Users have a love-hate relationship with email: they love to use it, and hate when it doesn’t work. It’s the system administrator’s job to make sure it does work. That is the job we tackle in this chapter.

sendmail is not the only mail transport program; smail and qmail are also popular, but plain sendmail is the most widely used mail transport program. This entire chapter is devoted to sendmail, and an entire book can easily be devoted to the subject.[108] In part, this is because of email’s importance, but it is also because sendmail has a complex configuration.

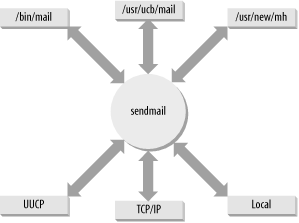

Oddly enough, the complexity of sendmail springs in part from an attempt to reduce complexity by placing all email support in one program. At one time, a wide variety of programs and protocols were used for email. Multiple programs complicate configuration and support. Even today, a few distinct delivery schemes remain. SMTP sends email over TCP/IP networks; another program sends mail between users on the same system; still another sends mail between systems on UUCP networks. Each of these mail systems—SMTP, UUCP, and local mail—has its own delivery program and mail addressing scheme. All of this can cause confusion for mail users and for system administrators.

sendmail eliminates the confusion caused by multiple mail delivery programs. It does this by routing mail for the user to the proper delivery program based on the email address. It accepts mail from a user’s mail program, interprets the mail address, rewrites the address into the proper form for the delivery program, and routes the mail to the correct delivery program. sendmail insulates the end user from these details. If the mail is properly addressed, sendmail will see that it is properly passed on for delivery. Likewise, for incoming mail, sendmail interprets the address and either delivers the mail to a user’s mail program or forwards it to another system.

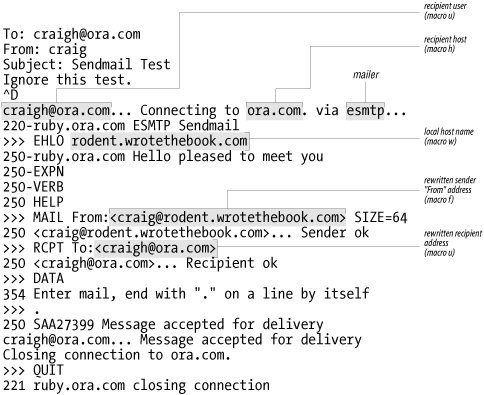

Figure 10-1 illustrates sendmail’s special role in routing mail between the various mail programs found on Unix systems.

In addition to routing mail between user programs and delivery programs, sendmail does the following:

Receives and delivers SMTP (Internet) mail

Provides systemwide mail aliases, which allow mailing lists

Configuring a system to perform all of these functions properly is a complex task. In this chapter we discuss each of these functions, look at how they are configured, and examine ways to simplify the task. First, we’ll see how sendmail is run to receive SMTP mail. Then we’ll see how mail aliases are used, and how sendmail is configured to route mail based on the mail’s address.

To receive SMTP mail from the network, run sendmail as a daemon during system startup. The sendmail daemon listens to TCP port 25 and processes incoming mail. In most cases, the code to start sendmail is already in one of your boot scripts. If it isn’t, add it. The following command starts sendmail as a daemon:

# /usr/lib/sendmail -bd -q15mThis command runs sendmail with two command-line options. The

-q option tells sendmail how often to

process the mail queue. In the sample code, the queue is processed every

15 minutes (-q15m), which is a good

setting to process the queue frequently. Don’t set this time too low. Processing the queue too often can

cause problems if the queue grows very large due to a delivery problem

such as a network outage. For the average desktop system, every hour

(-q1h) or half hour (-q30m) is an adequate setting.

The other option relates directly to receiving SMTP mail. The

-bd option tells sendmail to run as a

daemon and to listen to TCP port 25 for incoming mail. Use this option

if you want your system to accept incoming TCP/IP mail.

The command-line example is a simple one. Most system startup

scripts are more complex. These scripts generally do more than just

start sendmail. Solaris 8 uses the

/etc/init.d/sendmail script to run sendmail. First

the Solaris script checks for the existence of the mail queue directory.

If a mail queue directory doesn’t exist, it creates one. In the Solaris

8 script, the command-line options are set in script variables. The

variable MODE holds the -bd

option, and the variable QUEUEINTERVAL holds the queue processing interval. In the

Solaris 8 script, QUEUEINTERVAL defaults to 15m; change the value stored in the

QUEUEINTERVAL variable to change how often the queue is processed. Do

not change the value in the MODE variable unless you don’t want to

accept inbound mail. The value must be -bd for sendmail to run as a daemon and

collect inbound mail. If you want to add other options to the sendmail

command line that is run by the Solaris 8 script file, store those

options in the OPTIONS variable.

The Red Hat /etc/rc.d/init.d/sendmail

script is even more complex than the Solaris version. It accepts the

arguments start, stop, restart, condrestart, and status so that the script can be used to

effectively manage the sendmail daemon process. The start and stop arguments are self-explanatory. The

restart argument first stops the

sendmail process and then runs a new sendmail process. The condrestart argument is similar to restart except that it runs only if there is a

current sendmail process running. If the sendmail daemon is not running

when the script is run with the condrestart argument, the script does nothing.

The status argument returns the

status of the daemon, which is basically the process ID number if it is

running or a message saying that sendmail is stopped if sendmail is not

running.

When the Red Hat script is run with the start argument, it

begins by rebuilding all of the sendmail database files. It then starts

the sendmail daemon using the command-line options defined in the

/etc/sysconfig/sendmail file. Like the Solaris

script, the Red Hat script uses variables to set the value of the

command-line options, but the variables themselves are set indirectly by

values from /etc/sysconfig/sendmail file. The

/etc/sysconfig/sendmail file from a default Red Hat

configuration contains only two lines:

$ cat /etc/sysconfig/sendmail

DAEMON=yes

QUEUE=1hIf DAEMON is set to yes,

sendmail is run with the -bd option.

How often the queue is processed is determined by the value set for

QUEUE. In this example, the queue is processed every hour (1h). The additional code found in most startup

scripts is helpful, but it is not required to run sendmail as a daemon.

All you really need is the sendmail

command with the -bd option.

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the importance of mail aliases. Without them, a sendmail system could not act as a central mail server. Mail aliases provide for:

Alternate names (nicknames) for individual users

Forwarding of mail to other hosts

Mailing lists

sendmail mail aliases are defined in the aliases file.[109]

The basic format of entries in the aliases file is:

alias:recipient[,recipient,...]

alias is the name to which the mail is

addressed, and recipient is the name to which

the mail is delivered. recipient can be a

username, the name of another alias, or a full email address containing

both a username and a hostname. Including a hostname allows mail to be

forwarded to a remote host. Additionally, there can be multiple

recipients for a single alias. Mail addressed to that alias is delivered

to all of the recipients, thus creating a mailing list.

Aliases that define nicknames for individual users can be used to handle frequently misspelled names. You can also use aliases to deliver mail addressed to special names, such as postmaster or root, to the real users that do those jobs. Aliases can also be used to implement simplified mail addressing, especially when used in conjunction with MX records.[110]

This aliases file from crab shows all of these uses:

# special names

postmaster: clark

root: norman

# accept firstname.lastname@wrotethebook.com

rebecca.hunt: becky@rodent

jessie.mccafferty: jessie@jerboas

anthony.resnick: anthony@horseshoe

andy.wright: andy@ora

# a mailing list

admin: kathy, david@rodent, sara@horseshoe, becky@rodent, craig,

anna@rodent, jane@rodent, christy@ora

owner-admin: admin-request

admin-request: craigThe first two aliases are special names. Using these aliases, mail addressed to postmaster is delivered to the local user clark, and mail addressed to root is delivered to norman.

