Day 3: Advanced Views, Changes API, and Replicating Data

In Days 1 and 2, you learned how to perform basic CRUD operations and interact with views for finding data. Building on this experience, today we’ll take a closer look at views, dissecting the reduce part of the mapreduce equation. After that, we’ll develop some Node.js applications in JavaScript to leverage CouchDB’s unique Changes API. Lastly, we’ll discuss replication and how CouchDB handles conflicting data.

Creating Advanced Views with Reducers

Mapreduce-based views provide the means by which we can harness CouchDB’s indexing and aggregation facilities. In Day 2, all our views consisted solely of mappers. Now we’re going to add reducers to the mix, developing new capabilities against the data we imported from Jamendo in Day 2.

One great thing about the Jamendo data is its depth. Artists have albums, which have tracks; tracks, in turn, have attributes, including tags. We’ll now turn our attention to tags to see whether we can write a view to collect and count them. First, return to the New View page, set the design doc name to tags and the index name to by_name, and then enter the following map function:

| | function(doc) { |

| | (doc.albums || []).forEach(function(album){ |

| | (album.tracks || []).forEach(function(track){ |

| | (track.tags || []).forEach(function(tag){ |

| | emit(tag.idstr, 1); |

| | }); |

| | }); |

| | }); |

| | } |

This function digs into the artist document and then down into each album, each track, and finally each tag. For each tag, it emits a key-value pair consisting of the tag’s idstr property (a string representation of the tag, like "rock") and the number 1.

With the map function in place, click on the Reduce selector and choose CUSTOM. Enter the following in the text field:

| | function(key, values, rereduce) { |

| | return sum(values); |

| | } |

This code merely sums the numbers in the values list—which we’ll talk about momentarily once we’ve run the view. The output should be a series of JSON objects containing key/value pairs like this:

Key | Value |

|---|---|

"17sonsrecords" | 1 |

"17sonsrecords" | 1 |

"17sonsrecords" | 1 |

"17sonsrecords" | 1 |

"17sonsrecords" | 1 |

"acid" | 1 |

"acousticguitar" | 1 |

"acousticguitar" | 1 |

"action" | 1 |

"action" | 1 |

This shouldn’t be too surprising. The value is always 1 as we indicated in the mapper, and the Key fields exhibit as much repetition as there is in the tracks themselves. Notice, however, the Options button in the upper-right corner. Check the Reduce box, click Run Query, and then look at the table again. It should now look something like this:

Key | Value |

|---|---|

"17sonsrecords" | 5 |

"acid" | 1 |

"acousticguitar" | 2 |

"action" | 2 |

"adventure" | 3 |

"aksband" | 1 |

"alternativ" | 1 |

"alternativ" | 3 |

"ambient" | 28 |

"autodidacta" | 17 |

What happened? In short, the reducer reduced the output by combining like mapper rows in accordance with our Reducer Function. The CouchDB mapreduce engine works conceptually like the other mapreducers we’ve seen before (like MongoDB’s Mapreduce (and Finalize)). Specifically, here’s a high-level outline of the steps CouchDB takes to build a view:

-

Send documents off to the mapper function.

-

Collect all the emitted values.

-

Sort emitted rows by their keys.

-

Send chunks of rows with the same keys to the reduce function.

-

If there was too much data to handle all reductions in a single call, call the reduce function again but with previously reduced values.

-

Repeat recursive calls to the reduce function as necessary until no duplicate keys remain.

Reduce functions in CouchDB take three arguments: key, values, and rereduce. The first argument, key, is an array of tuples—two element arrays containing the key emitted by the mapper and the _id of the document that produced it. The second argument, values, is an array of values corresponding to the keys.

The third argument, rereduce, is a Boolean value that will be true if this invocation is a rereduction. That is, rather than being sent keys and values that were emitted from mapper calls, this call is sent the products of previous reducer calls. In this case, the key parameter will be null.

