Chapter 4

The Two Faces of Anonymity

The ability to communicate anonymously and do things in an anonymous fashion is a mixed blessing. Criminals that perform criminal operations in an anonymous way minimize their risk of getting caught and voters that cast ballots anonymously do so without fear of persecution. Anonymity mechanisms, however simple in design, can be regarded as technologies unto themselves. The need for communicating anonymously and performing anonymous activities has extended into the digital realm and there currently exist advanced cryptographic algorithms for anonymously sending e-mails, voting, and purchasing items over the Internet. The potential for abuse of such technologies is immense and the first part of this chapter sheds some light on many of the possibilities. The chapter concludes with a description of a cryptotrojan attack that utilizes an anonymous communication channel. By carrying out the attack, the Trojan horse author is able to steal login/password pairs from a host machine in a way that greatly diminishes the risk of getting caught.

4.1 Anonymity in a Digital Age

Mechanisms that provide anonymity serve the common good in a variety of ways. For example, the ability to cast ballots anonymously helps protect voters against government persecution in response to their choices in electoral candidates. Other modes of communication that involve anonymity include tip lines for law enforcement agencies, newspaper classified ads, and suggestion boxes. The way in which these anonymity mechanisms serve the common good is clear. Tip lines help prevent citizens who may know the criminal from being discovered by the criminal, and also help lesser accomplices reveal crimes without fear of prosecution. Likewise, suggestion boxes help customers and patrons speak candidly about the products and services of a company or store without running the risk of being identified and mistreated.

4.1.1 From Free Elections to the Unabomber

The ability to carry out actions in an anonymous fashion is not without its drawbacks. For instance, a terrorist can take credit for a bombing by sending a letter to a news agency, calling from a pay phone, and so forth. These approaches are risky for criminals since they can leave behind a trail of fingerprints, eyewitnesses, skin tissue, and so on. The mail system is subject to even worse abuses, as evidenced by the Unabomber and Anthrax attacks in the United States.

The migration of anonymity mechanisms to the digital realm is likely to have a growing impact on both the beneficial and malicious capabilities they provide. Cryptographic on-line elections have the potential to be more accurate, more secure, and timelier. This paves the way for society to resolve issues by voting on a much larger scale, thereby more accurately capturing the true consensus of the population. On the flip side of this coin, a terrorist can claim credit for a bombing by sending a message to a news agency via an anonymous remailer. This eliminates the possibility of leaving a physical trail for forensic scientists. Terrorists can also coordinate their activities using anonymous remailers and can conceivably assign tasks to individuals without ever even meeting them in person.

4.1.2 Electronic Money and Anonymous Payments

Cash is a payment medium that is favored by many consumers due to the anonymity that it provides. Purchasing items with cash preserves the anonymity of the buyer and seller. When a consumer purchases an item with a debit or credit card, the consumer's identity and often the item or items that are purchased are revealed and recorded. This information is often sold to marketing agencies for profit and is used to solicit more sales via targeted advertising.

The downside to cash from the consumer's perspective is that it is easy to steal. A mugger that steals a wallet containing cash will profit from the criminal act. If the wallet contains a debit card then the criminal is at a loss since the personal identification number is needed to get at the money. Consumers therefore face a tradeoff when deciding to carry either cash or debit cards. Cash guarantees anonymity but runs the risk of being stolen. Debit cards are resilient against theft but expose the consumer to aggressive advertising.

Cryptography may well hail as the savior in this dilemma. Electronic money is a technology that combines the anonymity of cash with the security and convenience offered by debit cards. The concept of e-money takes getting used to, since it implies that streams of zeros and ones can replace paper money. E-money is one of the most involved applications of public key cryptography.

One of the benefits of e-money is that it can be protected from destruction. Once downloaded to a smart card, the e-notes can be copied to a home computer. If the smart card is destroyed then a backup will reside on the computer and vice versa. This is not the case with paper money. Since e-notes can be duplicated one would think that forging them would be trivial. However, this is not the case since the underlying algorithms are designed to protect against double-spending [53]. Once a note is spent it renders all other identical copies null and void. When considering the evolution of currency, the migration to e-money makes sense. The problems associated with bartering perishables for non-perishables were solved using coins. The problem of lugging around hundreds of pounds of coins was minimized using paper money. Assuming that smart cards become ubiquitous, e-money may become a cheaper payment medium overall compared to paper money. Unlike printing dollar bills, e-money takes a fraction of a second and very little energy to mint.