The second set of aliases is in the form of firstname and lastname. The first alias in this group is rebecca.hunt. Mail addressed to rebecca.hunt is forwarded from crab and delivered to becky@rodent. Combine this alias with an MX record that names crab as the mail server for wrotethebook.com, and mail addressed to rebecca.hunt@wrotethebook.com is delivered to becky@rodent.wrotethebook.com. This type of addressing scheme allows each user to advertise a consistent mailing address that does not change just because the user’s account moves to another host. Additionally, if a remote user knows that this firstname.lastname addressing scheme is used at wrotethebook.com, the remote user can address mail to Rebecca Hunt as rebecca.hunt@wrotethebook.com without knowing her real email address.

The last two aliases are for a mailing list. The alias admin defines the list itself. If mail is sent to admin, a copy of the mail is sent to each of the recipients (kathy, david, sara, becky, craig, anna, jane, and christy). Note that the mailing list continues across multiple lines. A line that starts with a blank or a tab is a continuation line.

The owner-admin alias is a special form used

by sendmail. The format of this special alias is owner- listname where

listname is the name of a mailing list. The person

specified on this alias line is responsible for the list identified by

listname. If sendmail has problems delivering mail

to any of the recipients in the admin list, an

error message is sent to owner-admin. The

owner-admin alias points to

admin-request as the person responsible for

maintaining the mailing list admin. Aliases in the

form of listname -request are commonly used for administrative

requests, such as subscribing to a list, for manually maintained mailing

lists. Notice that we point an alias to another alias, which is

perfectly legal. The admin-request alias resolves

to craig.

sendmail does not use the aliases file

directly. The aliases file must first be processed

by the newaliases command. newaliases is

equivalent to sendmail with the

-bi option, which causes sendmail to

build the aliases database. newaliases creates the database files that are

used by sendmail when it is searching for aliases. Invoke newaliases after updating the

aliases file to make sure that sendmail is able to

use the new aliases.[111]

In addition to the mail forwarding provided by aliases, sendmail allows individual users to define their own forwarding. The user defines personal forwarding in the .forward file in her home directory. sendmail checks for this file after using the aliases file and before making final delivery to the user. If the .forward file exists, sendmail delivers the mail as directed by that file. For example, say that user kathy has a .forward file in her home directory that contains kathy@podunk.edu. The mail that sendmail would normally deliver to the local user kathy is forwarded to kathy’s account at podunk.edu.

Use the .forward file for temporary forwarding. Modifying aliases and rebuilding the database takes more effort than modifying a .forward file, particularly if the forwarding change will be short-lived. Additionally, the .forward file puts users in charge of their own mail forwarding.

Mail aliases and mail forwarding are handled by the aliases file and the .forward file. Everything else about the sendmail configuration is handled in the sendmail.cf file.

The sendmail configuration file is sendmail.cf.[112] It contains most of the sendmail configuration, including the information required to route mail between the user mail programs and the mail delivery programs. The sendmail.cf file has three main functions:

It defines the sendmail environment.

It rewrites addresses into the appropriate syntax for the receiving mailer.

It maps addresses into the instructions necessary to deliver the mail.

Several commands are necessary to perform all of these functions. Macro definitions and option commands define the environment. Rewrite rules rewrite email addresses. Mailer definitions define the instructions necessary to deliver the mail. The terse syntax of these commands makes most system administrators reluctant to read a sendmail.cf file, let alone write one! Fortunately, you can avoid writing your own sendmail.cf file, as we’ll see next.

There is never any good reason to write a sendmail.cf file from scratch. Sample configuration files are delivered with most systems’ software. Some system administrators use the sendmail.cf configuration file that comes with the system and make small modifications to it to handle site-specific configuration requirements. We cover this approach to sendmail configuration later in this chapter.

Most system administrators prefer to use the m4 source files to build a

sendmail.cf file. Building the configuration with

m4 is recommended by the sendmail

developers and is the easiest way to build and maintain a

configuration. Some systems, however, do not ship with the m4 source files, and even when m4 source files come with a system, they are

adequate only if used with the sendmail executable that comes with

that system. If you update sendmail, use the m4 source files that are compatible with the

updated version of sendmail. If you want to use m4 or the latest version of sendmail,

download the sendmail source code distribution from http://www.sendmail.org. See

Appendix E for an example of

installing the sendmail distribution.

The sendmail cf/cf directory contains several sample configuration files. Several of these are generic files preconfigured for different operating systems. The cf/cf directory in the sendmail.8.11.3 directory contains generic configurations for BSD, Solaris, SunOS, HP Unix, Ultrix, OSF1, and Next Step. The directory also contains a few prototype files designed to be easily modified and used for other operating systems. We will modify the tcpproto.mc file, which is for systems that have direct TCP/IP network connections and no direct UUCP connections, to run on our Linux system.

The prototype files that come with the sendmail tar are not “ready to run.” They must be

edited and then processed by the m4 macro processor to produce the actual

configuration files. For example, the

tcpproto.mc file contains the following macros:

divert(0)dnl VERSIONID(`$Id: ch10.xml,v 1.9 2004/09/22 19:24:26 marti Exp $') OSTYPE(`unknown') FEATURE(`nouucp', `reject') MAILER(`local') MAILER(`smtp')

These macros are not sendmail commands; they are input for the

m4 macro processor. The few lines

shown above are the active lines in the

tcpproto.mc file. They are preceded by a

section of comments, not shown here, that is discarded by m4 because it follows a divert(-1) command, which diverts the

output to the “bit bucket.” This section of the file begins with a

divert(0) command, which means

these commands should be processed and that the results should be

directed to standard output.

The dnl command that appears at the end of the divert(0) line is used to prevent unwanted

lines from appearing in the output file. dnl deletes everything up to the next

newline. It affects the appearance, but not the function, of the

output file. dnl can appear at

the end of any macro command. It can also be used at the beginning

of a line. When it is, the line is treated as a comment.

The VERSIONID macro is used for version control. Usually the value passed in the macro call is a version number in RCS (Release Control System) or SCCS (Source Code Control System) format. This macro is optional, and we can just ignore it.

The OSTYPE macro defines operating system-specific

information for the configuration. The

cf/ostype directory contains almost 50

predefined operating system macro files. The OSTYPE macro is

required and the value passed in the OSTYPE macro call must match

the name of one of the files in the directory. Examples of values

are bsd4.4, solaris8, and linux.

The FEATURE macro defines optional features to be included

in the sendmail.cf file. The nouucp feature in the example shown says

that UUCP addresses are not used on this system. The argument

reject says that local addresses

that use the UUCP bang syntax (i.e., contain an ! in the local part) will be rejected.

Recall that in the previous section we identified

tcpproto.mc as the prototype file for systems

that have no UUCP connections. Another prototype file would have

different FEATURE values.

The prototype file ends with the mailer macros. These must be the last macros in the input file. The example shown above specifies the local mailer macro and the SMTP mailer macro.

The MAILER(local) macro includes the local mailer that delivers local mail between users of the system and the prog mailer that sends mail files to programs running on the system. All the generic macro configuration files include the MAILER(local) macro because the local and prog mailers provide essential local mail delivery services.

The MAILER(smtp) macro includes all of the mailers needed to send SMTP mail over a TCP/IP network. The mailers included in this set are:

- smtp

This mailer can handle traditional 7-bit ASCII SMTP mail. It is outmoded because most modern mail networks handle a variety of data types.

- esmtp

This mailer supports Extended SMTP (ESMTP). It understands the ESMTP protocol extensions and it can deal with the complex message bodies and enhanced data types of MIME mail. This is the default mailer used for SMTP mail.

- smtp8

This mailer sends 8-bit data to the remote server, even if the remote server does not indicate that it can support 8-bit data. Normally, a server that supports 8-bit data also supports ESMTP and thus can advertise its support for 8-bit data in the response to the EHLO command. (See Chapter 3 for a description of the SMTP protocol and the EHLO command.) It is possible, however, to have a connection to a remote server that can support 8-bit data but does not support ESMTP. In that rare circumstance, this mailer is available for use.

