny as well. This has the benefit of taking up less disk space, less random access memory, and so on, since the algorithm itself is so small. Matt indicated in his lecture that anyone who could break TEA would have a result worthy of scientific publication. To prod his students into actually thinking about the problem he gave out an intriguing assignment. He asked us to figure out the TEA decryption algorithm given only the encryption algorithm.

The reason that breaking TEA is such a challenge is that it is a full-fledged 32-round Feistel cipher.2 So, the almighty gauntlet had been thrown down. But, rather than beating my brain against a wall trying to investigate how to break TEA, I decided instead to investigate how to use TEA to attack computer systems. I marveled at and extolled its compactness and strength. It is ideal for incorporation into code that's not supposed to be there. When the lecture ended I headed out for a bite to eat with the revised challenge foremost in my mind.

My favorite haunt between classes was Amsterdam Pizza, located directly across from the Columbia University engineering building. There is a certain comfort to walking into an eatery, getting food, and sitting down without breathing a word. It is a courtesy extended only to true regulars. Smiling at the cashier, I took my slices and soda and sat down at a small table.

While looking past the line of people to the avenue beyond, I contemplated TEA. Never had I dreamed that such a strong cipher could be implemented in four lines of C code. The fact that it constituted a full-fledged Feistel cipher while being so compact was impressive indeed. It seemed that there had to be some novel application of TEA to computer viruses. Most viruses use trivial encryption techniques such as repeated XOR encryption to hide their code. This form of encryption uses a randomly chosen key over and over to encipher the bulk of the virus, and is not secure since the key is reused.3 It became apparent that TEA possesses the potential to make polymorphic viruses much harder to detect. The tiny decryption algorithm could be used in the decryption header and the body of the virus could be encrypted using a strong Feistel cipher.

Figure 2.1 Extended Tiny Encryption Algorithm

I then turned my attention from defensive applications to offensive applications of TEA. Having read about the One-half virus, I wondered if TEA could make virus attacks more devastating. The One-half virus uses encryption to render information on the hard disk inaccessible. The virus stores the decryption keys in the partition table on the infected machine. When the virus is in memory, it decrypts the data when it is accessed so that the user will not notice that the encryption occurred [123]. The novelty behind this attack is that it integrates the virus with its host to a certain degree. However, since the key can be extracted by specially designed software and the encrypted data can be decrypted, the attack is somewhat weak. Therefore, the attack really only contributes one more hurdle to the disinfection process.

It would be possible to modify the One-half virus so that it never decrypts the host information. The decryption algorithm could be removed from the One-half virus in an attempt to give the virus writer an exclusive advantage over the victim: since only the virus writer knows the decryption algorithm, only the virus writer can restore the data. However, this logic is flawed since, as illustrated by Matt's homework assignment, it is often possible to derive the decryption algorithm from the encryption algorithm alone.

Alternatively, a virus could be designed to encrypt the data using TEA and then throw away the key as a means of destroying the data. But a much stronger attack is to simply delete the data. It was apparent that the compactness of TEA would not improve the attack carried out by the One-half virus.

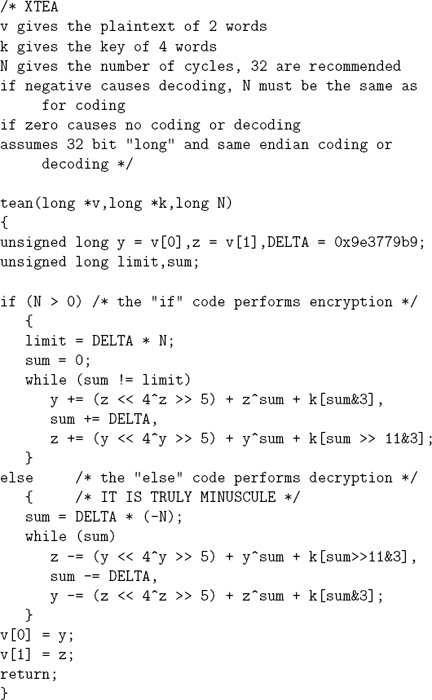

The One-half virus is a perfect illustration of the Achilles heel of viruses. The vulnerability of viruses lies in the fact that they are inherently scrutable once found. Using the model of computation known as a Turing machine, a virus can be viewed as a state-transition table and a starting state. When an antiviral analyst gets a hold of a virus, the analyst learns the table and starting state and therefore learns the operations that the virus is programmed to perform.

