Now our attention turns to configuring local network servers. As with name service, these servers are not strictly required for the network to operate, but they provide services that are central to the network’s purpose.

There are many network services—many more than can be covered in this chapter. Here we concentrate on servers that provide essential services for local clients. The services covered in this chapter are:

The Network File System (NFS)

The Line Printer Daemon (LPD) and the Line Printer (LP) service

Windows file and print services (Samba)

The Network Information Service (NIS)

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)

The Post Office Protocol (POP)

Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP)

All of these software packages are designed to provide service to systems within your organization and are not intended to service outsiders. Essential services that are as important to external users as they are to in-house users, such as email, web service, and name service, are covered in separate chapters.

We begin our discussion of local network services with NFS, which is the server that provides file sharing on Unix networks.

The Network File System (NFS) allows directories and files to be shared across a network. It was originally developed by Sun Microsystems but is now supported by virtually all Unix and many non-Unix operating systems. Through NFS, users and programs can access files located on remote systems as if they were local files. In a perfect NFS environment, the user neither knows nor cares where files are actually stored.

NFS has several benefits:

It reduces local disk storage requirements because a server can store a single copy of a directory that is fully accessible to everyone on the network.

It simplifies central support tasks—files can be updated centrally yet be available throughout the network.

It allows users to use familiar Unix commands to manipulate remote files instead of learning new commands. There is no need to use

ftporrcpto copy a file between hosts on the network;cpworks fine.

There are two sides to NFS: a client side and a server side. The client is the system that uses the remote directories as if they were part of its local filesystem. The server is the system that makes the directories available for use. Attaching a remote directory to the local filesystem (a client function) is called mounting a directory. Offering a directory for remote access (a server function) is called sharing or exporting a directory.[97] Frequently, a system runs both the client and the server NFS software. In this section we’ll look at how to configure a system to export and mount directories using NFS.

If you’re responsible for an NFS server for a large site, you should take care in planning and implementing the NFS environment. This chapter describes how NFS is configured to run on a client and a server, but you may want more details to design an optimal NFS environment. For a comprehensive treatment, see Managing NFS and NIS by Hal Stern (O’Reilly & Associates).

The Network File System is run by several daemons, some performing client functions and some performing server functions. Before we discuss the NFS configuration, let’s look at the function of the daemons that run NFS on a Solaris 8 system:

nfsd [nservers]The NFS daemon,

nfsd, runs on NFS servers. This daemon services the client’s NFS requests. Thenserversoption specifies how many daemons should be started.mountdThe NFS mount daemon,

mountd, processes the clients’ mount requests. NFS servers run the mount daemon.nfslogdThe NFS logging daemon,

nfslogd, logs activity for exported filesystems. NFS servers run the logging daemon.rquotadThe remote quota server,

rquotad, provides information about user quotas on remote filesystems that is then displayed by thequotacommand. The remote quota server is run on both clients and servers.lockdThe lock daemon,

lockd, handles file lock requests. Both clients and servers run the lock daemon. Clients request file locks, and servers grant them.statdThe network status monitor daemon,

statd, is required bylockdto provide monitoring services. In particular, it allows locks to be reset properly after a crash. Both clients and servers runstatd.

On a Solaris 8 system, the daemons necessary to run NFS are

found in the /usr/lib/ nfs directory. Most of these

daemons are started at boot time by two scripts located in the

/etc/init.d directory,

nfs.client and nfs.server . The nfs.client script starts the

statd and lockd programs.[98]

NFS server systems run those two daemons, plus the NFS server

daemon (nfsd), the NFS logging

daemon (nfslogd), and the mount

server daemon (mountd). On Solaris

systems, the nfs.server script starts mountd, nfslogd, and 16 copies of nfsd. Solaris systems do not normally start

rquotad at boot time. Instead,

rquotad is started by inetd, as this grep of the /etc/inetd.conf file shows:

$ grep rquotad /etc/inetd.conf

rquotad/1 tli rpc/datagram_v wait root /usr/lib/nfs/rquotad rquotadEach system has its own technique for starting these daemons. If some of the daemons aren’t starting, ensure your startup scripts and your inetd.conf file are correct.

The first step in configuring a server is deciding which filesystems will be shared and what restrictions will be placed on them. Only filesystems that provide a benefit to the client should be shared. Before you share a filesystem, think about what purpose it will serve. Some common reasons for sharing filesystems are:

To provide disk space to diskless clients

To prevent unnecessary duplication of the same data on multiple systems

To provide centrally supported programs and data

To share data among users in a group

Once you’ve selected the filesystems you’ll share, you must configure them for sharing using the appropriate commands for your system. The following section emphasizes the way this is done on Solaris systems. It is very different on Linux systems, which are covered later. Check your system’s documentation to find out exactly how it implements NFS file sharing.

On Solaris systems, directories are exported using the

share command.

A simplified syntax for the share command is:

share -F nfs[-ooptions]pathname

where pathname is the path of the

directory the server is offering to share with its clients, and

options are the access controls for that directory. The options

are:

rwThe

rwoption grants read and write access to the shared filesystem. It can be specified in the formrw=accesslistto identify the systems that are granted this access. When used in this way, only the systems identified in the list are given access to the filesystem. If the access list is not provided with therwoption, all hosts are given read/write access to the filesystem.roThis option limits access to read-only. It also can be specified with an access list, e.g.,

ro=accesslist. When the access list is included, only the systems on the list have access and that access is limited to read-only. If the access list is not provided with therooption, all hosts are given read-only access to the filesystem, which is the default if no options are specified.aclokThis option grants full access to all clients, which could open up a security hole. This option is documented on the Solaris system, but it should never be used. It is intended to provide backward compatibility with a version of NFS that no longer exists.

-

anon=uid Defines the UID used for users who do not provide a valid user ID.

-

index=file Tells NFS to use a web-style index file instead of a directory listing for this filesystem.

-

log[=tag] Enable logging. If an optional tag is specified, it must match a tag defined in the /etc/nfs/nfslog.conf file.

-

nosub Do not allow clients to mount subdirectories. The default is

sub, which allows subdirectories to be mounted.-

nosuid Do not allow clients to create setuid or setgid files on this filesystem. The default is

suid, which allows clients to create setuid and setgid files.-

public Use the public file handle for this filesystem.

root=accesslistThis option allows the root users from the systems specified by the access list to have root access to the filesystem.

-

sec=type Defines the type of authentication used for accessing this filesystem.

typeis a colon-separated list of NFS security modes. For access to be successful, the client must support at least one of the security modes identified in thetypelist. The possibletypevalues are:-

sys Use clear-text user IDs and group IDs to control access to the filesystem. This is the same as traditional Unix file permissions, which are granted based on UID and GID, with the exception that the UID and GID are passed over the network and the server must trust the remote source.

-

dh Use Diffie-Hellman public key cryptography for authentication.

-

krb4 Use the Kerberos Version 4 for authentication.

-

none Do not use authentication. When no authentication is used, all users access the filesystem as user nobody.

-

-

window=seconds Defines the maximum lifetime in seconds that the NFS server will permit for a

dhorkrb4authentication. The server rejects any security credentials that have a longer lifetime value.secondsdefaults to 30000.

A few of the options contain an access list. The access list is a colon-separated list that identifies computers by individual hostnames, individual IP addresses, or by the domain, network, or NIS netgroup to which the hosts belong. The syntax of these list elements is:

-

hostname This is any hostname that resolves to an IP address. It can be a fully qualified name or just the hostname as long as the name as written will resolve to an IP address. If the hostname can be found in the local host table, the short name can be used. If the name must be resolved by DNS, the fully qualified hostname, with its domain name attached, should be specified. However, fully qualified names should not be used if your system does not use DNS, i.e., if your system relies exclusively on NIS.

