Hosts attached to a network—particularly the worldwide Internet—are exposed to a wider range of security threats than are unconnected hosts. Network security reduces the risks of connecting to a network. But by nature, network access and computer security work at cross-purposes. A network is a data highway designed to increase access to computer systems, while security is designed to control access to those systems. Providing network security is a balancing act between open access and security.

The highway analogy is very appropriate. Like a highway, the network provides equal access for all—welcome visitors as well as unwelcome intruders. At home, you provide security for your possessions by locking your house, not by blocking the streets. Likewise, network security requires adequate security on individual host computers. Simply securing the network with a firewall is not enough.

In very small towns where people know each other, doors are often left unlocked. But in big cities, doors have deadbolts and chains. The Internet has grown from a small town of a few thousand users into a big city of millions of users. Just as the anonymity of a big city turns neighbors into strangers, the growth of the Internet has reduced the level of trust between network neighbors. The ever-increasing need for computer security is an unfortunate side effect. Growth, however, is not all bad. In the same way that a big city offers more choices and more services, the expanded network provides increased services. For most of us, security consciousness is a small price to pay for network access.

Network break-ins have increased as the network has grown and become more impersonal, but it is easy to exaggerate the extent of these security breaches. Overreacting to the threat of break-ins may hinder the way you use the network. Don’t make the cure worse than the disease. The best advice about network security is to use common sense. RFC 1244, now replaced by RFC 2196, stated this principle very well:

Common sense is the most appropriate tool that can be used to establish your security policy. Elaborate security schemes and mechanisms are impressive, and they do have their place, yet there is little point in investing money and time on an elaborate implementation scheme if the simple controls are forgotten.

This chapter emphasizes the simple controls that can be used to increase your network’s security. A reasonable approach to security, based on the level of security required by your system, is the most cost-effective—both in terms of actual expense and in terms of productivity.

One of the most important network security tasks, and probably one of the least enjoyable, is developing a network security policy. Most computer people want a technical solution to every problem. We want to find a program that “fixes” the network security problem. Few of us want to write a paper on network security policies and procedures. However, a well-thought-out security plan will help you decide what needs to be protected, how much you are willing to invest in protecting it, and who will be responsible for carrying out the steps to protect it.

The first step toward developing an effective network security plan is to assess the threat that connection presents to your systems. RFC 2196, Site Security Handbook, identifies three distinct types of security threats usually associated with network connectivity:

- Unauthorized access

A break-in by an unauthorized person.

- Disclosure of information

Any problem that causes the disclosure of valuable or sensitive information to people who should not have access to the information.

- Denial of service (DoS)

Any problem that makes it difficult or impossible for the system to continue to perform productive work.

Assess these threats in relation to the number of users who would be affected, as well as to the sensitivity of the information that might be compromised. For some organizations, break-ins are an embarrassment that can undermine the confidence that others have in the organization. Intruders tend to target government and academic organizations that will be embarrassed by the break-in. But for most organizations, unauthorized access is not a major problem unless it involves one of the other threats: disclosure of information or denial of service.

Assessing the threat of information disclosure depends on the type of information that could be compromised. While no system with highly classified information should ever be directly connected to the Internet, systems with other types of sensitive information might be connected without undue hazard. In most cases, files such as personnel and medical records, corporate plans, and credit reports can be adequately protected by network access controls and standard Unix file security procedures. However, if the risk of liability in case of disclosure is great, the host may choose not to be connected to the Internet.

Denial of service can be a severe problem if it impacts many users or a major mission of your organization. Some systems can be connected to the network with little concern. The benefit of connecting individual workstations and small servers to the Internet generally outweighs the chance of having service interrupted for the individuals and small groups served by these systems. Other systems may be vital to the survival of your organization. The threat of losing the services of a mission-critical system must be evaluated seriously before connecting such a system to the network.

An insidious aspect of DoS appears when your system becomes an unwitting tool of the attackers. Through unauthorized access, intruders can place malicious software on your system in order to use your system as a launching pad for attacks on others. This is most often associated with Microsoft systems, but any type of computer system can be a victim. Preventing your system from becoming a tool of evil is an important reason for protecting it.

In his class on computer security, Brent Chapman classifies information security threats into three categories: threats to the secrecy, to the availability, and to the integrity of data. Secrecy is the need to prevent the disclosure of sensitive information. Availability means that you want information and information processing resources available when they are needed; a denial-of-service attack disrupts availability. The need for the integrity of information is equally obvious, but its link to computer security is more subtle. Once someone has gained unauthorized access to a system, the integrity of the information on that system is in doubt. Some intruders just want to compromise the integrity of data; we are all familiar with cases where web vandals gain access to a web server and change the data on the server in order to embarrass the organization that runs the web site. Thinking about the impact network threats have on your data can make it easier to assess the threat.

Network threats are not, of course, the only threats to computer security, or the only reasons for denial of service. Natural disasters and internal threats (threats from people who have legitimate access to a system) are also serious. Network security has had a lot of publicity, so it’s a fashionable thing to worry about, but more computer time has probably been lost because of fires and power outages than has ever been lost because of network security problems. Similarly, more data has probably been improperly disclosed by authorized users than by unauthorized break-ins. This book naturally emphasizes network security, but network security is only part of a larger security plan that includes physical security and disaster recovery plans.

Many traditional (non-network) security threats are handled, in part, by physical security. Don’t forget to provide an adequate level of physical security for your network equipment and cables. Again, the investment in physical security should be based on your realistic assessment of the threat.

One approach to network security is to distribute the responsibility for and control over different segments of a large network to small groups within the organization. This approach involves a large number of people in security and runs counter to the school of thought that seeks to increase security by centralizing control. However, distributing responsibility and control to small groups can create an environment of small, easily monitored networks composed of a known user community. Using the analogy of small towns and big cities, it is similar to creating a neighborhood watch to reduce risks by giving people connections with their neighbors, mutual responsibility for one another, and control over their own fates.

Additionally, distributing security responsibilities formally recognizes one of the realities of network security—most security actions take place on individual systems. The managers of these systems must know that they are responsible for security and that their contribution to network security is recognized and appreciated. If people are expected to do a job, they must be empowered to do it.

Subnets are a possible tool for distributing network control. A subnet administrator should be appointed when a subnet is created. The administrator is then responsible for the security of the network and for assigning IP addresses to the devices connected to the networks. Assigning IP addresses gives the subnet administrator some control over who connects to the subnet. It also helps to ensure that the administrator knows each system that is connected and who is responsible for that system. When the subnet administrator gives a system an IP address, he also delegates certain security responsibilities to the system’s administrator. Likewise, when the system administrator grants a user an account, the user takes on certain security responsibilities.

The hierarchy of responsibility flows from the network administrator to the subnet administrator to the system administrator and finally to the user. At each point in this hierarchy the individuals are given responsibilities and the power to carry them out. To support this structure, it is important for users to know what they are responsible for and how to carry out that responsibility. The network security policy described in the next section provides this information.

If your site adopts distributed control, you must develop a system for disseminating security information to each group. Mailing lists for each administrative level can be used for alerts and other real-time information. An internal web site can be used to provide policy, background, and archival information as well as links to important security sites.