It was at this point in time that the improvement to the One-half virus became clear.4 The attack carried out by the One-half virus is repairable for the simple reason that the view of the virus writer and the view of the antiviral analyst are symmetric (see Figure 2.2).

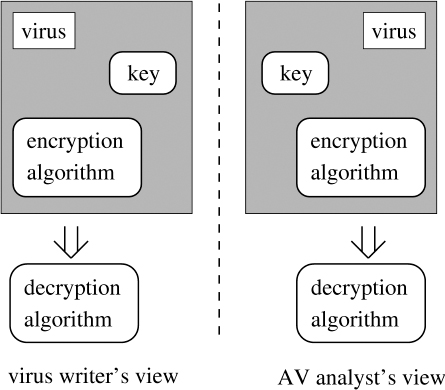

It was the word symmetric that triggered the realization. The key needed to be removed from the antiviral analyst's view but not from the virus writer's view. This would make the views asymmetric. Matt had recently given a lecture on asymmetric cryptography, also known as public key cryptography. It became immediately apparent that by using asymmetric cryptography the views could be made asymmetric.

In this new attack, a public key cryptosystem such as RSA [245] is used in the payload of the virus. The virus author generates an RSA key pair specifically for the purpose of mounting the virus attack. The key pair is generated once and for all before the virus is deployed. The public key is placed within the virus and the corresponding private key is not placed in the virus. The private key is kept secret by the author. The viral payload may be triggered by a particular event or date, for instance. The payload encrypts critical host data using the public key, thereby taking the data hostage. From the definition of a public key cryptosystem, it is not possible to derive the private key from readily available information such as the public key, which may be extracted from the virus. As a result antiviral analysts will not be able to determine the private key from the virus5 (see Figure 2.3). If there are no backups, then only the virus author will be able to restore the encrypted data because only the virus author knows the needed RSA private decryption key.

Only later did it truly sink in that it was the notion of computational intractability that made the virus so powerful. When the virus is scrutinized by an antiviral analyst the RSA public key (e, n) will be found where e is the public exponent and n is the product of two primes p and q. However, no matter how carefully n is studied it will not reveal its prime factors p and q, thereby breaking the symmetry.6 For the victim to recover all of the lost data without the involvement of the virus writer and without backups, the victim would have to break RSA.

That evening the idea thoroughly congealed in my mind and I considered the best course of action. The idea had a definite academic ring to it since it fell squarely into the category of denial-of-service attacks which are attacks that deny one or more users access to computer resources. The attack is a form of denial-of-service since in the absence of backups the host can no longer access the encrypted data. But, this attack had a twist to it. Since the data can be restored using the private key, the attack was suitable for extortion.

Figure 2.2 Symmetric views of the virus

The computer science department offers an optional master thesis course that is geared towards students who want to pursue a particular research topic. It seemed to me that this discovery merited a master's thesis, but in the end the decision would ultimately fall on the shoulders of a faculty member. It had the potential of killing two birds with one stone: develop a prototype while satisfying course credits towards the degree. The challenge, then, was to solicit the involvement of an Ivy League faculty member to help investigate a computer virus with an unprecedented payload.

On the following day, a staff member of the computer science department named Alice Cueba took the time to assist me in seeking a thesis advisor for the idea. Alice knew all the visiting professors as well as all the full-time faculty members, some of whom were on sabbatical. She has seen more undergraduates and graduates through their educational careers than I can imagine, and I knew that if anyone could pull some strings to find someone willing to get involved in this questionable research topic it was she. Alice spoke with Professor Galil and together they suggested that I contact Professor Blaze and a guest of the department named Moti Yung. At the time Moti was a researcher at the IBM T. J. Watson Research Center. Soon after I met Moti for the first time, and I will never forget the encounter.