-

address -

netgroup If an NIS netgroup name is used, the option applies to every system within that netgroup. Netgroup names look identical to unqualified hostnames and are easy to confuse with hostnames. Netgroup names should only be used if your system uses NIS.

-

.domain A domain name is used to apply the option to every system within that domain. When a domain name is used, it is preceded by a dot (

.). Thus .wrotethebook.com applies to every system in the wrotethebook.com domain. Domain names should be used only if your server uses DNS.-

@network[/prefix] A network address is used to apply an option to every system within the network. When a network address is used, it must be preceded by an at-sign (

@). An optional network prefix can be used with the address to clearly define the network mask.

The rw and ro options can be combined to grant

different levels of access to different clients. For example:

share -F nfs -o rw=crab:horseshoe ro /usr/man share -F nfs -o rw=rodent:crab:horseshoe:jerboas /export/home/research

The first share command

grants read and write access to crab and

horseshoe, and read-only access to all other

clients. On the other hand, the second share command grants read/write access to

rodent, crab,

horseshoe, and jerboas,

and no access of any kind to any other client.

The share command does not survive a boot. Put the share commands in the

/etc/dfs/dfstab file to make sure that the

filesystems continue to be offered to your clients even if the

system reboots. Here is a sample dfstab file

containing our two share

commands:

% cat /etc/dfs/dfstab

# place share(1M) commands here for automatic execution

# on entering init state 3.

#

# share [-F fstype] [ -o options] [-d "<text>"] <pathname> [resource]

# .e.g.,

# share -F nfs -o rw=engineering -d "home dirs" /export/home2

share -F nfs -o rw=crab:horseshoe ro /usr/man

share -F nfs -o rw=rodent:crab:horseshoe:jerboas /export/home/researchThe share command, the

dfstab file, and even the terminology “share”

are Solaris-specific. Most Unix systems say that they are

exporting files, instead of

sharing files, when they are offering files to

NFS clients. Furthermore, they do not use the share command or the

dfstab file; instead, they offer filesystems

through the /etc/exports file. Linux is an

example of such a system.

The /etc/exports file is the NFS server configuration file for Linux systems. It controls which files and directories are exported, which hosts can access them, and what kinds of access are allowed. A sample /etc/exports file might contain these entries:

/usr/man crab(rw) horseshoe(rw) (ro) /usr/local (ro) /home/research rodent(rw) crab(rw) horseshoe(rw) jerboas(rw)

This sample file says that:

/usr/man can be mounted by any client, but it can be written to only by crab and horseshoe. Other clients have read-only access.

/usr/local can be mounted by any client, with read-only access.

/home/research can be mounted only by the hosts rodent, crab, horseshoe, and jerboas. These four hosts have read/write access.

The options used in each of the entries in the /etc/exports file determine what kinds of access are allowed. The information derived from the sample file is based on the options specified on each line in the file. The general format of the entries is as follows:

directory[host(option)]...

directory names the directory or

file that is available for export. The

host is the name of the client granted

access to the exported directory, while the

option specifies the type of access being

granted.

In the sample /etc/exports file shown

above, the host value is either the name

of a single client or it is blank. When a single hostname is used,

access is granted to the individual client. If no hostvalue is

specified, the directory is exported to everyone. Like Solaris,

Linux also accepts values for domains, networks, and netgroups,

although the syntax is slightly different. Valid host values are:

Individual hostnames such as crab or crab.wrotethebook.com.

Domain wildcards such as *wrotethebook.com for every host in the wrotethebook.com domain.

IP address/address mask pairs such as 172.16.12.0/255.255.255.0 for every host with an address that begins with 172.16.12.

Net groups such as @group1.

Notice that in Linux, domain names begin with an asterisk (*), instead of the dot used in Solaris.

Also note that the at-sign begins a netgroup name, whereas in

Solaris the at-sign is used at the beginning of a network

address.

The options used in the sample /etc/exports file are:

roRead-only prevents NFS clients from writing to this directory. Attempts by clients to write to a read-only directory fail with the message “Read-only filesystem” or “Permission denied.” If

rois specified without a client hostname, all clients are granted read-only access.rwRead/write permits clients to read and write to this directory. When specified without hostname, all clients are granted read/write access. If a hostname is specified, only the named host is given read/write permission.

Although specific hosts are granted read/write access to some of these directories, the access granted to individual users of those systems is controlled by standard Unix user, group, and world file permissions based on the user’s user ID (UID) and group ID (GID). NFS trusts that a remote host has authenticated its users and assigned them valid UIDs and GIDs. Exporting files grants the client system’s users the same access to the files they would have if they directly logged into the server. This assumes, of course, that both the client and the server have assigned exactly the same UIDs and GIDs to the same users, which is not always the case. If both the client and the server assign the same UID to a given user, for example, if Craig is assigned 501 on both systems, then both systems properly identify Craig and grant him appropriate access to his files. On the other hand, if the client assigns Craig a UID of 501 and the server has assigned that UID to Michael, the server will grant Craig access to Michael’s files as if Craig owned those files. NFS provides several tools to deal with the problems that arise because of mismatched UIDs and GIDs.

One obvious problem is dealing with the root account. It is

very unlikely that you want people with root access to your clients

to also have root access to your server. By default, NFS prevents

this with the root_squash

setting, which maps requests that contain the root

UID and GID to the nobody UID and GID. Thus if

someone is logged into a client as root, they are only granted world

permissions on the server. You can undo this with the no_root_squash setting, but no_root_squash opens a potential security

hole.

Map other UIDs and GIDs to nobody with

the squash_uids , squash_gids, and

all_squash options. all_squash maps every user of a client

system to the user nobody. squash_uids and squash_gids map specific UIDs and GIDs.

For example:

/pub (ro,all_squash) /usr/local/pub (squash_uids=0-50,squash_gids=0-50)

The first entry exports the /pub directory with read-only access to every client. It limits every user of those clients to the world permissions granted to nobody, meaning that the only files the users can read are those that have world read permission.

The second entry exports /usr/local/pub

to every client with default read/write permission. The squash_uid and squash_gid options in the example show

that a range of UIDs and GIDs can be specified in some

options.[99] A single UID or GID can be defined with these options,

but it is frequently useful to affect a range of values with a

single command. In the example we prevent users from accessing the

directory with a UID or GID that is 50 or less. These low numbers

are usually assigned to non-user accounts. For example, on our Linux

system, UID 10 is assigned to uucp. Attempting

to write a file as uucp would cause the file to

be written with the owner mapped to nobody.

Thus the user uucp would be able to write to

the /usr/local/pub directory only if that

directory had world write permission.

It is also possible to map every user from a client to a specific user ID or

group ID. The anonuid and

anongid options provide this

capability. These options are most useful when the client has only

one user and does not assign that user a UID or GID, for example, in the case of a Microsoft

Windows PC running NFS. PCs generally have only one user and they

don’t use UIDs or GIDs. To map the user of a PC to a valid user ID

and group ID, enter a line like this in the

/etc/exports file:

/home/alana giant(all_squash,anonuid=1001,anongid=1001)

In this example, the hostname of Alana’s PC is

giant. The entry grants that client read/write

access to the directory /home/alana. The

all_squash option maps every

request from that client to a specific UID, but this time, instead

of nobody, it maps to the UID and the GID

defined by the anonuid and

anongid options. Of course, for

this to work correctly, 1001:1001 should be the UID and GID pair

assigned to alana in the

/etc/passwd file.

