5

Building a Memory game using Unity’s 2D functionality

- Displaying 2D graphics in Unity

- Making objects clickable

- Loading new images programmatically

- Maintaining and displaying state using UI text

- Loading levels and restarting the game

Up to now, we’ve been working with 3D graphics, but you can also work with 2D graphics in Unity. So in this chapter, you’ll build a 2D game to learn about that. You’re going to develop the classic children’s game Memory: you’ll display a grid of card backs, reveal the card front when it’s clicked, and score matches. These mechanics cover the basics you need to know in order to develop 2D games in Unity.

Although Unity originated as a tool for 3D games, it’s used often for 2D games as well. Later versions of Unity (starting with version 4.3, released near the end of 2013) have added the ability to display 2D graphics, but even before then 2D games were already being developed in Unity (especially mobile games that took advantage of Unity’s cross-platform nature). In prior versions of Unity, game developers required a third-party framework (such as 2D Toolkit from Unikron Software) to emulate 2D graphics within Unity’s 3D scenes. Eventually, the core editor and game engine were modified to incorporate 2D graphics, and this chapter will teach you about that newer functionality.

The 2D workflow in Unity is more or less the same as the workflow to develop a 3D game: import art assets, drag them into a scene, and write scripts to attach to the objects. The primary kind of art asset in 2D graphics is called a sprite.

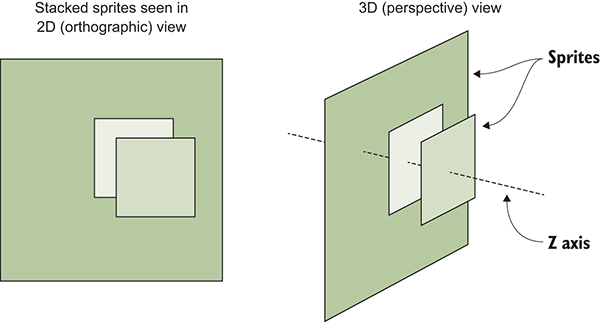

You can import 2D images into Unity as sprites in much the same way you can import images as textures (see chapter 4). Technically, these sprites will be objects in 3D space, but they’ll be flat surfaces all oriented perpendicular to the Z-axis. Because they’ll all face the same direction, you can point the camera straight at the sprites and players will only be able to discern their movements along the X- and Y-axes (that is, two dimensions).

In chapter 2, we discussed the coordinate axes: having three dimensions adds a Z-axis perpendicular to the X- and Y-axes you were already familiar with. Two dimensions are just those X- and Y-axes (that’s what your teacher was talking about in math class!).

5.1 Setting everything up for 2D graphics

You’re going to create the classic game of Memory. For those unfamiliar with this game, a series of cards will be dealt out facedown. Every card will have a matching card located somewhere else, but the player will see only the reverse side of the card. The player can turn over two cards at a time, attempting to find matching cards; if the two cards chosen aren’t a match, they’ll flip back and then the player can guess again.

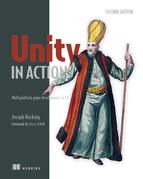

Figure 5.1 shows a mock-up of the game we’re going to build; compare this to the roadmap diagram from chapter 2.

Figure 5.1 Mock-up of what the Memory game will look like

Note that the mock-up this time depicts exactly what the player will see (whereas the mock-up for a 3D scene depicted the space around the player and then where the camera went for the player to see through). Now that you know what you’ll be building, it’s time to get to work!

5.1.1 Preparing the project

The first step is to gather up and display graphics for our game. In much the same way as building the 3D demo previously, you want to start the new game by putting together the minimum set of graphics for the game to operate, and after that’s in place, you can start programming the functionality.

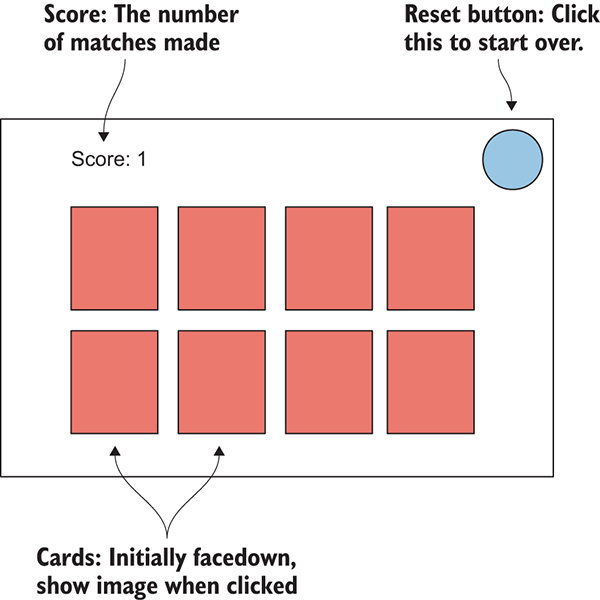

That means you’ll need to create everything depicted in figure 5.1: card backs for hidden cards, a series of card fronts for when they turn over, a score display in one corner, and a reset button in the opposite corner. We also need a background for the screen, so all together, our art requirements sum up to figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 Art assets required for the Memory game

