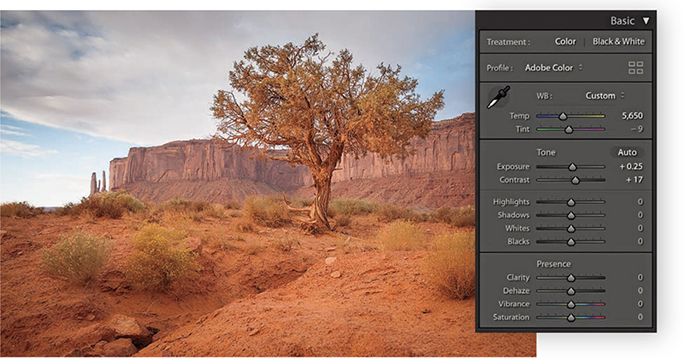

1. This overexposed photograph was initially processed using the default Basic panel settings in the Develop module. The histogram showed severe clipping in the highlights, and you can see here how there is not much detail in the lightest areas. A histogram like this can appear disconcerting until you realize that there is more information contained in the image than appears at first sight.

2. The main treatment for an overexposed photo is to apply a combination of negative Exposure and Highlights adjustments, although I mainly used the Exposure slider here to achieve the desired darkening.

Correcting Underexposed Images

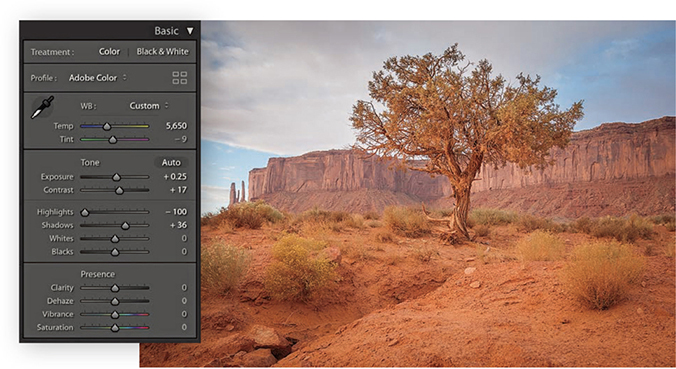

Underexposed images present a bigger problem because there will be fewer levels available for you to manipulate, particularly in the shadows. However, the Basic panel controls in Lightroom can be used to brighten an image and lift out the shadow detail. The way you need to approach this is to start by dragging the Exposure slider to the right until the image appears to have about the right brightness. As you do so, do not worry too much about the shadows, because the next step will be to adjust the Shadows slider by dragging this to the right to bring out more detail in the shadow regions of the image. Beyond that, it is all about fine-tuning the remaining sliders. In the example shown here, I needed to reduce the Highlights to preserve tonal detail in the highlight areas, and I also needed to adjust the Blacks slider to compensate for the Shadows adjustment and maintain the right amount of contrast in the darker areas. You will also want to watch out for deteriorating shadow detail, as brightening up a dark photo can reveal problems in the shadows such as tone banding and noise. See Chapter 6 for advice on how best to handle such situations.

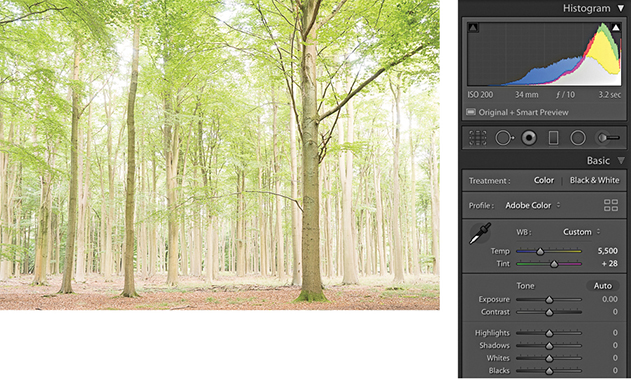

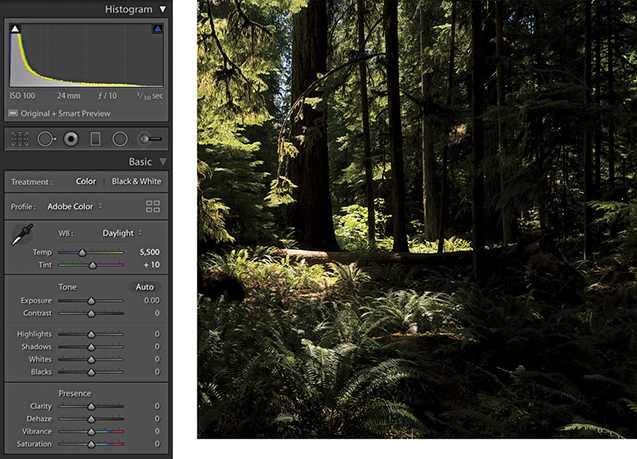

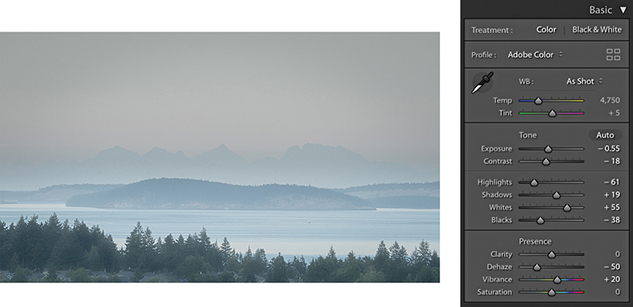

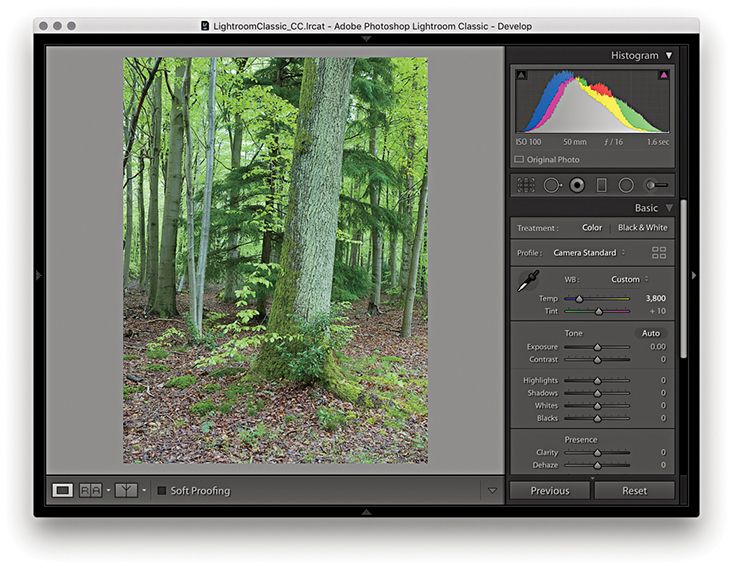

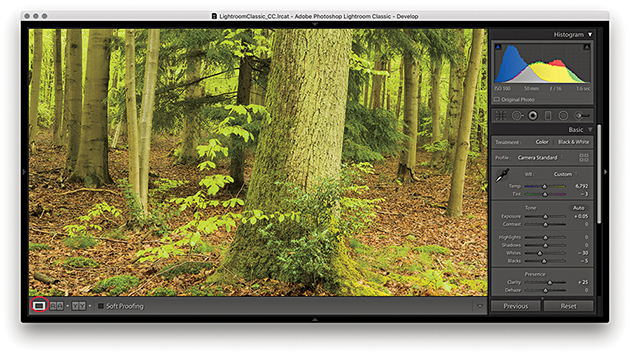

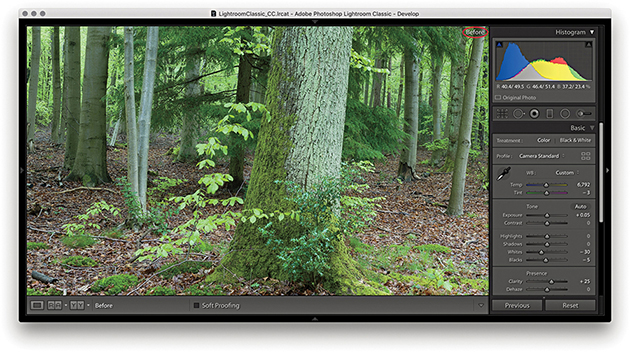

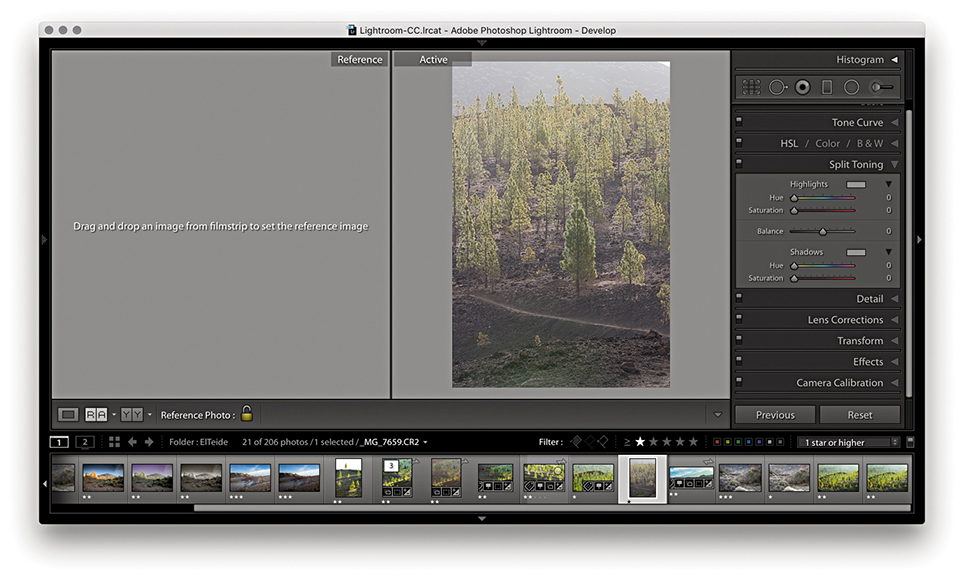

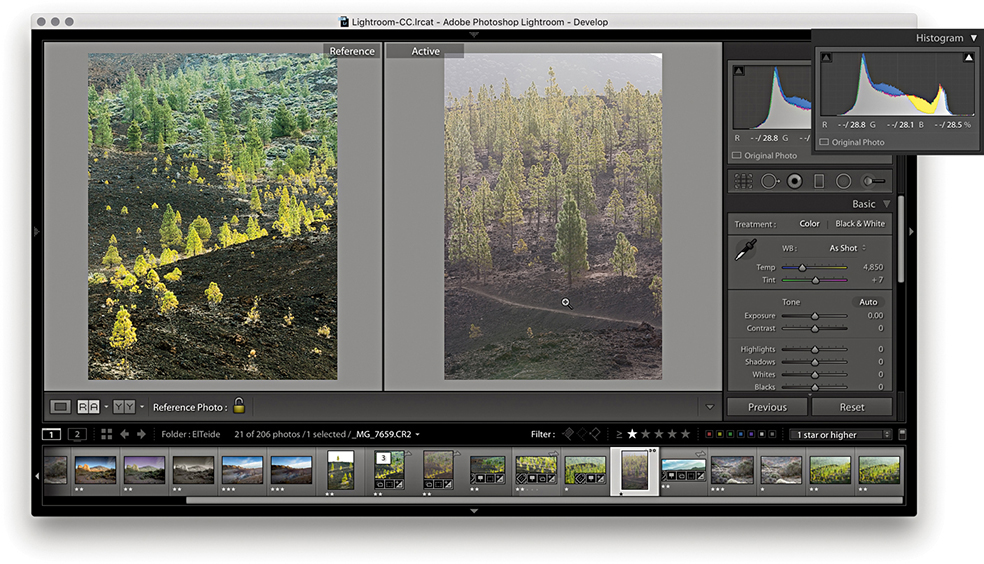

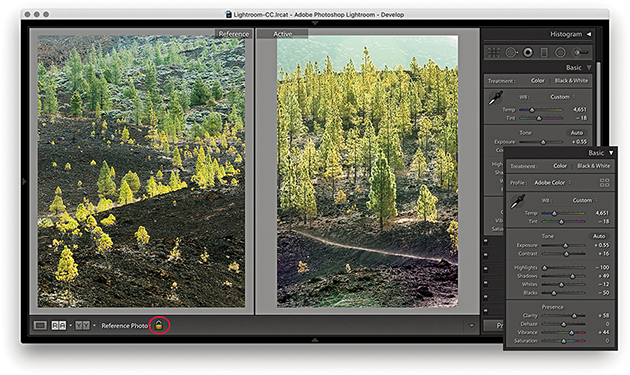

1. To begin with, this image was underexposed and the Basic panel settings remained at the default 0 settings.

2. I dragged the Exposure slider to the right, which lightened the image considerably. But because I was lightening for the midpoint, this adjustment also over-brightened the highlight areas. To compensate for this, I applied a negative Highlights adjustment. I added a positive Shadows adjustment to lighten the dark areas of the photo and applied a small negative Blacks adjustment to ensure the shadows were clipped correctly. Finally, I added positive Clarity and Dehaze adjustments to boost the midtone contrast. The end result is a photo that is perfectly usable (considering how dark it was before). However, lightening such a dark original will also amplify the noise, which may be especially noticeable in the deep shadow areas.

Match Total Exposures

You can use the Match Total Exposures command to match the exposure brightness across a series of images that have been selected via the Filmstrip. Match Total Exposures calculates a match value by analyzing and combining the shutter speed, the lens aperture, the ISO, and any camera-set exposure compensation. It then factors in all these camera-set values, combines them with the desired exposure value (as set in the most selected image), and calculates new Lightroom exposure values for all the other selected images. I find this technique can often be used to help average out the exposure brightness in a series of photos where the light levels have gone up and down during a shoot, or where there is a variance in the strobe flash output. The former chief Lightroom architect Mark Hamburg also liked to describe this as a “de-bracketing” command. Basically, if you highlight an individual image in a series and select Match Total Exposures, the other images in that selection will automatically be balanced to match the exposure of the target image.

Tip

The Match Total Exposures command is also available as an option in the Library module Photo  Develop Settings menu.

Develop Settings menu.

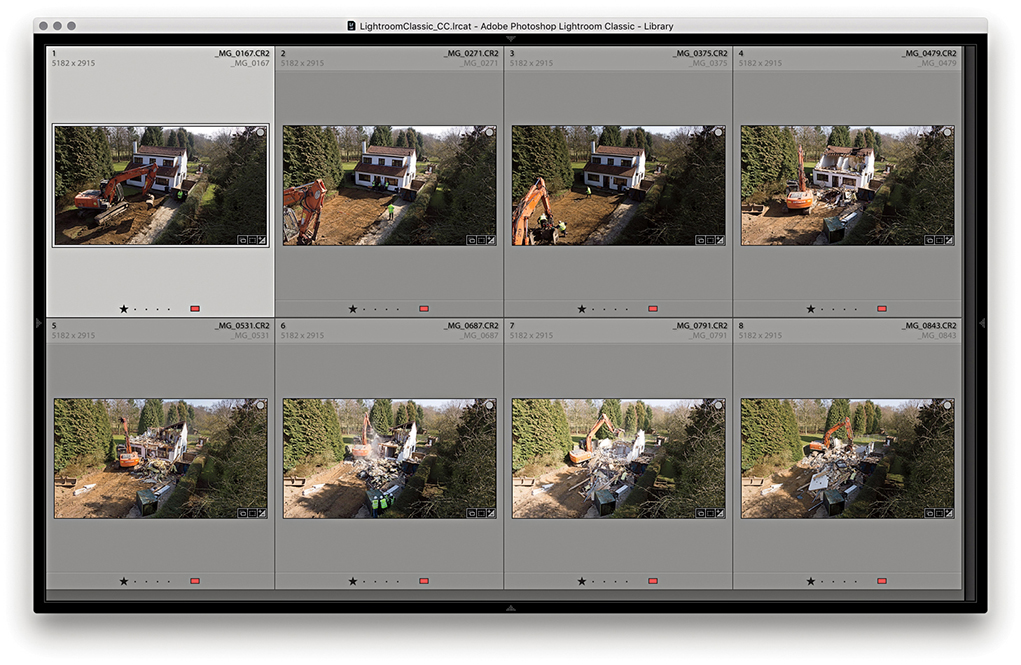

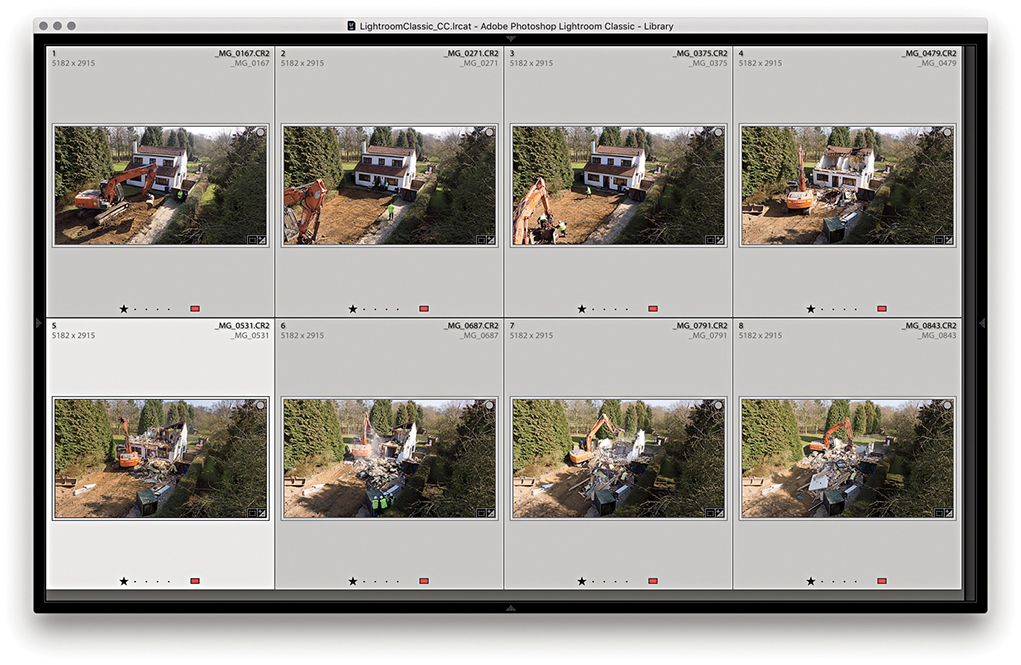

1. To begin, I made a selection of photographs in the Library module Grid view. As you can see, the light levels varied quite a bit when I shot this photo sequence.

