We’ve been talking quite a bit about network interfaces and general TCP/IP issues, but we haven’t really covered what happens when the “networking code” in the kernel accesses a piece of hardware. In order to describe this accurately, we have to talk a little about the concept of interfaces and drivers.

First, of course, there’s the hardware itself, for example an Ethernet, FDDI or Token Ring card: this is a slice of Epoxy cluttered with lots of tiny chips with strange numbers on them, sitting in a slot of your PC. This is what we generally call a physical device.

For you to use a network card, special functions have to be present in your Linux kernel that understand the particular way this device is accessed. The software that implements these functions is called a device driver. Linux has device drivers for many different types of network interface cards: ISA, PCI, MCA, EISA, Parallel port, PCMCIA, and more recently, USB.

But what do we mean when we say a driver “handles” a device? Let’s consider an Ethernet card. The driver has to be able to communicate with the peripheral’s on-card logic somehow: it has to send commands and data to the card, while the card should deliver any data received to the driver.

In IBM-style personal computers, this communication takes place through a

cluster of I/O addresses that are mapped to registers on the card and/or

through shared or direct memory transfers. All commands and data the kernel

sends to the card have to go to these addresses. I/O and memory addresses are

generally described by providing the starting or

base address. Typical base addresses for ISA bus Ethernet

cards are 0x280 or 0x300. PCI bus

network cards generally have their I/O address automatically assigned.

Usually you don’t have to worry about any hardware issues such as the base address because the kernel makes an attempt at boot time to detect a card’s location. This is called auto probing, which means that the kernel reads several memory or I/O locations and compares the data it reads there with what it would expect to see if a certain network card were installed at that location. However, there may be network cards it cannot detect automatically; this is sometimes the case with cheap network cards that are not-quite clones of standard cards from other manufacturers. Also, the kernel will normally attempt to detect only one network device when booting. If you’re using more than one card, you have to tell the kernel about the other cards explicitly.

Another parameter that you might have to tell the kernel about is the interrupt request line. Hardware components usually interrupt the kernel when they need to be taken care of—for example, when data has arrived or a special condition occurs. In an ISA bus PC, interrupts may occur on one of 15 interrupt channels numbered 0, 1, and 3 through 15. The interrupt number assigned to a hardware component is called its interrupt request number (IRQ).[17]

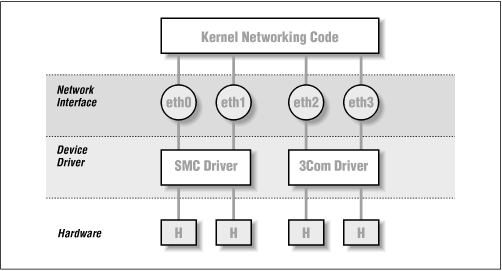

As described in Chapter 2, the kernel accesses a piece of network hardware through a software construct called an interface. Interfaces offer an abstract set of functions that are the same across all types of hardware, such as sending or receiving a datagram.

Interfaces are identified by means of

names. In many other Unix-like operating systems, the network

interface is implemented as a special device file in the

/dev/ directory. If you type the ls -las /dev/ command, you will see what these device files look

like. In the file permissions (second) column you will see that device

files begin with a letter rather than the hyphen seen for normal

files. This character indicates the device type. The most common

device types are b, which indicates the device is a

block device and handles whole blocks of data

with each read and write, and c, which indicates

the device is a character device and handles data

one character at a time. Where you would normally see the file length

in the ls output, you instead see two numbers,

called the major and minor device numbers. These numbers indicate the

actual device with which the device file is associated.

Each device driver registers a unique major number with the kernel.

Each instance of that device registers a unique

minor number for that major device. The tty

interfaces,/dev/tty*, are a character

mode device indicated by the "c“, and

each have a major number of 4, but

/dev/tty1 has a minor number of

1, and /dev/tty2 has a minor

number of 2. Device files are very useful for

many types of devices, but can be clumsy to use when trying to find an

unused device to open.