A single mapping is sufficient for a PC, but it might not

handle all of the mapping needed for a Unix client. Unix clients

assign their users UIDs and GIDs. Problems occur if those differ

from the UIDs and GIDs assigned to those same users on the NFS

server. Use the map_static option

to point to a file that maps the UIDs and GIDs for a specific

client. For example:

/export/oscon oscon(map_static=/etc/nfs/oscon.map)

This entry says that the /export/oscon

directory is exported to the client oscon with

read/write permission. The map_static option points to a file on the

server named /etc/nfs/oscon.map that maps the

UIDs and GIDs used on oscon to those used on

the server. The oscon.map file might contain

the following entries:

# UID/GID mapping for client oscon # remote local comment uid 0-50 - #squash these gid 0-50 - #squash these uid 100-200 1000 #map 100-200 to 1000-1100 gid 100-200 1000 #map 100-200 to 1000-1100 uid 501 2001 #map individual user gid 501 2001 #map individual user

The first two lines map the UIDs and GIDs from 0 to 50 to the user nobody. The next two lines map all of the client UIDs and GIDs in the range of 100 to 200 to corresponding numbers in the range of 1000 to 1100 on the server. In other words, 105 on the client maps to 1005 on the server. This is the most common type of entry. On most systems, existing UIDs and GIDs have been assigned sequentially. Often, several systems have assigned the UIDs and GIDs sequentially from 101 to different users in a completely uncoordinated manner. This entry maps the users on oscon to UIDs and GIDs starting at 1000. Another file might map the 100 to 200 entries of another client to UIDs and GIDs starting at 2000. A third file might map yet another client to 3000. This type of entry allows the server to coordinate UIDs and GIDs where no coordination exists. The last two lines map an individual user’s UID and GID. This is less commonly required, but it is possible.

After defining the directories in the /etc/exports

file, run the exportfs command to

process the exports file and to build

/var/lib/nfs/xtab. The

xtab file contains information about the

currently exported directories, and it is the file that mountd reads when processing client mount

requests. To process all of the entries in the

/etc/exports file, run exportfs with the -a command-line

option:

# exportfs -aThis command, which exports everything in the

exports file, is normally run during the boot

from a startup script. To force changes in the

/etc/exports file to take effect without

rebooting the system, use the -r

argument:

# exportfs -rThe -r switch synchronizes

the contents of the exports file

and the xtab file. Items that have been added

to the exports file are added to the

xtab file, and items that have been deleted are

removed from xtab.

The exportfs command can

export a directory that is not listed in the

/etc/exports file. For example, to temporarily export /usr/local to

the client fox with read/write permission,

enter this command:

# exportfs fox:/usr/local -o rwAfter the client has completed its work with the temporarily

exported filesystem, the directory is removed from the export list

with the -u option, as

shown:

# exportfs -u fox:/usr/localThe -u option can be

combined with the -a option to

completely shut down all exports without terminating the NFS

daemon:

# exportfs -uaOnce the server exports or shares the appropriate filesystems, the clients can mount and use those filesystems. The next section looks at how an NFS client system is configured.

Some basic information is required before you can decide which NFS directories to mount on your system. You need to know which servers are connected to your network and which directories are available from those servers. A directory cannot be mounted unless it is first exported by a server.

Your network administrator is a good source for this information. The administrator can tell you what systems are providing NFS service, what directories they are exporting, and what these directories contain. If you are the administrator of an NFS server, you should develop this type of information for your users. See Chapter 4 for advice on planning and distributing network information.

On Solaris and Linux systems, you can also obtain information

about the shared directories directly from the servers by using the

showmount command. The NFS servers are usually the same centrally

supported systems that provide other services such as mail and DNS.

Select a likely server and query it with the command showmount -e

hostname. In response to this command, the

server lists the directories that it exports and the conditions

applied to their export.

For example, a showmount -e

query to jerboas produces the following

output:

% showmount -e jerboas

export list for jerboas:

/usr/man (everyone)

/home/research rodent,crab,limulus,horseshoe

/usr/local (everyone)The export list shows the NFS directories exported by jerboas as well as who is allowed to access those directories. From this list, rodent’s administrator may decide to mount any of the directories offered by jerboas. Our imaginary administrator decides to:

Mount /usr/man from jerboas instead of maintaining the manpages locally.

Mount /home/research to more easily share files with other systems in the research group.

Mount the centrally maintained programs in /usr/local.

These selections represent some of the most common motivations for mounting NFS directories:

Saving disk space

Sharing files with other systems

Maintaining common files centrally

The extent to which you use NFS is a personal choice. Some people prefer the greater personal control you get from keeping files locally, while others prefer the convenience offered by NFS. Your site may have guidelines for how NFS should be used, which directories should be mounted, and which files should be centrally maintained. Check with your network administrator if you’re unsure about how NFS is used at your site.

A client must mount a shared directory before using it. “Mounting” the directory attaches it to the client’s filesystem hierarchy. Only directories offered by the servers can be mounted, but any part of the offered directory, such as a subdirectory or a file, can be mounted.

NFS directories are mounted using the mount command. The general structure of

the mount command is:

mounthostname:remote-directory local-directory

The hostname identifies an NFS

server, and the remote-directory

identifies all or part of a directory offered by that server. The

mount command attaches that

remote directory to the client’s filesystem using the directory name

provided for local-directory. The

client’s local directory, called the mount point, must be created

before mount is executed. Once

the mount is completed, files located in the remote directory can be

accessed through the local directory exactly as if they were local

files.

For example, assume that jerboas.wrotethebook.com is an NFS server and that it shares the files shown in the previous section. Further assume that the administrator of rodent wants to access the /home/research directory. The administrator simply creates a local /home/research directory and mounts the remote /home/research directory offered by jerboas on this newly created mount point:

# mkdir /home/research # mount jerboas:/home/research /home/research

In this example, the local system knows to mount an NFS

filesystem because the remote directory is preceded by a hostname

and NFS is the default network filesystem for this client. NFS is

the most common default network filesystem. If your client system

does not default to NFS, specify NFS directly on the mount command line. On a Solaris 8 system, the -F switch is used to identify the

filesystem type:

# mount -F nfs jerboas:/home/research /home/researchOn a Linux system the -t

switch is used:

# mount -t nfs jerboas:/home/research /home/researchOnce a remote directory is mounted, it stays attached to the

local filesystem until it is explicitly dismounted or the local

system reboots. To dismount a directory, use the umount command. On the umount command line, specify either the

local or remote name of the directory that is to be dismounted. For

example, the administrator of rodent can

dismount the remote jerboas:/home/research

filesystem from the local /home/research mount

point, with either:

# umount /home/researchor:

# umount jerboas:/home/researchBooting also dismounts NFS directories. Because systems frequently wish to mount the same filesystems every time they boot, Unix provides a system for automatically remounting after a boot.

Unix systems use the information provided in a special table to remount all types of filesystems, including NFS directories, after a system reboot. The table is a critical part of providing users consistent access to software and files, so care should be taken whenever it is modified. Two different files with two different formats are used for this purpose by the different flavors of Unix. Linux and BSD systems use the /etc/fstab file, and Solaris, our System V example, uses the /etc/vfstab file.

