Network administration tasks fall into two very different categories: configuration and troubleshooting. Configuration tasks prepare for the expected; they require detailed knowledge of command syntax, but are usually simple and predictable. Once a system is properly configured, there is rarely any reason to change it. The configuration process is repeated each time a new operating system release is installed, but with very few changes.

In contrast, network troubleshooting deals with the unexpected. Troubleshooting frequently requires knowledge that is conceptual rather than detailed. Network problems are usually unique and sometimes difficult to resolve. Troubleshooting is an important part of maintaining a stable, reliable network service.

In this chapter, we discuss the tools you will use to ensure that the network is in good running condition. However, good tools are not enough. No troubleshooting tool is effective if applied haphazardly. Effective troubleshooting requires a methodical approach to the problem, and a basic understanding of how the network works. We’ll start our discussion by looking at ways to approach a network problem.

To approach a problem properly, you need a basic understanding of TCP/IP. The first few chapters of this book discuss the basics of TCP/IP and provide enough background information to troubleshoot most network problems. Knowledge of how TCP/IP routes data through the network, between individual hosts, and between the layers in the protocol stack is important for understanding a network problem. But detailed knowledge of each protocol usually isn’t necessary. When you need these details, look them up in a definitive reference—don’t try to recall them from memory.

Not all TCP/IP problems are alike, and not all problems can be approached in the same manner. But the key to solving any problem is understanding what the problem is. This is not as easy as it may seem. The “surface” problem is sometimes misleading, and the “real” problem is frequently obscured by many layers of software. Once you understand the true nature of the problem, the solution to the problem is often obvious.

First, gather detailed information about exactly what’s happening. When a user reports a problem, talk to her. Find out which application failed. What is the remote host’s name and IP address? What is the user’s hostname and address? What error message was displayed? If possible, verify the problem by having the user run the application while you talk her through it. If possible, duplicate the problem on your own system.

Testing from the user’s system, and other systems, find out:

Does the problem occur in other applications on the user’s host, or is only one application having trouble? If only one application is involved, the application may be misconfigured or disabled on the remote host. Because of security concerns, many systems disable some services.

Does the problem occur with only one remote host, all remote hosts, or only certain “groups” of remote hosts? If only one remote host is involved, the problem could easily be with that host. If all remote hosts are involved, the problem is probably with the user’s system (particularly if no other hosts on your local network are experiencing the same problem). If only hosts on certain subnets or external networks are involved, the problem may be related to routing.

Does the problem occur on other local systems? Make sure you check other systems on the same subnet. If the problem occurs only on the user’s host, concentrate testing on that system. If the problem affects every system on a subnet, concentrate on the router for that subnet.

Once you know the symptoms of the problem, visualize each protocol and device that handles the data. Visualizing the problem will help you avoid oversimplification, and keep you from assuming that you know the cause even before you start testing. Using your TCP/IP knowledge, narrow your attack to the most likely causes of the problem, but keep an open mind.

Below are several useful troubleshooting hints. They are not part of a troubleshooting methodology—just good ideas to keep in mind.

Approach problems methodically. Allow the information gathered from each test to guide your testing. Don’t jump on a hunch into another test scenario without ensuring that you can pick up your original scenario where you left off.

Work carefully through the problem, dividing it into manageable pieces. Test each piece before moving on to the next. For example, when testing a network connection, test each part of the network until you find the problem.

Keep good records of the tests you have completed and their results. Keep a historical record of the problem in case it reappears.

Keep an open mind. Don’t assume too much about the cause of the problem. Some people believe their network is always at fault, while others assume the remote end is always the problem. Some are so sure they know the cause of a problem that they ignore the evidence of the tests. Don’t fall into these traps. Test each possibility and base your actions on the evidence of the tests.

Be aware of security barriers. Security firewalls sometimes block

ping,traceroute, and even ICMP error messages. If problems seem to cluster around a specific remote site, find out if it has a firewall.Pay attention to error messages. Error messages are often vague, but they frequently contain important hints for solving the problem.

Duplicate the reported problem yourself. Don’t rely too heavily on the user’s problem report. The user has probably seen this problem only from the application level. If necessary, obtain the user’s data files to duplicate the problem. Even if you cannot duplicate the problem, log the details of the reported problem for your records.

Most problems are caused by human error. You can prevent some of these errors by providing information and training on network configuration and usage.

Keep your users informed. This reduces the number of duplicated trouble reports and the duplication of effort when several system administrators work on the same problem without knowing others are already working on it. If you’re lucky, someone may have seen the problem before and have a helpful suggestion about how to resolve it.

Don’t speculate about the cause of the problem while talking to the user. Save your speculations for discussions with your networking colleagues. Your speculations may be accepted by the user as gospel, and become rumors. These rumors can cause users to avoid using legitimate network services and may undermine confidence in your network. Users want solutions to their problems; they’re not interested in speculative techno-babble.

Stick to a few simple troubleshooting tools. For most TCP/IP software problems, the tools discussed in this chapter are sufficient. Just learning how to use a new tool is often more time-consuming than solving the problem with an old, familiar tool.

Thoroughly test the problem at your end of the network before locating the owners of the remote system to coordinate testing with them. The greatest difficulty of network troubleshooting is that you do not always control the systems at both ends of the network. In many cases, you may not even know who does control the remote system. The more information you have about your end, the simpler the job will be when you have to contact the remote administrator.

Don’t neglect the obvious. A loose or damaged cable is always a possible problem. Check plugs, connectors, cables, and switches. Small things can cause big problems.

Because most problems have simple causes, developing a clear idea of the problem often provides the solution. Unfortunately, this is not always true, so in this section we begin to discuss the tools that can help you attack the most intractable problems. Many diagnostic tools are available, ranging from commercial systems with specialized hardware and software that may cost thousands of dollars, to free software that is available from the Internet. Many software tools are provided with your Unix system. You should also keep some hardware tools handy.

To maintain the network’s equipment and wiring, you need some simple hand tools. A pair of needle-nose pliers and a few screwdrivers may be sufficient, but you may also need specialized tools. For example, attaching RJ45 connectors to unshielded twisted pair (UTP) cable requires special crimping tools. It is usually easiest to buy a ready-made network maintenance toolkit from your cable vendor.

A full-featured cable tester is also useful. Modern cable testers are small hand-held units with a keypad and LCD display that test both thinnet and UTP cable. Tests are selected from the keyboard and results are displayed on the LCD screen. It is not necessary to interpret the results because the unit does that for you and displays the error condition in a simple text message. For example, a cable test might produce the message “Short at 74 feet.” This tells you that the cable is shorted 74 feet away from the tester. What could be simpler? The proper test tools make it easier to locate, and therefore fix, cable problems.

A laptop computer can be a most useful piece of test

equipment when properly configured. Install TCP/IP software on the

laptop. Take it to the location where the user reports a network

problem. Disconnect the Ethernet cable from the back of the user’s

system and attach it to the laptop. Configure the laptop with an

appropriate address for the user’s subnet and reboot it. Then ping various systems on the network and attach

to one of the user’s servers. If everything works, the fault is probably

in the user’s computer. Users trust this test because it demonstrates

something they do every day. They have more confidence in the laptop

than in an unidentifiable piece of test equipment displaying the message

“No faults found.” If the test fails, the fault is probably in the

network equipment or wiring. That’s the time to bring out the cable

tester.

Another advantage of using a laptop as a piece of test equipment is its inherent versatility. It runs a wide variety of test, diagnostic, and management software. Install Unix on the laptop and run the software discussed in the rest of this chapter from your desktop or your laptop.