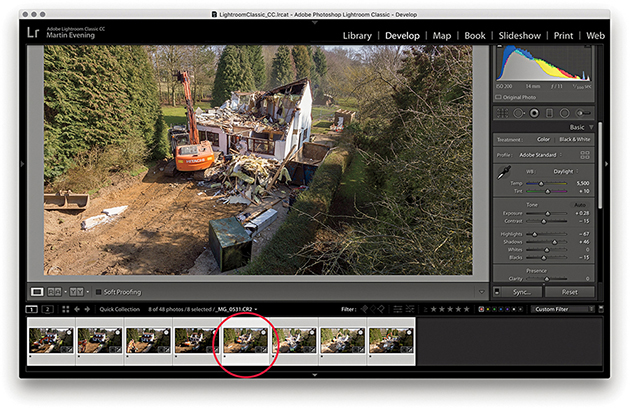

2. I selected the photo with the most correct-looking exposure and made this the most selected, target image. I went to the Develop module and chose Match Total Exposures from the Settings menu ( [Mac] or

[Mac] or  [PC]).

[PC]).

3. In the Library Grid view, you can see the exposure appearance of the selected photos is now more evenly balanced compared to the Library Grid view in Step 1.

Highlight Clipping and Exposure Settings

The main objective when optimizing an image is to ensure that the fullest tonal range can be reproduced in print. With this in mind, it is vitally important you set the highlights correctly. If the highlights are clipped, you risk losing important highlight detail in the finished print. And if you don’t clip them enough, you will end up with flat-looking prints that lack sparkle.

When setting the Exposure and Whites sliders, you need to be aware of the difference between reflective and nonreflective highlights and how the highlight clipping you apply affects the way the image will eventually print. The two examples shown in Figure 4.48 help explain these differences. A reflective highlight (also referred to as a specular highlight) is a shiny highlight, such as the light reflecting off a glass or metal surface, and contains no highlight detail. It is therefore advisable to clip these highlights so that they are the brightest part of the picture and are printed using the maximum paper-white value. In Figure 4.48, the metal sculpture has plenty of reflective highlights, and you would want to make sure these were clipped when making an Exposure adjustment. Nonreflective highlights (also known as nonspecular highlights) need to be treated more carefully. These mostly contain important detail that needs to be preserved. Each print process varies, but in general, whether you are printing to a CMYK press or printing via a desktop inkjet printer, if the nonreflective highlights are set too close to the point where the highlights start to clip, there is a risk that any important detail in these highlights may print as paper white.

It is not too difficult learning how to set the Exposure and Whites sliders correctly. Basically, you just need to be aware of the difference between a reflective and nonreflective highlight, and the clipping issues involved. Most photos will contain at least a few reflective highlights. In practice, I use the highlight clipping preview when adjusting the Whites slider (discussed on page 201) to analyze where the highlight clipping is taking place and toggle between the clipping preview and the Normal image preview to determine if these highlights contain important detail. Alternatively, you can use the clipping warning in the Histogram panel as a guide as to when the highlights are about to become clipped. I usually adjust the Whites slider so that the reflective highlights are slightly clipped, but at the same time, I carefully check the nonreflective highlights to make sure these are protected. To do this, I either reduce the Highlights slider to protect the highlights or (more likely) adjust the Whites slider so that the reflective highlights are a little less bright than the brightest white.

Clipping the blacks

Setting the blacks is not nearly as critical as adjusting the highlight clipping. It all boils down to a simple question of how much you want to clip the shadows. Do you want to clip them a little, or do you want to clip them a lot?

There is no need to set the shadow point to a specific black value that is lighter than a 0 black unless you are working toward a specific, known print output. Even then, this should not really be necessary, because both Lightroom and Photoshop are able to automatically compensate the shadow point every time you send a file to a desktop printer, or each time you convert an image to CMYK. Just remember this: Lightroom’s internal color management system always ensures that the blackest blacks you set in the Basic panel faithfully print as black and preserve all the shadow detail. When you convert an image to CMYK in Photoshop, the color management system in Photoshop similarly makes sure the blackest blacks are translated to a black value that will print successfully on the press.

On page 201, I showed an example of how to use a clipping preview to analyze the shadows and determine where to set the clipping point with the Blacks slider. In this example, the objective was to clip the blacks just a little so as to maximize the tonal range between the shadows and the highlights. It is rarely a good idea to clip the highlights unnecessarily, but clipping the shadows can be done to enhance the contrast. Figure 4.49 shows an example of deliberately clipping the shadows in an image to go to black. A great many photographers have built their style of photography around the use of deep blacks in their photographs. For example, photographer Greg Gorman regularly processes his black-and-white portraits so that the photographs he shoots against black are printed with a solid black backdrop. Some photographs, such as Figure 4.50, may contain important information in the shadows. In this example, a lot of information in the shadow region needs to be preserved. The last thing I would want to do here would be to clip the blacks too aggressively, as this might result in important shadow detail becoming lost.

Creating HDR Photos Using Photo Merge

The Photo Merge feature can be used to process raw or non-raw images to generate either high dynamic range (HDR) or panorama images, saved as master DNG files. Let’s start though by looking at how Photo Merge can be used to create HDR DNGs.

Tip

You can search for Photo Merge HDR images by creating a smart collection that filters photos that are both DNG files and have the -HDR suffix.

The principles here are the same as when using the Merge to HDR Pro method in Photoshop. You need to select two or more photos of a subject that has been photographed using different exposure settings and shot using the same format—either raw or JPEG. You can even use the Photo Merge feature when only Smart Previews are available. The photographs need to be shot from the same position, ideally with the camera firmly mounted on a tripod. When making the exposures, the lens aperture must remain fixed, and you adjust the exposure only by varying the time duration. You can shoot a bracketed sequence of two, three, five, or seven images, where the exposures can be bracketed in two-stop increments (or even wider). According to the engineers, a DNG Photo Merge can be really effective when processing just two image exposures; for example, you might have a landscape subject and one capture is exposed for the ground and the other for the sky.

Creating an HDR Photo Merge from raw file originals produces a merged DNG master image that extends the dynamic range and preserves the image data in a raw state. It can be argued that many raw images do already have a high dynamic range. Consequently, there should not necessarily be a huge difference when editing Photo Merge HDR photos compared to regular raw photos. The results you get using HDR Photo Merge in Lightroom will be slightly different from using Merge to HDR Pro in Photoshop. This is to be expected because the processing technique is not exactly the same. Therefore, you will find the results you get in Lightroom may be better, or they can sometimes be worse, compared to Photoshop.

To create an HDR Photo Merge, select two or more photos to merge; both must be in Version 4 or later. If not, make sure you update them to the latest process version. Having done that, choose Photo  Photo Merge

Photo Merge  HDR, or use the

HDR, or use the  shortcut. To open in “headless” mode, use

shortcut. To open in “headless” mode, use  . In “headless” mode, Lightroom processes the photos automatically without showing the HDR Merge Preview dialog (and processes the images based on the last-used settings). Otherwise, you will see the dialog shown in Step 2 (see page 216), where you have the option to edit the HDR Photo Merge settings. If the photos were shot handheld, you will need to select the Auto Align option.

. In “headless” mode, Lightroom processes the photos automatically without showing the HDR Merge Preview dialog (and processes the images based on the last-used settings). Otherwise, you will see the dialog shown in Step 2 (see page 216), where you have the option to edit the HDR Photo Merge settings. If the photos were shot handheld, you will need to select the Auto Align option.

If Auto Settings is unselected, default Develop settings will be applied and these will be based on the most selected photo. When Auto Settings is enabled, Lightroom applies a suitable Auto Tone adjustment during the Photo Merge HDR DNG creation process. If settings have already been applied to the source images, some of these will be copied to the resulting HDR DNG, but not all. In the case of an HDR Photo Merge, existing Basic panel tone adjustments, Tone Curve adjustments, localized corrections, plus Upright and Crop adjustments will not be copied, but other settings will be.

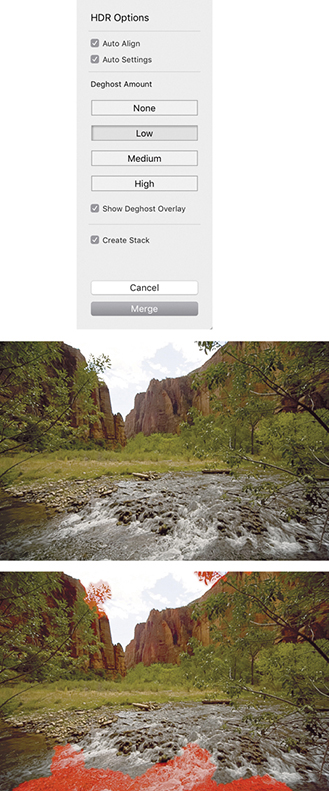

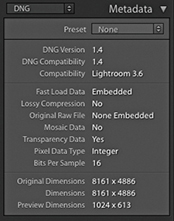

The resulting DNGs from an HDR Photo Merge will be saved as 16-bit floating point files (Figure 4.51), where the merged data will be raw linear RGB data. If the source images used in a Photo Merge come from multiple folders, the resulting DNG file will be created in the same folder as the first image in the selected set. The HDR DNG files can be quite large in size. You could argue these are not truly raw files, but DNGs produced this way are still mostly unprocessed and allow you to make creative color and tone decisions via the Lightroom Develop module. You also retain the flexibility to reprocess the resulting HDR DNG files at any time and apply later process versions. Essentially, you can merge raw files to create an unprocessed master where you can then fine-tune the settings at the post-Photo Merge stage, adjusting things like the white balance and endpoint clipping.

Whenever you carry out a Photo Merge HDR or Panorama, there is now an option to Auto Stack the Merge Operation result alongside the input images (see Figure 4.52). When checked, all photos are automatically stacked together and the merged image will be the cover image for the stack.

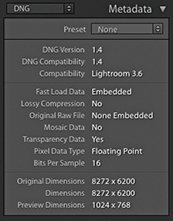

Deghost Amount options

It is crucial to avoid having anything in the scene move between exposures. Some cloud movement can be okay, providing the clouds haven’t moved too much. Where subject movement is likely to be a problem, such as with moving water and trees, the Lightroom Photo Merge deghosting algorithm can help reduce any ghosting artifacts.

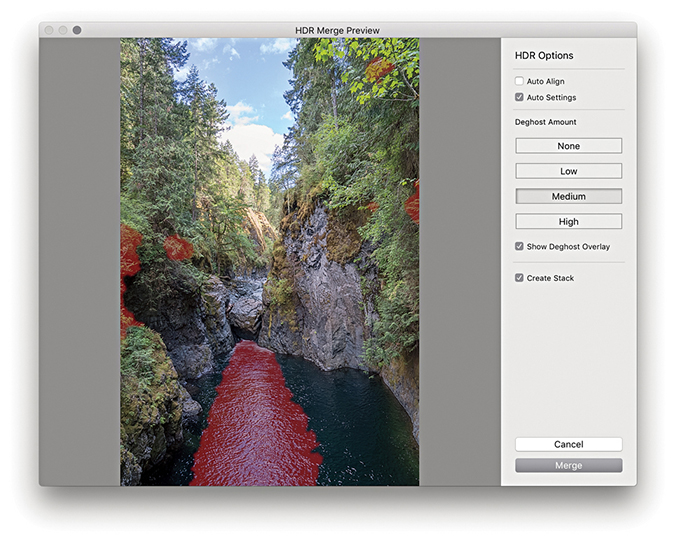

When creating a Photo Merge HDR, you can click on one of the four buttons ranging from None to High (Figure 4.52) to apply the desired level of deghosting. In this particular example, I merged three bracketed exposures where there was movement in some of the trees and water between each exposure. I selected the Low Deghost Amount option and checked the Show Deghost Overlay option. This highlighted in red the areas where the deghosting would be applied. (On the Mac, use  to turn the overlay on or off and use

to turn the overlay on or off and use  to cycle through the available overlay colors.)

to cycle through the available overlay colors.)

It is recommended that you enable deghosting only when it is necessary to do so. The Lightroom Photo Merge method may utilize more than one image to deghost the resulting HDR. When it works, it is great, but when it doesn’t, this can sometimes lead to unwanted artifacts in the final image, so it is best to leave it at the default None setting if you don’t need it.

1. I went to the Library module and selected the two photos shown here. There was a four-stop exposure difference between each of these captures. In the Library module, I chose Photo  Photo Merge

Photo Merge  HDR.

HDR.

2. In the HDR Merge Preview dialog, I checked Auto Settings to apply an auto adjustment. Because this scene featured fast-flowing water, I selected a Medium Deghost setting with Show Deghost Overlay checked.

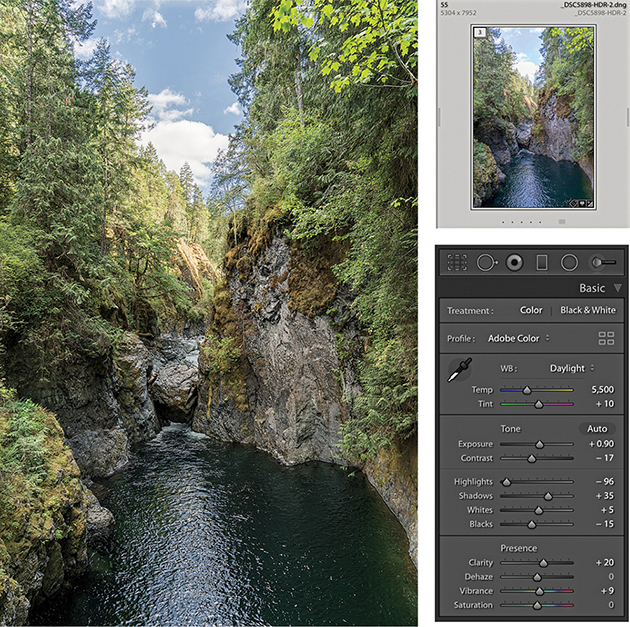

3. I clicked the Merge button in the Photo Merge – HDR dialog to create a DNG HDR master. This was automatically added to the catalog and named based on the most selected image in the photo selection with an –HDR suffix added. Because I had previously selected Create Stack, the HDR DNG appeared grouped with the source images in a stack. The Auto Settings provided a useful start upon which to fine-tune the Tone and Presence settings in the Basic panel.

Creating Photo Merge Panoramas

You can also use the Photo Merge feature to create DNG panoramas from raw as well as non-raw files. The resulting files are 16-bit integer DNGs. Like the HDR DNGs, these are demosaiced DNGs saved as raw linear RGB data (Figure 4.53). What distinguishes these from regular DNG files is the fact they don’t have mosaic data, but do have transparency data. Although the images are partially processed, you still retain the ability to apply Develop module edits and update to later process versions as they become available.

One of the things I have noticed with a conventional Photoshop Photomerge workflow is how the Photomerge processing can sometimes cause the highlight values to clip. You may carefully set the highlight end points at the pre-Photomerge stage, only to find they become clipped in the resulting Photomerge composite. Therefore, being able to preserve the raw data when using the panorama Photo Merge in Lightroom helps you avoid this problem completely, maintaining full control over the tones, and avoid undesired clipping.

To create a regular Photo Merge panorama, you first need to select a series of photographs that together make up a panoramic view. Then, go to the Photo menu and choose Photo Merge  Panorama (

Panorama ( ). You can use

). You can use  to open Photo Merge in “headless” mode, without showing the Panorama Merge Preview dialog (and process the images based on the last used settings). Otherwise, you will see the dialog shown in Step 2 (see page 220), where you have the option to adjust the projection method and other settings.

to open Photo Merge in “headless” mode, without showing the Panorama Merge Preview dialog (and process the images based on the last used settings). Otherwise, you will see the dialog shown in Step 2 (see page 220), where you have the option to adjust the projection method and other settings.