The network administrator receives security information from outside authorities, filters out irrelevant material, and forwards the relevant material to the subnet administrators. Subnet administrators forward the relevant parts to their system administrators, who in turn forward what they consider important to the individual users. The filtering of information at each level ensures that individuals get the information they need without receiving too much. If too much unnecessary material is distributed, users begin to ignore everything they receive.

At the top of this information structure is the information that the network administrator receives from outside authorities. In order to receive this, the network administrator should join the appropriate mailing lists and newsgroups and browse the appropriate web sites. A few places to start looking for computer security information are the following:

- Your Unix vendor

Many vendors have their own security information mailing lists. Most vendors also have a security page on their web sites. Place a link on your internal web site to the vendor information that you find important and useful.

- The Bugtraq archive

Bugtraq reports on software bugs, some of which are exploited by intruders. Knowing about these bugs and the fixes for them is the single most important thing you can do to improve system security. Bugtraq is widely available on the Web. Two sites I use are http://www.geek-girl.com/bugtraq and http://www.securityfocus.com, which provide access to a wide range of security information.

- Security newsgroups

The comp.security newsgroups—comp.security.unix, comp.security.firewalls, comp.security.announce, and comp.security.misc—contain some useful information. Like most newsgroups, they also contain lots of unimportant and uninteresting material. But they do contain an occasional gem.

- FIRST web site

The Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) is a worldwide organization of computer security response teams. FIRST provides a public web site for computer security information.

- NIST Computer Security Alerts

The National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Computer Security Division maintains a web site with pointers to security-related web pages all over the world. Follow the Alerts link from http://csrc.nist.gov.

- CERT advisories

The Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) advisories provide information about known security problems and the fixes to these problems. You can retrieve these advisories from the CERT web site at http://www.cert.org.

- SANS Institute

The System Administration, Networking and Security (SANS)Institute offers informative security newsletters that are delivered weekly via email . They also have a useful online reading room. These resources are available from their web site, http://www.sans.org.

- Exploit sites

Most intruders use canned attack scripts that are available from the Web. Sites that provide the scripts often provide discussions of the current security vulnerabilities that might affect your system. http://www.insecure.org is a good site because it provides descriptions of current exploits as well as plenty of other useful information.

Security is largely a “people problem.” People, not computers, are responsible for implementing security procedures, and people are responsible when security is breached. Therefore, network security is ineffective unless people know their responsibilities. It is important to write a security policy that clearly states what is expected and from whom. A network security policy should define:

- The network user’s security responsibilities

The policy may require users to change their passwords at certain intervals, to use passwords that meet certain guidelines, or to perform certain checks to see if their accounts have been accessed by someone else. Whatever is expected from users, it is important that it be clearly defined.

- The system administrator’s security responsibilities

The policy may require that every host use specific security measures, login banner messages, or monitoring and accounting procedures. It might list applications that should not be run on any host attached to the network.

- The proper use of network resources

Define who can use network resources, what things they can do, and what things they should not do. If your organization takes the position that email, files, and histories of computer activity are subject to security monitoring, tell the users very clearly that this is the policy.

- The actions taken when a security problem is detected

What should be done when a security problem is detected? Who should be notified? It is easy to overlook things during a crisis, so you should have a detailed list of the exact steps that a system administrator or user should take when a security breach is detected. This could be as simple as telling the users to “touch nothing, and call the network security officer.” But even these simple actions should be in the written policy so that they are readily available.

Connecting to the Internet brings with it certain security responsibilities. RFC 1281, A Guideline for the Secure Operation of the Internet, provides guidance for users and network administrators on how to use the Internet in a secure and responsible manner. Reading this RFC will provide insight into the information that should be in your security policy.

A great deal of thought is necessary to produce a complete network security policy. The outline shown above describes the contents of a network policy document, but if you are personally responsible for writing a policy, you may want more detailed guidance. I recommend that you read RFC 2196, which is a very good guide for developing a security plan.

Security planning (assessing the threat, assigning security responsibilities, and writing a security policy) is the basic building block of network security, but the plan must be implemented before it can have any effect. In the remainder of this chapter, we’ll turn our attention to implementing basic security procedures.

Good passwords are one of the simplest parts of good network security. Passwords are used to log into systems that use password authentication. Popular mythology says that all network security breaches are caused by sophisticated crackers who discover software security holes. In reality, some of the most famous intruders entered systems simply by guessing or stealing passwords or by exploiting well-known security problems in outdated software. Later in this chapter, we look at guidelines for keeping software up to date and ways to prevent a thief from stealing your password. First, let’s see what we can do to prevent it from being guessed.

These are a few things that make it easy to guess passwords:

Accounts that use the account name as the password. Accounts with this type of trivial password are called joe accounts.

Guest or demonstration accounts that require no password or use a well-publicized password.

System accounts with default passwords.

User who tell their passwords to others.

Guessing these kinds of passwords requires no skill, just lots of spare time! Changing your password frequently is a deterrent to password guessing. However, if you choose good passwords, don’t change them so often that it is hard to remember them. Many security experts recommend that passwords should be changed about every 3 to 6 months.

A more sophisticated form of password guessing is dictionary guessing. Dictionary guessing uses a program that encrypts each word in a dictionary (e.g., /usr/dict/words) and compares each encrypted word to the encrypted password in the /etc/passwd file. Dictionary guessing is not limited to words from a dictionary. Things known about you (your name, initials, telephone number, etc.) are also run through the guessing program. Because of dictionary guessing, you must protect the /etc/passwd file.

Some systems provide a shadow password file to hide the encrypted passwords from potential intruders. If your system has a shadow password facility, use it. Hiding encrypted passwords greatly reduces the risk of password guessing.

Shadow password files have restricted permissions that prevent them from being read by intruders. The encrypted password is stored only in the shadow password file, /etc/shadow, and not in the /etc/passwd file. The passwd file is maintained as a world-readable file because it contains information that various programs use. The shadow file can be read only by root and it does not duplicate the information in the passwd file. It contains only passwords and the information needed to manage them. The format of a shadow file entry on a Solaris system is:

username:password:lastchg:min:max:warn:inactive:expire:flagusername is the login username.

password is the encrypted password or, on

Solaris systems, one of the keyword values NP or *LK*. lastchg is

the date that the password was last changed, written as the number of

days from January 1, 1970 to the date of the change.

min is the minimum number of days that must

elapse before the password can be changed.

max is the maximum number of days the user

can keep the password before it must be changed.

warn is the number of days before the

password expires that the user is warned.

inactive is the number of days the account

can be inactive before it is locked. expire

is the date on which the account will be closed.

flag is unused.

The encrypted password appears only in this file. Every password

field in the /etc/passwd file contains an

x, which tells the system to look

in the shadow file for the real password. Every

password field in the /etc/shadow file contains

either an encrypted password, NP,

or *LK*. If it contains the keyword

NP, it means that there is no

password because this is not a login account. System accounts, such as

daemon or uucp, are not

login accounts, so they have NP in

the password field. *LK* in the

password field means that this account has been locked and is

therefore disabled from any further use. Other systems use different

symbols in the password field to indicate these conditions; some Linux

systems use * and !!. However, all systems have some technique

for differentiating active login accounts from other types of user

IDs.

While the most important purpose of the shadow file is to protect the password, the additional fields in the shadow entry provide other useful security services. One of these is password aging. A password aging mechanism defines a lifetime for each password. When a password reaches the end of its lifetime, the password aging mechanism notifies the user to change the password. If it is not changed within some specified period, the password is removed from the system and the user is blocked from using his account.