This book emphasizes free or “built-in” software diagnostic tools that run on Unix systems. The software tools used in this chapter, and many more, are described in RFC 1470, FYI on a Network Management Tool Catalog: Tools for Monitoring and Debugging TCP/IP Internets and Interconnected Devices. A catchy title, and a useful RFC! The RFC is somewhat dated, but it does point out some very useful tools. The tools listed in that catalog and discussed in this book are:

- ifconfig

Provides information about the basic configuration of the interface. It is useful for detecting bad IP addresses, incorrect subnet masks, and improper broadcast addresses. Chapter 6 covers

ifconfigin detail. This tool is provided with the Unix operating system.- arp

Provides information about Ethernet/IP address translation. It can be used to detect systems on the local network that are configured with the wrong IP address.

arpis covered in this chapter and is used in an example in Chapter 2.arpis delivered as part of Unix.- netstat

Provides a variety of information. It is commonly used to display detailed statistics about each network interface, the network sockets, and the network routing table.

netstatis used repeatedly in this book, most extensively in Chapters Chapter 2, Chapter 6, and Chapter 7.netstatis delivered as part of Unix.- ping

Indicates whether a remote host can be reached.

pingalso displays statistics about packet loss and delivery time.pingis discussed in Chapter 1 and used in Chapter 7.pingalso comes as part of Unix.- nslookup

Provides information about the DNS name service.

nslookupis covered in detail in Chapter 8. It comes as part of the BIND software package.- dig

Also provides information about name service and is similar to

nslookup.- traceroute

Prints information about each routing hop that packets take going from your system to a remote system.

- snoop

Analyzes the individual packets exchanged between hosts on a network.

snoopis a TCP/IP protocol analyzer included with Solaris 8 systems. It examines the contents of packets, including their headers, and is most useful for analyzing protocol problems.tcpdumpis a tool similar tosnoopthat is provided with Linux systems.

This chapter discusses each of these tools, even those covered

earlier in the text. We start with ping, which is used in more troubleshooting

situations than any other diagnostic tool.

The ping command tests whether a remote host can be reached from your

computer. This simple function is extremely useful for testing the

network connection, independent of the application in which the original

problem was detected. ping allows you

to determine whether further testing should be directed toward the

network connection (the lower layers) or the application (the upper

layers). If ping shows that packets

can travel to the remote system and back, the user’s problem is probably

in the upper layers. If packets can’t make the round trip, lower

protocol layers are probably at fault.

Frequently a user reports a network problem by stating that he

can’t telnet (or ftp, or send email, or whatever) to some

remote host. He then immediately qualifies this statement with the

announcement that it worked before. In cases like this, where the

ability to connect to the remote host is in question, ping is a very useful tool.

Using the hostname provided by the user, ping the remote host. If your ping is successful, have the user ping the host. If the user’s ping is also successful, concentrate your

further analysis on the specific application that the user is having

trouble with. Perhaps the user is attempting to telnet to a host that provides only anonymous

ftp. Perhaps the host was down when

the user tried his application. Have the user try it again, while you

watch or listen to every detail of what he is doing. If he is doing

everything right and the application still fails, detailed analysis of

the application with snoop and

coordination with the remote system administrator may be needed.

If your ping is successful and

the user’s ping fails, concentrate

testing on the user’s system configuration, and on those things that are

different about the user’s path to the remote host when compared to your

path to the remote host.

If your ping fails, or the

user’s ping fails, pay close

attention to any error messages. The error messages displayed by

ping are helpful guides for planning

further testing. The details of the messages may vary from

implementation to implementation, but there are only a few basic types

of errors:

- Unknown host

The remote host’s name cannot be resolved by name service into an IP address. The name servers could be at fault (either your local server or the remote system’s server), the name could be incorrect, or something could be wrong with the network between your system and the remote server. If you know the remote host’s IP address, try to

pingthat. If you can reach the host using its IP address, the problem is with name service. Usenslookupordigto test the local and remote servers, and to check the accuracy of the hostname the user gave you.- Network unreachable

The local system does not have a route to the remote system. If the numeric IP address was used on the

pingcommand line, re-enter thepingcommand using the hostname. This eliminates the possibility that the IP address was entered incorrectly, or that you were given the wrong address. If a routing protocol is being used, make sure it is running and check the routing table withnetstat. If a static default route is being used, reinstall it. If everything seems fine on the host, check its default gateway for routing problems.- No answer

The remote system did not respond. Most network utilities have some version of this message. Some

pingimplementations print the message “100% packet loss.”telnetprints the message “Connection timed out” andsendmailreturns the error “cannot connect.” All of these errors mean the same thing. The local system has a route to the remote system, but it receives no response from the remote system to any of the packets it sends.There are many possible causes of this problem. The remote host may be down. Either the local or the remote host may be configured incorrectly. A gateway or circuit between the local host and the remote host may be down. The remote host may have routing problems. Only additional testing can isolate the cause of the problem. Carefully check the local configuration using

netstatandifconfig. Check the route to the remote system withtraceroute. Contact the administrator of the remote system and report the problem.

All of the tools mentioned here will be discussed later in this

chapter. However, before leaving ping, let’s look more closely at the command

and the statistics it displays.

The basic format of the ping

command on a Solaris system is:[141]

pinghost[packetsize] [count]

hostThe hostname or IP address of the remote host being tested. Use the hostname or address provided by the user in the trouble report.

packetsizeDefines the size in bytes of the test packets. This field is required only if the

countfield is going to be used. Use the defaultpacketsizeof 56 bytes.countThe number of packets to be sent in the test. Use the

countfield, and set the value low. Otherwise, thepingcommand may continue to send test packets until you interrupt it, usually by pressing Ctrl-C (^C). Sending excessive numbers of test packets is not a good use of network bandwidth and system resources. Usually five packets are sufficient for a test.

To check that ns.uu.net can be reached from crab, we send five 56-byte packets with the following command:

% ping -s ns.uu.net 56 5

PING ns.uu.net: 56 data bytes

64 bytes from ns.uu.net (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=0. time=32.8 ms

64 bytes from ns.uu.net (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=1. time=15.3 ms

64 bytes from ns.uu.net (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=2. time=13.1 ms

64 bytes from ns.uu.net (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=3. time=32.4 ms

64 bytes from ns.uu.net (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=4. time=28.1 ms

----ns.uu.net PING Statistics----

5 packets transmitted, 5 packets received, 0% packet loss

round trip (ms) min/avg/max = 13.1/24.3/32.8The -s option is included

because crab is a Solaris workstation, and we want packet-by-packet

statistics. Without the -s option,

Sun’s ping command prints only a

summary line saying “ns.uu.net is alive.” Other ping implementations do not require the

-s option; they display the

statistics by default, as the Linux example below shows:

$ ping -c5 ns.uu.net

PING ns.uu.net (137.39.1.3) from 172.16.12.3 : 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from ns.UU.NET (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=0 ttl=244 time=98.283 msec

64 bytes from ns.UU.NET (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=1 ttl=244 time=94.114 msec

64 bytes from ns.UU.NET (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=2 ttl=244 time=66.565 msec

64 bytes from ns.UU.NET (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=3 ttl=244 time=24.301 msec

64 bytes from ns.UU.NET (137.39.1.3): icmp_seq=4 ttl=244 time=37.060 msec

--- ns.uu.net ping statistics ---

5 packets transmitted, 5 packets received, 0% packet loss

round trip min/avg/max/mdev = 24.301/64.064/98.283/29.634 msBoth tests show a good wide area network link to

ns.uu.net with no packet loss and a fast

response. The round trip between almond and

ns.uu.net took an average of only 24.3

milliseconds. A small packet loss, and a round trip time an order of

magnitude higher, would not be abnormal for a connection made across a

wide area network. The statistics displayed by the ping command can indicate low-level network

problems. The key statistics are:

The sequence in which the packets are arriving, as shown by the ICMP sequence number (

icmp_seq) displayed for each packet.How long it takes a packet to make the round trip, displayed in milliseconds after the string

time=.The percentage of packets lost, displayed in a summary line at the end of the

pingoutput.

If the packet loss is high, the response time is very slow, or packets are arriving out of order, there could be a network hardware problem. If you see these conditions when communicating over great distances on a wide area network, there is nothing to worry about. TCP/IP was designed to deal with unreliable networks, and some wide area networks suffer a lot of packet loss. But if these problems are seen on a local area network, they indicate trouble.

On a local network cable segment, the round trip time should be near 0, there should be little or no packet loss, and the packets should arrive in order. If these things are not true, there is a problem with the network hardware. On an Ethernet, the problem could be improper cable termination, a bad cable segment, or a bad piece of “active” hardware, such as a hub, switch, or transceiver. Check the cable with a cable tester as described earlier. Good hubs and switches often have built-in diagnostic software that can be checked. Cheap hubs and transceivers may require the “brute force” method of disconnecting individual pieces of hardware until the problem goes away.