Stepping Through Reducer Calls

Let’s work through an example based on the output we just saw. Consider documents (artists) with tracks that have been tagged as “ambient.” The mappers run on the documents and emit key-value pairs of the form “ambient”/1. At some point, enough of these have been emitted that CouchDB invokes a reducer. That call might look like this:

| | reduce( |

| | [["ambient", id1], ["ambient", id2], ...], // keys are the same |

| | [1, 1, ...], // values are all 1 |

| | false // rereduce is false |

| | ) |

Recall that in our reducer function we take the sum of values. Because they’re all 1, the sum will simply be the length—effectively a count of how many tracks have the “ambient” tag. CouchDB keeps this return value for later processing. For the sake of this example, let’s call that number 10.

Some time later, after CouchDB has run these kinds of calls several times, it decides to combine the intermediate reducer results by executing a rereduce:

| | reduce( |

| | null, // key array is null |

| | [10, 10, 8], // values are outputs from previous reducer calls |

| | true // rereduce is true |

| | ) |

Our reducer function again takes the sum of values. This time, the values add up to 28. Rereduce calls may be recursive. They go on as long as there is reduction to be done, which means until all the intermediate values have been combined into one.

Most mapreduce systems, including the ones used by other databases we’ve covered in this book such as MongoDB, throw away the output of mappers and reducers after the work is done. In those systems, mapreduce is seen as a means to an end—something to be executed whenever the need arises, each time starting from scratch. Not so with CouchDB.

Once a view is codified into a design document, CouchDB will keep the intermediate mapper and reducer values until a change to a document would invalidate the data. At that time, CouchDB will incrementally run mappers and reducers to correct for the updated data. It won’t start from scratch, recalculating everything each time. This is the genius of CouchDB views. CouchDB is able to use mapreduce as its primary indexing mechanism by not tossing away intermediate data values.

Watching CouchDB for Changes

CouchDB’s incremental approach to mapreduce is an innovative feature, to be sure; it’s one of many that set CouchDB apart from other databases. The next feature we will investigate is the Changes API. This interface provides mechanisms for watching a database for changes and getting updates instantly.

The Changes API makes CouchDB a perfect candidate for a system of record. Imagine a multidatabase system where data is streaming in from several directions and other systems need to be kept up-to-date. Examples might include a search engine backed by Lucene or ElasticSeach or a caching layer implemented using memcached or Redis. You could have different maintenance scripts kick off in response to changes too—performing tasks such as database compaction and remote backups. In short, this simple API opens up a world of possibilities. Today we’ll learn how to harness it.

To make use of the API, we’re going to develop some simple client applications using Node.js.[36] Because Node.js is event-driven and code for it is written in JavaScript, it’s a natural fit for integrating with CouchDB. If you don’t already have Node.js, head over to the Node.js site and install the latest stable version (we use version 7.4.0).

The three flavors of the Changes API are polling, long-polling, and continuous. We’ll talk about each of these in turn. As always, we’ll start with cURL to get close to the bare metal and then follow up with a programmatic approach.

cURLing for Changes

The first and simplest way to access the Changes API is through the polling interface. Head to the command line, and try the following (the output is truncated for brevity; yours will differ):

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/_changes" |

| | { |

| | "results":[{ |

| | "seq":"10057-g1.....FqzAI2DMmw", |

| | "id":"370255", |

| | "changes":[{"rev":"1-a7b7cc38d4130f0a5f3eae5d2c963d85"}] |

| | },{ |

| | "seq":"10057-g1.....A0Y9NEs7RUb", |

| | "id":"370254", |

| | "changes":[{"rev":"1-2c7e0deec3ffca959ba0169b0e8bfcef"}] |

| | },{ |

| | ... many more records ... |

| | },{ |

| | "seq":"10057-g1.....U9OzMnILy7J", |

| | "id":"357995", |

| | "changes":[{"rev":"1-aa649aa53f2858cb609684320c235aee"}] |

| | }], |

| | "last_seq":100 |

| | } |

When you send a GET request for _changes with no other parameters, CouchDB will respond with everything it has. Just like accessing views, you can specify a limit parameter to request just a subset of the data, and adding include_docs=true will cause full documents to be returned.