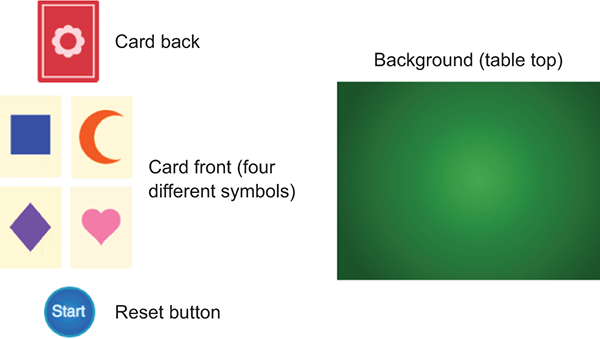

Gather together the required images, and then create a new project in Unity. In the New Project window that comes up, you’ll notice a couple of buttons at the bottom (shown in figure 5.3) that let you switch between 2D and 3D mode. In previous chapters, we’ve worked with 3D graphics, and because that’s the default value we haven’t been concerned with this setting. In this chapter, though, you’ll want to switch to 2D mode when creating a new project.

Figure 5.3 Create new projects in either 2D or 3D mode with these buttons.

With the new project for this chapter created and set for 2D, we can start putting our images into the scene.

5.1.2 Displaying 2D images (aka sprites)

Drag all the image files into the Project view to import them; make sure the images are imported as sprites and not textures. (This is automatic if the editor is set to 2D. Select an asset to see its import settings in the Inspector.) Now drag the table_top sprite (our background image) up from the Project view into the empty scene. As with mesh objects, in the Inspector there’s a Transform component for the sprite; type 0, 0, 5 to position the background image.

The 0s for the X and Y positions are straightforward (this sprite will fill the entire screen, so you want it at the center), but that 5 for the Z position might seem odd. For 2D graphics, shouldn’t only X and Y matter? Well, X and Y are the only coordinates that matter for positioning the object on the 2D screen; Z coordinates still matter for stacking objects, though. Lower Z values are closer to the camera, so sprites with lower Z values are displayed on top of other sprites (refer to figure 5.4). Accordingly, the background sprite should have the highest Z value. You’ll set your background to a positive Z position, and then give everything else a 0 or negative Z position.

Figure 5.4 How sprites stack along the Z-axis

Other sprites will be positioned with values with up to two decimal places because of the Pixels-To-Units setting mentioned earlier. A ratio of 100:1 means that 100 pixels in the image are 1 unit in Unity; put another way, 1 pixel is .01 units. But before you put any more sprites into the scene, let’s set up the camera for this game.

5.1.3 Switching the camera to 2D mode

Now let’s adjust settings on the main camera in the scene. You might think that because the Scene view is set to 2D, what you see in Unity is what you’ll see in the game. Somewhat unintuitively, though, that isn’t the case.

It turns out that, regardless of whether the Scene view is set to 2D mode, the camera in the game is set independently. This can be handy in many situations so that you can toggle the Scene view back to 3D in order to work on certain effects within the scene. This disconnect does mean that what you see in Unity isn’t necessarily what you see in the game, and it can be easy for beginners to forget this.

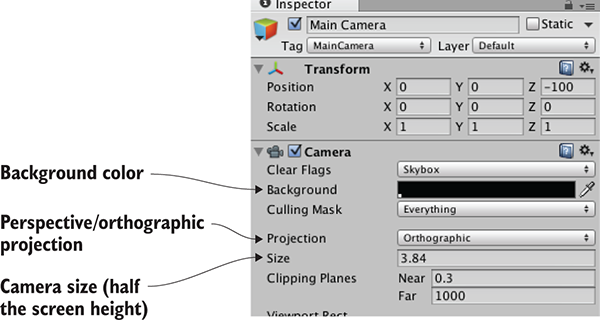

The most important camera setting to adjust is Projection. The camera projection is probably already correct because you created the new project in 2D mode, but this is still important to know about and worth double-checking. Select the camera in Hierarchy to show its settings in the Inspector, and then look for the Projection setting (see figure 5.5). For 3D graphics the setting should be Perspective, but for 2D graphics the camera projection should be Orthographic.

Figure 5.5 Camera settings to adjust for 2D graphics

Although the Projection mode is the most important camera setting for 2D graphics, there are a few other settings for us to adjust as well. Next, we’ll look at Size; that setting is under Projection. The camera’s orthographic size determines the size of the camera view from the center of the screen up to the top of the screen. In other words, set Size to half the pixel dimensions of the screen you want. If you later set the resolution of the deployed game to the same pixel dimensions, you’ll get pixel-perfect graphics.