When photographing a panorama sequence, it helps if you manage to capture a significant overlap between each capture. There should be at least 25% overlap, or more if shooting with a wide-angle lens. It helps if you have the camera mounted on a tripod when you capture these; better yet, use a special tripod head that allows you to align the nodal point of the lens to the rotation axis. But you can certainly get good-enough results shooting handheld. Ideally, the exposure setting should be consistent, but even if the photos are captured with a variance of exposure, the Photo Merge process can even these out to a certain extent. Lens warp, vignette, and chromatic aberration are automatically applied to the images behind the scenes before stitching, so such settings in the source images are ignored and not copied to the resulting panorama DNG. Other adjustments, such as Basic panel, Tone Curve panel, Lens Corrections panel defringe adjustments, and color adjustments, are copied, but Upright and Crop adjustments are not included.

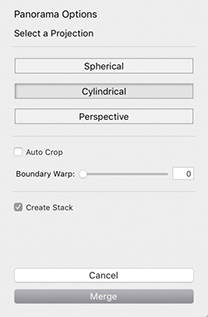

Panorama projection options

The Panorama Merge Preview projection options are shown in Figure 4.54. In most cases, Photo Merge auto-selects the best method and will give the best results. It may also better preserve image content in individual photos such as birds flying in the sky. But the auto-selected projection method won’t always be the best one to use, so it is often a good idea to check the alternatives. Perspective mode is the best option to choose for architectural subjects and can produce good results when processing images that were shot using a moderate wide-angle lens or longer. Even though the preview may show some perspective distortion, this can easily be corrected using the Transform panel controls. Cylindrical mode ensures that photos are correctly aligned to the horizontal axis. This mode is particularly appropriate when merging single rows of photographs that make up a super-wide panorama. Spherical mode transforms the photos both horizontally and vertically. This mode is more adaptable when it comes to aligning tricky panoramic sequences. So, for example, when you shoot a sequence of images that consists of two or more rows, the Spherical projection mode may produce better results than the Cylindrical method.

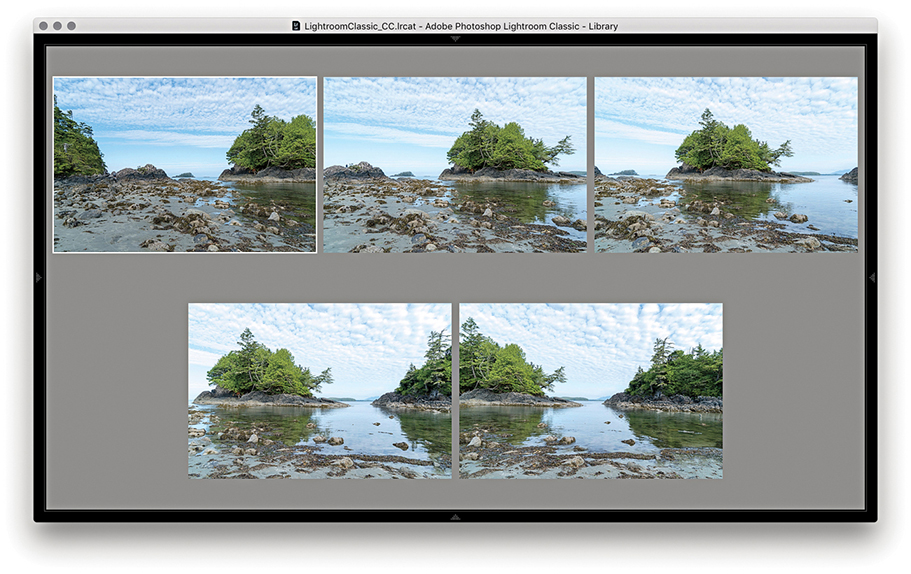

1. To demonstrate the Panorama Merge Preview function, I selected the five photographs that are shown here in the Library module Survey view mode. I then went to the Photo menu and chose Photo Merge  Panorama.

Panorama.

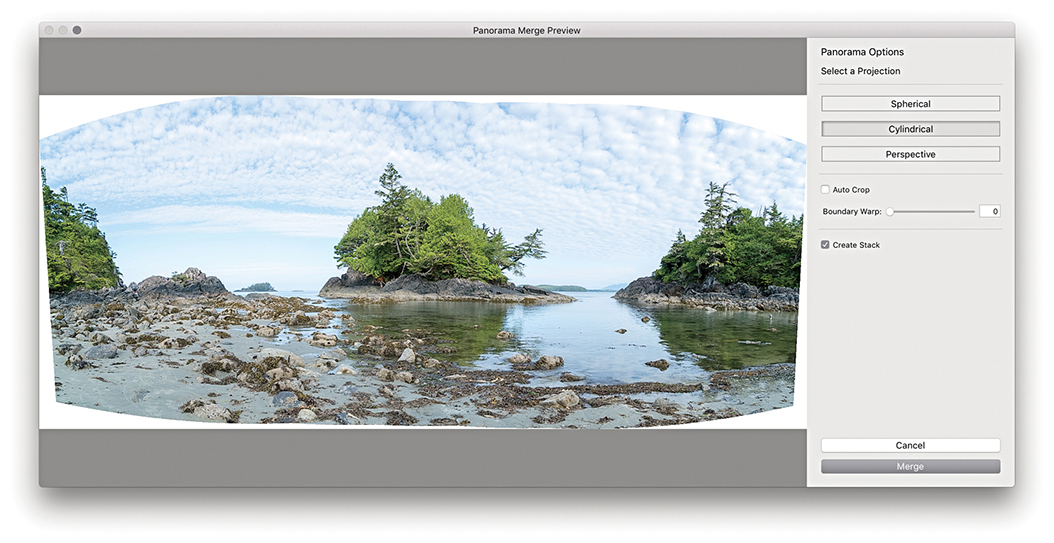

2. This opened the Panorama Merge Preview dialog, where I could select the desired projection and preview the results before committing to creating a full Photo Merge. In this instance, Photo Merge auto-selected the Cylindrical option.

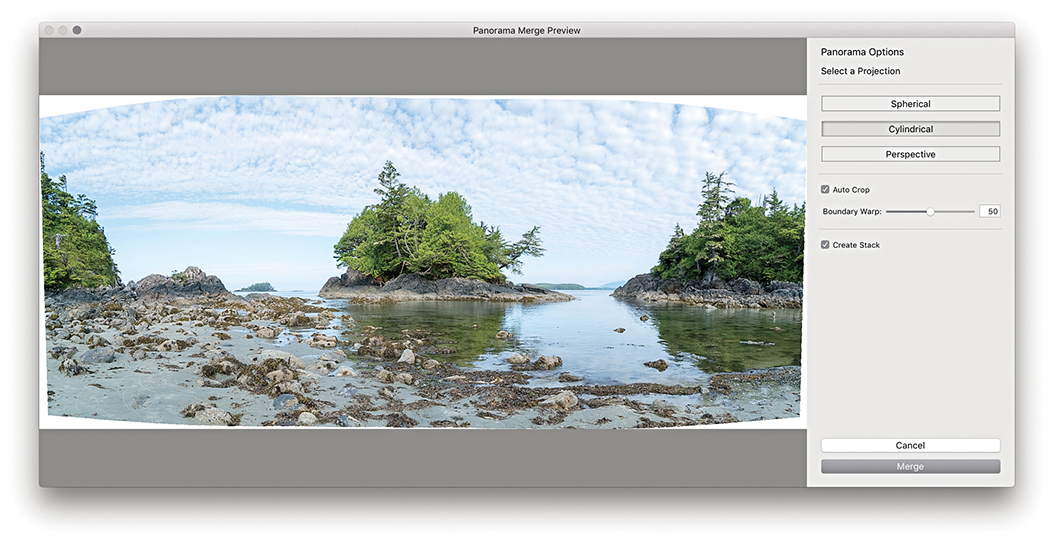

3. I set the Boundary Warp slider to 50% to warp the image to make the boundary fit the surrounding rectangular frame (Boundary Warp is discussed in the following section). I then clicked the Merge button.

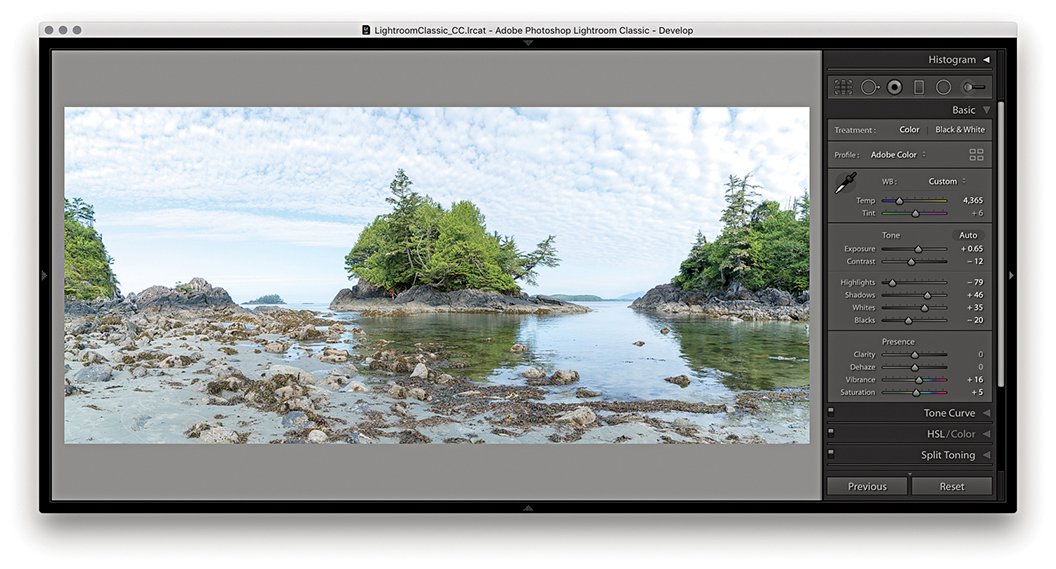

4. This created a full Photo Merge Panorama DNG, renamed based on the most selected image in the photo selection, with a –Pano suffix added. The Develop settings applied here were based on whatever was the most selected photo in Step 1.

5. Finally, I adjusted the color and tone settings in the Basic panel to produce the finished version shown here.

Boundary Warp slider

You can adjust the Boundary Warp slider to preserve image content near the boundary that might otherwise be lost due to cropping. Higher amounts cause the boundary of the panorama to fit more closely to the surrounding rectangular frame. This can be beneficial when processing landscape panoramas, although it may cause some noticeable distortion if applied to architectural subjects. However, Lightroom-generated panoramas contain the necessary metadata to allow them to later be perspective-corrected using the Adaptive Wide Angle filter in Photoshop CC. Therefore it can sometimes be best to not use the Boundary Warp slider and instead make use of the Adaptive Wide Angle filter in Photoshop to carry out the necessary distortion corrections.

Panorama Photo Merge performance

Panorama Photo Merges have been optimized to run up to twice as fast compared with the previous version of Lightroom, plus you can create panorama Photo Merges when only Smart Previews are available. Multiple merge operations are added to a queue for better management. However, queued jobs are only initiated when the CPU usage is below a tolerable limit. Panorama Photo Merges also respect localized adjustments, such as spot removal work that may have been applied before merging. For example, if you have a dirty sensor, you can use the Spot removal tool and sync the edits across all the frames before you merge them. This might save you time carrying out repeat spotting work on the final merged image.

Combined HDR Panorama Photo Merge

This latest version of Lightroom allows you to merge panorama images that include bracketed exposures. This means you can combine the Merge to HDR and Merge to panorama processes in a single step. To do this you’ll need to photograph a scene by shooting an HDR bracketed sequence at each step as you capture the panoramic sweep. In Lightroom, make a selection of the captures and choose Photo  Photo Merge

Photo Merge  HDR Panorama. This pops the dialog shown in Step 2 opposite, where you can choose from the usual projection options, plus whether to Auto Crop, apply Auto Settings, or group within a stack with the source files. There are no options to control the HDR processing though. At the HDR Photo Merge stage, the images are auto-aligned automatically and with Deghosting turned off.

HDR Panorama. This pops the dialog shown in Step 2 opposite, where you can choose from the usual projection options, plus whether to Auto Crop, apply Auto Settings, or group within a stack with the source files. There are no options to control the HDR processing though. At the HDR Photo Merge stage, the images are auto-aligned automatically and with Deghosting turned off.

When you click the Merge button, Lightroom generates a DNG Photo Merge with an -HDR-Pano suffix (the interim HDR DNG files are discarded along the way). If you need more control over the HDR process, it may be best to separately make custom Merge to HDRs first, then select these after to create a panorama. This is because for optimum alignment, you must carry out the HDR Photo Merge first, and then apply the panorama Photo Merge after.

Note

For an HDR Panorama photo merge to work, it is essential that each exposure bracket contains the same number of images and the same exposure offset pattern. For example, if the first set of bracketed exposures is +2, 0, –2, then the same sequence must be applied to all the other photos in the HDR panorama sequence.

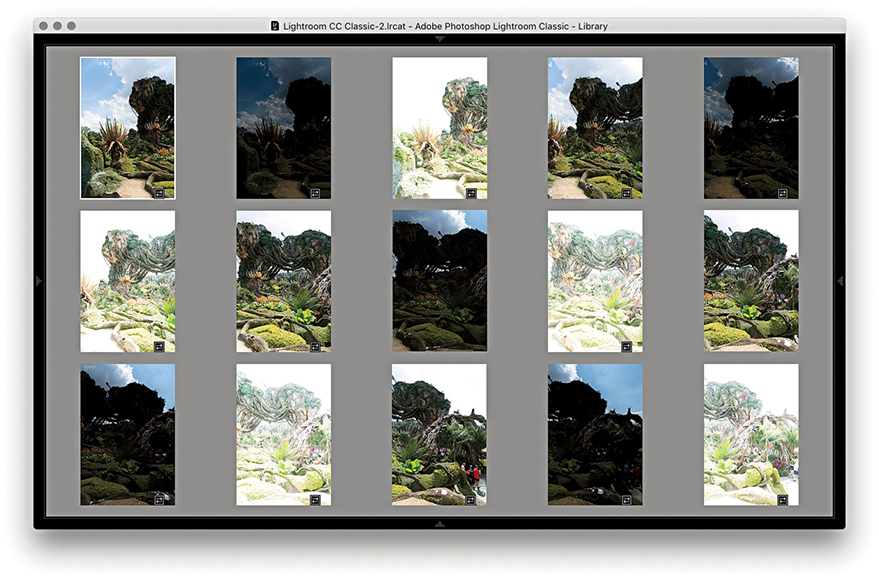

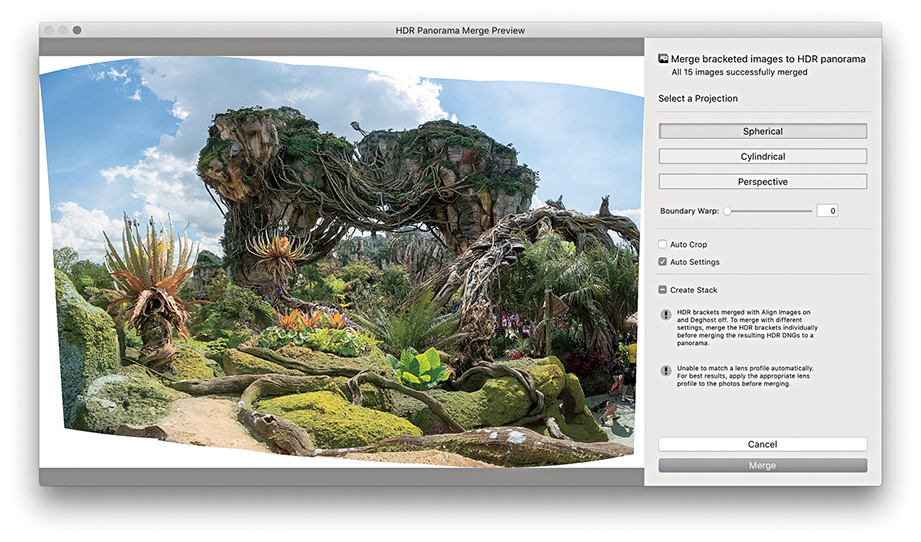

1. First, I selected a series of 15 images to merge as an HDR Panorama. I then choose Photo  Photo Merge

Photo Merge  HDR Panorama.

HDR Panorama.

2. In the HDR Panorama Merge Preview dialog that opened, I was able to adjust the panorama projection method, the Boundary Warp, and whether to apply an Auto Crop and Auto Settings adjustments. When satisfied, I clicked Merge.

Clarity Slider

The Presence section in the Basic panel includes the Clarity slider, which is essentially a local area contrast adjustment control. The Clarity effect is achieved by creating variable amounts of contrast by adding soft halos to the edges in a photograph. This builds up the contrast in the midtone areas based on the edge detail in the image. The halos are generated with the same underlying tone mask algorithm that is utilized for the Highlights and Shadows sliders, which makes the halos less noticeable. The net effect is that a positive Clarity adjustment boosts the apparent contrast in the midtones but does so without affecting the overall global contrast. Normally, you would want to start with a Clarity setting of around 10 so as not to overdo the effect too much. But as you increase the Amount, this strengthens the midtone contrast, which in turn makes the midtone areas appear more crisp.

You can also add Clarity to an image using the localized adjustment tools. Later you will see a few examples of how you can apply Clarity adjustments with the Adjustment Brush.