The format of the NFS entries in the Solaris vfstab file is:

filesystem-mountpointnfs - yesoptions

The various fields in the entry must appear in the order shown

and be separated by whitespace. The items not in italics (both

dashes and the words nfs and

yes) are keywords that must

appear exactly as shown. filesystem is

the name of the directory offered by the server,

mountpoint is the pathname of the local

mount point, and options are the mount

options discussed below. A sample NFS vfstab

entry is:

jerboas:/home/research - /home/research nfs - yes rw,soft

This entry mounts the NFS filesystem

jerboas:/home/research on the local mount point

/home/research. The filesystem is mounted with

the rw and soft options set. We previously discussed

the commonly used read/write (rw)

and read-only (ro) options, and

there are many more NFS options. The NFS mount options available on Solaris systems are:

remountIf the filesystem is already mounted read-only, remount the filesystem as read/write.

-

soft If the server fails to respond, return an error and don’t retry the request.

-

timeo=n Defines the number of seconds to wait for a timeout before issuing an error.

-

hard If the server fails to respond, retry until it does respond. This is the default.

-

bg Do the retries in background mode, which allows the boot to proceed.

-

fg Do the retries in foreground mode. This option could hang the boot process while the mount is being retried. For this reason,

fgis used primarily for debugging.-

intr Allow a keyboard interrupt to kill a process that is hung waiting for the server to respond. Hard-mounted filesystems can become hung because the client retries forever, even if the server is down. This is a default.

-

nointr Don’t allow keyboard interrupts. In general, this is a bad idea.

-

nosuid Do not allow an executable stored on the mounted filesystem to run

setuid. This improves security but may limit utility.-

acdirmax=n Cache directory attributes for no more than

nseconds. The default is to hold cache values for a maximum of 60 seconds. Repeated requests for filesystem attributes is one of the leading contributors to NFS traffic. Caching this information helps to reduce the traffic.-

acdirmin=n Cache directory attributes for at least

nseconds. The default is 30 seconds.-

acregmax=n Cache file attributes for no more than

nseconds. The default is 60 seconds.-

acregmin=n Cache file attributes for at least

nseconds. The default is 3 seconds.-

actimeo=n Sets a single value for

acdirmax,acdirmin,acregmax, andacregmin.-

grpid Use the group ID of the parent directory when creating new files. If this option is not set, the effective GID of the calling process is used.

-

noac Do not cache information. The default is to use caching, which can be specified with the

acoption.-

port=n Identifies the IP port number used by the server.

-

posix Use POSIX standards for the filesystem. POSIX is a wide-ranging Unix interoperability standard that includes many standards for filesystems, such as the maximum length of filenames and how file locks are set.

-

proto=protocol Specifies the transport protocol that will be used by NFS.

-

public Use the public file handle when connecting to the NFS server.

-

quota Use

quotato enforce user quotas on this filesystem.-

noquota Do not use

quotato enforce user quotas on this filesystem.-

retrans=n Defines the number of times NFS will retransmit when a connectionless transport protocol is used.

-

retry=n Defines the number of times a mount attempt will be retried. The default is to retry 10,000 times.

-

rsize=n Defines the size of the read buffer as

nbytes. The default for NFS version 3 is 32,768 bytes.-

sec=type Specifies the type of security used for NFS transactions. The type values supported on the Solaris 8

mountcommand are the same as those listed for thesharecommand:sys,dh,krb4, ornone.-

wsize=n Sets the size of the write buffer to

nbytes. The default is 32768 bytes for NFS version 3.-

vers=version Specifies the version of NFS that should be used for this mount. By default, the system automatically selects the latest version supported by both the client and the server.

On the Solaris system, the filesystems defined in the

vfstab file are mounted by a mountall command located in a startup file. On Linux systems,

the startup file contains a mount

command with the -a flag set,

which causes Linux to mount all filesystems listed in

fstab.[100]

The format of NFS entries in the /etc/fstab file is:

filesystem mountpointnfsoptions

The fields must appear in the order shown and must be

separated by whitespace. The keyword nfs is required for NFS filesystems.

filesystem is the name of the directory

being mounted. mountpoint is the pathname

of the local mount point. options are any

of the Linux mount options.

Linux uses most of the same NFS mount options as Solaris.

rsize, wsize, timeo, retrans, acregmin, acregmax, acdirmin, acdirmax, actimeo, retry, port, bg, fg,

soft, hard, intr, nointr, ac, noac, and posix are all options that Linux has in

common with Solaris. In addition to these, Linux uses:

-

mountport=n Defines the port to be used by

mountd.-

mounthost=name Identifies the server running

mountd.-

mountprog=n Defines the RPC program number used by

mountdon the remote host.-

mountvers=n Defines the RPC version number used by

mountdon the remote host.-

nfsprog=n Defines the RPC program number used by

nfsdon the remote host.-

nfsvers=n Defines the RPC version number used by

nfsdon the remote host.-

namlen=n Defines the maximum length of the filenames supported by the remote server.

-

nocto Do not retrieve attributes when creating a file. The default is to retrieve the attributes, which can be specified with the

ctooption.-

tcp Specifies that NFS should use TCP as its transport protocol.

-

udp Specifies that NFS should use UDP as its transport protocol.

-

nolock Prevents the system from starting

lockd. The default is to runlockd, which can be requested with thelockoption.

Finally, there are several options that are not specific to

NFS and can be used on the mount

command for any type of filesystem. Table 9-1 lists the common

mount options used

on Linux systems.

Table 9-1. Common mount options

Option | Function |

|---|---|

async | Use asynchronous file I/O, which acknowledges writes as soon as they are received to improve performance. |

auto | Mount when the -a option is used. |

dev | Allow character and block special devices on the filesystem. |

exec | Permit execution of files from the filesystem. |

noauto | Don’t mount with the -a option. |

nodev | Don’t allow character and block special devices on the filesystem. |

noexec | Don’t allow execution of files from the filesystem. |

nosuid | Don’t allow programs stored on the filesystem to run setuid or setgid. |

nouser | Only root can mount the filesystem. |

remount | Remount a mounted filesystem with new options. |

ro | Mount the filesystem read-only. |

rw | Mount the filesystem read/write. |

suid | Allow programs to run setuid or setgid. |

sync | Use synchronous filesystem I/O, which acknowledges writes only after they are written to disk to improve reliability. |

user | Permit ordinary users to mount the filesystem. |

atime | Update inode access time for every access. |

noatime | Do not update inode access time. |

defaults | Set the rw, suid, dev, exec, auto, nouser, and async options. |

A grep of

fstab shows sample NFS entries.[101]

% grep nfs /etc/fstab

jerboas:/usr/spool/mail /usr/spool/mail nfs rw 0 0

jerboas:/usr/man /usr/man nfs rw 0 0

jerboas:/home/research /home/research nfs rw 0 0The grep shows that there

are three NFS filesystems contained in the

/etc/fstab file. The mount -a command in the boot script

remounts these three directories every time the system boots.

The vfstab and fstab files are the most common methods used for mounting filesystems at boot time. There is another technique that automatically mounts NFS filesystems, but only when they are actually needed. It is called automounter.

An automounter is a feature available on most NFS clients. Two varieties of automounters are in widespread use: autofs and amd. The Automounter Filesystem (autofs) is the automounter implementation that comes with Solaris and Linux, and it is the implementation we cover in this section. Automounter Daemon (amd) is available for many Unix versions and is included with Linux but not with Solaris. To find out more about amd, see Linux NFS and Automounter Administration written by Erez Zadok, the amd maintainer. In this section, automounter and automounter daemon refer to the version of autofs that comes with Solaris 8.