Electronic payment systems remain a very active area of research today since there are numerous problems to deal with in order to arrive at an acceptable solution [9, 37, 53, 130, 168, 212, 214, 303, 313]. For example, divisibility is important since many items are valued at fractions of a dollar. Efficiency is an issue since too much protocol interaction may render solutions impractical to use. A fundamental security requirement is that it must not be possible to counterfeit e-notes. An important problem to consider in deploying a secure payment system is that the security of the entire system often degenerates to that of the security level of the weakest link. This is often the case in the theory of secure systems. In many situations it is important to augment a payment scheme using mix networks [138]. Perhaps the most intriguing technological advantage to e-money over paper money is that the unforgeability aspect can be proven based on well-established intractability assumptions.

The anonymity provided by cash payments is attractive to criminals as well. Criminals often prefer to conduct transactions using cash due to the difficulty of tracing it in small quantities. As a result, serial numbers and watermarks are used when needed to help track the movement of U.S. treasury notes. The countermeasure to these traceability mechanisms is money laundering. It is not uncommon for small-time crooks to buy expensive goods at a department store in one state and then return them in another state in order to move large sums of money safely.

4.1.3 Anonymous Assassination Lotteries

Since truly anonymous e-money is not traceable it would provide an ideal medium for money laundering. It would be possible to leave the country with millions of dollars tucked away safely within an average-sized wallet. This has the potential to fill the treasuries of crime syndicates and terrorist groups to unprecedented levels. When combined with anonymous remailers, the potential for abuse of e-money is even worse. So begins the manifesto of Jim Bell, civil libertarian [186]:

A few months ago, I had a truly and quite literally “revolutionary” idea, and I jokingly called it “Assassination Politics”: I speculated on the question of whether an organization could be set up to legally announce that it would be awarding a cash prize to somebody who correctly “predicted” the death of one of a list of violators of rights, usually either government employees, officeholders, or appointees. It could ask for anonymous contributions from the public, and individuals would be able (to) send those contributions using digital cash.

The idea combines the notion of e-money with anonymous remailers to create a treacherous lottery. Cash would flow in through anonymous mix networks and each winner would receive his or her share of the pool in an anonymous reply. The combined technologies also make it possible for criminals to pay for each other's services by sending e-money to each other using anonymous remailers. This makes it impossible to coerce criminals in custody to divulge the identity of accomplices since they won't know the identities of their accomplices. Hence, the sum of both technologies is greater than the two.

4.1.4 Kidnapping and Perfect Crimes

To illustrate this even further, consider the problem that a kidnapper faces in collecting the ransom money. Even if the kidnapper sends the delivery person on a wild goose chase to the final drop-off point, the kidnapper may still get caught. This situation is risky from the kidnapper's perspective since it makes certain assumptions about the surveillance capabilities and overall manpower of law enforcement. But with e-money, this is not the case. The kidnapper can insist that the ransom be paid using e-money that is encrypted under the kidnapper's public key. Like in the cryptovirus attack, the kidnapper can insist that the encrypted e-money be sent using an anonymous remailer in an anonymous reply. This is known as the perfect crime [311].

Armed with this foresight, cryptographers have devised algorithms for implementing electronic money with safeguards that prevent these abuses [50, 140]. These safeguards typically involve key escrow, and therefore utilize a predetermined group of escrow authorities. When needed, the escrow authorities can collaborate and thereby trace the flow of e-money notes. They therefore have the ability to revoke the anonymity provided by the underlying system. Kidnappers that try to use e-money with revocable anonymity would face even worse traceability issues than with cash. In the case of assassination politics the identities of the lottery participants could be ascertained.