Let’s say you want a pixel-perfect 1024 x 768 screen. That means the camera height should be 384 pixels. Divide that by 100 (because of the pixels-to-units scale) and you get 3.84 for the camera size. Again, that math is SCREEN_SIZE / 2 / 100f (f as in float, rather than an int value). Given that the background image is 1024 x 768 (select the asset to check its dimensions), then clearly this value of 3.84 is what we want for our camera.

The two remaining adjustments to make in the Inspector are the camera’s background color and Z position. As mentioned previously for sprites, higher Z positions are further away into the scene. As such, the camera should have a pretty low Z position; set the position of the camera to 0, 0, -100. The camera’s background color should probably be black; the default color is blue, and that’ll look odd displayed along the sides if the screen is wider than the background image (which is likely). Click the color swatch next to Background and set the color picker to black.

Now save the scene as Scene and hit Play; you’ll see the Game view filled with our tabletop sprite. As you saw, getting to this point wasn’t completely straightforward (again, that’s because Unity was a 3D game engine that has recently had 2D graphics grafted in). But the tabletop is completely bare, so our next step is to put a card on the table.

5.2 Building a card object and making it react to clicks

Now that the images are all imported and ready to use, let’s build the card objects that form the core of this game. In Memory, all the cards are initially face down, and they’re only face up temporarily when you choose a pair of cards to turn over. To implement this functionality, you’re going to create objects that consist of multiple sprites stacked on top of one another. Then, you’ll write code that makes the cards reveal themselves when clicked with the mouse.

5.2.1 Building the object out of sprites

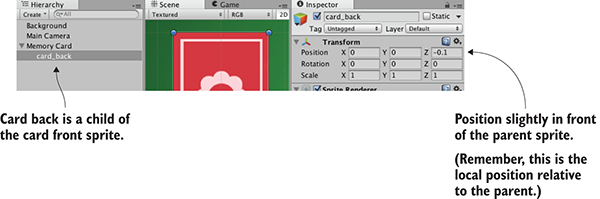

Drag one of the card images into the scene. Use one of the card fronts, because you’ll add a card back on top to hide the image. Technically, the position right now doesn’t matter, but eventually it will, so you may as well position the card at -3, 1, 0. Now drag the card_back sprite into the scene. Make this new sprite a child of the previous card sprite (remember, in the Hierarchy, drag the child object onto the parent object) and then set its position to 0, 0, -.1 (Keep in mind that this position is relative to the parent, so this means “Put it at the same X and Y but move it closer on Z.”)

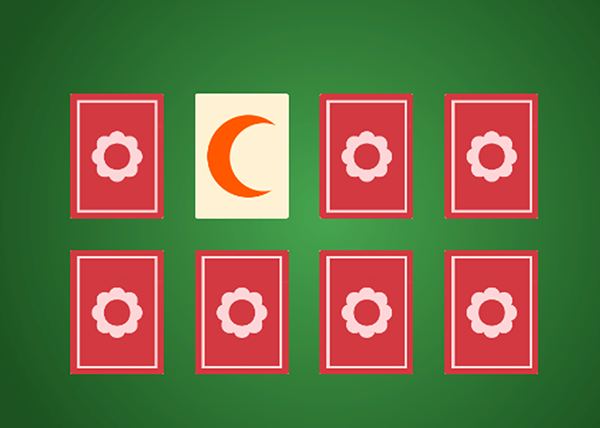

With the card back in place, as depicted in figure 5.6, the graphics are in place for a reactive card that can be revealed.

Figure 5.6 Hierarchy linking and position for the card back sprite

5.2.2 Mouse input code

In order to respond when the player clicks on them, the card sprites need to have a collider component. New sprites don’t have a collider by default, so they can’t be clicked on. You’re going to attach a collider to the root card object, but not to the card back, so that only the card front and not the card back will receive mouse clicks. To do this, select the root card object in Hierarchy (don’t click the card in the scene, because the card back is on top and you’ll select that part instead) and then click the Add Component button in the Inspector. Select Physics 2D (not Physics, because that system is for 3D physics and this is a 2D game), and then choose a box collider.

Besides a collider, the card needs a script in order to be reactive to the player clicking on it, so let’s write some code. Create a new script called MemoryCard.cs and attach this script to the root card object (again, not the card back). This listing shows the code that makes the card emit debug messages when clicked.

Listing 5.1 Emitting debug messages when clicked

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class MemoryCard : MonoBehaviour {

public void OnMouseDown() {

Debug.Log("testing 1 2 3");

}

}

Nice, we can click on the card now! Just like Update(), OnMouseDown() is another function provided by MonoBehaviour, this time responding when the object is clicked on. Play the game and watch messages appear in the console. But this only prints to the console for testing; we want the card to be revealed.

5.2.3 Revealing the card on click

Rewrite the code to match this listing (the code won’t run quite yet but don’t worry).