Linux interface names are defined internally in the kernel and are not

device files in the /dev directory. Some typical

device names are listed later in Section 3.2.” The assignment of interfaces to

devices usually depends on the order in which devices are

configured. For instance, the first Ethernet card installed will

become eth0, and the next will be

eth1. SLIP interfaces are handled differently

from others because they are assigned dynamically. Whenever a SLIP

connection is established, an interface is assigned to the serial

port.

Figure 3.1 illustrates the relationship between the hardware, device drivers, and interfaces.

When booting, the kernel displays the devices it detects and the interfaces it installs. The following is an excerpt from typical boot messages:

.

. This processor honors the WP bit even when in supervisor mode./

Good.

Swansea University Computer Society NET3.035 for Linux 2.0

NET3: Unix domain sockets 0.13 for Linux NET3.035.

Swansea University Computer Society TCP/IP for NET3.034

IP Protocols: IGMP,ICMP, UDP, TCP

Swansea University Computer Society IPX 0.34 for NET3.035

IPX Portions Copyright (c) 1995 Caldera, Inc.

Serial driver version 4.13 with no serial options enabled

tty00 at 0x03f8 (irq = 4) is a 16550A

tty01 at 0x02f8 (irq = 3) is a 16550A

CSLIP: code copyright 1989 Regents of the University of California

PPP: Version 2.2.0 (dynamic channel allocation)

PPP Dynamic channel allocation code copyright 1995 Caldera, Inc.

PPP line discipline registered.

eth0: 3c509 at 0x300 tag 1, 10baseT port, address 00 a0 24 0e e4 e0,/

IRQ 10.

3c509.c:1.12 6/4/97 becker@cesdis.gsfc.nasa.gov

Linux Version 2.0.32 (root@perf) (gcc Version 2.7.2.1)

#1 Tue Oct 21 15:30:44 EST 1997

.

.

This example shows that the kernel has been compiled with TCP/IP

enabled, and it includes drivers for SLIP, CSLIP, and PPP. The third

line from the bottom says that a 3C509 Ethernet card was detected and

installed as interface eth0. If you have some

other type of network card—perhaps a D-Link pocket adaptor, for

example—the kernel will usually print a line starting with its

device name—dl0 in the D-Link

example—followed by the type of card detected. If you have a

network card installed but don’t see any similar message, the kernel

is unable to detect your card properly. This situation will be

discussed later in the section “Ethernet Autoprobing.”

Most Linux distributions are supplied with boot disks that work for all common types of PC hardware. Generally, the supplied kernel is highly modularized and includes nearly every possible driver. This is a great idea for boot disks, but is probably not what you’d want for long-term use. There isn’t much point in having drivers cluttering up your disk that you will never use. Therefore, you will generally roll your own kernel and include only those drivers you actually need or want; that way you save a little disk space and reduce the time it takes to compile a new kernel.

In any case, when running a Linux system, you should be familiar with building a kernel. Think of it as a right of passage, an affirmation of the one thing that makes free software as powerful as it is—you have the source. It isn’t a case of, “I have to compile a kernel,” rather it’s a case of, “I can compile a kernel.” The basics of compiling a Linux kernel are explained in Matt Welsh’s book, Running Linux (O’Reilly). Therefore, we will discuss only configuration options that affect networking in this section.

One important point that does bear

repeating here is the way the kernel version numbering scheme

works. Linux kernels are numbered in the following format:

2.2.14. The first digit indicates the

major version number. This digit changes when

there are large and significant changes to the kernel design. For

example, the kernel changed from major 1 to 2 when the kernel obtained

support for machines other than Intel machines. The second number is

the minor version number. In many respects, this

number is the most important number to look at. The Linux development

community has adopted a standard at which even minor

version numbers indicate production, or

stable, kernels and odd

minor version numbers indicate development, or

unstable, kernels. The stable kernels are what

you should use on a machine that is important to you, as they have

been more thoroughly tested. The development kernels are what you

should use if you are interested in experimenting with the newest

features of Linux, but they may have problems that haven’t yet been

found and fixed. The third number is simply incremented for each

release of a minor version.[18]

When running make menuconfig, you are presented with

a text-based menu that offers lists of configuration questions, such as

whether you want kernel math emulation. One of these queries asks you

whether you want TCP/IP networking support. You must answer this with

y to get a kernel capable of networking.