Sometimes it is amazing how science fiction novels foreshadow future technology. The text below is from the chapter entitled “The Logicality of Liking” from Book II of the 1975 novel The Shockwave Rider [43]. It bears a striking resemblance to mixes with revocable anonymity.1

“What sort of trick?”

“Sometimes it's known as going to the Mexican Laundry.”

“Ah. You route a credit allotment—to avoid either tax or recriminations—into and out of a section of the net where nobody can follow it without special permission.”

Given the existence of anonymous e-cash schemes that provide for revocable anonymity, one might assume that the threat of assassination politics and perfect crimes is eliminated. However, this assumption is fundamentally flawed since it makes the implicit assumption that there is an entity that is capable of controlling all payment mediums. This need not be the case.

Suppose that an offshore organization (for example, a small foreign country) creates a digital currency. Using encryption, signatures, and mix networks it would be possible to buy and sell products and services using the currency on the Internet in a confidential and untraceable fashion (similar to “BlackNet” [184]). This organization can design the payment system to be completely anonymous.2

Any country or organization that does this is likely to thrive. It would become a repository for crime syndicates worldwide and would probably amass an endowment in short order that would permit it to invest in legitimate businesses. Other countries could pass legislation that would make using the foreign e-money illegal, but cryptography would greatly inhibit law enforcement's ability to enforce such laws. Under these circumstances, the threat of anonymous assassination lotteries and perfect crimes remains alive. In Bruce Sterling's book Islands in the Net [292], Grenada is a pirate cove that closely resembles this sort of country.

4.1.5 Conducting Criminal Operations with Mixes

Mix nets and anonymous money are powerful technologies for conducting criminal activities (see Subsection 3.10.2). One can surely expect an immense amount of interest from law enforcement agencies and intelligence agencies whenever a mix network is deployed. It was only a matter of time until strong cryptography became a household technology. It is quite possible that robust mix networks will come next. Traditionally, it is open standards that gain the most widespread and rapid adoption. An open standard for a mix network, should one be drafted and highly utilized by the general public, could prove to be the single most liberating and at the same time life-threatening Internet technology to date. Various peoples live out their entire lives in fear of persecution. Mix networks have the potential to help make freedom of speech a reality worldwide.

In fact, something very similar to such a widespread open protocol already exists. The people at Nullsoft3 developed the gnutella protocol in late 1999. The gnutella protocol is currently utilized by an immense number of people round-the-clock to share files on the Internet. Many of these files are copyrighted MP3 songs. Needless to say these sorts of programs have been the bane of the recording industry for some time now. Unlike its predecessor, Napster, the gnutella protocol is completely decentralized and allows each user to be a file sharing server. This makes it exceptionally hard to apprehend those who illegally duplicate and distribute copyrighted material. It is possible to design a protocol akin to the gnutella protocol that preserves the anonymity of the recipients of copyrighted material. For example, users could connect to offshore servers using a mix network. This would allow citizens in countries with stringent copyright laws to violate copyright laws in an undetectable fashion. Furthermore, if the sharing were performed at a packet switching layer, the new protocol could serve as a general mix net packet switch and a medium for distributing MP3s. This would serve hardened criminals and casual copyright violators alike. Due to the immense number of packets relating to MP3 transfers, the network would always be highly utilized and a high level of anonymity would be assured for everyone. Perhaps the biggest technical challenge is handling the needed PKI for such a service.

An anonymous e-mail service based on a cryptographically secure mix net when combined with e-cash is a criminal's dream: criminals can operate in cells, coordinate criminal acts by sending each other anonymous e-mails, and pay for each other's services by sending each other e-cash via anonymous e-mail, all without ever knowing each other's true identity. In cryptographic terms, it is a way of secret-splitting criminal operations.4 This is a policeman's worst nightmare. Even if one criminal is apprehended there would be no way to use that prisoner to track down his or her accomplices. . . simply because the prisoner would honestly not know who the accomplices were. Interrogators love to lie to captives to get them to divulge facts that law enforcement needs. In fact they are permitted to do so under U.S. law. They need only read the criminal his or her Miranda rights and then slap 'em around a bit to prevent the criminal from taking the fifth. However, they cannot lie about leniency in regards to sentencing. Given enough pressure many criminals break. With mix nets and anonymous cash, breaking the prisoner may be a fruitless endeavor.