The results of a simple ping

test, even if the ping is

successful, can help you direct further testing toward the most likely

causes of the problem. But other diagnostic tools are needed to

examine the problem more closely and find the underlying cause.

The “no answer” and “cannot connect” errors indicate a problem in

the lower layers of the network protocols. If the preliminary tests

point to this type of problem, concentrate your testing on routing and

on the network interface. Use the ifconfig, netstat, and arp commands to test the Network Access

Layer.

ifconfig checks the network interface configuration. Use this command to

verify the user’s configuration if the user’s system has been recently

configured or if the user’s system cannot reach the remote host while

other systems on the same network can.

When ifconfig is entered with

an interface name and no other arguments, it displays the current

values assigned to that interface. For example, checking interface

dnet0 on a Solaris 8 system gives this report:

% ifconfig dnet0

dnet0: flags=1000843<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,MULTICAST,IPv4> mtu 1500 index 2

inet 172.16.55.105 netmask ffffff00 broadcast 172.16.55.255The ifconfig command displays

two lines of output. The first line of the display shows the

interface’s name and its characteristics. Check for these

characteristics:

- UP

The interface is enabled for use. If the interface is “down,” have the system’s superuser bring the interface “up” with the

ifconfigcommand (e.g.,ifconfig dnet0 up). If the interface won’t come up, replace the interface cable and try again. If it still fails, have the interface hardware checked.- RUNNING

This interface is operational. If the interface is not “running,” the driver for this interface may not be properly installed. The system administrator should review all of the steps necessary to install this interface, looking for errors or missed steps.

The second line of ifconfig

output shows the IP address, the subnet mask (written in hexadecimal),

and the broadcast address. Check these three fields to make sure the

network interface is properly configured.

Two common interface configuration problems are misconfigured

subnet masks and incorrect IP addresses. A bad subnet mask is

indicated when the host can reach other hosts on its local subnet and

remote hosts on distant networks, but it cannot reach hosts on other

local subnets. ifconfig quickly

reveals if a bad subnet mask is set.

An incorrectly set IP address can be a subtle problem. If the

network part of the address is incorrect, every ping will fail with the “no answer” error.

In this case, using ifconfig will

reveal the incorrect address. However, if the host part of the address

is wrong, the problem can be more difficult to detect. A small system,

such as a PC that only connects out to other systems and never accepts

incoming connections, can run for a long time with the wrong address

without its user noticing the problem. Additionally, the system that

suffers the ill effects may not be the one that is misconfigured. It

is possible for someone to accidentally use your IP address on his

system, and for his mistake to cause your system intermittent

communications problems. An example of this problem is discussed

later. This type of configuration error cannot be discovered by

ifconfig because the error is on a

remote host. The arp command is

used for this type of problem.

The arp command is used to analyze problems with IP-to-Ethernet address

translation. The arp command has

three useful options for troubleshooting:

-aDisplay all ARP entries in the table.

-dhostnameDelete an entry from the ARP table.

-shostname ether-addressAdd a new entry to the table.

With these three options you can view the contents of the ARP table, delete a problem entry, and install a corrected entry. The ability to install a corrected entry is useful in “buying time” while you look for the permanent fix.

Use arp if you suspect that

incorrect entries are getting into the address resolution table. One

clear indication of problems with the ARP table is a report that the

“wrong” host responded to some command, like ftp or telnet. Intermittent problems that affect

only certain hosts can also indicate that the ARP table has been

corrupted. ARP table problems are usually caused by two systems using

the same IP address. The problems appear intermittent because the

entry that appears in the table is the address of the host that

responded quickest to the last ARP request. Sometimes the “correct”

host responds first, and sometimes the “wrong” host responds

first.

If you suspect that two systems are using the same IP address,

display the address resolution table with the arp -a command. Here’s an example from a

Solaris system:[142]

% arp -a

Net to Media Table: IPv4

Device IP Address Mask Flags Phys Addr

------ -------------------- --------------- ----- ---------------

dnet0 pecan 255.255.255.255 08:00:20:05:21:33

dnet0 horseshoe 255.255.255.255 00:00:0c:e0:80:b1

dnet0 crab 255.255.255.255 SP 08:00:20:22:fd:51

dnet0 BASE-ADDRESS.MCAST.NET 240.0.0.0 SM 01:00:5e:00:00:00It is easiest to verify that the IP and Ethernet address pairs are correct if you have a record of each host’s correct Ethernet address. For this reason you should record each host’s Ethernet and IP address when it is added to your network. If you have such a record, you’ll quickly see if anything is wrong with the table.

If you don’t have this type of record, the first three bytes of the Ethernet address can help you to detect a problem. The first three bytes of the address identify the equipment manufacturer. A list of these identifying prefixes is found at http://www.iana.org/assignments/ethernet-numbers.

From the vendor prefixes we see that two of the ARP entries displayed in our example are Sun systems (8:0:20). If horseshoe is also supposed to be a Sun, the 0:0:0c Cisco prefix indicates that a Cisco router has been mistakenly configured with horseshoe’s IP address.

If neither checking a record of correct assignments nor checking

the manufacturer prefix helps you identify the source of the errant

ARP, try using telnet to connect to

the IP address shown in the ARP entry. If the device supports telnet, the login banner might help you

identify the incorrectly configured host.

A user called in asking if the server was down, and reported the following problem. The user’s workstation, called limulus, appeared to “lock up” for minutes at a time when certain commands were used, while other commands worked with no problems. The network commands that involved the NIS name server all caused the lock-up problem, but some unrelated commands also caused the problem. The user reported seeing the error message:

NFS getattr failed for server crab: RPC: Timed out

The server crab was providing

limulus with NIS and NFS services. The commands

that failed on limulus were commands that

required NIS service, or that were stored in the centrally

maintained /usr/local directory exported from

crab. The commands that ran correctly were

installed locally on the user’s workstation. No one else reported a

problem with the server, and we were able to ping limulus from

crab and get good responses.

We had the user check the messages file[143] for recent error messages, and she discovered this:

Mar 6 13:38:23 limulus vmunix: duplicate IP address!!

sent from ethernet address: 0:0:c0:4:38:1aThis message indicates that the workstation detected another host on the Ethernet responding to its IP address. The “imposter” used the Ethernet address 0:0:c0:4:38:1a in its ARP response. The correct Ethernet address for limulus is 8:0:20:e:12:37.

We checked crab’s ARP table and found

that it had the incorrect ARP entry for

limulus. We deleted the bad

limulus entry with the arp -d command, and installed the correct

entry with the -s option, as

shown below:

# arp -d limulus limulus (172.16.180.130) deleted # arp -s limulus 8:0:20:e:12:37

ARP entries received via the ARP protocol are temporary. The values are held in the table for a finite lifetime and are deleted when that lifetime expires. New values are then obtained via the ARP protocol. Therefore, if some remote interfaces change, the local table adjusts and communications continue. Usually this is a good idea, but if someone is using the wrong IP address, that bad address can keep reappearing in the ARP table even if it is deleted. However, manually entered values are permanent; they stay in the table and can only be deleted manually. This allowed us to install a correct entry in the table without worrying about it being overwritten by a bad address.

This quick fix resolved limulus’s immediate problem, but we still needed to find the culprit. We checked the /etc/ethers file to see if we had an entry for Ethernet address 0:0:c0:4:38:1a, but we didn’t. From the first three bytes of this address, 0:0:c0, we knew that the device was a Western Digital card. Since our network has only Unix workstations and PCs, we assumed the Western Digital card was installed in a PC. We also guessed that the problem address was recently installed because the user had never had the problem before. We sent out an urgent announcement to all users asking if anyone had recently installed a new PC, reconfigured a PC, or installed TCP/IP software on a PC. We got one response. When we checked his system, we found out that he had entered the address 172.16.180.130 when he should have entered 172.16.180.138. The address was corrected and the problem did not recur.

Nothing fancy was needed to solve this problem. Once we checked the error messages, we knew what the problem was and how to solve it. Involving the entire network user community allowed us to quickly locate the problem system and to avoid a room-to-room search for the PC. Reluctance to involve users and make them part of the solution is one of the costliest, and most common, mistakes made by network administrators.