The automounter configuration files are called maps. Three basic map types are used to define the automounter filesystem:

- Master map

The configuration file read by

automount. It lists all of the other maps that are used to define the autofs filesystem.- Direct map

A configuration file that lists the mount points, pathnames, and options of filesystems that are to be mounted by the automounter daemon (

automountd).- Indirect map

A configuration file that contains pathnames and “relative” mount points. The mount points are relative to a directory path declared in the master map. How indirect maps are used will become clear in the examples.

On Solaris systems the automounter daemon (automountd) and the automount command are started by the

/etc/init.d/autofs script. The script is run with the start option to start automounter, i.e.,

autofs start. It is run with the

stop option to shut down

automounter. automount and automountd are two distinct, separate

programs. automountd runs as a

daemon and dynamically mounts filesystems when they are needed.

automount processes the

auto_master file to determine the filesystems

that can be dynamically mounted.

To use automounter, first configure the /etc/auto_master file. Entries in the auto_master file have this format:

mount-point map-name options

The Solaris system comes with a default

auto_master file preconfigured. Customize the file for your

configuration. Comment out the +auto_master entry unless you run NIS+ or

NIS and your servers offer a centrally maintained

auto_master map. Also ignore the /xfn entry, which is for creating a

federated (composite) name service. Add an entry for your direct map.

In the example, this is called auto_direct. Here is

/etc/auto_master after our modifications:

# Master map for automounter # #+auto_master #/xfn -xfn /net -hosts -nosuid /home auto_home /- auto_direct

All lines that begin with a sharp sign (#) are comments, including the +auto_master and /xfn lines we commented out. The first real

entry in the file specifies that the shared filesystems offered by

every NFS server listed in the /etc/hosts file

are automatically mounted under the /net

directory. A subdirectory is created for each server under

/net using the server’s hostname. For example,

assume that jerboas is listed in the

hosts file and that it exports the

/usr/local directory. This auto_master entry automatically makes that

remote directory available on the local host as

/net/jerboas/usr/local.

The second entry automatically mounts the home directories

listed in the /etc/auto_home map under the

/home directory. A default

/etc/auto_home file is provided with the Solaris

system. Comment out the +auto_home

entry found in the default file. It is used only if you run NIS+ or

NIS and your servers offer a centrally maintained

auto_home map. Add entries for individual user

home directories or for all home directories from specific servers.

Here is a modified auto_home map:

# Home directory map for automounter # #+auto_home craig crab:/export/home/craig * horseshoe:/export/home/&

The first entry mounts the

/export/home/craig filesystem shared by

crab on the local mount point

/home/craig. The auto_home

map is an indirect map, so the mount point specified in

the map (craig) is relative to the

/home mount point defined in the

auto_master map. The second entry mounts every

home directory found in the /export/home

filesystem offered by horseshoe to a “like-named”

mount point on the local host. For example, assume that

horseshoe has two home directories,

/export/home/daniel and

/export/home/kristin. Automounter makes them both

available on the local host as /home/daniel and

/home/kristin. The asterisk (*) and the ampersand (&) are wildcard characters used

specifically for this purpose in autofs maps.

That’s it for the auto_home map. Refer back to the auto_master map. The third and final entry in the /etc/auto_master file is:

/- auto_direct

We added this entry for our direct map. The special mount point

/- means that the map name refers

to a direct map. Therefore the real mount points are found in the

direct map file. We named our direct map file

/etc/auto_direct. There is no default direct map

file; you must create it from scratch. The file we created is:

# Direct map for automounter # /home/research -rw jerboas:/home/research /usr/man -ro,soft horseshoe,crab,jerboas:/usr/share/man

The format of entries in a direct map file is:

mount-point options remote filesystem

Our sample file contains two typical entries. The first entry mounts the remote filesystem /home/research offered by the server jerboas on the local mount point /home/research. It is mounted read/write. The second entry mounts the manpages read-only with a “soft” timeout.[102] Note that three servers are specified for the manpages in a comma-separated list. If a server is unavailable or fails to respond within the soft timeout period, the client asks the next server in the list. This is one of the nice features of automounter.

Automounter has four key features: the -hosts map, wildcarding, automounting, and multiple servers. The -hosts map makes every exported filesystem from every server listed in the /etc/hosts file available to the local user. The wildcard characters make it very easy to mount every directory from a remote server to a like-named directory on the local system. Automounting goes hand-in-glove with these two features because only the filesystems that are actually used are mounted. While -hosts and wildcards make a very large number of filesystems available to the local host, automounting limits the filesystems that are actually mounted to those that are needed. The last feature, multiple servers, improves the reliability of NFS by removing the dependence on a single server.

Unix uses NFS to share files; it uses two different tools, the

Line Printer Daemon (lpd) and the Line Printer

(lp) printer service, to provide

printer services for local and remote users. lpd is used on BSD systems and most Linux

systems. lp is used on System V

systems, including Solaris 8. In the following sections we discuss both

tools.

lpd manages the printer spool area and the print queues. lpd is started at boot time from a startup

script. It is generally included in the startup of Linux and BSD

systems by default, so you might not need to add it to your startup

script. For example, it is started by the

/etc/init.d/lpd script on a Red Hat Linux

system.

When lpd starts, it reads the

/etc/printcap file to find out about the

printers available for its use. The printcap

file defines the printers and their characteristics. Configuring

a printcap file is the scariest

part of setting up a Unix print server. (Don’t worry. As we’ll see

later with the Solaris admintool,

most systems provide a GUI tool for configuring printers.) The

printcap file scares system administrators

because the parser that reads the file is very finicky, and the

syntax of the parameters in the file is terse and arcane. Most

parser problems can be avoided by following these rules:

Start each entry with a printer name that begins in the first column. No white-space should precede the first printer name. Multiple printer names can be used if they are separated by pipe characters (|). One entry must have the printer name lp. If you have more than one printer on the server, assign lp to the “default” printer.

Continue printer entries across multiple lines by escaping the newline character at the end of the line with a backslash (\) and beginning the following line with a tab. Take care that no blank space comes after the backslash. The character after the backslash must be the newline character.

Every field, other than the printer name, begins and ends with a colon (:). The character before the backslash on a continued line is a colon and the first character after the tab on the continuation line is a colon.

Begin comments with a sharp sign (#).

The configuration parameters used in a

printcap file describe the characteristics of

the printer. These characteristics are called “capabilities” in the

printcap documentation, but really they are the

printer characteristics that lpd

needs to know in order to communicate with the printer. Parameters

are identified by names that are two characters long and are usually

assigned a value. The syntax of the parameters varies slightly

depending on the type of value they are assigned. Parameters

come in three different flavors:

- Boolean

All printcap Boolean values default to “false.” Specifying a Boolean enables its function. Booleans are specified simply by entering the two-character parameter name in the file. For example,

:rs:enables security for remote users.- Numeric

Some parameters are assigned numeric values. For example,

:br#9600:sets the baud rate for a serial printer.- String

Some parameters use string values. For example,

:rp=laser:defines the name of a remote printer.

A glance at the manpage shows that there are many printcap parameters. Thankfully, you’ll never need to use most of them. Most printer definitions are fairly simple, and most printcap files are small.

Print servers usually have only one or two directly attached printers; any other printers defined in printcap are probably remote printers. Most, if not all, of the printers defined in a client’s printcap are remote printers.

#

# Remote LaserWriter

#

lw:\

:lf=/var/adm/lpd-errs:\

:lp=:rm=horseshoe:rp=lw:\

:sd=/var/spool/lpd-lw:The lw printer in this sample

printcap file is a remote printer. The lf parameter points to the log file used

to log status and error messages. The remote machine to which the

printer is attached is defined by the :rm=horseshoe: parameter, and the name of

the remote printer on that machine is defined by the :rp=lw: parameter. Multiple printers can

use the same log file. The final parameter, sd, defines the spool directory. Each

printer has its own unique spool directory. Defining the remote

printer in the client’s printcap file is all

that is needed to configure an LPD client.