- dsmtp

This mailer allows the destination system to retrieve mail queued on the server. Normally, the source system sends mail to the destination in what might be called a “push” model, where the source pushes mail out to the destination. On demand, SMTP allows the destination to “pull” mail down from the mail server when it is ready to receive the mail. This mailer implements the ETRN command that permits on-demand delivery. (The ETRN protocol command is described in RFC 1985.)

- relay

This mailer is used when SMTP mail must be relayed through another mail server. Several different mail relay hosts can be defined.

Every server that is connected to or communicates with the Internet uses the MAILER(smtp) set of mailers, and most systems on isolated networks use these mailers because they use TCP/IP on their enterprise network. Despite the fact that the vast majority of sendmail systems require these mailers, installing them is not the default. To support SMTP mail, you must have the MAILER(smtp) macro in your configuration, which is why it is included in the prototype file.

In addition to these two important sets of mailers, there are nine other sets of mailers available with the MAILER command, all of which are covered in Appendix E. Most of them are of very little interest for an average configuration. The two sets of mailers included in the tcpproto.mc configuration are the only ones that most administrators ever use.

To create a sample sendmail.cf from the

tcpproto.mc prototype file, copy the prototype

file to a work file. Edit the work file to change the OSTYPE line

from unknown to the correct value

for your operating system, e.g., solaris8 or linux. In the example we use sed to change unknown to linux. We store the result in a file we

call linux.mc:

# sed 's/unknown/linux/' < tcpproto.mc > linux.mcThen enter the m4

command:

# m4 ../m4/cf.m4 linux.mc > sendmail.cfThe sendmail.cf file output by the

m4 command is in the correct

format to be read by the sendmail program. With the exception of how

UUCP addresses are handled, the output file produced above is

similar to the sample generic-linux.cf

configuration file delivered with the sendmail distribution.

OSTYPE is not the only thing in the macro file that can be modified to create a custom configuration. There are a large number of configuration options, all of which are explained in Appendix E. As an example we modify a few options to create a custom configuration that converts user@host email addresses originating from our computer into firstname.lastname@domain. To do this, we create two new configuration files: a macro file with specific values for the domain that we name wrotethebook.com.m4, and a modified macro control file, linux.mc, that calls the new wrotethebook.com.m4 file.

We create the new macro file wrotethebook.com.m4 and place it in the cf/domain directory. The new file contains the following:

$ cat domain/wrotethebook.com.m4

MASQUERADE_AS(wrotethebook.com)

FEATURE(masquerade_envelope)

FEATURE(genericstable)These lines say that we want to hide the real hostname and

display the name wrotethebook.com in its place

in outbound email addresses. Also, we want to do this on “envelope”

addresses as well as message header addresses. The first two lines

handle the conversion of the host part of the outbound email

address. The last line says that we will use the generic address conversion database, which converts login usernames to any value

we wish to convert the user part of the outbound address. We must

build the database by creating a text file with the data we want and

processing that file through the makemap command that comes with

sendmail.

The format of the database can be very simple:

dan Dan.Scribner tyler Tyler.McCafferty pat Pat.Stover willy Bill.Wright craig Craig.Hunt

Each line in the file has two fields: the first field is the

key, which is the login name, and the second field is the user’s

real first and last names separated by a dot. Fields are separated

by spaces. Using this database, a query for dan will return the value Dan.Scribner. A small database such as

this one can be easily built by hand. On a system with a large

number of existing user accounts, you may want to automate this

process by extracting the user’s login name and first and last names

from the /etc/passwd file. The gcos field of the

/etc/passwd file often contains the user’s real

name.[113]

Once the data is in a text file, convert it to a database with

the makemap command. The makemap command is included in the sendmail distribution. The

syntax of the makemap command

is:

makemap

type namemakemap reads the standard

input and writes the database out to a file it creates using the

value provided by name as the filename.

The type field identifies the database

type. The most commonly supported database types for sendmail are

dbm, btree, and hash.[114] All of these types can be made with the makemap command.

Assume that the data shown above has been put in a file named realnames. The following command converts that file to a database:

# makemap hash genericstable < realnamesmakemap reads the text file

and produces a database file called

genericstable . The database maps login names to real names, e.g.,

the key willy returns the value

Bill.Wright.

Now that we have created the database, we create a new

sendmail configuration file to use it. All of the m4 macros related to using the database

are in the wrotethebook.com.m4 file. We need to

include that file in the configuration. To do that, add a DOMAIN(wrotethebook.com) line to the macro

control file (linux.mc) and then process the

linux.mc through m4. The following grep command shows what the macros in the

file look like after the change:

# grep '^[A-Z]' linux.mc VERSIONID(`$Id: ch10.xml,v 1.9 2004/09/22 19:24:26 marti Exp $') OSTYPE(`linux') DOMAIN(`wrotethebook.com') FEATURE(`nouucp', `reject') MAILER(`local') MAILER(`smtp') # m4 ../m4/cf.m4 linux.mc > sendmail.cf

Use a prototype mc file as the starting

point of your configuration if you install sendmail from the

tar file. To use the latest

version of sendmail you must build a compatible

sendmail.cf file using the m4 macros. Don’t attempt to use an old

sendmail.cf file with a new version of

sendmail; you’ll just cause yourself grief. As you can see from the

sample above, m4 configuration

files are very short and can be constructed from only a few macros.

Use m4 to build a fresh

configuration every time you upgrade sendmail.

Conversely, you should not use a

sendmail.cf file created from the prototype

files found in the sendmail distribution with an old version of

sendmail. Features in these files require that you run a compatible

version of sendmail, which means it is necessary to recompile

sendmail to use the new configuration file.[115] This is not something every system administrator will

choose to do, because some systems don’t have the correct libraries;

others don’t even have a C compiler! If you choose not to recompile

sendmail, you can use the sample sendmail.cf

file provided with your system as a starting point. However, if you

have major changes planned for your configuration, it is probably

easier to recompile sendmail and build a new configuration with

m4 than it is to make major

changes directly to the sendmail.cf.

In the next part of this chapter, we use one of the sample

sendmail.cf files provided with

Linux. The specific file we start with is generic-linux.cf found in the cf/cf directory of the sendmail

distribution. All of the things we discuss in the remainder of the

chapter apply equally well to sendmail.cf files that are produced by

m4. The structure of a

sendmail.cf file, the commands that it

contains, and the tools used to debug it are universal.

Most sendmail.cf files have more or less the same structure because most are

built from the standard m4 macros.

Therefore, the files provided with your system probably are similar to

the ones used in our examples. Some systems use a different structure,

but the functions of the sections described here will be found

somewhere in most sendmail.cf files.

The Linux file, generic-linux.cf, is our example of sendmail.cf file structure. The section labels from the sample file are used here to provide an overview of the sendmail.cf structure. These sections will be described in greater detail when we modify a sample configuration. The sections are:

- Local Information

Defines the information that is specific to the individual host. In the generic-linux.cf file, Local Information defines the hostname, the names of any mail relay hosts, and the mail domain. It also contains the name that sendmail uses to identify itself when it returns error messages, the message that sendmail displays during an SMTP login, and the version number of the sendmail.cf file. (Increase the version number each time you modify the configuration.) This section is usually customized during configuration.

- Options

Defines the sendmail options. This section usually requires no modifications.

- Message Precedence

Defines the various message precedence values used by sendmail. This section is not modified.

- Trusted Users

Defines the users who are trusted to override the sender address when they are sending mail. This section is not modified. Adding users to this list is a potential security problem.

- Format of Headers

Defines the format of the headers that sendmail inserts into mail. This section is not modified.

- Rewriting Rules

Defines the rules used to rewrite mail addresses. Rewriting Rules contains the general rules called by sendmail or other rewrite rules. This section is not modified during the initial sendmail configuration. Rewrite rules are usually modified only to correct a problem or to add a new service.