Listing 5.2 Script that hides the back when the card is clicked

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class MemoryCard : MonoBehaviour {

[SerializeField] private GameObject cardBack;

public void OnMouseDown() {

if (cardBack.activeSelf) {

cardBack.SetActive(false);

}

}

}

There are two key additions to the script: a reference to an object in the scene, and the SetActive() method that deactivates that object. The first part, the reference to an object in the scene, is similar to what we’ve done in previous chapters: mark the variable as serialized, and then drag the object from Hierarchy over to the variable in the Inspector. With the object reference set, the code will now affect the object in the scene.

The second key addition to the code is the SetActive command. That command will deactivate any GameObject, making that object invisible. If we now drag card_back in the scene to this script’s variable in the Inspector, when you play the game the card back disappears when you click the card. Hiding the card back will reveal the card front; we’ve accomplished yet another important task for the Memory game! But this is still only one card, so now let’s create a bunch of cards.

5.3 Displaying the various card images

We’ve programmed a card object that initially shows the card back but reveals itself when clicked. That was a single card, but the game needs a whole grid of cards, with different images on most cards. We’ll implement the grid of cards using a couple of concepts seen in previous chapters, along with some concepts you haven’t seen before. Chapter 3 included the notions of (1) using an invisible SceneController component and (2) instantiating clones of an object. The SceneController will apply different images to different cards this time.

5.3.1 Loading images programmatically

There are four card images in the game we’re creating. All eight cards on the table (two for each symbol) will be created by cloning the same original, so initially, all cards will have the same symbol. We’ll have to change the image on the card in the script, loading different images programmatically.

To examine how images can be assigned programmatically, let’s write simple test code (that will be replaced later) to demonstrate the technique. First, add this code to the MemoryCard script.

Listing 5.3 Test code to demonstrate changing the sprite image

...

[SerializeField] private Sprite image;

void Start() {

GetComponent<SpriteRenderer>().sprite = image;

}

...

After you save this script, the new image variable will appear in the Inspector because it has been set as serialized. Drag a sprite up from the Project view (pick one of the card images, and not the same as the image already in the scene) and drop it on the Image slot. Now run the scene, and you’ll see the new image on the card.

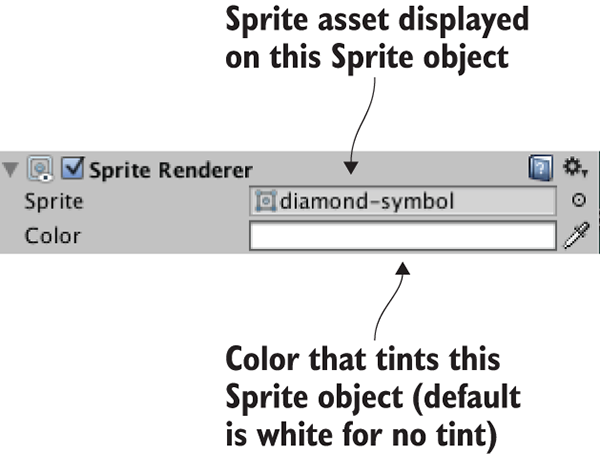

The key to understanding this code is to know about the SpriteRenderer component. You’ll notice in figure 5.7 that the card back object has just two components, the standard Transform component on all objects in the scene, and a new component called SpriteRenderer. This component makes it a sprite object and determines which sprite asset will be displayed. Note that the first property in the component is called Sprite and links to one of the sprites in the Project view; the property can be manipulated in code, and that’s precisely what this script does.

Figure 5.7 A sprite object in the scene has the SpriteRenderer component attached to it.

As it did with CharacterController and custom scripts in previous chapters, the GetComponent() method returns other components on the same object, so we use it to reference the SpriteRenderer object. The sprite property of SpriteRenderer can be set to any sprite asset, so this code sets that property to the Sprite variable declared at the top (which we filled with a sprite asset in the editor).

Well, that wasn’t too hard! But it’s only a single image; we have four different images to use, so now delete the new code from Listing 5.3 (it was only a demonstration of how the technique works) to prepare for the next section.

5.3.2 Setting the image from an invisible SceneController

Recall how, in chapter 3, we created an invisible object in the scene to control spawning objects. We’re going to take that approach here as well, using an invisible object to control more abstract features that aren’t tied to any specific object in the scene. First, create an empty GameObject (remember, select menu GameObject > Create Empty). Then create a new script, SceneController.cs, in the Project view, and drag this script asset onto the controller GameObject. Before writing code in the new script, first add the contents of the next listing to the MemoryCard script instead of what you saw in Listing 5.3.

Listing 5.4 New public methods in MemoryCard.cs

...

[SerializeField] private SceneController controller;

private int _id;

public int id {

get {return _id;}

}

public void SetCard(int id, Sprite image) {

_id = id;

GetComponent<SpriteRenderer>().sprite = image;

}

...