Figure 2.3 Asymmetric views of the virus

Fear gripped me as I approached his office. The idea had already been laid bare via e-mail and his true intentions for the meeting could not be ascertained. Academia is riddled with burnouts, student-haters, and petty thieves of ideas, so I had no idea what to expect. For the first time in my life I had opted to come clean with a hacking idea and it felt like I was confessing to something that I hadn't even done. Would he belittle the idea? Would he publish it himself? Would he interrogate me about my past history and then seek my expulsion through the Dean's office? The answer to all these questions was no. Amid walls of books and mountains of papers Moti addressed me as a would-be peer and had me utterly disarmed within an hour. . . .

* * * * *

When Adam first set foot in my office it was immediately clear that he was on a mission of some sort. He was shifty-eyed and sat at the very edge of his seat. On occasion he would look over his shoulder to see if anyone was listening to him, and he appeared ready to bolt out of my office at the slightest provocation. It wasn't as though he seemed guilt-ridden or anything. Yet there was an unmistakable tinge of something that weighed heavily on his conscience. In all likelihood it was the disclosure of the idea that made him feel uneasy rather than my affiliation with the computer science department. After all, I was a stranger to him and he had openly admitted via e-mail that he was interested in researching ways of taking other people's data hostage, literally.

I did what I could to put him at ease. I made no sudden movements7 and began by asking him rather mundane questions such as how long he had been at Columbia and who his faculty advisor was. He replied by saying that he'd been there for a year and that Steven Feiner was his advisor. We talked briefly about Feiner's work in computer graphics, and the conversation slowly moved on to the city of Manhattan, and then onto where Adam did his undergraduate studies. Overall it seemed as if Adam wasn't quite sure what he was getting himself into, but on some level it appeared as though he believed he was doing the right thing.

What Adam did not realize was that I was already interested in attacks on computer systems. It is from such threats that security requirements are identified, and they stimulate the development of new and improved models and tools for securing computer systems. I welcomed the opportunity to talk with him about computer viruses, since I had predicted long ago that they will become increasingly vicious, dynamic, and virulent. Viruses were the primary motivation for an earlier work that I did with Ostrovsky on how to withstand mobile virus attacks [215]. This threat model grew into what is now known as the proactive security model, which allows for dynamic and non-monotone corruption of machines on a network. Researchers have to be at least one step ahead of the game in order to safely handle new attacks. This belief suggests that novel threats have to be exposed, through scientific publications, conferences, and so forth, so that the necessary infrastructures are developed. Several questions had occupied my mind upon reading his e-mail and meeting him for the first time.

How do you deal with a student who has just rediscovered in a negative light the enormous power of public-key cryptography? Public-key cryptography is the power of breaking symmetries between parties such that one party can compute something whereas another party cannot. This power is what makes modern cryptography a science that constantly surprises and mystifies. It is a science in which seemingly paradoxical and unsolvable problems are solved, problems like “how to flip a coin over the telephone.”

How do you deal with a student whose apparent goal is to improve computer virus attacks and capabilities? After all, virus study is dangerous and represents a threat in and of itself since experimentation can lead to accidental viral infections. Great care must be taken to isolate any and all machines that are used for experimentation.

How do you deal with a student who has a solid background in engineering but doesn't even know the basics of modular arithmetic? Number theory is at the very heart of modern cryptography. He was well versed in continuous mathematics as any student of electrical engineering should be, yet he had never even heard of the extended Euclidean algorithm when I first met him. This became clear after I realized that, despite having applied public key cryptography to virus attacks, he didn't even know how to compute an RSA private exponent given the public exponent and the two private primes.

These questions would all be answered in time. When Adam asked me if I would be his master's thesis advisor, I gladly accepted the position.8 His academic interest in pioneering virus attacks seemed genuine. It nonetheless became quickly apparent that his understanding of computer viruses exceeded the norm, and this suggested that he had conducted extensive experimentation on his own. I advised him to start learning about number theory, so he went out and bought Underwood Dudley's book on the subject [96]. Every so often he'd hit a roadblock of some sort when trying to understand a cryptosystem that he'd never seen before, and I would always explain it to him.

It was a special time for me, because I found that I was learning as much from him as he was from me. It is the type of student-teacher relationship that every faculty advisor strives for. However cliché it may be, Einstein's statement that “imagination is more important than knowledge” could not be truer with respect to scientific exploration. Adam's enthusiasm for malicious software drove him to study branches of mathematics that he probably would have never learned otherwise. As for where the research was heading, I did not know. Yet all of the ingredients for a promising student were present, so I decided to build on his natural enthusiasm for the subject, and decided that whatever he would learn and whatever direction his research would take him would be up to him.