Typically you won’t want all the changes from the beginning of time. You’re more likely to want the changes that have occurred since you last checked. For this, use the since parameter, specifying a sequence ID (pull one from the output of the last cURL command):

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/_changes?since=10057-g1.....FqzAI2DMmw" |

| | { |

| | "results":[{ |

| | "seq":"10057-g1.....U9OzMnILy7J", |

| | "id":"357995", |

| | "changes":[{"rev":"1-aa649aa53f2858cb609684320c235aee"}] |

| | }], |

| | "last_seq":100 |

| | } |

Using this method, the client application would check back periodically to find out whether any new changes have occurred, taking application-specific actions accordingly.

Polling is a fine solution if you can cope with long delays between updates. If updates are relatively rare, then you can use polling without encountering any serious drawbacks. For example, if you were pulling blog entries, polling every five minutes might be just fine.

If you want updates quicker, without incurring the overhead of reopening connections, then long polling is a better option. When you specify the URL parameter feed=longpoll, CouchDB will leave the connection open for some time, waiting for changes to happen before finishing the response. Try this:

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/_changes?feed=longpoll&\ |

| | since=10057-g1.....FqzAI2DMmw" |

| | {"results":[ |

You should see the beginning of a JSON response but nothing else. If you leave the terminal open long enough, CouchDB will eventually close the connection by finishing it:

| | ], |

| | "last_seq":9000} |

From a development perspective, writing a driver that watches CouchDB for changes using polling is equivalent to writing one for long polling. The difference is essentially just how long CouchDB is willing to leave the connection open. Now let’s turn our attention to writing a Node.js application that watches and uses the change feed.

Polling for Changes with Node.js

Node.js is a strongly event-driven system, so our CouchDB watcher will adhere to this principle as well. Our driver will watch the changes feed and emit change events whenever CouchDB reports changed documents. To get started, we’ll look at a skeletal outline of our driver, talk about the major pieces, and then fill in the feed-specific details.

Without further ado, here’s the outline of our watcher program, as well as a brief discussion of what it does:

| | var http = require('http'), |

| | events = require('events'); |

| | |

| | /** |

| | * create a CouchDB watcher based on connection criteria; |

| | * follows the Node.js EventEmitter pattern, emits 'change' events. |

| | */ |

| | exports.createWatcher = function(options) { |

| | |

| | var watcher = new events.EventEmitter(); |

| | |

| | watcher.host = options.host || 'localhost'; |

| | watcher.port = options.port || 5984; |

| | watcher.last_seq = options.last_seq || 0; |

| | watcher.db = options.db || '_users'; |

| | |

| | watcher.start = function() { |

| | // ... feed-specific implementation ... |

| | }; |

| | |

| | return watcher; |

| | |

| | }; |

| | |

| | // start watching CouchDB for changes if running as main script |

| | if (!module.parent) { |

| | exports.createWatcher({ |

| | db: process.argv[2], |

| | last_seq: process.argv[3] |

| | }) |

| | .on('change', console.log) |

| | .on('error', console.error) |

| | .start(); |

| | } |

So what’s happening in this watcher? A few things to pay attention to:

-

exports is a standard object provided by the CommonJS Module API that Node.js implements. Adding the createWatcher method to exports makes it available to other Node.js scripts that might want to use this as a library. The options argument allows the caller to specify which database to watch as well as override other connection settings.

-

createWatcher produces an EventEmitter object that the caller can use to listen for change events. With an EventEmitter, you can listen to events by calling its on method and trigger events by calling its emit method.

-

watcher.start is responsible for issuing HTTP requests to watch CouchDB for changes. When changes to documents happen, watcher should emit them as change events. All of the feed-specific implementation details will be in here.

-

The last chunk of code at the bottom specifies what the script should do if it’s called directly from the command line. In this case, the script will invoke the createWatcher method then set up listeners on the returned object that dump results to standard output. Which database to connect to and what sequence ID number to start from can be set via command-line arguments.