- Mailer Definitions

Defines the instructions used by sendmail to invoke the mail delivery programs. The specific rewrite rules associated with each individual mailer are also defined in this section. The mailer definitions are usually not modified. However, the rewrite rules associated with the mailers are sometimes modified to correct a problem or to add a new service.

The section labels in the sample file delivered with your system may be different from these. However, the structure of your sample file is probably similar to the structure discussed above in these ways:

The information that is customized for each host is probably at the beginning of the file.

Similar types of commands (option commands, header commands, etc.) are usually grouped together.

The bulk of the file consists of rewrite rules.

The last part of the file probably contains mailer definitions intermixed with the rewrite rules that are associated with the individual mailers.

Look at the comments in your sendmail.cf file. Sometimes these comments provide valuable insight into the file structure and the things that are necessary to configure a system.

It’s important to realize how little of sendmail.cf needs to be modified for a typical system. If you pick the right sample file to work from, you may need to modify only a few lines in the first section. From this perspective, sendmail configuration appears to be a trivial task. So why are system administrators intimidated by it? It is largely because of the difficult syntax of the sendmail.cf configuration language.

Every time sendmail starts up, it reads sendmail.cf. For this reason, the syntax of the sendmail.cf commands is designed to be easy for sendmail to parse—not necessarily easy for humans to read. As a consequence, sendmail commands are very terse, even by Unix standards.

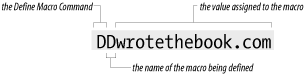

The configuration command is not separated from its variable or value by any spaces. This “run together” format makes the commands hard to read. Figure 10-2 illustrates the format of a command. In the figure, a define macro command assigns the value wrotethebook.com to the macro D.

Starting with version 8 of sendmail, variable names are no longer

restricted to a single character. Long variable names, enclosed in

braces, are now acceptable. For example, the define macro shown in Figure 10-2 could be written:

D{Domain}wrotethebook.comLong variable names are easier to read and provide for more choices than the limited set provided by single character names. However, the old-fashioned, short variable names are still common. This terse syntax can be very hard to decipher, but it helps to remember that the first character on the line is always the command. From this single character you can determine what the command is and therefore its structure. Table 10-1 lists the sendmail.cf commands and their syntax.

Table 10-1. sendmail configuration commands

Command | Syntax | Function |

|---|---|---|

Version Level | Vlevel[/vendor] | Specify version level. |

Define Macro | Dxvalue | Set macro x to value. |

Define Class | Ccword1[ word2] ... | Set class c to word1 word2 .... |

Define Class | Fcfile | Load class c from file. |

Set Option | Ooption=value | Set option to value. |

Trusted Users | Tuser1[ user2 ...] | Trusted users are user1 user2 .... |

Set Precedence | Pname=number | Set name to precedence number. |

Define Mailer | Mname, {field=value} | Define mailer name. |

Define Header | H[?mflag?]name:format | Set header format. |

Set Ruleset | Sn | Start ruleset number n. |

Define Rule | Rlhs rhs comment | Rewrite lhs patterns to rhs format. |

Key File | Kname type [argument] | Define database name. |

The following sections describe each configuration command in more detail.

The version level command is an optional command not found in all

sendmail.cf files. You don’t add a V command to the sendmail.cf file or

change one if it is already there. The V command is inserted into the configuration

file when it is first built from m4

macros or by the vendor.

The level number on the V command line indicates the version level

of the configuration syntax. V1 is the oldest configuration syntax and

V9 is the version supported by sendmail 8.11.3. Every level in between

adds some feature extensions. The vendor

part of the V command identifies if

any vendor-specific syntax is supported. The default

vendor value for the sendmail distribution

is Berkeley.

The V command tells the

sendmail executable the level of syntax and commands required to

support this configuration. If the sendmail program cannot support the

requested commands and syntax, it displays the following error

message:

# /usr/lib/sendmail -Ctest.cf

Warning: .cf version level (9) exceeds sendmail version 8.9.3+Sun functionality (8):

Operation not permittedThis error message indicates that this sendmail program supports

level 8 configuration files with Sun syntax extensions.[116] The example was produced on a Solaris 8 system running

the sendmail program that came with the operating system. In the

example we attempted to read a configuration file that was created by

the m4 macros that came with

sendmail 8.11.3. The syntax and functions needed by the configuration

file are not available in the sendmail program. To use this

configuration file, we would have to compile a newer version of the

sendmail program. See Appendix E for

an example of compiling sendmail.

You will never change the values on a V command. You might, however, need to

customize some D commands.

The define macro command (D) defines a

macro and stores a value in it. Once the macro is defined, it is used

to provide the stored value to other sendmail.cf

commands and directly to sendmail itself. This allows sendmail

configurations to be shared by many systems simply by modifying a few

system-specific macros.

A macro name can be any single ASCII character or a word

enclosed in curly braces. Use long names for user-created macros.

sendmail’s own internal macros use most of the available letters and

special characters as names. Additionally, a large number of long

macro names are already defined. This does not mean that you won’t be

called upon to name a macro, but it does mean you will have to be

careful that your name doesn’t conflict with a name that has already

been used. Internal macros are sometimes defined in the

sendmail.cf file. Appendix E provides a complete list of

sendmail’s internal macros. Refer to that list when creating a

user-defined macro to avoid conflicting with an internal macro. To

retrieve the value stored in a macro, reference it as $ x, where

x is the macro name. Macros are expanded when the

sendmail.cf file is read. A special syntax,

$&

x, is used to expand macros when they are

referenced. The $&

x syntax is only used with certain internal

macros that change at runtime.

The code below defines the macros {our-host}, M, and Q. After this code

executes, ${our-host} returns

crab, $M

returns wrotethebook.com, and $Q returns

crab.wrotethebook.com. This sample code defines Q

as containing the value of {our-host} (which is ${our-host}), plus a literal dot, plus the

value of M ($M).

D{our-host}crab

DMwrotethebook.com

DQ${our-host}.$MIf you customize your sendmail.cf file, it will probably be necessary to modify some macro definitions. The macros that usually require modification define site-specific information, such as hostnames and domain names.

A macro definition can contain a conditional. Here’s a conditional:

DX$g$?x ($x)$.

The D is the define macro

command; X is the macro being

defined; and $g says to use the

value stored in macro g. But what

does $?x ($x)$. mean? The

construct $?x is a conditional.

It tests whether macro x has a

value set. If the macro has been set, the text following the

conditional is interpreted. The $. construct ends the conditional.

Given this, the assignment of macro X is interpreted as follows: X is assigned the value of g; and if x is set, X is also assigned a literal blank, a

literal left parenthesis, the value of x, and a literal right parenthesis.

So if g contains

chunt@wrotethebook.com and x contains Craig Hunt, X will

contain:

chunt@wrotethebook.com (Craig Hunt)

The conditional can be used with an “else” construct, which is

$|. The full syntax of the

conditional is:

$?x text1$|text2$.

This is interpreted as:

if (

$?)xis set;use

text1;else (

$|);use

text2;end if (

$.).

Two commands, C and F, define sendmail classes. A class

is similar to an array of values. Classes are used for anything

with multiple values that are handled in the same way, such as

multiple names for the local host or a list of uucp hostnames. Classes allow sendmail to

compare against a list of values instead of against a single value.

Special pattern matching symbols are used with classes. The $= symbol matches any value in a class, and

the $~ symbol matches any value not

in a class. (More on pattern matching later.)