The primary change from previous listings is that we’re now setting the sprite image in SetCard() instead of Start(). Because that’s a public method that takes a sprite as a parameter, you can call this function from other scripts and set the image on this object. Note that SetCard() also takes an ID number as a parameter, and the code stores that number. Although we don’t need the ID quite yet, soon we’ll write code that compares cards for matches, and that comparison will rely on the IDs of the cards.

Finally, note that the code has a variable for the controller; even as SceneController starts cloning card objects to fill the scene, the card objects also need a reference to the controller to call its public methods. As usual, when the code references objects in the scene, drag the controller object in Unity’s editor to the variable slot in the Inspector. Do this once for this single card and all of the copies to come later will have the reference as well.

With that additional code now in MemoryCard, write this code in SceneController.

Listing 5.5 First pass at SceneController for the Memory game

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class SceneController : MonoBehaviour {

[SerializeField] private MemoryCard originalCard;

[SerializeField] private Sprite[] images;

void Start() {

int id = Random.Range(0, images.Length);

originalCard.SetCard(id, images[id]);

}

}

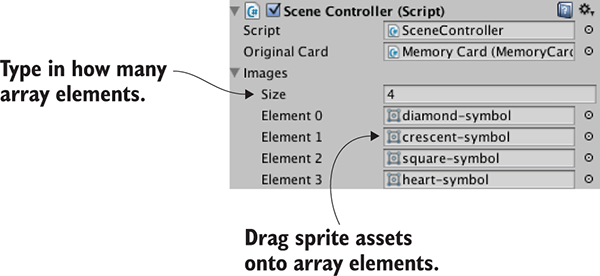

For now, this is a short snippet to demonstrate the concept of manipulating cards from SceneController. Most of this should already be familiar to you (for example, in Unity’s editor, drag the card object to the variable slot in the Inspector), but the array of images is new. As shown in figure 5.8, in the Inspector you can set the number of elements. Type in 4 for the array length, and then drag the sprites for card images onto the array slots. Now these sprites can be accessed in the array, like any other object reference.

Figure 5.8 The filled-in array of sprites

Incidentally, we used the Random.Range() method in chapter 3, so hopefully you recall that. The exact boundary values didn’t matter there, but this time it’s important to note that the minimum value is inclusive and may be returned, whereas the return value is always below the maximum.

Hit Play to run this new code. You’ll see different images being applied to the revealed card each time you run the scene. The next step is to create a whole grid of cards, instead of only one.

5.3.3 Instantiating a grid of cards

SceneController already has a reference to the card object, so now you’ll use the Instantiate() method (see the next listing) to clone the object numerous times, like spawning objects in chapter 3.

Listing 5.6 Cloning the card eight times and positioning in a grid

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class SceneController : MonoBehaviour {

public const int gridRows = 2;

public const int gridCols = 4;

public const float offsetX = 2f;

public const float offsetY = 2.5f;

[SerializeField] private MemoryCard originalCard;

[SerializeField] private Sprite[] images;

void Start() {

Vector3 startPos = originalCard.transform.position;

for (int i = 0; i < gridCols; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < gridRows; j++) {

MemoryCard card;

if (i == 0 && j == 0) {

card = originalCard;

} else {

card = Instantiate(originalCard) as MemoryCard;

}

int id = Random.Range(0, images.Length);

card.SetCard(id, images[id]);

float posX = (offsetX * i) + startPos.x;

float posY = -(offsetY * j) + startPos.y;

card.transform.position = new Vector3(posX, posY, startPos.z);

}

}

}

}

Although this script is much longer than the previous listing, there’s not a lot to explain because most of the additions are straightforward variable declarations and math. The oddest bit of this code is probably the if/else statement that begins if (i == 0 && j == 0). What that conditional does is either use the original card object for the first grid slot or clone the card object for all other grid slots. Because the original card already exists in the scene, if you copied the card at every iteration of the loop, you’d end up with one too many cards in the scene. The cards are then positioned by offsetting them according to the number of iterations through the loop.

Run the code now and a grid of eight cards will be created (as depicted in figure 5.9). The last step in preparing the grid of cards is to organize them into pairs, instead of them being random.

Figure 5.9 The grid of eight cards, which are revealed when you click on them

5.3.4 Shuffling the cards

Instead of making every card random, we’ll define an array of all the card IDs (numbers 0 through 3 twice, for a pair of each card) and then shuffle that array. We’ll then use this array of card IDs when setting cards, rather than making each one random.