Going forward I decided to lay down only a minimal set of principles as well as a general framework for our collaboration. It was to be a scientific endeavor rather than a rogue operation. There would be no accidental release of viruses. In fact, there would be no public disclosure of executable code at all.

We also discussed the rationale behind publishing information warfare attacks. I explained that the wisdom of the open research community as a whole, due to peer reviews, competition, and collaboration, is vast and that the scrutiny of ideas helps to make systems more secure. Closed research communities have proven to fail in the past. A classic case is the secret design behind the Clipper chip that fell from grace due to the attacks that were found against it. Only the input/output specification and the chips themselves were made available, yet attacks were nonetheless found based on the size of its parameters [28] as well as the binding of its authentication [104]. I explained to him that I agreed to investigate cryptovirology because it is interesting in its own right, and because I believed in the importance of researching defenses against cryptovirology.

From this point on working with Adam was like working with any of my previous graduate students. The motivation and insight that researchers have on cryptography varies greatly from person to person. Some people are driven by the underlying mathematics, some by system security aspects, some by theoretical considerations, and still others by practical every-day considerations. Adam approached cryptography from a completely different angle than others, and it was a new perspective for me.

During the course of our research we began referring to the virus as a cryptovirus. I coined the term cryptovirus to describe them since it accurately describes their modus operandi. A cryptovirus is a computer virus that contains and uses a public key. The original definition stipulates that the author knows the private key, but this aspect of the definition can be weakened. Polymorphic viruses have used symmetric encryption for a long time, and it is fitting to employ a new name for viruses that use public key cryptography. Cryptoviruses are unique due to their ability to perform one-way cryptographic computations that only the virus writer can undo.

* * * * *

And so it was that the first cryptovirus was researched under the auspices of Columbia University. In the weeks that followed we met regularly in the Mudd building alongside Amsterdam Avenue. During our collaborations we realized two shortcomings in the attack. First, in order for the virus to encrypt a significant amount of data it would be necessary to break the data into chunks that could be encrypted using RSA. Since RSA encryption is slow in comparison to symmetric ciphers, this meant that the attack would take a long time for the virus to carry out. Also, if the virus writer were to simply give the private key to the victim then the victim could publish the private key and foil any attempts to extort other victims. The virus writer could instead demand that he or she be given the ciphertext in order to perform the decryption, but this would require a huge file transfer. It is also quite possible that by exposing the host data to the virus writer, its value would significantly diminish.

We discovered that all of these shortcomings could be resolved in one fell swoop. In this more refined attack, the virus does not encrypt host data directly with the public key. Instead, it generates a symmetric key uniformly at random and then encrypts the host data using this key. The public key in the virus is then used to encrypt the symmetric key. This is known as hybrid encryption. If the victim wants the data back, the victim has to send the virus writer the ciphertext of the symmetric key. The virus writer then decrypts the ciphertext using his or her own private key and then sends the symmetric key to the victim. To preserve that attacker's anonymity an anonymous remailer can be used to carry out the transaction. The attack will only work if there are no backups of the host data, and if the virus was not being observed while mounting the attack. Since the symmetric key is chosen uniformly at random for each victim, publication of the symmetric key is not likely to be of any use to other victims.

With a solid and carefully planned viral payload, we set out to create the first cryptovirus. A Macintosh SE/30 computer was chosen as our test bed. The latest copy of the GNU multiprecision library was obtained, and was modified as necessary to compile on a Macintosh. Only a small fraction of the GNU multiprecision library was needed, yet it was still large enough that it comprised the majority of the cryptovirus. Part of the virus was written in ANSI C and part of it was written in Motorola assembly language. Before the first version of the virus was compiled, assembled, and linked, logic was included to prevent replication on any machine other than the SE/30. It was of the utmost importance that it not escape. It would have been incredibly embarrassing for Columbia University if it did.9 The virus was not polymorphic and was not designed to bypass any antiviral software whatsoever. As an added precaution, a snippet of the virus was taken and used as a search string. Antiviral searches were performed regularly using this custom virus definition to keep the virus in check.

