Chapter 13 refers to specific TCP/IP headers that are documented here. This is not an exhaustive list of headers; only the headers used in the troubleshooting examples in Chapter 13 are covered:

IP Datagram Header, as defined in RFC 791, Internet Protocol

TCP Segment Header, as defined in RFC 793, Transmission Control Protocol

ICMP Parameter Problem Message Header, as defined in RFC 792, Internet Control Message Protocol

Each header is presented using an excerpt from the RFC that defines the header. These are not exact quotes; the excerpts have been slightly edited to better fit this text. However, the importance of using primary sources for troubleshooting protocol problems is still emphasized. These headers are provided here to help you follow the examples in Chapter 13. For real troubleshooting, use the real RFCs. You can obtain your own copies of the RFCs by following the instructions at the end of this appendix.

This description is taken from pages 11 to 15 of RFC 791, Internet Protocol.

Internet Header Format

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|Version| IHL |Type of Service| Total Length |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Identification |Flags| Fragment Offset |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Time to Live | Protocol | Header Checksum |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Destination Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Options | Padding |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Version: 4 bits

The Version field indicates the format of the internet header.

This document describes version 4.

IHL: 4 bits

Internet Header Length is the length of the internet header in 32

bit words. The minimum value for a correct header is 5.

Type of Service: 8 bits

The Type of Service indication the quality of service desired.

The meaning of the bits is explained below.

Bits 0-2: Precedence.

Bit 3: 0 = Normal Delay, 1 = Low Delay.

Bits 4: 0 = Normal Throughput, 1 = High Throughput.

Bits 5: 0 = Normal Reliability 1 = High Reliability.

Bit 6-7: Reserved for Future Use.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| | | | | | |

| PRECEDENCE | D | T | R | 0 | 0 |

| | | | | | |

+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

Precedence

111 - Network Control

110 - Internetwork Control

101 - CRITIC/ECP

100 - Flash Override

011 - Flash

010 - Immediate

001 - Priority

000 - Routine

Total Length: 16 bits

Total Length is the length of the datagram, measured in octets

(bytes), including internet header and data.

Identification: 16 bits

An identifying value assigned by the sender to aid in assembling

the fragments of a datagram.

Flags: 3 bits

Various Control Flags. The Flag bits are explained below:

Bit 0: reserved, must be zero

Bit 1: (DF) 0 = May Fragment, 1 = Don't Fragment.

Bit 2: (MF) 0 = Last Fragment, 1 = More Fragments.

0 1 2

+---+---+---+

| | D | M |

| 0 | F | F |

+---+---+---+

Fragment Offset: 13 bits

This field indicates where in the datagram this fragment belongs.

The fragment offset is measured in units of 8 octets (64 bits).

The first fragment has offset zero.

Time to Live: 8 bits

This field indicates the maximum time the datagram is allowed to

remain in the internet system.

Protocol: 8 bits

This field indicates the Transport Layer protocol that the data

portion of this datagram is passed to. The values for various

protocols are specified in the "Assigned Numbers" RFC.

Header Checksum: 16 bits

A checksum on the header only. Since some header fields change

(e.g., time to live), this is recomputed and verified at each

point that the internet header is processed. The checksum

algorithm is:

The checksum field is the 16 bit one's complement of the one's

complement sum of all 16 bit words in the header. For purposes

of computing the checksum, the value of the checksum field is

zero.

Source Address: 32 bits

The source IP address. See Chapter 2 for a

description of IP addresses.

Destination Address: 32 bits

The destination IP address. See Chapter 2 for a description of IP

addresses.

Options: variable

The options may or may not appear in datagrams, but they must be

implemented by all IP modules (host and gateways). No options

were used in any of the datagrams examined

in Chapter 13.This description is taken from pages 15 to 17 of RFC 793, Transmission Control Protocol.

TCP Header Format

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Port | Destination Port |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Sequence Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Acknowledgment Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Data | |U|A|P|R|S|F| |

| Offset| Reserved |R|C|S|S|Y|I| Window |

| | |G|K|H|T|N|N| |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Checksum | Urgent Pointer |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Options | Padding |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| data |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Source Port: 16 bits

The source port number.

Destination Port: 16 bits

The destination port number.

Sequence Number: 32 bits

The sequence number of the first data octet (byte) in this segment

(except when SYN is present). If SYN is present the sequence

number is the initial sequence number (ISN) and the first data

octet is ISN+1.

Acknowledgment Number: 32 bits

If the ACK control bit is set, this field contains the value of

the next sequence number the sender of the segment is expecting to

receive. Once a connection is established this is always sent.

Data Offset: 4 bits

The number of 32 bit words in the TCP Header. This indicates

where the data begins. The TCP header (even one including options)

is an integral number of 32 bits long.

Reserved: 6 bits

Reserved for future use. Must be zero.