Writing a printcap from scratch is

unnecessary. At most, you will need to tweak the

printcap configuration for your own special

needs. All modern Unix systems have printer configuration tools that

will build the basic printcap for you. The

Red Hat printconf-gui tool is an example.

Launch the printer configuration tool on a Red Hat 7.2 system

running the Gnome desktop by selecting Printer Configuration from

the System menu. When the printconf-gui window opens, click the New

button to add a printer to the printcap file.

The New button launches a printer configuration wizard. Use the

first page of the wizard to define the printer name and the queue

type. Enter the printer name, for example lw,

in the Queue Name box. Then select the Queue Type. Red Hat 7.2

offers five choices:

- Local Printer

Use this type to define a directly attached printer. When Local Printer is selected, the wizard asks you to select the printer port to which the printer is attached. The default is /dev/lp0.

- Unix Printer

Use this type to define a printer located on a remote server that is accessed via the LPD protocol. When Unix Printer is selected, the wizard asks for the name of the remote server and the name of the printer on the remote server.

- Windows Printer

Use this type to define a remote printer that is accessed via the SMB protocol. When Windows Printer is selected, the wizard asks for the IP address of the remote server, the SMB workgroup, and the name of the remote printer, which it calls a share name. The wizard also allows a username and password to be input in case they are required for access to the printer. Printer sharing through SMB is is covered in detail later in this chapter.

- Novell Printer

Use this type to define a remote printer accessed via the NetWare protocols. When Novell Printer is selected, the wizard asks for the name of the server and the printer on that server. A username and password can also be entered if they are required for printer access. To communicate with a Novell printer you must have the NetWare protocols installed on your system.

- JetDirect Printer

Use this type to define a network-attached printer that uses the JetDirect protocol. Primarily, this protocol is used on HP printers that contain a built-in Ethernet interface and that connect directly to the Ethernet cable without going through a server. When JetDirect is selected, the wizard asks for the IP address of the printer and gives you a chance to enter a port number in case the printer is not configured to use the standard JetDirect port.

Finally, the wizard presents you with a selection of hundreds of printer drivers. Most Unix systems use standard PostScript printers. Linux systems, however, are built on commodity PC hardware. PCs use a hodgepodge of different printers. The wizard lets you select the correct driver for your printer by selecting the printer make and then the printer model. Once you select the drive, the configuration is finished and the new printer is installed.

The Red Hat tool is just an example. Future versions of Red Hat will have a newer tool, and other Unix systems have their own tools. The point is not the details of the tool, but the fact that the printcap file is not usually written by hand. It is created by a configuration tool.

Once the printer is configured, print jobs are sent to the line

printer daemon using the Line Printer Remote

(lpr) program. The lpr program creates a control file and

sends it and the print file to lpd. There are many possible lpr command-line arguments, but in general

the command simply identifies the printer and the file to be

printed, as in:

% lpr -Plj ch09This command sends a file called ch09 to

a printer called lj. The printer can be local

or remote. It doesn’t matter as long as the printer is defined in

the printcap file and therefore known to

lpd.

The client software provides commands to allow the user to check the status of the print job. Table 9-2 lists these commands, their syntax, and their meaning.

Table 9-2. Line printer commands

Command | Function |

|---|---|

lpc start [printer] | Starts a new printer daemon. |

lpc status [printer] | Displays printer and queue status. |

lpq -Pprinter [user] [job] | Lists the jobs in the printer’s queue. |

lprm -Pprinter job | Removes a print job from the queue. |

In this syntax, printer is the name

of the printer as defined in the /etc/printcap

file, user is the username of the owner

of a print job, and job is the job number

associated with the print job while it is waiting in the queue. The

keyword all can be used in place

of a printer name in any lpc

command to refer to all printers.

While lpc is primarily for

the system administrator, the status and start commands can be used by anyone. All

the commands shown in Table

9-2 are available to users.

The lpq command displays a list of jobs queued for a printer. Command-line arguments

permit the user to select which printer queue is displayed and to

limit the display from that queue to a specific user’s jobs or even

to a specific job. Here’s an example of displaying the queue for the

printer lp:

$ lpq -Plp

Printer: lp@crab 'Canon'

Queue: 4 printable jobs

Server: pid 1459 active

Unspooler: pid 1460 active

Status: waiting for subserver to exit at 14:17:47.120

Rank Owner/ID Class Job Files Size Time

active alana@crab+458 A 458 /usr/share/printconf 18043 14:16:53

2 micheal@crab+477 A 477 /usr/share/printconf/t 193 14:17:38

3 james@crab+479 A 479 /usr/share/printconf 18259 14:17:43

4 daniel@crab+481 A 481 /usr/share/printconf 18043 14:17:46A queued print job can be removed by the owner of the job with

the lprm command. Assume that daniel

wants to remove print job number 481. He enters the following

command:

$ lprm -Plp 481

Printer lp@crab:

checking perms 'daniel@crab+481'

dequeued 'daniel@crab+481'lpd and lpr were among the first commands created

for Unix to exploit the power of TCP/IP networking. Managing

printers is primarily a system administration task. Only those

aspects of lpd related to remote

printing are covered here.

The Line Printer (LP) print service is used by most System V Unix systems. LP offers the same type of service as LPD.

Traditionally on System V Unix systems, the LP configuration

files are located in the /etc/lp directory. These

files perform the same basic function that the

/etc/printcap file does for LPD. However, the

/etc/lp files are not directly edited by the system

administrator. The files are created and modified using the System V

lpadmin and lpsystem commands.

The lpadmin command adds local printers to the

/etc/lp/printers directory, which makes the

printers available to LP. The basic syntax of adding a new printer is

simple. The -p switch defines the

local name of the printer. The -p

switch is used with either the -v

switch that defines the interface for a local printer or the -s switch that defines the server and printer

name for a remote printer. For example, the following command adds a

local printer named lp connected to the parallel

printer port /dev/lp1:

# lpadmin -plp -v /dev/lp1This command adds a printer locally known as laser that is the lj printer on the remote server crab:

# lpadmin -llaser -s crab!ljThe specific characteristics of a printer added by lpadmin are controlled by the

terminfo file. terminfo is a file that is

almost identical to the printcap file. Like

printcap, it has a great many possible

parameters. For more information on terminfo, see

the manpage.

The lpsystem command manages printer access on System V systems. By default, most System V systems

share all local printers. Remote printer access settings are defined

in the /etc/lp/Systems file, which comes preconfigured with the following

entry:

+:x:-:s5:-:n:10:-:-:Allow all connections

As the comment at its end makes clear, this entry grants all remote systems access to the local printers. The first field defines the name of the host being granted access. When a plus sign (+) is used in this field, it means all hosts.

The fields in an /etc/lp/Systems entry are

separated by colons (:). The field containing an x and all of the fields containing a dash

(-) can be ignored. These fields

are unused.

The fourth field identifies the type of operating system used on

the remote client. It contains either s5 for System V computers that use LP to

print jobs, or bsd for BSD systems

that use LPD.

The n in the sixth field

indicates that this “connection” should never be timed out and removed

from the system. A timeout period in minutes could be entered in this

field, but this is not usually done. Keep the connection available as

long as the local server is up. The 10 is a related value. It indicates that if

a connection to a remote system fails, it should be retried after 10

minutes. This is a good value: it is long enough to give the remote

system a chance to restart after a crash. Both n and 10

are the defaults and don’t usually need to be changed.