So far, there’s nothing specific to CouchDB at all in this code. It’s all just Node.js’s way of doing things. With the skeleton in place, let’s add the code to connect to CouchDB via long polling and emit events. The following is just the code that goes inside the watcher.start method. Written inside the previous outline (where the comment says feed-specific implementation), the new complete file should be called watchChangesLongpolling.js.

| | var httpOptions = { |

| | host: watcher.host, |

| | port: watcher.port, |

| | path: '/' + |

| | watcher.db + |

| | '/_changes' + |

| | '?feed=longpoll&include_docs=true&since=' + |

| | watcher.last_seq |

| | }; |

| | |

| | http.get(httpOptions, function(res) { |

| | var buffer = ''; |

| | |

| | res.on('data', function (chunk) { |

| | buffer += chunk; |

| | }); |

| | res.on('end', function() { |

| | var output = JSON.parse(buffer); |

| | if (output.results) { |

| | watcher.last_seq = output.last_seq; |

| | output.results.forEach(function(change){ |

| | watcher.emit('change', change); |

| | }); |

| | watcher.start(); |

| | } else { |

| | watcher.emit('error', output); |

| | } |

| | }) |

| | }) |

| | .on('error', function(err) { |

| | watcher.emit('error', err); |

| | }); |

Here are some things to look out for in the long polling script:

-

The first thing this script does is set up the httpOptions configuration object in preparation for the request. The path points to the same _changes URL we’ve been using, with feed set to longpoll and include_docs=true.

-

After that, the script calls http.get, a Node.js library method that fires off a GET request according to our settings. The second parameter to http.get is a callback that will receive an HTTPResponse. The response object emits data events as the content is streamed back, which we add to the buffer.

-

Finally, when the response object emits an end event, we parse the buffer (which should contain JSON). From this we learn the new last_seq value, emit a change event, and then reinvoke watcher.start to wait for the next change.

To run this script in command-line mode, execute it like this (output truncated for brevity):

| | $ node watchChangesLongpolling.js music |

| | { seq: '...', |

| | id: '370255', |

| | changes: [ { rev: '1-a7b7cc38d4130f0a5f3eae5d2c963d85' } ], |

| | doc: |

| | { _id: '370255', |

| | _rev: '1-a7b7cc38d4130f0a5f3eae5d2c963d85', |

| | albums: [ [Object] ], |

| | id: '370255', |

| | name: '""ATTIC""', |

| | url: 'http://www.jamendo.com/artist/ATTIC_(3)', |

| | mbgid: '', |

| | random: 0.4121620435325435 } } |

| | { seq: '...', |

| | id: '370254', |

| | changes: [ { rev: '1-2c7e0deec3ffca959ba0169b0e8bfcef' } ], |

| | doc: |

| | { _id: '370254', |

| | _rev: '1-2c7e0deec3ffca959ba0169b0e8bfcef', |

| | ... many more entries ... |

Hurrah, our app works! After outputting a record for each document, the process will keep running, polling CouchDB for future changes.

Feel free to modify a document in Fauxton directly or increase the @max value on import_from_jamendo.rb and run it again. You’ll see those changes reflected on the command line. Next you’ll see how to go full steam ahead and use the continuous feed to get even snappier updates.

Watching for Changes Continuously

The polling and long polling feeds produced by the _changes service both produce proper JSON results. The continuous feed does things a little differently. Instead of combining all available changes into a results array and closing the stream afterward, it sends each change separately and keeps the connection open. This way, it’s ready to return more JSON-serialized change notification objects as changes become available.