Like macros, classes can have single-character names or long names enclosed in curly braces. User-created classes use long names that do not conflict with sendmail’s internal names. (See Appendix E for a complete list of the names that sendmail uses for its internal class values.) Class values can be defined on a single line, on multiple lines, or loaded from a file. For example, class w is used to define all of the hostnames by which the local host is known. To assign class w the values goober and pea, you can enter the values on a single line:

Cwgoober pea

Or you can enter the values on multiple lines:

Cwgoober Cwpea

You can also use the F

command to load the class values from a file. The F command reads a file and stores the words

found there in a class variable. For example, to define class w and

assign it all of the strings found in

/etc/mail/local-host-names, use:[117]

Fw/etc/mail/local-host-names

You may need to modify a few class definitions when creating

your sendmail.cf file. Frequently information

relating to uucp, to alias

hostnames, and to special domains for mail routing is defined in class

statements. If your system has a uucp connection as well as a TCP/IP

connection, pay particular attention to the class definitions. But in

any case, check the class definitions carefully and make sure they

apply to your configuration.

Here we grep the Linux sample

configuration file for lines beginning with C or F:

% grep '^[CF]' generic-linux.cf

Cwlocalhost

Fw/etc/mail/local-host-names

CP.

CO @ % !

C..

C[[

FR-o /etc/mail/relay-domains

C{E}root

CPREDIRECTThis grep shows that

generic-linux.cf defines classes w, P, O, ., [,

R, and E. w contains the host’s alias hostnames. Notice that values

are stored in w with both a C

command and an F command. Unlike a

D command, which overwrites the

value stored in a macro, the commands that store values in class

arrays are additive. The C command

and the F command at the start of

this listing add values to class w. Another example of the additive

nature of C commands is class P. P

holds pseudo-domains used for mail routing. The first C command affecting class P stores a dot in

the array. The last command in the list adds REDIRECT to class

P.

Class O stores operators that cannot be part of a valid

username. The classes . (dot) and

[ are primarily of interest because

they show that variable names do not have to be alphabetic characters

and that sometimes arrays have only one value. E lists the usernames

that should always be associated with the local host’s fully qualified

domain name, even if simplified email addresses are being used for all

other users. (More on simplified addresses later.) Notice that even a

single character class name, in this case E, can be enclosed in curly

braces.

Remember that your system will be different. These same class names may be assigned other values on your system, and are only presented here as an example. Carefully read the comments in your sendmail.cf file for guidance as to how classes and macros are used in your configuration.

Many class names are reserved for internal sendmail use. All internal classes defined in sendmail version 8.11 are shown in Appendix E. Only class w, which defines all of the hostnames the system will accept as its own, is commonly modified by system administrators who directly configure the sendmail.cf file.

The option (O) command is used

to define the sendmail environment. Use the O command to set values appropriate for your

installation. The value assigned to an option is a string, an integer,

a Boolean, or a time interval, as appropriate for the individual

option. All options define values used directly by sendmail.

There are no user-created options. The meaning of each sendmail option is defined within sendmail itself. Appendix E lists the meaning and use of each option, and there are plenty of them.

A few sample options from the

generic-linux.cf file are shown below. The

AliasFile option defines the name of the sendmail

aliases file as

/etc/mail/aliases. If you want to put the

aliases file elsewhere, change this option. The

TempFileMode option defines the default file mode as

0600 for temporary files created by

sendmail in /var/spool/mqueue. The Timeout.queuereturn option sets the timeout interval for

undeliverable mail, here set to five days (5d). These options show the kind of general

configuration parameters set by the option command.

# location of alias file O AliasFile=/etc/mail/aliases # temporary file mode O TempFileMode=0600 # default timeout interval O Timeout.queuereturn=5d

The syntax of the option command shown in this example and in

Appendix E was introduced in

sendmail version 8.7.5. Prior to that, the option command used a

syntax more like the other sendmail commands. The old syntax is:

O

ovalue, where O is the command,

o is the single character option name, and

value is the value assigned to the option.

The options shown in the previous discussion, if written in the old

syntax, would be:

# location of alias file OA/etc/aliases # temporary file mode OF0600 # default timeout interval OT5d

If your configuration uses the old option format, it is dangerously out of date and should be upgraded. See Appendix E for information on downloading, compiling, and installing the latest version of sendmail.

Most of the options defined in the sendmail.cf file that comes with your system don’t require modification. People change options settings because they want to change the sendmail environment, not because they have to. The options in your configuration file are almost certainly correct for your system.

The T command defines a

list of users who are trusted to override the sender

address using the mailer -f

flag.[118] Normally the trusted users are defined as

root, uucp, and

daemon. Trusted users can be specified as a list

of usernames on a single command line or on multiple command lines.

The users must be valid usernames from the

/etc/passwd file.

The most commonly defined trusted users are:

Troot Tdaemon Tuucp

Do not modify this list. Additional trusted users increase the possibility of security problems.

Precedence is one of the factors used by sendmail to assign priority to

messages entering its queue. The P

command defines the message precedence values available to sendmail

users. The higher the precedence number, the greater the precedence of

the message. The default precedence of a message is 0. Negative

precedence numbers indicate especially low-priority mail. Error

messages are not generated for mail with a negative precedence number,

making low priorities attractive for mass mailings. Some commonly used

precedence values are:

Pfirst-class=0 Pspecial-delivery=100 Plist=-30 Pbulk=-60 Pjunk=-100

To specify a desired precedence, add a Precedence header to your outbound message. Use the text name from

the P command in the Precedence

header to set the specific precedence of the message. Given the

precedence definitions shown above, a user who wanted to avoid

receiving error messages for a large mailing could select a message

precedence of -60 by including the following header line in the

mail:

Precedence: bulk

The five precedence values shown are probably more than you’ll ever need.

The H command defines the format of header lines that sendmail inserts

into messages. The format of the header command is the H command, optional header flags enclosed in

question marks, a header name, a colon, and a header template. The

header template is a combination of literals and macros that are

included in the header line. Macros in the header template are

expanded before the header is inserted in a message. The same

conditional syntax used in macro definitions can be used in header

templates, and it functions in exactly the same way: it allows you to

test whether a macro is set and to use another value if it is not

set.

The header template field can contain the $> name syntax

that is used in rewrite rules. When used in a header template, the

$>

name syntax allows you to call the ruleset

identified by name to process an incoming

header. This can be useful for filtering headers in order to reduce

spam email. We discuss rulesets, rewrite rules, the $> name

syntax, and how these things are used later in this chapter.

The header flags often arouse more questions than they merit. The function of the flags is very simple. The header flags control whether or not the header is inserted into mail bound for a specific mailer. If no flags are specified, the header is used for all mailers. If a flag is specified, the header is used only for a mailer that has the same flag set in the mailer’s definition. (Mailer flags are listed in Appendix E.) Header flags control only header insertion. If a header is received in the input, it is passed to the output regardless of the flag settings.

Some sample header definitions from the generic-linux.cf sample file are:

H?P?Return-Path: <$g> HReceived: $?sfrom $s $.$?_($?s$|from $.$_) H?D?Resent-Date: $a H?D?Date: $a H?F?Resent-From: $?x$x <$g>$|$g$. H?F?From: $?x$x <$g>$|$g$. H?x?Full-Name: $x H?M?Resent-Message-Id: <$t.$i@$j> H?M?Message-Id: <$t.$i@$j>

The headers provided in your system’s sendmail.cf are sufficient for most installations. It’s unlikely you’ll ever need to change them.

The M commands define the mail delivery programs used by sendmail. The

syntax of the command is:

Mname, {field=value}

name is an arbitrary name used

internally by sendmail to refer to this mailer. The name doesn’t

matter as long as it is used consistently within the

sendmail.cf file to refer to this mailer. For

example, the mailer used to deliver SMTP mail within the local domain

might be called smtp on one system and

ether on another system. The function of both

mailers is the same; only the names are different.

There are a few exceptions to this freedom of choice. The mailer that delivers local mail to users on the same machine must be called local, and a mailer named local must be defined in the sendmail.cf file. Three other special mailer names are:

- prog

Delivers mail to programs.

- *file*

Sends mail to files.

- *include*

Directs mail to

:include:lists.

Of these, only the prog mailer is defined in the sendmail.cf file. The other two are defined internally by sendmail.