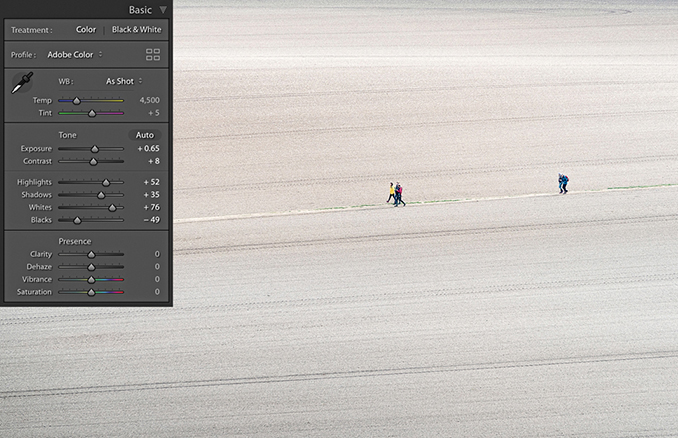

1. This shows a photograph of a plowed field with the Clarity slider at the default 0 setting.

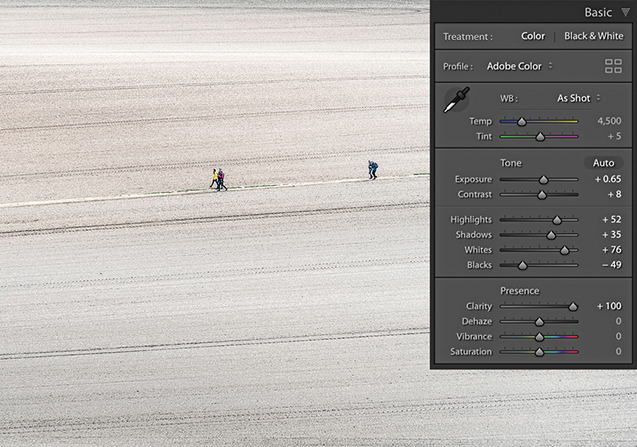

2. For comparison, I set the Clarity slider to +100. I took the slider all the way to the maximum setting to create the most dramatic difference between this and the previous screen shot. You can see much more midtone contrast in the texture of the field.

Images that benefit most from adding Clarity

All image adjustments are destructive. So, one way or another, you will end up either expanding the tones in an image, which stretches the levels farther apart, or compressing the tones by squeezing the levels closer together. Where tone areas become compressed and portions of the tone curve become flattened, you consequently lose some of the tonal separation that was in the original. A positive Clarity adjustment can, therefore, be used to expand areas of flat tone and enhance detail that was in the original capture image. The kinds of photos that benefit most from adding Clarity are those that have soft midtone contrast where you want to make the image look more contrasty, but without causing the shadows or highlights to clip. For example, when I use the Soft Proofing feature and preview photos that are to be printed on a matte paper, I find it helps to increase the Clarity to counter the lack of contrast seen in the soft preview image.

Negative Clarity adjustments

A negative Clarity adjustment does the exact opposite of a positive Clarity adjustment. It softens the midtones and does so in a way that produces an effect not too dissimilar to a traditional darkroom diffusion printing technique (see steps below). The net result is that you can create some quite beautiful diffuse soft-focus image effects, and negative clarity is particularly suited to black-and-white photography.

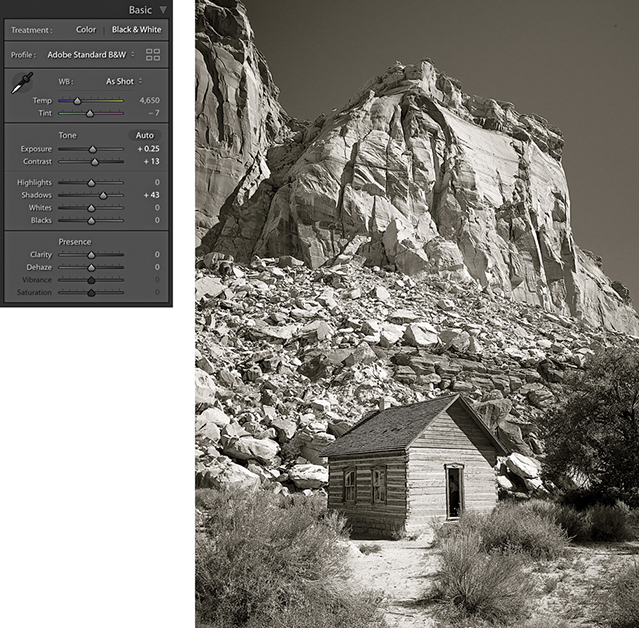

1. With the Clarity set to 0, this is a nice picture with lots of sharp detail, but it is also a good example to show the pseudo-diffusion printing technique.

2. In this step, I applied a –90 Clarity adjustment. As you can see, the negative Clarity adjustment created a kind of diffuse printing effect.

Dehaze Slider

The Dehaze slider is now found in the Basic panel. This change was much requested, and Adobe has now responded. However, while this can make swapping between the Clarity and Dehaze sliders easier, the Dehaze is still essentially an Effects-type adjustment and should therefore be used with some caution when making Basic panel adjustments.

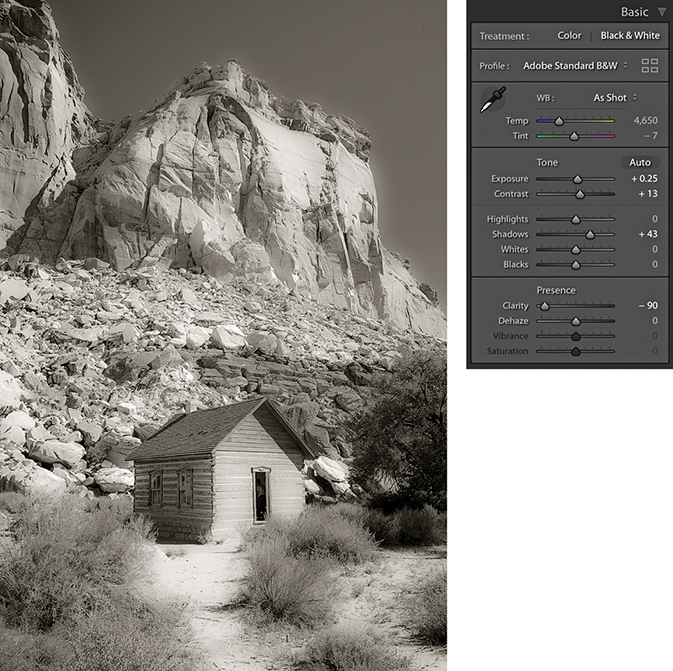

Dehaze adjustments

The Dehaze slider (Figure 4.55) can be used to compensate for atmospheric haze in photographs, as well as mist, fog, or anything that contributes to the softening of contrast and detail in a scene. For example, you can use the Dehaze slider to improve the contrast in photographs taken of a starry night sky and reduce the effects of light pollution. Drag the slider to the right to apply a positive value and remove haze from a scene. Basically, the results you get are in some ways similar to adjustments made using the Clarity slider, but a Dehaze effect is overall a lot stronger than what can be achieved using the Clarity slider on its own.

There are a few things to watch out for, though, when working with Dehaze. First, it is recommended you set the white balance first. When you apply a Dehaze adjustment to remove haze, this can emphasize the lens vignetting in an image. It is therefore best to make sure you apply a lens profile correction (or a manual vignetting correction) first to remove the lens vignetting before you apply a Dehaze slider adjustment. Similarly, a positive Dehaze adjustment will emphasize any sensor spots (although this can easily be dealt with using the Spot Removal tool).

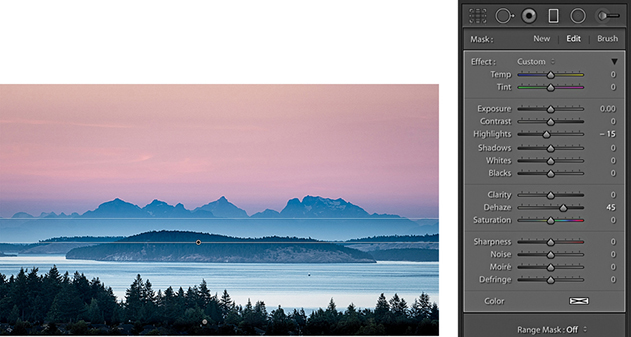

Dehaze as a localized adjustment

Dehaze can be applied as a localized adjustment using the Graduated Filter, Radial Filter, or Adjustment Brush. This makes the effect more useful for treating landscape images where, very often, the foreground at the bottom of the frame will look fine and it is only the subject matter in the distance from the middle to the top of the frame that needs correcting. You don’t really want a Dehaze adjustment to be applied to areas that don’t need it, so it is great you can apply Dehaze using the localized adjustment tools. Personally, I find Dehaze adjustments to be more useful when applied as a localized adjustment.

Negative Dehaze adjustments

Dragging the slider to the left can add haze and make an image look more foggy. For example, you can apply a negative Dehaze using the Adjustment brush to create smoke and mist effects. When using Version 5 and applying negative amounts of Dehaze, there is less noise and the range of adjustment has been updated. At –100 the overall effect is stronger, but there is better preservation of the shadows at in-between settings up to around –90.

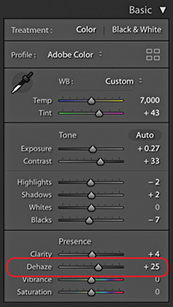

1. This landscape photograph was shot just before sunset. I applied the Basic panel adjustments shown here to optimize the tone contrast.

2. I selected the Graduated Filter tool and applied a positive Dehaze adjustment to the top half of the photograph to bring out more detail in the distant hills and clouds.

3. I then reset the Graduated Filter settings and, instead, applied a negative Dehaze adjustment to add haze to this scene.

Vibrance and Saturation

The Vibrance and Saturation sliders are located at the bottom of the Basic panel in the Presence section (Figure 4.56). Both can be used to adjust the saturation in an image. The main difference between the two is that the Saturation slider applies a linear adjustment to the color saturation, whereas a Vibrance adjustment uses a nonlinear approach. In plain English, this means that when you increase the Vibrance, the less saturated colors get more of a Saturation boost than those colors that are already saturated. This can be of a real practical benefit when you are applying a Saturation adjustment to a picture and you want to make the softer colors look richer, but you do not want to boost the color saturation at the expense of losing important detail in the already bright colors. The other benefit of working with Vibrance is that it has a built-in Caucasian skin color protector that filters out colors that fall within the skin color range. This can be useful if you are editing a portrait and you want to boost the color of someone’s clothing, but at the same time, you do not want to oversaturate the skin tones.

With most photographs, Vibrance is the only saturation control you will want to use. However, the Saturation slider still remains useful, because a Saturation adjustment can be used to make big shifts to the saturation, such as when you want to dramatically boost the colors in a photograph or remove colors completely. If you examine what happens when you apply an Auto Settings adjustment, you’ll notice how Lightroom tends to apply both Vibrance and Saturation, but nearly always more Vibrance than Saturation. Figure 4.57 shows some examples of Saturation and Vibrance adjustments.

The main thing to understand is that a positive Saturation adjustment will boost all colors equally. In the example shown in Figure 4.57, it made all the colors equally more saturated and as a consequence, there was some color clipping in the red nose of the mandrill monkey. In the version next to it, I increased the Vibrance to +100. This resulted in an image where the reds in the nose did not receive such a big color boost, but the other colors, which were less saturated to begin with, did receive a major boost in saturation. However, they were not oversaturated to the point where any of the color channels were clipped. This shows how the Vibrance adjustment can be effective in preserving more tonal detail as you boost the color saturation. Dragging the sliders the other way, a full negative Saturation adjustment, will desaturate all the colors completely, whereas a negative Vibrance can be used to gently desaturate a photo. As you can see, a negative Vibrance of –100 produced a subtle, desaturated look. Ultimately, many images can benefit from a small Vibrance boost, although in this example, because I really wanted to emphasize the colors in the mandrill’s face, I felt the optimum adjustment would be +50 Vibrance. This is much more Vibrance than I would apply generally, but it seemed an appropriate setting to use for this particular photograph.