If the preliminary tests lead you to suspect that the connection to the

local area network is unreliable, the netstat -i command can provide useful information. The example below

shows the output from the netstat -i command on a Solaris 8 system:[144]

% netstat -i

Name Mtu Net/Dest Address Ipkts Ierrs Opkts Oerrs Collis Queue

dnet0 1500 wrotethebook.com crab 442697 2 633424 2 50679 0

lo0 1536 loopback localhost 53040 0 53040 0 0 0The line for the loopback interface, lo0, can be ignored. Only the line for the real network interface is significant, and only the last five fields on that line provide significant troubleshooting information.

Let’s look at the last field first. There should be no packets queued (Queue) that cannot be transmitted. If the interface is up and running, and the system cannot deliver packets to the network, suspect a bad drop cable or a bad interface. Replace the cable and see if the problem goes away. If it doesn’t, call the vendor for interface hardware repairs.

The input errors (Ierrs) and the output errors (Oerrs) should be

close to 0. Regardless of how much traffic has passed through this

interface, 100 errors in either of these fields is high. High output

errors could indicate a saturated local network or a bad physical

connection between the host and the network. High input errors could

indicate that the network is saturated, the local host is overloaded,

or there is a physical network problem. Tools, such as ping statistics or a cable tester, can help

you determine if it is a physical network problem. Evaluating the

collision rate can help you determine if the local Ethernet is

saturated.

A high value in the collision field (Collis) is normal, but if the percentage of output packets that result in a collision is too high, it indicates that the network is saturated. Collision rates greater than 5% bear watching. If high collision rates are seen consistently, and are seen among a broad sampling of systems on the network, you may need to subdivide the network to reduce traffic load.

Collision rates are a percentage of output packets. Don’t use

the total number of packets sent and received; use the values in the

Opkts and Collis fields when determining the collision rate. For

example, the output in the netstat

example shows 50679 collisions out of 633424 outgoing packets. That’s

a collision rate of 8%. This sample network could be overworked; check

the statistics on other hosts on this network. If the other systems

also show a high collision rate, consider subdividing this

network.

To reduce the collision rate, you must reduce the amount of traffic on the network segment. A simple way to do this is to create multiple segments out of the single segment. Each new segment will have fewer hosts and, therefore, less traffic. We’ll see, however, that it’s not quite this simple.

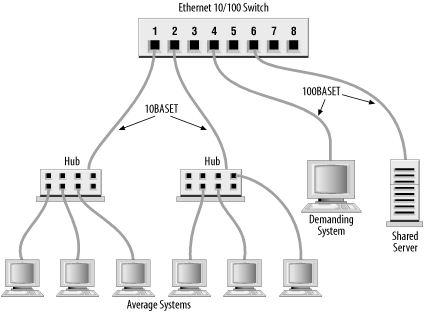

The most effective way to subdivide an Ethernet is to install an Ethernet switch. Each port on the switch is essentially a separate Ethernet. So a 16-port switch gives you 16 Ethernets to work with when balancing the load. On most switches the ports can be used in a variety of ways (see Figure 13-1). Lightly used systems can be attached to a hub that is then attached to one of the switch ports to allow the systems to share a single segment. Servers and demanding systems can be given dedicated ports so that they don’t need to share a segment with anyone. Most switches provide both 10 Mbps Ethernet and Fast Ethernet 100 Mbps ports. These are called asymmetric switches because different ports operate at different speeds. Use the Fast Ethernet ports to connect heavily used servers or segments. Most 10/100 switches have auto-sensing ports. This allows every port to be used at either 100 Mbps or at 10 Mbps, which gives you the maximum configuration flexibility.

Gigabit Ethernet switches can also be used, but they have a unique place in the network topology. 10/100 switches connect servers and local networks. Gigabit switches are primarily used to create a “collapsed backbone” to interconnect other switches. Gigabit switches are used when designing a new corporate backbone network. 10/100 switches are used when subdividing an individual Ethernet segment.

Figure 13-1 shows an 8-port 10/100 Ethernet switch. Ports 1 and 2 are wired to Ethernet hubs. A few systems are connected to each hub. When new systems are added they are distributed evenly among the hubs to prevent any one segment from becoming overloaded. Additional hubs can be added to the available switch ports for future expansion. Port 4 attaches a demanding system with its own private segment. Port 6 operates at 100 Mbps and attaches a heavily used server. A port can be reserved for a future 100 Mbps connection to a second 10/100 Ethernet switch for even more expansion.

Before allocating the ports on your switch, evaluate what services are in demand, and who talks to whom. Then develop a plan that reduces the amount of traffic flowing over any segment. For example, if the demanding system on Port 4 uses lots of bandwidth because it is constantly talking to one of the systems on Port 1, all of the systems on Port 1 will suffer because of this traffic. The computer that the demanding system communicates with should be moved to one of the vacant ports or to the same port (4) as the demanding system. Use your switch to the greatest advantage by balancing the load.

Should you segment an old coaxial cable Ethernet by cutting the cable and joining it back together through a router or a bridge? No. If you have an old network that is finally reaching saturation, it is time to install a new network built on a more robust technology. A shared media network, a network where everyone is on the same cable (in this example, a coaxial cable Ethernet) is an accident waiting to happen. Design a network that a user cannot bring down by merely disconnecting his system, or even by accidentally cutting a wire in his office. Use unshielded twisted pair (UTP) cable, ideally Category 5 cable, to create a 10BaseT Ethernet or 100BaseT Fast Ethernet that wires equipment located in the user’s office to a hub securely stored in a wire closet. The network components in the user’s office should be sufficiently isolated from the network so that damage to those components does not damage the entire network. The new network will solve your collision problem and reduce the amount of hardware troubleshooting you are called upon to do.

Some of the tests discussed in this section can show a network hardware problem. If a hardware problem is indicated, contact the people responsible for the hardware. If the problem appears to be in a leased telephone line, contact the telephone company. If the problem appears to be in a wide area network, contact the management of that network. Don’t sit on a problem expecting it to go away. It could easily get worse.

If the problem is in your local area network, you will have to handle it yourself. Some tools, such as the cable tester, can help. But frequently the only way to approach a hardware problem is by brute force—disconnecting pieces of hardware until you find the one causing the problem. It is most convenient to do this at the switch or hub. If you identify a device causing the problem, repair or replace it. Remember that the problem can be the cable itself, rather than any particular device.

The “network unreachable” error message clearly indicates a routing problem. If the

problem is in the local host’s routing table, it is easy to detect and

resolve. First, use netstat -nr and grep to see whether or not a valid route to

your destination is installed in the routing table.[145]

This example checks for a specific route to network 128.8.0.0:

% netstat -nr | grep '^128\.8\.'

128.8.0.0 26.20.0.16 UG 0 37 dnet0This same test, run on a system that did not have this route in

its routing table, would return no response at all. For example, a user

reports that the “network is down” because he cannot ftp to

helios.metalab.unc.edu, and a ping test returns the following

results:

% ping -s helios.metalab.unc.edu 56 2

PING helios.metalab.unc.edu: 56 data bytes

sendto: Network is unreachable

ping: wrote helios.metalab.unc.edu 64 chars, ret=-1

sendto: Network is unreachable

ping: wrote helios.metalab.unc.edu 64 chars, ret=-1

----helios.metalab.unc.edu PING Statistics----

2 packets transmitted, 0 packets received, 100% packet lossBased on the “network unreachable” error message, check the user’s routing table. In our example, we’re looking for a route to helios.metalab.unc.edu. The IP address[146] of helios.metalab.unc.edu is 152.2.210.81. So we check for any route to a destination that begins with 152.2:

% netstat -nr | grep '^152\.2\.'

%This test shows that there is no specific

route to a destination that begins with 152.2. If a route was found,

grep would display it. Since there’s

no specific route to the destination, remember to look for a default

route. This example shows a successful check for a default route on a

Solaris system:[147]

% netstat -nr | grep def

default 172.16.12.1 UG 0 101277 dnet0If netstat shows the correct

specific route or a valid default route, the problem is not in the

routing table. In that case, use traceroute, as described in the next section,

to trace the route all the way to its destination.

If the routing table doesn’t contain the expected route, it’s a

local routing problem. There are two ways to approach local routing

problems, depending on whether the system uses static or dynamic

routing. If you’re using static routing, install the missing route using

the route add command. Remember, most systems that use

static routing rely on a default route, so the missing route could be

the default route. Make sure that the startup files add the needed route

to the table whenever the system reboots. See Chapter 7 for details about the route add command.