The lastchg, max, and warn fields all play a role in password aging. They allow the system to know when the password was changed and how long it should be kept, as well as when the user should be warned about his impending doom. Another nice feature of the shadow file is the min field. This is a more subtle aspect of password aging. It prevents the user from changing her favorite password to a dummy password and then immediately back to the favorite. When the password is changed it must be used for the number of days defined by min before it can be changed again. This reduces one of the common tricks used to avoid really changing passwords.

The inactive and expire fields help eliminate unused accounts. Here, “inactivity” is determined by the number of days the account continues with an expired password. Once the password expires, the user is given some number of days to log in and set a new password. If the user does not log in before the specified number of days has elapsed, the account is locked and the user cannot log in.

The expire field lets you create a user account that has a specified “life.” When the date stored in the expire field is reached, the user account is disabled even if it is still active. The expiration date is stored as the number of days since January 1, 1970.

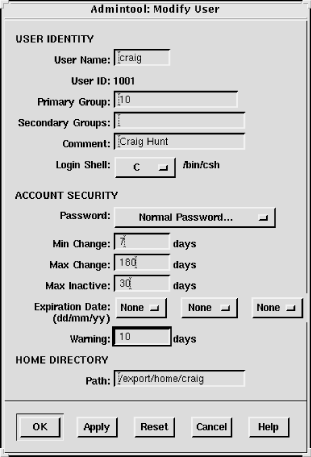

On a Solaris system the /etc/shadow file is

not edited directly. It is modified through the Users window of the

admintool or special options on the

passwd command line. This window is

shown in Figure 12-1. The

username, password, min, max, warn, inactive, and expire fields are

clearly shown.

The passwd command on Solaris systems has -n min, -w warn, and

-x max

options to set the min, max, and warn fields in the

/etc/shadow file. Only the root user can invoke

these options. Here, root sets the maximum life of Tyler’s password to

180 days:

# passwd -x 180 tylerThe Solaris system permits the system administrator to set

default values for all of these options so that they do not have to be

set every time a user is added through the admintool or the passwd command line. The default values are

set in the /etc/default/passwd file.

% cat /etc/default/passwd

#ident "@(#)passwd.dfl 1.3 92/07/14 SMI"

MAXWEEKS=

MINWEEKS=

PASSLENGTH=6The default values that can be set in the /etc/default/passwd file are:

-

MAXWEEKS The maximum life of a password defined in weeks, not days. The 180-day period used in the example above would be defined with this parameter as

MAXWEEKS=26.-

MINWEEKS The minimum number of weeks a password must be used before it can be changed.

-

PASSLENGTH The minimum number of characters that a password must contain. This is set to 6 in the sample file. Only the first eight characters are significant on a Solaris system; setting the value above 8 does not change that fact.

-

WARNWEEKS The number of weeks before a password expires that the user is warned.

This section uses Solaris as an example. The shadow password system is provided as part of the Solaris operating system. It is also included with Linux systems. The shadow file described here is exactly the same format as used on Linux systems, and it functions in the same way.

It is very difficult to take the encrypted password and decrypt it back to its original form, but encrypted passwords can be compared against encrypted dictionaries. If bad passwords are used, they can be easily guessed. Take care to protect the /etc/passwd file and choose good passwords.

A good password is an essential part of security. We usually think of the password used for a traditional login; however, passwords, passphrases, and keys are also needed for more advanced authentication systems. For all of these purposes, you want to choose a good password. Choosing a good password boils down to not choosing a password that can be guessed using the techniques described above. Some guidelines for choosing a good password are:

Don’t use your login name.

Don’t use the name of anyone or anything.

Don’t use any English or foreign-language word or abbreviation.

Don’t use any personal information associated with the owner of the account. For example, don’t use your initials, phone number, social security number, job title, organizational unit, etc.

Don’t use keyboard sequences, e.g., qwerty.

Don’t use any of the above spelled backwards, or in caps, or otherwise disguised.

Don’t use an all-numeric password.

Don’t use a sample password, no matter how good, that you’ve gotten from a book that discusses computer security.

Do use a mixture of numbers, special characters, and mixed-case letters.

Do use at least six characters.

Do use a seemingly random selection of letters and numbers.

Common suggestions for constructing seemingly random passwords are:

Use the first letter of each word from a line in a book, song, or poem. For example, “People don’t know you and trust is a joke.”[128] would produce Pd’ky&tiaj.

Use the output from a random password generator. Select a random string that can be pronounced and is easy to remember. For example, the random string “adazac” can be pronounced a-da-zac, and you can remember it by thinking of it as “A-to-Z.” Add uppercase letters to create your own emphasis, e.g., aDAzac.[129]

Use two short words connected by punctuation, e.g., wRen%Rug.

Use numbers and letters to create an imaginary vanity license plate password, e.g., 2hot4U?.

A common theme of these suggestions is that the password should be easy to remember. Avoid passwords that must be written down to be remembered. If unreliable people gain access to your office and find the password you have written down, the security of your system will be compromised.

However, don’t assume that you can’t remember a random password. It may be difficult the first few times you use the password, but any password that is used often enough is easy to remember. If you have an account on a system that you rarely use, you may have trouble remembering a random password. But in that case, the best solution is to get rid of the account. Unused and underutilized accounts are prime targets for intruders. They like to attack unused accounts because there is no user to notice changes to the files or strange Last login: messages. Remove all unused accounts from your systems.

How do you ensure that the guidance for creating new passwords is followed? The most important step is to make sure that every user knows these suggestions and the importance of following them. Cover this topic in your network security plan, and periodically reinforce it through newsletter articles and online system bulletins.

It is also possible to use programs that force users to follow specific password selection guidelines. The web page http://csrc.nist.gov/tools/tools.htm lists several programs that do exactly that.

Sometimes good passwords are not enough. Passwords are transmitted across the network as clear text. Intruders can use protocol-analyzer software to spy on network traffic and steal passwords. If a thief steals your password, it does not matter how good the password was.

The thief can be on any network that handles your TCP/IP packets. If you log in through your local network, you have to worry only about local snoops. But if you log in over the Internet, you must worry about unseen listeners from any number of unknown networks.

Commands that use encrypted passwords are not vulnerable to this

type of attack. Because of this, telnet has been largely supplanted by secure

shell (ssh). However, the secure

shell client may not be available at a remote site. Use one-time

passwords for remote logins when you cannot use secure shell. Because

a one-time password can be used only once, a thief who steals the

password cannot use it.

Naturally, one-time password systems are a hassle. You must

carry with you a list of one-time passwords, or something that can

generate them, any time you want to log in. If you forget the password

list, you cannot log in. However, this may not be as big a problem as

it seems. You usually log in from your office where your primary login

host is probably on your desktop or your local area network. When you

log into your desktop system from its keyboard, the password does not

traverse the network, so you can use a reusable password. And ssh can be used any time you control both

ends of the connection, for example, when logging in with your laptop.

One-time passwords are needed only for the occasions when you log in

from a remote location that does not offer ssh. For this reason, some one-time password

systems are designed to allow reusable passwords when they are

appropriate.

There are several one-time password systems. Some use specialized hardware such as “smart cards.” OPIE is a free software system that requires no special hardware.