Using mix nets securely is a complicated business. Imagine the following Trojan horse attack on a mix net. A malicious entity, Mitch, deploys an e-mail client with a stegotrojan in it. Two criminals, Alice and Bob, both use this infected e-mail client to send and receive e-mails. Suppose that each copy of the client has a unique identifier ID. Each time a client sends out an e-mail it steganographically encodes two IDs in the header information. One ID is that of the client that constructed the e-mail. The other ID is that of the ID in the most recently received e-mail packet.

In this attack it is assumed that Alice and Bob use the infected clients on a regular basis for benign communications. Also, suppose that they have never communicated by e-mail before and that on a single occasion Alice sends Bob e-mail through an e-mail anonymizer wherein the e-mail describes a premeditated criminal act. Bob's client will eventually receive the e-mail, perhaps through his digital pseudonym. Alice's ID will go out in stego form in Bob's next e-mail. For instance, it may go to a user named Carol. If the header data that is going to Carol is in plaintext form then Mitch, who is passively eavesdropping on the network, will be in a position to learn that the anonymous e-mail that Bob received was in fact sent from Alice. The point of this attack is that hackers and intelligence agencies can use stegotrojans to foil the anonymity that is provided by mix nets. There are a myriad of other ways to do this. Criminals and honest users alike would do well by verifying the design used in all of their hardware and software, especially network related software. In the absence of doing so, the safest assumption to make is that all of your communications will be traceable. This attack does not necessarily imply that Mitch will be able to read the message that was sent from Alice to Bob through the mix net. It could be encrypted using Bob's public key. However, due to the steganographic tag in the e-mail header, the ciphertext could be traceable. This may constitute enough probable cause to arrest and interrogate Alice or Bob.

Violating the anonymity afforded by mix nets is a serious issue. It has the potential for ruining the privacy in electronic voting protocols. There exist numerous provably secure cryptographic protocols for voting in the scientific literature. Many are based on the existence of secure anonymizing capabilities. In a matter of years companies are likely to produce e-voting software and tout it as being 100 percent secure, accurate, and timely. Given the presidential election tally screw-up in Florida recently, it may end up being adopted. If such technologies become the norm, the threat of stegotrojans and government corruption could then more easily give rise to an Orwellian society.

The use of Linux or a similar free operating system may help in preventing stegotrojan attacks. Operating systems that are based on Unix exist in the public domain. Their source code can be verified. They can then be compiled and used. However, care must be taken that the underlying computer and compiler do not contain Trojans. A clever attack in this regard is presented in Section 9.3.

4.2 Deniable Password Snatching

Given the ideas behind assassination politics and the perfect crime it seemed only natural that other dark applications of anonymity could be found. These two threats do not involve malware per se and can be categorized as protocols that are conducted by malicious individuals. The cryptovirus attack merges malware with mix networks and could easily make use of e-money if such currency were known to be untraceable.

The concept of a cryptovirus is a simple one. Place a public key in a virus and let it perform one-way operations on the host system that only the author can undo. It is really the payload of a cryptovirus that gives it an edge, since the public key in no way assists in viral replication. The discovery of the cryptovirus attack led us to ask ourselves the following question:

In what other novel ways can malicious software, when gifted with the public key of the author, mount attacks on its host with improved efficacy?

The question itself suggests that all existing cryptographic tools need to be analyzed from the perspective of degrading system security rather than improving it. The notion of anonymity had already proven fruitful in the perfect crime, assassination politics, and the cryptovirus attack. It was only natural to question whether or not its uses had been exhausted. This led to our work on deniable password snatching [334].