If you’re using dynamic routing, make sure that the routing

program is running. For example, the command below makes sure that

gated is running:

% ps 'cat /etc/gated.pid'

PID TT STAT TIME COMMAND

27711 ? S 304:59 gated -tep /etc/log/gated.logIf the correct routing daemon is not running, restart it and specify tracing. Tracing allows you to check for problems that might be causing the daemon to terminate abnormally.

If the local routing table is correct, the problem may be occurring some

distance away from the local host. Remote routing problems can cause

the “no answer” error message, as well as the “network unreachable”

error message. But the “network unreachable” message does not always

signify a routing problem. It can mean that the remote network cannot

be reached because something is down between the local host and the

remote destination. traceroute is

the program that can help you locate these problems.

traceroute traces the route

of UDP packets from the local host to a remote host. It prints the

name (if it can be determined) and IP address of each gateway along

the route to the remote host.

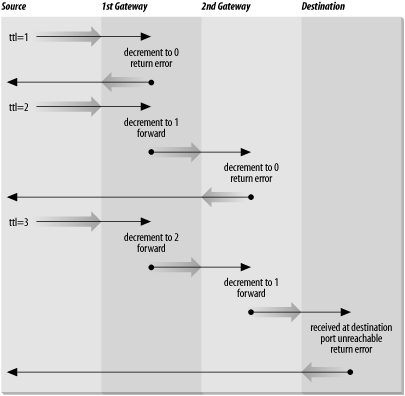

traceroute uses two

techniques, small TTL (time-to-live) values and an invalid port

number, to trace packets to their destination. traceroute sends out UDP packets with small

TTL values to detect the intermediate gateways. The TTL values start

at 1 and increase in increments of 1 for each group of three UDP

packets sent. When a gateway receives a packet, it decrements the TTL.

If the TTL is then 0, the packet is not forwarded and an ICMP “Time

Exceeded” message is returned to the source of the packet. traceroute displays one line of output for

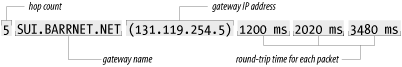

each gateway from which it receives a “Time Exceeded” message. Figure 13-2 presents a sample of

the single line of output that is displayed for a gateway, and shows

the meaning of each field in the line.

When the destination host receives a packet from traceroute, it returns an ICMP “Unreachable Port” message. This happens because traceroute intentionally uses an invalid

port number (33434) to force this error. When traceroute receives the “Unreachable Port”

message, it knows that it has reached the destination host, and it

terminates the trace. So, traceroute is able to develop a list of the

gateways, starting at one hop away and increasing one hop at a time

until the remote host is reached. Figure 13-3 illustrates the flow of

packets tracing to a host three hops away. The following shows a

traceroute to

www.internic.net from a Solaris system hanging

off the Comcast network. traceroute

sends out three packets at each TTL value. If no response is received

to a packet, traceroute prints an

asterisk (*). If a response is

received, traceroute displays the

name and address of the gateway that responded and the packet’s round

trip time in milliseconds.

$ traceroute www.internic.net

traceroute to www.internic.net (207.151.159.3), 30 hops max, 40 byte packets

1 ani (192.168.0.1) 1.712 ms 1.40 ms 1.34 ms

2 10.81.130.1 (10.81.130.1) 52.01 ms 34.38 ms 118.97 ms

3 bb1-fe1-0.mtgmry1.md.home.net (24.11.248.1) 13.30 ms 100.92 ms 31.99 ms

4 c2-se9-0-10.washdc1.home.net (24.7.73.25) 118.63 ms 94.92 ms 121.10 ms

5 24.7.71.6 (24.7.71.6) 127.63 ms 26.29 ms 132.07 ms

6 p4-6-1-0.r00.plalca01.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.2.245) 186.02 ms 164.81 ms 156.44 ms

7 p16-0-0-0.r06.plalca01.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.2.161) 86.59 ms 130.28 ms 121.09 ms

8 p16-0-0-0.r04.snjsca03.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.3.162) 84.594 ms 117.42 ms 174.59 ms

9 p16-3-0-0.r01.snjsca03.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.2.63) 123.87 ms 91.39 ms 119.79 ms

10 p4-2-0-0.r00.lsanca01.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.2.26) 142.38 ms 166.11 ms 95.32 ms

11 ge-0-0-0.a02.lsanca02.us.ra.verio.net (129.250.29.116) 137.59 ms 98.28 ms 256.11 ms

12 uscisi-pl.customer.ni.net (209.189.66.66) 98.64 ms 125.03 ms 231.11 ms

13 207.151.151.2 (207.151.151.2) 192.06 ms 164.52 ms 103.30 ms

14 icann-IWC.interworld.net (206.124.230.170) 113.33 ms 145.72 ms 107.39 ms

15 * host159-3.icann.org (207.151.159.3) 99.67 ms 178.72 msThis trace shows that 15 intermediate gateways are involved, that packets are making the trip, and that round trip travel time for packets from this host to www.internic.net is about 140 ms.

Variations and bugs in the implementation of ICMP on different

types of gateways, as well as the unpredictable nature of the path a

datagram can take through a network, can cause some odd displays. For

this reason, you shouldn’t examine the output of traceroute too closely. The most important

things in the traceroute output

are:

Did the packet get to its remote destination?

If not, where did it stop?

In the code below we show another trace of the path to www.internic.net. This time the trace does not go all the way through to the InterNIC.

$ traceroute www.internic.net

traceroute to www.internic.net (207.151.159.3), 30 hops max, 40 byte packets

1 ani (192.168.0.1) 1.712 ms 1.40 ms 1.34 ms

2 10.81.130.1 (10.81.130.1) 52.01 ms 34.38 ms 118.97 ms

3 bb1-fe1-0.mtgmry1.md.home.net (24.11.248.1) 13.30 ms 100.92 ms 31.99 ms

4 c2-se9-0-10.washdc1.home.net (24.7.73.25) 118.63 ms 94.92 ms 121.10 ms

5 24.7.71.6 (24.7.71.6) 127.63 ms 26.29 ms 132.07 ms

6 p4-6-1-0.r00.plalca01.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.2.245) 186.02 ms 164.81 ms 156.44 ms

7 p16-0-0-0.r06.plalca01.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.2.161) 86.59 ms 130.28 ms 121.09 ms

8 p16-0-0-0.r04.snjsca03.us.bb.verio.net (129.250.3.162) 84.594 ms 117.42 ms 174.59 ms

9 * * *

10 * * *

.

.

.

29 * * *

30 * * *When traceroute fails to get

packets through to the remote end system, the trace trails off,

displaying a series of three asterisks at each hop count until the

count reaches 30. If this happens, contact the administrator of the

remote host you’re trying to reach, and the administrator of the last

gateway displayed in the trace. Describe the problem to them; they may

be able to help. In our example, the last gateway that responded to

our packets was

p16-0-0-0.r04.snjsca03.us.bb.verio.net. We would

therefore contact this system administrator and the administrator of

www.internic.net.

To contact a remote administrator, you must know who to contact. whois helps you locate important people. One

of the most important pieces of information in a network is who is in

charge at the other end. When troubleshooting a network problem,

whois is a tool that helps you find

this out.

whois obtains the requested

information from the Internet white pages. The white pages is a

database of information about responsible people that is maintained by

the Internet registrars. When you request an official network number

or domain name, you are asked to provide contact information, which

becomes your personal record in the white pages database. Because of

this, everyone who is responsible for an official network or domain is

supposed to have an entry in the white pages, and that entry can be

retrieved by anyone who needs to contact them.

Many Unix systems provide a whois command to query the white pages. The

general form of this command is:

% whois [-hserver]name

The name field is the information to be searched for in the white pages database. The server field is the name of a system containing the white pages.

In the following example, we search for contact information for

the verio.net domain, which is the domain where

the remote router from the traceroute example is located.

$ whois verio.net

[whois.crsnic.net]

Whois Server Version 1.3

Domain names in the .com, .net, and .org domains can now be registered

with many different competing registrars. Go to http://www.internic.net

for detailed information.