After the general option section is complete, the configuration will

go on to ask whether you want to include support for various features,

such as SCSI drivers or sound cards. The prompt will indicate what

options are available. You can press ? to obtain a

description of what the option is actually offering. You’ll always

have the option of yes (y) to statically include the

component in the kernel, or no (n) to exclude the

component completely. You’ll also see the module (m)

option for those components that may be compiled as a run-time

loadable module. Modules need to be loaded before they can be used,

and are useful for drivers of components that you use infrequently.

The subsequent list of questions deal with networking support. The exact set of configuration options is in constant flux due to ongoing development. A typical list of options offered by most kernel versions around 2.0 and 2.1 looks like this:

* * Network device support * Network device support (CONFIG_NETDEVICES) [Y/n/?]

You must answer this question with y if you want to

use any type of networking devices, whether

they are Ethernet, SLIP, PPP, or whatever. When you answer the

question with y, support for Ethernet-type devices

is enabled automatically. You must answer additional questions if

you want to enable support for other types of network drivers:

PLIP (parallel port) support (CONFIG_PLIP) [N/y/m/?] y PPP (point-to-point) support (CONFIG_PPP) [N/y/m/?] y * * CCP compressors for PPP are only built as modules. * SLIP (serial line) support (CONFIG_SLIP) [N/y/m/?] m CSLIP compressed headers (CONFIG_SLIP_COMPRESSED) [N/y/?] (NEW) y Keepalive and linefill (CONFIG_SLIP_SMART) [N/y/?] (NEW) y Six bit SLIP encapsulation (CONFIG_SLIP_MODE_SLIP6) [N/y/?] (NEW) y

These questions concern the various link layer protocols that Linux supports. Both PPP and SLIP allow you to transport IP datagrams across serial lines. PPP is actually a suite of protocols used to send network traffic across serial lines. Some of the protocols that form PPP manage the way that you authenticate yourself to the dial-in server, while others manage the way certain protocols are carried across the link—PPP is not limited to carrying TCP/IP datagrams; it may also carry other protocol such as IPX.

If you answer y or m to SLIP

support, you will be prompted to answer the three questions that appear

below it. The compressed header option provides support for CSLIP, a

technique that compresses TCP/IP headers to as little as three bytes. Note

that this kernel option does not turn on CSLIP automatically; it merely

provides the necessary kernel functions for it. The Keepalive and linefill option causes the SLIP support to periodically generate

activity on the SLIP line to avoid it being dropped by an inactivity timer. The

Six bit SLIP encapsulation option allows you to run

SLIP over lines and circuits that are not capable of transmitting the

whole 8-bit data set cleanly. This is similar to the uuencoding or binhex

technique used to send binary files by electronic mail.

PLIP provides a way to send IP datagrams across a parallel port connection. It is mostly used to communicate with PCs running DOS. On typical PC hardware, PLIP can be faster than PPP or SLIP, but it requires much more CPU overhead to perform, so while the transfer rate might be good, other tasks on the machine may be slow.

The following questions address network cards from various vendors. As more drivers are being developed, you are likely to see questions added to this section. If you want to build a kernel you can use on a number of different machines, or if your machine has more than one type of network card installed, you can enable more than one driver:

.

.

Ethernet (10 or 100Mbit) (CONFIG_NET_ETHERNET) [Y/n/?]

3COM cards (CONFIG_NET_VENDOR_3COM) [Y/n/?]

3c501 support (CONFIG_EL1) [N/y/m/?]

3c503 support (CONFIG_EL2) [N/y/m/?]

3c509/3c579 support (CONFIG_EL3) [Y/m/n/?]

3c590/3c900 series (592/595/597/900/905) "Vortex/Boomerang" support/

(CONFIG_VORTEX) [N/y/m/?]

AMD LANCE and PCnet (AT1500 and NE2100) support (CONFIG_LANCE) [N/y/?]

AMD PCInet32 (VLB and PCI) support (CONFIG_LANCE32) [N/y/?] (NEW)

Western Digital/SMC cards (CONFIG_NET_VENDOR_SMC) [N/y/?]