The hybrid cryptosystem for the virus consisted of RSA and TEA. To generate symmetric keys randomly, AT&T's truerand was used [166]. Truerand was critical since any weakness in it might give rise to a way for victims to derive some or all of the bits of the symmetric key used in the attack. Any weaknesses in truerand, TEA, or RSA would imply a weakness in the cryptovirus attack.

Truerand can be invoked ad infinitum, producing an endless stream of random numbers. As a result the cryptovirus can be viewed as a probabilistic algorithm with access to randomness that is generated by a physical device. The original cryptovirus used the raw outputs of truerand to generate the symmetric encryption key. However, an entropy extraction algorithm should be applied to the output of truerand to remove any potential bias.

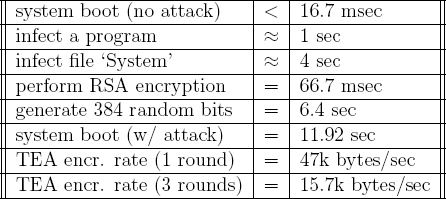

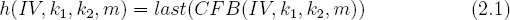

Table 2.1 gives a synopsis of the speed of the Macintosh cryptovirus. The cryptovirus contained a 512-bit RSA public modulus. This is a bit small by modern standards. RSA key lengths of 768 or 1024 bits should be used today. The virus generated 384 random bits. This was used to derive Initialization Vector (IV) information and two 128 bit symmetric keys denoted by k1 and k2. The virus computed a checksum using cipher feed-back mode (CFB) on a file entitled ‘payroll’ that the fictitious virus author demanded. The block cipher that was used in CFB was TEA in encryption-decryption-encryption mode. The EDE mode first encrypts the plaintext with k1 then decrypts the result with k2 and then encrypts that result using k1. A keyed cryptographic checksum h that uses keys k1, k2 can be implemented using CFB as follows.

Table 2.1 Running time of the virus

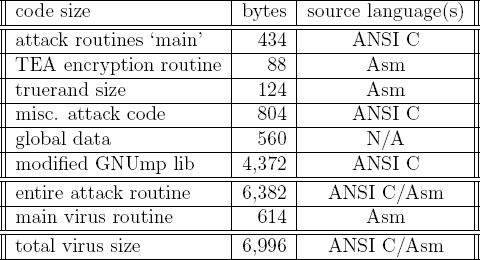

Table 2.2 Size of the virus

The checksum is computed on a message m. The function last denotes the final ciphertext block in the CFB ciphertext. A nice aspect of this checksum algorithm is that it requires very little code above and beyond the code needed to perform CFB encryption.

The virus then encrypted the confidential file entitled “e-money” using TEA in EDE mode. The original file was overwritten with the ciphertext in the process. The checksum, initialization vector information, and the two TEA keys were encrypted using the 512-bit RSA public key. The IV that is used in the encryption of the file “e-money” and both keys are needed by the victim to recover the file “e-money.”

In this hypothetical cryptovirus attack, the author demands the file “payroll” from the victim. The author does not help the victim unless the proper file “payroll” and the RSA ciphertext are obtained. Upon receiving the 512-bit RSA ciphertext from the victim, the virus author decrypts it using the RSA private key, thereby recovering the checksum, IV information, and both TEA keys. The author computes a checksum on the provided file using the IV and both keys that were recovered from the RSA ciphertext. The file “payroll” is accepted as being valid if and only if the resulting checksum matches the checksum from the decrypted RSA ciphertext. If the “payroll” file is valid then the two TEA symmetric keys are given to the victim to allow the victim to decrypt the file “e-money.” The virus computes the checksum and asymmetrically encrypts it along with the TEA keys to prevent the victim from sending an alternate version of the “payroll” file.

Speed was an important factor in benchmarking the cryptovirus, since as indicated by the table it took a noticeable amount of time to generate the 384 random bits. Table 2.2 shows the size of the resulting cryptovirus. The virus was written in Motorola assembly language and ANSI C.

With a prototype in hand as well as data on its performance, we wrote a paper about it that was submitted to the IEEE Symposium on Security & Privacy10. The paper was accepted and was presented on May 7, 1996 [332].11 To notify the scientific community of this threat, a message was posted to the sci.crypt newsgroup that explained the use of asymmetric cryptography to mount a reversible denial of service attack [330].