Domain Name: VERIO.NET

Registrar: MELBOURNE IT, LTD. D/B/A INTERNET NAMES WORLDWIDE

Whois Server: whois.inww.com

Referral URL: http://www.inww.com

Name Server: NS0.VERIO.NET

Name Server: NS1.VERIO.NET

Name Server: NS2.VERIO.NET

Updated Date: 13-jun-2001

>>> Last update of whois database: Tue, 17 Jul 2001 02:04:28 EDT <<<

The Registry database contains ONLY .COM, .NET, .ORG, .EDU domains and

Registrars.

[whois.inww.com]

Domain Name.......... verio.net

Creation Date........ 1996-12-07

Registration Date.... 2000-05-10

Expiry Date.......... 2001-12-06

Organisation Name.... Verio, Inc.

Organisation Address. 8005 South Chester Street

Organisation Address. Suite 200

Organisation Address. Englewood

Organisation Address. CO

Organisation Address. 80112

Organisation Address. UNITED STATES

Admin Name........... Hostmaster Verio

Admin Address........ 8005 South Chester Street

Admin Address........ Suite 200

Admin Address........ Englewood

Admin Address........ 80112

Admin Address........ CO

Admin Address........ UNITED STATES

Admin Email.......... DomainAdmin@verio.net

Admin Phone.......... 214 290 8620

Admin Fax............ .

Tech Name............ Hostmaster Verio

Tech Address......... 8005 South Chester Street

Tech Address......... Suite 200

Tech Address......... Englewood

Tech Address......... CO

Tech Address......... 80112

Tech Address......... UNITED STATES

Tech Email........... hostmaster@verio.net

Tech Phone........... 214 290 8620

Tech Fax............. .

Name Server.......... NS0.VERIO.NET

Name Server.......... NS1.VERIO.NET

Name Server.......... NS2.VERIO.NETThe query displays the name, address, and telephone number of

the contacts for the domain, as well as a list of hosts providing

authoritative name service for the domain. This example shows how it

is supposed to work, and for substantial, well-run networks such as

verio.net, it usually does. Unfortunately, many

whois queries return no useful

information because the white pages database is poorly maintained. If

whois provides no information, try

checking DNS name service. The DNS SOA record should contain a mailing

address for a domain contact who may be able to point you to the right

system administrator.

Name server problems are indicated when the “unknown host” error

message is returned by the user’s application. Name server problems can

usually be diagnosed with nslookup or

dig. nslookup is discussed in detail in Chapter 8; dig is an alternative tool with similar

functionality and is discussed in this chapter. Before looking at

dig, let’s take another look at

nslookup and see how it is used to troubleshoot name

service.

The three features of nslookup

covered in Chapter 8 are particularly

important for troubleshooting remote name server problems. These

features are its ability to:

Locate the authoritative servers for the remote domain using the NS query

Obtain all records about the remote host using the ANY query

Browse all entries in the remote zone using

nslookup’slsandviewcommands

When troubleshooting a remote server problem, directly query the authoritative servers returned by the NS query. Don’t rely on information returned by non-authoritative servers. If the problems that have been reported are intermittent, query all of the authoritative servers in turn and compare their answers. Intermittent name server problems are sometimes caused by the remote servers returning different answers to the same query.

The ANY query returns all records about a host, thus giving the

broadest range of troubleshooting information. Simply knowing what

information is (and isn’t) available can solve a lot of problems. For

example, if the query returns an MX record but no A record, it is easy

to understand why the user couldn’t telnet to that host! Many hosts are accessible

to mail that are not accessible by other network services. In this case,

the user is confused and is trying to use the remote host in an

inappropriate manner.

If you are unable to locate any information about the hostname

that the user gave you, perhaps the hostname is incorrect. Given that

the hostname you have is wrong, looking for the correct name is like

trying to find a needle in a haystack. However, nslookup can help. Use nslookup’s ls command to dump the remote zone file, and

redirect the listing to a file. Then use nslookup’s view command to browse through the file,

looking for names similar to the one the user supplied. Many problems

are caused by a mistaken hostname.

All of the nslookup features

and commands mentioned here are used in Chapter 8. However, some examples using

these commands to solve real name server problems will be helpful. The

three examples that follow are based on actual trouble reports.[148]

A user reported that she could resolve a certain hostname from her

workstation, but could not resolve the same hostname from the central

system. However, the central system could resolve other hostnames. We

ran several tests and found that we could resolve the hostname on some

systems and not on others. There seemed to be no predictable pattern

to the failure. So we used nslookup

to check the remote servers:

% nslookup Default Server: crab.wrotethebook.com Address: 172.16.12.1 > set type=NS > foo.edu. Server: crab.wrotethebook.com Address: 172.16.12.1 foo.edu nameserver = gerbil.foo.edu foo.edu nameserver = red.big.com foo.edu nameserver = shrew.foo.edu gerbil.foo.edu inet address = 198.97.99.2 red.big.com inet address = 184.6.16.2 shrew.foo.edu inet address = 198.97.99.1 > set type=ANY > server gerbil.foo.edu Default Server: gerbil.foo.edu Address: 198.97.99.2 > hamster.foo.edu Server: gerbil.foo.edu Address: 198.97.99.2 hamster.foo.edu inet address = 198.97.99.8 > server red.big.com Default Server: red.big.com Address: 184.6.16.2 > hamster.foo.edu Server: red.big.com Address: 184.6.16.2 *** red.big.com can't find hamster.foo.edu: Non-existent domain

This sample nslookup session

contains several steps. The first step is to locate the authoritative

servers for the hostname in question

(hamster.foo.edu). We set the query type to NS to

get the name server records, and query for the domain

(foo.edu) in which the hostname is found. This

returns three names of authoritative servers:

gerbil.foo.edu, red.big.com,

and shrew.foo.edu.

Next, we set the query type to ANY to look for any records related to the hostname in question. Then we set the server to the first server in the list, gerbil.foo.edu, and query for hamster.foo.edu. This returns an address record. So server gerbil.foo.edu works fine. We repeat the test using red.big.com as the server, and it fails. No records are returned.

The next step is to get SOA records from each server and see if they are the same:

> set type=SOA > foo.edu. Server: red.big.com Address: 184.6.16.2 foo.edu origin = gerbil.foo.edu mail addr = amanda.gerbil.foo.edu serial=10164, refresh=43200, retry=3600, expire=3600000, min=2592000 > server gerbil.foo.edu Default Server: gerbil.foo.edu Address: 198.97.99.2 > foo.edu. Server: gerbil.foo.edu Address: 198.97.99.2 foo.edu origin = gerbil.foo.edu mail addr = amanda.gerbil.foo.edu serial=10164, refresh=43200, retry=3600, expire=3600000, min=2592000 > exit

If the SOA records have different serial numbers, perhaps the zone file, and therefore the hostname, has not yet been downloaded to the slave server. If the serial numbers are the same and the data is different, as in this case, there is a definite problem. Contact the remote domain administrator and notify her of the problem. The administrator’s mailing address is shown in the “mail addr” field of the SOA record. In our example, we would send mail to amanda@gerbil.foo.edu reporting the problem.

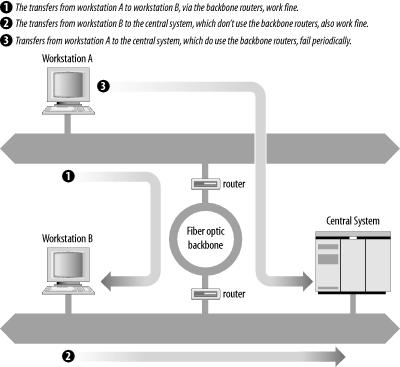

This problem was reported by the administrator of one of our slave name servers. The administrator reported that his server could not resolve a certain hostname in a domain for which his server was a slave server. The master server was, however, able to resolve the name. The administrator dumped his cache (more on dumping the server cache in the next section), and he could see in the dump that his server had the correct entry for the host. But his server still would not resolve that hostname to an IP address!

The problem was replicated on several other slave servers. The master server would resolve the name; the slave servers wouldn’t. All servers had the same SOA serial number, and a dump of the cache on each server showed that they all had the correct address records for the hostname in question. So why wouldn’t they resolve the hostname to an address?