Don’t directly edit the /etc/lp/Systems

file. Modify it with the lpsystem

command. To remove a system from the Systems

file, use lpsystem with the

-r

hostname command-line argument, where

hostname is the value in the first field of

the entry you wish to delete. For example, to remove the plus sign (+)

entry from the default /etc/lp/Systems file,

type:

# lpsystem -r +To add an entry to the Systems file, use

the lpsystem command without the

-r option. For example, to add a

BSD system named clock, enter:

# lpsystem -t bsd -y "Linux PC in room 820" clockThe command adds the following entry to the Systems file:

clock:x:-:bsd:-:n:10:-:-:Linux PC in room 820

The -t command-line option

defines the operating system type. The -y option defines the comment;

clock is, of course, the hostname. We accepted

the default values for the timeout and the retry intervals. These

could have been modified from the command line using the -T timeout and

the -R

retry options. See the manpage for lpsystem for more information.

The lpadmin and lpsystem commands are found on most System V

systems, including Solaris. Solaris 8, however, does not rely solely

on these commands and the /etc/lp directory to

configure LP. On a Solaris system, printers are configured through the

/etc/printers.conf file. The lpadmin command will add new printers to the

/etc/printers.conf file, but printers are usually

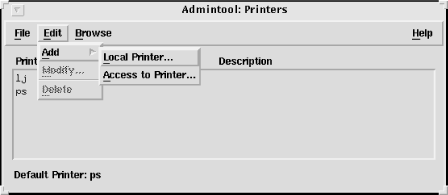

configured through the Printer Manager window of the admintool. Figure 9-1 shows the Printer Manager

window.

Clients select Add, then Access to Printer from the Edit menu, and enter the name of the remote printer and its server in the window that appears. Servers share printers simply by selecting Add, then LocalPrinter in the same menu and configuring a local printer.

All Unix systems provide some technique for sharing printers. The network administrator’s task is to ensure that the printers are accessible via the network and that they are properly secured.

NFS and lpd are file and

print sharing services for Unix systems, and are both

native TCP/IP applications. Microsoft Windows printer and file sharing

applications are based on NetBIOS (Network Basic Input Output System).

Samba bridges these two worlds, providing file and

print sharing for Unix and Windows systems. Samba is the key to

integrating Unix and Windows because it allows a Unix system to be a

file and print server for Windows clients, or to be a client of a

Windows server.

The protocol used between NetBIOS clients and servers is Server Message Block Protocol (SMB). Originally, NetBIOS was a monolithic protocol that took data all the way from the application to the physical network. Today, NetBIOS runs over TCP/IP, which allows NetBIOS applications to run on Unix systems that use TCP/IP.

Two things are needed to run NetBIOS on a TCP/IP network: a protocol to carry NetBIOS data over TCP/IP and a technique to map NetBIOS addresses to TCP/IP addresses. The protocol that transports NetBIOS is NetBIOS over TCP/IP (NBT), which is defined by RFCs 1001 and 1002. Address mapping is handled by a special NetBIOS name server. Samba provides both of these services.

Samba services are implemented as two daemons. The SMB daemon

(smbd ), the heart of Samba, provides the file and printer

sharing services. The NetBIOS name server daemon (nmbd) provides NetBIOS-to-IP-address name

service. NBT requires some method for mapping NetBIOS computer names,

which are the addresses of a NetBIOS network, to the IP addresses of a

TCP/IP network.

Samba is included in most Linux distributions and is installed

during the initial system installation. On a Red Hat system, the

/etc/rc.d/init.d/smb script runs at boot time, and

starts both smbd and nmbd. Samba is not included in Solaris 8, but

the software is available for download from the Internet. Go to http://www.samba.org to select your

nearest download site.

The Samba server is configured by the smb.conf

file. Look in the startup script to see where smbd expects to find the configuration file.

On a Red Hat system, it is /etc/samba/smb.conf.

On a Caldera system, it is /etc/samba.d/smb.conf.

The default used in most Samba documentation is

/usr/local/samba/lib/smb.conf. Use find or check the startup script so you know

where it is on your system.

The smb.conf file is divided into sections. Except for the global section, which defines configuration parameters for the entire server, the sections are named after shares. A share is a resource offered by the server to the clients. It can be either a filesystem or a shared printer.

The best way to learn about the smb.conf file is to look at one. Minus the printers share, which is covered later, the Red Hat smb.conf file contains these active lines:

[global] workgroup = MYGROUP server string = Samba Server printcap name = /etc/printcap load printers = yes printing = lprng log file = /var/log/samba/%m.log max log size = 0 security = user encrypt passwords = yes smb passwd file = /etc/samba/smbpasswd socket options = TCP_NODELAY SO_RCVBUF=8192 SO_SNDBUF=8192 dns proxy = no [homes] comment = Home Directories browseable = no writable = yes valid users = %S create mode = 0664 directory mode = 0775

Two sections of the Red Hat configuration file, global and homes, are listed above. The global section defines parameters that affect the entire server:

-

workgroup Defines the hierarchical grouping of hosts, called a workgroup, of which this server is a member. Replace the MYGROUP name in the example with a meaningful workgroup name of 15 characters or less. Make sure you use a meaningful name. Never use the name MYGROUP or WORKGROUP.

-

server string Defines the descriptive comment for this server that is displayed by the

netviewcommand on DOS clients. Change the string in the example to something meaningful for your system.-

printcap name Defines the location of the printcap file. The printcap file is used to identify the printers that are available to share. The default path is /etc/printcap.

-

load printers Specifies whether or not all the printers in the printcap file are to be shared. The default is

yes, use all the printers defined in the printcap file.nomeans don’t read the printcap file at all. Ifnois specified, all shared printers must be defined individually.-

printing Identifies the Unix printing system used by the server. In the example, it is LPR Next Generation (

lprng), which is an implementation of the standard LPR/LPD system described earlier in this chapter.-

log file Defines the location of the log file. The example contains the

%mvariable,[103] which varies according to the client’s NetBIOS name. This creates a different log file for each client with a file extension that is the client’s NetBIOS name. If the NetBIOS name of the client is crab, the log file is named /var/log/samba/log.crab. If the client’s NetBIOS name is rodent, the log file is /var/log/samba/log.rodent.-

max log size Defines the maximum size of a log file in kilobytes. The default is 5 MB, or 5000 KB. (If the maximum size is exceeded,

smbdcloses the log and renames it with the extension .old.) In the sample configuration, this is set to 0, which means that no maximum size is set for log files.-

security Defines the type of security used. There are four possible settings:

-

share Requests share-level security. This is the lowest level of security. The resource is shared with everyone. It is possible to associate a password with a share, but the password is the same for everyone.

-

user Requests user-level security. Every user is required to enter a username and an associated password. By default, this is the username and password defined in /etc/passwd. The default values for passwords can be changed. See the discussion of passwords later in this section.

-

server Defines server-level security. This is similar to user-level security, but an external server is used to authenticate the username and password. The external server must be defined by the password server option.

-

domain Defines domain-level security. In this scheme, the Linux server joins a Windows NT/2000 domain and uses the Windows NT/2000 domain controller as the server that approves usernames and passwords. Use the password server option to point to the Windows NT/2000 Primary Domain Controller (PDC). Log into the PDC and create an account for the Linux system. Finally, add these lines to the global section on the Linux system:

domain master = no local master = no preferred master = no os level = 0

-

-

encrypt passwords Setting this option to

yescauses Samba to encrypt passwords before they are sent across the network. This makes the server more compatible with Windows clients from Windows 98 on, which default to encrypted passwords, and makes it harder for intruders to sniff passwords from the network. By default, Samba uses clear-text Unix passwords.smb passwd fileThis option points to the location of the smbpasswd file, where encrypted Samba passwords are stored. When encrypted passwords are used, the Samba server must maintain two password files: passwd and smbpasswd. Use the mksmbpasswd.sh script to build the initial smbpasswd file from the passwd file.