One-time Passwords In Everything (OPIE) is free software from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) that modifies a Unix system to use one-time passwords. OPIE is directly derived from Skey, which is a one-time password system created by Bell Communications Research (Bellcore).

Download OPIE from the Internet from http://inner.net/opie. The current

version of OPIE is opie-2.4.tar.gz. It is a

binary file. gunzip the file and

extract it using tar. The directory

this produces contains the source files, Makefiles, and scripts

necessary to compile and install OPIE.

OPIE comes with configure, an

auto-configuration script that detects your system’s configuration and

modifies the Makefile accordingly. It does a good job, but you still

should manually edit the Makefile to make sure it is correct. For

example, my Linux system uses the Washington University FTP daemon

wu.ftpd. OPIE replaces login, su, and ftpd with its own version of these programs.

Using an earlier version of OPIE on my Linux system, configure did not find ftpd, and I did not notice the problem when

I checked the Makefile. make ran

without errors, but make install failed during the install of the

OPIE FTP daemon. The Makefile was easily corrected and the rerun of

make install was successful.

The effects of OPIE are evident as soon as the install

completes. Run su and you’re

prompted with root's response:

instead of Password:. login prompts with Response or Password: instead of just Password:. The response requested by these programs is the

OPIE equivalent of a password. Programs that prompt with Response or Password accept either the OPIE response or

the traditional password from the /etc/passwd

file. This feature permits users to migrate gracefully from

traditional passwords to OPIE. It also allows local console logins

with reusable passwords while permitting remote logins with one-time

passwords. The best of both worlds—convenient local logins without

creating separate local and remote login accounts!

To use OPIE you must first select a secret password that is used

to generate the one-time password list, and then run the program that

generates the list. To select a secret password, run opiepasswd as shown:

$ opiepasswd -c Updating kristin: Reminder - Only use this method from the console; NEVER from remote. If you are using telnet, xterm, or a dial-in, type ^C now or exit with no password. Then run opiepasswd without the -c parameter. Using MD5 to compute responses. Enter old secret pass phrase: 3J5Wd6PaWP Enter new secret pass phrase: 9WA11WSfW95/NT Again new secret pass phrase: 9WA11WSfW95/NT

This example shows the user kristin

updating her secret password. She runs opiepasswd from the computer’s console, as

indicated by the -c command option.

Running opiepasswd from the console

is the most secure. If it is not run from the console, you must have a

copy of the opiekey software with

you to generate the correct responses needed to enter your old and new

secret passwords, because clear text passwords are accepted only from

the console. Kristin is prompted to enter her old password and to

select a new one. OPIE passwords must be at least 10 characters long.

Since the new password is long enough, opiepasswd accepts it and displays the

following two lines:

ID kristin OPIE key is 499 be93564 CITE JAN GORY BELA GET ABED

These lines tell Kristin the information she needs to generate

OPIE login responses and the first response she will need to log into

the system. The one-time password needed for Kristin’s next login

response is the second line of this display: a group of six short,

uppercase character strings. The first line of the display contains

the initial sequence number (499) and the seed (be93564) she needs,

along with her secret password, to generate OPIE login responses. The

software used to generate those responses is opiekey.

opiekey takes the login

sequence number, the user’s seed, and the user’s secret password as

input and outputs the correct one-time password. If you have opiekey software on the system from which

you are initiating the login, you can produce one-time passwords one

at a time. If, however, you will not have access to opiekey when you are away from your login

host, you can use the -n option to

request several passwords. Write the passwords down, put them in your

wallet, and you’re ready to go! [130]

In the following example we request five (-n 5) responses from opiekey:

$ opiekey -n 5 495 wi01309 Using MD5 algorithm to compute response. Reminder: Don't use opiekey from telnet or dial-in sessions. Enter secret pass phrase: UUaX26CPaU 491: HOST VET FOWL SEEK IOWA YAP 492: JOB ARTS WERE FEAT TILE IBIS 493: TRUE BRED JOEL USER HALT EBEN 494: HOOD WED MOLT PAN FED RUBY 495: SUB YAW BILE GLEE OWE NOR

First opiekey tells us that

it is using the MD5 algorithm to produce the responses, which is the

default for OPIE. For compatibility with older Skey or OPIE

implementations, force opiekey to

use the MD4 algorithm by using the -4 command-line option. opiekey prompts for your secret password.

This is the password you defined with the opiepasswd command. It then prints out the

number of responses requested and lists them in sequence number order.

The login sequence numbers in the example are 495 to 491. When the

sequence number gets down to 10, rerun opiepasswd and select a new secret password.

Selecting a new secret password resets the sequence number to

499.

The OPIE login prompt displays a sequence number, and you must provide the response that goes with that sequence number. For example:

login: tyler otp-md5 492 wi01309 Response or Password: JOB ARTS WERE FEAT TILE IBIS

At the login: prompt, Tyler

enters her username. The system then displays a single line that tells

her that one-time passwords are being generated with the MD5 algorithm

(otp-md5), that this is login sequence number 492, and that the seed

used for her one-time passwords is wi01309. She looks up the response

for login number 492 and enters the six short strings. She then marks

that response off her list because it cannot be used again to log into

the system. A response from the list must be used any time she is not

sitting at the console of her system. Reusable passwords can be used

only at the console.

Secure shell is used for remote logins whenever it is available

on the client. Because of this, one-time passwords are needed only in

special cases. Generally, it is sufficient to have one small OPIE

server on your network. Remote users who are forced to use one-time

passwords log into that server and then use a preferred mechanism,

such as ssh, to log into your real

servers.

Some applications use their own security mechanisms. Make

sure that the security for these applications is configured properly.

In particular, check the Unix r

commands, which are a set of Unix networking applications comparable

to ftp and telnet. Care must be taken to ensure that

the r commands don’t compromise

system security. Improperly configured r commands can open access to your computer

facilities to virtually everyone in the world. For this reason, use of

the r commands is

discouraged.

In place of password authentication, the r commands use a security system based on

trusted hosts and users. Trusted users on trusted hosts are allowed to access the local system

without providing a password. Trusted hosts are also called

"equivalent hosts” because the system assumes that users

given access to a trusted host should be given equivalent access to

the local host. The system assumes that user accounts with the same

name on both hosts are “owned” by the same user. For example, a user

logged in as becky on a trusted system is granted

the same access as the user logged in as becky on

the local system.

This authentication system requires databases that define the trusted hosts and the trusted

users. The databases used to configure the r commands are

/etc/hosts.equiv and .rhosts.

The /etc/hosts.equiv file defines the hosts

and users that are granted “trusted” r command access to your system. This file

can also define hosts and users that are explicitly denied trusted

access. Not having trusted access doesn’t mean that the user is denied

access; it just means that he is required to supply a password.

The basic format of entries in the /etc/hosts.equiv file is:

[+ | -][hostname] [+ | -][username]

The hostname is the name of a

“trusted” host, which may optionally be preceded by a plus sign (+).

The plus sign has no real significance, except when used alone. A plus

sign without a hostname following it is a wildcard character that

means “any host.”

If a host is granted equivalence, users logged into that host

are allowed access to like-named user accounts on your system without

providing a password. (This is one reason for administrators to

observe uniform rules in handing out login names.) The optional

username is the name of a user on the

trusted host who is granted access to all user accounts. If

username is specified, that user is not

limited to like-named accounts, but is given access to all user

accounts without being required to provide a password.[131]

The hostname may also be preceded by

a minus sign (-). This explicitly says that the host is

not an equivalent system. Users from that host

must always supply a password when they use an r command to interact with your system. A

username can also be preceded by a minus

sign. This says that, whatever else may be true about that host, the

user is not trusted and must always supply a password.