Visualizing the difference between the way master and slave servers load their data made us suspicious of the zone file transfer. Master servers load the data directly from local disk files. Slave servers transfer the data from the master server via a zone file transfer. Perhaps the zone files were getting corrupted. We displayed the zone file on one of the slave servers, and it showed the following data:

% cat /usr/etc/events.wrotethebook.com.hosts

PCpma IN A 172.16.64.159

IN HINFO "pc" "n3/800eventsnutscom"

PCrkc IN A 172.16.64.155

IN HINFO "pc" "n3/800eventsnutscom"

PCafc IN A 172.16.64.189

IN HINFO "pc" "n3/800eventsnutscom"

accu IN A 172.16.65.27

cmgds1 IN A 172.16.130.40

cmg IN A 172.16.130.30

PCgns IN A 172.16.64.167

IN HINFO "pc" "(3/800eventsnutscom"

gw IN A 172.16.65.254

zephyr IN A 172.16.64.188

IN HINFO "Sun" "sparcstation"

ejw IN A 172.16.65.17

PCecp IN A 172.16.64.193

IN HINFO "pc" "n Lsparcstationstcom"Notice the odd display in the last field of the HINFO statement for each PC.[149]

This data might have been corrupted in the transfer or it might

be bad on the master server. We used nslookup to check that:

% nslookup Default Server: crab.wrotethebook.com Address: 172.16.12.1 > server 24seven.events.wrotethebook.com Default Server: 24seven.events.wrotethebook.com Address: 172.16.6.1 > set query=HINFO > PCwlg.events.wrotethebook.com Server: 24seven.events.wrotethebook.com Address: 172.16.6.1 PCwlg.events.wrotethebook.com CPU=pc OS=ov packet size error (0xf7fff590 != 0xf7fff528) > exit

In this nslookup example, we

set the server to

24seven.events.wrotethebook.com, which is the

master server for events.wrotethebook.com. Next

we queried for the HINFO record for one of the hosts that appeared to

have a corrupted record. The “packet size error” message clearly

indicates that nslookup was even

having trouble retrieving the HINFO record directly from the master

server. We contacted the administrator of the master server and told

him about the problem, pointing out the records that appeared to be in

error. He discovered that he had forgotten to put an operating system

entry on some of the HINFO records. He corrected this, and it fixed

the problem.

The previous problem was caused by the name server cache being corrupted by bad data. Cache corruption can occur even if your system is not a slave server. All servers cache answers. If those answers are corrupted, entries in the cache may become corrupted. Dumping the cache can help diagnose these types of problems.

For example, a user reported intermittent name server failures.

She had no trouble with any hostnames within the local domain or with

some names outside the local domain, but names in several different

remote domains would not resolve. nslookup tests produced no solid clues, so

the name server cache was dumped and examined for problems. The root

server entries were corrupted, so named was reloaded to clear the cache and

reread the named.ca file. Here’s how it was

done.

The ndc dumpdb command or the SIGINT signal causes named to dump the name server cache to the

file /var/tmp/named_dump.db. The following

example uses the signal:

# kill -INT 'cat /etc/named.pid'The process ID of named can

be obtained from /etc/named.pid, as in the

example above, because named writes

its process ID in that file during startup.[150]

Once named writes its cache

to the file, we can examine the file to see if the names and addresses

servers are correct. The named_dump.db file is

composed of three sections: the zone table section, the Cache &

Data section, and the Hints section.

The first section of the dump file is the zone table, which shows the zones loaded when the server started. The zone table from the master server for zones wrotethebook.com and 16.172.in-addr.arpa would show the following:

; Dumped at Tue Jul 17 16:08:18 2001 ;; ++zone table++ ; . (type 6, class 0, source Nil) ; time=0, lastupdate=0, serial=0, ; refresh=0, retry=0, expire=0, minimum=0 ; ftime=0, xaddrcnt=0, state=0000, pid=0 ; . (type 3, class 1, source named.ca) ; time=0, lastupdate=965723221, serial=0, ; refresh=0, retry=0, expire=0, minimum=4294967295 ; ftime=965723221, xaddrcnt=0, state=0040, pid=0 ; 0.0.127.in-addr.arpa (type 1, class 1, source named.local) ; time=0, lastupdate=0, serial=1997022700, ; refresh=0, retry=14400, expire=3600000, minimum=86400 ; ftime=965723221, xaddrcnt=0, state=0041, pid=0 ; wrotethebook.com (type 1, class 1, source wrotethebook.com.hosts) ; time=0, lastupdate=0, serial=2001070501, ; refresh=0, retry=1800, expire=604800, minimum=900 ; ftime=982967703, xaddrcnt=0, state=0041, pid=0 ; 16.172.in-addr.arpa (type 1, class 1, source 172.16.rev) ; time=0, lastupdate=0, serial=2001071602, ; refresh=0, retry=1800, expire=604800, minimum=900 ; ftime=982968091, xaddrcnt=0, state=0041, pid=0 ;; --zone table--

The section begins by displaying the date and time that the

dump was taken. Labels at the start and end of the section delimit

the zone table. As indicated by the fact that each line begins with

a semicolon, all of these lines are comments meant to provide

information to the system administrator. None of these are real

database entries used by DNS. From the example above, you can tell

that this server has a zone

statement in its named.conf file for the

following domains:

- . (dot)

The root domain that was loaded from a source file called named.ca. This is the hints file described in Chapter 8.

- 0.0.127.in-addr.arpa

The loopback domain that was loaded from the source file named.local.

- wrotethebook.com

The wrotethebook.com domain that was loaded from the wrotethebook.com.hosts source file.

- 16.172.in-addr.arpa

The reverse domain 16.172.in-addr.arpa that was loaded from the 172.16.rev source file.

The values from the SOA record of each zone are also printed. In the sample shown above, every zone except the root (.) has an SOA record.

The zone table section identifies every zone for which the

server has authority. It tells you where the server obtained the

information about the zone, and it tells you what defaults are set

for the zone by the SOA record. If a zone is missing or is loading

from the wrong source, correct the zone statement in the

named.conf file.

The second section of the dump file is by far the longest. This is the section that contains all of the DNS information known to the server. Because of the section’s length, the Cache & Data information shown below is just an excerpt:

; Note: Cr=(auth,answer,addtnl,cache) tag only shown for non-auth RR's

; Note: NT=milliseconds for any A RR which we've used as a nameserver

; --- Cache & Data ---

$ORIGIN .

. 513482 IN NS H.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS C.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS G.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS F.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS B.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS J.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS K.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS L.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS M.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS I.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS E.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS D.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

513482 IN NS A.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cr=auth

... Many Lines Deleted ...

$ORIGIN ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

K 599882 IN A 193.0.14.129 ;NT=9 Cr=answer

A 599882 IN A 198.41.0.4 ;NT=10 Cr=answer

L 599882 IN A 198.32.64.12 ;NT=5 Cr=answer

M 599882 IN A 202.12.27.33 ;NT=15 Cr=answer

B 599882 IN A 128.9.0.107 ;NT=5 Cr=answer

C 599882 IN A 192.33.4.12 ;NT=165 Cr=answer

D 599882 IN A 128.8.10.90 ;NT=12 Cr=answer

E 599882 IN A 192.203.230.10 ;NT=6 Cr=answer

F 599882 IN A 192.5.5.241 ;NT=1021 Cr=answer

G 599882 IN A 192.112.36.4 ;NT=1023 Cr=answer

H 599882 IN A 128.63.2.53 ;NT=6 Cr=answer

I 599882 IN A 192.36.148.17 ;NT=7 Cr=answer

J 599882 IN A 198.41.0.10 ;NT=6 Cr=answer

... Many Lines Deleted ...