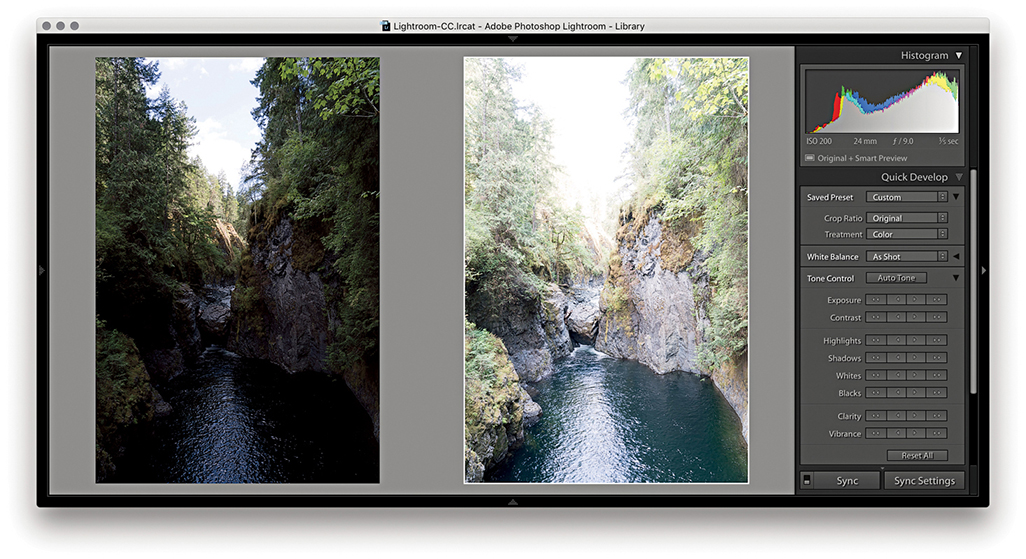

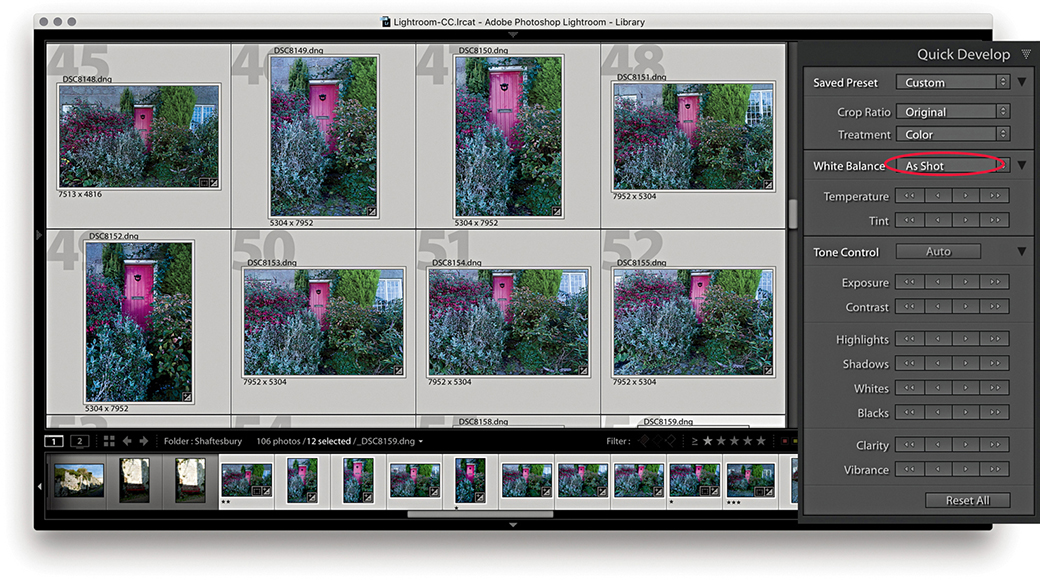

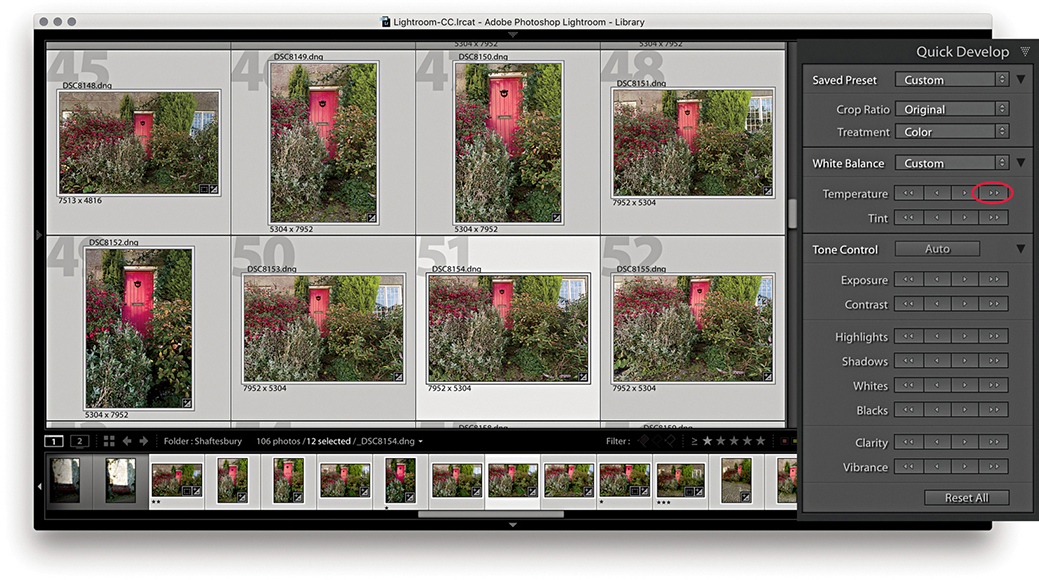

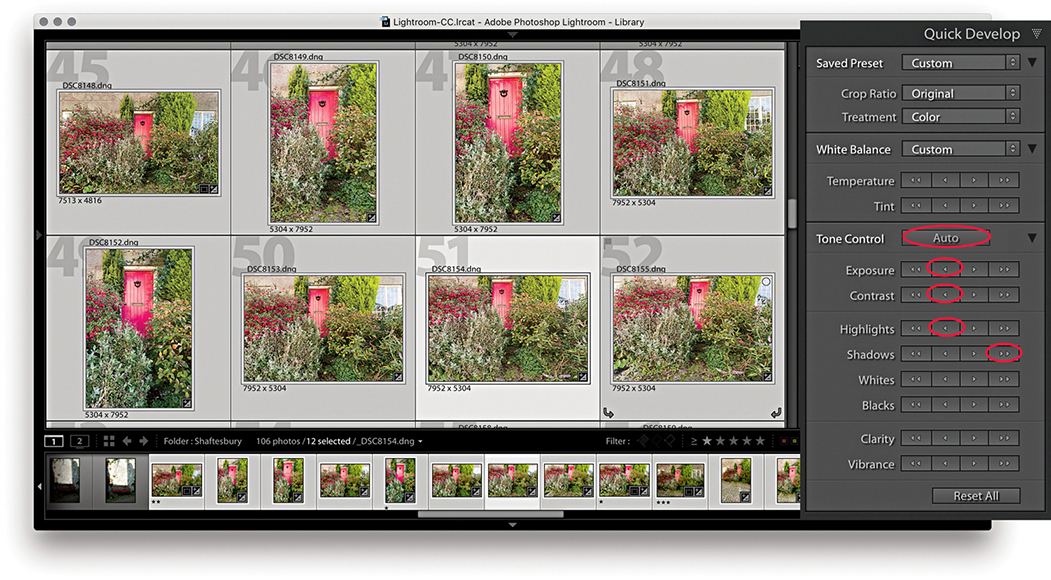

Quick Develop Panel Tone Adjustments

All the Develop controls discussed so far are also accessible via the Quick Develop panel in the Library module (Figure 4.58). To see all the controls shown here, you need to click the expansion arrows on the right. To restore an adjustment to its default setting, click the name of the adjustment. Using the Quick Develop panel, you can apply Basic panel tone and color adjustments without having to leave the Library module. And, any adjustments you make here simultaneously update the settings in the Develop module Basic panel. Quick Develop adjustments can be applied to multiple selected images in a Grid view or in the Filmstrip. But the main difference with Quick Develop is that Quick Develop adjustments are always applied relative to the current Develop settings. For example, if you select a number of images that have already had different Exposure settings applied to them, you can use the Exposure buttons in Quick Develop to make those photos relatively lighter or darker (as opposed to synchronizing all of the photos with the same Exposure value).

Using Quick Develop is the same as working in the Develop module, except you don’t have the same fine degree of control. It is therefore ideal for making first-pass edits, where you still need to do most of your work in the Library module (such as rating images and adding metadata) without having to switch back and forth between Library and Develop to apply image adjustments. However, it is important to bear in mind that the Library module preview will not be as accurate as that displayed in the Develop module. The Library module previews are Adobe RGB rendered, whereas when you edit a photo in the Develop module, the image is edited using the wider-gamut Lightroom RGB space and the image preview you see is generated on the fly via the Lightroom Camera Raw engine. Therefore, the previews you see in Develop are always going to be the most accurate. Also, when you edit a photo using the Quick Develop controls in the Library module, the quality of the Loupe view preview will be dependent on whatever settings you have selected in the Catalog Settings File Handling section. You have to bear in mind here that the Library preview mechanism is primarily designed to generate decent-quality previews that enable fast Library module browsing; it is not so ideal for assessing Develop settings adjustments. You will also notice that the Histogram panel in the Library module features an animated transition when adjusting the values in the Quick Develop panel.

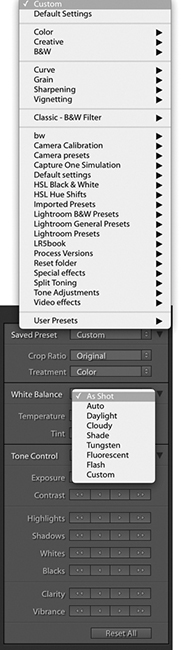

To apply Quick Develop adjustments, go to the Library module and select a photo, or make a selection of several photos. Next, you can click to access the Saved Preset list shown in Figure 4.59 and choose a default setting or a previously saved preset as your starting point (the Develop settings are arranged here in a hierarchical list).

The Treatment menu lets you decide whether to process an image in Color or Black & White. To be honest, I think it is better to memorize the  shortcut as a means for toggling between the Color and Black & White modes and rely on the Treatment menu as an indicator of which mode a photo is in.

shortcut as a means for toggling between the Color and Black & White modes and rely on the Treatment menu as an indicator of which mode a photo is in.

Next, we come to the White Balance options. If you are shooting with a camera set to Auto White Balance mode, or you used a white balance that was correct for the lighting conditions at the time of shooting, you will probably want to leave this set to As Shot. Otherwise, you can click the White Balance menu (Figure 4.45) and choose one of the preset settings listed there, or select the Auto setting, and Lightroom will calculate an optimized White Balance setting for you (or use the  [Mac] or

[Mac] or  [PC] shortcut). With the Temperature buttons, if you click the left-arrow buttons, the image becomes incrementally cooler, and if you click the right-arrow buttons, the image becomes warmer. The Tint buttons can be used to apply a green/magenta bias. Clicking the left-arrow buttons makes a photo more green, and clicking the right-arrow buttons makes it more magenta. The single-arrow buttons produce small shifts in color, and the double-arrow buttons produce more pronounced color shifts.

[PC] shortcut). With the Temperature buttons, if you click the left-arrow buttons, the image becomes incrementally cooler, and if you click the right-arrow buttons, the image becomes warmer. The Tint buttons can be used to apply a green/magenta bias. Clicking the left-arrow buttons makes a photo more green, and clicking the right-arrow buttons makes it more magenta. The single-arrow buttons produce small shifts in color, and the double-arrow buttons produce more pronounced color shifts.

Clicking the Auto button applies an Auto Settings adjustment ( [Mac] or

[Mac] or  [PC]). This automatically adjusts the Exposure, Contrast, Highlights, Shadows, Whites, Blacks, Vibrance, and Saturation settings. But as mentioned earlier, an Auto Settings adjustment applied in the Library module mode won’t be as accurate as one applied via the Develop module.

[PC]). This automatically adjusts the Exposure, Contrast, Highlights, Shadows, Whites, Blacks, Vibrance, and Saturation settings. But as mentioned earlier, an Auto Settings adjustment applied in the Library module mode won’t be as accurate as one applied via the Develop module.

Process version conflicts

If there is a process version conflict when two or more photos are selected, the Quick Develop buttons will appear dimmed (see page 164).

The tone and color controls

With the remaining tone and color controls, I advise you to start by adjusting the Exposure amount first, because the Exposure is critical for determining the overall brightness. A  -click on the Exposure single-arrow button is equivalent to a 0.17-unit shift in the Develop module, a single-click equivalent to a 0.33-unit shift, and a click on the double-arrow button equivalent to a 1.0-unit shift.

-click on the Exposure single-arrow button is equivalent to a 0.17-unit shift in the Develop module, a single-click equivalent to a 0.33-unit shift, and a click on the double-arrow button equivalent to a 1.0-unit shift.

After you set the Exposure, you may want to adjust all the other tone control buttons. Here, a  -click on the single-arrow button is equivalent to a 3.0-unit shift in the Develop module, a single-click on the single-arrow button equivalent to a 5.0-unit shift, and a double-arrow click equivalent to a 20.0-unit shift.

-click on the single-arrow button is equivalent to a 3.0-unit shift in the Develop module, a single-click on the single-arrow button equivalent to a 5.0-unit shift, and a double-arrow click equivalent to a 20.0-unit shift.

If you hold down the  key, the Clarity buttons in the Quick Develop panel switch to Sharpening buttons (Figure 4.60). In this

key, the Clarity buttons in the Quick Develop panel switch to Sharpening buttons (Figure 4.60). In this  key mode, the Sharpening controls in Quick Develop are equivalent to Sharpening Amount slider adjustments in the Develop module Detail panel. Although you do not have access to the other three sharpening sliders, you can still make an initial sharpening adjustment before you get around to fine-tuning the other settings later. As you hold down the

key mode, the Sharpening controls in Quick Develop are equivalent to Sharpening Amount slider adjustments in the Develop module Detail panel. Although you do not have access to the other three sharpening sliders, you can still make an initial sharpening adjustment before you get around to fine-tuning the other settings later. As you hold down the  key, the Vibrance buttons switch to become Saturation buttons. With both the Sharpening and Saturation controls, a single-arrow click is equivalent to a 5-unit shift in the Develop module, and a double-arrow click is equivalent to a 20-unit shift.

key, the Vibrance buttons switch to become Saturation buttons. With both the Sharpening and Saturation controls, a single-arrow click is equivalent to a 5-unit shift in the Develop module, and a double-arrow click is equivalent to a 20-unit shift.

key held down.

key held down.The Reset All button at the bottom resets all the Develop settings that have been applied to a photo (and not just those that have been applied via Quick Develop) to their default import settings. You can also use the  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) shortcut. However, this action resets all the Develop settings to a zeroed or default state, so use this button with caution.

(PC) shortcut. However, this action resets all the Develop settings to a zeroed or default state, so use this button with caution.

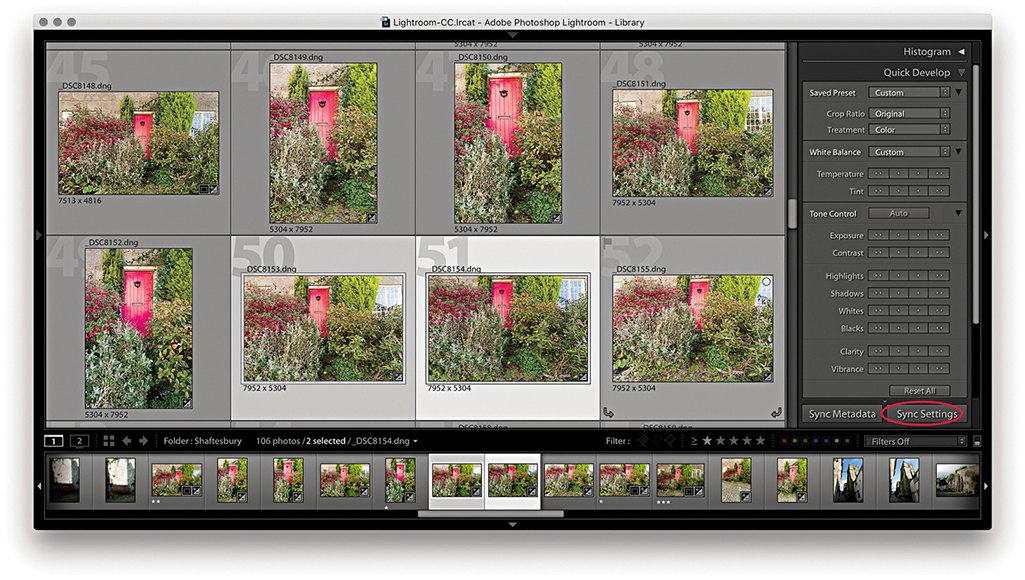

A typical Quick Develop workflow

The following steps show how you might want to use the Quick Develop panel while working in the Library module.

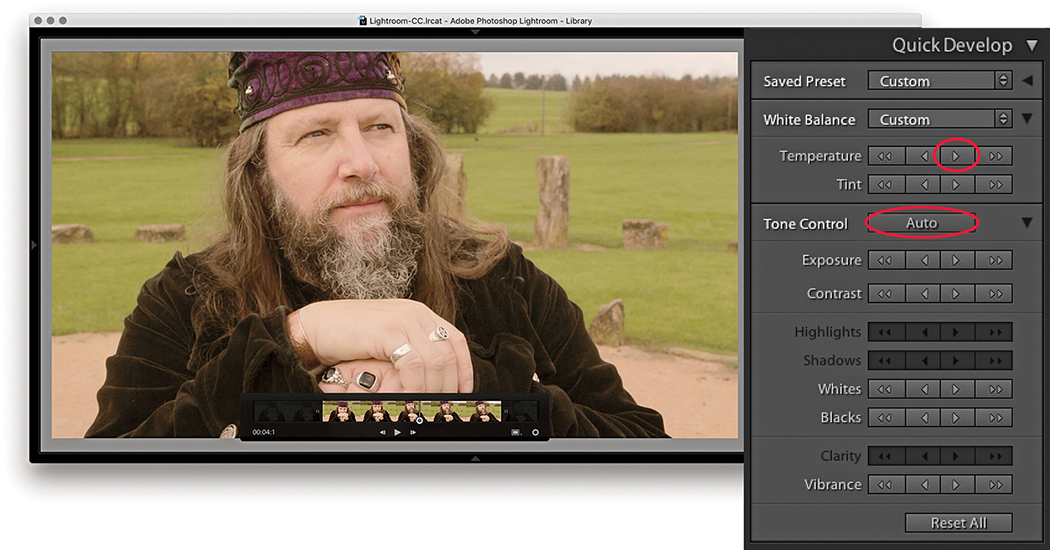

1. To begin, I made a selection of the photos I wanted to edit. These photographs were shot in raw mode and imported using the Default Develop settings and As Shot White Balance (circled above).

2. I wanted to warm the colors in the selected photos, so I clicked the double-arrow button (circled above) to make the selected photos appear warmer.

3. I then wanted to apply some tonal edits. I clicked the Auto button followed by the Exposure, Contrast, Highlights, and Shadows buttons (circled above). This improved the brightness and contrast.

4. Alternatively, you can work on the images one at a time in Quick Develop. I double-clicked one of the photos to work in the Loupe view, then I reduced the Exposure, darkened the Highlights, and lightened the Shadows.

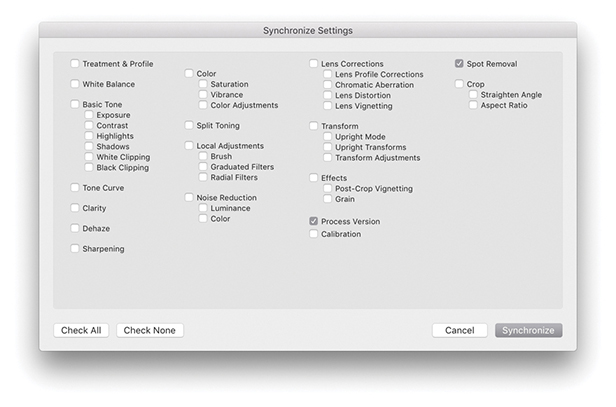

5. I selected this recently edited image and the photo next to it and clicked the Sync Settings button at the bottom (circled above).

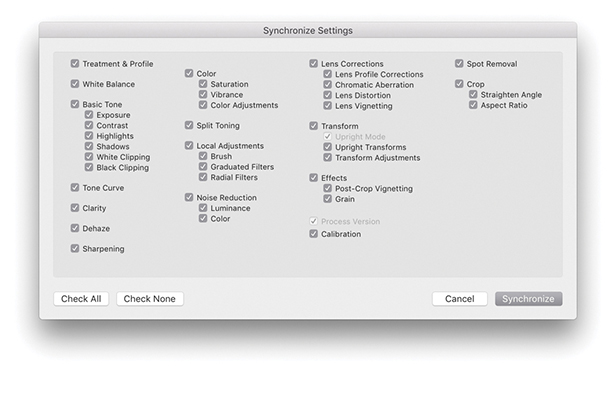

6. This opened the Synchronize Settings dialog, where I clicked the Check All button to select all settings. I then clicked the Synchronize button to synchronize the settings across the two photos selected in Step 5.

Note

The Sync Settings button can be used to synchronize all Develop module settings, not just those applied via the Quick Develop panel.