Listing 5.7 Placing cards from a shuffled list

...

void Start() {

Vector3 startPos = originalCard.transform.position;

int[] numbers = {0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3};

numbers = ShuffleArray(numbers);

for (int i = 0; i < gridCols; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < gridRows; j++) {

MemoryCard card;

if (i == 0 && j == 0) {

card = originalCard;

} else {

card = Instantiate(originalCard) as MemoryCard;

}

int index = j * gridCols + i;

int id = numbers[index];

card.SetCard(id, images[id]);

float posX = (offsetX * i) + startPos.x;

float posY = -(offsetY * j) + startPos.y;

card.transform.position = new Vector3(posX, posY, startPos.z);

}

}

}

private int[] ShuffleArray(int[] numbers) {

int[] newArray = numbers.Clone() as int[];

for (int i = 0; i < newArray.Length; i++ ) {

int tmp = newArray[i];

int r = Random.Range(i, newArray.Length);

newArray[i] = newArray[r];

newArray[r] = tmp;

}

return newArray;

}

...

Now, when you hit Play, the grid of cards will be a shuffled assortment that reveals exactly two of each card image. The array of cards was run through the Knuth (also known as Fisher-Yates) shuffle algorithm, a simple yet effective way of shuffling the elements of an array. This algorithm loops through the array and swaps every element of the array with another randomly chosen array position.

You can click on all the cards to reveal them, but the game of Memory is supposed to proceed in pairs; a bit more code is needed.

5.4 Making and scoring matches

The last step in making a fully functional Memory game is checking for matches. Although we now have a grid of cards that are revealed when clicked, the various cards don’t affect each other in any way. In the game of Memory, every time a pair of cards is revealed we should check to see if the revealed cards match.

This abstract logic—checking for matches and responding appropriately—requires that cards notify SceneController when they’ve been clicked. That requires the additions to SceneController.cs shown in the next listing.

Listing 5.8 SceneController, which must keep track of revealed cards

...

private MemoryCard _firstRevealed;

private MemoryCard _secondRevealed;

public bool canReveal {

get {return _secondRevealed == null;}

}

...

public void CardRevealed(MemoryCard card) {

// initially empty

}

...

The CardRevealed() method will be filled in momentarily; we needed the empty scaffolding for now to refer to in MemoryCard.cs without any compiler errors. Note that there is a read-only getter again, this time used to determine whether another card can be revealed; the player can only reveal another card when there aren’t already two cards revealed.

We also need to modify MemoryCard.cs to call the (currently empty) method in order to inform SceneController when a card is clicked. Modify the code in MemoryCard.cs according to this listing.

Listing 5.9 MemoryCard.cs modifications for revealing cards

...

public void OnMouseDown() {

if (cardBack.activeSelf && controller.canReveal) {

cardBack.SetActive(false);

controller.CardRevealed(this);

}

}

public void Unreveal() {

cardBack.SetActive(true);

}

...

If you were to put a debug statement inside CardRevealed() in order to test the communication between objects, you’d see the test message appear whenever you click a card. Let’s first handle one revealed pair.

5.4.1 Storing and comparing revealed cards

The card object was passed into CardRevealed(), so let’s start keeping track of the revealed cards.

Listing 5.10 Keeping track of revealed cards in SceneController

...

public void CardRevealed(MemoryCard card) {

if (_firstRevealed == null) {

_firstRevealed = card;

} else {

_secondRevealed = card;

Debug.Log("Match? " + (_firstRevealed.id == _secondRevealed.id));

}

}

...

The listing stores the revealed cards in one of the two card variables, depending on whether the first variable is already occupied. If the first variable is empty, then fill it; if it’s already occupied, fill the second variable and check the card IDs for a match. The Debug statement prints either true or false in the console.

At the moment, the code doesn’t respond to matches—it only checks for them. Now let’s program the response.

5.4.2 Hiding mismatched cards

We’ll use coroutines again because the reaction to mismatched cards should pause to allow the player to see the cards. Refer to chapter 3 for a full explanation of coroutines; long story short, using a coroutine will allow us to pause before checking for a match. This listing shows more code for you to add to SceneController.

Listing 5.11 SceneController, scores match or hide missed matches

...

private int _score = 0;

...

public void CardRevealed(MemoryCard card) {

if (_firstRevealed == null) {

_firstRevealed = card;

} else {

_secondRevealed = card;

StartCoroutine(CheckMatch());

}

}

private IEnumerator CheckMatch() {

if (_firstRevealed.id == _secondRevealed.id) {

_score++;

Debug.Log("Score: " + _score);

}

else {

yield return new WaitForSeconds(.5f);

_firstRevealed.Unreveal();

_secondRevealed.Unreveal();

}

_firstRevealed = null;

_secondRevealed = null;

}

...

First, add a _score value to track; then, launch a coroutine to CheckMatch() when a second card is revealed. In that coroutine there are two code paths, depending on whether the cards match. If they match, the coroutine doesn’t pause; the yield command gets skipped over. If the cards don’t match, the coroutine pauses for half a second before calling Unreveal() on both cards, hiding them again. Finally, whether or not a match was made, the variables for storing cards are both nulled out, paving the way for revealing more cards.