Despite the fact that the mailer name can be anything you want,

it is usually the same on most systems because the mailers in the

sendmail.cf file are built by standard m4 macros. In the

linux.mc configuration created earlier, the

MAILER(local) macro created the prog and

local mailers, and the MAILER(smtp) macro created

the smtp, esmtp,

smtp8, dsmtp, and

relay mailers. Every system you work with will

probably have this same set of mailer names.

The mailer name is followed by a comma-separated list of field=value pairs that define the characteristics of the mailer. Table 10-2 shows the single-character field identifiers and the contents of the value field associated with each of them. Most mailers don’t require all of these fields.

Table 10-2. Mailer definition fields

Field | Meaning | Contents | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

P | Path | Path of the mailer | P=/bin/mail |

F | Flags | sendmail flags for this mailer | F=lsDFMe |

S | Sender | Rulesets for sender addresses | S=10 |

R | Recipient | Rulesets for recipient addresses | R=20 |

A | Argv | The mailer’s argument vector | A=sh -c $u |

E | Eol | End-of-line string for the mailer | E=\r\n |

M | Maxsize | Maximum message length | M=100000 |

L | Linelimit | Maximum line length | L=990 |

D | Directory | prog mailer’s execution directory | D=$z:/ |

U | Userid | User and group ID used to run mailer | U=uucp:wheel |

N | Nice | nice value used to run mailer | N=10 |

C | Charset | Content-type for 8-bit MIME characters | C=iso8859-1 |

T | Type | Type information for MIME errors | T=dns/rfc822/smtp |

The Path (P) fields contain either the path to the mail delivery

program or the literal string [IPC]. Mailer definitions that specify

P=[IPC] use sendmail to deliver

mail via SMTP.[119] The path to a mail delivery program varies from system

to system depending on where the systems store the programs. Make sure

you know where the programs are stored before you modify the Path

field. If you use a sendmail.cf file from another

computer, make sure that the mailer paths are valid for your system.

If you use m4 to build the

configuration, the path will be correct.

The Flags (F) field contains the sendmail flags used for this mailer. These are the mailer flags referenced earlier in this chapter under “Defining Mail Headers,” but mailer flags do more than just control header insertion. There are a large number of flags. Appendix E describes all of them and their functions.

The Sender (S) and the Recipient (R) fields identify the rulesets used to rewrite the sender and recipient addresses for this mailer. Each ruleset is identified by its number. We’ll discuss rulesets more later in this chapter, and we will refer to the S and R values when troubleshooting the sendmail configuration.

The Argv (A) field defines the argument vector passed to the mailer.

It contains, among other things, macro expansions that provide the

recipient username (which is $u),[120] the recipient hostname ($h), and the sender’s From address ($f). These macros are expanded before the

argument vector is passed to the mailer.

The End-of-line (E) field defines the characters used to mark the end of a line. A carriage return and a line feed (CRLF) is the default for SMTP mailers.

Maxsize (M) defines, in bytes, the longest message that this mailer will handle. This field is used most frequently in definitions of UUCP mailers.

Linelimit (L) defines, in bytes, the maximum length of a line that can be contained in a message handled by this mailer. This mailer field was introduced in sendmail V8. Previous versions of sendmail limited lines to 80 characters because this was the limit for SMTP mail before MIME mail was introduced.

The Directory (D) field specifies the working directory for the

prog mailer. More than one directory can be

specified for the directory field by separating the directory paths

with colons. The example in Table

10-2 tells prog to use the recipient’s

home directory, which is the value returned by the internal macro

$z. If that directory is not

available, it should use the root (/) directory.

The Userid (U) field is used to specify the default user and the

group ID used to execute the mailer. The example U=uucp:wheel says that the mailer should be

run under the user ID uucp and the group ID

wheel. If no value is specified for the Userid

field, the value defined by the DefaultUser option is used.

Use Nice (N) to change the nice value

for the execution of the mailer. This allows you to change the

scheduling priority of the mailer. This is rarely used. If you’re

interested, see the nice manpage

for appropriate values.

The last two fields are used only for MIME mail. Charset (C)

defines the character set used in the Content-type

header when an 8-bit message is converted to MIME. If Charset is not

defined, the value defined in the DefaultCharSet option is used. If

that option is not defined, unknown-8bit is used as the default

value.

The Type (T) field defines the type information used in MIME error messages. MIME-type information defines the mailer transfer agent type, the mail address type, and the error code type. The default is dns/rfc822/smtp.

The following mailer definitions are from generic-linux.cf:

Mlocal, P=/usr/bin/procmail, F=lsDFMAw5:/|@qSPfhn9,

S=EnvFromL/HdrFromL, R=EnvToL/HdrToL, T=DNS/RFC822/X-Unix,

A=procmail -Y -a $h -d $u

Mprog, P=/bin/sh, F=lsDFMoqeu9, S=EnvFromL/HdrFromL,

R=EnvToL/HdrToL, D=$z:/, T=X-Unix/X-Unix/X-Unix,

A=sh -c $u

Msmtp, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuX, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=EnvToSMTP,

E=\r\n, L=990, T=DNS/RFC822/SMTP, A=TCP $h

Mesmtp, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuXa, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=EnvToSMTP,

E=\r\n, L=990, T=DNS/RFC822/SMTP, A=TCP $h

Msmtp8, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuX8, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=EnvToSMTP,

E=\r\n, L=990, T=DNS/RFC822/SMTP, A=TCP $h

Mdsmtp, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuXa%, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=EnvToSMTP,

E=\r\n, L=990, T=DNS/RFC822/SMTP, A=TCP $h

Mrelay, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuXa8, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=MasqSMTP,

E=\r\n, L=2040, T=DNS/RFC822/SMTP,A=TCP $hThis example contains the following mailer definitions:

A definition for local mail delivery, always called local. This definition is required by sendmail.

A definition for delivering mail to programs, always called prog. This definition is found in most configurations.

A definition for TCP/IP mail delivery, here called smtp.

A definition for an Extended SMTP mailer, here called esmtp.

A definition for an SMTP mailer that handles unencoded 8-bit data, here called smtp8.

A definition for on-demand SMTP, here called dsmtp.

A definition for a mailer that relays TCP/IP mail through an external mail relay host, here called relay.

A close examination of the fields in one of these mailer entries, for example the entry for the smtp mailer, shows the following:

MsmtpA mailer, arbitrarily named smtp, is being defined.

P=[IPC]The path to the program used for this mailer is

[IPC], which means delivery of this mail is handled internally by sendmail.F=mDFMuXThe sendmail flags for this mailer say that this mailer can send to multiple recipients at once; that Date, From, and Message-Id headers are needed; that uppercase should be preserved in hostnames and usernames; and that lines beginning with a dot have an extra dot prepended. Refer to Appendix E for more details.

S =EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTPThe sender address in the mail “envelope” is processed through ruleset

EnvFromSMTP, and the sender address in the message is processed through rulesetHdrFromSMTP. More on this later.R= EnvToSMTPAll recipient addresses are processed through ruleset

EnvToSMTP.E=\r\nLines are terminated with a carriage return and a line feed.

L=990This mailer will handle lines up to 990 bytes long.

T=DNS/RFC822/SMTPThe MIME-type information for this mailer says that DNS is used for hostnames, RFC 822 email addresses are used, and SMTP error codes are used.

A=TCP $hThe meaning of each option in an argument vector is exactly as defined on the manpage for the command; see the local mailer as an example. In the case of the smtp mailer, however, the argument refers to an internal sendmail process designed to deliver SMTP mail over a TCP connection. The macro

$his expanded to provide the recipient host ($h) address.

Despite this long discussion, don’t worry about mailer

definitions. The configuration file that is built by m4 for your operating system contains the

correct mailer definitions to run sendmail in a TCP/IP network

environment. You shouldn’t need to modify any mailer

definitions.