WD80*3 support (CONFIG_WD80x3) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

SMC Ultra support (CONFIG_ULTRA) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

SMC Ultra32 support (CONFIG_ULTRA32) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

SMC 9194 support (CONFIG_SMC9194) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

Other ISA cards (CONFIG_NET_ISA) [N/y/?]

Cabletron E21xx support (CONFIG_E2100) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

DEPCA, DE10x, DE200, DE201, DE202, DE422 support (CONFIG_DEPCA) [N/y/m/?]/

(NEW)

EtherWORKS 3 (DE203, DE204, DE205) support (CONFIG_EWRK3) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

EtherExpress 16 support (CONFIG_EEXPRESS) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

HP PCLAN+ (27247B and 27252A) support (CONFIG_HPLAN_PLUS) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

HP PCLAN (27245 and other 27xxx series) support (CONFIG_HPLAN) [N/y/m/?]/

(NEW)

HP 10/100VG PCLAN (ISA, EISA, PCI) support (CONFIG_HP100) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

NE2000/NE1000 support (CONFIG_NE2000) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

SK_G16 support (CONFIG_SK_G16) [N/y/?] (NEW)

EISA, VLB, PCI and on card controllers (CONFIG_NET_EISA) [N/y/?]

Apricot Xen-II on card ethernet (CONFIG_APRICOT) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

Intel EtherExpress/Pro 100B support (CONFIG_EEXPRESS_PRO100B) [N/y/m/?]/

(NEW)

DE425, DE434, DE435, DE450, DE500 support (CONFIG_DE4X5) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

DECchip Tulip (dc21x4x) PCI support (CONFIG_DEC_ELCP) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

Digi Intl. RightSwitch SE-X support (CONFIG_DGRS) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

Pocket and portable adaptors (CONFIG_NET_POCKET) [N/y/?]

AT-LAN-TEC/RealTek pocket adaptor support (CONFIG_ATP) [N/y/?] (NEW)

D-Link DE600 pocket adaptor support (CONFIG_DE600) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

D-Link DE620 pocket adaptor support (CONFIG_DE620) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

Token Ring driver support (CONFIG_TR) [N/y/?]

IBM Tropic chipset based adaptor support (CONFIG_IBMTR) [N/y/m/?] (NEW)

FDDI driver support (CONFIG_FDDI) [N/y/?]

Digital DEFEA and DEFPA adapter support (CONFIG_DEFXX) [N/y/?] (NEW)

ARCnet support (CONFIG_ARCNET) [N/y/m/?]

Enable arc0e (ARCnet "Ether-Encap" packet format) (CONFIG_ARCNET_ETH)/

[N/y/?] (NEW)

Enable arc0s (ARCnet RFC1051 packet format) (CONFIG_ARCNET_1051)/

[N/y/?] (NEW)

.

.

Finally, in the file system section, the configuration script will ask you whether you want support for NFS, the networking file system. NFS lets you export file systems to several hosts, which makes the files appear as if they were on an ordinary hard disk attached to the host:

NFS file system support (CONFIG_NFS_FS) [y]

We describe NFS in detail in Chapter 14.

Linux 2.0.0 marked a significant change in Linux Networking. Many features were made a standard part of the Kernel, such as support for IPX. A number of options were also added and made configurable. Many of these options are used only in very special circumstances and we won’t cover them in detail. The Networking HOWTO probably addresses what is not covered here. We’ll list a number of useful options in this section, and explain when you’d want to use each one:

- Basics

To use TCP/IP networking, you must answer this question with

y. If you answer withn, however, you will still be able to compile the kernel with IPX support:

Networking options --->

[*] TCP/IP networking

- Gateways

You have to enable this option if your system acts as a gateway between two networks or between a LAN and a SLIP link, etc. It doesn’t hurt to enable this by default, but you may want to disable it to configure a host as a so-called firewall. Firewalls are hosts that are connected to two or more networks, but don’t route traffic between them. They’re commonly used to provide users with Internet access at minimal risk to the internal network. Users are allowed to log in to the firewall and use Internet services, but the company’s machines are protected from outside attacks because incoming connections can’t cross the firewall (firewalls are covered in detail in Chapter 9):