When you play the game, mismatched cards will display briefly before hiding again. There are debug messages when you score matches, but we want the score displayed as a label on the screen.

5.4.3 Text display for the score

Displaying information to the player is half of the reason for a UI in a game (the other half is receiving input from the player. UI buttons are discussed in the next section).

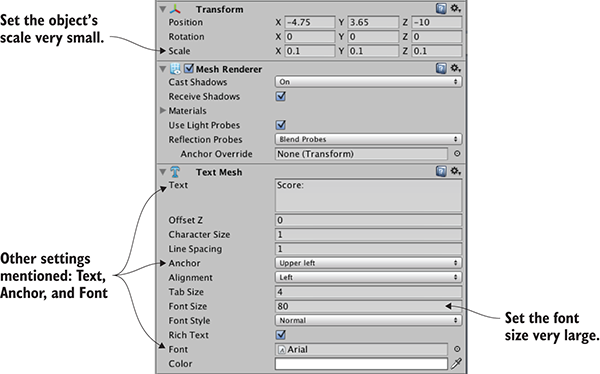

Unity has multiple ways to create text displays. One way is to create a 3D text object in the scene. This is a special mesh component, so first create an empty object to attach this component to. From the GameObject menu, choose Create Empty, then click the Add Component button and choose Mesh > Text Mesh.

Position this object at -4.75, 3.65, -10; that’s 475 pixels to the left and 365 pixels up, putting it in the top-left corner, and nearer to the camera so that it’ll appear on top of other game objects. In the Inspector, look for the Font setting toward the bottom; click the little circle button to bring up a file selector and then pick the Arial font that’s available. Enter Score: as the Text setting. Correct positioning also requires Upper Left for the Anchor setting (this controls how letters expand out as they’re typed), so change this if needed. By default, the text appears blurry, but that’s easily fixed by adjusting the settings shown in figure 5.10.

Figure 5.10 Inspector settings for a text object to make the text sharp and clear

If you import a new TrueType font into the project you could use that instead, but for our purposes the default font is fine. Oddly enough, a bit of size adjustment is needed to make the default text sharp and clear. First, set the TextMesh component’s Font Size setting to a very large value (I used 80). Now scale the object down to be very small (like .1, .1, 1). Increasing Font Size added a lot of pixels to the text displayed, and scaling the object compressed those pixels into a smaller space.

Manipulating this text object requires just a few adjustments in the scoring code.

Listing 5.12 Displaying the score on a text object

...

[SerializeField] private TextMesh scoreLabel;

...

private IEnumerator CheckMatch() {

if (_firstRevealed.id == _secondRevealed.id) {

_score++;

scoreLabel.text = "Score: " + _score;

}

...

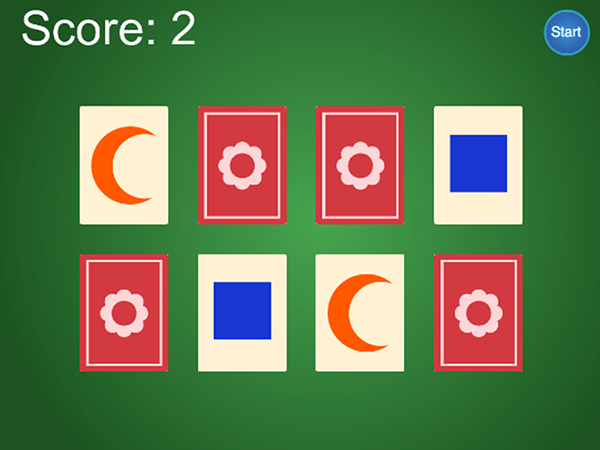

As you can see, text is a property of the object that you can set to a new string. Drag the text in the scene to the variable you just added to SceneController, and then hit Play. Now you should see the score displayed while you play the game and make matches. Huzzah, the game works!

5.5 Restart button

At this point, the Memory game is fully functional. You can play the game, and all the essential features are in place. But this playable core is still lacking the overarching functionality that players expect or need in a finished game. For example, right now, you can play the game only once; you need to quit and restart in order to play again. Let’s add a control to the screen so that players can start the game over without having to quit.

This functionality breaks down into two tasks: create a UI button and reset the game when that button is clicked. Figure 5.11 shows what the game will look like with the Start button.

Figure 5.11 Complete Memory game screen, including the Start button

Neither task is specific to 2D games, by the way; all games need UI buttons, and all games need the ability to reset. We’ll go over both topics to round out this chapter.

5.5.1 Programming a UIButton component using SendMessage

First, place the button sprite in the scene; drag it up from the Project view. Give it a position like 4.5, 3.25, -10; that will place the button in the top-right corner (that’s 450 pixels to the right and 325 pixels up) and move it nearer to the camera so that it’ll appear on top of other game objects. Because we want to be able to click on this object, give it a collider (just as with the card object, select Add Component > Physics 2D > Box Collider).