To see how this works, try the following, supplying a value for since (output truncated for readability):

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/_changes?since=...feed=continuous" |

| | {"seq":"...","id":"357999","changes":[{"rev":"1-0329f5c885...87b39beab0"}]} |

| | {"seq":"...","id":"357998","changes":[{"rev":"1-79c3fd2fe6...1e45e4e35f"}]} |

| | {"seq":"...","id":"357995","changes":[{"rev":"1-aa649aa53f...320c235aee"}]} |

Eventually, if no changes have happened for a while, CouchDB will close the connection after outputting a line like this:

| | {"last_seq":100} |

The benefit of this method over polling or long polling is the reduced overhead that accompanies leaving the connection open. There’s no time lost reestablishing the HTTP connections. On the other hand, the output isn’t straight JSON, which means it’s a bit more of a chore to parse. Also, it’s not a good fit if your client is a web browser. A browser downloading the feed asynchronously might not receive any of the data until the entire connection finishes (better to use long polling in this case).

Filtering Changes

As you’ve just seen, the Changes API provides a unique window into the goings-on of a CouchDB database. On the plus side, it provides all the changes in a single stream. However, sometimes you may want just a subset of changes, rather than the fire hose of everything that has ever changed. For example, you may be interested only in document deletions or maybe only in documents that have a particular quality. This is where filter functions come in.

A filter is a function that takes in a document (and request information) and makes a decision about whether that document ought to be allowed through the filter. This is gated by the return value. Let’s explore how this works. Most artist documents we’ve been inserting into the music database have a country property that contains a three-letter code. Say you’re interested only in bands from Russia (RUS). Your filter function might look like the following:

| | function(doc) { |

| | return doc.country === "RUS"; |

| | } |

If we added this to a design document under the key filters, we’d be able to specify it when issuing requests for _changes. But before we do, let’s expand the example. Rather than always wanting Russian bands, it’d be better if we could parameterize the input so the country could be specified in the URL.

Here’s a parameterized country-based filter function:

| | function(doc, req) { |

| | return doc.country === req.query.country; |

| | } |

Notice this time how we’re comparing the document’s country property to a parameter of the same name passed in the request’s query string. To see this in action, let’s create a new design document just for geography-based filters and add it:

| | $ curl -XPUT "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/_design/wherabouts" \ |

| | -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ |

| | -d '{"language":"javascript","filters":{"by_country": |

| | "function(doc,req){return doc.country === req.query.country;}" |

| | }}' |

| | { |

| | "ok":true, |

| | "id":"_design/wherabouts", |

| | "rev":"1-c08b557d676ab861957eaeb85b628d74" |

| | } |

Now we can make a country-filtered changes request:

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/_changes?\ |

| | filter=wherabouts/by_country&\ |

| | country=RUS" |

| | {"results":[ |

| | {"seq":10,"id":"5987","changes":[{"rev":"1-2221be...a3b254"}]}, |

| | {"seq":57,"id":"349359","changes":[{"rev":"1-548bde...888a83"}]}, |

| | {"seq":73,"id":"364718","changes":[{"rev":"1-158d2e...5a7219"}]}, |

| | ... |

Because filter functions may contain arbitrary JavaScript, more sophisticated logic can be put into them. Testing for deeply nested fields would be similar to what we did for creating views. You could also use regular expressions for testing properties or compare them mathematically (for example, filtering by a date range). There’s even a user context property on the request object (req.userCtx) that you can use to find out more about the credentials provided with the request.

We’ll revisit Node.js and the CouchDB Changes API in Chapter 8, Redis when we build a multidatabase application. For now, though, it’s time to move on to the last distinguishing feature of CouchDB we’re going to cover: replication.

Replicating Data in CouchDB

CouchDB is all about asynchronous environments and data durability. According to CouchDB, the safest place to store your data is on many nodes in your cluster (you can configure how many), and CouchDB provides the tools to do so. Some other databases we’ve looked at maintain a single master node to guarantee consistency. Still others ensure it with a quorum of agreeing nodes. CouchDB does neither of these; instead, it supports something called multi-master or master-master replication.

Each CouchDB server is equally able to receive updates, respond to requests, and delete data, regardless of whether it’s able to connect to any other server. In this model, changes are selectively replicated in one direction, and all data is subject to replication in the same way.

