Routing is the glue that binds the Internet together. Without it, TCP/IP traffic is limited to a single physical network. Routing allows traffic from your local network to reach its destination somewhere else in the world—perhaps after passing through many intermediate networks.

The important role of routing and the complex interconnection of Internet networks make the design of routing protocols a major challenge to network software developers. Consequently, most discussions of routing concern protocol design. Very little is written about the important task of properly configuring routing protocols. However, more day-to-day problems are caused by improperly configured routers than by improperly designed routing algorithms. As system administrators, we need to ensure that the routing on our systems is properly configured. This is the task we tackle in this chapter.

First, we must make a distinction between routing and routing protocols. All systems route data, but not all systems run routing protocols. Routing is the act of forwarding datagrams based on the information contained in the routing table. Routing protocols are programs that exchange the information used to build routing tables.

A network’s routing configuration does not always require a routing protocol. In situations where the routing information does not change—for example, when there is only one possible route—the system administrator usually builds the routing table manually. Some networks have no access to any other TCP/IP networks and therefore do not require that the system administrator build the routing table at all. The three most common routing configurations[67] are the following.

- Minimal routing

A network completely isolated from all other TCP/IP networks requires only minimal routing. A minimal routing table usually is built when the network interface is configured by adding a route for each interface. If your network doesn’t have direct access to other TCP/IP networks and you are not using subnetting, this may be the only routing table you’ll require.

- Static routing

A network with a limited number of gateways to other TCP/IP networks can be configured with static routing. When a network has only one gateway, a static route is the best choice. A static routing table is constructed manually by the system administrator using the

routecommand. Static routing tables do not adjust to network changes, so they work best where routes do not change.- Dynamic routing

A network with more than one possible route to the same destination should use dynamic routing. A dynamic routing table is built from the information exchanged by routing protocols. The protocols are designed to distribute information that dynamically adjusts routes to reflect changing network conditions. Routing protocols handle complex routing situations more quickly and accurately than the system administrator can. Routing protocols are designed not only to switch to a backup route when the primary route becomes inoperable, but also to decide which is the “best” route to a destination. On any network where there are multiple paths to the same destination, a routing protocol should be used.

Routes are built manually by the system administrator or dynamically by routing protocols. But no matter how routes are entered, they all end up in the routing table.

Let’s look at the contents of the routing table constructed when ifconfig is used to configure the network

interfaces on a Solaris 8 system:

% netstat -rn

Routing Table: IPv4

Destination Gateway Flags Ref Use Interface

-------------------- -------------------- ----- ----- ------ ---------

172.16.12.0 172.16.12.15 U 1 8 dnet0

224.0.0.0 172.16.12.15 U 1 0 dnet0

127.0.0.1 127.0.0.1 UH 20 3577 lo0The first entry is the route to network 172.16.12.0 through interface dnet0. Address 172.16.12.15 is not a remote gateway address; it is the address assigned to the dnet0 interface on this host. The other two entries do not define routes to real physical networks; both are special software conventions. 224.0.0.0 is the multicast address. This entry tells Solaris to send multicast addresses to interface 172.16.12.15 for delivery. The last entry is the loopback route to localhost created when lo0 was configured.

Look at the Flags field for these entries. All entries have the U (up) flag set, indicating that they are ready to be used, but no entry has the G (gateway) flag set. The G flag indicates that an external gateway is used. The G flag is not set because all of these routes are direct routes through local interfaces, not through external gateways.

The loopback route also has the H (host) flag set. This indicates that only one host can be reached through this route. The meaning of this flag becomes clear when you look at the Destination field for the loopback entry. It shows that the destination is a host address, not a network address. The loopback network address is 127.0.0.0. The destination address shown (127.0.0.1) is the address of localhost, an individual host. Some systems use a route to the loopback network and others use a route to the localhost, but all systems have some route for the loopback interface in the routing table.

Although this routing table has a host-specific route, most routes lead to networks. One reason network routes are used is to reduce the size of the routing table. An organization may have only one network but hundreds of hosts. The Internet has thousands of networks but millions of hosts. A routing table with a route for every host would be unmanageable.

Our sample table contains only one route to a physical network,

172.16.12.0. Therefore, this system can communicate only with hosts

located on that network. The limited capability of this routing table is

easily verified with the ping

command. ping uses the

ICMP Echo Message to force a remote host to echo a packet back to the

local host. If packets can travel to and from a remote host, it

indicates that the two hosts can successfully communicate.

To check the routing table on this system, first ping another host on the local network:

% ping -s crab

PING crab.wrotethebook.com: 56 data bytes

64 bytes from crab.wrotethebook.com (172.16.12.1): icmp_seq=0. time=11. ms

64 bytes from crab.wrotethebook.com (172.16.12.1): icmp_seq=1. time=10. ms

^C

----crab.wrotethebook.com PING Statistics----

2 packets transmitted, 2 packets received, 0% packet loss

round-trip (ms) min/avg/max = 10/10/11ping displays a line of output

for each ICMP ECHO_RESPONSE received.[68] When ping is

interrupted, it displays some summary statistics. All of this indicates

successful communication with crab. But if we check

a host that is not on network 172.16.12.0, say a host at O’Reilly, the

results are different.

% ping 207.25.98.2

sendto: Network is unreachableHere the message “sendto: Network is unreachable” indicates that this host does not know how to send data to the network that host 207.25.98.2 is on. There are only three routes in this system’s routing table, and none is a route to 207.25.98.0.

Even other subnets on books-net cannot be

reached using this routing table. To demonstrate this, ping a host on another subnet. For

example:

% ping 172.16.1.2

sendto: Network is unreachableThese ping tests show that the

minimal routing table created when the network interfaces were

configured allows communication only with other hosts on the local

network. If your network does not require access to any other TCP/IP

networks, this may be all you need. However, if it does require access

to other networks, you must add more routes to the routing table.

As we have seen, the minimal routing table works to reach hosts only

on the directly connected physical networks. To reach remote hosts,

routes through external gateways must be added to the routing table. One

way to do this is by constructing a static routing table with route commands.

Use the Unix route command to add or delete entries manually in the routing

table. For example, to add the route 207.25.98.0 to a Solaris system’s

routing table, enter:

# route add 207.25.98.0 172.16.12.1 1

add net 207.25.98.0: gateway crabThe first argument after the route command in this sample is the keyword add. The first

keyword on a route command line is

either add or delete, telling route either to add a new route or delete an

existing one. There is no default; if neither keyword is used, route displays the routing table.

The next value is the destination address, which is the address

reached via this route. The destination address can be specified as an

IP address, a network name from the /etc/networks

file, a hostname from the /etc/hosts file, or the

keyword default. Because most routes

are added early in the startup process, numeric IP addresses are used

more than names. This is done so that the routing configuration is not

dependent on the state of the name server software. Always use the

complete numeric address (all four bytes). route expands the address if it contains fewer

than four bytes, and the expanded address may not be what you

intended.[69]

If the keyword default is used for

the destination address, route

creates a default route.[70] The default route is used whenever there is no specific

route to a destination, and it is often the only route you need. If your

network has only one gateway, use a default route to direct all traffic

bound for remote networks through that gateway.

Next on the route command line

is the gateway address.[71] This is the IP address of the external gateway through

which data is sent to the destination address. The address must be the

address of a gateway on a directly connected network. TCP/IP routes

specify the next hop in the path to a remote destination. That next hop

must be directly accessible to the local host; therefore, it must be on

a directly connected network.