The following examples show how entries in the hosts.equiv file are interpreted:

rodentAllows password-free access from any user on rodent to a like-named user account on your local system.

-rodentDenies password-free access from any user on rodent to accounts on your system.

rodent -davidDenies password-free access to the user david if he attempts to access your system from rodent.

rodent +beckyAllows the user becky to access any account (except root) on your system, without supplying a password, if she logs in from rodent.

+ beckyAllows the user becky to access any account (except root) on your system without supplying a password, no matter what host she logs in from.

This last entry is an example of something that should never be used in your configuration. Don’t use a standalone plus sign in place of a hostname. It allows access from any host anywhere and can open up a big security hole. For example, if the entry shown above was in your hosts.equiv file, an intruder could create an account named becky on his system and gain access to every account on your system. Check /etc/hosts.equiv, ~/.rhosts, and /etc/hosts.lpd to make sure that none of them contains a + entry. Remember to check the .rhosts file in every user’s home directory.

A simple typographical error could give you a standalone plus sign. For example, consider the entry:

+ rodent beckyThe system administrator probably meant “give becky password-free access to all accounts when she logs in from rodent.” However, with an extraneous space after the + sign, it means “allow users named rodent and becky password-free access from any host in the world.” Don’t use a plus sign in front of a hostname, and always use care when working with the /etc/hosts.equiv file to avoid security problems.

When configuring the /etc/hosts.equiv file,

grant trusted access only to the systems and users you actually trust.

Don’t grant trusted access to every system attached to your local

network. In fact, it is best not to use the r commands at all. If you must use them,

only trust hosts from your local network when you know the person

responsible for that host, when you know that the host is not

available for public use, and when the local network is protected by a

firewall. Don’t grant trusted access by default—have some reason for

conferring trusted status. Never grant trust to remotely located

systems. It is too easy for an intruder to corrupt routing or DNS in

order to fool your system when you grant trust to a remote system.

Also, never begin your hosts.equiv file with a

minus sign as the first character. This confuses some systems, causing

them to improperly grant access. Always err on the side of caution

when creating a hosts.equiv file. Adding trusted

hosts as they are requested is much easier than recovering from a

malicious intruder.

The .rhosts file grants or denies password-free r command access to a specific user’s

account. It is placed in the user’s home directory and contains

entries that define the trusted hosts and users. Entries in the

.rhosts file use the same format as entries in

the hosts.equiv file and function in almost the

same way. The difference is the scope of access granted by entries in

these two files. In the .rhosts file, the entries

grant or deny access to a single user account; the entries in

hosts.equiv control access to an entire

system.

This functional difference can be shown in a simple example. Assume the following entry:

horseshoe anthony

In crab’s hosts.equiv

file, this entry means that the user anthony on

horseshoe can access any account on

crab without entering a password. In an

.rhosts file in the home directory of user

resnick, the exact same entry allows

anthony to rlogin from horseshoe

as resnick without entering a password, but it

does not grant password-free access to any other accounts on

crab.

Individuals use the .rhosts file to

establish equivalence among the different accounts they own. The entry

shown above would probably be made only if

anthony and resnick are the

same person. For example, I have accounts on several different

systems. Sometimes my username is hunt, and

sometimes it is craig. It would be nice if I had

the same account name everywhere, but that is not always possible; the

names craig and hunt are

used by two other people on my local network. I want to be able to

rlogin to my workstation from any

host that I have an account on, but I don’t want mistaken logins from

the other craig and the other

hunt. The .rhosts file gives

me a way to control this problem.

For example, assume my username on crab is craig, but my username on filbert is hunt. Another user on filbert is craig. To allow myself password-free access to my crab account from filbert, and to make sure that the other user doesn’t have password-free access, I put the following .rhosts file in my home directory:

filbert hunt filbert -craig

Normally the hosts.equiv file is searched

first, followed by the user’s .rhosts file, if it

exists. The first explicit match determines whether or not

password-free access is allowed. Therefore, the

.rhosts file cannot override the

hosts.equiv file. The exception to this is root

user access. When a root user attempts to access a system via the

r commands, the

hosts.equiv file is not checked; only

.rhosts in the root user’s home directory is

consulted. This allows root access to be more tightly controlled. If

the hosts.equiv file were used for root access,

entries that grant trusted access to hosts would give root users on

those hosts root privileges. You can add trusted hosts to

hosts.equiv without granting remote root users

root access to your system.

You should remember that the user can provide access with the

.rhosts file even when the

hosts.equiv file doesn’t exist. The only way to

prevent users from doing this is to periodically check for and remove

the .rhosts files. As long as you have the

r commands on your system, it is

possible for a user to accidentally compromise the security of your

system.

The weak security of the r

commands poses a security threat. You cannot use these commands to

provide secure remote access, even if you use all the techniques given

in the previous section. At best, only trusted local systems on a

secured local network can be given access via the r commands. The reason for this is that the

r commands grant trust based on a

belief that the IP address uniquely identifies the correct computer.

Normally it does. But an intruder can corrupt DNS to provide the wrong

IP address or corrupt routing to deliver to the wrong network, thus

undermining the authentication scheme used by the r commands.

An alternative to the remote shell is the secure shell. Secure shell replaces the standard r commands with secure commands that include

encryption and authentication. Secure shell uses a strong

authentication scheme to ensure that the trusted host really is the

host it claims to be. Secure shell provides a number of public-key

encryption schemes to ensure that every packet in the stream of

packets is from the source it claims to be from. Secure shell is

secure and easy to use.

There are currently two versions of secure shell in widespread use: SSH Secure Shell, which is a commercial product, and OpenSSH, which is an open source product. OpenSSH is included with various versions of Unix and Linux, and both the open source and the commercial secure shell products are available for download from the Internet if your system does not include secure shell. The examples used in this section are based on OpenSSH, but the basic functions of both versions of secure shell are essentially the same.

The basic components of secure shell are:

-

sshd The secure shell daemon handles incoming SSH connections.

sshdshould be started at boot time from one of the boot scripts; don’t start it from inetd.conf.sshdgenerates an encryption key every time it starts. This can cause it to be slow to start, which makes it unsuitable for inetd.conf. A system serving SSH connections must runsshd.sshThe secure shell user command. The

sshcommand replacesrshandrlogin. It is used to securely pass a command to a remote system or to securely log into a remote system. This command creates the outgoing connections that are handled by the remote secure shell daemon. A client system that wants to use an SSH connection must have thesshcommand.-

scp Secure copy (

scp) is the secure shell version ofrcp.-

ssh-keygen Generates the public and private encryption keys used to secure the transmission for the secure shell.

-

sftp A version of FTP that operates over a secure shell connection.

When an ssh client connects to an sshd server, they exchange public keys. The systems compare the keys they receive to the known keys they have stored in the /etc/ssh_known_hosts file and in the .ssh/known_hosts file in the user’s home directory.[132]

If the key is not found or has changed, the user is asked to verify that the new key should be accepted:

> ssh horseshoe

Host key not found from the list of known hosts.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)? yes

Host 'horseshoe' added to the list of known hosts.

craig's password: Watts.Watt.