-

socket options Defines performance tuning parameters. This option is not required, although setting the send and receive buffers to 8 KB may slightly increase performance. In the case of this sample Red Hat configuration, the

TCP_NODELAYsetting, which causes Samba to send multiple packets with each transfer, has no effect because it is the default for versions of Samba 2.0.4 or higher. See Appendix B of Using Samba, by Kelly, Eckstein, and Collier-Brown (O’Reilly) for a good discussion of Samba performance tuning.-

dns proxy Specifies whether or not

nmbdshould forward unresolved NBNS queries to DNS.

In addition to the options described above, several other parameters are commonly used in the global section; they are shown in Table 9-3.

Table 9-3. Other global section parameters

Option | Function |

|---|---|

deadtime | Defines the timeout for inactive connections. |

debug level | Sets the level of messages written to the log. |

keepalive | Uses keepalives to check on the state of the clients. |

lock directory | Defines the path of the directory where wins.dat, status files, and lock files are stored. |

message command | Defines how smbd handles WinPopup messages. |

name resolve order | Defines the order in which services are queried to resolve NetBIOS names. Possible values are: lmhosts, hosts, wins, and bcast. |

netbios aliases | Defines other names the server will answer to. |

netbios name | Defines the server’s NetBIOS name. |

syslog | Maps debug levels to syslog levels. |

syslog only | Uses syslog instead of Samba log files. |

time server | Tells the server to advertise itself as a Windows time server. |

wins support | Enables the WINS name server. |

As the Red Hat sample configuration demonstrates, many servers come preconfigured with reasonable global parameters to begin running a simple server system. In addition to a preconfigured global section, the Red Hat configuration comes with a preconfigured homes section.

The homes section is a special share section. It tells smbd to permit users to access their home

directories through SMB. Unlike other share sections, which we cover

later, this section does not tell smbd the specific path of the directory

being shared. Instead, smbd uses

the home directory from the /etc/passwd file

based on the username of the user requesting the share. The

configuration parameters in the Red Hat homes

section are:

-

comment Provides a description of the share that is displayed in the comment field of the Network Neighborhood window when this share is viewed on a Windows PC.

-

browseable Specifies whether or not all users may browse the contents of this share.

nomeans that only users with the correct user ID are allowed to browse this share.yesmeans all users, regardless of UID, can browse the share. This parameter controls only browsing; actual access to the contents of the share is controlled by standard Linux file permissions.-

writable Specifies whether or not files can be written to this share. If

yes, the share can be written to. Ifno, the share is read-only. This parameter defines the actions permitted by Samba. Actual permission to write to the directory defined by the share is still controlled by standard Linux file permissions.valid usersThis option lists the users who are allowed to use this share. In this example,

%Scontains the name of the user allowed to access this share.create modeThis option defines the file permissions used when a client creates a file within the homes share.

directory modeThis option defines the permissions used when a client creates a directory within the homes share.

To share a directory through Samba, create a share section in smb.conf that describes the directory and the conditions under which it will be shared. To share a new directory named /usr/doc/pcdocs and the /home/research directory used in the NFS examples, add the following two share sections to the sample smb.conf file:

[pcdocs]

comment = PC Documentation

path = /usr/doc/pcdocs

browseable = yes

writable = no

public = yes

[research]

comment = Research Deptment Shared Directory

path = /home/research

browseable = no

writable = yes

create mode = 0750

hosts allow = horseshoe,jerboas,crab,rodentEach share section is labeled with a meaningful name. This

name is displayed as a folder in the Network Neighborhood window on

client PCs. The example contains some commands we have already

covered and a few new commands. The first new command is path, which defines the path of the

directory being offered by this share.

The pcdocs share also contains the

command public, which grants

everyone access, even if they don’t have a valid username or

password. These public users are granted “guest account” access to

the share. On a Linux system, this means they run as user

nobody and group nobody

and are limited to world permissions.

Files may be written to the research share. The create mode command controls the Unix permissions

used when a client writes a file to the share. In the example, the

permission 0750 specifies that files will be created as

read/write/execute for the owner, read/execute for the group, and no

permissions for the world. A related command, directory mode, defines the permission

used when a client creates a directory within a share. For

example:

directory mode = 0744

This sets the permissions for new directories to

read/write/execute for the owner, read/execute for the group, and

read/execute for the world. This is a reasonable setting that allows

cd and ls to work as expected.

The research share section also contains

a hosts allow command, which defines the clients

that are allowed to access this share. Even if a user has the

correct username and password, that user is allowed to access this

share only from the specified hosts. By default, all hosts are

granted access, and specific access is controlled by the username

and password.

In addition to the hosts

allow command, there is a

hosts deny command that defines computers that

are explicitly denied access to the share. Its syntax is similar to

that of the hosts allow

command.

Combining these two new share sections with the section that came with the Red Hat configuration creates a server that provides access to user home directories, to public directories, and to private directories limited to members of a group. This provides the same services as NFS in a manner that is simpler for Microsoft Windows clients to use. Samba can also be used to share printers with Windows clients.

Shared printers are configured through the smb.conf file. The Red Hat system comes with a smb.conf file that is preconfigured for sharing printers. The following lines occur right after the global and homes sections in the Red Hat smb.conf file:

[printers] comment = All Printers path = /var/spool/samba browseable = no guest ok = no writable = no printable = yes

The printcap and load printers lines in the global section

prepare the server to share the printers defined in the

printcap file. This

printers section makes those printers available

to the clients in a manner similar to the way the

homes section makes every home directory

available to the appropriate user. The Red Hat

printers share section contains five

parameters.

Three of the parameters, comment, browseable, and path, were explained previously. Here,

however, path does not define the

path of a shared file. Instead, it defines the path of the spool

directory for the SMB printers.

We introduce two new parameters in this configuration, the

first of which is printable,

which identifies this share as a printer. The default for this

option is no, meaning that by

default, shares are considered to be file shares instead of printer

shares. To create a printer share, set this option to yes. Setting printable = yes permits clients to write

printer files to the spool directory defined by the path option. Use a create mode command to limit the

permissions of the files created by clients in the spool directory.

For example, create mode = 0700.

The other new line, guest

ok, defines whether or not guest

accounts are permitted access to the resource. This is exactly the

same as the public option

discussed earlier, so these two options are used interchangeably.

no means that the user

nobody cannot send a print job to the printer.

A user must have a valid user account to use the printer. This is

designed to prevent guest users from abusing the printer, but it is

also useful to have a valid username for sorting out print jobs if

you use banner pages and accounting on the server.

Generally, a print server offers all of its printers to all of

its clients. However, individual share sections can be created for

each printer in the same way that they are created for file sharing.

If you don’t want to share every printer, remove the printers

section, set the load printers

option to no, and add individual

share sections for just those printers that you want to

share.

An smb.conf file with a share section for a specific printer might contain:

[global] workgroup = BOOKS server string = Print Server load printers = no security = user [homes] comment = Home Directories browseable = no writable = yes [hp5m] comment = PostScript Laser Printer path = /var/spool/samba browseable = no public = no create mode = 0700 printable = yes printer = lp