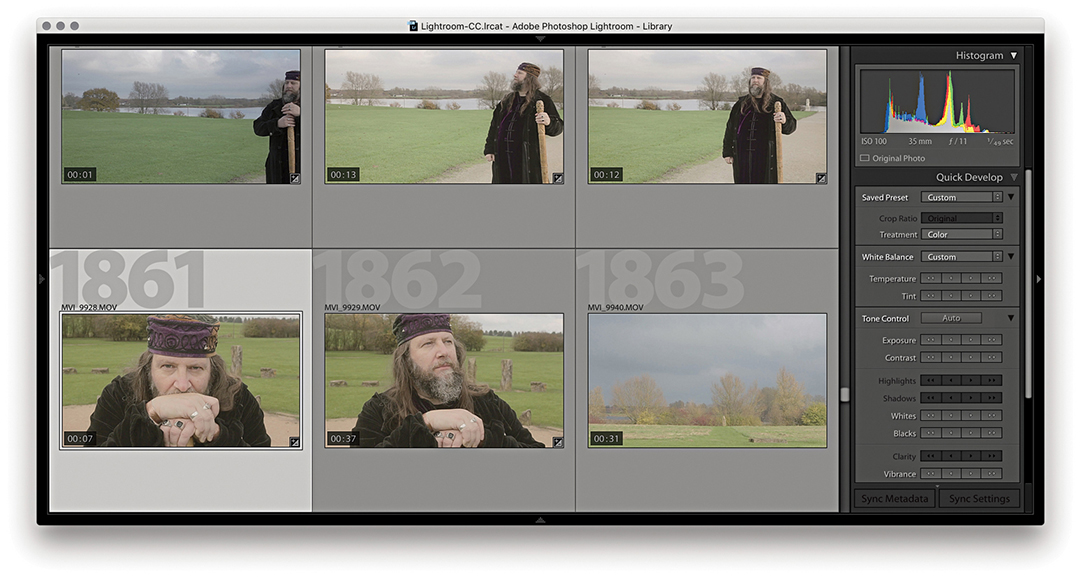

Editing Video Files in Quick Develop

As well as being able to play video files directly in the Library module Loupe view, some limited video editing is possible using the Quick Develop panel. Lightroom does not yet offer full video-editing features—for that, you will want to use dedicated video-editing software. But it is nonetheless possible to at least view and edit video clips in Lightroom. So, let me run through some of the key features. Figure 4.61 shows how video files are displayed in the Library module Grid view. In the Library Loupe view, you can navigate a clip to play it and edit the start and end times; you also have access to some of the Quick Develop image-adjustment options that will let you adjust the White Balance, Exposure, Contrast, Whites, Blacks, and Vibrance.

Loupe view video-editing options

There are a few selectable items in the options menu (which are shown in the following steps). Capture Frame can be used to extract a frame and automatically add this to the folder and to the catalog as a separate JPEG image. The Set Poster Frame option allows you to select a frame other than the start frame and then use it as the thumbnail preview in Lightroom (Slideshow will then also use the poster frame). Lastly, there is the Display Trim Time as SMTPE option. This is an absolute time code that is used when you want to synchronize different devices (providing they are compatible). It is something that is really of more interest to those who are carrying out professional video editing. Personally, although I find Lightroom useful for importing video clips at the shoot stage, I then do all the main editing and grading using Adobe Premiere.

Note

There is a Video mode for the Metadata panel, although most cameras record very little metadata.

1. When you inspect a video file in the Lightroom Library module Grid view, you can quickly track all the frames in a sequence by hovering over the thumbnail and moving from left to right.

2. I double-clicked the thumbnail in the Grid to go to the Loupe view. Here, I could click the Play arrow button or tap the Spacebar to play the selected movie clip (click again to pause). I could quickly navigate a video clip by dragging the frame-selection button and click the gear button (circled) to reveal the key frames. If “Show frame number when displaying video time” is selected in the Loupe View Options, the frame number is displayed after the minutes/seconds timeline display.

3. I dragged the start and end points to trim the movie sequence (You can also use  to set the input point and

to set the input point and  to set the output point for a clip). I then selected a midway point in the video clip and selected Set Poster Frame from the Settings menu. This updated the thumbnail preview in the Grid view with a more relevant frame from the movie sequence.

to set the output point for a clip). I then selected a midway point in the video clip and selected Set Poster Frame from the Settings menu. This updated the thumbnail preview in the Grid view with a more relevant frame from the movie sequence.

4. The Quick Develop controls can be used to apply basic Develop edits. In this example, I made the sequence a few clicks warmer to remove the slight bluish cast and also clicked the Auto button to optimize the tone balance.

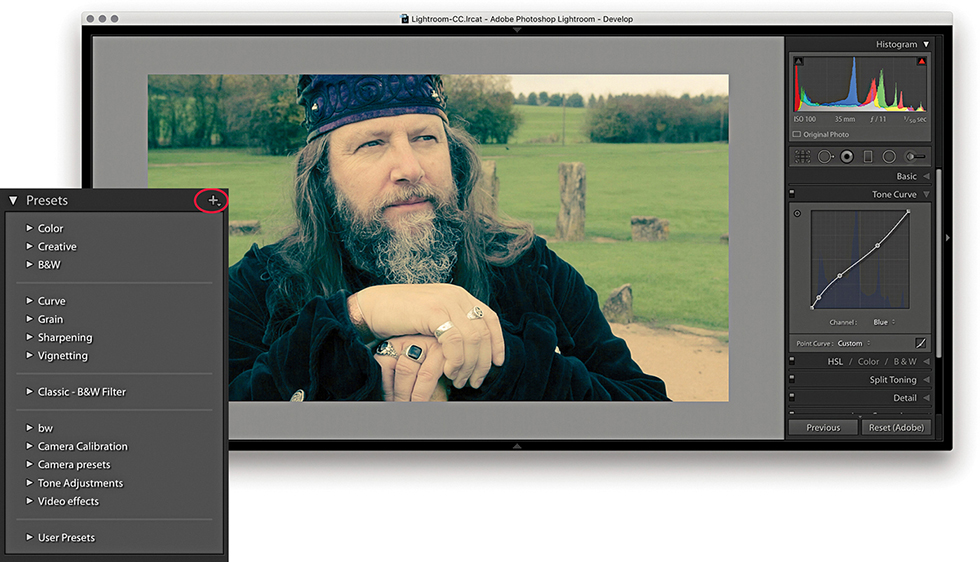

5. Although you cannot edit videos extensively in the Quick Develop panel or Develop module, you can make use of saved presets to apply some types of Develop adjustments. To do this, I clicked the Settings menu and selected Capture Frame. This created a JPEG photo from the selected frame stacked with the original.

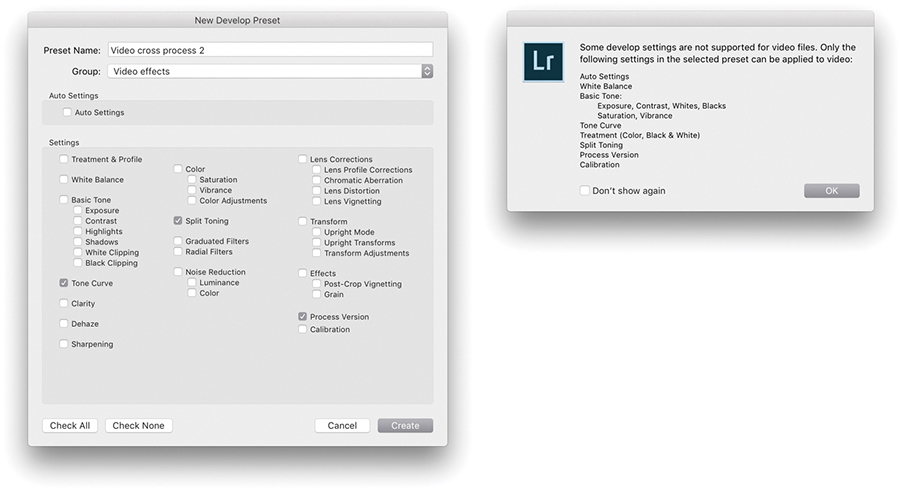

6. I was then able to edit the captured JPEG using the Develop module controls. Here, I applied a Tone Curve plus a Split Toning adjustment (which you can’t do using Quick Develop). I was thereby able to create an adjustment that produced a cross-process color effect.

7. I then clicked the + button in the Develop module Presets panel and saved the edited setting as a new preset. Although you can save any Develop setting as a preset, there is still a limited range of settings that can be applied to a video clip. Therefore, when applying a preset to a video file, the dialog shown here warns not all types of settings are supported.

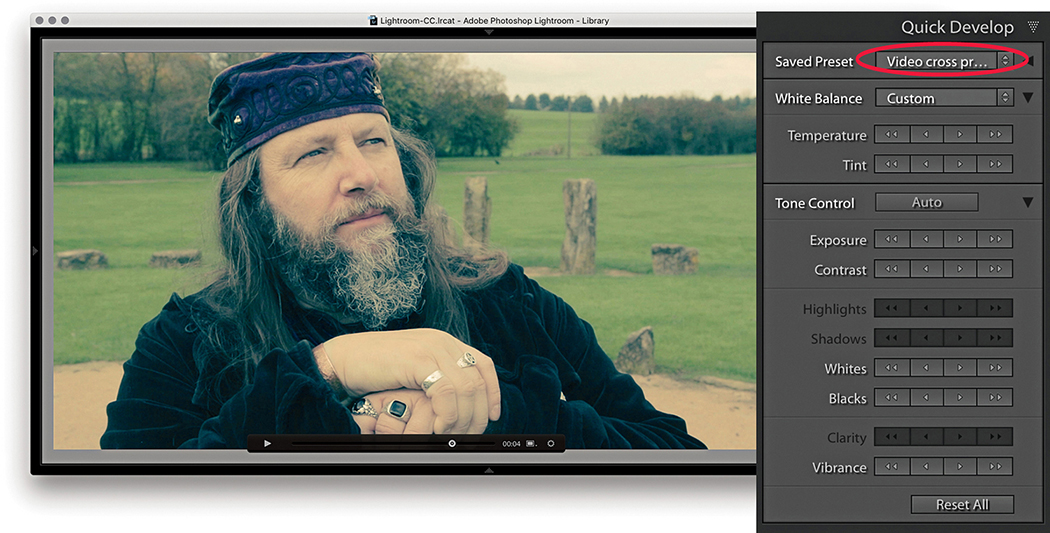

8. Finally, I returned to the video file in the Library module and selected the preset I had just created from the Saved Preset menu in the Quick Develop panel.

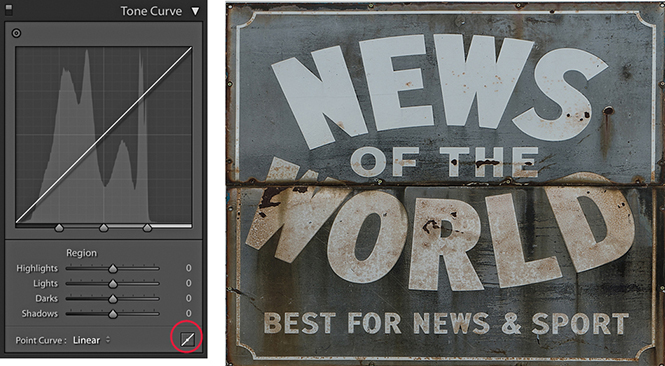

The Tone Curve Panel

The Tone Curve controls (Figure 4.62) offer a unique approach to tone curve mapping, where the tone curve is modified through slider control (parametric) adjustments. The Tone Curve controls are presented in this way to encourage people to make Tone Curve adjustments based on descriptive criteria. The Tone Curve panel now features a larger graph. And, you will notice the histogram display is more prominent. If you are used to working with the point-edit Curves dialog in Photoshop, the Lightroom method may appear restrictive at first, but the Tone Curve slider controls in Lightroom can often inspire you to create tone curve shapes that are quite unlike any curve shape you might have applied when using the traditional point-curve method. The parametric Tone Curve sliders now make curves adjustments accessible to everyone, but the good news is, you can still manipulate the curve graph directly by clicking a point on the curve and dragging up or down to modify that particular section of the curve. Best of all, you can edit the curve by targeting an area of interest in the image directly. You can also use the keyboard Arrow keys: The Up and Down Arrows can be used to increase or decrease the tone values (the Left and Right Arrow keys are reserved for navigating images in the Filmstrip). Holding down the  key as you adjust the values applies larger incremental adjustments. If you enable the Target Adjustment tool button

key as you adjust the values applies larger incremental adjustments. If you enable the Target Adjustment tool button  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC), you can then click any part of the image and drag up or down to make the tones there lighter or darker. When you start using the Target Adjustment tool editing method to refine the tones in an image, you will not necessarily even need to look at the Tone Curve panel. You can turn off the Target Adjustment tool by clicking the Target Adjustment tool button again, pressing

(PC), you can then click any part of the image and drag up or down to make the tones there lighter or darker. When you start using the Target Adjustment tool editing method to refine the tones in an image, you will not necessarily even need to look at the Tone Curve panel. You can turn off the Target Adjustment tool by clicking the Target Adjustment tool button again, pressing  , or by using the

, or by using the  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) shortcut.

(PC) shortcut.

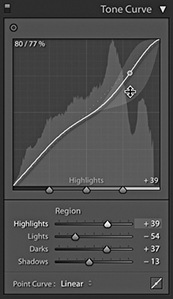

The four main sliders for controlling the tone curve are Highlights, Lights, Darks, and Shadows. These controls also provide a shaded preview of the range of the shapes an individual Tone Curve slider adjustment can make. In Figure 4.62, I was in the process of adjusting the Highlights slider, and you will notice how the histogram in the Histogram panel is mirrored in the curve graph and both are updated as you edit the Tone Curve controls. The gray-shaded area represents the limits of all possible tone curve shapes I could create with this particular slider in conjunction with the other current slider settings. For those who understand curves, this provides a useful visual reference of how the curve can look.

As mentioned earlier, the Basic panel is used to apply the main tone adjustments. It is important to understand that these are all applied upstream of any Tone Curve adjustments, so the Tone Curve slider is an image-adjustment control that you always want to apply after you have made the initial Basic panel adjustments.

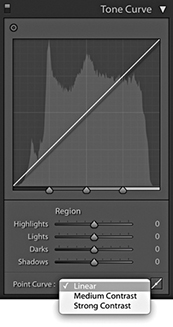

The layout of the Tone Curve panel is influenced to some degree by the legacy constraints of the Adobe Camera Raw plug-in. It has been necessary to ensure that the settings applied to an image via Camera Raw in Photoshop are also recognized (and made accessible) when the same image is opened via the Develop module in Lightroom. I mention all this as an explanation for the presence of the Point Curve menu at the bottom of the Tone Curve panel (Figure 4.63).

In the early days of Camera Raw, some purists argued that the tone curve for processing raw files should always default to a linear mode, and if you wanted to add contrast, it was up to you to edit the curve how you wanted. Meanwhile, almost every other raw converter program was applying a moderate amount of contrast to the curve by default. The reason for this was because most photographers tend to like their pictures with a more contrasty and film-like look as a standard setting. For example, Capture One applies adaptive tone adjustments to newly imported photos that in most instances produce a more contrasty default look compared to Lightroom. Consequently, the Adobe Camera Raw plug-in has evolved to offer three choices of curve contrast: Linear, Medium Contrast, and Strong Contrast. So, the Point Curve menu in the Tone Curve panel (not to be confused with the Point Curve editing mode discussed on page 244) is mainly there to allow you to match up raw files that have been imported with legacy Camera Raw settings. With Version 1/Version 2, the default setting for raw files was Medium Contrast. With Version 5, the default point curve now says Linear and, as you would expect, presents a straight line curve. But this is, in fact, applying the same underlying curve setting as the previous default Process Version 1/Version 2 Medium Contrast tone curve.

Basically, the current Linear curve does exactly the same thing as the older Version 1/Version 2 curve: It applies more of a kick to the shadows to make them slightly darker and lightens the highlights slightly. This also brings the benefit of tone curve setting compatibility between non-raw and raw images. Non-raw images have always defaulted to a linear tone curve shape. This remains the case in Version 5. Therefore, the starting point for both raw and non-raw images is now the same: a linear tone curve representation. The Point Curve options are nothing more than a curve shape setting, and these can be used as a starting point when making further edits to the tone curve.

If you convert a Version 1/Version 2 tone curve to Version 5, the tone curve shape will appear adjusted (even though the parameter values will actually remain the same). Therefore, Tone Curve settings are now process-version-specific. This means whenever you save a Develop preset that includes a Tone Curve setting, you are obliged to include saving the Process Version setting along with the Tone Curve setting.

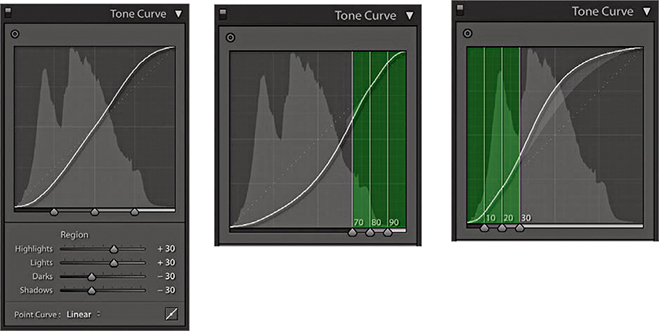

The tone range split points at the bottom of the tone curve let you restrict or broaden the range of tones that are affected by the four Tone Curve sliders (Figure 4.64). Adjusting each of the three tone range split points allows you to further fine-tune the shape of the curve. For example, moving the dark tone range split point to the right offsets the midpoint between the Shadows and Darks adjustments. These adjustment sliders are particularly useful for those instances when you are unable to achieve the exact tone localized contrast adjustment you are after when using the Tone Curve sliders on their own (see also page 254).

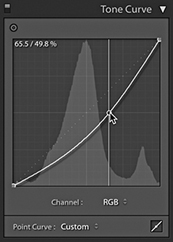

Point Curve Editing Mode

To switch to the Point Curve editing mode (Figure 4.65), click the button circled in Step 1 below. In this mode, you can click on the curve to add new control points and drag these up or down to modify the curve shape. The before/after value of the control point that is being moved is shown in the top-left corner of the editor view as a percentage value. When selecting an existing control point to move, you do have to click within a few pixels of the control point on the curve. It can help here to hold down the  key as you adjust individual control points. This reduces the sensitivity of tracking movements by a factor of ten. You can also click to select the Target Adjustment tool:

key as you adjust individual control points. This reduces the sensitivity of tracking movements by a factor of ten. You can also click to select the Target Adjustment tool:  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC). As with the Parametric editing mode, you can use up or down movements to make the selected region of the curve lighter or darker.