Rewrite rules are the heart of the sendmail.cf

file. Rulesets are groups of individual rewrite rules used to parse

email addresses from user mail programs and rewrite them into the form

required by the mail delivery programs. Each rewrite rule is defined by

an R command. The syntax of the

R command is:

Rpattern transformation commentThe fields in an R command are

separated by tab characters. The comment field is ignored by the system,

but good comments are vital if you want to have any hope of

understanding what’s going on. The pattern and transformation fields are

the heart of this command.

Rewrite rules match the input address against the pattern, and if a match is found, they rewrite the address in a new format using the rules defined in the transformation. A rewrite rule may process the same address several times because, after being rewritten, the address is again compared against the pattern. If it still matches, it is rewritten again. The cycle of pattern matching and rewriting continues until the address no longer matches the pattern.

The pattern is defined using macros, classes, literals, and special metasymbols. The macros, classes, and literals provide the values against which the input is compared, and the metasymbols define the rules used in matching the pattern. Table 10-3 shows the metasymbols used for pattern matching.

Table 10-3. Pattern matching metasymbols

Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

$@ | Match exactly zero tokens. |

$* | Match zero or more tokens. |

$+ | Match one or more tokens. |

$- | Match exactly one token. |

$=x | Match any token in class x. |

$~x | Match any token not in class x. |

$x | Match all tokens in macro x. |

$%x | Match any token in the NIS map named in macro x.[a] |

$!x | Match any token not in the NIS map named in macro x. |

$%y | Match any token in the NIS hosts.byname map. |

[a] This symbol is specific to Sun operating systems. | |

All of the metasymbols request a match for some number of tokens. A token is a string of characters in an email address delimited by an operator. The operators are the characters defined in the OperatorChars option. Operators are also counted as tokens when an address is parsed. For example:

becky@rodent.wrotethebook.com

This email address contains seven tokens: becky, @, rodent, ., wrotethebook, ., and com. This address would match the pattern:

$-@$+

The address matches the pattern because:

Many addresses, such as

hostmaster@apnic.net and

craigh@ora.com, match this pattern, but other

addresses do not. For example,

rebecca.hunt@wrotethebook.com does not match

because it has three tokens: rebecca, ., and hunt, before the @.

Therefore, it fails to meet the requirement of exactly one token

specified by the $- symbol. Using

the metasymbols, macros, and literals, patterns can be constructed to

match any type of email address.

When an address matches a pattern, the strings from the address

that match the metasymbols are assigned to indefinite tokens . The matching strings are called indefinite tokens

because they may contain more than one token value. The indefinite

tokens are identified numerically according to the relative position

in the pattern of the metasymbol that the string matched. In other

words, the indefinite token produced by the match of the first

metasymbol is called $1; the match of the second symbol is called $2;

the third is $3; and so on. When the address

becky@rodent.wrotethebook.com matched the pattern

$-@$+, two indefinite tokens were

created. The first is identified as $1 and contains the single token,

becky, that matched the $- symbol.

The second indefinite token is $2 and contains the five tokens—rodent,

., wrotethebook, ., and com—that matched the $+ symbol. The indefinite tokens created by

the pattern matching can then be referenced by name ($1, $2, etc.)

when rewriting the address.

A few of the symbols in Table 10-3 are used only in

special cases. The $@ symbol is

normally used by itself to test for an empty, or null, address. The

symbols that test against NIS maps can only be used on Sun systems

that run the sendmail program that Sun provides with the operating

system. We’ll see in the next section that systems running basic

sendmail can use NIS maps, but only for transformation—not for pattern

matching.

The transformation field, from the right-hand side of the rewrite rule, defines the format used for rewriting the address. It is defined with the same things used to define the pattern: literals, macros, and special metasymbols. Literals in the transformation are written into the new address exactly as shown. Macros are expanded and then written. The metasymbols perform special functions. The transformation metasymbols and their functions are shown in Table 10-4.

Table 10-4. Transformation metasymbols

Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

$n | Substitute indefinite token n. |

$[name$] | Substitute the canonical form of name. |

$map key$@argument $:default$) | Substitute a value from database map indexed by key. |

$>n | Call ruleset n. |

$@ | Terminate ruleset. |

$: | Terminate rewrite rule. |

The $ n symbol, where

n is a number, is used for the indefinite

token substitution discussed above. The indefinite token is expanded

and written to the “new” address. Indefinite token substitution is

essential for flexible address rewriting. Without it, values could not

be easily moved from the input address to the rewritten address. The

following example demonstrates this.

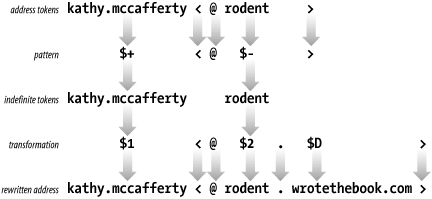

Addresses are always processed by several rewrite rules. No one rule tries to do everything. Assume the input address mccafferty@rodent has been through some preliminary processing and now is:

kathy.mccafferty<@rodent>

Assume the current rewrite rule is:

R$+<@$-> $1<@$2.$D> user@host -> user@host.domain

The address matches the pattern because it contains one or more

tokens before the literal <@,

exactly one token after the <@,

and then the literal >. The

pattern match produces two indefinite tokens that are used in the

transformation to rewrite the address.

The transformation contains the indefinite token $1, a literal

<@, indefinite token $2, a

literal dot (.), the macro D, and

the literal >. After the pattern

matching, $1 contains kathy.mccafferty and $2

contains rodent. Assume that the macro D was

defined elsewhere in the sendmail.cf file as

wrotethebook.com. In this case the input address

is rewritten as:

kathy.mccafferty<@rodent.wrotethebook.com>

Figure 10-3 illustrates

this specific address rewrite. It shows the tokens derived from the

input address and how those tokens are matched against the pattern. It

also shows the indefinite tokens produced by the pattern matching and

how the indefinite tokens and other values from the transformation are

used to produce the rewritten address. After rewriting, the address is

again compared to the pattern. This time it fails to match the pattern

because it no longer contains exactly one token between the literal

<@ and the literal >. So, no further processing is done by

this rewrite rule and the address is passed to the next rule in line.

Rules in a ruleset are processed sequentially, though a few

metasymbols can be used to modify this flow.

The $> n symbol calls ruleset

n and passes the address defined by the

remainder of the transformation to ruleset

n for processing. For example:

$>9 $1 % $2

This transformation calls ruleset 9 ($>9), and passes the contents of $1, a

literal %, and the contents of $2 to ruleset 9 for processing. When

ruleset 9 finishes processing, it returns a rewritten address to the

calling rule. The returned email address is then compared again to the

pattern in the calling rule. If it still matches, ruleset 9 is called

again.

The recursion built into rewrite rules creates the possibility

for infinite loops. sendmail does its best to detect possible loops,

but you should take responsibility for writing rules that don’t loop.

The $@ and the $: symbols are used to control processing

and to prevent loops. If the transformation begins with the $@ symbol, the entire ruleset is terminated

and the remainder of the transformation is the value returned by the

ruleset. If the transformation begins with the $: symbol, the individual rule is executed

only once. Use $: to prevent

recursion and to prevent loops when calling other rulesets. Use

$@ to exit a ruleset at a specific

rule.

The $[ name $] symbol converts a host’s nickname or its

IP address to its canonical name by passing the value

name to the name server for resolution. For

example, using the wrotethebook.com name servers,

$[mouse$] returns

rodent.wrotethebook.com and $[[172.16.12.1]$] returns

crab.wrotethebook.com.

In the same way that a hostname or address is used to look up a

canonical name in the name server database, the $( map

key $) syntax

uses the key to retrieve information from the

database identified by map. This is a more

generalized database retrieval syntax than the one that returns

canonical hostnames, and it is more complex to use. Before we get into

the details of setting up and using databases from within sendmail,

let’s finish describing the rest of the syntax of rewrite

rules.