Now create a new script called UIButton.cs and assign it (shown next) to the button object.

Listing 5.13 Code to make a generic and reusable UI button

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class UIButton : MonoBehaviour {

[SerializeField] private GameObject targetObject;

[SerializeField] private string targetMessage;

public Color highlightColor = Color.cyan;

public void OnMouseEnter() {

SpriteRenderer sprite = GetComponent<SpriteRenderer>();

if (sprite != null) {

sprite.color = highlightColor;

}

}

public void OnMouseExit() {

SpriteRenderer sprite = GetComponent<SpriteRenderer>();

if (sprite != null) {

sprite.color = Color.white;

}

}

public void OnMouseDown() {

transform.localScale = new Vector3(1.1f, 1.1f, 1.1f);

}

public void OnMouseUp() {

transform.localScale = Vector3.one;

if (targetObject != null) {

targetObject.SendMessage(targetMessage);

}

}

}

The majority of this code happens inside a series of OnMouseSomething functions; like Start() and Update(), these are a series of functions automatically available to all script components in Unity. MouseDown was mentioned in section 5.2.2, but all these functions respond to mouse interactions if the object has a collider. MouseEnter and MouseExit are a pair of events used for hovering the mouse cursor over an object: MouseEnter is the moment when the mouse cursor first moves over an object, and MouseExit is the moment when the mouse cursor moves away. Similarly, MouseDown and MouseUp are a pair of events for clicking the mouse. MouseDown is the moment when the mouse button is physically pressed, and MouseUp is the moment when the mouse button is released.

You can see that this code tints the sprite when the mouse hovers over it and scales the sprite when it’s clicked on. In both cases, you can see that the change (in color or scale) happens when the mouse interaction begins, and then the property returns to default (either white or scale 1) when the mouse interaction ends. For scaling, the code uses the standard transform component that all GameObjects have. For tint, though, the code uses the SpriteRenderer component that sprite objects have; the sprite is set to a color that’s defined in Unity’s editor through a public variable.

In addition to returning the scale to 1, SendMessage() is called when the mouse is released. SendMessage() calls the function of the given name in all components of that GameObject. Here, the target object for the message, as well as the message to send, are both defined by serialized variables. This way, the same UIButton component can be used for all sorts of buttons, with the target of different buttons set to different objects in the Inspector.

Normally, when doing OOP in a strongly typed language like C#, you need to know the type of a target object in order to communicate with that object (for example, to call a public method of the object, like calling targetObject.SendMessage() itself). But scripts for UI elements may have lots of different types of targets, so Unity provides the SendMessage() method to communicate specific messages with a target object even if you don’t know exactly what type of object it is.

With this code written, wire up the public variables in the button’s Inspector. The highlight color can be set to whatever you’d like (although the default cyan looks pretty good on a blue button). Meanwhile, put the SceneController object in the target object slot, and then type Restart as the message.

If you play the game now, there’s a Reset button in the top-right corner that changes color in response to the mouse, and it makes a slight visual pop when clicked on. But an error message will be emitted when you click the button; in the console, you’ll see an error about there not being a receiver for the Restart message. That’s because we haven’t written a Restart() method in SceneController, so let’s add that.

5.5.2 Calling LoadScene from SceneController

The SendMessage() from the button attempts to call Restart() in the SceneController, so let’s add that now.

Listing 5.14 SceneController code that reloads the level

...

using UnityEngine.SceneManagement;

...

public void Restart() {

SceneManager.LoadScene("Scene");

}

...

You can see the one thing Restart() does is call LoadScene(). That command loads a saved scene asset (that is, the file created when you click Save Scene in Unity). Pass the method the name of the scene you want to load; in my case, the scene was saved with the name Scene, but if you used a different name, pass that to the method instead.

Hit Play to see what happens. Reveal a few cards and make a few matches; if you then click the Reset button, the game starts over, with all cards hidden and a score of 0. Great, just what we wanted!

As the name LoadScene() implies, this method can load different scenes. But what exactly happens when a scene loads, and why does this reset the game? What happens is that everything from the current level (all objects in the scene, and thus all scripts attached to those objects) is flushed from memory, and then everything from the new scene is loaded. Because the new scene, in this case, is the saved asset of the current scene, everything is flushed from memory and then reloaded from scratch.

Another game successfully completed! Well, completed is a relative term; you could always implement more features, but everything from the initial plan is done. Many of the concepts from this 2D game apply to 3D games as well, especially the checking of game state and loading levels. Time to switch gears yet again and move away from this Memory game and on to new projects.

Summary

- Displaying 2D graphics in Unity uses an orthographic camera.

- For pixel-perfect graphics, the camera size should be half the screen height.

- Clicking on sprites requires that you first assign 2D colliders to them.

- New images for sprites can be loaded programmatically.

- UI text can be made using 3D text objects.

- Loading levels resets the scene.