(PC). As with the Parametric editing mode, you can use up or down movements to make the selected region of the curve lighter or darker.

Unlike the Adjustment panel in Photoshop or the Point Curve mode for the Tone Curve panel in Camera Raw, Lightroom does not provide modal, keyboard focus when editing the tone curve control points, so you can’t nudge using the keyboard Arrow keys. To delete a selected point, right-click to open the context menu and select Delete Control Point, or double-click a control point. You can save the entire tone curve as a preset, including the Point Curve adjustments, but not separately as a preset. However, you can save custom Point Curve settings via the Point Curve menu (see Step 3).

1. I started with a photo to which I had applied a Linear curve. I clicked the Point Curve button (circled) to switch to the Point Curve editing mode.

2. I selected the Target Adjustment tool from the top-left corner (circled), clicked in the preview area to add new control points to the tone curve, and dragged up or down to modify the curve shape. The context menu could be used to delete selected control points or flatten the curve.

3. You can use the Point Curve editing mode to either invert the tones in an image or apply a solarized-type look to a photo and use the Point Curve menu at the bottom to save a custom curve setting.

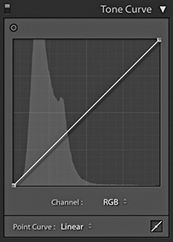

RGB Curves

You also have the option to separately edit the red, green, and blue channel curves, just as you can in Photoshop. To do this, you need to have the Tone Curve panel in Point Curve mode, where you will see the Channel menu (Figure 4.66). This defaults to the RGB Curve editing mode. If you click to open the pop-up menu, you will see the channel curve options shown in Figure 4.67.

Having RGB curves in Lightroom gives you extra tools to work with when adjusting color, and allows you to achieve some unique color effects using just channel curve adjustments. You can use them to correct photos shot under mixed lighting conditions or to produce split-toning effects that are distinctly different from those that can be achieved using the Split Toning panel. Or, as shown here, you can use channel adjustments to apply strong color overlays. Just be aware there is a fair amount of overlap here with the functionality of the White Balance controls (which I would still advise you to use first when correcting color), as well as other controls, such as the Split Toning panel (see page 388).

1. In this example, I prepared an image in which the colors were neutralized and I applied a few Basic panel adjustments only.

2. I then went to the Tone Curve panel in Point Curve editing mode and adjusted the individual red, green, and blue channels to achieve the saturated green color effect shown here.

3. I next edited all three channels to achieve a warm autumn coloring effect.

Tip

The Target Adjustment tool can also be activated by going to the View  Target Adjustment submenu, or by using the following shortcuts:

Target Adjustment submenu, or by using the following shortcuts:  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) to active;

(PC) to active;  , or

, or  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) to deactivate.

(PC) to deactivate.

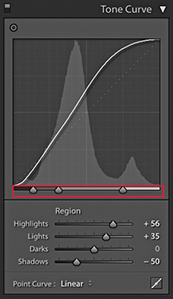

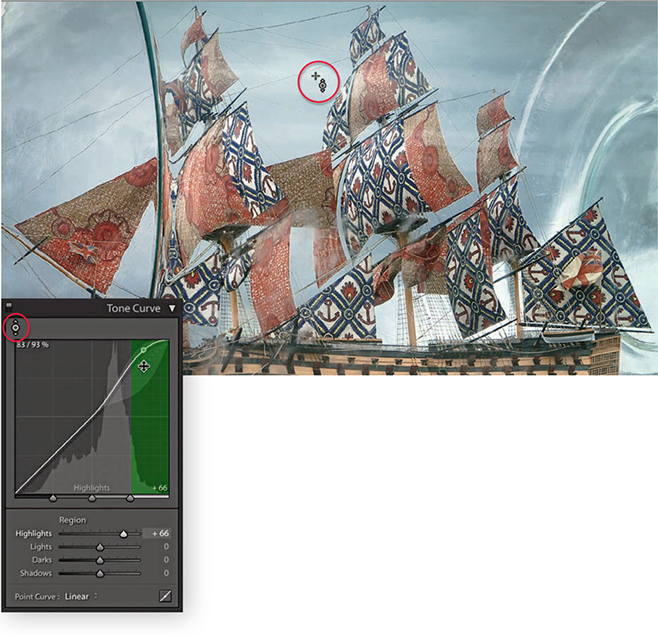

The Tone Curve Regions

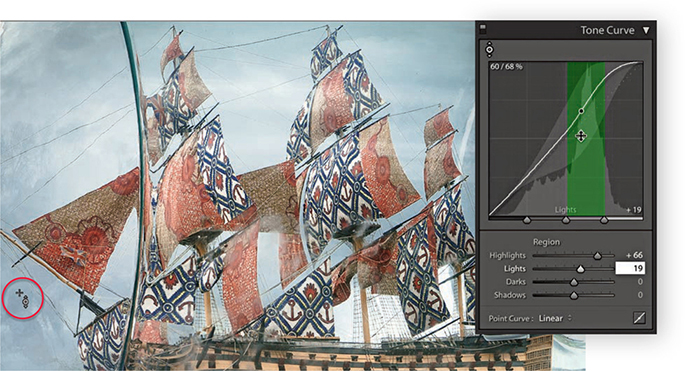

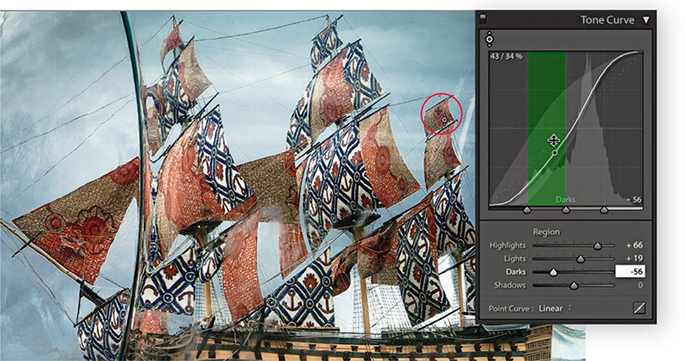

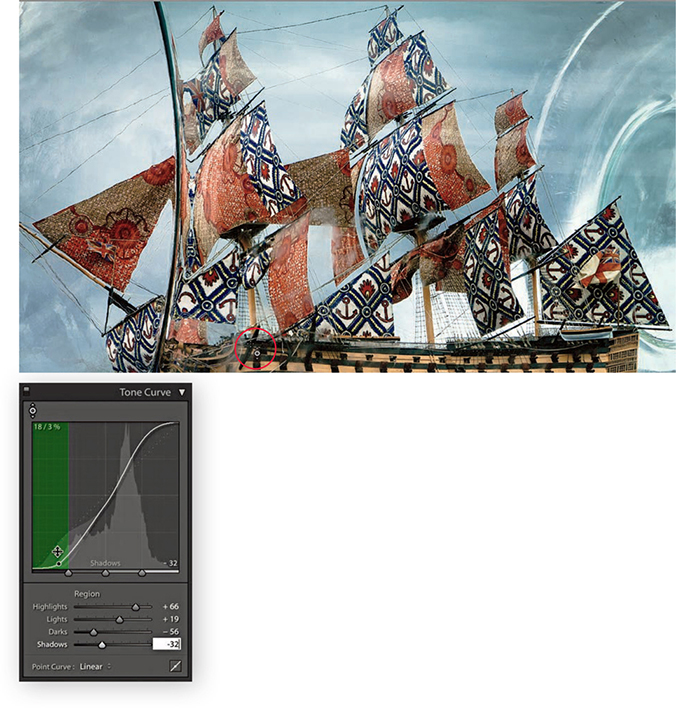

The Tone Curve Zones are evenly divided between the four quadrants of the tone curve. In the following step-by-step example, I show a series of Tone Curve adjustments in which each of these regions gets adjusted. Here, I have highlighted the active quadrants with a green overlay to accentuate these zone regions and show which areas of the curve are being altered. If you want to reset the Tone Curve settings, you can do so by double-clicking the slider names in the Tone Curve panel; you can also reset the Tone Curve adjustments by double-clicking the adjusted region within the tone curve itself.

1. This photograph of a ship in the bottle lacked contrast. I began by adjusting the Highlights slider to make the brightest portion of the image lighter and set the Highlights to +66. This can be done in a number of ways: I could drag the Highlights slider in the Tone Curve panel to the right, or I could make the Highlights field active and use the Up Arrow key to increase the value. If I wanted, I could click anywhere in the green-shaded section of the tone curve and drag the curve upward, or click this portion of the curve and use the Up Arrow key on the keyboard to lighten the highlights. However, in this instance, I clicked the Target Adjustment tool button (circled) to make it active, moved the pointer over the image, and hovered over a highlight area in the clouds. I then clicked and dragged upward to lighten the tones in this selected portion of the curve.

2. Next, I wanted to concentrate on lightening the tones within the Lights zone of the curve. I placed the pointer over a darker area of the sky and dragged upward.

3. I then moved the pointer over one of the sails and dragged downward to darken the Darks zone.

4. Lastly, I adjusted the Shadows by placing the pointer over the shadow area circled above and dragging downward to darken. If you compare the finished step here with where I started, you can see that the combined Tone Curve adjustments increased the image contrast, but in a more controlled way compared to using the Basic panel Contrast slider on its own.

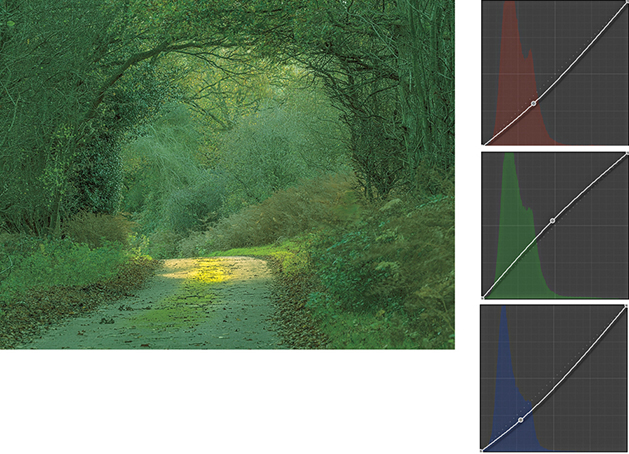

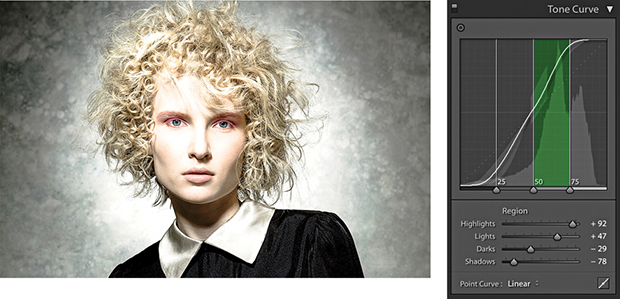

Combining Basic and Tone Curve Adjustments

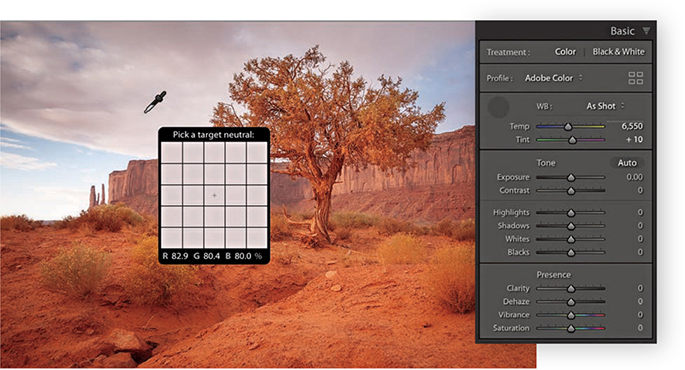

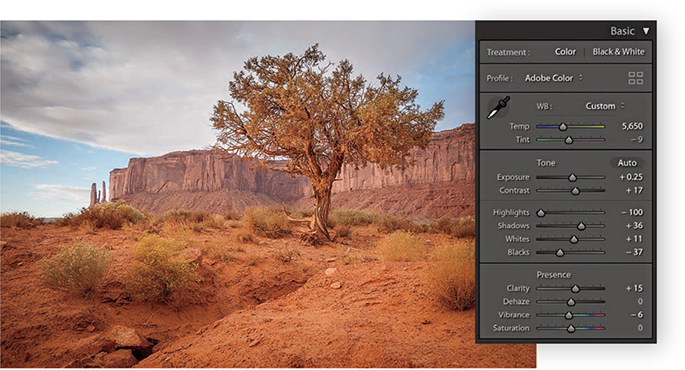

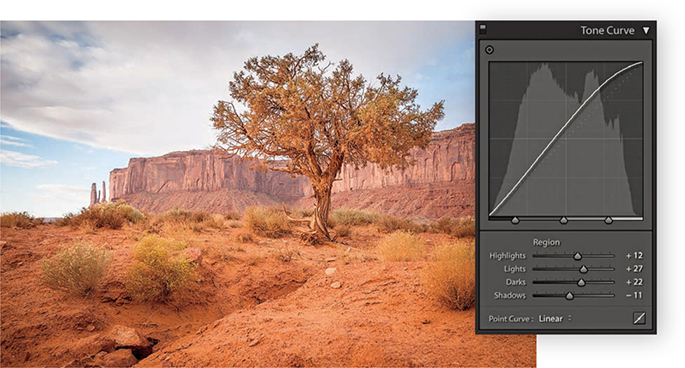

So far, I have shown how Tone Curve adjustments can be applied in isolation. But you would more typically work using a combination of both Basic and Tone Curve adjustments. Over the next few pages, I have shown a step-by-step example in which the Basic panel adjustments were applied first to correct the white balance and improve the overall tone contrast in the photograph. This was then followed by a Tone Curve adjustment to fine-tune the tonal balance and bring out more detail in the highlights and shadows. You can do a lot to improve the appearance of a photograph by making just a few Basic and Tone Curve adjustments. Through careful use of these adjustment controls, it is possible to edit the tones in a picture so that you will not always have to apply localized adjustments to achieve a good-looking image.

1. Here is a raw image in which the default Lightroom Develop settings had been applied. I first corrected the As Shot white balance by selecting the White Balance tool and rolling the pointer over an area that I wanted to make neutral.

2. I clicked with the White Balance tool to achieve a slightly cooler color with less of a magenta tint, and then I proceeded to add more Exposure and Contrast.

3. To bring out more detail in the clouds, I adjusted the Highlights slider to –100.

4. I then adjusted the Shadows slider to lighten the shadow detail, applying a +36 adjustment.

5. These next adjustments were all about fine-tuning the Basic panel settings. I used the Whites slider to set the white clipping and the Blacks slider to set the black clipping. I also adjusted the Clarity and Vibrance.

6. Finally, I went to the Tone Curve panel and adjusted the parametric sliders to further improve the tone contrast.

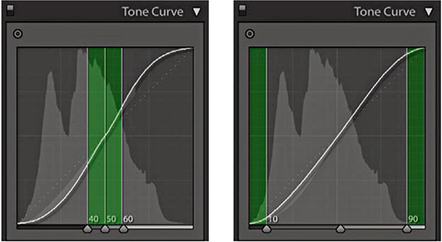

Tone range split point adjustments

The tone range split points are at the bottom of the Tone Curve panel. In Figure 4.68, The Tone Curve panel on the left shows an S-shaped tone curve with the tone range split points in their normal positions with equal spacing for the Shadows, Darks, Lights, and Highlights zones. The middle example shows the Shadows zone set to its widest extent, compressing the other three zones. The example on the right shows the Highlights zone set to the widest point. Figure 4.69 shows how moving the two outer tone range split points in closer increases the midtone contrast, while moving them farther apart reduces the midtone contrast.

Double-click the tone range split points to reset to their default settings.

Refining the tone curve contrast

The following example shows how the Tone Curve Zones can be adjusted to fine-tune the tone curve contrast. I find it also helps sometimes to drag the Shadows zone slider to the extreme left position and the Highlights zone slider to the extreme right to concentrate a contrast boost to add a contrast kick to the shadows and highlights and leave the midtone contrast relatively flat.

1. Here, a contrast-increasing tone curve was applied to the image. The tone range split points were in their default positions and, as you can see, the Tone Curve Zones were evenly divided.

2. In this step, I moved the middle and outer right sliders to the right. This compressed the width of the Lights zone and thereby increased the contrast in the Lights zone area. This revealed more tone detail in the face.

HSL/Color Panel

When editing color images, the HSL/Color panel is an all-in-one panel for making fine-tuned color adjustments. The HSL component (Figure 4.70) is kind of equivalent to the Hue/Saturation dialog found in Photoshop, except in Lightroom you can apply these types of adjustments to raw photos as well as rendered pixel images, such as JPEGs and TIFFs. It is a color adjustment tool to use when you need to target specific colors. The HSL panel has three color adjustment sections that allow you to control the Hue, Saturation, and Luminance over eight color-band ranges. These provide a more practical range of color hues to work with and more usefully match the colors people most often want to adjust. The Color section of this panel (Figure 4.71) provides a more simplified version of the HSL controls, with button selectors at the top for choosing the desired color band to edit, with Hue, Saturation, and Luminance sliders below. If an image has been converted to black and white, however, you will see instead the B&W panel shown in Figure 4.72. This can be used to carry out black-and-white conversions (which I discuss in the following chapter).