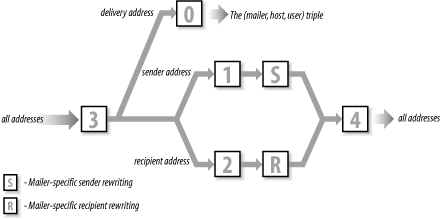

There is a special rewrite rule syntax that is used in ruleset 0. Ruleset 0 defines the triple (mailer, host, user) that specifies the mail delivery program, the recipient host, and the recipient user.

The special transformation syntax used to do this is:

$#mailer$@host$:user

An example of this syntax taken from the generic-linux.cf sample file is:

R$*<@$*>$* $#esmtp $@ $2 $: $1 < @ $2 > $3 user@host.domain

Assume the email address

david<@ora.wrotethebook.com> is processed

by this rule. The address matches the pattern $*<@$+>$* because:

The address has zero or more tokens (david) that match the first

$*symbol.The address has a literal <@.

The address has zero or more tokens (the five tokens in ora.wrotethebook.com) that match the requirement of the second

$*symbol.The address has a literal >.

The address has zero or more (in this case, zero) tokens that match the requirement of the last

$*symbol.

This pattern match produces two indefinite tokens. Indefinite token $1 contains david and $2 contains ora.wrotethebook.com. No other matches occurred, so $3 is null. These indefinite tokens are used to rewrite the address into the following triple:

$#smtp$@ora.wrotethebook.com$:david<@ora.wrotethebook.com>

The components of this triple are:

$#smtpsmtpis the internal name of the mailer that delivers the message.$@ora.wrotethebook.comora.wrotethebook.comis the recipient host.$:david<@ora.wrotethebook.com>david<@ora.wrotethebook.com>is the recipient user.

There are a few variations on the mailer triple syntax that are also used in the templates of some rules. Two of these variations use only the “mailer” component.

$#OKIndicates that the input address passed a security test. For example, the address is permitted to relay mail.

$#discardIndicates that the input address failed some security test and that the email message should be discarded.

Tip

Neither OK, discard, nor error (which is discussed in a second) is

declared in M commands like real

mailers. But the sendmail documentation refers to them as “mailers”

and so do we.

The $#OK and $#discard mailers are used in relay control

and security. The $#discard mailer

silently discards the mail and does not return an error message to the

sender. The $#error mailer also

handles undeliverable mail, but unlike $#discard, it returns an error message to

the sender. The template syntax used with the $#error mailer is more complex than the

syntax of either $#OK or $#discard. That syntax is shown here:

$#error $@dsn-code $:message

The mailer value must be $#error. The $: message field

contains the text of the error message that you wish to send. The

$@

dsn-code field is optional. If it is

provided, it appears before the message and

must contain a valid Delivery Status Notification (DSN) error code as defined

by RFC 1893, Mail System Status Codes.

DSN codes are composed of three dot-separated components:

-

class Provides a broad classification of the status. Three values are defined for class in the RFC:

2means success,4means temporary failure, and5means permanent failure.-

subject Classifies the error messages as relating to one of eight categories:

0(Undefined)The specific category cannot be determined.

1(Addressing)A problem was encountered with the address.

2(Mailbox)A problem was encountered with the delivery mailbox.

3(Mail system)The destination mail delivery system is having a problem.

4(Network)The network infrastructure is having a problem.

5(Protocol)A protocol problem was encountered.

6(Content)The message content caused a translation error.

7(Security)A security problem was reported.

-

detail Provides the details of the specific error. The detail value is meaningful only in context of the subject code. For example, x

.1.1means a bad destination user address and x.1.2means a bad destination host address, while x.2.1means the mailbox is disabled and x.2.2means the mailbox is full. There are far too many detail codes to list here. See RFC 1893 for a full list.

An error message written to use the DSN format might be:

R<@$+> $#error$@5.1.1$:"user address required"

This rule returns the DSN code 5.1.1 and the message "user address required" when the address

matches the pattern. The DSN code has a 5 in the class field, meaning it is a

permanent failure; a 1 in the

subject field, meaning it is an addressing failure; and a 1 in the detail field, meaning that, given

the subject value of 1, it is a bad user address.

Error codes and the error syntax are part of the advanced

configuration options used for relay control and security. These

values are generated by the m4

macro used to select these advanced features. These values are very

rarely placed in the sendmail.cf file by a system

administrator

directly.

External databases can be used to transform addresses in rewrite rules. The database is included in the transformation part of a rule by using the following syntax:

$(map key[$@argument...] [$:default] $)

map is the name assigned to the

database within the sendmail.cf file. The name

assigned to map is not limited by the

rules that govern macro names. Like mailer names, map names are used

only inside of the sendmail.cf file and can be

any name you choose. Select a simple descriptive name, such as

“users” or “mailboxes”. The map name is assigned with a K command. (More on the K command in a moment.)

key is the value used to index into

the database. The value returned from the database for this key is

used to rewrite the input address. If no value is returned, the

input address is not changed unless a

default value is provided.

An argument is an additional value

passed to the database procedure along with the key. Multiple

arguments can be used, but each argument must start with $@. The argument can be used by the

database procedure to modify the value it returns to sendmail. It is

referenced inside the database as % n, where

n is a digit that indicates the order in

which the argument appears in the rewrite rule—%1, %2, and so

on—when multiple arguments are used. (Argument %0 is the

key.)

An example will make the use of arguments clear. Assume the following input address:

tom.martin<@sugar>

Further, assume the following database with the internal sendmail name of “relays”:

oil %1<@relay.fats.com> sugar %1<@relay.calories.com> salt %1<@server.sodium.org>

Finally, assume the following rewrite rule:

R$+<@$-> $(relays $2 $@ $1 $:$1<@$2> $)

The input address tom.martin<@sugar> matches the pattern because it has one or more tokens (tom.martin) before the literal <@ and exactly one token (sugar) after it. The pattern matching creates two indefinite tokens and passes them to the transformation. The transformation calls the database (relays) and passes it token $2 (sugar) as the key and token $1 (tom.martin) as the argument. If the key is not found in the database, the default ($1<@$2>) is used. In this case, the key is found in the database. The database program uses the key to retrieve “%1@relay.calories.com”, expands the %1 argument, and returns “tom.martin@relay.calories.com” to sendmail, which uses the returned value to replace the input address.

Before a database can be used within sendmail, it must be

defined. This is done with the K

command. The syntax of the K command is:

Kname type[arguments]

name is the name used to reference

this database within sendmail. In the example above, the

name is “relays”.

type is the class of database. The

type specified in the K command must match the database support

compiled into your sendmail. Most sendmail programs do not support

all database types, but a few basic types are widely supported.

Common types are hash, btree, and nis. There are many more, all of

which are described in Appendix

E.

arguments are optional. Generally,

the only argument is the path of the database file. Occasionally the

arguments include flags that are interpreted by the database

program. The full list of K

command flags that can be passed in the argument field is found in

Appendix E.

To define the “relays” database file used in the example above, we might enter the following command in the sendmail.cf file:

Krelays hash /etc/mail/relays

The name relays is simply a name you chose because it is descriptive. The database type hash is a type supported by your version of sendmail and was used by you when you built the database file. Finally, the argument /etc/mail/relays is the location of the database file you created.

Don’t worry if you’re confused about how to build and use database files within sendmail. We will revisit this topic later in the chapter and the examples will make the practical use of database files clear.

Rulesets are groups of associated rewrite rules that can be referenced by a

name or a number. The S command

marks the beginning of a ruleset and names it. In the S name command

syntax, name identifies the ruleset.

Optionally a number can also be assigned to the ruleset using the full

S

name=number syntax. In that case, the

ruleset can be referenced either by its name or its number. It is even

possible to identify a ruleset with a number instead of a name by

using the old S

number syntax. This form of the syntax is