4.2.1 Password Snatching and Security by Obscurity

Consider a typical Trojan horse program that steals the login/password pairs of users. The Trojan horse program hooks into the system's authentication mechanism and captures such pairs as they are entered by the users. The login/password pairs are often stored in a file with an obscure name in a remote location on the file system. In some operating systems it is even possible to designate the file as being invisible, which makes it harder to detect. The attacker then accesses the machine at a later time and downloads the pilfered login/password pairs. From the attacker's perspective this attack is risky for two reasons:

- Someone else may find the hidden file and infiltrate the accounts, thereby endangering the author of the Trojan horse. The assumption that others will not read data in the file by virtue of the fact that the file is hidden is dangerous. It is an instance of security by obscurity, a discouraged cryptographic practice.

- The Trojan horse may be discovered by system administrators and alarms may be put in place that sound whenever the hidden file is read. So, the Trojan author is sticking his or her neck out by issuing commands to download the hidden file.

Security by obscurity is discouraged among cryptographers but it is a principle that applies to computer security in general. Security should not depend on the secrecy of the design nor the ignorance of the attacker [13].

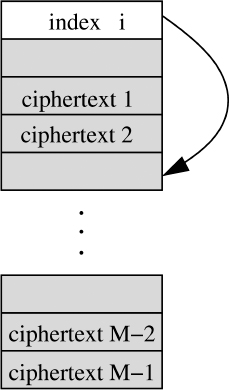

4.2.2 Solving the Problem Using Cryptovirology

The virus writer can readily overcome both of these problems. To carry out the attack, a cryptotrojan that contains the public key of the virus writer can be used. To solve the first issue, the Trojan horse encrypts each login/password pair using the public key contained within the virus. The data can be encrypted using the RSA-based OAEP cryptosystem, for instance. The resulting ciphertext is stored in a hidden file as before. The hidden file can be designed to contain M ciphertext values at all times and hence remain fixed in size. To implement this, an index i is stored at the beginning of the file (see Figure 4.1). The value i stores the index of the next ciphertext to be overwritten. It will range from 0 to M − 1 inclusive and when M − 1 is reached the value for i will then wrap back around to zero. This way, the Trojan will overwrite the oldest entries in the file when it is full. By doing so the entries will always be kept up-to-date. If the Trojan is in place for months on end and users change their passwords, the Trojan will overwrite the old passwords in favor of the new ones. It is important to keep the file from constantly increasing in size to keep it from drawing unwanted attention.

In the deniable password-snatching attack the file is initially filled with M ciphertexts corresponding to the encryptions of M randomly chosen messages. The starting value for i is a number chosen uniformly at random between 0 and M − 1 inclusive. These starting conditions help obfuscate the activity of the Trojan immediately upon deployment.

Figure 4.1 Hidden login/password file

The notion of anonymity leads to the solution of issue (2). The fact that the login/password pairs are securely encrypted paves the way for using an anonymous distribution channel. The idea is to covertly give the hidden file to the general public. This can be done without compromising the stolen passwords since only the Trojan horse author can decrypt the file.

For concreteness, consider a scenario in which the Trojan author plans on returning to the machine to download the hidden file to a floppy disk. In this attack the Trojan horse is designed to unconditionally copy the hidden file to every writable floppy disk that is inserted into the machine that has a sufficient amount of free space. To make the password data as unnoticeable as possible, it is written to the last few unused sectors of the floppy disk. These sectors must remain unused in the eyes of the file system. If the sectors were marked as allocated then users might discover the file due to loss of disk space. The Trojan horse author must be sure not to write to the floppy disk until the hidden file is safely recovered from the floppy using a low-level disk editor. As a result of this approach, lots of users may inadvertently receive a copy of the hidden password file. Since it is public key encrypted they will not be able to decipher it.

This attack illustrates that malware often needs to collect and store data that is obtained from the host environment. To make malware difficult to detect it should be fixed in size and this suggests that circularly linked lists are ideal data structures for storing data that needs to be kept up-to-date in malware.