Last login: Thu Sep 25 15:01:32 1997 from rodent

Linux 2.0.0.

/usr/X11/bin/xauth: creating new authority file /home/craig/.XauthorityIf the key is found in one of the files or is accepted by the user, the client uses it to encrypt a randomly generated session key. The session key is then sent to the server, and both systems use the key to encrypt the remainder of the SSH session.

The client is authenticated if it is listed in the hosts.equiv file, the

shost.equiv file, the user’s

.rhosts file, or the .shosts

file. This type of authentication is similar to the type used by the

r commands, and the format of the

shost.equiv and the .shosts

files is the same as their r

command equivalents. Notice that in the sample above, the user is

prompted for a password. If the client is not listed in one of the

files, password authentication is used. As you can see, the password

appears in plain text. However, there is no need to worry about

password thieves because SSH encrypts the password before it is sent

across the link.

Users can employ a public-key challenge/response protocol for authentication. First generate your public and private encryption keys:

> ssh-keygen

Initializing random number generator...

Generating p: ......................................++ (distance 616)

Generating q: ....................++ (distance 244)

Computing the keys...

Testing the keys...

Key generation complete.

Enter file in which to save the key (/home/craig/.ssh/identity):

Enter passphrase: Pdky&tiaj.

Enter the same passphrase again: Pdky&tiaj.

Your identification has been saved in /home/craig/.ssh/identity.

Your public key is:

1024 35 158564823484025855320901702005057103023948197170850159592181522

craig@horseshoe

Your public key has been saved in /home/craig/.ssh/identity.pubThe ssh-keygen command

creates your keys. Enter a password (or “passphrase”) of at least 10

characters. Use the rules described earlier for picking a good

password to choose a good passphrase that is easy to remember. If you

forget the passphrase, no one will be able to recover it for

you.

Once you have created your keys on the client system, copy the

public key to your account on the server. The public key is stored in

your home directory on the client in

.ssh/identity.pub. Copy it to

.ssh/authorized_keys in your home directory on

the server. Now when you log in using ssh, you are prompted for the

passphrase:

> ssh horseshoe

Enter passphrase for RSA key 'craig@horseshoe': Pdky&tiaj.

Last login: Thu Sep 25 17:11:51 2001To improve system security, the r commands should be disabled after SSH is installed.

Comment rshd, rlogind, rexcd, and rexd out of the

inetd.conf file to disable inbound connections to

the r commands. To ensure that SSH

is used for outbound connections, replace rlogin and rsh with ssh. To do this, store copies of the

original rlogin and rsh in a safe place, rerun configure with the special options shown

here, and run make install:

# whereis rlogin /usr/bin/rlogin # whereis rsh /usr/bin/rsh # cp /usr/bin/rlogin /usr/lib/rlogin # cp /usr/bin/rsh /usr/lib/rsh # ./configure -- with-rsh=/usr/bin -- program-transform-name='s/ s/r/' # make install

The example assumes that the path to the original rlogin and rsh commands is

/usr/bin. Use whatever is correct for your

system.

After replacing rlogin and

rsh, you can still log into systems

that don’t support SSH. You will, however, be warned that it is not a

secure connection:

> rlogin cow

Secure connection to cow refused; reverting to insecure method.

Using rsh. WARNING: Connection will not be encrypted.

Last login: Wed Sep 24 22:15:28 from rodentSSH is an excellent way to have secure communications between systems across the Internet. However, it does require that both systems have SSH installed. When you control both ends of the link, this is not a problem. But there are times when you must log in from a system that is not under your control. For those occasions, one-time passwords, such as those provided by OPIE, are still essential.

Having authentication is an important security measure. However, it isn’t the only thing you can do to improve the security of your computer and your network. Most break-ins occur when bugs in applications are exploited or when applications are misconfigured. In this section we’ll look at some things you can do to improve application security.

Any software that allows an incoming connection from a remote site

has the potential of being exploited by an intruder. Some security

experts recommend you remove every daemon from the

/etc/inetd.conf file that you don’t absolutely

need. (Configuring the inetd.conf file and the

/etc/xinetd.conf file is discussed in Chapter 5, with explicit examples of

removing tftp from service.)

Server systems may require several daemons, but most desktop

systems require very few, if any. Removing the daemons from

inetd.conf prevents only inbound connections. It

does not prevent out-bound connections. A user can still initiate a

telnet to a remote site even after

the telnet daemon is removed from

her system’s inetd.conf. A simple approach used

by some people is to remove everything from

inetd.conf and then add back to the file only

those daemons that you decide you really need.

Vendors frequently release new versions of network software for the express purpose of improving network security. Use the latest version of the network software offered by your vendor. Track the security alerts, CERT advisories, and bulletins to know what programs are particularly important to keep updated.

If you fail to keep the software on your system up to date, you open a big security hole for intruders. Most intruders don’t discover new problems—they exploit well-known problems. Keep track of the known security problems so you can keep your system up to date.

Stay informed about all the latest fixes for your system. The computer security advisories are a good way to do this. Contact your vendor and find out what services they provide for distributing security fixes. Make sure that the vendor knows that security is important to you.

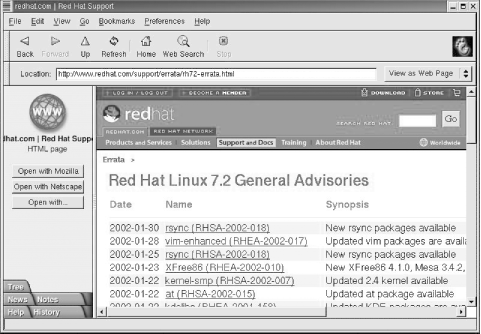

Figure 12-2 shows a software update list at the Red Hat web site. Clicking on any of the updates listed here provides a detailed description of the problem as well as a link to the fix for that problem.

Vendor resources such as the one shown in Figure 12-2 are essential for keeping software up to date. However, you must use these resources for them to be effective. Frequently, administrators complain that vendors do not fix problems, and of course sometimes that is true. But a far more common problem is that system administrators do not install the fixes that are available. Set aside some time every month to apply the latest updates.

Software update services, such as the Red Hat Network, have the potential of lessening the burden of keeping software up to date. With a software update service, the vendor is responsible for periodically updating the system software via the network. Whether or not these services will be a success remains to be seen. They have the potential to improve security and reduce the administrative burden, but many administrators fear the loss of control that comes with giving update privileges to an outside organization.

A key element of effective network security is security monitoring. Good security is an ongoing process, and following the security guidelines discussed above is just the beginning. You must also monitor the systems to detect unauthorized user activity and to locate and close security holes. Over time, a system will change—active accounts become inactive and file permissions are changed. You need to detect and fix these problems as they arise.

Network security is monitored by examining the files and logs of individual

systems on the network. To detect unusual activity on a system, you

must know what activity is normal. What processes are normally

running? Who is usually logged in? Who commonly logs in after hours?

You need to know this, and more, about your system in order to develop

a “feel” for how things should be. Some common Unix commands—ps and who—can help you learn what normal activity

is for your system.

The ps command displays the

status of currently running processes. Run ps regularly to gain a clear picture of what

processes run on the system at different times of the day and who runs

them. The Linux ps -au command and

the Solaris ps -ef command display

the user and the command that initiated each process. This should be

sufficient information to learn who runs what and when they run it. If

you notice something unusual, investigate it. Make sure you understand

how your system is being used.

