You don’t have to have a good memory to remember a time when only large organizations could afford to have a number of computers networked together by a LAN. Today network technology has dropped so much in price that two things have happened. First, LANs are now commonplace, even in many household environments. Certainly many Linux users will have two or more computers connected by some Ethernet. Second, network resources, particularly IP addresses, are now a scarce resource and while they used to be free, they are now being bought and sold.

Most people with a LAN will probably also want an Internet connection that every computer on the LAN can use. The IP routing rules are quite strict in how they deal with this situation. Traditional solutions to this problem would have involved requesting an IP network address, perhaps a class C address for small sites, assigning each host on the LAN an address from this network and using a router to connect the LAN to the Internet.

In a commercialized Internet environment, this is quite an expensive proposition. First, you’d be required to pay for the network address that is assigned to you. Second, you’d probably have to pay your Internet Service Provider for the privilege of having a suitable route to your network put in place so that the rest of the Internet knows how to reach you. This might still be practical for companies, but domestic installations don’t usually justify the cost.

Fortunately, Linux provides an answer to this dilemma. This answer involves a component of a group of advanced networking features called Network Address Translation (NAT). NAT describes the process of modifying the network addresses contained with datagram headers while they are in transit. This might sound odd at first, but we’ll show that it is ideal for solving the problem we’ve just described and many have encountered. IP masquerade is the name given to one type of network address translation that allows all of the hosts on a private network to use the Internet at the price of a single IP address.

IP masquerading allows you to use a private (reserved) IP network address on your LAN and have your Linux-based router perform some clever, real-time translation of IP addresses and ports. When it receives a datagram from a computer on the LAN, it takes note of the type of datagram it is, “TCP,” “UDP,” “ICMP,” etc., and modifies the datagram so that it looks like it was generated by the router machine itself (and remembers that it has done so). It then transmits the datagram onto the Internet with its single connected IP address. When the destination host receives this datagram, it believes the datagram has come from the routing host and sends any reply datagrams back to that address. When the Linux masquerade router receives a datagram from its Internet connection, it looks in its table of established masqueraded connections to see if this datagram actually belongs to a computer on the LAN, and if it does, it reverses the modification it did on the forward path and transmits the datagram to the LAN computer.

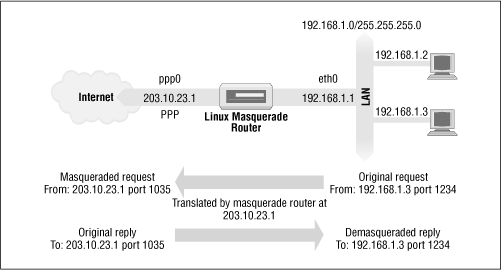

A simple example is illustrated in Figure 11.1.

We have a small Ethernet network using one of the reserved network addresses. The network has a Linux-based masquerade router providing access to the Internet. One of the workstations on the network (192.168.1.3) wishes to establish a connection to the remote host 209.1.106.178 on port 8888. The workstation routes its datagram to the masquerade router, which identifies this connection request as requiring masquerade services. It accepts the datagram and allocates a port number to use (1035), substitutes its own IP address and port number for those of the originating host, and transmits the datagram to the destination host. The destination host believes it has received a connection request from the Linux masquerade host and generates a reply datagram. The masquerade host, upon receiving this datagram, finds the association in its masquerade table and reverses the substution it performed on the outgoing datagram. It then transmits the reply datagram to the originating host.

The local host believes it is speaking directly to the remote host. The remote host knows nothing about the local host at all and believes it has received a connection from the Linux masquerade host. The Linux masquerade host knows these two hosts are speaking to each other, and on what ports, and performs the address and port translations necessary to allow communication.

This might all seem a little confusing, and it can be, but it works and is really quite simple to configure. So don’t worry if you don’t understand all the details yet.

The IP masquerade facility comes with its own set of side effects, some of which are useful and some of which might become bothersome.

None of the hosts on the supported network behind the masquerade router are ever directly seen; consequently, you need only one valid and routable IP address to allow all hosts to make network connections out onto the Internet. This has a downside; none of those hosts are visible from the Internet and you can’t directly connect to them from the Internet; the only host visible on a masqueraded network is the masquerade machine itself. This is important when you consider services such as mail or FTP. It helps determine what services should be provided by the masquerade host and what services it should proxy or otherwise treat specially.

Second, because none of the masqueraded hosts are visible, they are relatively protected from attacks from outside; this could simplify or even remove the need for firewall configuration on the masquerade host. You shouldn’t rely too heavily on this, though. Your whole network will be only as safe as your masquerade host, so you should use firewall to protect it if security is a concern.

Third, IP masquerade will have some impact on the performance of your networking. In typical configurations this will probably be barely measurable. If you have large numbers of active masquerade sessions, though, you may find that the processing required at the masquerade machine begins to impact your network throughput. IP masquerade must do a good deal of work for each datagram compared to the process of conventional routing. That 386SX16 machine you have been planning on using as a masquerade machine supporting a dial-up link to the Internet might be fine, but don’t expect too much if you decide you want to use it as a router in your corporate network at Ethernet speeds.

Last, some network services just won’t work through masquerade, or at least not without a lot of help. Typically, these are services that rely on incoming sessions to work, such as some types of Direct Communications Channels (DCC), features in IRC, or certain types of video and audio multicasting services. Some of these services have specially developed kernel modules to provide solutions for these, and we’ll talk about those in a moment. For others, it is possible that you will find no support, so be aware,it won’t be suitable in all situations.