The last argument on the command line is the routing metric. The

metric argument is not used when routes are deleted, but

some older systems require it when a route is added; for Solaris 8, the

metric is optional. Systems that require a metric value for the route command use it only to decide if this is

a route through a directly attached interface or a route through an

external gateway. If the metric is 0, the route is installed as a route

through a local interface, and the G flag, which we saw in the netstat -i display, is not set. If the metric

value is greater than 0, the route is installed with the G flag set, and

the gateway address is assumed to be the address of an external gateway.

Static routing makes no real use of the metric. Dynamic routing is

required to make real use of varying metric values.

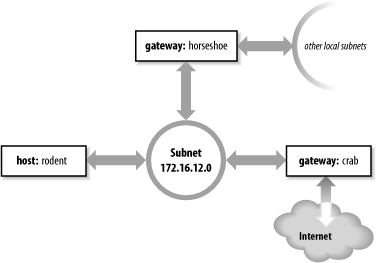

As an example, let’s configure static routing on the imaginary workstation rodent. Figure 7-1 shows the subnet 172.16.12.0. There are two gateways on this subnet, crab and horseshoe. crab is the gateway to thousands of networks on the Internet; horseshoe provides access to the other subnets on books-net. We’ll use crab as our default gateway because it is used by thousands of routes. The smaller number of routes through horseshoe can easily be entered individually. The number of routes through a gateway, not the amount of traffic it handles, decides which gateway to select as the default. Even if most of rodent’s network traffic goes through horseshoe to other hosts on books-net, the default gateway should be crab.

To install the default route on rodent, we enter:

# route add default gw 172.16.12.1The destination is default,

and the gateway address (172.16.12.1) is crab’s

address. Now crab is

rodent’s default gateway. Notice that the command

syntax is slightly different from the Solaris route example shown earlier.

rodent is a Linux system. Most values on the Linux route command line are preceded by keywords.

In this case, the gateway address is preceded by the keyword gw.

After installing the default route, examine the routing table to make sure the route has been added:[72]

# route -n

Kernel IP routing table

Destination Gateway Genmask Flags Metric Ref Use Iface

172.16.12.0 0.0.0.0 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth0

127.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 255.0.0.0 U 0 0 0 lo

0.0.0.0 172.16.12.1 0.0.0.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0Try ping again to see whether

rodent can now communicate with remote hosts. If we’re

lucky,[73] the remote host responds and we see:

% ping 207.25.98.2

PING 207.25.98.2: 56 data bytes

64 bytes from ruby.ora.com (207.25.98.2): icmp_seq=0. time=110. ms

64 bytes from ruby.ora.com (207.25.98.2): icmp_seq=1. time=100. ms

^C

----207.25.98.2 PING Statistics----

2 packets transmitted, 2 packets received, 0% packet loss

round-trip (ms) min/avg/max = 100/105/110This display indicates successful communication with the remote host, which means that we now have a good route to hosts on the Internet.

However, we still haven’t installed routes to the rest of

books-net. If we ping a host on another subnet, something

interesting happens:

% ping 172.16.1.2 PING 172.16.1.2: 56 data bytes ICMP Host redirect from gateway crab.wrotethebook.com (172.16.12.1) to horseshoe.wrotethebook.com (172.16.12.3) for ora.wrotethebook.com (172.16.1.2) 64 bytes from ora.wrotethebook.com (172.16.1.2): icmp_seq=1. time=30. ms ^C ----172.16.1.2 PING Statistics---- 1 packets transmitted, 1 packets received, 0% packet loss round-trip (ms) min/avg/max = 30/30/30

rodent believes that all destinations are

reachable through its default route. Therefore, even data destined for

the other subnets is sent to crab. If

rodent sends data to crab

that should go through horseshoe,

crab sends an ICMP Redirect to

rodent telling it to use

horseshoe. (See Chapter 1 for a description of the ICMP

Redirect Message.) ping shows the

ICMP Redirect in action. The redirect has a direct

effect on the routing table:

# route -n

Kernel IP routing table

Destination Gateway Genmask Flags Metric Ref Use Iface

172.16.12.0 0.0.0.0 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth0

127.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 255.0.0.0 U 0 0 0 lo

0.0.0.0 172.16.12.1 0.0.0.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

172.16.1.2 172.16.12.3 255.255.255.0 UGHD 0 0 514 eth0The route with the D flag set was installed by the ICMP Redirect.

Some network managers take advantage of ICMP Redirects when

designing a network. All hosts are configured with a default route,

even those on networks with more than one gateway. The gateways

exchange routing information through routing protocols and redirect

hosts to the best gateway for a specific route. This type of routing,

which is dependent on ICMP Redirects, became popular because of

personal computers (PCs). Many PCs cannot run a routing protocol; some

early models did not have a route

command and were limited to a single default route. ICMP Redirects

were one way to support these clients. Also, this type of routing is

simple to configure and well suited for implementation through a

configuration server, as the same default route is used on every host.

For these reasons, some network managers encourage repeated ICMP

Redirects.

Other network administrators prefer to avoid ICMP Redirects and

to maintain direct control over the contents of the routing table. To

avoid redirects, specific routes can be installed for each subnet

using individual route

statements:

# route add -net 172.16.1.0 netmask 255.255.255.0 gw 172.16.12.3 # route add -net 172.16.6.0 netmask 255.255.255.0 gw 172.16.12.3 # route add -net 172.16.3.0 netmask 255.255.255.0 gw 172.16.12.3 # route add -net 172.16.9.0 netmask 255.255.255.0 gw 172.16.12.3

rodent is directly connected only to 172.16.12.0, so all gateways in its routing table have addresses that begin with 172.16.12. The finished routing table is shown below:

# route -n

Kernel IP routing table

Destination Gateway Genmask Flags Metric Ref Use Iface

172.16.6.0 172.16.12.3 255.255.255.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

172.16.3.0 172.16.12.3 255.255.255.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

172.16.12.0 0.0.0.0 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth0

172.16.1.0 172.16.12.3 255.255.255.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

172.16.9.0 172.16.12.3 255.255.255.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

127.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 255.0.0.0 U 0 0 0 lo

0.0.0.0 172.16.12.1 0.0.0.0 UG 0 0 0 eth0

172.16.1.2 172.16.12.3 255.255.255.0 UGHD 0 0 514 eth0The routing table we have constructed uses the default route

(through crab) to reach external networks, and

specific routes (through horseshoe) to reach

other subnets within books-net. Rerunning the

ping tests produces consistently

successful results. However, if any subnets are added to the network,

the routes to these new subnets must be manually added to the routing

table. Additionally, if the system is rebooted, all static routing

table entries are lost. Therefore, to use static routing, you must

ensure that the routes are re-installed each time your system

boots.

If you decide to use static routing, you need to make two modifications to your startup files:

Add the desired

routestatements to a startup file.Remove any statements from the startup file that run a routing protocol.

To add static routing to a startup script, you must first

select an appropriate script. On BSD and Linux systems, the script

rc.local is set aside for local modifications to the boot

process. rc.local runs at the end of the boot

process so it is a good place to put in changes that will modify the

default boot process. On our sample Red Hat Linux system, the full

path of the rc.local file is

/etc/rc.d/rc.local. On a Solaris system, edit

/etc/init.d/inetinit to add the route statements:

route -n add default 172.16.12.1 > /dev/console route -n add 172.16.1.0 172.16.12.3 > /dev/console route -n add 172.16.6.0 172.16.12.3 > /dev/console route -n add 172.16.3.0 172.16.12.3 > /dev/console route -n add 172.16.9.0 172.16.12.3 > /dev/console

The -n option tells

route to display numeric

addresses in its informational messages. When you add route commands to a Solaris startup file,

use the -n option to prevent

route from wasting time querying

name server software that may not be running. The -n option is not required on a Linux

system because Linux does not display informational messages when

installing a route.

After adding the route

commands, check whether the script starts a routing protocol. If it

does, comment out the lines that start it. You don’t want a routing

protocol running when you are using static routing. On our Solaris

sample system, the routing software is started only if the system

has more than one network interface (i.e., is a router) or the

/etc/gateways file has been created. (More on

this file later.) Neither of these things is true; therefore, the

routing daemon won’t be run by the startup process and we don’t have

to do anything except add the route statements.

Before making changes to your real system, check your system’s documentation. You may need to modify a different boot script, and the execution path of the routing daemon may be different. Only the documentation can provide the exact details you need.

Although the startup filename may be different on your system, the procedure should be basically the same. These simple steps are all you need to set up static routing. The problem with static routing is not setting it up, but maintaining it if you have a changeable networking environment. Routing protocols are flexible enough to handle simple and complex routing environments. That is why some startup procedures run routing protocols by default. However, most Unix systems need only a static default route. Routing protocols are usually needed only by routers.

Routing protocols are divided into two general groups: interior and exterior protocols. An interior protocol is a routing protocol used inside—interior to—an independent network system. In TCP/IP terminology, these independent network systems are called autonomous systems.[74] Within an autonomous system (AS), routing information is exchanged using an interior protocol chosen by the autonomous system’s administration.

All interior routing protocols perform the same basic functions. They determine the “best” route to each destination and distribute routing information among the systems on a network. How they perform these functions (in particular, how they decide which routes are best) is what makes routing protocols different from each other. There are several interior protocols:

The Routing Information Protocol (RIP) is the interior protocol most commonly used on Unix systems. RIP is included as part of the Unix software delivered with most systems. It is adequate for local area networks and is simple to configure. RIP selects the route with the lowest “hop count” (metric) as the best route. The RIP hop count represents the number of gateways through which data must pass to reach its destination. RIP assumes the best route is the one that uses the fewest gateways. This approach to route choice is called a distance-vector algorithm .

Hello is a protocol that uses delay as the deciding factor when choosing the best route. Delay is the length of time it takes a datagram to make the round trip between its source and destination. A Hello packet contains a timestamp indicating when it was sent. When the packet arrives at its destination, the receiving system subtracts the timestamp from the current time to estimate how long it took the packet to arrive. Hello is not widely used. It was the interior protocol of the original 56 Kbps NSFNET backbone and has had very little use otherwise.

Intermediate System to Intermediate System (IS-IS) is an interior routing protocol from the OSI protocol suite. It is a Shortest Path First (SPF) link-state protocol. It was the interior routing protocol used on the T1 NSFNET backbone, and it is still used by some large service providers.

Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) is another link-state protocol developed for TCP/IP. It is suitable for very large networks and provides several advantages over RIP.

Of these protocols, we will discuss RIP and OSPF in detail. OSPF is widely used on routers. RIP is widely used on Unix systems. We will start the discussion with RIP.

As delivered with many Unix systems, Routing Information Protocol

(RIP) is run by the routing daemon routed (pronounced “route” “d”). When

routed starts, it issues a request for routing updates and

then listens for responses to its request. When a system configured to

supply RIP information hears the request, it responds with an update

packet based on the information in its routing table. The update

packet contains the destination addresses from the routing table and

the routing metric associated with each destination. Update packets

are issued in response to requests as well as periodically to keep

routing information accurate.

To build the routing table, routed uses

the information in the update packets. If the routing update contains

a route to a destination that does not exist in the local routing

table, the new route is added. If the update describes a route whose

destination is already in the local table, the new route is used only

if it is a better route. As noted previously, RIP considers a route

with a lower " hop count” to be a better route. In RIP terminology, the

hop count is called the cost of the route or the

routing metric. We saw earlier that the routing

metric in the local routing table can be manually controlled using the

metric argument of the route

command. To select the best route, RIP must first determine the cost

of the route. The cost of a route is determined by adding the cost of

reaching the gateway that sent the update to the metric contained in

the RIP update packet. If the total cost is less than the cost of the

current route, the new route is used.

RIP also deletes routes from the routing table. It accomplishes this in two ways. First, if the gateway to a destination says the cost of the route is greater than 15, the route is deleted. Second, RIP assumes that a gateway that doesn’t send updates is dead. All routes through a gateway are deleted if no updates are received from that gateway for a specified time period. In general, RIP issues routing updates every 30 seconds. In many implementations, if a gateway does not issue routing updates for 180 seconds, all routes through that gateway are deleted from the routing table.

To run RIP using the routing daemon (routed),[75] enter the following command:

# routedThe routed statement is

often used without any command-line arguments, but you may want to

use the -q option. The -q option prevents routed from advertising routes. It just

listens to the routes advertised by other systems. If your computer

is not a gateway, you should probably use the -q option.

In the section on static routing, we did not need to comment

out the routed statement found in

the inetinit startup file because Solaris runs

routed only if the system has two

network interfaces or if the /etc/gateways file

is found. If your Unix system starts routed unconditionally, no action is

required to run RIP; just boot your system and RIP will run.

Otherwise, you need to make sure the routed command is in your startup and the

conditions required by your system are met. The easiest way to get

Solaris to run routed is to create a

gateways file—even an empty one will do.

routed reads

/etc/gateways at startup and adds its

information to the routing table. routed can build a functioning routing

table simply by using the RIP updates received from the RIP

suppliers. However, it is sometimes useful to supplement this

information with, for example, an initial default route or

information about a gateway that does not announce its routes. The

/etc/gateways file stores this additional

routing information.

The most common use of the /etc/gateways file is to define an active default route, so we’ll use that as an example. This one example is sufficient because all entries in the /etc/gateways file have the same basic format. The following entry specifies crab as the default gateway:

net 0.0.0.0 gateway 172.16.12.1 metric 1 active

The entry starts with the keyword net. All entries

start with either the keyword net

or the keyword host to indicate

whether the address that follows is a network address or a host

address. The destination address 0.0.0.0 is the address used for the

default route. In the route

command we used the keyword default to indicate this route, but in

/etc/gateways the default route is indicated by

network address 0.0.0.0.

Next is the keyword gateway

followed by the gateway’s IP address. In this case it is the address

of crab (172.16.12.1).

Then comes the keyword metric followed by

a numeric metric value. The metric is the cost of the route. The

metric was almost meaningless when used with static routing, but now

that we are running RIP, the metric is used to make routing

decisions. The RIP metric represents the number of gateways through

which data must pass to reach its final destination. But as we saw

with ifconfig, the metric is

really an arbitrary value used by the administrator to prefer one

route over another. (The system administrator is free to assign any

metric value.) However, it is useful to vary the metric only if you

have more than one route to the same destination. With only one

gateway to the Internet, the correct metric to use for

crab is 1.

All /etc/gateways entries end with either

the keyword passive or the keyword active . “Passive” means the gateway listed in the entry is

not required to provide RIP updates. Use passive to prevent RIP from deleting the

route if no updates are expected from the gateway. A passive route

is placed in the routing table and kept there as long as the system

is up. In effect, it becomes a permanent static route.

The keyword active, on the

other hand, creates a route that can be updated by RIP. An active

gateway is expected to supply routing information and will be

removed from the routing table if, over a period of time, it does

not provide routing updates. Active routes are used to “prime the

pump” during the RIP startup phase, with the expectation that the

routes will be updated by RIP when the protocol is up and

running.

Our sample entry ends with the keyword active, which means that this default

route will be deleted if no routing updates are received from

crab. Default routes are convenient; this is

especially true when you use static routing. But when you use

dynamic routing, default routes should be used with caution,

especially if you have multiple gateways that can reach the same

destination. A passive default route prevents the routing protocol

from dynamically updating the route to reflect changing network

conditions. Use an active default route that can be updated by the

routing protocol.

RIP is easy to implement and simple to configure. Perfect! Well, not quite. RIP has three serious shortcomings:

- Limited network diameter

The longest RIP route is 15 hops. A RIP router cannot maintain a complete routing table for a network that has destinations more than 15 hops away. The hop count cannot be increased because of the second shortcoming.

- Slow convergence

Deleting a bad route sometimes requires the exchange of multiple routing update packets until the route’s cost reaches 16. This is called “counting to infinity” because RIP keeps incrementing the route’s cost until it becomes greater than the largest valid RIP metric. (In this case, 16 is infinity.) Additionally, RIP may wait 180 seconds before deleting the invalid routes. In network-speak, we say that these conditions delay the “convergence of routing,” i.e., it takes a long time for the routing table to reflect the current state of the network.

- Classful routing

RIP interprets all addresses using the class rules described in Chapter 2. For RIP, all addresses are class A, B, or C, which makes RIP incompatible with the current practice of interpreting an address based on the address bit mask.

Nothing can be done to change the limited network diameter. A small metric is essential to reduce the impact of counting to infinity. However, limited network size is the least important of RIP’s shortcomings. The real work of improving RIP concentrates on the other two problems, slow convergence and classful routing.

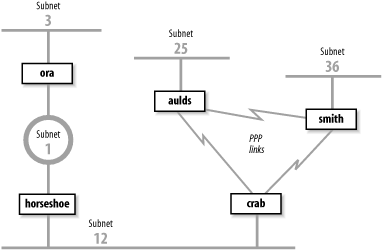

Features have been added to RIP to address slow convergence. Before discussing them we must understand how the “counting-to-infinity” problem occurs. Figure 7-2 illustrates a network where a counting-to-infinity problem might happen.

Figure 7-2 shows that crab reaches subnet 3 through horseshoe and then through ora. Subnet 3 is two hops away from crab and one hop away from horseshoe. Therefore horseshoe advertises a cost of 1 for subnet 3 and crab advertises a cost of 2, and traffic continues to be routed through horseshoe. That is, until something goes wrong. If ora crashes, horseshoe waits for an update from ora for 180 seconds. While waiting, horseshoe continues to send updates to crab that keep the route to subnet 3 in crab’s routing table. When horseshoe’s timer finally expires, it removes all routes through ora from its routing table, including the route to subnet 3. It then receives an update from crab advertising that crab is two hops away from subnet 3. horseshoe installs this route and announces that it is three hops away from subnet 3. crab receives this update, installs the route, and announces that it is four hops away from subnet 3. Things continue on in this manner until the cost of the route to subnet 3 reaches 16 in both routing tables. If the update interval is 30 seconds, this could take a long time!

Split horizon and poison reverse are two features that attempt to avoid counting to infinity. Here’s how:

- Split horizon

With this feature, a router does not advertise routes on the link from which those routes were obtained. This would solve the count-to-infinity problem described above. Using the split horizon rule, crab would not announce the route to subnet 3 on subnet 12 because it learned that route from the updates it received from horseshoe on subnet 12. While this feature works for the previous example described, it does not work for all count-to-infinity configurations. (More on this later.)

- Poison reverse

This feature is an enhancement of split horizon. It uses the same idea: “Don’t advertise routes on the link from which those routes were obtained.” But it adds a positive action to that essentially negative rule. Poison reverse says that a router should advertise an infinite distance for routes on this link. With poison reverse, crab would advertise subnet 3 with a cost of 16 to all systems on subnet 12. The cost of 16 means that subnet 3 cannot be reached through crab.

Split horizon and poison reverse solve the problem described above. But what happens if crab crashes? Refer to Figure 7-2. With split horizon, aulds and smith do not advertise to crab the route to subnet 12 because they learned the route from crab. They do, however, advertise the route to subnet 12 to each other. When crab goes down, aulds and smith perform their own count to infinity before they remove the route to subnet 12. Triggered updates address this problem.

Triggered updates are a big improvement. Instead of waiting the normal 30-second update interval, a triggered update is sent immediately. Therefore, when an upstream router crashes or a local link goes down, the router sends the changes to its neighbors immediately after it updates its local routing table. Without triggered updates, counting to infinity can take almost eight minutes! With triggered updates, neighbors are informed in a few seconds. Triggered updates also use network bandwidth efficiently. They don’t include the full routing table; they include only the routes that have changed.

Triggered updates take positive action to eliminate bad routes. Using triggered updates, a router advertises the routes deleted from its routing table with an infinite cost to force downstream routers to also remove them. Again, look at Figure 7-2. If crab crashes, smith and aulds wait 180 seconds and remove the routes to subnets 1, 3, and 12 from their routing tables. They then send each other triggered updates with a metric of 16 for subnets 1, 3, and 12. Thus they tell each other that they cannot reach these networks and no count to infinity occurs. Split horizon, poison reverse, and triggered updates go a long way toward eliminating counting to infinity.

It is the final shortcoming—the fact that RIP is incompatible with CIDR supernets and variable-length subnets—that caused the RIP protocol to be moved to “historical” status in 1996. RIP is not compatible with current and future plans for the TCP/IP protocol stack. A new version of RIP had to be created to address this final problem.

RIP version 2 (RIP-2), defined in RFC 2453, is a new version of RIP. It is not a completely new protocol; it simply defines extensions to the RIP packet format. RIP-2 adds a network mask and a next-hop address to the destination address and metric found in the original RIP packet.

The network mask frees the RIP-2 router from the limitation of interpreting addresses based on outdated address class rules. The mask is applied to the destination address to determine how the address should be interpreted. Using the mask, RIP-2 routers support variable-length subnets and CIDR supernets.

The next-hop address is the IP address of the gateway that handles the route. If the address is 0.0.0.0, the source of the update packet is the gateway for the route. The next-hop route permits a RIP-2 supplier to provide routing information about gateways that do not speak RIP-2. Its function is similar to an ICMP Redirect, pointing to the best gateway for a route and eliminating extra routing hops.

RIP-2 adds other new features to RIP. It transmits updates via the multicast address 224.0.0.9 to reduce the load on systems that are not capable of processing a RIP-2 packet. RIP-2 also introduces a packet authentication scheme to reduce the possibility of accepting erroneous updates from misconfigured systems.

Despite these changes, RIP-2 is compatible with RIP. The original RIP specification allowed for future versions of RIP. RIP has a version number in the packet header, and several empty fields for extending the packet. The new values used by RIP-2 did not require any changes to the structure of the packet. The new values are simply placed in the empty fields that the original protocol reserved for future use. Properly implemented RIP routers can receive RIP-2 packets and extract the data that they need from the packet without becoming confused by the new data.

Split horizon, poison reverse, triggered updates, and RIP-2 eliminate most of the problems with the original RIP protocol. But RIP-2 is still a distance-vector protocol. There are other, newer routing technologies that are considered superior for large networks. In particular, link-state routing protocols are favored because they provide rapid routing convergence and reduce the possibility of routing loops.

Open Shortest Path First (OSPF), defined by RFC 2328, is a link-state protocol. As such, it is very different from RIP. A router running RIP shares information about the entire network with its neighbors. Conversely, a router running OSPF shares information about its neighbors with the entire network. The “entire network” means, at most, a single autonomous system. RIP doesn’t try to learn about the entire Internet, and OSPF doesn’t try to advertise to the entire Internet. That’s not their job. These are interior routing protocols, so their job is to construct the routing inside an autonomous system. OSPF further refines this task by defining a hierarchy of routing areas within an autonomous system:

- Areas

An area is an arbitrary collection of interconnected networks, hosts, and routers. Areas exchange routing information with other areas within the autonomous system through area border routers.

- Backbone

A backbone is a special area that interconnects all of the other areas within an autonomous system. Every area must connect to the backbone because the backbone is responsible for distributing routing information between the areas.

- Stub area

A stub area has only one area border router, which means that there is only one route out of the area. In this case, the area border router does not need to advertise external routes to the other routers within the stub area. It can simply advertise itself as the default route.

Only a large autonomous system needs to be subdivided into areas. The sample network shown in Figure 7-2 is small and would not need to be divided. We can, however, use it to illustrate the different areas. We could divide this autonomous system into any areas we wish. Assume we divide it into three areas: area 1 contains subnet 3; area 2 contains subnet 1 and subnet 12; and area 3 contains subnet 25, subnet 36, and the PPP links. Furthermore, we could define area 1 as a stub area because ora is that area’s only area border router. We also could define area 2 as the backbone area because it interconnects the other two areas and all routing information between areas 1 and 3 must be distributed by area 2. Area 2 contains two area border routers, crab and ora, and one interior router, horseshoe. Area 3 contains three routers: crab, smith, and aulds.

Clearly OSPF provides lots of flexibility for subdividing an autonomous system. But why is it necessary? One problem for a link-state protocol is the large quantity of data that can be collected in the link-state database and the amount of time it can take to calculate the routes from that data. A look at the protocol shows why this is true.

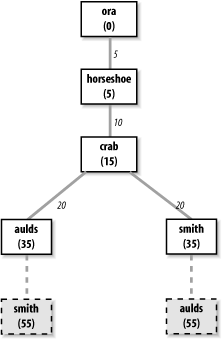

Every OSPF router builds a directed graph of the entire network using the Dijkstra Shortest Path First (SPF) algorithm. A directed graph is a map of the network from the perspective of the router; that is, the root of the graph is the router. The graph is built from the link-state database, which includes information about every router on the network and all the neighbors of every router. The link-state database for the autonomous system in Figure 7-2 contains 5 routers and 10 neighbors: ora has 1 neighbor, horseshoe; horseshoe has 2 neighbors, ora and crab; crab has 3 neighbors, horseshoe, aulds, and smith; aulds has 2 neighbors, crab and smith; and smith has 2 neighbors, aulds and crab. Figure 7-3 shows the graph of this autonomous system from the perspective of ora.

The Dijkstra algorithm builds the map in this manner:

Install the local system as the root of the map with a cost of 0.

Locate the neighbors of the system just installed and add them to the map. The cost of reaching the neighbors is calculated as the sum of the cost of reaching the system just installed plus the cost it advertises for reaching each neighbor. For example, assume that crab advertises a cost of 20 for aulds and that the cost of reaching crab is 15. Then the cost for aulds in ora’s map is 35.

Walk through the map and select the lowest-cost path for each destination. For example, when aulds is added to the map, its neighbors include smith. The path to smith through aulds is temporarily added to the map. In this third phase of the algorithm, the cost of reaching smith through crab is compared to the cost of reaching it through aulds. The lowest-cost path is selected. Figure 7-3 shows the deleted paths in dotted lines. Steps 2 and 3 of the algorithm are repeated for every system in the link-state database.

The information in the link-state database is gathered and distributed in a simple and efficient manner. An OSPF router discovers its neighbors through the use of Hello packets.[76] It sends Hello packets and listens for Hello packets from adjacent routers. The Hello packet identifies the local router and lists the adjacent routers from which it has received packets. When a router receives a Hello packet that lists it as an adjacent router, it knows it has found a neighbor. It knows this because it can hear packets from that neighbor and, because the neighbor lists it as an adjacent router, the neighbor must be able to hear packets from it. The newly discovered neighbor is added to the local system’s neighbor list.

The OSPF router then advertises all of its neighbors. It does this by flooding a Link-State Advertisement (LSA) to the entire network. The LSA contains the address of every neighbor and the cost of reaching that neighbor from the local system. Flooding means that the router sends the LSA out of every interface and that every router that receives the LSA sends it out of every interface except the one from which it was received. To avoid flooding duplicate LSAs, the routers store a copy of the LSAs they receive and discard duplicates.

Figure 7-2 provides an example. When OSPF starts on horseshoe it sends a Hello packet on subnet 1 and one on subnet 12. ora and crab hear the Hello and respond with Hello packets that list horseshoe as an adjacent router. horseshoe hears their Hello packets and adds them to its neighbor list. horseshoe then creates an LSA that lists ora and crab as neighbors with appropriate costs assigned to each. For instance, horseshoe might assign a cost of 5 to ora and a cost of 10 to crab. horseshoe then floods the LSA on subnet 1 and subnet 12. ora hears the LSA and floods it on subnet 3. crab receives the LSA and floods it on both of its PPP links. aulds floods the LSA on the link toward smith, and smith floods it on the same link to aulds. When aulds and smith received the second copy of the LSA, they discarded it because it duplicated one that they had already received from crab. In this manner, every router in the entire network receives every other router’s link-state advertisement.

OSPF routers track the state of their neighbors by listening for Hello packets. Hello packets are issued by all routers on a periodic basis. When a router stops issuing packets, it or the link it is attached to is assumed to be down. Its neighbors update their LSA and flood them through the network. The new LSAs are included into the link-state database on every router on the network, and every router recalculates its network map based on this new information. Clearly, limiting the number of routers by limiting the size of the network reduces the burden of recalculating the map. For many networks, the entire autonomous system is small enough. For others, dividing the autonomous system into areas improves efficiency.

Another feature of OSPF that improves efficiency is the designated router . The designated router is one router on the network that treats all other routers on the network as its neighbors, while all other routers treat only the designated router as their neighbor. This helps reduce the size of the link-state database and thus improves the speed of the Shortest-Path-First calculation. Imagine a broadcast network with 5 routers. Five routers each with 4 neighbors produce a link-state database with 20 entries. But if one of those routers is the designated router, then that router has 4 neighbors and all other routers have only 1 neighbor, for a total of 10 link-state database entries. While there is no need for a designated router on such a small network, the larger the network, the more dramatic the gains. For example, a broadcast network with 25 routers has a link-state database of 50 entries when a designated router is used, versus a database of 600 entries without one.

OSPF provides the router with an end-to-end view of the route between two systems instead of the limited next-hop view provided by RIP. Flooding quickly disseminates routing information throughout the network. Limiting the size of the link-state database through areas and designated routers speeds the SPF calculation. Taken altogether, OSPF is an efficient link-state routing protocol.

OSPF also offers additional features that RIP doesn’t. It provides simple password authentication to ensure that the update comes from a valid router using an eight-character, clear-text password. It provides Message Digest 5 (MD5) crypto-checksum for stronger authentication.

OSPF also supports equal-cost multi-path routing . This mouthful means that OSPF routers can maintain more than one path to a single destination. Given the proper conditions, this feature can be used for load balancing across multiple network links. However, many systems are not designed to take advantage of this feature. Refer to your router’s documentation to see if it supports load balancing across equal-cost OSPF routes.

With all of these features, OSPF is the preferred TCP/IP interior routing protocol for dedicated routers.

Exterior routing protocols are used to exchange routing information between autonomous systems. The routing information passed between autonomous systems is called reachability information . Reachability information is simply information about which networks can be reached through a specific autonomous system.

RFC 1771 defines Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), the leading exterior routing protocol, and provides the following description of the routing function of an autonomous system:

The classic definition of an Autonomous System is a set of routers under a single technical administration, using an interior gateway protocol and common metrics to route packets within the AS, and using an exterior gateway protocol to route packets to other ASs.... The administration of an AS appears to other ASs to have a single coherent interior routing plan and presents a consistent picture of what networks are reachable through it. From the standpoint of exterior routing, an AS can be viewed as monolithic...

Moving routing information into and out of these monoliths is the function of exterior routing protocols. Exterior routing protocols are also called exterior gateway protocols. Don’t confuse an exterior gateway protocol with the Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP). EGP is not a generic term; it is a particular exterior routing protocol, and an old one at that.

A gateway running EGP announces that it can reach networks that are part of its autonomous system. It does not announce that it can reach networks outside its autonomous system. For example, the exterior gateway for our imaginary autonomous system book-as can reach the entire Internet through its external connection, but only one network is contained in its autonomous system. Therefore, it would announce only one network (172.16.0.0) if it ran EGP.

Before sending routing information, the systems exchange EGP Hello and I-Heard-You (I-H-U) messages. These messages establish a dialogue between two EGP gateways. Computers communicating via EGP are called EGP neighbors, and the exchange of Hello and I-H-U messages is called acquiring a neighbor .

Once a neighbor is acquired, routing information is requested via a poll . The neighbor responds by sending a packet of reachability information called an update. The local system includes the routes from the update into its local routing table. If the neighbor fails to respond to three consecutive polls, the system assumes that the neighbor is down and removes the neighbor’s routes from its table. If the system receives a poll from its EGP neighbor, it responds with its own update packet.

Unlike the interior protocols discussed above, EGP does not attempt to choose the “best” route. EGP updates contain distance-vector information, but EGP does not evaluate this information. The routing metrics from different autonomous systems are not directly comparable. Each AS may use different criteria for developing these values. Therefore, EGP leaves the choice of a “best” route to someone else.

When EGP was designed, the network relied upon a group of trusted core gateways to process and distribute the routes received from all of the autonomous systems. These core gateways were expected to have the information necessary to choose the best external routes. EGP reachability information was passed into the core gateways, where the information was combined and passed back out to the autonomous systems.

A routing structure that depends on a centrally controlled group of gateways does not scale well and is therefore inadequate for the rapidly growing Internet. As the number of autonomous systems and networks connected to the Internet grew, it became difficult for the core gateways to keep up with the expanding workload. This is one reason why the Internet moved to a more distributed architecture that places a share of the burden of processing routes on each autonomous system. Another reason is that no central authority controls the commercialized Internet. The Internet is composed of many equal networks. In a distributed architecture, the autonomous systems require routing protocols, both interior and exterior, that can make intelligent routing choices. Because of this, EGP is no longer popular.

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is the leading exterior routing protocol of the Internet. It is based on the OSI InterDomain Routing Protocol (IDRP). BGP supports policy-based routing, which uses non-technical reasons (for example, political, organizational, or security considerations) to make routing decisions. Thus BGP enhances an autonomous system’s ability to choose between routes and to implement routing policies without relying on a central routing authority. This feature is important in the absence of core gateways to perform these tasks.

Routing policies are not part of the BGP protocol. Policies

are provided externally as configuration information. As

described in Chapter 2, the National

Science Foundation provides Routing Arbiters (RAs) at the Network

Access Points (NAPs) where large Internet Service Providers (ISPs)

interconnect. The RAs can be queried for routing policy information.

Most ISPs also develop private policies based on the bilateral

agreements they have with other ISPs. BGP can be used to implement

these policies by controlling the routes it announces to others and

the routes it accepts from others. In the gated section later in this chapter, we

discuss the import command and the

export command, which control what

routes are accepted (import) and what routes are announced (export).

The network administrator enforces the routing policy through

configuring the router.

BGP is implemented on top of TCP, which provides BGP with a reliable delivery service. BGP uses well-known TCP port 179. It acquires its neighbors through the standard TCP three-way handshake. BGP neighbors are called peers. Once connected, BGP peers exchange OPEN messages to negotiate session parameters, such as the version of BGP that is to be used.

The UPDATE message lists the destinations that can be reached through a specific path and the attributes of the path. BGP is a path-vector protocol. It is called a path-vector protocol because it provides the entire end-to-end path of a route in the form of a sequence of autonomous system numbers. Having the complete AS path eliminates the possibility of routing loops and count-to-infinity problems. A BGP UPDATE contains a single path vector and all of the destinations reachable through that path. Multiple UPDATE packets may be sent to build a routing table.

BGP peers send each other complete routing table updates when the connection is first established. After that, only changes are sent. If there are no changes, just a small (19-byte) KEEPALIVE message is sent to indicate that the peer and the link are still operational. BGP is very efficient in its use of network bandwidth and system resources.

By far the most important thing to remember about exterior protocols is that most systems never run them. Exterior protocols are required only when an AS must exchange routing information with another AS. Most routers within an AS run an interior protocol such as OSPF. Only those gateways that connect the AS to another AS need to run an exterior routing protocol. Your network is probably an independent part of an AS run by someone else. ISPs are good examples of autonomous systems made up of many independent networks. Unless you provide a similar level of service, you probably don’t need to run an exterior routing protocol.

Although there are many routing protocols, choosing one is usually easy. Most of the interior routing protocols mentioned above were developed to handle the special routing problems of very large networks. Some of the protocols have been used only by large national and regional networks. For local area networks, RIP is still a common choice. For larger networks, OSPF is the choice.

If you must run an exterior routing protocol, the protocol that you use is often not a matter of choice. For two autonomous systems to exchange routing information, they must use the same exterior protocol. If the other AS is already in operation, its administrators have probably decided which protocol to use, and you will be expected to conform to their choice. Most often this choice is BGP.

The type of equipment affects the choice of protocols. Routers

support a wide range of protocols, though individual vendors may have

a preferred protocol. Hosts don’t usually run routing protocols at

all, and most Unix systems are delivered with only RIP. Allowing host

systems to participate in dynamic routing could limit your choices.

gated, however, gives you the

option to run many different routing protocols on a Unix system. While

the performance of hardware designed specifically to be a router is

generally better, gated gives you

the option of using a Unix system as a router.

In the following sections we discuss the Gateway Routing Daemon

(gated) software that combines

interior and exterior routing protocols into one software package. We

look at examples of running RIP, RIPv2, OSPF, and BGP with gated.

Routing software development for general-purpose Unix systems is limited.

Most sites use Unix systems only for simple routing tasks for which RIP

is usually adequate. Large and complex routing applications, which

require advanced routing protocols, are handled by dedicated router

hardware that is optimized specifically for routing. Many of the

advanced routing protocols are only available for Unix systems in

gated. gated combines several different routing

protocols in a single software package.

Additionally, gated provides

other features that are usually associated only with dedicated

routers:

Systems can run more than one routing protocol.

gatedcombines the routing information learned from different protocols and selects the “best” routes.Routes learned through an interior routing protocol can be announced via an exterior routing protocol, which allows the reachability information announced externally to adjust dynamically to changing interior routes.

Routing policies can be implemented to control what routes are accepted and what routes are advertised.

All protocols are configured from a single file (/etc/gated.conf) using a single consistent syntax for the configuration commands.

gatedis constantly being upgraded. Usinggatedensures that you’re running the most up-to-date routing software.

There are two sides to every routing protocol implementation. One side, the external side, exchanges routing information with remote systems. The other side, the internal side, uses the information received from the remote systems to update the routing table. For example, when OSPF exchanges Hello packets to discover a neighbor, it is an external protocol function. When OSPF adds a route to the routing table, it is an internal function.

The external protocol functions implemented in gated are the same as those in other

implementations of the protocols. However, the internal side of

gated is unique for Unix systems.

Internally, gated processes routing

information from different routing protocols, each of which has its

own metric for determining the best route, and combines that

information to update the routing table. Before gated was written, if a Unix system ran

multiple routing protocols, each would write routes into the routing

table without knowledge of the others’ actions. The route found in the

table was the last one written—not necessarily the best route.

With multiple routing protocols and multiple network interfaces,

it is possible for a system to receive routes to the same destination

from different protocols. gated

compares these routes and attempts to select the best one. However,

the metrics used by different protocols are not directly comparable.

Each routing protocol has its own metric. It might be a hop count, the

delay on the route, or an arbitrary value set by the administrator.

gated needs more than that

protocol’s metric to select the best route. It uses its own value to

prefer routes from one protocol or interface over another. This value

is called preference.

Preference values help gated

combine routing information from several different sources into a

single routing table. Table

7-1 lists the sources from which gated receives routes and the default

preference given to each source. Preference values range from 0 to

255, with the lowest number indicating the most preferred route. From

this table you can see that gated

prefers a route learned from OSPF over the same route learned from

BGP.

Table 7-1. Default preference values

Route type | Default preference |

|---|---|

direct route | 0 |

OSPF | 10 |

IS-IS Level 1 | 15 |

IS-IS Level 2 | 18 |

Internally generated default | 20 |

ICMP redirect | 30 |

Routes learned from the route socket | 40 |

static route | 60 |

SLSP routes | 70 |

RIP | 100 |

Point-to-Point interface routes | 110 |

Routes through a downed interface | 120 |

Aggregate and generate routes | 130 |

OSPF ASE routes | 150 |

BGP | 170 |

EGP | 200 |

Preference can be set in several different configuration

statements. It can be used to prefer routes from one network interface

over another, from one protocol over another, or from one remote

gateway over another. Preference values are not transmitted or

modified by the protocols. Preference is used only in the

configuration file. In the next section we’ll look at the gated configuration file

(/etc/gated.conf) and the configuration commands

it contains.

gated is available from http://www.gated.org. Appendix B provides information about

downloading and compiling the software. In this section, we use gated release 3.6, the version of gated that is currently available without

restrictions. There are other versions of gated available to members of the Gated

Consortium. If you plan to build products based on gated or do research on routing protocols

using gated, you should join the

consortium. For the purposes of this book, release 3.6 is fine.

gated reads its configuration

from the /etc/gated.conf file. The configuration commands in the file resemble C

code. All statements end with a semicolon, and associated statements are

grouped together by curly braces. This structure makes it simple to see

what parts of the configuration are associated with each other, which is

important when multiple protocols are configured in the same file. In

addition to structure in the language, the

/etc/gated.conf file also has a structure.

The different configuration statements, and the order in which these statements must appear, divide gated.conf into sections: option statements, interface statements, definition statements, unicast and multicast protocol statements, static statements, control statements, and aggregate statements. Entering a statement out of order causes an error when parsing the file.

Two other types of statements do not fall into any of these categories. They are directive statements and trace statements. These can occur anywhere in the gated.conf file and do not directly relate to the configuration of any protocol. These statements provide instructions to the parser and instructions to control tracing from within the configuration file.

The gated configuration

commands are summarized in Table

7-2. The table lists each command by name, identifies the

statement type, and provides a very short synopsis of each command’s

function. The entire command language is covered in detail in Appendix B.

Table 7-2. gated configuration statements

Statement | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

%directory | directive | Sets the directory for include files |

%include | directive | Includes a file into gated.conf |

traceoptions | trace | Specifies which events are traced |

options | option | Defines gated options |

interfaces | interface | Defines interface options |

autonomoussystem | definition | Defines the AS number |

routerid | definition | Defines the originating router for BGP or OSPF |

martians | definition | Defines invalid destination addresses |

multicast | protocol | Defines multicast protocol options |

snmp | protocol | Enables reporting to SNMP |

rip | protocol | Enables RIP |

isis | protocol | Enables IS-IS protocol |

kernel | protocol | Configures kernel interface options |

ospf | protocol | Enables OSPF protocol |

redirect | protocol | Removes routes installed by ICMP |

egp | protocol | Enables EGP |

bgp | protocol | Enables BGP |

icmp | protocol | Configures the processing of general ICMP packets |

pim | protocol | Enables the PIM multicast protocol |

dvmrp | protocol | Enables the DVMRP multicast protocol |

msdp | protocol | Enables the MSDP multicast protocol |

static | static | Defines static routes |

import | control | Defines what routes are accepted |

export | control | Defines what routes are advertised |

aggregate | aggregate | Controls route aggregation |

generate | aggregate | Controls creation of a default route |

You can see that the gated

configuration language has many commands. The language provides

configuration control for several different protocols and additional

commands to configure the added features of gated itself. All of this can be

confusing.

To avoid confusion, don’t try to understand the details of

everything offered by gated. Your

routing environment will not use all of these protocols and features.

Even if you are providing the gateway at the border between two

anonymous systems, you will probably run only two routing protocols: one

interior protocol and one exterior protocol. Only those commands that

relate to your actual configuration need to be included in your

configuration file. As you read this section, skip the things you don’t

need. For example, if you don’t use the BGP protocol, don’t study the

bgp statement. When you do need more

details about a specific statement, look it up in Appendix B. With this in mind, let’s look at

some sample

configurations.

The details in Appendix B may

make gated

configuration appear more complex than it is. gated’s rich command language can be

confusing, as can its support for multiple protocols and the fact that

it often provides a few ways to do the same thing. But some realistic

examples will show that individual configurations do not need to be

complex.

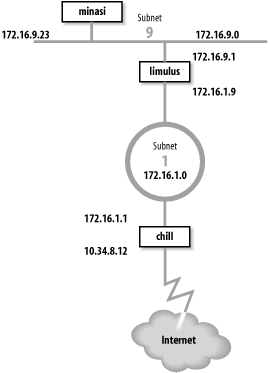

The basis for the sample configurations is the network in Figure 7-4. We have installed a new router that provides our backbone with direct access to the Internet, and we have decided to install new routing protocols. We’ll configure a host to listen to RIP-2 updates, an interior gateway to run RIP-2 and OSPF, and an exterior gateway to run OSPF and BGP.

Gateway limulus interconnects subnet 172.16.9.0 and subnet 172.16.1.0. To hosts on subnet 9, it advertises itself as the default gateway because it is the gateway to the outside world. It uses RIP-2 to advertise routes on subnet 9. On subnet 1, gateway limulus advertises itself as the gateway to subnet 9 using OSPF.

Gateway chill provides subnet 1 with access to the Internet through autonomous system 164. Because gateway chill provides access to the Internet, it announces itself as the default gateway to the other systems on subnet 1 using OSPF. To the external autonomous system, it uses BGP to announce itself as the path to the internal networks it learns about through OSPF.

Let’s look at the routing configuration of host minasi, gateway limulus, and gateway chill.

The host routing configuration is very simple. The rip yes

statement enables RIP, and that’s all that is really required to run

RIP. That basic configuration should work for any system that runs

RIP. The additional clauses enclosed in curly braces modify the

basic RIP configuration. We use a few clauses to create a more

interesting example. Here is the RIP-2 configuration for host

minasi:

#

# enable rip, don't broadcast updates,

# listen for RIP-2 updates on the multicast address,

# check that the updates are authentic.

#

rip yes {

nobroadcast ;

interface 172.16.9.23

version 2

multicast

authentication simple "REAL stuff" ;

} ;This sample file shows the basic structure of

gated.conf configuration statements. Lines

beginning with a sharp sign (#) are comments.[77] All statements end with semicolons. Clauses associated

with a configuration statement can span multiple lines and are

enclosed in curly braces ({}). In

the example, the nobroadcast and

interface clauses apply directly

to the rip statement. The

version, multicast, and authentication keywords are part of the

interface clause.

The keyword nobroadcast

prevents the host from broadcasting its own RIP updates. The default

is nobroadcast when the system

has one network interface, and broadcast when it has more than one. The

nobroadcast keyword performs the

same function as the -q

command-line option does for routed. However, gated can do much more than routed, as the next clause shows.

The interface clause

defines interface parameters for RIP. The parameters associated with

this clause say that RIP-2 updates will be received via the RIP-2

multicast address on interface 172.16.9.23 and that authentic

updates will contain the password REAL^stuff. For RIP-2, simple authentication is a clear-text

password up to 16 bytes long. This is not intended to protect the

system from malicious actions; it is intended only to protect the

routers from a configuration accident. If a user mistakenly sets his

system up as a RIP supplier, he is very unlikely to accidentally

enter the correct password into his configuration. Stronger

authentication is available in the form of a Message Digest 5 (MD5)

cryptographic checksum by specifying md5 in the authentication clause.

Gateway configurations are more complicated than the simple host configuration shown above. Gateways always have multiple interfaces and occasionally run multiple routing protocols. Our first sample configuration is for the interior gateway between subnet 9 and the central backbone, subnet 1. It uses RIP-2 on subnet 9 to announce routes to the Unix hosts. It uses OSPF on subnet 1 to exchange routes with the other gateways. Here’s the configuration of gateway limulus:

# Don't time-out subnet 9

interfaces {

interface 172.16.9.1 passive ;

} ;

# Define the OSPF router id

routerid 172.16.1.9 ;

# Enable RIP-2; announce OSPF routes to

# subnet 9 with a cost of 5.

rip yes {

broadcast ;

defaultmetric 5 ;

interface 172.16.9.1

version 2

multicast

authentication simple "REAL stuff" ;

} ;

# Enable OSPF; subnet 1 is the backbone area;

# use password authentication.

ospf yes {

backbone {

interface 172.16.1.9 {

priority 5 ;

auth simple "It'sREAL" ;

} ;

} ;

} ;The interfaces statement

defines routing characteristics for the network interfaces. The

keyword passive in the interface

clause is used here, just as we have seen it used before, to create

a permanent static route that will not be removed from the routing

table. In this case, the permanent route is through a directly

attached network interface. Normally when gated thinks an interface is

malfunctioning, it increases the cost of the interface by giving it

a high-cost preference value (120) to reduce the probability of a

gateway routing data through a non-operational interface. gated determines that an interface is

malfunctioning when it does not receive routing updates on that

interface. We don’t want gated to

downgrade the 172.16.9.1 interface, even if it does think the

interface is malfunctioning, because our router is the only path to

subnet 9. That’s why this configuration includes the clause interface 172.16.9.1 passive.

The routerid statement

defines the router identifier for OSPF. Unless it is explicitly

defined in the configuration file, gated uses the address of the first

interface it encounters as the default router identifier address.

Here we specify the address of the interface that actually speaks

OSPF as the OSPF router identifier.

In the previous example we discussed all the clauses on the

rip statement except one—the

defaultmetric clause. The

defaultmetric clause defines the

RIP metric used to advertise routes learned from other routing

protocols. This gateway runs both OSPF and RIP-2. We wish to

advertise the routes learned via OSPF to our RIP clients, and to do

that, a metric is required. We choose a RIP cost of 5. If the

defaultmetric clause is not used,

routes learned from OSPF are not advertised to the RIP

clients.[78] This statement is required for our

configuration.

The ospf yes statement enables OSPF. The first

clause associated with this statement is backbone. It states that the router is

part of the OSPF backbone area. Every ospf yes statement must have at least one associated area

clause. It can define a specific area, e.g., area 2, but at least one router must be in

the backbone area. While the OSPF backbone is area 0, it cannot be

specified as area 0; it must be specified with the keyword

backbone. In our sample

configuration, subnet 1 is the backbone, and all routers attached to

it are in the backbone area. It is possible for a single router to

attach to multiple areas with a different set of configuration

parameters for each area. Notice how the nested curly braces group

the clauses together. The remaining clauses in the configuration

file are directly associated with the backbone area clause.

The interface that connects this router to the backbone area

is defined by the interface

clause. It has two associated subclauses, the priority clause and the auth clause.

The priority 5 ; clause

defines the priority used by this router when the backbone is

electing a designated router. The higher the priority number, the

less likely a router will be elected as the designated router. Use

priority to steer the election

toward the most capable routers.

The auth simple "It'sREAL" ; clause says that simple, password-based

authentication is used in the backbone area and defines the password

used for simple authentication. Three choices, none, simple, and md5, are available for authentication in

GateD 3.6. none means no

authentication is used. simple

means that the correct eight-character password must be used or the

update will be rejected. Password authentication is used only to

protect against accidents; it is not intended to protect against

malicious actions. Stronger authentication based on MD5 is used

when md5 is selected.

The configuration for gateway chill is the most complex because it runs both OSPF and BGP. Here’s the configuration file for gateway chill:

# Defines our AS number for BGP

autonomoussystem 249;

# Defines the OSPF router id

routerid 172.16.1.1;

# Disable RIP

rip no;

# Enable BGP

bgp yes {

group type external peeras 164 {

peer 10.6.0.103 ;

peer 10.20.0.72 ;

};

};

# Enable OSPF; subnet 1 is the backbone area;

# use password authentication.

ospf yes {

backbone {

interface 172.16.1.1 {

priority 10 ;

auth simple "It'sREAL" ;

} ;

} ;

};

# Announce routes learned from OSPF and route

# to directly connected network via BGP to AS 164

export proto bgp as 164 {

proto direct ;

proto ospf ;

};

# Announce routes learned via BGP from

# AS number 164 to our OSPF area.

export proto ospfase type 2 {

proto bgp autonomoussystem 164 {

all ;

};

};This configuration enables both BGP and OSPF and sets certain

protocol-specific parameters. BGP needs to know the AS number, which

is 249 for books-net. OSPF needs to know the

router identifier address. We set it to the address of the router

interface that runs OSPF. The AS number and the router identifier

are defined early in the configuration because autonomoussystem and routerid are definition statements and

therefore must occur before the first protocol statement. Refer back

to Table 7-2 for the

various statement types.

The first protocol statement is the one that turns RIP off. We

don’t want to run RIP, but the default for gated is to turn RIP on. Therefore we

explicitly disable RIP with the rip no ; statement.

BGP is enabled by the bgp

yes statement, which also defines

a few additional BGP parameters. The group clause sets parameters for all of

the BGP peers in the group. The clause defines the type of BGP

connection being created. The example is a classic external routing

protocol connection, and the external autonomous system we are

connecting to is AS number 164. gated can create five different types of

BGP sessions, but only one, type external, is used to directly communicate with an external

autonomous system. The other four group types are used for

internal BGP (IBGP).[79] IBGP is simply an acronym for BGP when it is used to

move routing information around inside an autonomous system. In our

example we use it to move routing information between autonomous

systems.

The BGP neighbors from which updates are accepted are

indicated by the peer clauses. Each peer is a member of the group.

Everything related to the group, such as the AS number, applies to