The who command provides information about who is currently

logged into your system. It displays who is logged in, what device

they are using, when they logged in and, if applicable, what remote

host they logged in from. (The w

command, a variation of who

available on some systems, also displays the currently active process

started by each user.) The who

command helps you learn who is usually logged in as well as what

remote hosts they normally log in from. Investigate any variations

from the norm.

If any of these routine checks gives you reason to suspect a security problem, examine the system for unusual or modified files, for files that you know should be there but aren’t, and for unusual login activity. This close examination of the system can also be made using everyday Unix commands. Not every command or file we discuss will be available on every system. But every system will have some tools that help you keep a close eye on how your system is being used.

Intruders often leave behind files or shell scripts to help them

re-enter the system or gain root access. Use the ls -a | grep '^\'. command to check for

files with names that begin with a dot (.).

Intruders particularly favor names such as .mail,

.xx, ... (dot, dot, dot), ..

(dot, dot, space), or ..^G (dot, dot,

Ctl-G).

If any files with names like these are found, suspect a

break-in. (Remember that one directory named . and one directory named .. are in every directory except the root

directory.) Examine the contents of any suspicious files and follow

your normal incident-reporting procedures.

You should also examine certain key files if you suspect a security problem:

- /etc/inetd.conf and /etc/xinetd.conf

Check the names of the programs started from the /etc/inetd.conf file or the /etc/xinetd.conf file if your system uses

xinetd. In particular, make sure that it does not start any shell programs (e.g., /bin/csh). Also check the programs that are started byinetdor byxinetdto make sure the programs have not been modified. /etc/inetd.conf and /etc/xinetd.conf should not be world-writable.- r command security files

Check /etc/hosts.equiv , /etc/hosts.lpd , and the .rhosts file in each user’s home directory to make sure they have not been improperly modified. In particular, look for any plus sign (+) entries and any entries for hosts outside of your local trusted network. These files should not be world-writable. Better yet, remove the

rcommands from your system and make sure no one reinstalls them.- /etc/passwd

Make sure that the /etc/passwd file has not been modified. Look for new usernames and changes to the UID or GID of any account. /etc/passwd should not be world-writable.

- Files run by

cronorat Check all of the files run by

cronorat, looking for new files or unexplained changes. Sometimes intruders use procedures run bycronoratto readmit themselves to the system, even after they have been kicked off.- Executable files

Check all executable files, binaries, and shell files to make sure they have not been modified by the intruder. Executable files should not be world-writable.

If you find or even suspect a problem, follow your reporting procedure and let people know about the problem. This is particularly important if you are connected to a local area network. A problem on your system could spread to other systems on the network.

The find command is a

powerful tool for detecting potential filesystem

security problems because it can search the entire filesystem for

files based on file permissions. Intruders often leave behind setuid

programs to grant themselves root access. The following command

searches for these files recursively, starting from the root

directory:

# find / -user root -perm -4000 -printThis find command starts

searching at the root (/) for files owned by the user root (-user root) that have the setuid permission bit

set (-perm -4000). All matches

found are displayed at the terminal (-print). If any filenames are displayed by

find, closely examine the

individual files to make sure that these permissions are correct. As

a general rule, shell scripts should not have setuid

permission.

You can use the find

command to check for other problems that might open security holes

for intruders. The other common problems that find checks for are world-writable files

(-perm -2), setgid files (-perm -2000), and unowned files (-nouser -o -nogroup). World-writable and setgid files

should be checked to make sure that these permissions are

appropriate. As a general rule, files with names beginning with a

dot (.) should not be world-writable, and setgid permission, like

setuid, should be avoided for shell scripts.

The process of scanning the filesystem can be automated with the Tripwire program. A commercially supported version of Tripwire is available from http://www.tripwiresecurity.com, and an open source version for Linux is available from http://www.tripwire.org. This package not only scans the filesystem for problems, it computes digital signatures to ensure that if any files are changed, the changes will be detected.

Strange login activity (at odd times of the day or from

unfamiliar locations) can indicate attempts by intruders to gain

access to your system. We have already used the who command to check who is currently

logged into the system. To check who has logged into the system in

the past, use the last

command.

The last command displays the contents of the

wtmp file.[133] It is useful for learning normal login patterns and

detecting abnormal login activity. The wtmp

file keeps a historical record of who logged into the system, when

they logged in, what remote site they logged in from, and when they

logged out.

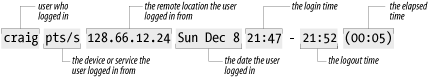

Figure 12-3 shows a

single line of last command

output. The figure highlights the fields that show the user who

logged in, the device, the remote location from which the login

originated (if applicable), the day, the date, the time logged in,

the time logged out (if applicable), and the elapsed time.

Simply typing last produces

a large amount of output because every login stored in

wtmp is displayed. To limit the output, specify

a username or tty device on the command line. This limits the

display to entries for the specified username or terminal. It is

also useful to use grep to search

last’s output for certain

conditions. For example, the command below checks for logins that

occur on Saturday or Sunday:

% last | grep 'S[au]' | more

craig console :0 Sun Dec 15 10:33 still logged in

reboot system boot Sat Dec 14 18:12

root console Sat Dec 14 18:14

craig pts/5 jerboas Sat Dec 14 17:11 - 17:43 (00:32)

craig pts/2 172.16.12.24 Sun Dec 8 21:47 - 21:52 (00:05)

.

.

--More--The next example searches for root logins not originating from the console. If you don’t know who made the two logins reported in this example, be suspicious:

% last root | grep -v console

root pts/5 rodent.wrotethebook.com Tue Oct 29 13:12 - down (00:03)

root ftp crab.wrotethebook.com Tue Sep 10 16:37 - 16:38 (00:00)The last command is a major

source of information about previous login activity. User logins at

odd times or from odd places are suspicious. Remote root logins

should always be discouraged. Use last to check for these problems.

Report any security problems that you detect, or even suspect. Don’t be embarrassed to report a problem because it might turn out to be a false alarm. Don’t keep quiet because you might get “blamed” for the security breach. Your silence will only help the intruder.

Manually monitoring your system is time consuming and prone to errors and omissions. Fortunately, several automated monitoring tools are available. At this writing, the web site http://www.insecure.com lists the monitoring tools that are currently most popular. Tripwire (mentioned earlier) is one of them. Some other currently popular tools are:

- Nessus

Nessus is a network-based security scanner that uses a client/server architecture. Nessus scans target systems for a wide range of known security problems.

- SATAN

Security Auditing Tool for Analyzing Networks is the first network-based security scanner that became widely distributed. Somewhat outdated, it is still popular and can detect a wide range of known security problems. SATAN has spawned some children, SAINT and SARA, that are also popular.

- SAINT

System Administrator’s Integrated Network Tool scans systems for a wide range of known security problems. SAINT is based on SATAN.

- SARA

Security Auditor’s Research Assistant is the third-generation security scanner based on SATAN and SAINT. SARA detects a wide range of known security problems.

- Whisker

Whisker is a security scanner that is particularly effective at detecting certain CGI script problems that threaten web site security.

- ISS

Internet Security Scanner is a commercial security scanner for those who prefer a commercial product.