Replication is the last major topic in CouchDB that we’ll be discussing. First you’ll see how to set up ad hoc and continuous replication between databases. Then you’ll work through the implications of conflicting data and how to make applications capable of handling these cases gracefully.

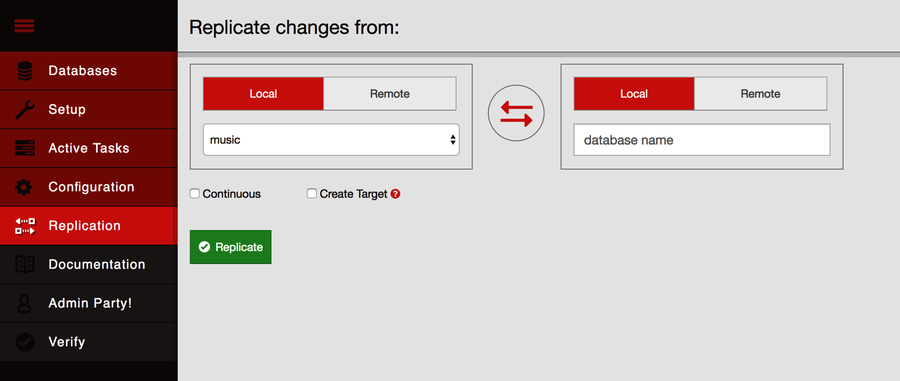

To begin, click the Replication link on the left side of the page. It should open a page that looks like the figure that follows.

In the “Replicate changes from” dialog, choose music from the left drop-down menu and enter music-repl in the right-side slot. Leave the Continuous checkbox unchecked, check the Create Target box, and then click Replicate. This should produce an event message in the event log below the form followed by a big green banner at the top of the page saying that the replication operation has begun.

To confirm that the replication request worked, go back to the Fauxton Databases page. There should now be a new database called music-repl with the same number of documents as the music database. If it has fewer, give it some time and refresh the page—CouchDB may be in the process of catching up. Don’t be concerned if the Update Seq values don’t match. That’s because the original music database had deletions and updates to documents, whereas the music-repl database had only insertions to bring it up to speed.

Creating Conflicts

Next, we’ll create a conflict and then explore how to deal with it. Keep the Replicator page handy because we’re going to be triggering ad hoc replication between music and music-repl frequently. Drop back to the command line, and enter this to create a document in the music database:

| | $ curl -XPUT "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/theconflicts" \ |

| | -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ |

| | -d '{ "name": "The Conflicts" }' |

| | { |

| | "ok":true, |

| | "id":"theconflicts", |

| | "rev":"1-e007498c59e95d23912be35545049174" |

| | } |

On the Replication page, click Replicate to trigger another synchronization. We can confirm that the document was successfully replicated by retrieving it from the music-repl database.

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music-repl/theconflicts" |

| | { |

| | "_id":"theconflicts", |

| | "_rev":"1-e007498c59e95d23912be35545049174", |

| | "name":"The Conflicts" |

| | } |

Next, let’s update it in music-repl by adding an album called Conflicts of Interest.

| | $ curl -XPUT "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music-repl/theconflicts" \ |

| | -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ |

| | -d '{ |

| | "_id": "theconflicts", |

| | "_rev": "1-e007498c59e95d23912be35545049174", |

| | "name": "The Conflicts", |

| | "albums": ["Conflicts of Interest"] |

| | }' |

| | { |

| | "ok":true, |

| | "id":"theconflicts", |

| | "rev":"2-0c969fbfa76eb7fcdf6412ef219fcac5" |

| | } |

And create a conflicting update in music proper by adding a different album: Conflicting Opinions.

| | $ curl -XPUT "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music/theconflicts" \ |

| | -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ |

| | -d '{ |

| | "_id": "theconflicts", |

| | "_rev": "1-e007498c59e95d23912be35545049174", |

| | "name": "The Conflicts", |

| | "albums": ["Conflicting Opinions"] |

| | }' |

| | { |

| | "ok":true, |

| | "id":"theconflicts", |

| | "rev":"2-cab47bf4444a20d6a2d2204330fdce2a" |

| | } |

At this point, both the music and music-repl databases have a document with an _id value of theconflicts. Both documents are at version 2 and derived from the same base revision (1-e007498c59e95d23912be35545049174). Now the question is, what happens when we try to replicate between them?

