3 The Library module

Introducing Lightroom catalogs and the Library module features

Photograph: The British Museum, London, © 2014 Martin Evening

Sony DSC RX100 | 10.4mm | 200 ISO | f/5.6 @ 1/250th

In this chapter, we are going to take a first look at how the Lightroom catalog works and how to use the Library module controls to navigate and manage your photos.

The Lightroom catalog is a key component of the program. Lightroom’s underlying architecture and central database are designed to provide speed and flexibility when managing and viewing your photos. This can be seen by the way Lightroom allows you to view and update your files more quickly, provides a well-thought-out interface for managing your images, and ties in smoothly with the Book, Slideshow, Print, and Web modules.

To begin with, we will look at what is inside the Lightroom catalog folder and how to keep your catalog data backed up and protected.

About Lightroom Catalogs

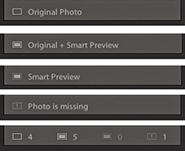

To understand Lightroom, you need to understand the role of the catalog and how it is central to the way files are managed. The Lightroom catalog references the files you import into Lightroom, creating links from the catalog to the original files, wherever they are stored on the computer. Previews are stored with the catalog to let you navigate the catalog contents, while Smart Previews can be used as proxies, which can make the catalog portable and independent of the original photos. A browser program like Bridge can also be used to manage image collections, but the disadvantage of this approach is Bridge displays all types of files and the photos you are looking for must be present on the system, which makes the Bridge workflow more rigidly desk-bound.

Lightroom actively encourages you to manage your photos better. As an image collection grows in size, you have to be especially careful as to how you organize everything so you know where all your files are when you want them. Suppose you were to fall ill and a co-worker needed to locate a specific image? How easy would it be for her to find it on your computer? In situations like this, what you require is a cataloging system that can manage your images and keep track of where everything is stored. The Lightroom catalog is written using the SQLite3 database format, which stores all the catalog data in a single file along with previews and Smart Previews data files that are easily transferable for cross-platform use. As you import your photos into Lightroom, the catalog keeps track of where the files are kept, as well as all the information associated with those files, such as the metadata and Develop settings. There is no known limit as to how many photos the catalog file can reference.

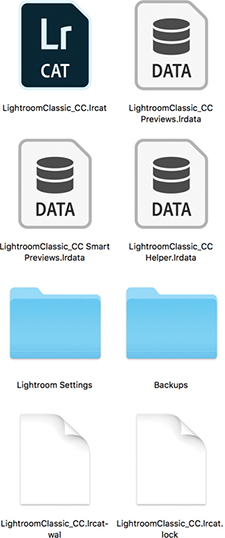

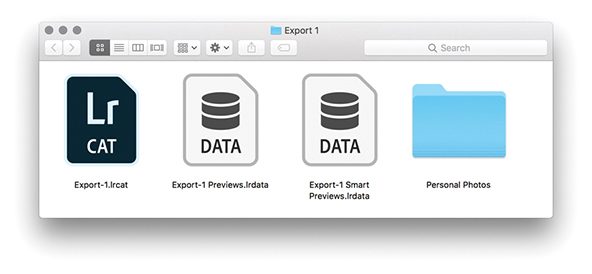

When you first installed Lightroom, a new Lightroom catalog folder was created in the username/Pictures folder (Mac) or the My Documents/My Pictures folder (PC). This folder contains a catalogname.lrcat catalog file (the master catalog file that contains all the catalog database metadata) and a catalogname Previews.lrdata file that contains the previews data (Figure 3.1). These two files store all the critical data that relates to the current Lightroom catalog. You may also see a catalogname Smart Previews.lrdata file. This will be dependent on whether you chose to build Smart Previews for any of your library images (see page 151). The catalogname.helper.lrdata database file is linked to the new folder search feature (see page 86). This file remains after the application is closed. It contains folder search data and is sort of a persistent cache for folder search optimization. The file isn’t very big in size and doesn’t require a backup. Each time you launch Lightroom, it checks to see if there is a helper.lrdata file and, if missing, creates a new one.

Tip

If you need to rename the catalog file, close down Lightroom, go to the Lightroom folder and rename the .lrcat, Previews.lrdata, Smart Previews.lrdata and helper.lrdata files. Just make sure the suffixes remain unaltered and that you change only the first part of the names (the prefix).

While Lightroom is running, a catalogname.lrcat-wal file will be present. This contains temporary internal work files that have not been written to the catalog database file yet. If Lightroom should suffer a crash, it may temporarily remain in the folder until Lightroom has been relaunched and had a chance to recover all the data. Whatever happens, do not delete this file because it may contain important data that can help Lightroom recover recently modified data information. The other temporary file is a catalogname.lock file, which is there to prevent other Lightroom users from accessing the same catalog file over a computer network. Should you suffer a computer crash while working in Lightroom and experience problems when relaunching the program, it could be because a .lock file is still present in the Lightroom catalog folder. If this is the case, try manually deleting the .lock file via the system Finder/Explorer. Lightroom should then relaunch as normal.

You may also see a Lightroom Settings folder. This shows up only if the “Store presets with catalog” option is checked in the Lightroom Presets preferences (see page 13). When checked, a Lightroom Settings folder is added inside the Lightroom catalog folder. This lets you store newly created Lightroom settings (all except profiles and Develop presets) locally within the Lightroom catalog. It may be useful if you want to keep certain catalog settings restricted to specific catalogs (such as FTP settings you might wish to keep private). The downside is if you later decide to uncheck this option, Lightroom will revert to referencing the main user Lightroom folder. As a consequence of this, some settings presets may appear to be missing because the catalog-stored Lightroom Settings folder will not be synchronized with the one stored in the user Lightroom folder.

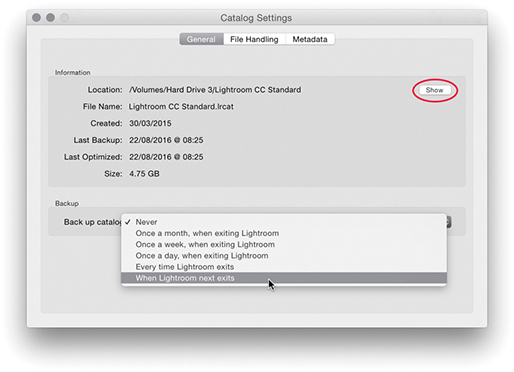

If you go to the Lightroom menu (Mac) or Edit menu (PC) and choose Catalog Settings, this opens the Catalog Settings dialog shown in Figure 3.2. Here you can click the Show button (circled) to reveal the current location of the catalog in the Finder/Explorer. The Lightroom catalog folder does not have to be in the Pictures/My Pictures folder. You can move it to any drive location you like. Having said that, you cannot store the catalog on a network attached server (NAS) drive, on optical media, or within a locked (read-only) folder.

Note

The user Lightroom folder is not the same thing as the Lightroom catalog folder. The user Lightroom folder contains various Lightroom presets and templates. It can be found in the following locations: username/Library/Application Support/Adobe/Lightroom folder (Mac) or username/App Data/Roaming/Adobe/Lightroom folder (PC). However, you will notice that Lightroom profiles and Develop presets are now stored separately in a Camera Raw folder that is shared with Camera Raw for Photoshop. These are stored in username/Library/Application Support/Adobe/Camera Raw/Settings (Mac), or username/App Data/Roaming/Adobe/Camera Raw/Settings (PC).

Backing up the Catalog File

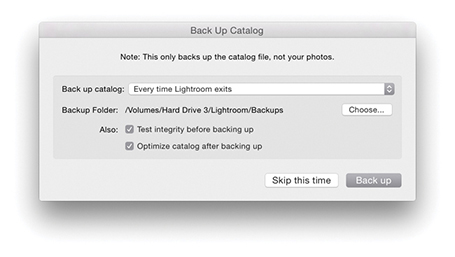

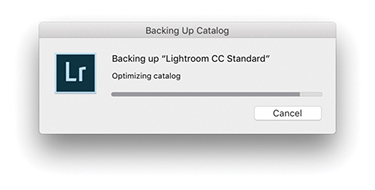

The most important component is the catalogname.lrcat catalog file, which is why you need to safeguard it as you would a financial accounts file or other important data documents and remember to carry out regular backups. They say there are only two types of computer users: those who have experienced a loss of essential data and those who are about to. In the General section of the Catalog Settings, you can choose how often Lightroom creates a backup copy of the Lightroom catalog database file. This includes options to schedule the backup procedure to take place after you have quit Lightroom. I strongly advise you to select one of these options because it provides an extra level of built-in backup security that may well prevent you from losing all your catalog data information. When Lightroom is due for a catalog backup, the Back Up Catalog dialog will appear at the designated time (Figure 3.3). This gives you the option to skip the backup for now or proceed.

Note

Your Lightroom catalog will most likely consist of tens of thousands of metadata and preview files. It can therefore take a long time for some backup software or virus-checking programs to process such a huge number of individual files, even though the files may be quite small. In fact, it’s best to exclude the Lightroom catalog and previews folder from virus checking, especially if real-time virus monitoring is enabled.

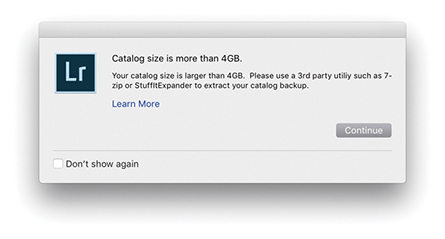

When you click the “Back up” button in the Back Up Catalog dialog, Lightroom creates a duplicate backup version of the main catalog file and saves it to the designated Backups folder, such as the one shown in Figure 3.1. Each time you back up the Lightroom catalog, Lightroom creates a new backup copy of the .lrcat catalog file and stores it in a new, dated folder within the Backups folder. If the catalog is bigger than 4 GB, you’ll see the dialog shown in Figure 3.4, which points out the backup catalog will be saved as a compressed ZIP file. If at any stage you notice there is a problem with the catalog not opening, you’ll have an opportunity to replace the current (corrupt) database with a previously backed-up copy of the catalog, placing the decompressed backup catalog in the root-level Lightroom folder. When you relaunch Lightroom, it will launch using this last backed-up version of the catalog. Over time, you may accumulate a lot of backup catalogs in the Backups folder, and it makes sense to cull the older ones as they become too out-of-date to be of any practical use.

The Back Up Catalog dialog contains an identical pop-up menu to the one in the Catalog Settings dialog that allows you to set the backup frequency. Click the Choose button to select the location where the backup catalog file should be stored. By default, the Backups folder is stored with the main Lightroom catalog folder, but you can store this folder anywhere you like on your system. After all, you might prefer the security of having the backup catalog stored on a separate drive to the master catalog. Next is an option to test the integrity of the catalog before backing up. Depending on the size of your catalog, an integrity check (Figure 3.5) should take only a few minutes to complete and can offer you peace of mind that your catalog file is in good shape.

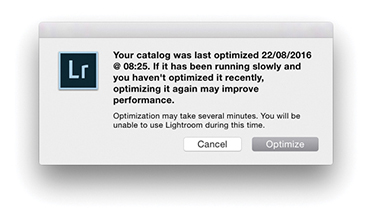

All metadata edits, such as image adjustments and keywords, are written to the catalog file. This happens on a continuous basis and can, over time, lead to data fragmentation. So, if you find Lightroom is running more slowly than expected, you may want to optimize the catalog. You can do this by selecting the “Optimize catalog after backing up” option in the Back Up Catalog dialog. You can also optimize the catalog at any time choosing File  Optimize Catalog. This displays the dialog shown in Figure 3.6, where you should click the Optimize button. It may take a few minutes to complete, but you should afterwards see an improvement in Lightroom’s performance. This process also highlights any potential problems within the catalog file and initiates a repair if necessary.

Optimize Catalog. This displays the dialog shown in Figure 3.6, where you should click the Optimize button. It may take a few minutes to complete, but you should afterwards see an improvement in Lightroom’s performance. This process also highlights any potential problems within the catalog file and initiates a repair if necessary.

Optimize Catalog, you will see the dialog shown here, which informs you of the last time the catalog was optimized and gives you the option to proceed or cancel.

Optimize Catalog, you will see the dialog shown here, which informs you of the last time the catalog was optimized and gives you the option to proceed or cancel.Backup Strategies

A mirrored RAID system can be useful in a mission-critical environment to ensure continuity of data access, but this does not amount to the same thing as having a fail-safe backup strategy. For that, you need to perform scheduled backups to a secondary set of drives, which should be stored in a safe location, such as in a fireproof safe or somewhere off-site. In a simple office setup, you could have one drive on the computer that’s used to hold the main Lightroom image catalog and a duplicate external drive of similar capacity to make regular, scheduled backups to. With this kind of setup, it is important that backups are scheduled manually. If a problem were to occur on the master disk, such as an accidental file deletion or a directory corruption, you would have the opportunity to rectify the problem by copying data over from the backup drive. And because you are keeping the data on a separate drive, it can be stored in a separate location away from the main computer. For added security, I suggest using two external backup drives and swapping over the backup disk that is connected to the computer and the one that is kept off-site. As long as the files are stored on read/write disk media, they may still be vulnerable to accidental erasure or a virus attack that could infiltrate the backup drives. To further reduce the risk, you could make DVD or Blu-ray disc copies of your image files and keep them in an appropriate storage location. It would be a pain to have to reload all the data from DVD/Blu-ray discs, but it would at least ensure that the data is free from virus attack or human error. For more about disc setups, see Chapter 12.

Backup Software

You can use various programs to carry out data backups. For macOS, I can recommend both ChronoSync from Econ Technologies (econtechnologies.com) and Carbon Copy Cloner by Mike Bombich (bombich.com). I make regular backups of all the drives on my system. Whenever I want to back up any data, I simply switch on a backup drive and run the backup process. I have the settings configured so that Carbon Copy Cloner first compares all the data on the source disk (the drive I want to back up) with the target disk (the drive I want to store the backup data on) and copies all the newly added files. Setting up the backup drives and copying all the data does take a long time the first time around, but after that, if you carry out regular backups, like once a day or each week, the backup procedure can be carried out quite quickly. If you are in the habit of leaving your computer and drives turned on overnight, you can always schedule the backups to take place in the early hours of the morning.

Time Machine and the Lightroom Catalog

A key feature of macOS, Time Machine, creates automatic backups of your data while you work and allows you to retrieve any lost or overwritten data. To prevent Time Machine from corrupting the Lightroom catalog, Lightroom marks an open catalog file as “being in use” and excluded from a Time Machine backup whenever Lightroom is running. This prevents Time Machine from backing up the catalog while it may be in an incomplete state or in the process of being modified. When Lightroom quits, it takes the catalog off the exclusion list. This means Time Machine can still create backups of the Lightroom catalog, but only while Lightroom is not in use. If you want to restore the Lightroom catalog from a Time Machine backup, you must make sure that Lightroom is not running before allowing Time Machine to run.

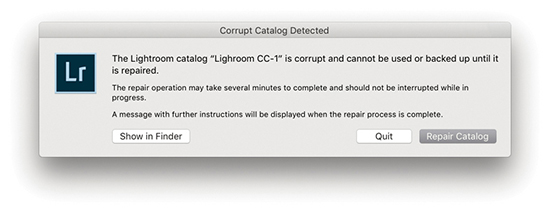

Catalog Corruption

Catalog corruption is rare, but distressing nonetheless should it happen to you. It can occur for a number of reasons, such as the computer shutting down suddenly during a power outage or drives being improperly disconnected. To avoid the nasty effects of a power loss affecting the stability of your computer system, you should consider getting an uninterruptible power supply unit. The main computer and display in my office are both connected to the main electricity via an APC ES 700 UPS backup unit. This is capable of providing enough power protection to keep the computer and display running for many minutes after a power cut.

Here’s what to do to avoid the worst consequences. First, remember to make regular backups of the Lightroom catalog and to be on the safe side, choose a different drive to save the backup catalog to. The latest solid-state drives offer faster read/write speeds, but when they fail, they fail completely. So you need to anticipate what you would do if you were to lose all the data on the disk. This need not be a problem if you are in the habit of making scheduled backups of all your data to separate disks, where ideally, you keep one set of disks stored off-site (as well as backing up the catalog).

If the catalog does become corrupted, as you launch Lightroom you will see the dialog shown in Figure 3.7. It will always be worth trying to repair the affected catalog first. But if you choose to do this, it is best to quit Lightroom and make a backup copy of the catalog before repairing, just in case your attempts at a repair end up causing further damage to an already sick catalog file. If the catalog is too damaged to repair, you will be asked to choose a different catalog to launch with.

Sync Catalog Disaster Recovery

Should you have cloud syncing enabled and you happen to lose your main Sync catalog, it is possible to download the cloud sync data back to your computer, rather than have to delete all data from the cloud and re-upload all over again. To do this, create a new catalog and then start syncing the Lightroom mobile data to the new empty catalog. From there you will have to carry out a careful catalog merge to sync the recovered data with your most recent catalog (see page 149).

The main lesson here is to maintain backups of the catalog file, both locally as well as on separate backup hard drives. If you haven’t yet backed up your catalog, I suggest you do so now, just as I would also advise you to make scheduled backups of all your computer data.

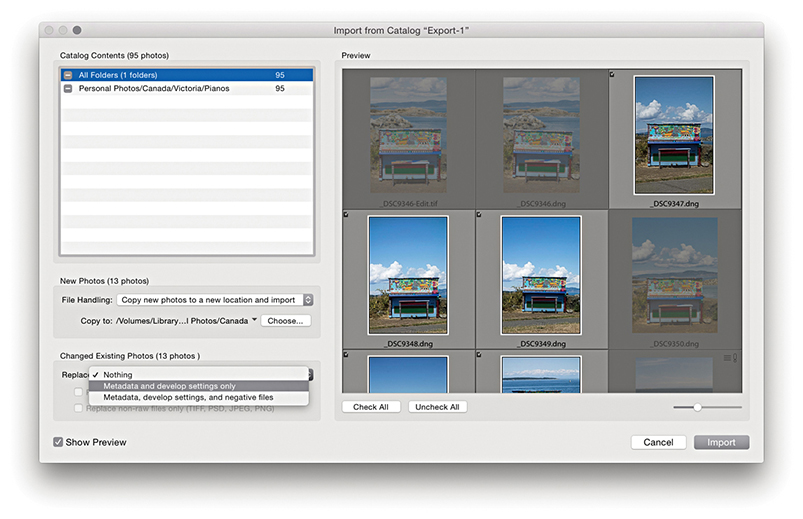

Creating and Opening Catalogs

When you first install Lightroom, it will by default create an empty new catalog. One catalog should be all you need. Personally, I find it more convenient to keep everything in one place, and it really does not bother me if personal and client photos are stored in the same place—the search functions in Lightroom make it easy to filter and search the photos I am looking for. The notion you should keep separate catalogs for different activities or shoots stems from a Bridge-style “file browser” mentality, where the cataloging power of Lightroom is perhaps not fully appreciated. It has sometimes been suggested you should consider having one catalog for personal photographs, another for studio work, another for weddings, and so on. Although this approach may seem to make sense because different catalogs can be used to segregate your photos into neat groups, it is much simpler (and easier) to segregate your images when everything is contained in the one catalog. Also, you can sync to Lightroom CC/Lightroom mobile from only one Lightroom Classic CC catalog. However, let’s say two or more family members share the same computer. In this situation, each computer user might want to maintain a separate Lightroom catalog. It is certainly the case that a professional photographer may want to run Lightroom on more than one computer and have separate catalogs on each. In such cases, it is important to make sure there is always one master catalog that is regarded as the “primary” database. Things can get really complicated if your workflow involves maintaining separate catalogs. There should always be one catalog that is regarded as the parent catalog and all the other catalogs are subordinate to it.

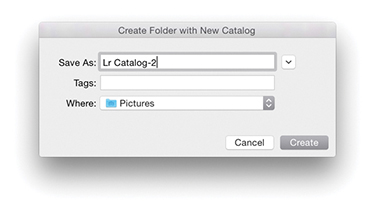

Creating a New Catalog

To create a new catalog, choose File  New Catalog. This opens the Create Folder with New Catalog dialog shown in Figure 3.8. Choose a disk location and type in the name you wish to give the catalog. This creates a new catalog folder containing an .lrcat and a Previews.lrdata file.

New Catalog. This opens the Create Folder with New Catalog dialog shown in Figure 3.8. Choose a disk location and type in the name you wish to give the catalog. This creates a new catalog folder containing an .lrcat and a Previews.lrdata file.

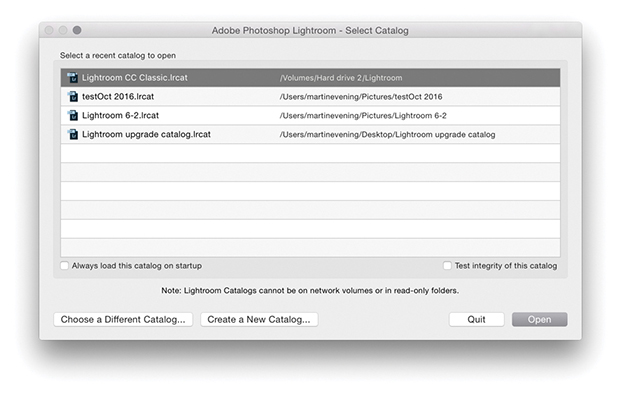

Opening an Existing Catalog

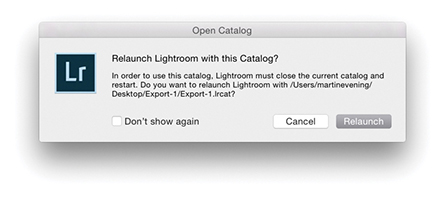

To open an existing, alternative catalog, choose File  Open Catalog. This opens the system Finder dialog where you can navigate to locate the correct Lightroom catalog folder. Here, you will need to select the catalogname.lrcat file and click the Open button to open it. You can also choose File

Open Catalog. This opens the system Finder dialog where you can navigate to locate the correct Lightroom catalog folder. Here, you will need to select the catalogname.lrcat file and click the Open button to open it. You can also choose File  Open Recent to select a recently opened catalog. Alternatively, you can double-click a catalog.lrcat file itself. Whenever you create a new catalog or load an existing catalog, Lightroom always needs a restart, because you can have only a single catalog open at a time. Or, you can hold down the

Open Recent to select a recently opened catalog. Alternatively, you can double-click a catalog.lrcat file itself. Whenever you create a new catalog or load an existing catalog, Lightroom always needs a restart, because you can have only a single catalog open at a time. Or, you can hold down the  key (Mac) or

key (Mac) or  key (PC) as you start up Lightroom. This opens the Select Catalog dialog shown in Figure 3.9.

key (PC) as you start up Lightroom. This opens the Select Catalog dialog shown in Figure 3.9.

Now let’s look at the options in this dialog. If you check “Always load this catalog on startup,” you can choose to make the selected catalog the default catalog that will open from now on each time you launch Lightroom. The “Test integrity of this catalog” option does the same thing as the option in the Back Up Catalog dialog—it lets you check to see if the catalog is in good shape before you launch it. Although it is a good thing to validate the catalog every now and then, I suspect most people would rather just get on with things and open the catalog straight away. If you don’t see the Lightroom catalog you are looking for listed, you can always click the Choose a Different Catalog button and navigate to locate the correct Lightroom catalogname.lrcat file. Or, you can click the Create a New Catalog button to create a brand-new Lightroom catalog in a new folder location. This, of course, is the same as choosing File  New Catalog.

New Catalog.