- Cybercop

Cybercop is another commercial security scanner for those who prefer commercial products.

- Snort

Snort provides a rule-based system for logging packets. Snort attempts to detect intrusions and report them to the administrator in real time.

- PortSentry

PortSentry detects port scans and can, in real time, block the system initiating the scan. Port scans often precede a full-blown security attack.

The biggest problem with security scanners and intrusion detection tools is that they rapidly become outdated. New attacks emerge that the tools are not equipped to detect. For this reason, this book does not spend time describing the details of any specific scanner. These are the currently popular scanners. By the time you read this, new security tools or new versions of these tools may have taken their place. Use this list as a starting point to search the Web for the latest security tools.

Well-informed users and administrators, good password security, and good system monitoring are the foundation of network security. But more is needed. That “more” is some technique for controlling access to the systems connected to the network, or for controlling access to the data the network carries. In the remainder of this chapter, we look at various security techniques that control access.

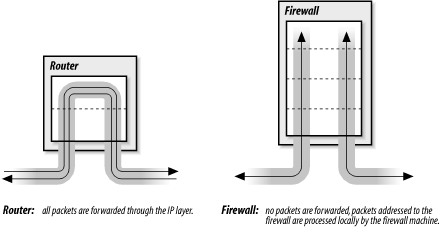

Access control is a technique for limiting access. Routers and hosts that use access control check the address of a host requesting a service against an access control list. If the list says that the remote host is permitted to use the requested service, the access is granted. If the list says that the remote host is not permitted to access the service, access is denied. Access control does not bypass any normal security checks. It adds a check to validate the source of a service request and retains all of the normal checks to validate the user.

Access control systems are common in terminal servers and routers.

For example, Cisco routers have an access control facility. Access

control software is also available for Unix hosts. Two such packages are

xinetd and the TCP wrapper program.

First we examine TCP wrapper (tcpd),

which gets its name from the fact that you wrap it around a network

service so that the service can be reached only by going through the

wrapper.

The wrapper package performs two basic functions: it logs requests for Internet services, and provides an access control mechanism for Unix systems. Logging requests for specific network services is a useful monitoring function, especially if you are looking for possible intruders. If this were all it did, wrapper would be a useful package. But the real power of wrapper is its ability to control access to network services.

The wrapper software is included with many versions of Linux and

Unix. The wrapper tar file

containing the C source code and Makefile necessary to build the

wrapper daemon tcpd is also

available from several sites on the Internet.

If your Unix system does not include wrapper, download the

source, make tcpd, and then install

it in the same directory as the other network daemons. Edit

/etc/inetd.conf and replace the path to each

network service daemon that you wish to place under access control

with the path to tcpd. The only

field in the /etc/inetd.conf entry affected by

tcpd is the sixth field, which

contains the path to the network daemon.

For example, the entry for the finger daemon in

/etc/inetd.conf on our Solaris 8 system

is:

finger stream tcp6 nowait nobody /usr/sbin/in.fingerd in.fingerd

The value in the sixth field is

/usr/sbin/in.fingerd. To monitor access to the

finger daemon, replace this value

with /usr/sbin/tcpd, as in the following

entry:

finger stream tcp6 nowait nobody /usr/sbin/tcpd in.fingerd

Now when inetd receives a

request for fingerd, it starts

tcpd instead. tcpd then logs the fingerd request, checks the access control

information, and, if permitted, starts the real finger daemon to handle the request. In this

way, tcpd acts as a gatekeeper for

other functions.

Make a similar change for every service you want to place under

access control. Good candidates for access control are ftpd, tftpd, telnetd, and fingerd. Obviously, tcpd cannot directly control access for

daemons that are not started by inetd, such as sendmail and NFS. However, other tools, such

as portmapper, use the tcpd configuration files to enforce their

own access controls. Thus the wrapper configuration can have a

positive impact on the security of daemons that are not started by

inetd.

Using the wrapper on most Linux systems is even easier. There is

no need to download and install the tcpd software. It comes as an integral part

of the Linux release. You don’t even have to edit the

/etc/inetd.conf file because the sixth field of

the entries in that file already points to the tcpd program, as shown below:

finger stream tcp nowait nobody /usr/sbin/tcpd in.fingerd -w

The information tcpd uses to

control access is in two files,

/etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny . Each file’s function is obvious from its name.

hosts.allow contains the list of hosts that are

allowed to access the network’s services, and

hosts.deny contains the list of hosts that are

denied access. If the files are not found, tcpd permits every host to have access and

simply logs the access request. Therefore, if you only want to

monitor access, don’t create these two files.

If the files are found, tcpd checks the

hosts.allow file first, followed by the

hosts.deny file. It stops as soon as it finds a

match for the host and the service in question. Therefore, access

granted by hosts.allow cannot be overridden by

hosts.deny.

The format of entries in both files is the same:

service-list:host-list[:shell-command]

The service-list is a list of network

services, separated by commas. These are the services to which

access is being granted (hosts.allow) or denied

(hosts.deny). Each service is identified by the

process name used in the seventh field of the

/etc/inetd.conf entry. This is simply the name

that immediately follows the path to tcpd in inetd.conf.

(See Chapter 5 for a description

of the arguments field in the /etc/inetd.conf

entry.)

Again, let’s use finger as

an example. We changed its inetd.conf entry to

read:

finger stream tcp nowait nobody /usr/etc/tcpd in.fingerd

Given this entry, we would use in.fingerd as the service name in a

hosts.allow or hosts.deny

file.

The host-list is a comma-separated list

of hostnames, domain names, Internet addresses, or network numbers.

The systems listed in the host-list are granted access

(hosts.allow) or denied access

(hosts.deny) to the services specified in the

service-list. A hostname or an Internet address matches an

individual host. For example, rodent is a

hostname and 172.16.12.2 is an Internet address. Both match a

particular host. A domain name matches every host within that

domain; e.g., .wrotethebook.com matches

crab.wrotethebook.com,

rodent.wrotethebook.com,

horseshoe.wrotethebook.com, and any other hosts

in the domain. When specified in a tcpd access control list, domain names

always start with a dot (.). A network number matches every IP

address within that network’s address space. For example, 172.16.

matches 172.16.12.1, 172.16.12.2, 172.16.5.1, and any other address

that begins with 172.16. Network addresses in a tcpd access control list always end with a

dot (.).

A completed hosts.allow entry that grants FTP and Telnet access to all hosts in the wrotethebook.com domain is shown below:

ftpd,telnetd : .wrotethebook.com

Two special keywords can be used in

hosts.allow and hosts.deny

entries. The keyword ALL can be used in the service-list to match all

network services, and in the host-list to match all hostnames and

addresses. The second keyword, LOCAL, can be used only in the host-list. It matches

all local hostnames. tcpd

considers a hostname “local” if it contains no embedded dots.

Therefore, the hostname rodent would match on

LOCAL, but the hostname rodent.wrotethebook.com

would not match. The following entry affects all services and all

local hosts:

ALL : LOCAL

A more complete example of how tcpd is used will help you understand

these entries. First, assume that you wish to allow every host in

your local domain (wrotethebook.com) to have

access to all services on your system, but you want to deny access

to every service to all other hosts. Make an entry in

/etc/hosts.allow to permit access to everything

by everyone in the local domain:

ALL : LOCAL, .wrotethebook.com