You will recall from our short discussion of the protocols used in an IPX environment that IPX is a routable protocol and that the Routing Information Protocol (RIP) is used to propagate routing information. The IPX version of RIP is quite similar to the IP version. They operate in essentially the same way; routers periodically broadcast the contents of their routing tables and other routers learn of them by listening and integrating the information they receive. Hosts need only know who their local network is and be sure to send datagrams for all other destinations via their local router. The router is responsible for carrying these datagrams and forwarding them on to the next hop in the route.

In an IPX environment, a second class of information must be propagated around the network. The Service Advertisement Protocol (SAP) carries information relating to which services are available at which hosts around the network. It is the SAP protocol, for example, that allows users to obtain lists of file or print servers on the network. The SAP protocol works by having hosts that provide services periodically broadcast the list of services they offer. The IPX network routers collect this information and propagate it throughout the network alongside the network routing information. To be a compliant IPX router, you must propagate both RIP and SAP information.

Just like IP, IPX on Linux provides a routing daemon named ipxd to perform the tasks associated with managing routing. Again, just as with IP, it is actually the kernel that manages the forwarding of datagrams between IPX network interfaces, but it performs this according to a set of rules called the IPX routing table. The ipxd daemon keeps that set of rules up to date by listening on each of the active network interfaces and analyzing when a routing change is necessary. The ipxd daemon also answers requests from hosts on a directly connected network that ask for routing information.

The ipxd command is available prepackaged in some

distributions, and in source form by anonymous FTP from

http://metalab.unc.edu/in the

/pub/Linux/system/filesystems/ncpfs/ipxripd-x.xx.tgz

file.

No configuration is necessary for the ipxd daemon. When it starts, it automatically manages routing among the IPX devices that have been configured. The key is to ensure that you have your IPX devices configured correctly using the ipx_interface command before you start ipxd. While auto-detection may work, when you’re performing a routing function it’s best not to take chances, so manually configure the interfaces and save yourself the pain of nasty routing problems. Every 30 seconds, ipxd rediscovers all of the locally attached IPX networks and automatically manages them. This provides a means of managing networks on interfaces that may not be active all of the time, such as PPP interfaces.

The ipxd would normally be started at boot time from

an rc boot script like this:

# /usr/sbin/ipxd

No & character is necessary because ipxd will

move itself into the background by default. While the

ipxd daemon is most useful on machines acting as

IPX routers, it is also useful to hosts on segments where there are

multiple routers present. When you specify the

-p argument, ipxd will act

passively, listening to routing information from the segment and

updating the routing tables, but it will not transmit any routing

information. This way, a host can keep its routing tables up to date

without having to request routes each time it wants to contact a

remote host.

There are occasions when we might want to hardcode an IPX route. Just as with IP, we can do this with IPX. The ipx_route command writes a route into the IPX routing table without it needing to have been learned by the ipxd routing daemon. The routing syntax is very simple (since IPX does not support subnetworking) and looks like:

# ipx_route add 203a41bc 31a10103 00002a02b102The command shown would add a route to the remote IPX network 203a41bc via the router on our local network 31a10103 with node address 00002a02b102.

You can find the node address of a router by making judicious use of

the tcpdump command with the

-e argument to display link level

headers and look for traffic from the router. If the router is a Linux

machine, you can more simply use the ifconfig

command to display it.

You can delete a route using the ipx_route command:

# ipx_route del 203a41bc

You can list the routes that are active in the kernel by looking at

the /proc/net/ipx_route file. Our routing table

so far looks like this:

# cat ipx_route

Network Router_Net Router_Node

203A41BC 31A10103 00002a02b102

31A10103 Directly Connected

The route to the 31A10103 network was automatically created when we configured the IPX interface. Each of our local

networks will be represented by an /proc/net/ipx_route

entry like this one. Naturally, if our machine is to act as a router, it will

need at least one other interface.

IPX hosts with more than one IPX interface have a unique network/node address combination for each of their interfaces. To connect to such a host, you may use any of these network/node address combinations. When SAP advertizes services, it supplies the network/node address associated with the service that is offered. On hosts with multiple interfaces, this means that one of the interfaces must be chosen as the one to propagate; this is the function of the primary interface flag we talked about earlier. But this presents a problem: the route to this interface may not always be the optimal one, and if a network failure occurs that isolates that network from the rest of the network, the host will become unreachable even though there are other possible routes to the other interfaces. The other routes are never known to other hosts because they are never propagated, and the kernel has no way of knowing that it should choose another primary interface. To avoid this problem, a device was developed that allows an IPX host to be known by a single route-independent network/node address for the purposes of SAP propagation. This solves our problem because this new network/node address is reachable via all of the host interfaces, and is the one that is advertised by SAP.

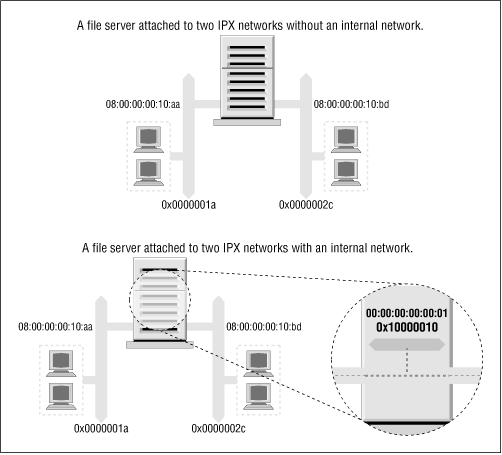

To illustrate the problem and its solution, Figure 15.1 shows a server attached to two IPX networks. The first network has no internal network, but the second does. The host in diagram Figure 15.1 would choose one of its interfaces as its primary interface, let’s assume 0000001a:0800000010aa, and that is what would be advertised as its service access point. This works well for hosts on the 0000001a network, but means that users on the 0000002c network will route via the network to reach that port, despite the server having a port directly on that network if they’ve discovered this server from the SAP broadcasts.

Allowing such hosts to have a virtual network with virtual host addresses that are entirely a software construct solves this problem. This virtual network is best thought of as being inside the IPX host. The SAP information then needs only to be propagated for this virtual network/node address combination. This virtual network is known as an internal network. But how do other hosts know how to reach this internal network? Remote hosts route to the internal network via the directly connected networks of the host. This means that you see routing entries that refer to the internal network of hosts supporting multiple IPX interfaces. Those routes should choose the optimal route available at the time, and should one fail, the routing is automatically updated to the next best interface and route. In Figure 15.1, we’ve configured an internal IPX network of address 0x10000010 and used a host address of 00:00:00:00:00:01. It is this address that will be our primary interface and will be advertised via SAP. Our routing will reflect this network as being reachable via either of our real network ports, so hosts will always use the best network route to connect to our server.

To create this internal network, use the ipx_internal_net command included in Greg Page’s IPX tools package. Again, a simple example demonstrates its use:

# ipx_internal_net add 10000010 000000000001This command would create an IPX internal network with address 10000010 and a node address of 000000000001. The network address, just like any other IPX network address, must be unique on your network. The node address is completely arbitrary, as there will normally be only one node on the network. Each host may have only one IPX Internal Network, and if configured, the Internal Network will always be the primary network.

To delete an IPX Internal Network, use:

# ipx_internal_net del

An internal IPX network is of absolutely no use to you unless your host both provides a service and has more than one IPX interface active.