$ORIGIN com.

foobirds 86400 IN RP admin.foobirds.org. hotline.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN MX 10 wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN MX 20 parrot.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN NS wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN NS parrot.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN SOA wren.foobirds.org. admin.wren.foobirds.org. (

2000020501 21600 1800 604800 900 ) ;Cl=2

$ORIGIN foobirds.org.

ducks 86400 IN NS ruddy.ducks.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN NS wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN NS bear.mammals.org. ;Cl=2

news 86400 IN CNAME parrot.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

robin 86400 IN RP admin.foobirds.org. hotline.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN MX 5 wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.2 ;Cl=2

puffin 86400 IN RP admin.foobirds.org. hotline.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN MX 5 wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.17 ;Cl=2

wren 86400 IN RP admin.foobirds.org. hotline.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.1 ;Cl=2

parrot 86400 IN RP logan.parrot.foobirds.org. logan.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.3 ;Cl=2

logan 86400 IN TXT "Logan Little (301)555-2021" ;Cl=2

crow 86400 IN RP doris.crow.foobirds.org.foobirds.org. crowRP.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.5 ;Cl=2

localhost 86400 IN A 127.0.0.1 ;Cl=2

terns 86400 IN NS sooty.terns.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN NS arctic.terns.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

www 86400 IN CNAME wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

hotline 86400 IN TXT "Support hotline (301)555-2000" ;Cl=2

bob 86400 IN CNAME robin.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

redbreast 86400 IN CNAME robin.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

hawkRP 86400 IN TXT "Clark Smart (301)555-2099" ;Cl=2

kestrel 86400 IN RP clark.foobirds.org.foobirds.org. hawkRP.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.20 ;Cl=2

crowRP 86400 IN TXT "Doris Nathan (301)555-2078" ;Cl=2

kestral 86400 IN CNAME kestrel.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

hawk 86400 IN RP clark.foobirds.org.foobirds.org. hawkRP.foobirds.org. ;Cl=2

86400 IN A 172.16.5.4 ;Cl=2

foobirds-net 86400 IN PTR 0.0.16.172.in-addr.arpa. ;Cl=2

$ORIGIN terns.foobirds.org.

arctic 86400 IN A 172.16.30.251 ;Cl=2

sooty 86400 IN A 172.16.30.250 ;Cl=2

$ORIGIN 172.in-addr.arpa.

16 86400 IN NS wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

86400 IN SOA wren.foobirds.org. admin.wren.foobirds.org. (

2000021602 21600 1800 604800 900 ) ;Cl=4

$ORIGIN 6.16.172.in-addr.arpa.

1 86400 IN PTR arctic.terns.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

$ORIGIN 12.16.172.in-addr.arpa.

3 86400 IN PTR wren.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

$ORIGIN 5.16.172.in-addr.arpa.

20 86400 IN PTR kestrel.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

4 86400 IN PTR hawk.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

2 86400 IN PTR robin.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

17 86400 IN PTR puffin.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

5 86400 IN PTR crow.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

3 86400 IN PTR parrot.foobirds.org. ;Cl=4

$ORIGIN 0.127.in-addr.arpa.

0 86400 IN NS localhost. ;Cl=5

86400 IN SOA localhost. root.localhost. (

1997022700 28800 14400 3600000 86400 ) ;Cl=5

$ORIGIN 0.0.127.in-addr.arpa.

1 86400 IN PTR localhost. ;Cl=5The example is long even though the dump was taken shortly after the server started, and many lines have been deleted from the listing. The bulk of the data shown is information loaded from the local zone files, but a dump file also contains a good deal of cached information. Large chunks of the cache are the result of information provided in the authority and additional sections of the query responses. At least as much data enters the cache in this manner as enters as a result of specific answers to queries. The large number of NS entries and the A records for those NS entries make this clear.

The Cache & Data section is segmented by $ORIGIN directives. All of the other lines in this section are clearly identifiable DNS resource records. But some additional information is appended to the end of each record as a comment. Three comments that the server commonly adds to a record include the following:

ClIdentifies the number of fields in the current origin. Therefore, when the origin is 0.0.127.in-addr.arpa, the Cl value is 5, and when the origin is wrotethebook.com, the Cl value is 2. The root (.) is assigned a Cl value of 0.

NtThe round trip time for queries to the specified name server. This comment is added only to the address records of name servers. The round trip time helps

namedselect the best server for a given query.CrThe “credibility” tag identifies the authority level of the source of cached information. BIND has three authority levels:

authAn authoritative answer.

answerAn answer from a non-authoritative source.

addtnlA record learned from the authority or additional section of a query response.

The Cr value is used by named when a record is received that

already exists in the name server’s cache. If the record received

has a higher credibility rating than the record in the cache, the

new record replaces the cached record. If the new record has a lower

credibility rating than the record in the cache, the cached record

is retained. Of the Cr values, auth is the most credible and addtnl is the least credible.

The comments at the end of a record are not the only comments that you might see in the Cache & Data section of a dump file. Negative cached information also appears in the dump as a comment. There are no examples of this in our sample dump file, but if there were, you would see a normal resource record that starts with a semicolon. In other words, the negative cached information appears as a resource record that has been commented out of the file. Additionally, the tag NXDOMAIN is written near the end of the record.

Examine the Cache & Data section to discover if the data you entered in your zone file has been loaded as you expect. Also use this section to see if the information you have loaded from a remote server is what you expect. Local data can be corrected locally. Incorrect data from a remote server may require coordination with the administrator of a remote domain.

The last section in the dump file is the Hints section. This section contains the list of root name servers loaded from the hints file. (Defining and using the hints file is discussed in Chapter 8.) This hints file is used only when the name server starts. Once the server starts, one of the root servers is queried for an authoritative list of root servers. It is the authoritative list obtained from the root server that you see in the Cache & Data section following the $ORIGIN . statement.

The Hints section from our sample system is shown below.

Notice that all of the name servers in the Hints section have an Nt

number assigned. named queries

each server to establish a round trip time to select the best root

server to use.

; --- Hints ---

$ORIGIN .

. 3600000 IN NS A.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS B.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS C.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS D.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS E.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS F.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS G.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS H.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS I.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS J.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS K.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS L.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

3600000 IN NS M.ROOT-SERVERS.NET. ;Cl=0

$ORIGIN ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

K 3600000 IN A 193.0.14.129 ;NT=2 Cl=0

L 3600000 IN A 198.32.64.12 ;NT=5 Cl=0

A 3600000 IN A 198.41.0.4 ;NT=6 Cl=0

M 3600000 IN A 202.12.27.33 ;NT=10 Cl=0

B 3600000 IN A 128.9.0.107 ;NT=134 Cl=0

C 3600000 IN A 192.33.4.12 ;NT=8 Cl=0

D 3600000 IN A 128.8.10.90 ;NT=24 Cl=0

E 3600000 IN A 192.203.230.10 ;NT=2 Cl=0

F 3600000 IN A 192.5.5.241 ;NT=22 Cl=0

G 3600000 IN A 192.112.36.4 ;NT=2 Cl=0

H 3600000 IN A 128.63.2.53 ;NT=22 Cl=0

I 3600000 IN A 192.36.148.17 ;NT=2 Cl=0

J 3600000 IN A 198.41.0.10 ;Cl=0The purpose of dumping the DNS cache is to examine what data is stored internally by DNS and how it is stored. Examining the authoritative information that you provide to the server in the zone files will give you insight into how that data is being stored. Examining the other data in the cache shows you how your users use DNS. Learning how DNS is normally used can help identify when usage patterns change.

If you see problems in the dump file, force named to reload its cache with the

ndc reload command (on BIND 9,

use rndc reload), or with the SIGHUP signal as

shown below:

# kill -HUP 'cat /etc/named.pid'This clears the cache and reloads the valid root server entries from your named.ca file.

If you know which system is corrupting your cache, instruct

your system to ignore updates from the culprit by using a server statement in the

/etc/named.conf file with the bogus option set to yes. The server statement lists the IP address of a

name server. Setting bogus to

yes in the server statement tells named that information from that server

cannot be trusted. For example, the previous section described a

problem where 24seven.events.wrotethebook.com

(172.16.16.1) was causing cache corruption with improperly formatted

HINFO records. The following entry in the

named.conf file would reject answers from

24seven.events.wrotethebook.com and thus

prevent the cache corruption:

server 172.16.16.1 {

bogus yes;

};Setting bogus to yes is only a temporary measure, designed

to keep things running while the remote domain administrator has a

chance to diagnose and repair the problem. Once the remote system is

fixed, remove the server

statement

from

named.conf.

An alternative to nslookup for making name service queries is

dig. dig queries are usually entered as

single-line commands, while nslookup is usually run as an interactive

session. But the dig command

performs essentially the same function as nslookup. Which you use is mostly a matter

of personal choice. They both work well.

As an example, we’ll use dig

to ask the root server b.root-servers.net for the

NS records for the mit.edu domain. To do this,

enter the following command: