Some network servers provide essential computer-to-computer services. These differ from application services in that they are not directly accessed by end users. Instead, these services are used by networked computers to simplify the installation, configuration, and operation of the network.

The functions performed by the servers covered in this chapter are varied:

Name service for converting IP addresses to hostnames

Configuration servers that simplify the installation of networked hosts by handling part or all of the TCP/IP configuration

Electronic mail services for moving mail through the network from the sender to the recipient

File servers that allow client computers to transparently share files

Print servers that allow printers to be centrally maintained and shared by all users

Servers on a TCP/IP network should not be confused with traditional PC LAN servers. Every Unix host on your network can be both a server and a client. The hosts on a TCP/IP network are “peers.” All systems are equal, and the network is not dependent on any one server. All of the services discussed in this chapter can be installed on one or several systems on your network.

We begin with a discussion of name service. It is an essential service that you will certainly use on your network.

The Internet Protocol document[17] defines names, addresses, and routes as follows:

A name indicates what we seek. An address indicates where it is. A route indicates how to get there.

Names, addresses, and routes all require the network administrator’s attention. Routes and addresses were covered in the previous chapter. This section discusses names and how they are disseminated throughout the network. Every network interface attached to a TCP/IP network is identified by a unique 32-bit IP address. A name (called a hostname) can be assigned to any device that has an IP address. Names are assigned to devices because, compared to numeric Internet addresses, names are easier to remember and type correctly. Names aren’t required by the network software, but they do make it easier for humans to use the network.

In most cases, hostnames and numeric addresses can be used interchangeably. A user wishing to telnet to the workstation at IP address 172.16.12.2 can enter:

% telnet 172.16.12.2or use the hostname associated with that address and enter the equivalent command:

% telnet rodent.wrotethebook.comWhether a command is entered with an address or a hostname, the network connection always takes place based on the IP address. The system converts the hostname to an address before the network connection is made. The network administrator is responsible for assigning names and addresses and storing them in the database used for the conversion.

Translating names into addresses isn’t simply a “local” issue. The

command telnet rodent.wrotethebook.com is expected to work correctly on every

host that’s connected to the network. If

rodent.wrotethebook.com is connected to the

Internet, hosts all over the world should be able to translate the name

rodent.wrotethebook.com into the proper address.

Therefore, some facility must exist for disseminating the hostname

information to all hosts on the network.

There are two common methods for translating names into addresses. The older method simply looks up the hostname in a table called the host table.[18] The newer technique uses a distributed database system called the Domain Name System (DNS) to translate names to addresses. We’ll examine the host table first.

The host table is a simple text file

that associates IP addresses with hostnames. On most Unix systems, the

table is in the file /etc/hosts. Each table entry in /etc/hosts

contains an IP address separated by whitespace from a list of hostnames

associated with that address. Comments begin with #.

The host table on rodent might contain the following entries:

# # Table of IP addresses and hostnames # 172.16.12.2 rodent.wrotethebook.com rodent 127.0.0.1 localhost 172.16.12.1 crab.wrotethebook.com crab loghost 172.16.12.4 jerboas.wrotethebook.com jerboas 172.16.12.3 horseshoe.wrotethebook.com horseshoe 172.16.1.2 ora.wrotethebook.com ora 172.16.6.4 linuxuser.articles.wrotethebook.com linuxuser

The first entry in the sample table is for rodent itself. The IP address 172.16.12.2 is associated with the hostname rodent.wrotethebook.com and the alternate hostname (or alias) rodent. The hostname and all of its aliases resolve to the same IP address, in this case 172.16.12.2.

Aliases provide for name changes, alternate spellings, and shorter

hostnames. They also allow for “generic hostnames.” Look at the entry

for 172.16.12.1. One of the aliases associated with that address is

loghost. loghost is a special hostname used

by Solaris in the syslog.conf configuration file. Some systems preconfigure programs

like syslogd to direct their output

to the host that has a certain generic name. You can direct the output

to any host you choose by assigning it the appropriate generic name as

an alias. Other commonly used generic hostnames are

lprhost, mailhost, and

dumphost.

The second entry in the sample file assigns the address 127.0.0.1 to the hostname localhost. As we have discussed, the network address 127.0.0.0/8 is reserved for the loopback network. The host address 127.0.0.1 is a special address used to designate the loopback address of the local host—hence the hostname localhost. This special addressing convention allows the host to address itself the same way it addresses a remote host. The loopback address simplifies software by allowing common code to be used for communicating with local or remote processes. This addressing convention also reduces network traffic because the localhost address is associated with a loopback device that loops data back to the host before it is written out to the network.

Although the host table system has been superseded by DNS, it is still widely used for the following reasons:

Most systems have a small host table containing name and address information about the important hosts on the local network. This small table is used when DNS is not running, such as during the initial system startup. Even if you use DNS, you should create a small /etc/hosts file containing entries for your host, for localhost, and for the gateways and servers on your local net.

Sites that use NIS use the host table as input to the NIS host database. You can use NIS in conjunction with DNS, but even when they are used together, most NIS sites create host tables that have an entry for every host on the local network. Chapter 9 explains how to use NIS with DNS.

Very small sites that are not connected to the Internet sometimes use the host table. If there are few local hosts and the information about those hosts rarely changes, and there is also no need to communicate via TCP/IP with remote sites, then there is little advantage to using DNS.

The old host table system is inadequate for the global Internet for two reasons: inability to scale and lack of an automated update process. Prior to the development of DNS, an organization called the Network Information Center (NIC) maintained a large table of Internet hosts called the NIC host table. Hosts included in the table were called registered hosts, and the NIC placed hostnames and addresses into this file for all sites on the Internet.

Even when the host table was the primary means of translating hostnames to IP addresses, most sites registered only a limited number of key systems. But even with limited registration, the table grew so large that it became an inefficient way to convert hostnames to IP addresses. There is no way that a simple table could provide adequate service for the enormous number of hosts on today’s Internet.

Another problem with the host table system is that it lacks a technique for automatically distributing information about newly registered hosts. Newly registered hosts can be referenced by name as soon as a site receives the new version of the host table. However, there is no way to guarantee that the host table is distributed to a site, and no way to know who had a current version of the table and who did not. This lack of guaranteed uniform distribution is a major weakness of the host table system.

DNS overcomes both major weaknesses of the host table:

DNS scales well. It doesn’t rely on a single large table; it is a distributed database system that doesn’t bog down as the database grows. DNS currently provides information on approximately 100,000,000 hosts, while fewer than 10,000 were listed in the host table.

DNS guarantees that new host information will be disseminated to the rest of the network as it is needed.

Information is automatically disseminated, and only to those who are interested. Here’s how it works. If a DNS server receives a request for information about a host for which it has no information, it passes on the request to an authoritative server. An authoritative server is any server responsible for maintaining accurate information about the domain being queried. When the authoritative server answers, the local server saves, or caches , the answer for future use. The next time the local server receives a request for this information, it answers the request itself. The ability to control host information from an authoritative source and to automatically disseminate accurate information makes DNS superior to the host table, even for networks not connected to the Internet.

In addition to superseding the host table, DNS also replaces an earlier form of name service. Unfortunately, both the old and new services were called name service. Both are listed in the /etc/services file. In that file, the old software is assigned UDP port 42 and is called nameserver or name; DNS name service is assigned port 53 and is called domain. Naturally, there is some confusion between the two name servers. There shouldn’t be—the old name service is outdated. This text discusses DNS only; when we refer to “name service,” we always mean DNS.

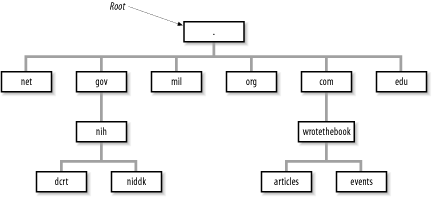

DNS is a distributed hierarchical system for resolving hostnames into IP addresses. Under DNS, there is no central database with all of the Internet host information. The information is distributed among thousands of name servers organized into a hierarchy similar to the hierarchy of the Unix filesystem. DNS has a root domain at the top of the domain hierarchy that is served by a group of name servers called the root servers.

Just as directories in the Unix filesystem are found by following a path from the root directory through subordinate directories to the target directory, information about a domain is found by tracing pointers from the root domain through subordinate domains to the target domain.

Directly under the root domain are the top-level domains. There are two basic types of top-level domains—geographic and organizational. Geographic domains have been set aside for each country in the world and are identified by a two-letter country code. Thus, this type of domain is called a country code top-level domain (ccTLD). For example, the ccTLD for the United Kingdom is .uk, for Japan it is .jp, and for the United States it is .us. When .us is used as the top-level domain, the second-level domain is usually a state’s two-letter postal abbreviation (e.g., .wy.us for Wyoming). U.S. geographic domains are usually used by state governments and K-12 schools but are not widely used for other hosts.

Within the United States, the most popular top-level domains are organizational—that is, membership in a domain is based on the type of organization (commercial, military, etc.) to which the system belongs.[19] These domains are called generic top-level domains or general-purpose top-level domains (gTLDs).

The official generic top-level domains are:

These are the fourteen current gTLDs. The first seven domains in the list (com, edu, gov, mil, net, int, and org) have been part of the domain system since the beginning. The last seven domains in the list (aero, biz, coop, museum, pro, info, and name) were added in 2000 to increase the number of top-level domains. One motivation for creating the new gTLDs is the huge size of the .com domain. It is so large that it is difficult to maintain an efficient .com database. Whether or not these new gTLDs will be effective in drawing registrations away from the .com domain remains to be seen.

Figure 3-1 illustrates the domain hierarchy using six of the original organizational top-level domains. At the top is the root. Directly below the root domain are the top-level domains. The root servers have complete information only about the top-level domains. No servers, not even the root servers, have complete information about all domains, but the root servers have pointers to the servers for the second-level domains.[20] So while the root servers may not know the answer to a query, they know who to ask.

Several domain name registrars have been authorized by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a nonprofit organization that was formed to take over the responsibility for allocating domain names and IP addresses. (Previously, the U.S. government oversaw this process.) ICANN has authorized these registrars to allocate domains. To obtain a domain, you apply to a registrar for authority to create a domain under one of the top-level domains. (The details of applying for a domain name are covered in Chapter 4.) Once the authority to create a domain is granted, you can create additional domains, called subdomains, under your domain. Let’s look at how this works at our imaginary company.

Our company is a commercial, profit-making (we hope) enterprise. It clearly falls into the com domain. We apply for authority to create a domain named wrotethebook within the com domain. The request for the new domain contains the hostnames and addresses of the servers that will provide name service for the new domain. When the registrar approves the request, it adds pointers in the com domain to the new domain’s name servers. Now when queries are received by the root servers for the wrotethebook.com domain, the queries are referred to the new name servers.

The registrar’s approval grants us complete authority over our new domain. Any registered domain has authority to divide its domain into subdomains. Our imaginary company can create separate domains for the division that handles special events (events.wrotethebook.com) and for the division that coordinates the preparation of magazine articles (articles.wrotethebook.com) without consulting the registrar or any other “higher authority.” The decision to add subdomains is completely up to the local domain administrator. The registrars delegate authority and distribute control over names to individual organizations. Once that authority has been delegated, the individual organization is responsible for managing the names it has been assigned.

A new subdomain becomes accessible when pointers to the servers for the new domain are placed in the domain above it (see Figure 3-1). Remote servers cannot locate the wrotethebook.com domain until a pointer to its server is placed in the com domain. Likewise, the subdomains events and articles cannot be accessed until pointers to them are placed in wrotethebook.com. The DNS database record that points to the name servers for a domain is the NS (name server) record. This record contains the name of the domain and the name of the host that is a server for that domain. Chapter 8 discusses the actual DNS database. For now, let’s just think of these records as pointers.

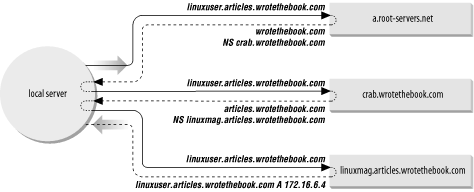

Figure 3-2 illustrates how the NS records are used as pointers. A local server has a request to resolve linuxuser.articles.wrotethebook.com into an IP address. The server has no information on wrotethebook.com in its cache, so it queries a root server (a.root-servers.net in our example) for the address. The root server replies with an NS record that points to crab.wrotethebook.com as the source of information on wrotethebook.com. The local server queries crab, which points it to linuxmag.articles.wrotethebook.com as the server for articles.wrotethebook.com. The local server then queries linuxmag.articles.wrotethebook.com and finally receives the desired IP address. The local server caches the A (address) record and each of the NS records. The next time it has a query for linuxuser.articles.wrotethebook.com, it will answer the query itself. And the next time the server has a query for other information in the wrotethebook.com domain, it will go directly to crab without involving a root server.

Figure 3-2 provides examples of both recursive and nonrecursive searches. The remote servers are examples of nonrecursive servers. The remote servers tell the local server who to ask next. The local server must follow the pointers itself. The local server is an example of a recursive server. In a recursive search, the server follows the pointers and returns the final answer for the query. The root servers generally perform only nonrecursive searches. Most other servers perform recursive searches.

Domain names reflect the domain hierarchy. They are written from most specific (a hostname) to least specific (a top-level domain), with each part of the domain name separated by a dot.[21] A fully qualified domain name (FQDN) starts with a specific host and ends with a top-level domain. rodent.wrotethebook.com is the FQDN of workstation rodent, in the wrotethebook domain, of the com domain.

Domain names are not always written as fully qualified domain names. They can be written relative to a default domain in the same way that Unix pathnames are written relative to the current (default) working directory. DNS adds the default domain to the user input when constructing the query for the name server. For example, if the default domain is wrotethebook.com, a user can omit the wrotethebook.com extension for any hostnames in that domain. crab.wrotethebook.com could be addressed simply as crab; DNS adds the default domain wrotethebook.com.

On most systems, the default domain name is added only if there is no dot in the requested hostname. For example, linuxuser.articles would not be extended and would therefore not be resolved by the name server because articles is not a valid top-level domain. But the hostname crab, which contains no dot, would be extended with wrotethebook.com, giving the valid domain name crab.wrotethebook.com. Like almost everything on a Unix system, this behavior is configurable, as you’ll see in Chapter 8.

How the default domain is used and how queries are constructed vary depending on the software configuration. For this reason, you should exercise caution when embedding a hostname in a program. Only a fully qualified domain name or an IP address is immune from changes in the name server software.

The implementation of DNS used on Unix systems is the Berkeley Internet Name Domain (BIND) software. Descriptions in this text are based on the BIND name server implementation.

DNS software is conceptually divided into two components—a resolver and a name server. The resolver is the software that forms the query; it asks the questions. The name server is the process that responds to the query; it answers the questions.

The resolver does not exist as a distinct process running on the computer. Rather, the resolver is a library of software routines (called the resolver code) that is linked into any program that needs to look up addresses. This library knows how to ask the name server for host information.

Under BIND, all computers use resolver code, but not all computers run the name server process. A computer that does not run a local name server process and relies on other systems for all name service answers is called a resolver-only system. Resolver-only configurations are common on single-user systems. Larger Unix systems usually run a local name server process.

The BIND name server runs as a distinct process called named (pronounced “name” “d”). Name servers are classified differently depending on how they are configured. The three main categories of name servers are:

- Master

The master server (also called the primary server) is the server from which all data about a domain is derived. The master server loads the domain’s information directly from a disk file created by the domain administrator. Master servers are authoritative, meaning they have complete information about their domain and their responses are always accurate. There should be only one master server for a domain.

- Slave

Slave servers (also known as secondary servers) transfer the entire domain database from the master server. A particular domain’s database file is called a zone file; copying this file to a slave server is called a zone file transfer. A slave server assures that it has current information about a domain by periodically transferring the domain’s zone file. Slave servers are also authoritative for their domain.

- Caching-only

Caching-only servers get the answers to all name service queries from other name servers. Once a caching server has received an answer to a query, it caches the information and will use it in the future to answer queries itself. Most name servers cache answers and use them in this way. What makes the caching-only server unique is that this is the only technique it uses to build its domain database. Caching servers are non-authoritative, meaning that their information is second-hand and incomplete, though usually accurate.

The relationship between the different types of servers is an advantage that DNS has over the host table for most networks, even very small networks. Under DNS, there should be only one primary name server for each domain. DNS data is entered into the primary server’s database by the domain administrator. Therefore, the administrator has central control of the hostname information. An automatically distributed, centrally controlled database is an advantage for a network of any size. When you add a new system to the network, you don’t need to modify the /etc/hosts files on every node in the network; you modify only the DNS database on the primary server. The information is automatically disseminated to the other servers by full zone transfers or by caching single answers.

The Network Information Service (NIS)[22] is an administrative database system developed by Sun Microsystems. It provides central control and automatic dissemination of important administrative files. NIS can be used in conjunction with DNS or as an alternative to it.

NIS and DNS have similarities and differences. Like DNS, the Network Information Service overcomes the problem of accurately distributing the host table, but unlike DNS, it provides service only for local area networks. NIS is not intended as a service for the Internet as a whole. Another difference is that NIS provides access to a wider range of information than DNS—much more than name-to-address conversions. It converts several standard Unix files into databases that can be queried over the network. These databases are called NIS maps.

NIS converts files such as /etc/hosts and /etc/networks into maps. The maps can be stored on a central server where they can be centrally maintained while still being fully accessible to the NIS clients. Because the maps can be both centrally maintained and automatically disseminated to users, NIS overcomes a major weakness of the host table. But NIS is not an alternative to DNS for Internet hosts because the host table, and therefore NIS, contains only a fraction of the information available to DNS. For this reason DNS and NIS are usually used together.

This chapter has introduced the concept of hostnames and provided an overview of the various techniques used to translate hostnames into IP addresses. This is by no means the complete story. Assigning hostnames and managing name service are important tasks for the network administrator. These topics are revisited several times in this book and discussed in extensive detail in Chapter 8.

Name service is not the only service that you will install on your network. Another service that you are sure to use is electronic mail.

Users consider electronic mail the most important network service because they use it for interpersonal communications. Some applications are newer and fancier; others consume more network bandwidth; and others are more important for the continued operation of the network. But email is the application people use to communicate with each other. It isn’t very fancy, but it is vital.

TCP/IP provides a reliable, flexible email system built on a few basic protocols. These protocols are Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), Post Office Protocol (POP), Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP), and Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME). There are other TCP/IP mail protocols that have some interesting features, but they are not yet widely implemented.

Our coverage concentrates on the four protocols you are most likely to use building your network: SMTP, POP, IMAP, and MIME. We start with SMTP, the foundation of all TCP/IP email systems.

SMTP is the TCP/IP mail delivery protocol. It moves mail across the Internet and across your local network. SMTP is defined in RFC 821, A Simple Mail Transfer Protocol. It runs over the reliable, connection-oriented service provided by Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), and it uses well-known port number 25.[23] Table 3-1 lists some of the simple, human-readable commands used by SMTP.

Table 3-1. SMTP commands

Command | Syntax | Function |

|---|---|---|

Hello | HELO

< EHLO < | Identify sending SMTP |

From | MAIL

FROM:< | Sender address |

Recipient | RCPT

TO:< | Recipient address |

Data | DATA | Begin a message |

Reset | RSET | Abort a message |

Verify | VRFY < | Verify a username |

Expand | EXPN < | Expand a mailing list |

Help | HELP

[ | Request online help |

Quit | QUIT | End the SMTP session |

SMTP is such a simple protocol you can literally do it yourself.

telnet to port 25 on a remote host

and type mail in from the command line using the SMTP commands. This

technique is sometimes used to test a remote system’s SMTP server, but

we use it here to illustrate how mail is delivered between systems.

The example below shows mail that Daniel on

rodent.wrotethebook.com manually input and sent

to Tyler on crab.wrotethebook.com.

$ telnet crab 25 Trying 172.16.12.1... Connected to crab.wrotethebook.com. Escape character is '^]'. 220 crab.wrotethebook.com ESMTP Sendmail 8.9.3+Sun/8.9.3; Thu, 19 Apr 2001 16:28:01-0400 (EDT) HELO rodent.wrotethebook.com 250 crab.wrotethebook.com Hello rodent [172.16.12.2], pleased to meet you MAIL FROM:<daniel@rodent.wrotethebook.com> 250 <daniel@rodent.wrotethebook.com>... Sender ok RCPT TO:<tyler@crab.wrotethebook.com> 250 <tyler@crab.wrotethebook.com>... Recipient ok DATA 354 Enter mail, end with "." on a line by itself Hi Tyler! . 250 QAA00316 Message accepted for delivery QUIT 221 crab.wrotethebook.com closing connection Connection closed by foreign host.

The user input is shown in bold type. All of the other lines are output from the system. This example shows how simple it is. A TCP connection is opened. The sending system identifies itself. The From address and the To address are provided. The message transmission begins with the DATA command and ends with a line that contains only a period (.). The session terminates with a QUIT command. Very simple, and very few commands are used.

There are other commands (SEND, SOML, SAML, and TURN) defined in RFC 821 that are optional and not widely implemented. Even some of the commands that are implemented are not commonly used. The commands HELP, VRFY, and EXPN are designed more for interactive use than for the normal machine-to-machine interaction used by SMTP. The following excerpt from a SMTP session shows how these odd commands work.

HELP 214-This is Sendmail version 8.9.3+Sun 214-Topics: 214- HELO EHLO MAIL RCPT DATA 214- RSET NOOP QUIT HELP VRFY 214- EXPN VERB ETRN DSN 214-For more info use "HELP <topic>". 214-For local information contact postmaster at this site. 214 End of HELP info HELP RSET 214-RSET 214- Resets the system. 214 End of HELP info VRFY <jane> 250 <jane@brazil.wrotethebook.com> VRFY <mac> 250 Kathy McCafferty <<mac>> EXPN <admin> 250-<sara@horseshoe.wrotethebook.com> 250 David Craig <<david>> 250-<tyler@wrotethebook.com>

The HELP command prints out a summary of the commands implemented on the system. The HELP RSET command specifically requests information about the RSET command. Frankly, this help system isn’t very helpful!

The VRFY and EXPN commands are more useful but are often disabled for

security reasons because they provide user account information that

might be exploited by network intruders. The EXPN <admin> command asks for a listing of

the email addresses in the mailing list admin,

and that is what the system provides. The VRFY command asks for information about an individual instead of a

mailing list. In the case of the VRFY <mac> command,

mac is a local user account, and the user’s

account information is returned. In the case of VRFY <jane>, jane is

an alias in the /etc/aliases file. The value

returned is the email address for jane found in

that file. The three commands in this example are interesting but

rarely used. SMTP depends on the other commands to get the real work

done.

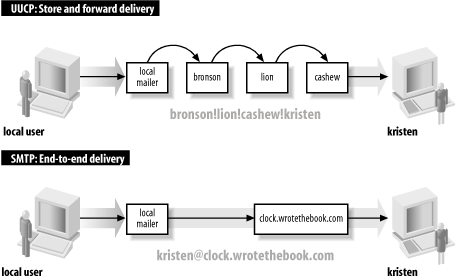

SMTP provides direct end-to-end mail delivery. Other mail systems, like UUCP and X.400, use store and forward protocols that move mail toward its destination one hop at a time, storing the complete message at each hop and then forwarding it on to the next system. The message proceeds in this manner until final delivery is made. Figure 3-3 illustrates both store-and-forward and direct-delivery mail systems. The UUCP address clearly shows the path that the mail takes to its destination, while the SMTP mail address implies direct delivery.[24]

Direct delivery allows SMTP to deliver mail without relying on intermediate hosts. If the delivery fails, the local system knows it right away. It can inform the user that sent the mail or queue the mail for later delivery without reliance on remote systems. The disadvantage of direct delivery is that it requires both systems to be fully capable of handling mail. Some systems cannot handle mail, particularly small systems such as PCs or mobile systems such as laptops. These systems are usually shut down at the end of the day and are frequently offline. Mail directed from a remote host fails with a “cannot connect” error when the local system is turned off or is offline. To handle these cases, features in the DNS system are used to route the message to a mail server in lieu of direct delivery. The mail is then moved from the server to the client system when the client is back online. One of the protocols TCP/IP networks use for this task is POP.

There are two versions of Post Office Protocol: POP2 and POP3. POP2, defined in RFC 937, uses port 109, and POP3, defined in RFC 1725, uses port 110. These are incompatible protocols that use different commands, although they perform the same basic functions. The POP protocols verify the user’s login name and password and move the user’s mail from the server to the user’s local mail reader. POP2 is rarely used anymore, so this section focuses on POP3.

A sample POP3 session clearly illustrates how a POP protocol works. POP3 is a simple request/response protocol, and just as with SMTP, you can type POP3 commands directly into its well-known port (110) and observe their effect. Here’s an example with the user input shown in bold type:

% telnet crab 110 Trying 172.16.12.1 ... Connected to crab.wrotethebook.com. Escape character is '^]'. +OK crab POP3 Server Process 3.3(1) at Mon 16-Apr-2001 4:48PM-EDT USER hunt +OK User name (hunt) ok. Password, please. PASS Watts?Watt? +OK 3 messages in folder NEWMAIL (V3.3 Rev B04) STAT +OK 3 459 RETR 1 +OK 146 octets ...The full text of message 1... DELE 1 +OK message # 1 deleted RETR 2 +OK 155 octets ...The full text of message 2... DELE 2 +OK message # 2 deleted RETR 3 +OK 158 octets ...The full text of message 3... DELE 3 +OK message # 3 deleted QUIT +OK POP3 crab Server exiting (0 NEWMAIL messages left) Connection closed by foreign host.

The USER command provides the username, and the PASS command provides the password for the account of

the mailbox that is being retrieved. (This is the same username and

password the user would use to log into the mail server.) In response

to the STAT command, the server sends a count of the number of

messages in the mailbox and the total number of bytes contained in

those messages. In the example, there are three messages that contain

a total of 459 bytes. RETR 1 retrieves the full text of the first message. DELE 1

deletes that message from the server. Each message is

retrieved and deleted in turn. The client ends the session with the

QUIT command. Simple! Table 3-2 lists the full set of

POP3 commands.

Table 3-2. POP3 commands

Command | Function |

|---|---|

USER username | The user’s account name |

PASS password | The user’s password |

STAT | Display the number of unread messages/bytes |

RETR n | Retrieve message number

|

DELE n | Delete message number n |

LAST | Display the number of the last message accessed |

LIST [n] | Display the size of message n or of all messages |

RSET | Undelete all messages; reset message number to 1 |

TOP n l | Print the headers and l lines of message n |

NOOP | Do nothing |

QUIT | End the POP3 session |

The retrieve (RETR) and delete (DELE) commands use message numbers that allow messages to be processed in any order. Additionally, there is no direct link between retrieving a message and deleting it. It is possible to delete a message that has never been read or to retain a message even after it has been read. However, POP clients do not normally take advantage of these possibilities. On an average POP server, the entire contents of the mailbox are moved to the client and either deleted from the server or retained as if never read. Deletion of individual messages on the client is not reflected on the server because all of the messages are treated as a single unit that is either deleted or retained after the initial transfer of data to the client. Email clients that want to remotely maintain a mailbox on the server are more likely to use IMAP.

Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) is an alternative to POP. It provides the same basic service as POP and adds features to support mailbox synchronization, which is the ability to read individual mail messages on a client or directly on the server while keeping the mailboxes on both systems completely up to date. IMAP provides the ability to manipulate individual messages on the client or the server and to have those changes reflected in the mailboxes of both systems.

IMAP uses TCP for reliable, sequenced data delivery. The IMAP port is TCP port 143.[25] Like the POP protocol, IMAP is also a request/response protocol with a small set of commands. The IMAP command set is somewhat more complex than the one used by POP because IMAP does more, yet there are still fewer than 25 IMAP commands. Table 3-3 lists the basic set of IMAP commands as defined in RFC 2060, Internet Message Access Protocol - Version 4rev1.

Table 3-3. IMAP4 commands

Command | Function |

|---|---|

CAPABILITY | List the features supported by the server |

NOOP | Literally “No Operation” |

LOGOUT | Close the connection |

AUTHENTICATE | Request an alternate authentication method |

LOGIN | Provide the username and password for plain-text authentication |

SELECT | Open a mailbox |

EXAMINE | Open a mailbox as read-only |

CREATE | Create a new mailbox |

DELETE | Remove a mailbox |

RENAME | Change the name of a mailbox |

SUBSCRIBE | Add a mailbox to the list of active mailboxes |

UNSUBSCRIBE | Delete a mailbox name from the list of active mailboxes |

LIST | Display the requested mailbox names from the set of all mailbox names |

LSUB | Display the requested mailbox names from the set of active mailboxes |

STATUS | Request the status of a mailbox |

APPEND | Add a message to the end of the specified mailbox |

CHECK | Force a checkpoint of the current mailbox |

CLOSE | Close the mailbox and remove all messages marked for deletion |

EXPUNGE | Remove from the current mailbox all messages marked for deletion |

SEARCH | Display all messages in the mailbox that match the specified search criterion |

FETCH | Retrieve a message from the mailbox |

STORE | Modify a message in the mailbox |

COPY | Copy the specified messages to the end of the specified mailbox |

UID | Locate a message based on the message’s unique identifier |

This command set clearly illustrates the “mailbox” orientation

of IMAP. The protocol is designed to remotely maintain mailboxes that

are stored on the server. The protocol commands show that. Despite the

increased complexity of the protocol, it is still possible to run a

simple test of your IMAP server using telnet and a small number of the IMAP

commands.

$ telnet localhost 143 Trying 127.0.0.1... Connected to rodent.wrotethebook.com. Escape character is '^]'. * OK rodent.wrotethebook.com IMAP4rev1 v12.252 server ready a0001 LOGIN craig Wats?Watt? a0001 OK LOGIN completed a0002 SELECT inbox * 3 EXISTS * 0 RECENT * OK [UIDVALIDITY 965125671] UID validity status * OK [UIDNEXT 5] Predicted next UID * FLAGS (\Answered \Flagged \Deleted \Draft \Seen) * OK [PERMANENTFLAGS (\* \Answered \Flagged \Deleted \Draft \Seen)] Permanent flags * OK [UNSEEN 1] first unseen message in /var/spool/mail/craig a0002 OK [READ-WRITE] SELECT completed a0003 FETCH 1 BODY[TEXT] * 1 FETCH (BODY[TEXT] {1440} ... an e-mail message that is 1440 bytes long ... * 1 FETCH (FLAGS (\Seen)) a0003 OK FETCH completed a0004 STORE 1 +FLAGS \DELETED * 1 FETCH (FLAGS (\Seen \Deleted)) a0004 OK STORE completed a0005 CLOSE a0005 OK CLOSE completed a0006 LOGOUT * BYE rodent.wrotethebook.com IMAP4rev1 server terminating connection a0006 OK LOGOUT completed Connection closed by foreign host.

The first three lines and the last line come from telnet; all other messages come from IMAP.

The first IMAP command entered by the user is LOGIN, which provides

the username and password from /etc/passwd used to authenticate this user.

Notice that the command is preceded by the string A0001. This is a tag,

which is a unique identifier generated by the client for each command.

Every command must start with a tag. When you manually type in

commands for a test, you are the source of the tags.

IMAP is a mailbox-oriented protocol. The SELECT command selects the mailbox that will be used. In the example, the user selects a mailbox named “inbox”. The IMAP server displays the status of the mailbox, which contains three messages. Associated with each message are a number of flags. The flags are used to manage the messages in the mailbox by marking them as Seen, Unseen, Deleted, and so on.

The FETCH command downloads a message from the mailbox. In the example, the user downloads the text of the message, which is what you normally see when reading a message. It is possible, however, to download only the headers or flags.

After the message is downloaded, the user deletes it. This is done by writing the Deleted flag with the STORE command. The DELETE command is not used to delete messages; it deletes entire mailboxes. Individual messages are marked for deletion by setting the Delete flag. Messages with the Delete flag set are not deleted until either the EXPUNGE command is issued or the mailbox is explicitly closed with the CLOSE command, as is done in the example. The session is then terminated with the LOGOUT command.

Clearly, the IMAP protocol is more complex than POP; it is just

about at the limits of what can reasonably be typed in manually. Of

course, you don’t really enter these commands manually. The desktop

system and the server exchange them automatically. They are shown here

only to give you a sense of the IMAP protocol. About the only IMAP

test you would ever do manually is to test if imapd is up and running. To do that, you

don’t even need to log in; if the server answers the telnet, you know it is up and running. All

you then need to do is send the LOGOUT command to gracefully

close the connection.

The last email protocol on our quick tour is Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME).[26] As its name implies, MIME is an extension of the existing TCP/IP mail system, not a replacement for it. MIME is more concerned with what the mail system delivers than with the mechanics of delivery. It doesn’t attempt to replace SMTP or TCP; it extends the definition of what constitutes “mail.”

The structure of the mail message carried by SMTP is defined in RFC 822, Standard for the Format of ARPA Internet Text Messages. RFC 822 defines a set of mail headers that are so widely accepted they are used by many mail systems that do not use SMTP. This is a great benefit to email because it provides a common ground for mail translation and delivery through gateways to different mail networks. MIME extends RFC 822 into two areas not covered by the original RFC:

Support for various data types. The mail system defined by RFC 821 and RFC 822 transfers only 7-bit ASCII data. This is suitable for carrying text data composed of U.S. ASCII characters, but it does not support several languages that have richer character sets, nor does it support binary data transfer.

Support for complex message bodies. RFC 822 doesn’t provide a detailed description of the body of an electronic message. It concentrates on the mail headers.

MIME addresses these two weaknesses by defining encoding techniques for carrying various forms of data and by defining a structure for the message body that allows multiple objects to be carried in a single message. RFC 1521, Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions Part One: Format of Internet Message Bodies, defines two headers that give structure to the mail message body and allow it to carry various forms of data. These are the Content-Type header and the Content-Transfer-Encoding header.

As the name implies, the Content-Type header defines the type of data being carried in the message. The header has a Subtype field that refines the definition. Many subtypes have been defined since the original RFC was released. A current list of MIME types can be obtained from the Internet.[27] The original RFC defines seven initial content types and a few subtypes:

- text

Text data. RFC 1521 defines text subtypes plain and richtext. More than 30 subtypes have since been added, including enriched, xml and html.

- application

Binary data. The primary subtype defined in RFC 1521 is octet-stream, which indicates the data is a stream of 8-bit binary bytes. One other subtype, PostScript, is defined in the standard. Since then more than 200 subtypes have been defined. They specify binary data formatted for a particular application. For example, msword is an application subtype.

- image

Still graphic images. Two subtypes are defined in RFC 1521: jpeg and gif. More than 20 additional subtypes have since been added, including widely used image data standards such as tiff, cgm, and g3fax.

- video

Moving graphic images. The initially defined subtype was mpeg, which is a widely used standard for computer video data. A few others have since been added, including quicktime.

- audio

Audio data. The only subtype initially defined for audio was basic, which means the sounds are encoded using pulse code modulation (PCM). About 20 additional audio types, such as MP4A-LATM, have since been added.

- multipart

Data composed of multiple independent sections. A multipart message body is made up of several independent parts. RFC 1521 defines four subtypes. The primary subtype is mixed, which means that each part of the message can be data of any content type. Other subtypes are alternative, meaning that the same data is repeated in each section in different formats; parallel, meaning that the data in the various parts is to be viewed simultaneously; and digest, meaning that each section is data of the type message. Several subtypes have since been added, including support for voice messages (voice-message) and encrypted messages.

- message

Data that is an encapsulated mail message. RFC 1521 defines three subtypes. The primary subtype, rfc822, indicates that the data is a complete RFC 822 mail message. The other subtypes, partial and External-body, are both designed to handle large messages. partial allows large encapsulated messages to be split among multiple MIME messages. External-body points to an external source for the contents of a large message body so that only the pointer, not the message itself, is contained in the MIME message. Two additional subtypes that have been defined are news for carrying network news and http for HTTP traffic formatted to comply with MIME content typing.

The Content-Transfer-Encoding header identifies the type of encoding used on the data. Traditional SMTP systems forward only 7-bit ASCII data with a line length of less than 1000 bytes. Since the data from a MIME system may be forwarded through gateways that support only 7-bit ASCII, the data can be encoded. RFC 1521 defines six types of encoding. Some types are used to identify the encoding inherent in the data. Only two types are actual encoding techniques defined in the RFC. The six encoding types are:

- 7bit

U.S. ASCII data. No encoding is performed on 7-bit ASCII data.

- 8bit

Octet data. No encoding is performed. The data is binary, but the lines of data are short enough for SMTP transport; i.e., the lines are less than 1000 bytes long.

- binary

Binary data. No encoding is performed. The data is binary and the lines may be longer than 1000 bytes. There is no difference between binary and 8bit data except the line length restriction; both types of data are unencoded byte (octet) streams. MIME does not modify unencoded bitstream data.

- quoted-printable

Encoded text data. This encoding technique handles data that is largely composed of printable ASCII text. The ASCII text is sent unencoded, while bytes with a value greater than 127 or less than 33 are sent encoded as strings made up of the equals sign followed by the hexadecimal value of the byte. For example, the ASCII form feed character, which has the hexadecimal value of 0C, is sent as =0C. Naturally, there’s more to it than this—for example, the literal equals sign has to be sent as =3D, and the newline at the end of each line is not encoded. But this is the general idea of how quoted-printable data is sent.

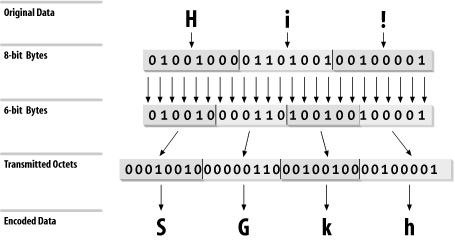

- base64

Encoded binary data. This encoding technique can be used on any byte-stream data. Three octets of data are encoded as four 6-bit characters, which increases the size of the file by one-third. The 6-bit characters are a subset of U.S. ASCII, chosen because they can be handled by any type of mail system. The maximum line length for base64 data is 76 characters. Figure 3-4 illustrates this 3-to-4 encoding technique.

- x-token

Specially encoded data. It is possible for software developers to define their own private encoding techniques. If they do so, the name of the encoding technique must begin with X-. Doing this is strongly discouraged because it limits interoperability between mail systems.

The number of supported data types and encoding techniques grows as new data formats appear and are used in message transmissions. New RFCs constantly define new data types and encoding. Read the latest RFCs to keep up with MIME developments.

MIME defines data types that SMTP was not designed to carry. To handle these and other future requirements, RFC 1869, SMTP Service Extensions, defines a technique for making SMTP extensible. The RFC does not define new services for SMTP; in fact, the only service extensions mentioned in the RFC are defined in other RFCs. What this RFC does define is a simple mechanism for systems to negotiate which SMTP extensions are supported. The RFC defines a new hello command (EHLO) and the legal responses to that command. One response is for the receiving system to return a list of the SMTP extensions it supports. This response allows the sending system to know what extended services can be used, and to avoid those that are not implemented on the remote system. SMTP implementations that support the EHLO command are called Extended SMTP (ESMTP).

Several ESMTP service extensions have been defined for MIME mailers. Table 3-4 lists some of these. The table lists the EHLO keyword associated with each extension, the number of the RFC that defines it, and its purpose. These service extensions are just an example. Other have been defined to support SMTP enhancements.

Table 3-4. SMTP service extensions

Keyword | RFC | Function |

|---|---|---|

8BITMIME | 1652 | Accept 8bit binary data |

CHUNKING | 1830 | Accept messages cut into chunks |

CHECKPOINT | 1845 | Checkpoint/restart mail transactions |

PIPELINING | 1854 | Accept multiple commands in a single send |

SIZE | 1870 | Display maximum acceptable message size |

DSN | 1891 | Provide delivery status notifications |

ETRN | 1985 | Accept remote queue processing requests |

ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES | 2034 | Provide enhanced error codes |

STARTTLS | 2487 | Use Transport Layer Security to encrypt the email exchange |

AUTH | 2554 | Use strong authentication to identify the email source |

It is easy to check which extensions are supported by your

server by using the EHLO command.

The following example is from a generic Solaris 8 system, which comes

with sendmail 8.9.3:

> telnet localhost 25 Trying 127.0.0.1... Connected to localhost. Escape character is '^]'. 220 crab.wrotethebook.com ESMTP Sendmail 8.9.3+Sun/8.9.3; Mon, 23 Apr 2001 11:00:35-0400 (EDT) EHLO crab 250-crab.wrotethebook.com Hello localhost [127.0.0.1], pleased to meet you 250-EXPN 250 HELP 250-8BITMIME 250-SIZE 250-DSN 250-ETRN 250-VERB 250-ONEX 250-XUSR QUIT 221 crab.foobirds.org closing connection Connection closed by foreign host.

The sample system lists nine commands in response to the EHLO

greeting. Two of these, EXPN and HELP, are standard SMTP commands that aren’t

implemented on all systems (the standard commands are listed in Table 3-1). 8BITMIME, SIZE, DSN,

and ETRN are ESMTP extensions, all of which are described in Table 3-4. The last three keywords

in the response are VERB, ONEX, and XUSR. All of these are specific to

sendmail version 8. None is defined in an RFC. VERB simply places the sendmail server in verbose mode. ONEX

limits the session to a single message transaction. XUSR

is equivalent to the -U sendmail

command-line argument.[28] As the last three keywords indicate, the RFCs allow for

private ESMTP extensions.

The specific extensions implemented on each system are different. For example, on a generic Solaris 2.5.1 system, only three keywords (EXPN, SIZE, and HELP) are displayed in response to EHLO. The extensions available depend on the version of sendmail that is running and on how sendmail is configured.[29] The purpose of EHLO is to identify these differences at the beginning of the SMTP mail exchange.

ESMTP and MIME are important because they provide a standard way to transfer non-ASCII data through email. Users share lots of application-specific data that is not 7-bit ASCII. Many users depend on email as a file transfer mechanism.

SMTP, POP, IMAP, and MIME are essential parts of the mail system, but other email protocols may also be essential in the future. The one certainty is that the network will continue to change. You need to track current developments and include helpful technologies in your planning. Two technologies that users find helpful are file sharing and printer sharing. In the next section we look at file and print servers.

File and print services make the network more convenient for users. Not long ago, disk drives and high-quality printers were relatively expensive, and diskless workstations were common. Today, every system has a large hard drive and many have their own high-quality laser printers, but the demand for resource-sharing services is higher than ever.

File sharing is not the same as file transfer; it is not simply the ability to move a file from one system to another. A true file-sharing system does not require you to move files across the network. It allows files to be accessed at the record level so that it is possible for a client to read a record from a file located on a remote server, update that record, and write it back to the server—without moving the entire file from the server to the client.

File sharing is transparent to the user and to the application software running on the user’s system. Through file sharing, users and programs access files located on remote systems as if they were local files. In a perfect file-sharing environment, the user neither knows nor cares where files are actually stored.

File sharing didn’t exist in the original TCP/IP protocol suite. It was added to support diskless workstations. Several TCP/IP protocols for file sharing have been defined, but two hold the lion’s share of the file sharing market:

- NetBIOS/Server Message Block

NetBIOS was originally defined by IBM. It is the basic networking used on Microsoft Windows systems. Unix systems can act as file and print servers for Windows clients by running the Samba software package that implements NetBIOS and Server Message Block (SMB) protocols.

- Network File System

NFS was defined by Sun Microsystems to support their diskless workstations. NFS is designed primarily for LAN applications and is implemented for all Unix systems and many other operating systems.

For file sharing between Unix systems, you will probably use NFS, as it is the most widely used Unix file-sharing protocol. If you need to support Windows clients using Unix servers, you will probably use Samba. For a detailed discussion of both of these tools, see Chapter 9.

A print server allows printers to be shared by everyone on the network. Printer sharing is not as important as file sharing, but it is a useful network service. The advantages of printer sharing are:

Fewer printers are needed, and less money is spent on printers and supplies.

Reduced maintenance. There are fewer machines to maintain, and fewer people spending time fiddling with printers.

Access to special printers. Very high-quality color printers and very high-speed printers are expensive and needed only occasionally. Sharing these printers makes the best use of expensive resources.

There are two techniques commonly used for sharing printers on a

corporate network. One technique is to use the sharing services

provided by Samba. This is the technique preferred by Windows

clients. The other approach is to use the traditional Unix lpr command and an lpd

server. Print server configuration is also covered in Chapter 9.

This chapter concludes with a discussion of the various types of TCP/IP configuration servers. Unlike email, file sharing, and print servers, configuration servers are not used on every network. However, the demand for easier installation and improved mobility makes configuration servers an important part of many networks.

The powerful features that add to the utility and flexibility of TCP/IP also add to its complexity. TCP/IP is not as easy to configure as some other networking systems. TCP/IP requires that the configuration provide hardware, addressing, and routing information. It is designed to be independent of any specific underlying network hardware, so configuration information that can be built into the hardware in some network systems cannot be built in for TCP/IP. The information must be provided by the person responsible for the configuration. This assumes that every system is run by people who are knowledgeable enough to provide the proper information to configure the system. Unfortunately, this assumption does not always prove correct.

Configuration servers make it possible for the network administrator to control TCP/IP configuration from a central point. This relieves the end user of some of the burden of configuration and improves the quality of the information used to configure systems.

TCP/IP has used three protocols to simplify the task of configuration: RARP, BOOTP, and DHCP. We begin with RARP, the oldest and most basic of these configuration tools.

RARP, defined in RFC 903, is a protocol that converts a physical network address into an IP address, which is the reverse of what Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) does. A Reverse Address Resolution Protocol server maps a physical address to an IP address for a client that doesn’t know its own IP address. The client sends out a broadcast using the broadcast services of the physical network.[30] The broadcast packet contains the client’s physical network address and asks if any system on the network knows what IP address is associated with the address. The RARP server responds with a packet that contains the client’s IP address.

The client knows its physical network address because it is encoded in the Ethernet interface hardware. On most systems, you can easily check the value with a command. For example, on a Solaris 8 system, the superuser can type:

# ifconfig dnet0

dnet0: flags=1000843<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,MULTICAST,IPv4> mtu 1500 index 2

inet 172.16.12.1 netmask ffffff00 broadcast 172.16.12.255

ether 0:0:c0:dd:d4:daThe ifconfig command

can set or display the configuration values for a

network interface.[31] dnet0 is the device name of the

Ethernet interface. The Ethernet address is displayed after the

ether label. In the example, the address is

0:0:c0:dd:d4:da.

The RARP server looks up the IP address that it uses in its response to the client in the /etc/ethers file. The /etc/ethers file contains the client’s Ethernet address followed by the client’s hostname. For example:

2:60:8c:48:84:49 clock 0:0:c0:a1:5e:10 ring 0:80:c7:aa:a8:04 24seven 8:0:5a:1d:c0:7e limulus 8:0:69:4:6:31 arthropod

To respond to a RARP request, the server must also resolve the hostname found in the /etc/ethers file into an IP address. DNS or the hosts file is used for this task. The following hosts file entries could be used with the ethers file shown above:

clock 172.16.3.10 ring 172.16.3.16 24seven 172.16.3.4 limulus 172.16.3.7 arthropod 172.16.3.21

Given these sample files, if the server receives a RARP request that contains the Ethernet address 0:80:c7:aa:a8:04, it matches it to 24seven in the /etc/ethers file. The server uses the name 24seven to look up the IP address. It then sends the IP address 172.16.3.4 out as its ARP response.

RARP is a useful tool, but it provides only the IP address. There are still several other values that need to be manually configured. Bootstrap Protocol (BOOTP) is a more flexible configuration tool that provides more values than just the IP address and can deliver those values via the network.

BOOTP is defined in RFCs 951 and 1532. The RFCs describe BOOTP as an alternative to RARP; when BOOTP is used, RARP is not needed. BOOTP, however, is a more comprehensive configuration protocol than RARP. It provides much more configuration information and has the potential to offer still more. The original specification allowed vendor extensions as a vehicle for the protocol’s evolution. RFC 1048 first formalized the definition of these extensions, which have been updated over time and are currently defined in RFC 2132. BOOTP and its extensions became the basis for the Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). DHCP has superseded BOOTP, so DHCP is the configuration protocol that you will use on your network.

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) is defined in RFCs 2131 and 2132. It’s designed to be compatible with BOOTP. RFC 1534 outlines interactions between BOOTP clients and DHCP servers and between DHCP clients and BOOTP servers. DHCP is the correct configuration protocol for your network because DHCP exceeds the capabilities of BOOTP while maintaining support for existing BOOTP clients.

DHCP uses the same UDP ports as BOOTP (67 and 68) and the same basic packet format. But DHCP is more than just an update of BOOTP. The new protocol expands the function of BOOTP in two areas:

The configuration parameters provided by a DHCP server include everything defined in the Requirements for Internet Hosts RFC. DHCP provides a client with a complete set of TCP/IP configuration values.

DHCP permits automated allocation of IP addresses.

DHCP expands the original BOOTP packet in order to indicate the DHCP packet type and to carry a complete set of configuration information. DHCP calls the values in this part of the packet options. To handle the full set of configuration values from the Requirements for Internet Hosts RFC, the Options field is large and has a variable format.

You don’t usually need to use the full set of configuration values. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not that the values are unnecessary—all the parameters are needed for a complete TCP/IP configuration. It’s just that you don’t need to define values for them. Default values are provided in most TCP/IP implementations, and the defaults need to be changed only in special circumstances. The expanded configuration parameters of DHCP make it a more complete protocol than BOOTP, but they are not the most useful features of DHCP.

For most network administrators, automatic allocation of IP addresses is a more interesting feature. DHCP allows addresses to be assigned in four ways:

- Permanent fixed addresses

As always, the administrator can continue to assign addresses without using the DHCP system. While this happens completely outside of DHCP, DHCP makes allowances for it by permitting addresses to be excluded from the range of addresses under the control of the DHCP server. Most networks have some permanently assigned addresses.

- Manual allocation

The network administrator keeps complete control over addresses by specifically assigning them to clients in the DHCP configuration. This is exactly the same way that addresses are handled under BOOTP. Manual allocation fails to take full advantage of the power of DHCP but might be needed if you have BOOTP clients.

- Automatic allocation

The DHCP server permanently assigns an address from a pool of addresses. The administrator is not involved in the details of assigning a client an address. This technique fails to take advantage of the DHCP server’s ability to collect and reuse addresses.

- Dynamic allocation

The server assigns an address to a DHCP client for a limited period of time. The limited life of the address is called a lease. The client can return the address to the server at any time but must request an extension from the server to retain the address longer than the time permitted. The server automatically reclaims the address after the lease expires if the client has not requested an extension. Dynamic allocation uses the full power of DHCP.

Dynamic allocation is useful in any network, particularly a large distributed network where many systems are being added and deleted. Unused addresses are returned to the pool of addresses without relying on users or system administrators to deliberately return them. Addresses are used only when and where they’re needed. Dynamic allocation allows a network to make the maximum use of a limited set of addresses. It is particularly well suited to mobile systems that move from subnet to subnet and therefore must be constantly reassigned addresses appropriate for their current network location. Even in the smallest network, dynamic allocation simplifies the network administrator’s job.

Dynamic address allocation does not work for every system. Name servers, email servers, login hosts, and other shared systems are always online, and they are not mobile. These systems are accessed by name, so a shared system’s domain name must resolve to the correct address. Shared systems are manually allocated permanent, fixed addresses.

Dynamic address assignment has major repercussions for DNS. DNS is required to map hostnames to IP addresses. It cannot perform this job if IP addresses are constantly changing and DNS is not informed of the changes. To make dynamic address assignment work for all types of systems, we need a DNS that can be dynamically updated by the DHCP server. Dynamic DNS (DDNS) is available, but it is not yet widely used.[32] When fully deployed, it will help make dynamic addresses available to systems that provide services and to those that use them.

Given the nature of dynamic addressing, most sites assign permanent fixed addresses to shared servers. This happens through traditional system administration and is not handled by DHCP. In effect, the administrator of the shared server is given an address and puts that address in the shared server’s configuration. Using DHCP for some systems doesn’t mean it must be used for all systems.

DHCP servers can support BOOTP clients. However, a DHCP client is needed to take full advantage of the services offered by DHCP. BOOTP clients do not understand dynamic address leases. They do not know that an address can time out and that it must be renewed. BOOTP clients must be manually or automatically assigned permanent addresses. True dynamic address assignment is limited to DHCP clients.

Therefore, most sites that use DHCP have a mixture of:

Permanent addresses assigned to systems that can’t use DHCP

Manual addresses assigned to BOOTP clients

Dynamic addresses assigned to all DHCP clients

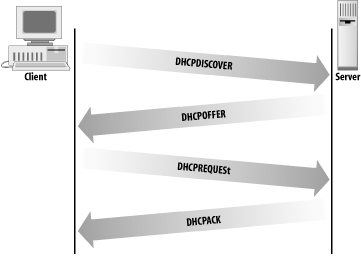

All of this begs the question of how a client that doesn’t know its own address can communicate with a server. DHCP defines a simple packet exchange that allows the client to find a server and obtain a configuration.

The DHCP client broadcasts a packet called a DHCPDISCOVER message that contains, at a minimum, a transaction identifier and the client’s DHCP identifier, which is normally the client’s physical network address. The client sends the broadcast using the address 255.255.255.255, which is a special address called the limited broadcast address.[33] The client waits for a response from the server. If a response is not received within a specified time interval, the client retransmits the request. DHCP uses UDP as a transport protocol and, unlike RARP, does not require any special Network Access Layer protocols.

The server responds to the client’s message with a DHCPOFFER packet. DHCP uses two different well-known port numbers. UDP port number 67 is used for the server, and UDP port number 68 is used for the client. This is very unusual. Most software uses a well-known port on the server side and a randomly generated port on the client side. (How and why random source port numbers are used is described in Chapter 1.) The random port number ensures that each pair of source/destination ports identifies a unique path for exchanging information. A DHCP client, however, is still in the process of booting. It probably does not know its IP address. Even if the client generates a source port for the DHCPDISCOVER packet, a server response that is addressed to that port and the client’s IP address won’t be read by a client that doesn’t recognize the address. Therefore, DHCP sends the response to a specific port on all hosts. A broadcast sent to UDP port 68 is read by all hosts, even by a system that doesn’t know its specific address. The system then determines if it is the intended recipient by checking the transaction identifier and the physical network address embedded in the response.

The server fills in the DHCPOFFER packet with the configuration data it has for the client. A DHCP server can provide every TCP/IP configuration value a client needs, provided the server is properly configured. Chapter 9 is a tutorial on setting up a DHCP server, and Appendix D is a complete list of all of the DHCP configuration parameters.

As the name implies, the DHCPOFFER packet is an offer of configuration data. That offer has a limited lifetime—typically 120 seconds. The client must respond to the offer before the lifetime expires. This is done because more than one server may hear the DHCPDISCOVER packet from the client and respond with a DHCPOFFER. If the servers did not require a response from the client, multiple servers might commit resources to a single client, thus wasting resources that could be used by other clients. If a client receives multiple DHCPOFFER packets, it responds to only one and ignores the others.

The client responds to the DHCPOFFER with a DHCPREQUEST message. The DHCPREQUEST message asks the server to assign the client the configuration information that was offered. The server checks the information in the DHCPREQUEST to make sure that the client got everything right and that all of the offered data is still available. If everything is correct, the server sends the client a DHCPACK message letting the client know that it is now configured to use all of the information from the original DHCPOFFER packet. Figure 3-5 shows the normal packet flow when DHCP is used to configure a client.

TCP/IP provides some network services that simplify network installation, configuration, and use. Name service is one such service and it is used on every TCP/IP network.

Name service can be provided by the host table, Domain Name System (DNS), and Network Information Service (NIS). The host table is a simple text file stored in /etc/hosts. Most systems have a small host table, but it cannot be used for all applications because it is not scalable and does not have a standard method for automatic distribution. NIS, the Sun “yellow pages” server, solves the problem of automatic distribution for the host table but does not solve the problem of scaling. DNS, which superseded the host table as a TCP/IP standard, does scale. DNS is a hierarchical, distributed database system that provides hostname and address information for all of the systems in the Internet.

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), Post Office Protocol (POP), Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP), and Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) are the building blocks of a TCP/IP email network. SMTP is a simple request/response protocol that provides end-to-end mail delivery. Sometimes end-to-end mail delivery is not suitable, and the mail must be routed to a mail server. TCP/IP mail servers can use POP or IMAP to move the mail from the server to the end system, where it is read by the user. SMTP can deliver only 7-bit ASCII data. MIME extends the TCP/IP mail system so that it can carry a wide variety of data.

Network File System (NFS) is the leading Unix file-sharing protocol. It allows server systems to export directories that are then mounted by clients and used as if they were local disk drives. The Unix LPD/LPR protocol can be used for printer sharing on a TCP/IP network. Samba provides similar file and print sharing services for Windows clients.

Many configuration values are needed to install TCP/IP. These values can be provided by a configuration server. Three protocols have been used by TCP/IP for distributing configuration information:

- RARP

Reverse Address Resolution Protocol tells a client its IP address. The RARP server does this by mapping the client’s Ethernet address to its IP address. The Ethernet to IP address mappings are stored on the server in the /etc/ethers file.

- BOOTP

Bootstrap Protocol provides a wide range of configuration values.

- DHCP

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol replaced BOOTP with a service that provides the full set of configuration parameters defined in the Requirements for Internet Hosts RFC. It also provides for dynamic address allocation, which allows a network to make maximum use of a limited set of addresses.

This chapter concludes our introduction to the architecture, protocols, and services of a TCP/IP network. In the next chapter, we begin to look at how to install a TCP/IP network by examining the process of planning an installation.

[17] RFC 791, Internet Protocol, Jon Postel, ISI, 1981, page 7.

[18] Sun’s Network Information Service (NIS) is an improved technique for accessing the host table. NIS is discussed later in this chapter.

[19] There is no relationship between the organizational and geographic domains in the U.S. Each system belongs to either an organizational domain or a geographic domain, not both.

[20] Figure 3-1 shows two second-level domains: nih under gov and wrotethebook under com.

[21] The root domain is identified by a single dot; i.e., the

root name is a null name written simply as ".".

[22] NIS was formerly called the “Yellow Pages,” or yp. Although the name has changed, the abbreviation yp is still used.

[23] Most standard TCP/IP applications are assigned a well-known port so that remote systems know how to connect the service.

[24] The address doesn’t have anything to do with whether a system is store and forward or direct delivery. It just happens that UUCP provides an address that helps to illustrate this point.

[25] The /etc/services file lists two different ports for IMAP: 143 and 220. Port 220 is used by IMAP 3. IMAP 4 uses port number 143, which is the same port used by IMAP 2

[26] MIME is also an integral part of the Web and HTTP.

[27] Go to ftp://ftp.isi.edu/in-notes/iana/assignments/media-types to retrieve the file media-types.

[28] See Appendix E for a list of the sendmail command-line arguments.

[29] See Chapter 10 for the details of sendmail configuration.

[30] Like ARP, RARP is a Network Access Layer protocol that uses physical network services residing below the Internet Layer. See the discussion of TCP/IP protocol layers in Chapter 1.

[33] This address is useful because, unlike the normal broadcast address, it doesn’t require the system to know the address of the network it is on.