[*] IP: forwarding/gatewaying

- Virtual hosting

These options together allow to you configure more than one IP address onto an interface. This is sometimes useful if you want to do “virtual hosting,” through which a single machine can be configured to look and act as though it were actually many separate machines, each with its own network personality. We’ll talk more about IP aliasing in a moment:

[*] Network aliasing <*> IP: aliasing support

- Accounting

This option enables you to collect data on the volume of IP traffic leaving and arriving at your machine (we cover this is detail in Chapter 10):

[*] IP: accounting

--- (it is safe to leave these untouched)

[*] IP: PC/TCP compatibility mode

- Diskless booting

This function enables Reverse Address Resolution Protocol (RARP). RARP is used by diskless clients and X terminals to request their IP address when booting. You should enable RARP if you plan to serve this sort of client. A small program called rarp, included with the standard networking utilities, is used to add entries to the kernel RARP table:

<*> IP: Reverse ARP

- MTU

When sending data over TCP, the kernel has to break up the stream into blocks of data to pass to IP. The size of the block is called the Maximum Transmission Unit, or MTU. For hosts that can be reached over a local network such as an Ethernet, it is typical to use an MTU as large as the maximum length of an Ethernet packet—1,500 bytes. When routing IP over a Wide Area Network like the Internet, it is preferable to use smaller-sized datagrams to ensure that they don’t need to be further broken down along the route through a process called IP fragmentation.[19] The kernel is able to automatically determine the smallest MTU of an IP route and to automatically configure a TCP connection to use it. This behavior is on by default. If you answer

yto this option this feature will be disabled.If you do want to use smaller packet sizes for data sent to specific hosts (because, for example, the data goes through a SLIP link), you can do so using the mss option of the route command, which is briefly discussed at the end of this chapter:

[ ] IP: Disable Path MTU Discovery (normally enabled)

- Security feature

The IP protocol supports a feature called Source Routing. Source routing allows you to specify the route a datagram should follow by coding the route into the datagram itself. This was once probably useful before routing protocols such as RIP and OSPF became commonplace. But today it’s considered a security threat because it can provide clever attackers with a way of circumventing certain types of firewall protection by bypassing the routing table of a router. You would normally want to filter out source routed datagrams, so this option is normally enabled:

[*] IP: Drop source routed frames

- Novell support

This option enables support for IPX, the transport protocol Novell Networking uses. Linux will function quite happily as an IPX router and this support is useful in environments where you have Novell fileservers. The NCP filesystem also requires IPX support enabled in your kernel; if you wish to attach to and mount your Novell filesystems you must have this option enabled (we’ll dicuss IPX and the NCP filesystem in Chapter 15):

<*> The IPX protocol

- Amateur radio

These three options select support for the three Amateur Radio protocols supported by Linux: AX.25, NetRom and Rose (we don’t describe them in this book, but they are covered in detail in the AX25 HOWTO):

<*> Amateur Radio AX.25 Level 2 <*> Amateur Radio NET/ROM <*> Amateur Radio X.25 PLP (Rose)Linux supports another driver type: the dummy driver. The following question appears toward the start of the device-driver section:

<*> Dummy net driver support

The dummy driver doesn’t really do much, but it is quite useful on standalone or PPP/SLIP hosts. It is basically a masqueraded loopback interface. On hosts that offer PPP/SLIP but have no other network interface, you want to have an interface that bears your IP address all the time. This is discussed in a little more detail in Section 5.7.7. in Chapter 5. Note that today you can achieve the same result by using the IP alias feature and configuring your IP address as an alias on the loopback interface.

[17] IRQs 2 and 9 are the same because the IBM PC design has two cascaded interrupt processors with eight IRQs each; the secondary processor is connected to IRQ 2 of the primary one.

[18]

People should use development kernels and report bugs if they are

found; this is a very useful thing to do if you have a machine you can use

as a test machine. Instructions on how to report bugs are detailed in

/usr/src/linux/REPORTING-BUGS in the Linux kernel

source.

[19] Remember, the IP protocol can be carried over many different types of network, and not all network types will support packet sizes as large as Ethernet.