The biggest problem that remains in this attack from the perspective of the Trojan horse author is installing the Trojan horse program in the first place. One way to do this is to write a virus that installs the Trojan horse program. For example, the author can store the infected program on a floppy. To install the Trojan horse, the floppy is inserted into the host machine and the infected program is run. The virus will migrate from the executable on the floppy to the host machine on its own. If the author is caught at this time then he or she can claim to be an innocent victim of the virus.5

4.2.3 Zero-Knowledge Proofs to the Rescue

There are a couple of effective defenses against this deniable password-snatching attack. If a Public Key Infrastructure is available and users are outfitted with smart cards, then they can conduct zero-knowledge interactive proofs to authenticate without using login/password pairs. It can be shown via a simulation argument that an eavesdropper that observes ZKIP authentication sessions learns absolutely nothing that will allow the eavesdropper to impersonate other users. Another solution is to use timed cryptographic tokens such as RSA's SecurID product. This battery-powered token computes hash values and displays them on the token in regular intervals. Each user must also choose a personal identification number (PIN) to use along with the token. To authenticate to a host system a user transmits both the PIN and the current hash value. Like ZKIPs, the solution is secure against eavesdroppers that learn the PIN and hash values, provided that the SecurID token remains in the custody of the user. The SecurID token is a tamper-resistant device that stores secret information that is used to compute the hash values. The existence of these robust authentication technologies implies that the utility of the deniable password-snatching attack is likely to wane as time goes on.

However, the attack is general in nature and can be used for stealing data other than login/password pairs. The method works equally well for stealing any kind of information on host machines. Assuming that a benign communication channel exists, a Trojan on a compromised machine can broadcast public key encrypted data over the channel. Benign channels include steganographic channels, subliminal channels, dummy fields in packet headers, and so on. In this case only the Trojan author will be able to decipher the broadcast.

4.2.4 Improving the Attack Using ElGamal

By using a specific type of public key cryptosystem the attack can be improved slightly. Ideally, the Trojan horse author would like the administrator of the host machine to be as oblivious to the activities of the Trojan horse as possible. This includes not letting the administrator know how many passwords, if any, were stolen before the discovery of the Trojan horse.

This can be accomplished by using the ElGamal cryptosystem [110] modified appropriately [304] to be semantically secure under plaintext attacks6 (see Appendix C.2.2). Recall that x is the private key and (y, g, p) is the corresponding public key in ElGamal. The ciphertext of m is the pair (a, b). One of the most useful properties of ElGamal is that its ciphertexts are malleable under multiplication. By multiplying b by some other plaintext m1 the encrypted plaintext becomes mm1 mod p. Also, it is possible to rerandomize ElGamal ciphertexts as follows. Choose a value k1 < q randomly and compute (a′, b′) = (agk′ mod p, byk′ mod p). This changes the appearance of (a, b) completely and (a′, b′) decrypts to the same value as (a, b).

In regular intervals the Trojan horse can be designed to perform this rerandomization to all M ciphertexts regardless of whether or not any new passwords are stolen. Also, the decision to steal each login/password pair can be probabilistic. As a result, with some very small probability the Trojan will never encrypt any login/password pairs. This approach will hamper the sysadmin's attempt to determine if any passwords have been stolen before the discovery of the Trojan horse. If disk backups are continually taken then system administrators will have a chance of catching a glimpse of the previous activities of the Trojan horse. For example, a dump of virtual memory could expose the virus while it was encrypting a given user's password. However, if all of the backups miss these small windows of opportunity, then it could not be proven that any passwords had been stolen prior to the discovery of the Trojan. All M entries will change regardless of whether or not the Trojan snatches a single password.

As in turns out the deniable password-snatching attack can be improved even more. By observing the password-snatching Trojan in action it is possible to witness it encrypt passwords and transmit them. It is possible to redesign the Trojan so that even when the Trojan is monitored at runtime it is not possible to tell if it is actually encrypting anything. The improved attack utilizes a new notion that we call questionable encryptions. See Section 6.6 for details.

1Special thanks to C. C. Michael for pointing this out.

2Perhaps under suitable computational intractability assumptions.

3The creators of Winamp.

4Certain crimes can even be split down to the level where each slice is hardly a criminal act in and of itself. The ability to amass chemicals in small quantities comes to mind.

5Such an argument is not likely to work when you are a known cryptovirologist, however.

6In this attack the malware designer cannot be used as a decryption oracle.