The sliders in the Hue section control the hue color balance, and these can be used to make hue color shifts in each of the eight color-band ranges. For example, dragging the Green Hue slider to the right makes the greens more cyan, while dragging to the left makes them more yellow. The sliders in the Saturation section control the color saturation. Dragging a slider to the right increases the saturation, while dragging to the left decreases the saturation. By dragging all the Saturation sliders to the left, you can convert the whole image to black and white. The Saturation slider controls apply a nonlinear saturation-type adjustment (similar to what the Vibrance slider does). This means that as you increase the saturation, lower saturated pixel values are increased relative to the already higher saturated pixel values in an image. The sliders in the Luminance section can be used to darken or lighten colors in the selected color ranges, and in a way that manages to preserve the hue and saturation. If you click the All button, the panel expands to let you see all the sliders at once. Also, clicking the Hue, Saturation, or Luminance tabs toggles showing just the controls for those parameters or showing All sliders.

As with the Tone Curve panel, the HSL controls can be applied using a Target Adjustment mode. Select the Hue, Saturation, or Luminance tab and click the Target Adjustment tool button to activate it. You can then click an image and drag up or down to adjust the colors targeted by the pointer. You can use the following shortcuts to enable the various HSL Target Adjustment modes: Hue,  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC); Saturation,

(PC); Saturation,  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC); and Luminance,

(PC); and Luminance,  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC). You can turn off the Target Adjustment tool by clicking the Target Adjustment button again, pressing

(PC). You can turn off the Target Adjustment tool by clicking the Target Adjustment button again, pressing  , or using the

, or using the  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) shortcut. The Target Adjustment tool is deactivated whenever you switch to working in a new panel.

(PC) shortcut. The Target Adjustment tool is deactivated whenever you switch to working in a new panel.

1. To better handle skin tones, you might consider using the Adobe Portrait profile, or create a custom camera calibration profile (see page 187). But if you shoot a mixture of subjects with the same camera profile, you can also use the HSL panel Hue section to compensate for reddish skin tone colors.

2. In this example, I went to the Hue section and activated the Target Adjustment tool. I then clicked on a skin tone area in the picture and dragged upward to make the skin tones less red and more yellow.

Selective color darkening

At first glance, the HSL controls in Lightroom appear to work the same as those used in Photoshop’s Hue/Saturation dialog, but if you experiment a little further, you will notice some distinct differences. For example, the Lightroom Hue slider adjustments are somewhat tamer than their Photoshop cousins. The Saturation sliders respond more or less the same as they do in Photoshop, but the most marked differences are revealed when working with the Luminance controls. You may have noticed that when you adjust the Lightness slider in the Photoshop Hue/Saturation dialog, the adjusted colors tend to lose their saturation. To selectively darken a color in Photoshop, you generally have to search for a particular combination of Saturation and Lightness to achieve the desired result. However, the Lightroom sliders really do respond the way you would expect them to and provide you with complete control over the luminance of any color range, as shown in the following steps.

1. The challenge here was to simulate the effect of a polarizing lens filter and darken the blue sky without affecting the tonal balance of the other colors.

2. To darken the blue sky colors in Lightroom, I enabled the Target Adjustment mode in the Luminance section of the HSL panel, clicked an area of blue sky, and dragged downward. As you can see, this mainly reduced the Blue slider luminance and successfully added more contrast between the sky and the hotel.

When darkening a blue sky, as in the example shown here, you sometimes end up seeing banding or mottling in the blue sky areas. One solution is to go to the Detail panel and increase the Color and Smoothness settings in the Noise Reduction section.

False color hue adjustments

There is still some room to go crazy and do things like turn blue skies purple, but the Hue adjustments in Lightroom are definitely more constrained. To create more extreme hue shifts, you may want to shift more than one Hue slider at a time. For example, you could create a series of Develop settings in which all the Hue sliders are shifted by equal amounts. To give you an example, I created a series of hue-shifted Develop preset settings. In one setting, all the Hue sliders are shifted +30; in another, they are shifted to +60; and so on. I suggest this as one way to create creative hue-shift coloring effects (Figure 4.73).

Using the HSL controls to reduce gamut clipping

The camera you are shooting with is almost certainly capable of capturing a greater range of colors than can be shown on your computer display or in print. But just because you cannot see these colors does not mean they are not there.

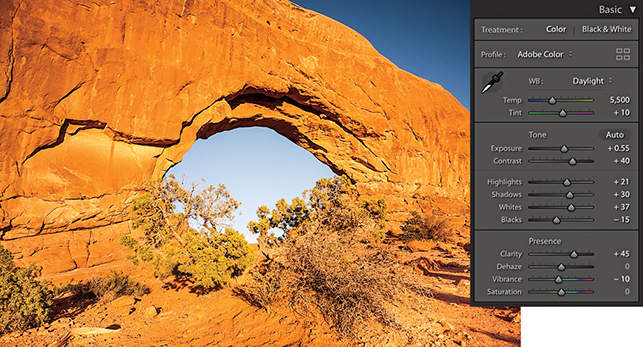

The following steps show a photograph taken of a rock formation in Arches National Park in Utah. This was shot at sunset when the rocks appeared at their reddest. At first glance, there did not appear to be much detail in the rocks, but this was only because the computer display was unable to show all the color information that was actually contained in the image. By using the HSL panel Luminance controls to darken the red and orange colors, I was able to bring these colors more into the gamut of the computer display so that they no longer appear clipped.

If you are using a standard LCD display, there is a good chance the more saturated colors will appear clipped, which can make it hard to predict how some colors will appear in print if you can’t actually see them. If the display you are using has a wide color gamut, it should be a better indicator as to which colors will and will not print. This is especially true when using soft proofing to visualize what the final print should look like (see Chapter 8). The display I work with has a gamut that matches 98% of the Adobe RGB color space, and this certainly helps when making evaluative adjustments such as in the example shown here. Even so, I find with certain color images I need to constrain the color saturation and luminance to achieve more printable result.

1. Shot late in the day as the sun was setting, this photograph captured a lovely warm glow on the red rocks. Shown here are the Basic panel settings I used.

2. From the HSL panel, I selected the Luminance tab and adjusted the Red and Orange sliders to darken the luminance of the red rocks.

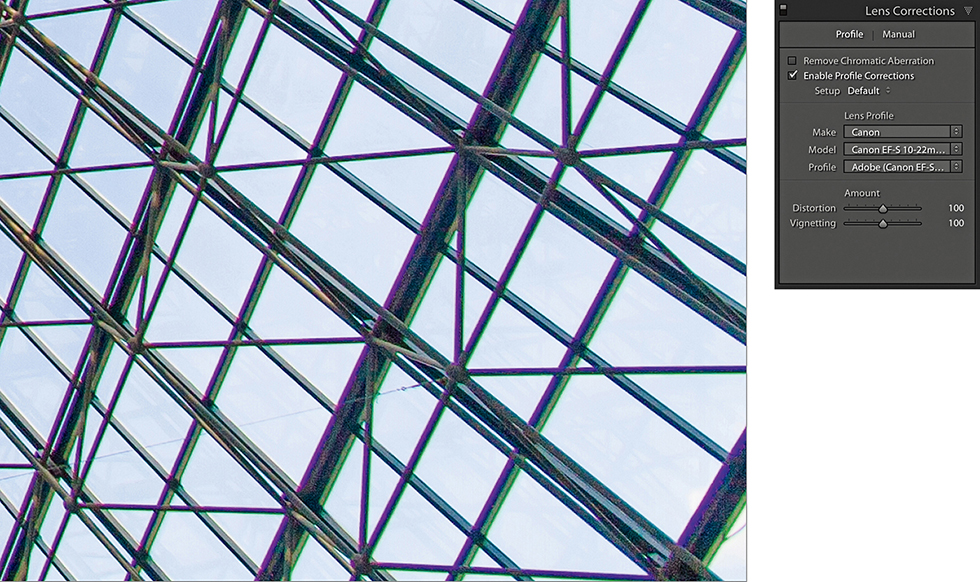

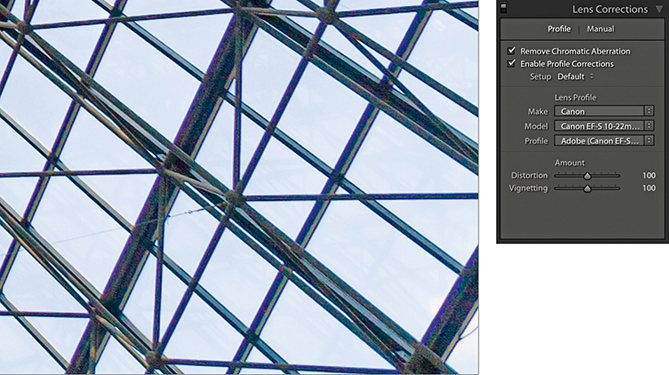

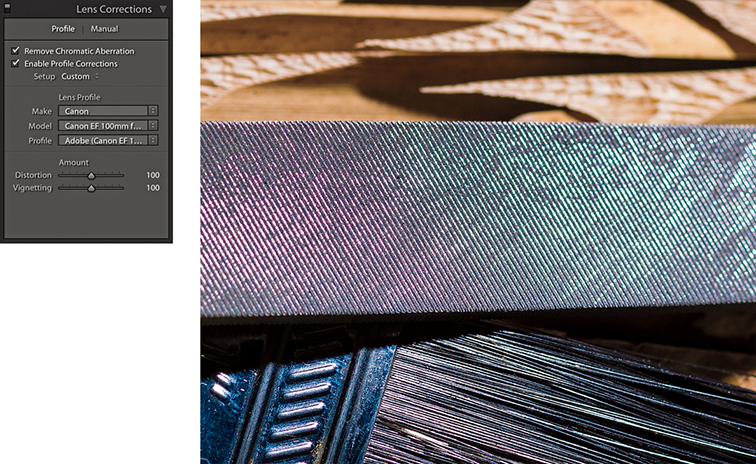

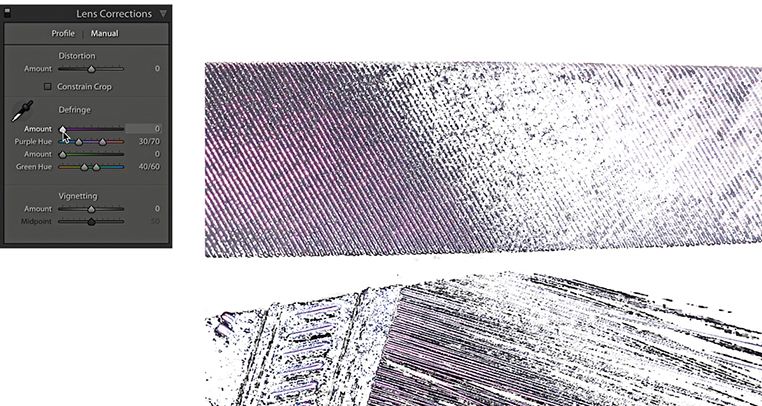

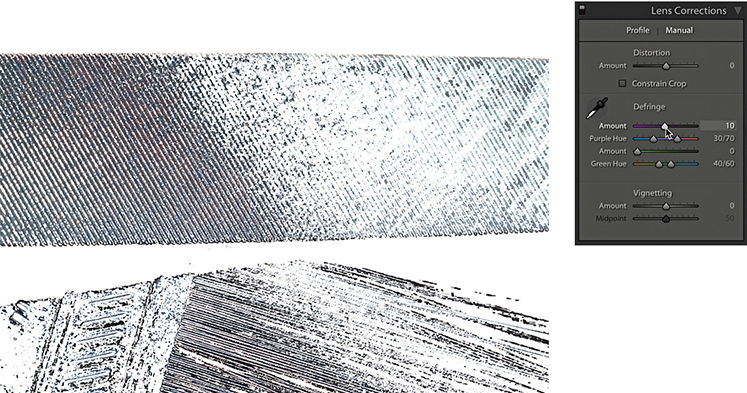

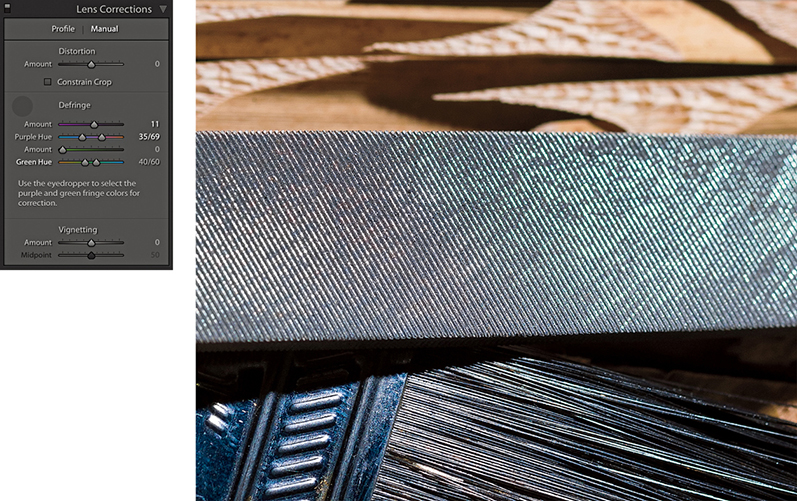

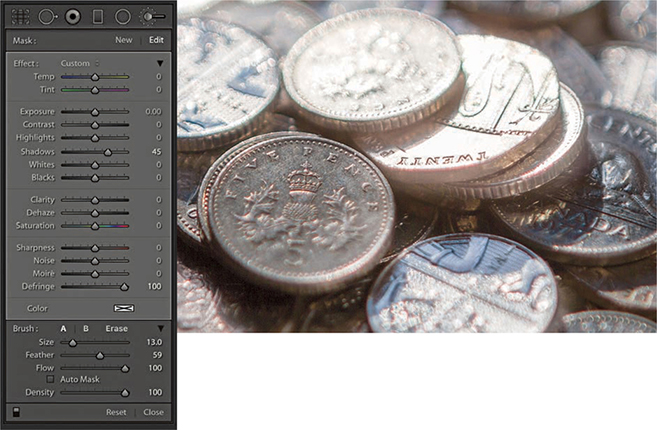

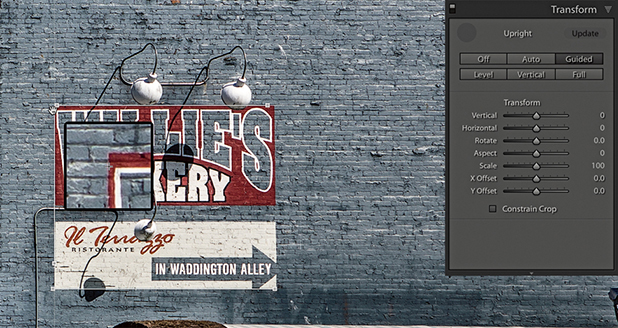

Lens Corrections Panel Profile Mode

The Lens Corrections panel can be used to cure various kinds of lens problems and has two sections: Profile and Manual (Figure 4.74). I will start by looking at the Profile controls.

Lens profile corrections

Checking the Enable Profile Corrections box applies an auto lens profile correction adjustment. This can be done for any image, providing it contains the lens information in the EXIF data and there is a matching lens profile in the Lightroom lens profile database. Also, some lens corrections profiles now also take into account when a teleconverter is combined with a lens. Images that are missing their EXIF metadata cannot be processed using the Enable Profile Corrections feature. However, by saving Lens Profile Corrections settings as Develop presets, it is possible to apply such adjustments where the EXIF metadata is missing.

Assuming Lightroom offers lens profiles for the lenses you are shooting with, it is a simple matter of clicking the Enable Profile Corrections box to apply an auto lens correction to any selected photo. When you do this, you should see in the boxes below the make of the lens manufacturer, the specific lens model, and the lens profile (which will most likely be the installed Adobe profile). If these appear empty, then you may need to first select the lens manufacturer from the Make menu, the lens model from the Model menu, and the preferred lens profile from the Profile menu. It is important to appreciate that some camera systems capture a full-frame image (therefore making full use of the usable lens coverage area for many lenses), whereas compact cameras tend to have smaller sensors that capture the image using a smaller portion of the lens’s total coverage area. The Adobe lens profiles have mostly been built using cameras that have full-frame sensors. This means that from a single lens profile, it is possible to automatically calculate the appropriate lens correction adjustments to make for all other types of cameras where the sensor size is smaller. Lightroom and Camera Raw should preferably use lens profiles generated from raw capture files. This is because the vignette estimation and removal has to be measured directly from the raw linear sensor data rather than from a gamma-corrected JPEG or TIFF image.

Lens profile corrections consist of two components: a Distortion correction to correct for the barrel or pincushion geometric distortion, along with a Vignetting correction. The Amount sliders allow you to fine-tune a profiled lens correction. So, for example, if you wanted to allow an automatic lens correction to automatically correct for the lens vignetting, but not correct for, say, a fisheye lens distortion, you could set the Distortion slider to 0 (dragging it all the way to the left). On the other hand, if you believe an auto lens correction to be too strong or not strong enough, you can easily apply a compensation to the correction amount by dragging either of these sliders left or right.