Control Bits: 6 single-bit values (from left to right):

URG: Urgent Pointer field significant

ACK: Acknowledgment field significant

PSH: Push Function

RST: Reset the connection

SYN: Synchronize sequence numbers

FIN: No more data from sender

Window: 16 bits

The number of data octets (bytes) the sender of this segment is

willing to accept.

Checksum: 16 bits

The checksum field is the 16 bit one's complement of the one's

complement sum of all 16 bit words in the header and text.

Urgent Pointer: 16 bits

This field contains the current value of the urgent pointer as a

positive offset from the sequence number in this segment. The

urgent pointer points to the sequence number of the octet

following the urgent data. This field is only be interpreted

in segments with the URG control bit set.

Options: variable

Options may occupy space at the end of the TCP header and are a multiple of 8 bits in length.This description is taken from pages 8 and 9 of RFC 792, Internet Control Message Protocol.

Parameter Problem Message

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Type | Code | Checksum |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Pointer | unused |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Internet Header + 64 bits of Original Data Datagram |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Type

12

Code

0 = pointer indicates the error.

Checksum

The checksum is the 16-bit ones's complement of the one's

complement sum of the ICMP message starting with the ICMP Type.

For computing the checksum, the checksum field should be zero.

Pointer

If code = 0, identifies the octet where an error was detected.

Internet Header + 64 bits of Data Datagram

The internet header plus the first 64 bits of the datagram that elicited this error response.Throughout this book, we have referred to many RFCs. These are the Internet documents used for everything from general information to the definitions of the TCP/IP protocol standards. As a network administrator, there are several important RFCs that you’ll want to read. This section describes how you can obtain them.

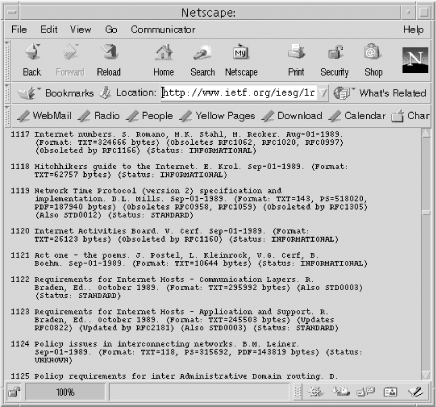

RFCs are available at http://www.ietf.org. Follow the RFC Pages link from that home page. The page that appears allows you to retrieve an RFC by specifying its number. The page also has links to the RFC Index and the RFC Editor Web Pages. The index is useful for general browsing. It helps you map RFC names to numbers, and it tells you when an RFC has been updated or replaced. Figure G-1 shows a network administrator scrolling through the index looking for RFC 1122.

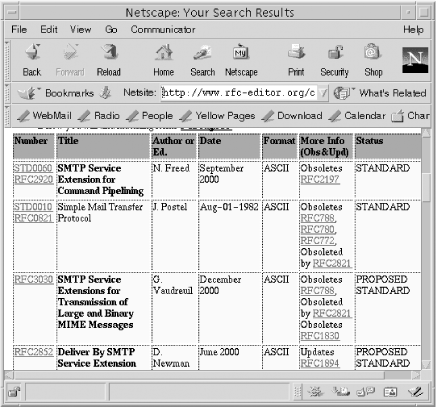

Of even more interest are the RFC Editor Web Pages. Selecting this link takes you to http://www.rfc-editor.org, where you can select RFC Search and Retrieval. The page that is displayed provides access to a hyperlinked RFC index and to a search tool that allows you to look for RFC titles, numbers, authors, or keywords.

Assume you want to find out more about the SMTP service extensions that have been proposed for Extended SMTP. Figure G-2 shows the first page displayed as a result of this query.

The Web provides the most popular and best method for browsing

through RFCs. However, if you know what you want, anonymous FTP can be a

faster way to retrieve a specific document. RFCs are stored at ftp://ftp.ietf.org in the

rfc directory. This stores the RFCs with filenames

in the form rfcnnnn.txt or

rfcnnnn.ps, where nnnn is the

RFC number and txt or ps

indicates whether the RFC is ASCII text or PostScript. To retrieve RFC

1122, FTP to ftp://ftp.ietf.org

and enter get rfc/rfc1122.txt at the ftp> prompt. This is generally a very quick

way to get an RFC if you know what you want.

While anonymous FTP is the fastest way and the Web is the best way to get an RFC, they are not the only ways. You can also obtain RFCs through electronic mail. Electronic mail is available to many users who are denied direct access to Internet services because they are on a nonconnected network or are sitting behind a restrictive firewall. Also, there are times when email provides sufficient service because you don’t need the document quickly.

Retrieve RFCs through email by sending mail to

mailserv@ietf.org. Leave the Subject: line blank.

Request the RFC in the body of the email text, preceding the pathname

of the RFC with the keyword FILE.

In this example, we request RFC 1258.

% mail mailserv@ietf.org Subject: FILE /rfc/rfc1258.txt ^D

The technique works very well. In the time it took to type these paragraphs, the requested RFC was already in my mailbox.