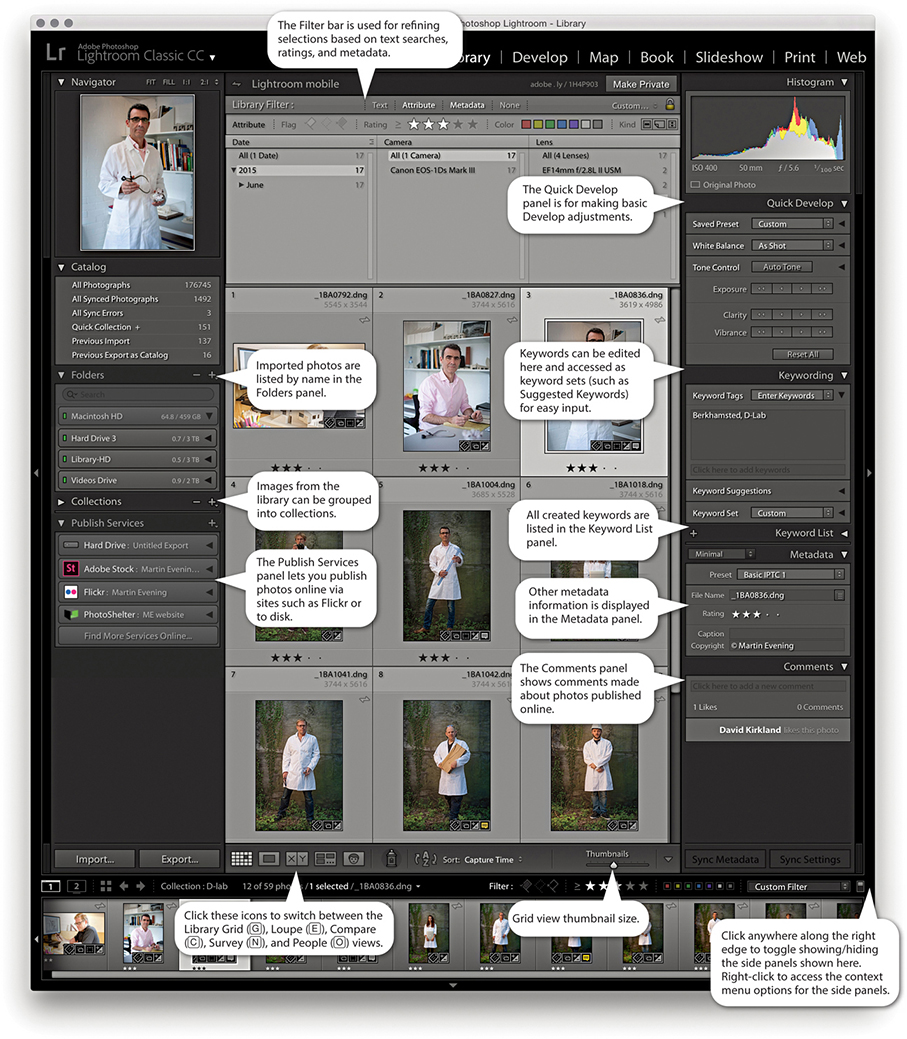

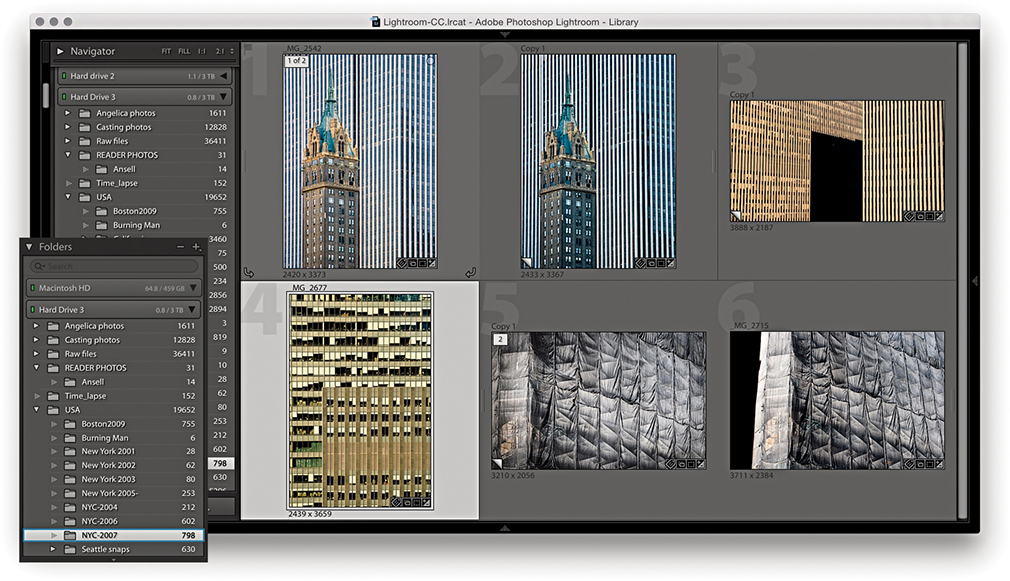

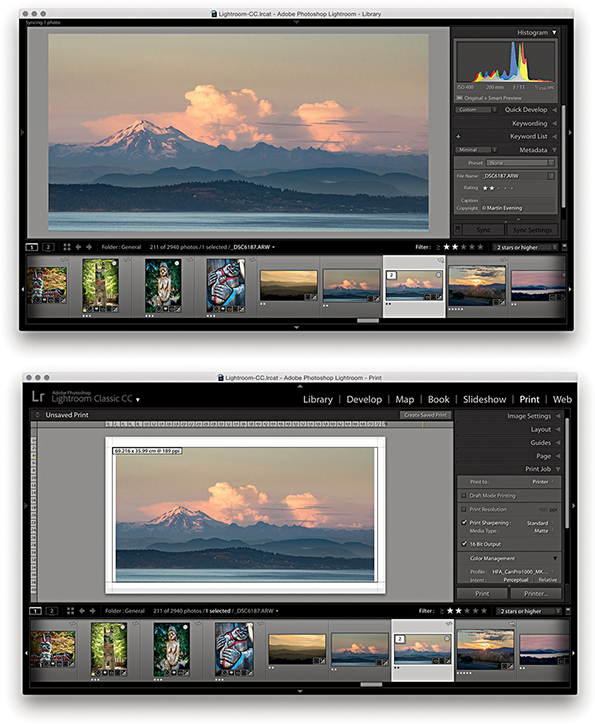

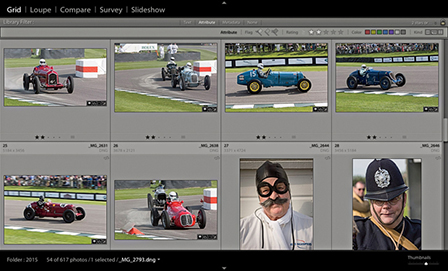

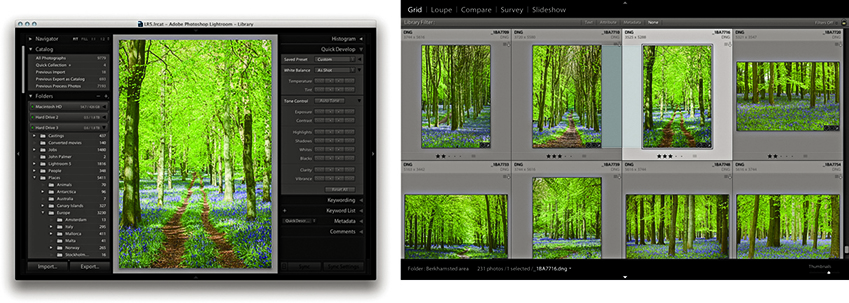

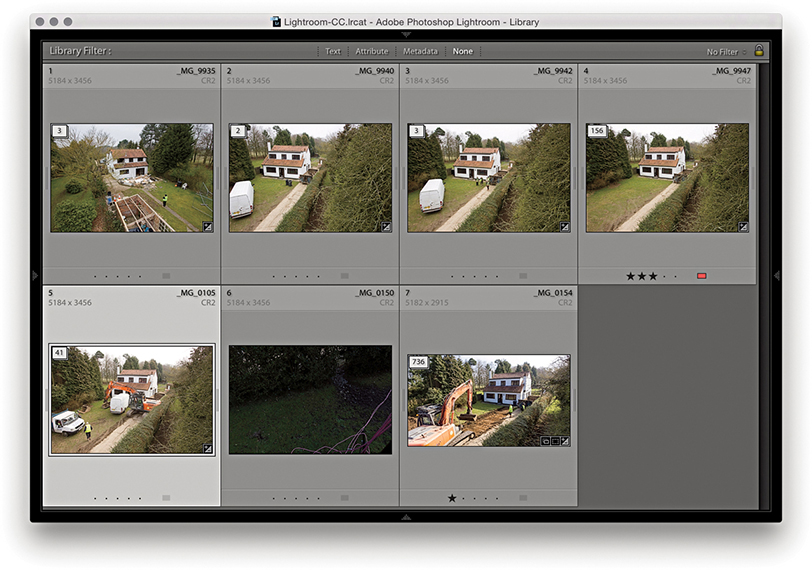

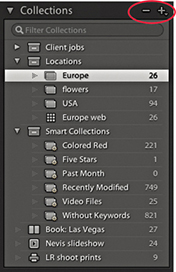

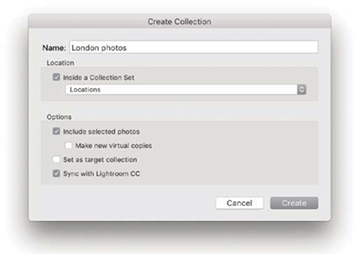

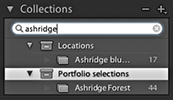

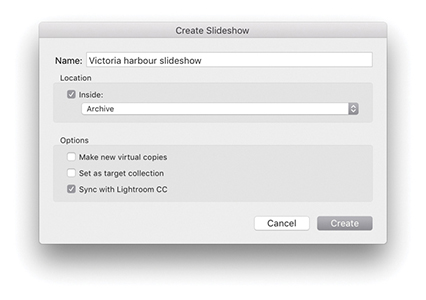

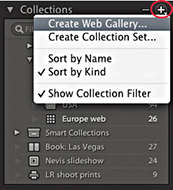

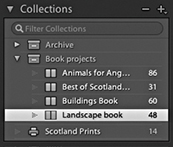

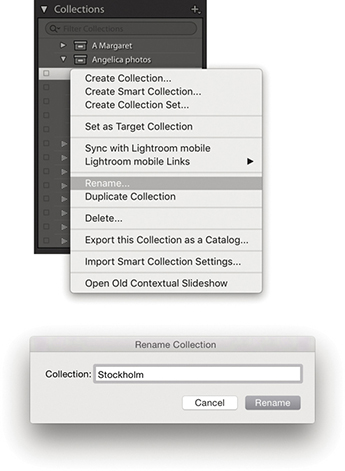

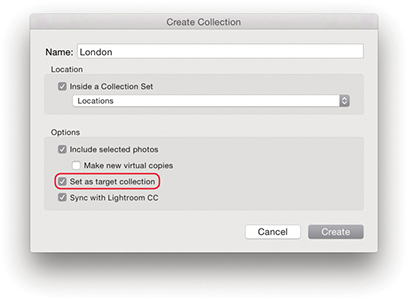

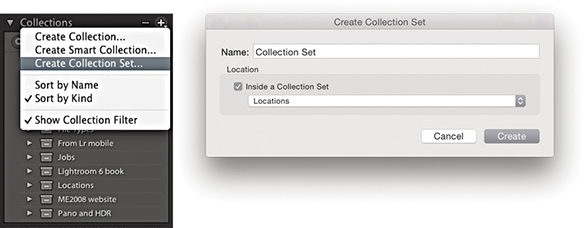

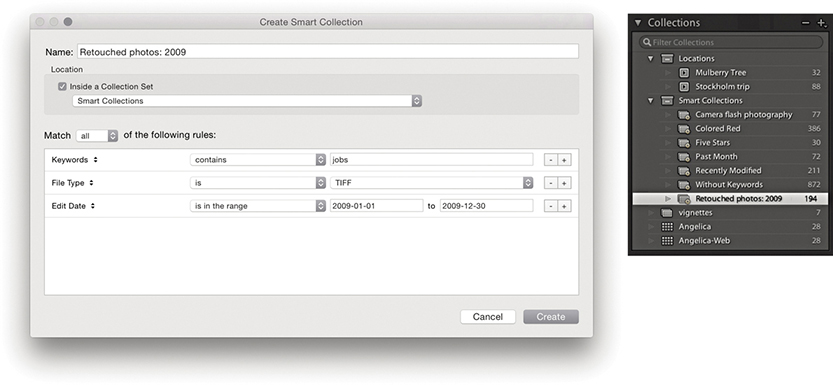

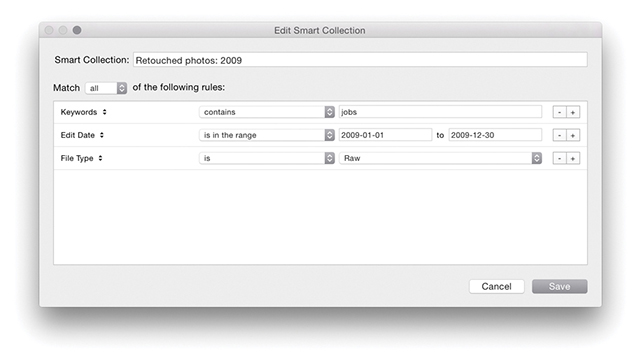

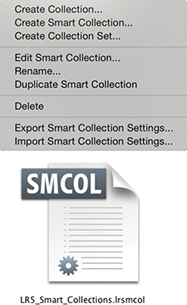

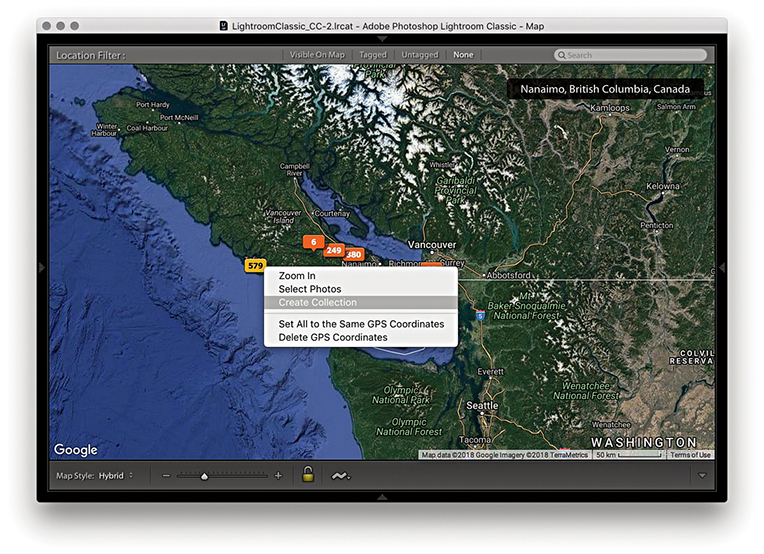

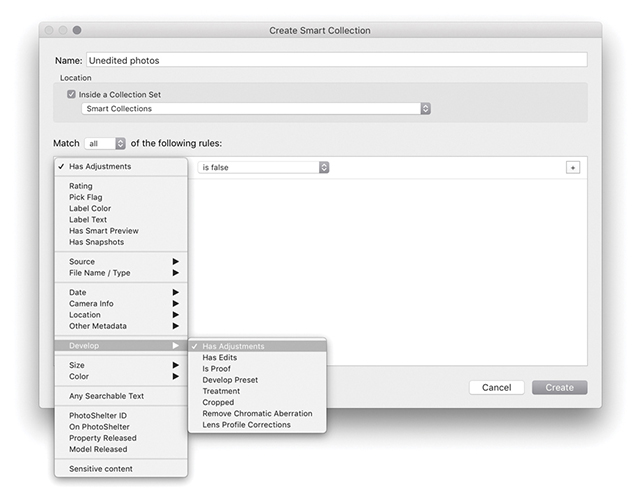

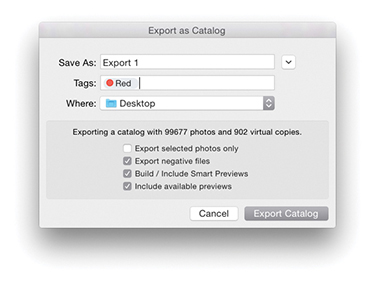

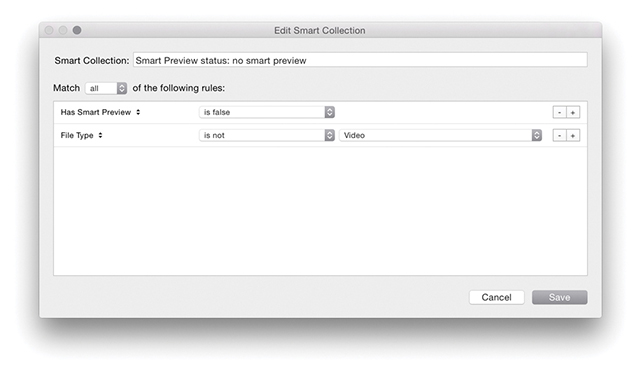

The Library Module Panels

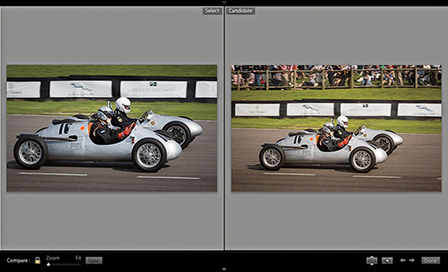

When the Library module is selected (Figure 3.10), the contents of the catalog can be displayed in a Grid view, which provides a multiple-image view using a grid cell layout; Loupe view, which shows a magnified, single-image view; Compare view, which lets you compare two photos side by side; or Survey view, where all the photos in a current selection are displayed in the content area. The Library module controls are split between the left and right panels. The Catalog panel lets you view All Photographs (the contents of the entire catalog), All Synced Photographs, a Quick Collection of images, or the Previous Import of images. Additional items may appear listed in the Catalog panel such as Missing Photos—these are temporary collections that can easily be removed via the context menu (see page 78). The Folders panel lists all the folders in the catalog by volume and alphabetical order and displays only the folders of those photos that have been explicitly imported into Lightroom. You can use the Folders panel to select specific image folders, but as you will discover in this chapter, there are also other ways you can search and locate the photos in the catalog. The Collections panel can be used to select a group of photos from the catalog and save them as a named collection. However, unlike with folders, an individual image can exist in any number of collections. Lightroom also has the ability to create Smart Collections, which are collections created automatically based on custom rule settings (see page 142). You can use the  key to add favorite images to what is known as the target collection. By default this will be the Quick Collection in the Catalog panel, but you can actually make any collection the target collection.

key to add favorite images to what is known as the target collection. By default this will be the Quick Collection in the Catalog panel, but you can actually make any collection the target collection.

Tip

You can use the  key (Mac) or

key (Mac) or  key (PC) in combination with a keypad number (1, 2, 3, etc.) to toggle showing and hiding individual panels. For example, Quick Develop = 1, Keywording = 2, Keyword List = 3, etc. You can also right-click to access the context menu options for the panels and use this to hide/reveal individual panels in any of the Lightroom modules.

key (PC) in combination with a keypad number (1, 2, 3, etc.) to toggle showing and hiding individual panels. For example, Quick Develop = 1, Keywording = 2, Keyword List = 3, etc. You can also right-click to access the context menu options for the panels and use this to hide/reveal individual panels in any of the Lightroom modules.  double-clicking in a grid cell takes you directly to the Develop module, and

double-clicking in a grid cell takes you directly to the Develop module, and  double-clicking on a photo in the Develop module takes you directly back to the Library Grid view.

double-clicking on a photo in the Develop module takes you directly back to the Library Grid view.

Using the Publish Services panel, you can publish collections of photos to sites such as Flickr. You can then use Lightroom to manage photos that have been published online and view any feedback comments via the Comments panel.

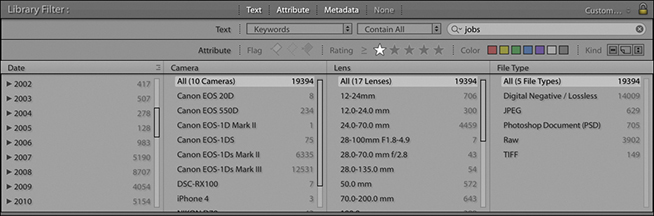

The Filter bar, located at the top of the Content area, provides a one-stop location for making refined photo selections based on text searches, ratings, and/or metadata. For example, you can filter the catalog based on a keyword search combined with a ratings filter, followed by a metadata filter based on which camera the photograph was taken with. The Quick Develop panel lets you make basic Develop adjustments without having to switch over to the Develop module. The Keywording panel is where you go to enter or edit new keyword metadata; plus, you can select keyword sets, including a Suggested Keywords set, which offers adaptable keyword suggestions based on your current photo selection. Keywords can be applied to images by dragging keywords onto selections in the content area, by dragging photos onto keywords, or by making a selection and adding keywords via the Keywording panel on the right. Other metadata information, such as the camera’s EXIF data, can be viewed via the Metadata panel, which offers several view mode options. You can also use this panel to add custom IPTC metadata, such as the title, caption, and copyright information.

Making the Interface More Compact

If you are working on a computer with a small display, you will be pleased to know that you can collapse both the Navigator and the Histogram displays. This lets you view and work more easily with the panels below. At the same time, the other panels slide beneath as you scroll down the panel list. This, too, can be helpful for those who have limited screen real estate.

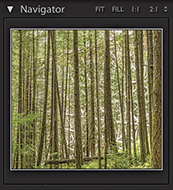

The Navigator Panel

The Navigator panel (Figure 3.11) displays a preview of the currently selected image and provides a number of controls for zooming and scrolling photos (see page 105). The Navigator panel will also update as you hover over the Folders panel or Collections panel lists. When you do this, it previews the first photo that appears in the folder, thus providing a visual reference, making it easier to locate the folder or collection of photos you are looking for.

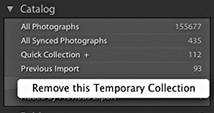

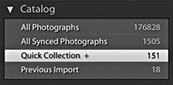

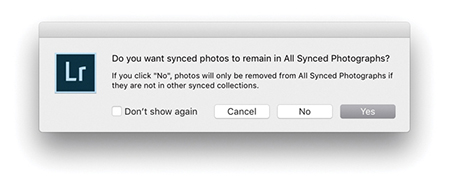

The Catalog Panel

The Catalog panel (Figure 3.12) offers several choices for displaying files. All Photographs displays all the files (showing the total number of photos in the catalog). All Synced Photographs displays files synced to Lightroom CC. Quick Collection displays all files in the current Quick Collection, and Previous Import lets you view the most recently imported files. It is important to remember to select All Photographs if you want a filter search to include everything that is in the catalog. I know this may seem obvious, but it is so easy to forget and then wonder why a search has turned up no results! As you work with Lightroom, other items will appear listed in the Catalog panel, such as Missing Photos. These are classed as temporary collections and can easily be removed. Just right-click to access the context menu and select Remove this Temporary Collection.

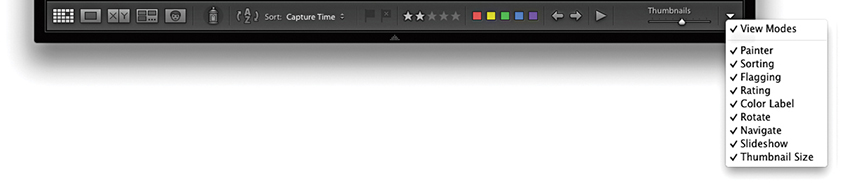

The Library Module Toolbar

The default Library module Toolbar contains the Grid, Loupe, Compare, Survey, and People view mode buttons, as well as the Painter, Sort control, and Thumbnails slider (Figure 3.13). You can customize the Toolbar by clicking the Toolbar options to add Rating, Flagging, Color Labels, Rotate, Navigate, and Slideshow playback controls. The Library module Toolbar can be customized individually for both Grid and Loupe views. For all Lightroom modules you can use the  keyboard shortcut to toggle showing/hiding the Toolbar (you can also just hold down the

keyboard shortcut to toggle showing/hiding the Toolbar (you can also just hold down the  key to temporarily access the Toolbar). Each time you do this, you will see a message reminding you to use the same shortcut to reveal the Toolbar again. Also, the items you see listed here will vary depending on whether you are in the Grid view or Loupe view mode.

key to temporarily access the Toolbar). Each time you do this, you will see a message reminding you to use the same shortcut to reveal the Toolbar again. Also, the items you see listed here will vary depending on whether you are in the Grid view or Loupe view mode.

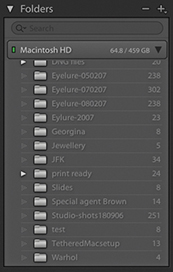

The Folders Panel

As photos are imported into Lightroom, the folder locations appear in the Folders panel, listed in alphabetical order and segregated by the different hard-drive volume headers (Figure 3.14). Each of these volume header bars can be collapsed by clicking it. The green light in the volume header indicates that a disk drive is connected and has ample free storage space. As the drive nears its full capacity, the light will turn yellow, then orange, and finally red (indicating the hard drive is full). If a disk drive is currently offline, you will notice the volume header name appears in black, and if a folder name within it appears dimmed, this means there are broken links to one or more of the images contained within that folder. The numbers displayed in the volume header bar indicate the number of free gigabytes of data that are left on that drive alongside the total gigabyte capacity. You can right-click the volume header bar to access the context menu shown in Figure 3.14, where you can change the display to show instead the photo count, the online/offline status, or none of these.

Parent Folders and Subfolders

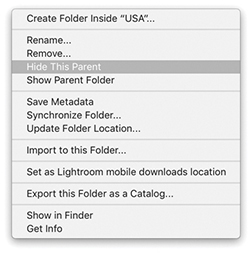

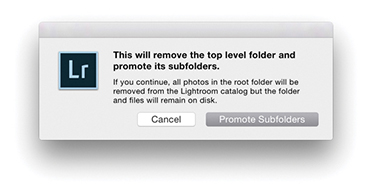

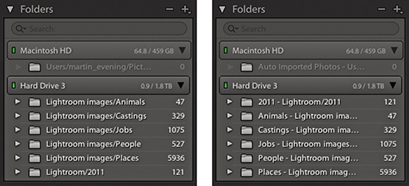

The Folders panel can be used to manage the folders that make up the Lightroom catalog—they can then be grouped into folders any way you like (as long as the individual folders are stored on the same volume). Folder names that are longer than about 30 characters will appear visibly truncated in the Folders panel, so it is best to keep names short. In some ways, the Folders panel looks like the list tree folder view you would find in a file browser program; the folder structure that is displayed in the Folders panel does, in fact, have a direct relationship with the system folders. But there is one key difference: the apparent absence of parent folders. When you first import photos, Lightroom, by default, lists the folders in as compact a hierarchy as possible. To expand the list view to show a complete hierarchy of folders, you will need to  -click the top-level folder. In Figure 3.15, I imported a folder of images called Jobs that was contained in a system parent folder called Lightroom images. But you can see that the top-level Lightroom images folder was not included here. A browser program would methodically list every folder in the folder tree hierarchy, but in Lightroom the aim is to provide the user with a tidy view of the imported folders. Keeping the folder hierarchy compact makes the Folders panel navigation easier, since you don’t always have to expand the panel’s width to view folders nested several levels deep. Should you wish to reveal the top-level folders, you can do this on a folder-by-folder basis. Right-click the top-level folder (not a subfolder) to reveal the context menu, and select Show Parent Folder. This will change the Folders panel view to include showing the parent folders (Figure 3.16). If you want to reverse this process, you can do so by again going to the context menu (Figure 3.17) and selecting the Hide This Parent option, which reverts to the Folders panel view seen in Figure 3.15. If any loose files happen to be in the parent folder, files that aren’t located in any of the subfolders, a warning dialog opens (Figure 3.18). Clicking Promote Subfolders will remove those loose files from the catalog, but not actually delete them from the computer. It is therefore best to proceed with caution here when choosing to hide parent folders.

-click the top-level folder. In Figure 3.15, I imported a folder of images called Jobs that was contained in a system parent folder called Lightroom images. But you can see that the top-level Lightroom images folder was not included here. A browser program would methodically list every folder in the folder tree hierarchy, but in Lightroom the aim is to provide the user with a tidy view of the imported folders. Keeping the folder hierarchy compact makes the Folders panel navigation easier, since you don’t always have to expand the panel’s width to view folders nested several levels deep. Should you wish to reveal the top-level folders, you can do this on a folder-by-folder basis. Right-click the top-level folder (not a subfolder) to reveal the context menu, and select Show Parent Folder. This will change the Folders panel view to include showing the parent folders (Figure 3.16). If you want to reverse this process, you can do so by again going to the context menu (Figure 3.17) and selecting the Hide This Parent option, which reverts to the Folders panel view seen in Figure 3.15. If any loose files happen to be in the parent folder, files that aren’t located in any of the subfolders, a warning dialog opens (Figure 3.18). Clicking Promote Subfolders will remove those loose files from the catalog, but not actually delete them from the computer. It is therefore best to proceed with caution here when choosing to hide parent folders.

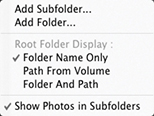

If you click the Folders panel menu button (circled in Figure 3.14), this reveals the pop-up menu options shown in Figure 3.19. Here, you will see further options for how the root folders are displayed. You can keep to the default option, Folder Name Only, or you can select the Path From Volume option to identify the folders or the Folder And Path option (both are shown in Figure 3.20). These particular folder views can be used for instances where you wish to hide the parent folders but still need to see a full folder path or partial folder path view within the folder header.

Show Photos in Subfolders

Also listed in the Folders panel menu (Figure 3.19) is the Show Photos in Subfolders option. This is always on by default and allows you to see everything that’s contained in each folder, including all subfolders. When this option is disabled, you get to see only the files selected in each root-level folder (you can also switch this option on or off via the Library module Library menu). If the folder you select contains no images and just subfolders of images, you’ll see a “No photos selected” message in the content area. Lightroom explains this more clearly by saying “No photos in selected folder, subfolders not shown.”

Incidentally, when Show Photos in Subfolders is selected, you won’t be able to apply a custom sort order or stack photos across multiple folders. You can apply a custom sort order only when viewing a folder that contains no subfolders.

As you will have gathered by now, Lightroom gives you a lot of options, and this is a good example of where, if your workflow requires special attention to the identification of folders, Lightroom lets you do so. I think most people will be happy to stick with the default setup, although understanding how to manage the Show Parent Folder/Promote Subfolders commands is certainly important and useful to know.

Locating a Folder at the System Level

Here is an example of how you can locate the system folder via the computer’s Finder/Explorer.

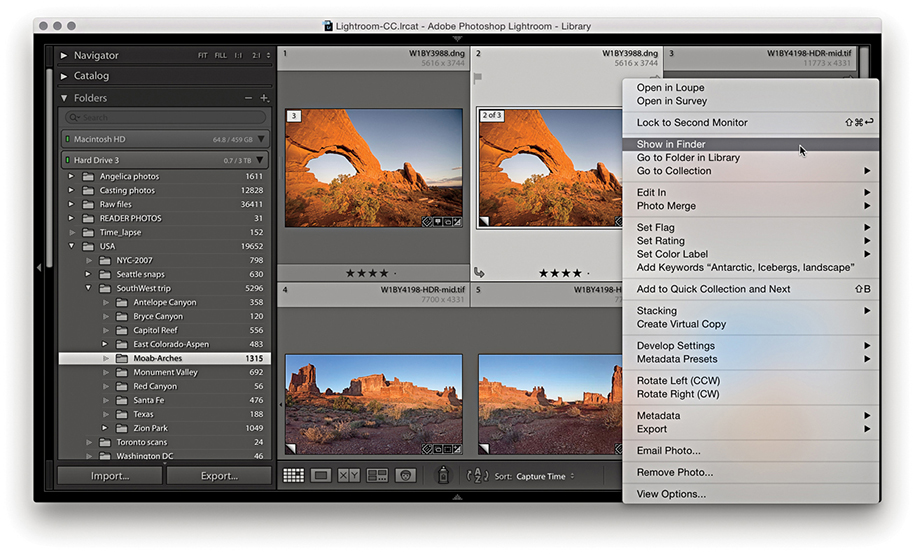

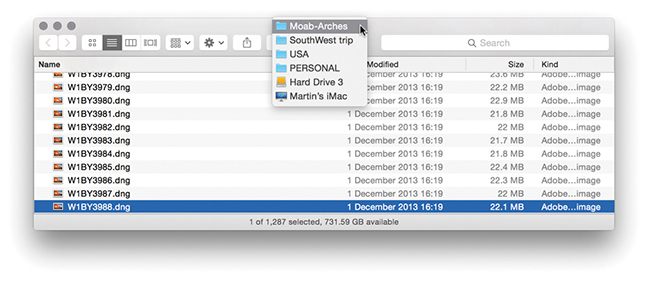

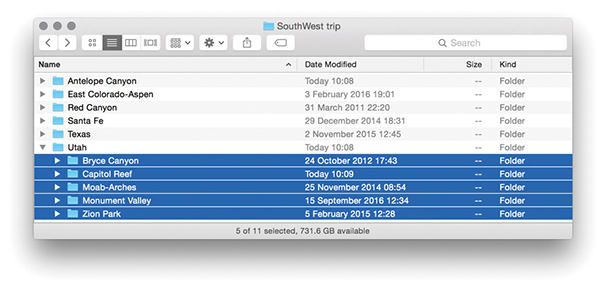

1. Here is a view of the Folders panel in Lightroom and the associated system folder. To reveal the system folder from within Lightroom, I selected a photo that resided in the Moab-Arches folder, right-clicked to reveal the context menu, and chose Show in Finder (Show in Explorer on a PC).

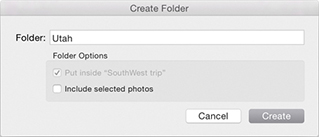

2. In Lightroom, I created a new folder called Utah, as a child of the USA/SouthWest trip folder. I then moved the Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, Moab-Arches, Monument Valley, and Zion Park folders inside the new Utah folder. As you can see, this placed the five folders inside the new Utah subfolder. This folder move step was also mirrored at the system level.

The Folders Panel/System Folders Relationship

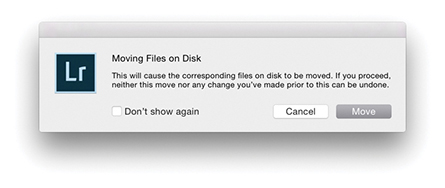

As was shown in the preceding steps, any changes you make to the folder structure within Lightroom, such as moving or renaming a folder, is reflected at the system level and the system folders will correspond with the folders listed in the Lightroom Folders panel. In addition to rearranging the hierarchy of folders, you can freely move files from one folder to another by selecting the files you want to move and dragging them across. This will prompt the dialog shown in Figure 3.21, which gives you a further warning if there is not enough room on the destination drive. You’ll sometimes find it helps after you initiate a move if you then deselect the folder view in Lightroom, as this frees Lightroom from displaying an update of the previews in the content area. There is also a potential issue of what might happen if there were to be a computer crash while moving files. Lightroom effectively copies and deletes files during a move process, and there is the risk you may lose some data. An alternative option is to copy the files at the system level and then relink using the Synchronize Folder command described on page 88.

Maintaining Folder Links

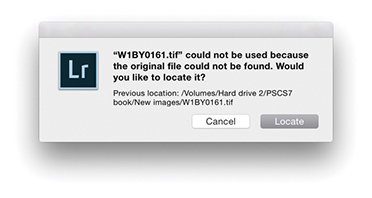

If you happen to move folders containing Lightroom catalog-referenced files at the system level or rename them, then things start to get a little more complicated. If a folder is moved or the folder name is changed at the system level, the Lightroom Folders panel alerts you by showing a question mark over the relevant folder icon (see Figure 3.22). If the folder link is broken, then all the imported files within that folder will have broken links, too. The easiest way to restore a folder link is to right-click that particular folder to access the context menu, select Find Missing Folder, and navigate to find the correct folder (wherever it has now been moved to or however it has been renamed).

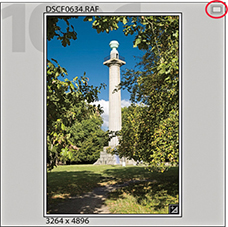

If the folder link is okay and it is only the files within that folder that have broken links, Lightroom displays an exclamation point icon in the grid cell (Figure 3.23). To restore a broken file link, click the exclamation point icon to open the missing link dialog shown in Figure 3.24. You can then click the Locate button to relocate the original source photo on the computer. Once this has been done for one photo, all the other missing files in that folder should automatically update as well.

This also raises an important point about the risks of working with both Lightroom Classic CC and Lightroom CC/Lightroom mobile. Adobe doesn’t officially support or recommend using both side by side, and there are good reasons for this. They want photographers to either adopt a desktop-centric workflow (Lightroom Classic CC), or a server-based workflow (Lightroom CC). If you sync from Lightroom Classic CC to Lightroom CC, there is always the risk of things going wrong if the master files that are primarily stored on the desktop are synced from Classic to Lightroom CC/Lightroom mobile. It is possible to move files around in Lightroom Classic CC, rename them, or rename folders and they’ll keep in sync. But if the master files get deleted, they won’t be backed up in the cloud, which could cause all kinds of tech support problems for Adobe.

As long as you are aware of this and can take personal responsibility for making sure proper backup procedures are in place, I don’t see why this should prevent you adopting a workflow in which Lightroom Classic CC and Lightroom CC/Lightroom mobile work together. I personally find it immensely useful that when I take photos using my smartphone, these are added to Lightroom CC for iOS, automatically backed up to the cloud and appear downloaded to the computer running Lightroom Classic CC. Furthermore, I can sync collections to Lightroom CC/Lightroom mobile as synced albums that can also be made publicly accessible for easy web sharing with friends or clients. Because of this feature, it has been well over a year since I last used the Web module in Lightroom Classic CC.

Maintaining Volume Links

If the entire volume is missing, either because you renamed it or because the drive is not switched on, the volume header will appear dimmed and you will see question marks over the folders (Figure 3.25). Once the drive has been correctly named or you have switched the drive back on, the volume header will indicate that the drive is live again, and the folder links should be restored.

Managing Folders and Collections

Let’s now look at the ways you can manage folders and collections.

Folders Panel Search Field

A folder-specific search field has been added to the top of the Folders panel, where you will find that folder searches are pretty much instantaneous and the search feature feels robust. In the Figure 3.26 example, I carried out a search for California. This short-listed a parent folder named California and the subfolders within it. Folder searching also includes support for non-English unicode characters.

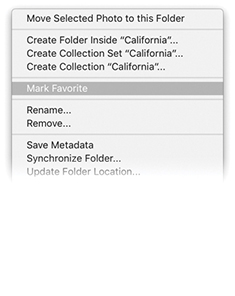

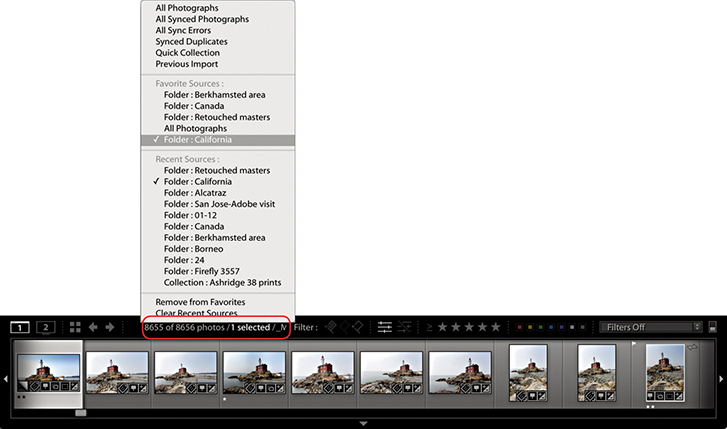

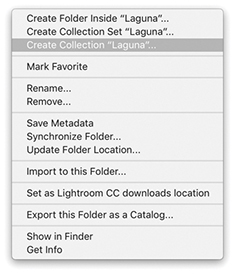

Marking Folders as Favorites

To designate a folder as a favorite, right-click the folder to access the context menu, then choose Mark Favorite (Figure 3.27). Folders marked as favorites will also appear listed in the Favorite Sources section of the Filmstrip Sources menu (Figure 3.28).

If you go to the Folders panel filter (Figure 3.29), you can select Favorite Folders to filter the folders you have marked as favorites, which are marked with a star in the bottom right corner.

Adding Color Labels to Folders

You can apply color labels to folders and filter the color-labeled folders just as you can filter favorite folders via the Folders panel Filter bar.

To apply a color label to a folder, right-click on a folder name in the Folders panel. Navigate to Add Color Label in the context menu and select a color from the submenu (Figure 3.30). To remove a color label, select None. To filter by colored folders, click on the magnifying glass in the Folders panel Filter bar and select Labeled Folders (Figure 3.31).

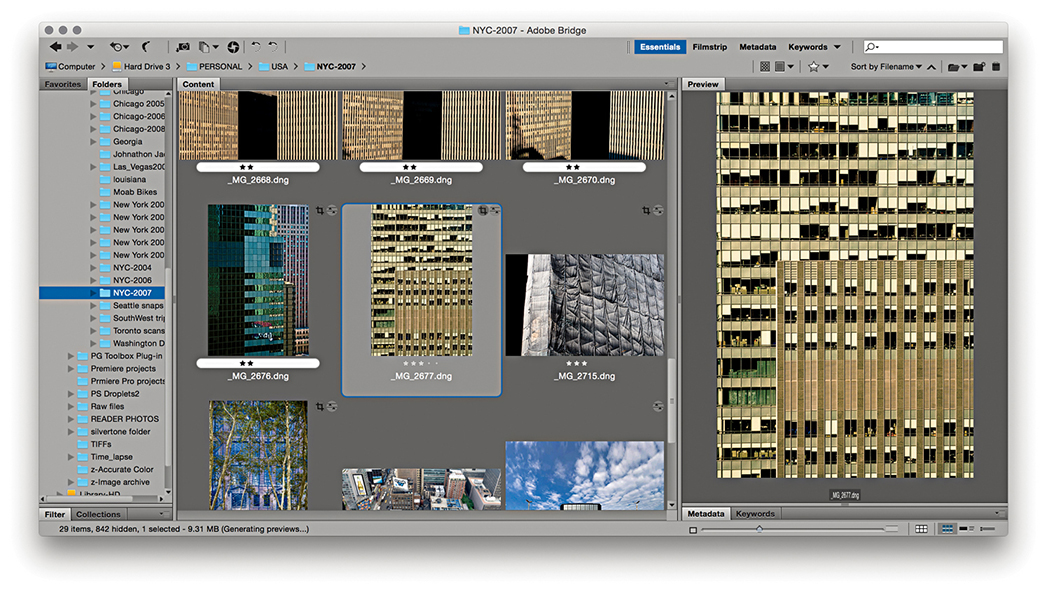

Synchronizing Folders

Unfortunately, Lightroom cannot automatically detect if new images have been added to a folder at the system level. For example, let’s say you import a folder at the start of a project and as you switch between working Lightroom and Bridge (or the Finder/Explorer), some files may get deleted or new files get added. This can lead to a situation where the Folder view in Lightroom is no longer an accurate representation of what is in the actual system folders.

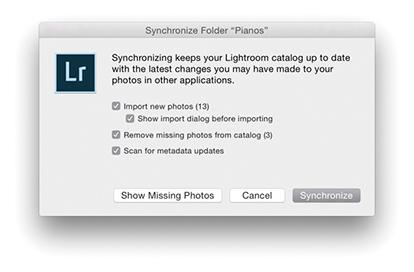

Therefore, if you need to reconcile changes that have been made to the folder contents at the system level, you can go to the Library module Library menu and choose “Synchronize folder.” When you do this, the Synchronize Folder dialog appears (Figure 3.32) and starts scanning the system folder to see if the folder contents match those shown in the corresponding Lightroom catalog folder. This provides some initial information about the differences between the two, such as whether there are any new photos to import, whether any photos in the Lightroom catalog are missing their master images, and whether any metadata changes have been made externally for which the Lightroom catalog will need to be updated.

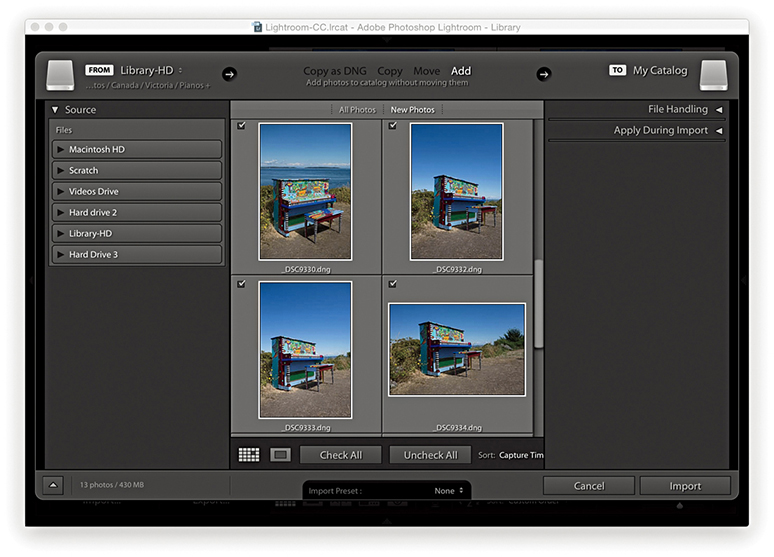

If you check the “Import new photos” option, you can choose to import any new files that have been found and add them to the catalog. By default, the Synchronize Folder dialog automatically imports files to the same folder in which they currently reside. It does this without showing the Import dialog and without modifying the filename, Develop settings, metadata, or keywords. However, you can choose “Show Import dialog before importing,” which will open the Import Photos dialog shown in Figure 3.33 and default to selecting the New Photos segmenting option. The main reason for choosing to show the Import Photos dialog when synchronizing a folder is so you can adjust any of the settings as you carry out the import and update the Lightroom catalog. If you happen to have removed any photos from the folder at the system level, you can check the “Remove missing photos from the catalog” option to also remove the files from the catalog. Basically, these options allow you to keep the Lightroom catalog updated with new additions, as well as remove photos that are no longer located in the original system folder.

The “Scan for metadata updates” option works exactly the same as the “Read metadata from files” option in the Library module Metadata menu (see page 628). For example, if you have edited the metadata in any of the catalog images using an external program, such as Bridge, which saves the metadata edits you make back to the file’s XMP header space (or to an XMP sidecar file), you can use the Synchronize Folder dialog to synchronize such metadata changes with the Lightroom catalog.

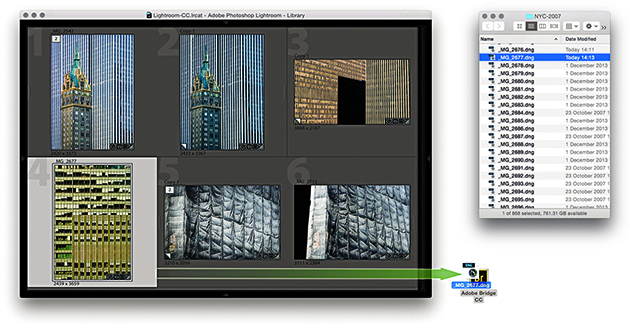

Finding the Link from the Catalog to a Folder

With Lightroom, you are free to organize and sort your photos in ways that are not directly dependent on your knowing the underlying photo structure.

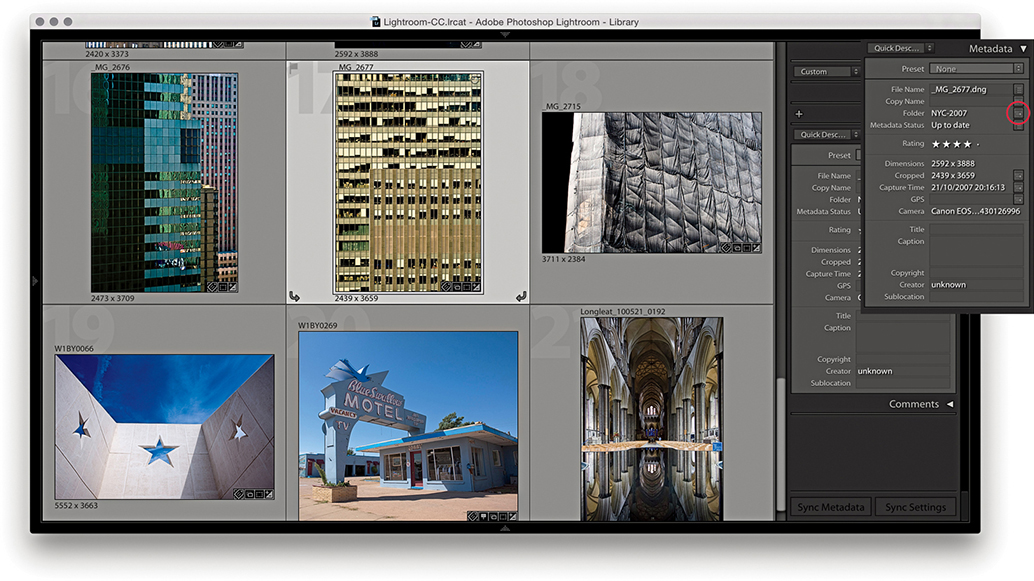

1. Here, I opened a collection of architectural photos in which the photos originated from different folders. I selected an image and clicked the Folder Action button in the Metadata panel (circled), which then took me to a Folder view for that particular photo (the folder is highlighted here in blue).

2. If I wanted to see where the photo actually resided at the system level, I could choose Photo  Show in Finder (Mac) or Show in Explorer (PC), or I could use

Show in Finder (Mac) or Show in Explorer (PC), or I could use  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) to reveal the image in a new Finder/Explorer window. I chose a third method: I simply dragged a photo from the content area to a Bridge alias/shortcut.

(PC) to reveal the image in a new Finder/Explorer window. I chose a third method: I simply dragged a photo from the content area to a Bridge alias/shortcut.

3. Dragging the file to the Bridge shortcut displayed the photo’s folder in a new Bridge window with the photo selected.

How to Organize Your Folders

People often ask how using a Lightroom catalog is different from using the Finder or a browser program to locate your images. With a system folder/browser setup, you need to know exactly where everything is kept in order to access the files. Therefore, to retrieve photos, you need to have personal knowledge of how the photos are stored: which folders are on which drives, as well as how the subfolders are arranged. If you are well organized, you might have your files sorted by date, alphabetical order, or a combination of both. Of course, if you have already added metadata to your images in the form of IPTC metadata or keywords, you can use the search command in a program like Bridge to help find the photos you are looking for. However, such searches are made easier if you use a dedicated cataloging program like Lightroom. This is because Lightroom shows you only the image and video files that have been imported and allows you to manage everything by referencing the metadata stored in the catalog.

Since the early days of personal computing, most of us have grown accustomed to relying on folder hierarchies to organize our computer documents. In fact, for a lot of people, the folder name may be the only meaningful method of identification they have for the files stored on their computers. Still, today, it seems a logical way to sort one’s files. On my computer, I have an Office documents folder inside a general Documents folder and within that a series of subfolders for things like letters, accounts files, and job quotes. But when it comes to organizing images, folder management has some distinct limitations. When you import a new set of images, how should you categorize them? Should you put them into folders arranged by date, by subject, or by job reference? When it comes to organizing photographs, it isn’t always so straightforward.

Even so, while Lightroom and other cataloging programs are not folder dependent in the way browser programs like Bridge are, the Folders panel in Lightroom remains an important navigational tool for most Lightroom users. Therefore, when working with a large catalog of images, it is important to consider early on how you are best going to organize your image files. When I first started shooting digitally, Lightroom didn’t exist and I thought I would sort all my work into A–Z folders. Now, because of the space limitations on hard drives back then, this meant I ended up spanning a lot of hard drives (Figure 3.34). Needless to say, it was not an ideal solution, and the biggest problem was that of scalability. I had to hope there would be enough room on each drive to accommodate a growing image library. Things got really difficult one year when the A–C drive started to run out of space (because I shot a lot for my A–C clients). With the arrival of Lightroom, I soon realized that the folder location where the files were kept no longer mattered so much. From there on, as I added new images, I found that the file organization did not need to be rigidly determined by which drives the files and folders were stored on. Basically, when you make use of metadata information to manage your files, the folder storage method you use is less relevant.

So, how should you organize your files and folders for Lightroom? I have seen a number of strategies suggested. The main thing you need to consider, as I said, is the scalability of the system you are going to use. As your collection of photographs grows, how well will your folder organization keep pace with this? I find it helps to split my catalog photos into different categories. For example, I have one drive for raw files shot on assignment, another to store the derivative versions that have been edited in Photoshop, and another to store all my personal work. This leaves me with quite a bit of breathing space on each drive; each is currently running at around 60% to 80% capacity. Not too long from now I will probably migrate all my files to even bigger drives. This is a process I see being repeated every few years or so.

Attempting to organize folders by name can prove tricky because you have to decide whether to primarily sort by location or job reference or some other criteria. But despite such drawbacks, it is a system that many people feel comfortable with. From my own point of view, I also find myself dependent on having a folder structure that integrates well when browsing in Bridge (because I need to demo Bridge workflows in my other books). I therefore find it necessary still to use a job-name or location-name hierarchy when cataloging my photos. This is what works for me because of my particular requirements. If you are mostly going to rely on Lightroom to catalog your photos, you could use a date-import folder structure. Importing everything into dated folders keeps things simple: The folder structure you use is agnostic as to the types of images you are importing (i.e., whether the photos are work or personal). It also allows you to be consistent and makes it easier to manage the catalog as more drives are required.

Lastly, you can use folders as a tool for segregating images in an image-processing workflow. In Chapter 2, I suggested importing your photos to a standard import folder. Here, you can think of using folders as part of a workflow pipeline in which the first thing you do is simply get the photos from the camera card onto the computer without having to immediately think about where the imported photos will eventually end up. In Figure 3.35, I have adapted a folder workflow first suggested by Peter Krogh, in which all photos are imported to an Import folder. From there, the next stage would be to move them to a Photos to keyword folder. This would be another holding folder, which would be like a reminder that the photos in there needed to be keyworded before they are promoted into one of the main catalog folders. At this point, you could then choose to categorize these main folders using descriptions, dates, or whatever works best for your setup. This kind of workflow offers simplicity and enforces good working practice where files are added to the main catalog only after they have been properly keyworded and you are ready to decide where they should go. If you use keywords to tag your images, it should not matter how the folders are structured. In fact, when you think about it, the way a computer actually segregates files into folders is done by applying a folder metadata tag to the files—the folder designation is simply another type of metadata. It takes just as much time to select all the photos from an imported shoot and assign a keyword tag as it does to name a folder. Hence, a workflow folder pipeline approach forces you to first think about assigning keywords to your images before you eventually place them into their final folders. I do not think it is necessary to be too prescriptive here as to how you should go about this.

The main thing to think about is how well will your method of archiving cope as your image library collection expands? One option is the bucket system, which Peter Krogh advocates in The DAM Book: Digital Asset Management for Photographers, 3rd Edition. In this system, the catalog files are divided into a dated hierarchy of folders of equal size and the folder capacity matches that of DVD or Blu-ray recordable media. The idea here is that you have a DVD or Blu-ray disc that matches each folder in the catalog. In the event of file corruption or data loss (in chich the error may have been copied across to a backup drive), you will always have an optical, read-once media disc available to restore the files from (think 3-2-1; see the Tip). A system like this can provide the ultimate security for your data. In practice, I think most people will be fine as long as they carry out regular, scheduled backups to one or more backup drives.

Tip

If you want to keep your data safe, Peter Krogh recommends you use the 3-2-1 backup rule: Have at least three independent copies of your data. Store the copies on two different types of media, and keep one backup copy offsite.

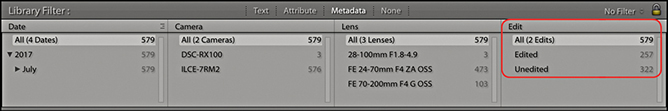

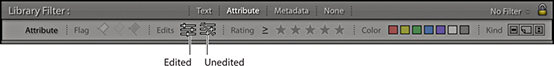

The Filter Bar

The Filter bar (Figure 3.36) consists of a Text search section for searching by filename, caption, keywords, and so forth. The Attribute section duplicates the filter controls at the bottom of the Filmstrip, while the Metadata section lets you filter by various metadata criteria. The metadata search options reduce as you narrow the search criteria at each stage. A downside to using the Filter bar is that it does take up quite a bit of space in the content area, but you can use the  keyboard shortcut to toggle showing/hiding the Filter bar.

keyboard shortcut to toggle showing/hiding the Filter bar.

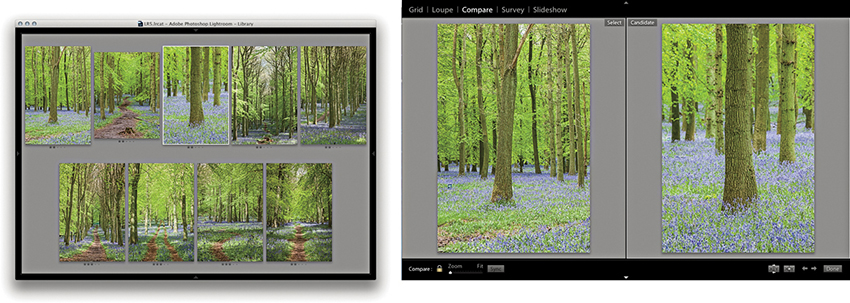

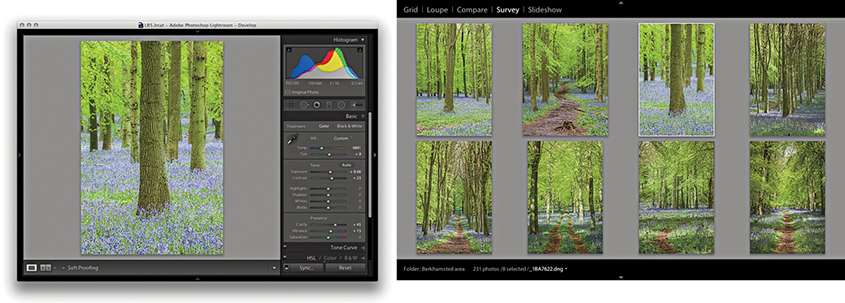

Exploring the Library Module

The Library module’s two main views, Grid and Loupe, offer plenty of options to help you tailor them to your workflow and display the details you need most.

Grid View Options

As new photos are imported, low-resolution previews will appear in the Grid view. If the camera used to capture the images has the camera orientation information embedded in the metadata, the thumbnail previews should correctly rotate to portrait or landscape mode accordingly. Otherwise, you can use the rotate buttons to rotate the images manually or use  to rotate left and

to rotate left and  to rotate right (Mac), or use

to rotate right (Mac), or use  and

and  (PC).

(PC).

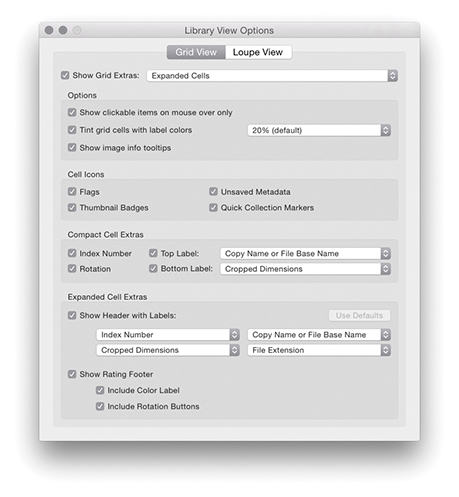

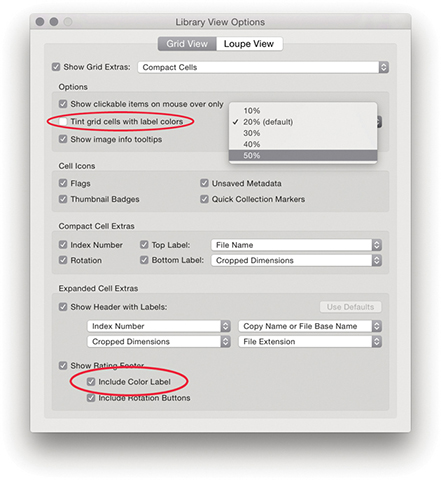

To open the Library View Options, choose View  View Options (or press

View Options (or press  [Mac] or

[Mac] or  [PC]) and click the Grid View button (Figure 3.37). There are essentially two modes for the Library Grid View: Compact Cells (Figure 3.38), which primarily shows the thumbnail with less data information, and Expanded Cells (Figure 3.39), which displays additional options in each cell. The “Show clickable items on mouse over only” option refers to the Quick Collection markers and rotation buttons. When you select this option, such clickable items are revealed only as you hover over a cell. When the “Tint grid cells with label colors” option is selected, this shades the entire cell border when you apply a color label to a photo and you can adjust the intensity of the tint color. “Show image info tooltips” enables you see additional info messages when rolling over the cell badge icons.

[PC]) and click the Grid View button (Figure 3.37). There are essentially two modes for the Library Grid View: Compact Cells (Figure 3.38), which primarily shows the thumbnail with less data information, and Expanded Cells (Figure 3.39), which displays additional options in each cell. The “Show clickable items on mouse over only” option refers to the Quick Collection markers and rotation buttons. When you select this option, such clickable items are revealed only as you hover over a cell. When the “Tint grid cells with label colors” option is selected, this shades the entire cell border when you apply a color label to a photo and you can adjust the intensity of the tint color. “Show image info tooltips” enables you see additional info messages when rolling over the cell badge icons.

If you want the image’s flag status to appear in the cell border, check the Flags option in the Cell Icons section. The Flag icons indicate if an image has been identified as a pick ( ) or as a reject (

) or as a reject ( ) (see page 126 for more about working with flags). The Thumbnail Badges are the small icons you see in the bottom-right corner. Five types of badges can be displayed here, depending on what attributes have been applied to each image. If you double-click the Keywords badge (

) (see page 126 for more about working with flags). The Thumbnail Badges are the small icons you see in the bottom-right corner. Five types of badges can be displayed here, depending on what attributes have been applied to each image. If you double-click the Keywords badge ( ), this automatically takes you to the Keywording panel in the Library module, where you can start adding or editing keywords linked to this particular image. Double-clicking the Crop badge (

), this automatically takes you to the Keywording panel in the Library module, where you can start adding or editing keywords linked to this particular image. Double-clicking the Crop badge ( ) takes you to the Develop module and activates the Crop overlay. If you double-click the Develop settings badge (

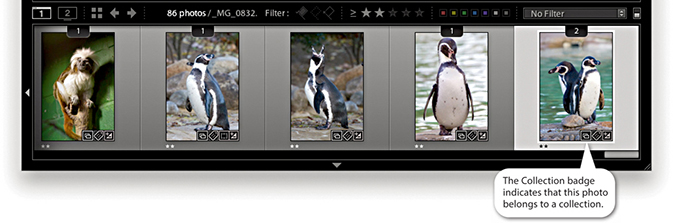

) takes you to the Develop module and activates the Crop overlay. If you double-click the Develop settings badge ( ), you also go directly to the Develop module, and if you click the Collections badge (

), you also go directly to the Develop module, and if you click the Collections badge ( ), a pop-up menu appears allowing you to select from one or more collections the photo belongs to. Lastly, there is a Map badge to indicate if a photo has GPS data (

), a pop-up menu appears allowing you to select from one or more collections the photo belongs to. Lastly, there is a Map badge to indicate if a photo has GPS data (![]() ). Clicking this takes you to the photo’s map location in the Map module, while

). Clicking this takes you to the photo’s map location in the Map module, while  -clicking takes you directly to a Google Maps view in your web browser. Check the Unsaved Metadata option if you wish to see an alert in the top-right corner if a photo’s metadata is out of sync with the main catalog (this is discussed later in Chapter 10). If a photo has been added to a Quick Collection, it will be identified in the Grid view with a filled circle Quick Selection Marker in the top-right corner. You can also click this circle to toggle adding or removing an image from a Quick Collection.

-clicking takes you directly to a Google Maps view in your web browser. Check the Unsaved Metadata option if you wish to see an alert in the top-right corner if a photo’s metadata is out of sync with the main catalog (this is discussed later in Chapter 10). If a photo has been added to a Quick Collection, it will be identified in the Grid view with a filled circle Quick Selection Marker in the top-right corner. You can also click this circle to toggle adding or removing an image from a Quick Collection.

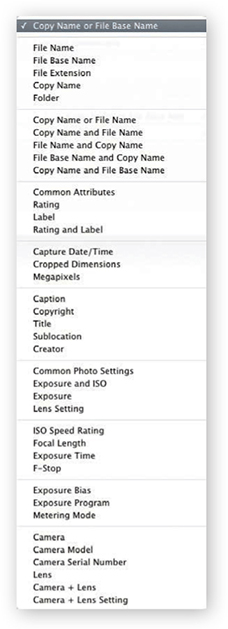

Figure 3.38 shows an example of a Compact Cell view (which is the default view when you first launch Lightroom). This particular cell view has the grid cell Index Number (the large dimmed number in the cell background) displayed in the Top Label section, along with the Copy Name or File Base Name (selected from the Figure 3.40 list). The Bottom Label section has room for the Rotation buttons, plus one other custom item from the Figure 3.40 list. When Rating is selected, the image rating is displayed, with five stars as the highest rated and no stars as the lowest. Although it is possible to assign star ratings by clicking the dots in the grid cell area, an easier way to assign ratings is to enter numbers (1–5) or use the square bracket keys ( ,

,  ) on the keyboard.

) on the keyboard.

Figure 3.39 shows an example of an Expanded Cells view. You can use the Show Header with Labels check box in the Expanded Cell Extras section to turn the header display options on or off. With the Expanded Cells view, there is room for two rows of information in the header, and you can use the pull-down menu list shown in Figure 3.40 to customize the information displayed here. You can also check the Show Rating Footer option to enable adding the Include Color Label and Include Rotation Buttons options. That concludes all the customizable options for the Grid cells, but note you can use the  keyboard shortcut to cycle through the three Grid cell views: “Compact view with no badges,” “Compact view with badges showing,” and “Expanded view with badges showing.”

keyboard shortcut to cycle through the three Grid cell views: “Compact view with no badges,” “Compact view with badges showing,” and “Expanded view with badges showing.”

Library Grid Navigation

The main way to browse photos in the catalog is to use the Library module in the Grid view mode (Figure 3.41). You can navigate the Grid view by clicking on individual cells or use the arrow keys on the keyboard to move from one cell to the next. The Home and End keys on the computer keyboard can be used to move the Grid view to the first or last image, and you can also scroll the grid contents using the Page Up and Page Down keys next to these two keys. To make the thumbnail sizes bigger or smaller, you can drag the Thumbnails slider in the Toolbar, or use the keyboard + and – keys to increase or decrease the number of cells per row. The Library grid cells are displayed in the main content area, and the side panels can be hidden by clicking the left or right sidebar edges—this collapses the panels to the edge of the Lightroom window. The panels can then be revealed by rolling the pointer toward either sidebar edge or kept locked in place by clicking the sidebar edges. An even easier way to manage the Library Grid view is to use the  key to toggle having the side panels in view or with both hidden, enlarging the content area to fill the complete width of the window. And, you can use

key to toggle having the side panels in view or with both hidden, enlarging the content area to fill the complete width of the window. And, you can use  to toggle showing the side plus top and bottom panels.

to toggle showing the side plus top and bottom panels.

Note

Lightroom Classic CC uses new APIs, which means Windows users should see faster rendering in the Grid, Filmstrip, and Loupe views. Windows 10 also supports GPU acceleration in Library module.

Note

Here are some keyboard shortcuts for navigating between the Grid and Loupe views. The  key always takes you to the Library Grid view from whichever module you are currently in, and the

key always takes you to the Library Grid view from whichever module you are currently in, and the  key always takes you to the Library module Loupe view. The

key always takes you to the Library module Loupe view. The  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) key combination takes you from Grid to Loupe standard view, and the

(PC) key combination takes you from Grid to Loupe standard view, and the  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) key combination takes you from the standard Loupe view back to Grid view. More Loupe view shortcuts are listed on page 105.

(PC) key combination takes you from the standard Loupe view back to Grid view. More Loupe view shortcuts are listed on page 105.

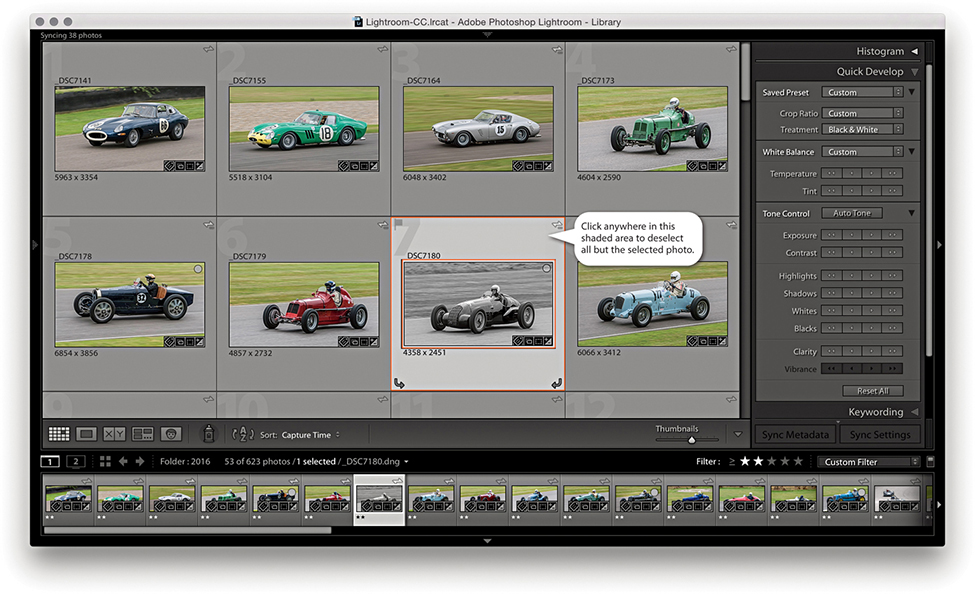

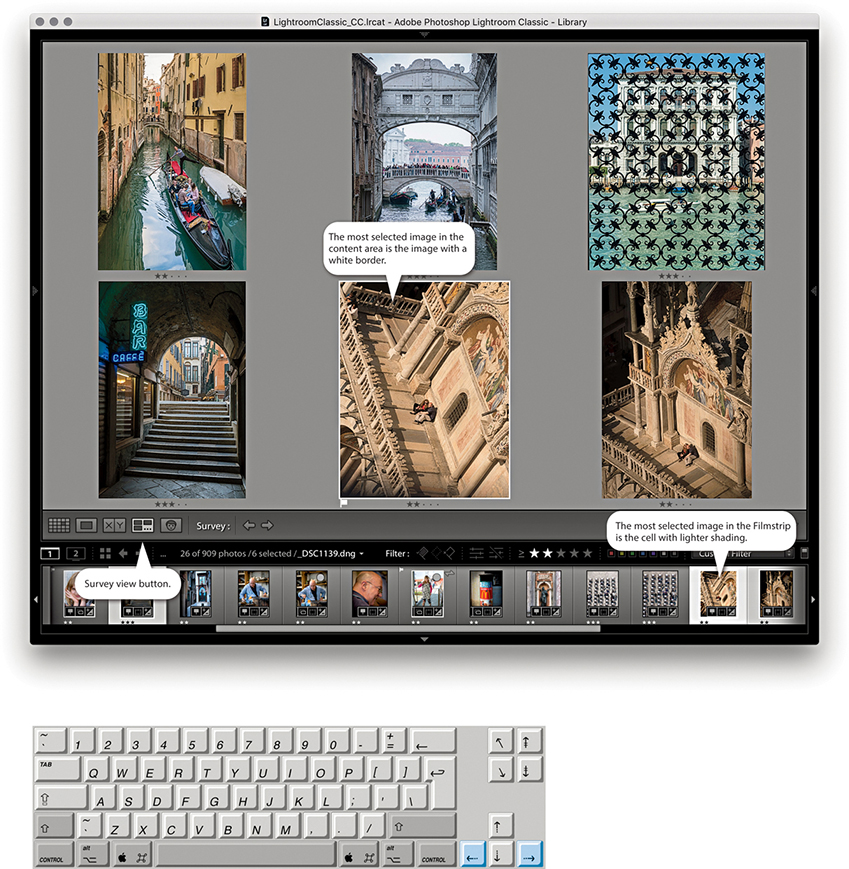

The selected thumbnails are shown in both the Grid and Filmstrip with a light-gray surround. Within a photo selection of two or more photos, there will always be a primary or “most selected” image (which will also be the one displayed in the Navigator). You can tell which this is because in the Grid or Filmstrip, the primary selected image is the one shaded a slightly lighter gray than all the other selected thumbnail cells. When a selection of photos is active, you can click to make another image in the photo selection the most active. Or, you can use the  key (Mac) or

key (Mac) or  key (PC) combined with the left/right arrows to select another photo as the “most selected” image within the current photo selection. Some macOS users may experience problems navigating using the keyboard arrows. If you do, go to the System Preferences and select Keyboard

key (PC) combined with the left/right arrows to select another photo as the “most selected” image within the current photo selection. Some macOS users may experience problems navigating using the keyboard arrows. If you do, go to the System Preferences and select Keyboard  Keyboard Shortcuts. At the very bottom, you will see “Full Keyboard Access: In windows and dialogs, press Tab to move the keyboard focus between.” Make sure the “Text boxes and Lists only” option is selected here.

Keyboard Shortcuts. At the very bottom, you will see “Full Keyboard Access: In windows and dialogs, press Tab to move the keyboard focus between.” Make sure the “Text boxes and Lists only” option is selected here.

You can reorder the way the photos appear by dragging the thumbnails within the Grid or Filmstrip. As you move a photo from one location to another, you will see a thick black line appear between the cells. Release to drop the photo (or photos) in this new location. But it is important to stress here that you can do this only when working with a single folder or single collection view. Otherwise, you will find custom ordering is disabled. For example, if you have multiple folders selected or you have selected a folder that contains one or more subfolders, you will not be able to drag images to reorder them. Similarly, if you create a collection set that contains other collections or if you are viewing a temporary collection in the Catalog panel, custom ordering will be disabled.

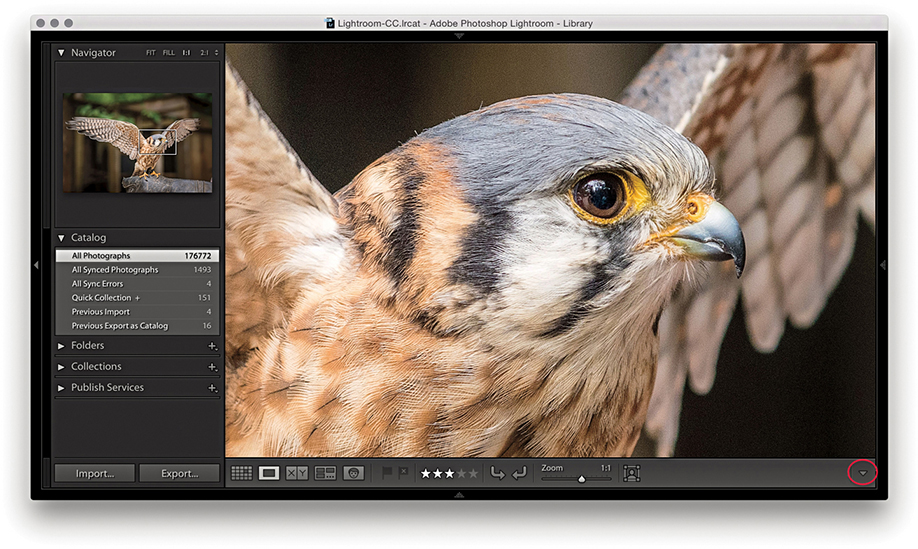

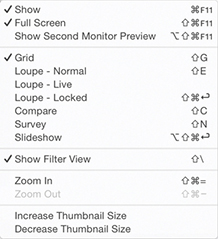

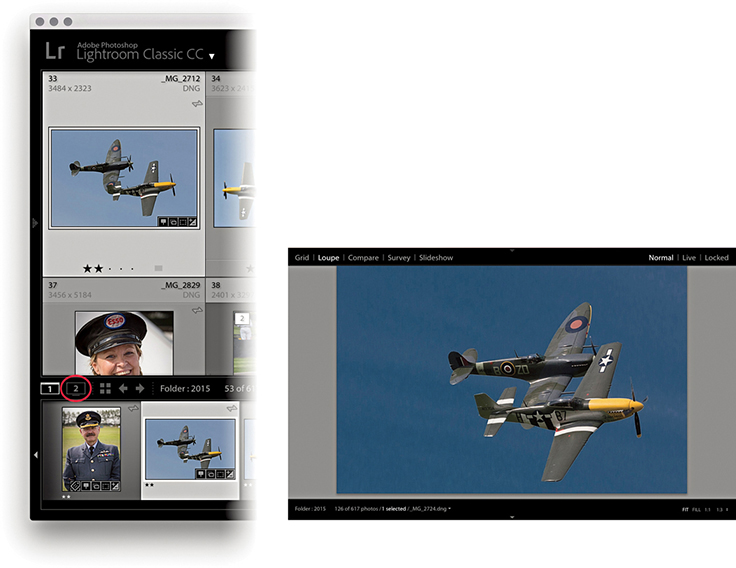

Working in Loupe view

Lightroom offers two Loupe viewing modes: standard and close-up. The standard Loupe view either fits the whole image within the content area or fills the entire width of the content area; these are described as Fit and Fill (Fit is shown in Figure 3.42). The close-up Loupe view can be set to a 1:1 magnification or an alternative zoomed-in custom view setting, such as 2:1 or higher. The simplest way to switch to the Loupe view is to double-click an image in the Grid or Filmstrip. If you have more than one photo currently selected, the photo you double-click is the one that will fill the screen. The photo selection will still be preserved in the Filmstrip, and you can use the Left and Right Arrow keys to navigate through these photos. If you double-click the Loupe view image, you will return to the Grid view once more.

Loupe Preview Updates in Library Module

As you switch from the Develop to the Library module Loupe view, there is an optimization in place for the Library Loupe view to reuse the Develop module rendering instead of having to re-render a JPEG preview. This typically happens if you made an edit in the Develop module and the Library module JPEG preview therefore becomes out-of-date. Consequently, your images should display faster as you progress from one to the next.

Loupe View Options

The Loupe view options in the Library View Options dialog ( [Mac] or

[Mac] or  [PC]) can be used to customize the Loupe view (Figure 3.43). When the Show Info Overlay option is selected, Lightroom displays an info overlay in the top-left corner, which can use the Loupe Info settings Info 1 or Info 2, as configured below. If the Show Info Overlay option is unselected, you then have the option to select the “Show briefly when photo changes” option for when a new image is displayed in the Loupe view. This means the info overlay will fade after a few seconds when you select a new image in the Loupe view. You can also control the Loupe view options by using the

[PC]) can be used to customize the Loupe view (Figure 3.43). When the Show Info Overlay option is selected, Lightroom displays an info overlay in the top-left corner, which can use the Loupe Info settings Info 1 or Info 2, as configured below. If the Show Info Overlay option is unselected, you then have the option to select the “Show briefly when photo changes” option for when a new image is displayed in the Loupe view. This means the info overlay will fade after a few seconds when you select a new image in the Loupe view. You can also control the Loupe view options by using the  (Mac) or

(Mac) or  (PC) shortcut to toggle switching the Loupe view information on or off. Or, you can also use the

(PC) shortcut to toggle switching the Loupe view information on or off. Or, you can also use the  key to cycle between showing Info 1 and Info 2, as well as switching the Info display off. Figure 3.44 shows a Library module Loupe view captured with a Loupe Info 1 overlay.

key to cycle between showing Info 1 and Info 2, as well as switching the Info display off. Figure 3.44 shows a Library module Loupe view captured with a Loupe Info 1 overlay.

Tip

The View menu contains an item called Enable Mirror Image Mode. However, when you check this option, it flips all the photos in the catalog horizontally and not just those in the current Library selection. So, remember to deselect it after you are finished! To turn it off, just select it from the View menu again. A better option now is to go to the Photo menu and choose Flip Horizontal or Flip Vertical. These commands are applied to individual images only.

When the “Show message when loading or rendering photos” option is selected, you will see status messages appear in the content area, such as when an image is loading an updated preview or you have just assigned a new flag or star rating to a photo. The other two options relate to displaying video files. You can choose to display the frame number when displaying the video time. This shows finer time increments in the video timeline display. Enabling the “Play HD video at draft quality” option can improve playback performance in the Library module Loupe view, but at the expense of lower video image quality.

Draw Face Region Overlay

When the Draw Face Region tool is selected in the Toolbar, it enables the face recognition feature. This will display a rectangular face region around any faces found in an image and will include text that either shows the person’s name or says “Unnamed.” When the Draw Face Region tool is selected, you can also click and drag inside the Loupe view to manually define face regions.

Working with Photos in Both Grid and Loupe View

1. In the Grid view mode, you can make a selection of photos, and the selection will be mirrored in the Filmstrip below.

2. If you use Quick Develop to make Develop adjustments, these are applied to all photos in the grid and Filmstrip selection (the Quick Develop panel is ideal for such adjustments). Here, I decreased the Exposure for all the selected images.

3. If you go to the Loupe view mode and apply a Quick Develop adjustment (such as convert to Black & White), however, the adjustment is applied only to the current photo, even though the photo selection remains active in the Filmstrip.

4. Back in the Grid view, you can deselect a photo selection by clicking anywhere in the cell border area to deselect all but the selected photo.

Loupe View Navigation

From the standard Loupe view, you can magnify the image preview in a number of ways. A further click will normally zoom in to a 1:1 magnification, centered on where you click (see Note). Another click will take you back to the previous Loupe view (Figure 3.45 shows a close-up Loupe view). Zooming is made faster by the fact that Lightroom renders only the portion of the image you have selected to view in close-up instead of rendering the whole image first. The close-up Loupe view is handy for checking image detail. You can navigate from one image to the next in a selection, using the keyboard Arrow keys, and inspect the same area of each image in close-up view. In the View menu is an item called Lock Zoom Position ( [Mac] or

[Mac] or  [PC]). When selected, it locks the zoom position when switching between images. When the Lock Zoom Position is unselected, the zoom position is remembered for each individual image. Be aware that if the Draw Face Region tool is enabled (see Figure 3.38), you will be in the Define Face Region mode, where you can click and drag to define a new face region. To exit this mode, you will need to click in the Toolbar to disable the Draw Face Region tool. You can then click and zoom again to navigate the image.

[PC]). When selected, it locks the zoom position when switching between images. When the Lock Zoom Position is unselected, the zoom position is remembered for each individual image. Be aware that if the Draw Face Region tool is enabled (see Figure 3.38), you will be in the Define Face Region mode, where you can click and drag to define a new face region. To exit this mode, you will need to click in the Toolbar to disable the Draw Face Region tool. You can then click and zoom again to navigate the image.

Note

In the Lightroom Interface preferences, the “Zoom clicked point to center” option lets you alter the zooming behavior. When this option is unselected, zooming in close fills the screen to best fit the content area. When it is selected, where you click is always centered on the screen. I find zooming is more natural when the option is left unselected: After you zoom in, the pointer remains positioned over the point where you originally clicked.

You can scroll by click-dragging the photo. Alternatively, you can drag the white rectangle in the Navigator panel (Figure 3.46) to quickly scroll the image with a minimum amount of movement. In the full-screen Loupe view shown in Figure 3.45, the rectangle in the Navigator represented the area that was currently visible in the content area (relative to the whole image). Lastly, you have the Zoom view slider in the Toolbar. This lets you magnify the image from a Fit view, right up to an 11:1 magnification.

Loupe Zoom Views

There are actually four different Loupe views, and the Navigator panel displays a highlighted zoom view readout in the top-right corner of whichever one is currently in use. They are (in order of magnification): Fit view, which displays a standard Loupe view, filling the available content area both horizontally and vertically; Fill view, which magnifies the standard Loupe view to fill the width of the available content area onscreen, cropping the top and bottom of the picture as necessary; close-up Loupe view, which offers a standard 1:1 view; and a second close-up view, which offers customized magnification levels. You can extend the close-up Loupe view range for this view mode by selecting a new zoom view from the Navigator fly-out menu (Figure 3.46). Therefore, the Loupe zoom essentially offers two zoom modes: a standard view and a close-up view. You can use the Navigator panel to set the standard view to either Fit or Fill, and the close-up view to either 1:1 or one of the custom magnified views. The zoom view modes you select via the Navigator panel also establish how Lightroom behaves when you use either a single-click or press the  to toggle between the two zoom views.

to toggle between the two zoom views.

Loupe View Shortcuts

By now, you will have come to realize that there are umpteen ways to zoom in and out of an image between the Grid view and Loupe view modes. It is not easy to remember all the zoom shortcuts, so I suggest you play with the various methods described here and just get used to working with whatever method suits you best. For example, you can use the  keys (Mac) or

keys (Mac) or  keys (PC) to zoom in progressively from the Grid view to the standard Loupe view to the magnified Loupe view. And you can use the

keys (PC) to zoom in progressively from the Grid view to the standard Loupe view to the magnified Loupe view. And you can use the  keys (Mac) or

keys (Mac) or  keys (PC) to progressively zoom out again. You can use the

keys (PC) to progressively zoom out again. You can use the  keys (Mac) or

keys (Mac) or  keys (PC) with the

keys (PC) with the  and

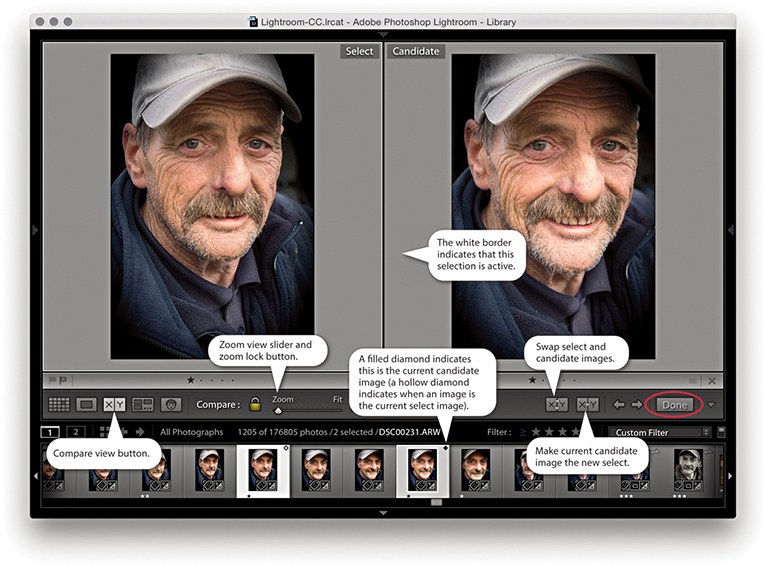

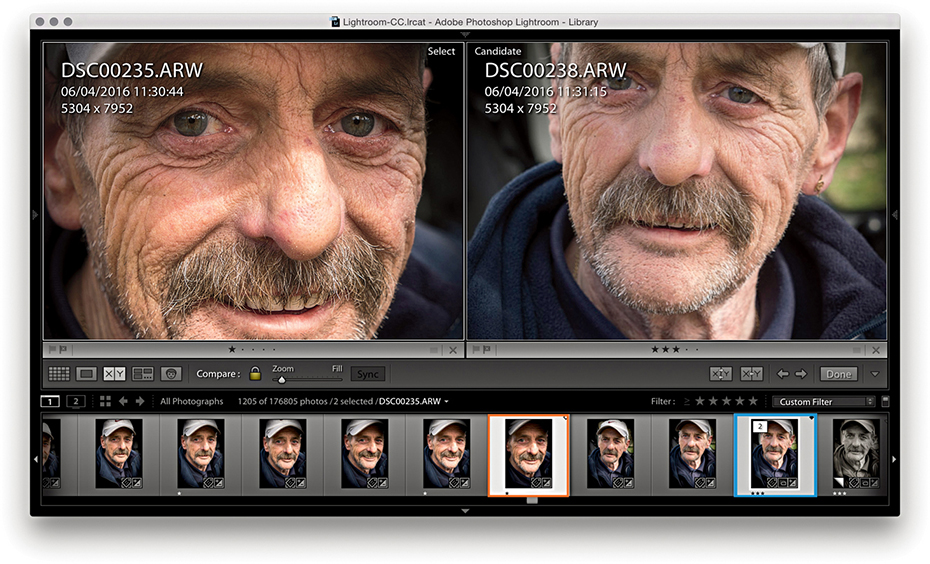

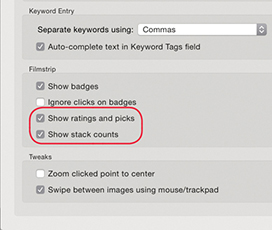

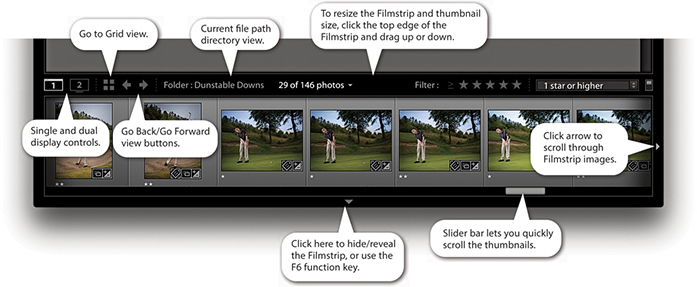

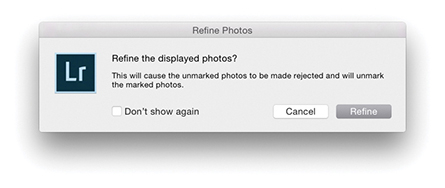

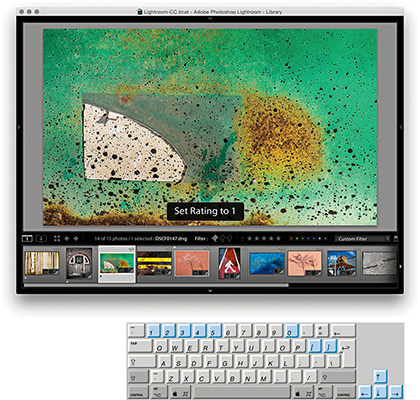

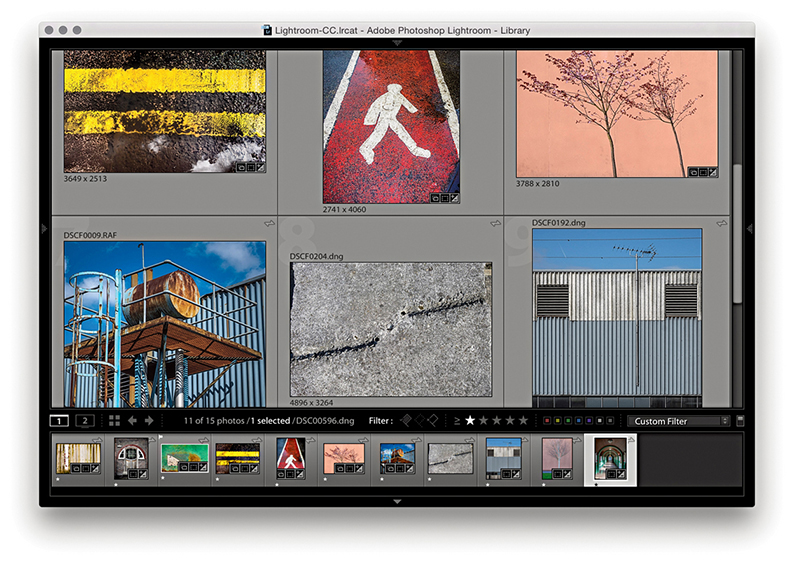

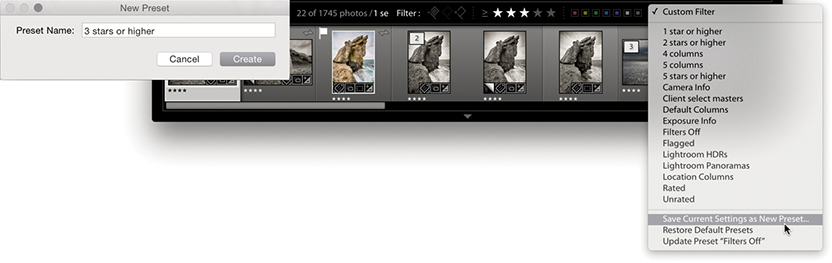

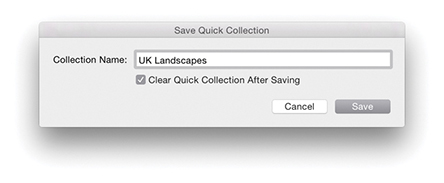

and  buttons to zoom in and out in gradual increments from the Grid view to an 11:1 Loupe view. You can also use the