Since the time of the conference, a number of reports, presentations, books, and so on, have discussed cryptoviral extortion. Many of these discussions define cryptoviral extortion as a “virus that encrypts the victim's files,” without mentioning anything specific about the type of encryption algorithm that is used by the virus (e.g., symmetric, asymmetric, hybrid). In one example [86], it is stated that a “cryptovirus” has a payload that encrypts files with a secret key, making the contents inaccessible to the owner. In the cryptoviral extortion attack that we designed, the cryptovirus either (1) encrypts files with a public key, or (2) encrypts a session key with a public key and then encrypts files using the session key. Asymmetric encryption is central to a secure (from the perspective of the virus writer) cryptoviral extortion attack since the decryption key cannot be recovered from an old copy of the cryptovirus. Viruses that do not employ asymmetric cryptography do not mount the cryptoviral extortion attack as defined in [332].

Initially, the combination of software attacks and cryptographic techniques appeared to be quite powerful and this has proven to be even more so today. What we noticed over the years is that advanced and provably secure malware attacks are made possible by advances in cryptographic models and algorithmic constructions. Examples of such advances include: trapdoor functions, semantic security of encryption, cryptographically strong pseudorandomness, the random oracle model, and so forth. These are cornerstones for building secure cryptosystems and proving that they are so. Our research has shown that these tools can be used to devise attacks that are not detectable and that bestow unusual powers to the attacker. This is not unlike using missiles to take down missiles, i.e., fighting fire with fire.

Later on in this book we describe cryptotrojan attacks that leak private keys to the attacker. The approaches that are taken to prove the security of the attacks are reminiscent of approaches used in proving the security of many modern cryptosystems. We investigated cryptovirology and then moved on (without even realizing it at first) to a subject that we later called kleptography. From there we moved to other subjects that turned out to be closely related. Scientific exploration is hard to control and even harder to predict, and our joint research has led us to places that we did not expect to go. But it has been our experience that this is the way that things usually turn out in research.

The remainder of this book is not going to read like the text in Chapters 1 and 2. The purpose of these first two chapters was to expose some of the motivation and history behind cryptovirology. This is where the pedal hits the metal, so to speak. The remainder of the text is saturated with equations and algorithms. However, scattered throughout are ideas and attacks that are explained at a relatively high level. So, we encourage readers to keep reading and not be discouraged by the technical details. To us, playing the role of the bad guy is tremendous fun and we hope that readers will get a kick out the book, however sinister it may seem.

1A tick is typically 1/60th of a second.

2Some security issues have been uncovered [153] and an improved version called XTEA has been proposed [318]. XTEA is given in Figure 2.1. A weakness in XTEA was addressed by the authors [319]. XTEA has been cryptanalyzed when reduced to 14 rounds [195].

3The Vernam cipher uses a One-time pad and is subject to known-plaintext attacks when some or all of the pad is reused.

4It was one of those situations in which you know things are happening around you but you are zoned out completely. I happened to be watching livery cabs speed uptown but was scarcely aware of it.

5This means that even though the state-transition table and starting state of the virus are known, the private key will remain hidden from antiviral analysts.

6To be technically accurate, RSA is based on the difficulty of computing eth roots modulo n. Also, every RSA ciphertext leaks the Jacobi symbol of the plaintext. Public key cryptosystems with stronger security properties are discussed at the end of this chapter.

7Slight exaggeration.

8The cryptovirus attack first appeared in A. Young, “Cryptovirology and the Dark Side of Black-Box Cryptography,” Master's Thesis, Comp. Sci. S6902, Columbia University Dept. of Comp. Sci., Summer, 1995, advisor: Moti Yung.

9I had grown very fond of my alma mater after meeting Moti and it seemed that Columbia was sticking its neck out to accommodate my abnormal, albeit academic research interests.

10See the call for papers in [285]. Certain members of the program committee were vehemently opposed to its publication. The notion of a digital facehugger was apparently perceived as “vulgar” and non-scientific.

11The paper was presented in the session entitled Biologically Inspired Topics in Computer Security. The program for the conference appears in [206].