Resolving Conflicts

With our document now in a conflicting state between the two databases, head back to the Replication page and kick off another replication. If you were expecting this to fail, you may be shocked to learn that the operation succeeds just fine. So how did CouchDB deal with the discrepancy?

It turns out that CouchDB basically just picks one and calls that one the winner. Using a deterministic algorithm, all CouchDB nodes will pick the same winner when a conflict is detected. However, the story doesn’t end there. CouchDB stores the unselected “loser” documents as well so that a client application can review the situation and resolve it at a later date.

To find out which version of our document won during the last replication, we can request it using the normal GET request channel. By adding the conflicts=true URL parameter, CouchDB will also include information about the conflicting revisions.

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music-repl/theconflicts?conflicts=true" |

| | { |

| | "_id":"theconflicts", |

| | "_rev":"2-cab47bf4444a20d6a2d2204330fdce2a", |

| | "name":"The Conflicts", |

| | "albums":["Conflicting Opinions"], |

| | "_conflicts":[ |

| | "2-0c969fbfa76eb7fcdf6412ef219fcac5" |

| | ] |

| | } |

So, we see that the second update won. Notice the _conflicts field in the response. It contains a list of other revisions that conflicted with the chosen one. By adding a rev parameter to a GET request, we can pull down those conflicting revisions and decide what to do about them.

| | $ curl "${COUCH_ROOT_URL}/music-repl/theconflicts?rev=2-0c969f..." |

| | { |

| | "_id":"theconflicts", |

| | "_rev":"2-0c969fbfa76eb7fcdf6412ef219fcac5", |

| | "name":"The Conflicts", |

| | "albums":["Conflicts of Interest"] |

| | } |

The takeaway here is that CouchDB does not try to intelligently merge conflicting changes. How you should merge two documents is highly application specific, and a general solution isn’t practical. In our case, combining the two albums arrays by concatenating them makes sense, but one could easily think of scenarios where the appropriate action is not obvious.

For example, imagine you’re maintaining a database of calendar events. One copy is on your smartphone; another is on your laptop. You get a text message from a party planner specifying the venue for the party you’re hosting, so you update your phone database accordingly. Later, back at the office, you receive another email from the planner specifying a different venue. So you update your laptop database and then replicate between them.

CouchDB has no way of knowing which of the two venues is "correct." The best it can do is make them consistent, keeping the old value around so you can verify which of the conflicting values should be kept. It would be up to the application to determine the right user interface for presenting this situation and asking for a decision.

Day 3 Wrap-Up

And so ends our tour of CouchDB. Here in Day 3, you started out by learning how to add reducer functions to your mapreduce-generated views. After that, we took a deep dive into the Changes API, including a jaunt into the world of event-driven server-side JavaScript development with Node.js. Lastly, we took a brief look at how you can trigger replication between databases and how client applications can detect and correct for conflicts.

Day 3 Homework

Find

-

What native reducers are available in CouchDB? What are the benefits of using native reducers over custom JavaScript reducers?

-

How can you filter the changes coming out of the _changes API on the server side?

-

Like everything in CouchDB, the tasks of initializing and canceling replication are controlled by HTTP commands under the hood. What are the REST commands to set up and remove replication relationships between servers?

-

How can you use the _replicator database to persist replication relationships?

Do

-

Create a new module called watchChangesContinuous.js based on the skeletal Node.js module described in the section Polling for Changes with Node.js.

-

Implement watcher.start such that it monitors the continuous _changes feed. Confirm that it produces the same output as watchChangesLongpolling.js.

Hint: If you get stuck, you can find an example implementation in the downloads that accompany this book.

-

Documents with conflicting revisions have a _conflicts property. Create a view that emits conflicting revisions and maps them to the doc _id.